HSS-15, SIRA/SPARC, Kalmar, 28-29 May

Norms and Ethics: Prerequisites for Excellence in Co-production

Ulrika Florin*, Erik Lindhult, Academy of Innovation, Design and Engineering, Mälardalen University• Corresponding author, mail: ulrika.florin@mdh.se

Abstract

Knowledge production is increasingly made in broader Mode 2 (Gibbons, 1994) networks of stakeholders and contributing actors, e.g. in the form of participatory, interactive and action research. Historically this has always been an important part of scientific and academic activity, particularly important in certain scientific fields of research, e.g. engineering, business administration, organization and working life research, pedagogics and social work studies, as well in methodological traditions like action research and participatory research (Reason & Bradbury, 2008). When roles in knowledge production are more interconnected traditional research ethics focused on ethical treatments of research objects when they also are subjects (e.g. information, consent, and confidentiality) need to be significantly supplemented. When knowledge is seen as co-produced in interaction between equal parties with different contributions to the process and knowledge interest, this creates the need for recognition and guidance of special norms and ethical codes as prerequisites for excellent practice. This paper is aiming to explore and discuss norms of excellence and ethical concerns in co-production between academia and enterprises and how collaboration could be organized to increase both validity and utility of the knowledge created in such settings. All parties in such collaborative setting have the responsibility to generate practical agreements as to form the ground for a beneficial co-production, however this includes rules for securing non-violation of rights, like confidentiality and intellectual property. The parties share responsibility in review and control of quality of processes and results in relation to these agreements, although it differs in what matters are considered important to address in academic traditions and enterprises cultures.

The purpose of this paper is to develop an extended set of norms and ethical principles for co-production oriented research. The main focus is relational dimension between involved parties instead of how one party (the researcher) treats other affected parties. We have therefore developed a list of norms with clarification and argument as a basis for their use. Examples are: acknowledgement and respect should be given to different forms of knowledge, theoretical and practical, explicit and formal as well as implicit and tacit; care should be taken to provide space for expression of different perspectives of involved parties in order to secure validation and useful results. Open discussion on equal terms; democratic dialogue, is a core medium for good co-productive relations, different knowledge needs and interests of involved and concerned parties, practical as well as scientific; to the co-production should be considered in the aims and procedures, and that the parties have a mutual responsibility to develop sufficient understanding of the needs and interests of others. The proposed norms developed in this paper can be considered as a tool or a guideline for the development of ethical and excellence in co-produced research.

Introduction

In Mälardalen University´s research and educational strategy for 2013-2016 it is stated: “Mälardalen University (MDH) will, in 2016, be the leading higher education institute (HEI) in Sweden for excellent coproduction with different actors in society, both internationally and nationally”.1 However,

excellence might not necessarily be understood in the same way by different stakeholders in a collaborative project. One aspect of concern is how to establish a common ground for all involved, with a sustaining ethical approach that cares for all involved and affected by a project. This regarding all phases: the development of a project, forthcoming activities within a project and in reflecting on the outcome of a project i.e. what consequences for society there might be.

The authors of this paper have personal experience of research in collaborative settings with different participants and learned what possibilities and obstacles might occur in such research projects. (Florin 2012, 2013, 2015, Lindhult 2005, 2015) Together they have a broad experience from a wide range of projects that includes stakeholders from industry, governmental authorities, freelancing artists and academy.

This specific paper originates from an explorative research seminar on the topic Ethics in Collaborative Settings (hereafter referred to as the ECS- seminar) that was held at Innovation and product realization (IPR) at Mälardalen University in 2014. IPR is a multidisciplinary and practice-oriented research milieu that produces research in collaboration with industry and organizations. This particular seminar started with a general talk on ethical dilemmas in co-production.2 The idea was to reflect on and

identify ethical dilemmas occurring in research projects with participants from different knowledge horizons. The discussion was lively and the need of a think frame or guideline was clearly stated. Particularly discussed were challenges such as: agreements, ownership of material and results, how to inform participants, trustworthiness, mutual responsibility, and professionalism, both within ongoing projects and in relation to applications for funding of new projects.3

Understanding knowledge production

Knowledge production is increasingly made in broader Mode 2 (Gibbons, 1994) networks of stakeholders and contributing actors, e.g. in the form of participatory, interactive and action research.4 Historically this has always been an important part of scientific and academic activity,

particularly important in certain scientific fields of research, e.g. engineering, business

administration, organization and working life research, pedagogics and social work studies, as well in methodological traditions like action research and participatory research (Reason & Bradbury, 2008). When roles in knowledge production are more interconnected traditional research ethics focused on ethical treatments of research objects when they also are subjects (e.g. information, consent, and confidentiality) need to be significantly supplemented. When knowledge is seen as co-produced in interaction between equal parties with different contributions to the process and knowledge interest, this creates the need for recognition and guidance of special norms and ethical codes as prerequisites for excellent practice. This paper is aiming to explore and discuss norms of excellence

1 Mälardalen University’s Research and Education Strategy for 2013-2016

2 The talk was held by Associate Professor Niclas Månsson, chairperson of Mälardalen University Advisory Ethics Committee together with

Ulrika Florin (committee member) that initiated the discussion session afterword.

3 The participants in the seminar gave their consent to use the groups’ notes from the discussion as a starting point to further investigate

ethics and norms in collaborative settings.

4 Gibbons Mode 2, is a concept that refers to knowledge production that takes place in more interactive modes, the concept also focuses on

and ethical concerns in co-production between academia and enterprises and how collaboration could be organized to increase both validity and utility of the knowledge created in such settings.

Norms and ethics in collaborative research

In co-produced research, the traditional ethical issues emanating from the power of researchers to institute morally relevant effects on people part of the research domain is shifted towards how interaction and collaboration among involved parties considered to have, and should have, more equal standing are to be normatively regulated. It is a matter of virtues and common norms of excellence in research as a praxis constituted by community of practitioners in different roles and relations.

The theories used in this investigation draw on a contemporary understanding of Aristotle's analysis of different aspects of knowledge and practice (Aristotle, 1980, Nussbaum, 1986, 1990, 1995), pragmatic theory of inquiry (Dewey, 1939), communicative ethics (Benhabib & Dallmayr, 1990) as well as democratic perspectives on knowledge and practice development (Toulmin & Gustavsen, 1996, Lindhult, forthcoming). The core of this understanding of knowledge and inquiry is that it emphasizes the combination of capabilities of thinking ethically and considering actions that can deliver desired effects in terms of valued outcomes.

Each party in a collaborative project often represents different communities of practice. (Lave and Wenger, 1991) Building a combined community of practice of a more or less temporary or permanent character is a challenge. The question is how norms can be defined that work cross boundaries and are experienced as equally meaningful, and therefore useful? One theoretical starting point in addressing this matter is the philosopher Martha Nussbaum’s formulation, based on Aristotle: “ethical understanding [that] involves emotions as well as intellectual activity and gives a certain type of priority to the perception of particular people and situations, rather than to abstract rules” (Nussbaum, 1991). Nussbaum is pinpointing a kind of "navigational" knowledge that relates to the best choice for the particular situation. A skill that sometimes is discussed as a non-verbal enterprise, tacit (Polanyi, 1966). Tacit knowing can be defined as knowing demonstrated not in words or signs but in action. This implicit level is interconnected in all sorts of practices, and is also significant in researchers’ praxis. It also opens up for recognition of different forms of knowing in co-productive inquiry.

To further develop an extended set of norms and ethical principles for co-production oriented research, which is this aim of this paper, we first have to distinguish what differences and collisions of interests there might be between different communities of practice (cultures), for instance between representatives from an industrial company and members of a research group. Roughly, one fundamental difference is that the primary purpose for academia is to produce knowledge recognized as valid and as a contribution to existing scientific learning, while most enterprises goals are to solve specific problems and to produce shareholder value. Together the parties are expected to produce new knowledge beneficial for both sides, and at the same time valuable for society as a whole since society initially invested in this co- production through funding-programmes. Concerning the funding matter, the ECS- seminar stressed the risks involved in formulating research project applications based on the calls. But obviously, to some extent one must do so otherwise you may not get funding for a project developed in the context of a Mode 2 governance with a focus on producing valued outcomes for both academic, industry and community parties. Consequently, the norms and ethics must cover also early planning phases with agreement and negotiations based on appropriate rules of interaction of involved parties

In the field of action research there has been research to develop ethics from a focus on researcher´s care for people involved in the research domain in a study to a collaboration oriented ethics (Zeni, 1998, Brydon-Miller, Greenwood & Eikeland, 2006, Hilsen, 2006, Brydon-Miller, 2008, Locke, Alcorn & John O’Neill, 2013, Nielsen, 2014, Holian & Coghlan, 2013, Brydon-Miller, Aranda & Stevens, 2015). We draw on this literature. E.g. Brydon-Miller et al. (2003: 15) argues that basic values, which underlie common practice of action researchers, are ” respect for people and for the knowledge and experience they bring to the research process, a belief in the ability of democratic processes to achieve positive social change, and a commitment to action”.

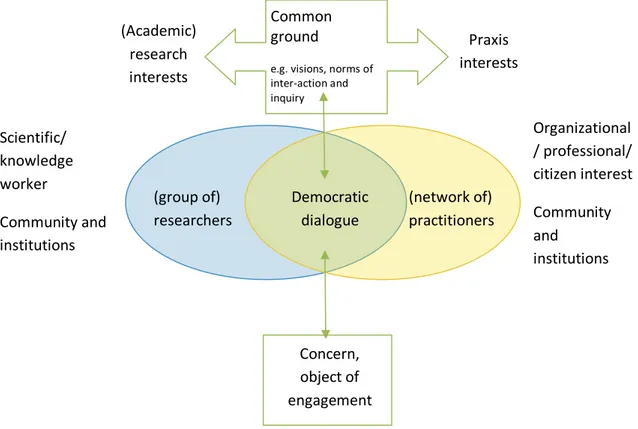

Figure 1. below is an inquiry model from the field of collaborative research (action research/interactive research), focusing on the relational dimensions of research, which is of core importance in understanding the character of norms and ethics in co-production.

Figure 1. Relational model of collaborative inquiry in co-production (Lindhult, 2005, Greenwood

& Levin, 1999)

A point of departure of collaborative, co-productive inquiry is that there are different parties involved with different aims in what are considered valued outcomes of an inquiry. In figure 1. the two core actor categories involved in the inquiry are depicted as researchers, with a focus on knowledge outcomes generally aiming to fulfill academic standards of process and results, and practitioners, with a focus on practical outcomes in terms of solution to problems and improvement of practice. These actors are generally embedded in different organizational settings and communities of practice with different standards of excellence.

democratic dialogue Common ground e.g. visions, norms of inter-action and inquiry

praxis interests (group of) researchers (network of) practitioners Concern, object of engagement (academic) research interests organizational/ professional/ citizen interest community and institutions scientific/ knowledge worker community and institutions

In order to establish a basis for collaborative inquiry where co-production can take place, a common ground of values, visions and norms of interaction and inquiry needs to be developed. The practical agreements generated to serve as a common ground are a negotiated accomplishment which form a basis for mutual value of efforts. The parties need to creatively combine their concerns and different engagements in the focus and process of inquiry so that mutually beneficial learning is produced. As the processes of inquiry is assumed to be between autonomous agents with as far as possible equal standing, democratic dialogue is important to legitimize agreements as well as to ensure that the voice and contribution of all is mobilized and utilized in the undertaking. In an actual situation, there are influences of power and status differences which restrain legitimation and the sharing of knowledge and capacities. But a sufficient degree of openness and equality in discussion can provide a normative basis that can be further developed over time. Norms and ethics enter into the picture in how parties are interacting and how a common ground between them is built and maintained. The different practices and businesses in which parties are situated and the communities in which they are part influences the demands and requirements of achievements of the collaboration as well as their conditions and capacities to participate. One important dimension in the model is the character of norms of interaction that can be generally considered as possible choices as part of a common ground in each collaborative inquiry project or constellation. Here ethics and norms of co-production play an important validating and trust generating function to ascertain the viability of the common inquiry efforts.

Figure 2. An updated understanding, modified model elaborated out of the relational model of

collaborative inquiry in co-production (Lindhult, 2005, Greenwood & Levin, 1999).

A core aspect of collaborative inquiry and co-production is the overlapping and intersection of roles in inquiry and knowledge creation, where e.g. users and practitioners are not only recipients of results but have important roles and responsibilities during the whole process. Furthermore, the relational

Democratic dialogue Common ground

e.g. visions, norms of inter-action and inquiry Praxis interests (group of) researchers (network of) practitioners Concern, object of engagement (Academic) research interests Organizational / professional/ citizen interest Community and institutions Scientific/ knowledge worker Community and institutions

area is a common area of exchange, interactive learning and co-laboration where there is common responsibility for building such communicative space for democratic dialogue. The democratic dialogue is literally given space (rather than being understood as a tool or a link between the parties) in the elaborated version of the model (fig. 2). Democratic dialog is highlighted as fundamental for exploring and developing throughout the whole project.

Proposal for norms of excellence of collaborative, co-productive research

As we have seen, building a common ground of vision and norms of collaboration is important in different forms of collaborative research, where a focus is co-production. This has to be considered in each project or collaborative constellation, but it is possible to formulate some general norms that can function as meta-rules or generative principles supporting the development of suitable rules for research practice in each context and case. For instance, as a general guideline co-production needs to produce valued outcomes for all parties, but the particular constellation and specification of outcomes need to be determined in each inquiry enterprise.Norms of excellence involve both constitutive features and identity of praxis, successful performance of praxis as well as fair treatment of parties to it. The constitutive dimensions means that norms have a self-evidential character for experienced participants and is seen as close to defining the identity of praxis. The praxis would not be the same practice without it. E.g. any inquiry requires a sufficient degree of openness and equal standing of parties in order to qualify as collaborative inquiry. Many norms are also clarifying success as well as ideals of practice, providing direction for more effective and efficient inquiry praxis. E.g. the democratic character of communication in inquiry may be seen as an ideal, which enhances effectiveness in mobilizing different forms of knowledge of involved parties. Although its a challenge to efficiency in the short run, in the long run it may be more efficient in producing valued outcomes.

A third function is the more ethical aspect of fair treatment, in this case particularly others as more equal participants and partners, or potential participants in the collaborative inquiry and co-production. As participants achieve more equal standing the norms also are defining shared responsibilities of the joint undertaking. In this more collaborative and democratic context of inquiry, all share responsibility for maintaining traditional research ethics, e.g. confidentiality and avoiding harm of those involved in the empirical domain of research.

Freedom in inquiry

- Care should be taken to provide space for expression of different perspectives of involved parties in order to secure validation and useful results.

An important feature of inquiry is freedom. Traditionally this has been expressed as academic freedom to pursue inquiry by researchers as they see fit, something going back to Plato´s dialectics and Socratic questioning through dialogue. Freedom is assumed to be necessary for high quality knowledge in order to defy traditional understandings often backed by established powers and vested interests or just institutionalized in traditions and ingrained perceptions of normality. In collaborative inquiry it gains a wider meaning as freedom in inquiry for all involved parties, where the role of a co-producing academia becomes a guardian of such broader freedom of inquiry.

Norms of freedom also lead to opportunities for empowerment of different actors and is also a source of power requiring responsibility in its exercise. Without such broader conceptions of freedom,

traditional academic freedom risks becoming a power in relation to other actors right to the same freedom in co-productive inquiry. With a broader conception of freedom, inquiry practices can support e.g. users or involved parties to express and analyze their experience and feed this input into inquiry processes.

Dialogic and democratic inquiry

- Open discussion on equal terms, democratic dialogue, is a core medium for good co-productive relations. This a shared responsibility, requiring resources and development in the course of the co-productive work.

The quality of relations between involved and concerned parties in inquiry is a core feature in many ways. This implies that open dialogue on equal terms among parties involved is a core practice for collaboration and participation of concerned parties. Discussion is seen both as a medium for broad participation, for interaction between organizational units, and for knowledge formation. The creation of fora in which democratic dialogues can emerge and be instrumental in furthering participatory innovation is crucial.

Gustavsen has formulated a vision of good communication, as operational directives (Dewey, 1939) for practices of democratic dialogue that can be used to assess and shape of actual communicative fora and practices. The following criterias for democratic dialogue is a point of departure and provides guidelines for communicative and assembly design in the dialogue-democratic approach (Gustavsen, 1992:3-4). The dialogue is a process of exchange: ideas and arguments move to and fro between the participants: 1) It must be possible for all concerned to participate. 2) This possibility for participation is however, not enough. Everybody should also be active. Consequently, each participant has an obligation not only to put forth his or her own ideas but also to help others to contribute their ideas. 3) All participants are equal. 4) Work experience is the basis for participation. This is the only type of experience that, by definition, all participants have. 5) At least some of the experience that each participant has when entering the dialogue must be considered legitimate. 6) It must be possible for everybody to develop an understanding of the issues at stake. 7) All arguments that pertain to the issues under discussion are legitimate. No argument should be rejected on the grounds that it emerges from an illegitimate source. 8) The points, arguments, etc. which are to enter the dialogue must be made by a participating actor. Nobody can participate "on paper" only. 9) Each participant should be able to tolerate an increasing degree of difference of opinion. 10) The work role, authority, etc. of all participants can be made subject to discussion - no participant is exempt in this respect. 11) The participants should be able to tolerate an increasing degree of difference of opinion.12) The dialogue must continuously produce agreements that can provide platforms for practical action.

Shared value of inquiry

- Different knowledge needs and interests of involved and concerned parties, practical as well as scientific, to the co-production should be considered in the aims and procedures. The parties have a mutual responsibility to develop sufficient understanding of the needs and interests of others.

Different parties have different knowledge interests and needs. A constitutive feature of co-productive, collaborative inquiry is that it should create value and benefits for different parties. In order for inquiry to care for and produce shared value, each party not only needs to clarify their own needs and interests but also develop an understanding of the needs and interests of others and support their expression and realization.

Governance of inquiry

- Each party needs to have a fair say in the decision on aims and organizing of co-production.

Traditionally scientific inquiry is generally controlled by researchers assumed to have the requisite expertise to do so over and above other parties. In collaborative inquire the different expertise of parties should be acknowledged and used as and when appropriate. Shared responsibility for governance of inquiry is also based on an aim of democratization of research, its focus on problems as well as its benefits for different stakeholders. It is in line with a discourse ethics emphasizing that validity is based on agreement among concerned parties (Habermas, 1990). The use of each source of expertise in the inquiry needs to be dialogically and democratically legitimized in order to avoid elements of technocracy.

Extended epistemology and capacity in inquiry

- Acknowledgement and respect should be given to different forms of knowledge, theoretical and practical, explicit and formal as well as implicit and tacit, among participants.

A core feature of collaborative, co-productive inquiry is that each party has something to learn and something to contribute. It implies that the different forms of knowing and knowledge that different parties bring to the collaboration need to be acknowledged, legitimized and respected. This also is a source of enhanced quality in this type of research.

Self-reflection

- The parties share responsibility for critical self-reflection in order to raise awareness of personal, common or structural presuppositions in inquiry and their consequences and creatively construct conditions for free and shared inquiry.

Collaborative inquiries, in order to establish and maintain their character of free and shared inquiry need to continuously exercise critical reflection on unacknowledged assumptions. Systematic self-reflection is useful throughout the project, also in early planning phases to enhance knowledge creation. As there are always sources of power from ingrained ways of thinking and doing, critical self-reflection is necessary to try to unveil and be as transparent and self-reflexive as possible on these assumptions.

Thus learning and attaining new knowledge is an emancipatory exercise. It is a core in the motto that Kant saw in Enlightenment: Sapere aude! – dare to be wise, have courage to think for yourself. In learning made collaboratively people are able to develop their Mündigkeit, that is autonomy and

Common ground of inquiry

- All parties have a responsibility in generating practical agreements as common ground for co-production, including rules for securing non-violation of rights, like confidentiality and intellectual property, of all parties. The parties share responsibility in review and control of quality of process and results in relation to agreements.

A point of departure is diversity of capacities and interest among parties, which is both a resource and a challenge. In order to attain collaboration in inquiry, different parties involved need to continuously build and maintain a common ground of visions, values and norms of the combined community of practice of inquiry with more or less temporary or permanent character. There is a more or less extensive ground on which collaborative inquiry is based in order to be viable. In a constellation of parties in inquiry, such values and visions can function as a point of departure for building a common ground adapted to the situation. In a collaborative constellation of inquiry what is needed is in particular a generation of practical agreements as a platform for joint inquiry.

Quality of inquiry

- Co-production should be organized so as to increase qualities (validity and value) of knowledge created conducive for concerned parties

Achieving excellence in coproduction and collaborative inquiry require a focus on quality. One dimension of co-productive research is that the distinction between producers and users of research in organization is less pronounced. High quality knowledge production is fused with high utility in knowledge dissemination, and is done through integrated activities.

The traditional distinction between basic research “free” from consideration of value and utility, and applied research and development work is less applicable as collaborative inquiry involves interests related to all these traditional phases. In bringing different expertise to the inquiry as well as participating in its governance all parties share a responsibility in creating valid and valuable inquiry. As all are active in different parts of the process, quality is co-created and balances and priorities need to be made between different quality dimensions by involved parties.

Shared responsibility for viable and efficient inquiry

-The parties in co-production share responsibility for providing and using appropriate resources and efficient methodology for achieving success in co-productive work.

One challenge in pursuing collaborative inquiry and co-productive research is its greater complexity in collaboration and social relations. Attention needs to be given by all parties to the inquiry in terms of resources, particularly commitment, time and space (economic and social). The most common source of failure is the limited attention and care of some (or all) parties for the inquiry, leading to a loss of efficiency, legitimacy and eventual termination.

Concluding remarks

In this paper we have developed suggestions for ethics and norms of excellence in collaborative, co-productive inquiry.

In moving from Mode 1 to Mode 2 knowledge production systems, the normative orientation of inquiry needs to be a common accomplishment of participating actors. We believe a viable system of inquiry

for co-production require appropriate ethics in its practical implementation in different projects and collaborative constellation, in supplement to traditional research ethics.

Our proposal for guidelines is an effort to clarify the character of a norm system for co-production, which should be useful to consider at Mälardalen University and other academic institutions with a strategic orientation to co-productive research and learning, leading the way towards the future of universities (Greenwood & Levin, 2006).

The proposal is at this stage tentative and open for further discussion. Its usefulness can only show itself in further discussion as well as in use of the guidelines, in Mode 2 oriented communities of inquiry among researchers as well as practitioners and other interested parties.

References

Aristotle (1980). The Nicomachean Ethics. Oxford: Oxford U. P.

Aristoteles, (1967, 2012) Den nikomachiska etiken, översättning Mårten Ringbom, Daidalos förlag, tredje upplagan.

Benhabib, S. & Dallmayr, F. (eds.) (1990). The Communicative Ethics Controversy. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press.

Brydon-Miller, M. (2008). Ethics and action research: deepening our commitment to principles of social

justice and redefining systems of democratic practice. In: Reason P, Bradbury H (eds) The SAGE

handbook of action research: participatory inquiry and practice, 2nd edn. London: Sage.

Brydon-Miller, M., Greenwood, D. & Eikeland, O. (2006). Conclusion: Strategies for addressing ethical

concerns in action research. Action Research, 4(1): 129–131.

Brydon-Miller, M., Greenwood, D. & Maguire, P. (2003) Why action research? Action Research, 1(1): 9-28.

Brydon-Miller, M., Aranda, A.R. & Stevens, D.M. (2015) Widening the Circle: Ethical Reflection in Action

Research and the Practice of Structured Ethical Reflection. In: Bradbury, H. (ed) The SAGE handbook

of action research, 3rd edn. London: Sage.

Dewey, J. (1939). Logic: The theory of inquiry. London: George Allen& Unwin Ltd.

Florin, U (2015). Konstnärskap i samspel: om skapande arbetsprocesser I myndighetsledda

samverkasprojekt, (English title: Artists in interaction: creation processes in official collaborative

projects), Doctoral dissertation, Mälardalen University Press Dissertations, No. 179.

Florin U ., ErikssonY ., Orre I. (2012) Designing a model of the unknown: Artistic impact in a chain of

skilled decisions, International Design Conferens, Design2012, Croatia, in Proceedings: Sociotechnical

Issues in Design, vol. 3

Florin U., Orre I., Eriksson Y. (2013) Collaboration for the Improvement of Tolerance: Artistic Practice

in a S ocietal Context , The International Journal of Social, Political and Community Agendas in The

Arts, accepted 2013 in press 2015.

Gibbons, M. et.al. (1994). The New Production of Knowledge. London: Sage.

Greenwood, D. & Levin, M. (1998). Introduction to action research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Greenwood, D. & Levin, M. (2006). The Future of Universities: Action Research and the

Transformation of Higher Education. In: Reason P, Bradbury H (eds) The SAGE handbook of action

research: participatory inquiry and practice, 2nd edn. London: Sage.

Habermas, J 1990, Discourse Ethics: Notes on philosophical justification. In Benhabib & Dallmayr (eds) 1990.

Hilsen A-I (2006) And they shall be known by their deeds: Ethics and politics in action research. Action Research, 4:23–36.

Holian, R. & Coghlan, D. (2013). Ethical Issues and Role Duality in Insider Action Research: Challenges

Lave J. & Wenger E. (1991/2011). Situated Learning: Legitimate peripheral participation, Cambridge University Press, New York.

Lindhult, E. (2005). Management by Freedom: Essays in moving from Machiavellian to Rousseauian

approaches to innovation and inquiry, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm.

Lindhult, E. (2008). Att bedöma och uppnå kvalitet i interaktiv forskning, Johannisson, B., Gunnarsson, E. & Stjernberg, T., red., Gemensamt kunskapande – den interaktiva forskningens praktik. Växjö: Växjö University Press.

Lindhult, E. (2015). Towards Democratic Scientific Inquiry? Participatory democracy, philosophy of

science and the future of action research, in Gunnarsson, E., Hansen, H.P. & Steen Nielsen, B. Eds.

Action Research for Democracy – Intervening in the current Crisis: New Ideas and Perspectives from Scandinavia. Routledge.

Lindhult, E. (2015). Building interactive learning ground as basis for knowledge co-production: Reflection on a collaborative action research project. 59th ISSS Conference, Berlin, Germany, Aug. 2-7, 2015. Locke, T., Alcorn, N. & John O’Neill, J. (2013). Ethical issues in collaborative action research, Educational Action Research, 21(1):107-123.

Nielsen, R.P. (2014). Action Research As an Ethics Praxis Method. Journal of Business Ethics, DOI 10.1007/s10551-014-2482-3.

Nussbaum M. C. (1986). The Fragility of Goodness: Luck and Ethics in Greek Tragedy and Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nussbaum M. C., (1990). Loves Knowledge: Essays on Philosophy and Literature. New York: Oxford University Press.

Nussbaum M. C. (1995). Känslans skärpa tankens inlevelse: Essäer om etik och politik. Stockholm: Brutus Östlings Bokförlag Symposium.

Polanyi, M., 1966, The Tacit Dimension. Doubleday and Company, INC, New York.

Reason, P. & Bradbury, H. (eds.) (2008). The SAGE Handbook of Action Research. London: Sage. Toulmin, S. & Gustavsen, B. (eds.) (1996). Beyond theory: Changing organizations through participation. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publ.