Theses studies were financially supported

By

Ministry of Health

Saudi Arabia

3

Contents

page

Introduction

4

Aims

20

Paper I

22

Paper II

47

Acknowledgements

67

4

Introduction

5

Background

In a report by Dworkin et al (1990), American Dental Association has suggested the term

Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD) to describe a cluster of related disorders characterized by pain in the pre-auricular area, the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) or the muscles of mastication; limitation or deviation in the mandibular range of motion and noises in the TMJ during mandibular function. TMD is a collective term embracing a number of clinical problems that involve the masticatory musculature, the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) and associated structures, or both (McNeill 1993). Because there is no single agreed-upon definition for TMD as a global term, encompassing a variety of subtypes of the prevalence rates reported for TMD have varied widely (LeResche 1997).

Epidemiological studies of TMD have been published from different communities in the world. A survey of five common pain conditions, including pain in the temporomandibular region was conducted among a stratified random sample of population (1016) in Seattle Washington. The majority of the population of this study were between the ages of 25 and 44 years, Caucasian,

married, employed, and had at least some college education. Results from this age group showed that 10%men and 18% women reported pain in the TMJ or facial muscles in the prior six months (Von Korff et al 1988). Data were gathered as a part of the 1989 National Health interview, which was administered by telephone to a large, representative sample of the United States population to obtain national prevalence estimates of five oral facial pains in 18 years of age and older. Nearly 22% of the populations were estimated to have experienced at least one orofacial pain more than once during past six months. The highest rates were found in 18-34-years olds, and the rates decreased with age

(Lipton et al 1993).

One early TMD prevalence study conducted in the Arab World was performed by Abdel-Hakim (1983). It covered 215 male subjects from the Siwa oasis. The Siwian community is representative of the Bedouin communities in the Egyptian western desert. The population belongs to a characteristic ethnic group, living in a primitive way. The most prevalent symptoms were headache (29%), pain in the ear (24%) and clicking joint sounds (19%); 84% of the subjects suffered from tenderness of one or more of the masticatory muscles; 8% of the subjects had painful movements of the mandible. From the Saudi Arabian population more than ten studies have been published. In one publication by Jagger & Wood (1992), the aim was to determine signs and symptoms of TMJ dysfunction in 219

6

Saudi Arabians older than 16 years attending a dental clinic for routine dental treatment. The authors concluded that there was a high incidence of signs and symptoms of TMD. TMJ sounds (36%) and muscle tenderness to palpation (34%) was common findings. Of the subjects examined, 31% reported suffering from frequent headaches.

In a study by Nourallah & Johansson (1995), the prevalence of TMD was investigated in a group of selected young male Saudi population, 105 dental students with a mean age of 23 years (range of 20-29 years). The Helkimo anamnestic and clinical dysfunction index, (Helkimo 1974) was used, and around two-thirds of the individuals were found to have no signs and symptoms of TMD, 30%

reported mild symptoms (Ai I) and 6% severe symptoms (Ai II). One-third showed mild clinical signs of dysfunction (Di I) 3% moderate signs (Di II) and 1% severe clinical signs of dysfunction (Di III). In 1996 Abdel-Hakim et al sent a questionnaire to adolescents regarding symptoms of stomatognathic dysfunction, general health, peripheral joint diseases, chewing function, and oral parafunctions. Thirty-two per cent reported at least one symptom of dysfunction. Pain on opening was the most common 36%, followed by headache 34%, and joint sounds 32%. Symptoms increased with impaired general health, particularly health of peripheral joints.

In a study by Zulqarnain et al (1998), symptoms of TMD reported by 705 female university students of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, were analyzed. Eighty–eight percent of the subjects were Saudi citizens with a mean age of 21 years. Symptoms frequently reported were feeling of tiredness in the jaws (34%), awareness of uncomfortable bite (31%), pain in front of the ear (22%) and discomfort upon wide opening (22%). Symptoms frequently found were pain interfering with activity (42%), disturbed sleep (41%), medication (28%) and pain being frustrating or depressing (27%).

In a report of TMD prevalence in 502 children aged 3-7 years old, 17% presented TMD (4% males, 18 % females; P< 0.001). Eight percent of the children had TMJ sounds, 7% muscle tenderness, 3% pain during TMJ movement, 3% deviation of the mandible during movement and 2% restricted mouth opening. None of the children had sought treatment for these conditions. The authors

concluded that the importance of TMJ examinations in the overall clinical assessment of the pediatric patient should not be overlooked. (Alamoudi et al 1998)

In order to describe the prevalence of signs and symptoms of TMD in a group of patients seeking orthodontic treatment, Akeel & Al-Jasser (1999) examined 191 consecutive orthodontic female patients, divided into three age groups 8, 14 and 18 year. They were examined for TMD signs, symptoms, and the index of orthodontic treatment need (IOTN). The percentages of signs and

7

symptoms were 41% and 30%, respectively. No significant association was found between IOTN and TMD. Headache was associated with all TMD symptoms and tenderness to palpation. In conclusion, the results indicated that malocclusion could not be considered as a primary etiologic factor for TMD within the age range studied.

Prevalence of TMD signs as well as emotional status on the development of TMD among 696 female Saudi children aged 6 to 14 years was investigated in a study by Farsi (1999). The results showed that 17% of the children had at least one sign of TMD with joint sounds being the most frequent (14%), restricted mouth-opening second most in frequent sign (8%). Statistically significant differences in the prevalence of TMJ tenderness between the calm and nervous children suggested that children in emotional states run a greater risk of developing TMD signs.

Occlusal characteristics, signs, and symptoms of TMD in children with primary dentition were investigated in a group of 502 children 4-6 years olds (Alamoudi 2000). The results of this study showed significant correlation between signs and symptoms of TMD and some of the occlusal

characteristics including posterior cross-bite, edge to edge-bite, anterior open-bite and class III canine relationship and as well as asymmetrical canine relationship (canines on one side had a different relation from the ones in the contra lateral side). The study supported the previous conclusions about TMD being multifactorial and highlighted the importance of an early intervention to prevent further consequences for TMD and permanent occlusion.

Farsi & Alamoudi (2000) evaluated the prevalence of signs of TMD in children with and without premature loss of primary teeth. Fifty-eight children, aged 4-6 years, with missing primary molars, were compared with 58 age- and sex-matched control children with complete primary dentitions. There were no statistically significant differences in the prevalence of single or collective TMD signs between the two groups. The results of this study show that premature loss of primary teeth,

uncomplicated by other factors, does not appear to be an etiological factor for the development of TMD.

In another study published by Alamoudi (2001), the relationship between the subjective and objective symptoms of TMD, oral parafunctions, and emotional status were investigated. This study was based both on a questionnaire and clinical examination. Five hundred and two Saudi children aged 3 to 7 years old were examined for different signs and symptoms of TMD. In addition, the parents were given questionnaires to reveal the existence of oral parafunctions and evaluate the emotional status of the children being calm or nervous. The results of this study showed associations between attrition

8

and TMJ pain, muscle tenderness and restricted opening. Significant associations were found between the emotional status and multiple signs and symptoms of TMJ tenderness, TMJ pain and muscle tenderness.

Nassif et al (2003) performed a self administered questionnaire and screening examination were performed on 523 males with an age range of 18-25 years (mean age = 22.4) regarding TMD

symptoms. The screening examination was performed by extra oral examination and included range of jaw movement, digital palpation of selected masticatory muscles and palpation over the pre-auricular TMJ area and digital palpation for TMJ sounds during jaw movement. They reported that 59% had TMD symptoms and 50% had TMD signs. When combined, 75% of the subjects had TMD symptoms and/or signs. There were 7% insignificant moderate symptoms and/or signs, 51%

significant moderate symptoms and/or signs, and 17% severe symptoms and/or signs. It was

recommended that subjects with significant moderate and severe symptoms and/or signs should have a comprehensive TMD evaluation, in order to further identify the need for TMD therapy.

In another study by Farsi (2003), 1976 stratified selected schoolchildren aged 3-15 years, were divided into three groups, 505 with primary, 737 with mixed and 734 with permanent dentition. The prevalence of TMD signs was found to be 21% and the most common sign of TMD was joint sounds (12%). The second most common sign was restricted mouth opening capacity (5%). TMJ sounds were significantly increasing with age (P < 0.05). TMD symptoms as reported by the parents were evident in 24% of the returned questionnaires. The most common symptoms were headache (14%) and pain on chewing (11%). The incidence of headache was found to be significantly increasing from primary to permanent dentition (P < 0.01). No sex difference in the prevalence of any symptom was reported. Nail biting was the most common oral parafunction (28%) while bruxism was the least common (8 %). All parafunctions except bruxism were significantly related to age. Cheek biting and thumb sucking were reported more in females than in males. The author concluded that importance of a screening examination for symptoms and signs of TMD should not be overlooked in the clinical assessment of the pediatric patient.

Farsi et al (2004) investigated the relationship between oral parafunctions and TMD. A group of 1976 children aged 3-15 years old randomly selected, underwent an examination consisting of palpation and assessment of the TMJ and associated muscles for tenderness and joint sounds. Maximum vertical opening and deviation during jaw opening were recorded. The parents were requested to complete a questionnaire regarding symptoms of TMD and history of oral parafunctions. The results

9

showed significant correlations between cheeks biting, nail biting, bruxism, thumb sucking, and TMD signs and symptoms.

Table 1. Presentation of studies performed in Saudi Arabian population regarding TMD 10 METHOD STUDY NAME & POPULATION TYPE + GENDER Males (M) AIMS To AGE GROUP

Females (F) QUESTIONNAIRE CLINICAL EXAMINATION

SA MP LE SI ZE No.

(REFERENCE NO.) (Years) Investigate :

1 Jagger & Wood

219 ≥ 16 100 M & 119 F Dental patients

1992 (7) Yes Yes Signs & symptoms of TMD in Saudis

2 Nourallah & Johansson 1995

(9) 105 20 – 29 Dental students M Yes Yes The prevalence of TMD 3 Abdel-Hakim et al 1996(10)

330 14– 21 Secondary school 194 M & 136 F Yes No Symptoms of TMD

705 17- 33 University students Yes No

The prevalence of symptoms of bruxism & TMD and study any interaction between the symptoms and social environment factors Zulqarnain et al 1998 (11)

4

F

502 3-7 School children 235 M & 267 F

5 Alamoudi et al 1998 (12) No Yes The prevalence of signs & symptoms of TMD 6 Akeel & Aljasser 1999 (13) 191 8,14-18

18

Seeking orthodontic

treatment F Yes Yes The prevalence of signs & symptoms of TMD >

,

Yes Yes The prevalence of TMD signs and effect of emotional status on development of TMD 696 6-14 F children

7 Farsi 1999 (14)

502 4 - 6 Pre- school children No Yes The association between occlusal characteristics and signs & symptoms of TMD Alamoudi 2000 (15)

8 235 M & 267 F

116 4 - 6 Children Yes Yes Signs &symptoms of TMD in children with or without premature loss of primary teeth Farsi & Alamoudi 2000 (16)

9

502 3 - 7 Pre- school children Yes Yes The relationship between signs & symptoms of TMD and oral parafunction and emotional status

Alamoudi 2001 (17)

10 235 M & 267 F

523 18 - 25 Military students M Yes Yes -The prevalence of signs & symptoms of TMD Nassif et al 2003 (18)

11 - The relative significance of

TMD findings

1976 3 - 15 School children 1034 M Yes Yes The Prevalence of signs and symptoms of TMD and oral parafunctions

Farsi 2003 (19)

12 942 F

13 Farsi et al 2004 (20) 3 - 15 School children 1034 M

942 F

1976 Yes Yes The relationships between oral parafunctions and signs & symptoms of TMD among Saudi children.

11

These epidemiological studies performed in Saudi Arabia have been mainly examining signs and /or symptoms in relation to specific conditions such as parafunctional habits and occlusal characteristics. In the past, examining signs and symptoms was the preferred way to study epidemiology of TMD, due to the lack of knowledge of how to gather data in order to diagnose different subgroups of TMD. In addition, none of the above-mentioned studies was performed according to standardized diagnostic criteria of TMD.

In 1992 the research diagnostic criteria of TMD ( RDC/TMD ) were presented by Dworkin and LeResche (1992) .The RDC/TMD were primarily intended for research purposes , allowing

standardized methods for gathering relevant data and making possible comparison of findings and replication of research into the most common forms of muscle-and joint-related TMD among diverse clinical investigators.

The major attributes of the RDC/TMD making them especially valuable in clinical research settings are: (1) a carefully documented and standardized set of specifications for conducting a systematic clinical examination for TMD, (2) demonstrated reliability for these operationally defined clinical measurement methods, and (3) use of dual-axis system: Axis I to record clinical physical findings, and Axis II to record behavioral (e.g. mandibular functional disability), psychological (e.g.

depression somatization), and psychosocial status (e.g. chronic pain grade for assessing pain severity and life interference) through subjective self-report (Dworkin and LeResche, 1992) (Dworkin et al , 2002).The RDC/TMD Axis II is not intended to yield clinical psychiatric diagnosis. Instead, they assess the extent to which a person with TMD may be so cognitively, emotionally, or behaviorally impaired that these factors may contribute to the development or maintenance of the problem and/or interfere with smooth acceptance of and compliance with treatment. Depression is the psychological mood characterized by feelings of sadness, helplessness, hopelessness, guilt, despair, and futility, while somatization is the process whereby a mental condition is experienced as a bodily symptom (Okeson1996).

TMDs are placed within the same biopsychosocial model currently used to study and manage all common chronic pain conditions (Dworkin & Massoth 1994). The concept of chronic pain

dysfunction has emerged as a critical consideration for chronic pain research and management. Most chronic pain patients seem to bear their condition adequately and thus maintain adaptive levels of psychosocial function. By contrast, a psychosocially dysfunctional segment of the chronic pain population appears unable to cope as well and demonstrate higher rates of depression, somatization,

and health care use, even though persons in this segment are not different from their functional peers on the basis of observable organic pathology (Dworkin & Massoth 1994). Patients with TMD have been reported to have greater experimental pain perception when compared with pain-free controls. Common psychological features of TMD include somatization and depression (Sherman et al 2004). In a recent study, John et al (2005) investigating the reliability of assessment trials conducted at 10 international clinical centers, involving 30 clinical examiners by assessing 230 subjects. They concluded that the RDC/TMD demonstrated sufficiently high reliability for the most common TMD diagnoses, supporting its use in clinical research and in treatment decision making.

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia occupies most of the Arabian Peninsula, with an area of approximately 2,250,000 square kilometers (868,730 square miles) and is bounded on the north by Jordan, Iraq and Kuwait; on the east by the Gulf, Bahrain, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates; on the south by the Sultanate of Oman and Yemen; and on the west by the Red Sea.

The total population is 22.673.538 with 16.529.302 (72.9%) Saudis and 6.144.236 (27.1%) non-Saudis, 50.1 % males and 49.9 females. (National survey 2004)

Makkah (Mecca)

The Holy City of Makkah lies inland, 73 km east of Jeddah, in the narrow, sandy Valley of Abraham. The land consists of rugged, rocky (predominantly granite) terrain, with mountain ranges on three sides. It is 277 meters (909 feet) above sea level.

Makkah is the holiest city on Earth to Muslims. At least five times each day, the world's one billion Muslims, wherever they may be, turn to the Holy City of Makkah to pray toward the Ka’aba. Makkah is one of the biggest cities in the western region of the kingdom of Saudi Arabia, with 1.338.341 population (National survey 2004)

In the study by Abdul-Qader in 2004 (1424 H) the demographic, social, and economic characteristics of Makkah population were presented. The population in Makkah included 75% Saudi Arabians with 52% males and 48% females. The mean number of persons in a family was 5.2 people. Out of the total population, people without any education were 18% (22% females and 14 % males). Forty-nine percent of Makkah population were 19 years or less, 41% between 20-49 years old, and 10% were 50 years old or more. Totally 44% of Makkah people are less than 18 years old. Twenty seven percent were unemployed, out of which 18% had lost their jobs and 82% never had any job. Out of those, who had no job, 61% were males and 39% were females.

Dental Health Care System

In the kingdom of Saudi Arabia, dental health care services are divided into three levels:

The firstdental health care level is primary health care and is provided by dental clinics in the

primary health care centers (PHCC). In every city or town, there is many PHCC s according to the population in the area. Until December 2005, the total number of PHCCs in the whole area of Makkah is 72 centers and in every one there should be at least one dental chair.

The second level is the dental departments in the public hospitals, which receive complicated cases

that need help with diagnosis and managements. In every city, there are 2-4 secondary hospitals according to population in the area. In Makkah there are four public hospitals.

The third level is the specialist care presented by only one specialized dental center in every

city/area. This specialized dental center receives patients needing more specialized dental care referred from the dental departments in the public hospitals.

Makkah Specialist Dental Center

The dental center in Makkah city is accredited by Saudi Council for Health Specialties as a training center for specialist training of Saudi board students in the branch of restorative dentistry. It is also training center for dental technicians and dentists from other hospitals and PHCCs in Makkah city. It is the place of practical training and examinations for dental assistance students from the College of Nursing in Makkah.

The Dental Center is composed by 25 specialist dental chairs covering all specialties of dentistry. The available specialties are:

1- Oral diagnosis & oral radiology. 2- Oral & maxillo-facial surgery. 3- Restorative dentistry.

4- Endodontics. 5- Pedodontics.

6- Fixed prosthodontics.

7- Removable prosthodontics. 8- Periodontics.

9- Orthodontics. 10- Implantology. 11- Dental laboratory.

After registration in the reception, all referred patients examined in the screening & diagnosis clinic to confirm diagnosis and then referred to the appropriate specialist clinics.

References

1- Dworkin SF, Huggins KH, LeResche L, Von Korff M, Howard J, Truelove E, Sommers E.

Epidemiology of signs and symptoms in temporomandibular disorders:clinical signs in cases and controls. J Am Dent Assoc 1990;120:273-81.

2- McNeill C, editor. Temporomandibular disorders. Guidelines for classification, assessment and

management.Chicago:Quintessence 1993.p11-60.

3- Le Resche L. Epidemiology of temporomandibular disorders: implications for the investigation of

etiologic factors. Crit Rev oral Biol med 1997;8:291-305.

4- Von Korff M, Dworkin SF, Le Resche L, Kruger A. An epidemiologic comparison of pain

complaints. Pain.1988 Feb;32 (2):173-83.

5- Lipton JA, Ship JA, Larach-Robinson D. Estimated prevalence and distribution of reported

orofacial pain in the United States. J Am Dent Assoc 1993 Oct;124(10):115-21.

6- Abdel-Hakim AM. Stomatognathic dysfunction in the western desert of Egypt: an

epidemiological survey. J Oral Rehabil 1983 Nov;10(6):461-8.

7- Jagger, R.G. & Wood C. Signs and symptoms of temporomandibular joint dysfunction in a

Saudi Arabian population. J Oral Rehabil 1992;19:353-9.

8- Helkimo, M. Studies on function and dysfunction of the masticatory system II. Index for

anamnestic and clinical dysfunction and occlusal state. Sven Tandlak Tidskr 1974; 67:101-21.

9- Nourallah H, Johansson A. Prevalence of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders

in a young male Saudi population. J Oral Rehabil 1995;22:343-7. 16

10- Abdel-Hakim AM, Alsalem A, Khan N. Stomatognathic dysfunctional symptoms in Saudi

Arabian adolescents.J Oral Rehabil 1996;23:655-61.

11- Zulqarnain BJ, Khan N, Khattab S. Self-reported symptoms of temporomandibular

dysfunction in a female university student population in Saudi Arabia. J Oral Rehabil 1998;25:946-53.

12- Alamoudi N, Farsi N, Salako NO, Feteih R. Temporomandibular disorders among

schoolchildren. J Clin Pediatr Dent 1998;22:323-8.

13- Akeel R, Al-Jasser N.Temporomandibular disorders in Saudi females seeking orthodontic

treatment. J Oral Rehabil 1999;26:757-62.

14- Farsi NM. Temporomandibular dysfunction and the emptional status of 6-14 years old Saudi

female children. Saudi Dental J 1999;11:114-19.

15- Alamoudi N. The correlation between occlusal characteristics and temporomandibular

dysfunction in Saudi Arabian children. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2000;24:229-36.

16- Farsi NM, Alamoudi N. Relationship between premature loss of primary teeth and the

development of temporomandibular disorders in children. Int J Paediatr Dent 2000;10:57-62.

17- Alamoudi N. Correlation between oral parafunction and temporomandibular disorders and

emotional status among Saudi children. J Clin Pediatr Dent.2001;26:71-80.

18- Nassif NJ, Al-Salleeh F, Al-Admawi M. The prevalence and treatment needs of symptoms and

signs of temporomandibular disorders among young adult males. J Oral Rehabil 2003;30:944-50.

19- Farsi NM. Symptoms and signs of temporomandibular disorders and oral parafunctions among

Saudi children. J Oral Rehabil 2003;30:1200-8.

20- Farsi N, Alamoudi N, Feteih R, El-Kateb M. Association between temporomandibular

disorders and oral parafunctions in Saudi children. Odontostomatol Trop 2004;27:9-14.

21- Dworkin SF, LeResche L. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders:

review, criteria, examinations and specifications,critique. J Craniomandib Disord 1992;6:301-55.

22- Dworkin SF, Sherman J, Mancl L, Ohrbach R, LeResche L, Truelove E. Reliability,

validity, and clinical utility of the research diagnostic criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders Axis II Scales: depression, non-specific physical symptoms, and graded chronic pain. J Orofac Pain

2002;16:207-20.

23- Okeson JP, eds. Orofacial Pain. Guidelines for Assessment, Diagnosis and Management.

Chicago: Quintessence, 1996.

24- Dworkin SF, Massoth DL. Temporomandibular disorders and chronic pain: disease or illness?. J

Prosthet Dent 1994;72:29-38.

25- Sherman JJ, LeResche L, Huggins KH, Mancl LA, Sage JC, Dworkin SF. The relationship of

somatization and depression to experimental pain response in women with temporomandibular disorders. Psychosom Med 2004;66:852-60.

26- John MT, Dworkin SF, Mancl LA. Reliability of clinical temporomandibular disorder

diagnoses. Pain 2005 Sep 8; [Epub ahead of print].

27- Abdul-Qader A., Studying the Demographic, Social and Economic Characteristics of

Makkah Al-Mukaramah Population. Study survey (2004/1424 H); on the website of the High Commission For The Development of Makkah Province.

http://www.makkah-development.gov.sa/hcm/3/3-5/3-5-2.htm. (Retrieved at 2006-05-09).

28- National survey done September (2004) by the Ministry of planning / Saudi Arabia.

http://www.cds.gov.sa/statistic/index.htm (Retrieved at 2006-09-09).

29- List T, Dworkin SF. Comparing TMD diagnoses and clinical findings at Swedish and US

TMD centers using research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders. J Orofac Pain 1996 Summer;10(3):240-53.

30- Dworkin SF, LeResche L, DeRouen T, Von Korff M. Assessing clinical signs of

temporomandibular disorders: reliability of clinical examiners. J Prosthet Dent 1990 May;63(5):574.

Aims

Specific Aims

The aims of this thesis are the following:

1- To examine the frequencies of pain related TMD among adults (20 -40 years old) referred to

a specialist clinic in Makkah, Saudi Arabia by using RDC/TMD. (Paper I)

2- To compare pain related TMD symptoms in patients with and without TMD pain. (Paper I)

3- To examine the frequencies of clinical findings and subdiagnoses of TMD according to RDC/TMD

specifications in a group of adult (20-40 years old) Saudi Arabians reporting pain related TMD.

(Paper II)

Paper I

Pain Related Temporomandibular Disorders in Adult Saudi Arabians Referred For Specialized Dental Treatment

Mohammad H. Al-Harthy 1,2, EwaCarin Ekberg 2, and Maria Nilner 2

1 Dental Center , Al-Noor Specialist Hospital, Holy Makkah, Saudi Arabia

2 Department of Stomatognathic Physiology, Faculty of Odontology, Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden.

Abstract

The aim of the present study was to examine the frequencies of pain-related symptoms of TMD in patients in the age of 20-40 years referred for specialized dental treatments in Makkah, Saudi Arabia by using Research Diagnostic Criteria for TMD (RDC/TMD).

Three hundred and twenty-five consecutive Saudi patients in the age of 20-40 years; 135 males and 190 females were interviewed according to the RDC/TMD history questionnaire. The results revealed that pain related TMD and orofacial pain were found among 58 (18%) patients. All other patients formed the non-pain group (267, 82%). In the pain group, there were 79% females compared to 21% males (P < 0.001).

Both genders in the pain group reported high frequencies of both migraines in the last six months and headache moderately to extremely in the last month showing significant difference in comparison with the non-pain group (P < 0.001). Symptoms of TMD were significantly more prevalent in the pain group than in the non-pain group. The most common pain related TMD symptoms were TMJ clicking, TMJ crepitation, TMJ locking, stiff jaw, tinnitus, bruxism, and uncomfortable bite. Regarding Graded Chronic Pain severity in the pain group, most patients reported their pain to be grade I and II. Jaw disability checklist according to RDC/TMDshowed that four or more disturbed jaw activities were found in 31 patients (53%) while 13 patients (22%) had not affected mandibular functions.

In conclusion, the findings of the present study showed high frequencies of pain related TMD in this Saudi Arabian patient population.

Introduction

Epidemiological studies on temporomandibular disorders (TMD) and orofacial pain have been performed in several countries around the world. In 1988, a survey of five common pain conditions, including pain in the temporomandibular region was conducted in a stratified random sample of the population in Seattle Washington.1 The majority of the populations of this study were between the ages of 25 and 44. They found that 8% of the men and 15% of the women reported pain in the temporomandibular joint or facial muscles in the prior six months.

A National Health interview was made on a large, representative sample of the United States

population in 1989 to obtain national prevalence estimates of five oral facial pains in 18 years of age and older. Nearly 22% of the populations were estimated to have experienced at least one orofacial pain more than once during past six months. The highest rates of orofacial pain were found between 18-34 years of age.2 In an epidemiological review study it was found that pain in the

temporomandibular region appears to be relatively common, occurring in approximately 10% of the population over the age of 18 years; it is primarily a condition of young and middle-aged adults, rather than of children or the elderly, and is approximately twice as common in women as in men.3 Several epidemiological studies of TMD have been performed in Arabian countries.4-17 Some of them included populations 20 years of age and above.4-8, 10 In one study which focused on a population of 20-29 years old male dental students in Saudi Arabia it was found that, around two-thirds of them had no signs and symptoms of TMD. Mild symptoms were reported in 30% and severe symptoms in 6%. No TMD diagnoses were presented in this study.6 The aim of the present study was to examine the frequencies of pain related TMD among adults (20-40 years old) referred to a specialist clinic in Makkah, Saudi Arabia by using RDC/TMD. Another aim was to compare pain-related TMD symptoms in patients with and without TMD pain

Patients and Methods

Patients

Patients referred to the Specialist Dental Centre in Alnoor Specialist Hospital in Makkah, Saudi Arabia 3 days a week during October and November 2005 were invited to take part in the study. Three hundred and thirty five consecutive Saudi patients in the age of 20-40 years were asked to take part in the study. This specialist dental centre has 25 dental chairs covering many specialties of dentistry. It receives referrals from general dental clinics in primary health care centers and dental departments in the secondary health care hospitals.

Out of the 335, 10 patients declined to participate due to that they either had no time for the

interview, or that they were suffering from acute dental pain or that they could not communicate well enough for the interview. The total number of participating patients in the study was 325 and Table 1 presents the distribution of age and gender.

Methods

All patients were given information about the study and asked to participate. They were informed that if they did not participate it would not influence their care at the centre. Official approval to start the study had been taken from the director of the health affairs in Makkah, Saudi Arabia.

The patients were interviewed according to an Arabic version of RDC/TMD18 by two trained dentists. A few questions were deleted or modified to make the history questionnaire accepted in the Saudi (Arabic-Muslim) culture. These questions were about sexual activities, thinking of death or dying as well as awakening early in the morning. The modifications of these questions did not affect the main idea of the questions or RDC/TMD diagnostic criteria. These modifications will be discussed

elsewhere.

A secretary in the dental centre was assigned to take the patients from the Diagnosis Clinic to the Radiology Department. During film processing the interview took part in a separate room. Due to

cultural reasons, a female dentist was trained to perform the interviews with female patients as otherwise their husbands or male relatives insisted to attend the interview.

Patients included in the interview according to the following inclusion criteria: • 20-40 years old.

• being able to communicate in an interview.

A subgroup of TMD related pain was formed according to the following criteria:

⊚ reported pain in the face, jaw, temple, in front of the ear or in the ear in the past month. ⊚ reported worst orofacial pain in the last six months that were more than 0 on the

Numeric Rating Scale (NRS).

⊚ reported average usual orofacial pain at times of its experience in the last six months that were more than 0 on the NRS.

Results

Three hundred and twenty-five patients included in this study had a mean age of 28.7 years ± 6 (S.D.). One hundred and thirty-five (42%) male patients had a mean age of 29 years ± 6 (S.D.) and 190 (58%) female patients had a mean age of 28.5 years ± 6 (S.D.). The male: female ratio was 1: 1.4. Patients in the age group from 20-24 years from both genders were the highest frequency 32% (104). A subdivision of the patients into pain and non-pain groups with respect to age and gender is shown in Table 1.

Most of the patients were Arabians 268 (82.5%). The distributions of national origins or ancestries are shown in fig. 1.

Education:

Fifty-two percent (168) of all patients had received more than 12 years of education, out of them 83 (49%) were males and 85 (51%) were females. The frequency of those who had not received any education was 17 (5%) and all females. Table 2 shows the educational levels of the 325 patients in the two subgroups pain and non-pain.

Income:

Total combined household incomes during the last 12 months medium (25.000–34.000 $) to high (35.000–50.000) were more frequent in the groups without significant difference between the pain and non-pain groups (Table 3).

Marital Status:

Most of the patients were either married-living in household 171 (52%) or never married 139 (43%). Fifteen patients (5%) from the total number of participants were separated, divorced, widowed, or married-spouse not in household. Table 4 shows the distribution of marital status and gender in different age groups. The last mentioned 15 patients are considered as non-married due to both their resemblance to married status and by living without spouse. In Table 5, the married and non-married males and females patients are subdivided into pain and non-pain groups without any significant difference between marital status and pain or non-pain.

General and Oral Health:

All patients graded their general and oral health according to their own opinions from excellent to poor. Most of the patients (98%) considered themselves to be in good to excellent general health without any difference between the genders or groups. Oral health was considered to be good to excellent by 86% of all patients without any differences between genders, see Table 6.

Headache and Migraine:

The pain group from both genders reported high frequencies of both migraines in the last six months and moderately to extremely headache in the last month showing significant difference in comparison with the non-pain group (P < 0.001) as shown in Table 7.

Pain and Non-Pain Groups:

The pain group comprised 58 (18%) patients according to the inclusion criteria of the subgroup. All other patients formed the non-pain group (267, 82%). Females reporting orofacial pain were 79% compared to 21% males (P < 0.001). The non-pain group comprised 54% females and 46% males. Forty-nine patients (84%) were suffering from recurrent orofacial pain, 7 patients (12%), from persistent pain and 2 (3%) patients had experienced this kind of pain once.

Regarding doctor visit, 64% (37) had never visited a health professional to get help with their orofacial pain. In the last 6 months, 16 (27%) visited a doctor, and 5 (9%) visited more than 6 months ago a health professional.

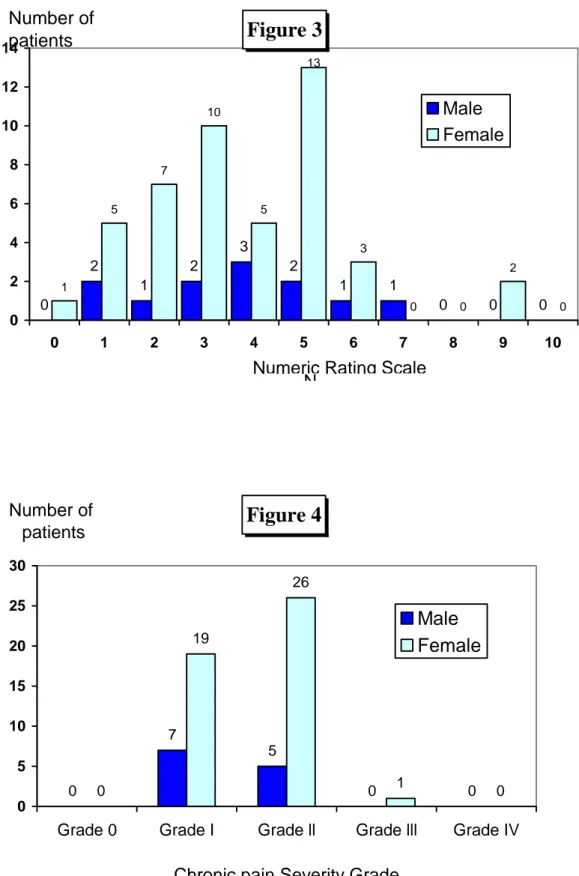

Worst orofacial pain in the last six months in 90% (52) patients of the pain group was rated 5 or more on the NRS as shown in fig.2. Ninety-three percent (54) patients rated their usual orofacial pain at times of its experience in the last six months between 1 and 6 on the NRS (figure. 3).

Nineteen percent of the pain group had not been absent from their usual activities (work, school or housework) because of the oro-facial pain, 5 patients (9%) had been absent one day, and 6 patients (10%) 2 days or more. Twenty-seven patients (47%) stated that the orofacial pain did not interfere with their daily activities. Thirty patients (52%) reported that the orofacial pain did not change the ability to take part in social and family activities, and 36 patients (62%) reported that their orofacial pain did not change the ability to work.

Symptoms of TMD were significantly more prevalent in the pain group than in the non-pain group. The percentage distribution of TMD symptoms in both the orofacial pain and non-pain groups are shown in Table 8.

Graded Chronic Pain severity in the pain group for both genders is shown in Fig.4 and showed that most patients reported their pain to be grade I and II.

Jaw disability checklist according to RDC/TMD18 showed that four or more disturbed jaw activities were found in 31 patients (53%) while 13 patients (22%) had no affected on the mandibular functions (Figure 5).

Discussion

The results of this study showed a frequency of symptoms of TMD and orofacial pain that was 18%, a figure that is higher than has been reported in population’s studies 2, 18, 19 but in accordance with Magnusson et al 21 who reported 27%.

The male-female ratio in the pain group was in accordance with the ratio in the study by Anastassak &Magnusson 22, Yap et al 23 and Reiter et a l 24 who presented a ratio of 1:3 to 1:5. The number of women has, however been found to be even higher in pain patients.21-25 Although the difference in TMD prevalence between males and females is still not well understood, some theories have been proposed to explain why females are more affected than males.26 In many studies, TMD pain has been found to be 1.5 to 2 times more common in women than men and gender differences in pain report can be attributed to a number reasons: of biologic, occupational, psychologic, and social factors.4,27 Interestingly, some researchers stated that variations in estimated prevalence rate of reported pain symptoms suggest that various sociodemographic characteristics may be related to the onset, course or outcome of particular types of orofacial pain. In addition to gender, possible factors may include age, race/ethnicity, and place of residence.2

The patients visiting the Specialist Dental Centre in Makkah, Saudi Arabia were referred for specialized dental treatments from primary health care dental clinics and dental departments in secondary care hospital.

Many dental specialties were available except for a specialist in TMD and orofacial pain. Therefore, it was decided to include all consecutive patients in the study within the age span of 20-40 years which has been shown in several studies to be the age at which TMD pain has its peak of frequencies in the general population. 24

At the interview of the second patient, it was noticed that the patient was answering most of the questions negatively and without thinking. This was probably due to a feeling of shame especially when answering depression and somatization questions in the presence of at least five persons in the clinic in the same time (diagnoses clinic dentist, training dentist, dental assistance, training dental assistance, and interviewing dentist). It was therefore decided to interview patients who met the inclusion criteria in a separate room. It was, however, also noticed from the first female patient who

was accompanied by her husband that she felt uncomfortable and answered the questions negatively, especially when answering the questions about depression and somatization. When a husband insisted to attend the interview it was carried out with the help of a trained female dentist.

Married patients did not show higher values in TMD symptoms in comparison to non-married ones. Even if the married females in the pain group presented the highest percent (57%) among all groups, there was no difference and this is in disagreement with a previous study done on Saudi university females in another region of the country in which many TMD symptoms were significantly higher in married females.8

Education in Saudi Arabia is free and the percentages of patients in both the pain and non-pain groups having 12 years of education or more were high. In the pain group 45% and in the non-pain group 53% had an education of ≥12 years. These results disagree with data reported in an earlier study from Al-Ahsa province in the east region of Saudi Arabia.28 They reported university education of 14% and 21% in the TMD and control groups respectively.28 Illiterates in the present study were only females with a percentage of 5%, while in the last mentioned study they reported total of 18% and 8% illiterate people from both TMD group and control group respectively 28 and these differences may be due to the absence of a university in Al-Ahsa province in contrast to two universities in

Makkah province.

Migraine in the last six months in this study was frequent in women (47%) twice that in men (25%) and these findings are in accordance with other studies 21, 29 and agree with a discussion study

regarding frequency of migraine without aura.27 However, more information from the patients needed in the history questionnaires of RDC/TMD 18 about the nature, onset, location as well as duration of headache and/or migraine to confirm diagnosis. This may explain the high figures of migraine reported by the patients in the present study in comparison with low reported findings of a specific diagnosed headache in a study done on Saudi population in another region of the country.30 Headache within the last month in pain group were significantly higher than in non-pain group in this study. In addition, this is in agreement with many studies, which mentioned high frequencies of headache and/or had been considering headache as a symptom of TMD.4, 5, 8, 15, 21, 31 It seems to be due to cultural behavior in headaches pain expressions.

The frequencies of TMD symptoms were found to be statistically significantly different between the pain and non-pain groups regarding all symptoms studied. Regardless the methods of data collection

by the past studies done on Saudi people above the age of 18 years old, a presentation of frequencies of TMD symptoms in these studies 5, 6, 8, 10, 15 and the present study is presented in Table 9.

The frequency of chronic pain severity grade scores for females in the pain group were 57% in grade II followed by 41% in grade I and only one female patient with grade III and none in grade IV. These scores of Saudi Arabian females were in disagreement with scores of pain grade severity of Arabian females in another study.24 In the last mentioned study, they used RDC/TMD and found Arabian females in the grade III followed by nearly equal scores of both grade II and I. This difference between our study and this studycan be perhaps possibly explained by the more stable and secure lives of Saudi Arabian females. When comparing our findings with those of a study done in other non-Arab Asian community, we found no difference in the chronic pain severity grade scores distribution.23

In conclusion, the findings of the present study showed high frequencies of pain related TMD in this Saudi Arabian population. A consequence of the results and that in Saudi Arabia today there is no special clinics for treating patients with TMD, there is a need to start revaluations of future plans in the field of TMD and orofacial pain from the health workers and decision makers in the country. To the author’s knowledge, this is the first paper using RDC/TMD history questionnaire in Saudi Arabia and this will make it possible to compare with TMD prevalence in other communities.

Acknowledgments

The

authors wish to extend their warm thanks to Dr.Linda Mirza for her help in interviewing some female patients and to the former director of the Specialist Dental Center in Alnoor Hospital Dr. Mohammad Wahbi for his assistance before and during the study conduction, and to secretary Nor Haya for her guidance of patients before the interviews and for all staff of the centre.Figure legends

- Figure 1: Distribution of different national origins or ancestries in the study population of 325

patients.

-

Figure 2: Distribution of worst orofacial pain rated by the pain group (58 patients) in the last 6months rated on the NRS.

- Figure 3: Distribution of usual orofacial pain at times of its experience in the last 6 months rated by

58 patients on the NRS.

- Figure 4: Distribution of chronic pain severity grades with regard to gender in 58 TMD pain

patients according to RDC/TMD 18:

- Grade 0= No TMD pain in the prior 6 months - Grade l = Low Disability-Low Pain Intensity - Grade II = Low Disability-High Pain Intensity - Grade III = High Disability-Moderately Limiting - Grade IV= High Disability-Severely Limiting,

- Figure 5: Distribution of mandibular activities that were affected by TMD pain according to jaw

disability checklist in 58 TMD pain patients.

Figure 1

157 24 8 1 111 22 2 0 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180Arabian Asian Black White

National Origin / Ancestry Number of patients Male Female

Figure 2

0 0 0 2 0 1 2 2 3 1 1 0 1 0 1 2 6 4 4 10 3 15 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Numeric Rating ScaleWorst pain in the Number of

patients

Male Female

Figure 3

0 2 1 2 3 2 1 1 0 0 0 1 5 7 10 5 3 0 0 2 0 13 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 N Number of patients Male FemaleNumeric Rating Scale

Figure 4

0 7 5 0 0 0 19 26 1 0 0 5 10 15 20 25 30Grade 0 Grade I Grade ll Grade lll Grade IV

Chronic pain Severity Grade Number of

patients

Male Female

36 Figure 5 13 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 Number of patients 7 7 10 6 3 5 7 0 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Males Females

Pain (n=12) Non-pain (n=123) (n=135) Total Pain (n=46) Non-pain (n=144) (n=190) TotalTotal

Pain (n=58)Total

non-pain (n=267)Grand Total

n=325 Age Groups (Years) n % n % n % n % n % n % n % n % n % 20 – 24 4 33 36 30 40 30 11 24 53 37 64 34 15 26 89 33 104 32 25 – 29 2 17 31 25 33 24 12 26 37 25 49 26 14 24 68 26 82 25 30 – 34 5 42 25 20 30 22 5 11 24 17 29 15 10 17 49 18 59 18 35 – 40 1 8 31 25 32 24 18 39 30 21 48 25 19 33 61 23 80 25⊚ Table 1. Distribution of age groups with respect to gender, Pain / Non-Pain groups in 325 patients.

⊚ Table 2. Years of education of both genders among Pain and Non-Pain groups (n=325).

⊚ Table 3. Total combined household income during the last 12 months for both genders among Pain and Non-Pain groups (n=325).

Pain Group Males Females Non-Pain Group Males Females (n=12) (n=46) Total (n=58) (n=123) (n=144) Total (n=267) Income n % n % n % n % n % n % Very low 1 8 1 2 2 3 2 2 6 4 8 3 Low - - 4 9 4 7 - - 16 11 16 6 Medium 3 25 16 35 19 33 29 23 49 34 78 29 High 3 25 20 43 23 40 53 43 54 38 107 40 Very high 5 42 5 11 10 17 39 32 19 13 58 22

Very low = 0-14.999 $ , Low = 15,000-24,999 $ , Medium = 25.000-34,999$ , High = 35,000-50,000$ , Very high = ≥ 50,000$ according to RDC/TMD17.

Pain Group Non-Pain Group

Males Females (n=46) Total (n=58) Males (n=123) Females Total (n=12) (n=144) (n=267) Years Of Education n % n % n % n % n % n % 0 - - 5 11 5 9 - - 12 8 12 4 1 – 8 1 8 11 24 12 20 13 10 29 20 42 16 9 – 12 4 33 11 24 15 26 34 28 37 26 71 27 > 12 7 59 19 41 26 45 76 62 66 46 142 53 38

⊚ Table 4. Marital Status, gender and age groups. Percentages of subgroups in relation to total males(n=135) and females (n=190). (M= Males, F=Females)

Years of Age

20–24 (n=104) 25–29 (n=82) 30–34 (n=59) 35–40Total

(n=80) (n=325) Marital status n % n % n % n % n % M 2 1 9 7 25 19 29 21 65 20 Married spouse (in household) F 15 8 26 14 22 12 43 23 106 33 M 36 27 20 15 4 3 2 1 62 19 Never Married F 48 25 21 11 5 3 3 1 77 24 M 2 1 4 3 1 1 1 1 8 2 Married spouse ( not household) F 1 0.5 - - - - - - 1 0.3 M - - - - - - - - - - Widowed F - - - - - - 1 0.5 1 0.3 M - - - - - - - - - - Divorced F - - 2 1 2 1 - - 4 1 M - - - - - - - - - - Separated F - - - - - - 1 0.5 1 0.3⊚ Table 5. Distribution of Pain and Non-Pain groups with marital status for both genders (n=325). (Married spouse not living in household widowed, divorced and separated were included in non-married).

Pain Group

Non-pain Group

Males (n=12) Females (n=46)

Total

(n=58) Males (n=123) Females (n=144)Total

(n=267)Total

Males (n=135)Total

Females (n=190) Marital status n % n % n % n % n % n % n % n % Married 5 42 26 57 31 53 60 49 80 56 140 52 65 48 106 56 Non-married 7 58 20 43 27 47 63 51 64 44 127 48 70 52 84 44 39⊚Table 6. Reported general and oral health of both genders among Pain and Non- Pain groups (n=325).

Pain Group

Non-Pain Group

Males (n=12) Females (n=46)

Total

Total

Males Females (n=144) (n=58) (n=123)(n=267) n % n % n % n % n % n %

General health grade

Good – Excellent 11 92 44 96 55 95 123 100 140 97 263 99

Fair – Poor 1 8 2 4 3 5 - - 4 3 4 1

Oral health grade

Good – Excellent 11 92 36 78 47 81 104 85 125 87 229 86

Fair – Poor 1 8 10 22 11 19 19 15 19 13 38 14

⊚ Table 7. Distribution of reported migraine in the last six months and headache in the last month in both genders among Pain and Non-Pain groups (n=325).

Chi-square: * = <0.05, ** = <0.01, *** = <0.001

Pain Group

Non-Pain Group

Males (n=12) Females (n=46) Males Females (n=144)

Total

(pain) (n=58)Total

(non-pain) (n=123) (n=267) n % n % n % n % n % n % Significance level Migraine 11 92 43 94 72 59 110 76 54 93 182 68 *** Headache: - Moderately – Extremely 6 50 35 76 24 20 51 71 41 71 75 28 *** A little bit 5 42 8 17 53 43 51 22 13 22 104 39 - 40⊚ Table 8. Distribution of percentages of TMD symptoms in the Pain and Non-Pain groups. Pain Group (n=58)

Non-Pain

(n=267) (n=325Total

) TMD SYMPTOMS n % n % Significance level n % TMJ lock 32 55 25 9.4 *** 57 18 TMJ clicking 31 53 59 22 *** 90 28 Stiff jaw 29 50 26 10 *** 55 17 Crepitation 18 31 20 8 *** 38 12 Tinnitus 35 60 80 30 *** 115 35 Bruxism: daytime 27 47 37 14 *** 64 20 sleeping 23 40 35 13 *** 58 18 Chi-square: * = <0.05, ** = <0.01, *** = <0.001 Uncomfortable bite 27 47 58 22 *** 85 26 41⊚ Table 9. Presentation of frequencies of TMD symptoms in studies performed in young adult Saudi Arabian population.

Study name:

Sample size Jagger& Wood (1992) (n=219) Nourallah & Johansson (1995) (n=105) Zulqarnain et al (1998) (n=705) Akeel & Al-Jasser (1999) (n=191) Nassif et al (2003) (n=523) Present Study (2007) (n=325) 18 18-25 20–40 Age (years) ≥ 16 20-29 17-33 > TMD Symptoms (%): Headache 31 - 31 12 12 36 28 TMJ noise / Clicking 15 34 4 19 16 18TMJ Pain/Painful mouth opening 8 2 22 18 17

18

Opening difficulty / Jaw lock 5 4 13 9 14

Bruxism - - 10 - 6 19

26

Uncomfortable bite - - 31 - 18

Clenching - - 27 - - 20

References

1- Von Korff M, Dworkin SF, Le Resche L, Kruger A. An epidemiologic comparison of pain

complaints. Pain 1988 Feb; 32(2):173-83.

2- Lipton JA, Ship JA, Larach-Robinson D. Estimated prevalence and distribution of reported

orofacial pain in the United States. J Am Dent Assoc 1993 Oct;124(10):115-21.

3- LeResche L. Epidemiology of temporomandibular disorders: implications for the investigation of

etiologic factors. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 1997;8(3):291-305.

4- Abdel-Hakim AM. Stomatognathic dysfunction in the western desert of Egypt: an

epidemiological survey. J Oral Rehabil 1983 Nov;10(6):461-8.

5- Jagger, R.G. & Wood C. Signs and symptoms of temporomandibular joint dysfunction in a

Saudi Arabian population.J Of Oral Rehabil 1992;19:353-9.

6- Nourallah H, Johansson A. Prevalence of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders

in a young male Saudi population. J Oral Rehabil 1995;22:343-7.

7- Abdel-Hakim AM, Alsalem A, Khan N. Stomatognathic dysfunctional symptoms in Saudi

Arabian adolescents.J Oral Rehabil 1996;23:655-61.

8- Zulqarnain BJ, Khan N, Khattab S. Self-reported symptoms of temporomandibular dysfunction

in a female university student population in Saudi Arabia. J Oral Rehabil 1998;25:946-53.

9- Alamoudi N, Farsi N, Salako NO, Feteih R. Temporomandibular disorders among

schoolchildren. J Clin Pediatr Dent 1998;22:323-8. 43

10- Akeel R & Al-Jasser N.Temporomandibular disorders in saudi females seeking orthodontic

treatment. J Oral Rehabil 1999;26:757-62.

11- Farsi NM. Temporomandibular dysfunction and the emotional status of 6-14 years old Saudi

female children. Saudi Dental J 1999;11:114-9.

12- Alamoudi N. The correlation between occlusal characteristics and temporomandibular

dysfunction in Saudi Arabian children. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2000;24: 229-36.

13- Farsi NM & Alamoudi N. Relationship between premature loss of primary teeth and the

development of temporomandibular disorders in children. Int J Paediatr Dent 2000;10:57-62.

14- Alamoudi N. Correlation between oral parafunction and temporomandibular disorders and

emotional status among Saudi children. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2001;26:71-80.

15- Nassif NJ, Al-Salleeh F, Al-Admawi M. The prevalence and treatment needs of symptoms and

signs of temporomandibular disorders among young adult males. J Oral Rehabil 2003;30:944-50.

16- Farsi NM. Symptoms and signs of temporomandibular disorders and oral parafunctions among

Saudi children. J Oral Rehabil 2003;30:1200-8.

17- Farsi N, Alamoudi N, Feteih R, El-Kateb M. Association between temporomandibular

disorders and oral parafunctions in Saudi children. Odontostomatol Trop 2004;27:9-14.

18- Dworkin SF, LeResche L. Research diagnostic criteria fo temporomandibular disorders: review,

criteria, examinations and specifications,critique. J Craniomandib Disord 1992;6:301-55.

19- De Kanter RJ, Truin GJ, Burgersdijk RC, Van 't Hof MA, Battistuzzi PG, Kalsbeek H, Kayser AF. Prevalence in the Dutch adult population and a meta-analysis of signs and symptoms of

temporomandibular disorder. J Dent Res 1993 Nov;72(11):1509-18.

20- Dworkin SF, Huggins KH, LeResche L, Von Korff M, Howard J, Truelove E, Sommers E.

Epidemiology of signs and symptoms in temporomandibular disorders: clinical signs in cases and controls. J Am Dent Assoc 1990 Mar;120(3):273-81

21- Magnusson T, Carlsson GE. Comparison between two groups of patients in respect of headache

and mandibular dysfunction. Swed Dent J 1978;2(3):85-92.

22- Anastassaki A, Magnusson T. Patients referred to a specialist clinic because of suspected

temporomandibular disorders: a survey of 3194 patients in respect of diagnoses, treatments, and treatment outcome. Acta Odontol Scand 2004 Aug;62(4):183-92.

23- Yap AU, Dworkin SF, Chua EK, List T, Tan KB, Tan HH. Prevalence of temporomandibular

disorder subtypes, psychologic distress, and psychosocial dysfunction in Asian patients. J Orofac Pain 2003;17:21-8.

24- Reiter S, Gravish A, Winocur E. Ethnic Differences in Temporormandibular Disorders

Between Jewish and Arab Population in Israeal According to RDC/TMD Evaluation. J Orofac Pain 2006;20:36–42.

25- Pedroni CR, De Oliveira AS, Guaratini MI. Prevalence study of signs and symptoms of

temporomandibular disorders in university students. J Oral Rehabil 2003 Mar;30(3):283-9.

26- Conti PC, Ferreira PM, Pegoraro LF, Conti JV, Salvador MC. A cross-sectional study of

prevalence and etiology of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in high school and university students. J Orofac Pain 1996 Summer;10(3):254-62.

27- Dao TT, LeResche L. Gender differences in pain. J Orofac Pain 2000 Summer;14(3):169-84;

discussion 184-95.

28- El-Amin E I, Khalid M A, Ali SE. Temporomandibular Disorders in Al-Ahsa province, KSA:

An epidemiologic study. Saudi Dent J 2001; 13:133-8.

29- Agerberg G, Inkapool I. Craniomandibular disorders in an urban Swedish population. J

Craniomandib Disord 1990 Summer;4(3):154-64

30- Abduljabbar M, Ogunniyi A, al Balla S, Alballaa S, al-Dalaan A. Prevalence of primary

headache syndrome in adults in the Qassim region of Saudi Arabia.. Headache 1996 Jun;36(6):385-8.

31- Nassif NJ,Talic YF. Classic symptoms in temporomandibular disorder patients: a comparative

study. Cranio 2001 Jan;19(1):33-4.

47

Paper I I

48

Diagnoses and Clinical Findings of TMD according to Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders in 20-40 years old Saudi Arabians

Mohammad H. Al-Harthy 1,2, Maria Nilner 2, and EwaCarin Ekberg 2

1 Dental Center , Al-Noor Specialist Hospital, Holy Makkah, Saudi Arabia

2 Department of Stomatognathic Physiology, Faculty of Odontology, Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden.

Abstract

The aim of this study was to examine the frequencies of clinical findings and subdiagnoses of TMD according to RDC/TMD specifications in a group of adult (20-40 years old) Saudi Arabians reporting pain related TMD. Forty-six patients clinically examined had a mean age of 30 years ± 6.6 (S.D.).. The male: female ratio was 1: 5.6.

TMJ pain on both sides during maximum unassisted and assisted openings was common with the percentages 52% and 48% respectively. Muscles pain from both sides during maximum unassisted opening and maximum assisted opening was 46% and 44% respectively. Different kinds of sounds from TMJ were registered only in females while only one male patient had a crepitus sound. Tenderness to palpation of the TMJ was found in 62% of the TMJs.Tenderness to palpation of extra and intra oral muscles were most frequently found in the lateral pterygoid area (80%) and least frequent in the Submandibular region (17%).

Subdiagnoses of TMD showed that all patients had myofascial pain only or in combination with other

diagnoses. All patients were suffering from at least one subdiagnoses of TMD.According to the results of this study; it is likely that all of the subjects met the criteria of subdiagnoses of TMD. These results support the usefulness of the RDC/TMD and in comparing data from different international TMD studies.The group of population in this study is closely similar to the whole country adult population statistics regarding education levels, incomes, and marital status. The clinical findings and subdiagnoses of TMD found in the present study should make researchers, community health planners, and oral health workers considering TMD as a field of preference in dentistry in Saudi Arabian.

49

Introduction

American Dental Association has suggested the term Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD) to describe a cluster of related disorders characterized by pain in the pre-auricular area, the

temporomandibular joint (TMJ) or the muscles of mastication; limitation or deviation in the

mandibular range of motion and noises in the TMJ during mandibular function.1 TMD is a collective term embracing a number of clinical problems that involve the masticatory musculature, the

temporomandibular joint (TMJ) and associated structures, or both.2

Two critical shortcomings which severely limit the generalizability of epidemiological studies are: (1) lack of operational criteria with demonstrated scientific reliability for measuring or assessing clinical signs and symptoms of TMD, and (2) absence of clearly specified criteria for the muscle and/or joint conditions or subtypes of TMD.3, 4 Another issue is that, comparisons of data from many

epidemiological studies are limited by the absence of taxonomic homogeneity between different studies.3, 4 As an initial step to address these shortcomings, Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (RDC/TMD) were presented in 1992.3

Attributes of the RDC/TMD making them especially valuable in clinical research settings are: (1) a carefully documented and standardized set of specifications for conducting a systematic clinical examination for TMD, (2) demonstrated reliability for these operationally defined clinical

measurement methods, (3) use of dual-axis system: Axis I to record clinical physical findings, and Axis II to record behavioral ( e.g. mandibular functional disability ), psychologic ( e.g. depression somatization ) , and psychosocial status ( e.g. chronic pain grade for assessing pain severity and life interference ) through subjective self-report.3, 4, 5

After registration of signs and symptoms, diagnoses can be considered as the most useful clinical summary for classifying subtypes of TMD as well as in clinical decision-making and research. Using reliable diagnoses are critical in establishing a clinical condition and a rational approach to treatment and RDC/TMD are the most widely used TMD diagnostic system for conducting clinical research .6 The RDC/TMD demonstrates sufficiently high reliability for the most common TMD diagnoses, supporting its use in clinical research and decision-making.6

50

To the authors' knowledge, frequency studies of TMD diagnoses according to RDC/TMD have not previously been performed in Saudi Arabia. It was therefore, of interest to examine patients referred to a specialized clinic to analyze to what extent TMD diagnoses could be found.

The aim of this study was to examine the frequencies of clinical findings and subdiagnoses of TMD according to RDC/TMD specifications in a group of adult (20-40 years old) Saudi Arabians reporting pain related TMD.

51

Patients and Methods

Patients

Patients referred to the specialist dental centre in Alnoor Specialist Hospital in Makkah, Saudi Arabia 3 days a week during October and November 2005 were invited to take part in the study.

The inclusion criteria were: • 20-40 years old.

• being able to communicate in an interview.

Three hundred and thirty five consecutive Saudi patients in the age of 20-40 years were asked to take part in the study. Out of the 335 patients, 10 patients declined to participate due to that they either had no time for the interview, or that they were suffering from acute dental pain or that they could not communicate well enough for the interview. Out of the 325 patients, 58 patients reported TMD related pain and were included in this study according to the following criteria:

⊚ reported pain in the face, jaw, temple, in front of the ear or in the ear in the past month. ⊚ reported worst orofacial pain in the last six months that were more than 0 on the

Numeric Rating Scale (NRS).

⊚ reported average usual orofacial pain at times of its experience in the last six months that were more than 0 on NRS.

Official approval to start the study had been taken from the director of the health affairs in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. All patients were given information about the study and asked to participate. They were informed that if they did not participate it would not influence their care at the centre

Twelve patients out of the 58 patients reporting TMD related pain declined to be clinically examined due to no time, no interest, acute pain, and/or communication problems. Thus, forty-six patients remained and were included in the present study (figure 1).