Consumption

Research and Policies

Research and Policies

THE SWEDISH ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY

Orders

Tel: +46 (0)8-505 933 40 Fax: +46 (0)8-505 933 99

E-mail: natur@cm.se

Address: CM-Gruppen, Box 110 93, SE-161 11 Bromma, Sweden Internet: www.naturvardsverket.se/bokhandeln

The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency

Tel +46 (0)8-698 10 00, Fax +46 (0)8-20 29 25 E-mail: natur@naturvardsverket.se

Address: Naturvårdsverket, SE-106 48 Stockholm, Sweden Internet: www.naturvardsverket.se

ISBN 91-620-5460-7.pdf ISSN 0282-7298

© Naturvårdsverket 2005

Digital Publication Cover photos: © Digital Vision Ltd

Preface

Global sustainable development requires wide-ranging changes in the way societies consume and produce, according to the agreement reached at the UN Summit Meeting held in Johannesburg, in 2002. Although this field has assumed significant importance during the past decade, thus far, the conceptual development of sus-tainable consumption has not been translated into practical strategies and instru-ments to the same extent as is the field of sustainable production.

The goal of this study is to describe and analyse recent initiatives of OECD countries in research, policies and other activities addressing sustainable consump-tion. The study also discusses gaps and potential future research needs and policy intervention. These issues are important to understand for policy makers, academia and other relevant actors in order to facilitate the development of a coherent and systematic sustainable consumption strategy.

The report is written for the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency by Dr Oksana Mont and Dr Andrius Plepys, both of whom are with the International Institute for Industrial Environmental Economics (IIIEE) at Lund University, Swe-den. The content of the report is solely the responsibility of its authors, and there-fore do not necessarily represent the view of the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency.

Stockholm, March 2005

Content

Preface 3

Executive Summary 7

Sammanfattning 11

1 Introduction 15

2 Goals, methods and limitations of this study 17

3 Consumption phenomenon 19

4 Consumption studies in different disciplines 27

4.1 The simple model of neo-classical economics 27

4.2 Modern consumption theories 29

4.3 Environmental research on consumption 39

4.4 Interpretation of main consumption-related research streams 44 5 Stakeholders in the sustainable consumption discourse 49

5.1 Governmental stakeholders 49

5.2 Business organisations 55

5.3 Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) 56

5.4 Interpretation of stakeholders’ roles in sustainable consumption 58

6 Policy role in addressing sustainable consumption 61

6.1 Policy principles 61

6.2 Policies and strategies in the European Union 62

6.3 Instruments 65

6.4 Interpretation of policy instruments – effectiveness vs. feasibility 69

7 Conclusions 73

ANNEX A. Major events and key publications on sustainable consumption 77

ANNEX B. Relevant links 83

ANNEX C. Relevant publications 85

List of figures

Figure 1: Total and per capita energy consumption in 1995……… 20

Figure 2. Some examples of growing total consumption………. 22

Figure 3. Energy consumption trends in OECD since 1970s……….. 23

Figure 4. The NOA model of consumer behaviour……….. 30

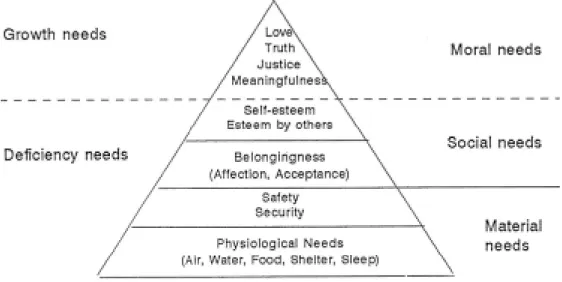

Figure 5. Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs………. 31

Figure 6. Thresholds of happiness in different countries……….. 35

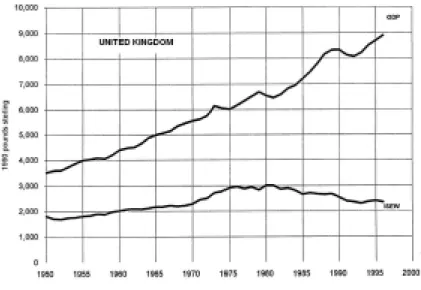

Figure 7a. Difference between the Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare (ISEW) and GDP in the UK during 1950-1996……… 35

Figure 7b. Difference between the Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare (ISEW) and GDP in Sweden during 1950-1996 ……….. 36

List of tables Table 1. Consumer spending and population by region in 2000……… 21

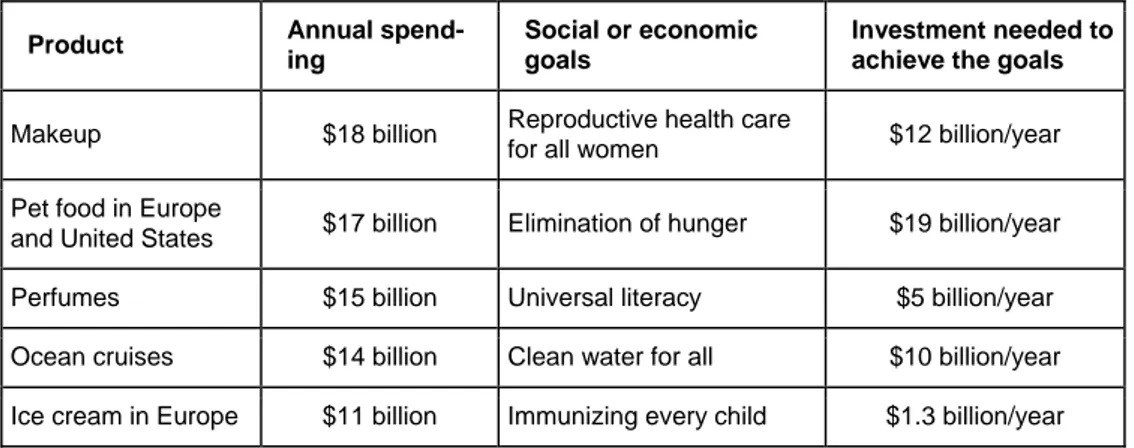

Table 2. Global annual expenditures on products and investments need for different social goals……….. 21

Table 3. Three domains of consumption with examples of types of indicators………. 44

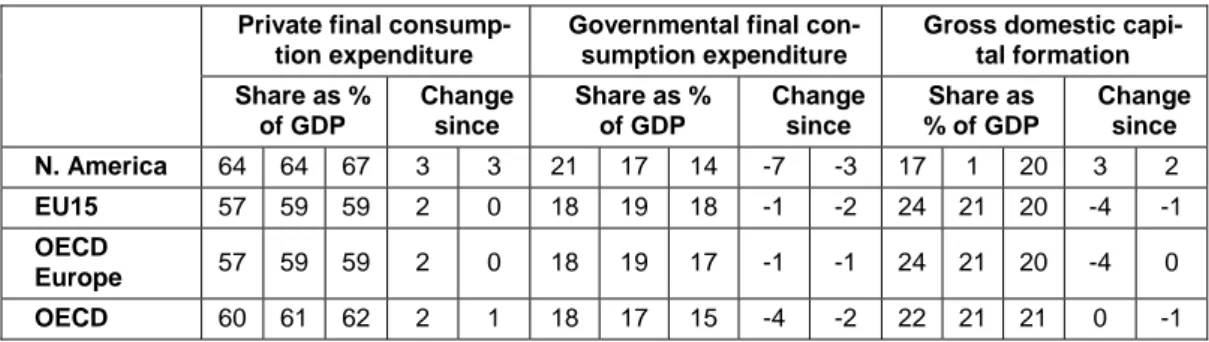

Table 4. Consumption expenditures as shares of GDP in OECD………. 59

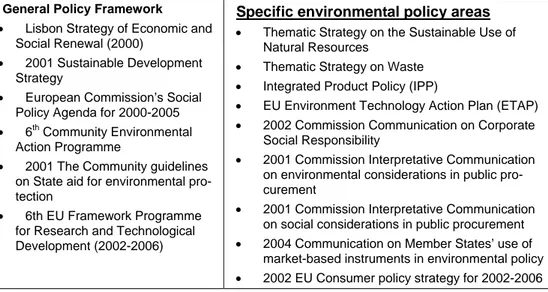

Table 5. EU strategies and polices for sustainable production & consumption………. 63

Table 6. Evaluation of effectiveness and feasibility of policy instruments……… 69

Table 7. Timetable of major events and key publications on the issue of sustainable consumption………. 77

List of abbreviations

CP Cleaner Production

CSR Corporate Social Responsibility

EPDs Environmental Product Information

EPR Extended Producer Responsibility

ETAP Environment Technology Action Plan

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GMOs Genetically Modified Organisms

ICT Information And Communication Technologies

IPP Integrated Product Policy

ISEW Index Of Sustainable Economic Welfare

LCA Life Cycle Assessment

NGOs Non-Governmental Organisations

NOA Needs-Opportunities-Abilities

POEMS Product-Oriented Environmental Management Systems

PSS Product-Service Systems

SC Sustainable Consumption

SPC Sustainable Consumption And Production

WBCSD World Business Council For Sustainable Development

WTA Willingness-To-Accept WTP Willingness-To-Pay

Executive Summary

In recent decades, the focus of environmental approaches has been on pollution control, cleaner production and improving resource efficiency on the production side. At the end of the 1990s, the scope widened to include post consumer waste collection and management with an emphasis on shifting this responsibility to pro-ducers. As a result, some tangible improvements in reducing the consumption of primary resources have been achieved. However, final consumption has been growing alongside increasing populations and affluence, so that efficiency im-provements on a per product basis have been negated by the increased total sumption. It became apparent that without addressing patterns and levels of con-sumption, it may not be possible to reach the vision of sustainable development and the debate on the need to address sustainable consumption has gradually entered the political agenda.

Consumption is a sensitive area for debate facing a number of dilemmas, such as the consumer sovereignty principle that questions the right to consume. How much is enough? Does material prosperity provide happiness and can it be bal-anced with environmental goals? Do developing nations have the right to attain life standards enjoyed in the developed countries? Is it moral to question this right? These questions clash with a number of personal, political and economic interests of different stakeholders and are therefore difficult to address. One of the key ques-tions concerns the definition of sustainable consumption – what are the sustainable levels of consumption? The next question is what are the best strategies to reach sustainable consumption without compromising political interests and socio-economic goals?

This study aims to provide a critical overview of the current debate, research trends and their main outcomes relating to the area of sustainable consumption. The study focuses on current research trends and the activities of main stakeholders and discusses the gaps in the existing range of initiatives and policy instruments towards sustainable consumption. The main focus is on research outcomes, policies and practical initiatives in developed countries.

The consumption phenomenon is being studied in a number of key research disciplines, such as economics, psychology and sociology, where the role and mechanisms of consumption are addressed on individual, household and society levels. To a large extent, the disciplines complement each other allowing for a more comprehensive picture of consumption.

Economic studies focus on how general economic forces in society on

na-tional, regional or company levels shape consumption levels and patterns. The field of economics has been traditionally dominated by neo-classical views based on assumptions about utility maximisation and the bounded rationality of individuals. These views regard consumers as rational decision-makers immune to external influences with price and income factors as the main factors in consumer decision-making. However, the neo-classical view has been questioned in modern consump-tion theories with contribuconsump-tions from the fields of psychology and sociology.

Consumer behaviour has been found to be far more complicated than just a rational response to price signals being influenced by different internal and external drivers induced by human psychology, social norms and institutional settings.

Sociological studies focus on how various institutions in society affect

con-sumption patterns and investigate the formation processes around concon-sumption practices. The major themes studied are the influences of social culture, social class and family, ethnic and religious groups. Social institutions, social groups, ideolo-gies and behaviours mutually reinforce each other and shape the development of society. Many studies focus on why people buy goods, how products satisfy con-sumer preferences and how products become symbols of meaning in society. Soci-ology proposes that consumer choice is influenced by functional, conditional, so-cial, emotional and epistemic values of products. Changes of values are often ex-plained from evolutionary and generational perspectives.

An important line of sociological research analyses institutional influences, such as family, religion and the education system. Social class also affects con-sumption patterns to a large degree, because people who belong to the same class share similar values, lifestyles and interests. Some fields in sociology focus on the notions of identity, image and lifestyle and study the role of goods in distinguishing between different classes and reinforcing identity within a certain class.

In the field of psychological studies, it has been found that consumer’s pur-chasing decisions are influenced by emotions and habits, which in turn are formed by personal attitudes and motivations. An important component is the feeling of satisfaction, which, according to Maslow’s hierarchy, is achieved by fulfilling a wide range of needs, spanning from material to social and moral needs. Some of the psychological drivers, such as habits, can be shaped by education in a relatively short time, while others, especially those related to societal pressures, are more difficult to change without addressing the issues of social culture. An important question discussed in both psychology and sociology is the notion of happiness and the means of achieving it. Currently, the ultimate measure of happiness is eco-nomic growth and material wealth measured in monetary terms such as gross do-mestic product (GDP) per capita. However, sociologists (e.g Max-Neef) agree that the relationship between GDP and the level of happiness is highly non-linear. Therefore, other indicators, such as the index of sustainable economic welfare (ISEW), are suggested.

If defined as a separate discipline, environmental studies on sustainable con-sumption mainly focus on whether and how environmental considerations are a decisive factor in purchasing decisions, how society can address growing consump-tion levels and whether eco-efficiency strategies are sufficient for the vision of sustainable development. In the past, environmental issues used to be addressed by ecologists, who generally displayed a rather modest familiarity with the complexity of consumer behaviour and the role of economic, psychological and sociological aspects. Recently, however, an increasing number of environmental studies are performed in the spirit of multidisciplinary research by trying to combine the knowledge from different disciplines.

Important streams of environmental studies focus on accounting material flows and environmental impacts related to product lifecycle. Material flow analysis (MFA), ecological footprint and input-output assessments are useful for analysing consumption issues on an aggregate level. However, all of these suffer from certain methodological drawbacks and are still in the evolutionary stage. For example, LCAs are useful in studying specific products and processes, but involve a lot of subjective decisions. MFA-based tools provide answers for issues only on an ag-gregate level and are not able to adequately capture toxicological impacts. Cer-tainly, some methodological developments, such as hybrid input-output LCAs, are likely to improve these assessment methods to some extent.

Most consumption-oriented environmental studies suggest that technological solutions directed to improving resource productivity are not sufficient in curbing the environmental effects of consumption. Solutions should be based not only on changing consumption patterns, but also on reducing the levels of consumption. The most radical views on reducing the levels of consumption are based on princi-ples of sufficiency. However, most of the activities today deal with changing con-sumption patterns, which is addressed by strategies of material substitution, pollu-tion prevenpollu-tion, consumer informapollu-tion and the optimisapollu-tion of end-of-life man-agement practices. The concept of dematerialisation and the shift from product- to

service-based consumption in the framework of product-service systems (PSS) are

among the newest research streams. However, there is still a significant gap in understanding the environmental impacts of alternative consumption systems based on product to service substitution. It is not a given that servicising ultimately leads to lower environmental impacts and it is important to understand what are the main prerequisites on the systems’ level that lower the impacts. Furthermore, little is known regarding the service features and functions that would shift consumer choices towards services as alternatives to the existing products.

The overview of stakeholders in sustainable consumption identified govern-ments, business and non-governmental organisations as the main players. NGOs and inter-governmental organisations are the most active stakeholders in the sus-tainable consumption debate, but they also have varying and vested interests. One of the most profound problems is the prevailing perception by many governments that reducing consumption levels challenges the goals of economic growth,

techno-logical innovation and international competitiveness. Therefore,

inter-governmental organisations, although advocating the need to reduce consumption levels, often lack initiatives and support in reaching tangible results.

Most of today’s businesses perceive their contribution to sustainable consump-tion in terms of eco-efficiency strategies, which are oriented at improving resource productivity of the supply side. However, this hardly addresses the problem of final consumption, because productivity improvements often lead to rebound effects and backfire in terms of increased consumption of cheaper product or service. Address-ing sustainable consumption requires increasAddress-ing the resource efficiency of input materials as well as reducing the levels of final consumption. The latter calls for significant commitments from individuals, but there could also be a role for busi-ness actors for which sustainable consumption can imply new busibusi-ness

opportunities not currently seen by mainstream businesses. For instance, instead of placing the core of profit making on increasing product sales, innovative compa-nies see the development potential in providing alternative service solutions, which simultaneously leads to a reduction in the levels of material goods needed for de-livering service to consumers and users.

Non-governmental consumer organisations (NGOs) seem to be the most

pro-found actors in the sustainable consumption debate by challenging the current eco-nomic premises and calling for sufficiency approaches. Most of their campaigns deal with changing consumer behaviour and/or raising awareness. Unfortunately, NGOs lack the power of international governmental organisations and business actors to have a wide outreach and make a significant impact on actual improve-ment. Therefore, combining inter-governmental, business and NGO activities could be an effective strategy for shifting towards more sustainable consumption.

Policy makers seem to be the most relevant actors to mediate the change to-wards more sustainable consumption. However, in dealing with sustainable con-sumption there is a noticeable lack of strategies that challenge the ascon-sumptions of economic systems based on material growth and that could conceive ways of shift-ing from material-intensive consumer culture to a society with less materialistic aspirations. Certainly, such strategies should address not only the production side, but also the consumption dimension, propagating not only efficiency approaches, but also sufficiency strategies. Sufficiency strategies, increasing awareness and supporting citizen actions of private consumers are components of an ultimate preventive strategy that can lead to the reduction of aggregate environmental im-pacts. To provide a fruitful ground for sufficiency strategies, governments need to change the institutional frameworks in society and create conditions in which pro-ducers would be interested in finding new business centres using less resource-intensive products and services.

Obviously, no single tool or approach can change the framework conditions in society. Therefore, a national sustainable consumption strategy could be the first step to a more integrative approach in dealing with consumption-related problems. Policy interventions combined with other instruments can facilitate the creation of economic frameworks for new business strategies to emerge.

Furthermore, international dialogue is needed. A dialogue on the EU level can provide a forum for finding potential solutions. Finally, the shift towards sustain-able consumption has to emerge in industrialised countries that will inspire the rest of the world to lead a less material intensive existence.

Sammanfattning

Under de senaste årtiondena har fokus för miljöåtgärder framför allt varit kontroll av utsläpp av föroreningar, renare teknik och förbättrad resurseffektivitet på pro-duktionssidan. I slutet av 1990-talet breddades fokus även till insamling och han-tering av konsumtionsavfall med bland annat syftet att öka ansvaret hos producen-terna. Detta har inneburit framsteg i form av minskad förbrukning av vissa råvaru-resurser. Konsumtionsnivån har dock samtidigt ökat med ökad befolkningsmängd och ökat välstånd, och effektivitetsförbättringar på produktnivå har ätits upp av den ökade totalkonsumtionen. Det har visats sig att det inte är möjligt att uppnå visio-nen om hållbar utveckling om inte våra konsumtionsmönster och konsumtionsni-våer adresseras, och debatten om behovet av hållbar konsumtion har stegvis tagit plats på den politiska agendan.

Konsumtion är ett känsligt debattområde med ett antal svåra frågeställningar, till exempel principen om konsumentens suveränitet och ifrågasättandet av rätten att konsumera. Hur mycket är tillräckligt? Är materiellt välstånd nyckeln till lycka och går det att balansera med mål för miljön? Har utvecklingsländer rätt att uppnå den levnadsstandard som industriländer åtnjuter? Är det moraliskt att ifrågasätta denna rättighet? Dessa frågor kolliderar med ett antal personliga, politiska och ekonomiska intressen hos olika intressenter och är därför svåra att hantera. En av nyckelfrågorna rör definitionen av hållbar konsumtion – vilka konsumtionsnivåer är hållbara? Nästa fråga är vilka de bästa strategierna är för att uppnå hållbar kon-sumtion utan att ge avkall på politiska intressen och socioekonomiska mål?

Denna studie syftar till att ge en kritisk översikt över den aktuella debatten, forskningstrender och dess huvudsakliga slutsatser inom området hållbar konsum-tion. Studien fokuserar på aktuella forskningstrender och viktiga intressenters akti-viteter, samt diskuterar brister bland befintliga initiativ och strategiska instrument för att uppnå hållbar konsumtion. Huvudfokus är forskningsresultat, policys och praktiska initiativ i industriländer.

Konsumtion som fenomen studeras i ett antal nyckeldiscipliner inom forsk-ningen, som ekonomi, psykologi och sociologi, där konsumtionens roll och meka-nismer behandlas på individuell nivå, hushålls- och samhällsnivå. De olika disci-plinerna kompletterar varandra i stor utsträckning, vilket ger möjlighet till en mer mångsidig bild av konsumtionsfrågan.

Ekonomiska studier fokuserar på hur allmänna ekonomiska drivkrafter i

sam-hället påverkar konsumtionsnivåer och konsumtionsmönster på nationell, regional och företagsnivå. Det ekonomiska området har traditionellt dominerats av det neo-klassicistiska synsättet, baserat på antaganden om nyttomaximering och individers rationella beteende. Detta synsätt betraktar konsumenter som rationella beslutsfat-tare som är opåverkbara av externa influenser och där pris och inkomst är huvud-faktorer i konsumenternas beslutsfattande. Det neo-klassicistiska synsättet har dock ifrågasatts i moderna konsumtionsteorier efter inspel från psykologin och sociolo-gin. Konsumenternas beteende har visat sig vara mycket mer komplicerat än bara en rationell reaktion på prissignaler, och påverkas av olika interna och externa

drivkrafter föranledda av psykologiska faktorer, sociala normer och institutionella ramar.

Sociologiska studier fokuserar på hur olika institutioner i samhället påverkar

konsumtionsmönster och undersöker processen kring hur konsumtionsvanor ska-pas. Huvudsakliga teman som studerats är inverkan av social kultur, socialgrupp och familj, etniska och religiösa grupperingar. Sociala institutioner, socialgrupper, ideologier och beteende förstärker varandra ömsesidigt och skapar samhällsutveck-lingen. Många studier fokuserar på varför människor köper varor, hur produkterna tillfredsställer konsumenternas preferenser och hur produkterna blir symboler för meningsfullhet i samhället. Sociologin menar att konsumenternas val influeras av funktionella, villkorliga, sociala, emotionella och kunskapsteoretiska produktvär-den. Förändringar i värderingar förklaras ofta från ett utvecklings- och genera-tionsperspektiv.

En viktig linje inom sociologisk forskning analyserar institutionell påverkan, till exempel familj, religion och utbildningssystemet. Socialgrupp påverkar också konsumtionsmönster i hög grad, eftersom människor som tillhör samma klass delar liknande värderingar, livsstilar och intressen. Vissa fält inom sociologin fokuserar på begreppen identitet, image och livsstil och studerar varornas roll vid identifie-ring med olika klasser och vid förstärkning av identiteten inom en viss klass.

I psykologiska studier har det framkommit att konsumenternas inköpsbeslut påverkas av känslor och vanor, som i sin tur skapas av personliga attityder och motivation. En viktig komponent är känslan av att vara nöjd som, enligt Maslows hierarki, uppnås genom att tillfredsställa ett brett urval av behov som sträcker sig från materiella till sociala och andliga behov. En del psykologiska drivkrafter, till exempel vanor, kan skapas via utbildning inom relativt kort tid, medan andra, sär-skilt de som kan hänföras till tryck från samhället, är svårare att förändra utan att adressera sociokulturella frågeställningar. En viktig fråga som diskuteras inom både psykologin och sociologin är lyckobegreppet och sätten att uppnå lycka. För närvarande är det dominerande måttet på lycka ekonomisk tillväxt och materiell välfärd, som till exempel mäts i bruttonationalprodukt (BNP) per capita. Sociologer (till exempel Max-Neef) är emellertid överens om att förhållandet mellan BNP och lyckonivå inte alls är linjär. Därför föreslår man andra indikatorer, till exempel Index of sustainable economic welfare (ISEW).

Miljöstudier avseende hållbar konsumtion, om det definieras som en separat

gren, fokuserar huvudsakligen på om och hur miljöaspekter är en avgörande faktor vid inköpsbeslut, hur samhället kan ta itu med växande konsumtionsnivåer och huruvida strategier för eko-effektivitet är tillräckliga för visionen om en hållbar utveckling. Tidigare brukade miljöfrågor hanteras av ekologer som i allmänhet visade sig vara ganska okunniga om komplexiteten hos konsumenternas beteende samt de ekonomiska, psykologiska och sociologiska aspekternas roll. På senare tid har dock miljöstudier i tvärvetenskaplig forskningsanda ökat genom att försöka förena kunskap från olika discipliner.

Betydelsefulla inriktningar på miljöstudier fokuserar på redovisning av materi-alflöden och miljöpåverkan som hänför sig till produktens livscykel (miljöräken-skaper). Materialflödesanalyser (MFA), ekologiska fotavtryck och

input/output-analyser är användbara vid analys av konsumtionsfrågor på en aggregerad nivå. Alla dessa har dock vissa metodologiska brister och är fortfarande på utvecklings-stadiet. Livscykelanalyser är till exempel användbara vid studier av specifika pro-dukter och processer, men inbegriper en mängd subjektiva beslut. MFA-baserade verktyg ger endast svar på frågor på en aggregerad nivå och tar inte hänsyn till toxikologisk påverkan på ett tillfredsställande sätt. Viss metodutveckling, till ex-empel kombination av traditioenlla livscykelanalyser och makroekonomiska kaly-ler/räkenskaper av in- och utgående material (hybrid input-output LCAs), kommer troligen att förbättra dessa bedömningsmetoder i viss utsträckning.

De flesta konsumtionsinriktade miljöstudier hävdar att tekniska lösningar som riktas mot att förbättra resursproduktivitet inte är tillräckliga för att hantera miljöef-fekterna från konsumtionen. Lösningar bör inte bara baseras på förändrade kon-sumtionsmönster utan även på att minska konsumtionsnivåerna. De mest radikala uppfattningarna avseende minskade konsumtionsnivåer baseras på principer om tillräcklighet (sufficiency). I dag handlar dock de flesta aktiviteter om förändring av konsumtionsmönster med hjälp av strategier om materialutbyte, förhindrande av föroreningar, konsumentinformation och bästa möjliga slutliga omhändertagande av produkterna. Konceptet dematerialisering och övergången från varu- till

tjäns-tebaserad konsumtion inom ramverket för varu/tjänstesystem (PSS – Product

Ser-vice Systems) är en av de nyaste strömningarna inom forskningen. Det finns emel-lertid fortfarande en betydande kunskapsbrist att förstå miljöpåverkan av alternati-va konsumtionssystem som baseras på övergång från alternati-varor till tjänster. Det är inte givet att tjänster alltid leder till lägre miljöpåverkan och det är viktigt att förstå viktiga förutsättningar på systemnivå för att påverkan ska minska. Vidare är kun-skapen låg om de egenskaper och funktioner hos tjänster som skulle kunna ändra konsumenternas inställning så att de väljer tjänster som alternativ till befintliga varor.

I översikten över intressenter inom hållbar konsumtion identifierades stat, före-tag och frivilliga icke-statliga organisationer (NGO – Non Governmental Organisa-tions) som huvudaktörer. NGOs och mellanstatliga organisationer är de mest aktiva intressenterna i debatten om hållbar konsumtion, de har också olika intressen och utgångspunkt i frågan. Ett av de mest djupgående problemen är den hos många statliga aktörer rådande uppfattningen om att minskade konsumtionsnivåer utmanar

målen för ekonomisk tillväxt, tekniskt nyskapande och internationell konkurrens-kraft. Det saknas därför ofta initiativ och stöd hos mellanstatliga organisationer för

att åstadkomma påtagliga resultat, även om de förespråkar behovet av att minska konsumtionsnivåer.

Majoriteten av dagens företag ser sina bidrag till hållbar konsumtion inom ra-men för strategier för eko-effektivitet som är inriktade på att förbättra resurspro-duktiviteten på utbudssidan. Detta synsätt inriktar sig dock knappast på problemet med slutlig konsumtion, eftersom effektiviseringar i produktivitet ofta leder till återverkande effekter som slår tillbaka i form av ökad konsumtion av billigare varor eller tjänster (rebound effects). Åtgärder för en hållbar konsumtion krävs avseende såväl ökad resurseffektivitet av ingående material, som minskade kon-sumtionsnivåer. Det senare förutsätter ett starkt engagemang från enskilda

perso-ner, men det kan också finnas en roll för näringslivets aktörer för vilka hållbar konsumtion kan innebära nya affärsmöjligheter som traditionella företag ännu inte har insett. Exempelvis kan ett nyskapande företag, i stället för att tjäna mer på ökad produktförsäljning, se en utvecklingspotential i att tillhandahålla alternativa tjänste-lösningar som samtidigt leder till minskning av den mängd material som krävs för att leverera tjänsten till konsumenter och användare.

NGOs på konsumentområdet verkar vara de mest insiktsfulla aktörerna i

debat-ten om hållbar konsumtion genom att utmana dagens ekonomiska antaganden och efterlysa tillvägagångssätt baserade på tillräcklighet (sufficiency approaches). De flesta av deras kampanjer handlar om att ändra konsumenternas beteende och/eller öka medvetenheten. NGOs saknar tyvärr styrkan som internationella statliga orga-nisationer och näringslivsaktörer har som innebär möjlighet att nå många och att ha en betydande inverkan på pågående insatser/framsteg. Det kan därför vara en effek-tiv strategi att kombinera akeffek-tiviteter i mellanstatliga organisationer, näringsliv och icke-statliga organisationer i övergången till en mer hållbar konsumtion.

Policyskapare är förmodligen den mest betydelsefulla aktören för att förmedla övergången till en mer hållbar konsumtion. Det finns dock en påtaglig brist på strategier som utmanar de ekonomiska systemens antaganden baserade på materiell tillväxt och som kan formulera tillvägagångssätt för att växla från en materialinten-siv konsumtionskultur till ett samhälle med mindre materialistiska strävanden. Sådana strategier skall inte bara omfatta produktionssidan utan även konsumtionen, och inte bara propagera för effektivisering utan även för tillräcklighet (sufficiency strategies). Tillräcklighetsstrategier, ökad medvetenhet och stöd till insatser av privata konsumenter är delar i en avgörande förebyggande strategi som kan leda till minskad total miljöpåverkan. För att tillhandahålla en fruktbar bas för tillräcklig-hetsstrategier (sufficiency strategies) behöver statsmakterna ändra samhällets insti-tutionella ramverk och skapa förutsättningar för tillverkare att intressera sig för att hitta nya affärsidéer för varor och tjänster som är mindre resursintensiva.

Ett enskilt verktyg eller tillvägagångssätt kan självklart inte ändra de grund-läggande förutsättningarna i samhället. En nationell strategi för hållbar konsumtion kan därför vara första steget mot ett mer integrerat tillvägagångssätt vid hantering av konsumtionsrelaterade problem. Initiativ på policynivå i kombination med andra initiativ och instrument kan underlätta skapandet av ekonomiska ramverk så att nya affärsstrategier kan utvecklas.

Det krävs dessutom en internationell dialog. En dialog på EU-nivå kan vara ett forum för att finna potentiella lösningar. Slutligen, övergången till hållbar konsum-tion måste utvecklas i de industrialiserade länderna som sedan inspirerar resten av världen att leva ett liv som är mindre materialintensivt.

1 Introduction

The technological and economic development of society is not only linked to in-creasing levels of affluence, but is also inevitably accompanied by environmental problems. During the last decade, the concepts of sustainable production and con-sumption have increased in importance. Since the early 1990’s, significant progress in the eco-efficiency movement, which aims at improving the environmental pro-file of production processes and products, has taken place. A majority of develop-ment strategies were designed to increase the efficiency of existing production processes, and later products, but very few have actually addressed consumption issues. While it was hoped that technical solutions would allow us to solve envi-ronmental problems, due to the constantly increasing population and affluence levels the eco-efficiency improvements, although very important and effective in tackling specific problems, have failed to reduce the aggregate impacts of increas-ing consumption. This calls for new strategies to address environmental and growth-related problems.

The notion of sustainable consumption (SC) is often used as an umbrella term for issues related to human needs, equity, quality of life, resource efficiency, waste minimisation, life cycle thinking, consumer health and safety, consumer sover-eignty, etc. Many of these issues have conflicting aims, which make them not eas-ily compatible in the strategic shift towards sustainable consumption and points to the complexity of the subject. There is still no consensus regarding the definition of sustainable consumption. Some actors treat consumption as a production issue and suggest that the reduction of the environmental problems of consumption is possi-ble though eco-efficiency improvements. Other actors equate sustainapossi-ble consump-tion to the ‘greening’ of markets, i.e. providing green product alternatives. Fur-thermore, there is no consensus regarding the scope of the efforts needed to address consumption-related problems. In other words, the debate centres on whether it is sufficient to change consumption patterns or if there is a need to also reduce sumption levels. Finally, the shift towards sustainable consumption involves con-flicts of interests on an individual level, i.e. it implies changing consumer behav-iour and adjusting lifestyles not only by “them”, but also by “me personally”.

A growing number of governmental initiatives and workshops on sustainable consumption in recent years have indicated that the field is coming into policy focus. Simultaneously, the conceptual developments on sustainable consumption do not seem to have been translated into practical strategies and instruments to the same extent as sustainable production strategies did.

There are also a number of successful NGOs that facilitate bottom-up changes in consumption patterns and consumer behaviour by directly working with and educating consumers and households. However, many agree that to have an effect these measures need to be disseminated to a much larger audience and be linked with policy instruments into a coherent sustainable consumption strategy. In order to facilitate the development of a coherent and systematic sustainable consumption strategy, it is important to understand the current level of development in the

sustainable consumption field and to investigate the reasons for the identified lack of research sophistication, practical developments and initiatives related to sustain-able consumption.

There is a broad range of different disciplines that deal with sustainable con-sumption issues, starting from economics, marketing, business strategies and social studies of consumer behaviour. Different policy studies have also started address-ing the issue of sustainable consumption, since conventional market mechanisms and eco-efficiency strategies are not always sufficient when addressing environ-mental externalities and environenviron-mental problems stemming from the levels of con-sumption. Conventional areas where policies are being developed in relation to consumption are prerequisites for information provision, taxing environmentally harmful activities and products and banning extremely dangerous substances. However, it is not clear whether existing policy measures take into account the knowledge from consumption research. Furthermore, since consumption and envi-ronmental problems are increasing, the current range of policy instruments seems insufficient

In this study, we are mapping out the major outcomes of the research on con-sumption and sustainable concon-sumption from various disciplines and discussing how this knowledge can be used for policy making and what needs to be addressed by future research activities and policy interventions. The study aims to contribute to the preparatory work of authorities on developing a national strategy for sustainable consumption. Relevant for the interests of policy makers will be the overview of the existing research initiatives and outcomes, including policy oriented research.

The following section details the goals of the study and describes the method-ology employed. Chapter 3 describes consumption-related problems with some statistical data. Chapter 4 summarises the main research streams relevant for this study in economic, sociological, psychological, environmental and policy research. In Chapter 5, the activities of the main stakeholders on sustainable consumption are presented. Chapter 6 discusses the roles of various stakeholders and the effective-ness and feasibility of various policy instruments for sustainable consumption. Conclusions are made in Chapter 7.

2 Goals, methods and

limitations of this study

The goal of this study is to provide a critical overview of current research activities

and their main outcomes concerning consumption and sustainable consumption fields by:

• Reviewing existing research initiatives and policy instruments towards sus-tainable consumption;

• Identifying gaps in the existing range of initiatives and policy instruments towards sustainable consumption.

The focus of the study is on research outcomes, policies and practical initiatives of

the EU and OECD countries in addressing sustainable consumption problems. Data was primarily collected via literature analysis, but also from interviews with rele-vant actors. The study comprised several stages:

1. A critical overview of existing research activities and their out-comes regarding sustainable consumption.

2. An analysis of the main policy documents on sustainable con-sumption written in the last decade by international organisations, based on discussion panels, seminars and workshops with different stakeholders. The outcome is an overview of how the sustainable consumption concept has been addressed at the international policy level and what the potential gaps and drawbacks in the proposed and discussed policy documents are.

3. The mapping out of non-governmental initiatives for sustainable consumption and an evaluation of their outcomes.

4. An analysis of the sustainable consumption field with regard to undertaken and potential future research needs and policy interven-tion.

This study outlines the progress towards sustainable consumption by describing recent initiatives in this field with a special focus on research- and policy-related activities. This report outlines existing research gaps and needs and the role of policy intervention as the possible solution to addressing sustainable consumption problems.

3 Consumption phenomenon

The industrial revolution was one of the most important drivers for reaching the current standards of living, lifestyles and consumption patterns. Industrialisation took place during several significant political and economic transformations in the North, such as colonisation, which secured access to cheap natural resources from the South. Competition for the lowest price and the reduction of manufacturing costs was accompanied with a number of structural changes on the macro-economic level, especially the pricing of natural resources. On the demand side, increasing urbanisation and growing incomes facilitated increasing consumption. A giant leap in production output and consumption levels was possible due to the increase in work productivity through a series of innovations in production sys-tems, such as the division of labour and technological modernisation.

Along with the industrial revolution, the ever-increasing international competi-tion became another driver for increasing productivity, which in turn allowed higher incomes and increased consumption. A number of technological forces gave an impetus to consumption, especially the invention of general-purpose technolo-gies such as electricity, the internal combustion engine, microwaves and communi-cation technology (Grübler 1998; Røpke 1999a; Grübler, Nakicenovic et al. 2002). At first, these technologies generated stand-alone products and applications, but later evolved into product systems, infrastructures, social practices, institutions and cultures. For example, the arrival of the car required creating road networks, traffic police, road administrations, driving schools, etc. The arrival of television induced the creation of broadcasting systems, studios, the advertising and film industries and so on.

Information and communication technologies (ICT) gave a new impetus to consumerism. The Internet became a powerful marketing channel, improved con-sumer access to information and created a perfect frictionless market with abundant information and close-to-zero transaction costs, which expanded markets in terms of time and space. The “one-click-shopping” e-commerce has dramatically chang-ed the way we find and buy products and services. These developments have a great environmental potential through the optimisation of supply chains (Romm, Rosenfield et al. 1999). Simultaneously, the increased availability of information on new products and services and the lower prices of goods stemming from optimi-sations on the market have resulted in higher consumption and negative environ-mental impacts.

Today, consumption is seen as an extremely important component in gross do-mestic product (GDP) – the main traditional indicator of economic growth. It is a widely accepted belief that economic growth, beyond eliminating poverty, will ultimately increase well-being and happiness. Therefore, many governments treat consumption growth as a positive phenomenon and promote it in many ways.

However, economic growth does not always leads to increased happiness, as indicated by several studies showing that materialistic societies are less happy than less materialistic ones. The industrial revolution and economic growth generated

side effects that put under threat the very goal of economic development – well-being. These are typically externalities, such as environmental pollution, health deterioration and increasing social disparities between the rich and the poor.

The expansion of global consumption expenditures allowed considerable ad-vances in human development resulting in substantial improvements in health care, communication and education. Concurrently, many environmental problems are linked to consumption. At this point a distinction must be made between resource and household consumption. The former refers to resource consumption on the supply side (i.e. the manufacturing and service industry) and the latter denotes consumption of final goods. In many cases, a reduction of resource consumption is a positive development in the eyes of many governments because it is a signal of increased productivity and the ability to produce more with less, i.e. higher com-petitiveness. On the other hand, a reduction of consumption on the supply side does not mean a reduction of final consumption. Very often low manufacturing costs translate into lower prices of final goods, which results in increased demand.

According to the Worldwatch Institute, the global consumer class (users of TVs, phones and the Internet along with the culture and ideals these products trans-mit) is about 1.7 billion people or more than a quarter of the world. Between 1960 and 2000, private consumption expenditures (household spending on goods and services) increased from $4.8 to $20 trillion.

Although part of this was induced by population growth, advancing economic prosperity stimulated most of the growth. The latter was possible due to increasing production efficiency. For example, a week’s output of an industrial worker today corresponds to four years of output in the 18th century. Furthermore, consumption is fuelled by enormous pressure through the advertising industry, which in 2002 had a global spending of $446 billion – a nine-fold increase from 1950

(Worldwatch Institute 2004). Figure 1 shows the disparities between industrial and developing countries in terms of per capita energy consumption. The gap between the rich and the poor has not diminished and in some cases has even widened.

61 12 29 192 42 343 100 345 9 92 114 20 102 8 0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350 400 Wo rl d Afr ic a As ia & th e Pa c if ic Eu ro p é & Ce n tr a l As ia La ti n A m e ri c a & t h e Ca ri b b e a n No rt h A m e ri c a W e s t A s ia e ne rgy c o ns um pt ion ( G J ) per capita total

However, the growth in prosperity in different parts of the world is highly unequal (Table 1). Industrial nations have far higher incomes and consumption levels than developing countries. As a result, regional disparities are still increasing. In 1999, for instance, some 2.8 billion people lived on less than $2 a day. In 2000, 1.1 bil-lion people did not have “reasonable access“ to safe drinking water and 2.4 bilbil-lion people lived without basic sanitation (Worldwatch Institute 2004).

Table 1. Consumer spending and population by region in 2000. (Source: Worldwatch Institute 2004.)

Region % of global expenditure % of global population

USA and Canada 31.5 % 5.2 %

Western Europe 28.7 % 6.4 %

East Asia and Pacific 21.4 % 32.9 %

Latin America and the Caribbean 6.7 % 8.5 %

Eastern Europe and Central Asia 3.3 % 7.9 %

South Asia 2.0 % 22.4 %

Australia and New Zealand 1.5 % 0.4 %

Middle East and North Africa 1.4 % 4.1 %

Sub-Saharan Africa 1.2 % 10.9 %

At the same time, improving the situation of the underprivileged is possible for less than what global population spends on trivial things, such as makeup, ice cream or pet food (Table 2). Other observations show that along with population growth, key consumption activities contributing to serious environmental problems, such as personal travel by car, amount of meet and fossil fuels consumed, have intensified (Figure 2).

Table 2. Global annual expenditures on products and investments need for different social goals. (Source: Worldwatch Institute 2004.)

Product Annual spend-ing

Social or economic goals

Investment needed to achieve the goals

Makeup $18 billion Reproductive health care

for all women $12 billion/year

Pet food in Europe

and United States $17 billion Elimination of hunger $19 billion/year

Perfumes $15 billion Universal literacy $5 billion/year

Ocean cruises $14 billion Clean water for all $10 billion/year

Source: C B Billion Source: FAO Kilograms Source EDF Source: LBL, DOE IGU IEA Million tons of oil equivalent

Trillion kilometers Million tons

World population, 1950-2002 World meat production per person, 1950-2002

Distance driven and carbon emitted by U.S. automobiles, 1970-2000

World fossil fuel consumption by source, 1950-2002 4,0 3,5 3,0 2,5 2,0 1,5 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 40 30 20 10 0 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 350 300 250 200 Distance d i Carbon i i Oi l Natural gas Coa l 4000 3000 2000 1000 0

Figure 2. Some examples of growing total consumption. (Source: Worldwatch Institute 2005.)

Total world final energy consumption has been growing faster than in OECD member countries, which can be explained by the increasing share of (presumably less energy intensive) service industries in developed countries and outsourcing of energy intensive industries into third countries (Figure 3). At the same time, energy consumption per capita has not decreased, which is a sign of increased affluence and higher levels of consumption. One of the facilitating factors to increasing con-sumption is diminishing prices of natural resources induced by the improvements in manufacturing technologies, which inevitably lead to rebound effects.

200 150 100 50 0 1971 1976 1981 1986 1991 1996 Index 1971=100 200 150 100 50 0 1971 1976 1981 1986 1991 1996 Index 1971=100 200 150 100 50 0 1971 1976 1981 1986 1991 1996 Index 1971=100

Total final consumption Intensities per unit of GDP Intensities per capita

North America OECD Pacific OECD Europe OECD Total

Figure 3. Energy consumption trends in OECD since 1970s. (Source: OECD 1999:55.)

The concept of rebound effects is often mentioned in discussions about productiv-ity improvements and is often used in the discourse on sustainable development and resource consumption. The concept refers to a positive feedback loop between productivity improvements, economic growth and the levels of consumption. The rebound effects are explained through market price mechanism and consumer be-haviour: as technological improvements increase resource efficiency, fewer re-sources are needed to produce the same amount of output, thus the cost per unit of production falls, which leads to increased demand of the output. The effect was first extensively discussed by energy economists in the 1980s demonstrating that higher efficiency in producing energy services resulted in lower energy price and higher consumption (Brookes 1979; Khazzoom 1980; Khazzoom 1986; Khazzoom 1987). Later research confirmed that rebound effects are taking place in all eco-nomic sectors and that they are closely tied to consumer behaviour (Berkhout, Muskens et al. 2000; Binswanger 2000). Furthermore, technological innovations of general purpose technologies, such as IT and Internet, also lead to complex re-bound effects across many economic sectors (Plepys 2002).

A four-tier taxonomy of rebound effects have been suggested (Greening, Greene et al. 2000). On the lowest tier are the traditional price effects, as defined by the energy economists above. The described increase in consumption, however, is not limitless. A consumer will increase the use of a cheap commodity until the limits of satiation or until budgetary tradeoffs with other expenditures.1 The limited consumption of such commodity in this case may result in savings, which will be used for increasing consumption of other commodities, or the so-called second

order rebound effects (Greening, Greene et al. 2000).

On a macro level, Greening et al. (2000) conceptualised economy-wide and

transformational effects. The former refer to readjustments of prices and quantities

of other commodities across all sectors as a consequence of price and 2nd order rebounds. The argument builds on the interrelationship of prices and outputs of

1

Consumption may also be limited by time limitations or behavioural constraints (e.g. social norms, fashion or effort level, see (Schneider, Hinterberger et al. 2001).

goods and resources in different markets, which form a unique equilibrium state. The transformational effects relate less to price mechanisms and more to the changes of consumer preferences, lifestyles, new habits and altered social institu-tions. These effects are the most obscure and, although describing transformational effects is conceptually possible, they are not practical analytically, as both theory and data are lacking (Greening, Greene et al. 2000, pg. 399).

This point can be considered as the limit to the economic explanation of re-bound effects. There are many other parameters affecting consumption desires and many are not related solely to product function and its price, but also to human factors such as consumers taste, image and fashion, brand identity, sentiments, etc. Therefore, other theories dealing with psychology and consumer behaviour issues

are needed. Consumption habits are indeed tied with human psychology and

be-haviour. The view that we consume things only for their function is very simplistic and in reality human consumption desires are formed by two components –basic needs and emotional satisfaction. The first one is driven by human aspirations to satisfy basic physical needs for food, clothing, shelter and mobility, while the sec-ond - by human desires to express a particular lifestyle determined by the symbolic values of goods (Sachs 1998; Sachs 1999).

Consumption has become an important issue in international policy since the early 1970s after The Club of Rome, a group of economists, scientists, and busi-ness leaders, published The Limits to Growth. The publication had drawn public attention to the rates of reaching the limits of Earth's carrying capacity along with the increasing affluence and population growth, resource depletion, and pollution generation. Sustainable consumption was proposed as a broad strategy to dealing with environmental problems and a number of national and international discus-sions, political discourses and research initiatives have been launched.

The first serious appearance of sustainable consumption issue on the interna-tional agenda was in 1992 at the internainterna-tional conference in Rio de Janeiro. Chap-ter 4 of the Agenda 21 declaration was devoted to changing consumption patChap-terns, where patterns of production and consumption were labelled as a cause of unsus-tainable development: “The major cause of continued deterioration of the global

environment is the unsustainable patterns of consumption and production, particu-larly in the industrialised countries. (Chapter 4, Agenda 21). Later, several

re-search institutions and international bodies followed up the issue of sustainable consumption. Most of the work focused on developing a better understanding of the role of consumption and especially patterns of production and consumption in meeting basic human needs and reducing overall environmental impact.

One of the important streams of research on sustainable consumption deals with different environmental indicators. A number of international organisations (EEA 1995; OECD 1999; Worldwatch Institute 2004) have funded projects to develop a set of indicators that could help trace the progress toward less consump-tive lifestyles.

Success in approaching sustainable consumption has been rather modest for several reasons. First, there is still no consensus on the definition and scope of sustainable consumption. Some treat consumption as part of production; others

equate it to greening the markets. Secondly, lack of progress in sustainable con-sumption domain can be ascribed to interests of different stakeholders that lobby against addressing especially consumption levels. More consensual agreement exist in the discussion about the necessity to address consumption patterns – consuming differently, which is in fact just greening the markets. Thirdly, sustainable sumption in it broadest sense may call for renegotiation of the major societal con-ventions and institutions, which is not the easiest thing to do. Lastly, the vision of sustainable consumption poses a need for individual action in changing consump-tion habits and adjusting lifestyles in line with the principles of sustainable devel-opment. This implies not only buying more environmentally sound products and services, but also by applying sufficiency principles.

4 Consumption studies in

different disciplines

The history of consumption and consumerism has its roots in a number of eco-nomic, social, cultural and geopolitical transformations that evolved throughout history. Along with these transformations on the macro level, which were impor-tant pre-requisites for changes in consumption levels, there are a number of factors related to consumer behaviour. Therefore, the consumption phenomenon has been discussed in a number of different scientific disciplines such as economics, sociol-ogy, psycholsociol-ogy, behavioural science, etc. In this chapter, we provide a short over-view of the main theories that are useful in understanding consumption and the need for sustainable consumption.

4.1 The simple model of neo-classical

economics

Neo-classical economic theory is one of the oldest economic theories of consump-tion and dominated scientific debate from the mid-19th century and prevailed well into the 20th century. Neo-classical economics started with William Stanley Jevons' “Theory of Political Economy” (1871), Carl Menger's “Principles of Economics” (1871) and Leon Walras' “Elements of Pure Economics” (1874 – 1877). The theory is based on a number of simplifications and assumptions regarding consumer be-haviour and consumer interaction with the surrounding world (see more modern authors: Friedman 1957; Douglas and Isherwood 1980; Harris 1997; van den Bergh and Ferrer-i-Carboneli 2000).

The traditional microeconomic consumption theory describes how the rational consumer allocates his/her budget amongst different goods in order to maximise private benefit (utility). Generally speaking, neo-classical economics takes the insatiability of consumer desires and the sovereignty of consumer choices as the definite features of consumption without going into the underlying motivations for them. Incomes and prices are treated as one of the main limiting factors and the consumer’s choice is essentially an exercise of finding the optimal condition where the utility/price ratios of the chosen goods are equal (Toumanoff and Farrokh 1994). Another important determinant of consumption is time or rather its alloca-tion between different product and service alternatives (Becker 1965).

The neo-classical theory rests on a number of assumptions. Firstly, is the fun-damental assumption that the consumer is a rational decision-maker with well-defined aspirations for goods and services. Secondly, is the assumption that the desires are insatiable and consumption is determined by the desire to maximise the consumer’s private utility measured in terms of the quantities of products and ser-vices consumed. Utility maximisation is an insatiable desire and consists of a proc-ess of balancing consumption amongst different alternatives available on the mar-ket. The main limiting factors for consumption are budget and time (Lancaster

1971; Michael and Becker 1973). Thirdly, is the assumption that the consumer is sovereign and consumes goods without considering social, ethical or environmental issues, i.e. culture, institutional frameworks, social interactions. Fourthly, is the assumption that consumer preferences and desires for certain goods are by nature stable and that consumers maximise private utility in the world of perfect informa-tion and market competiinforma-tion.

Thus, in this simplistic model, the main prerequisite for consumption, assuming adequate supply of goods and services at market prices, is the availability of in-come and time to consume. Other important factors are personal tastes, but these often fall outside the realm of economics and traditional economists mostly restrict themselves to discussing the role of prices and incomes when determining con-sumption choices.

The level of income depends on the time spent working, qualifications and how well this is applied in producing value-added. Generally, higher incomes are possi-ble along with technological improvements that provide higher productivity and lower production costs and the final prices of goods. Since consumption is directly linked to the available budget, consumers are interested in increasing personal incomes, which is possible by raising productivity, i.e. producing more with fewer production factors (labour, capital, technology or resources). This may lead to over-supply and the resulting price drops and rebound effects that in turn promote consumption and result in higher environmental impacts.

With its set of assumptions, the neo-classical theory is convenient for analysing how price elasticity, incomes and product substitution influence consumer behav-iour. Income elasticity measures the responsiveness of the demanded product quan-tity to income change. If spending on a good does not grow proportionally to in-come, the good can be considered a necessity. On the other hand, if an increase in income induces more than a proportional increase in expenditure, the good can be considered a luxury (Pearce 2000).

Practice shows that wealthy individuals are more likely to consume luxury items and are typically early adopters of a new technology, initially absorbing the high costs of innovation. As soon as the market for the early adopters (usually wealthier consumers) saturates, the manufacturers may choose to lower their profit margins or produce similar, but simpler and cheaper products in order to reach mass consumers (EC IST 2001). As technological improvements are made, the price of new technologies drops and demand increases allowing the suppliers to benefit from the economies of scale. As the production volumes increase, so does the competition, which further presses down the prices making products more

af-fordable. This market mechanism usually helps to move a good from the realm of

luxury to the realm of an affordable common good, which inevitably increases consumption levels.

An affordable good may even evolve into a necessity, which influences con-sumption of other goods. This is especially true when institutional settings and infrastructures surrounding that good change in a way that promotes consumer dependency on the good. For example, in the USA cars were luxury goods until the 1920s. However, as incomes grew, cars became an affordable good and later,

facilitated by governmental strategies for infrastructure development and town planning, cars evolved into an absolute necessity. The increasing availability of cars increased consumer mobility, allowed time saving and access to more shop-ping places. In reality, however, time saving from car use is a relative benefit. With an increasing number of cars, time benefits usually shrink as roads become more clogged with traffic.

Being simplistic (i.e. ignorant to the exogenous factors – society, culture and institutions) the neo-classical economic theory is well-suited for modelling the effects of technological and labour productivity improvements. This theory is also convenient for environmental policy interventions using economic instruments, such as road fees, carbon taxes or any other general pollution surcharge taxes (Kletzan, Köppl et al. 2002). However, it does not hold true in its assumption that increasing levels of material ownership lead to increasing satisfaction with life as, for example, millions of poor people in India consider themselves happy, while the opposite is true for rich people in the USA (see further discussion on this topic in the following section).

4.2 Modern consumption theories

A change in neo-classical economics took place in the mid-1930s with the publica-tions of Joan Robinson’s “The Economics of Imperfect Competition” (1933) and Edward H. Chamberlin’s “The Theory of Monopolistic Competition” (1933), which introduced models of imperfect competition, new theories, such as Herbert Simon's theory of bounded rationality, and new tools, such as the marginal revenue curve. Taking into account the concept of bounded rationality with lack of information and cognitive limitations, it is clear that consumers cannot be efficient in their cho-ices and that neoclassical economics has failed to provide a sufficient explanation of consumption processes. Since then, the neo-classical economic theory has been criticised by many scholars for its over-simplification of reality, particularly on the assumptions of a rational and sovereign consumers with limitless consumption needs (see: Scitovsky 1976; Daly and Cobb 1989; Daly 1996; Bianchi 1998; Sa-muelson and Nordhaus 2004).

According to recent consumption theories, a large part of the factors determin-ing consumption are based on socio-psychological drivers (Røpke 1999a) and other

external macro factors, such as demography, institutions and culture (Gatersleben

and Vlek 1998). Galbraith argued that there are limits to desires and that the ex-pressions of these desires in specific wants are created by a number of external factors, such as industrial, social and political systems. Only physiological needs have limits, while psychological needs are insatiable. The present consumer socie-ties appear to exploit the latter fact and employ a great amount of resources to dis-cover and create an urge for more and more desires (Galbraith 1958).

One of the models describing consumer behaviour that is often implicitly or explicitly used in many modern consumption theories is the so-called

Needs-Opportunities-Abilities (NOA) model. This model explains consumer behaviour as

Figure 4. The NOA model of consumer behaviour. (Source: Gatersleben and Vlek 1998; Gaters leben 2001. )

Motivations are determined by physiological and emotional needs, such as nutri-tion, safety, comfort, positioning in and interaction with society, status, etc. On the other hand, behavioural control factors are those that limit consumer motivations. The most common control factors are financial, temporal, informational, cognitive, physical or special. Opportunities have influence on both motivational and behav-ioural control factors. In this sense, opportunities are important in terms of avail-ability or lack of information, time, money, locations and access, which all deter-mine consumption opportunities. It is also argued that needs, opportunities and abilities are in turn influenced by macro factors, such as technologies, economic systems, demographics, institutional structures, social relationships, customs and cultures (Gatersleben and Vlek 1998; Gatersleben 2001).

A group of theories that attempt to explain the consumer decision-making process comes from the fields of sociology and psychology, which focus on non-economic interpretations of consumerism and consumer behaviour. These theories make a distinction between the needs and wants of private consumers and to a large extent explain consumption patterns as a process of balancing needs and wants. Needs are usually viewed as pertinent to biological or bodily necessities, while wants are not biologically determined, but are acquired by learning. Once they are attained and their ability to give satisfaction has been learned, wants become habit-ual and at a certain level can be perceived as needs. To certain degree, both needs and wants are influenced by psychological factors acquired over individual’s life-time and by social drivers induced by social relationships, norms and culture.

4.2.1 Psychological studies of consumer behaviour

With the exception of besides social psychology, the major part of psychological research studies individual processes. The domain of psychological research on consumer behaviour focuses on identifying and studying the personal human

qualities that influence consumer behaviour. Psychology is concerned with learning how the urge of need is created, how different stimulators influence the personal decision-making process and how the satisfaction sensation is created and con-firmed. It seems that the focus is on four major topics: consumer resources (time, money), motivation, knowledge, attitudes, personality, values and lifestyle. Along-side these, three major processes are being studied by psychologists: information processing, influencing attitudes and behaviour and learning processes (Engel, Blackwell et al. 1995).

Several schools of thought can be distinguished in psychology. Representatives of the operant conditioning view of consumer learning investigate the role of re-wards and punishments in the consumer decision-making process. Behaviourists are concerned with the role that the surrounding conditions have on learning and the decision-making process. Behaviourists that support a classical conditioning view study how consumers respond to brand names, scents, colour and other stim-uli when making purchasing decisions based on knowledge they have gained over time. On the other hand, cognitive learning theorists are concerned with studying internal brain processes.

Psychological studies analyse the influence of the emotional state of consumers

on purchasing decisions (see, for example Gardner 1985). Psychological processes

such as attention, comprehension, memory and cognitive and behavioural theories of learning, persuasion and behaviour modification constitute an integral part of marketing studies on consumer behaviour. The need for social appreciation and status discussed previously are well grounded in the psychological theory of Mas-low (1954), who postulates that human behaviour could be explained by the uni-versal motivation to satisfy a hierarchy of needs (Figure 5) and that self-realisation and social acceptance are as important as the basic needs of food and shelter (Maslow 1954).