MALMÖ UNIVERSITY 205 06 MALMÖ, SWEDEN WWW.MAH.SE isbn 978-91-7104-633-8

ANDERS EMILSON

DESIGN IN THE

SPACE BETWEEN STORIES

Design for Social Innovation and Sustainability –

from responding to societal challenges to preparing for

societal collapse

DISSERT A TION: NEW MEDIA, PUBLIC SPHERES AND FORMS OF EXPRESSION ANDERS EMIL SON MALMÖ UNIVERSIT Y 20 1 5 DESIGN IN THE SP A CE BETWEEN S T ORIESDESIGN IN THE

Doctoral dissertation in Interaction Design

Dissertation series: New Media, Public Spheres and Forms of Expression Faculty: Culture and Society

Department: School of Arts and Communication Malmö University

Information about time and place of public defence,

and electronic version of dissertation: https://dspace.mah.se/handle/2043/19185 © Copyright Anders Emilson, 2015

Layout: Jonas Odhner

Language editing: Janet Feenstra

Print: Service Point Holmbergs, Malmö 2015 ISBN 978-91-7104-633-8 (print)

ANDERS EMILSON

DESIGN IN THE

SPACE BETWEEN STORIES

Malmö University 2015

Design for Social Innovation and Sustainability –

from responding to societal challenges to preparing for

societal collapse

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ... 13

PART I: INTRODUCTION ... 17

A DARK ENTRY ... 19

Proposal ...32

A design transformationist mindset and approach ...33

A design thing as an in-between space for contemplation ....34

Dark and soft design fiction ...36

Research Project—My Journey to the Crises of Civilization ...38

Research environment ...39

Projects and cases ...40

Interaction Design ...43

Participatory Design ...46

Design space ...49

Politics, Democracy, and Power ...49

Agonism ...50

Governance ...50

Design things ...52

Reframing Design ...54

Object of Study and a Tentative Theory of Change ...56

Transformation and transition ...57

Research Questions ...60

Disposition ...60

PART II: SITUATIONS ... 63

SITUATION ONE: SOCIAL SUSTAINABILITY IN MALMÖ ... 64

SERIES LIST Made by you, based on a list of

titles from the faculty office. Your own dissertation appears on the list – your series number is allocated by the faculty office.

No pagina.

Move to the last page of the manuscript, facing the inside of back cover.

Update coloured characters and make them black.

The Malmö Commission ...65

The Area Programmes ...66

An Incubator Process in Four Phases ...69

Phase One: The Idea of an Incubator Emerges ...70

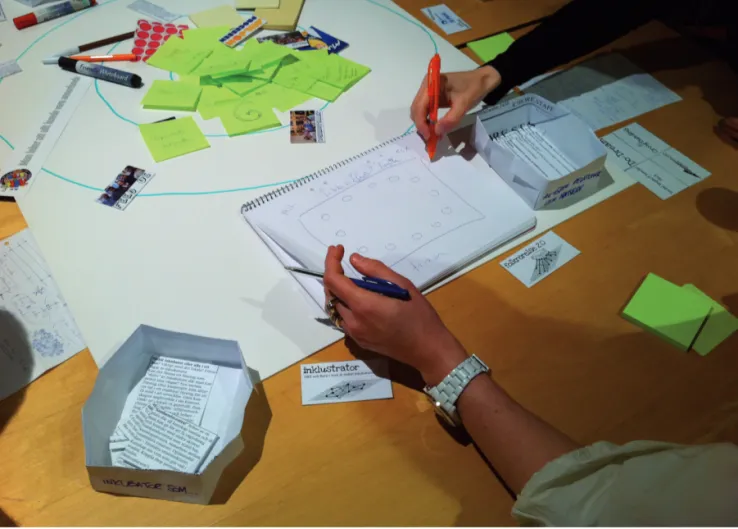

Phase Two: The Workshop Process at Medea ...72

Herrgårds Kvinnoförening ...73

Barn i Stan ...74

Miljonprocessen ...75

Aluma ...76

Gnistan and Kaninhotellet ...76

Feed’us ...77

A Mix of Perspectives, Frames, Competences, Practices, and Sectors ...78

Revisiting the Workshops: Conversations about Possible Social Incubators ...80

Workshop One: March 4, 2011 ...80

Workshop Two: March 18, 2011 ...87

Workshop Three: April 1, 2011 ...96

Four scenarios ...97

Outcomes of the workshop ...103

Conclusions from the Workshops ...105

Phase Three: The Trade and Industry Process ...108

Phase 4: Shrinking Democracy and an Incubator for “New Jobs and Innovation”...111

The Process of the Innovation Forum ...118

The pre-study ...119

Outcomes ...120

Guiding principles of the Innovation forums ...121

The organization of Innovation forums ...122

SITUATION TWO: THE CRISIS OF CIVILIZATION ...125

PART III: THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ...135 SUSTAINABILITY, COLLAPSE, AND RESILIENCE ...136 Sustainability or Resilience? ...137 COLLAPSE ...141

Resilience ...146

Community Resilience ...152

Collaborative and Communicative Resilience ...154

Critical Perspectives on Resilience ...157

Transition ...159

A Safe Operating Space— Planetary Boundaries and Social Targets ...164

Shocks and Slides—Survival and Transformation ...166

SOCIAL INNOVATION ...168

The Social ...168

Social Innovation, Social and Societal Entrepreneurship— New Arenas for Design ...172

Why Social Innovation? Background and Context ...174

A New Innovation Paradigm ...178

Definitions ...179

Difference Between Social Entrepreneurship and Social Innovation ...183

The Hegemonic Battle Over a Name ...184

Networks in Social Innovation ...186

Complexity and Systemic Social Innovation ...189

Merging Social Innovation with Resilience ...192

DESIGN ...197

Design as We Know It—Some Basics ...199

Design as Conversation with the Situation...203

From technical rationality to societal issues in the “swamp” .204 Reflection in action ...208

Reflective conversation with the situation ...209

Experiments in reflection in action ...211

Schön as forerunner of design things and Adversarial Design ...212

Contemporary Design Approaches Addressing Societal Challenges ...215

Transformation Design and Service Design in the United Kingdom ...215

Design for Social Innovation and Sustainability (Italy) ...217

Design and Politics ...220

Absence of the political in Design for Social Innovation ...223

FRAMES AND VALUES ...231

Frames ...234

The Common Cause Reports ...237

Putting frames into practice ...244

Frames and Social Movements ...246

Frames in Sustainability and Resilience Theory ...249

Frames in Design Theory ...253

Rhetorical frames, action frames, and metacultural frames ...258

Policy controversies and frames ...260

Design rationality and frames ...262

Frames Applied in this Thesis ...269

REFRAMING THE FUTURE WITH STORIES ...272

Scenarios and Stories in Science ...274

“The Great Transition” ...279

The Dark Mountain Project ...292

Design Fiction and Speculative Design ...298

Design fiction ...300

Speculative Design ...303

Life practices in fictitious worlds ...308

Dark and Soft Design Fiction ...312

Visions and Utopias ...316

PART IV: CLOSURE AND NEW BEGINNINGS ...323

WHAT’S GOING ON? IN THE CONVERSATION WITH THE SITUATION ...324

Who? Framing Relation, Participation, and Ownership ...327

What? Framing Issues and Activity ...331

Initial framing of issues and activities ...331

Framing of issues and activity during the workshops ...333

Framing of issues and activity during the trade and industry phase ...334

How? Functions and Organization of the Incubator ...335

Agonistic Design Thing, Governance Network and Powerful Strangers ...339

Discussion ...342

PROPOSAL—A DESIGN THING IN THE PROSPECT OF COLLAPSE ...345

Take a Breather ...345

Functions of the Design Thing ...347

The Transformationist and the Idiot ...348

A Design Transformationist Approach ...350

The Design Thing as an In-Between Space for Contemplation ..352

Big picture and long view ...352

Democracy: participation, agonism, and power relations ...354

The Role of Stories and Frames—Design Fictions ...355

A CONVERSATION WITH THE FUTURE: A SPECULATIVE DESIGN THING ...358

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION ...377

Democracy, Power, and Relations ...380

Practices, Activities, and Work ...384

Arenas and Forums ...385

Implications for Design and Future Research ...386

Conclusion ...392

SAMMANFATTNING ...393

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Planet Earth for hosting us for so long. I understand that you are fed up with us now. Speaking for myself—but in the hope of being joined by others—I will do my best to limit the damage and clean up the mess before I leave.

At the end of this journey I would like to express my utmost and deepest gratitude to my supervisors, Pelle Ehn and Bo Reimer, for their trust, support, and for bearing with me. Most of all, thank you for the off-duty exploration of drinks, food, and music for “survival thought.”

I would also like to thank my closest colleagues, Anna Seravalli and Per-Anders Hillgren. Also, thanks to fellow Living Lab resear-chers, Erling Björgvinsson, Per Linde, and Elisabet M. Nilsson and to everyone at Medea, especially the back officers, Karolina Rosen-qvist and Richard Topgaard.

Thanks to all my co-explorers out there: everyone at Herrgårds Kvinnoförening, everyone involved in Områdesprogrammen, Inno-vationsforum, and the incubator workshops. I would like to extend an additional thank you to Jila Moradi, Bjarne Stenquist, Annette Larsson, and Tommy Wegbratt.

Thanks to everyone I worked with at K3 over the years—you are all great! An additional thank you goes to Mette Agger Eriksen, Erik Källoff, Kristina Regnell, Maria Hellström Reimer, and Ewa Sjöberg (you all have worked close to me and supported me at cer-tain stages), Staffan Schmidt (for keeping me alive by putting me on a bike), Jonas Löwgren (for caring, reading, and encouraging com-ments), Micke Krona and Jakob Dittmar (for chatting, wrangling, and words of wisdom).

Thanks to my fellow PhD students at K3: Zeenath Hassan, Mads Høbye, Mahmoud Keshavarz, Kristina Lindström, Luca Simeone, Eric Snodgrass, and Åsa Ståhl.

Thanks to everyone at Designfakulteten (The Design Faculty), especially Peter Ullmark, Bo Westerlund, Stefan Holmlid, Sara Il-stedt, Mats Rosengren, and Karin Blombergsson. Thanks to all fel-low PhD students out there. Thanks to Laura Watts, whose course Writing Imaginaries, Making Futures, led to a breakthrough in my thesis work.

Thanks to Thomas Binder for his comments at my 50% seminar and to Kenneth Hermele for a really constructive conversation at my 90% seminar and for showing me the direction to Ernst Wigforss and the concept of provisional utopias.

Thanks to Janet Feenstra for language editing and to Jonas Odhner for layout.

This journey began with my brother, Johan, whose interest in design and architecture I embraced. Thanks Johan, for your inspiration, and for the visits to Gropiusstadt and the Bauhaus archive in Berlin. My next stop was a trainee post at the Swedish design magazine Form, where I learned to write as a journalist (sort of). Many thanks to Karin Ahlberg, Ulf Beckman, Lotta Jonson, Kerstin Wickman, and Susanne Helgeson. Ulf Beckman kindly recommended me to Carl Henrik Svenstedt, who then employed me as his assistant in the Shift Project in the early years of K3. Thanks Carl Henrik—that was a great time! Thanks to Håkan Edeholt, who brought me in to teach at his course in Design Theory. Thanks also to Ingrid Elam, who let me develop the course, Design for Sustainability, and to Ylva Gis-lén, Torvald Jacobsson, and Maria Hellström Reimer for their input when developing that course. Thanks to Oksana Mont and Carina Borgström Hansson for our collaborations over the years. Thanks to José Barbosa for joining me in exploring the (for me, new) concept of social innovation. Thanks to Marcus Jahnke and Otto von Busch for discussions and inspiration in my early explorations of sustai-nability and social innovation. Thanks to my colleagues at Urban Studies, with whom I have a shared interest in sustainability and so-cial innovation, among others: Fredrik Björk, Ebba Lisberg-Jensen, Magnus Johansson, and Peter Parker.

Thanks to my parents, Gunnar and Kristina, for always sup-porting me. Thanks to all Emilsons out there, and thanks to Sofia for sharing Igor with me. Igor, you mean the most to me—thank you!

A DARK ENTRY

Welcome to our hell, it is the best and only reality we can ima-gine, we’re sure you will like it too. (Andrew Simms 2013, 383) Every culture has a Story of the People to give meaning to the world. Part conscious and part unconscious, it consists of a matrix of agreements, narratives, and symbols that tell us why we are here, where we are headed, what is important, and even what is real. I think we are entering a new phase in the disso-lution of our Story of the People, and therefore, with some lag time, of the edifice of civilization built on top of it.

/…/

We do not have a new story yet. Each of us is aware of some of its threads, for example in most of the things we call alternati-ve, holistic, or ecological today. Here and there we see patterns, designs, emerging parts of the fabric. But the new mythos has not yet emerged. We will abide for a time in the space between

stories. (Charles Eisenstein 2013, my italics)

But there is a space between hope and despair, which it is necessary to inhabit. False expectations and foolish dreams lead to the very despair they claim to want to banish. And that despair is a rational reaction to much of what is going on in the world; sometimes it is necessary to embrace it. Between

the forced hope and gritted teeth of the activist worldview and the dark hopelessness of the apocalyptic narrative lies a

space that is worth sitting in for a while. (Paul Kingsnorth 2014,

my italics)

We are living in transformative times—in the space between stories. Weak signals are becoming stronger and more frequent. We seem to be approaching the end of the era we call industrial civili-zation. Soon, we may enter into something quite different. If this is the case, we will leave a stable period of progress and growth and enter into a long period of decline where many of our systems and support structures will grind to pieces and eventually collapse. From the perspective of how we are accustomed to living our lives and the narratives we live by, the future looks dark. How will this affect an optimistic, creative, and future-making discipline like design—a discipline that emerged out of the industrial revolution? What can design offer in the transition from industrial civilization to a new society where we can both survive and thrive? What is the role of design if not to design for the market economy? What possible futures will designers then propose? I cannot give any exhaustive answers to these questions, but we must start asking them. The aim of this thesis is to contribute to the beginning of an inquiry into what the role of design could be in the prospect of a collapsing civilization. My initial research topic was Design for Social Innovation, and in a way, it still is. Social innovation is an approach to tackle societal challenges such as climate change, chronic disease, social exclusion, and aging populations when established approaches used by the market and governments have been insufficient. Social innovation is seen by many as a way to attain sustainability, and this has led to the emerging design research field, Design for Social Innovation and Sustainability. In most definitions of sustainability, this field is said to consist of at least three aspects: the social, the ecologic, and the economic. These are interconnected and, as a consequence, to be able to address sustainability, one needs to take a holistic approach. Thus, for me to isolate and focus on the social aspect simply because my topic is social innovation would be misleading. Social innovation does not only concern so-called social problems, as in the relation- ships between humans, but also it concerns societal problems and

relations between the social world, the natural world, and the arti-ficial world. In most cases, these societal problems can be tracked down to one source: resources. Our resources are both overused and unequally distributed. This is a simplification of something very complex, and I think that any attempt to solve societal challenges without departing into this insight will most likely be unsustainable in the long term. We think we solve problems, but what we actually do is just push them ahead of us. In this way, nothing changes. We just continue on the same trajectory and sustain the unsustainable.

But what if we are unable to reach sustainability? Then we will enter an era of collapse, the opposite of sustainability. The prospect of collapse prompted me to look beyond sustainability and address the maybe “more important” (Stengers 2005, Michael 2012) matter of concern—the collapse of industrial civilization. How will addres-sing this most urgent and unpleasant issue affect how we perceive the world and address our challenges? How do we imagine the almost unimaginable—life in a collapsing world? Actually, we can simply look at certain other parts of the world, whether they contain eco-systems, economies, cities, or countries, which have already more or less collapsed (for example, bankrupt Detroit, Spanish ghost towns, or Sao Paulo without water) and imagine ourselves, the inhabitants of industrialized civilization, living there. A more pleasant task is to imagine the contours of a world where all humans and nonhumans both survive and thrive. The prospect of collapse has spurred some design researchers (Tomlinson et al. 2012a, 2012b) into exploring the role of design in this scenario. I subscribe to this expedition into the space between sustainability and collapse—“Fail we may, sail we must.”

With the term ‘design,’ I mean an explorative conversation with

the situation (Schön 1995), where a designer or a collective of design-

ers explore a situation by changing it. The designer makes a move, for example, by changing the placement of a window on an archi-tectural plan and then listens to the situation’s “back talk.” Then, the designer reflects and makes a new move. This reflective conver-sation continues until the designer likes the result. Design is a change

practice, and to design is to change undesirable situations into

desired ones (Simon 1994). To design is also to propose possible and alternative futures (e.g. Krippendorff 2006, Koskinen et al. 2011),

but what possible futures do designers explore? Today, a majority of designers, sometimes quite uncritically, explore the possibilities of new technology; for example, the research field of the Internet of

Things (IoT) which builds on the estimation that, by 2020, there will

be fifty billion devices connected to the Internet (Cisco 2015). The driving force behind this development is the foundation of industrial civilization: the belief in progress and growth.

The growth and convergence of processes, data, and things on the Internet will make networked connections more relevant and valuable than ever before. This growth creates unprecedented opportunities for industries, businesses, and people. (Cisco 2015, my italics)

I think this kind of uncritical attitude is dangerous and may lead us to a world where we are stuck with infrastructures that are highly complex, vulnerable, and could ultimately contribute to societal breakdown. To avoid this, designers (and the rest of us) have to learn to navigate between the development paths of the future: those that will likely lead to sustainability and those that will likely lead to collapse. In this thesis, I explore two such paths: Great Transition and Conventional Development (Raskin et al. 2002) and what is needed to change from one path to another.

Great Transition and Conventional Development are scenario

storylines developed by the Global Scenario Group at the Stockholm Environment Institute. According to Gerst, Raskin, and Rockström (2014), the Great Transition scenario may lead to a world within

planetary boundaries (e.g., climate change, biodiversity) and social targets (e.g., hunger, inequity), that is, a world that is environ-

mentally and socially sustainable. Alternatively, Conventional De-velopment (a term I will use in parallel with business as usual and

current way of life) may lead to a world where we transgress many

planetary boundaries and are unable to meet social targets which, in turn, could lead to environmental and societal collapse (see figure 1). I will consider the space between these stories—the space between sustainability and collapse—as a design space (Westerlund 2009) consisting of many possible futures to explore. How do design- ers and other changemakers position themselves in this space? Are

our design explorations and proposed possible futures in line with Conventional Development or Great Transition? If we have the will, how do we change paths from the one leading to collapse to the one leading to sustainability?

The Conventional Development scenario builds upon the continuation of current industrialized civilization and its belief in technological progress, the market, and economic growth. This is a well-known narrative often described in mainstream media, discussed in political debates, and advocated by politici-ans and business interests. The Great Trpolitici-ansition story is less well known but advocated by researchers and concerned citizens

Figure 1. “Conventional Development and Great Transition scena-rio results” (Gerst, Raskin and Rockström 2014, 127). The inner-most circle defines the pre-industrial values of planetary boundaries and “ideal” social targets. The following bold circle defines “a safe operating space” (ibid., 124) within planetary boundaries and social targets. Green wedges show that we are within a safe operating spa-ce, whereas red wedges show that we have transgressed planetary boundaries and are unable to reach social targets.

who have begun developing alternative local communities accor-dingly. The message from these scenarios is simple and clear: shrink or suffer.

In the exploration of the space between sustainability and collapse, I consider and discuss various approaches to these challenges. The first is more conservative and aims to sustain the current world and its societal organization by avoiding a collapse. This approach builds on the mitigation of causes and belongs to the sustainability camp. In the other approach, one has realized that we are unable to reach sustainability within the norms and organization of current society, and therefore, we need to transform into a new society. This approach builds on adaptive and transformational capacities and belongs to the resilience camp.

In this thesis, the social is not limited to relations between humans but will include the relationships between humans and nonhumans (other species and artefacts) in actor-networks (Latour 2005a). In this thesis, a seabird with its stomach full of plastic will represent other species. Certainly, we have a long way to go before reaching the Cradle to Cradle (Braungart and McDonough 2002) principle of keeping technological and biological metabolisms separated. A scythe will represent an alternative view on artefacts. One can address these relationships from many perspectives, but I think questions of justice and equality are crucial. This relates to the local context of this thesis and the mission of the Commission for a Social- ly Sustainable Malmö (the Malmö Commission) to address health inequities and gaps in life expectancy among the diffe-rent groups of society. The issue of inequity is also a departure point in one of the sources of the concept design for social

inn-ovation and sustainability. Manzini and Jégou (2003) address

this issue when discussing the broken promise of what they call ‘product-based wellbeing.’

In fact if all the inhabitants of the planet really sought this type of well-being (as is their divine right, since that is what others do and what is daily promised to them), there would be a huge catastrophe. An ecological catastrophe if they were to succeed, since the planet would be unable to support 6–8 billion people approaching western levels of consumption. Or a social

cata-same standards, which only a few could reach. (Manzini and Jégou 2003, 40)

More recently, Hornborg (2014, 92) discussed our belief in techno-logical progress and how it is based on the unjust use of resources and labor; therefore, technology “is ultimately a question for the social sciences, rather than engineering. For whom will it be possible to invest in solar energy or household robots?” Hornborg (2012) claims that environmental issues are issues regarding the fair distri-bution of resources. Our progress and welfare in the North has been possible because it was based on unequal exchange with the South. The justice aspect is also stressed in a discussion paper from Oxfam in which Kate Raworth (2012) brings forward the idea of a safe and just space for humanity where we can live a life based on soci-al foundations and within planetary boundaries. It is not only our high-tech future that is unevenly distributed, but also our prospect for survival. How we choose to deal with this injustice will influence the design of any possible futures.

During the past ten years we have seen a development within design where designers not only take on challenges regarding new products and services for the market, but also, to an ever-increas-ing degree, involve themselves in addressever-increas-ing what we can call ‘pub-lic and societal challenges’ (Manzini and Staszowski 2013, West-ley, Goeby and Robinson 2012, Bason 2010). These challenges call for new forms of problem solutions, which “may require radical, systemic shifts in deeply held values and beliefs, patterns of social behavior, and multi-level governance and management regimes” (Westley, Goeby and Robinson 2012, 3). In the search for new forms of problem solving, an emerging discussion and the exchange of ideas, experiences, and approaches between the disciplines of design, social innovation, and resilience are taking place. An example of these exchanges and the merging of these fields were to be found at Nesta’s Social Frontiers conference held in November, 2013. It is against this background that one should understand the explora-tions of this thesis.

I will discuss three sets of concepts: (a) design things and how (b)

by a constellation of concerned citizens to explore possible futures. A design thing (Ehn 2008) is an assembly of human and nonhu-man actors gathered to address an issue or an object of design, and can be seen to have a family resemblance with many new ideas for democratic platforms suggested by different actors, for example, in

hybrid forums (Callon, Lascoumes, and Barthe 2011) or knowledge alliances (Stigendal and Östergren 2013). As well as needing

alterna-tive futures, we need new platforms, forums, or arenas where these futures can be explored and debated because as Callon, Lascoumes, and Barthe (2011, 68) state, “the exploration of possible worlds, and the choice between them” are political choices which need to be debated. Consequently, designers will not make the future alone; other future makers will be needed. Therefore, I propose that partici- patory designers ally with social innovators, resilience thinkers, alternative economists, activists, change makers, and concerned citizens to explore how our values and frames (worldviews) in-fluence both how we define a problem and which trajectories of inquiry we choose to explore in search of solutions. Our worldviews are built on stories, and therefore, I will also explore how different forms of design fiction make us aware of both existing and new per-spectives as well as future paths to investigate.

“Frames are mental structures that shape the way we see the world” (Lakoff 2004, XV). To reframe a situation—to see the world from a new perspective in order to create a new worldview—will be a crucial function in the conversation with the situation. When we set a problem or frame a situation, we use the stories that people tell about the situation and the metaphors underlying these stories. Reframing our situation involves finding new frames, stories, and metaphors through which we can navigate our way into a future of scarcity rather than abundance. For example, what will it mean if “metacultural frames” (Schön and Rein 1994) like progress, expansion, and growth are replaced with decline and contraction? We know the first group is associated with positive things and the se-cond group is more associated with something … dark. Or especially at first sight, but much research shows that words like simple, slow, and less are associated with well-being and sustainability and, as a consequence, could be considered guiding principles for the future. For example, according to conventional policy, we have to work

more and create more jobs to maintain our welfare and to create

social inclusion. But according to new research (Coote 2015, Coote, Franklin and Simms 2011, Holmberg et al. 2011, Sanne 2012), we need to work less and share jobs for both living well and living sustainably. Also, according to our old worldview, words such as equal and common are less glamorous and positive than growth and progress, but they seem to hold values which are deeply rooted in people (see intrinsic and self-transcendence goals, and “bigger than self-problems,” Crompton 2010) and form the basis of many alternative theories of how to organize society. We can already see examples of a value and practice shift in the many models emerging today which are based on sharing rather than owning. The idea of

commons is recurrent in discussions of current alternative economic

models, as explored in the work of my colleague, Anna Seravalli (2014).

My working hypothesis is that working with values and frames more deliberately in a design thing could be helpful in generating possible futures in which humans could live well in relation to each other, to the natural world, and to the artificial world. How to do this is what I want to explore, and as Charles Eisenstein requests in the quotation at the beginning of this chapter, one clue is the need for new stories. “It is through stories that we weave reality,” state Dougald Hine and Paul Kingsnorth (2009) who initiated The Dark Mountain Project to challenge the stories that underpin our civili-zation and to search for new ones. These stories and words could help us create new frames for phenomena such as post-carbon life, transition, and life within planetary boundaries and social targets. These frames have to be activated by the words, stories, metaphors, associations, images, and experiences that help us reframe how we understand and “know” the world and ourselves. A growing body of research (e.g., Raskin et al. 2002 and Crompton 2010) points to the importance of working with values and culture if society is going to be able to transform itself into sustainability and resilience. Also, values play a crucial role in whether or not a society will collapse. Diamond (2011, 433) states that, historically, civilizations on the brink of collapse have chosen the wrong path into the future because it is “painfully difficult to decide whether to abandon some of one’s core values when they seem to becoming incompatible with

survival.” Thus, we cannot only rely on changes in technology, the economy, or governance; we also require changes in people’s values and beliefs. Therefore, to a great extent, the transition into a new civilization becomes a cultural project. What can design offer in sup-port of this cultural and values-driven movement? I think design approaches like scenarios, prototypes, and design fictions have a role in filling these frames with, not just words, but with imagina-tions and experiences of life in these new worlds. In this thesis, the concept of frames and frame reflection will also serve as a kind of “boundary concept” that other disciplines share. As a consequence, this thesis will be built on a cross reading of theory and practice from mainly (participatory) design, social innovation, and resilience. As we will see, threads and overlapping take place between these fields and a researcher like Frances Westley, for example, addresses the links between resilience, social innovation, and design. However, a warning must be issued regarding these fields; they all give the im-pression they are the solution to everything. In light of this, one must be aware of their weaknesses as well as developing their strengths and potential.

Unger (2013) claims that we live under the “dictatorship of no alternative.” Others suggest that the lack of any real alternatives to neoliberalism and the market economy, which are both in line with Conventional Development, has us living in a post-political world where democratic agonistic struggle “over the content and direction of socioecological life” (Swyngedouw 2014, 31) has given way for consensus and governance (I further develop this discussion). At the same time, Bollier and Conaty (2015) state that a wide range of al-ternative movements exist which abide by concepts like commons, co-operatives, degrowth, social solidarity economy, peer-production, sharing and collaborative economy and transition towns. I consider these alternatives to be in line with the Great Transition scenario; however, these alternatives have not yet converged to a “movement of movements” (ibid.) strong enough to challenge neoliberalism and Conventional Development. Nevertheless, in these alternatives, or “real utopias” (Wright 2010), there exists a “hope beyond hope” (Hine and Kingsnorth 2009) which contains pieces of possible futu-res for us to compose a world wherein we survive and thrive.

Therefore, the most important actors in the collective “conversation with the situation” (Schön 1995) are those who are already imagi-ning alternative ways of living or who are already living the alter-natives. In this thesis, I turn to critical and alternative actors such as citizens living in transition towns or other communities trying to become resilient. I will also look into the use of stories coming from cultural actors like The Dark Mountain Project. What they have in common is that they look at the world from new perspecti-ves—they reframe reality. Their experiences and stories are valuable contributions when we need to consider possible futures which are quite different from conventional development. These actors may be related to bottom-up social innovations created by what de-sign researchers call “creative communities” (Meroni 2007, Jégou and Manizini 2008). More recently, Environmental Scientist Jeppe Dyrendom Graugaard (2014) has studied The Dark Mountain Pro-ject and looked into the role of narratives in “grassroots innova-tions” leading to “sustainability transitions.” He argues that:

Grassroots innovations are prospective sites of transformative sustainability visions and (counter-)narratives, and when alter-native knowledge become embodied in new practices grassroots innovations become sources of socio-cultural transformation, creating new possibilities for living differently. In this way, grass-roots innovations are potential sites of transition not just in ma-terial practices but in worldviews: sources of transformation in the experience and interpretation of reality which give rise to new ways of being and thinking. (Graugaard 2014, 35-36)

We need new perspectives, new frames. We need the “other,” as in “other forms of work” (Stigendal 2012, 34), an “other” economy (e.g., commons, sharing, and circular economy), or “another world is possible.” Not more of the same. To make the transition from in-dustrial civilization to a new civilization where we live within planet- ary boundaries and social targets, we must also make a cultural transition. We need to see the world in a new way, and we have to construct a new story to live by. Here, dry facts and scenarios from scientists are not enough. Who can imagine what it is like to live within planetary and social boundaries from a pie chart? This is not

only a scientific and technical issue, but also a cultural issue where writers, artists, and designers need to contribute with new stories and imagination. I believe that design fiction could be generative in the collective conversation with the situation. What I will call dark

and soft design fiction (to distinguish it from conventional,

tech-no-centric design fiction) may be a way to explore the space between sustainability and collapse. I imagine dark and soft design fiction to be compositions of stories coming from science, culture, and areas of activism (i.e., people living in transition towns and grassroots innovators).

We have learned from collapse theory that too much complexity will lead to collapse (Tainter 2006). A design fiction based on these insights could describe a way of living that is much more simple and slow rather than complex and accelerating, which is the case with most high-technology visions explored in contemporary design fiction. To bring a vision of a simpler life, with all its qualities, dilemmas, and challenges could be generative in reframing our situa-tion and allow for the staking out of new trajectories of inquiry and action. Contemplating our future through a collapse scenario may also influence what aspects of technology we choose to live with. In a world where most global flows of resources and energy have broken down, will it be through a screen-based digital device and digital literacy that we get food on the table? Or is it with a scythe and hands-on knowledge about growing crops?

The empirical material in this thesis concerns the experiences of set-ting up a design thing in Malmö and being involved in a pre-stu-dy which explored the possibilities of introducing design practice into public services in the form of so-called Innovation forums. The design thing was aimed at exploring what an incubator for social innovation could be. In both cases, we failed in the sense that the projects were either hijacked or shut down before the proposed ideas could be prototyped and implemented. This could be explained as both a lack of framing and understanding of the situation, a failed design conversation, and the dislike of powerful and conservative actors with agendas in line with Conventional Development. I draw upon these experiences when developing my proposal for how de-sign could work in these dark times. One lesson learned from these

failed cases is the importance of a continuous process of inquiry by a constellation of heterogeneous actors, whether we call it a design thing or a knowledge alliance, to reach the long-term goal of reorga-nizing society in contrast to simply implementing a concrete project to fulfill a short-term goal. A project was designed and implemen-ted according to Conventional Development, but a design thing that could address societal challenges over a longer period of time was not. It was stopped at the embryonic stage. This is the difference between a more conservative way of organizing change by addres-sing addres-single issues and short-term effects and a more transformative way which addresses core challenges and systemic change over a longer periods of time and on many levels.

In analyzing what happened in the incubator process, I view it as a “design conversation” in line with Schön’s meaning. This conversation was influenced by many aspects, which I will try to capture through the concepts of governance, agonism, frame, and

generative metaphor. I follow three trajectories: who, what, and how. The first is about democracy and who is able to participate

in the conversation and make his or her opinion heard; it is about power, positions, and relations. In this case, I will first use the frame concept to see how the participants framed participation. Later, I will discuss this framing in relation to the concepts of governance,

agonism, and the term ‘powerful stranger.’ The second trajectory

regards what issues we want to address, what kind of problems do we deal with, and what we consider designing and how do we decide that? In this case, I use the concept of frames and frame

reflection. The third trajectory is closely related to the others

and concerns how the incubator should be organized and func- tion. Here, I will look at how the participants used a generative me-taphor to reframe the incubator.

I consider the incubator process to be a failure; however, accor-ding to many politicians, civil servants, and business leaders in the city, the outcome was a success (never mind the process). The out-come resulted in an organization that has created more jobs in the city, but there is a dark side to this success. This is the result of

Conventional Development, a collaboration between market forces

and policy, while the actors associated with Great Transition, civil society and ordinary citizens were excluded from the decision phase

of the process. This shows how hard the grip of Conventional De-velopment is on our way of addressing societal challenges. This firm grip of Conventional Development makes the prospect of collapse most plausible. From this perspective, this so-called success evokes fear rather than hope.

But while I consider our experience of setting up a design thing a failure, that does not mean I do not see any potential in the con-cept; quite the contrary. We have just started to explore the concept. At the end of this thesis, I continue this exploration by staging a

fictive design thing that addresses the prospect of collapse. In the

proposal, I will depart from our experiences of the incubator pro-cess, but also complement those experiences with similar ones from resilience research (e.g., Bullock, Armitage and Mitchell 2012) and design (Schön and Rein 1994) where a constellation of actors per-form collective inquiries of situations. These cases also demonstrate that certain heterogeneous and agonistic constellations are able to reach positive outcomes.

Proposal

The end of the world as we know it is not the end of the world full stop. Together, we will find the hope beyond hope, the paths which lead to the unknown world ahead of us. (Hine and Kings-north 2009)

My contribution to design research is to point out the space between Conventional Development and Great Transition as a design space necessary to explore. My proposal for the exploration of this design space will consist of three parts:

• A design transformationist mindset and approach

• A design thing addressing the prospect of societal collapse which will function as a space for contemplating the space between stories

• The use of dark and soft design fiction to support a reframing of the world and to map out new trajectories of inquiry

A design transformationist mindset and approach

If Design for Social Innovation and Sustainability is still an emer-ging, although rapidly expanding, field—to address the prospect of collapse is to operate in the utmost margins of design research and society at large. To take on this challenge means meeting resistance and scepticism. But as Blevis and Blevis (2010, 28) put it, “at least some if not many of us” need to consider this aspect of sustainabili-ty. Therefore, I think that designers willing to take on this challenge will need both a certain mindset and approach. I will call this a

design transformationist mindset and approach.

I have borrowed the term transformationist from Raskin et al. (2002) who describe three archetypal mindsets: evolutionists, catastrophists, and transformationists. Transformationists share the fears of catastrophists in that deepening social, economic, and en-vironmental tensions will not be resolved by Conventional Develop-ment advocated by evolutionists which, in turn, will have dire conse-quences for the future of the world. Transformationsists face the dark sides of our future. They do not look away, nor do they turn to the rosy dreams and false hopes of technological development and economic growth. Neither do they give up or isolate themselves in protected enclaves for the strong and privileged like the catastrop-hists. Transformationists believe that global transition can be seized as an opportunity to forge a better civilization. In translating this mindset into a design approach, some of its characteristics could be described as follows:

• To acknowledge that beyond the societal challenges that we address today, other, much more complex and unpleasant challenges must also be approached.

• To acknowledge that we may be unable to reach sustain- ability or resilience by working according to Conventional Development.

• Working with the parallel strategy of both trying to avoid a collapse through mitigation and adaptation while, at the same time, exploring the alternatives needed in the Great Transition into a new society, into a world where we can both survive and thrive together with both artificial and natural nonhumans.

• Intentionally seek to overcome the separation between humans, artefacts, and nature.

• Set up design things dedicated to exploring alternative life- worlds for both humans and nonhumans.

• Invite actors representing both our current world, but also possible future worlds of collapse and transition.

A design thing as an in-between space for contemplation

A design thing addressing the prospect of collapse will have the following characteristics and functions:

• An in-between space • A space for gathering

• A space for contemplation and exploration • A space for positioning and navigation • A space for reframing

• A space for agonism

One of the proposals from the participants in the design thing ex-ploring a social incubator, the empirical case in this thesis, was the notion of a “free zone” where one could liberate oneself from the conventions, habits, and constraints of one’s work or organization. In the “free zone,” one may also change roles with other actors with whom one collaborates. I would suggest that a design thing addres-sing societal collapse could function as such a free zone, but in an ex-tended way. This design thing could function as a space in-between sustainability and collapse where one “stays for a while” (Kings-north 2014) and contemplates life according to different prospects. This could be a space for “uncivilising” (Hine and Kingsnorth 2009) ourselves, reframing reality, creating new stories and imaginations, and mapping out new trajectories of inquiry. This could be a space for the contemplation and preparation of a “reservoir of alternati-ves” that are considered “threatening within the normal social space because they challenge habit and the flow of resources” (Westley, Goebey and Robinson 2012, 14). This space could be created by fictions, enactments, and various other design techniques like proto-types and mock-ups.

de-sign thing is to imagine it situated in the no-man’s land that is the space between the two contrasting worlds of Great Transition and Conventional Development. The role of the thing will be to not only invite us, the inhabitants, of the current world, but also the inhabi-tants of these two possible future worlds to share their stories with us. What is it like to live in a collapsed world? What do you eat? What is it like to live in the world after the Great Transition? What do you teach the kids at school? Could this be a way to make future generations, of whom we so often speak about when discussing sustain- ability, present here and now? These stories from the future will be told through various kinds of design fiction. What happens to the conversation about an object of design (e.g., an incubator) or a mat-ter of concern (e.g., work) when we place it in the different worlds or worldviews? In this way, the design thing offers a space where a constellation of actors can have a conversation with the situation about the object of design through the frames of a possible world or a speculative society. In the thing, the frames of a possible world could temporarily replace the frames of the current world. In this way, the thing could serve as a utopian space; a space “for specu-lation and critique in the interest of change” (Bradley and Hedrén 2014, 7).

Another important role of the thing is to help the participants position themselves. Where in the space between stories are we now? Where do we want to go? The core question in the thing will there- fore be: when we talk about the world or society, which world or society do we talk about? Do we talk about the current conventional world, a collapsed world, or a Great Transition world or even some other possible world? Are our projects, visions, and aspirations on the path of Conventional Development or Great Transition? What are the signs of collapse or resilience in our current world? Which paths or world do we want to work towards in the design thing?

There is a temporal aspect to our challenges that also makes the notion of contemplation attractive. There is urgency in addressing the prospect of collapse; however, to turn to the quick fixes and low-hanging fruits of Conventional Development would probably be a mistake. It is not only a matter of contemplating in which world we want to live, but also we need to consider what it will take to get us there. Is it just to book a ticket on the Internet and jump on

a flight for a couple of hours and arrive fresh in a new world? Or is this a long and adventurous journey across continents—by foot? If there is no fuel in the airplanes, we better start walking.

As this kind of design thing deliberately challenges business as usual and the hegemony of the already powerful, there will be frame conflicts. I will propose some strategies to deal with these frame and power dilemmas, such as the use of shadow networks (Bullock, Armitage and Mitchell 2012). These approaches need to be explored in real cases. It is time for design to contribute to the exploration of an other kind of civilization, where people live within planetary boundaries and social targets. For that, we need new stories and imaginations—design fiction.

Dark and soft design fiction

As a complement to the dominating “hard” side of design fiction, with its focus on the artificial side of life and human interaction with new technology, I would like to propose a “soft” design fiction that reconnects with the organic side of life and humans as part of nature. Soft design fiction is also more concerned with speculative societies than with speculating about future technologies that are featured in conventional design fiction. Soft design fiction will be a part of fictional interventions in the design thing that I will call dark

and soft design fiction. ‘Dark,’ because it faces the future without

the rosy dreams and false hope of Conventional Development. The aim with dark and soft design fiction is to support our reframing of the world and the mapping out of new trajectories of inquiry.

When proposing dark and soft design fiction, it may seem that I have come a long way from the projects and design experiments that I actually have been taking part of. But there is a certain moment when the need for bringing in other worlds and perspectives occurs for me. On the way home from a meeting that I and Per-Anders Hillgren had with a couple of immigrant women in Lindängen, one of Malmö’s outer city districts, I remember that I said something like “In the theories and scenarios described by New Economics

Foundation, these women would not be out of a job and feeling that

they are not part of society. Their skills would be a resource.” That is when I saw the need to bring these theories and worldviews to the table and begin to frame design situations from their perspective. To

be able to reach the Great Transition, we will need to make a great

reframing of our world and everyday life within it. To propose the

exploration of potentials in a new kind of design fiction in the great reframing is my contribution.

To summarize, in this thesis I will explore two conversations with situations in two design things—one real and one speculative. The real design thing concerns the experiences of the incubator workshops (the case) and the speculative design thing is a fictive exploration of a design thing addressing societal collapse (the pro-posal). The main task of the speculative design thing is to bring in new perspectives into the conversation with the situation to reframe our situation. This design thing could serve as a place where the space between stories is explored and transgressed. To design in the space between stories is to design in the space between two great narratives, one about a declining civilization and another about a possible and emerging civilization. It is also to design in the space where everyday stories are shared between people. The design of a future where we both survive and thrive must be based on another story. This story will tell a tale about living well within the limits of the planet.

Finally, I am not against technology, innovation, progress, or “growth,” as long as they support life within planetary boundaries and social targets. What I want to make explicit is a deep concern about the state of the world, and the prospect of our survival in it. As repeated many times now, this involves reframing and shifts of words we use, like Latour’s shift from progress to progression:

[As] a subtle but radical transformation in the definition of what it means to progress, that is, to process forward and meet new prospects. Not as a war cry for an avant-garde to move even further and faster ahead, but rather as a warning, a call to atten-tion, so as to stop going further in the same way as before toward the future. The nuance I want to outline is that between

pro-gress and propro-gressive. It is as if we had to move from an idea of

inevitable progress to one of tentative and precautionary

progres-sion. There is still a movement. Something is still going forward.

I would like to make a similar shift in the view of design. My ambi-tion is to go from a view of design as a practice that mainly serves industrial civilization to a view of design that, to a larger extent, takes part in the “collective adventure” (Latour 2010, 472) of sear-ching for a new civilization, or a world worth living in. Yes, there is still the need for movement, but not in the name of progress or business as usual. This searching will not only lead to discoveries of something new, it could also lead to returning. As when Papanek (1995, 234) returned to the Inuit tribes of Alaska, “the best desig-ners in the world” when it comes to survival. Or, like the radical architects, Superstudio, well known for their utopian urban visions, which researched primitive peasant economies in the far reaches of Italy (Lang and Menking 2003). This will not mean a “life without objects” (ibid.) but a reframing of our relation to both the artificial and natural side of life.

Research Project—My Journey to the Crises of Civilization

I will begin with two short conversations in stairs. You know the situation—you meet someone in the beginning, the middle, or the end of a staircase and start talking. The first conversation is at the original K3, the School of Arts and Communication at Malmö University in 2008. I meet Pelle Ehn in the stair of one of the research studios and he asks me if I have any suggestions for themes for new design research. I reply: “Design for social innovation.” At the time, I was working as a teacher and respon-sible for the course Design for sustainability, which was very much inspired by the work of Ezio Manzini and François Jégou. In 2008, they released the research anthology Collaborative Services:Social Innovation and Design for Sustainability (Jégou and

Manzini 2008). This became my entry into design for social inn-ovation. Pelle and I subsequently wrote a research application that was turned down. Later, I got a commission from Design-

fakulteten (The Swedish Faculty for Design Research and Research

Education) to write a research overview (Emilson 2010), and in 2010, I become employed as PhD candidate with the topic Design for Social Innovation.

building that temporarily housed K3 and the research environment, Medea, where, at the time (2011), I was a PhD student and teacher. I meet Bob Jacobson, former entrepreneur-in-residence at Medea, who asked me what I was doing that day and I replied: “I am teaching.” “What do you teach?” Bob asks. “Design for sustai-nability,” I reply. “It’s too late, now it is design for survival,” Bob replied. At that moment, I thought he was exaggerating. However, one year later, I caught up with him and had changed the focus of my thesis from sustainability to collapse.

Research environment

I was employed as a PhD student in Interaction Design within the research environment of the Medea Collaborative Media Initiative at Malmö University. The idea with Medea was to explore the inter-section between the two core disciplines at K3—Interaction Design and Media and Communication Studies. Another fundamental idea with Medea was to do co-production with organisations outside the university. That explains why we, for example, had a business deve-loper as a member of the team. I spent two-thirds of my five years at Medea and the last third at K3—the mother ship—as Medea would temporarily vanish after a change of director and direction.

Within Medea, I was part of one out of three Malmö Living Labs, a research team called Living Lab the Neighbourhood, which had begun to explore social innovation. The group consisted mainly of Senior Researcher Per-Anders Hillgren, who was also the leader of the lab, Professor Pelle Ehn, my PhD colleague Anna Seravalli, and myself. The other two living labs at Medea were Living Lab

the Factory and Living Lab the Scene. Members of the wider living

lab research team were Erling Björgvinsson, Per Linde, and Elisabet M. Nilsson.

The Living Lab concept emerged as response to poor results from closed innovation environments. In contrast, living labs are open, user-driven, and situated in real-world environments. They build on collaborations between researchers, companies, and public and civic sectors. Today, around two hundred innovation milieus are defined as living labs in Europe (Björgvinsson, Ehn, and Hillgren 2012). In the Malmö Living Labs, participants are seen as “active co-creators” (ibid. 131) and not simply as sources of information.

Living Lab the Neighbourhood had been working with partici-patory design mainly in districts in Malmö marked by social exclu-sion. From the beginning, this work departs from the application of new media and IT, but would increasingly move towards public services and the relationships between citizens, associations, small companies, and the municipality. Our work was based on building long-term relationships and using prototyping as a way to evoke and explore possibilities and dilemmas. Our activities were based on three core methodological ideas:

• to set up collaborative design processes where diverse stakehol-ders with complementary skills work side by side, and where mutual respect and learning is supported

• to build long-term relationships and trust with stakeholders • to perform early prototyping where possibilities are explored

in real-life contexts, but where potential dilemmas also are highlighted.

The Living Labs researchers Björgvinsson, Ehn, and Hillgren (2010) had, over the years, developed concepts crucial to this thesis:

infrastructuring and design things. As participatory design is based

upon democratic principles, they had also brought in the concept of agonism (Mouffe 2000a, b) and Hillgren brought in the concept

governance from political theory. For me, it became natural to

attach myself to both the methodological and theoretical framework of the group. In the following text, I will introduce Interaction Design and Participatory Design as well as the concepts of gover-nance and agonism—all elements in the research environment that I depart from in this thesis.

Projects and cases

As a PhD student or researcher, you are expected to have a well- defined project. The problem for me was that I never actually had one. Even when I was part of a research environment or part of a research group, I was never involved in a research project which was required to be finished on a specific date, where we would answer a specific question and use certain kinds of methods. I was more or less left to my own interests and see what opportunities to explore

these would emerge. This experience has been both that of privilege and pain. Also, as I do not have a background as a designer, but more of a mix of cultural studies and journalism; therefore, it was not easy to find what role I should have in the group. Should I start acting as a designer and setting up design experiments? Or should I keep doing what I have always been doing, which is explore new contexts for design? It turned out to be the latter. With that stated, I have not only been sitting on the sidelines reading books and reports, but also I have been actively involved in project work both in the studio and in the field. In the beginning, I joined Per-Anders Hillgren in his work with Herrgårds Kvinnoförening (see Hillgren, Seravalli and Emilson 2011, Emilson, Hillgren and Seravalli 2014). This work, in which Anna Seravalli was also involved, continued during the first three years and involved many meetings and also various design experiments and prototypes. In this initial phase of my research, my interest was in “designing networks” (Jégou and Manzini 2008) or how design could support constellations of actors with complementary skills, knowledge, and perspectives in explo-ring various societal challenges. These actors where both bottom-up and top-down, and the title of the first presentation of my research was “Designing with the Bees and the Trees,” influenced by Mulgan (2007). These interests are still with me in the conclusion, but in another terminology. During my research, I found the concept of

frames to be in line with what I initially, and more casually,

discus-sed as perspectives and worldviews. In the same way, what I initially discussed as a constellation of actors, I will discuss as design things and Living Labs.

In the spring of 2011, we, (Ehn, Emilson, Hillgren and Seravalli) were commissioned by the City of Malmö to run a series of three workshops to explore what an incubator for social innovation could be (Ehn et al. 2011, Emilson and Hillgren 2014). This will be the main case in this thesis. In connection with this, I became part of a pre-study run by the City of Malmö which explored the idea of Innovation forums, which are small, design-based innovation teams which could support civil servants in meeting citizens and deve-loping their ideas about social change (see Larsson 2012). None of these projects can be considered traditional academic research pro-jects with predefined research questions; in these propro-jects, we acted

more as consultants, although we set up the projects according to our methodology and theoretical background. We also used these projects to reflect on the processes and the outcomes. Both these projects had quite unhappy ends; the incubator process was more or less hijacked by a powerful actor, and the Innovation forum project was put in the trash by a senior civil servant, much due to personal dislike. Regarding the incubator process, we were commissioned to conduct some follow-up workshops, but we never managed to do that because it was difficult to mobilize mainly the civil servants, as the original purpose with the incubator was lost. But the needs that both the incubator and the Innovation forums addressed were still there, and discussions regarding both these projects kept recur-ring durecur-ring those years. In 2014, the Swedish National Forum for Social Innovation and Social Entrepreneurship, where Per-Anders Hillgren is a part-time researcher, along with Centrum för publikt entreprenörskap (the Centre for Public Entrepreneurship), arranged a workshop around the issue of “Design som frirum” (Design as Free Zone), which clearly addressed the same issues as the incubator workshops three years earlier.

One can say that both the incubator project and the Innovation forum projects deal with social, or public, innovation as a way to reach (social) sustainability in Malmö. In a parallel process, but without much interchange, the Commission for a Socially Sustai-nable Malmö also researched this issue. Neither of these address the issue of collapse, nor the notion of transition, so how did I end up where I am? Why didn’t I limit myself to simply studying how design could support social and public innovation in the context of Malmö? One reason is that when both projects I was involved in were stopped at a highly explorative phase with no opportunity to create constellations of citizens, companies, and civil servants, and with no opportunity to perform any design experiments, I no longer had the opportunity to explore any of my initial ideas. We tried to set up design processes many times, but did not get any further. Another reason has to do with how I interpret social innovation as system change. When you start to look at our societal systems and the challenges ahead of us, the notion of collapse is unavoidable. I would argue that if you have not considered the possibility that we will fail to reach sustainability, you live in denial.

In this thesis, I often refer to the international Transition Towns movement, where concerned citizens address peak oil and climate change and work according to permaculture principles. This move- ment is also present in Sweden under the label omställning (see om-ställning.net and demokratisk-omstallning.org). Was there not a local initiative that I could have joined? Actually not, although there are spread groups that work in line with this movement in Malmö. The folk high school Glokala Folkhögskolan can be seen as a local center which advocates these ideas, and I had discussions with them about collaboration, but they did not lead to anything. But later, at the end of my project, I was connected to people in Lindängen who run a small forest garden according to permaculture principles. The-se were the right people! However, by then it was too late to The-set up a project and do experiments. Hopefully, I can reconnect with them when I have completed this text and can start putting some of the ideas of this thesis into practice.

My journey to the theme of a civilization in crises and on the brink to collapse can be seen as a circular movement. For me, this started with an interest in Design for Sustainability that led me to Design for Social Innovation as a way to reach sustainability. Our projects have dealt more with social sustainability than environmen-tal sustainability, but I do not think they can ever be fully separated. As we will see, a question of unemployment is not simply a matter of creating more jobs, but ultimately about how we organize society and distribute resources. Today, I am more or less back where I star-ted, but this time with a more worrying aspect of sustainability—the prospect of collapse.

Interaction Design

I am working towards a PhD in Interaction Design and will now po-sition myself in relation to this field. Interaction Design established itself in the mid 1990s as a more design-oriented subdiscipline of Human–Computer Interaction (HCI). Löwgren and Stolterman (2007, 2) define Interaction Design as “the shaping of use-oriented qualities of a digital artifact for one or more clients.” In short, inter- action design is design of digital artefacts. But Löwgren and Stolterman also state that all design is part of “the largest design project of them all – the joint design of the world as a place for human life” (ibid.,

12). Further, they claim that a designer has the “power to change and influence the development of society, which implies significant responsibility” (ibid., 13.). It is this interrelationship between de-sign and society and how dede-signers influence the development of society and the conditions for not only human life, but also non-human life, that I aim to explore in this thesis. Through discussing our prospect of surviving and thriving, I aim to contribute to the discussion about design’s changing role which, in the long run, can influence designers to make wise decisions about what kinds of art-efacts to develop and which ways of life to support; for example, whether or not we should design artefacts in line with Conventio-nal Development or Great Transition. I will do this by discussing a necessary reorganization of society and our way of living and how that may influence the design of the artefacts we choose to live with, not how design of artefacts may influence society. In this way, my research may be seen as contrary to most design research that departs from artefacts.

I will also distance myself from the kind of anthropocentric view that is expressed in Löwgren and Stolterman’s introduction. ”We live in an artificial world” (ibid., 1), our world is produced by humans, and the ”world as a place for human life” (ibid., 12). This is how most of us see, or frame, our life in the world today, as a relationship between humans and artefacts, with no relationship with the natural world at all. But our artificial world is totally dependent on the na-tural world, of its energy and physical resources. This isolation in our artificial world has also made it possible to avoid the conse-quences of our actions, for example, that our dear artefacts end up in the stomachs of seabirds. Of course, this human-centeredness is not limited to Interaction Design but is a component of all design and human action. However, factions within design do address this issue, and in this thesis, I will relate to the disciplines of Sustainable

CHI, Sustainable Interaction Design (Blevis 2007) and Collapse Informatics (Tomlinson et al. 2012a). Considering the next steps

for sustainable HCI, Silberman et al. (2014) state that sustainability issues are larger in scale, time span, and complexity than the scale and scope that traditional HCI design addresses. Therefore, HCI needs to reach out and collaborate with other disciplines. The his-torical HCI focus on introducing technological novelty may also be