Transnational Activities of the Zimbabwean diaspora in

London, United Kingdom:

Evidence from a SurveyTawanda Maviga

International Migration and Ethnic Relations

Bachelor Thesis: 15 Credits

Spring 2019: IM245L-91511

Supervisor: Haodong Qi

Word Count: 11 335

Table of Contents

LIST OF ACRONYMS ... 3

1.0 INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1BACKGROUND ... 1

1.2RESEARCH PROBLEM AND RESEARCH QUESTION ... 2

1.3DELIMITATION ... 3

2.0 PREVIOUS RESEARCH ... 4

3.0 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ... 9

3.1MIGRATION NETWORK THEORY ... 9

3.2THE NEW ECONOMICS OF LABOUR MIGRATION THEORY ... 10

3.3TRANSNATIONAL AND DIASPORA THEORY ... 12

3.4MIGRATION SYSTEMS THEORY ... 13

3.5HYPOTHESIS ... 14 4.0 METHODOLOGY ... 16 4.1METHOD ... 16 4.2RESEARCH DESIGN ... 16 4.3SAMPLING ... 17 4.4CODING ... 17

4.5STRENGTHS AND METHODOLOGICAL IMPLICATIONS OF THE SURVEY METHOD ... 17

4.6CRITIQUE OF SURVEY METHOD ... 20

5.0 ANALYSIS ... 21 5.1RESULTS ... 21 5.2DISCUSSION OF RESULTS ... 22 6.0 CONCLUSION ... 32 REFERENCES ... 34 APPENDIX 1 ... 37 APPENDIX 2 ... 38

List of Acronyms

NELM- New Economics of Labour Migration

UK- United Kingdom

USA- United States of America

IOM- International Organisation of Migration

Abstract

The key question that this paper seeks to answer is (1) To what extent are Zimbabweans living in London, in the United Kingdom involved in transnational activities to their country of origin? To try to answer this question I have carried out quantitative analysis of primary data gathered in London and the results show that the Zimbabwean migrants are actively involved in transnational activities to their country of origin. Contact with family and sending money home seem to be the most carried out transnational activities than others. In the

context of this research project, transnational activities will encompass those falling under the socio-cultural domain such as maintaining family ties with relatives in origin country, the economic domain such as sending money to family in origin country and the political domain such as voting back in origin country.

1.0 Introduction

1.1 Background

Looking back in history, there has always been some transnationalism of an economic and political nature. Excellent examples include what Curtin termed ‘trade diasporas’, those communities which consisted of travelling merchants who used to set up home in foreign communities so as to engage in business. At the same time, these merchants were still able to keep their identities, while growing their networks between the ‘new’ home and origin

country, travelling to and from their new base to their country of origin growing their business ventures. As a result, “the foreign enclaves established by Venetian, Genoese and Hanse merchants throughout medieval Europe and identified by Pirenne with the revival of European trade symbolise an early example of economic transnationalism”. Moreover, the 19th century saw a massive movement of foreign labour across state borders and what made this transnational for the migrants was the short period abroad, as well as their reliance on origin country networks for facilitating these jobs and their investing of their earnings back in their countries of origin (Portes, Guarnizo, & Landolt, 1999).

There has always been return migration and home visits by labour migrants

periodically and moreover, political participation has existed before among those immigrants in the diasporas. Great examples include the Russian Jews who escaped the tsarist Pale of Settlement in the 20th century and the Armenians running away from Turkish persecution. Even though these types of activities by migrants cemented friendships between the host and origin communities, they somehow lacked traits of being regular as well as the element of large volumes which distinguish contemporary transnationalism (Portes, Guarnizo, & Landolt, 1999).

On the political front, transnational activities were not as widespread, but those that took place did have a significant impact. Those transnational political activities with impact included committed efforts by some political leaders and activists in the diaspora to free their native lands from control of foreign powers and to support an emerging state. The creation of the nation of Czechoslovakia comes to mind, as in a way it was ‘made in America’ through the leadership of Tomas Masaryk. Moreover, labour migrants also engaged in transnational

politics by donating money and offering moral support to the cause back home. For example, the Polish Relief Central Committee in the United States of America donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to support the Polish national liberation in the early 20th century. These examples give a clear indication that “contemporary transnationalism had plenty precedents in early migration history’’ (Portes, Guarnizo, & Landolt, 1999).

While the literature on transnationalism is not new, literature on transnational activities among Zimbabwean migrants is scarce. The figures estimated of the number of Zimbabweans who have left the country for places such as the United Kingdom are contested since the Zimbabwean government has not kept a proper record of those who have left. The majority of Zimbabweans have migrated to mainly the United Kingdom and South Africa respectively (Crush & Tevera, 2010). International Organisation of Migration (IOM) estimates that about 40 000 Zimbabweans live in London (Ndlovu, 2013).

The Zimbabwean diaspora is very dynamic in carrying out its transnational activities in the United Kingdom whether they be economic, political and socio-cultural.

“Transnational activities can be observed and measured while capabilities refer to the willingness and ability of migrant groups to engage in activities that transcend borders”. To be able to demonstrate transnationalism as a phenomenon, certain conditions have to be fulfilled, such as that the process entails a very large section of people in the world like the migrants and their origin countrymen/women and that these activities can demonstrate the test of time and are not just a passing phase and that these activities do not already exist in some pre-existing concept already (Portes, Guarnizo, & Landolt, 1999). “For the purpose of establishing a novel area of investigation, it is preferable to delimit the concept of

transnationalism to occupations and activities that require regular and sustained social contacts over time across national borders for their implementation” Moreover, to count as genuine phenomena, hence a defensible new topic of investigation, is the strength of the exchanges, the new ways of conduct and the volume of activities that require international travel and sustained contacts regularly (Portes, Guarnizo, & Landolt, 1999).

1.2 Research Problem and Research Question

This project seeks to examine the extent to which the Zimbabwean diaspora living in London, in the United Kingdom is involved in transnational activities as well as to investigate which

transnational activities are more prevalent. Specifically, I focus on six transnational activities, keeping family ties, remittance of money, sending of different type of goods, home visits, membership to a political party in Zimbabwe and voting in Zimbabwe.

My research question, is constructivist as it reveals humans as people who are resourceful and we can ask that question in order to understand the trend of engaging in transnational activities where migrants either take their acquired skills back to their origin country or help their relatives by sending money or goods (Moses & Knutsen, 2012).

Moreover, it is important to ask such a question since constructivism recognizes that it is possible that people may look or do the same thing but have different perceptions of it, for instance, people may engage in transnationalism, their reasons for doing so may be different. Thus, constructivism also recognizes that the agency of humans creates different ontological understanding of the objects being studied, in this case, different transnational activities. It recognizes the diversity and complexity with which people may engage in transnational activities (Moses & Knutsen, 2012).

1.3 Delimitation

For the purpose of this project I have chosen to focus on six transnational activities, family ties, home visits, remitting money, sending of all types of goods to Zimbabwe, political membership and voting in Zimbabwe. There are two distinct types of transnationalism, one that is carried out by multinational companies and those working for those companies, which is commonly referred to as ‘transnationalism from above’ and those transnational activities which are carried out by migrants and their compatriots and commonly referred to as ‘transnationalism from below’ (Portes, Guarnizo, & Landolt, 1999). For the purpose of this project, I will focus on transnationalism activities carried out by individual migrants, namely Zimbabwean migrants in London.

2.0 Previous research

Alice Bloch has written among others a paper titled “Zimbabweans in Britain: Transnational Activities and Capabilities”. In this paper, she analyses the transnational activities of about 500 Zimbabweans living in the UK through the economic, political, social and cultural context. She examines the different ways in which motivations to migrate and how one’s immigration status impacts on what kind of transnational activities take place between the UK and Zimbabwe (Bloch, 2008). The paper also highlights how remittance activities are curtailed by structural exclusions, mainly owing to government policy where you find that a lot of asylum seekers and undocumented migrants are refused the right to participate in the labour market (Bloch, 2008).

She also highlights the cost of living both in the UK and South Africa as a

determining factor when it comes to transnational activity, the higher the cost of living in host countries, the less money one is left with to remit back home (Bloch, 2008). Proximity to origin country is seen as a motivating factor in transnational activity as well as the advanced technology which allows migrants to keep in touch with their families at a reasonable cost. Bloch also presents family as the reason why some migrants are prone to send money home more often and also engage in transnational activities than others (Bloch, 2008).

Vertovec (2004), has articulated and defended transnationalism from critics and actually presents his argument explaining why a lot of migrants today carry out their

activities that link them with their kin and kith who live in countries other than the ones that the migrants reside in. He asks pertinent questions such as, what changes are prompted by this connectedness? in what areas of life? And how strong and sustainable are these changes? He asks these very pertinent questions as a way to understand transnationalism’s take on migrant dynamics. He argues that present migrant practices should be viewed through modes of transformation separate from each other in three areas of activity, what he terms migrants habitus in the socio-cultural domain, conceptual transformation denoting what he refers to as ‘identities-borders-orders’ in the political domain and institutional transformation which has an effect on the financial transfers in the economic domain (Vertovec, 2004).

Vertovec (2004), argues that it is crucial to give more relevance to the social organisation of migrants, instead of looking at the transnational connections of big

corporation, media and communication networks. More importantly, he urges us to look at this organisation of migrants through social scientific research lens on migration. The reason for this, he argues, is to allow for an analytical take on how migrants build their lives in more than one society (Vertovec, 2004). Moreover, his analysis recognises that different kinds of transnationalism affect people differently, like those who travel between host country and origin country or those who stay intact in host country but keep contact with origin country by sending remittances. He highlights how these transnational patterns may differ because of different factors such as family and kinship structures, remittance facilities and prevailing conditions in country of origin (Vertovec, 2004).

Vertovec (2004) also recognises transnationalism as having had an impact on the everyday social way of life of people in host countries and origin countries. Some of those ways of transnational practice that has had an impact on the migrant’s lives is the ability to keep in touch with relatives through telephone calls. The real time effects of using new mobile technology has transformed the lives of many migrants (Vertovec, 2004). He concedes that, even though mobile phones can increase emotional strain in some family relationships, it is important to acknowledge that transnationally, mobile phones have been able to bridge the gap in communication links between migrants and their home countries in a meaningful way (Vertovec, 2004).

Moreover, he articulates how family life has been impacted through transnational actions such as the way parenting is carried out, budget management and the issue of

children. He refers to ‘long-distance parenthood’, a phenomena that is common among most migrants and how these can cause stress, anxieties and financial pressure (Vertovec, 2004).

On the political transformation, he analyses what he calls ‘Homeland allegiances’, where migrants continue to have a keen interest on the political goings on in their origin countries and how improvements in communication, affordable travel costs and the shifting of most countries to dual citizenship has had an impact on how transnational migrant

communities engage in the politics of their homeland. Moreover, he demonstrates how some politicians have been known to take advantage of an imagined nation by campaigning in the host countries of the migrants (Vertovec, 2004).

Mazzucatto (2008) analyses the lives of Ghanaian migrants living in the Netherlands and looks at the impact that these transnational activities have on the migrants. He further argues that the Ghanaian migrant’s contribution in both countries is sometimes stifled by lack of proper documentation as most of the migrants are illegal and highlights how it is expensive or difficult for one to regularise their stay. Nonetheless, Ghanaian home associations formed in the Netherlands pool resources together to send to Ghana to help in the building of health facilities and electrification of villages, thus revealing a transnational Ghanaian society that is impacting the lives of those relatives back home (Mazzucatto, 2008).

Moreover, he analytically looks at what he terms ‘dual objectives’ of Ghanaian migrants whereby they are able to invest back home and look after relatives and at the same time trying to integrate in their host country. He outlines the impact this has on the migrants as they face difficulties in getting work permits, having access to only low paying jobs and the high cost of living in the Netherlands. He also articulates how some of the migrants start their own families in the Netherlands and how this impacts on their transnational activities. Moreover, he reflects on how migrants also pay high taxes in the Netherlands. He concludes by making an interesting observation on how even though the migrants objectives are geared towards Ghana, their immediate priorities are mainly focused on earning a living in the Netherlands (Mazzucatto, 2008).

In ‘Globalisation from below: The Rise of Transnational communities’, Portes (1996) opines that as soon as migrants realise that the salaries and working conditions in the more developed host countries do not meet their economic targets, they circumvent this issue by igniting their social network relationships. He argues that this creates a purpose of

togetherness among migrants. Moreover, he analyses the impact of transnationalism through the establishments of commercial enterprises by migrants in country of origin and how the existence of these enterprises is continually tied to that of their host countries. This

connection is kept intact through support from friends and relatives living in the host

countries. Moreover, some of these migrant entrepreneurs engage in back and forth business between host country and origin country. To illustrate the importance of collective remittance strategies, Portes highlights how towns with a diaspora hometown association have better roads and are electrified and even their sports teams have better equipment. (Portes, 1996).

Foner (1997), compares transnational activities of yesteryear and contemporary transnationalism, and argues that besides modern technology, new global economy and culture, transnationalism is not a new phenomenon. She exemplifies this by pointing out that Italian and Jewish men (80% of migrants were men in the 1870s), left behind families when they migrated in the 1870s and sent money to them and kept in contact through letters. Furthermore, she reveals how the Italian migrants would save money to purchase land and houses back in Italy. Most of them would go back and forth and would say they came to work in the United States of America in order to pay off the land or house they bought in Italy. She argues that this return migration should be viewed as part of a transnational activity, since those coming back have “their feet in two societies” and that it reflects an affiliation to the “norms, values and aspirations of the home society” (Foner, 1997). Transformations in technology in terms of communication and transportation has had a great impact on the lives of transnational migrants, she mentions how even politically, the migrants lives have been transformed as they can now hop on a plane and go vote in country of origin with ease and moreover , dual citizenship in most countries today means that migrants can vote in host country and origin country simultaneously (Foner, 1997).

To summarise previous research, Bloch (2008), has argued how one’s immigration status impacts on the transnational activities carried out, such as sending of remittances, which are curtailed by structural exclusions such as the UK government policy of refusing asylum seekers the right to work. Moreover, Vertovec (2004) argues in favour of transnationalism by migrants and says that it is more important to give more relevance to the social organisation of migrants than that of transnational corporations as it is important to have an analytical take on how migrants are able to build their lives in more than one society. He argues how

transnational patterns of individuals may differ because of different factors such as family, remittance facilities and prevailing conditions in country of origin. Mazzucatto (2008), puts forward an argument that even though Ghanaian migrant’s contribution is sometimes stifled by lack of proper documentation, a lot of Ghanaian home associations in the Netherlands are able to pool resources to send to Ghana to help in the building of health facilities and

electrification of villages. Portes (1996) highlights the power of migrants social networks and argues how the creation of businesses by migrants in country of origin is tied to these social networks as friends and relatives in the diaspora support those business enterprises. Foner

(1997) puts the issue of transnationalism into perspective by arguing that it is not a new phenomenon but rather it has existed for a very long time as illustrated by her examples and says the only difference between transnationalism of yesteryear and the contemporary one is the advanced modern technology, new global economy and culture.

Taking a look at previous research, it is evident that the matter of which transnational activity is more prevalent among the migrants especially Zimbabwean migrants in London could be understudied, as more emphasis and importance seems to be given mostly to the economic and political aspect of transnational activities such as remittances and therefore this thesis hopes to contribute in part to that knowledge gap by measuring and showing that, of the six selected transnational activities, it is not only remittances and political participation which are more prevalent among the Zimbabwean migrants in London but other transnational activities such as contact with family are equally important and popular among Zimbabwean migrants and this thesis will seek to show that.

3.0 Theoretical Framework

3.1 Migration Network Theory

Migration network theory refers to how migrants make and keep social ties with other migrants and with relatives and friends in country of origin and how this leads to the

formation of social networks. Colonialism, labour recruitment, a shared culture or language and geographical proximity are some of the factors which may influence the migration process (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014). Once these migrant network connections are formed, they act as a source of social capital which people can utilise to gain access to employment in foreign countries. The higher the number of migrants and the expansion of these migrant social networks, the cheaper the costs and the lower the risks of movement which then leads to more migration. The pioneers of migration usually have no social ties to their new destination or support, which then makes migration more expensive. However, once these pioneers are settled in host country, the cost of migration for kith and kin left behind is reduced because now these new migrants will have social ties to destination

country. Moreover, once these migrant networks are well established, they make international migration more appealing since they reduce the risk of movement. With every new migrant in destination country and expansion of the migrant network, the less the risk of movement for those related to them (Massey, et al., 1993).

Scholars of yesteryear referred to this as chain migration, while today’s scholars refer to it as network migration and these, according to Massey are, “sets of interpersonal ties that connect migrants, former migrants and non-migrants in origin and destination areas through bonds of kinship, friendship and shared community origin” (Massey, et al., 1993). According to Castles et al (2014), social capital definition as derived from Bourdieu (1985) is ‘the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to the possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalised relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition or in other words, to membership to a group’. Therefore, after financial and human capital, social capital is another resource which affect people’s ability to migrate (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014). As a result, those migrants who are already settled do act as ‘bridgeheads’ for their relatives and friends in origin countries as they help reduce the risk and costs associated with migration by being suppliers of information, helping with travel and finding work in host countries (Böcker, 1994).

Based on migration network theory, one would expect Zimbabwean migrants in London to be more engaged in the transnational activity of keeping in contact with family. My argument is supported by the fact that migration network theory talks about how migrants make and keep social ties with other migrants and with relatives and friends in country of origin and how this may lead to the formation of social networks (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014). Moreover, the Zimbabwean migrants contact with family may, according to migration network theory, lead to these migrant networks connections acting as a source of capital which individuals can utilise to gain access to employment in foreign countries (Massey, et al., 1993).

3.2 The New Economics of Labour Migration Theory

The new economics of labour migration theory (NELM) came about as a critical response to neoclassical migration theory (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014). Stark (1991), argues that within the framework of migration in and from the developing countries, decisions to migrate are usually made by families or households and not individuals alone (Stark, 1991).

Moreover, NELM sees migration as a way of sharing risks within families and households, usually members of the household decide that some of them should migrate, not to access higher income but merely to diversify and decrease income risks, with money remitted by these household members acting as income insurance for the households in origin countries (Stark & Levhari, 1982). Moreover, NELM looks at migration as a household plan to come up with resources for investment in economic enterprises back in origin countries. NELM recognises the imperfect conditions that most households in developing countries operate in, where credit facilities and risk markets are almost non-existent especially for the poor (Stark & Levhari, 1982).

With remittances, families can circumvent these market obstacles by raising their own capital through family members who have migrated and thereby improve their wellbeing. NELM also looks at migration as a way to ‘relative depravation, rather than absolute poverty’ in the countries that migrants come from (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014). Economists within the migration field started to field questions using NELM which were normally asked by anthropologists and sociologists (Stark & Lucas, 1985).

Moreover, NELM has similarities with ‘livelihood approaches’ that were used by anthropologists, geographers and sociologists in the 1970s to carry out micro-research in developing countries. Their observation was that poor people could not be reduced to being mere spectators of the global market forces but actually had human agency in trying to make their life better despite the harsh conditions they lived in (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014). This then fits in well with the notion that in times of depravity and scarcity people galvanise themselves not individually but mostly as a group and in this case, the household being the accurate unit of analysis, with migration being the strategy used to secure a better livelihood (McDowell & de Haan, 1997).

This explains why difference in income cannot be the only reason why migration occurs, the household perspective reiterates that issues such as chances of secure

employment, social security, access to credit by the poor can also contribute to people migrating. This, Castles et al (2014) states, can be exemplified by the Mexican farmers who migrate to the United States of America (USA), even though they own land in Mexico but do not have the money to make the farms productive. They then use migration as a way to earn some capital and keep the productivity of their farms back home whilst working in the USA (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014) .

Based on the NELM theory, one would predict that remittances would be one of the most prevalent transnational activities carried out by Zimbabwean migrants in London. One would argue in favour of this position, since NELM sees migration as a way of sharing risks within families and households, with money remitted by those household members who migrate acting as income insurance for the households in origin countries. Moreover, Zimbabwean migrants may send money home to invest in business or build houses, hence NELM also acknowledges migration as a household plan to come up with resources such as money for investment in economic enterprises back in origin countries (Stark & Levhari, 1982).

3.3 Transnational and diaspora theory

Transnational and diaspora theory focuses on ‘the role of identity formation’, such as what identifies or distinguishes a person or community as being transnational or diasporic. A set of new theories on transnationalism and transnational communities have come up which contest that globalisation has accelerated and made it easy for migrants to maintain network ties with their families in origin countries. Although the advancement in communication and transport technology has not really transformed into growing migration, it certainly has made it not difficult to keep close ties with their countries of origin through the use of mobile telephones, satellite television and the internet as well as be able to remit money either through the official channels or unofficial channels. Moreover, it has made it possible for migrants to nurture several identities, to be able to commute between host country and origin country, work and do business in both as well as engage in political activities in host country and origin country (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014).

Basch et al (1993) have stirred debates on transnationalism by arguing that kinship and migrant networks were uniting families and economies in two or more countries thereby making the modern nation state ‘deterritorialised’ which has great significant outcomes for national identity and politics (Basch, Glick-Schiller, & Blanc, 1993). There are two distinct types of transnationalism, one that is carried out by multinational companies and those working for those companies, which is commonly referred to as ‘transnationalism from above’ and those transnational activities which are carried out by migrants and their

compatriots and commonly referred to as ‘transnationalism from below’ (Portes, Guarnizo, & Landolt, 1999).

Diaspora goes a long way back to the days of ancient Greeks when it was used to describe transnational communities and it meant ‘scattering’ of different people around the world in countries where they did not originate from. Nowadays, the term diaspora is used to describe almost all migrant communities but scholars of migration argue that there is a difference between a diaspora community and other migrant communities (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014). A prototypical diaspora, which may include a classical ‘victim diaspora’, are those who have been dispersed following a traumatic event in country of origin to a foreign

country. However, if we are to talk about a distressing experience suffered by a group collectively, maybe we have to categorise these events separately based on what triggered them to emigrate. It could have been in pursuit of work or trade or a strong ethnic connection within a group that already has relatives in a foreign country, among other factors (Cohen, 2008). Furthermore, not all migrants can be classified as being transnational or diaspora. Some migrants emigrate and do not go back to their origin country and hardly keep contact with their relatives. These, according to Castles et al (2014) cannot be classified as

transnational migrants (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014).

Based on the transnational and diaspora theory, one would expect those Zimbabwean migrants in London who are transnational to be actively involved in transnational activities such as keeping contact with family, home visits and political participation. I argue that, since transnational and diaspora theory is more interested on ‘the role of identity formation’, such as what identifies or distinguishes a person or community as being transnational or diasporic, it may be hypothesised that if the Zimbabwean migrants would actively engage in the above named transnational activities, they would therefore be identified as being transnational (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014).

3.4 Migration Systems Theory

Migration Systems Theory focuses on how migration is naturally linked to other modes of distribution such as the flow of ideas, goods and money and how this affects the atmosphere under which migration happens in both origin and destination countries. Moreover, it allows for a better perception of how migration is deeply rooted in wider processes of social

transformation and development (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014). Pioneers of migration systems theory were fascinated by the role that flows of information and new ideas had in the formation of migration systems. It emphasised the significance of ‘feedback mechanisms’ whereby vital information such as how the migrants have been received and how well they were doing in destination countries was sent back to country of origin. Positive information shared about destination country usually leads to more migration. It connects people, communities and families over distance. “The end result is a set of relatively stable

exchanges; yielding an identifiable geographical structure that persists over space and time” (Mabogunje, 1970).

Besides information, new ideas and being exposed to a different way of life as told by migrants also influences people’s cultural outlook and desires. This sharing of information, flow of ideas, identities and social capital from host countries to origin countries is termed social remittances. As a result, migration systems theory emphasises the importance to examine both ends of migration flows and study the connectedness between the place of origin and host country (Levitt, 1998). The key factor of migration systems theory is that a set of exchange between countries in areas such as trade is likely to influence other forms of exchange such as people and these migration patterns usually come about as a result of previous connections between countries such as colonisation, trade or cultural ties (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014). Moreover, it is important to understand the concept of cumulative causation where, “the idea that migration induces changes in social and economic structures that make additional migration likely” (Massey, 1990) . As a result, we are able to form an idea about how wider migration changes affects communities and societies “which in turn affects migration as contextual feedback mechanisms” (de Haas, 2010).

I argue that, based on migration systems theory, one would expect Zimbabwean migrants in London to engage in transnational activities such as contact with family, sending goods, sending remittances and home visits. This argument is based on migration systems theory, which demonstrates how migration is naturally linked to other modes of distribution such as the flow of ideas, goods and money and how this affects the atmosphere under which migration happens in both origin and destination countries. The subsequent sharing of

information through contact with family and home visits, in this case, by the Zimbabwean migrants in London would then expose those in Zimbabwe to new ideas and a different way of life as told by the Zimbabwean migrants and it could be argued further that remittances sent by the Zimbabwean migrants in London would then be used as a tool for development since migration systems theory allows for a better perception of how migration is deeply rooted in wider processes of social transformation and development (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014).

3.5 Hypothesis

My general hypothesis is that if Zimbabwean migrants in London are transnational, they should engage in transnational activities such as contact with family through various means

of communication e.g. telephone or use of social media, home visits, remitting money to Zimbabwe, sending goods and political participation such as membership to a political party in Zimbabwe and voting in Zimbabwe. However, the magnitude of engagement may vary across different transnational activities, as some activities might be dependent on some other factors such as one’s economic wellbeing, family circumstance, among others.

Specifically, I hypothesise that, if Zimbabwean migrants in London are transnational,

• They should have contact with family. Given that the costs of

telecommunication and internet communication have gone down rapidly over time, one would expect that contact with family would be a regular

transnational activity.

• They should visit home, but the frequency of the visits would be hard to say a priori, as it may depend on factors such as one’s economic circumstances and moreover, one’s legal status in the UK.

• Most would engage in sending remittances, but the frequency and the quantity of the remittances are hard to say a priori, as this may depend on an

individual’s economic circumstances and employment, among other economic factors.

• Most would send goods home, but the frequency is hard to say a priori, as it may depend on affordability of sending goods, which may be determined by an individual’s economic circumstances.

• Most would participate in political activities such as voting, among others, but it is hard to estimate the frequency a priori, since this may depend on a

number of factors such as one’s legal status in the UK, which may affect one’s movement such as being able to go home and vote as well as economic

circumstances, if one would be able to contribute to political causes back in Zimbabwe.

4.0 Methodology

4.1 Method

The thesis project relies on survey method with structured interviews. A survey is described as “a method of gathering information from a sample of individuals (de Leeuw, Hox, & Dillman, 2008). Surveys play an integral part in social research as they give a quick and less expensive way of finding out the characteristics and beliefs of a certain population being investigated. Surveys constitute the collection of data from a certain number of people and it could be a small local survey with a few people or a national survey with hundreds of

thousands of people (May, 2011). For the purpose of this project, a small survey constituting a small part of the Zimbabwean diaspora living in London, in the United Kingdom, 30 people in total were interviewed.

4.2 Research Design

Structured interviews are mostly associated with the survey research method and I am going to utilise a questionnaire as my primary data collection instrument. “The theory behind this message is that each person is asked the same question in the same way so that any

differences between the answers are held to be real ones as a result of the deployment of a method and not the result of the interview context” (May, 2011). I can then ascertain validity by asking the respondent about the same matter by using the same way of question wording and then compare both answers. My task as an interviewer is to direct the respondent to the questions to be answered and not offer any illustrations that may influence the answers. Therefore, my neutrality as an interviewer is critically important. The issue of the method such as standardisation is important as explained before, no moving away from the planned questionnaire, only the respondents answers matter, no offering a personal view point or trying to interpret questions (May, 2011).

A structured interview will allow for ‘comparability’ between the answers, as a result, a uniform structure is necessary (May, 2011). The advantages of employing a self-completion questionnaire with closed format questions is that it is low cost and fast to administer.

Moreover, the personal influence of the researcher is removed as well as the variability between researchers. They can also be very appropriate for the respondents and a good source

of quantitative data (Walliman, 2006). The downside of self-completion questionnaires is that they can be difficult to design and develop as well as time consuming. Some critics point out that they restrict the extent of questioning and make probing not possible, hence lowers the prospect of getting more data. A coding frame will be conceived and included in the questionnaire design to make it easier to code and handle data in the analysis stage (Walliman, 2006).

4.3 Sampling

Sampling will take place when a survey is undertaken using a questionnaire and depending on the aims of the survey, a generalisation can then be made from the sample of the

respondents of a certain group of a population interviewed (May, 2011). For the purposes of this project, I randomly selected 30 respondents from the Zimbabwean migrant population living in London.

4.4 Coding

Coding is by definition, “the way in which we allocate a numeric code to each category of a variable”, this easily allows for the preparation of data for computer analysis. The

questionnaire for this research project shall administer closed questions and I will pre code the responses so as to “Allow for the classification of responses into analysable and

meaningful categories”. Moreover, the category answers will not only be ‘mutually

exclusive’ but ‘exhaustive’ as well, meaning someone’s answer to a question will not fall into two categories used. Therefore, data from each question will be stored as a variable (May, 2011).

Furthermore, my questions on the questionnaire will have response categories, of which I will assign each category a numeric value of 1 to 5 for questions 1 and 2, questions 3 and 4 categories will have a numeric value of 1 to 4 and questions 5 and 6 categories will have a numeric value of 1 to 2 respectively. I am using these type of questions as a way to try and collect factual information (May, 2011). Lastly, I will code my questions as variables Q1 to Q6 and identify my respondents by assigning each questionnaire a numeric value from ID 1 to ID 30.

4.5 Strengths and methodological implications of the Survey method

The purpose of surveys is to explain or describe certain characteristics or opinions of a certain population by using a representative sample. As a result, it is very important when

doing a social survey to pay attention to the research design and the data collection method. There are different types of surveys such as factual, attitudinal, social psychological and explanatory. For this project, I will utilise the explanatory survey since it is more theory oriented. Moreover, an explanatory survey will allow me to ask questions about transnational behaviour and then try to explain how people’s attitudes or intentions are linked to their background or some other ‘explanatory variable’. More importantly, explanatory surveys are carried out in a way that they test hypotheses which are derived from theories (May, 2011). It is important for me as a researcher to be clear which concept I wish to measure before I formulate my questions. I will do this by naming the concept, in this case transnational activities of the Zimbabwe diaspora living in London, in the United Kingdom, be able to describe its scope and properties and as well as defining it’s many different forms (de Leeuw, Hox, & Dillman, 2008).

All surveys atleast start with theoretical assumptions, either some to test some

theories while others to build up theories. A great survey will begin by testing and developing a theory, after which a hypothesis is formed. A hypothesis is a proposed explanation derived from a theory, which if found not to be false would reinforce the theory or if found to be incorrect, the theory would be rejected. The ‘confirmation and falsification of theories’, can be complicated and contentious and this is where as a researcher, I would look at statistical evidence for a theory instead of ‘proof’ (May, 2011).

Since surveys calculate facts, behaviour or attitudes by way of questions, its pertinent that hypotheses can be ‘operationalised into measures’, this means that questions should be created, of which respondents can easily understand and answer. Subsequently, those answers should then be able to be categorised and quantified. This process of operationalisation consists of selecting empirical indicators for each concept or subdomain. To close the gap between theory and measurement, two well defined research strategies are recommended, an inductive reasoning, through observations working towards theoretical construction and deductive reasoning which begins with theory construction and works towards variables that can be observed (de Leeuw, Hox, & Dillman, 2008). A specification error occurs when a final research question to a respondent is unable to ask about what is important for the research question, consequently, the wrong variable is evaluated, leading to a failure to reach the objective of the research. As a result, to minimise the specification errors, the outline and concept of the questionnaire has to be thoroughly looked at by the researcher and be certain

that the questions being asked revolve around the objectives of the study (de Leeuw, Hox, & Dillman, 2008).

Whilst it is feasible that a survey can be able to ‘confirm’ or ‘falsify’ a theory, the likely scenario is that the theory is altered to suit the new findings. The survey method’s objective is to eliminate as much bias from the research process as possible and come up with results that can be reproduced using the same methods such as standardisation., meaning the conditions that a survey is carried under, but more importantly how the questionnaire has been planned, managed and analysed. Moreover, the important supposition is that of ‘equivalence of stimulus’, where we have to depend on the interviewer’s expertise to ‘approach as nearly as possible the notion that every respondent has been asked the same questions, with the same meaning, in the same words, same intonation, same sequence, in the same setting and so on’. The supposition here is that if a distinction in replies to the questions exist, these distinctions can be accredited to a ‘true’ distinction in point of view rather than the way the question was put forward or the factors of the interview. Therefore, their answers and attributes can then be quantified and collected with others in the survey sample (May, 2011).

Moreover, there is replicability, making it feasible for other researchers to reproduce the survey utilising the same type of sampling, questionnaire and process. This reproduction of a survey producing the same results with non-identical groups at different times increases the confidence in the first findings and is also connected to reliability and validity of the survey (May, 2011) . When using quantitative survey design as a method, it is important to be able to determine my sample size as well as how to deal with non-response bias. “One of the real advantages of quantitative methods is their ability to use smaller groups of people to make inferences about larger groups that would be prohibitively expensive to study” (Barlett, Kotrlik, & Higgins, 2001).

Since surveys collect data from a sample, a small part of a population, due diligence must be followed in the data collection to avoid errors, such as, coverage error that can occur when some people in the population have no prospect of being chosen in the survey sample and this can be circumvented by making sure everyone of the population has a known small chance of being chosen in the survey. Secondly, a sampling error takes place when a set whose members belong to another set is surveyed and this can be remedied by sampling more

random selected units to get the accurateness desired. Thirdly, a non-response error occurs when there is no response from some of the sample component and those components are distinct from the others who are applicable to the study and this can be avoided when everyone responds. Lastly, the measurement error takes place because the respondent has answered the question incorrectly and this can be avoided by asking respondents clear questions which they are able to answer easily. A survey design may have an effect on the data analysis, if the coverage error and non-response error is altered, it may produce data that does not mirror the population and the best adjustment method would be to rely on the prominent features of which that population is well known for. This is one way in which the foundation can affect the structure (de Leeuw, Hox, & Dillman, 2008).

4.6 Critique of Survey method

The survey method has its critics, such as those not impressed by the numbers. The most popular critique of the survey method is how it makes an effort to reveal ‘causal relations’, connecting variables, something which is deemed not appropriate in the domain of human action. Two variables may be connected but this connection does not mean one variable creates change in the other. Researchers in survey method reveal only the power of connection between variables but, causal claims would not be well founded in only

examining two variables in isolation but this does not eliminate the probability of measuring connection (May, 2011).

Moreover, another weakness of survey method is that it eliminates the probability of interpreting the procedure by which people acquire certain values and behaviours. This critique of the survey method seems true if the survey research takes places without a proper theoretical foundation (May, 2011). Another weakness, is the assumption that a researcher may have bias, that may lead them to ask certain questions. It is argued that this may stop people from answering in a certain way and it becomes predetermined that the ‘theories are proven’. Moreover, with the way the questionnaires are designed, it has already been predetermined what questions to ask and it is then said that the deductive method has not worked because the theorist’s assumptions ‘have guided the research’ (May, 2011).

5.0 Analysis

5.1 Results

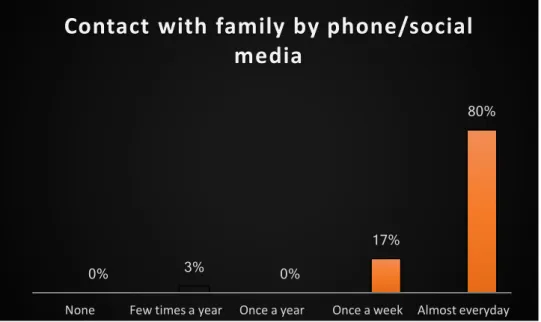

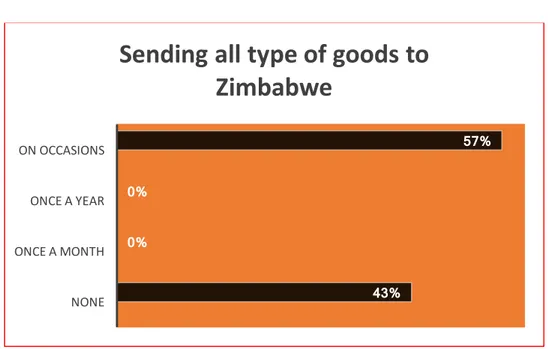

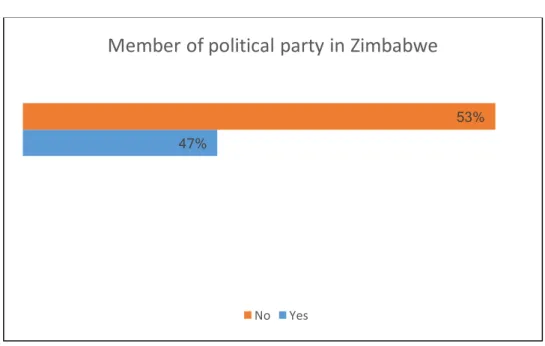

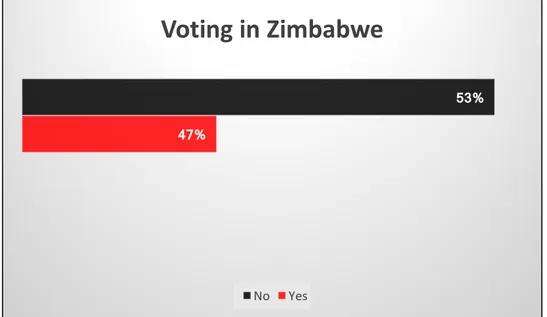

The survey consisted of 30 randomly selected Zimbabwean migrants living in London. A total of 80% Zimbabwean migrants had contact with family almost every day, whilst 17% had contact with family once a week and 3% only a few times a year. With home visits, 30% visited Zimbabwe once a year, 23% more than once a year, another 23% visit every 2 years and 23% do not visit at all. Those sending

remittances, 53% send once every month, 20% more than once a month, another 20% a few times a year and 7% do not remit at all. Those who send goods, 57% do so on occasions, whilst 43% do not send goods at all. A total of 53% do not belong to any political party, whilst 47% belong to a political party and lastly 53% do not vote in Zimbabwe whilst 47% do participate in voting in Zimbabwe.

The coded results in figure 8 in the appendix gives us an overview of the extent to which Zimbabweans living in London, in the UK are involved in transnational activities. They reveal transnational activities as being a common practice among most Zimbabweans living in London. All six variables coded Q1 to Q6 reflect how often they engage in the selected transnational activities. It is also shows the correlation between variable Q5 and Q6, where the results obtained are similar with the assumption that Q6 would be dependent on Q5, meaning that the probability or motivation of one voting in Zimbabwe could be dependent on one being a member of a political party. The results show that Q1, is the most frequent transnational activity and answer coded number 5 being the most frequent. The second popular transnational activity is variable Q3, with the answer coded number 3 being the frequent one.

Figure 1: Variable Q1

5.2 Discussion of results

Figure 1represents contact with family by phone or social media, the survey results on figure 1 above show that 3% call or interact with their families a few times a year, whilst 17% have contact with family atleast once a week and 80% have regular contact with their families almost every day. Moreover, the survey revealed that every individual had some form of contact with their family in Zimbabwe. This evidence from the survey fits into the migration network theory which states that migrants maintain and keep social ties with relatives in countries of origin long after they have migrated (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014). The 80% frequency of those who keep contact with relatives in Zimbabwe on almost a daily basis reflects a solid migrant network base. The real time effects of using new mobile technology has transformed the lives of many migrants. Even though mobile phones can increase emotional strain in some family relationships, it is important to acknowledge that transnationally, mobile phones have been able to bridge the gap in communication links between migrants and their home countries in a meaningful way (Vertovec, 2004).

Moreover, these migrant networks act as a form of social capital through which relatives in origin countries can use to gain access to employment opportunities in the host countries of their kith and kin. Migration network theory states that the more the migrants, the bigger the migrant networks and the cheaper the costs of migration become and less risky,

0% 3% 0%

17%

80%

None Few times a year Once a year Once a week Almost everyday

Contact with family by phone/social

media

leading to more migration. The significance of the migration networks is that, historically, the pioneers of migration had it tough because of lack of these social ties in destination countries, which meant that migration was more expensive for them and risky. With the maintenance and continuation of family ties between the Zimbabwean migrants in London and those in Zimbabwe in this case, according to Massey et al (1993), this means that the costs of migration are reduced and moreover, the risk of international migration is reduced and becomes more appealing as their kith and kin now have social ties in destination country (Massey, et al., 1993). Moreover, by having constant contact with relatives back home the Zimbabwean migrants act as ‘bridgeheads’ for family back home by reducing the cost of migration as well as the risks involved by being the suppliers of information about their host countries (Böcker, 1994).

The thought that migration is a ‘path dependant process’ because communication between people give form to ensuing migration trends has been around for a long time. Therefore, migrant networks can be described as forms of communication ties that binds migrants and non-migrants in destination and origin places through connections of kinship, friendship and similar origins. Hence Bourdieu (1985) described social capital as ‘the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to the possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalised relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition or in other words to membership in a group’ (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014).

Subsequently, looking at the high transnational activity of the Zimbabwean diaspora in keeping ties and communicating with relatives and family back home, it is possible to propose that a migrant network has been formed due to the communication ties that binds them to their kith and kin in Zimbabwe.

New, cheaper technologies in communication as well the advancement of the

transportation system means that more migrants are able to maintain social ties with relatives back home more frequently than before. This technological advancement has allowed for strong ties to be cemented and in addition, today’s migrants have inherited a social world that is more tolerant to ethnic diversity and their transnational behaviour than that of old which emphasised assimilation. As a result, migrants can maintain their social and cultural differences which they sustain through regular contact with their country of origin (Levitt, DeWind, & Vertovec, 2003).

Moreover, “individuals whose transnational activities involve many arenas of social life can be said to engage in comprehensive transnational activities, while others who take part in only a few activities are said to be more selective”. The majority of Zimbabwean migrants in this survey seem to exhibit more of the comprehensive transnational activities than the selective transnational activities. Therefore, the transnational activities of those Zimbabwean migrants whose source of livelihood may be dependent on several interest back in Zimbabwe or are renowned political party activists may be classified as intensively transnational than those whose activities are occasional or over a certain period of time, whether it be sending money or home visits (Levitt, DeWind, & Vertovec, 2003).

The social, economic and political ties connecting migrants and non-migrants are so entrenched and common such that they have an effect on how individuals earn their

livelihood. Once it starts, migration expands through social networks, even though some may not expand as with time some migrants become embedded into their host societies but

nevertheless, this survey has shown that the majority of Zimbabwean migrants continue to engage and keep contact with their relatives on a regular basis. This regular contact between migrants and their relatives back in origin country has the potential to turn these migrant social networks into transnational fields between host and sending country. Therefore, individuals become part of these transnational fields and these activities are then shaped by the social fields in which they take place. As a result, those who operate within the

transnational fields are prone to a set of social expectations, cultural values and patterns of human interaction such as the regularity of the Zimbabwean migrants as shown in the survey in carrying out home visits or keeping contact through regular phone calls or interaction on social media platforms. “the more diverse and thick a transnational field is, the greater the number of ways it offers migrants to remain active in their homelands” (Levitt, 2002).

Moreover, ‘core transnationalism’ are those activities that “are undertaken on a regular basis; form an integral part of the individual’s habitual life; are patterned and therefore somewhat predictable whilst ‘expanded transnationalism’ refers to migrants who engage in occasional transnational activities”. These differentiations in transnational activities help in operationalising variations with regards to the intensity and frequency of transnational activities. In the case of this survey, the results show that most of the

Zimbabwean migrants engage in core transnationalism rooted in migration network theory where maintenance of ties with family back home is important. It is also crucial to note that a migrant may engage in a core transnational activity and at the same time also engage in expanded transnational activities as evidenced in the results of the survey on Zimbabwean migrants in London, where a migrant maintains contact with family almost every day but at the same time they do not vote in Zimbabwe (Levitt, 2002).

Levitt came up with the concept of ‘social remittances’ as a way of explaining the dispersing of cultural forms, systems of practice and social capital (Levitt, 1998). A good example is that through regular home visits to Zimbabwe as shown by the results of the survey, migrants could share ideas about gender roles, identities or political participation. The Permanent Secretary in the Ministry Macro Economic Planning and Investment Promotion had this to say about the Zimbabwean diaspora, “The government recognises that beyond remittances from abroad, our diaspora presents social, economic, intellectual and political capital, a pool of knowledge and expertise which must be harnessed for the benefit of the country” (IOM UN MIGRATION, 2017). Moreover, social remittances may also mean that migrants come back to with new skills acquired in host countries (Bartram, Poros, & Monforte, 2014). Zimbabweans in the diaspora play a significant role with regards to decision making and national development through neutral platforms where dialogue and new schemes can be discussed (IOM UN MIGRATION, 2017). Migration systems theory is more interested in how migration is connected to other modes of distribution such as the flow of ideas, flow of goods and money and how this affects the atmosphere under which

migration takes place in both sending and receiving countries. At the same time, it allows for a better perception of how migration is deeply rooted in wider processes of social

transformation and development (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014).

Figure 2 shows that 30% of the Zimbabwean migrants in London visit Zimbabwe at least once a year, whilst 23% visit home more than once a year and another 23% visit home once every two years. A further 23% does not visit home at all, and this might be explained by Bloch’s analysis that one’s immigration status, legal entitlement to work, having a job as well as freedom to move may be some of the stumbling blocks in why one can be unable to partake in home visits to their country of origin (Bloch, 2010).

Figure 2: Variable Q2 Figure 3: Variable Q3 23% 0% 23% 30% 23% None Once every

5years Once every 2years Once a year More than once a year

Home visits

7% 20% 53% 20% NONE FEW TIMES A YEAR ONCE EVERY MONTH MORE THAN ONCE A MONTHRemitting money to Zimbabwe

Figure 3 shows that almost 93% of the Zimbabwean migrant population in London remits money to Zimbabwe regularly, with 53% of those remitting once a month, 20% remitting a few times a year whilst another 20% remits more than once a month. According to the World Bank, over the last 3 years, Zimbabwe has received $1,85 billion through remittances (Vinga, 2018). Moreover, this amounts to 9,6% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) (Matibe, 2019). Most of the money remitted goes into domestic consumption, mainly because of liquidity challenges that affect most households in Zimbabwe (Bhoroma, 2018).The new economics of labour migration (NELM) recognises that decisions to migrate is usually made by families or household members and not just individuals alone. NELM sees migration as a way of sharing risks within families or households when members of the household decide that some of them should migrate, in order to diversify and decrease risks, with money

remitted by these household members acting as income insurance for the households in origin countries (Stark & Levhari, 1982). Only about 7% of the Zimbabwe migrant population in London does not remit money at all and this could be explained by how remittance activities can be curtailed by structural exclusions, mainly owing to government policy where you find that a lot of asylum seekers and undocumented migrants are refused the right to participate in the labour market in the UK and the high cost of living in London could be another

determining factor whether someone is able to remit money to Zimbabwe, since the less money one is left with, the less chances of them remitting (Bloch, 2008).

The deteriorating economic situation has led to most Zimbabweans having to send money home regularly to struggling families. “Diaspora remittances are a critical source of liquidity in the economy with more families relying on the revenue stream for support from their loved ones who work outside the country”. Most people have also complained over difficulties in accessing their money from banks (Chamba, 2019). NELM also recognises the imperfect conditions that most households in developing countries operate in, where credit facilities and risk markets are almost non-existent, especially for the poor (Stark & Levhari, 1982). Using remittances, some of these market forces can be circumvented through those family members who have migrated and send money home often (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014).

The rise of remittances over the past few years seem to point to a resilient Zimbabwean diaspora which has managed to keep families afloat through economic

hardship. Remittances in Zimbabwe have grown to become the second largest source of liquidity after mineral exports (Bhoroma, 2018). NELM has often been likened to the ‘livelihood’ approaches used in the 1970s to carry out micro-research in developing

countries. Its observation was that poor people could not be reduced to being mere spectators of the global market forces but actually had human agency in trying to make life better despite the harsh conditions they lived in (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014).

Figure 4: Variable Q4

Figure 4 shows that 57% of Zimbabwean migrants send goods to Zimbabwe on occasions while 43% of them do not send any goods at all. Overall, it shows a Zimbabwean migrant community that engages in this transnational activity of sending goods to Zimbabwe.

However, the reason why Zimbabwean migrants could be sending goods occasionally may be linked to the high costs of sending goods. In 2017, the Wall Street Journal reported that shipping companies spent $1.5 trillion on shipping costs only and the shipping costs had risen by between 5 and 15%. As a result, the costs to ship goods rises for the consumers (Phillips, 2018). Since transnational activities can be observed and measured, capabilities, meaning “the willingness and ability of migrant groups to engage in activities that transcend borders”, are usually decided by identifying with the social, economic and political procedures in origin country and also by the mechanisms that allow partaking in transnational activities, be

43% 0% 0% 57% NONE ONCE A MONTH ONCE A YEAR ON OCCASIONS

Sending all type of goods to

Zimbabwe

it the migrants social capital or opportunities in host country (Bloch, 2010). The willingness of Zimbabwean migrants to engage in a transnational activity that seems expensive maybe as a result of previous connections between countries such as colonisation, trade or cultural ties (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014). As a result, we can see how migration systems theory focuses on how migration is naturally linked to other modes of distribution such as the flow of ideas, goods and money and how this affects the atmosphere under which migration happens in both origin and destination countries (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014).

In the survey, every Zimbabwean migrant has some form of contact with family back home. According to Foner (1997), this has been made easy by the transformation in

technology in terms of communication and improvement in transportation which now allow migrants to fly long distances over a short space of time to carry out home visits with less hassles (Foner, 1997). Even though the transformation in technologies has not necessarily led to an increase in migration, it has enabled migrants to cultivate a closer relationship with their countries of origin through the use of mobile phones and the internet and being able to remit money fast in minutes through the interconnected banking systems (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014). Over the years, a lot of different channels such as mobile money remittances have been established which transfer money instantly and directly to the recipients mobile money wallets (TECHZIM, 2016).

Figure 5: Variable Q5

Figure 5 and figure 6 results from the survey exhibit some correlation between the two variables. Those who are not members of a political party stand at 53%, whilst those who are members are 47% of the Zimbabwe migrant population in London. Interestingly, those who do not vote in Zimbabwe amount to 53% whilst those who go and vote are 47%. The reason behind having less Zimbabwean migrants not voting in Zimbabwe might be due to the fact that the Zimbabwean migrants have long been denied the right to vote from outside the country, at their respective bases. To be eligible to vote, one must go to Zimbabwe and register to vote there in person. Evidence shows that the Constitutional Court of Zimbabwe recently blocked millions of Zimbabwean migrants from voting in the country’s elections by refusing to amend the provisions of the Electoral Act in order to allow them to vote from their respective bases in the diaspora. This was after an application had been filed by 3 Zimbabwe migrants based in South Africa and the UK respectively (Ncube, 2018).

Moreover, those who left Zimbabwe due to political reasons are the ones who may feel more inclined to take part in political transnational activities (Bloch, 2010).

Zimbabwean migrants may be refused the right to vote in the diaspora but this does not deter them from participating in transnational political activities in Zimbabwe through initiatives such as crowd funding towards political causes. In the last election of 2018, the

47%

53%

Member of political party in Zimbabwe

Zimbabwean diaspora based in the UK and South Africa launched an online campaign to raise funds to help losing presidential candidate Nelson Chamisa meet his legal costs amounting to almost $3 million. Part of the crowdfunding campaign read, “let’s give generously, to fight this cynical ploy to silence a critical voice defending human rights, democracy and change in Zimbabwe” (IOL, 2018). Transnational and diaspora theory emphasises “the ability of migrants to foster multiple identities, to travel back and forth, to relate to people, to work and to do business and politics simultaneously in distant places” (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014). Even though the Zimbabwean migrants may be far away from their country of origin, their contribution to the political landscape in Zimbabwe

through their transnational political activities is clearly evident.

Figure 6: Variable Q 6

47%

53%

Voting in Zimbabwe

6.0 Conclusion

This research project seeks to improve our understanding of transnationalism by studying the six selected transnational activities. Based on a random sample of Zimbabwean migrants living in London, I address the question: To what extent are Zimbabwean migrants living in London, in the UK involved in transnational activities to their country of origin?

In this project, I conducted 30 structured interviews with Zimbabwean migrants living in London, in the UK. The survey results showed that the socio-cultural activity of having contact with family was the most prevalent of the six transnational activities being studied, followed by the economic transnational activity of remitting money back home. These two transnational activities emerged as the most dominant. Almost everyone seems to have some contact with family either by telephone or through social media. I further articulated how migration theory states that migrants maintain and keep social ties with family in countries of origin long after they have migrated (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014) and, how new

technology such as mobile phones has been able to bridge the gap in the communication links between migrants and their home counties in a meaningful way (Vertovec, 2004). The results revealed that only a small percentage (7%), does not remit any money at all and this could be down to structural exclusions such as lack of access to the labour market for those without legal status according to Bloch (2008). Moreover, there is a significant number of those who send money home more than once a month. To support these results on remittances is NELM, which sees migration as way of sharing risks within families and households, when members of the household decide that some of them should migrate, in order to diversify and decrease risks, with money remitted by those household members used as income insurance (Stark & Levhari, 1982).

The number of home visits shows a visit once a year being the most popular, whilst home visits once every 2 years, more than once a year and those who do not visit at all stand at 23% each. This shows that home visits are not varied to some extent but the overall result shows a Zimbabwean migrant diaspora community which visits home often. Migration systems theory is more interested in how migration is connected to other modes of

distribution such as the flow of ideas, goods and money (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2014). Therefore, regular visits home by Zimbabwean migrants could result in the sharing of ideas in what Levitt termed ‘social remittances’ (Levitt, 1998). With regards to the economic