Food as a factor to ensure organization’s internal

sustainability

A study of Swedish employees’ perceptions and expectations

regarding food at work

Irene ATANCE & Merve KANDEMIR

Faculty of Culture and Society – Department of Urban Studies Main field of study – Leadership and Organization

Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organization

Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organization for Sustainability (OL646E), 15 credits Spring 2020

Acknowledgments

On the basis of this foreword we, Irene Atance and Merve Kandemir, would like to give some attention to the people that helped us to finish this study. In turbulent times due to the outbreak of the COVID-19, we have been able to create this thesis at Malmö University and we are very grateful for that. We want to acknowledge and show gratitude to our thesis supervisor Jonas Lundsten, who guided and assisted us through this whole process. Other than that, we would like to thank all the participants of the interviews in our research, the other members of our seminar group, and everyone else who has directly or indirectly contributed to the outcome of this study. Additionally, a special mention to our respective partners and families for supporting us during the writing process.

Abstract

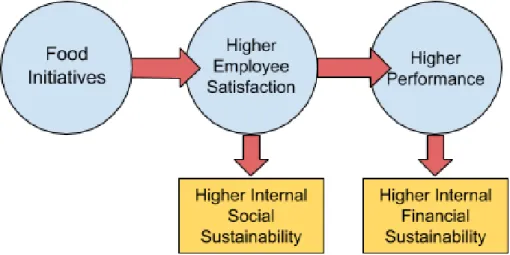

The integration of food in the organization’s culture is a new approach and raising strategy among global companies to enhance employees’ well-being and satisfaction, and thus ensure organization’s internal social and financial sustainability. In this context, the purpose of this research was to explore the connection between food and organizational culture throughout employees’ perception and expectation of food at work. Thus, a qualitative study had been conducted and empirical data had been collected through semi-structured interviews with professionals working in medium/large-sized and public/private organizations based in Sweden. Additionally, a theoretical framework that consists of Schein’s Multi-Layered Organizational Culture Model, Competing Values Framework and Sustainable Well-being Productivity Synergy had been developed to analyze and interpret the collected empirical data. As a result, six main themes emerged from the collected data: 1) Organizational structure around food; 2) Food within the Organization’s environment; 3) Food options within the organization; 4) Dynamics around food within the organization; 5) Influence duality within the organization; 6) Organization’s culture and food. The first mayor finding was that there are evidences extracted from the interviews that connect food to the Swedish organization’s culture. The second finding demonstrated that Swedish organizations assessed, incentive employees through food initiatives such as providing breakfast, coffee breaks or nutritious and healthy food to the employees. The last main finding was that food-related influence duality exists between organizations and employees, and Swedish culture and organizations. Thus, food was found relevant at the workplace in different levels for most of the people interviewed for this study. The findings demonstrated, through employees’ perceptions and expectations, that food strategies appear relevant for satisfying employees, strengthening internal culture and ensuring internal social and financial sustainability.

Key words: organization’s culture, employee satisfaction, employee retention, employee well-being, food strategies, internal social sustainability, internal financial sustainability.

Table of Content

1. Introduction ...1

1.1 Background ...1

1.1.1 Integration of Food in the Organization’s Culture in Sweden ...3

1.2 Research Problem ...3

1.3 Research Purpose ...4

1.4 Research Question...4

2. Theoretical Framework ...5

2.1 Concepts of Organizational Culture ...5

2.1.1 Schein’s Multi-Layered Organizational Culture Model ...5

2.1.2 Organizational Culture Creation and Maintenance ...6

2.2 The Competing Values Framework ...7

2.3 Sustainable Well-being Productivity Synergy ...8

3. Methodology and Methods ...10

3.1 Research Approach ...10

3.2 Research Design ...10

3.3 Study Population ...11

3.4 Methods of Data Collection ...12

3.4.1 Interview Guide...12

3.5 Method of Data Analysis ...13

3.6 Reliability ...13

3.7 Validity...14

3.8 Ethical Considerations ...14

4. Results ...15

4.1 Organizational Structure Around Food ...15

4.2 Food Within the Swedish Organization’s Environment ...17

4.3 Available Food Options ...19

4.4 Social Dynamics Around Food ...20

4.5 Influence Dynamics Within the Organization ...21

4.6 Organization’s Culture and Food ...22

5. Analysis ...24

5.1 Food within Swedish Organization’s Culture ...24

5.2 Implication of Food in the Family/Clan Culture ...26

5.3 Implication of Food in the Organization’s Sustainability ...27

6. Discussion ...28

7. Conclusion ...31

9. Recommendations ...32

10. Personal Reflections ...32

Reference List ... i

Appendix ... vii

A. Interview Consent Form ... vii

B. Interview Guide: Semi-Structured interview ... viii

C. Encryption of participants ... ix

D. Summary of interviews by codes and themes ...x

E. Preliminary literature searches ... xi

Figures List

Figure 1. Schein’s Multi-Layered Organizational Culture Model (2010). ...5Figure 2. Description of the culture archetypes within the CVF for Organizational Culture. Adapted from Cameron and Quinn (Scammon et al., 2014). ...8

Figure 3. Four basic interactions between well-being and performance at work (Ayala, Lorente, Piero & Tordera, p. 11, 2014. ...9

Figure 4. Logic model of the qualitative research. ...11

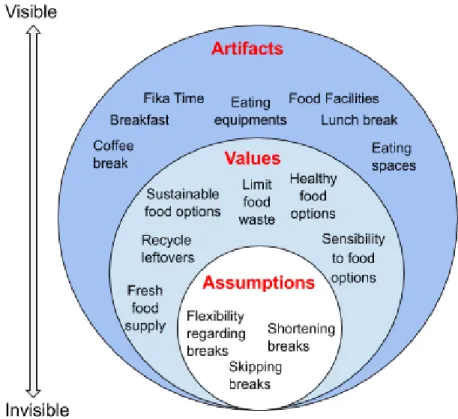

Figure 5. Classification of Food-related elements found within Swedish organizations according to Schein’s Multi-Layered Organizational Culture Model. ...25

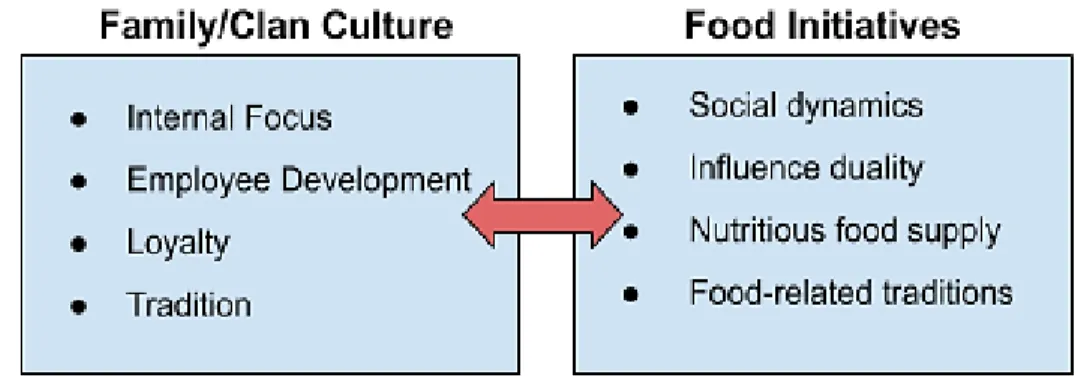

Figure 6. Illustration of Clan Culture development through Food initiatives. ...26

Figure 7. Illustration of the SWPS model through Food initiatives...27

Tables List

Table 1. Summary of the selected sample. ...11Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for literature searches. ...12

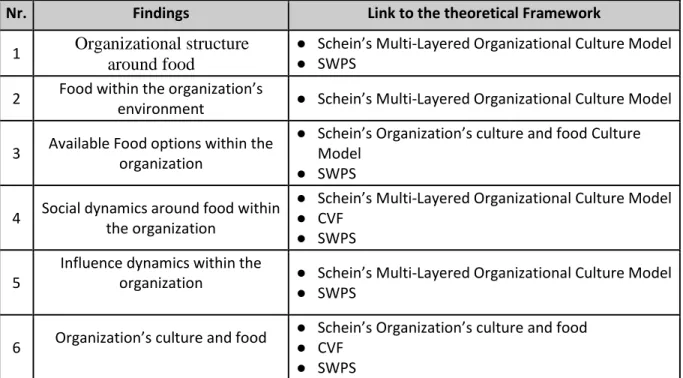

Table 3. Themes of collected interview data. ...15

Table 4. Code encryption of interviews and participants. ...15

Abbreviations List

COVID-19 Coronavirus disease 2019

UN United Nations

UN DESA United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs SDG Sustainable Development Goals

CSR Corporate Social Responsibility

HR Human Resource

WHO World Health Organization

OECD Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development NGO Non-Governmental Organization

CVF Competing Value Framework

SWPS Sustainable Well-being Performance Synergy

RQ Research Question

EU European Union

1

1. Introduction

This chapter outlines the corporate strategy that consists of strengthening organizational culture by fostering food initiatives that intent to impact employees’ well-being, engagement and satisfaction (cf Ogohi & Cross, 2020). In particular, it focuses on a new approach that improves organization’s performance as well as the internal financial and social sustainability by uncovering food as a new consideration of the organization’s culture. Additionally, the research problem, the aim of this thesis, and the research question and sub-questions will be respectively identified.

1.1 Background

Internal corporate sustainability has gained importance over the years and became one of the major organizational challenges globally (UN DESA, 2019). In 2015, during the United Nations’(UN) Sustainable Development Summit in New York, 192-Member states committed to start a global sustainability transformation by defining the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its respective seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (United Nations, 2019). In response to these sustainability global commitments, organizations from all industries have been developing corporate social responsibility (CSR) strategies and increasingly integrating sustainability principles into their missions, visions and core businesses (cf Hristov & Chirico, 2019).

One of the factors that directly affects internal organization’s sustainability is employees’ well-being and satisfaction (Chung & Yazdanifard, 2014), which is linked to SDG 3 for ensuring “good health and well-being” and other related goals such as SDG 8 for “providing good working conditions”, both connected to employees’ well-being and social sustainability (United Nations, 2015). In this context, organizations are a key stakeholder in the achievement of these SDG’s, balancing business growth and sustainability. Thus, organizations must strengthen their strategies in order to enhance employees productivity while maintaining employees’ well-being, satisfaction, and retain talent (Pandita & Ray, 2018). However, many organizations are still struggling to address Sustainable Human Resource (HR) challenges such as increasing stress exposure, expanding office-hours, raising employee turnover and absenteeism, decreasing employee loyalty or low motivation levels among employees (cf Ehnert, Harry & Zink, 2014). Hence, promoting good health, well-being and creating better working conditions, and understanding the importance of social sustainability (Gazzola & Mella, 2017) has become an organization’s internal policy challenge (cf Ogohi & Cross, 2019).

In this context, recent data from WHO (2019) revealed that the average rate of absenteeism from work due to illness in Europe is 11,8 days per employee per year (WHO, 2019). High employee absence or turnover may affect organization’s revenue, as employing or training new people require resources that are costly (O’Connell & Kung, 2007). Additionally, work-related illnesses may affect the society by creating, for example, social inequalities (Lundberg, Hemmingson & Hogstedt, 2007). Thus, global SDGs commitments, as well as financial and competitive interests, are pushing organizations to find new pathways to improve employees’ well-being and overcome satisfaction challenges at the workplace that affect both the internal financial and social sustainability.

For many years, the traditional approach to manage organizations and employees was mainly based on rational arguments, rules, procedures, formal authority structures or organization’s hierarchy (Brown, 1992). Nowadays, the modern approach to manage employees utilizes the organization’s culture as a powerful element that improves organization’s performance and internal social and financial sustainability (Brown, 1992). In this context, organization’s culture is defined as the basic assumptions, values, beliefs or visible artifacts that are incorporated into the organization’s actions (Godwyn & Gittell, 2012).

2 However, there is still no consensus regarding what components of the organization’s culture are key for sustainability, scholars found essential the adoption of a sustainability-oriented culture.

Furthermore, ecological system theories describe that the environment where an individual interacts influences its eating behavior (Bronfenbrenner, 1992). Therefore, the organization might influence, at certain extent, employees’ eating habits through their food availability, established food norms, eating facilities or other types of food initiatives that might also result in the creation and the reinforcement of organization’s identity and values through food. At the same time, individual food preferences might also influence the food choices that are offered by the organization. One of the most recent examples in how employees might influence the food culture is the increasing demand of vegan food or allergy sensitive foods. These phenomena are also known as the structural duality: the organization’s structure shapes people and vice versa (cf Tolbert & Hall, 2009).

Since ancient times, food has defined culture (Shah, 2018) until this date. Therefore, food is considered as a key element of people’s identity (Fischler, 1988) and collective culture, thus, organization’s identity and values may also “speak” through food (Cramer, Greene & Walters, 2011). Furthermore, studies have shown that when people eat better they feel better (Mujcic & J.Oswald, 2016), and when people eat together, they belong (Cornejo Happel, 2012) which is also linked to well-being and social sustainability. For example, these are aspects that might relate to some factors that influence employees’ productivity, engagement, collective membership or organization’s performance (cf Hong et al., 1995). Therefore, it could be of importance that organizations “nourish the workplaces” with food initiatives to connect employees with organization’s culture and identity. Although the connection between food and organization’s culture is still an area of constant exploration, some organizations are finding value into implementing different food strategies such as opening canteens, providing healthy snacks, reviewing the calories on the restaurant menus, providing food vouchers, creating in-office farms or having cooking sessions (cf Nyberg & Olsen 2010).

As food is gaining momentum into the organization strategies, food could become a relevant part of the “cultural vibe” to strengthen organization’s values while improving societal conditions. As defined, food is more than health and nutrition, as it represents many other aspects related to culture and society where other contextual internal – external factors might play an additional role. All these employees’ empowering and rewarding strategies linked to food are currently found among some innovative companies such as Oracle, Google, Canva or Airbnb. Thus, creating a new “vibe” through food became an important element for some organizations to engage employees and impact their well-being and job satisfaction. The objective of such a strategy could be, for instance, to provide healthy food for the employees, thus to improve their health (cf Staniškienė & Stankevičiūtė, 2018), while building membership or community which is also linked to overall employees’ well-being and social sustainability (cf Helne & Hirvilammi, 2015). Studies shown how for example, the work atmosphere or good relations with colleagues are factors that influence job satisfaction (Sypniewska, 2013). Furthermore, results from a study by B. Plester (2014) show that food rituals help to create a positive organization’s culture and to enhance employees’ loyalty and effort (Plester, 2014) which might help strengthen team bonds. As a result, companies might develop values and provide their employees with high-quality food experiences to enhance organization’s identity through food what was one of the aspects that motivates this study (Boutaud, Becut & Marinescu, 2016). Additionally, results from a study from Sroufe and Gopalakrishna Remani (2018) concluded that non-financial rewards are relevant for job attractiveness of potential employees (Sroufe & Gopalakrishna Remani, 2018), thus, food strategies might serve as an additional reward mechanism. Therefore, food practices at work could enhance employee

3 development which have an impact on the organization’s internal social sustainability and, ultimately, in financial performance (cf Sroufe & Gopalakrishna Remani, 2018).

These complex dynamics incentivized this research and will be subjected to further analysis by understanding the opinions of employees regarding food during their daily situation at the workplace in Sweden, the location where the study was conducted.

1.1.1 Integration of Food in the Organization’s Culture in Sweden

Sweden is one of the countries taking different actions in order to implement the 2030 agenda based on its economic, political and social context. Sweden’s Ministry of Health and Social Affairs’ objectives, in line with the SDG 3, are to support better societal conditions for good health, secure long healthy lives, well-being and to provide sustainable-efficient healthcare system for all. In order to achieve these goals, Sweden counts with the commitment and collaboration of multiple stakeholders from different governmental, civil society and private sectors, such as universities, research centers or NGO’s. These results shown that governmental agencies, such as the Public Health Agency, the Swedish Food Agency, and the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, must collaborate with the private sector in order to achieve the SDG 3 among other sustainable goals. Additionally, Trade Unions empower employers to invest into employees’ health and well-being at work, which reduce costs and increase productivity (Government Offices of Sweden, 2018).

Besides the governmental efforts to improve health and well-being, the absenteeism rate in Sweden due to sickness has been in constant growth for many years. In 2018, the average day of absence per employee in Sweden was 11,3 days in comparison with 6,7 days back in 2010 (OECD, 2020). One aspect to take into consideration is that in Sweden, “the first fourteen days you are sick, employer pays you sick pay instead of your regular salary” (Försäkringskassan, 2020). If a person needs a longer period that exceeds the fourteen days, the person will apply for benefits from Försäkringskassan (Försäkringskassan, 2020). Additionally, if you have children and they are sick, you are obligated to stay at home from work. These welfare policies might provide flexibility to Swedish employees to stay home if needed, as they have a strong national welfare system. However, these increasing absenteeism numbers due to diverse reasons might affect the productivity and ultimately, the internal sustainability of Swedish organizations, and as a consequence, might affect at a societal level.

The strong Swedish welfare system is part of the national strategy and culture. Hence, Swedish organizations might find valuable to incorporate strategies that motivate employees while engaging with the company by impacting positively on employees’ health and well-being. In this context, food and culture has been historically linked until this date (cf Grimaldi, Fassino & Porporato, 2019). Food norms and practices have defined the individual and the collective identity (Boutaud, Becuţ & Marinescu, 2016), which might be relevant to study in Swedish organizations. One example of Swedish culture is the long-standing tradition called “fika”, or translated into English as “coffee break". Fika is popular within Swedish organizations, and it is used as a fundamental break when to interact with colleagues, socialize or to break the routine (Uusimaki, 2020). However, there is a need of exploration to understand further Swedish organization’s culture by studying employees’ perceptions about food at their workplace. In this context, food became of relevance to be analyzed as a possible element linked to employee satisfaction that could impact the internal sustainability of Swedish organizations.

1.2 Research Problem

The integration of food in the organization’s culture to enhance employees’ well-being, satisfaction, engagement and productivity is a current raising strategy among global companies to ensure organization’s internal social and financial sustainability (cf Staniškienė & Stankevičiūtė, 2018). However, although food is an important element of culture and identity

4 (Grimaldi, Fassino & Porporato, 2019), there is insufficient research that identifies food as a factor of the organization’s culture that might strengthen organization’s social and financial sustainability. Hence, it is relevant to conduct a study to gain a deeper understanding of the connection between food and organizational culture throughout employees’ daily food experience at work. This will enable to better grasp the relationship between food, organizational culture, employee well-being and satisfaction, and organization’s internal social and financial sustainability.

Furthermore, food and eating habits are very personal down to the individual level (Boutaud, Becuţ and Marinescu, 2016). However, employees shape organization’s culture and identity and vice versa (Tolbert & Hall, 2009), which made us wonder what are the employees perceptions and expectations on this topic. In this context, up to this date no previous research was conducted in Sweden about how employees perceive food in the organization’s culture and what they expect regarding food within their company. These aspects made very interesting to focus on this topic by adopting employees’ perspectives.

Finally, it is valuable to conduct this research in the Swedish context for two main reasons. First, Swedish organizations might be more committed to sustainability because of Sweden’s national policies linked to sustainability (Government Offices of Sweden, 2018). Secondly, food initiatives might be present in the Swedish society and organizations through, for instance, the long-standing tradition fika (Uusimaki, 2020). Therefore, the Swedish context might be one the most relevant as well as suitable places to conduct research about food and organization’s culture.

1.3 Research Purpose

The purpose of this research is to explore what is the connection between food and organizational culture throughout employees’ daily situation at work. Thus, this study aims to illustrate and fill the identified research gap and enable to better grasp the relationship between food, organizational culture, employee well-being and satisfaction, and organization’s internal social and financial sustainability.

1.4 Research Question

In accordance with the purpose, this study will respond to the following research question and sub-questions:

Are there elements that connect food and organization’s culture within organization? If so, what are these elements?

A. What are the “perceptions” of employees regarding food norms within their organization?

B. What are the “expectations” (employees’ desires) of employees regarding food norms at work?

5

2. Theoretical Framework

This chapter had been written after a thorough literature review which gave us an insight of existing theories relevant for this research. Thus, each section presents conceptual and theoretical foundations which contributed to the overall understanding of our research, and helped us to understand and analyze the results coming from the research. Consequently, the theories laid out in this theoretical framework pertain to organization and management theories relevant to this paper, namely the concept of Schein’s Multi-Layered Organizational Culture Model, the Competing Values Framework (CVF) and the Sustainable Well-being Productivity Synergy (SWPS) theory.

2.1 Concepts of Organizational Culture

As established, food might be a factor of the organizational culture to ensure organization’s internal sustainability. Therefore, it is crucial to have an in-depth understanding of this concept in order to conduct this research and reach the purpose. A deeper comprehension of organizational culture’s concepts and model will ease the identification of possible elements that connect food and the organizational culture. Over the past years, the term “organizational culture” had been used to define and describe organization’s internal identity and characteristics (Sims, 2000). In this chapter, organization will refer to all kinds of private, public, government and nonprofit organizations (Schein, 2010).

2.1.1 Schein’s Multi-Layered Organizational Culture Model

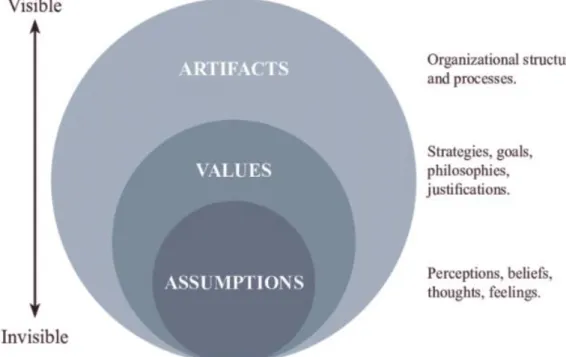

As defined, organizational culture is a set of basic assumptions, values and artifacts that build the internal culture of an organization. In the Multi-Layered Organizational Culture Model, Schein (2010) classified these assumptions, values and artifacts into three levels of culture that are visible and invisible within an organization (Ferràs, Morente & Žizlavský, 2017). The model suggests that the organizational culture consists of artifacts shaped by organization’s values, which are shaped by basic assumptions (González et al., 2018).

6 Artifacts

First, on the surface of the organizational culture, artifacts are visible to the organization’s members and non-members through different forms of organizational aspects (Schein, 2010) (Ferràs, Morente & Žizlavský, 2017). For instance, organization’s physical characteristics such as the architecture, interior, office design and dress code are visible artifacts that define and shape organizational culture. More, adopted language through modes of speaking, special expressions and slogans, used technologies as well as visible traditions, norms, social practices, social interactions are also visible artifacts that reflect on the culture of an organization. So, through these aspects a part of the organization’s culture can be observed and identified (González et al., 2018). Therefore, while conducting the study, it is relevant to have a closer look to visible artifacts within Swedish organizations that might help us to identify possible artifacts that connect food to the organizational culture through, for instance, the organization’s environment, traditions or social practices.

Values

Then, according to Schein’s Multi-Layered Organizational Culture Model, the next level which build the organization’s culture is the values of members (Schein, 2010) (Ferràs, Morente & Žizlavský, 2017). Espoused values constituted organization’s affirmed strategies, visions, goals, philosophies and rules of behaviors. Although values are less visible than artifacts as they cannot be clearly observed in the organization by members and non-members, they can be found in organization’s official public statements of identity. Thus, values provide hidden meanings on which organization’s artifacts such as organizational structures and processes, behaviors, social interactions or language are built and through which artifacts can be decrypted and understood by members and non-members (González et al., 2018). Hence, while conducting the research, it is relevant to intend to reveal and understand organization’s values by giving a particular attention to organization’s structures, social dynamics and members behaviors regarding. Thus, this will enable to identify possible hidden meanings or a sense to organization’s food-related artifacts and values found within Swedish organizations.

Assumptions

Finally, the third level is constituted by assumptions which cannot be measured but still influence the organizational culture (Schein, 2010) (Ferràs, Morente & Žizlavský, 2017). These are organization’s members assumed values, beliefs and facts which are not visible but do impact organizational culture. For instance, practices implemented within the organization without being discussed and explained, but still understood and applied are rules that constitute the third level of the organizational culture. Thus, assumptions represent the unconscious facet of the organizational culture as they are not written down nor discussed, or even acknowledged by organization’s members. Consequently, underlying assumptions are difficult to identify and described, and they are truly understood by people who are aware of the organization’s way of working. Thus, assumptions are difficult to relearn and modify (Ferràs, Morente & Žizlavský, 2017). Although assumptions are difficult to identify and describe by members and non-members, it is interesting to intend to recognize some of these while conducting the interviews by analyzing interviewees’ behaviors or habits that could reveal organization’s assumptions on which values are built.

2.1.2 Organizational Culture Creation and Maintenance

The creation of a culture is similar to the creation of a group, they both need shared beliefs, values, philosophies that emanate from common experience. Thus, the two go hand in hand, meaning that there is no “culture” without “group” and there is no “group” without shared assumptions, values and artifacts which refers to “culture” per definition (Schein, 2010). Thus, groups play an important role within the organization’s culture, therefore, it is interesting to

7 analyze group dynamics and social interactions when conducting this study. Additionally, there are four main categories of mechanisms that help create and maintaining cultural features within organizations as listed below:

1. norms and practices fostered by leaders and founders; 2. critical problems which enhanced organization’s learning; 3. need to create bonds among organization’s members; 4. organization’s environment.

Thus, when conducting the research it is relevant to look these mechanisms that could be related to food as these are elements that shape the organizational culture and make every organization unique in their own way (Kalaiarasi & Sundaram, 2017). More, per definition, organizational culture leans towards patterns and integration. Thus, patterning and integration enable members to accept and adopt defined actions, behaviors and thinking that refer to artifacts, values and assumptions, respectively regardless if those are positive or negative (Sims, 2000). Thus, organizational culture not only enforces the connection among members and create a shared vision and perception, but also influence members behaviors, beliefs, values and way of working (Kalaiarasi & Sundaram, 2017). So, it might be possible that organizations shape employee relation to food, thus influence employees’ eating habits, but also social interactions around food. Therefore, while conducting this study, it is interesting to have a look closer at all the norms and practices related to or build around food, but also to group dynamics and employees social interactions when eating at work. Indeed, this could enable to find out and better understand organization’s values and relevant food-related elements that shape Swedish organization’s culture.

2.2 The Competing Values Framework

The second framework proposed for this study is the Competing Values Framework (CVF) to interpret and organize organizational phenomena (Cameron & Quinn, 2013). The framework is used as a valuable tool for this thesis as it can help to identify different cultural and HRM approaches such as organizational quality or effectiveness that are linked to employees’ well-being. Additionally, the internal-external dimension of the model reflects whether the organization is focused on its internal or external factors that influence the organization’s dynamics (Linnenluecke & Griffiths, 2010). Furthermore, the Quinn model is based on four different cultures or management models that will help us diagnose the changes needed to improve organizational culture for further establishment of organization’s food culture. The framework is recognized by scholars to have empirical validity (Cameron & Quinn, 2013).

As seen on Figure 2, the CVF model shows the multiple dimensions within the organization as well as the complexity and the ambiguity of the elements that are components of the organization’s culture. For the purpose of the thesis, we will focus on the Human relation model and the open system model called “family/clan culture”. Clan culture focuses on the employee development and well-being. In words of Cameron and colleagues (2006) “organizations succeed because they hire, develop, and retain their human resource base” (Cameron et al., p. 38, 2006). For example, Powley and Cameron (2006) stated that cultural organization healing are found in clan culture attributes such as focusing on employees’ well-being, incentivizing connections, strengthening family values, or starting certain ceremonies or rituals to bring people together (Powley & Cameron, 2006). Additionally, the clan culture increases employees trust, sense of belonging or affiliation, or extra support (Cameron & Quinn, 1999). These aspects can also be strengthened by food and food rituals, which might assist organizations into creating strong bonds between the organization and its members.

8 Figure 2. Description of the culture archetypes within the CVF for Organizational Culture. Adapted

from Cameron and Quinn (Scammon et al., 2014).

Furthermore, these cultural elements might result on enhancing the employee’s morale,

level of satisfaction and commitment (Cameron & Ettington, 1988). Thus, as one of the most ordinary popular rituals, food might be that agent to transition to a clan organization’s culture as stated before. Therefore, implementing food into the clan culture of the organization not only shows leadership, but might also be one of the aspects to consider to ensure internal social and financial sustainability within organizations (cf Cameron et al., 1988). For example, rewarding employees with sensitive food strategies might have a deeper meaning, such as showing employees appreciation and recognition. Nevertheless, these elements can be highly dependent on organizational goals and internal-external characteristics, focus and differentiation as seen on Figure 2.

The CVF model is aligned with what potentially food might shape, strengthen and represent within the organization’s culture, and the impact it has on the employees’ well-being, involvement, satisfaction or loyalty. Therefore, developing a “family/clan culture” which includes employees food needs could be an innovative way for organizations to differentiate, ensure well-being and satisfaction or retain talent. Another important point of Clan culture is that these types of organizations focus on well-being as well as employee development, and help individuals reach their maximum potential, which can be connected to food. Thus, internal and external culture might be considered in this thesis to 1) use elements in what food is a tool to improve the employees’ well-being and satisfaction and; 2) find organizations differentiation by implementing food in the culture what might help retain talent and create membership among employees (cf Pandita & Ray, 2018).

2.3 Sustainable Well-being Productivity Synergy

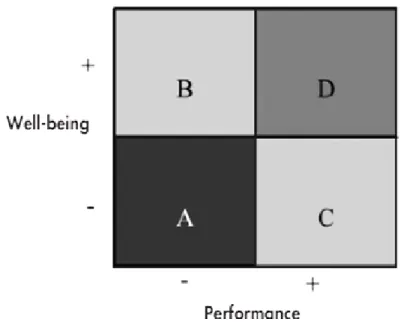

Another concept that is valuable for this study is the Sustainable Well-being Productivity Synergy (SWPS) which is a concept that consists of fostering and ensuring employees’ well-being in order to improve and sustain organization’s competitiveness in the long run. SWPS is illustrated by not only employees’ well-being at work and job satisfaction, but also personal life goals, dedication and development along with a high level of value-creating tasks within the organization. Thus, according to this concept, the synergy between employees’ well-being and performance generates a continuous improvement spiral of well-being and performance which

9 ensure organization’s social and financial sustainability (Ayala, Lorente, Piero & Tordera, 2014). On the Figure 3, the four combinations of well-being and performance existing in organizations are represented. The quadrant A illustrates low levels of both variables which represent “unhappy and unproductive” members. Quadrants B and C illustrate “interactions of tensions” which represent respectively “happy and unproductive” and “unhappy and productive” members. The quadrant D illustrates a “balanced interaction” which represent “happy and productive members” and demonstrate the SWPS (Ayala, Lorente, Piero & Tordera, p. 11, 2014).

.

Figure 3. Four basic interactions between well-being and performance at work (Ayala, Lorente, Piero & Tordera, p. 11, 2014.

Although well-being and performance of employees cannot be measured in this study, SWPS theory is relevant in this study to support possible findings and make assumptions based on them. Indeed, when conducting the research, it is relevant to look at whether food is a satisfactory element for employees in their daily situation at work that could improve employees’ performance. Indeed, food could have positive or negative impacts on employees’ well-being and happiness that could reflect on their performance and productivity. In the long-run, this could reflect on the organization’s internal sustainability in form of, for instance, decrease of productivity causing financial struggles, or increase in employee involvement causing higher productivity.

10

3. Methodology and Methods

In this chapter will be described the methodology, research approach, research design, and research methods utilized in order to collect relevant data that will help to answer the research question and the sub-questions and fulfill the aim of this study. Additionally, the method of data analysis as well as the reliability and validity are presented. Finally, ethical considerations are raised.

3.1 Research Approach

Given the insufficient research looking at the connection between food and organization’s culture, this study will be an exploratory research. As the connection between food and organization’s culture is not clearly defined, an exploratory research is needed in order to explore the research topic and enable a better understanding of the studied phenomena (Dudovskiy, 2020). Thus, this exploratory research will initiate the research by first exploring the connection between food and organizational culture throughout employees’ daily situation at work, before eventually conducting descriptive and explanatory research in the future. While conducting the research, an inductive reasoning will be adopted to base the study on a question in order to avoid any assumptions that could bias the result (Bellamy, 2012). Therefore, the result of the study will be grounded theories, inductive methods are used in order to develop theories to explain empirical phenomena. Thus, accordingly statements and generalizations will be constructed at the end of the study through the data collection and analysis (Walliman, 2017).

Qualitative methods will be used in order to collect data. These methods will allow to explore the research topic thoroughly, find out valuable and critical information and gain a deep understanding in the specific context setting (Silverman, 2015). Thus, qualitative research will allow us to better understand employees’ perceptions and expectations by exploring individuals’ perspective of food in their daily situation at work in the Swedish context. Additionally, the analysis of the qualitative data will enable to not only identify how food is perceived and expected to be, but also to identify what is behind employees’ perceptions and expectations. For this purpose, a semi-structured interview will be conducted in order to collect primary data. This will enable to identify elements that connect or not food and organization’s culture. The reason to choose semi-structured is to have the possibility to include follow up questions spontaneously based on participants answers that are not in the interview guide. It provides both depth and more detail, also creates openness by allowing participants to express their views and to the researcher to ask further questions (Kvale, 2007). Then, peer reviewed papers, books and reports will be used to collect secondary data and analyze the findings and identify what are the elements that connect food and organization’s culture.

3.2 Research Design

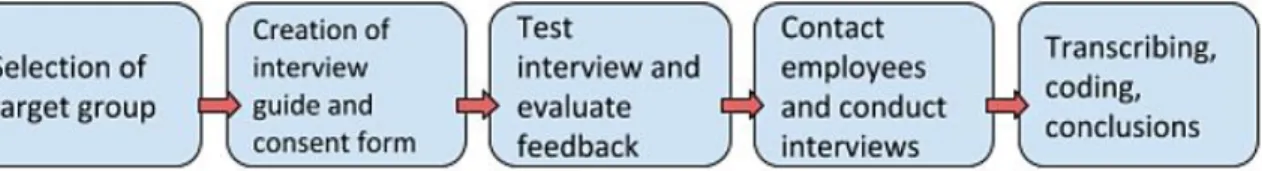

In order to conduct the qualitative research, five different stages had been identified. Indeed, a clear planning of research helps researchers to ensure a methodically rigorous data collection (Roller & Lavrakas, 2015). First, the study population and the target group had been identified. Then, consent forms and interview guide had been created in order to collect primary data, these are available respectively in Appendix A and Appendix B. Thus, participants had been contacted and recruited in order to conduct the interviews and gather empirical data. Finally, interviews had been transcribed, coded and analyzed in order to lead to findings and conclusions. Each stage had been explained in detail in the following sections. Hence, the logic model of the qualitative research had been illustrated on Figure 4.

11 Figure 4. Logic model of the qualitative research.

The logic model of the quantitative research helped the researchers to follow the steps thoroughly and in a logical sequence in order to lead to the qualitative empirical data, findings, analysis and conclusions.

3.3 Study Population

As the focus of the study is not a specific organization, but a phenomenon that occurs in most organizations, the research covers public/private and medium/large-sized organizations which are based in Sweden. Throughout a large study population, we aimed to represent as many industries as possible as there were no previous studies about this research topic up to this date. This enabled us to have access to diverse participants with different daily situations linked to food at work. Thus, we were able to study various organizational conditions and explore the research gap in order to get a deeper understanding of the connection between food and organizational culture.

A stratified random sampling technique was used to recruit participants based on gender, organization’s size and geographical characteristics. Personal network was used as strategy to connect with the employees. A goal of ten employees were selected, five participants of each gender. In order to fulfill the purpose of the study, participants had to meet certain criteria. Participants were selected based on their gender, on their company’s size and lastly, that their workplace was in Sweden. Thus, a further detailed summary of the selected participants for the study, which includes gender, industry, sector and organization’s size, are presented on Table 1 below:

Table 1. Summary of the selected sample.

Participant Gender Industry Sector Size

P1 Male Technology Private Large

P2 Male Education Public Large

P3 Male Energy Private Large

P4 Male Energy Private Large

P5 Female Banking Private Large

P6 Female Furniture, retail Private Large

P7 Female Banking Private Large

P8 Female Architecture & Engineering Consultancy Private Large

P9 Female Governmental institutions Public Large

P10 Male Religious Organizations Private Medium

Thus, final participants were five male and five female in order to avoid gender bias. All of them work full-time from their respective offices, an in medium or large-sized, and public or private organizations located in Sweden.

12

3.4 Methods of Data Collection

For the purpose of this study, first, secondary data was collected in order to support the background, as well as the theoretical framework. Secondly, primary data sources were collected by conducting semi-structured interviews. Before the interviews a consent form was handed in to participants as seen in the Appendix B. The interview guide was creating in accordance with the research topic in order to answer the RQ and sub-questions, and thus fulfill the research purpose. The semi-structured interviews were conducted as it is the most suitable method to investigate employee perception and expectation regarding food in the organization’s culture (Kvale, 2007). The interviews were equally conducted and distributed by the researchers. Additionally, we will support the findings including reviewed papers, reports and research that can help answer the research questions. Thus, the results based on the semi-structured interview might highlight whether or not food is connected to organization’s culture and can be used to strengthen organization’s culture and, thus ensure organizations internal sustainability. Furthermore, the findings from this study could be used to incentivize further the implementation of food strategies as a part of the organization culture to potentially increase employees’ well-being and, therefore, the social and financial sustainability of organizations. 3.4.1 Interview Guide

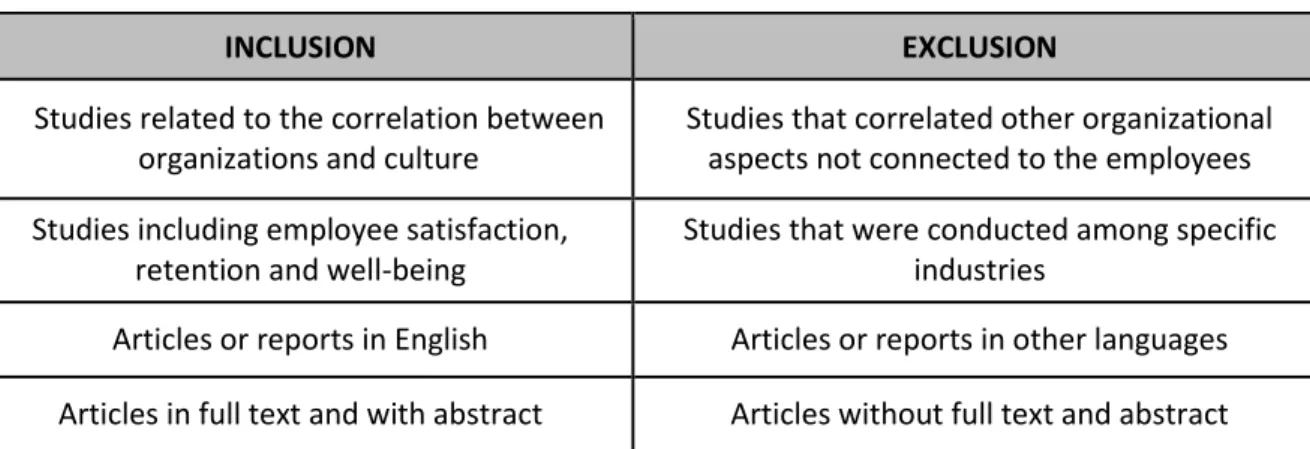

Before conducting individual interviews, a literature review was conducted to construct themes appropriate for the semi-structured interview guide. The keywords used to identify the relevant literature were “organization’s culture”, “employee satisfaction and well-being”, “employee retention”, “food strategies”, “food cultures”, “organization’s social sustainability” and “organization’s financial sustainability”. The search through the publication portals Google Scholar and ResearchGate resulted in a total of 208 publications. Thus, ten publications were selected to inspire the study as seen on Appendix E, the other 198 were excluded based on inclusion and exclusion criteria as seen on Table 2:

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for literature searches.

INCLUSION EXCLUSION

Studies related to the correlation between organizations and culture

Studies that correlated other organizational aspects not connected to the employees Studies including employee satisfaction,

retention and well-being

Studies that were conducted among specific industries

Articles or reports in English Articles or reports in other languages Articles in full text and with abstract Articles without full text and abstract

Thus, the interview guide was created based on the literature review and theoretical framework in order to fulfill the research purpose and answer research question and sub-questions. Therefore, each questions’ purpose and outcome had been thought thoroughly in order to reveal all the possible aspects of employees’ perceptions and expectations regarding food in their daily situation at work, from an individual and an organizational level. All questions had been created in order to allow respondents to give in-depth descriptions, provide personal opinions and expectation regarding food habits and food strategies, from the individual and organizational level. The interview guide was tested with two people (one male and one female) recruited through personal network. The participant testing the interview guide provided feedback about the initial length and structure of the questions. The participants gave

13 some positive and negative feedback. For example, the initial interview was planned between thirty and forty minutes. The participant’s feedback was that the time span was too long and answering the interview created an impatient feeling. Therefore, from initial list of questions we decided to take out one question that appeared redundant. One of the positive comments was that questions were understandable and easy to answer even though the participant was not so comfortable answering in English. The interview was tested a second time with the same participants once the questions were modified. After the modifications, a second test was conducted to ensure validity. The questions for the second interview predicted to last around thirty minutes.

3.5 Method of Data Analysis

Each participant was interviewed individually for approximately thirty minutes using a mobile app for the voice recording. Each of the researchers interviewed five participants, then transcribed their respective interviews. The spontaneous questions and answers had been included in the transcriptions. The interviews were transcribed into a word document that was later printed for hand coding. Once the interviews were transcribed, we started to get familiarized with all the data by reading the transcripts thoroughly. Then, the reflection part took place, where the data was criticized and evaluated according to previous studies and theories. Then, themes were coded by hand using notes and color coding. The coding process was done by following different stages:

1 – Firstly, different words, phrases and sentences were identified, then were broken down

into useful chunks of data. Different colors had been used in order to start organizing the data.

2 – Secondly, we started the so-called ‘open coding’, which means reading the transcripts

and determine the different categories in the data. Thus, one or two words were given to summary or code each line of data. The result was a list of twenty-nine codes, some of them were redundant.

3 –After open coding, the twenty-nine codes were reduced into fifteen final codes by conducting the conceptualization part, also known as ‘axial coding’, where the codes from the open coding were used to see how the different categories relate to each other by similarity, difference, frequency, sequence, correspondence or causation. Finally, the list had been narrowed down to the final six codes as seen on Appendix D.

These final themes are reflecting the purpose of this research and it is sensitive to what was found in the interviews with themes and related codes found in the transcriptions.

3.6 Reliability

The data collection of the study followed academic methods based on qualitative research process (cf Roller & Lavrakas, 2015). The data collected during the interviews was fully transcribed and coded. Because of the Covid-19 special circumstances when this study was conducted, the researchers added additional observations sheets to the online interviews in order to have as more detailed data as possible when transcribing. To provide consistency on the results, transcriptions and coding were conducted by the same person, for after being reviewed by the other researcher to provide consistency and accuracy. The research method used to conduct the study could be replicated in other countries. In order to gain results that can be transferred to multiple contexts, participants from multiple organizations and industries had been recruited as the focus of this study is not a specific organization, but a phenomenon occurring in most organizations. The number of participants recruited was based on Lincoln

14 and Guba (1985) arguments “an investigator cannot fully guarantee generalizability and thus appliers are nevertheless advised to conduct small verifying studies to be certain that the transferability of account is indeed plausible” (Lincoln & Guba, p. 298, 1985). Thus, a sample of ten people from ten different organizations had been defined in order gather sufficient descriptive data and ensure transferability. Furthermore, there is a lack of similar thematic research in Sweden which makes difficult to compare this research with previous similar studies.

3.7 Validity

The validity of the research was shown meaningful and trustworthy results. Primary validity criteria were ensure with credibility, the authenticity of the study design, methods and by the integrity of the research. Moreover, secondary validity criteria such as explicitness, creativity, congruence, and sensitivity concluded with the validity of the study (Whittemore et al., 2001). In order to ensure that, investigating triangulation, “each different evaluator would study the program using the same qualitative method”, and theory triangulation, “multiple professional perspectives to interpret a single set of data/information” were thoroughly used (Guion, pp. 2– 3, 2002). In order to answer the RQ, researchers elaborated an interview that was including topics of concern. Additionally, the interview guide was tested twice by both researchers to make modifications and adjustments based on feedback provided by the participants. Furthermore, the data collection and sample size were tailored to the special circumstances of COVID-19. Firstly, personal network was used to recruit participants which resulted in ensuring the amount of participation targeted for the research. Secondly, interviews had to be conducted online instead face to face due social distancing global measures. Although the research was conducted in Sweden, we included participants with different backgrounds. As Sweden is a diverse country, we wanted to be as representative as possible. In order to avoid interferences in the communication and taking into account that English was not the first language of either participant or researchers, the interview questions used simple vocabulary. More, we employed same number of males and females in order to avoid gender bias. Moreover, the external validity of the results is based on the valuable outcomes that help closing a research gap in Sweden.

3.8 Ethical Considerations

Ethical aspects had been raised while conducting the qualitative research. Thus, ethical requirements for research conducted in Sweden were considered in this study (Swedish Research Council, 2017). The firstly the ethical requirement concerning information to join the study, secondly, provision of the consent form itself, third, the obligation to ensure confidentiality and lastly, informing the participant how the information will be used. Before the interviews, the participants were informed about the topic and purpose of the study. Confidentiality was guaranteed prior conducting the interviews. Furthermore, all the participants signed informed consent forms before proceeding with the interviews, respecting European GDPR data individual protection law and regulations (EU GDPR, 2016). Their names were not included in the findings, and they were assigned an identification code based on interview number and gender. As the chosen topic could touch upon sensitive points, for example personal information such as personal food habits or organization preferences, the interviews were conducted individually. The consent form (Appendix A) will be kept in safety, moreover, just after conducting the study, the information will be destroyed.

15

4. Results

This chapter presents the results that came from the data collection by means of semi-structured interviews. The main findings have been reported and several themes have been extracted from the collected information and presented accordingly.

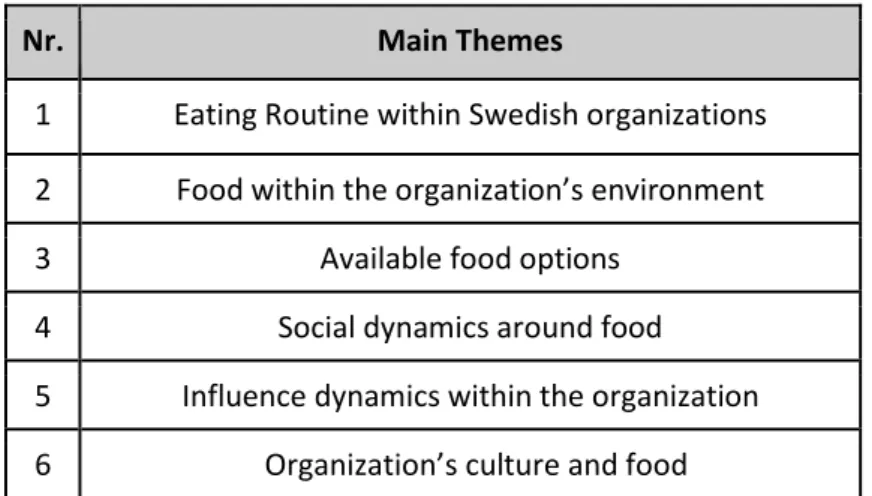

Before addressing the content of the data collected from the interviews, we present in the following table the themes that emerged from it. A total of six main categories were identified, each of them accounting for different importance.

Table 3. Themes of collected interview data.

Nr. Main Themes

1 Eating Routine within Swedish organizations 2 Food within the organization’s environment

3 Available food options

4 Social dynamics around food

5 Influence dynamics within the organization 6 Organization’s culture and food

The final quotes selected for the findings are edited. So, breaks, irrelevant passages or comments from the interviewee may be in some cases omitted to make the quotes more precise. The extra comments were made by hand on paper. To make easier to refer to the interviews and interviewees and preserve anonymity among the participants, a code encryption was used.

Table 4. Code encryption of interviews and participants. Participant based on interviews order Sex

P (participant) – interview number F – Female P (participant) – interview number M - Male

On the Table 4 is shown the logical order followed to refer anonymously to participants. Thus, we divided the participants based on gender and the chronological order when the interviews were conducted. Therefore, we will refer to their gender, female or male, followed by participant (P) and their ordinal number. For example, the participant one female will be represented in the findings as followed, P1F.

4.1 Organizational Structure Around Food

The first common food related organizational norm we have identified was the breakfast routine. Indeed, most of participants described their company providing breakfast for free to their employees at a certain degree. The breakfast is included during employees working time, and a specific time period is dedicated to it within the organization. Common elements of breakfast mentioned by participants were bread, butter, cheese, jam and cucumbers. One of the participants described the breakfast routine as below:

“We get breakfast at work so I get to work like at eight and nine o’clock we have breakfast for half an hour and the employer give us for free bread and buns

16 with a variety of batter, cheese, and ham, kind of standard sandwich material…” – P4M

Most of participants expressed a positive opinion about having breakfast provided by their company. For instance, one of the participants explained including the breakfast in her eating routine because of the company initiative:

“I didn’t eat breakfast at all at home, and then it was really good to have breakfast at work and to get that into my day in an easy way…” – P8F

Thus, by providing breakfast, the employers give the opportunities for a meal that should have been taken at home. More, another respondent expressed the importance of having a breakfast routine at work, and stated avoiding stress because of the easy access to breakfast through the company initiative:

“I know that I’m able to have breakfast at work, so I will not stress about it during the morning that ‘oh I need to eat’. Because for me it’s very important that I eat breakfast at some point. When I know they already served at eight, I will be there like around a quarter to eight. Then, I know that I will come there and I just

can land and then I can eat somewhere. So that way, I think it is very good that they always serve breakfast actually and that we have access to it…” – P5F

Thus, the employers satisfy a need by providing breakfast. Additionally, another common food related routine that we have identified within Swedish organizations was the coffee break, also known as fika. Indeed, excluding P3M, all respondent have scheduled breaks in the morning and/or in the afternoon. Still, all participants stated having coffee, tea and water provided by their company all day long without any limitation. However, participant P9F, for example, stated that although fika was provided by the company, colleagues and working unit where she is employed was not participating as they had a different “culture”, more “diverse” and “less traditional”:

“...so me and my colleagues we don’t have the culture of fika either, many people go and have fika with their colleagues but not in my unit … on Fridays we

have a lunch together in my unit and we out to eat in a restaurant together…”– P9F

Then, an additional food initiative found within Swedish organizations and provided for free by the interviewee’s companies were snacks and fruits. Except P9F, all respondents have fruits provided by their company. Most of participants expressed eating more fruits as it easily accessible and provided for free:

“I definitely like the fruit options, I wouldn’t eat that much fruit if I didn’t have it at work.” –P8F

Through the respondent’s words, we can see that by providing fruits employers fulfill a desire or a need. Another participant expressed avoiding buying unhealthy snacks by eating a fruit instead as it is easily accessible and free:

“I get tempted to buy something (refers to unhealthy snacks), but most of the time, I will grab a fruit instead…” –P3M

Thus, by providing fruits for free, employers save employees’ money whom would otherwise buy snacks. Finally, lunch is the break that has been identified in all the interviews. Indeed, all

17 participants have a scheduled lunch break during their working time between 11 am and 1 pm. Dedicated time to lunch break, identified within Swedish organizations, were between thirty minutes to one hour. Thus, one of participant expressed the importance of having enough time to have lunch:

“Once worked in a hotel a long time ago. There it was, hmmm, they had very good food since it was hotel food, but we only had 10 minutes because it was

so stressful. I think that’s really, really bad. Because it doesn’t matter how good food you get if you just have 10 minutes to eat that’s just unhealthy. Hmm so

appreciated if you have time to eat …” – P10M

However, during the interviews certain participants admitted skipping breakfast and coffee break or significantly shortening lunch break for different reasons despite the dedicated time provided their company. For instance, respondent P8F explained this behavior through these words:

“I normally go around 12:00 and I normally eat and like have a one-hour break. I like a long break to relax in the middle of the day. But people go on from

11 until till one, I guess. I think maybe it is more usual to have a shorter lunch break like half an hour. […]I don’t eat breakfast at work. But I used to before, but

now I have a lot of meetings too, so I don’t really have time to go there.”

Thus, it does not matter if the employer provides food as if the workload is high employee won’t have time or won’t spare time to eat anyway. Hence, a more or less similar food routine had been identified within Swedish organizations. Food related organizational structures, processes and supports are fostered by companies and are clearly visible when looking at Swedish companies. Thus, the established food routine and food-related structures can be clearly identified through the participant words:

“Every morning, and it’s always served at 8 am. And then, at 9 am the fruit man he will come, and he will provide us with bananas, apples, oranges, kiwis […]And then, we have lunchtime between 11:30 am and 1:30 pm. So it’s, it’s a little bit depending on who wants to go first. So normally we have 30 minutes of break. So, for example, I always have my lunch 11:30 […] So, in that way, I think

it’s good that there are like structure, so you eat breakfast and then you have lunch at this time” – P5F

Thus, time is an important element in relation to food. As detailed by participants, a schedule build around food had been found within Swedish organizations. Indeed, we found that companies were structuring the eating routine of their employees throughout different scheduled breaks and time dedicated to food. These enabled organizations to introduce certain eating habits, such as breakfast or fika, to employees daily life at work. Additionally, interviewees revealed positive feelings and satisfaction regarding these strategies.

4.2 Food Within the Swedish Organization’s Environment

Several common food-related facilities had been identified within the environment of participants company. First, specific physical spaces dedicated to food such as kitchens, canteens, cafeteria, eating rooms, restaurant, food stand and fruit corner had been identified in the collected data. Positive and negative descriptions of the eating environment had been identified. For instance, the participant below described in a very concise way the eating environment with positive words:

18 “...facilities for eating is spacious, light, fresh, and comfy…” —P4M

Participant P9F gave a positive description of the eating environment by using positive and rich words such as “really big”, “long” and “a lot of”.

“We have a kitchen, two kitchens! and one with a lot of microwaves like 20 microwaves and four really big refrigerators and there is a long dining area…” –P9F Participant P6F emphasized the abundance of eating facilities:

“In the first floor we have the cafeteria, on the first floor is the restaurant, they cook all the dinner and they prepare all lunches, like it is a real restaurant I have to say

that, but you also can eat on the first floor emmm if you would like to you could also bring the food to another floor or to another space.” – P6F

However, abundance of eating facilities was not always seen as a positive by participants: “What I desire is that we do not have a kitchen on every floor of the company but a few bigger facilities where we could eat and mix all the departments better. Now because we do not have time we go to the closest kitchen

and do not mix with people from other departments. That is could be better.” – P7F

While, P5F gave a negative opinion and description of the eating environment:

“Facility could be nicer. Because it’s like a room that we’re eating it we have no windows, for example. So, if somebody is warming some food that smells

fish, then I come and eat there. Afterwards, I can sit there in a smelling kitchen and that sometimes it’s not so nice the environment could be better for

eating…” – P5F

Then, food-related equipment had been identified. Mostly, heating microwaves, fridges, cutlery, glasses, plates and cups are at the disposal of employees within their company that allow employees to bring lunch boxes from home. Certain participants, such as P5F, expressed their satisfaction of having available facilities and equipment that enable to bring homemade food for lunch:

“I will always take leftovers from dinner. So, I would always cook a little bit extra […] We have access to microwaves and I’m so grateful for that because

then I can have a hot meal in during lunch time…’ – P5F

However another participant described having access to the kitchen and other food preparation utilities at their workplaces, but not being interested into using it due personal preferences:

“Ah, I don’t like to cook, that is one of the things but I know people brings food and we have a microwave and fridges where people bring their food and

cook and that so yeah is possible, it is not my case” –P1M

Thus, in all interviews, data linked to food-related spaces, facilities, equipment available within Swedish organizations had been collected. Additionally, participants positive and negative opinion about those food support and their influences had been revealed.

19

4.3 Available Food Options

The common food options identified within the participants’ company were frozen food, fresh cooked hot meals, salads, fruits, fika, snacks and soda and beverages such as coffee, tea and water. Within their organization, respondents P3M, P5F and P7F only have frozen food distributors for lunch. So, if the employees do not bring food from home or outside, the unique available option is to buy frozen food and heat it in the microwave. Thus, P5F stated she “always takes leftovers from dinner” for lunch. P3M stated buying frozen food half of the week and bringing food from home as there is no restaurants nearby the company. P7F stated eating leftovers from home or eating outside. However, P3M and P7F both stated having a “large variety of food” in the fridge. While, P10M stated having a restaurant within its company, with a large variety of food including healthy and vegetarian alternative, where he buys fresh cooked hot meals two to three times a week and bring food from home the rest of the days as there is no other option available:

“...The restaurant was built one year ago. So, before that we didn’t have a restaurant. Then we, then the only food option was to bring your own food so the everybody just brought their own food. Okay. But since they built the restaurant a

year ago, so of course, bigger, more options since we can essentially eat there…” – P10M

P8F has a frozen food distributor and a cafeteria where she can buy fresh-cooked meals with vegetarian options. Furthermore, positive and negative descriptions of food available in organizations had been identified. For instance, interviewees P6F showed a higher degree of satisfaction than other participants:

“You have a lot of different menus to choose from, so we have a salad buffet with cold food and it differs from day to day so you can go for the salad and then you weight your own salad so sometimes you can pay like 20 Swedish kronor and you will get full anyhow although it is very cheap lunch so either it is a salad buffet or hot meals, usually

two to choose between, or some already prepare salad or sandwiches…”

As certain participants explained, aspects such as variety, quantity and price were described as satisfaction elements. However, certain respondent was more critical about these same aspects as seen in P9F’s words:

“The food choice the restaurant down is not good, it could be a lot healthier and a lot more sustainable, meat, I think it could also challenge food norm, mmmm, a lot more,

yeah it is meat heavy and cream and not very nutritious, and I know a lot of my colleagues are, they are like this cost, and I understand that but they could also have

different options”

P8F also expressed her dissatisfaction about the food variety and stated that she prefers to eat outside when she does not bring food from home. Or, as P2M explained:

“At the restaurant they usually have one or two meat dishes, they usually have three dishes like one is vegetarian, one meat and they also take care of the allergies and

stuff, and they also have salad, and they have different salad, bread, quantity, and the food is very good but taste-wise sometimes not very good (laugh) so if you eat Monday

and Tuesday they have fresh food, and the other days left overs, they try to make it sustainable.”

Overall, all participants shown a degree of expectation of food availability at the workplace. In words of interviewee P10M: