Crisis Communication in the

Time of Corona:

a comparative analysis of

Danish and Swedish public news narratives

Andrea Radlovacki

Media and Communication Studies One-year master thesis | 15 credits

Submitted: 2020-08-30

Supervisor: Anders Høg Hansen Examiner: Michael Krona

ii

Abstract

When the coronavirus disease COVID-19 spread through the world’s countries in early 2020 and dominated the news media, a contrast between how Sweden was combatting the virus compared to other countries who used stricter restrictions quickly became apparent and frequently discussed in media. Through a comparative content analysis, this study aims to investigate how narratives concerning the

coronavirus have been presented in Swedish public news medium SVT compared to its Danish equivalent, DR. Any differences in such news reporting could indicate the possibility of media influence behind why one country implemented and adhered to stricter restrictions than the other did.

Utilizing a quantitative as well as a quantitative approach, 245 articles from Danish and Swedish sources were coded and analysed through theory grounded in situational crisis communication (SCCT). The findings however revealed similar results, identifying the same four key SCCT-narratives in both countries: anxiety,

blame, flattery and care. The theoretical contribution of this study is centred on the

reflection of how these similar results may relate to one another on a societal and sensemaking level. The study ultimately also emphasises the flexibility of SCCT strategies as useful narrative tools for further research.

Keywords

: crisis communication, situational crisis communication theory, SCCT,sensemaking, coronavirus, covid-19, public service media channels, narrative analysis, mediation

iii

Table of Content

ABSTRACT ... II

LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES ... IV

1. INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1THESIS PURPOSE AND RESEARCH QUESTION ... 4

1.2 THESIS STRUCTURE ... 5

2. BACKGROUND AND LITERATURE REVIEW ... 6

2.1DANISH AND SWEDISH SOCIETAL CONTEXT ... 6

2.2LEADERSHIP WITHIN CRISIS COMMUNICATION... 8

2.3PANDEMICS IN THE CONTEXT OF MEDIATED CRISIS COMMUNICATION ... 11

3. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK... 13

3.1SITUATIONAL CRISIS COMMUNICATION (SCCT) ... 14

3.2INTRODUCTION TO NARRATIVE AND SENSEMAKING ... 18

3.3MEDIA MEDIATION ... 19

4. METHODOLOGY ... 20

4.1RESEARCH DESIGN: CASE STUDY ... 20

4.2CONTENT ANALYSIS ... 22

4.3NARRATIVE ANALYSIS ... 23

4.4RESEARCH STRATEGY AND PROCESS ... 25

4.4.1.MATERIAL ... 25

4.4.2.DATA-COLLECTION ... 26

4.4.3INTERPRETATION OF DATA ... 27

4.5RELIABILITY, VALIDITY AND ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS ... 31

5. ANALYSIS AND FINDINGS ... 32

5.1ANXIETY NARRATIVE ... 35

5.2BLAME NARRATIVE ... 38

5.3FLATTERY NARRATIVE ... 42

5.4CARE NARRATIVE ... 44

5.5DISCUSSION AND SUMMARY ... 46

5.51.LIMITATIONS AND FURTHER RESEARCH ... 50

6. CONCLUSION ... 52

7. LIST OF REFERENCES ... 54

iv

List of Figures

Figure 1. Crisis Types Definitions and Cues ... 15

Figure 2. The Model of Theoretical Variables of SCCT ... 16

Figure 3. Crisis Response Strategies ... 17

List of Tables

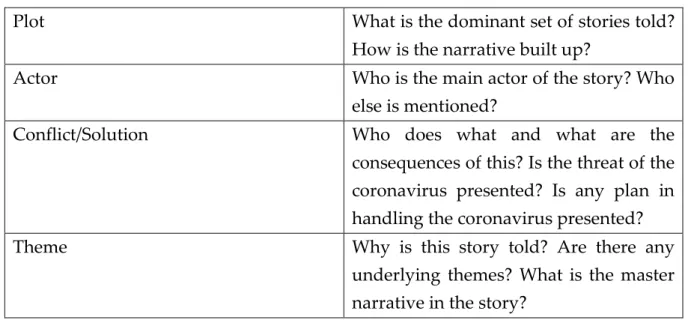

Table 1. Narrative Analysis Model ... 29Table 2 .Coding of SCCT Narratives ... 30

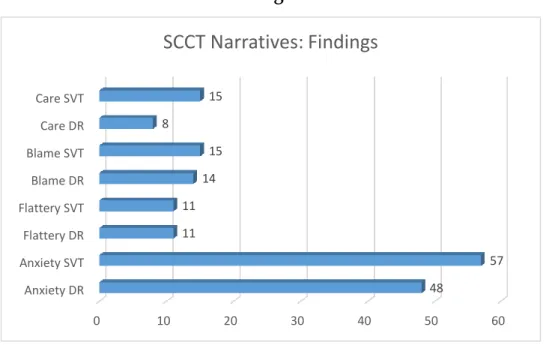

Table 3. SCCT Narratives: Findings ... 33

Table 4. SVT Narratives in % ... 34

Table 5. DR Narratives in % ... 34

1

1.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease, COVID-191, is an infectious disease which emerged in the

end of 2019 and whose worldwide outbreak in March 2020 was labeled as a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO). Apart from the virus’ many repercussions on the world health care and economy, its impact on the global media scene has been unprecedented in terms of how it dominates the news cycles around the globe (Ducharme, 2020). With people now following news coverage to a greater extent than before, the exposure to media and its influence is undisputable. Media indeed plays a vital role during any crisis, as it is the main channel between

governments’ crisis communicators and the public (Seeger, 2007). Through the circumstances surrounding the coronavirus disease, an academic opportunity has presented itself that allows for a fascinating case study on the relationship between public service media and crisis communication in times of the biggest crises of a generation.

As of the summer of 2020, there is currently no vaccine or known treatment available that could help prevent the coronavirus and all that countries can do is to try to contain its spread. In this regard, most countries across the globe have reacted in a similar way: harsh lockdowns (in a variety of forms). With most governments

choosing to close their countries at an early stage and using force-measures to keep their citizens staying at home, such a reaction appeared to be the status quo on how to contain the coronavirus spread. Showing a willingness to take measurable action towards this new threat is furthermore a way for governments of demonstrating strength and co-operation (Krastev, 2020). “Lockdown” as a term is in this case also used for describing measures taken by countries like the Netherlands or Denmark, where most of society has been shut down but no force-measures used to keep citizens locked inside.

1Coronaviruses are a large family of viruses, which include among others Middle East Respiratory

Syndrome (MERS) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). Source: The WHO.The most recently discovered coronavirus causes coronavirus disease COVID-19, which will hereinafter this study be referred to primarily as “the coronavirus”.

2

In comparison with the majority of countries affected, one country has stood out in terms of its initial public crisis response: Sweden. In Sweden, there were no

obligatory shutdown of business, no closure of elementary schools and no

enforcement on keeping people isolated in their homes. The Swedish government is acting on advice from Folkhälsomyndigheten, The Public Health Agency of Sweden that falls under the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs. The front figure for

Folkhälsomyndigheten’s recommendations has been Anders Tegnell, Sweden’s chief

epidemiologist. Self-isolating has been advised for those who are showing

symptoms, and recommendations on how to best stay safe with keeping distances from people in public are continuously being shared by the officials. Such an approach was initially shared with a few other countries, like the United Kingdom and The Netherlands, but by April 2020, Sweden appeared to be the odd country out (Robertson, 2020).

This discrepancy from the rest of the global community did not go unnoticed by the international press. Throughout March and April, leading newspapers around the world such as Le Monde, BBC and The Guardian (see Orange; Savage; Hivert, 2020) were openly questioning and criticizing Sweden’s approach. Through these news channels, the differences between Sweden and the others become, as is customary within media, even more stigmatized and amplified (Hodkinson, 2017:207). As we are living in a strongly politically polarized world, having such differences amplified by media may cause further rifts between countries and the political ideologies that their leadership’s represent. This has previously been particularly exemplified by the difference between how Denmark and Sweden

handled the refugee crisis of 2015 (Hagelund, 2020). By having one country not doing as others do in a global crisis further causes questions from the public whether

stakeholders have the situation under control or not: “People are starting to ask: are others stupid and paranoid? Or is Sweden doing it wrong?” explained crisis

communication expert Orla Vigsø in an interview concerning the coronavirus for The Guardian (Robertson, 2020). Such practices of communication have been

3

continuously monitored by the Swedish Institute (SI) since the start of the pandemic, which throughout the year of 2020 continues to publish bi-weekly reports on how Sweden’s approach to the coronavirus has been portrayed in international media (Svenska Institutet, 2020).

Unlike Sweden, the neighboring country of Denmark was among the first countries in Europe to close its borders in March 2020 and impose a closure of schools and businesses in the early stage of the virus outbreak (The Local, 2020). Head of the Danish equivalent to the Swedish Folkhälsomyndigheten,

Sundhedsstyrelsen, is Søren Brostrøm. Sweden and Denmark are otherwise two Scandinavian neighboring countries that on the surface appear to have a lot in common in the areas of for example language, prosperity, equality and

innovativeness. They have frequently been noted as a “comparative dream” (Mahama, 2018:3) due to their many similarities in socio-cultural heritage. Nonetheless, researchers have over the years identified certain dissimilarities

between the two countries (Vallgårda, 2007) which further makes them appropriate for comparative studies in a most similar case design (Christiansen et al, 2016); Hustedt & Salomonsen, 2017:396; ). It is with this “most similar case design”

argument that Denmark has been chosen as a suitable option against Sweden for the comparative analysis of this paper. Such an analysis will be starting with an

exploration of the two countries’ societal context concerning the relationship between society and state governance.

With national polls showing higher trust in the Swedish government than before the coronavirus crisis (Novus, 2020) in a time when international news are openly questioning the Swedish government’s stance, it is indeed highly relevant and timely to do a comparative study of how another country is currently reporting on the coronavirus compared to Sweden. As online news reporting in present day is immediate as well as globally accessible, the impact of this mediated crisis

communication becomes even more pertinent than if this crisis were to occur in an earlier decade. Identifying whether reporting in Denmark seemingly differs from the

4

Swedish reporting in turn has a strong connection to postmodernist philosopher Michel Foucault’s notion regarding how dominant themes and structures in society are reproduced in media (Hodkinson, 2017:68).

1.1.

Thesis Purpose and Research Question

The purpose of this paper is to compare the crisis communication concerning the coronavirus from the two neighboring countries of Denmark and Sweden. Studying two countries’ crisis communication could be a clue to understanding their different approaches to the pandemic. This would shed light on the role of government leaders and spokespersons for health institutions in national crisis communication through public service media. In these times of a global pandemic there is an

identified need of knowledge on how the media reports on a crisis. DR in Denmark and SVT in Sweden are both national public news broadcasters that receive state funding, which further puts an interesting inquiry on how the public and most accessible news with ties to the state react to and report on a national crisis.

Through the theory of situational crisis communication (Coombs, 2010), a content quantitative as well as a narrative analysis of public news articles from the Danish DR and the Swedish SVT Nyheter will be conducted with the purpose of discerning how Denmark and Sweden’s narratives have differed when reporting on the

coronavirus. The main research question will therefore be the following:

How have crisis communication strategies been mediated through Danish

and Swedish public service news during the coronavirus crisis of spring 2020?

More specifically, what will be studied is content and patterns – how are the key crisis communication strategies mediated and what type of content on the topic of the coronavirus is presented? This implies investigating these strategies, or ways of articulating conditions and actions, that come across in the media reporting’s

messages and discourses (patterns, particular values, ways of putting into words, insight in how relationships between groups and power come across). As crisis

5

communication may sometimes be ambiguous and in need of subjective

interpretation, much focus is given to being clear and transparent on how these strategies are coded.

As crisis communication traditionally also originates from decision makers, certain attention shall furthermore be given to the notion of leadership in crisis and how that is mediated. “Leadership” as a term is for this purpose used for key representatives of leading institutions (i.e position in government or spokespersons and key representatives for health or related institutions). Focusing on the

government leaders and the representative epidemiologists, this study will map out what kind of space, which key messages and discourses these groups occupy in the key institutions or news sites.

Connecting the media activities to situational crisis communication theory, the countries are in different ways trying to test or manage particular crisis strategies. This paper therefore investigates the ways that these strategies are articulated in the news media. In the narrative analysis conducted, the theory of “sensemaking” (Weick, 2001; Vigsø & Odén, 2016; Stieglitz et al., 2018) is adapted, focusing on what collective meaning may be interpreted from the different strategies.

In sum, the findings shall thus be an attempt to understand in what ways the news reporting has perhaps, if at all, mediated different crisis response strategies from the two countries.

1.2.

Thesis Structure

In the following sections, an introduction to Danish and Swedish political culture will be presented, as well as a literature review on previous research that has contributed to the field of crisis communication. The literature review will be

followed by a closer presentation of this study’s theoretical framework. This paper’s method will then be introduced together with a discussion regarding the

methodological choices that were considered. The methodology section also entails a presentation and discussion on data collection and sampling strategies that focus on

6

operationalization. The study’s empirical findings are then presented and followed by a discussion and analysis. Ultimately, the study findings are recognized in a conclusion together with a few finalizing comments and suggestions on future research in the field.

2.

Background and Literature Review

In this chapter, an overview of the Swedish and Danish political culture and societal context will be presented, followed by earlier research on crisis communication. Studying a currently occurring phenomenon contains the obvious disadvantage of having no distance or clarity of hindsight to the subject. Although there have been recent science papers and reports quickly distributed on the subject (SI, 2020,

Heimburg, 2020, Liu & Liu, 2020), as of the summer 2020 we are still in the very early phases of scientific research and data on the coronavirus and the communication and media around it. There is however plenty of studied material on previous pandemics such as the Ebola and SARS, as well as on crisis communication in general. These can indeed offer insight on any patterns in media landscapes during times of crisis, focusing in particular on production, staging and articulation of crisis

communication and its stakeholders. Nonetheless, as the field of crisis

communication often touches upon themes of management and theories concerning image repair (Austin et al, 2012), much of the published material is not particularly relevant to the field how crisis communication works in times of a global pandemic. Research literature with such focus will thus naturally not be presented. Instead, the literature review will instead concentrate on what crisis communication findings are relevant for a community crisis such as the current one of the coronavirus.

2.1.

Danish and Swedish Societal Context

As previously argued, Denmark and Sweden share many similarities and account for circumstances that make them ideal subjects for comparison in research projects. Geographically, they are also linked together via the Oresund bridge, a cross-border

7

access that has fostered collaboration and international business relations between these countries since its opening in 2000 (Savage, 2018). Together with Norway and Finland, the Nordic countries undeniably do share several cultural, economic, political and geographic similarities (Franks, 2020). The existing dissimilarities most relevant to this paper are related to the Danish and Swedish systems of government’s relationship to civil society. While both of these welfare states are part of the

European Union and have parliamentary systems with minority cabinets (Klüver & Zubek, 2018), there has been differences noted that speak to a different type of culture within their government systems. Dating back to the year 1979, Esping-Andersen was among the first to study how Denmark had a shift in attitude towards the existing welfare state system that has otherwise been predominantly considered a positive thing in the Scandinavian countries (Andersen, 2007). The noted rejection of welfare systems in Denmark was in contrast with attitudes in Sweden, where there was no such emergent anti-welfare attitudes. A more recent study on health care differences in Denmark and Sweden similar attitudes were noted: “in Swedish problematisation, the welfare state played a central role and the citizen was seen as part of the community…The Danish approach, on the other hand, implied a more individualistic interpretation… and the state were accorded a less prominent place” (Vallgårda, 2007:45). Considering the more specific realm of political advisors, who are currently in the heart of media surveillance since the coronavirus outbreak, Hustedt and Salomonsen (2017) do note how Swedish advisors have far more direct influence and control over government than their Danish equivalents. The overall number of political advisors is also significantly higher in Sweden than it is in Denmark (Christiansen et al, 2016:1238). Having more of such direct control from advisors gives the country a sense of government unity (Hustedt & Salomonsen, 2017:404). The study also emphasized how having advisors with considerable influence make the topic issues that are presented and discussed become less political and more professional (2017:394). These circumstances could all illustrate the political framework around Denmark and Sweden’s different responses on how

8

to handle a crisis such as the coronavirus on a state level. Sweden, taking in expert advice to a greater extent and having a public community that does not question the system as much as its southern neighbor speaks for a society which has enabled itself of battling a global pandemic in a unique way. “Inherent in Sweden’s social contract is trust in the state, trust by the state in its citizens and trust among citizens”, says historian Lars Tragardh (Economist, 2020), which in turn connects to Rousseau’s idea of a strong social contract. A strong social contract would imply high individual responsibility within civil society (Lundberg, 2017). What this entails is the

government having a natural and consented legitimacy over individuals and that a political order largely can be upheld voluntarily by the conscience of the individual citizens. Societies and citizenships are overall socially different (Boje, 2015), which particularly comes through in the circumstances concerning extents of social contracts.Contrary to Swedes, the Danes are furthermore reported as acting in accordance with their self-image of being anarchists and therefore, in the time of coronavirus, “to be made to comply they need to be told directly” (Johnson, 2020). This referral to Danes as “anarchists” by a non-academic source can however more critically be interpreted as them being a people with stronger sense of individualism, which is in line with other sources mentioned above. In sum, these two countries have entered the political landscape surrounding the coronavirus on quite diverse societal preconditions. The society’s relationship with their governments and other leaders then naturally impact what shapes their crisis response and communication take in extraordinary circumstances. Worth noting is that this summary is indeed a simplified one, as the deeper differences in political landscape between Denmark and Sweden could in fact be subject of an entire thesis in themselves.

2.2. Leadership within Crisis Communication

Defining what constitutes a crisis is straightforwardly narrowed down to the occurrence of a dramatic and unpredictable event that has considerable impact on any ongoing procedures (Coombs & Holladay, 2010:19). “During crises, people turn

9

to the government for leadership including protection, guidance, and a return to stability” (Christensen et al., 2013 in Liu, 2019:140). Communication then becomes a tool for leaders (governments or other influential stakeholders) that is used for coordination and enhancement of crisis management (Johansson, 2017). With this crisis management, the aim is to reduce the impact of the crisis. Various research exists that explains the relationship between the giver and receiver of crisis communication, with a certain emphasis on presenting what practices are most advisable. One dominant theory in crisis communication is so called Situational Crisis Communication (SCCT). This theory looks at variables that should be

considered when selecting crisis response strategies such as, among others: denial, responsibility shifting, excuse and apology (Kyrychok, 2017:55). Focus in crisis response according to the theory should commence with leaders instructing the public, followed by adjusting information in order to help cope psychologically with the crisis (Coombs, Holladay, 2010:40). Such an approach is recommended by many of the authors mentioned below regarding how best to convey crisis information. Leaders who respond to the crisis in a timely matter, all while making sure that the unfolding events are being interpreted to the public, tend to achieve the most impact (Liu et al., 2019:129-130). Within the role of making sure that events are correctly interpreted by the public, leaders have a responsibility of facilitating “sensemaking” (Weick, 2001; Vigsø & Odén, 2016; Stieglitz et al., 2018) – the collaborative and social process whereby meaning is created within situations of high discomfort and

uncertainty. Characterising the process as collaborative and social is connected to how ”actual facts do not have meaning until they are discussed and contextualised” (Stranberg & Vigsø, 2015:95). Facilitating this sensemaking will in turn stem from listening to the audiences’ needs, including being responsive in case there may be existing fake information spreading. What sets the notion of “sensemaking” apart from general attempts of making subjects comprehensible and clear is that

sensemaking is a discipline concept of its own. Its collaborative nature entails “the ongoing retrospective development of plausible images that rationalize what people

10

are doing” (Weick et al, 2005:409). Through the responsibility of sensemaking it becomes equally important to shield the public from any “sensebreaking”, which is what occurs when contradictory information interrupts the process of creating sense for the public (Giuliani, 2016:221).

When further looking into the various do’s and don’ts of leaders in times of crisis, what becomes particularly apparent is the emphasis on transparency and accessibility of accurate, factual information where there exists a vision with the communication (Maal & Wilson-North, 2019). By end of april 2020, Swedish news reported on how Swedish Folkhälsomyndigheten had given the public incorrect numbers on two occassions concerning the coronavirus infect rate (SVT-1, 2020). The first time, Folkhälsomyndigheten adressed the public immediately after the

occurence and explained that it had been an error on their end. The second time, they silently removed on the incorrect report and then republished it with corrections, instead of adressing the error they had caused in the first place (Karlsten, 2020). In these types of situations, Maal & Wilson-North (2019:385) urge that leaders best stay honest and admit to their mistakes – since a large emphasis is put on transparency then such strategies should be upheld. In the research from Maal & Wilson, it is further stressed that leaders should refrain from speculations or personal opinions (2019:387), which has been demonstrated with unpopular reception of the

contradictive narratives of for example president Trump in the US and president Bolsonaro in Brazil (Gerbaudo, 2020). In such cases of leaders and their individual personas becoming the main focus where they ought to be spreading informational facts, sense-breaking tends to occur (Mirbabaie & Marx, 2020:263). With new research findings concerning the coronavirus coming out consistently, leaders in that situation need to be clear on that whatever information is given is based on what they know ”right now”. Having this knowledge of the role of leadership in crisis, it would be difficult studying crisis communication strategies without any focus of how leaders and leadership is manifested in the mediated reporting.

11

2.3. Pandemics in the Context of Mediated Crisis Communication

Continuing a literature review on previous coverage practice of other pandemics, the spread of the SARS disease in 2002, and the Ebola disease between 2014 and 2016 fall within the most recent cases. The outbreak of Ebola originated in West Africa where most of its cases were concentrated, but also spread on in few numbers to some countries in Europe and in the United States, gaining considerable media coverage in western media. By the end of its two-year spread, 28 603 cases had been confirmed infected, with 11 301 dead (Folkhälsomyndigheten, 2016). Ebola has since had another outbreak in Kongo, which started in 2018 and continues to this day (CDG, 2018). SARS, a closely related coronavirus to the current COVID-19, spread across 29 countries and resulted in 774 deaths over the course of its 8-month spread. For media scholars, SARS and the recent outbreaks of the Ebola disease have offered anopportunity for analyzing in what way communication spreads during a crisis in the 21st century. With multiple broadcasting channels available that also range from

traditional news to municipality websites to social media, today’s media audiences indeed demonstrate how crisis communication is a wide-ranging subject with various sources for information. Such a cross-media landscape invites to a “multivocal rhetorical arena composed of various voices” (Rodin, 2018:238).

Nonetheless, basic questions that any person wishes to have answered during a time of crisis come down to: “What do I need to know?”, “What do I need to do today to protect my family?” and “Where do I find information I can understand and trust?” (Ratzan, 2014:149). Such fundamental needs urge crisis media coverage to be clear, based on facts and widely understandable. Re-connecting to the notion of “multivocal rhetorical arena” mentioned above, serious media coverage in times of crisis are still relatively homogenous in terms of following a certain pattern of

reporting, as this is what the public needs. Online news are in this matter a common choice due to their immediacy, spreadability and overall accessibility (Lee, 2005:258).

The audience may most often make conscious efforts to retrieve these answers by consulting its regular choice of media for information seeking, where a subconscious

12

rating of media credibility and accessibility occurs (Vigsø, Odén, 2016:74). This information-seeking need within the public is at its strongest when there exists uncertainty about the possible danger. What follows is a collaborative and social process with one’s peers and surroundings on reception and negotiation of meaning concerning the existing information and what future action to take regarding it (Vigsø, Odén, 2016:82-83). As previously mentioned, this collaborative sensemaking in relation to others has the possibility of being based on a various range of media outlets such as traditional news or social media.

Within these different sources lies also a difference in narrative. In a comparative study of newspaper coverage and news stories shared on social media site Reddit, results showed how speculation that pushed blame and false alarm during crisis was more prevalent in the social media channel (Kilgo et al, 2019:815). The researchers concluded these means as more panic-inducing among the audience. This being said, social media is also presented as a valuable forum where crisis communication can in fact be questioned and discussed among the public. This illustrates a more

collaborative form of sensemaking where people together make meaning of existing data. Still, social media has by a study from Johansson (2018:537) been noted as a form of extension of what is reported in traditional media, and ”foremost a

complement to the already existing channels for crisis communication”. On a study from an earlier Ebola spread, Ungar (1998) discussed how the media generally play on public fears and panic to a greater extent if the crisis in question is far away from the audience. Some type of media framing indeed focuses on risk, blame and

speculation, whilst other is emphasizing solutions and praising efforts of those solving the problem. When close, the media tends to instead present reassuring coverage which would calm the masses – ”The more tangible danger, the less alarmist the content becomes” (Rodin, 2018:245). This is also studied by Kilgo et al (2019 – mentioned earlier) who has compared how social media vs traditional media covered stories about the Ebola virus.

13

Mediated reporting on crises has further been studied by researcher Sherry J. Holladay (in Coombs & Holladay, 2010:159), where she again underlined the importance of media reports as vital tools for informing audiences. Holladay nonetheless stresses the fact that journalistic subjective choices of course influence what to include in stories that are selected for publishing. This in turn affects the effectiveness of traditional media as a tool for useful crisis communication.

Mohamad H. Elmasry and Vidhi Chaudrhi (Ibis: 141) similarly studied how crisis communication strategies concerning image restoration were manifested in news coverage. In their research the subjectivity of journalists and media outlets are not discussed like with the above mentioned Holladay, but news media are rather seen as part of a national program for crisis management.

The research of this thesis aims to understand what type of crisis

communication strategies have been mediated in public service media in two countries who on the outside appear to have vastly different stances on the

pandemic. The distinct positioning of this study compared to previous research will thus be that the crisis communication reporting from media is regarded as a separate entity, rather than being a part of a larger encompassing program for crisis

communication on a state level. Distinguishing any discrepancies from the mediated reporting vis à vis the state’s applied pandemic approach will also accentuate the journalistic independency in the source material.

3. Analytical framework

In this part, the paper’s theoretical and analytical framework is discussed. In order to find an answer to an established research question, and also to contribute to the development of knowledge in the field, one needs to relate findings to existing theories and research within a related research area (Halperin & Heath, 2012:134). The following chapter will thus begin with a general review of the theoretical ideas of situational crisis communication theory, hereafter referred to as “SCCT”, which

14

forms the base for this paper’s theoretical framework. Thereafter follows a section which describes and defines the aspect of narrative analysis and how it relates to sensemaking theory. The chapter ultimately concludes with a section on the concept of media mediation.

3.1.

Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT)

W. Timothy Coombs, the founder of SCCT, notes in his The Handbook of Crisis

Communication (2010:24) how crisis communication research is a scattered field in

terms of how it belongs to a variety of disciplines, posing a challenge for anyone attempting to grasp the most updated and relevant approaches to use it. One of the principal theories within crisis communication is SCCT. True to its above-mentioned flexible field, it has been continuously tested and developed in academic research and is still in evolving as a theory (Coombs, 2010:41). The primary use of SCCT in this study will be its valuable defining aspects regarding crisis communication response strategies and how these are applied through narrative in news media.

The concept for SCCT is a theory that is audience oriented, used for

understanding psychological attitudes and attributes that participants/audiences have towards a leading organization during a crisis (Kyrcychok, 2017:55). Coombs himself summarizes SCCT as a “theory-based system for matching crisis response strategies to the crisis situation to best preserve the organizational reputation” (Coombs, 2004:266). This makes the core of SCCT focused on crisis responsibility within such leading organizations, continuing to further queries on reputation management (Coombs, 2010:38). It would however be wrong to assume that SCCT is a theory limited primarily to reputation management Coombs informs, with other crisis outcomes including factors affect as well as behavioral intentions (2010:39).

Within SCCT, there are two evaluation stages of assessing a crisis. Firstly, a classification of crisis, determining what type of crisis cluster is at hand: victim, accidental or intentional. This is followed by another classification of what precise type of threat this crisis entails (Coombs, 2004:269). Figure 1 below clarifies the

15

different existing definitions for these crisis cluster types. A pandemic like the

coronavirus disease first-handedly falls under being an act of nature where all parties involved are victims.

Following the mediated reporting on the virus spread and actions taken to contain it, government leaders and other stakeholders are also subjects to scrutiny regarding if they are handling the crisis properly. The prominent crisis type relevant for an analysis of the coronavirus crisis therefore would fall primarily within the

Victim crisis cluster, containing Natural disaster or also the Intentional crisis cluster,

containing Human error accidents.

Figure 1. Crisis Types Definitions and Cues

Source: Table 1 in Coombs, W T. (2004:270) Concerning how SCCT is assembled, Figure 2 below shows a map of the different

theoretical variables of SCCT. The figure illustrates how variables such as previous crisis history, reputation and response strategies are determining factors to the crisis responsibility of stakeholders.

16

Figure 2. The Model of Theoretical Variables of SCCT

Source: Figure 1.1 in Kyrcychok (2017:56)

As this paper is not in itself a study on audiences or reputational damage in times of crisis, the application of SCCT will in this case instead lie on its useful categorizing features regarding crisis response communication strategies. By knowing what crisis communication strategies exist and what defining features they have, we will be able to discern if any of them are predominant in the narratives of Danish and Swedish news media that reports on the coronavirus. Within Figure 2, this falls within the variable of “response strategies to crisis situations”. The previously mentioned crisis clusters determine the subsequent crisis response strategies that are to be taken in the matter. According to Coombs (2010:40), there are three primary such response

strategies: deny, diminish and rebuild. With a deny-strategy, the understandable aim is for the organization to convey that they are not to blame for the crisis. World leaders such as the earlier mentioned president Trump and president Bolsonaro fit within this strategy, with their administration at times denying that any pandemic risks existed. The diminish strategy is useful for minimizing the responsibility of the organization/stakeholder, arguing their minor involvement to the crisis. Within the Swedish context, this could for example be applied in narratives where Swedish authorities downplay the negative impact that the Swedish coronavirus strategy has

17

had on the death toll numbers. Ultimately, the rebuilding option focuses on taking responsibility, apologizing and offering appropriate compensation. Kyrchychok’s (2017:55) builds on this work by Coombs and further presents ten main types of such response strategies within SCCT. In short, these include: denial, responsibility

shifting, prosecutor attack, excuse, argumentation, flattery, care, compassion, anxiety and apology. These are further exemplified in this paper’s section 4.1.2 on data interpretation. Figure 3 below shows how the crisis types subsequently determine the proposed crisis response strategies.

Figure 3: Crisis Response Strategies

Source: Table 1 from Zamani et al. (2015)

In sum, these crisis response strategies are helpful for categorizing different crisis and taking the appropriate method to respond to them. They offer a guideline on what steps to take for resolving a problem. For the purpose of this paper, they most significantly offer a coding method on how to understand what stakeholders are shown doing through media in their response to the coronavirus disease spread.

18

3.2.

Introduction to Narrative and Sensemaking

The use of narrative is an established part of research in a variety of academic fields, ranging from communication to literature, political science and many other (Somers 1997:4). Looking past its methodological aspects, studying narratives may show “the explicit and implicit devices used to convey different events and the ways emotional responses are generated”. (Hodkinson, 2017:66). According to Berger (1997:4),

narrative is a powerful tool for spreading ideas and knowledge and it helps make the world both understandable and graspable. Such a description can easily be applied to the purpose of news media, which in itself aims to distribute the same type of concepts to the masses.

Berger further describes how narrative is the foremost way for us humans to sort and organize our experiences into being meaningful and educational parts of our lives (1997:10). Narratives can mediate sense by assigning meaning to politically important occurrences, intentions or actions. Narratives can furthermore be framed both positively and negatively; a group can for example be referred to either

terrorists or freedom fighters, depending on the narrator’s interests, beliefs and relations. To narrate stories is not merely a simple representation of an already existing reality, but rather a production of a specific way of interpreting the world, where some interests are positioned above others (Faizullaev & Cornut, 2017: 578). Narratives are therefore selective per definition, and they always compete over other narratives that may discern or emphasize other elements of reality. Dominant

narratives marginalize other narratives, while new narratives may grow and become dominant (2017:579). To find out how Denmark and Sweden are reporting on the coronavirus we need to approach it with this theoretical viewpoint regarding what distinct type of reality is being presented to the audiences and how it is framed.

Analyzing narrative is closely connected to the attributes of the previously mentioned sensemaking theory, which the foremost reason for why it is chosen for this thesis theoretical and methodological framework. Together, they both will help bring out the underlying meaning of content found in Danish and Swedish news media

19

concerning the coronavirus. Sensemaking is indeed a collaborative and social process (Stranberg & Vigsø, 2015:95), where true meaning and impact of a narrative appears only when stated narratives are analysed in relation to one another. By doing so, any confusion of messages regarding the crisis can be mapped out to an comprehensive coherence. As researcher Deborah Ancona explains, “The importance of sensemaking is that it enables us to act when the world as we knew it seems to have shifted. It gives us something to hold onto to keep fear at distance” (2012:6). In terms of using sensemaking for a quantitative content analysis, Robert Gephart (1998:7) explains how quantification plays an important role when analyzing sensemaking in a crisis, where the quantitative measures can validate and socially construct a problem. How this will be conducted for this particular study will be discussed further in the

methodology and research findings section. Sensemaking is furthermore particularly appropriate for this study of media in times of the coronavirus as traditional research on sensemaking often coincides with research of unusual events and crisis (Weick, 1995).

3.3.

Media Mediation

As this thesis centers on news reporting, it is important to approach the data

understanding what mediation of news stories implies. “News can never constitute an unbiased mirror on the world” Hodkinson (2017:120) states, referring to the ever-present bias of journalism. The filtering of news goes through its own subjective selection and construction before culminating in a news article. Accordingly, any news we access are ultimately merely representations of our reality. With this insight, Hodkinson argues that whatever results in media representation bears within it a story of cultural practices, values and structures of the society that it exists within. Any such distinction is of course not limited to individual journalists either:

Researchers Liu and Liu (2020) showcase through their research on media exposure during COVID-19 that types of mediums regarding news sources (commercial vs. official for example) have organic perspectives, which in turn influence what type of

20

content they produce to the public. An amplification of any occurrence of exaggerated bias in news reporting is today also particularly present in the polarizing standpoint concerning what constitutes “fake news” (Keener, 2019).

Any standpoint or further discussion on fake news in data from this study is however irrelevant for the purpose of this thesis. What on the other hand is

significant is that any data from this study is understood as not reflecting ultimate reality but rather a mediatized version, coming from one particular media source.

4.

Methodology

The following chapter aims to present and argue for the choice of methods and operationalization of this study. The chapter starts with a presentation and

discussion of the chosen research design, with the subsequent section containing a shorter presentation and discussion of content analysis with both quantitative and qualitative methods. Next, there is a presentation of narrative analysis. Afterwards there is a presentation of this study’s material and sampling strategies, followed by a presentation on the operationalization concerning data collection and interpretation of data. The chapter ends with a discussion around this research’s reliability, validity and ethical considerations.

4.1.

Case study

The paper’s methodological purpose is to investigate and analyze the variations of crisis communication between two countries during a particular time in history. The choice of research design therefore qualifies as a comparative case study, which aims to create a better and deeper understanding of how crisis communication works in practice. Within case studies lies the characteristic factor that they invite to deepened understandings of particular occurrences and experiences regarding a specific case rather than an explanation on a general level (Descombe, 2009:61-62). The method of case studies has indeed often been met by this reproach that it is not scientifically generalizable. Flyvbjerg (2006:226) has countered this criticism by commenting how

21

generalizability itself is overrated as a factor for scientific progress. That research can not be generalized does not mean that it is incapable of being part of a collective process of gathering knowledge in a certain research field or a certain community. Setting the central framework of this case study to the coronavirus is a choice coming from both its timely relevance and for the unprecedented impact that it has had on the global community. The research findings may come to concern this case alone rather than a wider scope of crisis communication in general, but due to the magnitude of the issue they will still be of considerable value to the (crisis

communication) research community. As Yin (2007:28) has also previously stated, case studies still do possess the ability to offer an analytical type of generalizing, which in this case can contribute to theory building around crisis communication. Case studies are furthermore efficient in attributing insight and contextual

explanation of actions (King et al, 1994:44). Because of the coronavirus crisis being new, with not much possibility of large scale overview and hindsight perspective, the case study benefits of insight and deepened understanding is therefore a welcomed attribute. SCCT is in this study used as both a theoretical as well as a methodological framework, which generates a deductive research design. A deductive research design “works with prior formulated, theoretical derived aspects of analysis, bringing them in connection with the text” (Mayring, 2000:4). This implies that this case study will be adapting theoretically established perspectives within SCCT as guidance for the analysis of the material, and derive from questions that come from previous studies on crisis communication. The purpose of the study is thus in one way descriptive, with an intention to systematically analyze any difference between Danish and Swedish media representation of leadership and its mediated crisis strategies during the coronavirus outbreak. This comparative analysis will then make way for the intention of deeper understanding regarding how the coronavirus has been mediated in our society, what patterns emerged on what themes were given most space, and ultimately, if the research displayed any discrepancy from what was expected. The research design of this single case study further makes it possible to

22

conduct research even with limited data and occurrences that are in some way novel and unprecedented.

4.2. Content Analysis

Within a deductive logic there lies the research strength of explanation and

prediction. The paradigm that follows the deductive logic is Neo-positivism, which also implies that a researcher in advance defines what it is that will be studied. In this particular case, the neo-positivist paradigm implies that Danish news media follows a narrative with less focus on strategies such as “care” and “flattery”, and more on those that are connected to “anxiety” and “blame”. This is based on the

aforementioned notion of how negatively loaded news stories will lead the public into further panic concerning a crisis (Kilgo et al, 2019:815), thus possibly easing the prevalence of stricter governmental restrictions. Discussion around this chosen paradigm is further presented in the paper’s section 5.5.

The choice of research method for a content analysis is always dependent on what type of question one wishes to answer with the research. Some questions can only be answered with quantitative methods. This regards in particular studies where quantifying the occurrence of something is central. As the aim of this study is to identify whether there exist any differences in how Denmark and Sweden’s news have reported on the corona crisis, a measurable method such as quantitative content analysis would seem preferable. In brief, content analysis is: “to identify and count the occurrence of specified characteristics or dimensions of texts, and through this, to be able to say something about the messages, images, representations…” (Hansen et al, 1998: 55). Riffet et al. (2013) have in their chapter, “Defining content analysis as a social science tool”, listed how the strengths of such a method are many, and

particularly regarding the research focus on the source’s own language use. This method’s furthermore has a central strength in its ability to with ease analyze large volumes of data in a systematic fashion (Stemler 2001:1). The research is thus

23

conducted in a way that eases material gathering and coding with focus on measuring facts without attaching them with particular subjective contexts.

Comparatively, a qualitative research method stems from the belief that reality is to be interpreted in different ways, with no objective or definite truth. With a qualitative content analysis, a study has the risk of becoming subjective, speculative and tendentious. This interpretive method nonetheless allows for a study of the social reality from within (Blaikie & Priest, 2019:100) and bringing out the essentials within a text while having in mind its surrounding context (Esaiasson et al, 2003:233). An important factor for a qualitative analysis is diligent reading and an

understanding of the above-mentioned surrounding context. The method prepares the researcher to actively read, ask questions about the content and identify with whatever chain of argument is there to guide the reader (2003:240). During an

interpretative (qualitative) study, the important task would be to understand what a content is saying in relation to the question that is being asked. In this paper, the interpretation of content would therefore mean seeing what types of narratives the different news media of Denmark and Sweden are presenting.

There is nonetheless an alternative to approaching material strictly

quantitatively or qualitatively, and that is to approach the research with multiple methods, a so called “mixed approach” (Collins, 2010:48). This content analysis is indeed primarily quantitative and the data will be measured deductively, but there is also a qualitative analysis step to how the data will be interpreted and coded from the start. Here much focus will lie on the qualitative narrative analysis, which will be presented in the following section. In this way, the content analysis will be coming from a mixed approach.

4.3.

Narrative analysis

As a complement to the content analysis, the material will also be analysed with a focus on narrative. Both methods fall under the scope of textual analysis techniques, where the research aim is to analyze a text. The scope of narrative studies is an

24

interdisciplinary field that is characterized by some confusion as well as

contradiction. It is not to be considered a particular discipline but rather a specific problem area within a wider research, containing various different perspectives and starting points (Johansson, 2005:20).

The core of the narrative analysis is its interpretive characteristic (Johansson, 2005:27). It is therefore possible to study different practices of leadership in crisis information, with the help of the narrative analysis. According to Vladimir Propp (in Berger, 1997:23), the most important aspect when studying narrative is to deconstruct it, in order to review the underlying content structure. This is referred to as the

morphological study of narrative, which implies that one studies the different parts of content and how they are connected to each other. There are generally three types of texts: argumentative (rhetorical, trying to convince of something), describing (attempt to reproduce and explain particular facts) and narrative (re-telling of events in time). Few texts are then purely argumentative, describing or narrative, but rather a combination of those (Jansson, 2002:19-20).

The narrative analysis focuses on how people conceptualize and interpret their social lives and organize their experiences in meaningful parts. A narrative analysis is a research method which is based on a constructivist view on knowledge, where knowledge is considered as something personal and subjective. The narrative

analysis should be used not only for describing different global occurrences, but also to identify how narrative is used in a strategic and rhetoric way, often on a

subconscious level, to conceptualize global events (Wibben, 2016:62). It furthermore makes it possible to distinguish particular nuances in a text, which could otherwise easily be overlooked using more purely technical methods of textual analysis (Robertson, 2005:226).

As previously mentioned, study of narrative focuses on deconstructing content. It focuses on reviewing a sequence-based content which takes part during a certain time and contains a change (Berger, 1997:4). Todorov (in Hodkinson, 2017:66) as well as Miskimmon et al. (2013:181) explain how narrative contains an initial normality, or

25

status quo, which then encounters a problem which disrupts this normality, only to ultimately find a solution which will re-instate the primary order. A narrative further contains certain main components. In Hodkinson (2017:66), a list is presented of seven such standard character types within fictional stories, Berger (1997:4) has identified five main components more relevant to this paper’s analysis of news coverage: (1) characters/actors, (2) a plot, (3) an environment/context, (4) a conflict/occurrence and ultimately (5), a solution.

Bamberg (2004:359) describes how readers become subjected to a particular type of narrative, called “metanarratives”, which is an unavoidable occurrence. Also referred to as a “master narrative”, it can be translated as a culturally accepted framework for how stories should be understood and accepted by audiences, which tends to normalize and make certain events appear natural. The master narratives are therefore rather limiting in that they reduce what actions are possible to take within the frame of the dominant story. As this paper will be comparing material from two sources with possible different cultural background, the focus will lie on searching for the master narratives in the chosen articles. How the narrative analysis will be used particularly for this study will be further presented in section 4.4.3.

4.4.

Research Process

The methodological aim is to do a comparative content analysis of Swedish and Danish online news stories regarding their reporting on the coronavirus.

4.4.1.Material

In order to identify and analyze any difference in news reporting coming from Denmark and Sweden regarding the coronavirus, the first question that arose was what news sources to use. As previously mentioned from earlier studies on crisis communication, news media can differ considerably in their reporting depending on what type of audience they are targeting and in what forum (Rodin, 2018; Ungar, 1998 etc.). The news media chosen for the comparative analysis therefore needed to

26

be as similar in structure as possible: one could for example not be a private news entity while the other one was mainly publishing on social media or being state-governed. As the theories of crisis communication focus in large part on how governments and figures of responsibility act in times of crisis, it was therefore deduced that the most appropriate selection of material would fall on national public news broadcasters that receive state funding. It has also been established that public service media is more strongly associated with neutrality and seriousness of

information (Liu & Liu, 2010:11). Consequently, the Danish DR and the Swedish SVT Nyheter, who are both established official news sources in their respective countries (Statens Medieråd, 2018; Wrede, 2018), would best fit such a most-similar-design.

4.4.2.Data-collection

The material gathered from the two news sources more precisely came from their online news platforms, www.dr.dk and www.svt.se, as online news have been established the most accessible and frequented in times of crisis (Lee, 2005). News items collected from the DR website came from the search-string “corona” and “covid”. News items from SVT, which does not have a search-function, came from the link https://www.svt.se/nyheter/utrikes/25393539where all of the SVT published articles on the coronavirus are listed chronologically. Both chosen sources classify as public service news media sources, which in itself represents news reporting that has a different agenda and tone than other type of news sources that come from the private sector. Research has shown that there is a distinct difference in content of commercial media compared to that of public service media, even when they report on the same news topic (Liu & Liu, 2020:11). This naturally leads to the fact that the use of market-oriented commercial sources in this study could have resulted in very different findings concerning narrative. A closer discussion concerning this is further presented in this thesis’s limitations section.

Due to the time-sensitive nature of this subject where every day may mean new discoveries and attitudes toward the virus spread, a limitation in time had to be set.

27

A limitation in time and in number of articles was also necessary due to the restricted time frame of the study itself. As the two countries’ alteration in how to approach the coronavirus became most visible in mid-March, 2020, after Denmark closed its

borders and schools (Olsen, 2020), this research would have the most effective analysis if it studies the news reporting published shortly after this breaking point. News articles were therefore selected and analysed from in between the dates of March 25 and April 1s, 2020. It is important to stress that whatever findings result

from this data is limited to what articles reported during this particular time frame. The findings are thus not representative of either countries’ general news reporting during the entire spring season of 2020.

The final material from the news sites consists of 119 articles from DR and 126 articles from SVT, totaling in 245 articles. Using a larger number of articles from a wider range of dates would undoubtedly deepen this study’s research finding scope, with a larger number of possible conclusions. This limited material can nonetheless offer a stringent and focused analysis, which in itself will strengthen the study’s internal validity and make way for a deeper analysis than perhaps a larger and more spread-out scope of material would have been able to do.

4.4.3.Interpretation of Data

The Swedish SVT Nyheter and the Danish DR online mediums will have their coronavirus content coded for a quantitative content analysis as well as a narrative analysis.

For the primary quantitative part, the chosen articles will firstly be identified and then categorized according to the main crisis response theme that it adheres.

The second part of the interpretation of data concerns the narrative analysis, which will be undertaken on any articles directly belonging to the most dominant and occurring SCCT narratives from the data findings. SCCT narratives are in this case stemming from the various SCCT crisis response strategies previously

28

into tools for analysis is based on their flexible nature that, unlike other crisis

communication strategies found in for example Image Repair Theory (Benoit, 1997), is not centered on merely reducing negative attitudes among audiences. SCCT rather consists of strategies that aid for a codified understanding on various responses to crises, and is therefore well applicable for a study on media representation. Each article belonging to a dominant SCCT narrative will also be reviewed regarding any mentions of leadership action, such as mentioning of the government, governmental leaders or the state epidemiologists Anders Tegnell and Søren Brostrøm for a further analysis on leadership. All the selected articles will then be part of the next step of deeper narrative analysis.

There exist numerous ways of undertaking a narrative analysis (Johansson, 2005:288). This paper’s analysis will be organized from a holistic perspective, where focus lies on content and approaching the story as a hole. Focus will also lie on part-content, which means that one defines some categories and highlight certain extracts from the text which are then classified and put into groups (Johansson, 2005:289). These identified groups are what this study thus defines as “narratives”. Studies in terms of narrative analysis have this advantage that it is possible to focus on content as well as form, which in comparison to traditional content analysis can contribute to a deeper understanding of the text’s meaning.

In order to answer the research question and distinguish how crisis

communication strategies are portrayed in the chosen articles, a coding model has been assembled (see table 1). This will in a concrete way help make the research approach and methodology transparent. This study intends to use narrative analysis to examine how the content of the articles on the coronavirus is built up, with a focus on certain stylistic or linguistic characteristics. Such an approach will uncover what master-narratives are present in the reporting. The narrative analysis is in this case a searching for tools that help explain the construction of social reality, and

understanding of how social structures are created, projected and reproduced. The articles will be analysed according to categories mentioned below, with an aim of

29

identifying the text’s themes or key words, and thus identifying possible combined narratives.

As has been mentioned earlier, in the use of content and narrative analysis it is important to avoid an analytic process which is subjective. This requires a structured approach and a thorough outline of a coding scheme. The coding categories outlined in the coding model are a combination of the Johansson universal analysis model (2015:286), primarily developed for analysis of stories, together with coding content by Coombs (2010), Kyrcychok (2017) and Zamani et al. (2015) based on situational crisis communication theory.

Table 1. Narrative Analysis Model

Plot What is the dominant set of stories told?

How is the narrative built up?

Actor Who is the main actor of the story? Who

else is mentioned?

Conflict/Solution Who does what and what are the

consequences of this? Is the threat of the coronavirus presented? Is any plan in handling the coronavirus presented?

Theme Why is this story told? Are there any

underlying themes? What is the master narrative in the story?

The material has been processed in accordance with Lieblich et al.’s (1998:62-63) proposal of a narrative holistic approach with a focus on content. The articles have first been read numerous times, with an open mind. On further reading, an active and systematic interpretation has been carried out with the questions presented in the analysis model, which in turn has made it available to classify and code the material. For the next step, initial reflections on a generalizing level have been formulated about the narrative to see where it fits within the SCCT theory on crisis communication strategies. The initial ten strategies mentioned by Kyrcychok (2017)

30

were compressed in to eight (where care and compassion for example were regarded as being too similar to distinguish and therefore combined). From these eight themes that were identified (see table 2), the articles have then be read through again, to identify how much space the overall theme is present in the text (Johansson, 2005:291). There parts of the texts have been chosen and underlined, in order to be presented as results under the findings part.

Table 2. Coding of SCCT Narratives

Narrative Coding Example

Denial Stating that there is no crisis

NO EXAMPLE Prosecutor

Attack/Responsabilty Shifting

Blame of someone else Attempt to shift

responsibility

”Sex medarbetare på äldreboende stängs av”

Excuse Attempt of minimizing the crisis responsibility, admitting control but saying there is no harm intended

NO EXAMPLE

Argumentation Attempt to rhetorically minimize damages caused by the crisis

” Kan den vestlige del af Danmark slippe lettere for coronavirus end Sjaelland og Kobenhavn?” (DR)

Flattery Praise for concerned parties and/or reminder of previous achievement of stakeholders

”Professor om dansk corona-krise: Det bliver bedre dag for dag" (DR)

”Sydafrika drar igång masstest för coronavirus” (SVT)

Care/Compassion Victims of the crisis are being cared for,

compensated

Expressed condolences for victims of crisis

”App hjälper frivilliga hjälpa isolerade”(SVT)

Anxiety Indicated concern about the crisis

“Första halländska dödsfallet utanför riskgrupperna” (SVT) ”Corona har slået den politiske tillid mellem EU-landene ihjel” (DR) Apology Stakeholders take

responsibility for the crisis and apologize for the situation

31

Ultimately, a simplified coding of the total of 245 articles was conducted where the above-mentioned narratives were interpreted as either reporting a reassuring and positive story to the public, or one that was negative or alarming in any way. In this case, narratives such as prosecutor attack, anxiety, excuse and argumentation would fall in to the “negative” coding while care and flattery would result in a “positive” category.

4.5.

Reliability,Validity and Ethical Considerations

When conducting content analysis research it is important to consider reliability, the trustworthiness of the study’s measurements and validity, whether the study is measuring what it is intending to measure. These factors, together with ethical

considerations need to be made throughout the research process in order to maintain the quality of the research findings (Bryman, 2008). Questions regarding particularly reliability and validity stem from the qualitative part of the methodology, which requires the inevitably subjective matter if interpretation and it therefore becomes vital to make visible any subjectivity towards what is being researched. Regarding any content analysis containing interpretation, the processes of analysis and

interpretation are never fully completed but continuously ongoing, open and connected to unpredictability (Johansson, 2005:316). One way of strengthening any research’s reliability and validity would be to make one’s primary data available, as well as offering information that could describe how interpretations have been made (Johansson, 2005:316).

Concerning ethical considerations, this research will be centered on a content analysis of published online news and public institutions. Such content is open and the images that they post are therefore available for the general public. There will therefore be no need for me to request any permission to use their material. As this study will not produce or use any personal pictures, there will also be no subsequent consent issues.

32

As Collins points out, “it is recognized that research is contextual and that the specific dilemmas that arise are unique to the context in which your individual project is conducted” (2019:83). In this particular context, the ethical question that arises is perhaps whether or the researcher writing the thesis would be in some way biased towards interpreting the data. Being biased refers here mainly to not being objective enough and unknowingly adapt a method where the findings are cherry-picked. Such a possible outcome could come from the fact that one of the countries that is analyzed is the researcher’s own home country (Sweden). Choosing a content analysis where content is coded however diminishes the risk of that. This thesis however also has a considerable qualitative aspect as well, since the coding of narratives still comes from a deeper qualitative analysis. As such, the interpretation conducted by the researcher may still turn out subjective to some extent. In this thesis however there has been no intentional conduct of that sort and the aim has

consistently been to present non-biased findings.

5.

Analysis and Findings

Through an analysis of the articles by the coding scheme presented earlier (see table 1) and through stringent reading concerned with what actors are presented in the articles and who is given most space, what conflicts exist and how these are

suggested to be resolved, what parts of the plot is presented and also what points the articles appear to make, eight themes from SCCT were sought to be identified (see table 2).

Besides the narratives that are present with each article (through looking at their content and structure), it is possible to identify narrative frameworks or master narratives. These are described by Abbot (2002:43) as themes, or narrative-skeletons. Out of 245 analysed articles, 119 were Danish and 126 were Swedish. From these, the most dominant narratives with the highest number of articles included “flattery”, “anxiety” and “blame” (prosecutor attack/responsibility shifting) and “care”. The other remaining narratives either did not exist within the analysed data, or only had

33

one or two examples. It is indeed a “finding” in itself that some narratives did not exist in the collected data from Denmark and Sweden, and this will be briefly

discussed further in this paper’s section on limitations and future research. A further deepened analysis will thus only focus on the 179 articles coded as belonging to either one or several of these four leading narratives (see table 3).

Table 3. SCCT Narratives: Findings

How much tangible total space of the analysed articles that belonged to the four dominant master narratives is exemplified in percent through table 4 and table 5 on the next page.

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 Anxiety DR Anxiety SVT Flattery DR Flattery SVT Blame DR Blame SVT Care DR Care SVT 48 57 11 11 14 15 8 15