The Identity of Northern Ireland:

A Change over Time

Jonathan Corr

European Studies: Politics, Societies, and Cultures Bachelor Thesis

15 ECTS Credits Autumn, 2020

2 Supervisor: Derek Hutcheson

Abstract

The result of Brexit in 2016 gave rise to an imposing question for many political scholars, what will happen to Northern Ireland? The region had seen a continuous divide since its establishment under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, with violence taking center stage over three decades in what has become known as ‘The Troubles’. This period led to the death of some three thousand plus people. All had then been stabilized by the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, which sought to ensure cooperation amongst the political parties, as well as the disarmament of paramilitary groups. Brexit may now pressure this peaceful period as we see Northern Ireland becoming an increasing focal point between the Republic of Ireland, the European Union, and the United Kingdom. They all look to establish a more defined political foothold in Northern Ireland as it plays an increasingly larger role for the future of Europe. Internally, Northern Ireland also has the ideologies of its citizens who still have strong beliefs in how the region should move forward. Nationalists still long for unification, uniting Northern Ireland with the Republic of Ireland, while Unionists demand that they remain a part of the United Kingdom. Brexit is a major factor for the people of Northern Ireland, it has swayed their opinion in favor of belonging to the European Union although they still proceeded to leave at the end of January this year. This thesis explores the idea of Northern Ireland’s identity, whether it will sway in the opinion of the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland or become something new entirely.

3

4 Table of Contents

1. List of Abbreviations……….pg.5 2. Introduction………pg.6

2.1 A Northern Irish Brexit………pg.7 2.2 The 2019 British General Election………..pg.8 2.3 What’s to Come?……….pg.9

3. Previous Research & Literature Review……….pg.9 4. Research Aim and Questions………pg.11

4.1 Relevance……….pg.11

5. Theoretical framework………..pg.12

5.1 Social Identity Theory………..pg.12 5.2 Cultural Identity Theory………...pg.13 5.3 Nationalism………...pg.14 5.4 Nations………..pg.14

6. Methodology………pg.14 7. Analysis………pg.16

7.1 The Historical Factor………..pg.17 7.1.1 The Colonization of Ireland………pg.17 7.1.2 The Rise of Unionism……….pg.18 7.1.3 Irish Independence………..pg.19 7.1.4 The Partition of Northern Ireland………...pg.19 7.1.5 Conflict & Peace………pg.20 7.1.6 Historical Identity Claims………..pg.21 7.2 The Political Factor………pg.22 7.2.1 Post – Good Friday Agreement……….pg.22 7.2.2 The Current State of Affairs………..pg.23 7.2.3 The European Union & United Kingdom……….pg.24 7.3 Other Factors……….pg.25 7.3.1 Culture in Northern Ireland………...pg.25 7.3.2 Religion in Northern Ireland……….pg.25

5

8. Northern Irish Identity……….pg.26 9. Conclusion………..pg.28

9.1 Future Research………...pg.30

10. Reference List………pg.32

1. List of Abbreviations

DUP – Democratic Unionist Party EU – European Union

IRA – Irish Republican Army GFA – Good Friday Agreement NIA – Northern Ireland Assembly ROI – Republic of Ireland

UK – United Kingdom

UKIP – United Kingdom Independence Party UVF – Ulster Volunteer Force

6 2. Introduction

The history of Northern Ireland being in a state of disorder is long and difficult to comprehend. Over a period of four hundred years it has developed into a place with many different conflicting interests. It is a small region with two very distinct groups that have formed in opposition of one another. Nationalists and Republicans form a group that are very much in line with the ideology of maintaining Irish cultural heritage. They see themselves as Irish people, on the island of Ireland yet they view themselves as being cut off from the Republic of Ireland (ROI) and in fact, part of the United Kingdom (UK). Opposing, there are the Unionists and Loyalists who pride themselves on being a part of the UK. A strong relationship with the rest of the UK is integral for their survival as they do not want to see a reunification with the ROI. The justification for their causes is well ingrained into the minds of each person living in Northern Ireland. This thesis looks at this mindful battleground for the control over the direction of Northern Ireland’s identity. The past has not been kind to Northern Ireland. Nationalists and Unionists have been dealt with horrendous consequences as a result of their willingness to fight their corner. The height of destruction in Northern Ireland was witnessed over three decades, between 1968-98, a period known as ‘The Troubles’. The region endured civil unrest playing out on their streets, as civilian casualties began to mount up. Global media attention grew around it yet nothing momentous was done to calm the situation. Although peace between the two sides was eventually reached, the conflict left a stain on the region’s history but also the minds of those who lived through it. Both sides still view the militia that died for their cause as martyrs. A strong example being Bobby Sands, who was voted in as an MP while being interned for his links to the Irish Republican Army (IRA) in the 1970s. He died in prison while on hunger strike, trying to obtain special status. While physical weapons were used during this period to cause destruction and havoc, today a different game is being played out with politics. The Brexit vote and more recently, the British general election, has only added to this ongoing struggle for control. The division of Northern Ireland has become a repetitive discussion amongst politicians, showing very

7

little unity. Perhaps a change is coming, it has shown through the recent election results, indicating a want for transformation.

2.1 A Northern Irish Brexit

Britain voted to leave the EU in a referendum on its membership on the 23rd June 2016,

by a vote of 51.9% to 48.1%. This is what has been coined as Brexit, the British exit. There are many comments as to how exactly the leave party won out in the end. It is widely accepted that their supporters were grounded in the belief that immigration would be less of an issue, they would lose more of their culture had they remained, and terrorism is less of a factor by leaving (Taylor, 2017). The right-wing mentality behind the vote to leave was greatly supported by the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) and Nigel Farage, a prominent figurehead for the leave campaign. The Brexit debate was dominated by the topic of immigration, which in turn left very little room to discuss advantages such as: trade and free movement within the European Union (EU). While England and Wales voted to leave, Northern Ireland and Scotland voted to remain thus altering the relationship between themselves and the UK (Gormley-Heenan & Aughey, 2017). Further discussions were had on the topic of Scottish independence, while Northern Ireland had the immediate issue of having an external border with the EU since the ROI is one of its members. At present, there is no physical border between Northern Ireland and the ROI, it was removed during the establishment of the Good Friday Agreement (GFA). The GFA cites the condition that a united Ireland must be “freely and concurrently given” by both the north and south of Ireland (Sargeant & Paun, 2019). There has been a massive reduction in violence since the GFA, but tensions still exist. This is partly due to the segregated educational system which led to individuals from both communities developing a mindset of pro-Catholic, anti-Protestant, and pro-Protestant, anti-Catholic (Haverkort, 2013).

Garry (2016) carried out a survey via the Queen’s University Belfast, which investigated the voting behaviour of Northern Irish citizens for the Brexit referendum. Reviewing the survey, you can see that those who voted to leave the EU were predominantly Unionist and Protestant. Those who voted to remain shows clear support from those who are

8

Catholic and self-described Irish (Garry 2016). This data shows a clear division between two sides. The Catholic nationalists aligned themselves more with the EU while Protestant unionists sought to be in favour of the UK. All of this has been made visible by the political divisions of the leading parties in Northern Ireland, The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and Sinn Fein. Sinn Fein are a left-wing nationalist party, who called for a referendum on the reunification of Ireland post-Brexit. The referendum was turned down by many major players, as well as the DUP, who was and still is the largest party in the (Northern Irish Assembly) NIA. The DUP, unlike Sinn Fein, take their seats in the House of Commons which can be seen as the central political sphere in Britain. Due to Sinn Fein’s absenteeism the DUP have a stronger say on the political discourse of Northern Ireland.

2.2 The 2019 British General Election

Boris Johnson and his conservative party were able to secure a solid victory against his political opponents in the 2019 British General Election. This election was a Brexit election, whose result gave Johnson the power to finally ‘Get Brexit Done’ (Zurcher, 2019). Johnson had a pending deal with the EU to get his Brexit bill passed but needed the support of the House of Commons, and it was only possible to get that with a general election. The results of the general election put Johnson in prime position to achieve his goals, while at the same time the DUP made losses and SF made gains in regard to the number of seats in their constituencies. The DUP’s Westminster leader Nigel Dodds lost his seat (Kommenda et al., 2019) which was a major blow for the party considering the traditional Irish nationalist parties gained a majority over traditional Unionist parties for the first time in history.

With more of a commanding role in Northern Irish politics, nationalist parties could start the conversation around the idea of Irish reunification once again. What has been made clear politically by the results of both the Brexit referendum and the 2019 British General Election is that Northern Ireland can no longer be definitively viewed as a central hub for unionism. How the citizens of Northern Ireland politically lean now is up for debate. Unionism is still an integral part of the culture and many identify as British rather than Irish. What can be said is that the results of the Brexit referendum imply that Northern Ireland would not necessarily like to have one Ireland, but the majority would prefer to remain a part of the EU. Furthermore, the general election results tell us that nationalism

9

is continually on the rise. Whether a correlation can be made between the nationalist parties’ stance on wanting to remain in the EU and its appeal to voters has created this shift, the answer is unclear. This thesis explores around the topic, where do the allegiances of Northern Irish citizens currently lie and where could they be further down the line, and how will this alter the identity of Northern Ireland?

2.3 What’s to Come?

This thesis must look at the history of the region, the formation of its cultures, the role religion plays, and the use of politics. The next section of this thesis looks at this by examining the previous research surrounding the chosen topic, followed by an introduction to the research aim and questions of the thesis that will help us understand what exactly is being explored. After this, the thesis looks at the theoretical approach and the methodology, explaining how exactly the paper plans on answering the research problem, and the manner in which it is done. When it is clear what exactly this thesis is researching, it opens up to the analysis section. The analysis looks at the previous research on the topic, examining and taking results from it. This allows for the presentation of the data found, and what exactly it means. The thesis is then rounded up in the conclusion, offering final thoughts on what has been written and what may be valuable future research to understand the topic more wholly.

3. Previous Research & Literature Review

Many recent studies have focused on the topic of Northern Irish identity over the last number of decades, with an increasing amount of literature looking at the adaption of Northern Ireland’s identity through its rigorous years of conflict. While several researchers look at Northern Ireland’s development since the GFA, they conducted their research prior to Brexit. This literature review looks at the research done prior to and post-Brexit, as they offer varying different perspectives.

McCall (1999) looks at the shared identity in Northern Ireland and its relationship with a political landscape that is continuously shifting. He argues that the expansion of a multi-level state in the EU and the continuous Anglo-Irish obligation to the political process in

10

Northern Ireland are the two main forces at work, changing the political context for the identities of both Ulster Unionists and Northern Irish Nationalists. McKeown (2013) goes in depth to explain the causes and consequences of political violence in Northern Ireland, providing an outline of some of the key matters relating to the conflict and its conservation. Coakley (2007) reviews the various factors related to Northern Ireland’s conflict, the values both communities hold, especially in terms of their identity which in turn has created a rivalry between the two. This has led him to explore the nature of national identity and the want for belonging to a community.

Craith (2014) writes about the commitment of unionists to the British state while comparing it to nationalist demands for acknowledgment of Irish culture. Northern Ireland’s conflicting politics and the development of a shared cultural structure is examined with regards to the opposing understandings of equality and growing concerns for intercultural communication within the region’s communities. Tonge & Gomez (2015) analyze the political progression in Northern Ireland and argue how it can only balance out when the populace agrees on being only Northern Irish, rather than dominions of the British or Irish states. They look at if the communities in Northern Ireland have seen growth in their communications with one another since the GFA, leading to an end in their rivalries. Fenton (2016) looks at the media in order to identify the emerging identities in Northern Ireland post-GFA, believing that each group has their own agenda which they’d like to be the more dominant. Mitchell (2005) offers us a different perspective on identity by analyzing religion in Northern Ireland, arguing that religion provides a sense of identity for Northern Irish citizens, as well as its links to politics and community. McNicholl et al. (2018) offers us a study on how young people understand the identity of Northern Ireland, looking into the region’s divided society and the politicians that continue to drive both sides’ pomposity. McNicholl (2019) gives us an alternative take on the identity of Northern Ireland’s citizens by reviewing voting patterns. His paper argues that those who identify as Northern Irish tend to prefer moderate political parties. Interestingly, he sees Northern Ireland’s identity as a rejection of both British and Irish identities.

The chosen literature does have an overarching theme of shared identity, and the difficulties it faces in order to get to that point. There are many positions that can be taken up on this topic, although viewing Northern Ireland’s identity from different perspectives allows us to fully understand its current predicament. Whether it is culture, politics, religion, or even history that has been prioritized by the scholars on this topic of defining

11

Northern Irish identity, they all play a pivotal role in its future. This thesis connects well with the fact that it is able to see that there is always a new defining moment for Northern Ireland. Each new direction taken by the Northern Irish government always seemed to be good for one side and bad for the other. McNicholl (2019) addresses that this is no longer the case, that allegiances are slowly being less sought after. Coakley (2007) as well as Tonge & Gomez (2015) talk about the rivalries between the two communities and how it is still very much alive due to conflicts since passed. What is different however, is that they declare how both sides have grown from this violent past and now want to create a new sense of community, one that is not defined by being Irish or English. It is a region that has developed a lot over a short period of time, each new obstacle presents itself with new challenges which both sides can either work together on or point the finger at each other.

The topic of this thesis looks at Northern Irish identity in its current state, predicting where it could potentially find itself in the future. Most of the previous research on this has done a lot to explore various issues related to this thesis but it did not have the possibility of reviewing the most recent political moves. Northern Ireland can sometimes be seen to be taken in another direction than one it would choose for itself. With two distinct sides dominating the playing field, it is only a matter of time until a major event creates real change in the region. It is here this thesis relates with Craith (2014) as she talks about how the continuous divide in the community will inherently keep them as such unless change is sought out.

4. Research Aim and Questions

Northern Ireland has been transformed in many ways over the last number of decades, none more than its identity. This thesis is a study of transformation in the Northern Irish identity and how it has been reformed over time due to the factors of history, politics, culture, and religion. This thesis explores each of these factors and looks at how they have created a series of changes for the citizens of Northern Ireland, thus altering how they view their identity. With that, additional questions below will help this thesis arrive at answering the stated problem area above.

12

What role will the UK and the EU play in Northern Ireland’s future? What is the identity of Northern Ireland?

4.1 Relevance

What is the relevance in answering these questions? It is my opinion that Northern Ireland is of great importance to the future of both the UK and the EU. This is the first time in the EU’s history that a member has decided to leave. Northern Ireland is a part of the UK, yet it is a contested region due to the large portion of the population seeing themselves as both Irish and a part of the EU. The ROI still maintains its membership with the EU and in order to keep up with the terms of the GFA, there is no physical border between the ROI and Northern Ireland. This makes Northern Ireland’s current situation a deeply fascinating yet worrisome one. The questions above do not have a simple answer, they are questions being asked by the citizens as well as the politicians in the region. My examination into these questions will hopefully add clarity to the ongoing debate and allow for reasoning to prevail.

5. Theoretical Framework

The point of this thesis is to focus on what the identity of Northern Ireland is to its populace; therefore, it is necessary to align it with precise concepts and theories that are related to the topic and the research being carried out. There is a high level of academic discourse in this problem area which is why it has a limited theoretical approach to it, to keep to its primary objectives and focus only on what is important. For this part of the thesis, the aim is to summarize the use of the chosen concepts and discuss only the most relevant theories. This allows for a clear understanding of what is being said.

5.1 Social Identity Theory

The use of theories to describe inter-group conflict could be argued to work from a range of standpoints. Some focus primarily on personality and individual attributes, some consider the effects of group membership, and others are a combination of both aspects (McKeown, 2013). When it comes to Northern Ireland, social identity theory tends to be the focus as it reflects on the multifaceted interactions and differences between individual

13

and social developments (McKeown, 2013). Tajfel & Turner (1979) suggests that there is essentially a difference between both individual and group processes. Social identity theory proposes that we tend to divide up our world into social groups, and this in turn allows us all to define ourselves by the groups we feel we belong to. Furey et al (2016) believes that identity is viewed as surrounding three certain dimensions.

The first dimension refers to the identification of oneself as a member of a specific social group. Yet, self-categorization and differentiation amongst groups does not automatically produce social identification. The development of a social identity is determined by the degree in which the in-group has been unified into the sense of self (Furey et al, 2016). The second dimension is about the value people place on group membership. People act in biased comparisons of their intergroup so that they look upon themselves more positively (Furey et al, 2016). The final dimension looks at the extent in which one may feel an emotional connection to their group, how committed they are to it and how this may determine their behaviour (Furey et al, 2016).

When we categorize ourselves as belonging to certain groups, we compare ourselves with other groups, which allows us to give ourselves an enhanced self-esteem (McKeown, 2013). An example of this would be football and the way each team has its own supporters. Comparing teams in order to build one’s self-esteem is common, although such comparisons with other groups may lead to a negative outgroup attitude. When it comes to Northern Ireland, “These identities are based on inter-linking religious, national and political ideologies which are usually dichotomized into the labels Catholic and Protestant” (McKeown, 2013, pg.6).

5.2 Cultural Identity Theory

This thesis will also use cultural identity theory, although it will not be applied as much as the previously discussed, social identity theory. Cultural identity theory is an established theory that builds on the knowledge about communicative processes in use by individuals to convey their cultural group identities and relationships in particular contexts (Littlejohn & Foss, 2009). The NIA constantly brings up issues of cultural identity. Cultural representations have been given a new significance and politicians struggle with answering questions of recognition for different cultures, as well as finding the right balance of equality for the two major cultural traditions in Northern Ireland (Craith, 2014).

14

McCall (1999) argues that due to revisionism in the south from EU development, it has resulted in new enthusiasm from the people of the ROI, thus giving Northern Irish nationalists their own separate identity. When it comes to nationalists in Northern Ireland, they traditionally identify as outsiders in the British state. It is their Irish cultural identity which often goes up against one of a British mindset, leading them to find parity between Irish and British cultural traditions (Craith, 2014). Nigel Dodds was a significant political player in Northern Irish politics, before losing his seat in the British general election of 2019. He argued against the idea that a Northern Irish unionist must also be Protestant. Although, he has not denied that the political identity of Ulster Unionism is linked with the cultural identity of Ulster Protestantism. This tells us that cultural identity theory has played and continues to play an important role in defining Northern Irish identity.

5.3 Nationalism

Previous research has been carried out on the idea of nations and nation-states yet there are issues concerning the ability to agree on their definitions. This affects our ability to understand nationalism and its contents. For this reason, the theoretical framework for this thesis will clarify aspects of defining nationalism in order to give the research more clarity. Barrington (1997) values nationalism as a belief that combines a self-determined political idea, one’s primary national identity as a cultural idea, and the justification to protect the rights of a nation as a moral idea. Harris (2009) carries forward the definition of nationalism as a programme for the survival of a nation, focusing on the promotion of political aims for the nation’s people.

5.4 Nations

“Whether one believes that nationalisms create the idea of nations or that nations develop the ideas related to nationalism, one cannot discuss nationalism without considering what one means by a nation” (Barrington, 1997, pg.712). Anderson (1983) proposed that the nation be defined as an imagined political community and imagined as fundamentally limited and sovereign. The idea behind it is that members of a nation will never meet all of their fellow members yet they exist within that person’s mind. Tamir (1995) views the nation similarly, they believe it to be a community whose members share a community, with distinct similar ways, as well as the belief in a common ancestry. The social identity

15

approach by Tajfel & Turner (1979) promised the opportunity for future research, in part because it involves a solid definition on the nation as a noticeable social category of people that reverberates well with Anderson’s (1983) definition of the imagined community (McNicholl et al., 2018).

6. Methodology

This thesis’s research is structured using the qualitative method, in particular the use of a qualitative secondary analysis, meaning that it uses data that has been composed by someone else or was used to answer a different research question. Secondary analysis of qualitative data provides the opportunity to maximize the primary source’s value. However, using this type of analysis method requires careful thought and clear descriptions to be best understood, contextualized, and evaluated for effective research results (Tate & Happ, 2018). A reoccurring problem with illustrating any research strategy, design, and method, is outlining the ideal approach. There is a tendency to create something that represents all that is needed for the research to be done coherently, yet that may not be reflected throughout the entire paper (Bryman, 2012). The re-use of archived datasets and secondary analysis has built momentum over the years due to researcher’s recognition. Their work offers accounts that debate their primary research yet it may have never been analyzed in a particular way (Long-Sutehall et al., 2010). This method was chosen partly due to the accessibility of sources and the wide range of research that has already been carried out on the chosen topic. Using existing primary datasets that are readily available for secondary analysis can be said to facilitate training for new researchers (Long-Sutehall et al., 2010). This thesis discusses a somewhat sensitive topic and so it is beneficial when starting out to use secondary analysis in order to gain a grander scope of the problem area.

Having said that, there are disadvantages when it comes to using this type of methodology. For one, the thesis has a lack of familiarity with the chosen data as it was generated by other researchers. Had we applied our own data for this thesis, we would have had a better understanding of it. Using data made by others requires a period of time to become familiar with it (Bryman, 2012). There is also the issue of having no control over the data’s quality. This type of analysis is fantastic for students to examine data of higher quality but that is potentially dangerous in itself. One must be aware of how useful the data they are using actually is, and never take it for granted (Bryman, 2012). Lastly, we can also look

16

at how there may be the absence of key variables. Secondary analysis means that data is analyzed for the purposes of those who were looking for particular results in a certain area, which means their variables may differ from yours (Bryman, 2012).

There are many other research methods that could have been applied to this thesis and would have been a good fit. An example of one of these methods is as a discourse analysis. This research method highlights the use of language and analyzes an ensemble of ideas and concepts using texts where meanings of social reality are formed (Halperin & Heath, 2017). There are benefits of applying this type of analysis, although this thesis is not a study of language. Therefore, it felt as if it would have held the thesis back in a way in which it didn’t allow for an approach to the research questions. The thesis’s research method is by no means perfect, yet it does have a clear idea of the approach it wants to take.

Due to the use of qualitative research, interpretivism is the epistemological approach here. “The term subsumes the views of writers who have been critical of the application of the scientific model to the study of the social world and who have been influenced by different intellectual traditions” (Bryman, 2012, pg.28). Interpretivism takes up an anti-positivist position which is found in phenomenology. It is a philosophy that is troubled by the question of how individuals make sense of the world around them and how in particular, the philosopher should bracket out biases in their understanding of that world (Bryman, 2012).

In order to answer the research question, the thesis follows a qualitative comparative research design in the analysis. Qualitative comparative analysis is a study that typically involves learning about facts that we do not know by using the facts that we do know, therefore establishing inference (Thomann & Maggetti, 2017). Bryman (2012) says that this design requires the study of two opposing cases using more or less identical methods. What it represents is the logic of comparison; in that it suggests that we can comprehend social phenomena better when compared in relation to multiple expressively contrasting cases and/or situations (Bryman, 2012). This thesis is looking at Northern Ireland as a case study and how its identity has been altered over time due to various different factors. It is a comparative case study due to the analysis being carried out in order to answer the research question. There are two distinct sides when it comes to identifying Northern Ireland’s identity and so multiple texts must be examined in order to draw comparisons

17

and analyze the arguments they use. It must be said that the use of analyzing multiple texts is important, so the text does not draw up any biases. Both sides use similar theoretical approaches so it’s interesting to draw conclusions away from their understanding of said theories.

7. Analysis

“The expression ‘there are two sides to everything’ is commonplace and Northern Ireland is a true reflection of this, where there really are two (or sometimes more) sides to everything” (McKeown, 2013, pg.2). The following analysis chapter is broken down into four sections: the historical factor, the political factor, the cultural factor, and the religious factor. Each of these are deeply analyzed in order to define the current of state Northern Irish identity finds itself in. This is done by examining previous research done on the region, as well as taking a look at various news articles that may offer a specific opinion on a certain issue. Furthermore, this thesis investigates how the previously stated factors may indeed affect Northern Ireland’s future within Europe. Each section is given a comparative discussion, as well as a presentation of its findings.

7.1 The Historical Factor

This section examines how history has led to the current problem of identity between two factions in Northern Ireland. In the theoretical framework we discussed both social and cultural identity theory and how they apply to Northern Ireland. Here, we can see both of these theories from a historical perspective first. Briefly focusing on the colonial history in the beginning, we move towards Irish independence and the partition of Northern Ireland. From there, we look at the establishment of Northern Ireland, The Troubles, the GFA, and finally the current position of history in Northern Ireland and how its role is of the utmost importance for claims of identity. This historical analysis is based around the research of previous scholars’ work and how they’ve interpreted the history of Northern Ireland. Most importantly, this is a summary of the historical developments of Northern Ireland and they have contributed to its current situation it finds itself in.

18

Recalling what Northern Ireland was in the past is a well vocalized memory of those living on the island of Ireland today. It’s where this thesis is able to begin in terms of branching out, as well as being able to openly discuss the division we see today in the region. Northern Ireland’s history stems back to 1170 following an invasion of Dublin from England, leading to the establishment of an English monarchy (McKeown, 2013). In the northeast you have the province of Ulster, the clans were relatively successful in asserting their independence, keeping the traditional Gaelic social structure alive up until the late 16th century (Rönnquist, 2001). The rest of the island of Ireland had started building

feelings of resentment towards the British at this time. When the British saw that they must convert the Irish to the Protestant religion, they introduced several ‘penal laws’ which were intended for Irish Catholics to forcefully encourage them to adapt to Protestantism and change over to the Church of England (Haverkort, 2013). The 17th

century saw a massive arrival of Protestants from the UK into Ireland, with the intent of gaining control for government in England (McKeown, 2013). During this period, in large parts of Ulster, we saw the introduction of Protestant peasants from Scotland primarily due to it being so geographically close to Ulster (Rönnquist, 2001). This period became known as the Ulster Plantation. The Plantation of Ulster is of the utmost importance to Northern Irish Protestants, as they view ancestry, not religion, as the most significant component in their identity (Rönnquist, 2001). During this time, land was highly disputed between Catholics and Protestants, with the latter often gaining the better quantity and quality of land. This led to a series of conflicts between the two sides in the 17th century

on the island of Ireland (McKeown, 2013). In order to secure more direct control of Irish affairs after the 1798 Irish rebellion, Britain eradicated the Irish government through the 1801 Act of Union and forced direct rule on Ireland, leading to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (Holloway, 2005). According to the IRA, the rebellion of the United Irishmen in 1798 saw the beginning of Ireland’s struggle for freedom (Rönnquist, 2001).

7.1.2 The Rise of Unionism

“The turning point in Young Ireland’s development into a revolutionary movement was “the Great Famine” between 1845 and 1850” (Rönnquist, 2001, pg.135). Tenant farming in mid-19th century Ireland saw a population dependent on it for a living. Farms were small and improvements to the land was the responsibility of the tenant, who had to pay the rent as well as feed his family (Holloway, 2015). With such a heavy reliance on one

19

crop, the potato, disaster struck in the form of a potato blight in 1845 and over the following years it would lead to the death of over one million people (Holloway, 2015). After the famine, an initiative grew to form an organization associated with fighting back against the British state. This came to fruition with the founding of the Irish Republican Brotherhood in 1858 (Rönnquist, 2001). Their violent campaign for freedom in 1867 failed but under political initiatives led by Charles Stewart Parnell, Ireland had more success resulting in the first Home Rule Bill in 1886 (Holloway, 2005). By this time, Northern Ireland had a clear Protestant Unionist majority, and therefore feared Irish Nationalists taking back control of the island of Ireland. The third Irish Home Rule bill was introduced in 1912 and was all but passed, but due to the disruption of World War One in 1914 it did include the condition that Irish self-rule would not be instigated until the war was over (Rönnquist, 2001). Ulster Unionists feared the passing of the third Home Rule bill, convinced it would be detrimental to Protestants’ religious and civil liberties (Holloway, 2015). They vowed to defend their citizenship by signing the Ulster Covenant and forming the (Ulster Volunteer Force) UVF to resist Home Rule (Holloway, 2015).

7.1.3 Irish Independence

Everything changed on the 24th of April 1916, when the Easter Rising took place. Irish

Volunteers and other Irish Nationalists occupied a series of buildings in Dublin, including the General Post Office. It was there that Padraic Pearse, a leading Irish revolutionist, declared an Irish Republic. The uprising failed and resulted in the execution of its leaders, however it did produce a lot of sympathy for the cause of Irish freedom. “In a society with a deeply rooted tradition of elevating to martyrdom those who sacrifice their lives for the freedom of Ireland, the sentences must be regarded as a serious miscalculation” (Rönnquist, 2001, pg.140). Following the Easter Rising, the war of independence was fought between 1919-21, leading to the division of the island of Ireland under the Government of Ireland Act in 1921 (McKeown, 2013). Under the negotiated treaty, Ireland became the Irish Free State and the predominantly Protestant Northern Ireland fell under British rule (McKeown, 2013). This only worsened the situation in Ireland as the country fell into civil war. Irish nationalists wanted to be entirely free of British rule, and did not want to surrender six counties to them (Holloway, 2015). Those who stood for the Irish Free State did not want to return to violence and so they fought against their own

20

brothers in arms, and eventually defeated them to maintain the Irish Free State. Although independence from Britain was eventually achieved in 1949, the partition of Northern Ireland only meant the beginning of long testing period for the region and its identity. 7.1.4 The Partition of Northern Ireland

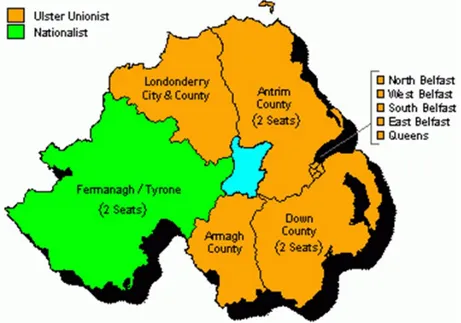

In 1921 Unionism was a success as it was able to take control of six counties of Ulster, with a large pro-Unionist majority. This was not ideal for many Nationalists as they felt isolated from the rest of Ireland, therefore making them more vulnerable (Holloway, 2015). Partition led to new divisions, Catholics wanted to remain a part of Ireland while Protestants wanted Northern Ireland to stay as a part of the UK (Haverkort, 2013). Two very distinct sides had started to form: those who wanted Northern Ireland to remain a part of the United Kingdom (Protestant/British/Unionists) and those who wanted to see Ireland unified (Catholic/Irish/Nationalists). Unionists were also called loyalists and the Nationalists also called republicans. For 50 years, between 1922-72, the Ulster Unionist Party held power at Stormont Parliament, which meant Protestant and loyalists were well represented, while the Catholic minority was subjected to many levels of discrimination (Rönnquist, 2001). Figure 1 shows a picture of the Westminster elections of 1922, clearly indicating in the orange Unionist majority in Northern Ireland.

Figure 1. Westminster elections 1922 (Kelly, 2007)

To make matters worse for nationalists, the government in London did not intervene and so their civil rights were ignored (Rönnquist, 2001). Nationalists found themselves in a

21

state which they could not identify with, as well as being treated like second-class citizens (Holloway, 2015). There was fear on the Unionists side, they saw that Nationalists sought for the unification of Ireland yet they did little to encourage them to feel included within the State and continuously discriminated against them (Holloway, 2015). This only drew the two sides further away from each other, being unable to identify with the other’s cause, the region was quickly reaching its boiling point.

7.1.5 Conflict & Peace

The emergence of the Northern Irish conflict in 1968, known better as ‘The Troubles’, saw researchers develop an interest in intergroup relations in the region at this time (McKeown, 2013). In 1967, the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association was formed. It was a non-sectarian organization, and it was only concerned with social and legal reform through peaceful means (Haverkort, 2013). However, Holloway (2015) argues that Unionists were suspicious of the civil rights campaign, assuming it was just a cover for an eventual attack on the State. Nonetheless, violence broke out in 1968 during a three-day civil rights march by Catholics. Unionists launched attacks on the Catholics, who did not receive protection from the police who were mostly Protestant (Haverkort, 2013). Many riots across Northern Ireland rose out of this but they were significantly triggered by the connection to the Protestant parade in Derry which took place yearly and commemorated James II (Rönnquist, 2001). For Protestants, the commemoration of such historic events holds a lot of symbolic value for them as it strengthens their sense of identity in the region. Through history, its links such as those that bring them together and make them feel like they belong to a community (Rönnquist, 2001). However, for many Catholics, the commemoration of such events were often seen as provocative, often highlighting their struggle for liberation from British oppression (Rönnquist, 2001). The conflict carried on for three decades, resulting in the most violent period since Northern Ireland’s establishment. It is often mistaken as a war which centered on religion although most scholars now agree that its primary focus was the issue of nationality (Cairns & Darby, 1998).

Peace came in the form of an agreement in 1998. The GFA, which is also known as the Belfast Agreement, was backed in referendums North and South of the island Ireland and created the institutional framework allowing for British Unionists and Irish nationalists to share power in an Assembly (Tonge & Gomez, 2015). The agreement was a remarkable

22

achievement yet it did not provide a final solution on what was to be done with Northern Ireland, rather it achieved a framework for its ongoing transformation through peaceful means (Holloway, 2015). The stability of the agreement is still uncertain as we’ve seen the NIA suspended a number of times, including an almost five year period between 2002 and 2007 (Haverkort, 2013).

7.1.6 Historical Identity Claims

So how do the people of Northern Ireland look at their history now? This is a question that has many answers. When looking at Northern Ireland, competing social identities is one of the key components underpinning the conflict (Cairns, 1982). Differences between the two groups in Northern Ireland are not physically seen and as a result, group membership is not clear for most (McKeown, 2013). It is because of this, the continuous questioning of whether you are Catholic or Protestant is very apparent in their society. Maintaining one’s identity is quite complex when you consider the needs of the two sides. Satisfying the needs of Catholics would in turn, ignore the needs of Protestants (Haverkort, 2013). The recognition of either a Catholic or Protestant through surnames and accents only further supports the theory of social identity, categorizing like this can lead to negative attitudes (McKeown, 2013). Both sides make a strong case for their identity when examining the region’s history. Rönnquist (2001) argues that people tend to have several different identities at the same time. Northern Ireland is a bicultural society, divided between two cultural identities. Craith (2014) sees this as a simple view, believing that the region is seeing a readjustment of its approach to identity. When it comes to Northern Ireland’s history, both sides share the same history but from a different perspective. Neither may agree with the other’s view yet they continue to merge together. From a historical perspective, Northern Ireland was Irish, then it became predominantly British, and even though both sides have claims to the past, it is their identities which separate them today, otherwise it can be said that they are the same.

7.2 The Political Factor

Northern Irish politics is something that is still looking for a complete definition. The distinction of the two sides in the region can be clearly seen through the use of politics between Sinn Fein and the DUP. Both sides have clear red lines in what they want and don’t want. This section of the thesis is focused on analyzing how these main Northern

23

Irish political parties act, who and what they represent, how their use of politics creates a sense of identity in the region, and what the current state of politics is like. The thesis examines this through the use of the chosen theories and concepts, exploring how they apply to the wider context of Northern Irish politics and in doing so, relate back to the research question. For the purpose of this analysis, we’re only looking at post-GFA politics in Northern Ireland as that is what the chosen research covers. As well as this, we only want to examine the current state of politics in the region as it gives us a clearer picture and allows for a better understanding of what is happening now.

7.2.1 Post - Good Friday Agreement

When it comes to the concept of nationalism, it has its place and in order to prevent any negative undertones it is vital that any contradictions are eradicated. Nationalism can be a realistic strategy for stimulating several ethnic groups into unifying with one another for the sake and development of a state. What we have seen in Northern Ireland is a lack of the two primary groups rousing each other. Instead there are two prominent national identities: British and Irish. Since the partition of Northern Ireland there have been disagreements between the two groups, leading to a lack of unity. Rather, the six counties in Ulster are at a continuous midpoint, trying to find where they want to align themselves and that is where Northern Irish politics comes in. When the GFA was reached in 1998, the world marveled at such an agreement being reached, bringing an end to the region’s violence and instilling peace in the community. While the GFA can be said to have been a success in part, the road to peace here is long, especially when there are always new issues creating a divide in the community (McKeown, 2013). According to McNicholl (2019), people in Northern Ireland tend to vote and perceive the politics of the area in which they are brought up and crossing over to the other side is almost unheard of. This divide carried over to politics was evident in 2006, when negotiations between the DUP and Sinn Fein were being carried out in what is known as the St Andrews talks. Both parties focused on issues of power-sharing, human rights, finances, and much more. Due to the many differences between the parties, the agreement was hard fought yet it passed in 2007 under the Northern Ireland (St. Andrews Agreement) Act (McKeown, 2013). 7.2.2 The Current State of Affairs

24

Sinn Fein and the DUP represent the majority of the region’s voters over the last several elections. Sinn Fein’s goals of structuring the state of Northern Ireland in its own way, faces the pervasive problems of complete opposition in the form of Ulster Unionists (McCall, 1999). Earlier we discussed the results of Brexit in 2016 and the British General Election of 2019, but why did the people of Northern Ireland vote the way they did? McNicholl (2019) declares that the results from recent elections indicates that those who identify as Northern Irish have a preference in voting for moderate political parties. These moderate parties are: The Social Democratic and Labour Party and The Ulster Unionist Party. On the political scale, both parties can find themselves more towards the center as opposed to Sinn Fein and the DUP who are at the opposite end of one another. While both parties have faced a number of issues over the past several decades, none is more apparent today than the goal of maintaining the identity of the people they represent. While the Northern Irish identity may seem like an internal affair, it is not. The scale of importance in terms of how politics plays out in the region in the coming years is much larger than you may think.

With Brexit having come and gone, the issue of the border between the ROI and Northern Ireland is still ongoing. It’s a controversial issue as it’s become an external EU border. There was a border in place before which was established in 1922 and during the Troubles there were even British military checkpoints. It was only in 2005, through the implementation of the GFA, that the last border checkpoint was removed, thus creating an invisible border between the north and south. Brexit has created a stir in Northern Irish politics over what to do with the border as it now has the potential to affect the identity of the region. In simple terms, just the way the Irish Catholic community was cut off back in 1921 by the partition of Northern Ireland, Unionists are now being cut off because of Brexit. The threat to their identity is the fact that they have not truly left the EU as they share an open border with one of the EU’s members, the ROI. What makes this an even more interesting topic of discussion is that if the EU and UK reach the ultimatum of creating a new border that would divide the island of Ireland once again then there is the same level of threat for the Irish Catholic community. Gormley-Heenan & Aughey (2017) write that Brexit tests the hopes which nationalists have invested in the EU ‘context’ as a way to eradicate the border. The last thing either side wants to see is a return to violence, yet this may be the case given the region’s history.

25

Communal identities in Northern Ireland are experiencing the beginning to experience a shift in their political context. The progress of the EU and the Anglo-Irish political approach to Northern Ireland are responsible for this. Postmodern conditions are accountable for the globalization/localization dynamic in their current society. These conditions have impacted the modern state boundaries and are starting to seize the territorial code that has been the cornerstone of their modern politics. As a result, numerous communal truths are stimulating the ‘objective’ truth of the main socio-political group, established in modernity, and are finding appearance within related EU and Anglo-Irish political arenas (McCall, 1999). Further development of the EU challenges the nation-state, hints of post-modernity from EU initiatives are affecting Ulster Unionist and Irish Nationalist communal identities (McCall, 1999). The continuous growth of the EU can see Northern Ireland being fought over by the UK and the EU as it stands for much more than just an additional piece of their geopolitical puzzles. Brexit presented new challenges for the EU and the UK, they had to approach the issue of Northern Ireland in a careful manner so the communities in the region felt heard and understood. Currently, Northern Ireland is part of the UK but that may change in time, especially after the Brexit result with public opinion in the region favouring the EU’s potential over the UK’s. 7.3 Other Factors

When we think of the other factors that help us better understand the identity of Northern Ireland, we must take into consideration both religion and culture. There are many multicultural societies that have multiple religions diverging with one another. “Since culture is concerned with the meaning of life and religion has similar concerns, culture and faith tend to be interlinked” (Craith, 2014, pg.118). Both religion and culture have been used by nationalists and unionists to create greater claims of identity over the preceding decades. Mitchell (2005) states that the conflict in Northern Ireland was never a holy war, although religion does play a significant role in politics and society.

7.3.1 Culture in Northern Ireland

As a concept, culture captures the idea of what difference means (Craith, 2014). Placing yourself within a distinct cultural group means you are aware of the limits to this imagined community (Craith, 2014). This means, you know that there are other cultural groups, and this is none more apparent than in Northern Ireland, two groups competing for the expansion of their cultures. Education is thought to be one of the main ways to progress

26

group relations in culturally divided societies like Northern Ireland, placing a focus on the next generation (McKeown, 2013). The integration of schools has the possibility to improve relations between Protestants and Catholics in Northern Ireland, although there are only small pockets of this in the region so creating a positive influence of a shared culture is hard (Craith, 2014). Today, with the geopolitical map of Northern Ireland looking increasingly harder to understand, we must take into consideration the issue of acceptance of the other’s culture in the region. McKeown (2013) argues that Northern Ireland has an ‘avoidance culture’, meaning that it continuously fails to openly discuss issues relating to politics, religion and the community. “A lack of recognition for the cultural identity of a community that is different is first and foremost a failure to recognize that the members have separate and distinctive identities with their own trajectories, narratives and values” (Craith, 2014, pg.18).

7.3.2 Religion in Northern Ireland

According to Coakley (2007), religion has been the most important factor when it comes to determining the national identity of Northern Ireland. Religion has been at the center of Irish politics since the 1600’s as it set apart two groups who were struggling for dominance over each other. The mobilization of ethnicity in the 1800’s was largely based on religious guidelines, Irish nationalism was greatly supported by Catholics and greatly opposed by Protestants (Coakley, 2007). The church and state in Northern Ireland are aware of how important their relationship is as they use each other to promote themselves. When it comes to religion it is seen as something that “remains socially significant and continues to inform political culture as well as social relationships” (Mitchell, 2005). Just like understanding how multifaceted the Northern Irish conflict was, the same can be said for religion here. It is so intermixed with politics and remains socially important even though church attendance is falling, and secularization is on the rise (Mitchell, 2005). Religion is a massive part of people’s identity in Northern Ireland even though the practice of religion is declining. It is about maintaining one’s social identity, remaining a part of a specific group.

8. Northern Irish Identity

Now having looked at the factors that have played a role in forming the identity of Northern Ireland, we must look at the research that tells us what shape that identity takes.

27

The previous factors have shown us that there has been a lot of divide in the region, with a lack of understanding between the two communities and that their unwillingness to come together has resulted in conflict. It is important that both communities’ ideals are represented, but what is more important is that they are understood by their opposition and accepted for their differences. It has shown that it is difficult to bridge the gap between these two communities, yet as we’ll see below, the Northern Irish identity is changing, and perhaps for the best.

In the post-agreement society of Northern Ireland, issues of identity and its validity of expression remain gradually relevant (Fenton, 2018). Social Identity Theory tends to be favoured when discussing Northern Irish identity (Garry & McNicholl, 2015). Most analyses of the Northern Irish identity have suggested that it is a new shared identity. It has been argued that the further one lives from conflict suffered areas, the more likely they may consider themselves to be Northern Irish. This means that Northern Irish can be said to be an inclusive identity, overarching both British and Irish sub-groups (Garry & McNicholl, 2015). Leach & Williams (1999) noted that there has always been a level of fear towards one another which has resulted in conflict in the past. Now the region looks ready to move forward. As we previously discussed, Brexit and the 2019 British General Election has given us a great insight into how the citizens of Northern Ireland want to approach their future. The establishment of a nation is no longer a farfetched ideal. It is clear that a return to violence means taking a step back, rehashing claims to one’s identity, when it is clear that both sides would just prolong the eventual understanding that Northern Ireland is becoming an identity in itself.

Historically, Northern Irish identification, national identification in particular, has been seen as a poignant choice often reflecting ideas of ethno-political interpretations articulated inside the confines of a contested society’s borders. Societal pressures have been stated through the vice of exclusive identities, in which one’s choices were instinctively viewed around a level of expectation to communal conformism (Fenton, 2018). Recent research has shown however, that certain groups do not have the same potential as others to be considered Northern Irish. McKeown (2014) argues that people who are more associated with Britishness and Protestantism consider themselves more Northern Irish. It may be hard to reconsider one’s identity when its future remains unclear. Fenton (2018), argues that the GFA and St Andrews, has allowed for a degree of flexibility, allowing for individuals to merge from their traditional identity structures. The

28

continued debate of whether Northern Ireland is Irish or British could potentially start to slow down if there is continued open dialogue between the two communities and less of a division, especially in the classroom setting. There are further positives however, as the data results from Bingham & Duffy (2017) points to more integration between youths in Northern Ireland. Their report showed that between 2007-17, there has been a high increase in the integration of Protestant and Catholic neighborhoods.

Identity can be defined as knowing who you are. With the changing dynamic of Northern Ireland’s social structure taking place. This could mean that there may be a reevaluation of the cultural identity in the region as their next generation may value their nationality differently. People are able to become bicultural over time. It’s about children being raised in these bicultural families, coming into contact with another culture at school and outside the home (Grosjean, 2011). Northern Ireland may be viewed through the lens as both British and Irish right now, yet we could be witnessing a change, altering how we see them. It’s entirely possible that they could become sub-groups in time, although this is currently more of a proposed idea than a rational approach to dealing with Northern Ireland’s divide. It is impossible to know the future of Northern Ireland’s identity, but we are able to evaluate its current position and results tell us that it is becoming its own entity. I value the idea based on the knowledge perceived that holding the position of being either British or Irish, nationalist or unionist, and other factors that oppose one another, simply results in cancelling each other out. There is still a lot of pride in believing in the future of one’s identity, but this can only carry on for so long. As we’ve seen, religion has its importance, yet the region is becoming increasingly secularized, cultures are combining through the use of the classroom setting, both major political parties have support, yet the recent general election has shown an increase in votes for moderate parties. What is left is history, and if history has taught us anything it’s that it repeats itself if forgotten. The region still has a level of instability but as previously discussed it’s evidently suggested that change is slowly but surely being sought out.

9. Conclusion

The paper queried earlier in the paper whether Northern Ireland becoming more British, Irish, or something entirely different? Having done the research, it is clear that Northern Ireland is becoming increasingly British and Irish, while at the same time becoming something entirely different. What is being proposed is that neither background is stepping down as they value the other’s opposition. Keeping cultural traditions alive,

29

supporting the political party that provides care for your social group, and maintaining a good understanding of your group’s past. When it’s said that it is becoming something entirely different, the paper refers back to the political shift that is taking place. Currently, it is not large enough to create major change in the region but perhaps in time we could see Northern Ireland understanding itself more than just being either British or Irish. What role will the UK and the EU play in Northern Ireland’s future? The UK has its work cut out for it in the future when it comes to Northern Ireland. Currently, the region has a population who voted in favour of remaining in the EU and the 2019 British general election saw a nationalist political majority for the first time in its history. Although a large portion of the population declare themselves as part of the UK, it does not make the work of the British government any easier. Expect every major decision that even remotely goes against the ideals of nationalists to be fought over time and time again. This is a good time for the UK to build an ever-closer Anglo-Irish relationship with the ROI as it is currently governed by Fianna Fail who have no intentions of working with Sinn Fein. How important Northern Ireland is to the rest of the UK remains to be seen but with Scotland’s First Minister and Scottish National Party’s Nicola Sturgeon reiterating the idea of another independence referendum, the UK looks under threat of falling apart if it doesn’t maintain good relations.

The EU has a lot to do as well when it comes to catering the UK and Northern Ireland. Since Brexit passed back in 2016, a lot has been done to come to a workable relationship with the first member state to leave the EU. This has been made difficult by the pressing issue of Northern Ireland’s border. We’ve previously discussed the issue, but we have not spoken about the role the EU will play in the future. It is treating this entire process with careful management so as to not deter other members away down the line. The EU’s relationship with the ROI is key to maintaining a strong hold on the issue of Northern Ireland. Neither the EU nor the UK would like to see a return to violence in the region so perhaps the EU will allow for any issues in Northern Ireland to remain internal. Having said that, the EU is for globalization while the UK voted against this ideology and so Northern Ireland may become a battleground for different ideologies to face off, although this remains to be seen.

This thesis was focused on exploring the Northern Irish identity from various different perspectives, using politics, culture, religion, and history as the main points of interest to

30

help answer the overall theme of the paper. While arriving at a conclusion, we included several probing questions which allowed us to understand the paper’s overall goal. Over the course of writing this thesis, a lot of research has examined the conflict in Northern Ireland, as well as how the various factors contributing to the region’s identity has been brought on by the long and tumultuous history between Ireland and England. As of now, we have covered a large volume of research which focused on the future of Northern Ireland, primarily its identity. An overlapping variable of this thesis is the future potential of these two cultures coming together and sharing the region equally.

So, what are the results of this research, what does it tell us about the identity of Northern Ireland? There are certainly a lot of proposed ideas of how it may look in the future, yet the identity of the region can still be easily considered one or the other because of their various roots. There is no recent research into the British general election of 2019 and how this impacts the Northern Irish identity. What has made this research interesting is the fact that the data collected by previous researchers was primarily focused on what Northern Ireland had become after the GFA. What the paper is pointing to is the realization that there will be further data collected in order to examine the region better because it’s continuously shifting. The results of this paper can’t tell us a number of things, just leaving us with a level of speculation. For one, the results here cannot give a clear and concise answer as to what exactly Northern Ireland’s identity is. The thesis was limited by the use of previous collected data, which was an issue brought up earlier in the methodology section. It’s understood that more recent data is required in order to offer a more well-rounded answer to this paper’s research problem.

Going into the paper as the author, biased assumptions were made, thinking that it would be possible to conclude that Northern Ireland’s identity was indeed Irish. The thesis was not to approve of this assumption but rather, the desire to understand the region’s situation more. Throughout the course of the paper, analyzing different data, the paper looked at finding various trends, assuming it would be easy to approve of earlier assumptions, yet this was wrong. Previous research on this matter was rather varied and although the focus was to gather recent research, there were a lot of gaps to be filled. So, going about answering the presented research problem did have its shortcomings. It was also difficult to think in a different mindset, meaning that the paper required a readjustment to how it wrote out its train of thought in order to examine various aspects of this study in another way. This was done so as to not present the work in a biased manner. There had been a

31

specific plan in place for a survey for this paper’s research, which would have been carried out in Northern Ireland but this was not possible and thus, it altered the approach of this thesis. Having said that, this is a confident paper which has explored the most relatable works to this topic in the best way possible, examining it from both sides.

9.1 Future Research

There is a lot of potential future research that can come from this thesis. For one, the paper would have liked to carry out the previously mentioned survey, which looks at asking simple questions about Northern Irish identity, while relating them to the 2019 general election results. Secondly, it is the belief that this thesis acts as a starting point for those who want to grasp the basic understanding of what alters the Northern Irish identity. It would be interesting to explore more factors that contribute to the region’s identity, such as language, the economy, and daily commuting. Although the Irish language of Gaelic is no longer commonly used by a large majority of the region’s population, it is a massive part of Irish culture. It would be of interest to link the language to the rest of the country and see if it offers a shared identity with the people of the island of Ireland. For the economy, it’s such an important factor for maintaining what is already there. Looking into how internal government funding works as well as the EU’s funding of the ROI and how it effects Northern Ireland. Finally, looking at daily commuting could make for an interesting study. The maintenance of an open border is important to a lot of people on either side of the Irish border and they commute for work, school, and leisure. It would be fascinating to examine how a closed border might affect this often-overlooked aspect of daily life.

It would have been worth carrying out further research on the relationship between Northern Ireland and the ROI from a political point of view. Recent Irish elections have seen a sharp increase in the number of seats held by Sinn Fein in Irish government, leading them most recently to becoming the biggest opposition party. With Sinn Fein making political gains both north and south of the island of Ireland, it would be interesting to examine how Ireland’s biggest nationalist party forges their relationship between north and south. For me, Sinn Fein always have an interesting approach to their politics so it could be worth examining this relationship over time.

32

As briefly mentioned in the conclusion, the idea that Northern Ireland could become a battleground for EU and UK ideological approaches to the future of Europe. This would make for some very interesting in-depth research over time. If Northern Ireland maintains an open border with the EU then I believe this type of research is entirely possible. Had this thesis been done once again, it could have explored the idea of national identity more. This leaves room for future research. The reason it is so interesting and worthy of writing about is because of the region’s history. The growth of nationalism in the 19th

century saw the idea of one’s identity come in fruition. It was enjoyable writing about the historical background for this thesis and so it’s clear that future theses of mine would be able to discover more on the topic because of this deepened interest.