Road safety on four continents : 14th international conference, Bangkok, Thailand 14-16 November 2007: Conference proceedings

Full text

(2) Session 1 Road Safety Plans and Strategies I Chairman: Mr Peter Elsenaar, GRSP Road traffic injury risk in Norway, road safety strategies and public health perspectives Stig H. Jörgensen, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway Initiating road safety policy through participation: A successful experience with a Chilean methodology Alfredo Del Valle, Innovative Development Institute, Chile A conceptual content analysis of politicians and safety experts judgements of transport safety in public decision making Torbjörn Rundmo, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway A method for improving road safety transfer from highly motorised countries to less motorised countries Mark King, CARRS-Q, Australia Freedom to auto enjoyment contra freedom from traffic accidents Per A. Loken, Safe Traffic. Info, Norway. Session 2 Modelling I Chairman: Dr Bhagwant Persaud, Ryerson University, Canada Study on relationships between crash and speed for expressway Changcheng Li, Research Institute of Highway, China Relationship between presence of passengers and freeway crash characteristics Mohamed Abdel-Aty, University of Central Florida, USA Concept of Pro-Active traffic safety engineering management Slobodan Lazic, Petroleum Development, Oman Zero inflated models based on real time traffic characteristics for predicting crash probabilities Nicholas J. Garber, University of Virginia, USA Studying the effect of weather conditions on daily crash counts Tom Brijs, Hasselt University, Belgium. Session 3 Commercial and Fleet Safety Chariman: Ms Lori Mooren, ARRB Group Ltd, Australia Introduction on heavy vehicle safety Lori Mooren, ARRB Group, Australia Striving forward with analysis, research, and technology at the United States Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration Michael Griffith, Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration, USA Education and training of heavy vehicle drivers Maria Jobenius, Scania, Sweden ITS solution to increase traffic safety behaviour for truck drivers: speed, seat belt and alcohol follow-up Magnus Hjälmdahl, VTI, Sweden Bus driver and passenger experiences and perceptions: Bus safety situation in Thailand Pichai Taneerananon, Prince of Songkla University, Thailand.

(3) Session 4 Road Safety Plans and Strategies II Chairman: Dr Rune Elvik, Institute of Transport Economics, Norway On the methods of road safety interventions in developing countries: Knowledge transfer from a policy perspective Matthew Ericson, Monash University Accident Research Centre, Australia Evaluating measures in order to achieve safety targets Harri Peltola, VTT, Finland Pattern and socio-economic implications of road crashes in south western Nigeria Ipingbemi Olusiyi, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Nigeria Road safety in Bangladesh and some recent advances Mazharul Hoque, Bangladesh University, Bangladesh The importance of consultation and cooperation from the perspective of a local Cambodian NGO Kim Pagna, Coalition for Road Safety (CRY), Cambodia. Session 5 Modelling II Chairman: Dr Mohamed Abdel-Aty, University of Central Florida, USA Refining Haddon s matrix: Evidencebased policy for preventing global road traffic injuries Robert Alexander Hawes, University of Ottawa, Canada International road safety comparisons using accident prediction models Bhagwant Persaud, Ryerson Polytechnic University, Canada Selecting and prioritizing safety projects through the use of net present value analysis Mark Plass / Felix Delgado, Florida Dept. of Transportation, USA Designing a model to identify and prioritize accident Black-Spots Ali Pirdavani, Tehran Traffic and Transportation Oranization, Iran Mahmood Saffarzade, Tarbiat Mondarres University, Iran Framework for real-time crash risk estimation: Implications of random and matched sampling schemes Mohamed Abdel-Aty, University of Central Florida, USA. Session 6 Vehicle Innovation Chairman: Director Michael Griffith, Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration, U.S Dept. of Transportation, USA The effectiveness of electronic stability control in reducing realworld crashes: A literature review Susan Ferguson, Ferguson International LLC, USA Methods for evaluation of electronic stability control (ESC) Astrid Linder, VTI, Sweden. a literature review. Vision-Based static pre crash warning David Mahalel, Transportation Research Institute, Israel Selection of control speeds in dynamic intelligent speed adaptation system: A preliminary analysis Kanok Boriboonsomsin, University of California, USA Personalized system for in-vehicle transmission of vms information design, implementation and testing within the context of the in-safety project Evangelos Bekiaris, Hellenic Institute of Transport, Greece Vehicle to vehicle communication Albert Kircher, VTI, Sweden Anna Anund, VTI, Sweden. how to prepare drivers for dangerous situations.

(4) Plenary Session Chairman: Director Gerard Waldron, ARRB Group Ltd, Australia Cascading the World Report, the ASEAN experience Robert Klein, Regional Programme Director, Asia, GRSP Developments in highway/traffic safety in the US Michael S. Griffith, Director, Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration U.S. Dept. of Transportation, USA Road traffic safety management system standard / ISO-RTS-MSS? Hans Skalin, Swedish Road Administration, Sweden Road Transport Safety Martijn Arends, Royal Dutch Shell The road safety work of the United Nations Commission for Europe: International legal instruments and campaigns Marie-Noëlle Poirier, UN Economic Commission for Europe, Switzerland. Session 7 Safety Management Chairman: Mr Terje Assum, Institute of Transport Economics, Norway Improving road safety in developing countries using netrisk: A road network risk management approach Peter Damen, ARRB Group, Australia Road safety management by objectives: a critical analysis of the Norwegian approach Rune Elvik, Institute of Transport Economics, Norway Road safety management and planning in Spain Anna Ferrer and Carmen Girón, Spanish Traffic General Directorate, Spain Field road safety reviews in the province of Gujarat Oleg Tonkonojenkov, Synecyics Transportation Consultants, Canada Implementing the European road safety observatory in the "SafetyNet" project Pete Thomas, Vehicle Safety Research Centre, UK. Session 8 Motorcycles and Bicycles Chairman: Dr Tuenjai Fukuda, Nihon University, Japan Reasons for poor/non-use of crash helmets by commercial motorcyclists in Oyo State, Nigeria Adesola Sangowawa, Department of Community Medicine, Nigeria Motorcycle crash characteristics in Thailand Sattrawut Ponboon, Thailand Accident Research Center, Thailand Challenging efforts in promoting young motorcyclist safety in Indonesia Dewanti Marsoya, Gadjah Mada University, Indonesia An impact study of seat belt and helmet use in Thailand Nuttapong Boontob, Thailand Accident Research Center, Thailand Analysis of bicycle crossing times at intersections for providing safer right of bicycle users Jin Kak Lee, Myong Ji University, Korea The value of an exclusive motorcycle lane in mix traffic: Malaysian experience M. Subramaniam, OVARoad Safety, Malaysia.

(5) Session 9 Urban Safety Chairman: Dr Tappan Datta, Wayne State University, USA New guidelines on collision prevention and reduction and UK-MoRSE Mike Mounfield, Institution of Highways and Transportation, UK A low-tech approach to road safety engineering in urban areas Clive Sawers, Traffic Engineering Consultants, UK Speed characteristics and safety on low speed urban midblock sections based on GPS-Equipped vehicle data Saroch Boonsiripant, Georgia Institute of Technology, USA Road accidents in Dhaka, Bangladesh: How to provide safer roads? M. Shafiq-Ur Rahman, Jahangirnagar University, Bangladesh Comparative analysis about speed reduction on the different types of the traffic calming measures in Slovenia Marko Rencelj, University of Maribor, Slovenia. Session 10 Education and Training Chairman: Dr Evangelos Bekiaris, Hellenic Institute of Transport, Greece Why traffic as a system is an important conceptual contribution to road safety teaching? Maria Isoba, Luchemos por la Vida, Argentina A new concept on the integration of driving simulators in driver training The train-all approach Maria Panou, Hellenic Institute of Transport, Greece Preparation of specialists from different community sectors related to road traffic injuries prevention. Cuba 2004 2006 Mariela Hernandez-Sánchez, INHEM, Cuba Education and training of highway safety professionals in the United States Martin Lipinski, University of Memphis, USA A novel program to enhance safety for young drivers in Israel Tsippy Lotan, OR YAROK, Israel. Session 11 Crash Recording Systems and Safety Auditing I Chairman: Dr Josef Mikulik, CDV Transport Research Centre, Czech Republic Introduction of highway safety enhancement project in flat area in China Bin Huang, Research Institute of Highway, China Run off the road accidents on motorways in Finland Katja Suhonen, Helsinki University of Technology, Finland A systemic view on Swedish traffic road accident data acquisition system Imad Abugesaisa, Linköping University, Sweden Comparison of highway accidents based on vehicle types in Thailand Chakkrit Kanokkantapong, Prince of Songkla University, Thailand An in-depth analysis of road crashes in Thailand Mouyid Bin Islam, Asian Institute of Technology, Thailand Regional black-spot treatment program A polish experience Krzysztof Jamrozik, National Road Safety Council, Poland.

(6) Session 12 Rural Safety Chariman: Mr Robert Klein, GRSP, Switzerland The challenge of dysfunctional roads upgrading the safety of inter-urban roads John Mumford, iRAP and Reputation Risk Consultants Ltd, UK Implementation of the flashing yellow arrow permissive left-turn indication in signalized intersections David Noyce, University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA Broadening the transport safety agenda: A rural perspective A synthesis of pilot case studies from Sri Lanka, India, Madagascar, Cameroon and Peru Guy Kemtsop, IFRTD, Cameroon Fatality risks of intersection crashes in Bangladesh Upal Barua, Department of Civil Engineering, Canada Use of intelligent road studs to reduce vehicle-pedestrian conflicts at signalised junctions Ho Seng Tim, Land Transport Authority, Singapore. Session 13 Performance and Adverse Effects on Driving Chairman: Dr Astrid Linder, VTI, Sweden Safety performance indicators a tool for better road safety management: The case of alcohol and drugs Terje Assum, Institute of Transport Economics, Norway Situational and driver-related factors associated with falling asleep at the wheel Fridulv Sagberg, Institute of Transport Economics, Norway Random roadside drug testing: A study into the prevalence of drug driving in a sample of Queensland motorists Jeremy Davey, CARRS-Q, Australia Detection and prediction of driver s micro sleep events Martin Golz, Univ. Of Applied Sciences Schmalkalden, Germany Evaluation of a drowsy driving system Anna Anund, VTI, Sweden. a test track study. Session 14 Crash Recording Systems and Safety Auditing II Chairman: Dr Tappan Datta, Wayne State University, USA Transparency, independence and indepth with regard to safety oriented road accident investigation Heikki Jähi, Institute for Transport and Safety Research, France Comparison analysis of traffic accident data management systems in Korea and other countries San Jin Han, Korea Transport Institute, Korea Using GIS technology to enhance road safety in Singapore Hau Lay Peng, Land Transport Authority, Singapore Thailand road safety and introducing public participatory approach for black spot identification Tuenjai Fukuda, Nihon University, Japan Road safety auditing also on existing roads an efficient tool for preventing accidents? Jesper Mertner, COWI Consulting Engineers, Denmark.

(7) Session 15 Road Safety Economics Chairman: Dr. Piet Venter, GRSP, Africa Benevolence and the value of road safety Henrik Andersson, VTI, Sweden The burden of fatalities resulting from road accidents: An epidemiological study of Iran Esmaeel Ayati, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Iran Quantification of accident potential on rural roads: A case study in Rajastahan (India) Ashoke Sarkar, IFRTD, India Evaluating rural road safety conditions using road safety index: An application for rural roads in Thailand Wit Ratanachot, Department of Rural Roads, Ministry of Transport, Thailand The road safety cent Gunter Zietlow, German Technical Cooperation, GTZ, Germany. Session 16 Enforcement Techniques and Speed Management Chairman: Ms Lori Mooren, ARRB Group Ltd, Australia Penalty points systems: Efficient technique of enforcement and prevention Josef Mikulik, CDV Transport Research Centre, Czech Republic Spot speed study along a speed zone on motorway M2 in Mauritius Harvindradas Sungker, CODEPA, Mauritius Factors leading to violation of traffic light rules among motorists in Malaysia S. Kulanthayan, University Putra Malaysia, Malaysia Safety effects of variable speed limits at rural intersections Mohsen Towliat, Swedish Road Administration Consulting Services, Sweden. Session 17 Health Issues and Raising Awareness Chairman: Dr Stig Jörgensen, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway Involvment and impact of road traffic injuries among productive age groups (18-59 years) in Bangladesh: Issue for priotity setting Salim Mahmud Chowdhury, CIPRB, Bangladesh Developing an integer programming sketch to optimize the expenses on promoting the road safety and social traffic culture Hamid Reze Behnood, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Iran Social and information campaigns to improve road safety Barbara Król, Polish National Road Safety Council, Poland The identification of "At-risk" groups for transport-related fatalities across four South African cities Laher Hawabibi, UNISA, South Africa Study of pattern of fatal accidents for safe designing of vehicles Amandeep Singh, Department of Forensic Medicine, India.

(8) Session 18 Human Behaviour and Pedestrians Chairman: Dr Martin Golz, University of Applied Sciences, Schmalkalden, Germany A study examining the relationship between attitudes and aberrant driving behaviours within an Australian fleet setting J. Davey Freeman, CARRS-Q, Australia Road Safety in the Czech Republic is related to human factors research Karel Schmeidler, CDV Transport Research Centre, Czech Republic Pedestrian safety requires planning priority Esther Malini, Larsen & Toubro, India Walkability of school surrounding environment and its impact on pedestrian behaviour Lina Shbeeb, Balqa'a Applied University, Jordan Road accidents and pedestrians: The importance of traffic calming measures in tackling the (in)visible public health disaster in Kampala city Paul Isola Mukwaya, Makerere University, Uganda Closing Session Summary of Global Road Safety Peter Elsenaar, GRSP, Switzerland Closing Address Aram Kornsombat, Deputy Director General, Office of Transport and Traffic Policy and Planing (OTP), Ministry of Transport, Thailand Closing Address Kent Gustafson, Chairman of RS4C organizing committee, VTI, Sweden.

(9) Opening Session Chairman: Dr Maitree Srinarawat, Director General, Office of Transport and Traffic Policy and Planning (OTP), Ministry of Transport, Thailand. Plenary speech on road safety in Thailand Maitree Srinarawat, Director General, OTP Ministry of Transport, Thailand “The pro-active approaches to make our roads safer” Hans-Joachim Vollpracht, Chair of PIARC TC 3.1 (Road Safety) “Safer roads – an achievable goal for all countries” Gerard Waldron, Managing Director, ARRB Group Ltd, Australia “Road Safety in countries with less developed infrastructures” Prof G. A. Giannopoulos, Head Hellenic Institute of Transport, Past president – ECTRI “How can we set and achieve ambitious road safety targets?” Eric Howard, OECD/ITF Working Group on Ambitious Target Achievement.

(10) ROAD SAFETY IN COUNTRIES WITH LESS DEVELOPED INFRASTRUCTURES: Issues and actions to maximize effect with minimum resources 1 . 14th International Conference:. Road Safety on Four Continents. Bangkok, 14-16 November 2007. Keynote Paper by. Prof G. A. Giannopoulos Head, Hellenic Institute of Transport National Center for Research and Technology of Greece Past president, European Conference of Transport Research Institutes - ECTRI. ABSTRACT This paper focuses on the so called “soft” measures for road safety that can be recommended particularly for countries with not so advanced road infrastructure. It makes a review of the principal of these “measures” that have been found to influence road safety in European countries with lesser developed road infrastructures. The selection of the factors and the analysis that follows, is based on accident statistics and their “interpretation” for the last 5 – 10 years in thirteen European countries (among which Czech republic, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Malta, etc). The presentation of the basic statistics and findings is accompanied by comments and reference to the relevant policy issues. Special attention is given to drawing more general conclusions and recommendations that can be taken by road safety related administrations in non-European countries as a guide to developing immediate actions and road safety programmes in a third country. Particular emphasis is given to the development of long term Strategic Plans for the increase in road safety and it is stressed that good coordination among the various government departments that are involved in road safety work, is fundamental. The paper in its final part draws some conclusions and recommendations on road safety programmes always those that are less “capital incentive” and maximize “output” in terms of “impact per unit of investment”.. 1. Most of the work reported in this paper, is based on data and findings of projects performed by the. Hellenic Institute of Transport (HIT) for the European Commission and the Greek Government. The work. and contribution, to collecting the data and the findings of these studies, of the member of HIT Mr. D. Margaritis is gratefully acknowledged.. 1.

(11) INTRODUCTION The issue of road safety is of multiple importance as well as complexity for all countries. For the countries in a stage of development, besides their generally unfinished road and road related infrastructure, there are a number of other negatively influencing factors that prevent them from tackling the issues of road safety efficiently and effectively. As a result they suffer from high accident rates distinctly different from those in countries in more advanced stages of development. European experience shows that this situation need not be so. There are several policies, measures, and actions that can have a markedly positive effect on road safety without the need to wait for the massive investments necessary for the development or upgrading of the necessary infrastructures. These infrastructures, although necessary, for general development of the country and many other reasons, they generally take long times and require considerable resources which are not always there. Many studies (see for example Elvic & Vaa, 2004), as well as reports from the European Union and the US government 2 , have given strong evidence of a consistent decline in accident rates in countries which applied consistently specific actions and measures along a specific plan. One can attribute at least a considerable part of this decline on the effects of several “non-infrastructure” related measures that have been taken in these countries especially after 1995. Accident data, derived from the CARE project database 3 , have been used in order to identify the trends in fatalities/injuries in various EU member countries over the decade (1995-2004). These data refer to accident number, accident fatalities and injuries. We gathered these data for 13 of the 27 EU member countries (that are of most interest to the subject and focus of this paper) and present them in summary form in Annex 1. Looking into the fatalities of the statistics of this group of countries, it is seen that in all 13 of them there was a reduction observed over this time period. Portugal and Greece reduced the fatalities 52% and 33% respectively (constantly through out the years 1995-2004). A remarkable reduction of fatalities is also observed to Estonia and Slovenia (49% and 34 % respectively). In some of the countries there is a remarkable reduction of both fatalities and injuries in the period 1995-2004. These countries are the “old” EU member states: Greece, Portugal and Ireland. In Greece, the number of injured people has been reduced by 31% and in Portugal by 21%. Ireland saw a reduction of 40% in that decade. In the statistics of some of the new members it is observed a big increase in the injured people through out the period 1995-2004. Estonia showed a 34% increase, Latvia 24% and Slovenia 57%. When looking at the number of accidents the picture is somewhat different. The “old” member states and Poland are good performers (Portugal: 19% reduction, Greece: 32%, Ireland: 33% and Poland: 19%). On the other hand, some new EU members 2. For a concise view of road safety measures in the EU and the US: http://ec.europa.eu/transport/roadsafety/road_safety_observatory/profiles_en.htm for EU and: http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov/ for the US ( National Highway Traffic Safety Administration). 3 For details on the CARE project see: http://ec.europa.eu/transport/roadsafety/road_safety_observatory/care_en.htm. 2.

(12) scored poor results regarding the number of accidents. Actually they showed an increase of accidents. Accidents increased for example by 48% in Slovenia, 20% in Latvia and 27% in Estonia. Another interesting study is the so called SUPREME project 4 (SUPREME, 2007) whose objective was to collect, analyse, summarise and publish best practices in road safety in the EU Member States of the European Union as well as in Switzerland and Norway, with a view to encouraging the “take-up” of successful strategies. Finally, as part of the 2001 Transport Policy of the EU 5 , a general target has been set (adopted by all member states) to reduce road accident fatalities in the whole of the Union member countries by 50% by the year 2010. It is the basic premise of this paper - supported by the evidence and experience so far not only in my own country Greece, but also in most of the above mentioned case studies and analyses - that besides the obvious road safety improvements that can be made by better road infrastructure and the Information Communication Technologies applications infrastructure (as part of the so called “Intelligent” Transportation Systems – ITS), tangible results can also be achieved with other “softer” measures. These “softer” measures fall in the following seven categories: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7.. Road safety education & awareness raising campaigns Driver Education, Training & Licensing Rehabilitation and Re-Licensing of existing drivers Better maintained Vehicles Enforcement and monitoring actions Institutional and Organisational strengthening, and Post Accident Care.. These measures can be developed and implemented with relatively less investment and in shorter times than those that for extensive construction of new road infrastructures and networks and extensive application of ITS 6 . 4. For more info see: http://ec.europa.eu/transport/roadsafety/publications/projectfiles/supreme_en.htm and after completion of the project in June 2007: http://ec.europa.eu/transport/supreme/index_en.htm. 5. As set in the EU White Paper "European transport policy for 2010: time to decide" (2001), and kept as a target also in the 2006 revision of this paper. 6. As an example of the difference in approach, we note here the 11 priority measures that were suggested by the EU’s e-Safety Implementation Road-Map Working Group (e-safety, 2006) the deployment of which was recommended in order to improve road safety in EU member countries: Vehicle-based systems • ESC (Electronic Stability Control) • Blind spot monitoring • Adaptive head lights • Obstacle & collision warning • Lane departure warning Infrastructure-related systems • e-Call (automatic in-vehicle emergency call system) • Extended environmental information (Extended FCD) • RTTI (Real-time Travel and Traffic Information) • Dynamic traffic management • Local danger warning • Speed Alert.. 3.

(13) ROAD SAFETY EDUCATION & AWARENESS CAMPAIGNS This is perhaps the first area in which an administration should draw its attention. The two measures are presented together because they have as common “target” the minds of the people (drivers and pedestrians). They have however distinctly different time scales of application the first (education) being a long term strategic measure and the second being “tactical” and “short term” in nature. Educational material for children of school age is normally aimed at high school students of 1st, 2nd, and 3rd years. In addition, there can be a high level of activity in preschool nurseries and kindergartens to teach basic principles of road safety to very small children usually through use of special “traffic parks” which are areas equipped with traffic signs and model roads in which children can learn how to circulate safely (as pedestrians) through play. Special pedagogical material must be produced for the students as well as for the teachers who normally should pass special training through regular organisation of workshops and seminars. For the education of adults, special training programmes can (and have in several European countries been) be introduced. These normally comprise training through specialists that is organised by local authorities and city officials. These educational programmes (for adults) can also include programmes to improve defensive and economical driving skills (Eco-Driving) as well as to focus on practising slippery track driving and risk avoidance skills 7 . There can be no doubt that education of young children as well as of adults in road safety can have a key contribution to improving the safety levels through better and more responsible behaviour of the users of the road infrastructure. For this reason road safety education has now been introduced in secondary schools (and in some cases primary schools as well) in almost all European countries. A number of road safety parks are also in operation in most countries complementing road safety education efforts Road Safety Campaigns are on the other end of the scale as far as the time scale of the results. They can bring in, immediate improvements but their disadvantage is that these improvements are not very long lasting. In Greece, application of the so called “Bob Campaign” against drinking and driving brought immediate results in the 4 years that it was applied 8 . The same campaign took place in several other European countries. In other small European countries (e.g. Slovenia, Estonia) various well known awareness campaigns can be mentioned like for example the “Bodi PreViden” (“Be careful”) campaign in Slovenia that seeks to increase pedestrian's visibility by using reflective strips worn around the arm. There is also a scheme for adolescents to raise awareness on the drinking and driving issue, where playing devices in video clubs test reaction times. There is also the “First ride, safe ride” campaign that promotes awareness of infant and child safety in transport, starting from the trip home from the hospital after birth. Also special TV programmes focusing on road safety problems. 7. In certain small European countries like e.g. Estonia these themes are now also included in compulsory driver education and complement the post-novice drivers’ training period. 8 The number of drivers caught to drive under the influence of alcohol was reduced by 20% in the last two years of the campaign.. 4.

(14) have been broadcast in Estonia on many television channels regularly (e.g. once a week for 40 weeks annually) with good results. Another form of road safety campaigns aimed at younger audiences are the various road safety competitions that take place on television among teams of high school students. There are many examples of good results achieved by television and advertising campaigns. The relatively high cost however, of these actions together with the short term impacts they have make them candidates mainly in cases of specific problem areas or periods of time (e.g. during summer or other holidays when accidents tend to soar). They are also normally undertaken in cooperation with private initiatives and/or Organisations who can share the costs. DRIVER EDUCATION, TRAINING & LICENSING This is certainly an area where a lot of improvement can be made not only during the training of the novice drivers but also (and perhaps most importantly) for experienced drivers too. In the European Union member countries all members now adhere by the EU Directive for drivers’ training no. 91/439/EEC and 2000/56/EC. Through the provisions of these Directives, the new drivers must attend a certain number of theoretical and practical lessons (e.g. 20 hours for private cars) certified by an authorised Driving School. The examination procedures set out in the 2000/56/EC Directive has now been incorporated into the legislation of all member states. This introduces a number of common rules designed to make these exams more in-depth and rigorous. In addition a 10- year renewal cycle of existing driving licences is gradually being introduced. Of most urgent and effective action in this domain are also the training programmes for heavy goods transport drivers especially for driving vehicles carrying dangerous goods. These programmes must comply with international legislation and regulations. Certification for dangerous goods vehicle drivers is now compulsory in most European countries. RE-HABILITATION AND RE-LICENSING OF EXISTING DRIVERS Re-training and re-licensing are notions that are increasingly in the agenda of governments around Europe. The aim is to make existing drivers improve their skills and have an opportunity to re-train in order to become more knowledgeable and more compliant to the new rules and safety regulations. This is known as “rehabilitation” of drivers, and is a practice that is gradually being introduced in the legislation of more and more European countries. Re-licensing is also becoming compulsory for people who already possess a driving licence, and who have committed serious traffic offences (e.g. through the “point system”) or who have been driving with the same license for more than a certain number of years (in most cases 10 years). Implementation of this action is not yet in place in most European countries but it is now being discussed for implementation by the year 2010.. 5.

(15) The rationale for these “re-habilitation” measures is that even experienced drivers do not know the recent advances in vehicle design and capabilities as well as in the Traffic Code and need to refresh their skills regularly. The impacts of these measures are not yet known but they are considered as necessary by more and more governments who introduce them gradually in their legislation. BETTER MAINTAINED VEHICLES This section refers to the better maintenance of vehicles and not the improvement of the vehicles themselves which is obviously not part of the measures mentioned in this paper 9 . Technical inspections for vehicles especially (trucks and buses) may seem a “luxury” for many, but it has been proven that the percentage of road accidents due to a poor technical state of the vehicle (normally the brakes or steering) can be as high as 30% although normally it is less. For countries where the GDP per capita is low, buying new vehicles and maintaining them properly is not the rule. Vehicles are imported second hand from other countries and are used beyond their normal “economic” lives with poor maintenance. Regular technical inspection of vehicles in appropriately fitted “inspection centers” is the norm in developed countries. These “centers” can be privately operated but licensed and supervised by state authorities. In lesser developed countries this practice is still to be implemented and this causes several accidents in which inappropriately maintained vehicles are the main cause 10 . Technical inspection centers is the only course of action here, together with an information campaign and perhaps a more extreme action that of putting a maximum age for the vehicles in order to be allowed to circulate. If technical inspection infrastructure for all vehicles in the country is too costly and time consuming we can recommend that trucks and buses be given priority as experience shows that they are the most prone to accidents vehicles. Under the “better maintained” vehicles category we would also include the “better equipped” vehicles with a minimum of safety equipment which in most developed countries is mandatory and standard in all vehicles. This includes the existence and use of seat belts and why not seat belt reminders. In 2006 the EU issued a new Directive that extends the obligatory use of seat belts to all motor vehicles, including trucks and buses. At the moment front seat belt wearing rates vary between 53% and 92% in the EU member states. Misinformation is part of the reason why belts are not yet always buckled: people think that seat belts are not a necessity in urban locations or at slow speeds. People simply forget to wear seat belts. A percentage of 99% of people who unbuckle don’t fundamentally disagree to use their seat belt but simply need a system that reminds them to use the belt. Various studies showed that seat belt reminders are most effective when they are both visible and audible. But it is less clear, even in the EU, whether seat belt reminders should be installed in all seats (ETSC, 2005). 9. Vehicle design and technology (including technologies for accident avoidance and vehicle infrastructure co-operation which is the object of the major EU programme called “e-Safety”) is currently the subject of intense investment and activity within the EU, and this is met by a joint effort involving governments at all levels, the car and motorway construction industries, infrastructure managers and road users themselves. 10 This problem is usually compounded by the fact that these vehicles are usually overloaded.. 6.

(16) While new cars are increasingly equipped with seat belt reminders, efforts are also being made to promote retrofitting of old cars (ETSC, 2006). Other equipment that is currently being fitted or tested for possible fitting in vehicles that involves automatic speed cuts, speed alerts, alcohol testing, etc are not mentioned here as requiring a more advanced level of technical and organisational infrastructure 11 . In conclusion better maintained vehicles can play a significant role in further improving traffic safety. Changes in legislation for better vehicle maintenance and provision as compulsory, of some basic vehicle equipment (e.g. seat belts), while not so “capital intensive” are very important measures as they generate an enduring (sustainable) effect 12 . ENFORCEMENT Results from a large number of evaluation studies concerning different kinds of enforcement measures in different countries show that specific enforcement measures can have significant effects on accidents both as regards their number as well as the types of injuries (ETSC, 2006). It has been estimated that theoretically, full compliance with the traffic law could reduce road accidents by 50% (ETSC, 1999). However, it must be underlined especially in the context of the lesser developed countries examined here, that penalties for violations can have a positive effect on safety as long as they are applied consistently and objectively. The usual practice especially in lesser developed countries is that enforcement is not applied objectively, and consistently. Offences and penalties are not usually applied uniformly (i.e. to all offenders at all times), and it must be understood that this is by far the most important element of “enforcement”, rather than the level of fines and penalties. According to data presented by projects ESCAPE (Zaidel, 2002), and SUPREME 13 , for several European countries members of the EU, “enforcement” of specific measures of road safety has different impacts on road safety according to the overall state of road safety “culture” and “environment” in a given country. On average, over the number of countries surveyed by the SUPREME project, the following results can be stated (always for European countries): 11. See also the results of the ROSEBUD project (Road Safety and Environmental Benefit Cost and Cost Effectiveness Analysis for Use In Decision making) project. Website: http://partnet.vtt.fi/rosebud/.. 12. Much “new technology” equipment in the vehicles which will be instrumental in the next step in improving road traffic safety, in developed countries and the EU in particular, are not mentioned here. Several of these developments to improved traffic safety in the next 10-15 years include (Rijkswaterstaat, 2003): • Communication and communication technology will play a dominating role (road-vehicle-road and vehicle-vehicle); • Traffic management will be smart and integrated, both ‘horizontally’ (regions, cities) and ‘vertically’ (main and underlying road network); • Information from traffic management will go directly to the vehicle and/or the driver (the development of roadside systems will slow down). 13. Project SUPREME, Thematic report “Enforcement measures” Table 1page 11.. 7.

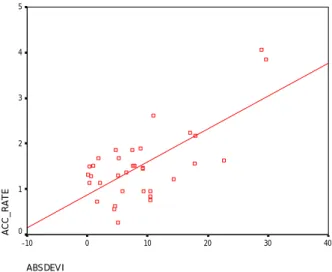

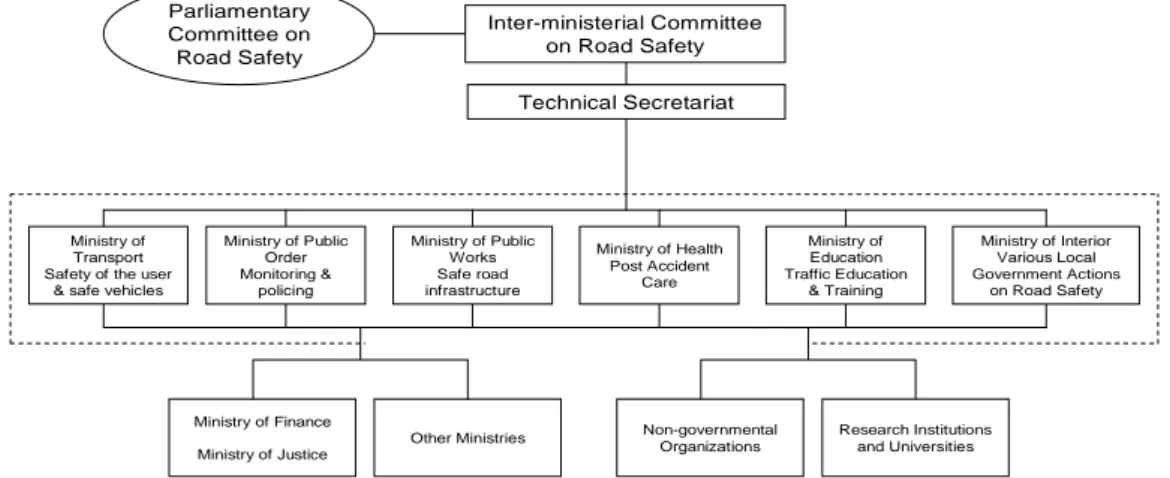

(17) • • • •. Stationary speed enforcement (radar) with an average impact of -14% in fatal road accidents, and -6% in injuries. Patrolling along the highways with – 4% in fatal accidents, and –16% in injuries. Drink driving enforcement with – 9% in fatal and -7% in injuries 14 . Seat belt enforcement with – 6% in fatal and -8% in injuries.. A very important element of enforcement (which can also be considered as “low cost” – at least for the public sector) concerns the working and resting times for professional drivers, both in international and domestic transports. Tachographs, electronic or conventional, on heavy good vehicles are used for working and resting time registration. The inspection and enforcement of these limits is usually done by the Labour Inspectorates and / or the Police, and can be very effective as heavy goods vehicles are very often involved in serious accidents. INSTITUTIONAL ORGANISATION OF ROAD SAFETY This type of “action” is a necessary prerequisite of all actions (“soft” or “hard”) mentioned in this report. There can be no hope of an effective policy making as well as day to day operational management of road safety if there is no appropriate institutional and organisational mechanism in place. Unfortunately, this aspect generally receives little attention but it is perhaps the most important. The experience of several OECD 15 countries in institutional Organization of Road Safety (OECD, 2006) shows a trend towards inter-departmental road safety management and coordination and towards developing and approving long term road safety plans to achieve specific (quantifiable) targets. An OECD survey in 39 countries (OECD, 2006) has investigated the main accident contributing factors and analysed in which areas there is most need for improvements. The factor “lack of political will and coordination” has been identified as one of the key road safety problems. “Coordination” can be achieved by a simple mechanism of a “lean” body such an interdepartmental committee or General Secretariat. Such mechanism should be attached to the highest possible level of governmental authority otherwise it cannot be effective. In several countries it is attached to the prime Minister’s office. For example, in the new 5-year plan for road safety of Greece (NTUA, 2005) the structure shown in Figure 1 is recommended. As shown in Figure 1 all Ministries (Government Departments) which are responsible for the execution and implementation of different parts of the road safety plan, are coordinated by a high-level Inter-ministerial Committee (with a technical secretariat). This Committee is recommended to be attached directly to the Prime Minister’s office (for more details see summary of the Plan in Annex 2).. 14 It is noteworthy that reduction in blood alcohol limit alone was found responsible for -8% in fatal and – 4% in injuries. The usual alcohol minimum limit for drivers is 0.1 milligrams in blood (BAC), or 0.49 mg/lt in breath tests. 15 Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development.. 8.

(18) The EU experience on Institutional and Organisational performance for road safety is given in the thematic report of the SUPREME project with the same name 16 (see also, Elsenaar, Sahlin, 2005). The recommendations include: • Establishment of a central multidisciplinary body responsible for road safety policy making, and formulation of long term action plans 17 . • Empowerment of this body, as the leading agency for coordination between the various government departments as well as other local governmental and non-governmental organizations involved in road safety related work. • Decentralization of road safety work and the creation of “centres of excellence” in various parts of the country, with main objective the implementation of “local” solutions and the adaptation and implementation of the central long term action plan.. Parliamentary Committee on Road Safety. Inter-ministerial Committee on Road Safety Technical Secretariat. Ministry of Transport Safety of the user & safe vehicles. Ministry of Public Order Monitoring & policing. Ministry of Public Works Safe road infrastructure. Ministry of Finance Other Ministries Ministry of Justice. Ministry of Health Post Accident Care. Non-governmental Organizations. Ministry of Education Traffic Education & Training. Ministry of Interior Various Local Government Actions on Road Safety. Research Institutions and Universities. Figure 1: Example of the Road Safety Institutional Structure proposed in the 2nd 5-year. Strategic Plan for Road Safety of Greece (NTUA, 2005).. Finally, an important part of an appropriate Institutional structure for road safety is a mechanism for data collection and statistics on road safety issues. Accidents and specific accident data must be routinely collected and processed so as to have the proper statistical basis for policy recommendations and monitoring of the effectiveness of the various road safety measures and campaigns 18 . The same data will also be used for spot improvements of accident “black spots” as well as for more focussed campaigns. POST ACCIDENT CARE By post accident care we mean the existence in place of mechanisms by which the victims of road accidents can be transported speedily to a hospital or health care unit, or in any way find the medical care they need. Speedy medical assistance to the victims of a road accident can be very important in reducing the harmful effects and is strongly recommended. It is also a “low cost” measure in the sense that such. 16. EU FP6, SUPREME project thematic report: Institutional Organization of road safety, p. 12. The involvement in the work of this body, of as many different actors as possible in road safety work is also recommended. 18 See for example (SWOV, 2006). 17. 9.

(19) improvement (i.e. to the health care infrastructures) is of a more general justification and use, and its costs cannot be attributed only to the road safety “platform”. In order to achieve this, cooperation between the transport and the public health sector is necessary. Road safety issues must therefore be integrated to the public health agenda. The initiative for this might be done by the national health administrations which set guidelines and legislation for financing health promoting activities. In a 2004 report by the World Health Organisation (WHO, 2004), a series of post accident care measures are examined. These measures are certainly recommended here, and this report should definitely by read by those administrations interested in promoting post accident care in a country. THE NEED FOR A STRATEGIC ROAD SAFETY PLAN It must be understood that road safety requires actions and measures at many different levels and affecting many different administrations within the same (national or local) government. All these actions and measures must conform to a common goal and must be prioritised and assigned the necessary resources in order to have a well coordinated and laid out plan. This is normally done through the development of “Strategic Road Safety Plans” which typically cover a 5-year period, and then are renewed for other 5-years. Such Plans include clearly laid out objectives for road safety over the respective time period, the clear specification of actions and measures at all levels of government and non-government Organisations, specific priorities, and the resources that will be necessary to be committed in order to carry out these actions. As an example of such 5-year strategic road safety plan the most recent 5-year plan (i.e. for the period 2006-2010) of Greece is presented in Annex 2 19 . The importance of Strategic Planning in road safety is also underlined by the collective efforts, at transnational level, of the Commission of the EU. The actions there, include the creation of a European Road Safety Action Programme 20 which describes the principles of Vision Zero (meaning zero fatal accidents), and other relevant safety measures (EC, 2003). The programme is the basis for development of the European Road Safety Charter 21 , the White Paper 22 , and the European Road Safety Observatory 23 . The overall objective is to implement an integrated approach to road safety which targets vehicle design and technology, infrastructure and behaviour, including regulation where needed; organise awareness efforts, (e.g. an annual road safety day); continuously review and complete safety rules in all other modes; strengthening the functioning of the European safety agencies and gradually extend their safety-related tasks.. 19. Until the year 2000, Greece suffered from the worst road accident rates among the EU-15 members. In the 5-year period 2000 - 2005, the number of fatalities was reduced by approximately 25% and the number of accidents by almost 30%. The target now is to bring the total reduction of accidents between 2000 and 2010, to 50%. The effort is largely coordinated through 2 successive 5-year road safety plans. 20 http://ec.europa.eu/transport/road/roadsafety/rsap/index_en.htm 21 http://ec.europa.eu/transport/roadsafety/charter/index_en.htm 22 European Commission White Paper European transport policy for 2010: Time to decide. 2001. 23 http://www.erso.eu/. 10.

(20) CONCLUSIONS The creation of better conditions for road safety in a given country requires a well coordinated and longer term programme of actions that fall in two basic categories: “hard” actions involving development of the infrastructures for the safe movement of vehicles and pedestrians, and “softer” actions involving measures that are focused on “building” awareness, road safety behaviour, and better and more efficient mechanisms for the education, training, as well as monitoring, enforcing, and caring (after an accident). The position of this paper has been that countries with lesser developed infrastructures and lack of means to develop them in a reasonable time period should focus on these “softer” measures by way of priority. European experience has been used to show that benefits can be reaped from these measures too, and in relatively speaking short times. The principal areas in which these “soft” measures have been presented are: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8.. Road traffic education at schools Awareness campaigns Driver Education, Training & Licensing Rehabilitation and Re-Licensing of existing drivers Better maintained Vehicles Enforcement of road safety measures and the Code of Route Better Institutional Organisation of Road Safety Better post Accident Care.. It is recommended that countries while in the course of developing their road and road related infrastructures also take a very serious look at the above “soft” measures and proceed with their implementation in the specific conditions of their countries in parallel, and by way of priority. Experience shows that they have a lot to gain…. 11.

(21) References: Dutch Ministry of Watermanagement - Rijkswaterstaat (2003), “Optiedocument Duurzaam Veilig Voertuig”, Transport Research Centre, Rotterdam, November. 2003.. Elvik, R. & T. Vaa (2004), “Handbook of road safety measures”, Amsterdam, Elsevier, 2004. eSafety (2006), EU DG INFSO, Working Group http://www.esafety.effects.database.org/application_13.html. on. e-safety. effects,. European Transport Safety Council – ETSC (2006), “Traffic law enforcement in the EU: an overview”, Brussels, June 2006. European Transport Safety Council – ETSC (1999), “Police enforcement strategies to reduce traffic casualties in Europe”, Brussels April 1999. EC (2003), “European road safety action programme”, Communication from the Commission, Luxembourg, Office for Official Publications of the European Commission, COM (2003) 311 final, 2003. Elsenaar, P. and Sahlin, Ε. (2005), “Institutional sustainability and capacity development within SIDA financed road safety projects”, Swedish department for Infrastructure and Economic Co-operation: Sida-evaluation 05/29, 2005. National Technical University of Athens – NTUA (2005), “Development of Strategic Plan 2006-2010 for the improvement of the Traffic Safety in Greece”, Traffic and. Transport department, Civil Engineering Department, (for the Ministry of Transport, Athens 2005.. OECD, (2006), “Working Group on Achieving Ambitious Road Safety Targets: Country reports on road safety performance”, July 2006. SUPREME project (2007), “Summary and publication of Best Practices in Road Safety in EU Member states: Thematic Reports”, EU funded project Tender No: TREN/E3/27/2005, Contract No: SER/TREN/E3/2005/SUPREME/S07.53754. SWOV (2006), “Traffic accident database”, on the SWOV website, at www.swov.nl. World Health Organization – WHO, (2004), “World report on road traffic injury. prevention”, Geneva, 2004.. Zaidel D (2002), “The impacts of enforcement on road accidents”, ESCAPE project Deliverable 3, http://virtual.vtt.fi/escape/. 12.

(22) ANNEX 1 BASIC ROAD SAFETY DATA AND TRENDS IN SELECTED EU COUNTRIES. Source of data: 1. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development / European Conference of Ministers of Transport, Joint OECD / ECMT Transport research centre, Working Group on achieving ambitious road safety targets, country reports on road safety performance, Paris 2005. 2. European Commission, Road Safety Observatory: Road Safety Country Profiles, 2006.. 13.

(23) 1. Cyprus. 14.

(24) 2. Czech Republic. 15.

(25) 3. Estonia. 16.

(26) 4. Greece. 17.

(27) 5. Hungary. 18.

(28) 6. Ireland. 19.

(29) 7. Lithuania. 20.

(30) 8. Latvia. 21.

(31) 9. Malta. 22.

(32) 10. Poland. 23.

(33) 11. Portugal. 24.

(34) 12. Slovenia. 25.

(35) 13. Slovakia. 26.

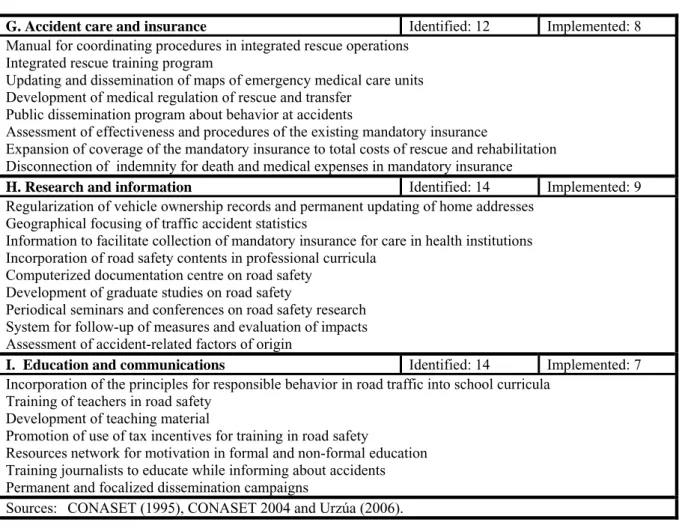

(36) ANNEX 2 The new 5 – year plan for road safety of Greece This is the 2nd Strategic Plan for the improvement of road Traffic Safety in Greece. Its implementation is intended to produce by 2010 a reduction to the road fatalities by 50% as compared to the year 2000. It therefore has set the same target as the white paper on Transport Policy of the EU. The Plan consists of 6 major areas of actions for the enhancement of road traffic safety. Each of them corresponds to an individual action plan. The elaboration and implementation of each action is assigned as the responsibility of a particular Ministry. The six areas of actions are:. 1. Safety of the road user and safe vehicles (Ministry of Transport and Communications) 2. Surveillance of the traffic Safety (Ministry of Public Order) 3. Safe road infrastructure (Ministry of Environment, Physical Planning and Public Works) 4. Post accident treatment (Ministry of Health) 5. Traffic education and education on traffic safety (Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs) 6. Traffic safety actions and local authorities participation (Ministry of Interior, Public Administration and Decentralization) The coordination for the implementation of the plan is given to the so called Traffic Safety Inter-Ministerial Committee, whose chairman is proposed to be the Prime. Minister of Greece and members the six Ministers of the involved Ministries. The responsibilities of the Inter-Ministerial Committee are suggested to be: • • • • • •. Definition of the goals for the improvement of the traffic safety To ensure and to distribute the necessary financing Monitoring the realization of the plan Coordinating the traffic safety programs The submission of a yearly progress report to the Greek Parliament Realization of the communication policy regarding the traffic safety. Two supportive bodies are suggested in order to help the Inter-Ministerial Committee with its tasks: 1. an administrative and technical secretariat, and 2. the Traffic Safety sub-Committee of the Greek Parliament.. 27.

(37) Each of the six areas are further analyzed into short and long term actions as shown in the Table that follows. Table B.1: Specific sub-actions within each Action area Safety of the road user and safe vehicles. (Ministry of Transport and Communications). Short term actions 1. Driver’s behavior control system 2. New traffic rules for the heavy vehicles 3. New traffic rules for the school busses 4. Countermeasures for the enhancement of the young drivers’ traffic safety 5. Countermeasures for the enhancement of the 2-wheeler riders’ traffic safety 6. Countermeasures for the enhancement of the elderly drivers’ traffic safety 7. Incentives for the enhancement of the traffic safety. Long term actions 8. Organizing a group responsible for the coordination and monitoring of road safety actions in the Ministry’s responsibility 9. Upgrading the mandatory technical control of the vehicles 10. Upgrading the training/testing procedures of drivers/driving instructors 11. Modification of the law framework regarding traffic safety 12. Drivers/vehicles databanks 13. Driver’s medical data record 14. Research on accident causation. Surveillance of the traffic Safety. (Ministry of Public Order). Short term actions 1. Higher frequency of traffic controls 2. Thorough and complete controls 3. Regular registration of controls and traffic offences. Long term actions 4. Organizing a group responsible for the coordination and monitoring of this Ministry’s actions 5. Upgrading Police services and equipment 6. Improvement of the accident registration system 7. Improvement of the accident emergency system 8. A holistic traffic monitoring system 9. A training/control system for often traffic rule violators 10. Upgrading the Rescue department services. Safe road infrastructure. (Ministry of Environment, Physical Planning and Public Works). Short term actions 1. Low cost countermeasures 2. A program for the maintenance and improvement of the road network. Long term actions 3. Organizing a group responsible for the coordination and monitoring of this Ministry’s actions 4. Operation plan in dangerous traffic areas 5. Road network record 6. Development of a system for maximum speed limits 7. Traffic safety modifications in urban areas 8. Control of traffic safety 9. Road network rules and technical specifications. Treatment after the accident. (Ministry of Health and Foresight). Short term actions 1. Creation of a network for emergency calls 2. Development of an operation plan and of coordination local centers. Long term actions 3. Organizing a group responsible for the coordination and monitoring of this Ministry’s actions. 28.

(38) 4. Upgrading the equipment of the rescue teams 5. Improvement of immediate treatment of victims in hospitals 6. Systematic recording of information for statistical purposes. Traffic education and education on traffic safety. (Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs). Short term actions 1. Teaching the topic of traffic education in schools 2. Teachers’ education and drafting the teaching material 3. Actions for the promotion of students’ traffic education. Long term actions 4. Organizing a group responsible for the coordination and monitoring of this Ministry’s actions 5. Traffic safety education actions in the Greek Army. Traffic safety actions and local authorities participation. (Ministry of Interior, Public Administration and Decentralization). Short term actions 1. Upgrading the functionality of the Control Groups 2. Enhancement of traffic safety for school busses 3. Implementation of low cost countermeasures. Long term actions 4. Organizing a group responsible for the coordination and monitoring of this Ministry’s actions 5. Development of traffic safety actions by the Local Administration. A public awareness and publicity campaign is proposed too, in order to achieve the active participation and the consent of the public and all other involved parties. In the framework of this so called communication policy, several actions have been planned for the awareness of the public and to draw its interest on traffic safety issues. The major requirements for the successful implementation of the 2nd Strategic Plan and the improvement of the traffic safety in Greece in the period 2006-2010 are: • • • • • • • • •. Political interest (on a Prime Minister level) Sufficient financing Urgent action Proper planning and implementation of the recommended actions Successful coordination of these actions Regular monitoring and evaluation of the proposed actions Commitment and active participation of all parties concerned Consent of the public Sustained duration and coherence of this effort.. 29.

(39) Plenary Session Chairman: Director Gerard Waldron, ARRB Group Ltd, Australia. “Cascading the World Report, the ASEAN Experience” Robert Klein, Regional Programme Director, Asia, GRSP “Developments in highway /traffic safety in the US” Michael S. Griffith, Director, Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration U.S. Dept. of Transportation Road Traffic Safety Management System Standard /ISO-RTS-MSS? Hans Skalin, Swedish Road Administration, Sweden “Road Transport Safety” Martijn Arends, Royal Dutch Shell Plenary speech (UNECE) Marie-Noëlle Poirier, UN Economic Commission for Europe, Switzerland (to be confirmed).

(40) Road Traffic Safety Management System Standard /ISO- RTS-MSS? Hans Skalin SRA, International Secretariat M. Sc. E International Strategist. Quality coordinator / Total Quality Manager ISO/TC 176 Quality Management System 9001 ISO TC207 Environmental Management System 14001 ISO/Strategies Implementation Group 1999-2006 ISO/Strategic Advisory Group 2006Chair for Coordination Group of Management System Standards in Sweden +46 243 75770, hans.skalin@vv.se 2007-08 SRA, GDi, Hans Skalin. 2007-08 SRA, GDi, Hans Skalin.

(41) 2007-08 SRA, GDi, Hans Skalin. 1.200.000 1.70m. 50.000.000. 2 Lane 1,70 Length. 353 km. 14706 km. 2007-08 SRA, GDi, Hans Skalin.

(42) WHO, Geneva,“World report on road traffic injury prevention”: Facts. “In the European Union every year, more than 40 000 people are killed and more than 150 000 are disabled for life by road crashes.”. 2007-08 SRA, GDi, Hans Skalin. WHO, Geneva,“World report on road traffic injury prevention”: Facts. “Road traffic injuries cost European Union countries €180 billion annually, twice the annual budget for all activities in these countries”. 2007-08 SRA, GDi, Hans Skalin.

(43) WHO, Geneva,“World report on road traffic injury prevention”:. Projections indicate indicate Projections • without appropriate action, by 2020, road traffic injuries are predicted to be the third leading contributor to the global burden of disease and injury.. 2007-08 SRA, GDi, Hans Skalin. European Parliament resolution on European Road Safety Action Programme – mid-term review 2007. Road Safety Action Programme (2003-2010) • Halving the number of road accident victims in the European Union by 2010 • a shared responsibility 2007-08 SRA, GDi, Hans Skalin.

(44) Conclusions and recommendations • Vision Zero in Sweden and the sustainable safety programme in the Netherlands are examples of good practice in road safety.. 2007-08 SRA, GDi, Hans Skalin. Safe road traffic. Säker Safe resa journeys. Safe vehicles. Safe speeds. Safe roads/streets. Human biomechanical tolerance limits to violent forces 2007-08 SRA, GDi, Hans Skalin.

(45) Definition • “The field of road-traffic safety is concerned with reducing the consequences of vehicle crashes, by developing and implementing management systems based in a multidisciplinary and holistic approach, with interrelated activities in a number of fields.”. 2007-08 SRA, GDi, Hans Skalin. News story! Sweden has sent a proposal to ISO/CS for a New Work Item on a Road Traffic Safety Management System Standard (similar to the ISO 9001, ISO 14 001 but for road traffic safety) We would like to make sure that you are aware of what is going on, in case that your National Standardization Body (ISO-member) contacts you for your consideration 2007-08 SRA, GDi, Hans Skalin.

(46) What´s a MSS? Used in a proper way it´s a tool that: Create management comittment Bring things in order Factual approach to decision making Systematic process approach Identifies variations- Eliminate variations Demonstrate ability to fulfill goals and demands Demonstrate ability of continual improvement Reduce costs 2007-08 SRA, GDi, Hans Skalin. ISO/Road Traffic Safety Management System Standard/ RTS-MSS? • Internationell acceptance • Holistic approache • Systematic approache • Transparance • Common definitions • Exchange of experience. to Save lifes and sufferings Save costs 2007-08 SRA, GDi, Hans Skalin.

(47) Stages of the development of International Standards • • • • • •. Stage1: Proposal stage Stage 2: Preparatory stage Stage 3: Committee stage Stage 4: Enquiry stage Stage 5: Approval stage Stage 6: Publication stage. 6 weeks ballot. 5 month ballot 2 month ballot. 2007-08 SRA, GDi, Hans Skalin. Application: RTS-MSS • All requirements of this International Standard are generic and are intended to be applicable to all organizations regardless of type, size, products and services provided.. 2007-08 SRA, GDi, Hans Skalin.

(48) Application: RTS-MSS • An attempt to categorise can be to divide into companies and organisations influencing: – the design, building and maintenance of roads and streets – design and production of cars, lorries and other road vehicles including parts and equipment – companies working with transports of goods and people – companies generating significant flows of goods and people – all organisations having personnel working in the road transport system 2007-08 SRA, GDi, Hans Skalin. Institute for Standardization of XX. 2007-08 SRA, GDi, Hans Skalin.

(49) Session 1 Road Safety Plans and Strategies I Chairman: Mr Peter Elsenaar, GRSP, Switzerland Road traffic injury risk in Norway, road safety strategies and public health perspectives Stig H. Jörgensen, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway Initiating road safety policy through participation: A successful experience with a Chilean methodology Alfredo Del Valle, Innovative Development Institute, Chile A conceptual content analysis of politicians’ and safety experts’ judgements of transport safety in public decision making Torbjörn Rundmo, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway A method for improving road safety transfer from highly motorised countries to less motorised countries Mark King, CARRS-Q, Australia Freedom To auto enjoyment contra Freedom From traffic accidents Per A. Loken, Safe Traffic. Info, Norway.

(50) 1. ROAD TRAFFIC INJURY RISK IN NORWAY, ROAD SAFETY STRATEGIES AND PUBLIC HEALTH PERSPECTIVES Stig H. Jørgensen Department of Geography, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) NO-7491 Trondheim, Norway Phone: +47 73591808 Fax: +47 73591878 E-mail: stig.h.jorgensen@svt.ntnu.no. ABSTRACT In Norway, elements of health policy have been aimed at various strategies for health risk reduction. Such strategies have to take several aspects of efficiency as well as equality into consideration. The Vision Zero, visioning zero fatal road injuries and disabilities in Norway by year 2030, introduced a new impetus in road traffic safety promotion with a strong focus on risk minimising. The aims of the study are to present some possible and partial effects of interventions for reducing road traffic injuries (casualties) in Norway in the period 1998–2004 and further discuss some public health consequences in a geographical perspective. Nationwide data on killed and seriously injured motorised road users within the period 1998–2004 are presented. Trends in injury patterns in terms of proportions and rates are presented by place of accident or place of residence. A marked decline is observed in serious injuries in densely populated areas, especially urban areas, while sparsely populated areas show only a small reduction. Elements of a geographical redistribution of risk in disfavour of sparsely populated (urban) areas emerge. The rural population experiences a higher injury rate, by sex and age-adjusted population rates. Urban–peri-urban–rural gradients and differences may be associated with broader physical risk environment factors influencing the system risk factors and possibly socio-cultural factors related to risk-taking behaviour. The proportion of crashes involving non-belted casualties and suspicion of alcohol has not been significantly reduced in the period in spite of being targeted. Risk-taking driving is mostly a rural phenomenon, and appropriate countermeasures do not seem to have achieved the demanded results. The findings are discussed in a risk-minimising and equality perspective, reflecting issues related to urban–rural tendencies to a geographical redistribution of risk and characteristics of the environment that may influence risk-taking behaviour. Some possibilities and limitations in the scope for further progress in road traffic safety promotion are outlined.. INTRODUCTION Despite relatively low injury and mortality rates for motor vehicle crashes in Norway and other Scandinavian countries, road accidents are still a major public health threat. For the most vulnerable group, aged 15–24 years, the proportion of lost life years is only outnumbered by suicides (Statistics Norway 2004). Moreover, the number of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) is high for this age group. For the population taken as a whole, the mortality and morbidity figures outnumber other types of accidents or injuries. During the past decade societal tolerance for fatal motor vehicle crashes as a fatal health risk has been questioned and motor vehicle crashes are seen as unnecessary and avoidable.

(51) 2 health risks. A ‘Vision Zero’, partly adopted from Sweden, envisaging no one being killed or permanently disabled, was launched in the year 2000 (Tingvall & Haworth 1999; Tingvall 1995; Norwegian Public Road Administration 2000). However, further concretising and operationalisation in the short and long run have to be developed. Three main road safety issues or principles have been focused on in Norway. The first is ethics, considering the number of lives lost in traffic accidents is unacceptable under any circumstances. The second is science, emphasising the limited human ability in the traffic system and physical accident tolerance as the basis for road design and protection against fatalities equity. The third is responsibility, where the road authorities are responsible for developing a road system adapted to rule-abiding road users and non-violent behaviour, and to protect against fatalities due to unconscious errors. The ethical principle has been problematic in terms of neglecting trade-offs and alternative costs in other sectors as well as feasibility (Elvik 1999), and furthermore challenged on the types of ethics taken into consideration (Nihlén Fahlquist 2006). The principles of science and responsibility have implications for the transfer of responsibility from the non-violent and rule-abiding road user to the system management performed by the road authorities. Nevertheless, by introducing these principles a paradigm shift has taken place emphasising a political will towards a drastic reduction in the toll of the road. This approach has parallels in the (new) public health policy of smoothing out structural (system) inequalities in public health risks, such as exposure to pollution, the quality of food and water, etc. The system function perspective, ensuring the road authorities’ duty of improving safety aspects in the road environment may de-emphasise individual responsibility and personal risk taking. For example, behavioural adjustments, which may follow in the wake of road network improvements, such as risk compensation (Wilde 2002), have not been explicitly considered in the follow-up of the Vision in national plans of action (Norwegian Directorate of Public Roads (2006). This article aims to portray nationwide trends in motor vehicle crashes for the most exposed group, motorised users in private four-wheeled vehicles, in Norway for the years 1998– 2004. The patterns are presented based on place of occurrence (accident site) as well as place of residence (road users’ residence). Obviously, the Vision Zero and related intensification of safety efforts can not be directly attributed to the observed changes. Nevertheless, the prevailing countermeasures fall within the arsenals of safety measures, and have strong bearings on shortand long-term road safety activities for various groups and geographical areas.. DATA AND METHODS The study is limited to motorised road users driving private four-wheeled vehicles. Police records of road traffic accidents in the period 1998–2004 from the Norwegian Public Roads Administration are the source of the data. The number of registered killed or seriously injured motorised road users for the period is 5971. This group represents the majority of road users (60%) as stated in the official road accident statistics. (In a few of the following presentations, data for 1999 or 2001 are applied to ensure an acceptable data quality, i.e. completeness.) The completeness of road traffic accident data for severely injured road users in Norway has been discussed and investigated (Hvoslef 1997; Borger et al. 1995). However, there is relatively high agreement between the police records and the de facto numbers for killed and seriously injured automobile occupants. The control of accuracy and completeness of the police.

Figure

Related documents

Dock verkar det inte vara det föräldrarna syftar på när de argumenterar för vikten av att lära sig att umgås med alla sorter, eftersom föräldrarna inte pratar om allt barnen

The Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (2019) explains that there is a need to enhance knowledge among crime prevention stakeholders and highlight that both

Relative trend in percentage of the traffic volume exceeding speed limits and also average speeds, national road network, 1996-2010 (1996=1) Source: The Swedish

The interim target means that the number of seriously injured may not exceed 4,100 in 2020, which corresponds to an annual rate of decrease of almost 3 percent. From 2007 the

In the review of interim targets and indicators of safety on roads (the Swedish Transport Administration, 2012:124) which was conducted in 2012, it is described that a revision of

Share of traffic volume within speed limits on the municipal road network 2012-2013, and the required trend until 2020.. Sources: NTF

Many of the ideas presented here have been suggested and inspired by other Bakhtiari writers, especially Madadi (2014). While several years of work and the contributions of

Human-aware planning can be applied in situations where there is a controllable agent, the robot, whose actions we can plan, and one or more uncontrollable agents, the human