J

Ö N K Ö P I N GI

N T E R N A T I O N A LB

U S I N E S SS

C H O O LJÖNKÖPI NG UNIVER SITY

Sickness absence

in Sweden

A s t u d y o f e a r l y r e t i r e m e n t

a n d s i c k n e s s a b s e n c e

Bachelor Thesis in Economics

Authors: Marcus Wollbratt 1980-10-09 Maja Najafi 1985-03-14

Bachelor Thesis in Economics

Title: Sickness absence in Sweden. A study of early retirement and sickness absence.

Authors: Marcus Wollbratt and Maja Najafi

Tutors: Lars Pettersson, Charlotta Mellander and Peter Warda

Date: Fall 2007

Key terms: Sickness compensation, social norms, incentives, Moral Hazard, Ad-verse Selection, labour supply, sickness absenteeism, early retirement

Abstract

The purpose of this thesis has been to analyse seven major factors that tend to influence the rate of early retirement in Sweden. The scope of data was gathered for every municipality in Sweden. Economic theories of labour supply, Moral Hazard, Adverse Selection and the In-surance Model were used to analyse the empirical results. In the analysis, earlier studies of the rate of sickness absence were important and used as a framework in choosing the ex-planatory variables for the econometric model. The analysed variables were; average in-come, average sickness days, educational level, foreign born, public sector employment, un-employment and the share of women in the population. As a consequence of the rift that occurred in 2003, when the average sickness days decreased and disbursed early retirements simultaneously increased, the relationship between these two variables was given special at-tention. The empirical findings confirmed our conjectures and were consistent with earlier research. Average income and the level of education were negatively related to the rate of early retirement. Moreover foreign born, average sickness days and unemployment showed a positive relation to early retirement. The relationship between average sickness days and early retirement had statistically changed and decreased between the years. A possibility is that other factors, such as changed social norms and increased stress in society (which are difficult to measure in a statistical and economical sense) might have become more relevant in explaining the rate of early retirement.

Kandidatuppsats i Nationalekonomi

Titel: Sjukfrånvaro i Sverige. En studie av förtidspensionering och sjuk-frånvaro.

Författare: Marcus Wollbratt and Maja Najafi

Handledare: Lars Pettersson, Charlotta Melander and Peter Warda

Datum: Hösten 2007

Nyckelord: Sjukförmån, sociala normer, incitament, Moral Hazard, Adverse Se-lection, arbetsutbud, sjukskrivning, sjuk- och aktivitetsersättning

Sammanfattning

Syftet med denna uppsats har varit att analysera sju viktiga faktorer som tenderar att påverka graden av förtidspensionering i Sverige. Data omfånget insamlades för alla kommuner i Sve-rige. Ekonomiska teorier om arbetsutbud, Moral Hazard, Adverse Selection och Insurance Model användes för att analysera de empiriska resultaten. I analysen var tidigare studier utav graden av sjukfrånvaro viktig och användes som ramverk i valet av de förklarande variabler-na till den ekonometriska modellen. De avariabler-nalyserade variablervariabler-na var; medelinkomst, genom-snittliga sjukdagar, utbildningsnivå, utlandsfödda, offentligt anställda, arbetslöshet och ande-len kvinnor i befolkningen. Som en konsekvens utav den klyfta som uppstod 2003, när de genomsnittliga sjukdagarna minskade och utbetalda förtidspensioner samtidigt ökade, gavs sambandet mellan dessa två variabler speciell uppmärksamhet. De empiriska iakttagelserna bekräftade våra förväntningar och stämde överens med tidigare forskning. Medelinkomst och utbildningsnivå var negativt relaterade till graden av förtidspensionering. Dessutom var utlandsfödd, genomsnittliga sjukdagar och arbetslöshet positivt relaterade till förtidspensio-nering. Relationen mellan de genomsnittliga sjukdagarna och graden av förtidspensionering hade statistiskt sätt ändrats genom att ha minskat mellan åren. En tänkbar förklaring till det-ta skulle kunna vara att andra faktorer, såsom skifdet-tande sociala normer och en ökande stress i samhället (vilka är svåra att mäta statistiskt och ekonomiskt) kan ha blivit mer relevanta i att förklara graden av förtidspensionering.

Table of Contents

1

Introduction and background ... 1

1.1 Research problem ...3

1.2 Purpose and method ...5

1.3 Outline ...5

1.4 Limitations ...5

2

Earlier research... 6

3

Theoretical framework... 12

3.1 Neoclassical Labour Supply Model...12

3.2 Moral Hazard, Adverse Selection and the Insurance Approach ...16

4

Data and Empirical Findings ... 18

4.1 Data problems ...18

4.2 The dependent variable...18

4.3 The explanatory variables ...19

4.4 Descriptive statistics ...21

4.5 Modelling ...22

4.6 Variable correlations...23

4.7 Empirical findings ...25

4.8 Early retirement and sickness days ...28

5

Conclusion ... 30

References ... 32

Appendices ... 35

Appendix 1 - Heteroscedasticity...35

Appendix 2 - Multicollinearity...36

Appendix 3 - 2001 Ordinary least square regression results...37

Appendix 4 - 2001 Weighted least square regression results ...38

Appendix 5 - 2005 Ordinary least square regression results...39

Figures

Figure 1-1 Average sickness days between genders in Sweden Figure 1-2 Social insurance system of sickness compensation

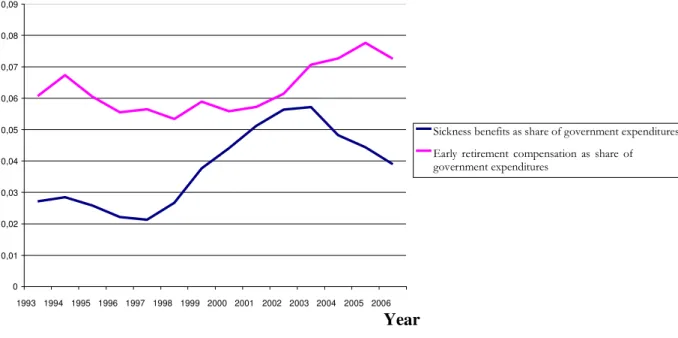

Figure 1-3 Compensation for sickness and early retirement in Sweden (as share of government expenditures) 1993-2006

Figure 2-1 Unemployment and sickness days per year (1987 – 2009) Figure 2-2 Relationship of income and probability of being sick absent Figure 3-1 Basic labour supply with indifference curves and constraints Figure 3-2 Basic labour supply with an increase in hourly wage rate Figure 3-3 basic labour supply with specified employment contract

Figure 3-4 Basic labour supply with introduction of sickness compensation Figure 3-5 Individual indifference curves modelled with work and

absence income

Figure 4-1 The β value of average sickness days with confidence intervals in order to explain sickness and activity compensations

Tables

Table 4-1 Descriptive statistics

Table 4-2 Correlation matrix for the variables in 2001 Table 4-3 Correlation matrix for the variables in 2005

Table 4-4 The effects of the explanatory variables on the number of monthly disbursed Sickness and Activity compensations

Equations

Equation 1 Utility function Equation 2 Time constraint Equation 3 Budget constraint Equation 4 Work income Equation 5 Absence income

1

Introduction and background

In 2006 the Swedish national health insurance cost taxpayers 3000 SEK per second1. The

Swedish sickness rate is one of the highest in Europe (Swedenborg, 2003). The increase of sickness absence and early retirement compensation is a highly debated topic in Sweden and has dominated the welfare state debate (Johansson and Palme, 2004). Between 1995 and 2005 the number of people with long-term sickness absence increased with nearly 100 per-cent. In 2005, almost 17 percent of the Swedish labour force was reported to be absent from work due to long-term sickness (Selander, 2006). The most logical presumption ought to be that the Swedish general health is decreasing. However according to the Human De-velopment Index, Sweden is considered to be one of the healthiest countries in the world (Human Development Report 2006). According to the Swedish National Insurance Agency there has been a statistical persistent decrease in the rate of sickness absence since 2003. Figure 1-1 represents the annual development of average reported sickness days in Sweden. The difference between genders is noticeable. Since the 1980s women have had a higher rate of sickness absence than men and the gap has increased. A possible explanation to this in-consistency might be that women are overrepresented in public employment institutions, in which the working environment has gotten worse over time. They also encounter a more difficult labour market than men do (RFV, 2001:5). The labour market affiliation was sub-stantially strengthened in the 1980s and forward. The growth of labour market affiliation among women has been especially strong (Social Welfare Agency, 2001).

Figure 1-1 Average sickness days between genders in Sweden

1 The total expenses (104 billion) spent on the general sickness insurance and early retirement compensation in

2006 expressed in seconds. (Swedish social insurance agency)

0,0 5,0 10,0 15,0 20,0 25,0 30,0 35,0 1955195719591961196319651967196919711973197519771979198119831985198719891991 1993199519971999200120032005 Year (1955-2006) Average number of reported sickness days (per year and employee)

Men and women Women Men

Generally if a person becomes ill, they will be offered sickness compensation from the social insurance system in Sweden. The sickness compensation is based upon annual individual in-come and is presently set at 80 percent of that inin-come (RFV “Sjuk”, 2007). The thought is to guarantee a stable income, however a substantially lower one, which will encourage an indi-vidual to return to work as soon as possible (Selander, 2006). The Swedish sickness insur-ance has been revised and reformed several times2. In 1998 the compensation for sickness

absence was set at 80 percent of reported income and during the whole period of sickness leave. In the beginning of the millennium the rules were made more stringent.

In January 2003 the rules of early retirement was changed, what used to be called the early retirement, was now called sickness and activity compensation. While the previous system was part of the Swedish National Pension Fund, the new system became a part of the Na-tional Medical Insurance System. Furthermore, the lowest age of receiving the right to com-pensation was lowered from 19 years to 16. The insured has the right to be compensated when they have lost at least a quarter of their working capacity. If the insured is older than 30 years the compensation is called sickness compensation and if the insured is younger than 30 years, the compensation is referred to as activity compensation. The activity compensa-tion is time limited from one to tree years. Early retirement and sickness and activity com-pensation are basically the same concept, although the notions have changed; in this thesis we will use the names interchangeably.

Concerning the general sickness compensation, in 2003 the level of compensation was low-ered from 80 to 77.6 percent and the sickness salary compensated by employers was in-creased to 21 days, from 14 days. The next change occurred in 2005, when the compensation was raised back to 80 percent and the employer financed sick leave period back to 14 days. In addition to this, a new form of sickness insurance fee called co-financing was introduced. The co-financing implied that the employers were obliged to pay 15 percent of the employ-ees’ benefits also after the mandatory 14 days. (Ekonomistyrningsverket, 2005; The Swedish National Insurance Agency, 2007). Figure 1-2 illustrates the basic insurance system.

Source: Author’s own creation

Figure 1-2 Social insurance system of sickness compensation

There is always a qualifying day before you are entitled to compensation. If you have been employed for at least one month or worked consistently for 14 days, you have the right to sickness salary from your employer during the first 14 days. After one week of compensation an individual are obliged to get a certificate of sickness from a doctor, to stay in the system. After two weeks of employer compensation you get transferred to the insurance agency’s compensation system. If the sickness is prolonged, investigation procedures for rehabilita-tion are organized. If there is cause to transfer you to the early retirement system you will get compensation from that system. According to the Swedish national insurance agency (RFV, “Sjuk”, 2007), when an individual is entitled to sickness compensation, the agency actively investigates if it is possible to transfer them from the sickness system to the system of sick-ness and activity compensation3 (early retirement), at the latest one year from the notice.

1.1 Research problem

The increased rate of sickness is a serious problem in Sweden, since the expenditures for fi-nancing the national health insurance are a substantial part of the governmental budget and very costly. According to the National Budget Outturn in 2006, the expenditures for the sickness and early retirement pensions accounted to 13.2 percent out of total governmental expenditures (The National Budget Outturn, 2006)4. It is also a serious problem since it

holds back labour supply and potential production growth (National Institute of Economic Research, 2003).

There has been a statistical persistent decrease in the rate of average sickness days since 2003. It can be seen in Figure 1-3 on the next page, that in 2003 the long-term sickness leave decreased for the first time in several years, however this was mostly due to an increased rate of people transferred to the early retirement system (Ekonomistyrningsverket, 2005). In 2003, the number of people on early retirement compensation went beyond half a million for the first time in Sweden. Those transferring to early retirement from the sickness insur-ance system are getting younger and younger and the rate is increasing more for women than among men. (FHI R2004:15) So what is the reality of this? Could one conclude that the ear-lier so sick Swedish people are getting “healthier” or is this basically a statistical illusion?

3 Sickness and activity compensation is the new system which acceded that of early retirement pension in 2003.

When referring to this system the terms will be used interchangeably.

4 Out of the total government expenses (791.9 billions) in 2006 roughly 104 billion SEK was spent on the

Source: Social Insurance Agency, Statistical Unit, Regular Annual Statistics

Figure 1-3 Compensation for sickness and early retirement in Sweden (as share of government expenditures) 1993-2006

In prosperous economic times the demand for labour is very high and people that previously could not get employment get employed, which could contribute to a higher rate of sickness absence (Hemmingsson, 2004). As can be seen following the favourable economic situation in the late 1990s the rate of sickness absence substantially increased until 2003. In 2003 aver-age sickness days decreased, simultaneously as the rate of early retirement increased.

Following the rift that occurred in 2003, between disbursed early retirements and average sickness days, we got interested in analysing the source of this inconsistency. There are nu-merous factors that could explain the rate of early retirement. However, psychosocial factors such as attitudes and social norms are hard or impossible to measure. So what measurable factors could have been important in explaining the rate of early retirement in Sweden? Has the particular rate of average sickness days changed in explaining the rate of early retire-ments? 0 0,01 0,02 0,03 0,04 0,05 0,06 0,07 0,08 0,09 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 Year s

Sickness benefits as share of government expenditures Early retirement compensation as share of government expenditures

1.2 Purpose and method

The purpose of this thesis is to analyse how; average income, average sickness days, educa-tion, foreign born, public sector employment, unemployment and the share of women, influenced the sickness and activity compensation in 2001 and 2005. In particular if the in-fluence of average sickness absence had changed before and after 2003. The data are gath-ered for all municipalities in Sweden, in this way we get an all-embracing data collection. We use cross-sectional regressions5 in order to compare and analyse possible differences be-tween year 2001 and 2005.

1.3 Outline

To begin with, a solid ground of earlier research is presented in chapter 2. This is done in order to give a better understanding of what tend to affect the sickness rate in Sweden and which variables that could be important to include in our analysis, based on earlier studies. In chapter 3, a theoretical framework of worker absenteeism and insurance systems is pre-sented. In chapter 4, the data and empirical findings are brought forward. Chapter 5 con-clude the thesis with a discussion of the empirical analysis and suggestions for further re-search. The statistics are presented more thoroughly in the accompanying appendixes.

1.4 Limitations

In this study we will limit ourselves to analyse the difference between two specific years. In 2003, average sickness days decreased simultaneously as the early retirement increased. To analyse differences before and after this rift, the years 2001 and 2005 were chosen. After careful considerations, we have chosen seven variables6 to explain the rate of early retirement

(sickness and activity compensation). Even though there are a vast amount of possible influ-ences on the sickness rate, including too many variables would give problems with autocor-relation and/or multicollinearity. As a consequence, we have chosen seven measurable fac-tors that according to earlier research could be important in explaining the sickness rate in Sweden.

5 Cross-sectional regression is a regression model that is associated with a specific point in time. 6 For a complete presentation of the chosen variables see Appendix 7.

2 Earlier research

The increasing rate of sickness and early retirement compensations in Sweden, have become a very serious issue in the society. It holds back labour supply, decreases potential produc-tion and deteriorates public finances (Naproduc-tional Institute of Economic Research, 2003). In this chapter, important aspects and earlier research of the sickness absence in Sweden will be presented.

Social standards and sick leave

According to Lindbeck (2003) all social insurance systems have some common problems. Over utilization refers to the problem of Moral Hazard, as some individuals adapt their be-haviour to self generate an insurance case. Furthermore there are problems with cheating the system or fraud. It is important to differentiate between cheating and Moral Hazard. Report-ing sick due to Monday agony is Moral Hazard, but travellReport-ing on vacation provided by the insurance compensation is cheating. The reasons to offer sickness insurance is indisputable and justified, however the more generous the conditions are, the more people will conse-quently abuse these compensating systems. When explaining the increase of the sickness rate, Lindbeck brings forward three possible explanations. The changing demographics of the labour force, with an ageing labour force and an increased rate of women working, is one factor. Another factor is how generous rules could partly explain the increased sickness rate. The final factor could be the deterioration of working environments. Those prone to this explanation refer to the increase in mental stress on the individual, which could lead to psy-chological ill health.

Social standards or norms might have become less important with time (Lindbeck, 2003). Sticking to a social norm gives a good reputation, while violating a norm gives a bad reputa-tion. Before we had a well functioning welfare state, the inherited social norms implied that an individual fit for work ought to provide for their income by themselves and not live out of the contributions of others. As our society experienced a transition to our known welfare state, it got easier for individuals to support themselves without working. As this becomes clear, some individuals might abuse these social insurances and violate social norms. The more people that neglect the social norms, the easier it will be for others to violate them. These social norms are becoming weaker with time and with passing generations. Following this, the problem of Moral Hazard and cheating will become more explicit.

The set of regulations and sick leave

Persson (2003) analyse how changes in the set of regulations of the insurance systems could affect the sickness rate. In prosperous economic times the sickness reporting increases and in recessions it decreases. The terms of the set of regulations might be a very important fac-tor in explaining changes in the sickness rate. A very strong correlation between sickness compensation and sickness absence was found. When the generosity increases, the sick ab-sence increases as well. The research showed that long-term effects of changes in the set of regulations are larger than the short terms effects.

Johansson and Palme (2004) researched the dilemma of Moral Hazard and sickness insur-ance. The study shows how the ability of workers to affect their use of sickness insurance

creates a Moral Hazard situation, in which workers are driven by the economic incentives such as a generous sickness benefit system. It is argued that due to the fact that you only need a physicians’ certification of illness in the eighth day of absence, it is only the tion of an individual health status that is required for the first sickness reports. The percep-tion to perform regular work is affected by economical incentives. They found that control mechanisms are effective in dealing with Moral Hazard in the insurance system. When ana-lysing reforms of the system, it is concluded that Moral Hazard indeed resides in the Swedish sickness insurance system. Following this there is a trade-off between a generous insurance system and the behaviour of individuals to such a system. Insurance systems that are favour-able (that have high compensation and low control) tend to attract high risk individuals (SBU, 2003).

Persson and Henrekson (2004) studied how changes in the sickness insurance could affect the rate of sickness absence. It was found that changes in the compensation level had a very strong effect on the sickness absence behaviour. They also established that there are differ-ences between men’s and women’s responses to these changes. Women tend to be more af-fected by economical incentives than men are.

Work environment and sick leave

Statistical results do not indicate that the physical working environment has become worse in Sweden. However there are several indicators on the psychosocial level that suggest an in-creased level of stress on the individual. It appears as the working life demands even more of the individual. In general it has become much more stressful and mentally strenuous in the working environment. This has presumably to do with the continuous attempts to increase the productivity through changes in work organizations. The number of individuals that are defined as inactive and incapable of working has substantially increased and this increase is strongest in regions with major labour market problems. During recessions, people with problems are cleared from the labour market and consequently it appears to be easier to stay on that market in times of prosperity. In general, people are left outside the labour market at an increasing rate. Employed individuals are increasingly reported sick, both in short and long terms. Furthermore there are fewer opportunities for people with problems to find a way back into the working community. (Wikman, 2004)

Backhans (2004) suggest that one possible cause to the high sick rates in Sweden is the reor-ganization and restructure of the working environment that was strong during the 1990’s. It is further suggested that sick leave might be used more frequently as a permanent exit from the labour force, especially for older women that are hard to reorganize. Individuals in caring professions and in the public sector have an extra risk of getting long term sick reported. Selander (2006) studied what kind of economic incentives that could be important in getting sick absent workers to return to work. He believes that motivation is the key factor for workers to return to work, and that the best motivation is different economic incentives.

Unemployment, business cycle and sick leave

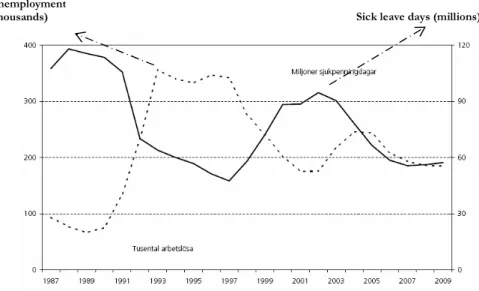

In prosperous economic times the demand for labour is very high and people that previously could not get employment get employed. Corresponding to this, in recessions the competi-tion on the labour market get fierce and the ability of individuals to actually work receives more focus. According to Hemmingsson (2004) the number of sick reporting in Sweden has substantially increased since the late 1990s and forward. Simultaneously with this increase the business cycle improved and demand for labour got higher. Hemmingsson further ex-plains that during recessions individuals hesitate to report sick, as it might induce a higher risk of getting unemployed, referred to as the “disciplinary effect”. He continues to state that a known fact is that the general health is worse for unemployed than for employed individu-als and the risk of getting long term sick increases with age. During the recession in the be-ginning of the 1990’s, sick reporting decreased drastically. It is noted that the decrease in sick reporting following the 1996-97 period, can partly be explained by that sick and elderly peo-ple were put outside the working force. The relationship between unemployment and sick leave days are presented in Figure 2-1, out of which 2005 to 2009 are estimations.

Source: The Swedish National Financial Management Authority (2005)

Figure 2-1 Unemployment and sickness days per year (1987 – 2009)

Only small displacements in the set of regulations could drive up the number of sick reports. It is difficult to bring back individuals with health problems to work (Hemmingsson, 2004). Vogel et al. (1992) suggests that during times of high employment, people with poorer health get access to the labour market. As a consequence of this, these individuals tend to contrib-ute to the substantially higher rate of sickness absence. Edling (2005) suggests in a contro-versial report, that early retirement has been used as a labour market measure. In general, the higher unemployment is in a municipality, the higher would also the early retirement be. Early retirement is a compensation system that could conceal the lack of employment op-portunity at a given location. A strong correlation between unemployment and early retire-ment was found in this study.

Sick leave days (millions) Unemployment

Fraud and sick leave

The Swedish National Insurance Agency7 estimates that 1.2 - 3.6 billions are wrongfully paid from the sickness insurance system. According to the Swedish Delegation Against Benefit Frauds and Errors (FUT, 2007), the sickness and early retirement compensation, are the two public insurance systems that constitutes the largest erroneous payments. It is estimated that 7.1 billions SEK is wrongfully paid from the two systems. There could also be a large unre-corded number, due to the apparent lack of control in these systems. It is important to keep analyzing and putting further control into these systems. The experts in the FUT study (2007) conclude that these systems are highly risky in respect to fraud. In an article in Finan-cial Times8, the chairman of the FUT, Björn Blomqvist, implies that the Swedish welfare

sys-tem is very generous and people have a great incentive to abuse the syssys-tem. He continues to add that Swedish people are much more prone to cheat the system today, than 30 years ago.

Gender and sick leave

Women have had a higher sickness rate than men ever since the 1980s. Out of total sick ab-senteeism roughly two thirds are estimated to be women, (RFV, 2004). The fact that women tend to have a higher sickness rate than men is well known and consistent with many coun-tries with various insurance systems. Over time the gap between genders has increased in Sweden. Long-term sickness due to psychological reasons has increased over time and this increase has been substantially higher for women than for men. Backhans (2004) suggests that there might be gender differences that could explain these differences among men and women. Biological differences as such should not be able to suggest that women are more affected by sickness. Women with a highly demanding work have a higher risk of being sick reported. The difference between genders is somewhat paradoxical; women have a higher sickness rate than men; however men have a lower life expectancy. Different kind of work and working environments might be the reason explaining the increasing gap between men and women. (RFV, 2004)

Women have a substantially worse position on the labour market than men; they are also subject to bad physical and psychosocial working environments. In public employments such as caring professions and educational occupations women are overrepresented, since the 1990s that working environment has gotten worse. (RFV, 2001:5)

7 Social insurance agency, “Felaktiga utbetalningar och brott mot socialförsäkringen – omfattning, risker och

in-formation” (2007-08-31)

Foreign Born and sick leave

In Sweden, native and foreign born individuals have different rates of sickness absence. For-eign born women and men have a relatively weak position of the Swedish labour market and in general foreign born individuals have a worse health than natives. The difference in sick-ness absence might partly be explained by differences in basic health. Moreover by the fact that the labour market situation is worse for foreign born individuals, (Bengtsson and Scott, 2005). Nilsson (2005) analyses the effects of nativity on the rate of sickness reporting. Meas-uring the length of absence, immigrants are more absent due to sickness than natives are. However, when comparing the number of sickness absences per individual, the difference is not that noticeable. Foreign born women respond more strongly to economical incentives and changes in the set of regulations, than native women do.

Educational level and sick leave

There is a clear correlation between the level of education and the rate of sickness absence in Sweden. In general, when comparing individuals with only tertiary education against highly educated individuals, individuals with a higher education are less likely to be absent due to sickness. People with only a high school degree have the highest rate of sickness absence in Sweden. The individuals with the lowest rate of sickness absence are native men with a higher education. (Integrationsverket, 2006) Women with only an elementary education are more likely to be subject to an early retirement, than highly educated women are (Marklund, 1995).

Income and sick leave

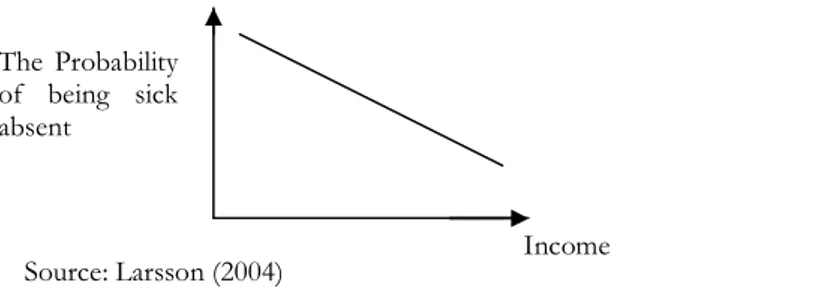

Health and income are positively related. Generally, as income increases the probability of getting sick decreases. This relationship is described in Figure 2-2, showing a negative rela-tionship between income and the probability of getting sick.

Figure 2-2 Relationship of income and probability of being sick absent

A higher income could result in a better health and possibly fewer sickness reports. Larsson (2004) proposes that an increase in income could generate two contradictory effects. The health effect (higher salary, less sick reporting) and the incitement effect (higher salary, more sick reporting). Which effect that would be dominant cannot be concluded in priori and de-pends on the given situation.

Income Source: Larsson (2004)

The Probability of being sick absent

Sickness- and activity compensation and sick leave

Those transferring to the early retirement system from the sickness insurance system are get-ting younger and younger and the rate is increasing more among women than among men (FHI R2004:15). The statistical rate of average sickness days has decreased since 2003, how-ever at the same time those transferring to the early retirement system have increased. This is not surprising according to the Swedish National Insurance Agency9, as a large number of

long-term sick, allows more individuals the right to an early retirement.

Burnout and sick leave

Effects and preventions of burnout are discussed in Krauklis and Schenström (2001). Burn-out is considered to be a mentally painful condition that develops over a long period of time and resulting from chronic stress. The cause of stress is a constant high mental and emo-tional burden at work and/or home. Common symptoms of burnout are mental, emoemo-tional and physical exhaustion. More than the majority of the individuals with burnout condition are also suffering from depression. If one suffers from these symptoms the chance for total recovery and a way back into the working life is hard to achieve. It is even hard for individu-als that suffer from burnout to manage their private life. The cause of burnout is suggested to be injustice, conflicts and high expectation at work. Chronic stress is reported to be the one of the highest growing diseases in Sweden, and it is one of the most common reasons for sick reporting. Backhans (2004) support the fact that long terms sickness due to mentally caused diseases have increased over time.

Doctors’ diagnosis and sick leave

Hallqvist (2003), a medical officer and insurance doctor, puts attention to the responsibility of doctors. Behind every sum of money spent on the sickness compensation, there is a doc-tor certificate. Hallqvist claims that a lot of individuals, who are absent due to sickness, actu-ally are not sick in pure medical terms. Hallqvist argues, that if every doctor followed the set of regulations rigorously and only reported an individual sick when there is a medically proven diagnosis, the number of sick reported individuals would decrease.

Nilsson Bågeholm (2003) argues that a lot of the reasons and diagnoses behind sickness re-porting are ambiguous. Reasons for the high rate of sickness absence in Sweden, does not correspond to known diseases in the society. When individuals get sick reported it is often without a proper and objective medical diagnosis. It is often the case that doctors sick re-ports a patient with symptom diagnoses that are based on the patients’ own experience of the symptom. Individual symptoms that in many cases cannot be treated medically. The legal agency (and the doctors) definition of diseases does not hold with the publics. Nilsson Bågeholm argues that the biggest problem that exists today is the lack of collaboration be-tween the doctors, the social insurance offices, the employers and other authorities.

9 The Swedish National Insurance Agency, press release: 26/04, 2004-07-16, “Färre sjukskrivna men fler

3 Theoretical framework

3.1 Neoclassical Labour Supply Model

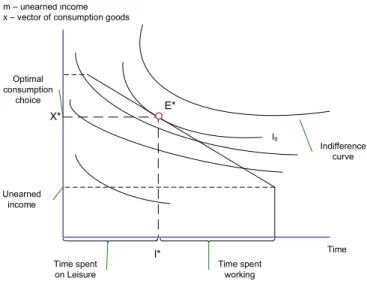

Absence of labour supply have continuously been analysed according to the Neoclassical Labour Supply model (Brown and Sessions, 1996). People are suppliers of labour and ac-cording to microeconomic theory people want to maximise their utility functions. In the ba-sic labour supply model utility is determined by income and leisure. The baba-sic utility function would be expressed as:

U= u(x, l) (1)

Utility being a function of x (vector of consumption of goods, which demands work) and l (leisure). The utility function is constrained by the time constraint of an individual, since every day has 24 hours which has to be divided between work and leisure.

T= (h + l) (2)

Where h is working hours and l is leisure and constrained by the budget constraint.

x ≤ m = m0 + Wh (3)

Where x is a vector of consumption goods, m0 is unearned income and W the exogenous

real wage.

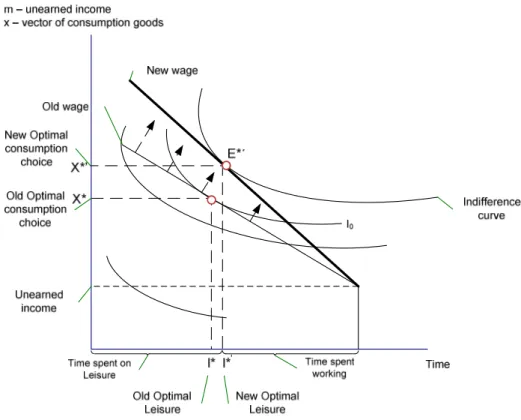

Following this there is a trade-off between allocating hours to work or to leisure. The utility function is modelled with indifference curves which will indicate the optimal utility solution following the constraints. The slope of the indifference curve is called the marginal rate of substitution (MRS) between leisure and consumption. The slope of the budget constraint is the opportunity cost of leisure and equal to the negative of hourly wage (-W). Equilibrium in this condition would arise where the W equals the MRS (tangency of indifference curve and wage), at E*, x* and l* in Figure 3-1.

Indifference curve Time spent working Time spent on Leisure Optimal consumption choice Unearned income E* X* l* I0

Source: Brown and Sessions (1996) m – unearned income

x – vector of consumption goods

Time

A change in the hourly wage rate has both an income and a substitution effect. If wage in-creases then the price of leisure inin-creases as well, by the substitution effect this would yield an individual to work more. However by the income effect, an individual earns more and consequently would prefer more leisure. Which of these effects that is dominant depends on an individual’s utility (indifference curve). In Figure 3-2 we see how the increase in wage causes leisure to increase, however consumption increases relatively more (and the income effect is dominant) and we find ourselves at the “new optimum” at E*’, where consumption increases to x*’ and leisure increases to l*’.

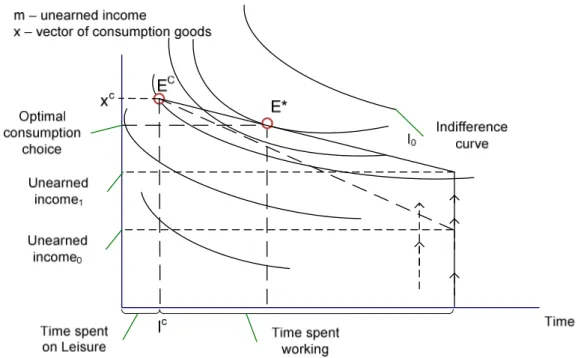

If employment contracts are included in the framework (most individuals cannot freely choose the hours worked) one may see a different story. If per se the contract specifies hours to be worked the individual would accept this contract as it still yields more utility then without working. In fact, according to Brown and Session (1996), absence in this model can only be defined if the number of hours to be worked is specified in the contract. Following this reasoning when accepting the number of hours to be worked we find ourselves at a new equilibrium point at Ec in Figure 3-3, with consumption at xc and leisure at lc.

Indifference curve Time spent working Time spent on Leisure Optimal consumption choice Unearned income EC E* lc xc I0

Source: Brown and Sessions (1996) m – unearned income

x – vector of consumption goods

Time

Figure 3-3 basic labour supply with specified employment contract

In this contractual framework, an individual’s optimal MRS (the slope of the indifference curve) exceeds its economic rate of substitution at E*. This would presumably give an indi-vidual a desire to take some absence to get closer to their optimal point E* from Ec. Absence

arises from the difference between an individual’s MRS and the economic rate of substitu-tion of contractual work hours. A change in the individual’s marginal rate will affect the in-centives to be absent. It is expected that when leisure is highly valued the MRS will be par-ticularly high. Absence arises from the fact that an individual is unable to freely decide on the number of hours to work (as they are restricted by employment contracts) and this implies an incentive to absence oneself. Absence increases as the contractual working hours in-creases. In this framework absence is penalized basically by lost earnings.

The Neoclassical Model has been extended in many different directions (SBU, 2003) and it is likely that at least some of an individual’s income loss is offset by sickness compensation, which could increase the incentives to be absent according to Brown and Session (1996).

Assuming that the sickness compensation is less than wage (s < w) we see how the change in Figure 3-4 is that the unearned income0 increases and we get a new level of unearned

in-come1, which makes the slope of the budget constraint to flatten out. The personal

dispos-able income increases.

Figure 3-4 Basic labour supply with introduction of sickness compensation As compensation still is less than wage, hours will be spent working. The effect of an intro-duction of compensation (s < w) suggest that each hour of absence entitles some compensa-tion. The budget constraint will pivot at Ec as before, but the introduction of sickness

com-pensation will cause incentives to increase absenteeism. A possible movement from Ec to E*

represent the substitution effect and the income effect, both which suggestively increases ab-senteeism. It is more likely to be absent with sickness compensation than without. As long as the sickness compensation is less than wage (s < w) the worker will use some time to work, but as Brown and Sessions (1996) suggests an interesting scenario and paradox arises if the sickness compensation would be the same as wage (s = w). In term of the model this would give the individual an incentive to fully absent themselves, but even if this would hold true, real life data shows that an individual do not use up their whole sick leave. Since a prediction of fulltime absence is contradictory, economical models have incorporated non-economical and long-term costs for the absentee. Such costs might be reduced opportunities for further education or wage increase, and possibly a higher risk of getting unemployed. Such an eco-nomical model would look at employee absence as a function of their value of leisure, con-sumption, work hours, wage and absence compensation. (SBU, 2003)

3.2 Moral Hazard, Adverse Selection and the Insurance

Approach

Moral Hazard is referring to a situation when an insurance holder might adapt their behav-iour and self generate an insurance outcome. For example, when an individual has sickness insurance they might neglect their health in a way that otherwise would be counterproduc-tive and risk full. Hence the term Moral Hazard in the insurance approach refers to a situa-tion where the distribusitua-tion of risk changes an individuals’ behaviour. Moral Hazard in the in-surance case refers to a possible increased risk of immoral behaviour that would have a nega-tive hazardous effect, hence Moral Hazard. The problem of Moral Hazard occurs because the insured does not bear the full liability or in some cases no consequences at all for their behaviour. The insured may even benefit from their problematic behaviour. Ways to pre-vent Moral Hazard could be to include deductibles, co-payment and co-insurance, so that the insured get economical incentives to avoid possible risk taking. The concept of asymme-try of information is linked to the term Moral Hazard. Asymmeasymme-try of information in insur-ance markets refers to the situation when the insurer is limited or unable to observe the be-haviour of the individual that is insured. (Arrow, 1971)

In basic microeconomics and the insurance industry, adverse selection is a situation when in-effective or negative results are the result of asymmetry of information, which exists between the insurers and insurance takers. In the case of insurance, the problem of adverse selection could make insurance institution to end up dealing with “problematic” costumers. Suppose that there are two kinds of groups in the society, the first group consists of individuals that exercise and the other group consists of non-exercising individuals. An insurance company that sells life policies cannot tell which group a specific individual belongs to and thus each insurance taker is offered an equal and averaged insurance premium. The group of individu-als that exercise are more likely to live a longer and healthier life; those whom do not exer-cise are more likely to have a worse health. As a consequence the proposed life policy is a better option for beneficiaries that do not exercise. The insurance company will learn that the rate of mortality of the combined groups will exceed that of the exercising population of the society, and sets the premiums accordingly to that information. Resulting from this, the group of individuals that exercises will be better off without insurance, however if there were an insurance that were more suitable to their characteristics they would be better of being in-sured. This situation results in a market failure, due to adverse selection. Adverse selection implies that, due to lack of private information, the non-insured individuals are likely to suf-fer more than the insured individuals.

Xa

Xg

In the basic insurance model an individual can choose between two situations as trying to maximize their utility, go to work or being absent. Both actions generate different incomes and the utility is a function of those incomes. With insurance, work income (Xg) is a func-tion of income y and less the premium (P) to be paid for the insurance. Absence income (Xa) include the loss of not working L and the compensation I. Utility is modelled with indi-vidual indifference curves towards the different types of incomes (Xa, Xg) as in Figure 3-5.

Xg = y-P (4)

Xa = y-P-L+I (5)

Source: Rikner (2002)

Figure 3-5 Individual indifference curves modelled to work and absence income

In the original model optimal compensation for absence is full compensation. But as indi-viduals are different in their willingness to transfer possible gains of working to being absent, the indifference curves are different for each individual. The optimal compensation for ab-sence under these conditions includes deductibles. However when the efforts of the insured to work can be observed by the insurer the optimal solution is once again full compensation. By making efforts, it is suggested that an individual can by eating healthy, exercise and avoid-ing infection make an effort to stay healthy enough to go to work. But this optimal outcome is ambiguous, since it is very hard to reach due to factors of Moral Hazard and adverse selec-tion. Moral Hazard leads to lower welfare in general and market imperfections. By the level of compensation the insurer can influence the behaviour of the insured. However too high deductibles (lower compensation relative to wage) are inefficient too, since people might work when they are still sick. The adverse selection problem is also due to asymmetry of in-formation, but of the inherent characteristics between high-risk and low-risk individuals. The perfect solution would be to provide separate insurance contracts to these different indi-viduals. But this cannot be done if the groups cannot be separated from each other. Market imperfection arises as high-risk individuals tend to get their optimal insurance, but low-risk individuals get no insurance at all. (Rikner, 2002)

4 Data and Empirical Findings

An often occurring theme in the research of sickness absenteeism is to include a number of variables in a regression and try to explain the sickness rate from the resulting beta (β) val-ues. This will be done by using the rate of early retirement as dependent variable. In the at-tempt to explain the rate of early retirement we carefully chose seven explanatory variables. The choices of explanatory variables were based on the earlier research discussed in chapter 2. We analysed how the corresponding beta values changed between 2001 and 2005. The re-lationship between early retirement and average sickness days were particularly analysed. We have gathered our data for two consistently years (2001 and 2005) and for all of the 29010

Swedish municipalities. This means that we have the total data span.

4.1 Data problems

The problem with heteroscedasticity is common with cross-sectional data (Gujarati, 2003) and since the data is gathered for different municipalities that are very unevenly distributed, it was no surprise to find such problems in the data for both years. From the White’s test problems with heteroscedasticity11 was detected. As heteroscedasticity makes the Ordinary

Least Square (OLS) estimators inefficient, a Weighted Least Square (WLS) regression was used to avoid any potential problems (Gujarati, 2003). Since the data is regional from 290 different municipalities in Sweden, we used the subsequent population figures, as an analytic weight in the SPSS12 WLS regression. When examining the regression results, as expected,

some degree of multicollinearity13 was detected. The tolerance levels of the coefficients were

far from a 0.1 critical level and none of our variables were close to a Variance Inflation Fac-tor (VIF) value of 10. There was no need to correcting this issue, as a suggested remedy to multicollinearity is actually to do nothing (Gujarati, 2003), excluding some variables can re-sult in possible specification bias.

4.2 The dependent variable

In year 2003 the long-term sickness leave decreased for the first time in several years, how-ever this was mostly due to an increased rate of people transferred to the early retirement system (Ekonomistyrningsverket, 2005). The sickness and activity compensation is expressed in the number of monthly disbursed compensations (in December), for each year (2001 and 2005) and every municipality (the Swedish Social Insurance Agency).

10 In 2001 there were 289 municipalities, since 2003 a part of Uppsala were divided into a new municipality

called Knivsta, so in 2005 we have 290 municipalities.

11 See Appendix 1 for further notes on the heteroscedasticity problems. 12 SPSS – 14.0 for windows. Statistics software used to run our regressions. 13 See Appendix 2 for a discussion.

4.3 The explanatory variables

The Swedish population has not experienced any deterioration of its general health at all in recent decades. Contrary to that, the facts are supporting an improvement of the health, combined with a longer life span (FHI R 2004:15). There is a general consensus that there are many and complex reasons behind sickness absence, following this we have carefully chosen seven variables that earlier research are referring to as important in explaining the rate of sickness absence. All data are accounted for on total municipality level.

Average Income

A higher income could result in a better health and less sickness absence (Larsson, 2004). The income statistics measures the average source of income, per resident and municipality. All figures are in Swedish SEK (Statistics Sweden). Average income was expected to be negatively correlated to early retirement, since a higher income could give an individual a better opportunity to take care of their health (Larsson, 2004). A higher income would also imply a higher opportunity cost of absence.

Average sickness days

This variable was measured in the average number of days with sickness compensation, per registered insured, year and municipality. This figure excludes individuals that have been transferred to the early retirement system (with a lasting reduced ability to work). An advan-tage of this figure is that it excludes the sickness compensations that are disbursed by the employers (the shorter period of illness, up to 14 days) (Swedish Social Insurance Agency). We were particularly interested in analyzing the effect of this variable in comparison to those of early retirement. When an individual is long-term sick reported the social insurance agency actively investigates if it is possible to transfer the long-term sick to the early retire-ment system instead. It is expected that the average sickness days would be positively corre-lated to early retirement.

Educational level

Research has shown that individuals with a high education tend to be less absent from work due to sickness (Integrationsverket, 2005) and women with only an elementary education are more likely to be subject to an early retirement (Marklund, 1995). This variable measure how many individuals that have three or more years of post-secondary school education, in every municipality (Statistics Sweden). In order to get an efficient quotient for this variable, this factor was divided by the labour force in each municipality. Education ought to have a negative correlation with early retirement, since a higher education not only suggests a higher income, but also a different kind of occupation with different kind of body burden.

Foreign Born

Immigrants tend to be more absent due to sickness than natives (Nilsson, 2005). This vari-able reflects the share of foreign born residents out of total municipality population (Statis-tics Sweden). Sweden has a relatively large share of foreign born individuals, these individu-als originate from diverse nations and backgrounds. Earlier research (Bengtsson and Scott, 2005) suggests that the health of foreign born individuals is worse than natives; they are also subject to a more difficult labour market and possibly some degree of discrimination. From these suggestions, it would not be surprising to see that the rate of foreign born individuals would be positively related to the rate of early retirement.

Public Employment

Employees in the public sector have a higher rate of sickness absence (Backhans, 2004). This variable measures the share of the labour force that was employed in public employment in-stitutions for every municipality and year (Statistics Sweden). The public sector employment is traditionally a sector that employs a lot of women and often in the caring professions, where strain on the body could be intense. As a benchmark it is expected that the number of employed in the public sector, could be positively correlated to early retirement.

Unemployment

During times of high employment people with poorer health get access to the labour market and these individuals could presumably contribute to the higher rate of sickness absence (Vogel et al., 1992). This variable is measured in the percentage share of the labour force that are unemployed and in business cycle contingent programs (Statistics Sweden). The figures are presented for every municipality and chosen year. Hemmingsson (2004) suggests that the health of unemployed individuals is worse than for those under employment. It is suggested that early retirement even is used as a labour market measure and conceals unemployment (Edling, 2005). It would not be surprising to see that unemployment would be positively re-lated to early retirement.

The share of women in the population

Roughly two thirds of all sickness absentees are estimated to be women (RFV, 2004). The fact that women tend to have a higher sickness rate than men is well known and consistent with many countries with various insurance systems. This variable measures the percentage share of women out of total municipality population. The figures are presented for every municipality and chosen year. As women traditionally have had a higher rate of sickness ab-sence than men, it is expected that the rate of women would be positively correlated to the rate of early retirement.

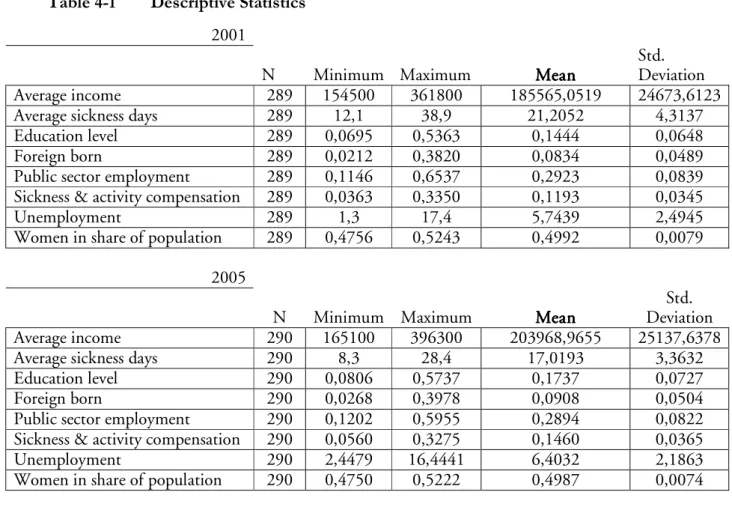

4.4 Descriptive statistics

To increase the relevance of the analysis and to better understand the upcoming regression results it is important to examine how the explanatory variables have developed in Sweden during the period of 2001 to 2005.

Between 2001 and 2005 there were several interesting developments. In 2003 the average sickness rate decreased for the first time in several years in Sweden, simultaneously the rate of early retirement increased (Ekonomistyrningsverket, 2005). As can be seen in the descrip-tive statistics in Table 4-1, the sickness and activity compensation increased with roughly 22 percent during the years, simultaneously the average sickness days decreased with almost 20 percent.

Table 4-1 Descriptive Statistics 2001

N Minimum Maximum MeanMean MeanMean

Std. Deviation

Average income 289 154500 361800 185565,0519 24673,6123

Average sickness days 289 12,1 38,9 21,2052 4,3137

Education level 289 0,0695 0,5363 0,1444 0,0648

Foreign born 289 0,0212 0,3820 0,0834 0,0489

Public sector employment 289 0,1146 0,6537 0,2923 0,0839

Sickness & activity compensation 289 0,0363 0,3350 0,1193 0,0345

Unemployment 289 1,3 17,4 5,7439 2,4945

Women in share of population 289 0,4756 0,5243 0,4992 0,0079

2005

N Minimum Maximum MeanMean MeanMean

Std. Deviation

Average income 290 165100 396300 203968,9655 25137,6378

Average sickness days 290 8,3 28,4 17,0193 3,3632

Education level 290 0,0806 0,5737 0,1737 0,0727

Foreign born 290 0,0268 0,3978 0,0908 0,0504

Public sector employment 290 0,1202 0,5955 0,2894 0,0822

Sickness & activity compensation 290 0,0560 0,3275 0,1460 0,0365

Unemployment 290 2,4479 16,4441 6,4032 2,1863

Women in share of population 290 0,4750 0,5222 0,4987 0,0074

Average income increased with 9.92 percent and there were also an increase in the rate of education equal to 20.28 percent. Moreover, the share foreign born has increased with 8.89 percent and public sector employment slightly decreased with 0.99 percent. Unemployment increased with 11.48 percent during the years, while the share of women marginally de-creased.

4.5 Modelling

The econometric model is presented in Equation 4-1. It states that the rate of sickness and activity compensation is a function of average income, education, foreign born, public sector employment, average sickness days and unemployment. Each variable is measured for every municipality in Sweden (i) and for the years 2001 and 2005 (t).

The model is in logarithm (log-log form), since this will provide elasticises. Using a log-log model is useful, since the slope of the coefficient β would measure the elasticity of the de-pendent variable, in respect to each explanatory variable; the percentage change in sickness and activity compensation for a given small percentage change in any of the explanatory variables (see Gujarati, 2003).

ε β β β β β β β α Women ln nt Unemployme ln days sickness Average ln employment sector Public ln born Foreign ln Education ln income Average ln on compensati activity and Sickness ln 7 ti 6 ti 5 ti 4 ti 3 ti 2 ti 1 ti + + + + + + + + = ti o (6) (t = time) (i = municipality)

4.6 Variable correlations

To commence the analysis and the empirical results, the correlation between all the variables were examined. This is done both, to see if any of the explanatory variables are too corre-lated with each others and also to examine how strong the correlation of the explanatory variables are to the dependent variable (sickness and activity compensation/early retirement). Although there are obvious correlations among several of the explanatory variables, none of them exceeded the critical level of 0.7 (Tabachnick & Fidell 2001). The correlations for 2001 are accounted for in Table 4-2.

Table 4-2 Correlation matrix for the variables in 2001

Sickness and Average Average Education Foreign

Public

sector Unemployment

Share of women in All variables are

in Ln (log)

activity

compensation income

sickness

days level born employment population Sickness and activity compensation 1 Average income -0.675** 1 Average sickness days 0.624** -0.411** 1 Education level -0.450** 0.636** -0.341** 1 Foreign born -0.267** 0.451** -0.473** 0.263** 1 Public sector employment 0.506** -0.471** 0.303** 0.066 -0.259** 1 Unemployment 0.718** -0.670** 0.396** -0.284** -0.314** 0.620** 1 Share of women in population -0.350** 0.389** -0.283** 0.631** 0.277** 0.111 -0.180** 1

** Correlation significant at the 0,001 level (2 tailed)

Several of the explanatory variables show a strong correlation to the dependent variable in 2001. Sickness and activity compensation (early retirement) showed a strong correlation with; unemployment (0.718), average income (-0.675) and average sickness days (0.624). Public employment (0.506), education (-0.450), share of women in population (-0.350) and foreign born (0.267) also had a relative strong correlation to early retirement.

Table 4-3 Correlation matrix for the variables in 2005

** Correlation significant at the 0,001 level (2 tailed)

In 2005, the explanatory variables also showed a strong correlation to the dependent variable (sickness and activity compensation). However the correlations had somewhat changed be-tween the variables. Sickness and activity compensation (early retirement) showed a strong correlation with; average income (-0.716), unemployment (0.661), education (-0.551) and av-erage sick days (0.535). The correlation with public employment (0.439), share of women in the population (-0.361) and foreign born (-0.208) had a relative strong correlation to early re-tirement as well.

Sickness and

activity Average Average Education Foreign

Public

sector Unemployment

Share of women in All variables are

in Ln (log) compensation income

sickness

days level born employment population Sickness and activity compensation 1 Average income -0.716** 1 Average sickness days 0.535** -0.425** 1 Educational level -0.551** 0.585** -0.321** 1 Foreign born -0.208** 0.247** -0.462** 0.266** 1 Public sector employment 0.439** -0.457** 0.250** 0.052 -0.163** 1 Unemployment 0.661** -0.599** 0.388** -0.217** -0.193** 0.595** 1 Share of women in population -0.361** 0.359** -0.229** 0.655** 0.243** 0.0745 -0.164** 1

4.7 Empirical findings

In Table 4-4, both the ordinary least square (OLS) and the weighted least square (WLS) re-gression results are accounted for14. The WLS regressions are used to avoid the problem of heteroscedasticity, which could lead to misleading conclusions (see Gujarati, 2003). Conse-quently only the WLS regressions are analysed. In the WLS regressions, population was grouped per municipality and worked as an analytic weight to adjust for the uneven distribu-tion of residents in Sweden.

The coefficients and their standard errors somewhat differed between the WLS and OLS re-gressions, but in general they showed a similar pattern. All the explanatory variables, except public sector employment and the share of women, turned out to be significant with rela-tively strong t-values in the WLS regressions. The adjusted and regular R2 values were high in both years, indicating that relatively much of the variance in the dependent variable was ex-plained by the model. There are significant differences between 2001 and 2005.

Table 4-4 The effects of the explanatory variables on the number of monthly

disbursed Sickness and Activity compensations

Variables

OLS

WLS

(all in Ln (log))

β 2001

β 2005

β 2001

β 2005

Average income

-0.526*

(-3.631)

-0.468*

(-3.668)

-0.364*

(-2.946)

-0.549*

(-4.781)

Average sickness days

0.566*

(10.532)

0.320*

(6.072)

0.585*

(12.292)

0.296*

(5.446)

Education

-0.048

(-1.146)

-0.233*

(-5.906)

-0.091*

(-2.790)

-0.208*

(-5.886)

Foreign born

0.118*

(5.836)

0.066*

(3.329)

0.130*

(7.830)

0.047*

(2.459)

Public sector employment

0.130*

(2.883)

0.120*

(2.967)

0.032

(0.890)

0.032

(0.899)

Unemployment

0.222*

(7.611)

0.245*

(6.837)

0.253*

(9.935)

0.221*

(5.982)

Share of women in

population

-2.205*

(-3.039)

-0.234

(-0.311)

-1.042

(-1.640)

1.130

(1.421)

Observations

289

290

289

290

R

20.735

0.698

0.781

0.711

R

2Adjusted

0.728

0.691

0.776

0.703

a t-values are presented in brackets

b WLS – weighed by population * Significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Average income was negatively correlated with early retirement in both years. In 2001 a one-percent increase in average income decreased the number of disbursed sickness and activity compensations on the average with -0.364 percent. In 2005 that same decrease for a one per-centage increase in average income was -0.549 percent. The negative correlation substantially increased during the years. From the descriptive statistics (Table 4-1) we noticed that average income saw a relative increase of nearly 10 percent during the years. As income increases an individual gets more resources to live a healthier live, this is referred to as the health effect (Larsson 2004). Furthermore, a higher income implies a different kind of job with a different kind of attrition. As income increases, the opportunity cost of absence could increase as well, the substitution effect could induce an individual to work more and avoid absence (Brown and Session, 1996). As a consistent negative relationship is found, the substitution effect of higher income seemed to be the dominant effect, related to the theory of labour supply. Early retirement is a sort of final step away from the labour market, as average income in-creases, the rate of early retirement decreases. A high income might imply that it is favour-able to continue working, even though an individual might be eligible to early retirement. The effect of average income had significantly increased between the years, presumably the level of income have become more important into giving incentives not to resort to an early retirement and consequently to stay on the labour market.

As was expected, an increase in the average sickness days consequently increased the rate of early retirement. All else equal, a one-percentage increase in average sickness days would re-sult in an increase of the early retirement on the average with 0.585 percent in 2001 and in 2005 that same effect had been reduced by half to 0.296 percent. The rate of average sick-ness days increases the rate of early retirement (RFV, 2004). The more individuals that are sick would consequently explain an increased rate of people transferred to the early retire-ment system15. However, as was the case in 2003, we saw how the average sickness days

de-creased simultaneously as the rate of early retirement inde-creased. Those transferring to the early retirement pension are getting younger and younger and the rate reveals that more women than men are entering early retirement (FHI R2004:15). The elasticity of the coeffi-cient decreased between the years, this might be due to the fact that other factors have be-come more relevant in explaining early retirement. The decreasing effect might very well be due to the fact that the rate of average sickness days decreased during 2001 and 2005 (see Table 4-1). In section 4.8 this relationship will be analysed more thoroughly.

Education turned out to be negatively correlated with early retirement. In 2001 a one-percentage increase in education decreased the dependent variable on the average with -0.091 percent and in 2005 with -0.208 percent. The education rate has increased with ap-proximately 20 percent during the years 2001 and 2005; this might be a possible explanation to why the effect has increased so strongly. A higher level of education traditionally indicates a higher level of income and a different kind of employment (often with less strain on the human body) and thus possibly better health. Individuals with a high degree of education are less likely to be absent from work. Individuals with only an elementary education are the group that are most sickness absent, (Integrationsverket, 2005). It could be the case that a highly educated population might encounter a more favourable position on the labour

15 The Swedish Social Insurance Agency, press release 26/04, 2004-07-16, Riksförsäkringsverket, “Färre

ket and consequently easier to get employment as well. A high education is often combined with a so called “desk job” employment. With such an employment, it might be easier to stay on the labour market for a longer period of time, as compared to a physical strenuous em-ployment.

The rate of foreign born had a positive effect on early retirement in both years. In 2001 a one percent increase in the rate of foreign born would increase disbursed early retirements on the average with 0.130 percent and in 2005 with 0.047 percent. It is no surprise that eign born individuals have a tougher position on the labour market, moreover in general for-eign born have a worse health than natives (Bengtsson and Scott, 2005). It is interesting to note that we have seen a relative increase of foreign born individuals in Sweden. However its effect on early retirement has substantially decreased during the period. If this is due to a better Swedish integration policy and/or a better position on the labour market is hard to tell.

The rate of unemployment was consistently positively related to early retirement. A one per-cent increase in unemployment would on the average increase the disbursed early retire-ments with 0.253 percent in 2001. In 2005 that increase in the dependent variable was 0.221 percent. Hemmingsson (2004) suggests that sickness reporting tend to increases when the business cycle improves, which it has done during these years, the health of unemployed in-dividuals are worse than for those inin-dividuals that are under employment. Edling (2005) also found a strong correlation between unemployment and early retirement and suggested that early retirement is used as a labour market measure and conceals some unemployment. The relationship between unemployment and early retirement is apparent. In municipalities that have a high rate of unemployment, the rate of early retirement is also substantial and follows a somewhat similar pattern, as was suggested by Wikman (2004).