Degree project in nursing Malmö University

PREVENTIVE NURSING

AN INTERVIEW STUDY ON CERVICAL

CANCER IN SOUTH-WESTERN UGANDA

RADAK LINDA

PREVENTIVE NURSING

AN INTERVIEW STUDY ON CERVICAL

CANCER IN SOUTH-WESTERN UGANDA

LINDA RADAK

MATILDA REDEMO

Radak L & Redemo M. Degree project in nursing 15 credit points. Malmö University: Faculty of health and society, Department of Care Science. 2015.

Aim: The aim of this study was to elucidate how nurses/midwives perceive the

possibilities and obstacles to practice preventive nursing regarding cervical cancer in Uganda.

Background: Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer form amongst

women worldwide. The highest incidence of cervical cancer is found in sub-Saharan Africa. In Uganda there are few nurses and midwives to support cervical cancer screening and health talks. With the right preventive measures the

incidence rate could be decreased.

Method: A qualitative study design based on eight semi-structured interviews.

The data was analysed using content analysis.

Results: The perceived possibilities to practise preventive nursing were prevention

through screening, outreaches and treatments, prevention through health education and practical training plus financing. Obstacles elucidated during the interviews were lack of support from the government, remote places hard to reach, attitudes in the community and lack of knowledge.

Conclusion: In order to enhance the preventive measures regarding cervical

cancer, Uganda is in need of better funding, more trained staff, access to vaccine and adequate treatments. It would also be beneficial with a nation wide screening program.

Keywords: Cervical cancer, health education, human papilloma virus, preventive

FÖREBYGGANDE

OMVÅRDNAD

EN INTERVJUSTUDIE OM

LIVMODERHALSCANCER I SYDVÄSTRA

UGANDA

LINDA RADAK

MATILDA REDEMO

Radak L & Redemo M. Examensarbete i omvårdnad 15 högskolepoäng. Malmö högskola: Fakulteten för hälsa och samhälle, Institutionen för Vårdvetenskap. 2015.

Syfte: Syftet med denna studie är att belysa hur sjuksköterskor/barnmorskor

upplever möjligheter och svårigheter att arbeta förebyggande med livmoderhalscancer i Uganda.

Bakgrund: Livmoderhalscancer är den andra vanligaste cancerformen hos kvinnor

världen över. Livmoderhalscancer är mest förekommande i Afrika söder om Sahara. I Uganda finns det få sjuksköterskor och barnmorskor som kan utföra hälsosamtal och screening av cellförändringar. Med rätt förebyggande insatser kan incidensen av livmoderhalscancer minska.

Metod: En kvalitativ intervjustudie baserad på åtta semistrukturerade intervjuer.

Intervjumaterialet analyserades med hjälp av innehållsanalys.

Resultat: Sjuksköterskorna och barnmorskorna upplevde att förebyggande insatser

möjliggjordes genom screening, behandlingar och outreaches, hälsosamtal och utbildning av hälso- och sjukvårdspersonal samt finansiering. Svårigheterna med att arbeta förebyggande med livmoderhalscancer var bristande stöd från

regeringen, svåråtkomlig omgivning, attityder i samhället och brist på kunskap.

Slutsats: Uganda behöver bättre finansiering, mer utbildad personal samt tillgång

till vaccin och behandlingar för att förbättra förebyggandet av livmoderhalscancer. Ett nationellt screening-program som infattar hela befolkningen skulle påverka det förebyggande arbetet positivt.

Nyckelord: Förebyggande omvårdnad, humant papillomvirus, hälsosamtal,

CONTENTS

ABBREVIATIONS 5

INTRODUCTION 6

BACKGROUND 7

Preventive care 7

Preventive care regarding cervical cancer 7

HPV vaccination 8

Situation in Uganda 9

Challenges regarding cervical cancer 9

HPV vaccination in Uganda 10

Cervical cancer screening in south-western Uganda 10

Area of concern 10 Aim 11 METHODS 11 Sample 11 Ethical consideration 11 Data collection 12 Analysis of data 13

Credibility, dependability and transferability 13

RESULTS 14

Possibilities 14

Prevention through screening, outreaches and treatments 14

Prevention through health education and training 15

Financing 16

Obstacles 17

Lack of support from the government 17

Environment 18

Attitudes in the community 19

Lack of knowledge 20

DISCUSSION 21

Discussion of methods 21

Discussion of results 23

Satisfying preventive measures 23

Gender inequality in the health care system 24

Reaching all groups of women 24

Lack of support from the government 25

Aid dependency 25

CONCLUSION 26

FUTURE RECOMMENDATIONS 26

REFERENCES 28

ABBREVIATIONS

ACCP Alliance for Cervical Cancer Prevention CA cellular abnormalities

CIN cervical intraepithelial neoplasia HIV human immunodeficiency virus HPV human papilloma virus

ICN International Counsil of Nurses ICO Institut Català d’Oncologia LBC liquid-based cytology

LEEP loop electrosurgical excision procedure MOH Ministry of Health

NGO non-governmental organisation PAP-test Papanicolauo test

VIA visual inspection with acetic acid WHO World Health Organization

INTRODUCTION

Cervical cancer is the second most common form of cancer affecting women worldwide (Dunleavey, 2009). The highest incidence of cervical cancer is found in sub-Saharan Africa (Ferlay, 2011). According to Institut Català d’Oncologia’s (ICO) HPV Information Centre (2013) it is the number one most common cancer form amongst women in Uganda. However, with the right preventive measures the incidence rate could be decreased. Mwaka et al (2013) demonstrated difficulties regarding cervical cancer in Uganda, both in regards to preventive interventions and the care of cancer-patients. In Uganda there are few nurses and midwives to support screening and health talk to women. There are also few gynaecologists, long distance to health facilities, transport difficulties and a lack of vaccine due to high costs. This plays a very important role in the prevention of cervical cancer as does access to laboratories, technologists and pathologists (Sun Kuie, 2009). All of this makes it harder to implement preventive interventions and to reduce the incidence of cervical cancer (Mwaka et al, 2013). Successful

preventive interventions have been proven to have a good impact on countries incidence of cervical cancer. According to Leander (2013) preventive

BACKGROUND

Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer form amongst women worldwide. It is responsible for 9% of all female cancer deaths (Dunleavey, 2009). The early stages of the disease are normally asymptomatic. Early on the cancer is only likely to be discovered through cervical cytology and colposcopy. At later stages the most common symptoms are coital, intermenstrual or post-menstrual bleeding, offensive vaginal discharge as well as bladder and bowel symptoms (ibid).

The two biggest risk factors for acquiring cervical cancer are infection with

human papilloma virus (HPV) and inadequate screening (Dunleavey, 2009). Other risk factors have been found to be of less importance. Most people will acquire and clear an HPV-infection at least once in their lifetime (Strander, 2007). Still only a minority of women develop cervical cancer. This means that cofactors must play a part in the risk that HPV poses. Such cofactors are sexual activity, smoking, use of oral contraceptives, co-infections with herpes simplex or chlamydia trachomatis, high parity and immunosuppression by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or transplantation medication (ibid).

Preventive care

Preventive care is defined as the measures taken in order to prevent illness or injury before the onset of symptoms (Dillon, 2009). Within the spectra of

preventive care there is therapeutic interventions, like immunizations or antibody prophylaxis as well as examinations and screenings to find asymptomatic diseases in an early stage. Even with a great variety of measures, preventive care is still best explained through routine physical examinations and immunizations. Today the expression preventive care is also used for measures taken to reduce the risk of aggravating already existing conditions such as high blood pressure or Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Nevertheless, preventive care stresses the importance to prevent disease before it occurs (ibid).

Preventive care can be sorted into three different categories; primary, secondary and tertiary preventions (Dillon, 2009). The goal with primary prevention is to avoid the onset of disease and is often targeted on a wide part of the population. Such interventions could include vaccine programs, clean water or education regarding diseases. Secondary preventions focuses on finding asymptomatic diseases early on in the course of the disease. One example is the PAP-tests in order to find early cell changes in the cervix. Secondary preventions also target the risk of a certain disease to reoccur. The tertiary preventions are meant to prevent already ill people from getting worse (ibid).

According to International Counsil of Nurses (ICN), it is the nurses’ obligation to promote health and prevent illness (ICN, 2006). One important factor in effective preventive care is proper access to health care services (Purdy, 2008). This poses an obstacle since a big part of the world’s population does not have the basic conditions needed for a good health (ibid).

Preventive care regarding cervical cancer

Developing countries only have access to 5% of the world’s global cancer

2009). People with lower socioeconomic standards have got higher risk to develop cervical cancer, as they are less active recipient of screening. Comparisons

between developed and developing countries have shown that screening projects and eradicating cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) contributes to reduction in the incidence of cervical cancer (Dunleavey, 2009; Sun Kuie 2009). According to Sasieni & Adams (1999) screening tests are effective and contribute to the

effectiveness ofpublic health interventions (Dunleavey, 2009). However, none of the African countries has been able to conduct sustainable, large population based screening programmes (ibid).

The World health organization (WHO) has set a goal, which contains the recommendation that every low-income country should provide at least one cytological test during each woman’s lifetime. This has potential to reduce the cervical cancer rate by 65% (Dunleavey, 2009). Alliance for cervical cancer prevention (ACCP), expresses the following two fundamental criteria for preventing cervical cancer (Dunleavey, 2009 p. 174):

“1. The incidence of cervical cancer must justify screening

2. Necessary resources must be available and committed for attaining wide screening coverage and ensuring that adequate systems are in place to manage screen positive women appropriately.”

Preventive interventions like screening tests needs to be complemented with information about the tests’ importance and the risk factors of not having them done (Dunleavey, 2009). Sun Kuie (2009) has noticed that there is a lack of knowledge within the communities in developing countries, mainly because of economical complications. Health personnel might not always have adequate knowledge about cervical cancer and the screening. This poses an obstacle when trying to reach women with information about the importance of getting

cytological tests (Sun Kuie, 2009).

Sun Kuie (2009) pointed out some behavioural preventive interventions that will reduce the incidence of cervical cancer. These were to use condoms and educating men of the HPV, general health and sex education, delaying the onset of sexual intercourse and to lower the number of sexual partners, stop smoking cigarettes and implement healthy dietary habits. The vaccines Gardasil and Cervavix will also help reducing cervical cancer (ibid).

HPV Vaccination

The oncogenic HPV type 16 and 18 causes 70% of cervical cancer worldwide (de Sanjosé et al, 2007). The vaccines Cervavix and Gardasil can protect against these types of cervical cancer. Other oncogenic types of HPV cause the remaining 30% of cervical cancer, which cannot be prevented by these vaccinations. Screening programmes must therefor complement the vaccination program to find the remaining 30% (ibid). The prevalence of other oncogenic types of HPV seems to be higher in Sub Saharan Africa than in the rest of the world (Smith et al, 2007). A potential explanation is the high prevalence of HIV, which is a cofactor to cervical cancer. This shows uncertainty regarding how efficient vaccines would be in preventing cervical cancer in Sub Saharan Africa (ibid).

Campos at al (2012) found that the most effective health preventing strategy was a combination of adolescent vaccination followed by screening at the age of 35. The

combination of screening and HPV vaccination reduced the prevalence of cervical cancer risk by 19% - 26% (Campos et al, 2012).

Situation in Uganda

The healthcare system in Uganda is financed by the government. The government funds everything from health talk and medicine to surgery via the Ministry of Health (MOH) (Budongo, 2014). The education system is not free, there is a tuition fee for all university degrees including the nurse education. However the government sponsors a certain amount of the above average-achieving students. The nurse education in Uganda is three years long. To become a midwife you can either study for three years without first being a nurse, or you can extend your nurse education with one and half year of midwifery training (ibid).

The highest incidence of cervical cancer is found in Sub Saharan Africa (Ferlay, 2011). Every year 3500 women in Uganda are diagnosed with cervical cancer and the disease kills approximately 2400 women a year (ICO, 2013). Of all female malignancies in the country, cervical cancer poses 50-60% (Banura et al, 2012). Uganda has a high prevalence of HIV, a disease that in correlation with HPV can cause cervical cancer. In 2012 the prevalence of the adult population was 7,2% (UNICEF, 2013)

Challenges regarding cervical cancer

Mwaka et al (2013) demonstrated difficulties regarding cervical cancer in Uganda, both concerning to preventive interventions and the care of cancer-patients. In Uganda there are few nurses and midwives to support screening and health talk to women. This generates lack of awareness and knowledge about cervical cancer within the population. There are also few gynaecologists, long distance to health facilities, transport difficulties and lack of vaccine due to high costs (ibid).

A qualitative interview study conducted by Teng at al (2014) in Uganda described other barriers regarding cervical cancer screening. The women in the study

believed they were at low risk for HPV infections and cervical cancer. The study also pointed out the shortage of knowledge in the relationship between HPV and cervical cancer. Even women with adequate knowledge about the importance of screening were unwilling to get tested. They did not see any possibilities of cancer treatment and would therefor rather not get a cancer diagnosis. Another

highlighted problem was that women did not want to go to the hospital unless they had symptoms, which complicated the screening possibilities. Other obstacles were the discomfort of inserting a swab into the vagina, fear that it would cause infections or injuries and the embarrassment of giving a swab with vaginal secretions to health workers (Teng et al, 2014).

The women also talked about two different kind of embarrassment, the first one was community embarrassment and the other one was personal embarrassment (Teng at al, 2014). The community embarrassment involved worries about how others would perceive them, and the personal embarrassment was about the shyness they felt for their own genitalia. The interviews showed that women would feel less embarrassed if they would have more knowledge and education about the significance of screening (ibid).

Mwaka et al (2013) noted that there is an absence of psychosocial and family support, sometimes because of the idea that cervical cancer is contagious. Many women found it uncomfortable to be examined by a young male doctor (ibid). Economical standard and political decisions in Uganda affect these difficulties. Developing countries faces different obstacles regarding preventive care than more developed countries (Sun Kuie, 2009).

HPV vaccination in Uganda

In 2007 the two vaccines Cervavix and Gardasil were registered by the Ugandan National Drug Authority (Banura et al, 2012). Donations from Ministry of Health made it possible to introduce the vaccines to the public sector. World Health Organisation (WHO, 2009) states five criteria regarding cervical cancer vaccines. Countries meeting all five criteria are recommended to implement HPV

vaccination in the national immunization program. Uganda fulfils four out of five criteria. The one criterion that is not accomplished says that sustainable financing should be secured(WHO, 2009). Banura et al (2012) also stated that the major obstacle concerning HPV vaccination in Uganda is the cost of the vaccine. A study made by Campos et al (2012) showed that in Uganda vaccination alone is less cost-effective than screening alone. The cost of the vaccine and the fact that vaccination alone is less cost-effective than screening alone makes it hard for Uganda to use vaccination as a way to prevent cervical cancer (Campos et al, 2012). Even though it is known that vaccination of adolescents is of great importance in cervical cancer prevention (Sun Kuie, 2009).

Cervical cancer screening in south-western Uganda

WHO states that visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) is preferable when screening women for cervical cancer in low-resource settings (WHO, 2012). It is a simple and safe procedure for cervical cancer screening. Cytology-based

screenings, like PAP-tests or liquid-based cytology (LBC), are less efficient in developing countries due to lack of healthcare resources able to sustain such screening programmes (ibid). When performing VIA a speculum is inserted, the cervix cleaned and acetic acid applied (Budongo, 2014). The acetic acid

highlights precancerous lesions, one minute after applying the acid further

inspection of the cervix is carried out in search for abnormalities. When finding a small lesion this should be treated with cryotherapy or loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) (ibid). WHO deems cryotherapy, which is destroying abnormal tissue on the cervix by freezing it, as the most efficient in low-resource settings (WHO, 2012). When treatments like cryotherapy and LEEP are not available, another treatment option is hysterectomy (Kabagabe, 2014). The MOH in Uganda suggests that every woman coming for her six weeks postnatal check up should be screened for cervical cancer (Kabagabe, 2014). The screening possibilities depend on funding from the government and

non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Therefor screening intervals and screened age groups differs between hospitals (ibid).

Area of concern

Cervical cancer is one of the most common cancer diseases affecting women in Sub Saharan Africa even though preventive measures have been showed to dramatically decrease the incidence (Dunleavey, 2009; Mwaka et al, 2013). Women in low-resource settings are less active recipient of screening and are

therefore at higher risk of developing cervical cancer (Dunleavey, 2009). Still none of the African countries have been able to conduct sustainable, large population based screening programmes (ibid). Highlighting how nurses and midwives in low-resource settings perceive the preventive interventions regarding cervical cancer will give opportunities to understand which parts of the preventive care are satisfying and where improvement could be beneficial, keeping in mind the specific potentials and obstacles in the observed region.

Aim

The aim of this study was to elucidate how nurses/midwives perceive the

possibilities and obstacles to practice preventive nursing regarding cervical cancer in Uganda.

METHODS

The study was conducted through semi-structured qualitative interviews with nurses and midwives. The interviews were focused on the interviewees’ perception of the possibilities and obstacles to practice preventive nursing regarding cervical cancer. Since one of the official languages in Uganda is English, the interviews were carried out without interpreters.

Sample

The respondents were included in the study after meeting the criteria of being an English speaking Registered Nurse with experience of working with cervical cancer.

The respondents where chosen by convenience sample. Convenience sample is when choosing available participants willing to partake in the study (Polit & Beck, 2014). After mail contact with representatives from two hospitals in south-western Uganda, permission to interview nurses at both locations were given. Upon arrival the nurse in charge introduced the nurses eligible for interviewing. Five nurses and three midwives were interviewed at two different hospitals. They were all involved in the cervical cancer care or screening projects, and had three to seven yearsof experience. Some of them had worked with women’s health outreaches.

Ethical considerations

Before conducting the interviews the study got clearance from the Ethical Council of Health and Society at Malmö University. Taken into consideration was how to ensure confidentiality of respondents, how to store material and when to destroy material.

The respondents asked to participate in the study were given a letter of consent (Appendix 1)with information about the aim of the study, inclusion criteria, confidentiality and publication. All respondents were informed of the study and of the fact that the interviews were recorded. The letter also stated that partaking in the study was voluntary and that the respondent could chose to terminate their participation at any time without needing to explain why. All respondents signed a

consent form (Appendix 2) stating they had understood the information in the letter of consent and were aware that participation was voluntary.

During the course of the study the interview recordings and transcriptions were kept on two computers and one flash drive. The written study was also kept on the computers and on a different flash drive. All of these were kept in locked rooms that only the researchers had access to, and when it was not possible to lock the entire room, it was kept in lockers. When the study has been reviewed and published all interview material will be destroyed.

The interview questions were written open ended as to make sure that the

respondents could chose to talk openly about subjects they were comfortable with and could elaborate the answers as much as they wished. It was decided to

conduct the interviews in English, taken into consideration that the nurses and midwives would be university educated and therefor likely to speak adequate English.

Data collection

In nursing research, interviews are beneficial when searching for in-depth qualitative data (Maltby et al, 2010). Maltby et al (2010) compared

semi-structured interviews to some extent with natural conversations, which creates the possibility for a more genuine interaction between the interviewee and the

interviewer. Semi-structured interviews allowed the respondents to talk at length about different subjects and to bring up issues that the interviewers had not considered.

The researchers either states a list of topics or broad questions that should be covered during the interview (Polit & Beck, 2014). According to Maltby et al (2010) the use of semi-structured interviews allows open-ended questions. This means it is possible to obtain data from the respondents experience as well as from questions concerning the field in which the interviewer is interested (ibid). Polit & Beck (2014) stated the importance of encouraging the respondents to talk freely about the topics. The interviewer therefore needs to listen carefully at the content of the respondents’ answers to find out what issues are of interest, both for the respondent and for the interviewer (Maltby et al, 2010). The interviewer also needs to be flexible during the process to have the possibility to reign in the respondent with probing questions in order to create a focused interview (ibid). In total, eight interviews were conducted between the 17th of November and the 3rd of December 2014. The respondents were interviewed one by one at their workplace. Most interviews took place in private rooms but two interviews were held in a room connected to a waiting room where patients were sitting. The two study researchers partook equally in all interviews. Before the interview started the researchers introduced themselves and informed the respondents about the study. The interviews were between 30 and 45 minutes long, recorded using a dictation machine. The first interview was viewed as a pilot interview where questions were tried for the first time (Appendix 3). After transcribing, it was discussed with the supervisor and deemed usable in the study. Following interviews were modelled on this. All interviews were semi-structured with two main subjects; the obstacles and the possibilities of practicing prevention of cervical cancer. Prepared questions were brought to every interview (Appendix 4). The interviews were conducted with the help of these and other unprepared,

probing questions in order to elucidate the respondents’ thoughts regarding possibilities and obstacles met when working with the prevention of cervical cancer. The original plan was to conduct seven interviews, however, to make sure no information was overlooked and to confirm some of the information one extra interview was done.

Analysis of data

The data was recorded and transcribed. In this study content analysis has been used to analyse data. Burnard (1991) deemed content analysis suitable when collecting data via semi-structured open ended-ended interviews that has been recorded and transcribed. Content analysis aims to find patterns in the data (Maltby et al, 2010). The method creates the possibility to compress the text into fewer categories, which provides a way of understanding the content of the text (Burnard, 1991).

According to Burnard (1991) it is important to read through the transcripts over and over. At first the researchers makes notes to find general themes. Then the researchers starts coding the text. An example of coding is to look at word frequencies, most common keywords and most mentioned phrases. The coding is put together in categories and listed after suitable headings (Burnard, 1991). During the process of interviewing two main categories and several subcategories started to emerge. When reading the transcribed interviews over and over the sub-categories were set, finally being a number of seven. These were coded with a number each and text parts of the transcriptions were then coded with the same numbers. When the transcriptions had been divided in to smaller parts of text and all parts touching on the possibilities or obstacles of working preventive with cervical cancer had a number, the results were written.

Credibility, dependability and transferability

In nursing research it is important to fulfil the criteria of credibility, dependability and transferability (Polit & Beck, 2014). Credibility means to find confidence in the truth and in the interpretations of the data. To establish credibility it is of great importance to collect enough data and to select the most suitable method for data collection. This is to ensure the confidence in the truth of the findings for every participant and for the context of the study (ibid). Within this study it was decided that at least six semi-structured interviews should be conducted, eight interviews were included in the study in order to collect enough data. Dependability refers to the stability of the study. Polit & Beck (2014) clarified that if a study achieves the criteria of dependability the study can be repeated if using the same or similar participants, in the same or similar context. The researchers will then discover the same or similar findings. Therefor the method of this study is thoroughly

described and it is explained that it took place in south-western Uganda.

Transferability is when the findings of the study are transferrable or applicable to other groups or contexts. To achieve transferability the researcher needs to carefully describe the data so that others can apply the data to other groups and contexts (Polit & Beck, 2014).

RESULTS

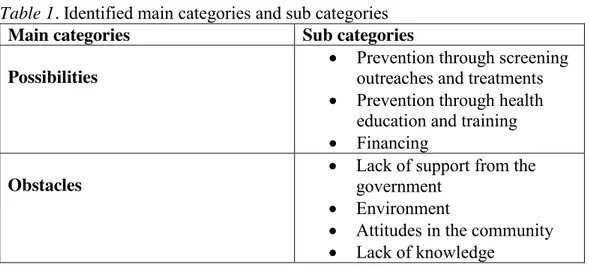

The results are presented under two main categories; Possibilities and Obstacles, and seven sub categories (Table 1). The results are based on the respondents’ perceptions of the preventive work they do regarding cervical cancer.

Table 1. Identified main categories and sub categories

Main categories Sub categories Possibilities

Prevention through screening outreaches and treatments Prevention through health

education and training Financing

Obstacles

Lack of support from the government

Environment

Attitudes in the community Lack of knowledge

Possibilities

Under this headline, the possibilities nurses and midwives perceived in preventive work with cervical cancer are stated.

Prevention through screening, outreaches and treatments

The nurses and midwives highlighted the possibility to practice preventive nursing regarding cervical cancer through screening women using visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA). The respondents perceived screening as a possibility to dramatically decrease and prevent the number of cancer diagnoses. Cervical cancer would be prevented since cellular abnormalities (CA) were found in early stages instead of developing in to advanced cancer. VIA as a method of screening for cervical cancer had been found to be the most efficient by hospital

administration according to the respondents. This method was preferred because the results would not delay or be misplaced. Screening was perceived to be one of the most important possibilities to practice preventive nursing regarding cervical cancer.

In order to efficiently practice preventive nursing regarding cervical cancer it was of importance that the nurses and midwives reached all women in the community. Outreaches were mentioned as an important way of making sure all women were included in the screening. The respondents claimed people responded well to outreaches and camps, these would attract a big number of patients. Radio was stated as an opportunity to encourage people to come to health centres for outreaches or camps. It was assumed that everyone in the community had access to a radio and therefore this was perceived as the most effective way to reach people. The outreaches would give the nurses and midwives the possibility to see people who would normally not come to the hospital unless they were very sick and provide them with health care services in their local area.

The respondents perceived the possibility to follow-up on women who had been screened as a significant preventive measure. The general notion was that women came when given a time for follow-up. Many women had been screened for their second or third time and this gave the respondents possibility to identify cellular changes over a period of time.

Access to early stage treatments, such as cryotherapy or loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) were mentioned. These gave the nurses and midwives means to treat CA directly when discovered and therefor prevented small lesions from growing. The respondents said that when women were treated on the same day that CA were found, their confidence in the healthcare system grew and they would spread this trust in the community, giving the nurses and midwives

opportunity to screen and treat even more women. The nurses and midwives stated that when the necessary materials were available to bring on outreaches, this would also present an opportunity to treat women.

Prevention through health education and training

A preventive intervention highlighted by all of the respondents as one of the most important was health educations. The nurses and midwives had noticed that this achieved increased knowledge of cervical cancer within the whole community. The health educations contained the causes and signs of cervical cancer, how to prevent it and the importance of screening. This was seen as an opportunity for the nurses and midwives to reach patients with accurate information.

“[…] cause when the ones we screen, we tell them: give the message to other people, tell them how the screening is not painful, it’s healthy, it’s for the good of your health […]”

The respondents perceived that women with correct information about cervical cancer and the screening would spread the word to the community, which generated an increased possibility to encourage more women participate in the screening.

Palliative care teams were mentioned as a possibility to practice preventive care regarding cervical cancer. These teams would nurse women with cervical cancer, and health educate them about causes and preventive measures, which the women who were already ill would then pass on to others. The respondents claimed that knowing someone with advanced cancer was a common reason for women to participate in screening themselves.

As health education was seen as an essential preventive intervention the nurses and midwives tried to reach women with this information using different methods. One way was to include information about cervical cancer in health education at other clinics, such as HIV clinics, family planning services and antenatal services. Another way to reach women was through the village health workers who visited remote villages to offer health care services. The nurses and midwives talked about village health workers and their efforts as an opportunity to reach women in the community. The village health workers health educated women, gave them information about VIA and referred patients to the hospitals for screening and treatment. The respondents stated that women, through health educations, came to understand that cervical cancer is a mortal disease. This encouraged women to come for screening.

Some of the nurses and midwives believed they reached all groups of women,

“Non educated, these middle age, old age, even these younger girls.” According

to the respondents, some of the women who came for health educations or participated in the screening felt able to ask questions and give the nurses and midwives feedback regarding the VIA. The respondents said feedback gave them the possibility to adjust the health educations according to the needs and

knowledge of the women.

Another preventive intervention was the safe male medical circumcision. Within the health educations the nurses and midwives talked to women about human papilloma virus (HPV) and explained that the virus is normally situated in the prepuce. They told women to encourage their partners to get circumcised. This would motivate men to circumcise and transmission of HPV could therefor decrease. The nurses and midwives perceived the health education given in connection to the circumcision as an opportunity to reach the men.

“[…] they tell them about the human papilloma virus which hides

in their skin. So within that education they learn that the cancer, cervical cancer, comes from their part, their organ.”

According to the respondents they could educate men about cervical cancer through health educations in preparation for circumcision and on the radio. The nurses and midwives spoke of sharing information not only with the community but also within the profession. They talked about the importance of training each other and the significance of learning through continued practical screening practise. Some of the respondents said they took every chance they got to teach nurses, midwives and village health workers in other hospitals and health clinics about cervical cancer and the screening since they saw this as an

opportunity to prevent the disease.

Financing

The nurses and midwives said that when extra funding was received this gave better options for preventive measures. Subsidies from various organisations were perceived as a major possibility. The government financed parts of the preventive care and other parts were financed by non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

“[…] we thank the team, which came to train us, and we thank the people who is funding this project. Because without their effort we would be doing nothing. And it has helped us, it has

helped our community […] some people are getting cured.”

The respondents said money was a fundamental criterion in preventive nursing. Given sufficient funding the nurses and midwives were able to train other nurses, treat on early stages and extend the screening possibilities. They also said it was possible to make governmental requests for materials needed in the clinics. Some differences regarding nurses and midwives perceived possibilities and obstacles where found between respondents employed at the two different clinics. Both clinics were focused on women’s and children’s health and were situated in hospitals in south-western Uganda. However, one was financed only by the MOH

while the other also had financial support from an NGO. The nurses and midwives explained that outside support ensured more substantial funding and therefor better access to training, staff, instruments, treatments and outreach possibilities. The respondents perceived the government’s promise of shortly giving the clinics access to HPV vaccines for adolescent girls as a possibility. However, they also said that the government tends to take long time.

Obstacles

Under this headline, the challenges nurses and midwives met in preventive work with cervical cancer are elucidated. To improve preventive cervical cancer care, the respondents stated the importance of increased staffing, knowledge skills, access to vaccines, more instruments and outreaches.

Lack of support from the government

All interviewed nurses and midwives highlighted lack of money and lack of staff as a problem that complicated the preventive work with cervical cancer. They said that it is the government’s responsibility to recruit health workers nationwide and place where needed. The nurses and midwives talked about lack of health workers as a countrywide problem. This affected the clinics, staffing was not enough and the work for the ones employed in the clinics were too heavy. One challenge for the nurses and midwives was that there were too few people trained in the VIA screening. Members of staff trained in the screening were also stationed in other wards, which reduced the screening possibilities. According to the respondents, shortage of staff led to patients not getting the screening and the treatments in time.

Vaccinations were not available. The respondents stated that immunising adolescent girls with HPV vaccine would be a helpful preventive intervention. None of the respondents knew when access to vaccines would be available in their regions. They said it is up to the Ministry of Health to decide when and how to administrate vaccines. The nurses and midwives hoped that it would happen soon. According to many of the respondents the government was assisting the clinics with basic things like health education, instruments and training. The nurses and midwives said that it was possible to make requests for materials and training from the government. However they were not very hopeful in doing so, and lack of money was a fact for the clinics. Respondents backed only by the MOH perceived that they had less material and less staff in the cervical cancer screening.

The nurses and midwives supported by an NGO would regularly go on outreaches to remote villages and perceived this as an important preventive measure. These outreaches were funded entirely by the NGO meaning the clinic only supported by the MOH could not go for screenings outside the hospital. The nurses and

midwives who were not able to go said outreaches would be beneficial for the community and that not reaching women in remote villages was an obstacle in the preventive work with cervical cancer. The nurses and midwives talked about not having enough instruments, especially when they were going on outreaches and had to divide the instruments. One respondent said:

“I think the reasons why we are having only two outreaches a

month is because of money problem. If money was there, I would think we would increase the outreach. Because it is

always hard for women to come to the hospital.”

Not having access to necessary treatments was seen as a big obstacle. In general the respondents in both clinics said funding were not enough, however, the NGO supported nurses and midwives saw more opportunities in prevention and early treatment than the ones at the MOH financed clinic. Cryotherapy and LEEP had been subsidised by the NGO and were therefor only available in one of the hospitals. When treatments were not available diagnosed patients had to wait, knowing they were ill. Therefor patients started to mistrust the health care system.

“And that is what they tell us: If we would be getting the services, really, we would also encourage others to come, but we are not getting the services then how do I encourage the rest

to come?”

The respondents talked about PAP-tests. It was challenging to use PAP-tests, as results would delay which caused patients to worry. According to the nurses and midwives the patients were happier with VIA since they did not have to wait for their results. One respondent clearly stated that PAP-tests were a good way to diagnose cellular abnormalities of the cervix, but due to money the government claimed that PAP-tests were not necessary anymore. The nurses and midwives expressed that PAP-tests would be a possibility in the preventive work with cervical cancer, however in the context of rural Uganda the complications in implementing the PAP-tests made the respondents regard it as an obstacle.

Environment

The respondents highlighted that in the area there were places hard to reach,

“deep villages”. The health centres in these villages had little medical equipment

available and were not always staffed. People in these remote villages therefor had inadequate access to health services. Deep villages complicated the preventive work with cervical cancer since the nurses and midwives could not reach the women who lived there.

“Because, there are places which don’t have radios. And where the health workers don’t reach, where the cars don’t even go, […] we have deep villages where they spent a month

without hearing a car, and the radios are not there. So those people don’t know the information. […] The government’s responsibility is to come in and reach out especially to those

deep villages. Where us, like a hospital, cannot reach.”

Lost early treatments opportunities were perceived as an obstacle in the preventive work with cervical cancer. The respondents pointed out that if a woman had cervical cancer that could not be treated locally, they referred the patient to other hospitals far away. If patients were referred to another hospital, the government would not provide transport for the patients, they would have to pay for themselves. The nurses and midwives stated that many women could not afford the transports, which resulted in lost treatment opportunities.

Attitudes in the community

It had been challenging for nurses and midwives to encourage women to

participate in the screening. One major problem was the lack of knowledge about cervical cancer in the communities. Women were dying, with signs of cervical cancer, though no one identified the disease. When people did not know the reason for their loved ones dying, they tended to think it was either untreatable or caused by something supernatural. One respondent explained:

“People would be dying without knowing why, they are dying from what? A woman would start bleeding, bleeding and die and

say it is bewitching, not knowing that is the cause of what? Of cervical cancer.”

According to the respondents, some of the common misconceptions among women were that the bleeding, discharge or pain were caused by witches or that the uterus were tired after many deliveries. The nurses and midwives saw this as an obstacle, since misconceptions complicated the health educations and the respondents’ ability to give correct information to women.

The respondents said that in remote villages people did not encounter the health care very often and would only come to know about cervical cancer and the screening after someone in the village had been diagnosed with advanced stages of the disease. It was perceived as a challenge for the nurses and midwives that women would not reach out for help from the health care until they were very ill,

“Like on some level, somehow, they don’t value their health. Not until they are very sick.” The respondents claimed that before the screening, women often

misconceived the procedure. Women would fear the speculum and believed it would hurt them and cause bleeding or infections. The respondents thought that when women heard these rumours they would be discourage from participating in screening, “They would say it is a big machine that they insert in you that will

cause you pain. And they would feel like; Ah, why should I go there? To feel that pain?”

The respondents also said that women feared the outcome of the screening. The word cancer was associated with certain death and many women would rather live unknowingly than be diagnosed with an incurable disease. One respondent said:

“They say; Then if I know I have the cancer, what next? I will die fast. So they hide from knowing the truth.”

One respondent highlighted the issue of not reaching all groups of women. Even though multiple sexual partners were stated in health education as a risk factor for contracting cervical cancer, prostitutes were not participating in the cervical cancer screening. The respondent said it was assumed the information reached prostitutes over the radio, still they did not come for screening.

The respondents perceived the men in the community as an obstacle. Very few men would come for health education and few husbands accompanied their wives to hospitals. The nurses and midwives said that though some men knew about cervical cancer others were not bothered with the information since they are not the ones affected. One respondent explained:

“I think they are not well informed. And others don’t take it seriously, they say;; Ah, it’s a disease for women, let them go

around, because I am not sick. Some have those believes.”

In general men did not come for health educations. The respondents said that many husbands were not concerned with the health of their wives or children and they were not interested in family planning. This made it difficult for women to prevent cervical cancer by spacing childbirths and delaying the onset of sexual intercourse. The nurses and midwives encouraged men to come to antenatal classes and health educations but,

“All, most, men here they don’t have the time. They rather wake up early and go to drink. But they don’t escort their women. They do not come along with their women. We find

only one in a while.” Lack of knowledge

According to the respondents cervical cancer was not commonly talked of in south-western Uganda until recently. None of the nurses or midwives had any experience of working with prevention of cervical cancer prior to the introduction of VIA in their clinics. Seven years was the most extensive experience that any of the respondents had in the cervical cancer screening. The nurses and midwives perceived insufficient knowledge regarding cervical cancer as a major obstacle in the work with cervical cancer prevention. The disease was not known to the community or to the medical staff before cervical cancer screening projects existed in south-western Uganda. One respondent said: “[…] because they didn’t,

no one knew about it actually. No one knew about it in the community, not even in the hospital, before the project came up.”

The respondents explained that during their nursing education cervical cancer was at best briefly described, and that it would be beneficial for cervical cancer

prevention if information were given at medical schools. One respondent talked of feeling unsecure, saying:

“We need more training. Because though we do it, we are not very expert. So for only one to do it, you call others so that you

work in a team. So that if we could be trained more, that even if I am alone, I am confident to carry out the screening.”

Some of the trained nurses and midwives only had a five days workshop to learn about cervical cancer and its prevention. Five days of training were not enough to make the respondents feel secure in the VIA procedure. The nurses and midwives with support from the NGO expressed more confidence in their knowledge and in the possibilities to practice preventive nursing regarding cervical cancer. They perceived that the original training were sufficient and did not express uncertainty in their own knowledge. The respondents funded only by the MOH felt training had not been enough and they said that they sometimes felt unsecure in

performing the screening on their own.

The respondents perceived that knowledge about cervical cancer still varied in different districts in Uganda. Nurses and midwives testified that when they went to some districts the knowledge were still inadequate. They talked about

outreaches where others nurses had asked about CA that they had come across when inserting intrauterine contraceptive devices which they had not been able to identify. Insufficient knowledge within the profession was perceived as an

obstacle.

The respondents also identified treatments as a knowledge gap. Even when there were access to cryotherapy and LEEP, only few nurses knew how to use the cryomachine and only one doctor could do LEEP. They wished to have more people trained in performing the treatments to make sure that patients would not have to wait for adequate care. The respondents perceived absence of early treatments to be a challenge in the preventive work with cervical cancer.

DISCUSSION

The study method is discussed under the headline Discussion of methods. Weaknesses and strengths with the study are elucidated and alterations made during the process of the study are clarified. The main findings are discussed under the headline discussion of results.

Discussion of methods

The aim of the study was to elucidate how nurses/midwives perceive the possibilities and obstacles to practice preventive nursing concerning cervical cancer. A qualitative method was chosen to best understand the nurses’ perceptions of the possibilities and obstacles to practice preventive nursing concerning cervical cancer. The study design ensured a natural conversation between the interviewee and the interviewer. The researchers gained a deeper understanding of the respondents’ view on possibilities and obstacles in the preventive work with cervical cancer by using a qualitative study design. Semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions gave the respondents opportunity to talk openly about the subject. The researchers believed that the information required were truthful, however it is uncertain if the respondents actually spoke freely of the topics. When using a qualitative design the

researchers cannot be sure about the truth of the data, but has no other option than to trust the respondents (Polit & Beck, 2014). To achieve credibility of the study the researchers tried to make the respondents feel comfortable by introducing themselves and the study. This to ensure that the respondents understood their confidentiality and that participating in the study was voluntarily, as well as to acquire truthful data.

At first the respondents thought they would be interviewed in a group. The researchers therefor had to clarify the importance of interviewing the nurses and midwives one by one. The interviews were carried out in English. Both

respondents and researchers spoke adequate English. However, coming from different cultures and having different mother tongues could have affected the understanding on both parts. Some of the interviews where held in less private rooms where the interviews were interrupted by colleagues and students. Two interviews were held in a room connected to a waiting room where patients were sitting. The researchers were ensured that these patients did not speak English and could not understand what was said. This could have interfered the interviews,

however it did not seem too disturb the respondents and the interviews could continue. It could also weaken the confidentiality of the study since these respondents could be recognised by the people who interrupted the interviews. Confidentiality was otherwise kept by keeping recording and transcriptions in locked rooms and by making sure only the researchers knew the identity of the respondents.

The first interview was carried out as a pilot interview. An interview guide was prepared and tried for the first time during this pilot interview. The interview guide contained two main questions regarding the possibilities and obstacles to practise preventive nursing. The two main questions were found to be insufficient, as the respondent did not elaborate any of the answers. This caused a too short interview with poor result material. In order to get a more substantial interview the researchers had to improvise and ask the respondents other non-prepared questions. According to Maltby et al (2010) the interviewer need to be flexible during the interview to create a focused interview. The pilot interview containing the improvised questions was found to be adequate for the aim of the study and was therefor chosen to be included in the results. For the following interviews an interview guide that resembled the improvised pilot interview was arranged. The interviews were recorded in order to be able to listen to the material over and over while transcribing. The transcriptions made it possible to analyse the content by discovering patterns, themes and categorising the findings. Burnard (1991) meant that this is of great importance when using content analysis. A possible hazard in using a voice recorder was that it could have disturbed the respondents, making them feel insecure and self-conscious.This did not seem to be a problem during the interviews, and according to Polit & Beck (2014) the respondents usually forget about the recorder.

The respondents were chosen by convenience sample. Convenience sample can be a weakness since the selection of respondents might not represent the larger population (Polit & Beck, 2014). However there were a low number of potential respondents meeting the inclusion criteria, meaning the same respondents would have been chosen either way. Five nurses and three midwives were interviewed. The intention was to interview nurses, however it was discovered that there were not enough nurses working with cervical cancer in the two clinics. That is why the researchers decided to include midwives as well. In some cases the educations differed between the nurses and midwives, which could have resulted in diverse knowledge amongst the respondents. But as nurses and midwives worked in the same way regarding cervical cancer, and as all had at least three years of

experience, we do not believe this affected the findings of the study.

Using a qualitative study design makes an exact replica of the study improbable. The results depend on the respondents’ personal experience and perceptions, which is individual. This also makes the question of transferability less crucial in qualitative research than in quantitative research. However, the interviews’ structure with open-ended questions and one explicit topic in mind makes the study repeatable and ensures dependability.

It was difficult to find material regarding preventive nursing. A preventive nursing theory would have improved the study and the lack of it is seen as a weakness. This is a problem for the field of preventive nursing in general. Further research

on preventive nursing would fortify the knowledge of the nursing professionals, and therefor improve preventive care in general.

Another limitation is the size of the study. Having only eight weeks to collect material and terminate the study could mean that some findings were overlooked. With more time further interviews could have been conducted and additional hospitals could have been included which would have given the study more credibility.

Discussion of results

The discussion of results is focused on satisfying preventive measures, gender inequality, shortage of economical resources and aid dependency.

Satisfying preventive measures

The nurses and midwives perceived health educations as one of the most

important preventive interventions regarding cervical cancer. According to Dillon (2009) education about the disease is an efficient primary preventive measure. Primary preventions ought to target a wide part of the population (ibid). The nurses and midwives talked about the significance of reaching all women. To spread knowledge within the whole population, both women and men, the nurses and midwives health educated through radio and through other health care services.

The respondents highlighted screening using VIA as another important preventive measure. VIA is a secondary prevention used to find asymptomatic disease on early stages (WHO, 2012). PAP-tests are known to be effective when trying to prevent cervical cancer(Dillon, 2009).Still, VIA is the preferred screening method in developing countries (WHO, 2012). According to the respondents VIA was the most efficient method, because the results would not delay or be

misplaced as they would when using tests. On one hand using LBC or PAP-tests makes the results more reliable and will bring less inadequate samples. When using VIA, the nurses and midwives have to be well trained in finding cellular abnormalities. If the nurses or midwives are not confident in VIA it will generate a higher risk of human error. On the other hand, using VIA is beneficial when facilities sufficient for LBC or PAP-tests are not available, since the outcome will be unsecure test results. Shortage in trained staff, money and transportation will cause delays and incorrect results of cytology-based tests.

The nurses and midwives also mentioned early stage treatments, cryotherapy and LEEP, as a way to prevent cervical cancer. Cryotherapy and LEEP are secondary preventions that will inhibit the cell changes of the cervix to advance. According to WHO (2012) cryotherapy is considered to be the most useful treatment in developing countries. The results showed that when cryotherapy was not available at the hospitals it posed a major obstacle for the nurses and midwives to practise preventive care. The only option when early treatments were not accessible was hysterectomy. Hysterectomy is a more invasive treatment associated with numerous risks. Constant access to cryotherapy would make it easier for the nurses and midwives to prevent cellular abnormalities to progress into cervical cancer. Tertiary prevention mentioned by the respondents was the palliative care teams. The palliative care teams nursed people with diagnosed cervical cancer, providing them with the best possible standard of life.

In the geographic area studied, all levels of preventive interventions were

implemented. However, there are still further steps to take in providing sufficient preventive care. The respondents discussed issues that had to be improved. Among these were access to vaccinations and early stage treatments, and motivating men to come for health educations and accompany their wives. To improve these areas the nurses and midwives needed more economic resources.

Gender inequality in the health care system

A major challenge for the nurses and midwives was the lack of knowledge about cervical cancer in the community and in the hospitals. The nurses and midwives said that women had misconceptions about cervical cancer, the screening

procedure and that they did not always value their health. All of this would result in women dying without knowing the cause.

Another reason for the lack of knowledge is that few low-income countries have access to cervical cancer prevention. Where women health services has been improved, it focus on antenatal care rather than sexual violence, mental health and cervical cancer (WHO, 2009).

Cervical cancer is a disease that affects women. A possible reason for the lack of knowledge regarding cervical cancer is the gender-based inequalities within the health care system. Gender-based inequalities content slow recognition of health problems that affect women, differential vulnerability and exposure to illness, unfair treatment possibilities and limited or misdirected health research regarding women’s health needs (Sen & Östlin, 2008). This has resulted in problems with diseases like breast and cervical cancer, mental health issues among many others (ibid). It is probable that the societies’ low level of knowledge regarding cervical cancer is due to the lack of interest in diseases that affect women.

The nurses and midwives faced challenges with men in the community. The men did not come for health educations nor did they follow their women to the

hospitals. Mwaka et al (2013) stated that absence of men’s emotional and financial support impedes on the cervical cancer screening. HPV is normally situated in the prepuce of the men, therefor it is of great importance that men also know about HPV, its transmission and prevention.

Sen and Östlin (2008) explained that governmental organisations and health care systems are usually male dominated and built on norms of men. Working towards gender equality within male dominated institutions is a challenge, as people are required to think and act in new ways. The nurses and midwives did talk of the importance of getting in contact with and health educate men. The results showed that health professionals were trying, however structures within society were continuously working against them. To be able to reduce the transmission of HPV and the prevalence of cervical cancer men has to take their responsibility (Mwaka et al, 2013), and health systems in general need to start focusing more on

women’s health issues.

Reaching all groups of women

Many of the respondents perceived they actually reached all groups of women. This seams to be unlikely as the nurses and midwives also talked about “deep villages” where access to radios and roads did not exist. One respondent highlighted the issue of not reaching prostitutes. It was assumed that the

information reached prostitutes via radio but still they did not come for screening. According to WHO (2009) reproductive health services mostly focus on married women and ignore unmarried adolescents and marginalised women like

prostitutes.

All the respondents used the word mother when talking about women. According to Arrhenius (1999) women are valued by her sexual and reproductive functions. Arrhenius (1999) also discussed the issue of a women only being seen as a real women if she is a mother. To use the word mother instead of woman is a way to focus exclusively on married women or women with children. The government has implemented a nation wide screening program, though this only reaches women coming for the six weeks antenatal check-up. What will happen to the women without children, will they be ignored by the system and not get the health care they need?

Lack of support from the government

The result showed that lack of money is perceived as a big obstacle in the cervical cancer prevention. The nurses and midwives said that shortage of staff and

equipment affected their work. Having financial support from an NGO made sure one of the clinics in the study had more access to staff, training and treatment options than the other clinic that relied only on the government. This is a problem for the whole country. Both the government and outside donors are increasing the financial support, and the health care system in Uganda is improving (MOH, 2012). Staffing at national level is satisfactory, however rural district is lacking staff and in health centres less than half of the positions are filled. And even though financing is growing, so are the needs. The gap in the workforce size recommended by WHO will increase from 40,000 to 60,000 between 2010 and 2020 (ibid). This correlates with the respondents expressing that the government tends to take long time. Not being substantially supported by the government means that outside donors comes to play a big part in providing Ugandans with adequate health care.

Some of the respondents perceived that the government met their responsibilities by supporting the clinics with necessary material. But the nurses and midwives also made clear that prevalence of cervical cancer were higher in districts with no NGO involvement. The government have neither implemented vaccination in the geographic area studied nor successfully conducted large population based screening programmes. The nurses and midwives said that a nation wide

screening program and vaccinations would be beneficial in the preventive work.

Aid dependency

The respondents perceived outside support as a great possibility in the preventive work with cervical cancer. However, this also poses a long-term obstacle. On one hand foreign aid can potentially improve quality on civil services, establish strong central institutions, have a positive effect on economic growth and therefor

strengthen the quality of the government in developing countries (Bräutigam & Knack, 2004). The people directly affected by a certain aid-funded project will notice the positive difference. On the other hand there are several negative effect of big amounts of foreign aid in low-resource settings. Many small aid projects might destroy national institutions by absorbing its capacity. All projects need to be overseen by and reported to the government, which takes time and money (ibid). This could also lead to private foreign interests, providing large instant

sums of money, being prioritized over long-term governmental solutions. Donors wishes to set policies to be able to work according to their own experience and knowledge, this makes developing ministries passive (Bräutigam & Knack, 2004). Individuals working within ministries might not be willing to argue with donors since this will delay well-needed donations. Furthermore, aid funded project are able to pay higher salaries meaning they will attract local professionals, driving them away from local government funded institutions. Since health care

professionals are already few in Uganda this poses a threat to public health care. Paying salaries many times higher than what is possible for the government also creates resentments with the personnel left in public sectors (ibid).

To be able to prevent cervical cancer in low-income settings, governments need to take long-term economical responsibility. This to ensure that the health care systems will not have to depend on donations and be exposed to different donor interests.

CONCLUSION

The nurses and midwives perceived many different interventions essential in the preventive work with cervical cancer. These were to health educate people in the society about HPV, its transmission and prevention, symptoms of cervical cancer and to inform about the importance of screening. Another central prevention was the VIA screening, which was known to decrease the incidence of cervical cancer. To enable these preventive interventions financing from the government or NGOs was of great importance.

Lack of money was perceived to obstruct the prevention of cervical cancer. It would lead to shortage of staff, insufficient training of health workers and poor access to instruments and treatments. Another obstacle were remote villages where nurses and midwives could not prevent people from getting cervical cancer, as they could not reach the villages with information or health care services.

FUTURE RECOMMENDATIONS

In order to enhance the preventive measures regarding cervical cancer, Uganda is in need of better funding, more trained staff, access to vaccine and adequate treatments. To reach all women with cervical cancer screening, it would be

beneficial with a large population based nation wide screening program, and more nurses and midwives trained in both cervical cancer screening and in health education. The unbalanced distribution of resources between countries creates problems worldwide. As developed countries profits on developing countries, and therefor has a higher quality of living, developed countries sets the standard for what is considered an adequate healthcare system. In global perspective this is a standard impossible for everyone to achieve. This creates inequality in the preventive care where some people have unlimited access to certain preventive measures and others do not, and as a direct result they have a shorter life expectancy. Resources need to be equally distributed in order to achieve worldwide improvements on preventive care, meaning people in developing

countries have to lower their standard of living. This responsibility is on the international community and especially on developed countries.

As HPV is sexually transmitted there is need for sex education and information regarding safe sex. Uganda with its high prevalence of HIV is even more vulnerable for the effects of HPV. Countries dependent on foreign aid are easily influenced by donor countries’ ideas and norms. It is therefor an international responsibility to implement ideas on safe sex worldwide.

When there is a shortage of resources, countries need to be stricter in prioritization within all sectors including the healthcare system. Inequalities within the system, which exists in all countries, are therefor more visible in developing countries. The government makes the prioritization, it is the Ugandan government to ensure that healthcare is accessible for everyone. Inequalities within the healthcare system are indicated by the low amount of research and resources regarding women’s health issues. Women’s health needs to be seen as equally significant and further research is of importance to be able to prevent cervical cancer and other diseases affecting women. There is also a need of more research in general within the field of preventive nursing.