J

Ö N K Ö P I N GI

N T E R N A T I O N A LB

U S I N E S SS

C H O O LJÖNKÖPING UNIVERSITY

R e g i o n a l Va r i a n c e i n S i c k n e s s

I n s u r a n c e U s a g e

Paper within Economics

Author: Andreas Kroksgård

Tutor: Associate Professor Johan Klaesson Ph.D. Candidate Hanna Larsson Jönköping May 2009

Master Thesis in Economics

Title: Regional Variance in Sickness Insurance Usage Author: Andreas Kroksgård

Tutors: Associate Professor Johan Klaesson and Ph.D. Candidate Hanna Larsson

Date: May 2009

Subject terms: Health, sickness absence, sickness compensation, labor mobility, firm structure, regional variance, social insurance, regional variance, regional analysis, ill health, Sick-pay insurance, work absence, moral hazard, social norms.

JEL Codes: I10, I11, I18, I38, L51, J22, Z13

---

Abstract

Which factors best explain the regional variation in sick-listing and early retirement? Data from the Swedish Social Insurance Agency is fitted against variables describing different regional characteristics that have been linked to sickness insurance consumption in the literature. Results, in line with earlier empirical investigation, suggest that particularly the employment rate, the populations‟ age, and its wealth are strong determinants of regional insurance usage. Two further factors, though less discussed in the literature, appear to have some relevance as well: A high share of large workplaces is found to predict higher rates of early retirement, while a large share of foreign-born predict lower sick-listing rates. Both effects have been found before, though the first one perhaps not in Swedish cross section analysis and the latter does not appear to be well understood in the literature. A tentative explanation for it is given here.

Explanation of terms used in thesis

Sickness withdrawal [Total] Sickness Insurance Usage ([T]SIU) Sickness absence* Sick-listed* Early retiredSick pay [Sjuklön]

Sickness benefit [Sjukpenning] Activity compensation [Aktivitetsersättning] Sickness compensation [Sjukersättning]

People of working age choosing not to appear at work, or to withdraw entirely from the labor force, due to reported sickness. Covers all the individuals in the categories: sickness absence, sick-listed and early retired. The concept of „sickness withdrawal‟ is novel, as far as I know, though is similar to the concept of “withdrawal behavior” used in the field of applied psychology.

People of working age receiving sickness insurance due to being sick-listed or early retired. SIU refers to usage in either form, while TSIU is the total (of sick-listing and early retirement).

Employees absent from work with sickness reported as the reason for this. (Measured by polls).

People of working age receiving „sickness benefit‟

People of working age with „activity compensation‟ or „sickness compensation‟.

If you are employed and fall ill, you must report sick to your employer. If you are employed for at least a month or have worked for fourteen consecutive days, you are entitled to sick pay from your employer for the first 14 days of your illness. No payment is made for the first day (the “waiting period”). If you are still ill after 14 days, your employer will notify the Swedish Social Insurance Agency (Försäkringskassan) of your illness. When you are well again, you must provide your employer with written assurance that you have been ill and specifying the extent of your absence from work.*

If you are employed, you can obtain sickness benefit when you no longer receive sick pay [sjuklön] from your employer, i.e. if you are ill for a longer period than 14 days. If you do not receive sick pay from your employer, you may be entitled to sickness benefit from the beginning of the sickness period. You can receive sickness benefit from the beginning of the sickness period if you are: self-employed,

unemployed, on parental leave, or on leave with pregnancy benefit [havandeskapspenning].*

If you are aged between 19 and 29, you may be eligible for activity compensation if your work capacity is reduced by at least a quarter for at least a year. You may have full, three-quarter, half or a quarter activity compensation, depending on how much your work capacity is reduced and your ability to support yourself through work.*

If you are aged between 30 and 64, you may be able to receive sickness compensation if your work capacity is permanently reduced by at least a quarter. You may have full, three-quarter, half or a quarter activity compensation, depending on how much your work capacity is reduced and your ability to support yourself through work. *

Notes: Not all sickness absentees are sick-listed and not all sick-listed are sick absent, but there is considerable overlap (Farm & Rennermalm, 2003). Passages marked with “*” are quoted from the Swedish Social Insurance Agency. The exact documents quoted are internet sources 1 & 2 (see bibliography).

Table of Contents

1

Introduction ... 1

2

Theoretical framework ... 4

2.1 Understanding the regional variance in SIU ... 9

2.2 Earlier research on regional variation in SIU in Sweden ... 12

3

Dependant variables ... 13

4

Methodology ... 15

5

Limitations ... 16

6

Results... 17

7

Conclusions ... 21

8

Bibliography ... 23

Figures, Tables, and Appendices

Figures Figure 1-3 Regional Sick-Listing, Early Retirement, and TSIU………... 3Figure 4 Social determinants of health……….. 10

Figure 5 Sick days per employee and year, 1993-2001………. 20

Tables Table 1 Results………. 17

Appendices Appendix A Definitions, expectations and descriptive statistics... 25

Appendix B Pairwise correlations... 27

Appendix C Sick-Listing per Worker (SLPW) regression models………. 28

Appendix D Share of Population in Early Retirement regression models…….. 29

Appendix E Total Sickness Insurance Usage (TSIU) regression models……… 30

Appendix F the optimal Total Sickness Insurance (TSIU) model in detail……. 31

Appendix G Scatter plot of „optimal‟ TSIU model……….. 32

Appendix H Estimates found in earlier studies of regional SIU variation... 33

1

Introduction

A central factor for a country‟s economic growth is that a large share of its population is working. A problem for Sweden in this respect is the comparatively high rate of sickness withdrawal1. Recent international comparisons show that Sweden has Europe‟s highest sickness absence (see e.g. Palmer, 2005; Rae, 2005). Compared to similar countries Sweden also compensates a relatively large share of its population for early withdrawal from the labor market (early retirement). More than every tenth person of working age has left the labor force to early retirement in Sweden in recent years. In the other Nordic countries (except for Norway) the shares are lower, among 7-8 percent (Swedish Social Insurance Agency 2008a).

Sick-listing and early retirements are expensive for the society. The total cost, counted as

production loss (cost of illness), for the latest year with complete statistics of total sickness

insurance usage (TSIU) in Sweden i.e. 19912 was estimated to 136 billion SEK3, or 179 B SEK (by today‟s price level4

). A very rough estimate of the current (2009) cost of illness per working age person (20-64) in Sweden would then be 179 B / 5.437 M = 33 000 SEK. The initial 136 B figure was estimated by the reduction in production capacity (labor supply) of the working age population due to sickness. It seems likely that the true costs are even higher. There are four main channels by which the health status of individuals is believed to affect the economy of countries, it is expected to decrease/worsen of course: (1) labor productivity; and (2) labor supply; but also, slightly less obvious: (3) education; and (4) savings and investment. (See Suhrcke et al 2006, for empirical evidence and theory supporting these expectations).

One way of finding factors that affect the rate of sickness withdrawal is through cross-sectional analysis; this is the method that will be used in this thesis. The data that will be analyzed is sickness insurance usage (SIU) data from the Swedish Social Insurance Agency.

There is an ongoing discussion about how to explain the great regional variance in sickness insurance usage (SIU) in Sweden5. To be more precise, the discussion is about how to explain that part of the regional variance that is not already explained by known factors. The age structure for example varies across regions, and some of the variance in SIU can be explained by this factor. However, “there are no statistics indicating big regional differences in general health or working environments – neither now nor earlier – while we observe significant and longstanding regional differences in sickness insurance usage.” (Palmer 2006, p. 52) This has led many to believe that regional differences in attitudes or cultures explain part of the variance in SIU6.

This aim of this thesis however, is partly about testing a rather new hypothesis7 for the regional variance in SIU. The hypothesis is that labor mobility is good for workers health,

1

See page ii above: Explanation of terms used in thesis

2 Employer‟s responsibility to pay „sick wage‟ (sjuklön) for first two weeks of the sick spell, initiated in 1992 meant incomplete statistics over sick spells for the Social Insurance Agency after this date.

3 SBU (2003) page 46

4 136 billion SEK in 1991 equals 179 billion SEK in May 2009 (adjusting for the CPI) according to Statistics Sweden‟s web tool: „Prisomräknaren‟

5 For an overview skip to page 3

6 The Swedish Social Insurance Agency for example, published an over 600 pages long anthology into this matter in 2006, finding some support for the „attitudes explanation‟. (Included in the bibliography)

and that this will be reflected in regional SIU rates. A connected and more general aim of

the thesis is to see which variables, out of 18 selected, best explain the regional variance in 1) sick-listing, 2) early retirement, and 3) Total Sickness Insurance Usage (TSIU). TSIU is the label I have chosen for the sum of sick-listing and early retirement. It is sometimes called “ill health” in the literature, perhaps because that is a close translation of its Swedish term “Ohälsotalet”. I choose to call it TSIU since it appears a more accurate description, it cannot possibly be more than a proxy of the true “ill health” of the population, while it is exactly the sickness insurance usage of the population.

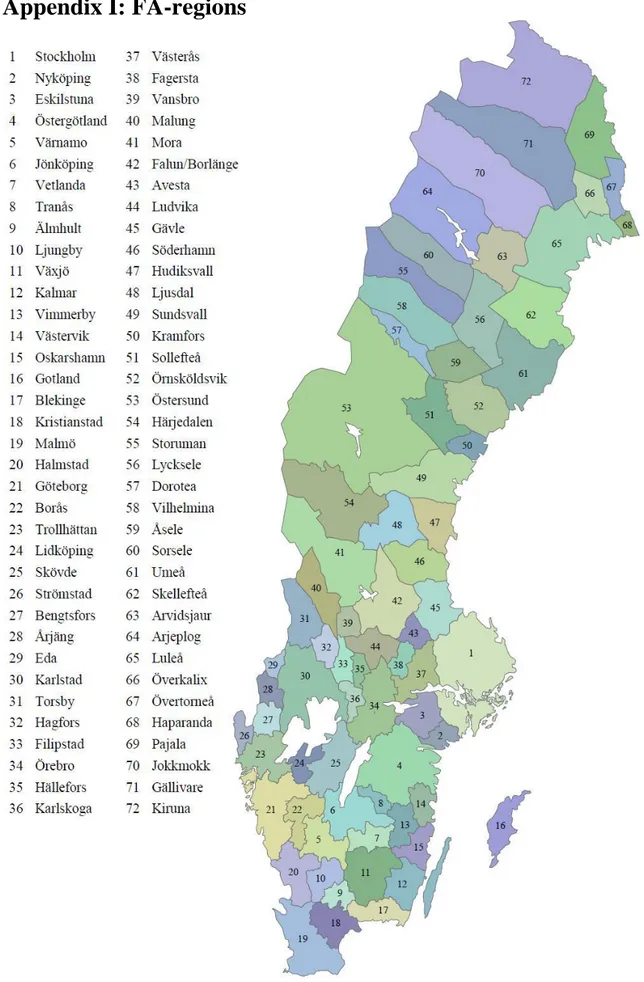

The method chosen for testing the labor mobility hypothesis and the more general aim of the thesis has been decided by the data available to me. I have labor mobility data only for Swedish FA-regions, which decides the units of observation. To make a serious test of the labor mobility hypothesis, other (confounding) variables known to affect regional sickness compensation rates needs to be controlled for. Therefore the literature on regional variance in sickness insurance compensation needs to be considered, what is known about this subject?

In a recent, and often quoted, “systematical literature overview” by The Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care (SBU) concerning sick-listing and early retirement, the following sobering conclusions were made about our current knowledge on sickness absence, sick-listing, and early retirement:

Despite the extent of sickness absence and its great consequences for society, and possibly for the individual, knowledge as to its causes and how these could be affected are very limited … The research area is theoretically, methodologically, and conceptually undeveloped… Overall there are surprisingly few studies concerning the underlying causes of sickness absence… and extremely few of high methodological quality… Several of the various hypothesis regarding sickness absence and early retirement that are being discussed in different milieus lack scientific evidence…The field needs to be developed! (SBU 2003, p 17-18)8

On the next page are figures (1, 2, & 3) they are a visual representation of the problem at hand, how can we explain these large regional differences in sick-listing, early retirement and TSIU? A positive fact that is visible in figure 3 (if one is familiar with the Swedish population distribution) is that the darker regions, where TSIU per capita is high, are sparsely populated. This means that the most „expensive‟ regions – those that receive the most sickness insurance per capita – do not add much cost to the TSIU of the nation. The total working age population (20-64) of the 30 regions whom had more than 50 yearly net days of TSIU per insured averaged 363 thousand in the period measured, to be compared with a total working age population of about five million in the 42 regions whom had an average rate of TSIU below 50 net days per insured.

Implicit in this attempt to explain the regional variation in SIU is the assumption that people don‟t apply for sick-listing or early retirement in a vacuum. Regional characteristics will affect the probability that its average inhabitant receive some form of sickness insurance. For example; the average individual in each region will first of all want to get some form of sickness insurance if he is sick. We should therefore expect the average individual in a region where many people are old to be more likely to be sick and therefore more likely to need sickness insurance. But we expect other characteristics of the region to

matter as well. In the theoretical section, an attempt will be made to better understand what regional characteristics can be assumed to matter - and why.

Figure 1: Regional

Sick-Listing per worker (net days) (2003-2007 yearly average)

Figure 2: Early Retired

per 20-64 year old (2003-2007 yearly average)

Figure 3: TSIU (net

days) per insured 16-64 year old (2003-2007 yearly average)

The structure of this thesis will be as follows. In section 2 theory on the subject of health and sickness insurance usage is presented. First in general way, followed by what the literature has to say on the regional variance of sickness insurance usage. By the end of section 2 we close in on some independent variables that, according to the literature, should be linked to sickness insurance usage. A „base model‟ is presented. Note that all independent variables tested that mentioned in the text are described in Appendix A. The idea is that the rationale for the types of independent variables chosen for testing should be understood from the text. In section 3 the dependant variables are explained in more detail. Section 4 details the method chosen for the assessment of which variables are relevant in explaining the variance in sickness insurance consumption. Some limitations of the thesis are mentioned in section 5. Finally, in section 6 and 7 the results and conclusions of the thesis are found.

2

Theoretical framework

“Research on causes of sick-listing is done within many disciplines and it would be close to impossible to combine knowledge and theory from all the different sciences; medical, psychological, sociological etc. to one overall theory of causes for sick-listing” (SBU,

2003, p. 74).

Hoping for an „overall theory‟ of sick-listing or sickness withdrawal is likely to lead to despair. Sickness withdrawal is likely to have many underlying causes; medical, cultural, economical. One of the underlying causes of sickness withdrawal is health, let‟s begin there.

In the public health literature, the concept and importance of control seems to be more and more recognized as a major explanatory factor of health differences. Marmot‟s (2004) book: „The status syndrome: how social standing affects our health and longevity‟ showed that a social gradient in health is a widespread phenomenon. Statistics show (apparently pretty much whenever and wherever you look), that “health follows a social gradient: the higher the social position, the better the health… It runs from the top to the bottom of society, with less good standards of health at every level down the social hierarchy.” The social health gradient was first observed by Marmot through his famous „Whitehall studies‟ of British civil servants. A seemingly homogenous group: “It does not contain the richest or the poorest in the country; no one has a private jet and no one is unemployed or unthinkable for employment. All have great job security.” Still “the fact that civil servants in the second grade from the top have worse health than those at the top shows that we are dealing not only with the effects of absolute deprivation. Rather position in the hierarchy is important. This suggests some concept of relative rather than absolute deprivation… a psychosocial concept.”

In „The status syndrome‟ Marmot develop arguments for the importance of control and

social participation: “the degree of control you have over your life and the opportunities

you have to fully participate in society will strongly predict your health, your life quality and your longevity.” But Marmot cannot be blamed for focusing too much on too few causes of health. In a later (2006) book, he writes that “the social gradient has shown us how sensitive health is to social and economic factors, and so enabled us to identify the determinants of health among the population as a whole” (quotes from Marmot 2004, p. 58-59, 246 & 2006, p. 2, 6). Later in this paper (p. 13) a most helpful model of the social determinants of health is presented.

A brief overview of theories used in different scientific fields to understand health or sickness withdrawal will be given here9, followed by an attempt to establish a framework for thinking about regional variances in SIU.

A model that has been of central importance in the field of psychology

Sickness absence in this field has often been analyzed together with other forms of “withdrawal behaviors” such as quitting work (“turnover”) or late arrival (“tardiness”). These withdrawal behaviors have often been ranked, with tardiness as the mildest form and turnover the most extreme. These different forms of withdrawal have been viewed as consequences of low job satisfaction. A large empirical literature has tried to establish the

connection between job satisfaction and withdrawal - without much success. (SBU 2003 p75)

A model used in the field of sociology

A theory best placed in this field of research is that of a „culture of absence‟, which has been defined, by Chadwick-Jones et al (1982) as “…beliefs and practices influencing the totality of absences – their frequency and duration – as they currently occur within an employee group or organization.” The culture of absence theory links actual absence to common perceptions regarding absence within different groups; such as: what are the legitimate grounds for absence, how long should a “reasonable” absence spell be, and so on and so forth. Operationalization10 and measurement of absence cultures are difficult, and the empirical literature on the topic is therefore limited (SBU 2003 p. 77-8)

Stress theories

“Decades of research in sociology and psychology have demonstrated that a sense of control of life in general is a robust predictor of physical and mental well-being”

(Toivanen 2007)

Unlike psychological and economical theories (which will be referenced shortly) stress theories have more of an interdisciplinary character, with important contributions from the medical, sociological, and psychological fields. These theories tend not to focus on absence but on sickness generally. A large share of the research has been on medical problems linked to stress, such as cardiovascular diseases and the more psychological symptoms of anxiety and depression. To varying degrees these theories propose different causal chains leading to sickness absence, it is for example suggested that stress affects the employees motivation to work, or that sickness absence is used as a method of stress control. (SBU 2003, p. 80)

Concerning the work situation it is “without a doubt” Karaseks “demand-control” theory that has garnered the most attention and generated the most empirical research. According to this theory it is particularly jobs that combine high demands with low control that have negative health consequences, these jobs are referred to as “high-strain”. (SBU 2003, p. 80) The critical argument that is made clear in Marmot (2004) is that once people pass a certain minimum level of material well-being (as in Sweden) – another kind of well being is more central: “Autonomy…and the possibilities we have for full social engagement and participation is of decisive importance for health… It is inequalities within these areas that have great importance for creating the social health gradient. Behind the status syndrome is the degree of control and participation.”

Another example of a stress theory is that of “Person Environment Fit” where stress is defined as a lack of fit, or poor interplay, between the person and the environment. A third example is the “Effort-Reward Imbalance” theory which is rather self-explanatory. (SBU 2003, p. 81)

10 Operationalization is the process of defining a fuzzy concept so as to make the concept measurable in form of variables consisting of specific observations. In a wider sense it refers to the process of specifying the extension of a concept. (Wikipedia)

Medical explanatory models

Medical evaluations are fundamental in the sickness insurance process. A doctor decides both if a person „really‟ is sick, and whether it means a reduction in work capacity for the individual, which is a criterion to be eligible for sickness insurance. Sick-listing can be viewed as a certificate that the patient has a reduced work capacity, it can also be seen as an ordination or prescription, where sickness absence is ordered or prescribed on the assumption that continued work may worsen or prolong the sickness spell. In some cases the doctor may order sick-listing primarily to protect the patient‟s surroundings, as would be the case if the patient had an infectious disease. (SBU 2003, p. 82)

“During the last 40 years, especially during the periods when sickness absence has increased, doctor‟s sickness certification practice have been discussed and even mentioned as causing the increase in sickness absence…It is often asked if doctors have the right, or sufficient education for this task.” (SBU p. 23) An open question is how much the view on the very concept of sickness varies between doctors and within the public, over time and within groups. These kinds of questions are dealt with by for example the historical and philosophical sciences (and will not be further considered in this thesis). (SBU 2003, p. 83)

Economical and rational choice theories

Worker absence due to illness is not something economists have been terribly interested in, causes of absence from work in general is more studied, but then theory is often formed only to explain the part of absence that is unrelated to sickness, that is, that part of all absence that may be considered a result from rational choices made by healthy employees from a utility maximization perspective (SBU, 2003). In a stylized way, one could say that economists have tended to ask: why do people go to work at all? While for example psychologists have asked: why don‟t people go to work?

Economical theories on sickness absence usually take as their starting point the assumption of persons being rational actors, seeking to maximize personal welfare or “utility”. Personal utility is seen as a function of consumption (demanding time at work) and leisure (time off work). In the simplest version of this model zero absence compensation is assumed. Utility is then maximized for a certain distribution between consumption and leisure; deciding the amount of „sickness‟ absence11

. It follows from the model that „sickness‟ absence will increase with increased contractual hours of work. An increased wage will have two offsetting effects, a person‟s leisure (time off work) will be more „expensive‟ (greater alternative costs through the “income effect”), but with a higher wage a person will also be able to work less for the same amount of consumption as when the wage was lower (the “substitution effect”).

This simple model has then been expanded in several ways, crucially by assuming sickness insurance compensation. “A central theme in economical research is the negative effects of [insurance compensation].” (SBU 2003, p. 78) Two such effects are „adverse selection‟ and „moral hazard‟.

„Adverse selection‟ refers to the case where the insured and the insurers have asymmetric information (i.e. access to different information). If insurance is voluntary and the asymmetric information problem is severe, predominantly high-risk individuals will be

11 Workers are assumed to “give sickness as an explanation for absence; even if this is not the case, since [it] is considered to be an acceptable excuse for not working… It has been shown by Nicholson (1976) that “when control is exerted over non-sickness absence the level of reported sickness absence tends to rise.” (Brown & Sessions 1996, see page 41 for quotes and reference)

interested in insurance, normal and low risk individuals would not want to be insured since they would have to pay unfairly high premiums due to the „gaming of the system‟ performed by the high risk individuals.

If all workers are forced to be insured, and the asymmetric information problem is not too severe, as is the case with the Swedish sickness insurance system (the asymmetric information problem is reduced in the Swedish system due to the medical criteria‟s for sick-listing mentioned above). In the Swedish „single payer‟ system then, the risk is spread over all insured, something economic theory12 (and evidence) indicate is more efficient for the society, and probably beneficial even for most low-risk individuals. If the system was voluntary (private insurance only) the low risk group might opt out of insurance altogether or be forced to pay unfair premiums (assuming asymmetric information).

„Moral hazard‟ means that insured (here: workers) change their behavior according to the insurance system, so, if the sickness insurance system is more generous there will be more absence and vice versa. In a system with 100% absence compensation (as for example in Norway13) the simple model would predict that all workers were absent all the time since there would be no opportunity cost of „leisure‟ (not working). Since this prediction is proven false, other non-economical or longer term costs of absence have been built in to more advanced models. Health can also be introduced into these models, partly by assuming absence to be a function of actual sickness, partly by assuming that the value of leisure increases with actual sickness. (SBU 2003, p. 78-9)

Moral hazard is likely to be a relevant phenomena concerning regional SIU and will be touched upon below. Asymmetric information however is not likely to be relevant in explaining the regional variance in SIU. As Lindbeck et al (2009) write:

Since the Swedish sick-pay insurance system is mandatory and uniform, the rules and the availability are well-known to all individuals in the country. (Even immigrants are informed about the details of the social insurance system when settling down in Sweden.) … [T]he acquisition and interpretation of information about the Swedish sick-pay insurance system is a trivial task. This means that group effects can hardly be interpreted as the result of the dissemination of information about the availability of sickness benefits. This strengthens our interpretation of group effects as the results of social norms, rather than of information. (p.4)

Labor mobility and health

A connection between labor mobility and sickness-withdrawal with stress as the „medium‟ is implied by existing theory. In summary: 1) Higher labor mobility implies better job-matching for individuals. 2) According to the “Person Environment Fit” stress theory this would reduce stress. 3) Stress in turn is identified as the cause of several illnesses in the medical literature.

Job transition theory (what happens to workers who quit) previously regarded turnover from a negative stress perspective; turnover itself was seen as a potentially disruptive and stressful event. More recently however, transition theory regards turnover from a positive, “proactive growth perspective”. According to this perspective, workers who turnovers

12 See for example Krugmans July 25th 2009 NY Times column: Why markets can‟t cure healthcare.

13 I do not know if this is the case at present, but apparently it was in 2003. According to SBU (2003) “large groups” in countries such as Germany also had (maybe still have, I don‟t know) 100% absence compensation.

strive to find work that fits their personality and allows active learning and growth. From this perspective then, turnover reduces rather than produces strain. “The empirical research seems to support this last „positive‟ perspective” (de Croon et al 2004).

The idea that higher labor mobility implies better job-matching was recently echoed in a Swedish report. First there are a number of studies connecting agglomeration with increased productivity; Anderson & Thulin (2008) refers to at least three Swedish14, and a number of foreign studies supporting this connection. They reference Yankow and Wheeler (both 2006) whom investigate the causes of this „urban productivity premium‟ and in their conclusions they both point out that better job-matching in “thick and dense markets” is likely to be an important explanation to the „urban productivity premium‟ (see Andersson & Thulin 2008 p. 26-9 for references)

Why would a simple job mismatch have health effects? Brunner and Marmot (2006), two medical scientists write the following on the topic of stress:

We are now beginning to recognize that people‟s social and psychological circumstances can seriously damage their health in the long term…The power of psychosocial factors to affect health makes biological sense. The human body has evolved to respond automatically to emergencies. This stress response activates a cascade of stress hormones which affect the cardiovascular and immune systems…if the biological stress response is activated too often and for too long, there may be multiple health costs. These include depression, increased susceptibility to infection, diabetes, high blood pressure, and accumulation of cholesterol in blood vessel walls, with the attendant risks of heart attack and stroke. (p. 28)

To summarize:

i) If a worker is poorly fitted, or mismatched, that is: if he does not like his place of work, he will experience stress. (Person Environment theory)

ii) Long term stress is recognized to be the cause of multiple health costs. (Brunner & Marmot 2006)

iii) In regions with higher labor mobility rates there is evidence of better job-matching, (see Andersson & Thulin 2008 for references) therefore regions with higher labor mobility rates can be expected to have less stressed i.e. healthier workers and therefore „consume‟ less sickness insurance.

Empirical support for a connection between labor mobility and health

Rothstein & Boräng (2005) theorized that “lack of mobility on the labor market is a cause of the increase long-term sick listed and early retirees” (p. 187). They argued that low labor mobility in Sweden compared to Denmark could be a cause for the higher rates of sickness withdrawal in Sweden compared to Denmark. They refer to a number of studies to establish the difference in labor mobility (p. 197-8):

Denmark has the highest labor mobility in Europe (Denmark‟s Statistics 2004). The share of newly employed (less than one year‟s employment) is 23 percent in Denmark, in comparison with barely 16 percent in Sweden (von Otter

2003)…In Sweden the share with ten years or longer tenures was 46.7 percent in 2000 while it was 31.1 percent in Denmark (Auer and Cazes 2003)…Labor mobility within Sweden‟s public sector is lower than the EU-average while publicly employed are overrepresented among sick-listed. In the Danish public sector labor mobility is in line with the national average and the Danish public sector does not have nearly as strong overrepresentation of sick-listed as the Swedish public sector (Auer & Cazes 2003; Swedish Ministry of Finance 2002).

Rothstein & Boräng (2005) also refer to at least nine Swedish studies, and a number of foreign which they (convincingly) argue support the idea of a connection between low labor mobility and sickness absence. They conclude that: “it appears to be important from a health perspective to have a job that one likes and there appears to be many people whom for health reasons want to change jobs but does not. An increase in voluntary workplace changes could therefore have a positive effect on workers health.” (p. 191)

Rothstein & Boräng (2005) suggested that the low labor mobility generally in Sweden15 (in the country as a whole), may be a cause of high SIU. This thesis will investigate if regional differences within Sweden show signs of affecting SIU. If such signs are found it will strengthen R&B‟s theory, and conversely if they are not found that would at least indicate that the effects of regional variation in labor mobility on SIU is not strong, something they themselves may well expect, paraphrasing: “We want to emphasize that we imagine this idea of low labor mobility to explain only a small part of the high SIU in Sweden” (p. 187-8). They point to the difficulties in testing their theory: “Ideally it would be done through a massive panel database (i.e. where a large group of individuals are followed over a long time). Lacking these data we have tried to substantiate our theory by comparing Sweden and Denmark.” (p. 193). This thesis is partly an attempt to „test‟ this theory with regional data. Since the regional variance in labor mobility is expected to have only a small effect on SIU, therefore we need to control for confounding variables, other factors that affect SIU. What are those factors?

2.1 Understanding the regional variance in SIU

There are only three earlier regressions studies on regional variation in SIU in Sweden published by the Swedish Social Insurance Agency. Of these studies Dutrieux & Sjöholm‟s (2003) paper is the most helpful. The other two studies by Olsson (2004 & 2006) are very short on theory. All three studies are explorative in character, and many regional variables assumed to be connected with SIU are tested for significance. The 2003 study lays some theoretical grounds for thinking about the subject, summarized below.

Theoretically, two categories of factors affecting regional SIU rates can be distinguished i) Factors affecting the populations‟ demand of SIU. For example: demographics

(e.g. age of population), health situation, social and economic „well-being‟ labor market situation, attitudes.

ii) Factors affecting the will/possibilities of the instances granting sickness compensation to actually grant it. For example: density of doctors, attitudes and

15 Andersson & Thulin (2008) surveyed the literature on labor mobility and they write that ”Even if it is normally suggested in the debate that Sweden has a low labor mobility, the general view we have received from several reports is that Sweden is not [markedly] different from other countries in terms of mobility on the labor market.” (p. 30)

knowledge of doctors, and resources and routines (culture) at social insurance offices

This thesis will analyze variables exclusively from the former category, i.e. variables believed to affect the need (or demand) for sick listing. The reason is simply that variables from the second category were unavailable.

The regional populations demand for sickness insurance, i.e. their SIU, may depend on at least three kinds of explanations.

i) SIU should depend on health.

ii) SIU can be seen as the result of a cost-benefit analysis the individual makes between the utility (and possibility) of working versus not working.

iii) The need for SIU may depend on the working environment for employees. Concerning point i) SIU should depend on health. Brunner & Marmot (2008) present a conceptual framework (figure 4, below) where “factors operating beyond the level of the individual, as well as individual characteristics are recognized. Thus, Social structure (top-left of the diagram) influences well-being and health (bottom right).” The authors describe their model as follows:

“The influences of social structure operate via three main pathways. Material circumstances are related to health directly and via the social and work environment. [The social and work environment] in turn shape psychological factors and health-related behaviors.” (p. 8)

Figure 4: Social determinants of health. The model links social structure to health and disease

via material, psychosocial, and behavioral pathways. Genetic, early life and cultural factors are further important influences on population health. Source: Brunner & Marmot (2008, p. 9), text in figure rewritten due to only having access to a copy with poor resolution.

Concerning point ii) SIU can be seen as the result of a cost-benefit analysis the individual

makes between the utility (and possibility) of working versus not working. We may expect

regional cultures, or attitudes to affect the utility of working as opposed to consume sickness insurance; I have no data on regional attitudes however. We may further expect

the wage level to have some affect on the utility of working, it seems likely that higher wages are correlated with better jobs, meaning higher incentives to be present, also the level of insurance is capped at a certain level, so workers with high wages have higher pecuniary amounts to lose relative to workers with lower wages if they are sick-listed. Unemployed can be assumed to make a cost-benefit analysis more in favor of sickness withdrawal, since they can be expected to have lower opportunity costs or even gains associated with SIU, sick-listing for example will prolong the period unemployed are liable for unemployment insurance (Larsson & Runeson, 2007). Another important factor bearing on the cost benefit analysis that is likely to make unemployed more likely than workers to report sick is that when workers are sick-listed they receive only 77.6% of their ordinary wages, while unemployed do not loose anywhere near as much by being sick-listed, and some unemployed whom have earlier had high paying jobs can actually gain economically by being sick-listed (Larsson & Runeson, 2007). Finally, for workers, work is connected with meeting work-mates, while the „work‟ of unemployed (looking for work) can be expected to be much less socially rewarding. Hence the social opportunity costs of sickness withdrawal are likely to be relatively lower for the unemployed.

Lindbeck et al (2009) study if the sick-listing of individuals is affected by the sick-listing of their neighbors. They argue that two “characteristics of the Swedish sick-pay insurance system that facilitate the emergence of local benefit-dependency cultures”:

First, the replacement rates are quite high for a majority of employees…which is likely to create a strong temptation to “overuse the system” (moral hazard). Second, the administration of the system was quite lax during the period under study [1996-2002], i.e., individuals themselves could to a large extend choose whether to live on sickness benefits. Sickness spells longer than one week requires a doctor‟s certificate, but there is strong evidence that doctors rarely turn down requests for such certificates. For instance, Englund (2008) found that doctors were prepared to provide certification in 80 percent of the cases where the doctors themselves believed that sick leave was either not necessary or even harmful. (p. 2)

Concerning point iii) the need for SIU may depend on the working environment for

employees. Palmer (2006) writes that: “…no statistics exist demonstrating large

differences in general health or working environments across regions – neither now nor earlier – while there are longstanding regional differences in sickness insurance usage” (p. 52 my emphasis.) I will use data on workplace sizes to capture regional differences in working environments. We know that larger workplaces have higher rates of sickness absence. The explanation usually given for this is that the “social control” is greater in smaller workplaces (Statistics Sweden 2004). An example of this could be that it is easier to talk directly to the “big boss” if you work in a small workplace. And that you therefore would feel more in control.

Dutrieux & Sjöholm (2003) summarized their theoretical section by forming three “simple hypotheses”:

Poor socio-economic standard → lower general health and/or working environment → high sick-listing/early retirement rates

High average age →lower general health → high sick-listing/early retirement rates

These very broad hypotheses may be “simple”, but considering the more recent literature on public health that has been available to me, I see no need to change them. It seems appropriate to add one thing to the first hypothesis though:

Poor socio-economic standard → lower general health and/or working environment

and/or sense of control of life in general → high sick-listing/early retirement rates

2.2 Earlier research on regional variation in SIU in Sweden

Three studies from the Swedish Social Insurance Agency have tried to further the understanding of regional (municipal) differences in sick-listing and early retirement through regression analysis (Dutrieux & Sjöholm, 2003; Olsson, 2004 and 2006). They are all similar in that they perform what one might call exploratory pattern mining. Performing significance testing for many variables believed to influence regional SIU, to see which appear most relevant. They derive best fit models without „forcing‟ any particular variable to be in the model. Instead many variables are tested, and those that are statistically significant are presented. Results from regression models from these three earlier studies are summarized in appendix H.

Dutrieux & Sjöholm (2003) present the theoretically most underpinned regression model of SIU. From the basis of their hypothesis that i) the age structure ii) the social well-being iii) the economic well-being & iv) the labor market situation in the regions should affect SIU, they do statistical estimations to find which variables out of many possible “seem to” capture these four factors best. They find that the best variables for capturing these factors are; for the age structure: the share of 16-64 population aged 45+. For the social well-being: the share of population with at most two years high school education. For the economic well-being: the average wealth taxed. And finally, for the labor market situation: the employment rate. This simple model explained 57% of the municipal variation in net days of SIU year 2000. All the signs of the coefficients were as expected and significant (see appendix H).

Since, as Dutrieux & Sjöholm (2003) write “the [variables chosen] to describe certain properties of the municipalities do not rest on strong theoretical grounds” (p. 36). They argue that an alternative methodology is justified. A more mechanical, best-fit procedure can be used within the framework of the “simple hypothesis”: “It is valuable in itself to test multiple measurements reflecting the same basic properties. Given that they all point in the same direction, this can be seen as giving stronger support to the basic hypothesis than if only the few variables in the base model confirm them.” (p. 36). They go on to produce this kind of “data snooping model” and it lends further support for the basic hypothesis (results of both models in Appendix H). I will use a similar methodology (described below).

To summarize, I have found three earlier studies investigating the regional variance in sickness insurance usage by means of regression. All three were published by the Swedish Social Insurance Agency, and all three use a “data snooping” methodology for finding models with high R2 values. Some variables are especially interesting since they are found significant in all three regression studies published by the Swedish Social Insurance Agency:

Age (older = sicker), as measured by: share of 16-64 year old population over 45

(Dutrieux & Sjöholm 2003); share of population aged 55-59 & 60-64 (Olsson 2004); average age (Olsson 2006).

Education level (lower = sicker): as measured by: share of population with at most two

years high school education (Dutrieux & Sjöholm 2003). Share of 20-64 year old population with 1-2 years of university level education, and with 3+ years of university level education: both negative (Olsson 2004 & 2006).

Employment / Unemployment rate (less employment = sicker regions): Dutrieux &

Sjöholm (2003) argue that the employment rate is a more direct measure of the regional availability of work than the unemployment rate, which rather captures the competition on the labor market (footnote 23, p. 35). Either way, the measures are highly correlated, and when only of the measures are used in the models above; the results are that a high employment rate (or low unemployment rate) is linked to lower SIU. Dutrieux & Sjöholm (2003) argue that structural unemployment explains this between municipalities‟ phenomenon: “Structural unemployment, [i.e.] a permanently higher supply than demand for labor in the municipality, points to a greater propensity for sick-listing [and early retirement]” (p. 44).

‘Public employment’ (the more the sicker) as measured by: municipal employment in

(Dutrieux & Sjöholm, 2003 & Olsson 2004) and (the opposite of) „employees in incorporated company‟ (Olsson 2006) and „privately employed‟ (Olsson 2004) appears to predict higher rates of SIU. The overrepresentation of publicly employed among people receiving sickness insurance in Sweden is well known (see e.g. Rothstein & Boräng, 2005) so this is unsurprising. Lindbeck et al (2009) say that there may several reasons for this: “The most obvious one is that is that private employers have stronger incentives than public-sector employers to prevent absence, since it is costly to the former. It could also be the case that workers with preferences for frequent absence tend to self-select into the public sector.

Base model

These four variables will enter the base model of my investigation. In addition I will add three variables to the base model: the natural log of regional population - to estimate the importance of regional-size; taxable wealth units - since a close variant of it has been found to capture the economic well-being of the regions well (Dutrieux & Sjöholm, 2003); the share of Immigrants (from any country) - since immigrants workers have been found to have considerably higher degrees of sick-listing compared to native workers (see below, figure 5)

As is described in the methodology section below, I will evaluate more variables than the 7 used in the base model. A total of 18 variables will be assessed (with labor mobility given special attention). They are all described along with what effect they are expected to have on SIU in appendix A. Summary statistics of all variables can also be found in appendix A.

3

Dependant variables

FA-regions were chosen as the unit of observation (see appendix I for a map of them). Data was collected for the years 2003-2007, all observations were then averaged over these years in order to make a simple cross section analysis. Observing FA-regions is a little unusual; usually municipalities are used for cross-sectional studies in Sweden. FA-regions

are larger regions consisting of one or more municipalities (there are 290 municipalities and 72 FA-regions in Sweden). The reason for choosing FA-regions - despite the loss of observations - was that some variables were only available to me on this aggregated scale (labor mobility being the most important). But one could also argue that FA-regions are more logical to observe than municipalities - due to the way they are calculated. FA-regions are defined as FA-regions where people to a large extend both live and work. For smaller regions (municipalities), it is much more common for people to live in one region and work in another i.e. commuting between municipalities is rampant. The thought was that this could add some statistical problems, commuting implies „noise‟, i.e. a difficulty in separating the effects from the „live-region‟ and the „work-region‟ on the dependant variables. If many work in a different region than where they live, (common if you compare municipalities) is it the characteristics in the „live-region‟ or the „work-region‟ that make them sick? By using FA-regions this “commuting problem” is minimized.

The three dependant variables are defined as follows:

Sick-listing per worker (SLPW): Net number of days with „sick-listed benefits‟ per insured aged 16-64 in the region, divided by the number of employees in the region. All insurance days are recounted into „whole days‟, i.e. two days with half enumeration equals one day. Days with „sick wage16‟ from the employer is not included in this number. Sick-listing data is from the Swedish Social Insurance Agency, Employment data is from Sweden Statistics. The net sick-listing per insured data is divided by employees because otherwise the measure would be misleading. A requirement for receiving sick-listing insurance is that one has been previously employed (a person need to have a: „sick-listing qualifying history of income‟ [sjukpennings grundande inkomst – SGI]). In regions where the employment rate is low, sick-listing will be lower simply because fewer are likely to have a history of employment. By dividing regional sick-listing by the regional employment we „control‟ for this.

The sick-listing per worker variable is difficult to wrap one‟s head around. To repeat, it is derived from data on net days of sick-listing per insured. Since this latter data is mechanistically linked to the number of employed however17, it was decided to „control‟ for this by dividing by the number of employees in the region. Dutrieux & Sjöholm (2003) made the same choice since: “the effect we want to estimate is that of the employment rate on the regional tendency for sick-listing, an affect assumed to be dampening” (footnote 18, p. 33)

Share of Population in Early Retirement (SPER): Number of people receiving early retirement compensation [sjukersättning, aktivitetsersättning] divided by population (aged 20-64).

Total Sickness Insurance Usage (TSIU): Number of days where insurance is paid out for a number of reasons; sick-listing, work injury, rehabilitation, disabilities e.g. early retirement per insured aged 16-64. All days are recounted into „whole days‟, i.e. two days with half enumeration equals one day. Days with „sick wage‟ from the employer are not included in this number. The overwhelmingly biggest posts making up the total sickness

16 Since 1992, the employer pays the sick employee for a number of days, and only after 21 days (2003-2004) or 14 days (2005 forward) does the social insurance office pay – and gather statistics. Hence all employed people who report sick for short periods of time (less than 3 weeks 03-04, less than 2 weeks 05-07) are „invisible‟ in this data. This is not the case for sick-listed unemployed however; they receive benefits from day two (Försäkringskassan; Larsson & Runeson, 2007).

insurance costs are early retirement followed by sick-listing. In 2005, total sickness insurance costs were about 87.5 billion in Sweden, of which about 63 percent came from early retirement, and about 37 percent came from sick-listing. (Lundberg 2006).

4

Methodology

Sickness insurance usage (SIU) consists of sick-listed and early retirees. I will therefore test which variables best describe regional sick-listing and early retirement as well as which variables best describe their sum; the total sickness insurance usage (TSIU) measurement.

Similarly to Dutrieux & Sjöholm (2003) I will test both a “base model” and mechanistically chosen best-fit „optimal models‟. Since the measures chosen to describe a certain characteristic of the municipalities do not rest on strong theoretical grounds, i.e. not even the “base model” is strongly grounded on theory18

, an exploratory approach is justified. To choose best-fit models, I use an extension to STATA called “TRYEM19”. This extension tests all possible regression models that can be constructed with k independent variables selected out of a larger set of n variables. I constricted myself to n=18, since the “TRYEM” procedure would take too much time to perform with more variables. For example, for k=8 there are 𝑛 = 18𝑘 = 8 = 𝑘! 𝑛−𝑘 !𝑛! = 43758 possible models (subsets of 8 out of 18); “TRYEM” tests all of these possible models and reports the one model out of the 43758 models that has the highest adjusted R2.

First, the “base model” (described above, see page 16) is tested to see how well it “performs. Secondly, the “data-snooping” procedure is performed on all three dependent variables: SIU (per insured aged 16-64), sick-listing per employed, and, early retirement (per population aged 20-64). The “data-snooping” routine outlined above is performed with a range from two to eight independent variables. Finally, for all models where labor mobility is not chosen by the “data-snooping” procedure, it is additionally tested; controlling for the variables actually selected to see if it appears to have an effect controlling for the variables actually chosen in the various “optimal models” decided by the data-snooping procedure. All of these results are in appendix C-E. In the text I will only present six models (table 1), the „base models‟ and „the optimal models‟ the latter is defined as the models whom were found to give the highest adjusted goodness of fit measures where all independent variables were also statistically significant. If all this seems very confusing, I hope that it becomes clear when the reader sees the appendices (C-E) where all results are summarized.

18 In the sense that other variables may capture the regional populations‟ socio-economic standard and cost-benefit analysis of SIU better.

19

The “TRYEM: Stata module to run all possible subset regressions” was downloaded here:

5

Limitations

“Early life health has been shown to have lifelong effects that result from the interaction of biological development and social and environmental circumstances.” (Wadsworth &

Butterworth, 2008)

Causes of regional variance in SIU under the period studied may lie far back in time, when the populations measured were growing up. In this thesis a rather short time-span is studied (2003-2007). It is likely that the characteristics of the regions further back in time, which are not studied, affect its inhabitant‟s SIU today. This is likely to be especially true for early retirement (that regional differences before the time covered in this study, are confounders of my results). Once people enter early retirement, they are often „in for life‟. The overwhelming part of the outflow from early retirement is that people pass 65 years of age (and receive other kinds of support) or that they die. The share that stops receiving early retirement benefits for “other reasons” (than dying or being too old to qualify) have been increasing in recent times however, and in December 2008, about 20% of the outflow was for “other reasons” (Swedish Social Insurance Agency, 2009.) Still, if some regions had considerably different characteristics in the past, this may well have led to relatively many/few entering early retirement in these regions for reasons not controlled for.

Another small problem of the study stems from the data used. In the dependant variable TSIU, net days of sickness insurance usage is divided by the number of insured aged 16-64. This number (from the Swedish Social Insurance Agency) does not exactly match Statistics Sweden number of inhabitants aged 16-64. So it is likely that some small bias is introduced into this dependant variable when compared to the independent variables. That is, for regions where data on the number of insured differ from the data on the number of inhabitants we have a problem; all independent variables that are a quotient with inhabitants as divisor will not exactly „match‟ the dependant variable. For consistency, SIU should have been defined as “net days of sickness insurance divided by the number of

inhabitants aged 20-64. But the Swedish Social Insurance Agency does not supply its

number of regionally insured on a finer level than counties, making this impossible to solve for FA-regions. In any case, the inconsistencies between the data from the Swedish Social Insurance Agency (SSIA) and Statistics Swedish (SS) are not large. I compared the data for counties; „Skåne‟ was the region that differed most between insured (SSIA data) and population (SS data). Between 2003 and 2007 the data for population was on average 2.4 percent higher than the data for number of insured in this region.

6

Results

For an overview of all regression results see appendices C-E. Below is table 1,where we can see a summary of the results from the base models, and selected exploratory, “data snooping” models. The latter are chosen as “optimal” because they are just that in the sense that no other model can be constructed from the 18 independent variables to yield higher adjusted goodness of fit measures and at the same time have all independent variables be significant. A more complete description of the most relevant regression model, the optimal model for TSIU is found in appendix F.

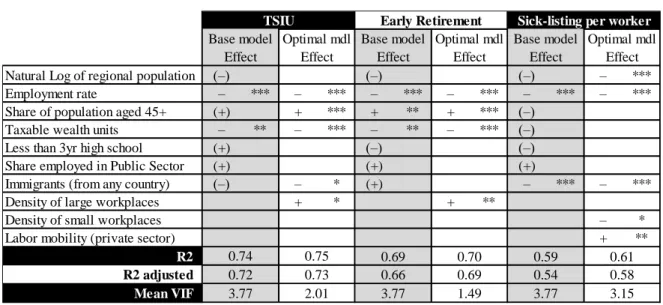

Table 1: Results from the „base‟, and „optimal‟ models.

Notes: Signs within parenthesis are not significant at the 10precent level. ***, **,* = significant at 1, 5, 10 -percent level.

Results confirm the general hypotheses, that is, it was expected that:

1) Poor socio-economic standard → lower general health and/or working environment and/or sense of control of life in general → high sick-listing/early retirement rates 2) High average age → lower general health → high sick-listing/early retirement rates 3) Low (or negative) cost of SIU → high sick-listing/early retirement rates

Remarkably, as is visible in appendix E, a high71 percent of the FA-regional variance in TSIU can be explained by just three variables: the employment rate, the share of

population aged 45+, and the share of taxable wealth units. It‟s seems likely that we may

interpret the high explanatory power of these variables as to a high degree capturing the three fundamental causes of sick-listing suggested by the general hypotheses.

The base models for the three dependant variables get similar (only slightly lower) goodness of fit measures as the „optimal‟ models. Not many variables end up significant in the base models though. This is probably because of the high correlations between many variables in these models, the variables: „share of population aged 45+‟, „natural log of regional population‟, and „less than 3yr high school‟ all have pairwise correlation coefficients above 0.80 between each other. (For pairwise correlations of all variables see appendix B.)

That the four variables in the base model „borrowed‟ from Dutrieux & Sjöholm (2003) are not all significant when larger FA-regions are observed is also likely due to having fewer observations (aggregates of municipalities), much of the variance the regressions

Natural Log of regional population (–) (–) (–) – ***

Employment rate – *** – *** – *** – *** – *** – ***

Share of population aged 45+ (+) + *** + ** + *** (–)

Taxable wealth units – ** – *** – ** – *** (–)

Less than 3yr high school (+) (–) (–)

Share employed in Public Sector (+) (+) (+)

Immigrants (from any country) (–) – * (+) – *** – ***

Density of large workplaces + * + **

Density of small workplaces – *

Labor mobility (private sector) + **

R2 R2 adjusted Mean VIF 3.77 2.01 0.58 0.61 3.77 3.15 1.49 3.77 0.75 0.69 0.66 0.70 0.54 0.59

Sick-listing per worker Base model Optimal mdl Base model Optimal mdl

Early Retirement

Effect Effect Effect

0.73 0.69

Effect TSIU

Base model Optimal mdl Effect

0.72 0.74

have to „work‟ with is lost (compared to municipal variance regressions). In better words; since the analysis is made on relatively few observations (72 FA-regions) the amount of explanatory variables that can be interpreted in one model is limited. According to the optimal models, the „roof‟ for an applicable statistical model appears to be about five explanatory variables (adaptation of an argument in Olsson, 2006, see page 593).

As is visible in table 1, two further variables are suggested as significant explanatory variables of TSIU by the optimal model: Immigrants (from any country), and Density of

large workplace. Theory suggests that large workplaces could have negative effects on

worker health, and this seems to be confirmed here, in the optimal early retirement model the density of large workplaces is found to predict higher rates of early retirements, and in the optimal listing model the density of small workplaces are found to decrease sick-listing rates. So, considering these results it seems likely that the regional densities of “large” workplaces (50+ employees) can explain a small share of the regional variance in TSIU (as is found in the optimal TSIU model).

Concerning immigrants, results from the „sick-listing per worker‟ model suggests that immigrants (from any country), predict lower SIU; the effect of the share of foreign born individuals is estimated as strongly negative on the amount of sick-listing. This seems to be a mystery. Dutrieux & Sjöholm (2003) found the same results observing TSIU (and „sick-listing-frequency‟) for municipalities‟ year 2000. They note that although “results from individual-level studies suggest that the effect should be the contrary…” they find foreign-born (immigrants) to have a negative effect on TSIU. Unfortunately they do not labor further to understand this paradoxical result, but satisfy themselves by noting that “When only the municipalities of the three big city regions are compared, the share of foreign born is indeed positively correlated with [TSIU]. Since the share of foreign born is higher in big-city-municipalities with relatively low social and economic well-being, these results support the initial hypotheses [Poor socio-economic standard → lower general health and/or working environment → high sick-listing/early retirement rates].” (page. 41.) Why then does the results differ so completely when comparing all municipalities or FA-regions? That is, why does the regional share of immigrants predict lower SIU when all municipalities/FA-regions are compared, which holds even controlling for other factors such as regional population and employment rate. I will suggest a possible explanation below, but let us first summarize our other results, which seem easier to understand.

To summarize the effects of the factors in the optimal TSIU model that are (believed to be) understood (excepting the effect of the share of immigrants, to which we will return below):

It seems likely that a low employment rate increases SIU through general

hypotheses (1) and (3). A low regional employment rate implies that individuals in the region:

i) feel a low sense of control → feel stress → become sick → high sick-listing/early

retirement rates (unemployment is known to have negative health effects),

ii) unemployment seems to imply low (or negative) cost of SIU → high

sick-listing/early retirement rates,

iii) (speculating, there is no data that supports this): have poor working

environments (low employment rates suggest that employers in the region do not have to compete as hard against other employers to „please‟ workers) → become sick→ high sick-listing/early retirement rates

It seems likely that a high share of old people (Share of population aged 45+) increase SIU through general hypotheses (2): High average age → lower general health → high sick-listing/early retirement rates

It seems likely that a measure of regional wealth (taxable wealth units per 20-64yo population) decrease SIU through general hypotheses (1): High socio-economic standard → higher general health and/or working environment and/or sense of control of life in general → low sick-listing/early retirement rates

It seems likely that the regional density of large workplaces increase SIU through the “sense of control hypothesis”: We know that larger workplaces have higher rates of sickness absence. The explanation usually given for this is that the “social control” is greater in smaller workplaces (SCB 2004). An example of this could be that it is easier to talk directly to the “big boss” if you work in a small workplace. And that you therefore would feel more in control.

Concerning one of the initial hypotheses; the suggestion that labor mobility is good for health finds no support in the regressions performed here. On the contrary it appears as though the regional variance in labor mobility is not significantly linked to regional SIU except that it appears to suggest higher sick-listing per worker. That labor mobility (of the private sector) appears to have a positive effect on sick-listing per worker (controlling for the other variables) in the „optimal‟ SLPW model is curious. Perhaps an explanation for this outcome is that labor mobility (of the private sector) is connected with unemployment. Suppose that many workers are fired in a region, and that a few of them find new jobs; labor mobility would go up by definition for that region (see appendix A: labor mobility). However, those who do not find new jobs become unemployed and it is known that unemployed are over-represented among sick-listed. This could be a reason why labor mobility and sick-listing are found positively correlated, this is an explanation that could explain the positive sign of labor mobility while not suggesting that labor mobility in itself is bad for health, which would go against much theory.

How to explain the negative effect on regional sick-listing per worker (SLPW) (and consequently TSIU) found for the regional share of immigrants?

The share of 20-64 year-olds born outside Sweden, that is; the variable Immigrants (from

any country) is negatively correlated with sick-listing per worker (SLPW) (-0.40***), and

in the optimal SLPW model; Immigrants (from any country) is the variable with the strongest (negative) effect (t-value) of all variables (see appendix C). This seems strange since immigrants from most countries have significantly higher sick-listing rates compared to native born Swedes (figure 5). For example, people born in Greece, Iraq, Turkey, and former Yugoslavia had more than twice as many registered sick days as native Swedes over the period 1993-2001 (Bengtsson & Scott, 2008). So, when comparing working

people, immigrants (as a group)20 are more often sick-listed, but on the regional level, a large share of foreign-born is correlated with lower SLPW.

20 Swedish workers born in the USA, Vietnam, and Germany are less sickness absent than native born workers, but the sum of these population groups make up only 6.5% of all immigrants. (my calculation, data source: Statistics Sweden, 2008)