ORIGINAL ARTICLE

EXPECTATIONS OF POST-PARTUM CARE

AMONG PREGNANT WOMEN LIVING

IN THE NORTH OF SWEDEN

Inger Lindberg ¹, Kerstin Öhrling ¹, Kyllike Christensson ²

¹Division of Nursing, Department of Health Science, Luleå University of Technology, Luleå, Sweden ²Department of Women’s and Child Health, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

Received 7 March 2008; Accepted 22 September 2008

ABSTRACT Objectives. To describe expectations of post-partum care among pregnant women living in the north of Sweden and whether personality determines preference for care systems. The time for post-partum care on maternity wards has been reduced in Western countries. This, along with the reduction in special medical treatments offered and the closure of small hospi-tals has affected pregnant women and their families. Study Design. Data was extracted from a questionnaire and a personality instrument (SSP) that were completed during November 2002.

Methods. In the northernmost county of Sweden, 140 pregnant women completed the ques-tionnaire; of these, 120 completed the SSP instrument.

Results. Of the women who participated, 61.3% wanted to be discharged 72 hours after childbirth, irrespective of the distance between the hospital and home. To have access to maternity ward staff and the decision to be discharged were described as being the most important issues in maternity ward care. The infant’s father was expected to be the most important person in the post-partum period. Conclusions. Women ranked the opportunity to decide for themselves when to be discharged from the maternity ward as important, which can be interpreted as a strong signal that the women want to be in control of the care they receive. Midwives have to focus more on the woman and her family’s individual needs, and to include the father as a person who also needs support and to provide resources for him.

(Int J Circumpolar Health 2008; 67(5):472–483)

INTRODUCTION

The amount of time for post-partum care on maternity wards has been considerably reduced in Western countries (1). Discharge within 3 days for a healthy mother and child following a normal birth is most often the case, despite the fact that criteria for early discharge varies between clinics and countries (2–4). The general case in Sweden is a length of stay of 2 to 5 days, following normal childbirth, with an average in the northernmost county of 2 to 6 days post-partum (National Board of Health and Welfare, Milla Bennis, 2006, personal communication).

In the mid-1980s, early discharge after hospital birth was evaluated and introduced in Sweden in order to facilitate more family- oriented post-natal care (4). Since then, addi-tional changes have been made within the Swedish health care system that has also had an overt influence on post-partum care in the hospital setting. These include a reduction in the number of special medical treatments offered and the closure of many small hospi-tals within each county (5). Between 2001 and 2002, 3 out of 5 maternity departments have been closed in the northernmost county. As this region is partially rural, questions remain about the impact such changes have made on expectations the population have for post-partum care, given the longer distances to reach the hospital and the shortened length of stay, as well as how the reduction of maternity departments has affected pregnant women and their families emotionally and practically. At present, maternal and post-partum care in Sweden can take place either on traditional maternity wards or on wards situated close to the hospital (which have a homelike environ-ment with the support of a midwife), at patient hotels (daytime rooms with medical care avail-able) or in early discharge systems. Maternity care is organized by hospitals at the county level and includes a system of midwives who act as primary caregivers for the mother, while pre- and post-natal and child health care are under the jurisdiction of community primary health care centres that maintain a primary care nurse as the key contact person for the mother and family (6,7). The organization of post-partum care varies across the country, but most often includes follow-up visits to the maternity ward and/or home visits from the maternity ward midwives or midwives working in early-discharge teams. Within some areas of Sweden there are no follow-up visits (6).

Studies focusing on needs in the post-partum period found that breastfeeding and baby care were of great concern, especially for primiparae (8–10), while multiparae had more concerns relating to life-style and rela-tions within the family due to the new family member (9,10). Studying parental needs for care, Persson and Dykes (11) and Fredriksson et al. (12) found that the kinds of care parents valued most was the kind that respected the families/’parents’ experiences and that made available the necessary resources for handling their new role as parents. Other important issues were continuity of care during the post-partum period (13–16), as well as practical and emotional support (17). Media and the Internet are sources of infor-mation that parents often use before arriving at the maternity department (18). Such acquired knowledge leads parents to have expectations and to make demands on caregivers during and after childbirth. As they are also familiar with information and communication technology,

these formats provide an accepted and even attractive alternative or complement to early-discharge systems.

Studies focusing on the need for new models of care to improve birth outcomes show that special conditions prevail in the provision of post-partum care in rural areas (19–21). Considering the situation in northern Sweden, with a reduction of maternity departments, longer distances to care and shortened hospital stays, questions are being raised to determine if these circumstances have affected women’s expectations for post-partum care on the maternity ward and after discharge from the hospital. Another question raised is if women in this area are more stressed and anxious due to the structural change, and whether this determines their preference for care systems.

The aim of this study was to describe expectations for post-partum care among preg-nant women living in the north of Sweden and whether personality determines preference for care systems.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

During November 2002, all pregnant women visiting the prenatal clinics within the north-ernmost county of Sweden were informed about the study. The region, covering about 25% of Sweden’s land mass is character-ized by both densely and sparsely populated areas, with a total of 252,856 inhabitants (22). Midwives working at prenatal clinics assisted in the recruitment of pregnant women for the study and distributed the questionnaires with addressed envelopes. The inclusion criteria were that the women must be able to read and write Swedish, be between 36 + 0 and 37 + 6

weeks of pregnancy, and must be diagnosed as having an uncomplicated pregnancy and be expecting an uncomplicated delivery.

The sample size in this study consisted of 10% of expected pregnancies/childbirths during one year. There was no power calcula-tion on sample size, as the aim of the study was to clarify descriptions of expectations and not to detect differences in them (23). Of the 149 women who fulfilled the criteria, 9 declined to participate, mostly because they did not have the time. The remaining 140 (94%) women (primipara, n=54 and multipara n=85, one woman did not answer the question) completed the questionnaire, although some of them did not answer all the questions. However, no systematic pattern was found in the missing data/responses. An instrument, the Swedish Universities’ Scales of Personality (SSP), was attached to the questionnaire and completed by 120 of the 140 participants. Some women who did not completely fill out the questionnaire commented that it was too demanding to also answer questions on the SSP instrument.

Data collection

Questionnaire and instruments

The questionnaire had 4 questions about sociodemographic data and obstetrical back- ground (items 1–4), 17 questions about expec-tations of post-partum care regarding support to breastfeeding, childcare, physical and psychological recovery, the family’s presence while still at the ward and time for discharge (items 5–21). There were 11 questions about social support and support from the mater-nity, child and patient health care systems after discharge (items 22–33) and 2 questions concerning expectations of support from infor-mation and communication technology (items

34–35). Using a 4-point response format, the women were also asked to assess the impor-tance of different modes of care and support. The possible categories were grouped as very important, fairly important, not particularly important and not important at all. For the question, “When should women be discharged from the maternity ward?” the selection alter-natives were after 6, 24, 48, 72 or 120 hours. For the information and communication technology question, “If videoconferencing (between the maternity ward and the patient’s home) were available, would this influence time of discharge from the maternity ward?” the response alternatives were “Yes” and “No.” Variables were rated on nominal, ordinal and ratio levels. The SSP is a validated, 91-item instrument divided into 13 scales and is used in studies that investigate the complicated relationship and interaction between individual differ-ences in personality and such biological bases as behaviour, affectivity and functioning (24). The present study utilizes three of the scales to investigate whether pregnant women living far from the hospital were more stressed than those living close by (e.g., were women participating in the study more stressed than the normative drawn sample which the instrument was eval-uated on?). This could have been a confounder when analysing the variable “distance to the hospital.” Somatic anxiety describes people who have psychological and somatic symp- toms, such as autonomic disturbance, restless-ness and tenseness. Psychic anxiety describes people who are sensitive and easily hurt and who worry, anticipate and lack self-confidence. Stress susceptibility describes people who are easily fatigued and who feel uneasy when they need to speed up (24). Statistical analysis SPSS® version 11.0 was the statistical software used to analyse the data. Descriptive statistics, such as frequencies and means, were calcu-lated. Cross tabulation with the chi-square test was used for dichotomous data and the Pearson product moment correlation was used to analyse correlations between the question-naire and the SSP instrument. A p value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically signif-icant. In Table I and II an overall p value is presented.

Validity and reliability

The questionnaire was developed by the inves- tigators, two of whom had experience in clin- ical maternity care (face validity). All inves-tigators had experience in research within the field (25). Studies concerning parental needs after childbirth (8,26,27) guided the development of the questionnaire, which was piloted by two newly delivered mothers and an external researcher before data collection. Three of the questions were reformulated in line with recommendations made by those participating in the pilot study (25).

The SSP instrument was evaluated in a normative, randomly drawn sample with inter-item correlations ranging from 0.17 to 0.43; Chronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.59 to 0.84 (24). The SSP instrument had been used earlier to investigate if traumatic birth experiences could have an impact on future reproduction (28), and to explore the relationship between hormones and personality traits in women after vaginal delivery or Caesarean section (29).

Ethical considerations

The women consented to participate as they voluntarily completed the questionnaire while

visiting the prenatal clinic. To ensure confi-dentiality, the participants were provided with stamped, addressed envelopes in order to mail the completed and anonymous question-naires directly to the primary investigator (IL). Approval for the study was obtained from the director of primary health care and the director of maternity care within the regional health authority and the Ethics Committee at Luleå University of Technology.

RESULTS

Demographic data, obstetrical history and personality

The mean age of the participants in the study was 29.2 years (primipara 27.1 years and multipara 31.4 years). The distance between the women’s homes and the nearest hospital with a maternity department ranged from <10 km up to 250 km, with a mean of 67.9

km (Md=65 km)

(Fig. 1). Among the women, 24.4% (primiparae 7.3%, n=9 and multiparae 17.1%, n=21) reported having had one miscar-riage or a stillborn child, 4.1% had had 2, and 6.5% of the women had had 3 or more miscar-riages/stillbirths.

No statistically significant differences were found in the analysis of the SSP instrument between women in this sample and the popula-tion in general, on which the SSP instrument is based. No correlations were found between the variables in the SSP instrument; somatic anxiety, psychic anxiety, stress susceptibility and the variables related to the “optimal time for discharge,” that is, “to stay as long as I want to,” “having the possibility of an early discharge” and “time for discharge.”

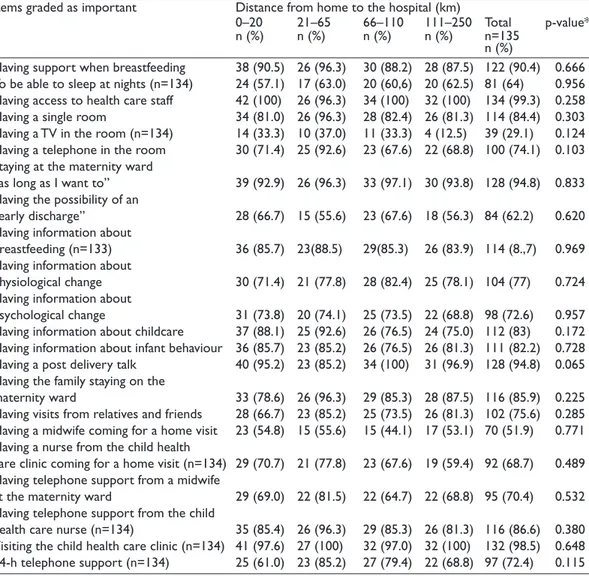

Distance and expectations of care

The variable “distance” (from the partic-ipant’s home to the closest hospital) was divided into quartiles, from the Md of 65 km

Figure 1. Distance between the women’s homes and the closest hospital with a maternity de-partment (n = 135).

(Table I). The result of item 17 shows that the majority of women (61.3%), irrespective of the distance from home to the hospital, wanted to be discharged 72 hours after the birth. A small proportion of women (19.0%) wanted to be discharged from the hospital 48 hours after childbirth (primiparae 20.8% and multiparae 17.9%), and 9.4% after 24 hours. Another

10.2% wanted to be discharged 120 hours after childbirth.

No statistically significant difference was found between women living more than 110 km from the hospital (fourth quartile) and those who lived closer, with regard to the impor-tance of variablesconcerning expectations of post-partum care support from the maternity,

Table I. Expectations of care in the post-partum period, estimated as important in relation to distance between home and

the delivery hospital (item 5–16 and 22–33).

Items graded as important Distance from home to the hospital (km)

0–20 21–65 66–110 111–250 Total p-value* n (%) n (%) n (%) n (%) n=135

n (%)

Having support when breastfeeding 38 (90.5) 26 (96.3) 30 (88.2) 28 (87.5) 122 (90.4) 0.666 To be able to sleep at nights (n=134) 24 (57.1) 17 (63.0) 20 (60,6) 20 (62.5) 81 (64) 0.956 Having access to health care staff 42 (100) 26 (96.3) 34 (100) 32 (100) 134 (99.3) 0.258 Having a single room 34 (81.0) 26 (96.3) 28 (82.4) 26 (81.3) 114 (84.4) 0.303 Having a TV in the room (n=134) 14 (33.3) 10 (37.0) 11 (33.3) 4 (12.5) 39 (29.1) 0.124 Having a telephone in the room 30 (71.4) 25 (92.6) 23 (67.6) 22 (68.8) 100 (74.1) 0.103 Staying at the maternity ward

“as long as I want to” 39 (92.9) 26 (96.3) 33 (97.1) 30 (93.8) 128 (94.8) 0.833 Having the possibility of an

“early discharge” 28 (66.7) 15 (55.6) 23 (67.6) 18 (56.3) 84 (62.2) 0.620 Having information about

breastfeeding (n=133) 36 (85.7) 23(88.5) 29(85.3) 26 (83.9) 114 (8.,7) 0.969 Having information about

physiological change 30 (71.4) 21 (77.8) 28 (82.4) 25 (78.1) 104 (77) 0.724 Having information about

psychological change 31 (73.8) 20 (74.1) 25 (73.5) 22 (68.8) 98 (72.6) 0.957 Having information about childcare 37 (88.1) 25 (92.6) 26 (76.5) 24 (75.0) 112 (83) 0.172 Having information about infant behaviour 36 (85.7) 23 (85.2) 26 (76.5) 26 (81.3) 111 (82.2) 0.728 Having a post delivery talk 40 (95.2) 23 (85.2) 34 (100) 31 (96.9) 128 (94.8) 0.065 Having the family staying on the

maternity ward 33 (78.6) 26 (96.3) 29 (85.3) 28 (87.5) 116 (85.9) 0.225 Having visits from relatives and friends 28 (66.7) 23 (85.2) 25 (73.5) 26 (81.3) 102 (75.6) 0.285 Having a midwife coming for a home visit 23 (54.8) 15 (55.6) 15 (44.1) 17 (53.1) 70 (51.9) 0.771 Having a nurse from the child health

care clinic coming for a home visit (n=134) 29 (70.7) 21 (77.8) 23 (67.6) 19 (59.4) 92 (68.7) 0.489 Having telephone support from a midwife

at the maternity ward 29 (69.0) 22 (81.5) 22 (64.7) 22 (68.8) 95 (70.4) 0.532 Having telephone support from the child

health care nurse (n=134) 35 (85.4) 26 (96.3) 29 (85.3) 26 (81.3) 116 (86.6) 0.380 Visiting the child health care clinic (n=134) 41 (97.6) 27 (100) 32 (97.0) 32 (100) 132 (98.5) 0.648 24-h telephone support (n=134) 25 (61.0) 23 (85.2) 27 (79.4) 22 (68.8) 97 (72.4) 0.115 * p values from Pearson chi-square when appropriate.

child and patient health care system (Table I). When controlling for age, parity and miscarriage/stillborn infants, with distance as the dependent variable, no statistically significant correlation between the above-mentioned groups was found.

Expectations of care in the maternity ward

Questions using attitude scales were dichot-omized by merging the “very important” and “fairly important” responses with “impor-tant,” and the “not particularly important” and “not important at all” responses with “not important.” When ranking expecta-tions as important, “the wish to have access to staff on the maternity ward” received the highest percentage (99.3%). Other expecta-tions graded as important were “to stay as long as I want to” (94.9 %), to have a post-delivery talk (95%), to have support during breastfeeding (90.6%), to have the family staying on the maternity ward (86.3%), to have a room for oneself (84.9%), and to have information about breastfeeding (85.4.8%), infant behaviour (82%) and childcare (82.7%). The opportunity to have an “early discharge” was considered important by 61.2 % of the women; to have a “TV in the room” during their stay on the maternity ward was considered important by only 28.3% (Table II).

There was a statistically significant differ- ence where primiparae graded the expecta-tions on care more important than multiparae in the variables “having information about breastfeeding” (p=0.001), “having informa-tion about physiological change” (p=0.000), “having information about psychological change” (p=0.000), “having information

about childcare” (p=0.014), having infor-mation about infant behaviour” (p=0.002), “having the family staying on the maternity ward” (p=0.006), “having a midwife coming for a home visit” (p=0.000), “having a nurse from the child healthcare clinic coming for a home visit” (p=0.005), “having telephone support from a midwife at the maternity ward” (p=0.001) and ”having telephone support from the child healthcare nurse” (p=0.036) (Table II). In the variable “having the possibility of an early discharge,” multi-parae graded the importance higher than primiparae. However, both primiparae and multiparae graded “to have the opportunity to stay on the maternity ward as long as you want” equally important at 96.3% and 94% (p=0.557), respectively.

Expectations of care after discharge from the maternity ward

The expectation of “continued contact with the maternity ward staff,” (“having home visits” and “telephone support”), as well as support from the child health care clinic also generated higher statistical significance among primiparae (Table II).

Expectations of home visits and telephone support from child health care staff during the post-partum period was graded by all women as more important than continued contact with maternity ward staff. Visiting the child health care centre was rated highly, with 100% of primiparae and 97.6% of multiparae considering such a visit important. The majority of women valued 24-hour tele-phone support as important (72.5%) (Table II). A small proportion (15.1%) believed that “using picture and sound in contact with the midwife on the maternity ward” (known

as telemedicine) was expected to influence their choice of when to be discharged from the maternity ward, but only 25.9% showed interest in such a technology.

People who are expected to be

important during the post-partum period

The results of items 22–26 show that the infant’s father was expected to be the most impor-tant person for maintaining social contacts (98.6%), caring for the baby (98%), supporting

the mother’s psychological adjustment (95.7%), supporting the mother’s physical adjustment (92%) and supporting breastfeeding (87.9%). The health care staff was expected to be impor-tant for supporting breastfeeding (77.9%), supporting parents caring for their baby (64.3%) and supporting the mothers’ physical adjustment (53.6%). Relatives were expected to be important for maintaining social contact (96.4%) and for supporting mothers’ psycho-logical adjustment (65.0%).

Table II. Comparisons between the expectations of primiparae and multiparae regarding care in the post-partum period,

graded as important while being cared for on the maternity ward (item 5–16 and 22–33).

Items graded as important Primiparae, Multiparae, Total p value*

n=54 n=85 n=139

n (%) n (%) n (%)

Having support when breastfeeding 51 (94.4) 75 (88.2) 126 (90.6) 0.220 To be able to sleep at nights (n=138) 32 (59.3) 52 (51.1) 84 (60.9) 0.756 Having access to health care staff 54 (100) 84 (98.8) 138 (99.3) 0.424

Having a single room 49 (90.7) 69 (81.2) 118 (84.9) 0.125

Having a TV in the room (n=138) 15 (27.8) 24 (28.6) 39 (28.3) 0.920 Having a telephone in the room 35 (64.8) 65 (76.5) 100 (71.9) 0.136 Staying at the maternity ward

“as long as I want to” (n=138) 52 (96.3) 79 (94.0) 131 (94.9) 0.557 Having the possibility of an “early discharge” 26 (48.1) 59 (69.5) 85 (61.2) 0.012 Having information about breastfeeding (n=137) 52 (98.1) 65 (77.4) 117 (85.4) 0.001 Having information about physiological change 50 (92.6) 57 (67.1) 107 (77.0) 0.000 Having information about psychological change 49 (90.7) 52 (61.2) 101 (72.7) 0.000 Having information about childcare 50 (92.6) 65 (76.5) 115 (82.7) 0.014 Having information about infant behaviour 51 (94.4) 63 (74.1) 114 (82.0) 0.002 Having a post delivery talk 50 (92.6) 82 (96.5) 132 (95.0) 0.308 Having the family staying on the maternity ward 52 (96.3) 68 (80.0) 120 (86.3) 0.006 Having visits from relatives and friends 41 (75.9) 64 (75.3) 105 (75.5) 0.933 Having a midwife coming for a home visit 39 (72.2) 34 (40.0) 73 (52.5) 0.000 Having a nurse from the child health care clinic coming

for a home visit (n=138) 45 (83.3) 51 (60.7) 96 (69.6) 0.005 Having telephone support from a midwife at the

maternity ward 47 (87.0) 51 (59.9) 98 (70.5) 0.001

Having telephone support from the child health care

nurse (n=138) 51 (94.4) 69 (82.1) 120 (87.0) 0.036

Visiting the child health care clinic (n=138) 53 (100) 83 (97.6) 136 (98.6) 0.261 24-h telephone support (n=138) 44 (54.0) 56 (66.7) 100 (72.5) 0.057 * p values from Pearson chi-square when appropriate.

DISCUSSION

The main findings in this study are that 61.3% of the women wanted to be discharged 72 hours after childbirth, regardless of the distance between the hospital and home. To have access to maternity ward staff and the ability to decide when to be discharged were expected to be the most important issues in maternity ward care The infant’s father was expected to be the most important person in the post-partum period.

The overall finding in this study has to be considered partly in light of the fact that the area investigated, the northernmost county in Sweden, faced a reduction in the number of maternity clinics from 5 to 2 just prior to the start of our study, and partly in light of the ensuing media debate on the topic. One can speculate on the consequences the negative media dispute had on the expecta-tions of the women in our study, with special regard to post-partum care and any increased distance to a maternity clinic, but also on some of those women who lived closest to the clinics that were closed. It may also be that evaluating post-partum care as a part of childbirth does not depend on the distance expecting parents must travel to reach the maternity unit. The distance between the home and clinic might only be considered important regarding the actual labour and delivery. Despite the rather small sample, a high proportion of women responded rela-tive to the total number of available preg-nancies, and our sample population covered the entire county, including both densely and sparsely populated areas.

Our findings, that a large proportion (61.3%) of the women did not want to be

discharged any earlier than 72 hours after childbirth, differ from the findings in a recent study of women in a large city in Sweden (30), in which 72% of the women wanted to be discharged by the 72 hours or sooner. Although early discharge in Sweden is well known and well established within the health care system (1), women in this specific geographic area are not prepared to be discharged within the limit of 72 hours set for early discharge. One expla-nation could be a general unwillingness of the parents to return to the hospital after discharge for the phenylketonuria (PKU) test and a second paediatric examination. Within this specific county, it is still routine for infants to undergo a second examina-tion by a paediatrician, usually performed at the same hospital where the child was born (Norrbottens county council, 2006, personal communication). A change in prac-tice designed to provide the PKU test and second paediatrician exam in a community setting would perhaps encourage families to take an early discharge. To ave access to caring staff as well as to have information and support were ranked as important. Several studies of women’s expe-riences in post-natal care point out the strong need for emotional, physical and practical support (11,31,32), especially in conjunction with short hospital stays. Another impor-tant, highly ranked issue was the desire women had to decide for themselves when they should be discharged. This could be seen as a strategy for maintaining control over different options within post-partum care. In a study measuring the outcome of early discharge versus hospital post-partum care, Waldenström (4) and Fredriksson et

al. (12) found that in order to have a positive outcome, parents had to be offered a choice of care alternatives.

Variables concerning information, breast-feeding and infant support were also highly valued and in agreement with the findings of Smith (9), Proctor (13) and Emmanuel et al. (33), whose studies found that support and practical assistance related to care of the infant and breastfeeding were the most frequently identified concerns. Likewise, our results do not support those posted by Ruchala (34), who found that during the first 5 days after childbirth, mothers wanted to learn more about caring for their own needs rather than learning to care for the infant.

As in previous studies (35–37), we found that the infant’s father was rated as the most important person in the post-partum period after leaving the maternity ward. This finding is supported by Barclay and Lupton (38) who state that men in Western society are expected to fill the gap between close relatives and the new mother and have to take on the role as provider, guide, household helper and nurturer. Even among people who are impor-tant for support in breastfeeding, the infant’s father was more highly ranked (87.9%) than health care professionals (77.9%). These find-ings can partly be explained by the findfind-ings of Humphreys et al. (39) and Ingram et al. (36) who reported that the attitude of health profes-sionals to women’s decisions about the care for herself and the baby was less influential than the attitudes and beliefs of members of the women’s social network. One explanation may be that within this specific geographic area with its long distances to the maternity department, the presence of the infant’s father is expected to be even more important than

receiving support from health care profes-sionals.

In our study, the partners of the partici-pants were not asked for their opinion, which is, of course, a limitation and might have provided alternative points of view that would have enriched the study. The social debate concerning the importance of the father’s presence for the growing child/family has led to fathers now making their own demands on post-partum care (40,41). Since the result of the SSP indicates no differences between our sample and the population in general, the difference between our result and those found in other studies probably does not reflect personalities, but rather life as it is lived in this particular geographical part of the country.

Few women indicated that the expectation of having access to technical solutions in order to complement the early-discharge system would affect their attitude towards time of discharge. This answer most likely reflects their lack of present knowledge concerning telemedicine as a complement within the health care system.

Conclusions

In this study, distance was not found to be a determining factor in estimating either the length of the hospital stay or the post-partum care expected. It seems that it was more important for new mothers to have the oppor-tunity to decide for themselves when to be discharged from the maternity ward, which can be interpreted as a strong signal that women want to be in control of the care they receive. Implications for midwives include focusing more on the woman and her family’s individual needs when developing midwifery care in the maternity ward.

In the results, the father/partner was expected to be the most important person in the post-partum period. This indicates the need to acknowledge and recognize his presence in the maternity ward and in the post-partum period. Midwives have to include fathers as individuals with resources and with their own needs for support. Further research is needed to determine the role of fathers in the post-partum period.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our thanks to the Department of Health Science and the Centre for Distance-Spanning Healthcare, at Luleå University of Technology. We also would like to express our appreciation to the midwives for collaborating with us and to the participating women for their willingness to share their expectations.

REFERENCES

1. Brown S, Small R, Faber B, krastev A. Davis P. Early discharge from hospital for healthy mothers and term infants (Cochrane Review). Wiley, Chichester: The Cochrane Library; 2002 Issue 3:1-30.

2. Brown S, Lumley J, Small R. Early obstetric dis-charge: does it make a difference to health out-comes? Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 1998;12:49–71. 3. Ellberg L, Lundman B, Persson MEk, Högberg U.

Comparison of health care utilization of postnatal programs in Sweden. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2003;34:55–62.

4. Waldenström U. 1987 Early discharge after hospital birth. Medical dissertation no.79, Uppsala: Uppsala University; 1987. 1-VII:3

5. Molin R, Johanson L. Department of Policy on Health Care of the Swedish Federation of County Councils; 2004. Swedish health care in transition. Resources and results with international comparisons [cited 2008 May 12]. Available from: http://www.equip.ch/ flx/national_pages/sweden/

6. National Board of Health and Welfare. SOS report Handling the normal birth. State of the Art (Han-dläggning av normal förlossning, in Swedish). Stock-holm: The National Board of Health and Welfare; 2001–123–1.

7. National Board of Health and Welfare SOS-report Description of registered midwives competence (kompetensbeskrivning för legitimerad barnmor-ska). Stockholm: The National Board of Health and Welfare; 2006–105–1. [in Swedish]

8. Nyberg, k, Bernerman-Sternhufvud L. Mothers’ and fathers’ concerns and needs postpartum. British Journal of Midwifery 2000;8:387–394.

9. Smith MP. Postnatal concerns of mothers: an update. Midwifery 1989;5:182–188.

10. Stainton C, Murphy B, Grant Higgins P, Neff JA, Ny-berg k, Ritchie JA. The needs of postbirth parents: an international, multisite study. J Perinat Educ 1999; 8:21–29.

11. Persson Ek, Dykes A-k. Parent’s experience of ear-ly discharge from hospital after birth in Sweden. Midwifery 2002;18:53–60.

12. Fredriksson GEM, Högberg U, Lundman BM. Post-partum care should provide alternatives to meet parents´ need for safety, active participation and ‘bonding’. Midwifery 2003;19:267–276.

13. Proctor S. What determines quality in maternity care? Comparing the perceptions of childbearing women and midwives. Birth 1998;25:85–93. 14. Singh D, Newburn M. Postnatal care in the month

af-ter birth. Pract Midwife 2001;4:22–25.

15. Stevens T, McCourt C. One-to-one midwifery prac-tice. Part 3: meaning for midwives. British Journal of Midwifery 2002;10:111–115.

16. Turnbull D, Reid M, McGinley M, Shields NR. Chang-es in midwivChang-es’ attitudChang-es to their profChang-essional role following the implementation of the development unit. Midwifery 1995;11:110–119.

17. Bondas-Salonen T. New mothers’ experience of post-partum care: a phenomenological follow-up study. J Clin Nurs 1998;7:165–174.

18. Larkin M. E-health continues to make headway. J Lan-cet 2001;358:517.

19. Elliot-Schmidt R, Strong J. The concept of well-being in a rural setting: understanding health and illness. Aust J Rural Health 1997;5:59–63.

20. Hemard JB, Monroe PA, Atkinson ES, Blalock LB. Rural women´s satisfaction and stress as family gate keepers. Women Health 1998; 28:55–75.

21. Holt JJ, Vold IIN,Backe BB, Johansen MMV, Oian PP. Child births in a modified midwife managed unit: se-lection and transfer according to intended place of delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2001;80:206– 212

22. County Administrative Board of Norrbotten. Facts about Norrbotten 2004 [Länsstyrelsen Norrbotten. 2004 Fakta om Norrbotten] [cited 2008 May 12]. Available from: http://www. regionfakta.com/tem-plates/Page.aspx?id=17510.

23. kerlinger FN. Lee HB. Foundations of Behavioural Research (4th ed). Orlando: Harcourt College Pub-lishers; 2000. 1-890.

24. Gustavsson JP, Bergman H, Edman G, Ekselius L, von knorring L, Linder J. Swedish universities’ scales of personality (SSP): construction, internal consistency and normative data. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000;102: 217–225.

25. Polit DF. Beck BP. Nursing research: principles and methods (7th ed). Philadelphia: Lippincott; 2004. 1-758.

26. Bennett RL, Tandy LJ. Postpartum home visits: ex-tending the continuum of care from hospital to home. Home Healthc Nurse 1998;16:295–303. 27. Ruchala PL, Halstead L. The postpartum experience

of low-risk women: a time of adjustment and change. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 1994;22:83–89. 28. Gottvall k, Waldenström U. Does a traumatic birth

experience have an impact on future reproduction? BJOG 2002;109:254–260.

29. Nissen E, Gustavsson P, Widström AM, Uvnäs-Mo-berg k. Oxytocin, prolactin, milk production and their relationship with personality traits in women after vagina delivery or Caesarean section. J Psycho-som Obstet Gynaecol 1998;19:49–58.

30. Ladfors L, Eriksson M, Mattsson L-Å, kylebäck k, Magnusson L, Milsom I. A population-based study of Swedish women’s opinions about antenatal, delivery and postpartum care. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2001;8:130–136.

31. Ockleford EM, Berryman JC, Hsu R. Postnatal care: what new mothers say. British Journal of Midwifery 2004;12:166–170.

32. Tarkka M-T, Paunonen M. Social support provided by nurses to recent mothers on a maternity ward. J Adv Nurs 1996;23:202–206.

33. Emmanuel E, Creedy D, Fraser J. What mothers want: a postnatal survey. Aust Coll Midwives Inc J 2001;14:16–20.

34. Ruchala PL. Teaching new mothers: priorities of nurses and postpartum women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2000;29:265–273.

35. Ekström A, Widström AM, Nissen E. Breastfeeding support from partners and grandmothers: percep-tions of Swedish women. Birth 2003;30:261–266. 36. Ingram J, Johnson D, Greenwood R. Breastfeeding in

Bristol: teaching good positioning, and support from fathers and families. Midwifery 2002;18:87–101. 37. Tarkka M-T, Paunonen M, Laippala P. What

contrib-utes to breastfeeding after childbirth in a maternity ward in Finland. Birth 1998;25:175–181.

38. Barclay L, Lupton D. The experiences of new father-hood: a socio-cultural analysis. J Adv Nurs 1999;29: 1013–1020.

39. Humphreys AS, Thompson NJ, Miner kR. Intention to breastfeed in low-income pregnant women: the role of social support and previous experience. Birth 1998;25:169–174.

40. Olin R-M, Faxelid E. Parents need to talk about their experiences of childbirth. Scan J Caring Sci 2003;17: 53–59.

41. Sörensen L, Hall EOC. Resources among new moth-ers: early discharged multiparous women. Vard Nord Utveckl Forsk 2004;24:20–24.

Inger Lindberg, RNM, MSc Division of Nursing

Department of Health Science Luleå University of Technology SE 971 87 Luleå

SWEDEN