Joseph Jenkinson Degree Project, 2018-19 Revised Submission – Cover Letter Post-feedback outline of the main changes made to Joseph Jenkinson’s Degree Project: Silent Voices of Ebola 17 March 2019 To Whom It May Concern, The feedback received after the first submission was very much appreciated and I believe has led to the strengthening of the manuscript. For this I am very grateful for all comments received.

There are two key changes that have been made. The first relates to clarifying the intention of the research project in regards to theories of art as a tool for social justice. The project’s intention was focussed on recording local voices and perspectives as opposed to directly seeking change, which seemed beyond scope given limited resources. However, once produced, the artworks clearly showed qualities that would render them useful for such ambitions and as such a distinction has been made between the role of art as used in this project and the future role of the artworks as they might be applied to the intended extension of the project. I have clarified this in the Research Design section (p.13) made further comments on this in the Conclusion and noted the intention of extending the project where I talk about the exhibition in the methodology.

The second key change relates to the role of captions and titles. The visual data takes precedent in this study and displaying the artworks with their captions and titles (and indeed referring to them as ‘thick descriptions’) on reflection seemed to disguise the distinction between the primary use of the visual data and the secondary supporting use of the discursive data. To rectify this I decided to drop the reference to ‘thick descriptions’ and further clarify the distinctions between the primary (visual) and secondary (discursive) datasets instead. This is clearly outlined in the Method section (p.28) and footnote no.27. I believe this has strengthened the manuscript. The following list outlines the other changes made. Other less significant changes not listed mainly relate to rewording to reduce length. • Abstract – rewording as advised for extra clarity in certain areas

• Research Design – in addition to changes outlined above, the section now states how the project came about, the role of the Academy and how participants were selected/their interest in art and how 55 artworks were made from 32 participants.

• Literature Review – Some shortening has taken place where advised.

Joseph Jenkinson Degree Project, 2018-19 Revised Submission – Cover Letter • Theoretical Framing – W.E.B Du Bois is now cited and referenced correctly and is drawn on slightly further (also in the analysis). I think his concept of the veil and idea of relational seeing of the self is very relevant here. I have also inserted a reference to Bhabha on mimicry which is also picked up on in the Analysis. I have added more information on occularcentrism in West Africa (re: sodalities and role of masquerades in traditional culture).

• Methodology – clarification of who did what. Explanation of the role of captions and titles. Exhibition section extended by moving and re-wording section previously in the Appendix into the main body of thesis.

• Credibility Self-assessment – rewording to emphasise that the self-assessment was relevant to arts-based inquiry and the artworks’ role as texts in relation to me as the researcher (as opposed to arts role in seeking social justice which relates more to future aspirations).

• Analysis – some tweaking of language has hopefully provided extra clarity around Du Bois, Bhabha and Tufte in the analysis section. A note is made in footnote 39 about the Ebola hotline campaign in Sierra Leone following a discussion I attended in Geneva given its close comparison to the analysis of the Call 4455 campaign.

• Conclusion – the first paragraph has been extended to elaborate on ideas for extending the project through exhibitions. This follows from the earlier discussion on this in the Research Design section and the fact that the public exhibition didn’t take place (now included in the Methodology section). The other sections where rewording was recommended have been taken into account and hopefully the conclusion now reads more coherently and clearly. ‘6’ is the author’s chosen surname, I believe.

• References – the additional references of Bhabha, W.E.B. Du Bois and Phillips et al. have been added to the reference list.

• Appendix – the artworks are now two to a page unless portrait where they have been included on their own. Titles, captions and artwork details have been condensed and come afterwards in their own table where they have been listed by artwork number. This has dramatically reduced the size of the appendix and emphasised the fact that the visual art holds primary position over the artwork titles and captions. The manuscript submitted remains within the word count (inc. +10% margin) at 14,151 words. With many thanks once again to those who provided such useful feedback. Yours faithfully, Joseph Jenkinson

Silent Voices of Ebola

The social impact of communication interventions and

response aesthetics during the 2014-16 Ebola

epidemic in Liberia told through the visual artworks of

Liberian youth

Joseph L.T. Jenkinson

Communication for Development One-year master 15 Credits Autumn Semester, 2018 Supervisor: Bojana RomicABSTRACT

In recognition of the scarcity of West African voices in the literature on the 2014-16 Ebola epidemic, this study employs participatory visual art at the core of a multi-method approach to explore how the phenomenon of Ebola was perceived and experienced by young Liberians. Thirty-two participants were selected by the Liberia Visual Arts Academy (collaborating partner) and produced a total of fifty-five artworks. Participant representations of Ebola communication interventions emerged unprompted affording insight into a component of Ebola response that has received criticism. As ‘texts’ the artworks offer local perspectives from which the impacts of communication interventions on society are considered, leading to suggestions for improving practice in emergency health communication. This study differs from the majority of existing studies on local perspectives of Ebola in its primary reliance on iconic signs for inferring meaning (as opposed to indexical signs). Interviews were conducted with participants and many wrote titles and captions for their artworks. These secondary layers of data allowed for cross-referencing and verifying of visual encoding processes. This study shows how risk and behaviour change communication campaigns created a discourse which stratified society towards individualism and suspicion of each other and institutions. The Ebola hotline (‘Call 4455’) appears particularly significant in its association with behaviours of surveillance and mistrust. Such interventions may also have had influence on how people sought to care for the sick. This is considered in relation to infectious risk. The artworks illustrate local perceptions of the social and emotional quality in moments of institution–public interaction. Analysis suggests that the aesthetic qualities of responding institutions appear linked to how people interpreted the ethical nature of institutions and their actions. This study identifies a discrepancy between emergency health communication objectives and the deeper, differing concerns of the public. Sensitive consideration of response aesthetics (aesthetic sensitivity) is offered as a vehicle for innovating locally relevant approaches for socially complex, globalised, mediatised environments in which disease outbreaks occur today.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am particularly grateful for the time and talent of the participants who took part in this research and their willingness to share their experiences with me. This project would not have materialised without the support and guidance of Leslie Lumeh and Frank Dwuye of the Liberia Visual Arts Academy, to whom I’m very grateful. I want express my gratitude to Malmö University for providing me with the opportunity of a post-graduate education, which I could not have afforded otherwise and which will be essential as I prepare for my next career move. Despite the distance learning, my experience at Malmö has been deeply nourishing, both personally and professionally. Finally, I’d like to thank my tutor Bojana Romic for her invaluable advice and, before all, my wife for her enduring faith, patience and encouragement.

A NOTE TO THE READER

This research refers to visual artworks made by research participants during the project. All 55 of the artworks are recorded in the Appendix. Each has a unique ID number i.e. #1. References to individual artworks are made throughout this text to reinforce a point or to illustrate it with a key example. This is done by including the artwork number in parentheses next to the point being made i.e. (#1).

CONTENTS Research Setting p.5 Overview p.6 Limitations p.9 Research Design p.11 Literature Review p.14 Theoretical Framing p.20 Methodology p.27 Credibility Self-Assessment p.30 Analysis p.34 Conclusion p.54 References p.59 Appendix

Visual encoding process p.70

Methodological rigour p.71

Self-critical reflexivity p.72

Artworks p.73

RESEARCH SETTING

Liberia is Africa’s oldest republic (est.1847) and was formed by ‘freed slaves and freeborn black Americans’ (NIC, 2016), who, according to ex-President Sirleaf ‘[planted] their feet in Africa but [kept] their faces turned squarely toward the United States’, resulting in a history of difficult relations with indigenous populations (Sirleaf, 2009, p.6). Social relations in the vibrant Mano River Region1 span tribes and national borders, where flows of just about everything have been facilitated for centuries by informal networks that span the fluvial landscape (Sirleaf, 2009; Siberfein and Conteh, 2006). Talking of ‘Liberian culture’ obscures the more interesting reality that cultural characteristics (including artistic styles) can be found in similar forms throughout the region but can also differ dramatically, including within Liberia’s own borders.

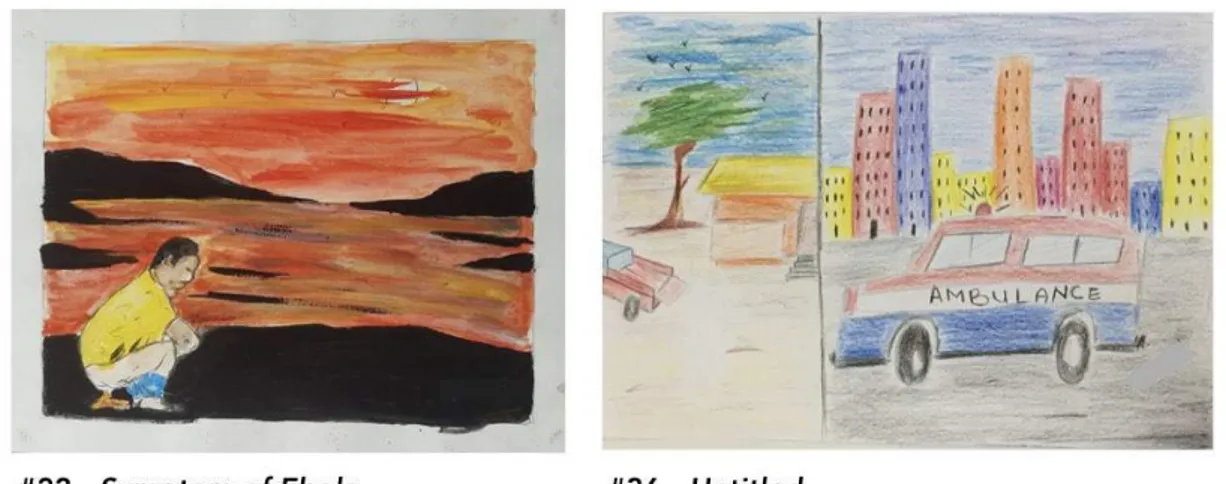

Oosterhoff and Wilkinson (2015, p.3) describe how ‘[f]rom slavery to post-colonial and post-war development, international extraction and local exploitation has set the tone…, allowing a few to benefit at the expense of others’. Liberia’s civil wars (1989-1996 and 1999-Aug 2003) left considerable trauma on the population and devastated the country’s health capacity, exacerbating issues of Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) when Ebola arrived in April 2014 (Abramowitz, 2014). Omidian et al. (2014) cite how the government-declared state of emergency and messaging on Ebola reignited post-conflict traumas and the re-embodiment of ‘survival’ behaviours. A violently graphic visual display on Ebola at the National Museum in Monrovia sits next to graphic accounts of war. As national representations they suggest a similarity in the way these events are understood – collective traumas that are deeply visual and overrun one another. An account of Liberian masks by Bordogna (1989, p.98) reads: ‘The grotesque masks, incorporating such elements as clay, blood, animal teeth… presented a challenging aesthetic. Violating our sense of decorum and balance, they thrust us into a maelstrom of violent and awesome spirits’. If this violence and drama is representative of local arts culture it might help to explain participants’ engagement on the emotional and sometimes-gruesome realities of the Ebola outbreak of which they were unfortunate enough to bear witness.

OVERVIEW

The Research Problem

According to Oosterhoff and Wilkinson (2015, p.3), ‘Local knowledge and perspectives on containing Ebola – and other disease outbreaks – must be at the heart of the public health and biomedical responses’. This claim receives wide support in the literature on the West Africa Ebola crisis of 2014-16 reviewed herein, with particular implication for the communication and community engagement aspects of the response (Minor Peters 2014; Chandler et al. 2015; Laverack and Manoncourt, 2015; Richards, 2016; Figueroa, 2017; Graham et al. 2018). A 2015 report on the impact of Ebola on children in Liberia concluded that ‘…the value of structured dialogue to give voice to those affected at grassroots level cannot be underscored enough’ (Rothe et al., 2015, p.16). Despite an extensive body of evidence supporting these recommendations, local voices2 from West Africa remain vastly underrepresented in the literature, and where they are recorded they are typically reduced to no more than a few lines of text. This raises questions about what might have been lost in terms of local knowledge and perspectives through the processes of representation adopted by researchers and the presentation of their results. The global record on the West Africa Ebola epidemic is weaker for this (Leach and MacGregor, 2019); the perspectives of those with the most personal experiences of the disease, and the knowledge with which it is associated, have been marginalised. This problem, of a lack of authentic3 local voice in the literature on Ebola, may have been exacerbated by a lack of methodological diversity in the relatively few studies that strive to record local knowledge and perspectives more accurately. As such, the problem also inspires a methodological investigation in response to Robert Chambers’ question: ‘Can we know better?’ (Chambers, 2017).

2 Whilst Nick Couldry’s concept of voice as a value fits the overarching trajectory of this research, it is

Couldry’s description of the political voice (2010, p.11) that I take as my definition here: ‘Voice’ as ‘the expression of opinion or, more broadly, the expression of a distinctive perspective on the world that needs to be acknowledged’ given its close alignment with the wider issues of representation discussed in this research, the visual connotations afforded through the concept of ‘perspective’, and Couldry’s linking of this to the process of acquiring and need for recognising knowledge (‘needs to be acknowledged’). My interpretation of Couldry’s definition therefore conceptualises ‘voice’ as representation that is co-constitutive of perspective and knowledge, and conceptualises local voice as voice emanating from a specific geographic locale (which in present context typically means ‘Liberian voice(s)’.

3 ‘Authenticity’ is not used here to describe something as being unquestionably evident but is taken to

mean voices or representations where conscious, reflexive efforts have been taken in their (re-)presentation to strive to limit their manipulation, whilst recognising that the audience/viewer/receiver will always bring their own interpretations and subjectivities to the process of meaning making.

An issue of global importance

Writing in the World Health Organisation (WHO) Bulletin, Fan et al. (2018, p.130) state that whilst the 2014–2016 Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreak in West Africa led to about 11,300 deaths (4,809 of which were from Liberia, the worst hit country in terms of number of deaths), ‘the death toll from a severe influenza pandemic might be 2,500 times higher than this’. It is commonly understood that the probability of the next major pandemic occurring in our lifetimes is significant (Gates, 2018). The threat of pandemics will remain relevant, not least as processes of globalisation create pathways for disease transmission (Lee and Dodgeson, 2000; Mondragon, Gil de Montes and Valencia, 2017). Leach and MacGregor (2019, unpaged) note that ‘…a gap remains, both in policy and in academic literature, namely attention to the perspectives of people in places envisaged as “hotspots” for outbreaks’ and requires ‘critical scrutiny’.

The relevance of the research problem to Communication for Development (C4D)

The World Health Organisation considers communication and community engagement as a central pillar in the fight against infectious diseases (WHO Managing Epidemics, 2018). There is no recognised standardised approach by institutions working in this field. Instead, combinations of Health Communication4, Risk Communication5 (preferred by WHO), and Social Mobilisation6 (all three of which UNICEF bracket under their preferred term ‘Communication for Development’) tend to provide the typical theoretical frameworks for strategic approaches to communicating and engaging with populations deemed to be ‘at risk’. These approaches have traditionally been grounded in concepts of persuasion-based Behaviour Change Communication (BCC) (explored by Berry, 2007, p.35-8), which Waisbord (2001) would include under the top-down diffusion branch of the development communication (devcom) ‘family tree’ and

4 Defined by Berry (2007, p.2) ‘as referring to “any type of communication whose content is concerned

with health” (Rogers, 1996, p.15), where the focus is on health-related transactions and the factors that influence these’.

5 The most recent Ebola specific definition provided by WHO reads: ‘Risk communication in the context

of an Ebola outbreak refers to real time exchange of information, opinion and advice between frontline responders and people who are faced with the threat of Ebola to their survival, health, economic or social wellbeing’ (RCCE Framework, 2018, p.3)

6 UNICEF (2015) definition: ‘…a process that engages and motivates a wide range of partners and allies

at national and local levels to raise awareness of and demand for a particular development objective through dialogue…[that] seeks to facilitate change through a range of players engaged in interrelated and complementary efforts.

the modernisation theories of development, she describes. According to Gillespie et al. (2016), the West Africa Ebola epidemic was the first time ‘Communication for Development (C4D)’7 was formerly incorporated into national emergency response

plans. Criticism of communication campaigns employed during the outbreak has led to extensive research on how communication interventions during disease outbreaks might be improved in the future. The relevance of C4D is becoming increasingly evident to theories of emergency health communication. Many suggestions point to the need for more participatory approaches to communication from the bottom-up and that these be either incorporated alongside, or used instead of, traditional approaches that favour top-down, diffusion models (embodying Waisbord’s 2001 ‘split’ in the devcom family tree); C4D specialists should seek solutions but must remain self-critical and reflexive. This study contributes to the field by applying participatory visual methods to investigating not the success of C4D interventions but the possible social impacts they may have had, as understood locally. From a theory of change perspective, the philosophical basis of the project assumes that greater authentic representation of local voices gathered through a diverse range of methods and presented critically and reflexively will afford their consideration as valued sites of local knowledge that will support the development of improved practices in communication and community engagement, that ultimately keep people better protected from communicable diseases8.

Research questions

1. RQ-1: What do visual representations by Liberian youth on the topic of Ebola tell us about the social impact of the communication interventions carried out during the 2014-16 Ebola outbreak in Liberia?

2. RQ-2: What insight for improving the design and application of communication interventions during health emergencies in the future is afforded by the local perspectives recorded by participants?

7 Described by UNICEF in Gillespie et al. (2016, p.628) as: ‘C4D is a 2-way process for sharing ideas

and knowledge, including social norms, using a range of communication tools and other approaches that empower individuals and communities to change behaviour and take actions to improve their lives’.

8 It is not the goal of the research project to achieve this within the timeframe and limited resources

available, however the research provides a foundation from which such ambition might be pursued through further extensions. The statement of a theory of change is intended to offer transparency on this. (See also final paragraph of ‘Research Design’ section on possible extension.)

LIMITATIONS

The project applies a participatory visual arts-based method working with Liberian youth through the Liberia Visual Arts Academy (livarts.org) on their experiences of Ebola. The most damning limitation of this research in my mind is the constraints of time that led to an inability to discuss and co-create with participants the presentation of the results. This seems to run counter to everything I have set out to achieve. I have given extra attention to reflexivity as an attempt to account for this and hope I am forgiven for the exceedingly long (but I believe exceedingly valuable) appendix, which I felt obligated to devote to the presentation of all 55 pieces of artwork, in lieu of a consultation with participants on my ‘outsider’ analyses of their material. The validity of my findings would surely have been improved if a more participatory process was taken from the start, however time constraints made this unfeasible. I was tempted to refer to the participants as co-researchers, however this would have suggested participation in the decisions and processes of research design and delivery, which did not occur. Participation in the process of data encoding (tagging of the artworks) would have been particularly beneficial. Similarly, a focus group discussion at the end where I could inquire whether my analyses accurately reflects the collective views of the group would have allowed a chance for calibration and accuracy. I discuss my considerations of these factors in more detail throughout and the steps taken to mitigate.

I applied a systematic process for gathering material to inform the study, however the scope of material on Ebola is huge and rapidly evolving and new studies continue to emerge, which may not have been identified. The study assumes that the authenticity of local voices has been negatively effected by processes of recording and presenting/(re-)representing and that this has resulted in deficiencies of local perspective and knowledge within the wider record on the Ebola crisis. The research also assumes that less top-down approaches of working and communicating with communities during communicable disease outbreaks can coexist with effective disease management, prevention and control and recognises that this is a complex issue for institutions to address, not least in situations such as the Ebola outbreak (at time of writing) in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), which is unfolding in a conflict zone – not all lessons from the West Africa outbreak will apply to all contexts. Finally the research

assumes that there is political appetite by academics, health institutions and governments for working with a plurality of knowledge, recognising that genuine partnerships with communities will require an acceptance of local knowledge and perspectives alongside biomedical knowledge (Oosterhoff and Wilkinson 2015).

A note on gender imbalance

For a project that aimed to capture local voices and representation, it is ironic that a large contingent from a local girl’s school were denied participation in the project the day before the workshop got underway, skewing the gender balance of the group unexpectedly and in dramatic ways. At face value, Spivak might have been right to conclude that the ‘subaltern’ (as female) cannot speak (Spivak, 1988, p.104). However, my own reflections on the moral dilemma of ranking the competing values of participation in the research versus participation in school from the point of view of the participant, might offer a (perhaps overly hopeful) alternative reading which suggests that whilst girls may have lost a ‘sprint’ in the race for female voice and representation through their underrepresentation in the research project, they might still win the ‘marathon’, thanks to the support of an apparently determined teacher who chose to act to prioritise their school-based education.

RESEARCH DESIGN

Having identified that participatory visual art would provide an alternative approach for looking at Ebola ‘from below’ a brief search online identified the Liberia Visual Arts Academy (LivArts) as a potential partner. I made contact with its Director and over a series of exchanges we designed the programme and agreed a simple Memorandum of Understanding. LivArts was responsible for selecting participants given its existing links with schools in Monrovia from which students come to the Academy to participate in the extracurricular art activities. Other young adults known to the Academy who had a passion for the arts were also invited. Thirty-two young Liberians9, acting as research participants, created 55 pieces of visual art10 on the topic: ‘Your experiences and memories of Ebola’. The outcome is a unique perspective and record on the Ebola outbreak and response in Liberia. Analysis reveals local knowledge and perspectives from which suggestions are made for how communication and community engagement approaches might be improved in the future.

The instruction given to the participants (artists) was kept deliberately broad in order to limit researcher influence on the creative process. As far as was possible within the constraints of the study, participants were offered the maximum opportunity for freedom of expression, with the theoretical aim that they should only be restricted by the limits of the art materials provided (drawing and painting materials), time allocated (two-day workshop) and their imaginations. This helped to establish a more horizontal relationship between the researcher and participants.

Importantly, and without prompt, the artworks illustrate the strong visual memory of the health communication messages and campaigns that were employed during the response and the impact they had on people, as experienced ‘from below’. As such, they also provide unforeseen retrospective opportunities for evaluation of the communication interventions employed in Liberia. Unique visualisations of the complexity of the social, economic and political landscapes as they were/are seen and experienced by

9 The majority of participants had attended previous art classes at the Academy where they received some

instruction in simple drawing skills. For a small group of others, this was their first engagement with the Academy. All classes by the Academy are extracurricular suggesting it attracts people who have an interest for the arts.

participants, and how these interplayed with the communication campaigns of the outbreak, emerge. As evaluative tools, the artworks reach beyond, behind and in-between the lines of ‘indicators’ typically employed in evaluating health communication campaigns, helping to remove what Chambers (2017) has referred to as ‘blind spots’. Through the artworks, local interpretations of the wider social impact and implications that health communication campaigns had can literally be seen.

The artworks suggest the need for more holistic approaches to emergency health communication that go beyond messaging and support the performance of behaviours and the acquisition of embodied skill (as advocated for by Richards 2016). The risk discourse emanating from ‘risk communication’ is also critiqued. The artworks appear to support post-Crisis attempts to demystify Ebola response (such as through making treatment centres and body bags transparent, discussed by Spinney, 2019) but go further in suggesting that the entire response system and infrastructure should be understood as a powerful form of aesthetic communication. This concept leads to an imagination of alternative approaches to communication during health emergencies that consider the importance of aesthetic sensitivity.

Whilst in the first instance the artworks provide a valuable source for the present research project, participants described the artworks’ secondary value as an important social record:

“…art is important…because it serves as a reminder and you see it and you think about the time it happened. Time comes and goes, but it will always be there. People are going to see it and they’re going to ask, who did this or what message does it give? Immediately if you see it, you know the message.”

Research participant (interview) “… everyone never had the knowledge of Ebola…[but now] I believe that everybody has learned…here in Liberia, we just need to continue to remind people…We lost a whole lot of people from Ebola. It was a war. We’re talking about war crimes and prosecuting people. Ebola is not somebody you can prosecute, so the awareness is as important as prosecuting somebody for the crime they did, it’s very important. The awareness is important, very important.” Research participant (interview)

The artworks harbour powerful yet silent local voices on Ebola creating an irony and theatrical immediacy of the sort that has been shown to help in communicating knowledge (Quinn and Bedworth, 1987). As such, building on Chouliaraki’s (2013) concept that a theatricality in humanitarian communication can help build solidarity, an additional contribution of the artworks might lie in their potential for bringing local voices into dialogue with institutions and decision makers, who must continue striving to translate lessons from the West Africa Ebola crisis into improved praxis.

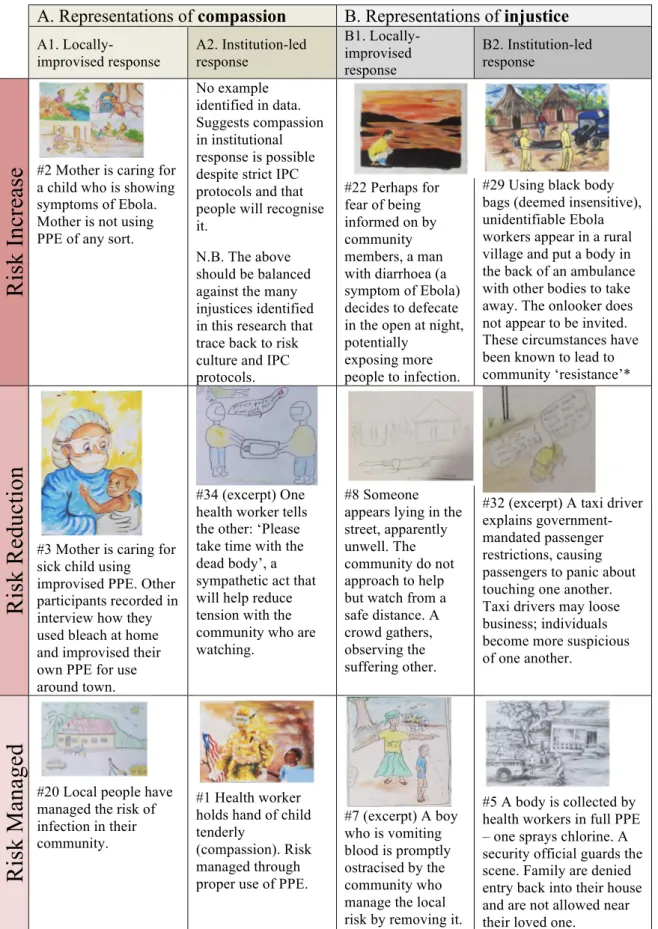

A clear distinction must be made between the intentions of the research as it was undertaken and any possible future intentions regarding an extension to the project. Arts based research was employed here with the expressed intention of exploring and recording local perspectives and memories on Ebola and participants produced their artworks on this understanding. The plan for a public-facing exhibition was designed to help validate local perspectives rather than seek social justice, which seemed an untenable aspiration given limited resources11. However, once the artworks were produced, it became apparent that many offer the sort of deep social commentary that Barone and Eisner (2011, p.123) describe as challenging habits and practices of the status quo that have been ‘taken for granted’. Therefore, whilst the questions and fresh perspectives that the artworks provide were unintended they are possibly all the more powerful for this and I believe they are highly valuable for the challenge and opportunity they present to those striving to improve Ebola response. It is my hope that institutions such as WHO see the value in the plurality of alternative perspectives the artworks offer. As an extension to the project, my intention is to explore with participants the value they see in sharing the artworks more widely. This may lead to more of an advocacy agenda but the artworks will retain their plurality of perspectives. Considered alongside existing narratives, there does seem to be an untapped potential in the artworks that could help promote the development of improved practice in Ebola response so that it is more sensitive to local contexts.

11 Barone and Eisner (2011) highlight how some arts based research projects that seek social justice can

be interpreted as propagandist, or presenting their own narrative as superior to other narratives or

perspectives. This research, as undertaken, did not harbour such intentions. Instruction to participants was minimal and deliberately broad so as to limit my own influence over outcomes, allowing participants to interpret Ebola at will. Participant representations in the collective do not appear to wholly subscribe to any single narrative and where the institutional response is depicted in a positive or compassionate light I have also made concerted efforts to highlight these instances in the analysis (see section on ‘Ebola People’, Table 5 and Figure 12 for examples).

LITERATURE REVIEW

Process

A systematic search of the academic and grey literature and media was conducted using the LibSearch catalogue of Malmö University library and Google, structured around key terms. Articles were saved and tagged, resulting in 610 unique tags. Directly relevant tags not previously searched for became new search terms, expanding the scope of literature uncovered. Reference lists helped identify additional resources. The process was repeated using Google Scholar. Additional searches were carried out on websites of key journals (e.g. Journal of Health Communication) and on media platforms such as YouTube (where notes were taken from relevant documentaries). Searches were concluded when returns became consistently less relevant. Another important resource has been my exposure to and observation of the work of the WHO at headquarters, as a UK government representative to the organisation for DFID, where I focussed on health emergencies (including working on three Ebola outbreaks in the DRC). Insights from the institutional headquarters perspective peaked my interest in exploring Ebola ‘from below’. It also emphasised the need for me to be self-reflexive. The literature on Ebola is vast. The following review considers only those resources deemed directly relevant. It prioritises Liberia. It has been subdivided into themes to contextualise the research problem and to highlight how this project strives to make a unique contribution.

Communication and the relevancy of local perspectives and knowledge

The World Health Organisation (WHO), as global institutional lead, received widespread criticism for its failure to respond quickly and effectively in the West Africa Ebola epidemic (Kelland, 2015; Kamradt-Scott, 2016). Communication and community engagement components of the response received scrutiny and criticism, particularly in the outbreak’s early stages (Chandler et al. 2015; Richards, 2016; Figueroa, 2017; Hofman and Au, 2017; Walsh and Johnson, 2018) with implications extending beyond WHO to the wider cohort of institutional ‘leaders’ in the response12. Criticisms of communication interventions were wide-ranging, varying across time (during and after the epidemic) and place (both across Liberia and other affected countries) but are characterised by a failure to properly listen and engage communities in meaningful

12 Including other health agencies, the United Nations, the national governments of affected countries

ways (Gillespie et al. 2016; HC3, 2017) and sufficiently consider local perspectives and knowledge (Minor Peters, 2014; Kutalek et al., 2015; Abramowitz, 2017; MacGregor and Grant, 2019). Furthermore, a reliance on behaviour change ‘messaging’ (Richards, 2016) from the ‘top-down’ (Oosterhoff and Wilkinson, 2015; Hird and Linton, 2016; Laverack and Manoncourt, 2016) was not always deemed appropriate for the specificities of local context (Omidian et al. 2014; Kpanake et al. 2016; Wilkinson et al. 2017; Walsh and Johnson, 2018).

Graham et al. (2018) suggest that establishing trust with affected communities might be the most important factor for successful health interventions. During the early stages of the epidemic, insufficient attention to local realities is thought to have contributed to social confusion (Figueroa, 2017; Bonwitt et al. 2018), leading to the proliferation of rumours and exacerbating issues of mistrust in institutions and outsiders (Faye, 2015; Kutalek et al. 2015; Hird and Linton, 2016; Figueroa, 2017). Despite explicitly referencing the importance of trust, recent publications from health institutions (WHO Managing Epidemics, 2018; RCCE Framework, 2018) appear to overlook the possibility that trust is a two-way process and that they may also need to be more entrusting of local communities (pursued by Richards, 2016).

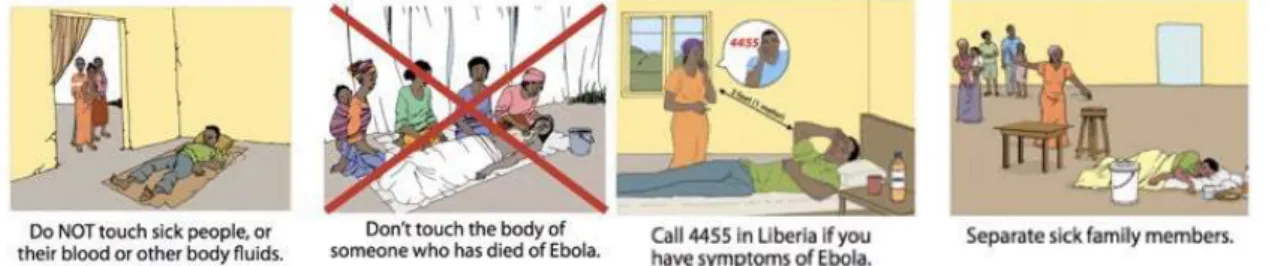

A detailed study of communication-related efforts in Liberia by Figueroa (2017, p.6) notes how delays in communication resulted in ‘a misinformed public; fear and mistrust…’ where ‘even the smallest bits of information about EVD became valuable but insufficient’ to build a communication strategy from. This information void resulted in direction being sought from medical specialists as opposed to social scientists and may explain why many early public health campaigns appeared counterproductive (Gillespie et al. 2017). As Fairhead (2014, p.21) notes in regards to the truth claims of campaigns like ‘Ebola is Real’ (as used in Liberia, see Gillespie et al. 2016, p.642), ‘…this “way of knowing”, is being experienced by communities as a mode of power and for this reason, is not working as well as it might. Ebola is a social phenomenon, not just a virus’. This highlights the value in understanding local perspectives particularly where relationships with institutions and outsiders are closely entwined with power, conflict and colonial history (Benton, 2016). Other examples where inappropriate messaging resulted in confusion, mistrust or inefficacy, included: telling

people to avoid bush meat when they’ve had no problem eating it before (Vice News, 2014; Bonwitt et al. 2018), that ‘Ebola Kills’ prompting responses such as ‘then why go to the clinic?’ (HC3, 2017, p.8), and reactions to messages of ‘no touching’ such as “It will be impossible that my child or husband is sick and I refuse to touch them. I do not have the courage or heart to do that” (quote, Liberian woman, in Abramowitz et al. 2015, p.11). Subsequent efforts that tried to correct misinformation did ‘more harm than good’ (Chandler et al. 2015) as it was seen to subordinate local knowledge to those of outsiders. All these examples and more are visible – and depicted in their social context – within the artworks produced by Liberian youth during this research project, who were afforded the voice to ‘speak’ first hand and in full13.

Jones (2014) describes how anthropology was called upon as a ‘handmaiden to epidemiology’ to help overcome ‘cultural issues’ (often behavioural) seen by responding institutions as sticking points, who considered Ebola more a biomedical concern than a social phenomenon (Chandler et al. 2015). This subordination of knowledge from the social sciences is thought to have obfuscated important contextual layers of social complexity and local perspectives and knowledge (Jones, 2014; Chandler et al. 2015; Leach and MacGregor, 2019) that the literature suggests could improve communication efforts (de Vries et al. 2016), and that appeared to be doing so towards the end of the epidemic (Gillespie et al. 2016; Martineau et al., 2017).

Whilst recognising the important role of communities in bringing the epidemic under control, Wilkinson et al. (2017) suggest that the term ‘community’ is problematic given its use both descriptively and instrumentally14. They propose this led to the oversight of important social complexities, the creation of imaginary landscapes and the imposition of ‘one-size-fits-all’ approaches through which ‘positive and inclusive terms such as “engagement”, “ownership” and “participation” jar[red] with…realities’ (ibid. p.3). This illustrates how shared meanings in supposedly benign concepts (‘community’) may be assumed rather than held in reality, suggesting the need for more critical, reflexive consideration of local understandings. As Wilkinson et al. (2017, p.5) note: ‘The lesson…is not that “communities” can stop epidemics and build trust; it is that

13 See appendix for artworks #32, #46, #40 and #2, which cover these examples respectively. 14 i.e. ‘community-led’ interventions

understanding social dynamics is essential to designing robust interventions’. A theme of ‘Ebola politics’ (particularly in the grey literature, see Hofman and Au, 2017; Walsh and Johnson, 2018) suggests institutions and governments may have been preoccupied with their relations to one another, rather than their collective relation and responsibility to the affected public. Unfortunately, those studies identified that do try to understand ‘from below’ are weakened in the collective by a lack of methodological diversity.

Methods and the creation of ‘biases and blind spots’

Chambers (2017, p.27-8) describes how research-related biases 15 ‘…give an unbalanced, distorted and/or incomplete view of realities’ and blind spots occur when ‘…domains, locations, topics, factors, aspects, dimensions, approaches and/or methods… are systemically not recognized or neglected’ (ibid.). Patterns of research bias relating to method emerge in the Ebola literature, suggesting blind spots may still exist. Choice of method appeared to be the best opportunity for ensuring this study contributed something new and became of key importance to the literature review. The vast majority of academic literature reviewed employed methods grounded in the discursive, which I take to mean those structured around indexical, spoken/written language, with combinations of interview-based approaches (e.g. Omidian et al. 2014; Bonwitt et al. 2018), surveys (e.g. Pronyk et al. 2016; Winters et al. 2018), and focus groups (e.g. Abramowitz et al. 2015; Kutalek et al. 2015; Martín et al. 2016) well represented. The flexibility of these approaches, ease in which they can generate ‘knowledge’ and their cost effectiveness make them highly popular (Cook, 2008; Julien, 2008) and appropriate in emergencies, where speed is of the essence16, or in situations such as Liberia in 2014 where ‘IPC constraints… discouraged community encounters and restricted resources’ (Abramowitz et al. 2017, p.61; see also McLean et al. 2018). However, many of these methods share similar limitations, such as the responsibility put on researchers regarding question design and delivery which can lead to power imbalances that favour researchers over participants (McGinn, 2008, p.768)17.

15 ‘…professional preferences for and tendencies towards behaviours, choices, locations, people,

priorities, topics, qualities, and methods…’ (Chambers, 2017, p.27-8).

16 See Knowledge Attitude Practice (KAP) survey approach in Liberia described by HC3, 2017. 17 See also Brinkmann, (2008); Cook, (2008); Schensul, (2008).

A sit-rep of the Ebola Community Action Platform (ECAP, 2015), a cornerstone of communication efforts targeting 50% of Liberia’s population, shows how survey questions based on knowledge recall generated results such as ‘94.9% of respondents agreed that they would not touch the family member (ibid., p.14) and conclusions such as: ‘94.9% of beneficiaries have adopted “non-touching practices” to protect themselves [from] Ebola’ (ibid.). This assumes correct recall equates to ‘correct’ performance of behaviour (and makes assumptions about motivation). Richards (2016, p.17) refutes the idea that knowledge from health messaging guides behaviour change, instead arguing for Durkheimian theory that accounts for the agency of ‘group action and interaction’ (ibid.). The Sitrep describes how ECAP achieved its goal; however, its approach to measurement ignored social processes and led respondees towards giving ‘convenient’ answers. Shortcuts in the measurement of socially mediated variables (sometimes necessary in emergencies) can obfuscate local knowledge and create blind spots.

The few studies that employed discursively-based methodologies reflexively reported ‘wariness’ amongst participants (Minor Peters, 2014, p.11) and suspicion over how data would be used, leading to refusal to participate in some cases (Bonwitt et at. 2018, p.168). Efforts to strengthen methodologies typically involved triangulation with other methods, however, these tended to be discursively based too (i.e. Abramowitz et al. 2017; McLean et al. 2018) leading to repetition of weaknesses around issues of power and lack of participant control over representation.

When anthropologists became involved in the response in late 2014 (Bolton and Shepler, 2017), so did ethnographic observation, which became applied either as a primary approach (e.g. Martin et al. 2016), or to help validate question-led data (e.g. Omidian et al. 2014). However, the orientation in relation to the Other (Vidal, 1995, in Faye, 2015, para.44) that ethnographic observation involves obscures the emic perspective and presents the moral challenge of participants ‘taking part’ in research without their knowledge18. Nyenswah et al. (2016) offer rare local voices in the academic literature however the authors’ affiliations with the Government of Liberia and WHO suggest it may reflect a view from above rather than below.

18 A study by Abramowitz et al. (2015, p.4) provided a more considered approach in using

The most relevant example that strived to record authentic local voices from a local perspective was that of Kollie et al. (2017) that used a discursive peer-to-peer technique and included lengthy quotes from participants in the presentation. Whilst ‘peer-to-peer’ approaches might enhance the potential for shared understandings, power imbalances may remain. To the authors’ credit, reflexivity on these points was incorporated.

Visual approaches

Studies on Ebola that consider visual data and image tended to explore non-local media environments19, pointing to the vast quantity of visual data in media content, which emerged internationally during and post epidemic. Leach and MacGregor (2019, unpaged) suggest global discourses ‘image’ rural African villages in ‘powerful and particular ways’, leading to local people being ‘viewed as sources of global disease’ and ‘resource[s]’ for communication and community engagement interventions.

Locsin (2002) was the only study identified that employed visual methods to the understanding of local perspectives on Ebola and used an arts-informed approach to understand the experiences of people who may have come in contact with Ebola and were ‘waiting to know’ whether they had contracted the virus. As per my research, Locsin’s (2002) study recognises that ‘[a]esthetic expressions… serve as a way to understand another person’s view or perspective’(ibid. p.124). Locsin applies visual art with discursively derived data (Locsin used questionnaires) creating a mixed method approach, similar to the one I applied and Locsin and I both believe the arts can help express feelings, experiences, emotions and meaning in ways that words cannot. However, Locsin’s study focuses on an Ebola outbreak in Uganda in 2000 and uses existing non-local artworks to help explain experience. Local voices remain in the discursive, captured through interview and presented in anecdotes, constraining local voice and control over representation.

19 See Joffe’s (2008) study of visual representations of Ebola in British newspapers, Mondragon’s et al.

(2017) study on collective representations of Ebola in Spain, and Dionne and Seay’s (2016) study on American perceptions of Africa during the West Africa Ebola outbreak (see also Section III ‘Politics of Ebola’ in Evans, Smith and Majumder’s, 2016 edited book).

THEORETICAL FRAMING

Summary of section

The issue of representation that the research problem and questions concern themselves with is put into context with assistance from Hall, Evans and Nixon (2013) and Michel Foucault (1980). McEwan’s (2009) interpretation of Spivak’s (1988) classic essay provides a theoretical foundation for the issue of representation, which is then built-on through Hamburger’s (1997) argument that occularcentrism might be common to all societies, leading to a brief consideration of the pros and cons of working with visual theory. Drawing and painting are identified as low-tech (and therefore less corruptible from a post-modern view) solutions for working with visual inquiry processes. Barone and Eisner (2011) and Clammer (2014) provide a theoretical framing for working with art in social research. A theory to support the researcher’s spectatorship of art as ‘texts’ is provided by Berger (1972) and Bresler (2006).

Representation and local voice

As Manyozo (2017, p.60) describes in his analysis of Fanon (1965), ‘intellectual, cultural and empirical forms of colonial violence’ result in the transfer of the battlefield in the fight against colonial oppression to control over the ways the oppressed ‘…are seen and represented’. The fight against colonialism turns into a fight for representation and ideological domination, which extends where colonialism hands the baton to orientalism, as Manyozo (2017) suggests. My research brought this vividly to life for me as I reflected on my imaginations about Liberia pre and post field visit. I returned from Liberia with recognition that the country and its people had been misrepresented to me through stereotypes of war and disease, presumably via the media and literature I had consumed. I had created an imagination of Liberia, evidenced in the Barthesian mythologies I had subscribed to: ‘Liberia’ and ‘Monrovia’ had signified ‘AK47s’, ‘war’, ‘violence’, ‘Ebola’ but now signified ‘vibrancy’, ‘music’, ‘beach’, ‘culture’, ‘poverty’ and still ‘Ebola’, albeit from a different perspective. This reflection illustrated the systems of representation in process (Hall et al. 2013) and reveals how both iconic and indexical signs are closely entwined. Furthermore, the example illustrates the theoretical displacement of the subject (Liberia/Liberians; Monrovia/Monrovians) through the semiotic process (Hall, 2013), leading to the imposition of representation of

the Other through discourse (Foucault, 1980). Through an inability to control their own ‘narrative resources’ (Couldry, 2010, p.18), the Other had been ‘spoken for’, rendering them mute. Foucault’s shifting of focus ‘…from “language” to “discourse”…’ as a system of representation (Hall, 2013, p.29) provides importance to the consideration of the power imbalances at play in this process. A process aimed at recording authentic local voices facilitated and interpreted by me as an English, white male outsider, will take place within existing frameworks of power between outsider and locals, will create new imbalances of its own i.e. researcher/researched, and might well engender orientations in relation to my nation’s record of colonial exploitation in West Africa. However, one might argue that any approach taken to tackle the problem of a scarcity of local voices will do the same as, through presentation of the results, voices enter into an existing discourse of which they have no control and from which readers will orient themselves in relation to the Other (the concept of ‘subject positions’ Hall, 2013, p.40). It is this conundrum that led Spivak to conclude that the ‘subaltern’ cannot speak (1988, p.104), or in the visual sense, as described from the emic perspective by Du Bois (1903, p.3), of a “veil”, which amongst other affects, obscures the subaltern’s view of itself so they are ‘…always looking at oneself through the eyes of others’. This suggests claims of self-representation might be illusory (Manyozo, 2017). As such, Bhabha’s (1984) idea of “mimicry” might be a useful concept for interpreting outside influence on local voices/representations. Furthermore, any presentation of local voice will not necessarily mean that research-related power imbalances have been overcome and I recognise these imbalances are also weaknesses of those discursive methodologies I have critiqued. Spivak provides some assistance in the idea of ‘unlearning one’s privilege as one’s loss’ (McEwan, 2009, p.68), and the understanding that ‘our relative privileges have given us a limited knowledge, but have [also] prevented us from gaining other knowledge, which we are not equipped to understand’20. McEwan (2009, p.68) explains how the only way to move beyond this is to ‘learn to learn anew’ (ibid.). In so doing, an ‘ethical relationship with the other’ is formed through which new spaces are opened, where ‘others can have a voice and…be taken seriously’ (ibid.). This would seem to be a necessary precursor for creating more locally relevant communication interventions for

20 A case study is provided in Chandler’s et al. (2015) article on biomedicine’s disregard of local

Ebola outbreaks. A methodology that applies an alternative mode of inquiry to those in the literature will necessitate ‘learning anew’ and might offer solutions. Whilst I have my own biases and privileges to unlearn, I have other freedoms such as independence from research grants and a non-professional relationship with my institution, which afford me flexibility to explore where such new spaces might be uncovered.

A more ‘inclusive’ understanding of language (Hall, 2013, p.18) help to identify the arts (see Leavy, 2015) or popular culture (see Rivera, 2017; Stone, 2017, both on popular music in Liberia during the outbreak), and the ‘ethical relationship with the other’ (McEwan, 2009, p.68) points to the relevance of participatory methodologies, which can help to address social inequalities and power structures, including those between the researcher and participants (Davis, 2008; Jordan, 2008). This led to the identification of participatory visual arts as a potential solution, which would allow for the production of voices by local participants through the creation of visual representations where participants as artists retain full creative control. Given the apparent scarcity of literature that apply visual methodologies to the study of Ebola ‘from below’, this approach would also help in illuminating blind spots.21

The opportunities and challenges of the visual

Visual methodologies emerged following theories of ‘occularcentrism’ (the centrality of the visual in knowledge acquisition), which was suggested to be a characteristic of modern Western societies (Jay, 1993). However, it has been argued that occularcentrism is a common condition of societies across time and space (Hamburger, 1997). As such, local knowledge in Liberia might well be intricately entwined in the visual. Indeed, certain masquerades in the Sande (female) and Poro (male) societies of West Africa take place in public where various forms of visual symbolism allow onlookers to understand that certain knowledge has been acquired by young female or male initiates (Phillips et al. 2014). Furthermore, a number of studies on Ebola seem to support the idea that occularcentrism is also characteristic to West Africa. For instance, despite extensive health communication campaigns under the banner ‘Ebola is Real’, many communities only believed Ebola was real upon seeing it with their own eyes. As Minor

21 The task of constructing knowledge about other people and places (McEwan, 2009) remains

problematic and one should consider with care the snippets of local perspectives and voice recorded in the academic literature and the analyses and conclusions I make within the present study (see ‘Limitations’).

Peter (2014, p.4) states ‘witnessing Ebola first-hand played a critical role in whether a particular community viewed the disease as a particular issue’ (see also Goguen and Bolten, 2017; HC3, 2017). This is supportive of the possibility that local knowledge is partly acquired and communicated through visual stimuli. As such, visual ‘texts’ could provide an alternative way of accessing local perspectives and knowledge.

Post-modern visual theorists such as Mierzoff (1998) believe that advanced technology has led to the manipulation of the visual to the point where ‘it is no longer possible to make a distinction between the real and the unreal’ (in Rose, 2001, p.4). This has led to the phenomena of popular truth claims (‘#nofilter’, ‘fake news’ etc), which, threaten to undermine an understanding of reality as inter-subjective (Lang, 2017), call into question the authenticity of knowledge acquired through iconic signs, and leads to speculation about contemporary iconoclasm (Stubblefield, 2014). Technologically mediated visual content might also further empower those who are part of the ‘history of science tied to militarism, capitalism, colonialism and male supremacy’ (Haraway, 1991, p.188). Therefore, if local voices are to be recorded using a visual method, non-digital, low-tech approaches such as painting and drawing (as opposed to photography and video) may help protect the visual authenticity of the representations and provide some protection against technologically fuelled hegemonies.

Why art?

“We know more than we can tell”

Michael Polanyi (in Barone and Eisner, 2011, p.158). Whilst Barone and Eisner (2011, p.1) note that ‘[a]ll forms of representation… are both constrained and made possible by the form one chooses to use’, the possibilities provided by art seem to counteract some of the representation-related constraints that come with predominating discursive approaches. Therefore, art, whilst not without its own limitations, is valuable in its application here in a variety of ways.

Whilst one cannot always be certain that the results acquired through visual methods would not have been accessible by other means (Banks, 2014), a unique contribution of the arts is afforded by their expressiveness. As Barone and Eisner (2011, p.159) note,

‘Part of the artist’s task… is to shape language so that it conveys what words in their literal form cannot address. Artistically rendered forms contribute to the enlargement of human understanding because they do what poetry has been said to do, to say in words what words can never say.’

Therefore, the expressive qualities of art might reveal new ideas and knowledge inaccessible to researchers who rely on the written or spoken word. Art, according to Clammer (2014, p.39), is a hermeneutics – ‘a mode of understanding, of grasping the world and of relating human life to that larger cosmos in a non-discursive mode of being in the world’, with the authenticity of knowledge being assured by its emergence ‘from the soil of the culture in which [the art] is produced’ (ibid. p.31). Barber (2008) outlines how through the act of painting, the artist is somatically involved in perception, relying on a deep emotional probing of the self. It is hard to imagine how interviews could achieve the same depth of exploration. Where artworks become ‘texts’, the realms of deep, essential experiences of life, such as human emotion and the sensuous, become accessible to social researchers (Clammer, 2014). To understand experiences of the Other, and their experiences of and perspectives on phenomena that (should) concern us all – communicable disease outbreaks being a pressing example – we must seek to explore and understand shared human experiences. Clammer (2014) has argued that the arts might provide the best channel for doing so.

Art theorists believe visual art acts not as a ‘window onto the world, but rather a created perspective’ (Leavy, 2015, p.224), an imagination. Barone and Eisner (2011, p.124) note that art has a capacity ‘for enhancing alternative meanings that adhere to social phenomena, thereby undercutting the authority of the master narrative’ and hence challenge domination through control of representation22. Therefore, local art on lived

experiences of Ebola may help to provide alternative understandings to those offered by biomedical science and anthropology. Manyozo (2017) recalls Mbembe’s (2001) idea of ‘liminal spaces’, being often found in the arts, where ‘voice acts’ protest oppression.

22 Or, ‘[t]o lay bare the questions which have been hidden by the answers’ (Sullivan, 2000 in Barone and

Looking at the role of the art-object itself, Clammer (2014 p.11) takes these concepts to the conclusion that ‘[a]rt-objects are thus not simply produced by social agents, they are social agents’, which suggests that the process of producing local artworks on Ebola might also have empowering qualities for the artists23.

All these ideas however rely on the presence of audience.

Why the spectatorship of art by the researcher?

It is the concept of art being a mutual exercise (between artist and viewer)24 that makes it of particular value in this study where the artist as Other retains creative control, and the researcher plays a more passive role as viewer who must ‘see’ what the Other ‘means’25. Seeing is always a choice, according to John Berger (1972) and so when we choose to look at something, we are always considering how that thing relates to us. Berger (ibid.) explains how visual artworks embody the way of seeing of the artist but when viewed, the viewer brings their own way of seeing to the image, their own perceptions, and subsequent interpretations. So, if Bresler (2006) is right in remarking that perception is about meaning, then the viewer, as researcher, in perceiving an artwork as research ‘text’, engages in a process of re-seeing, that involves a re-shaping of the world and, by relation, a re-shaping of oneself (Bresler, 2006, p.55). Bresler (2006, p.57) suggests that to embrace other perspectives, we must ‘open ourselves to the full power of what the other is saying’. Where this is achieves ‘fused horizons’ (Gadamer, 1988), ideas of the other become intelligible ‘without our necessarily having to agree with them’ (Bresler, 2006, p.57), leading to dialogue – a speaking ‘to’ rather than speaking ‘for’ or ‘about’, where Owens (1994, in Clammer, 2014, p.31) believes the possibility of a shared global culture might reside.

These ‘fused horizons’ resemble closely the description of the spaces McEwan (2009, p.68) describes in which others can have a voice and be taken seriously. Quinn and Bedworth (1987, p.163) describe how theatrical communication can assist in evoking an

23 This becomes of increased importance for the planned project extension, which considers how the

artworks might have value in pursuing social justice (see ‘Research Design’ and ‘Conclusion’).

24 Barone and Eisner (2011, p.158) describe this process as ‘closer to the idea of “let us reason together”’ 25 This suggests that exhibiting the artworks could help level researcher-participant power dynamics

through a transfer of ‘research dividends’ back to the participants, who – before a viewing audience – assume the title of ‘Artist’.

emotional response that helps ‘position ideas and objects in time and space’, which Chouliaraki (2013, p.22) builds on, describing theatres capacity ‘…to stage human vulnerability as an object of our empathy as well as of critical reflection and deliberation’, achieved through:

‘distancing the spectator from the spectacle of the vulnerable other through the object space of the stage (or any other framing device) whilst, at the same time, enabling proximity between the two through narrative and visual resources that invite our empathetic judgement towards the spectacle’.

Given the strong emotional response Liberians had to both Ebola Virus Disease and the Ebola response (Minor Peters, 2014), visual depictions of Ebola produced by Liberian youth who witnessed the outbreak firsthand, is likely to evoke emotions of a similar nature and combined with the framing effect of visual art, would suggest the right aesthetic distance or theatricality for optimum transfer of meaning from the artists to me as researcher might be struck, even where the sample size is small.

METHODOLOGY

“I never made a painting as a work of art, it’s all research.”

Pablo Picasso This section describes the method as applied to this study. A number of limitations had impact on the method and analysis. See ‘Limitations’ section and below.

Participant selection

The Liberia Visual Arts Academy (LivArts) provided invaluable logistical support, not least in purposive sampling for participants. As outlined in ‘Research Design’, the Academy reached out through existing networks to local schools and the art community to find participants who were interested in attending the workshop as an extracurricular activity and secured permission from teachers and parents. A young demographic was targeted based on reports of increased vulnerability to Ebola in children (Harman, 2014; Rothe et al. 2015; Lappia and Carrick, 2017; Abramowitz, 2017). The target age was necessarily raised to ‘youth’ given the nature of the task requested of participants and the additional complexities involved in working with younger children. Twenty-four students from 12 different schools were granted permission to attend; another eight participants came as non-students (Table 1). Unfortunately the initial aim of striking a gender balance was not met due to participants from a girl’s school being held back unexpectedly the day before the workshop took place (see ‘Limitations’). Participants were provided with breakfast and lunch and a stipend to support their travel costs to the Academy. All participants completed consent forms.

Total no. of participants Age range Median age at time of study / age in 2014 (i.e. onset of Ebola)

Gender split No. of students Occupation of non-students Target 20 16-21yrs 18.5 years (2018) 14.5 years (2014) 50% female

24

Artist (3); Unemployed/Not in school (5)

Actual 32 11-31yrs 18.9 years (2018) 14.9 years (2014)

12.5% female