Unleashing the Potential of

Open Innovation in

Family Firms

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Managing in a Global Context AUTHOR: Engels, Elisa (950316-1805),

Herholz, Sina Fabienne (900118-T560) TUTOR: Minola, Tommaso

JÖNKÖPING May 2019

Towards the Explanation of the Ability and

Willingness Dichotomy in Family Firms

i

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Unleashing the Potential of Open Innovation in Family Firms Authors: Elisa Engels and Sina Fabienne Herholz

Tutor: Tommaso Minola

Date: 2019-05-20

Key terms: Open Innovation, Family Firms, German Mittelstand, Ability and Willingness Paradox, Innovation Performance, Heterogeneity

Abstract

Research on Open Innovation (OI) is flourishing and opening the innovation process is increasingly perceived as a vital source for sustained competitive advantage. Nascent research on OI in family firms left us to wonder whether the performance-enhancing effects of OI also hold true for family firms. What we do know so far is despite that family firms typically possess greater ability to innovate, they lack the willingness to do so. Taking this as a starting point, the purpose of this study was to identify sources of family firm heterogeneity, in order to explain how these differences influence their willingness to engage in OI and further assess the overall relevance of OI models for family firms. In an attempt to resolve the innovation paradox, the present study builds upon a multi-theory approach of behavioral lenses, to capture the inherent complexities of family firm innovation. Empirical evidence from a cross-industry analysis of 176 German Mittelstand firms provides strong support for the importance of OI practices in a family firm context. Precisely, we affirm that family firms generate increased performance outcomes when engaging in OI. Our findings unearth a double-edged sword that higher generations foster a family firm’s willingness to engage in OI, but hamper their ability to benefit from it. Our findings are especially relevant in light of current market dynamics and build the bridge between OI and family firm research in an insightful manner. We thereby contribute to solving one piece of the innovation puzzle and identify promising areas for future research.

ii

Acknowledgements

At this point, we would like to take the opportunity to express our appreciation and gratitude to the people who supported us throughout the course of our thesis. Within this master thesis, we reach our last milestone on the two-year journey of our master program. Looking back on two intensive, yet exciting years at Jönköping International Business School, we outgrew ourselves not only professionally but also personally.

We wish to thank our supervisor Tommaso Minola for his support and guidance throughout this final semester. You directed us to be more critical and more profound which helped us to constantly increase the quality of our thesis. Moreover, we would like to express our gratitude to our seminar group for their constructive comments and critical questions to improve this thesis. In addition, we wish to thank the proofreaders for their thorough revisions and insightful comments throughout the finalization process. We further wish to thank ZEW for providing access to the anonymized CIS data.

Finally, we would like to express our gratitude to our family and friends who encouraged and supported us during the whole process. Thank you!

Jönköping, May 2019

iii

Abbreviation

AC Absorptive capacity

CI Closed innovation

CIS Community innovation survey

EIP Economic innovation performance

Exp(B) Exponentiation of B coefficient

GDP Gross domestic product

H Hypothesis

IIP Industrial innovation performance

JIBS Jönköping International Business School

MLE Maximum likelihood estimation

NACE Statistical classification of economic

activities in the European Community

OI Open innovation

OLS Ordinary least squares

R&D Research and development

RBV Resource-based view

RQ Research question

SEW Socioemotional wealth

SME Small and medium-sized enterprise

TMT Top management team

VIF Variance inflation factors

ZEW Zentrum für Europäische

Wirtschaftsforschung

iv

Table of Contents

1

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Research Problem... 3 1.3 Research Purpose ... 5 1.4 Delimitations ... 72

Theoretical Background ... 9

2.1 Open Innovation ... 9 2.1.1 Definition of Innovation ... 102.1.2 Open Innovation in a Nutshell ... 11

2.1.3 Open Innovation in this Thesis ... 12

2.2 (Open) Innovation in Family Firms ... 14

2.2.1 Family Firms and the German Mittelstand – Relevance and Definitions ... 14

2.2.2 Innovation in Family Firms – A Paradox ... 15

2.2.3 Ability and Willingness Paradox ... 16

2.3 Hypotheses Development... 20 2.3.1 Building Block 1 ... 21 2.3.2 Building Block 2 ... 25

3

Methodology ... 30

3.1 Research Philosophy ... 30 3.2 Research Design ... 31 3.2.1 Research Approach ... 31 3.3 Research Strategy ... 33 3.3.1 Survey Research ... 33 3.3.2 Sampling Strategy ... 34 3.3.3 Data Collection... 353.4 Measures and Variables ... 37

3.4.1 Building Block 1 ... 37 3.4.2 Building Block 2 ... 39 3.5 Data Analysis ... 41 3.5.1 Data Cleansing ... 41 3.5.2 Characteristics of Sample ... 42 3.5.3 Analysis Procedure... 43 3.5.4 Assumption Testing ... 44 3.6 Research Quality ... 46 3.6.1 Internal Validity ... 46 3.6.2 External Validity ... 47 3.6.3 Objectivity ... 47 3.6.4 Reliability ... 48 3.7 Research Ethics ... 48

4

Empirical Findings ... 50

4.1 Findings Building Block 1 ... 50

4.1.1 Descriptive Analysis ... 50

4.1.2 Bivariate Statistics ... 52

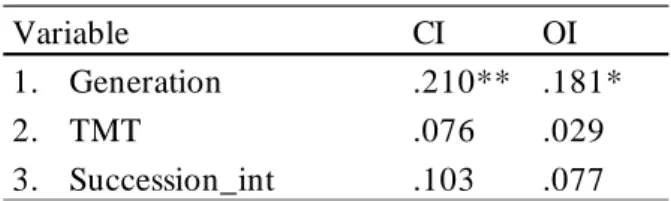

4.1.3 Regression Analysis ... 52

4.2 Findings Building Block 2 ... 55

v 4.2.2 Bivariate Statistics ... 57 4.2.3 Regression Analysis ... 57 4.3 Mediation Analysis ... 61 4.4 Post-Hoc Tests ... 64

5

Discussion ... 65

5.1 Interpretation ... 65 5.1.1 Building Block 1 ... 66 5.1.2 Building Block 2 ... 68 5.1.3 Mediation ... 71 5.1.4 Control Variables ... 72 5.2 Theoretical Implications ... 73 5.3 Practical Implications ... 75 5.4 Limitations ... 775.5 Future Research Areas ... 79

6

Conclusion ... 82

References ... 84

vi

Figures

Figure 1 Knowledge Flows of Open Innovation ... 11

Figure 2 Conceptual Model ... 29

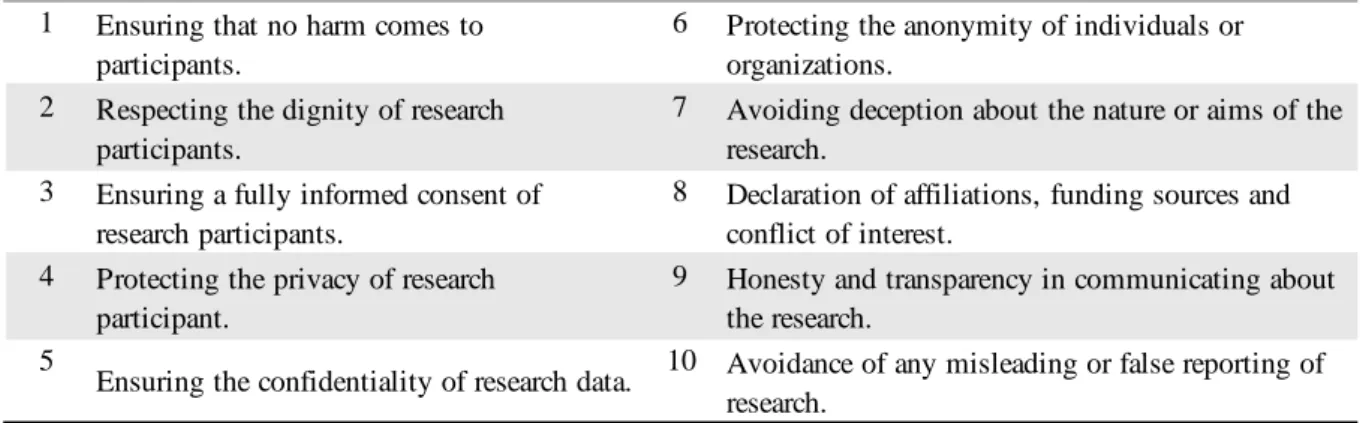

Figure 3 Key Principles in Research Ethics ... 48

Figure 4 Generation ... 51

Figure 5 TMT ... 51

Figure 6 Succession Intention ... 51

Figure 7 Innovation Activity ... 51

Figure 8 Building Block 1: Overview of Models ... 53

Figure 9 Novelty of Product Innovations ... 56

Figure 10 Turnover Share Incremental ... 56

Figure 11 Turnover Share Radical ... 56

Figure 12 Building Block 2: Overview of Models ... 58

Figure 13 Panel A: Direct Effect, Panel B: Mediation Design ... 61

Figure 14 Suppressor Effect ... 64

Figure 15 Results Conceptual Model... 65

Figure 16 Hypotheses Results... 70

Tables

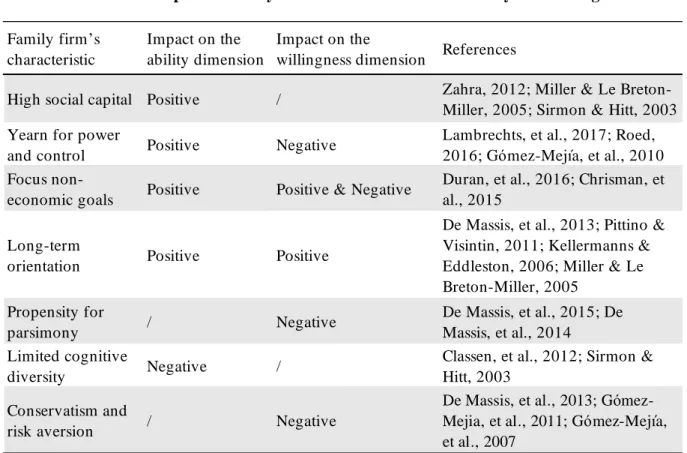

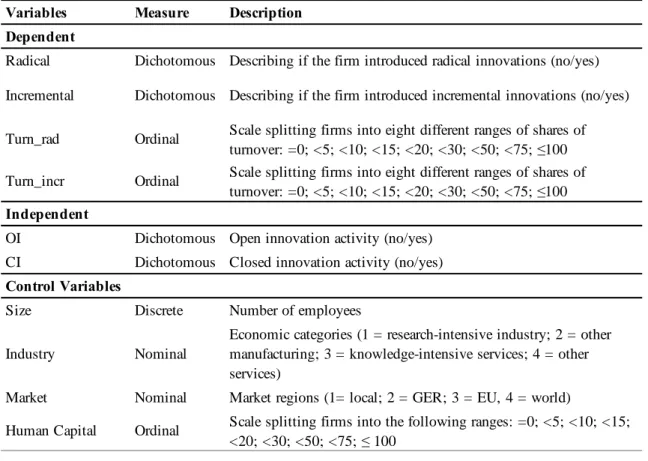

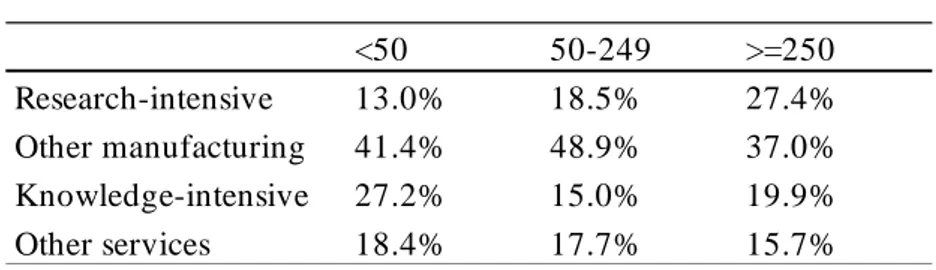

Table 1 Impact of Family Firm’s Characteristics on Ability and Willingness . 20 Table 2 Description Variables Building Block 1 ... 39Table 3 Description Variables Building Block 2 ... 41

Table 4 Distribution of Sample 176 Family Firms ... 42

Table 5 Distribution of CIS Data 2017 ... 42

Table 6 Results Test Multicollinearity Building Block 1 ... 45

Table 7 Results Test Multicollinearity Building Block 2 ... 45

Table 8 Results Bivariate Statistics Building Block 1 ... 52

Table 9 Results Regression Analysis Model 1 and 2 ... 54

Table 10 Results Bivariate Statistics Building Block 2... 57

Table 11 Results Regression Analysis Model 3 and 4 ... 59

Table 12 Results Regression Analysis Model 5 and 6 ... 60

Table 13 Results Mediation ... 63

Appendices

Appendix I: Questionnaire CIS ... 97Appendix II: Informed Consent ... 99

Appendix III: T-Test ... 99

Appendix IV: Assumption Testing... 100

Appendix V: Results Building Block 1 ... 103

Appendix VI: Results Building Block 2... 114

1

1 Introduction

__________________________________________________________________________________________

The introductory chapter provides a brief overview on two highly debated topics, open innovation and family business research. It starts out with a description of the background of the topic and continues with the research problem at hand. Finally, the purpose of this study and two research questions are outlined.

1.1 Background

Markets are becoming more volatile, research and development pipelines are stretching, and low-hanging fruits are becoming more difficult to reach. The designation of globalization and rapid technological changes in today’s environment pushes businesses towards embracing innovation, to ensure economic prosperity and the long-term survival of the firm (Fey & Birkinshaw, 2005). Substantial evidence exists that innovativeness, which is a firm’s “tendency to engage in and support new ideas, novelty, experimentation and creative processes that may result in new products, services or technological processes” (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996, p. 142), today is a key success factor for sustained superior performance. Thus indicating that innovative companies may outperform their competitors (Prajogo, 2006; Kumar & Sundarraj, 2016).

Traditionally, innovation took place within firm boundaries. Internally confined knowledge was placed inside a ‘black box’, assuming that this knowledge is indeed the source of superior performance. This strategy worked well, yielding a high return on investments until the world entered a new century, in which knowledge was used from both in- and outside of the company’s boundaries (Chesbrough, et al., 2006). Since the 2000s, companies became more globalized and customer needs became more complex. Their focus shifted from product-orientation to event-product-orientation. As a result, firms expanded their value chains from vertical to horizontal integration; from exclusion to inclusion; and from closed innovation (CI) to an open approach to innovation (Chesbrough, et al., 2014).

This paradigm shift has been named Open Innovation (OI), where firms leverage external knowledge for their innovation processes, rather than relying entirely internally as well as letting unused internal ideas and technologies go outside for others to be used in their business

2

(Chesbrough, 2003). Thus, OI captures a two-way flow of knowledge from the outside to the inside of a firm (inbound) and from the inside out (outbound).

For years, OI has experienced a strong increase in attention by academic literature (Hosseini, et al., 2017; Dahlander & Gann, 2010; Chesbrough & Bogers, 2014). In particular, special attention has been drawn to the inbound dimension, such as licensing in intellectual property, collaborations, or strategic alliances and its immediate benefits on firm level (West & Bogers, 2014). As such, the importance of inbound OI activities can be seen from its positive effect on a firm’s innovation performance, measured by new product developments, innovation radicalness, as well as patent applications (Lahiri & Narayanan, 2013; Un, et al., 2010), which ultimately increases a firm’s competitiveness (Spithoven, et al., 2010). However, a large proportion of OI research has been conducted in large firms, making such findings fairly general and not applicable to other contexts. Thus, despite abundant attention of OI in multinationals, which led to important insights into the usage of externally sourced knowledge to accelerate innovation, a very particular type of firms remains understudied: family firms. Being the most wide-spread organizational form in the world (Astrachan & Shanker, 2003) with a tremendous economic relevance (Villalonga & Amit, 2008), family firms are renowned for their highly idiosyncratic behavior, which renders them different from nonfamily firms (Kotlar, et al., 2013). Following these premises, there are strong theoretical reasons to believe that the nature and outcomes of OI are different in family firms to that of their nonfamily counterparts.

Certainly, extant research has shown that patterns of innovation fundamentally differ from nonfamily to family firms, whereas scholars highlight a distinctive behavior due to the affective value family owners derive from their firm (Block, et al., 2013; Carnes & Ireland, 2013). For example, family governance has been found to cause differences with respect to organizational goals pursued (Zellweger, et al., 2013; Chrisman & Patel, 2012), risk-taking (Zahra, 2012; Gómez-Mejía, et al., 2007) and investment horizons (Lumpkin & Brigham, 2011), all of which are important determinants of innovation activities. It follows that findings and developed theories concerning the performance outcomes of OI with reference to firms that are not family controlled may not necessarily be generalized to family firms. More precisely, we expect that the outcomes of OI are not readily applicable to family business conditions.

3

1.2 Research Problem

Family firms have often been portrayed as conservative firms, which are reluctant to invest in innovation, and are ultimately perceived to be less innovative than other types of organizations (Economist, 2009). However, substantial evidence exists that more than half of the most innovative firms in Europe are controlled by a family (Forbes, 2018). As an example, a specific context in which family firms out-‘innovate’ and outcompete the global market is the German Mittelstand. Being globally recognized for its innovation behavior, German family businesses represent the most important component of the German economy (De Massis, et al., 2018).

Owing to the importance of innovation for long-term economic growth, which seems even greater in family businesses, with their vision for continuity and transgenerational succession (Chua, et al., 1999), scholars and practitioners are paying increasingly attention to innovation in family firms (Kotlar, et al., 2013; Classen, et al., 2012). Nonetheless, research on innovation in family firms remains scarce and results are inconsistent (De Massis, et al., 2013). Scholars interested in understanding family firm innovation mainly investigate the effect of family involvement in two broad areas of inquiry: innovation input and innovation output. Thereby studies collectively show remarkable differences in innovation behavior between family and nonfamily firms, that is family firms typically invest fewer financial resources in innovation (Chrisman & Patel, 2012; Classen, et al., 2012) but achieve higher innovation outcomes than their nonfamily counterparts (Duran, et al., 2016; Block, 2012).

Scholarly work suggests that innovation in family firms is characterized by a paradox, stating that family firms tend to have greater ability to pursue innovation compared to nonfamily firms, but lower willingness (Chrisman, et al., 2015), which is often attributed to their risk aversion or reluctance to share control (De Massis, et al., 2015). These concerns may complicate especially OI practices, which imply the restriction of a firm’s control over the innovation process (Chesbrough, et al., 2006) and threaten their family-centered non-economic goals (Kotlar, et al., 2013). Therefore, scholars argue that the propensity of family firms to turn to external sources is lower than in nonfamily firms (Nieto, et al., 2015; Pittino & Visintin, 2011).

Nevertheless, behavioral models take a closer look at family firm behavior and the peculiarities of this risk-aversion and find that family firms often act risk-averse and risk-friendly at the same time (Gómez-Mejía, et al., 2007). Families seem to maximize their non-financial returns, which

4

can lead them to forgo financially promising opportunities. Scholars describe these returns as the family’s socioemotional wealth (SEW), which refers to the family’s affective endowment and the non-economic value they derive from their ownership (Berrone, et al., 2012). SEW is said to affect organizational choices on multiple levels, one of which is the willingness to rely upon external knowledge sources (Kotlar, et al., 2013; Gómez-Mejia, et al., 2011). For example, evidence indicates that in pursuit of preserving SEW, family firms develop strong concerns about potential control losses, which may complicate collaborative relationships with external partners (Almirall & Casadesus-Masanell, 2010). However, recent discourse also stresses the multidimensionality of SEW, suggesting to consider non-economic aspects beyond firm control when studying family firms (Berrone, et al., 2012). Following this, behavioral studies which build upon a family firm’s unique characteristics such as long-term orientation and vision for transgenerational continuity, affirm that family firms are willing to rely upon external sources to improve future SEW (Miller, et al., 2008; Gómez-Mejía, et al., 2007). This underlines that the propensity to acquire and commercialize knowledge outside of the company’s boundaries varies not only between family and nonfamily firms, but also among family firms, which supports the long-standing fact of family firm heterogeneity (Melin & Nordqvist, 2007).

In this regard, scholars call for research to identify the sources of heterogeneity in family firm innovation and unveil the underlying mechanisms (De Massis, et al., 2015). Accordingly, scholars suggest employing an essence approach to studying innovation in family firms, which goes beyond investigating the effect of family ownership and management but adds intentions and goals of a family firm (De Massis, et al., 2013; Brinkerink, et al., 2017). So far, scholars often neglected the influence of family intentions and non-economic goals on family firm's propensity to rely upon external sources for innovation, which may partially explain inconsistencies and empirical indeterminacies (Chrisman & Patel, 2012). Nevertheless, the relative importance of a family firm’s economic and non-economic goals differs between family firms, hinging on ownership and management structures, which ultimately account for heterogeneous innovation outcomes (Zellweger, et al., 2013). Thus, studying contingencies which affect the influence of a dominant family coalition, such as the inclusion of external managers in management, might help to explain differences among family firms (Roed, 2016).

To date, scholars highlight the need to continue the stream of studies that link OI and established theories of innovation and management (West, et al., 2014; Huizingh, 2011). So far, only a few studies started to examine OI activities in a family business context. To our best knowledge,

5

only two empirical studies have been conducted to explore how family firms execute OI, which are both of qualitative nature (Casprini, et al., 2017; Lambrechts, et al., 2017). While providing a first understanding of how family firms engage in OI, a common limitation of a case study design is that it makes the generalizability of findings somewhat limited. Apart from this, few fragmented contributions focus on more specific aspects such as the acquisition of external resources (Kotlar, et al., 2013) or search breadth in innovation (Classen, et al., 2012). Common findings are that family firms search and acquire less technological resources than their nonfamily counterparts (Nieto, et al., 2015; Kotlar, et al., 2013; Classen, et al., 2012). More specifically, Nieto, et al. (2015) show that family businesses are less inclined to turn to external sources for innovation, which is strengthened by Kotlar’s, et al. (2013) findings who state that family firms acquire significantly less external Research & Development (R&D) than other companies. Clearly, the discussed studies offer first insights into the topic of OI in family firms, however, a lot remains to be uncovered concerning an OI model’s relevance for family firms, which is why there have been renewed calls for OI research in family firms (Brinkerink, et al., 2017). Given a family firm’s economic relevance and their renowned idiosyncratic behavior, which points to several indices that family firms indeed may be able to positively benefit from OI, there is a need for studies that shed light on the unique nature of OI in family firms and its effects by accounting for heterogeneous behavior among family firms.

1.3 Research Purpose

To the above outlined background and following recent calls to gain a deeper understanding of the ability and willingness dichotomy of family firms in OI research, the present study aims to shed light on a family firm’s willingness to engage in OI and whether family firms are able to benefit from it, while recognizing sources of heterogeneity among family firms. Within this thesis, we focus on the inbound dimension of OI, whereas family firms access externally sourced knowledge to generate a competitive advantage and ultimately benefit from increased innovative performance (Chesbrough, et al., 2014; Spithoven, et al., 2013). We further fundamentally emphasize the role of the family in the innovation process, as "without the recognition of the importance of the family system, we are left with a partial and incomplete view of the family business" (Zachary, 2011).

Given the fact that the theoretical landscape for examining family effects is highly mature, we follow recent calls to build upon multi-theory approaches, in order to elucidate family business behavior from different perspectives and to capture the inherent complexities of family firm

6

innovation (Miller, et al., 2015). This is highly important as we respect not only the significance of the family system but also account for family firm heterogeneity. Therefore, we choose a behavioral point of view, building upon three theoretical schools of thought, being behavioral agency theory (Wiseman & Gomez-Mejia, 1998), stewardship theory (Miller, et al., 2008) and its effects on SEW (Gómez-Mejía, et al., 2007).

In light of a solid base of theoretical lenses to purposefully examine the family effect on OI activities and innovation outcomes, the purpose of this study is from explanatory nature. Taking the ability and willingness dichotomy (Chrisman, et al., 2015) as a starting point, we seek to explain and understand sources of family firm heterogeneity and how these differences in family firms influence their willingness to engage in OI. As such, we aim to test the effect of contingencies on a family firm’s willingness to conduct OI practices and further assess the overall relevance of OI models in terms of innovation outcomes. Thereby, we aim to offer reliable conceptual findings of OI in family firms and important insights into the highly noticed ability and willingness dichotomy. By extension, this study is set to model the following influences, in order to better understand and explain family firm behavior in OI:

First, following the contingent-based perspective of Chrisman et al. (2015), we test the effect of different contingencies (ownership, management, intrafamily succession intention) on a family firm’s willingness to engage in OI. Existing academic literature proposes that family businesses possess unique characteristics, which significantly affect their behavior (Chrisman, et al., 2015). Therefore, we conjecture that family firms differ according to their motivations and goals for the business, which ultimately influence strategic business decisions. Further, contingent factors, such as a firm’s management structure or the owning generation, may contribute to causing these differences of family firm behavior. Since we presume such factors play a pivotal role in explaining a family firm’s willingness to engage in OI, we aim to model and test three important contingencies which may represent drivers of heterogeneity.

Hence, the research question follows:

1) What is the influence of contingent factors (ownership, management, intrafamily succession intention) on a family firm’s willingness to engage in OI activities?

Second, we empirically link the innovation activity, open or closed, to innovation performance. Given the fact that family firms tend to have high ability to engage in innovation (Chrisman, et

7

al., 2015), assessing whether these premises also hold true for OI, generates important insights concerning the relevance of OI models for family firms. This is especially interesting in light of the importance which family firms tend to put on the conservation on their SEW (Gómez-Mejía, et al., 2007) leading them to be strongly concerned about potential control losses. Consequently, we model the relationship between a family firm’s innovation activity, that is whether they innovate in isolation (CI) or rely upon external sources for innovation (OI) – and innovation outcomes, measured by the novelty of product innovations and turnover share from new innovations. Thereby, we aim to get a first understanding of a family firm’s ability to benefit from OI models, by measuring the innovation outcomes of OI compared to CI.

Hence, the research question follows:

2) What is the relationship between the innovation activity (closed or open) and the innovation outcomes in family firms?

By answering these two research questions we aim to derive a better understanding of explanatory mechanisms linking OI and family business research. We test our conceptual model on the German Mittelstand, which represents an ideal testing ground given its strong innovation behavior, outcompeting the global market (De Massis, et al., 2018). In this sense, it offers a solid data basis to reassess rather ambiguous results in family firm innovation literature.

1.4 Delimitations

This thesis is prone to some boundaries, which narrows the focus of this research. This is particularly important for this thesis considering the complexity and multidimensionality introduced by family firms. Thus, in the following, we will set the scope of this study.

To begin with, we take the willingness and ability dichotomy in family firms as a starting point for our thesis. Since several scholars agree that family firms tend to have higher ability but lower willingness to engage in innovation, further investigation on a family firm’s willingness is particularly of interest for this thesis. Building upon previous family business research, we conjecture that family firms possess unique characteristics that can help or hinder them to engage in OI and to benefit from it. How these characteristics influence a family firm’s willingness to engage in OI may be explained through contingent factors that affect family firm behavior (Chrisman, et al., 2015). Since family firms are said to be well suited to effectively manage innovation, we especially shed light on differences among family firms by testing them

8

as contingencies which ultimately has an effect on a family firm’s willingness to engage in OI. Nevertheless, we do not take a family firm’s ability to manage innovation for granted. Therefore, we reassess existing findings into a new context, to justify whether these premises also hold true for OI. Hence, while acknowledging both dimensions, the differences in family firms (ownership, management, succession) are tested within the willingness dimension.

Following recent calls to follow an essence approach when studying family firm innovation, we examine the following three contingent factors within this thesis: ownership, management, intrafamily succession intention. We recognize that family firm innovation behavior can be described as a function of contingent and situational factors (Roed, 2016), however, we do not cover all of them within this thesis. In this regard, we do not aim to fully describe what is driving family firms to engage in OI, we rather focus on three distinct factors (ownership, management, succession) to derive nuanced findings on their influence on a family firm’s willingness.

Moreover, this study focuses on the inbound dimension of OI, since these practices were found to be more prevalent (Van de Vrande, et al., 2009), and are the ones that result in increased innovation performance (Spithoven, et al., 2013; Chesbrough, 2003). Therefore, we do not focus on outbound strategies. Additionally, we compare open with closed activities in order to assess the relevance of OI models for family firms. Thus, we do not consider different types of innovation partners (supplier, customers, universities, etc.). Finally, this study focuses on examining product innovations, and not service or process innovations.

In terms of theoretical foundation, we apply a behavioral point of view, since we investigate a family firm’s behavior towards engaging in OI. Therefore, we build upon a multi-theory approach of behavioral lenses (SEW, stewardship theory, agency theory), to infer family firm behavior from different perspectives. We do not deploy a capability angle, or use theories from innovation literature, such as the resource-based view (RBV) or absorptive capacity (AC). These constructs are better suited for investigating the family firm’s ability to manage OI.

Furthermore, this thesis is limited to a quantitative study design. Qualitative research of contingent factors influencing innovation provides so far largely empirical evidence but has not yet been operationalized. Thus, we aim to quantify these findings on the German Mittelstand and make statistical inferences. In this sense, we do not complement our findings through additional primary data collections techniques.

9

2 Theoretical Background

__________________________________________________________________________________________

The second chapter represents the foundation of this thesis. In the theoretical background the reader gets an overview of the open innovation research landscape, followed by the current state of the art literature on family firm innovation. Through a funnel approach, gaps in the academic literature are identified and hypotheses for this thesis are deduced.

OI is not a buzz word anymore – we recognize it all over the place and it is us that will need to understand it in order to pursue it as future managers. Thus, induced by our high interest on the topic, we started to get a first overview of the relevant literature on OI. Originally conceived as a paradigm shift for large manufacturing firms, OI researchers called for more insights on new application areas. Initially neglected, studying OI in a family business context represents a highly interesting, yet unexplored research avenue. In light of the strong emphasis on family business research in JIBS, we were highly motivated to contribute to this research field. Taking this as a starting point, the literature review process was conducted in four stages. First, a systematic literature review was conducted, in order to identify and investigate the relevant literature on family business and OI (Easterby-Smith, et al., 2015). Since knowledge in this research field is scarce, a second, more extensive systematic review of the literature was carried out to identify state-of-the-art literature on family business innovation. For both reviews, the online libraries Web of Science and Scopus were used, whereas we focused on only peer-reviewed articles, in order to guarantee high quality (Kulkarni, et al., 2009). Additionally, the snowballing approach was applied, which is said to be especially powerful for identifying high-quality sources (Easterby-Smith, et al., 2015). As a result, potential articles were sorted, screened and evaluated. A more thorough evaluation of the existing body of research allowed us to analyze and synthesize current knowledge with regards to the research problem at hand, to pinpoint research gaps in the literature. Finally, the theoretical background will start with an overview of the literature on OI, followed by innovation in family firms, and resulting in the highly discussed ability and willingness dichotomy of family firms.

2.1 Open Innovation

The concept of OI has become increasingly popular in management and innovation literature. Since its first introduction by the former Harvard professor Henry William Chesbrough in 2003, there has been an astonishing growth of OI-related publications with numerous articles, special

10

issues, books and conference sessions (Dahlander & Gann, 2010; Enkel, et al., 2009; Laursen & Salter, 2006). Within academic research, the citations to Chesbrough’s (2003) original book “Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology” almost reached 19,000 since its publication. However, the audience for OI does not only include academics, but also managers have shown increased interest in the phenomena (Chesbrough & Bogers, 2014). This underlines the importance of this topic and suggests that OI is being translated beyond academic research into industry practice.

2.1.1 Definition of Innovation

But despite all this growing attention – what is OI and how did it emerge? To begin with, the term innovation has been discussed within different disciplines for decades (Baregheh, et al., 2009; Godin, 2006). Baregheh (2009) defines innovation as: “the multi-stage process whereby organizations transform ideas into new/improved products, service or processes, to advance, compete and differentiate themselves successfully in their marketplace.” (p.1334). Although researchers could not come up with a common definition so far, they agreed on the major purpose of innovation (Baregheh, et al., 2009), which is to remain competitive and strengthen the market position (Baregheh, et al., 2009; Zahra & Covin, 1994; Von Hippel, 1988).

Within the history of innovation, it was initially understood as a rather closed and linear model from the individual entrepreneur perspective that only relied on internal innovation sources. It included the three major linear steps of designing/creating an innovation, producing a marketable product and diffusing the process across the market by commercialization (Rothwell, 1992; Schumpeter, 1942). However, already in the 1960s, numerous criticisms arouse concerning the linearity of the model (Price & Bass, 1969; Schmookler, 1966), suggesting that innovation is not a phenomenon created only by companies, rather companies are part of the innovation process and not the only innovation source. More consistent with early ideas of Schumpeter (1942) on the origins of innovation, researcher recognized that valuable ideas may also originate outside of a company’s boundaries, for instance within smaller companies (Acs & Audretsch, 1988), public research institutions (Lee, 1996) or even customers and end users (Von Hippel, 1986). Such early ideas became more present in today’s fast-paced globalized economy, which we understand as OI (Chesbrough, 2003).

11

2.1.2 Open Innovation in a Nutshell

Thus, in a nutshell, various scholars describe OI as a paradigm shift from the traditional closed process towards an OI approach (Chesbrough, 2003; Lichtenthaler, 2011). Thereby, the focus shifts from internal R&D to the involvement of external entities at some point of the innovation funnel (Chesbrough, et al., 2006). This means that firms acquire more and more external knowledge, which resides outside of the company’s boundaries, to strengthen internal competencies and accelerating innovation processes (Beamish & Lupton, 2009). Several factors have led to the erosion of how innovation activities take place. To name a few: rising mobility of the workforce, easier access to venture capital funds and new technologies - all of which enhance communication and collaboration, thereby increasing world-wide knowledge and the capability of exchange across firm boundaries (Chesbrough, 2003).

In light of these developments, Chesbrough (2003) coined the term OI and defines it as a “distributed innovation process based on purposively managed knowledge flows across organizational boundaries, using pecuniary and non-pecuniary mechanisms in line with each organization’s business model” (Chesbrough, et al., 2014, p. 25). These knowledge flows can involve either inflows to the organization (leveraging external knowledge sources), outflows of knowledge from the organization towards commercialization (externalizing internal knowledge) or both (coupling external knowledge sources and externalization activities) (Chesbrough, et al., 2014) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Knowledge Flows of Open Innovation

12

The two directions of knowledge flows, outside-in (inbound) and inside-out (outbound), represent two distinct categories of OI. On the one hand, inbound OI involves opening up a company’s own innovation processes to various kinds of external inputs and contributions, in order to create new ideas or products (Chesbrough, et al., 2006). This is the most common dimension of OI and includes collaborating with other firms (West & Lakhani, 2008), universities (West & Gallagher, 2006) or even competitors (Faems, et al., 2010), involving customers or end users in the product development process (Von Hippel, 2005), as well as licensing-in intellectual property from other organizations (Bogers, et al., 2012). On the other hand, outbound OI refers to the practice of exploiting capabilities by utilizing not only internal but also external paths of commercialization (Chesbrough, et al., 2014). It requires firms to allow unused and underutilized ideas to go outside of the organization, in order to be used for others in their business. For instance, outbound OI includes spin-offs of new ventures based on prior product development (Chesbrough, et al., 2006) or licensing-out intellectual property to other organizations (Bogers, et al., 2012). The so-called non-pecuniary modes of OI do not include immediate monetary compensation, while pecuniary modes do and are associated with knowledge flows across organizational boundaries (Dahlander & Gann, 2010).

2.1.3 Open Innovation in this Thesis

Following the idea of Chesbrough’s, et al. (2014) inbound and outbound modes, OI essentially is a concept which resides at the level of the organization. Nevertheless, the literature links OI to several related innovation phenomena, for example, innovation communities (West & Lakhani, 2008) or users as innovators (Piller & West, 2014), which do not necessarily embrace the original concept as firm-centric. Certainly, studies on OI present several perspectives on the phenomena that relate to different forms of OI, such as inter-organizational alliances (Faems, et al., 2010), knowledge sourcing (Laursen & Salter, 2006) and collaborations with networks, communities or individuals (Von Hippel, 1986). As a consequence, scholars perceive OI literature running at risk of becoming incoherent and ambiguous (Bogers, et al., 2017). As an example, collaborations represent one dimension of the inbound mode of OI (Dahlander & Gann, 2010). However, collaborations have already been well-discussed in the literature in the context of collaborative innovation, far beyond and earlier than the OI concept was initially coined (Brunswicker & Chesbrough, 2018; Huizingh, 2011; Dahlander & Gann, 2010). As such, collaborative innovation can take many forms and is often associated with similar terms such as alliances, joint ventures, technology exchange, contractual or collaborative agreements, collaborative arrangement, and licensing, as well as coalitions or partnerships (Un, et al., 2010;

13

Das & Teng, 2000; Porter & Fuller, 1986; Mariti & Smiley, 1983). Similarly, collaborative innovation also encompasses a broad spectrum of external parties such as customers, suppliers, competitors, universities and research institutions (Faems, et al., 2010; West & Lakhani, 2008; West & Gallagher, 2006). Chesbrough (2003) captures collaborative innovation as an important element of OI. As a result, confusion about how these different concepts relate to each other arises, which is why further exemplification is necessary. Such observation further underpins critiques on the OI concept, which argue that OI, as introduced by Chesbrough, in fact, is not a new phenomenon but rather ‘old wine in new bottles’ (Trott & Hartmann, 2009). With such a provoking title the authors challenge the OI concept, claiming that companies have always been open in their innovation process. Hence there was no real change from a closed to an open approach, as initially explained by Chesbrough (2003). Indeed, the notion that firms benefit from tapping into external resource bases is not novel (Jarillo, 1989). Many scholars highlight the idea of Joy’s Law that most smart people work for someone else and that knowledge is distributed across society (Hayek, 1945). Empirically, activities to rely upon externally sourced knowledge in the innovation process have been around for decades. For example, Freeman (2013) proposed that R&D laboratories are not ‘castles on the hill’ and further research shows that organizations have always relied on in- and outflows of knowledge (Hargadon, 2003). Thus, for this thesis, we conclude that elements of the OI concept already existed many years ago, but Chesbrough’s (2003) work is seen as a novel synthesis of many previously disparate points being combined to a new paradigm to manage innovation in the twenty-first century.

Not only is literature on OI expanding rapidly, but it is also transforming over time. OI, originally conceived as a paradigm shift for large manufacturing companies, is now applied in various contexts such as smaller companies, universities, research labs and even government agencies (Van de Vrande, et al., 2009; West & Gallagher, 2006). However, not as application contexts are expanding is literature evolving. The majority of OI literature still focuses on OI practices in multinationals (West & Bogers, 2014). For instance, Chesbrough (2003) in his initial work examined OI in high-technology firms such as IBM and Intel, to develop new business opportunities based upon technology sourced from other organizations. Generally speaking, this era so far focused on the adoption and notable success of OI in large firms. However, more recently, attention has been drawn to the effect of family involvement on OI activities with Casprini, et al. (2017) exploring OI in a family business context. Nevertheless, the knowledge base regarding the effectiveness of OI practices in family firms is not yet lighted.

14

2.2 (Open) Innovation in Family Firms

2.2.1 Family Firms and the German Mittelstand – Relevance and Definitions

In the literature, family firms are often presented as traditional firms, who follow conservative strategies (Sharma, et al., 1997), shy away from seeking new opportunities and are ultimately recognized as less innovative than their nonfamily counterparts (Economist, 2009). However, substantial evidence unveiled that more than half of the most innovative European firms are indeed in the hands of a controlling family (cf. Duran, et al., 2016). Although exact numbers for the prevalence of family businesses vary, research consistently underlines that family firms represent the most wide-spread organizational form in the world (La Porta, et al., 1999). Not to mention their economic relevance, contributing substantially to the global gross domestic product (GDP) (Schulze & Gedajlovic, 2010), also the ubiquity of the family form of governance is of high interest for scholars (Villalonga & Amit, 2008).

A well-known example of family firms is the German Mittelstand, which is globally recognized for its strong innovation performance and therefore of high interest for further investigation (De Massis, et al., 2018). In the past, the German Mittelstand, which includes owner-managed small-and medium-sized enterprises (SME), used to face the problem of resource scarcity, just as any other SME in other countries (Eddleston, et al., 2008). Typically, they lack financial resources and access to human capital (Block & Spiegel, 2011), all of which may inhibit innovation. However, the Mittelstand was able to compensate for these resource constraints by taking strategic choices, as well as partnering with the business ecosystem. Especially due to their local embeddedness, German Mittelstand firms are able to compensate for their prominent lack of skilled human capital access (Glaeser & Gottlieb, 2009). As a result, unlike other SMEs in the world, the German Mittelstand efficiently orchestrates their resources to innovate, leading to strong economic performance (De Massis, et al., 2018).

Today about 91% of all German companies belong to the owner managed Mittelstand and are responsible for 55% of Germany’s economic power by private firms (Family Firm Institute, 2017). Furthermore, 35% of all German revenues (BMWI, 2017) and 40% of all German exports (Venohr, 2015) are generated by the German Mittelstand. Berghoff (2006) defines the Mittelstand according to six characteristics related to governance and socio-cultural factors, among others family ownership and management. When considering also its other characteristics (long-term focus, emotional attachment, patriarchal culture and informality,

15

generational continuity and independence), we can conclude that the large majority of Mittelstand firms are family-owned and/or family managed (De Massis, et al., 2018; Block & Spiegel, 2011). Further evidence is provided by IfM Bonn (2019), the German Institute for research on the Mittelstand, who suggests that the German Mittelstand should be recognized as a synonym for family firms.

As evidenced by several well-known authors, research on innovation in family firms is still in its infancy but has recently received growing attention (Duran, et al., 2016; De Massis, et al., 2013). Overall, numerous definitions of family firms exist, and researchers recognize that family firms are highly heterogeneous (De Massis, et al., 2014). The present study defines a family business according to the essence approach as “a business governed and/or managed with the intention to shape and pursue the vision of the business held by a dominant coalition controlled by members of the same family or a small number of families in a manner that is potentially sustainable across generations of the family or families” (Chua, et al., 1999, p. 25). The reason for choosing this definition is that in addition to ownership and management, it further recognizes the desire for continuity and thereby adds the intentions and goals to family influence. Scholars increasingly underline the importance of including family-specific factors such as succession intention and self-identification in empirical studies, in order to better understand how family involvement influences family firm’s behavior towards innovation (De Massis, et al., 2013). For these reasons, choosing the essence approach as suggested by De Massis, et al. (2013) seems suitable for this thesis, to fully capture family firm’s heterogeneity (De Massis, et al., 2015; Chua, et al., 1999).

2.2.2 Innovation in Family Firms – A Paradox

To date, scholars interested in understanding family firm innovation mainly investigate the effect of family involvement in two broad areas of inquiry: innovation input (R&D investments) and innovation output (new product development/patent registrations). Studies focusing on innovation input use the behavioral agency model to explain that family firms invest less in innovation than nonfamily firms (Chrisman & Patel, 2012; Wiseman & Gomez-Mejia, 1998). On the contrary, research on innovation output, using the RBV shows that family firms achieve higher innovation performance than nonfamily firms (Block, 2012; Sirmon & Hitt, 2003). Recent discourse explains such patterns by means of family involvement and family control, pointing to a paradox, which is labeled as the ‘family innovation dilemma’ (Duran, et al., 2016).

16

Various researchers attempt to illuminate the dilemma of family firm innovation. Already earlier, authors recognized that family influence is a double-edged sword and holds both advantages and disadvantages for innovation activities (Roed, 2016). For instance, Roessl (2005) explored the capabilities of family firms in forming collaborations for innovation. He thereby points out that although family firms possess certain characteristics, which may hinder the willingness to collaborate, family firms hold capabilities which enhance the effectiveness of collaborations. In an attempt to solve the mystery, Duran et al. (2016) sought to understand the specific elements that render family firms different from nonfamily firms. Findings show that factors such as family control, which on the one hand impede innovation input, may, on the other hand, result in higher innovation output. The authors suggest that family firms are in particular very well suited to efficiently use invested resources (Carnes & Ireland, 2013), thus achieving higher innovation output, despite limited innovation input (Uhlaner, 2013). In particular, their high level of control, the concentration on the family’s wealth and non-financial goals affect both the investment decisions and the conversion process of innovation input into innovation output in family firms (Duran, et al., 2016). Consequently, family business scholars are especially directed at understanding how family firms can ‘do more with less’ (De Massis, et al., 2018). Doing so, many scholars highlight the role of external sources to address the family innovation dilemma (Pittino & Visintin, 2011; Classen, et al., 2012).

2.2.3 Ability and Willingness Paradox

A highly contested topic in family business research has been introduced by Chrisman et al. (2015) as the ability and willingness paradox, whereby family firms tend to have greater ability, yet lower willingness to engage in innovation activities than nonfamily firms. Ability is defined as “the family owner’s discretion to direct, allocate, add to, or dispose of a firm’s resources” (De Massis, et al., 2014, p. 346) and willingness as “the disposition of the family owners to engage in idiosyncratic behavior based on goals, intentions and motivations that drive the owners to influence the firm’s behavior(…)” (De Massis, et al., 2014, p. 346). This ability and willingness dichotomy captures various empirical arguments that have been used to explain, on the one hand, the unique resources of family firms that may lead to superior innovation performance (Sirmon & Hitt, 2003), and, on the other hand, the reasons why family firms are less willing to innovate (De Massis, et al., 2015). According to Chrisman et al. (2015), ability and willingness, representing the two key drivers of family governance, may cause the differences in innovation behavior between family and nonfamily firms and among family firms. For instance, family firms are likely to be less inclined to rely upon external sources than

17

nonfamily firms (Nieto, et al., 2015; Kotlar, et al., 2013) and when sourcing external knowledge, family firms differ according to their level of family involvement in their management (Classen, et al., 2012). Hence, a family firm’s distinct traits such as the influence of family ownership on a firm’s goals, their social capital, and their risk aversion influence the way how family firms innovate (Chrisman, et al., 2015). In this respect, academic literature highlights contingent factors (Chrisman, et al., 2015; Nieto, et al., 2015; Classen, et al., 2012), which in turn can affect family firm behavior regarding the willingness and ability to engage and manage OI models. These will be further investigated in the next chapter. The following subchapters, namely ability, and willingness introduce theoretical lenses to understand family firm heterogeneity, as proposed by Chrisman and Patel (2012). Table 1 summarizes the unique characteristics of family firms which may influence the ability and willingness to engage in OI.

2.2.3.1 Ability

In innovation literature, a firm’s ability to manage externally sourced knowledge is usually directed to the AC construct, whereby Cohen and Levinthal (1990) define AC as a firm’s ability to acquire, assimilate, transform and exploit externally gathered knowledge. Profound empirical studies find that AC and firm performance are positively correlated. More precisely, the higher the AC, the higher the innovation performance (Fabrizio, 2009; Murovec & Prodan, 2009). Nevertheless, other constructs such as resource orchestration (Sirmon & Hitt, 2003) and organizational flexibility (Broekaert, et al., 2016) are also used to explain a company’s ability to manage collaborative innovation. In the following, we will discuss family firm characteristics which complicate or enhance their ability to manage OI, but the above-mentioned constructs will not be further investigated, as the focus lies on explaining the willingness dimension.

When studying family firms it is highly important to take into account a family firm’s unique characteristics, in order to understand their ability to manage OI. To begin with, their ability to obtain resources from external entities is strongly influenced by their high level of social capital. Resulting from family firm’s communication, interactions and relationships with different stakeholders, a family firm’s social capital is found to enhance the ability to orchestrate resources from other companies due to a more effective knowledge transfer process (Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2006). For instance, previous studies suggest that external social capital improves alliance and partnership success (Ireland, et al., 2002). Additionally, family firm’s social capital is recognized unique as family firms are generally known for fostering successful long-standing relationships with their stakeholders (Sirmon & Hitt, 2003), thus these relations

18

are more enduring (Miller, et al., 2015), promoting greater ability to engage in OI. Moreover, a high level of control of the firm and a family firm’s attention to non-economic goals is found to enhance the development of capabilities which promote the innovation process (Duran, et al., 2016). To that effect, family firms have shown to foster long-lasting relationships with internal and external stakeholders, eventually increasing human capital (Duran, et al., 2016). High levels of human capital are especially beneficial within an innovation process, as interpersonal interactions of employees increase the effectiveness of knowledge transfer processes within the organization (Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2005). This ultimately leads to the accumulation of tacit knowledge (Acs & Audretsch, 1988), which in turn fosters the ability to engage in innovation. Furthermore, based on the stewardship theory, family firms pursue a main goal of continuity, transferring the business onto next generations, which ultimately increases the long-term orientation of family firms (Miller, et al., 2008). Such long-term mindset enables the firm to be explorative-oriented (Kellermanns & Eddleston, 2006), thus, increasing the ability to nurture partnerships for innovation. In contrary, family firms are often denoted with limited cognitive diversity, which could affect the ability to manage OI (Brinkerink, et al., 2017; Classen, et al., 2012). Due to the fact that management positions are often reserved for family members, the backgrounds of management members are often less diversified. Empirical evidence shows that such undiversified set limits the ability of family firms to perform innovation processes as it is important to deal with complex adaptive environments (Classen, et al., 2012). Most importantly, scholars highlight that cognitive diversity enhances a firm’s AC (Cohen, 1990). Consequently, as family firms show limited cognitive diversity, they have constrained ability to acquire, assimilate and exploit externally sourced knowledge (Sirmon & Hitt, 2003).

2.2.3.2 Willingness

The willingness to engage in innovation is mainly investigated from a rather strategic perspective, dominated by the RBV, which implies that a firm, for example, engages in collaborations for strategic motives such as overcoming resource scarcity, acquiring missing knowledge or to enlarge a firm’s social network (Pittino & Visintin, 2011). When considering family businesses, the decision to engage in OI for innovation is subject to the behavioral characteristics of the main decision maker of the family firm (Classen, et al., 2012). Scholars often refer to the concept of a family firm’s SEW, in order to elucidate the willingness dimension. SEW describes intrinsic non-economic goals family owners and managers feel strongly committed to (Gómez-Mejía, et al., 2007). These non-economic goals ultimately

19

influence organizational choices on multiple levels (Gómez-Mejia, et al., 2011). Today SEW is understood as a 5-dimensional construct consisting of the following elements: family control, family member’s identification with the firm, binding social ties, emotional attachment and the renewal of family bonds through dynastic succession (Berrone, et al., 2012).

Following the behavioral agency theory, family firms tend to be strongly risk-averse with respect to SEW, as they aim to maximize control and minimize external influences, in order to retain their SEW (Gómez-Mejía, et al., 2010). SEW has utmost priority and risky decisions will only be taken if it helps to preserve SEW, thus reducing their willingness to engage in OI (Gómez-Mejía, et al., 2010; Gómez-Mejía, et al., 2007). This also implies that economic goals are subordinate at the expense of long-term economic wealth. In this regard, many scholars highlight family firms yearn for power and control, which leads to the fact that family firms are less inclined to rely upon external sources as this possibly restrict their control compulsion (Gómez-Mejía, et al., 2007). To add, family firms are often recognized as risk-averse entities, due to their wish for the longevity of the family business (Roed, 2016). This risk-averse climate represents a deterrent to an innovation-friendly climate, thus providing another explanation for inferior willingness towards OI (Gómez-Mejia, et al., 2011). Additionally, family firms are often characterized by their overlap of firm equity and family wealth, which significantly impacts investment decisions. Consequently, a family firm’s decision ultimately affects their personal wealth, in both financial and socioemotional terms (Nieto, et al., 2015; Gómez-Mejía, et al., 2007). Therefore, family firms tend to preserve their financial resources, which ultimately limits their inclination to experiment with costly and new business opportunities with uncertain outcomes, known as a family firm’s propensity for parsimony (De Massis, et al., 2013).

The two complementing perspectives, behavioral agency, and stewardship theory (Le Breton-Miller & Breton-Miller, 2006; James, 1999), aiming at explaining family firm’s inferior willingness to engage in collaborations, confirm not only heterogeneity of family firms (Gómez-Mejía, et al., 2007; Bennedsen, et al., 2010) but also point to the conflict of family and economic goals (Zellweger & Nason, 2008). Many scholars stress the variation in family firm’s behavior, leading to different circumstances under which family and economic goals are compatible (Zellweger & Nason, 2008). For instance, on the one hand, if short-term family goals dominate, family and economic goals tend to be more divergent, thus leading to risk-aversion in order to preserve family firm’s SEW (Gómez-Mejía, et al., 2007). On the other hand, if long-term family goals dominate, family and economic goals are likely to coincide, thus leading to increased

20

venturesome behavior of family firms (Chua, et al., 1999; James, 1999). The latter usually takes place if the family firm’s intention for intrafamily succession is strong (Chua, et al., 1999; James, 1999). Hence, decisions are framed with a long-term mindset, leading to a closer alignment between economic goals for long-term wealth and family goals for the perpetuation of family values and legacy (Chrisman & Patel, 2012). Despite intrafamily succession, literature stresses the fact that family firm’s behavior is affected by further contingent factors, particularly governance and owner’s goals, which have a decisive influence on collaboration attitude and behavior (Chrisman, et al., 2015; Classen, et al., 2012).

Table 1 Impact of Family Firm’s Characteristics on Ability and Willingness

Source: Own table

2.3 Hypotheses Development

Within the following subchapters, the hypotheses will be developed, separated into two major building blocks. The building block 1, describes the hypotheses related to a firm’s willingness to engage in OI, whereas the building block 2, describes the hypotheses related to the ability dimension focusing on the relationship of the innovation activity and innovation performance.

Family firm’s characteristic

Impact on the ability dimension

Impact on the

willingness dimension References

High social capital Positive / Zahra, 2012; Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2005; Sirmon & Hitt, 2003 Yearn for power

and control Positive Negative

Lambrechts, et al., 2017; Roed, 2016; Gómez-Mejía, et al., 2010 Focus

non-economic goals Positive Positive & Negative

Duran, et al., 2016; Chrisman, et al., 2015

Long-term

orientation Positive Positive

De Massis, et al., 2013; Pittino & Visintin, 2011; Kellermanns & Eddleston, 2006; Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2005 Propensity for parsimony / Negative De Massis, et al., 2015; De Massis, et al., 2014 Limited cognitive diversity Negative /

Classen, et al., 2012; Sirmon & Hitt, 2003

Conservatism and

risk aversion / Negative

De Massis, et al., 2013; Gómez-Mejia, et al., 2011; Gómez-Mejía, et al., 2007

21

2.3.1 Building Block 1

Scholars find common ground in stating that a family firm’s willingness to innovate can be partially explained by the family’s influence in governance and the goals pursued (Chrisman, et al., 2015; Classen, et al., 2012; Kellermanns, et al., 2012). More specifically, Chrisman, et al. (2015) suggest that the variety of economic and non-economic goals may indeed lead to different behaviors between family firms. At the very essential level, the SEW construct is seen as pivotal for the explanation of the family firm’s willingness to engage in innovation (Bigliardi & Galati, 2018). Following recent calls to build upon multi-theory approaches to understand family firm behavior (Miller, et al., 2015), we acknowledge the complementary perspectives, behavioral agency theory and stewardship theory (Le Breton-Miller & Miller, 2006; James, 1999). Through the lenses of the behavioral agency model, Gómez-Mejía, et al. (2007) propose that when facing the difficulty to choose between a strategic choice leading to economic gains and the choice to preserve SEW even though forgoing financially beneficial opportunities, family firms tend to prefer the latter. In contrary, stewardship scholars find theoretical arguments that family managers exercise stewardship over the well-being and continuity of the family firm, which ultimately makes them more willing to innovate to improve SEW (Miller, et al., 2008; Eddleston, et al., 2008; Arrègle, et al., 2007). Consequently, scholars suggest acknowledging family firm heterogeneity when studying family firms (De Massis, et al., 2013).

Therefore, we follow the work by Chrisman et al. (2015), who claim that contingent factors contribute to explaining family firm heterogeneity. As such, we conjecture that these factors may affect their willingness to engage in OI. In order to provide a fine-grained analysis of the ability and willingness dichotomy, we believe it is fundamental to include these contingencies in the present study (Dyer, 2006; Astrachan, et al., 2002). Hence, in the following, we discuss three major contingencies, ownership, management and intrafamily succession intention.

2.3.1.1 Ownership

The first contingent factor to be considered is the owning generation of the family firm. The owning generation has a major impact not only on the firms’ culture but also on family’s values and goals, which ultimately influence major strategic decisions (Pittino & Visintin, 2011; Schein, 1983). Thus, we anticipate that this may impact their decision to engage in OI.

22

To begin with, literature stresses the fact that a family firm’s founding generation is often associated with a high entrepreneurial spirit (Kellermanns & Eddleston, 2006). Indeed, researchers come to the conclusion that founder-led family firms outperform not only their nonfamily firm's counterparts but also family firms led by later generations (Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2005). A similar stream of research argues that unlike the founders of the family firm, subsequent generations tend to be more conservative in order to retain the family firm’s wealth (Miller, et al., 2015; Alberti, et al., 2014).

However, from a resource-based perspective, the founding generation of the family firm is the one establishing valuable tacit knowledge of the firm that facilitates a competitive advantage (Sirmon & Hitt, 2003). Scholars conclude that this generation is especially strongly emotionally attached to the family business (Astrachan, et al., 2002) and aims to keep the firm under full family control (Duran, et al., 2016). Thus, the founder tends to be more paternalistic (McConaughy & Phillips, 1999), relying mainly on internal resources and refusing external financial sources that could limit the control over their business (Duran, et al., 2016).

Nevertheless, the high degree of tacit knowledge within founder-led firms compensates for limited financial resources (Duran, et al., 2016). As such, since tacit knowledge is often linked to the founder’s personality, scholars argue that successors may be less able to leverage a family firm’s internal resources (Zahra, et al., 2004). Consequently, subsequent generations may be forced to rely upon external knowledge sources in order to push innovation forward (Pittino & Visintin, 2011). In addition, McConaughy and Phillips (1999) and Dyer (1988) state that descendants tend to be more professional and less paternalistic than the founding generation, hence subsequent generations are perceived to be more open towards external sources.

To this background, we recognize that convergent views among researchers exist. However, given the fact that subsequent generations are often characterized as professional and dependent on external knowledge sources in order to innovate, we hypothesize that:

H1a: The lower the owning generation of the family firm, the more likely is the family firm to engage in CI activities.

H1b: The higher the owning generation of the family firm, the more likely is the family firm to engage in OI activities.

23

2.3.1.2 Management

As proposed by the literature, family firms differ significantly concerning their family involvement within their firm’s management (Kellermanns, et al., 2012). According to Astrachan, et al. (2002) the control executed by a family firm’s top management team (TMT) represents a good indicator to understand the strategic influence family members but also external members have in business decisions.

To begin with, the proportion of family members in the firm’s TMT reflects the participation of family members in strategic business decisions. Following the argumentation of Gómez-Mejía, et al. (2007), the more family members in the firm’s TMT, the higher the focus on family goals and values in business decisions, in order to protect SEW. Thus, many scholars argue that family firms may run at risk of overreliance on SEW considerations in decision-making while missing out on important future opportunities (Miller, et al., 2008). Nevertheless, we may also not ignore studies building upon the stewardship perspective, highlighting that family firms pursue economic goals as a mean to follow a rather long-term family goal of securing future SEW and the survival of the firm for subsequent generations (Miller, et al., 2008).

Notwithstanding, recently Classen, et al. (2012) find negative associations between a TMT of only family members and the search breadth for innovation resources. The authors suggest attracting nonfamily managers to create a greater balance between family and business goals. This is because external managers do not fear to diminish family-related goals to protect SEW since they have no family roots in the business (Miller, et al., 2008). Therefore, previous studies come to the conclusion that the presence of nonfamily members in a firm’s TMT shifts the orientation from family goals towards financial objectives, pursuing economic goals and quick growth (Classen, et al., 2012).

Consequently, we assume that management consisting out of only family members is more likely to forgo promising future opportunities to maintain control and SEW, while a TMT including external nonfamily managers has a positive effect on the family firm’s willingness to engage in OI activities. We further find strong support in previous studies (McCauley, 1998; Milliken & Martins, 1996), claiming that due to a more diversified management team, the family firm can benefit from being more inclined towards external sources. Likewise, having a more diversified TMT overcomes a critical disadvantage of family members in the TMT, being