What Affects Motivation? A Study of

Students’ Attitudes towards ESL Learning

in Swedish Lower Secondary Schools

COURSE: English for Subject Teachers 91-120, 15 credits WRITER: Jesper Lindberg

EXAMINER: Jenny Malmqvist SUPERVISOR: Anette Svensson TERM: Spring 2020

What Affects Motivation? A Study of Students’ Attitudes towards ESL

Learning in Swedish Lower Secondary Schools

Jesper Lindberg

Abstract

This study investigates how different educational activities affect students’ motivation and how teachers can induce students’ motivation to learn English as a second language (ESL) in Swedish lower secondary schools. Data was gathered through a questionnaire and analyzed through a sociocultural perspective. In the questionnaire, which was handed out to students in ages 13 to 15 at three different schools, the participants had to indicate if they become motivated or unmotivated by certain activities or if the activities do not have any impact on their motivation.

The results indicate that the activities which most students become motivated by are likely to also be encountered outside school. These are activities such as watching a film, playing Monopoly, listening to a song, chatting online, playing a computer game or video game, or having a conversation with a close friend. In contrast, the activities which most students become unmotivated by are task- or fact-oriented activities which are likely to be encountered inside school or in work-related situations in their future adult life, such as holding a presentation, writing news articles, doing work-sheets and reading word lists with grammar exercises and glossary, or participating in job interviews.

The results also show that students in Swedish lower secondary schools have positive attitudes towards ESL learning in general and that there are many similarities between the different schools regarding what students find motivating and non-motivating. Thus, the results do not encourage eliminating certain educational activities from the learning process. However, in order to induce students’ motivation for ESL learning, teachers could increase the use of activities that many of their students find motivating and decrease the use of activities that many of their students find non-motivating.

Key words: English as a second language, second language teaching and learning,

motivation, student attitudes, educational activities

Table of Contents

1 Introduction ... 1

2 Background ... 2

2.1 Motivation for and Attitudes towards Second Language Learning ... 2

2.2 Educational Approaches in Second Language Education ... 3

3 Aim and Research Questions ... 5

4 Method and Material ... 5

4.1 Questionnaire ... 6

4.2 Ethical Principles ... 7

5 Theoretical Framework ... 8

5.1 Sociocultural Theory in Second Language Education ... 8

5.1.1 Zone of Proximal Development ... 9

5.1.2 Scaffolding ... 9

5.1.3 Community of Practice ... 9

6 Results ... 10

6.1 The Most Motivating Activities: School A, School B, School C ... 12

6.2 The Most Non-Motivating Activities: School A, School B, School C ... 14

7 Analysis and Discussion ... 16

8 Conclusion ... 18

9 References ... 21

10 Appendix ... 24

10.1 Questionnaire Results (Total) ... 24

10.2 Questionnaire Results (School A) ... 25

10.3 Questionnaire Results (School B) ... 27

1

1 Introduction

In my previous study “Educational Approaches & Strategies for ESL Teaching in Swedish Compulsory Schools”, the aim was to find out which methods many teachers in Swedish lower secondary schools use when teaching English (Lindberg, 2019). In this study, the aim is to find out how different educational activities affect students’ motivation to learn English. The results of my previous study are therefore taken into consideration when outlining the procedures for this one. According to the EF English Proficiency Index, which is an annual ranking of countries by their level in English, Sweden was in 2019 ranked as the second-best English-speaking country in the world among those which do not have English as their first language (Education First). Nonetheless, Swedish teachers encounter students who lack the motivation to learn. Of course, different school subjects are appealing to different people, but for teachers of English it is essential to be aware of what they can do, or avoid doing, in order to induce motivation to learn an additional language.

One challenge teachers face is to come up with inspiring activities to enhance pupils’ learning abilities. Jafre Zainol Abidin et al. (2012) argue that “EFL teachers should respect and think about students’ feelings, beliefs and behaviors before the cognitive abilities. English curriculum and classroom activities should involve affective aims according to the students’ needs and their individual differences to build up positive attitudes towards English” (p. 126). They conclude that attitude is an essential component in language learning and that a positive attitude should permeate the educational mindset. They also argue for the importance of studying learners’ personalities and they proclaim that “cognitive performance can be achieved if the EFL learners possess positive attitudes and enjoy acquiring the target language” (Jafre Zainol Abidin et al., 2012, p. 126). Therefore, to learn how to stimulate students to achieve these positive attitudes is an important aspect of teaching.

In this study, students will answer a questionnaire in order to find out which educational activities students in Swedish lower secondary schools, ages 13 to 15, become motivated and unmotivated by in the process of learning English. Furthermore, the background section will present material relevant to the study in terms of previous research and reports on ESL learning and motivation.

2

2 Background

When learning or teaching additional languages one is likely to encounter the terms second language (SL), and foreign language (FL). The difference between them is the setting in which the target language is learnt. If someone learns a SL, it is learnt in a setting where the target language is spoken in the surrounding community. Moreover, if someone learns a FL, it means that the target language is learnt in a setting where it is generally not spoken in the surrounding community (Yule, 2014, p. 187). However, “[i]n either case, they are simply trying to learn another language, so the expression second language learning is used more generally to describe both situations” (Yule, 2014, p. 187). Therefore, and because of the wide usage of and exposure to English in the Swedish community, English will in this study be considered a SL (i.e. ESL) and not a FL. In the following sub-sections, thoughts on motivation, attitudes, and different educational activities are addressed.

2.1 Motivation for and Attitudes towards Second Language Learning

Motivation can for example be enhanced by a certain activity, a proficiency outcome, or a sense of self-fulfillment. For teachers it is not only necessary to have enough knowledge about the subject they are teaching, but also to have the ability to enhance students’ attitudes towards that subject. As argued by Candlin and Mercer (2001), attitudes towards a language, its speakers and its learning contexts are major factors in language learning and may play important roles when explaining success or failure.

In a study by Al-Zahrani (2008) it is suggested that a reason for negative attitudes towards English language learning could be a reaction to some of the English language teachers’ instructional and traditional methods of teaching. This suggestion goes with the one of Ghazali et al. (2009) that “[u]sing a variety of attractive teaching strategies is another way to improve students’ attitudes” (p. 55). Thus, these suggestions indicate that there is a relevance of exposing students to attractive and varying methods of teaching and that students do not become motivated to learn when teachers resort to traditional methods of teaching.

Traditional methods can be described as such which focus on learning through fact-oriented and non-interactive activities, for example memorization and recitation techniques, and when teachers assess students’ learning through separate events. On the contrary, teachers who resort to constructivist methods of teaching structure their lessons around big ideas and not small pieces of information, they make activities student-centered and interactive, and they assess students’ learning in the context of daily classroom investigations (Brooks & Brooks, 1999;

3

Gray, 1997). Furthermore, Sternberg and Williams (2002) mean that constructivist methods of teaching allow learners to build their own knowledge, which often results in deeper learning and enhanced memory.

In a report carried out by the Swedish Schools Inspectorate (2011), it is claimed that many students make distinctions between English inside school and English outside school and that students in general feel less confident when they use English inside school compared to when they use English outside school (p. 8). The report also suggests that students believe they acquire approximately half of their knowledge in English from outside school.

Lightbown and Spada (2013) argue that if learners understand the communicative value of a second language (SL) it is also possible that they will be motivated to become proficient in it. This could happen when a learner needs to speak the SL in extensive social situations or in order to accomplish professional ambitions (p. 87). Lightbown and Spada (2013) also argue that if a learner has a positive attitude towards a speaker of a language, it is more likely that motivation to communicate with that person is increased (p. 87).

2.2 Educational Approaches in Second Language Education

Creative ideas for how to conduct language teaching are essential to induce students’ motivation to learn English. In this section, several approaches to English language education are addressed based on their presence in previous research and national steering documents.

Social interaction goes hand in hand with language and there are many different social activities that could be implemented in language learning. Garret-Rucks (2015) suggests that sociocultural components work to enhance communicative competence and to help people communicate more effectively (p. 40). Seminars and group discussions could be such activities. However, this method of learning does not only occur in the physical presence of people, it could also occur online, through chatting or gaming.

An established method for language teaching and learning is to get engaged in visual or audible media, such as watching films and TV programs, and listening to music and radio shows. These methods are commonly encountered by a learner both inside and outside school and they may be implemented by a teacher in the education in order to practice proficiency and teach new vocabulary, for example through translating a song. According to Alharbi (2015), one variable for listening and pronunciation strategies is to listen to authentic conversations and media to learn pronunciation of new words. Moreover, to get engaged in visual or audible media is not

4

only relevant for learning new vocabulary, but it could also be relevant for learning about other cultures.

Software programs and computer games can assist language learning in several ways and the interest of using computers in this area has increased significantly due to our globalized society and the development of technology (Borges, 2014, p. 20). These programs can work as providers of material, assessors of completed tasks, and providers of suitable learning contexts. An example of this would be enabling a context of social interaction online.

There are computer games which provide players with instructions in other languages and interaction with other people and it demands a certain level of proficiency in the target language to be engaged successfully. Furthermore, Gee and Hayes (2011) claim that once a player has developed a passion for a specific game, it will promote engaging with other players, analyzing, discussing, criticizing, and reflecting. Some of these are desirable components for improving proficiency in a SL (National Agency for Education, 2011).

Brown (2014) and Garrett-Rucks (2015) emphasize that learning a second culture is a part of learning a SL. Globalization is developing fast and there is an interdependence of many different components in the society all over the world in order to match peoples’ and nations’ interests. Many higher education instances are pushed to be more internationalized to produce more “globally competent citizens”, which includes the abilities to “recognize global interdependence, be capable of working in various environments, and accept responsibility for world citizenship” (Spaulding et al., 2010, p. 190). These abilities promote an increased level of intercultural competence among people, both in terms of second language learning and capability of adapting to the society.

Intercultural competence is also emphasized in the Swedish curriculum for English, where it, under the content of communication, says that teachers should cover “[l]iving conditions, traditions, social relations and cultural phenomena in various contexts and areas where English is used” (National Agency for Education, 2011, p. 36). Furthermore, Garrett-Rucks (2015) suggests that this activity could be implemented in SL education through looking at cultures’ values, rituals and traditions (conventionalized behavior patterns), heroes (highly prized people), and symbols (flags, traditional clothing).

Letting students take part in drama or role-playing is another method which has been proven to be effective for language learning. According to Ustuk and Inan (2017) teachers can use this method “to sustain a constructivist learning environment, to influence the sense of cultural

5

awareness, to have an impact on L2 performance, and finally to create an affective learning space” (p. 37). They also argue that drama in education (DIE) can “give the learners an opportunity to obtain intercultural experiences in which L2 learners may not only grasp the English language as it is used by the native speakers, but the English language that is used in real life” (Ustuk & Inan, 2017, p. 37). A learner will then not only acquire skills in the English language but also knowledge about how cultures in English speaking countries relate to others. This suggests that drama and role-playing can intertwine with other activities and methods in language learning, such as social interaction and learning about culture. In addition, Ustuk and Inan (2017) suggest that more improved performances in additional languages can be expected to occur among students if more DIE is implemented in English language education.

3 Aim and Research Questions

The aim of this study is to find out how different educational activities affect students’ motivation for English as a second language (ESL) learning in Swedish lower secondary schools, in order to give teachers an idea of which activities to include if they wish to induce students’ motivation. The research questions are:

1. Which educational activities induce student motivation to ESL learning? 2. Which educational activities deduce student motivation to ESL learning?

3. Based on the results of the study, how can teachers induce students’ motivation?

4 Method and Material

The study was conducted through a questionnaire directed towards students, ages 13 to 15, at three lower secondary schools from the same municipality in southern Sweden. The reason for the choice of schools was the intention to reach students with a wide variety of demographic profiles. The schools were one with a dual language education program, one located in an area with a high degree of cultural variation, and one located in an area with a low degree of cultural variation.

A school with a dual language education program provides literacy and content area instruction to all students through two languages in order to maintain both languages over the long term (Hinkel, 2014, pp. 3-8). This ought to indicate differences between these students’ competence in English compared to students at schools without dual language education programs. However, Gardner and Lambert (1972) conclude that not only language skills or mental competence influence students’ abilities to master a second language (SL), but also students’

6

attitudes and perceptions towards the target language. Thus, results in this study could provide data about students’ motivation related to the educational profile of a school.

The statistics shown in the results section are representative for the 266 students who answered the questionnaire. They were 95 from the school with a dual language education program, 109 from the school located in an area with a high degree of cultural variation, and 62 from the school located in an area with a low degree of cultural variation. The statistics are shown in percentage and indicate how many of the participants find a certain educational activity motivating, non-motivating, or to not have any impact on their motivation. The complete tables for each school as well as the total are presented in the appendix section.

In the analysis and discussion section, comparable analyses are made for the schools in relation to each other but not for each school in relation to the overall result, since there is a significant difference in number of participants from each school. The overall result could be relevant to get a general overview of students’ attitudes, however, if one would compare each school with the overall result, it would give misleading information since the school with the most participants would be representing the largest part of the result. Moreover, the fact that one person is worth more than one per cent, in the cases when analyzing the results from the two schools with less than 100 participants independently, is a limitation in the study.

4.1 Questionnaire

The outline of the questionnaire was based on previous research about educational activities in English as a second language (ESL) teaching and learning and attitudes towards it, for example Bursali and Öz (2017). In the questionnaire, there were 36 activities listed which students should answer whether they become motivated or unmotivated by, or if the activities do not have any impact on their motivation to learn English. English language learning is often divided into four language skills (listening, reading, speaking, and writing) and the Swedish National Agency for Education structures these skills into two categories: reception and production and

interaction (National Agency for Education, 2011). The questionnaire was created so the

activities in the questionnaire covered every skill.

When targeting different activities in school that affect motivation, it is relevant to keep in mind that there might be aspects of certain activities that are more or less motivating. Just because someone is motivated by reading instructions for a game does not mean that the same person is motivated by reading a novel. Ghazali et al. (2009) claim that there is a difference in attitudes towards reading depending on what types of texts that are read. They suggest that “[a]

7

way to motivate students to read literature is through better text selection” and that “[t]he most important criterion in text selection is probably students’ interest” (p. 55). Furthermore, this position is shared by Bursali and Öz (2017) who list 27 educational activities and respondents’ attitudes towards these. Their results show that students are more willing to communicate inside the classroom if one should read a letter from a pen pal in English than if one should read an article in a paper (Bursali & Öz, 2017, p. 234). Therefore, it is wrong to generalize that a person does or does not like reading, or any other language skill, just because the person has a certain attitude towards one aspect of it.

The questionnaire was distributed to the students online by their English language teachers and the reason for collecting data through a questionnaire was the advantage this has of providing high quantities of data (Clarke, 2011, p. 6). This method of collecting data is obviously dependent on that all the intended participants have access to internet, an assumption which could be taken for granted due to the wide technological usage among Swedish teenagers. The questionnaire was written in Swedish in order to minimize the risk of students not understanding, which could be the case if the questionnaire should have been written in English and students with moderate or low knowledge in English should participate. The activities listed in the tables in this study are translated from how they were written in the questionnaire to English.

4.2 Ethical Principles

Throughout a research process, ethical thinking and practice should be considered, especially when including people. Reducing risk of harm, protecting privacy, and respecting autonomy are examples of principles, or considerations, which a researcher should always pay special attention to (Coe et al., 2017, p. 59). The Swedish Research Council lists four main demands for conducting a study with people; giving the participants adequate information about the study, getting the participants’ consent and clarifying their right to withdraw themselves if they do not wish to participate, confidentiality and anonymity of the participants, and using gathered information only for the purpose of the current study (Vetenskapsrådet, 2002).

In this study, the participants were informed about their anonymity and their right to withdraw themselves in the beginning of the questionnaire. Adequate information about the study may for example be how the study will be used and reported, its importance, benefits or potential harm. Benefits of the study were also presented in the beginning of the questionnaire and the participants were encouraged to give honest answers, since the results could help teachers to

8

structure lessons for the good of the students. There is a risk of appropriation where participants answer in a way they believe is favorable, however, due to the structure and theme of this questionnaire there is no reason to believe that was the case. Moreover, some information can be left out in a study, if giving that information would mean jeopardizing the validity or reliability of the research, however, respect for the participants’ privacy concerning confidentiality and anonymity must still be taken into consideration (Coe et al., 2017, p. 38).

According to the Swedish Research Council, parents’ or guardians’ consent should be given if the participants are under the age of 15 and if the study is considered to be of ethical sensitive character (Vetenskapsrådet, 2002, p. 9). Except that some participants are under the age of 15, the study is not considered to be of ethical sensitive character, thus, parents’ or guardians’ consent is not necessary.

5 Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework chosen for this study is sociocultural theory because it correlates both to the English subject as well as to an existing educational approach found in the Swedish educational system. As explained by Swain et al. (2015), sociocultural theory was introduced by the Russian thinker Lev Vygotsky and was spread to the West during the 1960s (p. ix). Due to this spread, the theory has become a great influence on Western education (Gibbons, 2015, p. 13). The theory is based on the idea of development through interaction and social meetings and since language is dependent on interaction and social meetings, sociocultural theory is an appropriate theory to apply when analyzing the results.

5.1 Sociocultural Theory in Second Language Education

Sociocultural theory is a wide perspective in the aspect of learning theories and possesses several concepts, some of which will be specified below. Language is complex and Gee and Hayes (2011) argue that it can be expressed in different forms, a set of rules, physically present phenomena in the forms of speech, audio recordings, and writings, or even a set of social conventions shared by a group of people (p. 6). In the community, the sociocultural learning process is not only present in the education system. It is constantly present in a person’s everyday life, while working, reading news, meeting friends, shopping, visiting libraries and museums, or consuming entertainment. Lantolf (2000) argues that “Vygotsky’s theory of learning and development implies that learning is also a form of language socialization between individuals and not merely information processing carried out solo by an individual” (p. 33).

9

Advocators of this theory, as Lantolf, emphasize the phase of development through interaction with other people or experiences within social contexts and the surrounding environment.

5.1.1 Zone of Proximal Development

A popular term which many educators most likely have come across when talking about sociocultural theory is the zone of proximal development (ZPD). This is “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 86). In other words, when learners reach their ZPD they need assistance to develop further, something which can be gained through guidance by someone with better abilities. Seminars, where learners are able to exchange and challenge thoughts and ideas, both with their peers and teachers, are examples of settings where they can be assisted to go beyond their current knowledge level.

5.1.2 Scaffolding

Scaffolding is a concept which means that a learner is given fragments of assistance in order to

move from one success to another. Wells (1999) defines this concept as a way of operationalizing the process of working in the zone of proximal development (p.127). Scaffolding can both occur between teacher-pupil as well as between pupil-pupil and Swain et al. (2015) state that it occurs when “assistance is given when needed and in the quantity and quality needed, and is then gradually dismantled when the structure/individual can mediate (regulate) itself” (p. 26). This is a method of providing knowledge or tools in a necessary amount for a learner to continue her or his educational journey.

5.1.3 Community of Practice

Community of practice (COP) is related to the social aspects of the learning process and is

intentionally straying from the school-centered discussions. It rather focuses on the social practice within a community or in collectives of people (Freeman, 2016, p. 235). Swain et al. (2015) argue that COP “sees learning as participation in the cultural, historical, political life of the community” (p. 27). Examples of this could be when engaging in policies, practices, norms, and rules used in a specific social setting. In practical language education, this can be exercised when learning about culture, which according to Brown (2014) and Garrett-Rucks (2016) is a part of second language learning.

10

6 Results

Before the participants answered how different activities affect their motivation to learn English, they had to answer in which situations they become motivated. The question was constructed so they could choose between multiple preset answers or choose “other”.

Table 1. Indications of in which situations students become motivated

When do you become motivated?

When I think something is fun 77,82% When I think something is important 43,23% When I succeed doing something difficult 34,59% When I think something is challenging 21,80% When I think something is valuable 16,17%

Other 6,02%

A vast majority, 77,82% of the participants, answered that they become motivated when they think something is fun. The second most frequent answer was that they become motivated when they think something is important.

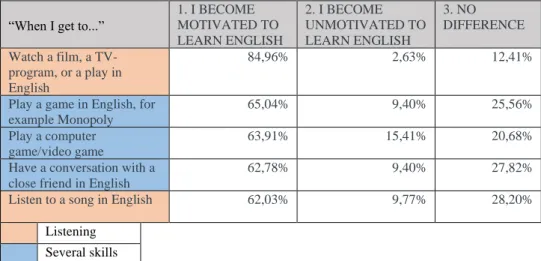

The complete statistics for the three participating schools are shown in the appendix, in Table 10. Below, in Table 2, statistics for the five activities that most students overall become motivated by are listed. The colors indicate which language skill a certain activity is focused on.

Table 2. The five most motivating activities among students overall

“When I get to...”

1. I BECOME MOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 2. I BECOME UNMOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 3. NO DIFFERENCE Watch a film, a TV-program, or a play in English 84,96% 2,63% 12,41%

Play a game in English, for example Monopoly

65,04% 9,40% 25,56%

Play a computer game/video game

63,91% 15,41% 20,68%

Have a conversation with a close friend in English

62,78% 9,40% 27,82%

Listen to a song in English 62,03% 9,77% 28,20%

Listening Several skills

As shown in Table 2, to “watch a film, a TV-program, or a play in English” is listed as the activity that most students are motivated by with a ratio of 84,96%. For this activity, only

11

2,63% answered that they become unmotivated and 12,41% answered that the activity does not have any impact on their motivation to learn English.

In addition, Table 2 shows that there is a large variance in number between the students who become motivated by these activities and the ones who become unmotivated and who think that an activity does not have any impact on their motivation. The smallest variance between the answers applies to the activity to “listen to a song in English” where 62,03% answered that they become motivated and 28,20% answered that they become unmotivated, which is a variance of 33,83%. This means that students to a relatively high degree agree on what they find motivating among the top five motivating activities. Notable in this table is that among the activities that most students become motivated by, the activity to “play a computer game/video game”, which has the third highest score, has the highest number of students who become unmotivated.

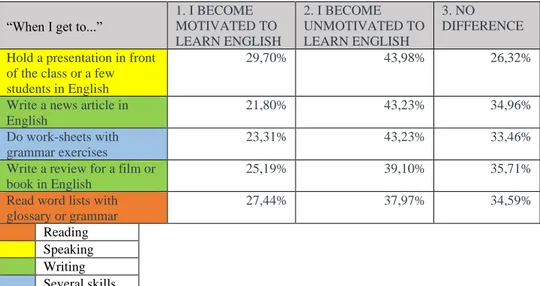

Below are the five activities listed which most students become unmotivated by.

Table 3. The five most non-motivating activities among students overall

“When I get to...”

1. I BECOME MOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 2. I BECOME UNMOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 3. NO DIFFERENCE Hold a presentation in front

of the class or a few students in English

29,70% 43,98% 26,32%

Write a news article in English

21,80% 43,23% 34,96%

Do work-sheets with grammar exercises

23,31% 43,23% 33,46%

Write a review for a film or book in English

25,19% 39,10% 35,71%

Read word lists with glossary or grammar 27,44% 37,97% 34,59% Reading Speaking Writing Several skills

The activity that most students become unmotivated by is to “hold a presentation in front of the class or a few students in English”, which 43,98% of the students implied that they became unmotivated by. Compared to Table 2, there is much more diversity in opinions regarding what students become unmotivated by. The largest variance in this table applies to the activity to “write a news article in English”, where 43,23% answered that they become unmotivated and 21,80% answered that they become motivated. This makes a variance of 21,43%, in contrast to Table 2, where the smallest difference is 33,83%.

12

6.1 The Most Motivating Activities: School A, School B, School C

The intention to reach students with a wide variety of demographic profiles was the reason for the choice of schools for this study and results from each school are presented in the sub-sections below. School A indicates the school with a dual language education program, School B indicates the school located in an area with a high degree of cultural variation, and School C indicates the school located in an area with a low degree of cultural variation. Table 4, 5, and 6 present the five activities which most students at each school become motivated by.

Table 4. The five most motivating activities among students at School A

“When I get to...”

1. I BECOME MOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 2. I BECOME UNMOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 3. NO DIFFERENCE Watch a film, a TV-program, or a play in English 80,00% 1,05% 18,95%

Listen to a song in English 64,21% 4,21% 31,58% Have a conversation with

an English-speaking person

63,16% 7,37% 29,47%

Chat with an English-speaking person online

61,05% 8,42% 30,53% Speak to my teacher in English 61,05% 8,42% 30,53% Listening Speaking Several skills

Table 4 shows that by the top five motivating activities there are very few students who become unmotivated. At the most, not even one out of ten students becomes unmotivated by any of these activities (8,42%) and by the activity to “watch a film, a TV-program, or a play in English” there is approximately one out of 100 students who becomes unmotivated (1,05%). A difference compared to School B and C is that an activity which focuses on speaking is present among the top five motivating activities, to “speak to my teacher in English”.

The next table, Table 5, presents the five activities which most students at the school located in an area with a high degree of cultural variation become motivated by.

13

Table 5. The five most motivating activities among students at School B

“When I get to...”

1. I BECOME MOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 2. I BECOME UNMOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 3. NO DIFFERENCE Watch a film, a TV-program, or a play in English 84,40% 3,67% 11,93% Play a computer game/video game 72,48% 11,01% 16,51%

Have a conversation with a close friend in English

67,89% 11,01% 21,10%

Play a game in English, for example Monopoly

65,14% 11,01% 23,85%

Listen to a song in English 61,47% 11,01% 27,52%

Listening Several skills

To “watch a film, a TV-program, or a play in English” remains as the activity that most students at School B become motivated by, with a ratio of 84,40%. Number two in this table is to “play a computer game/video game”, with a ratio of 72,48%. Compared to the results of the top five motivating activities among students at School A and C, the activity to “play a computer game/video game” is present, whereas to “chat with an English-speaking person online” is not. However, there is a similarity between these two activities and that is the use of technological devices.

Table 6 presents the five activities which most students at the school located in an area with a lower degree of cultural variation become motivated by.

Table 6. The five most motivating activities among students at School C

“When I get to...”

1. I BECOME MOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 2. I BECOME UNMOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 3. NO DIFFERENCE Watch a film, a TV-program, or a play in English 93,55% 3,23% 3,23%

Play a game in English, for example Monopoly

74,19% 9,68% 16,13%

Have a conversation with a close friend in English

69,35% 14,52% 16,13%

Chat with an English-speaking person online

61,29% 22,58% 16,13%

Listen to a song in English 59,68% 16,13% 24,19%

Listening Several skills

The activity to “watch a film, a TV-show, or a play in English” is the top motivating activity at all schools in the study. Notable is that the ratio for this activity at School C (93,55%) is higher compared to School A (80,00%) and School B (84,40%), which means that there is a

14

higher ratio of students at the school located in an area with a lower degree of cultural variation who become motivated by this activity. Furthermore, results in Table 6 indicate that the ratio of students who become motivated by interacting with an English-speaking person is higher at School C than at School B.

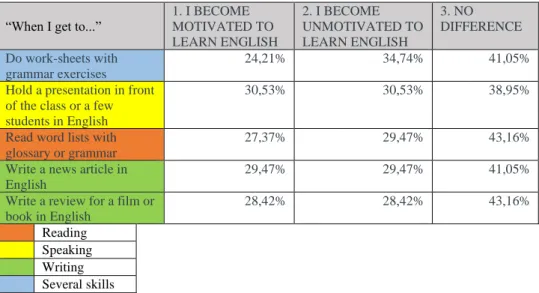

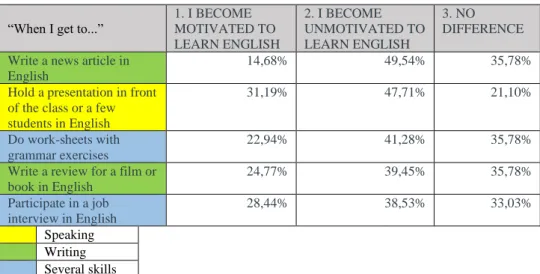

6.2 The Most Non-Motivating Activities: School A, School B, School C

The next three tables, Table 7, 8, and 9, present the five activities which most students at each school become unmotivated by. School A indicates the school with a dual language education program, School B indicates the school located in an area with a high degree of cultural variation, and School C indicates the school located in an area with a low degree of cultural variation.

Table 7. The five most non-motivating activities among students at School A

“When I get to...”

1. I BECOME MOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 2. I BECOME UNMOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 3. NO DIFFERENCE Do work-sheets with grammar exercises 24,21% 34,74% 41,05%

Hold a presentation in front of the class or a few students in English

30,53% 30,53% 38,95%

Read word lists with glossary or grammar

27,37% 29,47% 43,16%

Write a news article in English

29,47% 29,47% 41,05%

Write a review for a film or book in English 28,42% 28,42% 43,16% Reading Speaking Writing Several skills

For the top five activities that most students find non-motivating at School A, indications are given that for three out of five activities there are just as many students who become motivated and unmotivated; to “hold a presentation in front of the class or a few students in English” (30,53%), to “write a news article in English” (29,47%), and to “write a review for a film or book in English” (28,42%). Notable is also that for every activity there are more students who answered that the activity does not have any impact on their motivation. These results indicate that there is, at the most, approximately one out of three students (34,74%) at the school with a dual language education program who becomes unmotivated by a certain activity, which is less than at the other participating schools.

15

Table 8. The five most non-motivating activities among students at School B

“When I get to...”

1. I BECOME MOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 2. I BECOME UNMOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 3. NO DIFFERENCE Write a news article in

English

14,68% 49,54% 35,78%

Hold a presentation in front of the class or a few students in English

31,19% 47,71% 21,10%

Do work-sheets with grammar exercises

22,94% 41,28% 35,78%

Write a review for a film or book in English 24,77% 39,45% 35,78% Participate in a job interview in English 28,44% 38,53% 33,03% Speaking Writing Several skills

At School B, there is less variance among students about what they become unmotivated by, compared to students at School A. At School A (Table 7), the activity which most students become unmotivated by, to “do work-sheets with grammar exercises”, shows a ratio of 34,74% (almost one out of three students), while the number one non-motivating activity in Table 8, to “write a news article in English”, has a ratio of 49,54% (almost one out of two students). Both these activities are, however, listed on each school’s table of the top 5 non-motivating activities.

Table 9. The five most non-motivating activities among students at School C

“When I get to...”

1. I BECOME MOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 2. I BECOME UNMOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 3. NO DIFFERENCE Do work-sheets with grammar exercises 22,58% 59,68% 17,74%

Read word lists with glossary or grammar

17,74% 58,06% 24,19%

Hold a presentation in front of the class or a few students in English

25,81% 58,06% 16,13%

Write a review for a film or book in English

20,97% 54,84% 24,19%

Write a news article in English 22,58% 53,23% 24,19% Reading Speaking Writing Several skills

As for School A and B, Table 9 shows that there is no activity with focus on listening present among the top five non-motivating activities for students at the school located in an area with a lower degree of cultural variation. The number one and number five non-motivating activities among students at School A has a ratio of 34,74% and 28,42% respectively, and a ratio of 49,54% and 38,53% among students at School B. At School C, the number one and number

16

five non-motivating activities has a ratio of 59,68% and 53,23% respectively. There were also few students at School C who indicated that the activities have no impact on their motivation, compared to students at School A and B.

7 Analysis and Discussion

There are similarities between the overall results of the most motivating activities in this study and in the one by Bursali and Öz (2017). In their list of the top five motivating activities, “understanding an English movie” and “talking to a friend while waiting in line” were present (p. 234). These are similar to the activities to “watch a film, a TV-program, or a play in English” and to “have a conversation with a close friend in English” which are listed among the top five motivating activities in Table 2.

The results of this study also indicate that there tend to be much more similar answers for the activities which most students become motivated by than for the activities which most students become unmotivated by. For the activities which most students find motivating, there are few students who have answered that they find these activities non-motivating or to not have any impact on their motivation. However, for the activities which most students find non-motivating, there is also a high number of students who have answered that they either find them motivating or to not have any impact on their motivation.

Furthermore, the activities listed as the most motivating ones are also such which are likely to appear outside school, such as watching a film, playing Monopoly, playing computer games or video games, having a conversation with a close friend, and listening to a song. As claimed by the Swedish Schools Inspectorate (2011), many students feel less confident when they use English inside school compared to when they use English outside school, and this could be a reason for the results of the questionnaire. From a sociocultural perspective, this aspect could be linked to the community of practice (COP) as explained by Freeman (2016), where one is intentionally straying from the school-centered discussions and instead focusing on the social practice within a community or in collectives of people (p. 235).

In contrast, the most frequently listed activities which most students become unmotivated by (Table 7, 8, and 9) are such which could be more difficult to link to the COP. These activities are “do work-sheets with grammar exercises”, “hold a presentation in front of the class or a few students in English”, “write a news article in English”, and “write a review for a film or book in English”, and they are present in both Table 7, 8, and 9. To write a news article is also

17

listed as one of the five least motivating activities in Bursali and Öz’s study (2017, p. 234). However, the results of this study do not imply that these activities either induce or deduce motivation exclusively. There are still students who think the opposite of the largest number implied in the tables.

To “have a conversation in English” is listed in all tables which indicate the top five motivating activities at each school. Furthermore, while more students at the school with a dual language education program become motivated by having a conversation with an English-speaking person and by speaking to their teacher in English, there are more students at School B and C who become motivated by having a conversation with a close friend in English. These results could indicate that students at the school with a dual language education program are more motivated by interacting with someone who is expected to have higher proficiency in English than them, compared to students at School B and C. When analyzing this through a sociocultural perspective, it resembles the claim that the developmental level is determined “through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 86). These results show that students at School A have positive attitudes towards educational activities in English language learning that are more favorable of acquiring high proficiency, compared to students at School B and C.

Another notable aspect is that in the tables which show the activities that most students become motivated by, there are only activities present which focus on the skill of listening or on several language skills, except the activity to “speak to my teacher in English” which is listed once. In contrast, the activities in the tables which show the ones that most students become unmotivated by focus on all skills (reading, writing, speaking, and several language skills) except listening.

There are differences between the schools in level of agreement regarding which activities the students become unmotivated by. For every activity among the top five non-motivating ones at School A (Table 7), there are more students who answered that those activities have no impact on their motivation. However, at School B and C (Table 8 and 9), the ratio of the students who become unmotivated by an activity is always the highest.

These results indicate that more students at the schools without a dual language education program think more similar regarding which activities they find non-motivating than students at the school with a dual language education program. Due to statistics shown in Table 7, 8, and 9 one could also claim that there are few students at School A who tend to find educational

18

activities for learning English non-motivating. However, this does not mean that these students find every other activity motivating, since there is still a higher number of students who have answered that the activities do not have any impact on their motivation.

To “hold a presentation in front of the class or a few students in English”, “do work-sheets with grammar exercises”, and “read word lists with glossary or grammar” are fact-oriented and non-interactive activities which focus on memorizing knowledge. Therefore, these could count as traditional ways to learn English. In contrast, activities which most students in the study become motivated by, such as chatting online, having a conversation with a close friend, or playing Monopoly or a computer game, could be seen as more modern methods to learn English due to the level of interaction these activities require and due to the increased interest in computers in the area of language teaching and learning (Borges, 2014, p. 20). The results shown in the tables which present the activities which most students become unmotivated by go with the claim of Sternberg and Williams (2002), that students are not motivated to learn when teachers resort to traditional methods of teaching.

8 Conclusion

In summary, the results indicate that there are both similarities and variances in opinions among students between different schools regarding what they become motivated and unmotivated by. For the first question, which educational activities induce students’ motivation to ESL learning, the results indicate that most students become motivated by activities where either technological devices are used, such as watching a film, chatting online, or playing computer or video games, or by activities which students are likely to come across outside school, such as playing Monopoly or listening to songs. Safety and comfort were also elements found in the activities which most students become motivated by, such as having a conversation with a close friend or their teacher. Variance could be found between School A and the other schools. Indications given were that students at the school with a dual language education program tend to become more motivated by activities where they can interact with people who are expected to have higher proficiency in English than them.

For the second question, which educational activities deduce students’ motivation to ESL learning, results indicate that there are many similarities between the schools. The activities to “hold a presentation in front of the class or a few students in English”, “do work-sheets with grammar exercises”, “read word lists with glossary or grammar”, “write a news article in

19

English”, and “write a review for a film or book in English” were almost exclusively present among the top five non-motivating activities. To “participate in a job interview in English” was present once. These activities seem to be correlated to tasks that are either likely to be encountered inside school or later in their adult life for work, such as writing a news article or participating in a job interview. The largest difference between the schools was the variation in answers in relation to each other. The students at the school with a dual language education program agreed to a much lower degree on what they find non-motivating compared to the students at the other schools.

The last question, how teachers can increase students’ motivation to learn English, requires a complex answer. The results do not imply that a teacher should eliminate an activity completely from its repertoire, since the results show that students find all the activities in the questionnaire motivating. Also, when looking at the activities which most students become unmotivated by, the ratio for students who become motivated or do not find an activity to have an impact on their motivation is still high. However, in order to increase the overall motivation in a class, teachers could increase the use of activities which few students become unmotivated by and limit the use of the ones which many students become unmotivated by. How this can be implemented by teachers depends on the attitudes of the students in each teacher’s classroom.

If a teacher’s main focus is to expose students to and practice certain activities regardless of their level of motivation, the results of this study are probably not as relevant as if students’ motivation would be the teachers’ main focus. Moreover, if teachers’ main focus is to expose students to certain activities in order for them to learn how to become motivated by them, these results can also be of use. At the same time as studies suggest that motivation is strongly correlated with good results in second language proficiency, teachers are, according to the National Agency for Education (2011), obligated to teach students and expose them to certain aspects of English language learning. It is difficult to find activities which all students become motivated by. However, in the tables presented in the appendix section, results show that most students at every school become motivated by more than half of the activities listed. This indicates that Swedish lower secondary school students overall have positive attitudes towards English language learning activities.

There are always some risks with quantitative studies and generalizing, since the most concern is given to the largest quantity of the aspect in focus. They can be convenient for giving an

20

overview, but it is important that teachers pay special attention to what each of their students become motivated and unmotivated by in order to induce the students’ motivation to learn.

Finally, this study contributes to the field of research by presenting an overview of how certain educational activities affect students’ motivation in Swedish lower secondary schools. In addition, the study also presents information about how attitudes may vary between different schools. In order to receive even more accurate statistics and make each school’s result comparable to the overall result, more students could be included in the study as well as the same number of participants from each school. For further studies in this area, teachers' views on motivation and to what extent they take that into consideration when teaching ESL could be investigated.

21

9 References

Alharbi, A. M. (2015). Building vocabulary for language learning: Approach for ESL learners to study new vocabulary. Journal of International Students, 5(4), 501-511. Retrieved from

http://proxy.library.ju.se/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.proxy.library.ju.se/docview/1695740301?accountid=11754

Al-Zahrani, M. (2008). Saudi secondary school male students’ attitudes towards English: An exploratory study. J. King Saudi University, Language and translation, 20, 25-39.

Borges, V. M. C. (2014). Are ESL/EFL software programs effective for language learning?

Ilha do desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies, 0.66, 019-074. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.5007/2175-8026.2014n66p19

Brooks, M. G., & Brooks, J. G. (1999). The courage to be constructivist. Educational

Leadership: The Constructivist Classroom, 57(3), 18-24.

Brown, H.D. (2014). Principles of language learning and teaching (6th ed.). White Plains, NY: Pearson Education.

Bursali, N., & Öz, H. (2017). The relationship between ideal L2 self and willingness to communicate inside the classroom. International Journal of Higher Education, 6(4), 229-239. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1153207.pdf

Candlin, C., & Mercer, N. (2001). English language teaching in its social context. New York, NY: Routledge.

Clarke, A. (1999). Evaluation research. London, England: SAGE. Publications Ltd, doi: 10.4135/9781849209113

Coe, R., Waring, M., Hedges, L.V., & Arthur, J. (2017). Research methods & methodologies

in education (2nd ed.). London, England: Sage Publications.

Education First. (n.d.). EF English Proficiency Index (9th ed.). Retrieved from https://www.ef.se/epi/

Freeman, D. (2016). Educating second language teachers. Oxford, England: University Press.

Gardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. (1972). Attitudes and motivation in second language

22

Garret-Rucks, P. (2016). Intercultural competence in instructed language learning: Bridging

theory and practice. (Contemporary Language Education Series). Charlotte, NC:

Information Age Publishing.

Gee, J. P., & Hayes, E. R. (2011). Language and learning in the digital age. New York, NY: Routledge.

Ghazali, S., Setia, R., Muthusamy, C., & Jusoff, K. (2009). ESL students’ attitude towards texts and teaching methods used in literature classes. English language teaching, 2(4), 51-56. Retrieved from http://www.ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/elt/article/view/4445

Gibbons, P. (2015). Scaffolding language, scaffolding learning: Teaching English language

learners in the mainstream classroom (2nd ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Gray, A. (1997). Constructivist teaching and learning. SSTA Research Centre Report, 97-07.

Hinkel, E. (Ed.). (2011). Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning:

Volume II. (ESL & Applied Linguistics Professional Series). New York, NY:

Routledge.

Jafre Zainol Abidin, M., Pour-Mohammadi, M., & Alzwani, H. (2012). EFL students’ attitudes towards learning English language: The case of Libyan secondary school students. Asian Social Science, 8(2), 119-134. Retrieved from

http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v8n2p119

Lantolf, J. P. (2000). Sociocultural theory and second language learning. Oxford, England: University Press.

Lightbown, P. M., & Spada, N. (2013). How languages are learned. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Lindberg, J. (2019). Educational approaches & strategies for ESL teaching in Swedish compulsory schools (Bachelor’s theses, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden). Retrieved from

http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1295585/FULLTEXT02.pdf

National Agency for Education. (2011). Curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool

class and school-age educare. Retrieved from

https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.31c292d516e7445866a218f/1576654682907/p df3984.pdf

23

Schools Inspectorate. (2011). Engelska i grundskolans årskurser 6–9. Retrieved from https://www.skolinspektionen.se/globalassets/publikationssok/granskningsrapporter/kv alitetsgranskningar/2011/engelska-2/slutrapport-engelska-grundskolan-6-9.pdf

Spaulding, S., Mauch, J., & Lin, L. (2001). The internationalization of higher education: Policy and program issues. In O'Meara, P., Mehlinger, H. D., & Newman, R. M. (Eds.)

Changing perspectives on international education (pp. 190-212). Bloomington, IN:

Indiana University Press.

Sternberg, R. J., & Williams, W. M. (2002). Educational psychology. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Swain, M., Kinnear, P., & Steinman, L. (2015). Sociocultural theory in second language

education: An introduction through narratives (2nd ed.). Bristol, England: Multilingual

Matters.

Ustuk, Ö., & Inan, D. (2017). A comparative literature review of the studies on drama in English language teaching in Turkey. Novitas-ROYAL (Research on Youth and

Language), 11(1), 27-41. Retrieved from

https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1167241.pdf

Vetenskapsrådet (2002). Forskningsetiska principer inom humanistisk-samhällsvetenskaplig

forskning. Retrieved from http://www.codex.vr.se/texts/HSFR.pdf

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wells, G. (1999). Dialogic inquiry: Towards a sociocultural practice and theory of

education. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Yule, G. (2014). The study of language (5th ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

24

10 Appendix

10.1 Questionnaire Results (Total)

Table 10. Indications of how students think certain educational activities affect their motivation

“When I get to...”

1. I BECOME MOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 2. I BECOME UNMOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 3. NO DIFFERENCE Listen to instructions to a task in English 33,08% 22,18% 44,74% Listen to a presentation in English 38,72% 18,80% 42,48%

Listen to and watch the news in English

42,48% 21,05% 36,47%

Listen to a podcast or a radio program in English

41,35% 20,30% 38,35%

Listen to a song in English 62,03% 9,77% 28,20%

Watch a film, a TV-program, or a play in English

84,96% 2,63% 12,41%

Read an email/letter from an English-speaking person

43,61% 18,42% 37,97%

Read a book in English 42,86% 28,57% 28,57%

Read a news article in English

25,94% 28,95% 45,11%

Read a comic book in English

34,96% 23,68% 41,35%

Read word lists with glossary or grammar

27,44% 37,97% 34,59%

Read a review for a popular film or book in English

34,21% 28,20% 37,59%

Read the lyrics for a song or poem in English

46,99% 19,55% 33,46%

Read a manuscript for a film or play in English

40,60% 21,80% 37,59%

Speak to my teacher in English

53,38% 15,41% 31,20%

Tell others about my interests in English

41,73% 26,32% 31,95%

Hold a presentation in front of the class or a few students in English

29,70% 43,98% 26,32%

Create and speak in a podcast or radio program in English 39,10% 31,95% 28,95% Sing in English 43,61% 33,08% 23,31% Be an actress/actor in a film or play in English 45,86% 27,07% 27,07%

Write a letter to an English-speaking person

50,75% 19,55% 29,70%

Write a book/story in English

40,60% 31,58% 27,82%

Write a news article in English

21,80% 43,23% 34,96%

Write a review for a film or book in English

25,19% 39,10% 35,71%

Write about my interests in English (favorite hobby, favorite animal, favorite activity, favorite travel destination)

25

Write a job application in English

38,35% 27,44% 34,21%

Write a song or poem in English

38,72% 30,08% 31,20%

Write a manuscript for a film or play in English

35,71% 30,08% 34,21%

Have a conversation with an English-speaking person

55,26% 15,41% 29,32%

Have a conversation with a close friend in English

62,78% 9,40% 27,82%

Participate in a job interview in English

33,46% 32,71% 33,83%

Chat with an English-speaking person online

59,40% 15,04% 25,56%

Do work-sheets with grammar exercises

23,31% 43,23% 33,46%

Play a game in English, for example Monopoly

65,04% 9,40% 25,56%

Learn about another culture 44,36% 24,06% 31,58%

Play a computer game/video game

63,91% 15,41% 20,68%

10.2 Questionnaire Results (School A)

Table 11. Indications of how students at School A think certain educational activities affect

their motivation

“When I get to...” 1. I BECOME MOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 2. I BECOME UNMOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 3. NO DIFFERENCE Listen to instructions to a task in English 29,47% 18,95% 51,58% Listen to a presentation in English 38,95% 13,68% 47,37%

Listen to and watch the news in English

38,95% 15,79% 45,26%

Listen to a podcast or a radio program in English

36,84% 12,63% 50,53%

Listen to a song in English 64,21% 4,21% 31,58%

Watch a film, a TV-program, or a play in English

80,00% 1,05% 18,95%

Read an email/letter from an English-speaking person

46,32% 10,53% 43,16%

Read a book in English 52,63% 15,79% 31,58%

Read a news article in English

25,26% 21,05% 53,68%

Read a comic book in English

33,68% 14,74% 51,58%

Read word lists with glossary or grammar

27,37% 29,47% 43,16%

Read a review for a popular film or book in English

32,63% 16,84% 50,53%

Read the lyrics for a song or poem in English

49,47% 14,74% 35,79%

Read a manuscript for a film or play in English

48,42% 11,58% 40,00%

Speak to my teacher in English

61,05% 8,42% 30,53%

Tell others about my interests in English

26

Hold a presentation in front of the class or a few students in English

30,53% 30,53% 38,95%

Create and speak in a podcast or radio program in English 43,16% 24,21% 32,63% Sing in English 41,05% 25,26% 33,68% Be an actress/actor in a film or play in English 47,37% 21,05% 31,58%

Write a letter to an English-speaking person

51,58% 14,74% 33,68%

Write a book/story in English

54,74% 14,74% 30,53%

Write a news article in English

29,47% 29,47% 41,05%

Write a review for a film or book in English

28,42% 28,42% 43,16%

Write about my interests in English (favorite hobby, favorite animal, favorite activity, favorite travel destination)

53,68% 13,68% 32,63%

Write a job application in English

43,16% 15,79% 41,05%

Write a song or poem in English

36,84% 24,21% 38,95%

Write a manuscript for a film or play in English

42,11% 20,00% 37,89%

Have a conversation with an English-speaking person

63,16% 7,37% 29,47%

Have a conversation with a close friend in English

52,63% 4,21% 43,16%

Participate in a job interview in English

40,00% 18,95% 41,05%

Chat with an English-speaking person online

61,05% 8,42% 30,53%

Do work-sheets with grammar exercises

24,21% 34,74% 41,05%

Play a game in English, for example Monopoly

58,95% 7,37% 33,68%

Learn about another culture 55,79% 9,47% 34,74%

Play a computer game/video game

27

10.3 Questionnaire Results (School B)

Table 12. Indications of how students at School B think certain educational activities affect

their motivation

“When I get to...”

1. I BECOME MOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 2. I BECOME UNMOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 3. NO DIFFERENCE Listen to instructions to a task in English 36,70% 21,10% 42,20% Listen to a presentation in English 39,45% 20,18% 40,37%

Listen to and watch the news in English

37,61% 24,77% 37,61%

Listen to a podcast or a radio program in English

38,53% 24,77% 36,70%

Listen to a song in English 61,47% 11,01% 27,52%

Watch a film, a TV-program, or a play in English

84,40% 3,67% 11,93%

Read an email/letter from an English-speaking person

42,20% 18,35% 39,45%

Read a book in English 35,78% 35,78% 28,44%

Read a news article in English

28,44% 30,28% 41,28%

Read a comic book in English

34,86% 26,61% 38,53%

Read word lists with glossary or grammar

33,03% 33,94% 33,03%

Read a review for a popular film or book in English

34,86% 32,11% 33,03%

Read the lyrics for a song or poem in English

50,46% 15,60% 33,94%

Read a manuscript for a film or play in English

36,70% 22,94% 40,37%

Speak to my teacher in English

55,05% 14,68% 30,28%

Tell others about my interests in English

34,86% 30,28% 34,86%

Hold a presentation in front of the class or a few students in English

31,19% 47,71% 21,10%

Create and speak in a podcast or radio program in English 32,11% 33,94% 33,94% Sing in English 44,95% 34,86% 20,18% Be an actress/actor in a film or play in English 44,04% 28,44% 27,52%

Write a letter to an English-speaking person

49,54% 22,02% 28,44%

Write a book/story in English

29,36% 37,61% 33,03%

Write a news article in English

14,68% 49,54% 35,78%

Write a review for a film or book in English

24,77% 39,45% 35,78%

Write about my interests in English (favorite hobby, favorite animal, favorite activity, favorite travel destination)

28

Write a job application in English

34,86% 31,19% 33,94%

Write a song or poem in English

38,53% 29,36% 32,11%

Write a manuscript for a film or play in English

32,11% 33,94% 33,94%

Have a conversation with an English-speaking person

52,29% 17,43% 30,28%

Have a conversation with a close friend in English

67,89% 11,01% 21,10%

Participate in a job interview in English

28,44% 38,53% 33,03%

Chat with an English-speaking person online

56,88% 16,51% 26,61%

Do work-sheets with grammar exercises

22,94% 41,28% 35,78%

Play a game in English, for example Monopoly

65,14% 11,01% 23,85%

Learn about another culture 44,04% 21,10% 34,86%

Play a computer game/video game

72,48% 11,01% 16,51%

10.4 Questionnaire Results (School C)

Table 13. Indications of how students at School C think certain educational activities affect

their motivation

“When I get to...” 1. I BECOME MOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 2. I BECOME UNMOTIVATED TO LEARN ENGLISH 3. NO DIFFERENCE Listen to instructions to a task in English 32,26% 29,03% 38,71% Listen to a presentation in English 37,10% 24,19% 38,71%

Listen to and watch the news in English

56,45% 22,58% 20,97%

Listen to a podcast or a radio program in English

53,23% 24,19% 22,58%

Listen to a song in English 59,68% 16,13% 24,19%

Watch a film, a TV-program, or a play in English

93,55% 3,23% 3,23%

Read an email/letter from an English-speaking person

41,94% 30,65% 27,42%

Read a book in English 40,32% 35,48% 24,19%

Read a news article in English

22,58% 38,71% 38,71%

Read a comic book in English

37,10% 32,26% 30,65%

Read word lists with glossary or grammar

17,74% 58,06% 24,19%

Read a review for a popular film or book in English

35,48% 38,71% 25,81%

Read the lyrics for a song or poem in English

37,10% 33,87% 29,03%

Read a manuscript for a film or play in English

35,48% 35,48% 29,03%

Speak to my teacher in English

38,71% 27,42% 33,87%

Tell others about my interests in English

29

Hold a presentation in front of the class or a few students in English

25,81% 58,06% 16,13%

Create and speak in a podcast or radio program in English 45,16% 40,32% 14,52% Sing in English 45,16% 41,94% 12,90% Be an actress/actor in a film or play in English 46,77% 33,87% 19,35%

Write a letter to an English-speaking person

51,61% 22,58% 25,81%

Write a book/story in English

38,71% 46,77% 14,52%

Write a news article in English

22,58% 53,23% 24,19%

Write a review for a film or book in English

20,97% 54,84% 24,19%

Write about my interests in English (favorite hobby, favorite animal, favorite activity, favorite travel destination)

54,84% 25,81% 19,35%

Write a job application in English

37,10% 38,71% 24,19%

Write a song or poem in English

41,94% 40,32% 17,74%

Write a manuscript for a film or play in English

32,26% 38,71% 29,03%

Have a conversation with an English-speaking person

48,39% 24,19% 27,42%

Have a conversation with a close friend in English

69,35% 14,52% 16,13%

Participate in a job interview in English

32,26% 43,55% 24,19%

Chat with an English-speaking person online

61,29% 22,58% 16,13%

Do work-sheets with grammar exercises

22,58% 59,68% 17,74%

Play a game in English, for example Monopoly

74,19% 9,68% 16,13%

Learn about another culture 27,42% 51,61% 20,97%

Play a computer game/video game