J

Ö N K Ö P I N GI

N T E R N A T I O N A LB

U S I N E S SS

C H O O LJÖNKÖPING UNIVERSITY

C u l t u r a l I n t e g r a t i o n i n M & A

A Study of the Acquisition of Andersen by KPMG in Vietnam

Master Thesis within Business Administration Author: Jing Chen

Vi Nguyen Tutor: Cecilia Bjursell Jönköping May 2010

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all the people involved during the process of writing this Master Thesis.

To Truc Vo for helping us contact the respondents and distribute the questionnaires. To all interview and survey respondents for taking their time and sharing their valuable knowledge and experience.

We would also like to thank our tutor Cecilia Bjursell for her valuable inspiration, great support and precious feedback.

Jönköping, May 2010

Master Thesis within Business Administration

Title: Cultural Integration in M&A: A Study of the Acquisition of Andersen by KPMG in Vietnam

Authors: Jing Chen, Vi Nguyen

Tutor: Cecilia Bjursell

Date: May 2010

Subject Terms: Cross-border M&A, National Culture, Organizational Culture, Cultural Integration

Abstract

Background: As one of the most important means of globalization for companies around the world, mergers and acquisitions (M&As) have been adopted as a core growth and expansion strategy. M&A integration involves combination in various areas, in which cultural integration has an important role. Nevertheless, the potential positive and negative impact of cultural dimensions on the success of M&A activity is somewhat less acknowledged in the business community.

Problem: Most of the M&A research has focused on the strategic and financial fit between the acquired and acquirer firms and culture in M&As does not get as such attention while M&As represent a main organizational event to employees since they threaten and interrupt cultures, cause misunderstandings and frequently compel the integration of people who do not share the same reality.

Purpose: To explore problematic cultural issues in order to get an understanding of the characteristics and outcome of cultural integration as influenced by both national culture and organizational culture in M&A.

Method: In order to fulfil the purpose a qualitative case study approach was chosen. Semi-structured phone interviews were made with the top managers who were responsible for the deal and employees that worked for both companies during the transition period. In addition, two survey were conducted among KPMG and Andesen members.

Conclusion: It could be summarized that KPMG and Andersen deal result in a great loss of ex-Andersen employees, due to the resistence from employees to the new culture after integration. High numbers of employees dropped out of the integrated organization because they were not satisfied with the KPMG culture, and in this case, if KPMG loses the people who are trained and educated, it loses the competence and a lot of the value of the company, and thereby fails to achieve one of its goals for the acquisition. Since many Andersen people left, one interpretation could be it is hard to move from a unified/strong culture to a not so strong/unified culture.

Table of Contents

1

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Problem ... 3 1.3 Purpose ... 3 1.4 Research Questions ... 4 1.5 Definitions ... 4 1.6 Disposition ... 52

Frame of Reference ... 8

2.1 Mergers and Acquisitions ... 8

2.1.1 Culture in Mergers and Acquisitions ... 9

2.2 Culture ... 10

2.2.1 Levels of Culture... 10

2.2.2 National Culture for Work-Related Values ... 12

2.2.2.1 Limitation on Hofstede‟s Cultural Dimensions ... 14

2.2.3 Organizational Culture ... 15

2.2.3.1 Limitation on Schein‟s Model on Organizational Culture ... 17

2.2.3.2 Culture Types ... 18 2.3 Acculturation ... 19 2.4 Theoretical Discussion ... 21

3

Methodology ... 24

3.1 Methodological Approach ... 24 3.2 Research Method ... 25 3.3 Research Approach ... 25 3.4 Research Design ... 26 3.5 Case Study ... 27 3.6 Data Collection ... 28 3.6.1 Interview ... 28 3.6.2 Survey ... 313.7 Summary & Reflection ... 32

4

Empirical Study ... 33

4.1 Case Description ... 33 4.1.1 KPMG ... 33 4.1.2 Andersen ... 34 4.1.3 Acquisition ... 37 4.2 Findings ... 374.2.1 Theme 1 – Values and Beliefs ... 37

4.2.2 Theme 2 – Cultural Dimensions ... 39

4.2.2.1 Employees‟ Perception of Organizational Cultures ... 42

4.2.3 Theme 3 – Processes ... 45 4.3 Summary ... 46

5

Analysis ... 47

5.1 Culture Types ... 47 5.2 “Marriage” Types ... 48 5.3 National Culture ... 505.4 Organizational Culture ... 52

5.4.1 Artifacts ... 52

5.4.2 Espoused Values and Beliefs ... 54

5.5 Summary ... 56

6

Conclusions and Discussion ... 58

6.1 Conclusions ... 58

6.2 Implications ... 60

6.2.1 Practical Implications ... 60

6.2.2 Implications for Future Research ... 61

6.3 Reflections ... 61

Table of Figures

Figure 1: Thesis structure ... 7

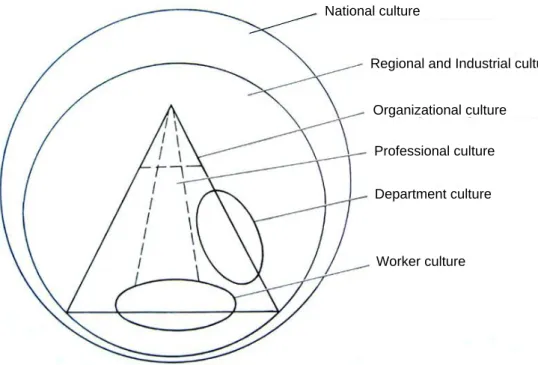

Figure 2: Levels of culture. Source: Alvesson & Berg (1992, p64) ... 10

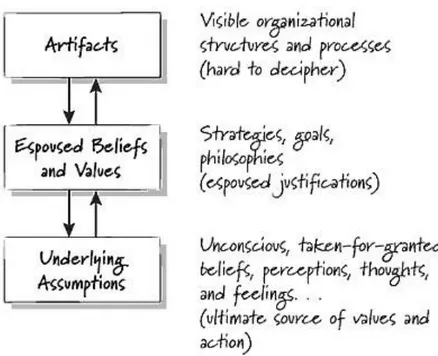

Figure 3: Model of organizational culture. Source: Schein (2004, p.26) ... 16

Figure 4: The relationship between culture types in terms of the degree of restraint they place on individuals. Source: Cartwright & Cooper (1996)18 Figure 5: Modes of organizational and individual acculturation in M&A, and its potential outcomes. Source: Cartwright & Cooper (1996) ... 20

Figure 6: Cultural Dimensions in M&A Integration ... 22

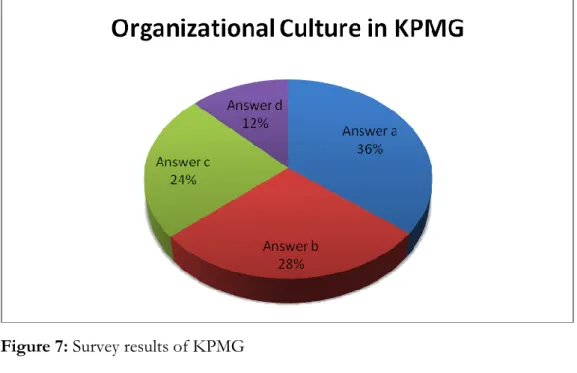

Figure 7: Survey results of KPMG ... 44

Figure 8: Survey results of Andersen ... 44

Figure 9: Culture type of KPMG and Andersen ... 45

Table of Tables

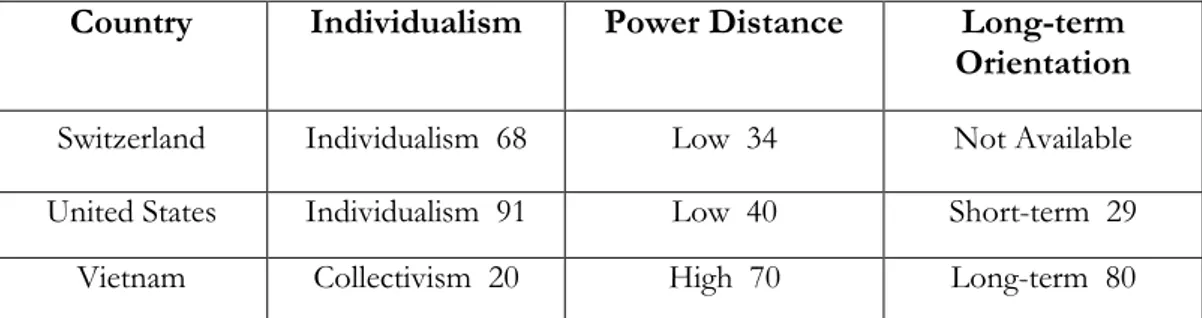

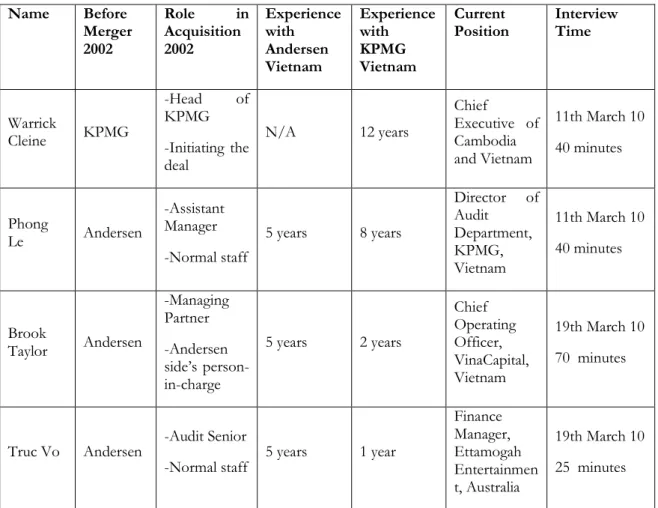

Table 1: Cultural Dimension Score. Source: Hofstede (2005) ... 13Table 2: List of interviewee... 30

Table 3: Comparison of empirical data and Hofstede‟s (2005) cultural dimensions ... 50

Table 4: Survey results of KPMG (number of responses) ... 71

Table 5: Survey results of Andersen (number of responses) ... 71

List of Appendices

APPENDIX A: INTERVIEW GUIDE ... 68APPENDIX B: ONLINE SURVEY ... 69

APPENDIX C: OVERALL SURVEY RESULTS ... 71

1

Introduction

In this chapter, the background to the topic of this thesis is presented. Prior research on the definition and general trend of Mergers & Acquisitions (M&As) is introduced. The emphasis of the study is on the cultural integration in the M&A process, through the case study of a local integration process between two Multi-national Corporations‘ (MNCs) subsidiaries in Vietnam. Problems explored from the case studies on the cultural side are discussed, which will guide and fulfil the purpose of this study. Key terminologies are explained to help better understand this thesis.

1.1 Background

Thomas L. Friedman said that the world is flat and globalization has now shifted into warp drive. As one of the most important means of globalization for companies around world, mergers and acquisitions (M&As) have been adopted as a core growth and expansion strategy. M&As are becoming an increasingly popular strategy option for organizations (McEntire and Bentley, 1996). This complex phenomenon which M&As represent has attracted considerable interest from a variety of management disciplines over the past 30 years (Cartwright & Schoenberg, 2006).

During the turbulent 1980s, nearly half of all U.S. companies were restructured, and over 80,000 were acquired or merged. In 1996 alone, there were at least 10,000 mergers and acquisitions. (Sherman, 1998) In the UK, the biggest and most sustained wave of M&A activity occurred in 1990s. (Cartwright and Cooper, 1996) In 1998, mergers were worth US$2.4 trillion worldwide, a 50% increase on 1997, which was itself a record year. In 1999, this figure exceeded US$3.3 trillion and in 2000 US$3.5 trillion. In Europe, a major M&A activity area, the value of M&As rose to $1.2 trillion in 2002. (Ghauri & Buckley, 2003). In 2004, 30,000 acquisitions were completed worldwide, equivalent to one deal every 18 minutes. The total value of these acquisitions was $1,900 billion, exceeding the GDP of some large countries.

As M&As continue to be a highly popular and common form of corporate development, firms are increasingly more engaged in M&As activity to achieve financial and strategic goals. Also, companies from emerging markets have grown rapidly in terms of their international expansion activities (Luo and Tung, 2007). In China, for example, outward foreign direct investment (FDI) amounted to US$21.16 billion in 2006, 40 percent of which was in the form of cross-border M&As (MOFCOM, 2006). Corrigan (1993) stated that the speed and scale of international expansion in the form of M&As has been growing at an exponential rate, which also implies the increasingly important position mergers and acquisition are for companies to become more competitive on a global scale. Large companies seeking expansion overseas are looking for acquisitions which fit strategically with their main business and provide economy of scales which help cope with the strains of operating internationally (Corrigan, 1993). Cartwright (1998) argues that M&As are a remarkable phenomena, not only due to high levels of financial investment engaged but also because of their disappointing results.

Cartwright and Cooper (1996) state that while M&As are increasing in frequency, at least 50% fail to meet financial expectations. Cartwright (2006) argues that financial and strategic factors alone are not sufficient to explain this high rate of M&A failure. Lack of cultural

compatibility or poor culture-fit is believed to be one of the reasons for M&A failure (Cartwright & Schoenberg, 2006). Thus, Cartwright (2006) highlights that the successful management of integrating members and their cultures is the key to attaining the desired M&A outcomes. When the number of cross-border transactions increases, many national players are involved, the issues of cultural compatibility occur even more emphasized (Cartwright, 2006). Accordingly, a field of enquiry has emerged to direct at the cultural dynamics of M&As and the behavioral and emotional response of the members involved (Cartwright & Schoenberg, 2006).

National culture and organizational culture play a simultaneous and important role in an organization (Gulev, 2009). Korut and Singh (1988) discovered that differences in national cultures result in dissimilarities in organizational and administrative practices and employee expectations. Johns says that ―national culture constrains variation in organizational cultures‖ (2006, p. 396), while others state that organizational culture ―mirrors‖ national culture (Javidan et al., 2004). Gerhart (2009) argues that ―most of the variance in organization cultures cannot be explained by country and, of that explained by country, only a minority is due to national culture differences‖ (p. 2). Therefore, in order to have a comprehensive understanding of a companies culture, national and organizational culture should be studied thoroughly. In the case of multinational companies (MNCs), there is a need to address the fit of organizational culture with the dissimilar national cultures where the company operates (Silverthorne, 2005).

M&A integration involves combination in various areas, in which cultural integration has an important role. Nevertheless, the potential positive and negative impact of the cultural dimension on the outcome of M&A activity is somewhat less acknowledged (Forstmann, 1998). According to Larsson and Risberg (1998), some questions are raised within the field of cross-border M&A, ―of which organizational and national clashes are the most detrimental to cross-border combinations?‖, ―should differences in organizational culture be given more weight than national differences?‖ (p. 40).

Morosini, Shane & Singh (1998) suggest from their study that scholars should investigate the value of cultural distance to acquisition performance. Moreover, further research should consider the influence of organizational culture, which could be affecting cross-border acquisition outcomes. Besides, those authors recommend scholars to separate the impacts of corporate cultural differences and national cultural differences on cross-border acquisition performance. (Morosini, Shane & Singh, 1998) Furthermore, the scholars are recommended to explore the simultaneous relationships among two or more Hofstede‘s dimensions and management practices (Newman & Nollen, 1996). Research on Hofstede‘s implied interactions may be a significant next step in our understanding of cross-cultural differences in the efficiency of management practices (Newman & Nollen, 1996).

Although it may compound the integration complexity to have many cultural differences in M&As, they are not necessarily a direct threat to the integration outcome (Larsson & Risberg, 1998). Instead of giving up potentially valuable strategic complementarities in the pursuit of cultural similarities, companies can be aware of and learn to deal with the differences in order to gain more benefits (Larsson & Risberg, 1998).

1.2 Problem

The complex phenomenon which M&As represent has attracted the interest and research attention of a broad range of management disciplines encompassing the financial, strategic, behavioural, operational and cross-cultural aspects of this challenging and high risk activity. Although the benefits along with M&As become the main motivation, there can be significant challenges , in which culture both organizational and national culture are argued to have a strong influence on the outcome of the merger (Larsson & Risberg, 1998). Whereas research into the human and psychological aspects of M&A has increased recently, the M&A literature continues to be dominated by financial and market studies, with a high focus of interest in the USA and UK (Cartwright, 2005). Most of the M&A research has focused on strategic and financial fit between the acquired and acquirer firms (e.g. Nahavandi & Malekzadeh, 1988; Cartwright and Cooper, 1996) and culture in M&As does not get as such attention (Cartwright and Cooper, 1996) while M&As represent a main organizational event to employees since they threaten and interrupt cultures, cause misunderstandings and frequently compel the integration of people who do not share the same reality (Cartwright, 1998). For example, Krug and Aguilera (2005) discovered from their study that the target firm executives experience substantial acculturative stress and, on average, almost 70% leave the firms in the five years following completion.

As discussed above, national and organizational culture in M&A have been recommended for further study (Morosini, Shane & Singh, 1998). Moreover, Cartwright and Cooper (1993) find that not only the cultural fit matters, but also the extent to which the firms are integrated. Therefore, the authors of this thesis put a focus on the culture side of the spectrum during the M&A process. Through the lenses of national culture and organizational culture, together with the case study of KPMG and Andersen in Vietnam, the characteristics and outcome of cultural integration are discussed. The authors conducted personal interviews with top managers and employees from both sides to explore the issues incurred by the cultural differences in the the attempt to integrate the cultures.

The case study is about a local integration of two global companies with KPMG Vietnam as the acquirer and Andersen Vietnam as the acquired company. KPMG is a global network of professional firms offering audit, tax and advisory services. Andersen was once one of the "Big Five" accounting and consulting firms among PricewaterhouseCoopers, Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu, Ernst & Young and KPMG. Since the demise in 2002, the ―Andersen‖ name disappeared from the world auditing and consulting scene (Cleine, 2002). As one of the affected 23 businesses, Andersen Vietnam was acquired by KPMG. According to KPMG CEO (2010), acquiring Andersen was the fastest way to improve its market position in Vietnam. The acquisition enabled KPMG to increase its competitiveness, access to Andersen‘s strong client network base, methodology and well-trained resources.

1.3 Purpose

The purpose of this thesis is to explore the problematic cultural issues in order to gain an understanding of the characteristics and outcome of cultural integration as influenced by both national culture and organizational culture in M&A.

1.4 Research Questions

A local M&A and the subsequent local integration process of two globally merging multinational corporations‘ subsidiaries have to be implemented in the two subsidiaries‘ host country environment.

- How does the national culture influence the cultural integration of two companies? - How does the involvement of two companies‘ management based on their goals

for the M&A influence the employees‘ assimilation into the organizational culture after integration?

- To what extent is the acquired company integrated into the acquiring company? - What elements from national and organizational culture theory are relevant to

understand the local integration of global companies in the case described?

1.5 Definitions

To help the readers follow the thesis easier, the authors would like to clarify some key terms and concepts.

Merger and Acquisition (M&A)

‗Merger‘ and ‗acquisition‘ are two different transactions. Although ‗merger‘ is informally used for both cases, only ‗acquisition‘ will be applied in this paper because our case study is actually an acquisition. Furthermore, ‗integration‘ or ‗combination‘ can also be used as an alternative.

Merger

A merger typically refers to two companies coming together (usually through the exchange of shares) to become one (Sherman, 1998).

Acquisition

An acquisition typically has one company—the buyer—who purchases the assets or shares of the seller, with the form of payment being cash, the securities of the buyer, or other assets of value to the seller (Sherman, 1998)

Cross-border M&A

According to UNCTAD (2000), cross-border M&As are playing an increasingly significant role in the growth of international production. Beside dominant FDI flows in developed countries, they have begun to take hold as a mode of entry into developing countries and economies in transition.

A cross-border merger can be defined as a transaction in which ―the assets and operations of two firms belonging to two different countries are combined to establish a new legal entity‖ (UNCTAD, 2000, p. 99).

A cross-border acquisition can be defined as a transaction in which ―the control of assets and operations is transferred from a local to a foreign company, the former becoming an affiliate of the latter‖ (UNCTAD, 2000, p. 99).

Our study focuses on the local acquisition -integration process between two subsidiaries of two globally MNCs in Vietnam. The acquirer, KPMG, is a Swiss entity while the acquired, Andersen, is an American firm. Therefore, this acquisition can be considered as cross-border M&A to some extent.

Managing Partner

BusinessDictionary.com defines ‗managing partner‘ as the highest formal job title given to a senior partner in charge of a company‘s overall practice, management and day-to-day operations. A managing partner is more or less equivalent to a chief executive officer of a firm in terms of duties and responsibilities; yet they manage a partnership and not a corporation. This job title is usually found in law and accounting firms.

Multinational Corporation (MNC)

In World Investment Report 1999, UNCTAD (1999) defines multinational corporations (which it calls transnational corporations) as ―incorporated or unincorporated enterprises comprising parent enterprises and their foreign affiliates‖. A parent enterprise or firm is defined as ―an enterprise that controls assets of other entities in countries other than its home country, usually by owning a certain equity capital stake‖. A foreign affiliate is defined as ―an incorporated or unincorporated enterprise in which an investor, who is resident in another economy, owns a stake that permits a lasting interest in the management of that enterprise‖. Foreign affiliates may be subsidiaries, associates or branches.

Big Four – Big Five

The Big Four (or the Big 4) are the four largest international accountancy and professional services firms that handle the vast majority of audits for publicly traded companies as well as many private companies, creating an oligopoly in auditing large companies. The Big Four firms include PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), Deloitte & Touche (Deloitte), Ernst & Young (EY) and KPMG. (NationMaster.com)

This group was once known as the "Big Eight", and was reduced to the "Big Five" by a series of mergers. The Big Five became the Big Four after the demise of Andersen in 2002. (NationMaster.com)

1.6 Disposition

The structure of this thesis is presented in the figure below. The thesis is divided into six chapters:

Chapter 1 – Introduction. In this chapter, the background to the topic of this thesis is presented. Prior research on the definition and general trend of Mergers & Acquisitions (M&As) is introduced. The emphasis of the study is put on the cultural integration in the M&A process, through the case studies of local integration process between two Multi-national Corporations‘ (MNCs) subsidiaries in Vietnam. Problems explored from the case

studies on the cultural side are discussed, which will guide and fulfil the purpose of this study. Key terminologies are explained to help better understand this thesis.

Chapter 2 – Frame of Reference. In this chapter, the theoretical basis for the thesis is provided. A background information about M&As and the role of culture in M&As are presented at the beginning, followed by the main theoretical section about culture. Levels of culture are introduced with the focus on the role of national and organizational culture in M&As. Hofstede‘s culture dimensions and Schein‘s model along with their limitations are discussed. Culture type approach and desired mode of acculturation are taken into account as a means to conceptualize and evaluate the culture of the two M&A partners and help to identify the possible outcome of the integration. The authors wrap up the chapter with the theoretical discussion, where all previously discussed theories are connected and our own framework is presented.

Chapter 3 – Methodology. In this chapter, the methodological approach is introduced to explain and motivate our chosen scientific approach, and followed by the research method and approach used to analyse the case study. The research design section explains the overall structure and orientation of our research in detail. Data collection is clarified in the subsequent sections.

Chapter 4 – Empirical Study. In this chapter, the empirical data are collected from primary and secondary sources. Primary data is collected through the interviews with four members and surveys, conducted among KPMG and Andersen employees. The chapter starts with a description of two companies and their own culture. A brief history of two firms and the case are then presented. The empirical presentation consists of three themes: values and beliefs, cultural dimensions and processes. First theme – values and beliefs are expressed in the goals of integration. Second theme – cultural dimensions reflect the views of interviewees on the cultural differences and their influences. Third theme – processes indicate how people participate in the integration process.

Chapter 5 – Analysis. The empirical findings are analysed based on our own framework and the three themes introduced in the Empirical Study. First, the authors make a detailed assessment of the culture types of two companies from the survey results, in attempting to determine the cultural compatibility of KPMG and Andersen. The authors make a holistic view on the empirical data to discern the type(s) of ―marriage‖ KPMG and Andersen are engaged in. More detailed analysis is carried out, by exploring various elements in culture that influence the cultural integration between KPMG and Andersen. The elements are from national cultures (USA, Switzerland and Vietnam), and organizational cultures (artifacts and espoused values and beliefs). In the end, the summary with integrated view on this chapter is made.

Chapter 6 – Conclusions.

It could be summarized that the KPMG and Andersen deal resulted in a great loss of ex-Andersen employees, due to the resistance from employees to the new culture after integration. High numbers of employees dropped out of the integration process because they were not satisfied with the KPMG culture, and in this case, if when KPMG lost the highly trained and educated team members, it lost competence and a lot of the value in the company, and thereby fail to achieve one of the goals for the acquisition. Since Andersen

people left, one interpretation could be it is hard to move from a unified/strong culture to a not so strong/unified culture.

.

2

Frame of Reference

To fulfill the purpose and answer the research questions of this thesis, the structure of this chapter is formulated as follows. A background information about M&As and the role of culture in M&As are presented at the beginning, followed by the main theoretical section about culture. Levels of culture are introduced with the focus on the role of national and organizational culture in M&As. Hofstede’s culture dimensions and Schein’s model along with their limitations are discussed. Culture type approach and desired mode of acculturation are taken into account as a means to conceptualize and evaluate the culture of the two M&A partners and help to identify the possible outcome of the integration. The authors wrap up the chapter with the theoretical discussion, where all previously discussed theories are connected and our own framework is presented.

2.1 Mergers and Acquisitions

The terms merger and acquisition are often confused. On the surface, the distinction in meaning may not really matter, since the net result is often the same: two companies (or more) that had separate ownership are now operating under the same roof. Yet the strategic, financial, tax and even cultural impact of a deal may be very different, depending on which transaction is made. (Sherman, 1998) A merger typically refers to two companies coming together (usually through the exchange of shares) to become one. An acquisition typically has one company—the buyer—who purchases the assets or shares of the seller, with the form of payment being cash, the securities of the buyer, or other assets of value to the seller. (Sherman, 1998) Potential merger and acquisition partners are typically identified pursuant to some type of strategic fit. Strategic fit is broadly characterized as similarities between organizational strategies or complementary organizational strategies setting the stage for potential strategic synergy. (Schraeder and Self, 2003)

Mergers and Acquisitions can be divided into ―friendly‖ and ―Hostile‖ activities. In a friendly M&A, the Board of the target firm agrees to the transaction (this may be after a period of opposition to it). Hostile M&As, on the contrary, are undertaken against the wishes of the target firm‘s owners. (Ghauri & Buckley, 2003) Mergers and Acquisitions can be categorized into four main types: (a) Vertical, those of vertical type involve the combination of two organizations from successive processes within the same industry; (b) Horizontal, horizontal mergers and acquisitions involve combinations of two similar organizations in the same industry; (c) Conglomerate, conglomerate refers to the situation where the acquired organization is in a completely unrelated field of business activity; (d) Concentric, in concentric mergers, the organization acquired is in an unfamiliar but related field into which the acquiring company wishes to expand. (Cartwright and Cooper, 1996) When an organization acquires or merges with another, three possible forms of the ―marriage‖ may occur, based on the motive, objective and power dynamics of the combination (Cartwright & Cooper, 1996):

The Open Marriage: in an open marriage the acquirer sees its own role primarily as supporting its acquisition and further facilitating its development and growth, perhaps by providing increased investment (Cartwright & Cooper, 1996). Cartwright & Cooper (1996) note that the essence of the open marriage is that of non-interference, whereby the acquirer is quite happy to allow the acquired

organization to operate as an autonomous business unit and maintain its existing culture. In open marriage, the acquirer keeps the acquired organization intact and culture type matters little (Cartwright & Cooper, 1996).

The Traditional Marriage: in a traditional marriage, Cartwright & Cooper (1996) claim that the acquirer sees its own role as primarily being to redesign the acquired organization. The essence of the traditional marriage is that of radical and wide-scale change, whereby the acquired or ―the other‖ merger partner totally adopts the practices, procedures, philosophy and culture of the acquirer (Cartwright & Cooper, 1996). For the traditional marriage, success depends on the ability of the acquirer to change the culture of the acquired (Cartwright & Cooper, 1996).

The Collaborative Marriage: in collaborative marriage, it is not the case of the ―successful‖ organization taking over the ―unsuccessful‖, but a combination of different but complementary forces, wherein both parties have a contribution to make (Cartwright & Cooper, 1996). The essence of the collaborative marriage is shared learning (Cartwright & Cooper, 1996). In the collaborative marriage success depends on the degree to which the cultures can work together and integrate to create a ―best of both worlds‖ (Cartwright & Cooper, 1996)

2.1.1 Culture in Mergers and Acquisitions

Mergers and Acquisitions have been a significant means for corporate growth, and an important way for international diversification and expansion without incurring extensive start-up costs and delays associated with learning about new markets (Nahavandi & Malekzadeh, 1988) , however, most of the research on M&As has focused on strategic and financial fit between the acquired and acquirer firms (e.g. Nahavandi & Malekzadeh, 1988; Cartwright and Cooper, 1996) and culture in M&As becomes an under-researched area (Cartwright and Cooper, 1996). It is discovered that culture plays a very important role in the outcome of M&As (Cartwright and Cooper, 1996).

Forstmann (1998) mentions that culture, at both the national and organizational levels, is a complicated phenomenon extensively shaping employees‘ practices, beliefs, systems and procedures. It is also true for M&As, where the cultures of two separate organizations are required to interact.

In most M&A context, cultural integration means the successful imposition of the existing culture of acquirer or dominant merger partner on the other rather than the blending of the two (Cartwright, 1998). Companies need to address culture differences early in the M&A process. When cultural differences are not managed, misunderstandings happen and arise between two companies involved, which may endanger the cooperation (Hall, 1995). Unlike mergers and acquisition involving companies in the same countries, other than organizational culture, cross-border mergers and acquisitions have the challenges of coping with national culture. In cross-border M&A, culture is even more difficult to integrate since the two partners are forced to combine not only dissimilar organizational cultures but also different national cultures. Cross-border M&As are more complex because of long distances, different languages, values and traditions which can cause many unpredicted problems. Therefore, it is of critical importance to probe into the definition of culture, different level and types of cultures in order to solve the problems incurred during the cultural integration of cross-border M&As.

2.2 Culture

The concept of culture is very difficult to define in a way that gives a delimited and unambiguous meaning. Culture is defined in many different ways, which cover everything from culture as ―common systems of values, beliefs and norms‖ to the view of cultures as ―shared social knowledge‖ (Alvesson & Berg, 1992). There are wide variations in the combinations of elements included in the definitions of culture. For example, according to Deal and Kennedy (1982), culture is ―the concepts, habits, skills, art, instruments, institutions, etc. of a given person in a given period‖. The most popular definition of culture is probably offered by Hofstede (1991, p.5): ―Culture is a collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another.‖

In the following sections, the authors will introduce different levels and types of culture, mainly focus on national culture and organizational culture, and the implications of culture in M&As.

2.2.1 Levels of Culture

There is more than one culture that can affect a company. It is important to identify and distinguish culture inside the organization and culture on a broader level, such as the industry, region or nation. Alvesson and Berg (1992) mention six levels of culture which are illustrated in Figure 2 below.

Organizational culture Regional and Industrial culture National culture

Professional culture

Department culture

Worker culture

The authors will briefly introduce the different cultural levels:

National culture: is defined as shared values, preferences and behaviors that are specific to the manner people of a nation interact with each other or with an external factor (e.g. doing business or managing companies) (Very, Lubatkin & Calori, 1996; Alvesson & Berg, 1992). Details on national culture will be presented in the next section 2.2.2

Regional culture: the cultures that is built in ―a certain geographical (territory), administrative (jurisdiction), commercial (market) or ethnic (country) area‖ (Alvesson & Berg, 1992, p.67). In their studies regarding this culture, Gustafsson and Gregory both have a basic assumption that a particular region, district or city develops a sense of identity or a special way of thinking or acting in its geographic area (as cited in Alvesson & Berg, 1992, p. 66). They introduce one example of regional culture, which is the high degree of entrepreneurship in Gnosjö (Sweden) and Silicon Valley (California, US) where entrepreneurial value is the basis of the cultural setting (as cited in Alvesson & Berg, 1992, p. 66).

Industrial culture: is a macro-culture from an organizational viewpoint. Many companies in the same industry or sector have much in common when the authors see them from a cultural perspective (Alvesson & Berg, 1992). People within an industrial culture have a shared set of fundamental assumptions, values and beliefs behind the industry‘s institutional logic.

Organization culture: ―basic assumptions and beliefs that are shared by members of an organization‖ (Schein, 1985, p.8). Organizational culture will be described later in section 2.2.3

Subcultures at the Organizational Level:

Though it is often mentioned as if organizations have a monolithic culture, companies are not homogeneous and do not have unequivocal organizational cultures. Most of the firms have more than one set of beliefs that impact employees‘ behaviors, which are called subcultures (Sathe, 1985).

Sathe (1985) mentioned that these different subcultures within an organization may be divided based on occupational, functional, product or geographical lines. Although a company may have a dominant culture, such subcultures may coexist and interplay. Consequently, understanding the culture of any company involves identifying the various subcultures and gaining insight into how they interact to influence organizational behavior and decision making (Malekzadeh & Nahavandi, 1988). Examples of subcultures are Professional culture and Department culture.

Social groups in the Organization: Social groups are those which are set up informally in the organizations. Cultural characteristics of social groups are considered as worker culture. It is believed that the cultural patterns attain the form and character as a result of the opposing interests in worker-management relation (Alvesson & Berg, 1992). Therefore, the social conflicts form the values and ideas of worker culture, lead to or at least have a strong effect on the creation and development of the worker culture (Alvesson & Berg, 1992).

2.2.2 National Culture for Work-Related Values

As introduced by Alvesson & Berg‘s ―level of culture‖, the first and overarching cultural level is national culture. National culture is defined as shared values, preferences and behaviors that are specific to the manner people of a nation interact with each other or with an external factor (Very, Lubatkin & Calori, 1996; Alvesson & Berg, 1992).

Hofstede (1991) has presented perhaps the most comprehensive means to dimensionalize national culture. His IBM research revealed four dimensions of differences among national value systems: Low vs. High Power Distance, Individualism vs. collectivism, Masculinity vs. femininity, Uncertainty avoidance. Michael Harris Bond and his colleagues found a new dimension which was initially named Confucian dynamism. Hofstede then incorporated this into his framework as the fifth dimension: Long vs. short term orientation

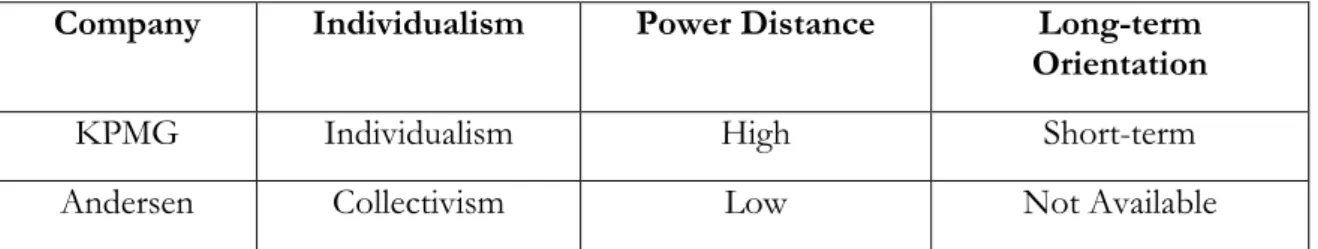

European and US cultures as defined as Western culture in general is perceived to be less distant comparing with Western versus Asian culture like Vietnam. In this case, the national cultures of US and Switzerland are compared in three out of five dimensions as illustrated by Hofstede (1980), which have assumably influenced the people‘s behavior at workplace.

The reasons of selecting the following dimensions over others as a benchmark are 1) relevance; the material provided during the interview and survey are in line with the functions of these three dimensions, therefore, the dimensions used are the appropriate tool to gauge the cultural difference of KPMG and Andersen through the lens of managers and employees. The other two dimensions, i.e. masculinity and uncertainty avoidance, have little relevance with the purpose of this thesis and information provided (the definition is provided below); 2) cultural representation; when talking about national culture, US tops the list of individualism (Hofstede, 2005, Hampden-Turner and Trompenaars, 1993), while Asia has a higher record in both power distance and long-term orientation than that of the west like US and Switzerland. Sine Vietnamese culture plays a major part in the two MNCs, it is important to consider the influence of those traits that Asian countries like Vietnam represents in culture; 3) empirical data; the managers from the two companies the authors interviewed specifically point out that the difference in management style and strategy like long-term orientation and relationship with employees, related to their respective organizational cultures, lead to some problems during integration. Some of the descriptions, even though targeted at their respective organizational culture, are in line with the Hofstede dimensions, specifically those three dimensions.

The other two dimensions from Hofstede the authors choose not to cover are Masculinity versus Femininity and uncertainty avoidance. Hofstede (1997) argues that masculinity ―pertains to societies in which social gender roles are clearly distinct‖ and femininity ―pertains to societies in which social gender roles overlap.‖ In the workplace, Jandt (2004) states that in masculine cultures, managers are expected to be decisive and assertive; in feminine cultures, managers use intuition and strive for consensus. Whereas Hofstede‘s (1980) dimension of uncertainty avoidance means the extent to which people in a culture feel threatened by uncertain or unknown situations. Jandt (2004) argues that cultures strong in uncertainty avoidance are active, aggressive, emotional, compulsive, security seeking, and intolerant; cultures weak in uncertainty avoidance are contemplative, less aggressive, unemotional, relaxed, accepting personal risks, and relatively tolerant.

Cultural Dimension Score

Country Individualism Power Distance Long-term Orientation Switzerland Individualism 68 Low 34 Not Available United States Individualism 91 Low 40 Short-term 29

Vietnam Collectivism 20 High 70 Long-term 80 Table 1: Cultural Dimension Score. Source: Hofstede (2005)

Individualism versus Collectivism

According to Hofstede (1997.p51), individualism refers to the extent to which everyone is expected to look after himself and his immediate family; Collectivism, however, refers to societies in which people from birth and onwards are integrated into strong, cohesive in groups, which throughout people‘s lifetime continue to protect the in exchange for unquestioned loyalty. In a collectivist culture, the interest of the group prevails over the interest of the individual. People are integrated into strong, cohesive in-groups that continue throughout a lifetime to protect in exchange for unquestioning loyalty (Hofstede, 1997). One difference is reflected in who is taken into account when you set goals. In individualist cultures, goals are set with minimal consideration given to groups. In collectivist cultures, other groups are taken into account in a major way when goals are set. Individualist cultures are loosely integrated; collectivist cultures are tightly integrated. (Jandt, 2004)

In the workplace, in individualist cultures, the employer-employee relationship tends to be established by contract, and hiring and promotion decisions are based on skills and rules; in collectivist cultures, the employer-employee relationship is perceived in moral terms, like family link, and hiring and promotion decisions take employee‘s in-group into account. Individualism and collectivism have been associated with direct and indirect styles of communication. In the direct style, associated with individualism, the wants, needs, and desires of the speaker are embodied in the spoken message. In the indirect style, associated with collectivism, the wants, needs and goals of the speaker are not obvious in the spoken message. (Jandt, 2004)

More collectivist societies call for greater emotional dependence of members on their organizations; in a society in equilibrium, the organizations should in return assume a broad responsibility for their members. The level of individualism/collectivism in society will affect the organization‘s members‘ reasons for complying with organizational requirements. The level of individualism/collectivism in society will also affect what type of persons will be admitted into positions of special influence in organizations. (Hofstede, 1980)

US scores 91 ranks first among all countries in terms of individualism. Hofstede (1989) argues that in the US, there is a strong feeling that individualism is good and collectivism bad. Although Switzerland is relatively lower than US. Both countries have a high level of individualism. Vietnam scores very low in individualism, which suggests that Vietnam is a collectivist country with a huge highlight on group decisions and family relationships. Family and community concerns will come before business or individual needs. People are unified in groups, have close ties with family and community, responsible for each other.

Power Distance

Hofstede (1997) defines power distance as ―the extent to which less powerful members of institutions and organizations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed equally‖ Power distance also refers to the extent to which power, prestige, and wealth are distributed within a culture. Cultures with high power distance have power and influence concentrated in the hands of a few rather than distributed throughout the population. These countries tend to be more authoritarian and may communicate in away to limit interaction and reinforce the differences between people. In the high power distance workplace, superiors and subordinates consider each other existentially unequal. Power is centralized. (Jandt, 2004)

According to Mulder‘s Power Distance Reduction theory, subordinates will try to reduce the power distance between themselves and their bosses and bosses will try to maintain or enlarge it.

Luhmann feels that power in organizations is mainly exercised through influence on people‘s careers, but this may be more true in societies and groups in which careers are more important. (Hofstede, 1980)

As can be seen in the table, US has a lower power distance than Switzerland. This is also in accordance with Hofstede‘s theory (1997) that countries with a Romance Language (Switzerland) score medium to high, whereas countries with a Germanic language (English) score low.

Long-term versus short-term orientation

Hofstede (2001.p.359) notes that Long Term Orientation stands for the fostering of virtues oriented towards future rewards, in particular perseverance and thrift, while Short Term Orientation stands for the fostering of virtues related to the past and present, in particular, respect for tradition, preservation of ‗face‘ and fulfilling social obligations. Normally countries with the influence of Confucianism like China, Japan, South Korea and Vietnam has a higher long-term orientation level.

Hofstede (1980) scores US 29 and Vietnam 80 in this dimension, while the data for Switzerland in the regard is not available. It means that Vietnam has a long-term orientation. Considering the influence of Confucianism, it could be assumed that both the US and Switzerland have relatively shorter term orientation.

2.2.2.1 Limitation on Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions

The theory of Hofstede‘s Cultural Dimensions is a great tool to gauge the national culture in each country. Nevertheless, it can be argued that Hofstede‘s cultural dimensions are not universally valid (Gertsen & Søderberg, 1998). It is argued that the five dimensions are offered as tools for comparing important aspects of culture (Hofstede, 1997), aspects that can be of particular importance for management in M&A.

Some researchers argue that national culture, in all its complexity, cannot be captured quantitatively and reduced to four variables. Others may be uneasy with Hofstede's use of a single multinational corporation as a basis for his conclusions about national culture. And still others may point out that national culture is changeable and, even if understood at any single point in time, it is heterogeneous within any given country. (Sivakumar & Nakata, 2001) For example, in a hypothetical case by Sivakumar and Nakata (2001), Mexico and the

U.S. are chosen to represent low and high individualism, respectively. When it is found that Mexican managers are more apt to use participatory management techniques than their American counterparts, collectivism is said to engender this effect.

All these views suggest that Hofstede's theory and findings fall short of being perfect. However, in this paper, Hofstede‘s cultural dimensions are used as a basis to analyze the perceived cultural differences that will result in cultural clashes and exert influence in cultural integration in M&A. Although the topic of our thesis is about cultural integration, the main focus is put on the integration of organizational cultures between KPMG and Andersen. Hofstede‘s cultural dimensions, despite of its limitations, have provided enough back information for linking the influence of national culture on the organizational culture respectively. In addition, the case the authors use in this thesis is with regard to the local integration between two globally merging MNCs‘ subsidiaries. The newly-merged company in Vietnam has been influenced to a certain degree by the Vietnamese culture through the Vietnamese employees, and to a great extent by the Swiss and American professional cultures in the accounting industry, which is perceived as a culture of its own apart from the national culture.

2.2.3 Organizational Culture

Definitions of ―organizational culture‖ are more or less as abundant as those of ―culture‖. Organizational culture is a significant factor in determining an individual‘s commitment, satisfaction, productivity and longevity with an organization (O‘Reilly et al., 1991).

Bate (1984) contends that a ―key feature of culture is that it is shared-it refers to ideas, meanings and values people hold in common‖. Therefore, organizational culture is a means to designate the organization as a collective entity that cannot easily be broken into smaller pieces (Alvesson & Berg, 1992). It is considered as a kind of social or normative glue that holds the organization together.

In this research, the authors have used the concept of Schein, one of the most prominent theorists of organizational culture. He defines organizational culture as the "the basic tacit assumptions about how the world is and ought to be that a group of people share and that determines their perceptions, thoughts, feelings, and, their overt behavior" (Schein, 1996, p.11).

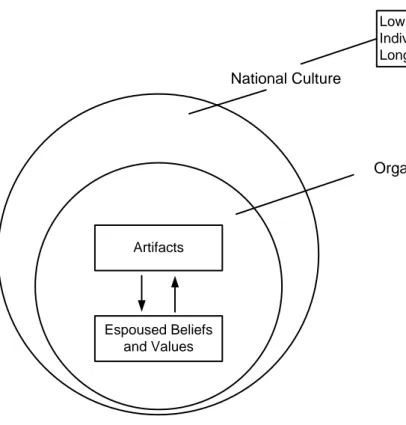

Schein (2004) developed a model to explain the elements of organizational culture (Figure 3). Schein‘s model contains three distinct levels: artifacts, the espoused values, and the basic underlying assumptions. Those levels need to be distinguished to avoid conceptual confusion.

Figure 3: Model of organizational culture. Source: Schein (2004, p.26)

Artifacts

The most visible level of culture is its artifacts, which include visible, tangible or verbally identifiable elements in the organization. Artifacts can be architecture of its physical environment, furniture, dress codes, working environment, level of formality in authority relationships, technology, products, rites, rituals, myths and stories (Schein, 2004). While observing the artifacts is easy, it is very difficult to decipher them, i.e. fully understand what the artifacts mean, why they have been established, how they interconnect and what deeper patterns they reflect (Schein, 2004). The meanings of artifacts will progressively become obvious if the observer lives in the organization long enough. However, to achieve that understanding level more quickly, ―one can attempt to analyze the central values that provide day-to-day operating principles by which the members of the culture guide their behavior‖ (Schein, 1992, p.27).

Espoused Values

When a group faces a new task or issue, the first solution proposed to deal with it which reflects some individual‘s own assumptions is not yet a shared basis among the group members. That individual, usually the founder or leader, may consider the proposed solution as a value or belief based on facts (Schein, 2004). The group may not feel the same degree of conviction until it has taken some cooperative actions and collectively observed the outcome of that action. If the solution succeeds and continues to work in the group‘s subsequent problems, the value will be transformed first into a shared value or belief, and ultimately into a shared assumption (Schein, 2004).

Beliefs and values at this level can predict much of the behavior observed at the artifactual level. According to Argyris and Schön (1978), those values may only be regarded as ―espoused values‖ if they are not based on prior learning. Espoused values predict what

people say in various situations, but which may be out of line with what they will actually do in situations where those beliefs and values should be functioning (Argyris & Schön, 1978).

Espoused values can be found in such places as organizational vision, mission, core values, strategy descriptions, performance standards and expectations, and new employee orientation programs (Schein, 2004).

Basic Underlying Assumptions

In order to fully understand a culture, one has to come to the deepest level, the level of underlying assumptions. The essence of culture is represented by the basic underlying assumptions, which are difficult to determine since they exist at an unconscious level. When a solution to a problem, suggested by a leader or a core group of members, works repetitively, the shared assumptions are reinforced and, gradually become taken for granted, drop out of awareness and be treated as a reality (Schein, 2004). The assumptions are not necessarily correlated to the espoused values, and the espoused values may have no root in the underlying assumptions of the culture (Schein, 2004).

2.2.3.1 Limitation on Schein’s Model on Organizational Culture

Researchers at different time have commented on drawback for the study of organizational culture. Meek (1988) points out that researchers tend to presume that there exists in a real and tangible sense a collective organizational culture that can be created, measured and manipulated in order to enhance organizational effectiveness. A more recent study by Martin (1992) shows cultures are reified as having an objective reality that can be accurately assessed as fitting one of the social scientific perspectives more than the others. Edgar Schein‘s model (2004) is based on the assumption that culture is unitary and can be structured. Therefore, some researchers have challenged Schein‘s model; for example, Hatch (1993) argues that subculture researchers have disputed Schein‘s assumption that organizational cultures are unitary (e.g. Barley, 1983; Borum & Pedersen, 1992; Gregory, 1983; Louis, 1983; Martin & Siehl, 1983; Riley, 1983; Van Maanen & Barley, 1985; Young, 1989, cited in Hatch, 1993). Others argue that the conceptual models of organizational culture have been made on the grounds that they oversimplify complex phenomena (Hatch, 1993)

Schein‘s model of organizational culture is a great tool to analyze the culture of KPMG and Andersen. However, the limitations of his theory should also be considered. In relation to this thesis, for example, the level of basic underlying assumptions that includes unconscious, taken-for-granted beliefs, perceptions, thoughts, and feelings is abstract and intangible, and cannot be utilized as a whole, because everyone especially within the same organization has different perceptions, thoughts, and feelings, which makes the concept of ―culture‖ impossible to gauge. In addition, cautions and limitations in model use are suggested, becauseappropriate use for a particular purpose depends on whetherthe model complexity is appropriate to the question being asked(Boote & Jones & Pickering, 1996). According to purpose of this thesis, the concept of basic underlying assumptions is too general, complex and hard to gauge in practice.

In summary, all the views above suggest that Schein‘ model on organizational culture could not form a perfect representation of organizational cultural analysis, as far as the nature of

model is concerned, and especially for the level of basic underlying assumptions. Owing to the reasons stated above and considering the purpose of the thesis as well as the empirical data provided by KPMG and Andersen, the authors of this thesis choose not to include the level of basic underlying assumptions when analyzing the organizational culture of both companies.

2.2.3.2 Culture Types

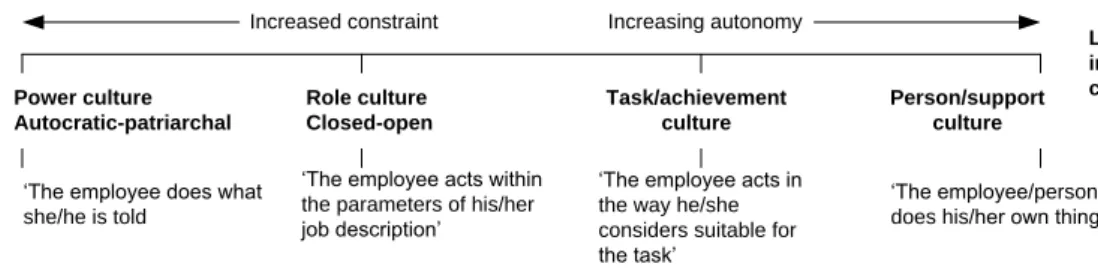

According to Harrison (1972), there are four basic culture types (i.e. power culture, role culture, task/achievement culture, person/support culture) for organization, and one must consider the degree of similarity/dissimilarity between them. Therefore, in order to discern the differences, the relationship between culture types is established in terms of the degree of restraint they place on individuals. (Figure 4)

Power culture Autocratic-patriarchal Role culture Closed-open Task/achievement culture Person/support culture

„The employee does what she/he is told

„The employee acts within the parameters of his/her job description‟

„The employee acts in the way he/she considers suitable for the task‟

„The employee/person does his/her own thing‟ Increased constraint Increasing autonomy

High individual constraints Low/no individual constraints

Figure 4: The relationship between culture types in terms of the degree of restraint they place on individuals. Source: Cartwright & Cooper (1996)

It is not so much the distance between the two parties that was important, but the direction in which the other culture has to move. Cultural similarity is therefore not a prerequisite to the success of the traditional marriage (Cartwright & Cooper, 1996).

Power Cultures

In this culture type, employees tend to ―attend‖ the organization out of financial necessity, rather than any deeper feelings of attachment arising from any sense of active involvement or deeper organizational attachment (Cartwright & Cooper, 1996). It is said that in power cultures, employees are expected to accept that ―the boss knows best‖; they impose a high level of constraint on the individual, and therefore they tend to invoke a superficial compliance-based level of organizational commitment from their members (Cartwright & Cooper, 1996). In M&As, Cartwright & Cooper (1996) again argue that power cultures are potentially more easily displaced than any other culture type, and are likely to be willing partners to any traditional marriage with an acquiring/dominant merger partner of another culture type.

Role Cultures

Comparing with power cultures, role cultures impose less constraint on the individual. Therefore, role cultures are generally experienced as being more satisfying and are less likely to be relinquished (Cartwright & Cooper, 1996). In M&As, if a traditional marriage involves the acquisition of a role culture by a power culture, the acquirer/dominant partner

is likely to encounter considerable resistance to change, argued Cartwright & Cooper (1996). Conversely, role cultures are likely to be willing partners to any traditional marriage with an acquirer or dominant merger partner with a less constraining task or person/support culture, according to (Cartwright & Cooper, 1996).

Task/achievement Cultures

In M&As, because task cultures are generally experienced by their members to be highly satisfying and invoke a high degree of commitment, they do not make ―ideal‖ or acquiescent partners to traditional marriage involving power or role cultures (Cartwright & Cooper, 1996).

Person/support Cultures

According to Cartwright & Cooper (1996), because person/support cultures offer the individual the opportunity for self-actualization, their members are likely to resist any culture change. Besides, person/support cultures are more difficult to displace than any other culture type, and are likely to be unwilling partners to any traditional marriage with an acquiring/dominant merger partner of another culture type.

2.3 Acculturation

As two firms engaged in the M&As share different organizational cultures, influenced by their respective national culture, histories and different goals and objectives, it is unlikely that two firms will totally fit, therefore, some authors argue that it is not a question about whether the firms fit or not, but merely whether they want to have a cultural fit (Teerinkangas & Very, 2006). If firms want to have this cultural fit, cross-border M&As pose a higher challenge towards this integration process, since the international character is very likely to bring people, with different values and beliefs about the work place and behaviour, together due to the influence of national culture (Salama et al. 2003).

Considering the purpose of this thesis, the acculturation process in M&As is introduced. ―Acculturation‖ is defined as changes induced in (two cultural) systems as a result of the diffusion of cultural elements in both directions (Nahavandi & Malekzadeh, 1988). It is argued in Nahavandi & Malekzadeh (1988) that acculturation acts as an adaptation process through which conflicts between two cultures are reduced either by integration, separation, assimilation or deculturation. This process also means that, due to interaction between the merging or acquiring parties, out of two cultures one joint culture will arise. (Salama et al. 2003; Larsson & Lubatkin, 2001)

In this thesis, the authors choose and present Cartwright & Cooper (1996) model of modes of organizational and individual acculturation in M&As, adapted from Nahavandi and Malekzadeh‘s (1988).

According to Cartwright & Cooper (1996), to anticipate whether the combination is likely a good culture match, people have to consider the likely wider response of the employees of the acquired firm. Many M&As face serious problems because one of the partners holds a very dissimilar perception of the other‘s culture (Cartwright & Cooper, 1996). It is extremely important that in an integration situation, organizational members should make assessments and draw conclusions about the ―other culture‖ (Cartwright & Cooper, 1996).

In order to assess the cultures of ―the other‖ party, two factors will be taken into account (Cartwright & Cooper, 1996):

- The extent to which employees experience their own culture as worth preserving. - The extent to which employees perceive the cultures of ―the other‖ to be attractive. The implications of this cultural evaluation process in terms of potential outcomes for the firm are presented in Figure 5

Willingness of employees to abandon their old culture

Very willing Not at all willing

Very attractive Perception of the attractiveness of KPMG culture Not at all attractive Assimilation Potentially smooth transition Deculturation Alienation Integration Satisfactory integration/ fusion Culture v collision Separation Satisfactory tolerance of multi-culturalism Culture v collision

Figure 5: Modes of organizational and individual acculturation in M&A, and its potential outcomes. Source: Cartwright & Cooper (1996)

As per model above, individual is likely to decide:

That he/she prefers the ―other‖ culture to his/her existing culture, and thus is willing to abandon his/her own culture and absorbed completely into the culture of ―the other‖. If the majority of members of one partner have this evaluation, assimilation will occur. (Cartwright & Cooper, 1996)

That he/she has a strong desire to preserve his/her own culture and identity while perceiving the ―the other‖ culture attractive. As a result, he/she would like to maintain many of the basic assumptions, beliefs, cultural elements, and organizational practices and systems that make them unique, and at the same time and is willing to incorporate some aspects into his/her existing culture. If the majority of members of one partner have shared this evaluation, integration will occur. Nevertheless, integration has a high potential for culture collisions because successful integration requires change and balance between two cultural groups which rarely happens in reality. (Cartwright & Cooper, 1996)

That he/she wants to preserve own culture and refuses to become assimilated with ―the other‖ culture and would not wish to change. If ―the other‖ partner is not ready to respect this desire and is intolerant of multiculturalism, any effort to change that culture

will face substantial resistance. If the majority of members of one partner have shared this evaluation, separation will happen. If the separation is accepted by the other party, culture collisions would unavoidably happen. (Cartwright & Cooper, 1996)

That he/she does not value his/her own culture, and they do not perceive ―the other‖ culture as attractive at all. If the majority of members of one partner have the same evaluation, deculturation will take place. (Cartwright & Cooper, 1996)

Cartwright & Cooper (1996) stated that deculturation, unsanctioned separation and unsatisfactory integration leading to culture collisions and fragmentation had a negative effect on M&A outcomes.

Nahavandi & Malekzadeh (1988) argued that integration at the cultural level requires contact between employees of the two firms. The M&A integration may affect the members of the acquired firm most strongly since they are often expected to adapt to the culture and practices of the acquirer (Jemison & Sitkin, 1986; Sales & Mirvis, 1984). Besides, according to Lubatkin (1983), employees' willingness to adapt to the culture and practices of the other merging partner has been suggested to be one of possible obstacles for achieving the desired synergies in any integration. Therefore, the authors applied this model in order to understand the integration in terms of its potential outcomes and how members of the acquired company would like to acculturate to the acquirer.

2.4 Theoretical Discussion

The theories have been chosen in order to enable the authors to work on the cultural integration in M&As and achieve the research purpose. Along with a background information to the study such as introduction of M&A concept and possible forms of ―marriage‖, in order to answer the research questions, the authors focus mainly on the theories of culture and cultural integration, including levels of culture, national culture, organizational culture, culture types and acculturation process.

Based on the discussed theories, the authors developed a framework which would help to assess and analyze the cultural dimensions in M&A integrations (See Figure 6).

National Culture

Organizational Culture

Low vs High Power Distance Individualism vs Collectivism Long-term vs Short-term orientation

Espoused Beliefs and Values

Artifacts

Figure 6: Cultural Dimensions in M&A Integration

The framework illustrates two different levels which have a great influence on the organizations: national culture and organizational culture. Among six levels of culture introduced by Alvesson and Berg (1992), two are chosen because they match the purpose of the study which is primarily connected to national culture and organizational culture. Furthermore, those cultures are two of the corporate areas which have rapidly gained tremendous attention, popularity and academic respectability (Alvesson and Berg, 1992). In terms of national culture, the authors apply three out of five dimensions presented by Hofstede (1991), including Individualism versus Collectivism, Power Distance and Long-term versus short-Long-term orientation. As discussed above, the reasons for choosing these three dimensions are the relevance of collected data and these dimensions‘ functions, cultural representation with high ranking of relevant countries in three dimensions, and specific empirical data indicating the need for analysis.

Silverthorne (2005) states that national culture and organizational culture play a simultaneous and important role in an organization. Gulev (2009) mentions that culture of a country where an organization is founded impacts its organizational culture. However, since ―most of the variance in organization cultures cannot be explained by country‖ (Gerhart, 2009, p.2), the authors take organizational culture into consideration by including ‗artifacts‘ and ‗espoused beliefs and values‘ in our framework. ‗Artifacts‘ and ‗espoused beliefs and values‘ are two out of three levels of organizational culture suggested by Schein (2004). The third one, ‗underlying assumptions‘, is not applied since it represents a deep level of culture that is hard to capture with the methods used.

In M&As, the existing pre-combination cultures of the two partners has a major role in determining M&A outcomes (Cartwright & Cooper, 1993). There is a complex interaction between the two existing types of culture during the integration process. Cartwright and Cooper (1993) affirm that different cultural types generate different psychological