Postprint

This is the accepted version of a paper published in Journal of European Real Estate

Research. This paper has been peer-reviewed but does not include the final publisher proof-corrections or journal pagination.

Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Palm, P., Andersson, M. (2020)

Anchor effects in appraisals: do information and theoretical knowledge matter? Journal of European Real Estate Research

https://doi.org/10.1108/JERER-03-2020-0012

Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper.

Permanent link to this version:

Journal of European Real Estate Research

Anchor effects in appraisals: Do information and theoretical knowledge matter?

Journal: Journal of European Real Estate Research Manuscript ID JERER-03-2020-0012.R6

Manuscript Type: Research Paper

Journal of European Real Estate Research

Anchor effects in appraisals:

Do information and theoretical knowledge matter?

1. Introduction

An understanding of the appraisal process on real estate markets are of outmost importance especially on markets where homeownership is financed by loans and mortgages. The large increase in house prices along with the high quantity of loans and mortgages being taken out make the function of real estate market a fundamental question for society and the financial sector’s stability. Further, real estate is an important cornerstone in individuals’ capital formation, as real estate owners become wealthier when real estate prices increase. If assets are capitalized, the total economy on a national level gain (i.e. capitalization in the economy) increases. On an individual level, the valuation of the property becomes important when it leads to increased opportunities to finance other purchases. As the real estate market and credit market have become more interdependent on both company and industry levels, the appraisal of real estate becomes important, as it leads to increased opportunities to finance growth and investment in the core business. Changes in the real estate market would therefore bear consequences for society at large, as the real estate market has emerged as a fundamental market linking individuals, households, credit market, government, and institutions. Economic literature takes its point of departure in the rational economic human, stating that, based on information and the knowledge of the best possible economic theory, the best decisions will be made. For example, Fischhoff (1988) raises two questions: “1. Do people perform the way that the models claim they should? 2. If not, how can people be helped to improve their performance?” Fischhoff (1988, p. 156). Information and knowledge about economic theory and models are thereby a cornerstone for making rational decisions. However, research has found that we do not always make rational decisions (Hastie & Dawes, 2001). We are biased and make heuristics which “reduce the complex tasks of assessing probabilities and predicting values to simpler judgmental operations” (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974, p. 1124). One such heuristic or bias is anchoring, which in several studies has been demonstrated to be robust (Furnham & Boo, 2011).

Anchoring effects in appraisals is of great interest because the real estate market and its appraisals influence society on several levels and provides a critical part of the real estate market (Salzman & Zwinkels, 2017). In all appraisals, as Amidu (2011) demonstrates, it is the judgement of the individual appraiser that sets the level of quality. The Appraisal Institute 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Journal of European Real Estate Research

(2001) state that the quality of a valuation report depends on using good and sound judgement in the application of basic valuation theory. In education and student training, with focus on the systematic process for decision making regarding how to appraise a property. In this process, it is important to ask whether the students are prepared to critically analyse information in order to make a sound appraisal.Real estate appraisal uses available data to make an assessment of an object and its market value (see e.g. Appraisal Institute, 2013; or Royal Institution of Chartered Surveying, 2017). It is generally considered as a process where the goals are to appraise a value rather than calculate a value. As Appraisal Institute (2013) states,

The final value opinion does not simply represent the average of the different value indications derived. No mechanical formula is used to select one indication over the others, rather, final reconciliation relies on the proper application of appraisal techniques and the appraiser’s judgement. (Appraisal Institute, 2013, p.39)

When it comes to teaching and examination of student´s appraising market values this is a hard question. At the same time as you try to introduce this point of view in the classes, the students at the same time need to learn how to apply the basic techniques calculating for example average price per square meter. This is not in any contradiction to the statement of the Appraisal Institute, since it is about how you use the numbers. This is much harder to teach as the students comes from different areas and it is not until you really know the area and its market that you truly can do a proper appraisal. This imply that in the classroom we can only teach the techniques, emphases the importance of market knowledge and to know your geographical area But, in the examination, it will be a focus on the formulas and to use them in a logical manner. When discussing judgement, the personal beliefs and psychology of the individual appraiser become important factors that might influence, for example, an appraisal task. The appraised value is individual and may depend on different parameters, such as tacit knowledge and personal preferences. Tversky and Kahneman (1974) argue that when a person is to appraise the value of something, she will adjust her first value based on additional information that she receives. Tversky and Kahneman (1974) argue that, although this initial value may or may not be relevant, she will incorporate it and be influenced by it when finally deciding a value for the object. Within real estate appraisal, Northcraft and Neale (1987) conducted a survey where they asked different people (both real estate agents and amateurs) to appraise the same property while changing the condition regarding asking price. Although the asking price should not 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Journal of European Real Estate Research

influence the appraisal of the market value, Northcraft and Neale (1987) conclude that, regardless of being a professional real estate agent or an amateur, a positive relation was found between the asking price and the appraised value. In later years, several other experiments have been conducted, and they indicate similar outcomes (e.g. Levy and Frethey-Bentham, 2010; Thomas et al., 2010; Diaz and Hansz, 2010; Beggs and Graddy, 2009; Kaustia et al., 2008; and Hansz, 2004). Furthermore, Chang et al. (2016) conducted a statistical test with over 50 observed transactions in Taiwan. They concluded that anchoring influences decision making when investing in real estate.The phenomenon of heuristics and anchoring is unambiguous and the question on how to address it is discussed previous literature. Fichhoff (1988) formulates the problem as how to assist the appraiser to perform appraisals according to a model without anchoring effects. Previous studies have concluded that an anchor effect is more or less persistent in appraisals for both professional and non-professionals therefore it is important to raise awareness of this phenomenon. By this the professional appraiser becomes conscious and can take measures to develop robust decision making. At the same time there is not a clear definition on what constitutes an anchor. Is it the actual sales price that is confirmed or is it the sole opinion of the real estate owner regarding the value of the property? There might be no problem if the actual sales price is defined as the anchor, as the sales price should be considered as the most relevant observation. However, in case the anchor is defined as the owner´s preferred value then appraiser needs to be more careful. This study defines the anchor as owner´s preferred value. Therefore, an awareness of the phenomenon and how appraisers can learn to make decisions in relation to the models are motivated.

The aim of this study is to evaluate the impact of theoretical knowledge related to financial behaviour and anchor effects in particular. The study design is based on an experiment that was divided into two parts – before and after the implementation of the new course curriculum for the undergraduate real estate course, introducing Behavioral Finance. The appraisers in both parts of the study are real estate students in their fourth semester (of a total of six semesters). In the original course, theoretical knowledge related to financial behaviour and anchor effects were not a part of the course content. However, after the development of the course curriculum and it being made a new part of the course, the students have the opportunity to gain theoretical knowledge of financial behaviour and anchor effects. This gives us the opportunity to test how the theoretical knowledge in behavioural finance and the anchor effect in particular mitigate anchor effects in a situation where a property is to be appraised. In both parts, before and after 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Journal of European Real Estate Research

the introduction of anchor effects in the course, the participants were presented with different information regarding the preferred property value by the real estate owner.2. Theoretical framework

Over the years, several appraisal experiments have been carried out (see for example Black et al. 2003; Crosby, 2000; and Diaz, 1999, for an overview). These studies mainly take their starting point in the field of behavioural economics. The field of behavioural economics adds psychological factors to the economic analysis in order to make better predictions and suggest better policies. It is rooted in Newell and Simon’s (1972) studies of human information processing, which demonstrates that individuals cannot make perfectly rational decisions. The basic conclusion is that individuals, or groups of individuals, use cognate shortcuts to simplify their decision making (Northcraft & Neale 1987).

Camerer and Loewenstein (2011) state that behavioural economics is closely related to the neoclassical approach in economics, as its theoretical framework can be applied to almost any form of economic behaviour. Furthermore, Sent (2004) highlights the fact that Adam Smith in his book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (published in 1759), had already used psychological principles of human behaviour in relation to his economic observations. However, in recent years, the field of behavioural economics has gained broad recognition, with scholars like George Akerlof, Michael Spence and Joseph Stiglitz being awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 2001 for their studies of asymmetric information. Further attention was brought to the field when the Nobel Prize was shared in 2002 by David Kahneman for his integrational work of psychological and economic research regarding decision making under uncertainty and when Vernon Smith established laboratory experiments as a tool in empirical economic analysis. Further, in 2017, Richard Thaler was awarded the Nobel Prize for his contributions that built a bridge between the economic and psychological analyses of decision making. However, the field is not to be considered as a unified discipline (Tomer, 2007). Instead, Tomer (2007) argues that it must be seen as a toolbox or a perspective on how research in economic behaviour is regarded. There are several branches in behavioural economics, with decision research, heuristics and biases, and anomalies as the three most common (Angner & Loewenstein, 2007). Linked to how individuals take decisions is behavioural ethics by adding understandings and descriptions of how decisions are actually made by people and why good people sometimes do bad things despite exposure to normative ethics training (Bazerman and Gino, 2012). Research in decision making takes its point of departure in economic man and 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Journal of European Real Estate Research

why individuals make decisions that are not rational from this point of view (Hastie & Dawes, 2001). In line with this, Fischhoff (1988) raises two questions: “1. Do people perform the way that the models claim they should? 2. If not, how can people be helped to improve their performance?” Fischhoff (1988, p. 156). These two questions directly relate to the aim of this study – to determine how market values are appraised and how a more robust process can be developed and guidelines and/or routines can be implemented during the appraisal in order to enhance the robustness of the results of the estimated value of the appraised property.The research in heuristics and biases takes the point of departure in that people rely on heuristic principles to reduce complexity when assessing probability and predicting values. Tversky and Kahneman, (1974, p.1124) conclude that “in general, these heuristics are quite useful, but sometimes they lead to severe and systematic error”. The usefulness of a heuristic is that it provides fast answers, but it also violates logical principles leading to errors in some situations. One of the more classic examples in this area is found in Tversky and Kahneman’s (1974) study where people were asked to guess the number of African nations in the UN after spinning a wheel of fortune. This random number between 1–100 from the wheel of fortune strongly influenced the guess of the number of African nations in the UN. The conclusion was that they seemed to anchor their guess, which in turn led to biased guesses.

The research of anomalies stems from Thalers research focusing on forecasting. Thaler (1980) identifies how consumers are likely to divide from normative models. He continued to develop a new model for consumer behaviour by first identifying how people’s choices could be divided from rational choice theory, and from that, developed more empirically based models.

Real estate market analysis and appraisal both derive from the same mainstream economic theory. Klamer et al. (2017) now conclude that behavioural research is well developed and positioned within the field of real estate research. The main contribution of including behavioural economics within the field of real estate is to better understand appraisal judgement (Wyman et al., 2011). Previous research in the field is focused on two areas: 1) Valuation bias and client pressure within valuation (Diaz & Hansz, 2007; and Klamer et al., 2019), and 2) accuracy in forecasting (Papastamos et al., 2015). Klamer et al. (2017) categorize these valuation studies in intrapersonal respectively interpersonal judgement bias. In this context, intrapersonal bias refers to appraisers applying heuristic behaviours in their decision making, as the phenomena is predominantly related to the single individual´s cognitive information processing capacity (Klamer et al., 2017). Interpersonal bias refers to when client dependence causes, or may cause, suboptimal decision making by appraisers (Klamer et al., 2017). 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Journal of European Real Estate Research

Accuracy in forecasting is associated with hoarding behaviour and how the individual forecaster tends to follow the mainstream and apply heuristic behaviour in their forecasting (Papastamos et al., 2015).The most common valuation method appraising the market value is the comparable sales method (Persson, 2018; Shapiro et al., 2013). Applying the comparable sales method, the appraiser use sales conducted on the open market of real estate that are to be considered as comparable. However, all real estate is unique, there will always be a question regarding how similar and comparable the list of sales are. Furthermore, the method will always face the time-lag problem. This as the list of sales contains sales that has been made in a different time, one has to be careful with how long back in time sales are to be considered as comparable (Pagouritzi et al., 2003; Millington, 2013). All this together with a market, when it comes to homes that are also emotionally driven from both the sellers and potential buyers has implications on the appraisal (Salzman & Zwinkels, 2017). The accuracy of the appraised value has been in the light of discussion (see for example Pagourtzi et al., 2003; Babawale, 2013). Studies in relation to the accuracy of the appraised value all conclude that there are a relatively large margin of error in the appraised values. Babawale (2013) made an overview of existing studies, concluding an expected margin of +/-10percent for “normal” buildings.

3. Purpose and hypothesis development

The objective of the research is to investigate the anchor effect in the appraisals of residential properties based on a quantitative survey among Swedish students at an educational program for real estate brokerage. The specific question asked in this study is how the theoretical knowledge of financial behaviour and especially anchor effects can affect the appraised value in terms of how the anchor effect may occur.

Previous research has identified various factors that influence price perceptions, including factors that affect assessments of the perceived value of products to consumers, and relatedly, the reference prices consumers use to evaluate the attractiveness of given prices (e.g., Winer 1986). Although the determinants of reservation prices have been extensively studied, there has been much less research regarding the manner in which consumers decide on the lowest price they are willing to accept for a product (for exceptions, see, e.g., Carmon and Ariely 2000; Kahneman et al. 1990). The value appraised is individual and may depend on different parameters such as tacit knowledge and personal taste. Tversky and Kahneman’s (1974) seminal work on anchor effects reveal that an external number, referred to as “anchors”, 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Journal of European Real Estate Research

influence the estimated value of the given object. Within real estate valuation, Northcraft and Neale (1987) applied the same idea to real estate, conducting a study in which both students and real estate agents were to value the same house while changing the conditions regarding asking price for the house. Although the asking price should not affect the valuation of the market value, the study concluded that both real estate agents and students were positively affected by the asking price. This also relates to Bellman and Öhman’s (2016) research conducted on authorized property appraisers in Sweden. In their study, they conclude that authorized property appraisers to a large degree rely on information from the property owner. In terms of anchor effects or risks for anchor effects, the authorized property appraiser put themselves in a situation where their appraisal might be influenced and biased by the property owner. This is a situation that both Chang et al. (2016) and Amidu et al. (2019) conclude carries great risks, as the investor is biased.Attempts to lessen the effects of anchoring bias have been made. For example, several studies (see for example Fischhoff, 1982; or Sharp & Cutter, 1988) where feedback has been given during the process have turned out positive. Later studies (see for example Adame, 2016) test how training programs can help participants mitigate anchoring bias. Adame (2016) concludes that training does mitigate anchoring effects. George et al. (2000) introduced decision-support systems to assist the participants in the decision making, only to conclude that the anchoring effect remained robust within the context.

Previous studies introduce and define anchors in different ways, to a large extent, it can be divided into two types. The first type departs in the classic experiment of Tversky and Kahneman (1974), where the anchor does not have anything to do with the object that is to be appraised. In other words, a random numerical number is planted in the respondent’s mind. The second type is more common in the experiments of anchoring in real estate studies. In these previous studies the respondents are exposed with the price of the property. These studies define the anchor as the price of the property (see for example Northcraft and Neale, 1987). Using the price as an anchor can be difficult as the comparable sales method stipulate the use of market sales as point of departure for the appraisal. Therefore, the price used as an anchor should be included in the list of comparable sales. One could even argue that this price should be considered the most appropriate when estimating the value. Instead, the present study uses a statement from the owner regarding their wish of a certain value of the property to be apprised. In this way we use of the specific object and the owner´s perception of the expected value. The 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Journal of European Real Estate Research

present research does not introduce a price that should be included in the list of comparable sales.In relation to previous studies, the focus on anchor effects, and theoretical knowledge contribution to mitigating anchoring bias, the present study develops two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. Appraised values exposed with low anchor will differ significantly from those exposed with high anchor.

Information and educational background are concluded as important (see for example; Adame, 2016; Bellman et al., 2016; and Joselyn et al., 2011). However, Tang and Lin (2017) conclude that the anchor effect is also apparent among highly educated people when engaged in number estimating under time pressure. However, as Adame (2016) concludes, training does mitigate anchor effects. Moreover, introducing financial behaviour effects and especially anchoring effects in the course of real estate valuation could mitigate the anchoring effect, as it is not only knowledge in valuation but also knowledge regarding the decision process and risk for biases in the valuation process that is included in the teaching of the course. The information delivered to the students increases their awareness of anchor effects. In turn, this awareness should influence the students, and given an appraisal task, the anchor effect should be mitigated. It is from this that the second hypothesis derives:

Hypothesis 2. The introduction of behavioural economics and anchor effect should mitigate the anchor effect.

The present study serves two important purposes; firstly, to contribute to the research agenda analyzing anchor effects in appraisals of real estate, and secondly, to highlight the presence of anchor effects in conjunction with educational programs of real estate brokers to improve the overall skills involved in conducting real estate appraisals.

4. Design/methodology/approach

The present study features two experiments conducted during the examination of a course focusing on real estate valuation. The design of the experiment is to some extent similar to that of Northcraft and Neale (1987) and inspired by Seiler (2014) discussion regarding experiment studies conducted with students. The experiments took place during the written examination of the course. The examination setting is a classic sit-in exam with students sitting at individual desks with only paper and pen allowed. The exam consists of a set of multiple-choice questions 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Journal of European Real Estate Research

and one major question consisting of the experiment. The experiment question and instructions are provided together with information about the property. The information of the property consists of an extract fromthe Swedish mapping, cadastral and land registration authority. The standard format include address, geographical location, title deed, taxation, a quota measuring selling price/taxation value, size of building and land, year construction and price and date of the property when it was bought. The second set of information included was a list of historical comparable sales for a total number of 42 properties sold during the last year in the same municipality of the property to be apprised. The student is given the instructions that a client contacted him or her conduct an appraisal of a property. Within the instructions there is information that client expect to a certain value to be appraised. The information given in to experiment differ between two groups; a low anchor group and a high anchor group. The instructions were divided into three steps; first, sort the comparable sales list and motivate your sample, secondly, provide three key indicators to be used in the appraisal, and last conduct and produce your appraisal of the property. The fact that this was a part of a final written exam reduces the potential risk of heuristic processing to reduce cognitive effort, as concluded by Chen and Chaiken (1999). The students were provided with a generous amount of time to complete the exam. No student used the full time for the exam, even though during these exams the students are usually focused and set on accuracy. At the time of the first experiment, the theoretical base of financial behaviour had not been included in the students’ course; however, while conducting the second experiment, this theoretical perspective had been introduced in lectures and the course literature.In Experiment 1, a total of 115 students, who were all in their fourth semester in Real Estate Education during the spring semester June 2, 2015, within the course of Real Estate Valuation, participated in the experiment. The experiment was conducted during the final exam of the course and was designed to be representative of a real appraisal situation.

In Experiment 2, a total of 115 students, who were all in their fourth semester in Real Estate Education during the spring semester May 29, 2017, within the course of Real Estate Valuation, participated in the experiment. The experiment was also conducted during the final exam of the course and designed to be representative of a real appraisal situation.

In both experiments, the students were first asked to calculate key indicators, previous sales records, price per square meter, and a quota measuring selling price/taxation value.The students were also asked to calculate points of reference which are to be used for the estimated value. In 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Journal of European Real Estate Research

addition, they were informed that the property had recently been sold for a specific price – the anchor. The only difference between the two experiments were the participants’ theoretical knowledge of financial behaviour and anchor effects. The two experiment are using students from the same educational program and can be viewed as substitutes. The timing of the experiment does not involve any major event influencing the results.Experiment setting:

For both Experiments 1 and 2, the same fictional property was used – Property A.

Specifications for Property A: Built in 1925, 119 m2 and 50m2 basement. The property was

extended in 2004.

The list with sales for Property A consisted of 42 sales. All sales were completed within the past 24 months. For Property A, the range of sales were 1.6´´– 3.95´´ SEK and they were between 50–196 m2 and built between the years 1925–2000.

For both experiments, two different sets of data were produced: Set 1: Property A is given a high anchor (3.350´ SEK)

Set 2: Property A is given a low anchor (2.400´ SEK)

The two datasets were distributed to the students during their final exam. The task for the participants was to sort the data material using a sales comparison approach to indicate a market value for the property. The assignment constituted that they should first sort the historical sales and select the sales that they think are most comparable. They were then to calculate the average regarding price per square meter for the living area, the total property price, and the price divided with tax assessment value. Finally, from these averages and the property at hand reconciling and motivating, a market value for the property was to be given, and this, along with all the related material, was to be handed in after the exam.

Considering the list of 42 sales, all is not appropriate to consider as comparable. One property should be excluded as it was on leasehold and thereby only 41 sales remain. If also considering repeated sales and only include the latest of the two, we only have 39 sales left. Doing this gives an average price of 2.950´ SEK with the range of 2.000´ - 3.950´ SEK. The students should also consider the building year and the size of the house. Excluding all houses built after 1950 (no 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Journal of European Real Estate Research

houses were built before 1925) left 21 sales. Excluding the smallest and largest houses only allowing houses in the range of 99-139 m2 (+/- 20m2), 8 sales remained. The price range was2.500´ to 3.050´ SEK with an average of 2.700´, and an average price per sq. meter of 24.605 SEK. As the majority of the 8 sales (six of the eight) were smaller the price per sq. meter gives a value of 2.928´ SEK when applied on the valuation object. Furthermore, applying the average of price divided by tax assessment value gave a value of 3.025´ SEK. The expected value should then be somewhere between 2.700´ and 3.025´ SEK.

5. Result

The result is divided into three sections describing the experiments together with an exploratory statistical analysis with a concluding section to make clear the similarities and differences between the two experiments.

Experiment 1

In this experiment, the participating students did not have any prior theoretical knowledge regarding behavioural finance and anchor effects. The total number of participating students writing the exam was 115. The number of students who were successful to provide an appraisal using the comparable sales method was 85, giving a response rate of 74 percent.

The focus on their coursework was to conduct the more technical parts of the appraisal process (i.e. selecting the sample of previous sold houses in the dataset provided during the exam). The initial findings indicate a high difference between Group A (high anchor value) and Group B (low anchor value).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics, Experiment 1

Appraised value

Anchor Number Mean

Standard deviation Standard error of the mean Low 42 2704 198 30.56 High 42 2964 236 36.01 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Journal of European Real Estate Research

Table 1 indicates that there is a difference in the mean appraised value, with a larger mean value for the group of students provided with a high anchor. If we were to illustrate the result in a whisker diagram, the outcome would be as shown as in Figure 1.Figure 1. Whisker diagram, Experiment 1

From the whisker diagram in Figure 1, the difference in appraised values between the group with low anchor and the group with high anchor is rather obvious. In order to investigate the statistical significance of the difference, we performed an ANOVA to check for difference between the two groups’ mean value.

Table 2. ANOVA, Experiment 1

Source degrees of freedom Sum of Squares Mean Square F statistic p

Between groups 1 1 434 485 1 434 485 30.141 .000 Within groups 83 3 950 182 47 593 Total 84 5 384 667 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Journal of European Real Estate Research

From the ANOVA conducted for Experiment 1, it can be observed that the F-value is 30.141 and tested significant. The result indicates that there is a statistically significant difference between the two groups, and we thereby accept Hypothesis 1 and conclude that differences in appraised values are influenced by the anchor effect.Experiment 2

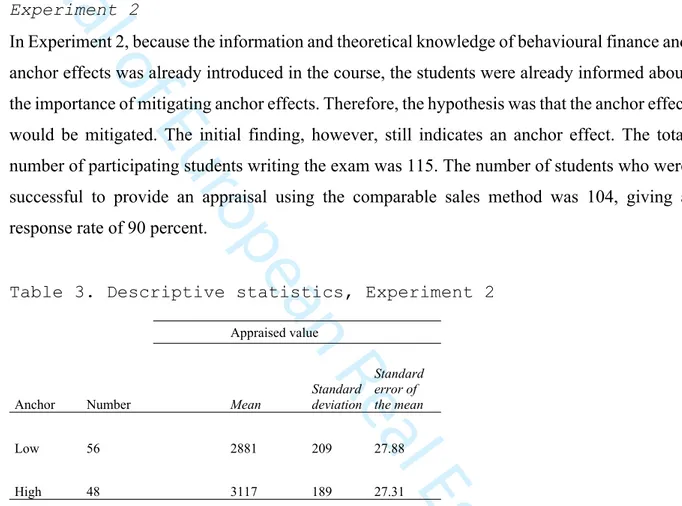

In Experiment 2, because the information and theoretical knowledge of behavioural finance and anchor effects was already introduced in the course, the students were already informed about the importance of mitigating anchor effects. Therefore, the hypothesis was that the anchor effect would be mitigated. The initial finding, however, still indicates an anchor effect. The total number of participating students writing the exam was 115. The number of students who were successful to provide an appraisal using the comparable sales method was 104, giving a response rate of 90 percent.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics, Experiment 2

Appraised value

Anchor Number Mean Standard deviation

Standard error of the mean

Low 56 2881 209 27.88

High 48 3117 189 27.31

Table 3 indicates that there is a difference in the mean appraised value. If we were to illustrate the result in a whisker diagram, the outcome would be as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Whisker diagram, Experiment 2

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Journal of European Real Estate Research

In addition, the whisker diagram indicates a clear difference between the group with a low anchor and the group with a high Anchor. An ANOVA was performed to check for significant difference between the two groups’ mean.

Table 4. ANOVA, Experiment 2

Source degrees of freedom Sum of Squares Mean Square F statistic p

Between groups 1 1 436 951 1 436 951 35.945 .000

Within groups 102 4 077 630 39 977

Total 103 5 514 581

From the ANOVA conducted for Experiment 2, we can see that the F-value is 35.945 and tested significant. The result indicates that there are differences between the two groups, and thus, Hypothesis 2 is rejected. The conclusion is that differences in appraised values still are influenced by the anchor effect, even with the introduction of behavioural finance and anchor effects in the course.

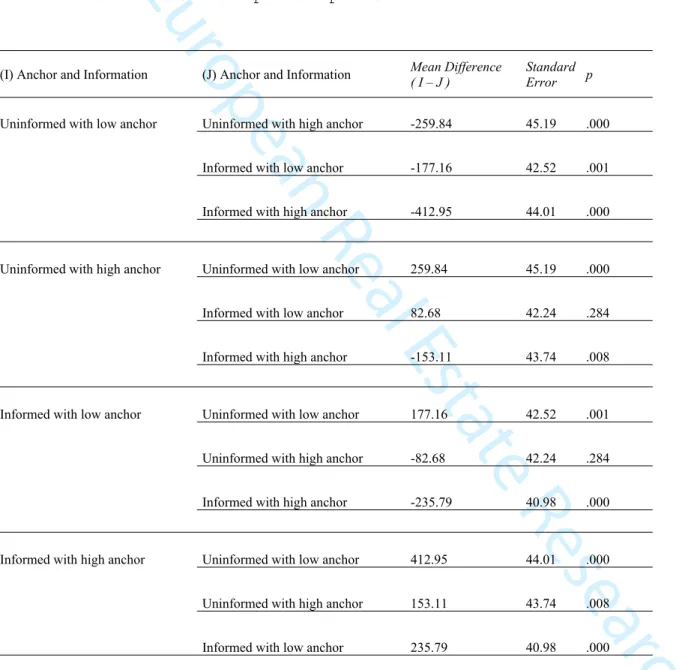

To test how introducing information regarding behavioural finance in the course curriculum of the anchor effect is tested in a between-group experiment was conducted. The groups were 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Journal of European Real Estate Research

uninformed students provided with low anchor, uninformed students provided with high anchor, informed students provided with low anchor, and informed students provided with high anchor.As seen in Table 5, the only comparison that is not tested significantly different from each other is between the groups ‘Uninformed students with high anchor’ and ‘Informed students with low anchor’. For the rest of the groups, we can most certainly conclude that there are differences between the appraised values provided by the students, as the test provided significant results. Table 5. Scheffe’s multiple comparison

(I) Anchor and Information (J) Anchor and Information Mean Difference ( I – J ) StandardError p

Uninformed with low anchor Uninformed with high anchor -259.84 45.19 .000

Informed with low anchor -177.16 42.52 .001

Informed with high anchor -412.95 44.01 .000

Uninformed with high anchor Uninformed with low anchor 259.84 45.19 .000

Informed with low anchor 82.68 42.24 .284

Informed with high anchor -153.11 43.74 .008

Informed with low anchor Uninformed with low anchor 177.16 42.52 .001

Uninformed with high anchor -82.68 42.24 .284

Informed with high anchor -235.79 40.98 .000

Informed with high anchor Uninformed with low anchor 412.95 44.01 .000

Uninformed with high anchor 153.11 43.74 .008

Informed with low anchor 235.79 40.98 .000

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Journal of European Real Estate Research

The result of the Scheffe’s multiple comparison analysis also adds to the rejection of Hypothesis 2 and leads to the conclusion that being informed and having theoretical knowledge about the risk for anchor effects in the appraisal process does not automatically reduce the anchor effect.6. Discussion and conclusion

Amidu (2011) concludes that it is the judgement of the individual appraiser that sets the level of quality for the appraisal of a property. Our two experiments were conducted on students with a risk of negative bias, as their experience of conducting appraisals is limited, but at the same time, given the situation in which the experiment was conducted, they would be cautious in order to perform their best, as the experiments are a part of their final exam. Furthermore, in line with Fischhoff (1988), could we help the students to actually perform as expected by educating and introducing anchor effects to them?

Although the question formulated for the students can be regarded as something unique for the institution, one can argue that it is transferable into the real-world setting, as the property owner will emphasise their thoughts regarding the value and/or what they originally bought the property for. Together with Bellman and Öhman (2016), conclusions that the appraiser in the thought pattern highly rely on and take into consideration information from the property owner does indicate that this is a question and result of great importance.

Within the context of the present research, that is, in an educational setting focusing on teaching methods used for real estate appraisals, the results have important implications on how we teach and highlight the presence of anchor effects. Hence, the anchor effect needs to be taken into account when developing the curriculum for courses in real estate appraisals.

The study indicates that students provided with a low anchor, on average appraise a lower value of the property than the students provided with a high anchor. One important factor to consider is the uncertainty in appraisal.

Babawake (2013) concludes that more or less all appraisals are suffering from an error margin due to the margin of uncertainty. Therefore, there should be an expectancy of an error margin around +/- 10%. This indicates that this study, should consider appraised values in the range of 2.600´to 3.300´ SEK being within this error margin. This implies that more or less all of the 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Journal of European Real Estate Research

respondents appraise a value that are acceptable. However, this is not the main objective of this study. The main objective is to analyse a systematically higher or lower appraised value depending on being provided with a high or low anchor. This study introduces the anchor as the value that the property owner state to be expected, thus not the price of the property. Owners view or expectations should not be taken in account in the comparable sales method. But, as Salzman and Zwinkels (2017) state this is commonly happening when conducting real world appraisal. However, this is when the appraiser is facing the owner and, to some extent, are dependent on the owner as customer.The students do take the owner´s expectation in consideration when appraising the market value of the property. We can see a clear anchoring effect and the tendency to lean towards the provided anchor regardless of being informed through theoretical knowledge or not. Given that we accept the null hypothesis, the study confirms the conclusions of Northcraft and Neale (1987). However, as we reject Hypothesis 2, concluding that being informed regarding anchor effects does not mitigate the anchor effect, we need to address anchor effects and how the effects are mitigated in reality in order to enable more sound and robust appraisals. The findings regarding the experiments with two groups of participants – informed participants in relation to those uninformed – has not be found in the previous literature and should be of interest for future research. Adame’s (2016) study also indicates related results; however, when Adame (2016) found that training mitigates anchor effects, our results did not show the same effect. One difference between these studies is that in the previous study it was the same respondents who were being trained, and the effect of the training is measured afterwards when the respondents have had time to critically reflect over their first assessed value. In our study, the respondents were not able to go back and change their appraised value. Instead, the result is more in line with the result of Tang and Lin (2017) and George et al. (2000), concluding a persistent anchor effect.

The categorization of valuation and appraisal processes of properties developed by Klamer et al. (2017) focuses on intrapersonal respectively interpersonal judgement bias. In the context of the conducted experiments, we can observe intrapersonal bias related to the participants’ cognitive information processing capacity even though the participants have been given training in order to increase the cognitive capacity to handle anchor effects. The outcome of the study indicates that the course in real estate appraisals do not give the students the right prerequisite knowledge to make sound appraisals. Our educational activities need to be 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Journal of European Real Estate Research

evaluated on the basis of these results and the educational activities may need to be reformed, just as the result of Experiment 1 resulted in the reformation of the original course curriculum and led to introducing behavioral finance and anchor effects in the teaching. This result has also led us to emphasize critical thinking to the students and in the classes. The test result also highlights the possibility that current literature and learning activities do not adequately emphasize and stimulate critical thinking. Therefore, we propose that other real estate education programs should also be aware of the potential lack of critical thinking among the students. This could be highlighted not only within academia but also for professionals concerned with valuer education and professional development.To conclude, the results of this study indicate that the appraisal of properties is dependent on the individual’s cognitive capacity to mitigate anchor effects. There are epistemological assumptions underlying our belief in the individual’s capacity to handle anchor effects that may provide biased appraisals. These assumptions need to be carefully tested and treated for example through training this in order to increase the accuracy of property appraisals.

References

Adame, B.J. (2016). Training in the mitigation of anchoring bias: A test of the consider-the-opposite strategy, Learning and Motivation, Vol. 53, pp. 36-48.

Amidu, A. (2011). Research in Valuation Decision Making Process: Educational Insights and Perspectives, Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 19-33.

Amidu, A.R., Boyd, D., and Gobet, F. (2019). A Study of the Interplay between Intuitin and Rationality in Valuation Decision Making, Journal of Property Research, Vol. 36, No. 4, pp. 387-418.

Appraisal Institute. (2013). The Appraisal of Real Estate, 14th Edition, Appraisal Institute,

Chicago, Illinois.

Bazerman, M., & Gino, F. (2012). Behavioral ethics: Toward a deeper understanding of moral judgment and dishonest, Working Paper 12–054. Harvard Business School.

Babawale, G. (2013). Valuation accuracy – the myth, expectation and reality!, African Journal

of Economic and Management Studies, Vol. 4, No. 3, pp. 387-406.

Beggs, A., and Graddy, K. (2009). Anchoring effects: Evidence from art auctions, American

Economics Review, Vol. 99, No. 3, pp. 1027-1039.

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Journal of European Real Estate Research

Bellman, L., Lind, H., and Ohman, P. (2016). How does Education form a High-Status University Affect Professional Property Appraisers´ Valuation Judgements?, Journal of realEstate Practice and Education, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 99-124.

Bellman, L., and Öhman, P. (2016). Autherised property appraisers´ perceptions of commercial property valuation, Journal of Property Investment and Finance, Vol. 34, Iss. 3, pp. 225-248. Black, R. T., Brown, G. M., Diaz, J., Gibler, K. M., & Grissom, T. V. (2003). Behavioral Research in Real Estate: A search for the Boundaries, Journal of Real Estate Practice and

Education, Vol. 6, Iss. 1, pp. 85-112.

Carmon, Z., and Ariely, D. (2000). Focusing on the Forgone: How Value can Appear so Different to Buyers an Sellers, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 27, Iss. 3, pp. 360-370. Chang, C-C., Chao, C-H., and Yeh, J-H. (2016). The role of buy-side anchoring bias: Evidence from the real estate market, Pacific-Basin finance Journal, Vol. 38, pp. 34-58.

Chen, S., and Chaiken, S. (1999). The heuristic-systematic model in its broader context, In Trope Y. (Ed.), Dual-process theories in social psychology, pp.73-96, New York, Guilford Press.

Camerer, C.F., and Loewenstein, G. (2011). Behavioural Economics: Past Present, Future, in

Advances in Behavioural Economics, Eds. C. Camerer, G. F. Loewenstein, & M. Rabin,

Princeton, Princeton University Press.

Crosby, N. (2000). Valuation accuracy, variation and bias in the context of standards and expectations, Journal of Property Investment & Finance, vol. 18, Iss. 2, pp. 130-161.

Diaz III, J., & Hansz, A. (2007). Understanding the behavioural paradigm in property research. Pacific Rim Property Research Journal, Vol. 13 No. 1, pp. 16-34.

Diaz, J. (1999). The first decade of behavioral research in the discipline of property. Journal of

Property Investment & Finance, Vol. 17 Iss. 4, pp. 326-332.

Diaz III, J., and Hansz, A. J. (2010). A Taxonomic field investigation into induced bias in residential real estate appraisals, International Journal of Strategic Property Management, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 3-17.

Fischhoff, B. (1982). Debiasing, In Kahneman D., Slovic, P., and Tversky, A. (eds) Judgement

under uncertainty: Heurastics and Biases, pp. 422 – 444. Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge England,

Fischhoff, B. (1988) Judgement and decision making, In Eds. R. J. Sternberg, & E. E. Smith.

The psychology of human thought. New York, Cambridge University Press.

Furnham, A., and Boo, H.C. (2011). A literature review of the anchoring effect, The Journal of

Socio-Economics, Vol. 40, No. 1, pp. 35-42.

George, J.F., Duffy, K., and Ahuja, M. (2000), Countering the anchoring and adjustment bias with decision support systems. Decision Support Systems, Vol. 29, Iss. 2, pp. 195-206.

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Journal of European Real Estate Research

Hansz, A. (2004). Prior transaction price induced smoothing: testing and calibrating the Quan-Quigley model at the disaggregated level, Journal of property research, Vol. 21, No. 4, pp. Hastie, R., & Dawes, R. (2001). Rational choice in an uncertain world: The psychology ofjudgement and decision making, Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications.

Joslyn, S., Savelli, S., and Nadav-Greenberg, L. (2011), Reducing probabilistic weather forecasts to the worst-case scenario: anchoring effects, Journal of Experimantal Psychology:

Applied, Vol. 17, pp. 342-353.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J.L., and Thaler, R.H. (1990). Experimental Tests of the Endowment Effect and the Coase Theorem, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 98, No. 6, pp. 1325-1348. Kaustia, M., Alho, E., and Puttonen, V. (2008). How much does Expertise Reduce Behavioral Biases? The case of Anchoring Effects in Stock Return Estimates, Financial Management, Vol. 37, pp. 391-411.

Klamer, P., Bakker, C., & Gruis, V. (2017). Research bias in judgement bias studies–a systematic review of valuation judgement literature. Journal of ProPerty research, Vol. 34, Iss. 4, 285-304.

Klamer, P., Gruis, V., and Bakker, C. (2019). How client attachment affects information verification in commercial valuation practice, Journal of Property Investment & Finance, Vol. 37, No. 6, pp. 541-564.

Levy, D.S., and Frethey-Bentham, C. (2010). The effect of context and the level of decisionmaker training on the perception of a property´s probable sale price. Journal of

Property research, Vol. 27, No. 3, pp. 247-267.

Millington, A.F. (2013). An Introduction to Property Valuation, 5th ed. Taylor and Francis.

Newell, A., & Simon, H. A. (1972). Human problem solving, Prentice-Hall Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Northcraft, G.B., and Neale, M.A. (1987). Experts, Amateurs, and Real Estate: An Anchoring-and-Adjustment Perspective on Property Pricing Decisions, Organizational Behaviour and

Human Decision Processes, Vol. 39, pp. 84-97.

Pagourtzi, E., Assimakopoulos, V., Hatzichristos, T., and French, N. (2003). Real estate appraisal: a review of valuation methods, Journal of Property Investment & Finance, Vol. 21, No. 4, pp. 383-401.

Papastamos, D., Matysiak, G., & Stevenson, S. (2015). Assessing the accuracy and dispersion of real estate investment forecasts. International Review of Financial Analysis, Vol. 42, pp. 141-152.

Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors. (2017), RICS Valuation: Global professional

standards, Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors, London.

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Journal of European Real Estate Research

Salzman, D., and Zwinkels, R.C.J. (2017) Behavioral Real Estate, Journal of Real EstateLiterature, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 77-106.

Seiler, M.J. (2014). Beharioral Real Estate in Eds. Baker, H.K., & Chinloy, P. Private real

estate markets and investments. Oxford Press.

Sent, E. M. (2004). The legacy of Herbert Simon in game theory. Journal of Economic Behavior

& Organization, Vol. 53, Iss. 3, 303-317.

Sharp, G.L., Cutter, B.L., and Penrod, S.D. (1988). Performance feedback improves the resolution of confidence judgements, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision

Processes, Vol. 42, Iss. 3, pp. 271-283.

Tang, F.Y., and Lin, T.M.Y. (2017). Knowledge and Anchoring: Verification of Three Circumstances in Which Knowledge Does Not Interfere with Anchoring, Open Journal of

Social Sciences, Vol. 5, No. 7, pp. 144-164.

Thaler, R. (1980). Toward a positive theory of consumer choice. Journal of Economic Behavior

& Organization, Vol. 1, Iss. 1, 39-60.

Thomas, N. Simon, D.H., and Kadiyali, V. (2010). The price precision effect: Evidence from laboratory and market data, Marketing science, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 175-190.

Tomer, J. F. (2007). What is behavioral economics?. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 36(3), 463-479.

Tversky, A., and Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgement under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases,

Science, Vol. 185, Iss. 4157, pp. 1124-1131.

Winer, R.S. (1986). A Reference Price Model of Brand Choice for Frequently Purchased Products, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 13, Iss. 2, pp. 250-256.

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60