Anti-VEGF treatment of patients with

diabetic macular edema

Studies of visual acuity, macular edema

and patient-reported outcomes

Therese Granström

Department of Medical Sciences 2016

Abstract

The aim of this thesis was to describe and evaluate visual acuity, macular edema and patient-reported outcomes (PRO) following anti-VEGF treatment of diabetic macular edema (DME) patients in a real-world setting. Using a longitudinal study design, a cohort of DME patients was followed from baseline to 1 year after treatment start. Data were collected from two eye clinics at two county hospitals. Social background characteristics, medical data and PRO were measured before treatment initiation, at four month and after 1 year. A total of 57 patients completed the study. Mean age was 69 years and the sample was equally distributed regarding sex. At baseline, the patients described their general health as low. One year after treatment initiation, 30 patients had improved visual acuity and 27 patients had no improvement in visual acuity. The patients whose visual acuity improved reported an improvement in several subscales in patient-reported outcome measures (PROM), which was in contrast to the group that experienced a decline in visual acuity, where there was no improvement in PROM. Out-comes from the study can be useful for developing and providing relevant information and support to patients undergoing this treatment.

List of Papers

This thesis is based on the following papers, which are referred to in the text by their Roman numerals.

I Granström, T., Forsman, H., Leksell, J., Jani, S., Modher Raghib, A., Granstam, E. (2015) Visual functioning and health-related quality of life in diabetic patients about to undergo anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment for sight-threatening macular edema. Journal of Diabetes and Its

Com-plications, 29(8), 1183-1190.

II Granström, T., Forsman, H., Lindholm Olinder, A., Gkretsis, D., Eriksson, J. W, Granstam, E. Leksell, J., (2016) Patient-reported outcomes and visual acuity in patients after 12 months of anti-VEGF-treatment for sight-threatening diabetic macular edema. In manus

Contents

Introduction ... 7

Diabetes mellitus ... 7

Diabetic retinopathy and macular edema ... 7

Treatment for diabetic macular edema ... 8

Laser treatment ... 8

Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment ... 8

Patient-reported outcomes ... 9

Quality of life ... 10

Health-related quality of life ... 10

Patient-reported outcome measures ... 10

National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire-25 questions ... 11

The Short Form-36 Health Survey ... 11

Rationale ... 13

Aims ... 14

Overall aim ... 14

Specific aims ... 14

Materials and methods ... 15

Setting for paper I and II ... 15

Study design, participants and procedure for paper I ... 15

Study design, participants and procedure paper II ... 16

Analyses study I ... 16

Analyses paper II ... 17

Abbreviations

BSE Better seeing eye

DM Diabetes Mellitus

DME Diabetic Macular Edema

DR Diabetic retinopathy

ETDRS Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study

HbA1c Glycated hemoglobin

HRQoL Health-Related Quality of Life

logMAR logarithm of the Minimum Angel of Resolution

NEI VFQ-25 National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire - 25 questions

OCT Optical coherence tomography

PRO Patient Reported Outcomes

PROM Patient Reported Outcome Measures

QoL Quality of Life

SF-36 The Short Form (36) Health Survey

VEGF Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

Introduction

Many chronic diseases can have an adverse impact on a patient’s daily life, although there are treatments available that can have clinically positive out-comes. Therefore, it is important to determine the patient’s perception of their disease and how it affects their daily life and function.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a disease that can lead to vision loss, which is the most feared complication (De Leo, Hickey, Meneghel, & Cantor, 1999; Watkins, 2003). In 2011, a new treatment for sight-threatening diabetic mac-ular edema (DME) was approved and we initiated a project to describe and evaluate visual acuity, macular edema and patient-reported outcomes (PRO) in a real-world setting.

Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes Mellitus is a glucose metabolism disorder characterized by high levels of blood glucose and the most common is DM type 2 (Nathan & Group, 2014). DM affects an increasing number of people worldwide (Antonetti, Klein, & Gardner, 2012) and in 2014, the global prevalence of DM was estimated to be 9 % of the adult population (WHO, 2014). This figure is expected to rise significantly in coming years (Wild, Roglic, Green, Sicree, & King, 2004). Consequently, the incidence of vision loss and blind-ness associated with DM is also expected to increase.

al., 2012; Nathan & Group, 2014; UKPDS, 1991; UKPDS & Group, 1998). Regular screening of DM patients can detect early sight threatening changes in the retina and treatment at this stage can help to limit subsequent vision loss (Olafsdottir et al., 2016).

Diabetic macular edema is a form of DR. DME is characterized by progres-sive retinal thickening that may ultimately affect the central macula, leading to deterioration of visual acuity (Bandello et al., 2010; Lang, 2012). More than 21 million people worldwide are affected by DME (Yau et al., 2012) and are at risk of suffering vision loss or blindness. Given the incidence of DME, a treatment that prevents deterioration of, stabilizes or improves visu-al acuity would have a significant globvisu-al benefit.

Treatment for diabetic macular edema

Laser treatment

Since 1985, laser treatment has been the standard treatment for DME. Laser treatment was shown to reduce the risk of severe vision loss and can achieve a reduction in moderate vision loss by approximately 50 % (ETDRS, 1985). However, relatively few patients experience significant improvement in vis-ual acuity after laser treatment and any improvement occurs slowly (Beck, Edwards, Aiello, & Bressler, 2009; Elman, Aiello, Beck, & Bressler, 2010; ETDRS, 1985; Mitchell et al., 2011). Laser treatment can be administered at an outpatient eye-clinic with no special preparations are required prior to the treatment and the patient can be discharged immediately afterwards. For many years, laser was the only treatment option available for DME, but since 2011, another treatment has become available (Mitchell et al., 2011).

Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment

Studies have demonstrated that anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) treatment is more effective at improving visual acuity in DME pa-tients when compared with laser treatment (Bandello, Berchicci, La Spina, Parodi, & Iacono, 2012; Ollendorf, Daniel, Jennifer, & Steven, 2013; Stefanini, Badaró, Falabella, & Koss, 2014) and has become the standard treatment for DME in recent years (Stewart, 2014). In 2010, it was reported that repeated intravitreal administration of a VEGF inhibitor, ranibizumab, reduced DME and improved visual acuity (Massin et al., 2010). Additional studies using ranibizumab or other anti-VEGF agents have reported similar findings (Brown et al., 2013; DRCRnet, 2015; Elman et al., 2010; Elman et al., 2012; Lang, Berta, Eldem, & Simader, 2013; Mitchell et al., 2011; Ngu-yen et al., 2012).

Intravitreal anti-VEGF is administered as an injection into the vitreous cavi-ty of the eye. Treatment is initiated as monthly injections and when the cen-tral macular edema measured with OCT and visual acuity measured with ETDRS is stable, the patient can receive further injections when needed. The injection is given under sterile conditions in an operating theater under topi-cal lotopi-cal anesthesia. This treatment regimen can be disadvantageous as it requires repeated visits to the eye clinic and patients may experience concern for the injections.

To our knowledge, there are few studies that examine the treatment outcome of anti-VEGF for DME in a real-world setting. Both the RESTORE study group (Mitchell, Bressler, Tolley, Gallagher, et al., 2013) and the Cochrane collaboration (Virgili, Parravano, Menchini, & Evans, 2014) also observed the need for studies in a real-world setting.

Patient-reported outcomes

The aim of using PRO is to obtain a report directly from the patient regard-ing their health (Deshpande, Rajan, Sudeepthi, & Abdul Nazir, 2011). Al-lowing the patient to report about their disease and treatment is a central aspect of the health care system and should be a key consideration in DM health care (Reaney, Black, & Gwaltney, 2014). PRO are an important way of enabling patients to report about their health (Cappelleri, Joseph, & An-drew, 2014) or the impact of treatment or disease (Fairclough, 2004). PRO add another dimension of knowledge to the health care system and this is important when evaluating or developing new treatments (Weldring & Smith, 2013).

The patient’s own reports can be emphasized if disease-specific measures are used in studies about visual impairment (Margolis, Coyne, Kennedy-Martin, & Baker, 2002; Massof & Rubin, 2001; Pesudovs, Burr, Harley, & Elliott, 2007; Rothman, Beltran, Cappelleri, Lipscomb, & Teschendorf,

Quality of life

WHO defines QoL as “the individual’s perception of their position in life in

the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns” (WHOQOL Group,

1997). There are many ways of defining QoL (Felce & Perry, 1995), as it is regarded as a broad multidimensional concept that includes subjective evalu-ations of both positive and negative aspects of life (WHOQOL Group, 1998). Having a chronic disease that may lead to vision loss can place a high burden on the individual patient and this can affect their QoL (Clarke, Si-mon, Cull, & Holman, 2006).

Health-related quality of life

Health-related QoL (HRQoL) focuses on the individual’s experience of psy-chological well-being, physical capacity and ability for social activities in relation to their perceived health. HRQoL is defined as the functional impact of a disease or its treatment (ISOQOL, 2016), and there are several defini-tions of HRQoL (Guyatt, Feeny, & Patrick, 1993). Since the 1980s, there has been a debate on finding a consensus regarding which aspects should be included under HRQoL (McHorney, 1999). It is important to measure HRQoL with regards to the patient’s own reports of the burden of their ill-ness or disease (Guyatt et al., 1993). Maintaining normal blood glucose lev-els is the goal of DM treatment but it is important that it is not done at the expense of a patient’s HRQoL.

Patient-reported outcome measures

Patient reported outcome measures (PROM) are used to assess a patient’s daily life, symptoms, functional status and their experiences of care (Black, 2013; Calvert et al., 2013). This can assist the health care system to provide relevant and adequate information to patients undergoing treatment. It is also important to determine what support the patient needs from the health care system. Choosing the most relevant PROM should be given the same im-portance as choosing medical outcomes when planning a study (McKenna, 2011).

Generic instruments are designed to be applicable across all diseases or con-ditions, different medical interventions and different population groups (Pat-rick & Deyo, 1989). Disease-specific instruments are designed to be more sensitive to disease and treatment-related changes (Wiebe, Guyatt, Weaver, Matijevic, & Sidwell, 2003). There are DM-specific (Bradley et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2010) and vision-specific PROM (Brose & Bradley, 2010;

Lam-oureux et al., 2007). A recently developed new form of PRO is item banking, which includes a list of items from many other PRO in the same item bank (Pesudovs, 2010). This may provide a more accurate way to measure the impact of DR (Fenwick et al., 2011). In this study, we chose a vision-specific PROM, the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire-25 questions (NEI VFQ-25) and a generic PROM, the Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36).

National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire-25

questions

The NEI VFQ-25 is the most widely used instrument to measure patient-reported visual function and has been used in previous studies of treatments for DR (Gabrielian, Hariprasad, Jager, Green, & Mieler, 2010; Loftus, Sul-tan, Pleil, & Macugen Study, 2011; Mangione et al., 2001). The question-naire has been validated for Swedish-speaking patients (Eriksson et al., 2008). The questionnaire consists of 25 questions divided into 11 vision-related subscales, including general vision, ocular pain, near activities, dis-tance activities, social functioning, mental health, role difficulties, depend-ency, driving, color vision, and peripheral vision. The questionnaire also includes a single item measuring general health and a composite score calcu-lation (Mangione et al., 1998; Mangione et al., 2001). The subscale scores are 0–100, where a higher score indicates better visual function (Mangione, 2000).

In some studies, the NEI VFQ-25 is described as measuring HRQoL (Var-ma, Wu, Chong, Azen, & Hays, 2006), while in other studies it is described as a measure of vision-related QoL (Gabrielian et al., 2010; Okamoto et al., 2014; Papageorgiou, Hardiess, Schaeffel, & Wiethoelter, 2007), vision-related function (Bressler et al., 2014) and visual function (Mitchell, Bress-ler, Tolley, & et al., 2013). In this study, we chose to use the term ‘visual function’ according to the manual for the NEI VFQ-25 (Mangione et al., 2001).

patients with DM type 2 with obese from a gender perspective (Svenningsson, Marklund, Attvall, & Gedda, 2011), in relation to different diets (Guldbrand, Lindström, Dizdar, & Bunjaku, 2014) and bariatric surgery (Wu, Enoch, Andrea, Simon, & Wing-Yee, 2015).

Rationale

The results of previous large randomized control trials have shown that anti-VEGF treatment has a clinically positive effect on DME, indicated by provement in visual acuity and a decrease in macular edema. It is now im-portant to describe the effect of anti-VEGF treatment in a real-world setting in Swedish clinical practice. It is also important to measure PRO to develop and provide relevant information and support for these patients.

Aims

Overall aim

The aim of this thesis was to describe and evaluate visual acuity, macular edema and PRO in relation to anti-VEGF treatment among patients with DME in a real-world setting.

Specific aims

Paper I

The aim of this study was to describe visual acuity, macular edema and PRO among patients with DME about to undergo anti-VEGF treatment.

Paper II

The aim of this study was to evaluate visual acuity, macular edema and PRO of anti-VEGF treatment among patients with DME at 12 months after treat-ment start.

Materials and methods

Setting for paper I and II

A longitudinal cohort study design was employed, which followed a group of DME patients at baseline, 4 months to 1 year. Data were collected from two eye clinics at two county hospitals in Sweden from May 2012 to Febru-ary 2015. All patients about to undergo anti-VEGF treatment with ranibi-zumab for sight-threatening DME who met the inclusion criteria were asked about participation in the study by an ophthalmologist. Criteria for inclusion were an age over 18 years, having no cognitive impairments and the ability to speak or understand the Swedish language without an interpreter.

Study design, participants and procedure for paper I

The first paper in this thesis presents basline data. Sixty-five patients were asked to participate in the study. Two patients declined to participate and four withdrew a short time after inclusion, leaving a total of 59 patients who completed the study I. All patients at the two eye clinics were assessed by an ophthalmologist and if they were found to be suitable to receive anti-VEGF treatment, they were informed about the study by the ophthalmologist at the clinic. The patients received written and oral information about the study. They also received information that participation in the study was voluntary and not linked to the treatment. All patients signed the consent form to con-firm their enrollment in the study. PROMs were assessed using the vision-specific NEI VFQ-25 and the generic SF-36.

Visual acuity was measured according to the Early Treatment Diabetic Reti-nopathy Study (ETDRS) letter chart at a distance of 2 meters or using a Snellen chart at 5 meters. ETDRS visual acuity (number of letters) was measured with the eyes planned for anti-VEGF treatment (Holladay, 1997). The ETDRS is a landmark study that defined the standardization of eye charts and visual acuity testing, resulting in the development of the ETDRS charts (ETDRS, 1985).

The degree of DR was categorized based on the worse eye as mild, moder-ate, severe, or proliferative (Wilkinson et al., 2003) The macular edema was defined according to the ETDRS (ETDRS, 1985). Measurement of retinal thickness by optical coherence tomography (OCT) was performed (Topcon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Visual impairment was categorized into three groups based on the patient’s better-seeing eye: normal vision logarithm of minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) ≤ 0.10; mild visual impairment logMAR 0.20–0.50; moder-ate/severe visual impairment logMAR ≥ 0.60.

Study design, participants and procedure paper II

All patients from study I were followed up at 4 month and 1 year after injec-tion start. The anti-VEGF treatment started with three injecinjec-tions, once a month and after the third initial injection the patient was examined frequent-ly, initially once a month. In conjunction with the examination, the ophthal-mologist decided if the patient would get an additional injection or come back for an examination the following month. When steady state was reached regarding the macular edema, the examinations were conducted less frequently.

Of the 59 patients, one patient withdrew after 4 months and one patient was diagnosed with secondary neovascular glaucoma and vitreous hemorrhage and was therefore excluded. Consequently, 57 patients completed study II.

Analyses study I

After verifying that the patient groups from the two eye clinics were equiva-lent regarding sociodemographic and medical characteristics, the patients were handled as one single cohort. Analyses were conducted on one treated eye per patient and the eye with the worst visual acuity was excluded in case a patient received anti-VEGF treatment in both eyes. Descriptive statistics were used for presenting patient demographics and characteristics. A p value ˂ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS (version 22, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analyses

Regarding the NEI VFQ-25, we calculated the scale conversions and sub-scale scores with 11 vision-related constructs plus additional single-item general health questions according to the manual (Mangione, 2000). The results from the SF-36 were obtained from the licensed software program (Maruish, 2011). For the subscales in the SF-36 and the NEI VFQ-25 mean scores, standard deviation (SD) and range were calculated.

We divided the cohort into subgroups according to visual impairment, de-gree of retinopathy and if treatment was planned for the better- or worse-seeing eye. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was then performed to exam-ine if there were any differences between the subgroups in relation to the NEI VFQ-25 and the SF-36. To examine differences between subgroups regarding visual impairment and treated eye in relation to the NEI VFQ-25 subscales, Tukey’s post hoc test was used.

Analyses paper II

In the first step we analyzed the total cohort. In the next step the cohort was divided into two subgroups; one group with patients with improved visual acuity and one group that showed no improvement in visual acuity. An im-provement of ≤ 5 ETDRS letters was considered clinically significant (Klein, Moss, Klein, Gutierrez, & Mangione, 2001). Analyses were conducted with one treated eye per patient as described in study I.

Changes in PROM in relation to the two patient subgroups were analyzed. The statistics and calculations for the NEI VFQ-25 and the SF-36 were per-formed as in study I. To identify if there were any changes over time in self-reported visual function (NEI VFQ-25) and self-self-reported HRQoL (SF-36), we used a paired t-test. Differences in HbA1c levels, OCT and ETDRS were assessed using Student’s t-test.

The analyses showed the same pattern regarding ETDRS and OCT at 4 months as well as in 12 months follow up. Therefore we decided to present the result from 1 year follow up.

Ethical considerations for study I and study II

Ethical approval was obtained from the regional ethics committee in Uppsala (No. 2011/264) and the clinical directors of the eye clinics and was conduct-ed in accordance with the tenets of the

Declaration of Helsinki (Helsinki, 2016) All patients obtained verbal and written information before they signed the consent form. The patients were informed that participation in the study was voluntary and that all data were to be kept confidential and untraceable. The patients were given a code number and the code key was kept in a safe place at the eye clinic. The ques-tionnaires were labeled with the code numbers. If the patients felt they need-ed to discuss the study, the consulting ophthalmologist was available to meet the patient on a regular basis at the eye clinic.

Results

Vision-related outcomes study I and II

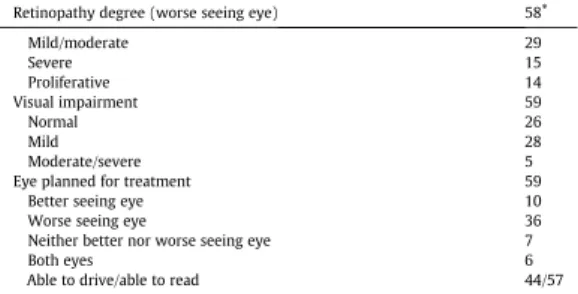

A total of 59 patients were enrolled in study I and patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Mean age was 68.5 years and the sample was equally dis-tributed regarding gender. Fifty-six percent of the patients had completed elementary school, 61 % were cohabitating and 66 % were retired. Type 2 DM was the most common type of DM and approximately 70 % of the pa-tients had two or more DM-related complications.

Vision-related baseline data showed that 25 % of the patients had prolifera-tive DR and 25 % severe DR. The remaining patients had normal or mild DR. For 61 % of the patients, the treatment was planned for the worse-seeing eye and almost 70 % of the patients had received previous laser treatment. Mean visual acuity measured with ETDRS was 63.9 (± 13.2) and mean cen-tral retinal thickness was 396 (± 129) µm.

Table 1 Characteristics of the patients at baseline

Variable Mean ± SD Range n

Age, years 68.5 (±10.0) 45-86 59 45-60 11 61-70 23 71-80 18 >80 7 Gender (male/female) 30/29 Education level Elementary school 33 Middle school 18 University 8 Marital status 56 Cohabiting (married) 36

Living alone (divorced/widow/widower) 20

Employment Retired 39 Working 16 Unemployed/sick leave 4 Type of diabetes Type 1 5 Type 2 54 HbA1c (mmol/mol) 68 (±16) 39-120 56

Duration of diabetes (years) 17 (± 10) 0-49 59

Lenght 167 (± 9) 150-186

Weight 83 (± 24) 47-159

Systolic blood pressure 151 (± 24) 100-240

Diastolic blood pressure 82 (± 11) 60-110

Diabetes treatment 59

Insulin/insulin pump (22/1) 23

Tablets 14

Insulin and tablets 22

Other medical treatment

Blood preassure treatment 48

Lipid treatment 36

Anticoagulantia 36

Hemodialysis 1

Number of late complications

1 19

2 28

≥3 12

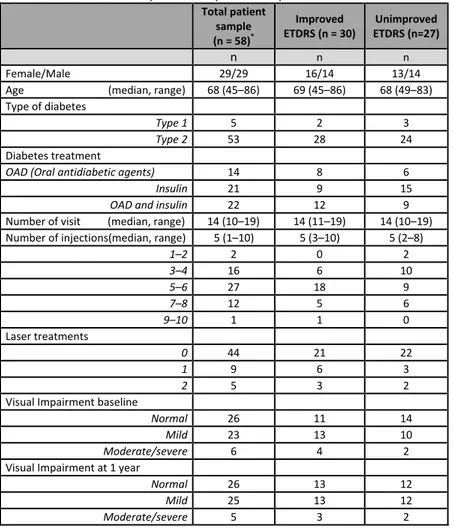

A total 57 patients completed the 1-year follow-up and patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The result for the total cohort showed a significant improvement in visual acuity and a significant decrease in retinal swelling (Table 3). We found that 30 patients had improved their ETDRS scores by more than five letters and 27 patients had not improved their ETDRS score. The distribution regarding number of injections was unequal though the me-dian were comparable. In the group of patients who showed no improvement

in visual acuity, there was a larger proportion that had insulin treatment. The median number of injections during the study period was five (Table 2). At 1-year follow-up, the two subgroups had similar visual acuity, although the mean improvement was 12 letters for the group with improved visual acuity and the mean decrease was 2 letters for the patients with non-improved visual acuity (Table 3).

Among those with no improvement we found 8 patients that showed a sig-nificant reduction of their visual acuity (≥ 5 letters ETDRS). What distin-guishes these patients from the others was that they had a higher mean age and had the largest increase in HbA1c levels, although it was not statistically significant (Table 4). One patient developed multiple diseases during the follow-up, whilst another patient fell and developed subdural bleeding dur-ing a visit. Two other patients suffered from relapsdur-ing macular edema caus-ing deterioration and were subsequently treated with intravitreal steroid im-plants.

At 4 month follow up the result showed an improvement of ETDRS and a decrease of OCT (data not shown). The result remained to one year follow up. We choose to only present the result from 1 year follow up.

Table 2 Characteristics of the patients at 1-year follow-up Total patient sample (n = 58)* Improved ETDRS (n = 30) Unimproved ETDRS (n=27) n n n Female/Male 29/29 16/14 13/14

Age (median, range) 68 (45–86) 69 (45–86) 68 (49–83)

Type of diabetes

Type 1 5 2 3

Type 2 53 28 24

Diabetes treatment

OAD (Oral antidiabetic agents) 14 8 6

Insulin 21 9 15

OAD and insulin 22 12 9

Number of visit (median, range) 14 (10–19) 14 (11–19) 14 (10–19)

Number of injections(median, range) 5 (1–10) 5 (3–10) 5 (2–8)

1–2 2 0 2 3–4 16 6 10 5–6 27 18 9 7–8 12 5 6 9–10 1 1 0 Laser treatments 0 44 21 22 1 9 6 3 2 5 3 2

Visual Impairment baseline

Normal 26 11 14

Mild 23 13 10

Moderate/severe 6 4 2

Visual Impairment at 1 year

Normal 26 13 12

Mild 25 13 12

Moderate/severe 5 3 2

* One patient was diagnosed with secondary neovascular glaucoma and vitreous hemorrhage and was excluded.

Table 3 Change from baseline to 12 months

Total sample Improved ETDRS

Unimproved ETDRS

Variables Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD

HbA1c Baseline 67 16 64 14 73 18 1 year 64 17 63 14 65 20 OCT Baseline 403 122 428 136 373 98 1 year 282 83 276 68 289 99 ETDRS Baseline 65.0 12.1 60.7 13.1 69.9 8.8 1 year 70.2 11.1 72.1 11.2 68.0 10.7

Table 4 Characteristics of patients with decreased visual acuity (n = 8)

Variables Mean SD HbA1c Baseline 79 26 1 year 53 4 OCT Baseline 390 141 1 year 275 63 ETDRS Baseline 68.6 11.8 1 year 59.5 12.7

Patient-reported outcomes study I and II

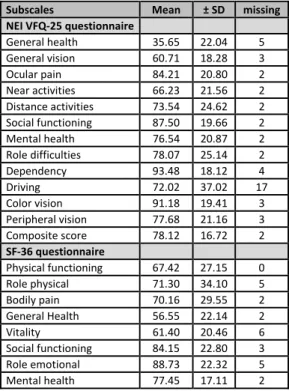

At baseline, the data from the NEI VFQ-25 and the SF-36 showed that the patients described their general health as low. The result from the NEI VFQ-25 showed that the patients had reported the highest subscales for dependen-cy, color vision and social functioning. Given that the patients’ experience of their social functioning was positive, they described themselves as relatively independent in their daily life. The result from the SF-36 showed that the subscale mental health received the highest score (Table 5).

At 1-year follow-up, the result for the total cohort showed significant im-provement for the NEI VFQ-25 subscales general health, general vision, near activities, distance activities and composite score. When we divided the cohort into patients with improved visual acuity and patients with no

im-Table 5 Scores for the NEI VFQ-25 and the SF-36 at baseline

Subscales Mean ± SD missing NEI VFQ-25 questionnaire General health 35.65 22.04 5 General vision 60.71 18.28 3 Ocular pain 84.21 20.80 2 Near activities 66.23 21.56 2 Distance activities 73.54 24.62 2 Social functioning 87.50 19.66 2 Mental health 76.54 20.87 2 Role difficulties 78.07 25.14 2 Dependency 93.48 18.12 4 Driving 72.02 37.02 17 Color vision 91.18 19.41 3 Peripheral vision 77.68 21.16 3 Composite score 78.12 16.72 2 SF-36 questionnaire Physical functioning 67.42 27.15 0 Role physical 71.30 34.10 5 Bodily pain 70.16 29.55 2 General Health 56.55 22.14 2 Vitality 61.40 20.46 6 Social functioning 84.15 22.80 3 Role emotional 88.73 22.32 5 Mental health 77.45 17.11 2

t h e NEI VF Q-25 a t 1-ye ar f o llo w-up

Total patient sam

p le Im pr oved ETDR S Non Improved ET DRS (n =27) (n = 58 )* (n = 30 ) Mean SD p-value Mean SD p-value Mean SD p-value Ba sel in e 36. 7 0 22. 0 2 .002 37. 5 0 24. 4 5 .004 36. 3 6 20. 0 1 .137 1 yea r 46. 8 1 21. 8 8 51. 0 4 18. 7 7 43. 1 8 24. 6 2 Ba sel in e 61. 1 8 18. 9 4 .001 57. 6 9 19. 0 4 .000 65. 8 3 18. 1 6 .747 1 yea r 67. 8 4 15. 0 1 69. 2 3 14. 1 2 66. 6 7 16. 3 3 sel in e 84. 7 2 20. 7 0 .077 80. 3 6 23. 9 2 .133 90. 5 0 15. 0 0 .548 1 yea r 88. 8 9 17. 1 1 85. 2 7 20. 4 3 92. 5 0 11. 9 7 Ba sel in e 66. 3 6 21. 4 1 .015 63. 3 9 18. 7 5 .015 69. 6 7 24. 4 0 .394 1 yea r 72. 9 2 20. 7 6 71. 8 8 20. 2 4 73. 3 3 21. 7 8 sel in e 73. 4 6 24. 9 4 .026 72. 4 7 23. 6 1 .008 74. 0 0 27. 1 4 .312 1 yea r 79. 5 5 21. 5 9 79. 7 6 21. 4 8 79. 1 7 22. 5 7 Ba sel in e 87. 2 6 19. 9 9 .184 86. 5 7 17. 9 9 .265 87. 5 0 22. 5 3 .461 1 yea r 89. 6 2 18. 6 3 89. 3 5 16. 5 2 89. 5 0 21. 2 5 Ba sel in e 76. 5 0 21. 3 1 .062 76. 1 2 22. 3 1 .127 78. 0 0 20. 2 6 .440 1 yea r 81. 6 4 17. 8 6 82. 8 9 16. 7 2 80. 5 0 19. 6 3 Ba sel in e 79. 4 0 23. 1 8 .523 79. 9 1 22. 4 0 .305 79. 0 0 24. 9 3 .873 1 yea r 78. 0 1 21. 8 5 76. 7 9 19. 7 5 78. 5 0 24. 3 5 Ba sel in e 93. 4 3 18. 6 2 .417 97. 2 2 6. 54 .314 89. 5 8 26. 1 5 .779 1 yea r 90, 8 7 21. 4 7 92. 9 0 20. 1 1 88. 1 9 23. 4 3 Ba sel in e 74. 6 6 35. 1 7 .789 75. 6 9 36. 2 5 .855 72. 9 2 35. 9 4 .772 1 yea r 75. 6 8 35. 1 0 77. 0 8 33. 5 5 73. 6 1 38. 3 2 Ba sel in e 91. 6 2 19. 0 5 .766 92. 5 9 13. 5 4 .490 90. 2 4 24. 1 1 .964 1 yea r 92. 4 6 16. 6 9 94. 4 4 12. 6 6 90. 0 0 20. 4 1 Ba sel in e 76. 9 2 24. 1 8 .282 75. 9 3 26. 3 9 .134 78. 1 3 22 50 .798 1 yea r 79. 9 2 24. 9 0 80. 5 6 23. 3 4 79. 4 2 27 52 sel in e 78. 3 0 16. 7 5 .039 77. 2 7 15. 7 4 .024 79. 5 7 18. 3 7 .611 1 yea r 81. 1 7 15. 9 1 81. 3 2 15. 1 0 80. 7 1 17. 3 3

Discussion

The results from this real-world study showed that overall, the cohort expe-rienced a significant improvement in visual acuity (≥ 5 ETDRS letters) 1 year after starting anti-VEGF treatment for DME. The result is comparable with (Mitchell et al., 2011) which presented a similar improvement. We choose to present the result regarding OCT, ETDRS and PROMs from base-line and 1 year follow-up as the result only showed a slight improvement between 4 months and 1 year. Regarding OCT similar findings was reported (Holm, Schroeder, & Lövestam Adrian, 2015).

When the cohort was divided into patients with improved visual acuity and patients with no improvement in visual acuity, the results showed that ap-proximately 50 % of the included patients had a clinically significant im-provement in their visual acuity after 1 year. This also highlights a notable discrepancy between this study and previous randomized controlled trials (Massin et al., 2010; Mitchell et al., 2011; Nguyen et al., 2010), where the cohort has not been divided into two subgroups. It is also important to note that this group had better visual acuity at baseline and consequently did not have the same potential for improvement.

A previous study have emphasized the importance of examining vision-related outcomes of anti-VEGF treatment for DME in a real-world setting (Virgili et al., 2014). The cohort in this study had a higher mean age com-pared with other studies (Brown et al., 2013; Korobelnik et al., 2014; Mitch-ell et al., 2011). Baseline visual acuity for the total cohort was higher than some studies (Korobelnik et al., 2014; Nguyen et al., 2012) but in line with the RESTORE study (Mitchell et al., 2011). This may indicate that the base-line level of visual acuity is of importance for the treatment outcome.

The retinal thickness for the total cohort was lower than in other studies (Massin et al., 2010; Nguyen et al., 2012), whilst the subgroup with no im-provement in visual acuity also had less macular swelling than what has been observed elsewhere (Massin et al., 2010; Mitchell et al., 2011; Nguyen et al., 2012). At 1-year follow-up, the two subgroups had similar levels of macular swelling.

At baseline, our study cohort had similar HbA1c levels as described in some studies (Brown et al., 2013; Korobelnik et al., 2014; Nguyen et al., 2012) but

higher levels than others (Matsuda et al., 2014). When the cohort was divid-ed into the two subgroups, we found that the group with no improvement in visual acuity had higher baseline level of HbA1c. At 1-year follow-up, the two subgroups had similar HbA1c levels. This may indicate that HbA1c levels at baseline could influence the treatment outcome, which is consistent with the results of another real-world study (Matsuda et al., 2014). In con-trast, a previous study found that HbA1c levels at baseline did not affect treatment outcomes (Bansal, Bansal, Khurana, Wieland, & Wang, 2015). Furthermore, we found eight patients who experienced a deterioration of their visual acuity after 1 year. What distinguishes these patients was that their HbA1c levels had decreased during the follow-up period, though the decrease was not significant.

The cohort in this study exhibited low general health before starting the anti VEGF-treatment (Granström et al., 2015), lower than in other studies (Bressler et al., 2014; Mitchell, Bressler, Tolley, Gallagher, et al., 2013; Turkoglu et al., 2015). At baseline, there were no differences for the patients whose visual acuity improved and those for whom it did not. Knowing that these patients demonstrated low general health is important as it can enable the health care system to develop and provide relevant support and infor-mation. After one year, the patients who improved their visual acuity also improved the score for several key subscales of the NEI VFQ-25which is in line with other (Mitchell et al., 2015). These patients experienced an im-proved general health, better visual acuity and found it easier to observe objects at near and far distances. It can be assumed that this is useful for patients in their everyday life. The patients in this study did not improve the composite score which has been demonstrated in another study (Bressler et al., 2014).

When compared with patients who demonstrated no improvement in visual acuity following treatment, those in whom visual acuity did not improve presented with poorer general vision and difficulties performing near activi-ties at baseline. Composite scores were stable from baseline to 1 year and were similar in the two subgroups. The composite score was higher than in

in their visual acuity after anti-VEGF treatment for DME. This must be fur-ther investigated so that patients do not need to undergo an injection regimen without achieving a clinically positive outcome, which is disruptive for the patient and a waste of health care resources. Thus, it is also important to determine the patients’ experience of the treatment and their visual impair-ment due to DME.

Methodological considerations

Study I and study II

The strength of this study was that the participants were patients who visited eye clinics for an examination in a real-world setting. When planning the study we estimated to include approximately 50 patients per eye-clinic. It was difficult to obtain the number of participants when the numbers of pa-tients who were considered for anti-VEGF treatment and met the inclusion criteria was lower than expected. There were no major differences in base-line data in this cohort compared with other studies, so it is possible to con-sider the result as a representative patient group in the real world.

Requests for participation in the study were sought from patients upon a regular visit to the eye clinic, where they received information about the anti-VEGF treatment. In some instances, the patients promptly responded to the surveys. In some cases, this could have led to stress for the patient, but staff at the clinic checked the questionnaire and ensured the patient was not at any imminent risk for misunderstanding. The patients had the opportunity to ask questions at the clinic and the response rate was good at baseline. The cohort was consecutively selected based upon the inclusion criteria’s. It was not ethically viable to include a control group when anti-VEGF treatment was available.

At follow-up, the questionnaires were sent by post to the patients who would then post the completed questionnaire back. One advantage of this procedure was that the patient was able to answer questions when it suited them. How-ever, the disadvantage of this approach is that it is easier to forget to answer the questions and return the questionnaires. A reminder with new question-naires was sent to the patients after a couple of weeks if needed. There were no resources available to answer the questionnaires in a phone interview with the patients for the 1-year follow-up.

In this study, there were numerous missing answers (n=17) for the NEI VFQ-25 subscale driving, however it is a known problem depending on the

question about general health in a vision context, as in the NEI VFQ-25, may lead to different responses than for the same question in a general context such as in SF-36. This may explain why the NEI VFQ-25 showed changes over time but the SF-36 did not.

Conclusions

This study was conducted in a real-world setting and showed that visual acuity was improved and retinal thickness was reduced in ap-proximately 50 % of patients who received anti-VEGF treatment for DME.

At baseline the cohort reported low general health.

The PROM showed that the patients with improved visual acuity re-ported improved general health at 1-year follow-up.

References

Antonetti, D. A., Klein, R., & Gardner, T. W. (2012). Diabetic Retinopathy. New

England Journal of Medicine, 366(13), 1227-1239.

doi:10.1056/NEJMra1005073

Bandello, Berchicci, L., La Spina, C., Parodi, M. B., & Iacono, P. (2012). Evidence for Anti-VEGF Treatment of Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmic Research,

48, 16-20. doi:10.1159/000339843

Bandello, Parodi, M. B., Lanzetta, P., & Loewenstein, A. (2010). Diabetic macular edema (pp. 73-110): Karger.

Beck, R. W., Edwards, A. R., Aiello, L. P., & Bressler, N. M. (2009). Three-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing focal/grid photocoagulation and in-travitreal triamcinolone for diabetic macular edema. Archives of ophthalmology

(1960), 127(3), 245. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2008.610

Black, N. (2013). Patient reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 346, 167.

Bourne, R. R. A., Jonas, J. B., Flaxman, S. R., Keeffe, J., Leasher, J., Naidoo, K., . . . Global Burden Dis, S. (2014). Prevalence and causes of vision loss in high-income countries and in Eastern and Central Europe: 1990-2010. British Journal

of Ophthalmology, 98(5), 629-638. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304033

Bradley, Todd, C., Gorton, T., Symonds, E., Martin, A., & Plowright, R. (1999). The development of an individualized questionnaire measure of perceived im-pact of diabetes on quality of life: the ADDQoL. Quality of Life Research, 8(1), 79-91. doi:10.1023/a:1026485130100

Bressler, N. M., Varma, R., Suñer, I. J., Dolan, C. M., Ward, J., Ehrlich, J. S., . . . Turpcu, A. (2014). Vision-Related Function after Ranibizumab Treatment for Diabetic Macular Edema: Results from RIDE and RISE. Ophthalmology,

121(12), 2461-2472.

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.07.008

Brose, & Bradley, C. (2010). Psychometric Development of the Individualized Reti-nopathy-Dependent Quality of Life Questionnaire (RetDQoL). Value in Health,

13(1), 119-127. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00589.x

Brown, D. M., Nguyen, Q. D., Marcus, D. M., Boyer, D. S., Patel, S., Feiner, L., . . . Hopkins, J. J. (2013). Long-term Outcomes of Ranibizumab Therapy for Dia-betic Macular Edema: The 36-Month Results from Two Phase III Trials: RISE and RIDE. Ophthalmology, 120(10), 2013-2022.

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.02.034

Calvert, M., Blazeby, J., Altman, D. G., Revicki, D. A., Moher, D., & Brundage, M. D. (2013). Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in randomized trials: the CONSORT PRO extension. JAMA, 309. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.879

Cappelleri, J. C., Joseph, C. C., & Andrew, G. B. (2014). Interpretation of patient-reported outcomes. Statistical methods in medical research, 23(5), 460-483. doi:10.1177/0962280213476377

Chen, E., Looman, M., Laouri, M., Gallagher, M., Van Nuys, K., Lakdawalla, D., & Fortuny, J. (2010). Burden of illness of diabetic macular edema: literature re-view. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 26(7), 1587-1597.

doi:10.1185/03007995.2010.482503

Cheung, N., Mitchell, P., & Wong, T. Y. (2010). Diabetic retinopathy. The Lancet,

376(9735), 124-136. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62124-3

Cheung, N., & Wong, T. Y. (2008). Diabetic retinopathy and systemic vascular complications. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research, 27(2), 161-176. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2007.12.001

Clarke, P. M., Simon, J., Cull, C. A., & Holman, R. R. (2006). Assessing the impact of visual acuity on quality of life in individuals with type 2 diabetes using the Short Form-36. Diabetes Care, 29(7), 1506-1511. Retrieved from

http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=c8h&AN=2009222320 &site=ehost-live

Coyne, K. S., Margolis, M. K., Kennedy-Martin, T., Baker, T. M., Klein, R., Paul, M. D., & Revicki, D. A. (2004). The impact of diabetic retinopathy: perspec-tives from patient focus groups. Family Practice, 21(4), 447-453.

doi:10.1093/fampra/cmh417

De Leo, D., Hickey, P. A., Meneghel, G., & Cantor, C. H. (1999). Blindness, Fear of Sight Loss, and Suicide. Psychosomatics, 40(4), 339-344.

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(99)71229-6

Deshpande, P. R., Rajan, S., Sudeepthi, B. L., & Abdul Nazir, C. P. (2011). Patient-reported outcomes: A new era in clinical research. Perspectives in Clinical

Re-search, 2(4), 137-144. doi:10.4103/2229-3485.86879

DRCRnet. (2015). Aflibercept, Bevacizumab, or Ranibizumab for Diabetic Macular Edema. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(13), 1193-1203.

doi:doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1414264

Elman, M. J., Aiello, L. P., Beck, R. W., & Bressler, N. M. (2010). Randomized Trial Evaluating Ranibizumab Plus Prompt or Deferred Laser or Triamcinolone Plus Prompt Laser for Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmology (Rochester,

Minn.), 117(6), 1064-1077.e1035. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.02.031

Elman, M. J., Qin, H., Aiello, L. P., Beck, R. W., Bressler, N. M., Ferris Iii, F. L., . . . Melia, M. (2012). Intravitreal Ranibizumab for Diabetic Macular Edema with Prompt versus Deferred Laser Treatment: Three-Year Randomized Trial Re-sults. Ophthalmology, 119(11), 2312-2318.

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.08.022

ETDRS. (1985). Photocoagulation for diabetic macular edema: Early treatment diabetic retinopathy study report number 1 early treatment diabetic retinopathy study research group. Archives of Ophthalmology, 103(12), 1796-1806.

Gabrielian, A., Hariprasad, S. M., Jager, R. D., Green, J. L., & Mieler, W. F. (2010). The utility of visual function questionnaire in the assessment of the impact of diabetic retinopathy on vision-related quality of life. Eye, 24(1), 29-35. doi:10.1038/eye.2009.56

Granström, T., Forsman, H., Leksell, J., Jani, S., Raghib, A. M., & Granstam, E. (2015). Visual functioning and health-related quality of life in diabetic patients about to undergo anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment for sight-threatening macular edema. Journal of diabetes and its complications, 29(8), 1183-1190. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.07.026

Guldbrand, H., Lindström, T., Dizdar, B., & Bunjaku, B. (2014). Randomization to a low-carbohydrate diet advice improves health related quality of life compared with a low-fat diet at similar weight-loss in Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes

research and clinical practice, 106(2), 221.

Guyatt, Feeny, & Patrick. (1993). Measuring Health-Related Quality of Life. Annals

of Internal Medicine, 118(8), 622-629.

doi:10.7326/0003-4819-118-8-199304150-00009

Helsinki, D. o. (2016). World medical association declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Retrieved from http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/

Holladay. (1997). Proper method for calculating average visual acuity. J Refract Surg,

13(4), 388-391. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9268940

Holm, K., Schroeder, M., & Lövestam Adrian, M. (2015). Peripheral retinal function assessed with 30-Hz flicker seems to improve after treatment with Lucentis in patients with diabetic macular oedema. Documenta ophthalmologica, 131(1), 43.

ISOQOL. (2016). International Society for Quality of Life Research. Retrieved from http://www.isoqol.org/

Jeppsson, J.-O., Kobold, U., Barr, J., Finke, A., Hoelzel, W., Hoshino, T., . . . Wey-kamp, C. (2002). Approved IFCC Reference Method for the Measurement of HbA1c in Human Blood Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (Vol. 40, pp. 78).

Klein, Knudtson, M. D., Lee, K. E., Gangnon, R., & Klein, B. E. K. (2008). The Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy XXII: The Twenty-Five-Year Progression of Retinopathy in Persons with Type 1 Diabetes.

Oph-thalmology, 115(11), 1859-1868.

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.08.023

Klein, Lee, Gangnon, R. E., & Klein, B. E. K. (2010). The 25-Year Incidence of Visual Impairment in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus The Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy. Ophthalmology, 117(1), 63-70.

doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.06.051

Klein, Moss, S. E., Klein, B. K., Gutierrez, P., & Mangione, C. M. (2001). The nei-vfq-25 in people with long-term type 1 diabetes mellitus: The wisconsin epide-miologic study of diabetic retinopathy. Archives of Ophthalmology, 119(5), 733-740. doi:10.1001/archopht.119.5.733

Korobelnik, J. F., Do, D. V., Schmidt-Erfurth, U., Boyer, D. S., Holz, F. G., Heier, J. S., . . . Brown, D. M. (2014). Intravitreal Aflibercept for Diabetic Macular Ede-ma. Ophthalmology, 121(11), 2247-2254. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.05.006 Lamoureux, E. L., Pallant, J. F., Pesudovs, K., Rees, G., Hassell, J. B., & Keeffe, J.

E. (2007). The Impact of Vision Impairment Questionnaire: An Assessment of Its Domain Structure Using Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Rasch Analysis.

Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 48(3), 1001-1006.

Lang. (2012). Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmologica, 227(Suppl. 1), 21-29. Retrieved from http://www.karger.com/DOI/10.1159/000337156

Lang, Berta, A., Eldem, B. M., & Simader, C. (2013). Two-Year Safety and Effica-cy of Ranibizumab 0.5 mg in Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmology

(Rochester, Minn.), 120(10), 2004-2012. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.02.019

Lilja, M., Jansson, S., Alvarsson, M., & Aldrimer, M. (2013). HbA1c blir komplette-rande metod för diagnostik av diabetes. Läkartidningen, 110(49-50), 2246. Linder, Chang, Scott, I. U., & et al. (1999). VAlidity of the visual function index

(vf-14) in patients with retinal disease. Archives of Ophthalmology, 117(12), 1611-1616. doi:10.1001/archopht.117.12.1611

Loftus, J. V., Sultan, M. B., Pleil, A. M., & Macugen Study, G. (2011). Changes in Vision- and Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Diabetic Macular Edema Treated with Pegaptanib Sodium or Sham. Investigative Ophthalmology

& Visual Science, 52(10), 7498-7505. doi:10.1167/iovs.11-7613

Mangione. (2000). The National Eye Institute 25-Item Visual Function Question-naire (VFQ-25) - version 2000. Retrieved from

https://www.nei.nih.gov/sites/default/files/nei-pdfs/manual_cm2000.pdf Mangione, Lee, P. P., Gutierrez, P. R., Spritzer, K., Berry, S., & Hays, R. D. (2001).

Development of the 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Question-naire. Archives of Ophthalmology, 119(7), 1050-1058. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://WOS:000169780200010

Margolis, Coyne, Kennedy-Martin, & Baker. (2002). Vision-Specific Instruments for the Assessment of Health-Related Quality of Life and Visual Functioning: A Literature Review. PharmacoEconomics, 20(12), 791-812.

Maruish, M. E. E. (2011). User’s manual for the SF-36v2 Health Survey (3rd ed.).Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated.

Massin, P., Bandello, F., Garweg, J. G., Hansen, L. L., Harding, S. P., Larsen, M., . . . Wolf, S. (2010). Safety and Efficacy of Ranibizumab in Diabetic Macular Edema (RESOLVE Study). Diabetes Care, 33(11), 2399-2405.

doi:10.2337/dc10-0493

Massof, & Rubin. (2001). Visual Function Assessment Questionnaires. Survey of

Ophthalmology, 45(6), 531-548.

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0039-6257(01)00194-1

McHorney. (1999). Health status assessment methods for adults: past accomplish-ments and future challenges. Annual review of public health, 20(1), 309-335. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.20.1.309

McKenna, S. P. (2011). Measuring patient-reported outcomes: moving beyond mis-placed common sense to hard science. BMC Medicine, 9(1), 1-12.

Mitchell, P., Massin, P., Bressler, S., Coon, C. D., Petrillo, J., Ferreira, A., & Bress-ler, N. M. (2015). Three-year patient-reported visual function outcomes in dia-betic macular edema managed with ranibizumab: the RESTORE extension study. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 31(11), 1967-1975. doi:10.1185/03007995.2015.1081880

Nathan, D. M., & Group, f. t. D. E. R. (2014). The Diabetes Control and Complica-tions Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes IntervenComplica-tions and ComplicaComplica-tions Study at 30 Years: Overview. Diabetes Care, 37(1), 9-16. doi:10.2337/dc13-2112 Nguyen, Q. D., Brown, D. M., Marcus, D. M., Boyer, D. S., Patel, S., Feiner, L., . . .

Ehrlich, J. S. (2012). Ranibizumab for Diabetic Macular Edema: Results from 2 Phase III Randomized Trials: RISE and RIDE. Ophthalmology, 119(4), 789-801. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.12.039

Nguyen, Q. D., Shah, S. M., Khwaja, A. A., Channa, R., Hatef, E., Do, D. V., . . . Campochiaro, P. A. (2010). Two-Year Outcomes of the Ranibizumab for Ede-ma of the mAcula in Diabetes (READ-2) Study. Ophthalmology, 117(11), 2146-2151. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.08.016

Okamoto, Y., Okamoto, F., Hiraoka, T., & Oshika, T. (2014). Vision-related quality of life and visual function following intravitreal bevacizumab injection for per-sistent diabetic macular edema after vitrectomy. Japanese Journal of

Ophthal-mology, 58(4), 369-374. doi:10.1007/s10384-014-0323-7

Olafsdottir, E., Andersson, D. K. G., Dedorsson, I., Svärdsudd, K., Jansson, S. P. O., & Stefánsson, E. (2016). Early detection of type 2 diabetes mellitus and screen-ing for retinopathy are associated with reduced prevalence and severity of reti-nopathy. Acta Ophthalmologica. doi:10.1111/aos.12954

Ollendorf, D. A., Daniel, A. O., Jennifer, A. C., & Steven, D. P. (2013). COMPAR-ATIVE EFFECTIVENESS OF ANTI-VEGF AGENTS FOR DIABETIC MACULAR EDEMA. International journal of technology assessment in health

care, 29(4), 392-401. doi:10.1017/S0266462313000500

Papageorgiou, E., Hardiess, G., Schaeffel, F., & Wiethoelter, H. (2007). Assessment of vision-related quality of life in patients with homonymous visual field de-fects. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology, 245(12), 1749-1758. doi:10.1007/s00417-007-0644-z

Patrick, D. L., & Deyo, R. A. (1989). Generic and Disease-Specific Measures in Assessing Health Status and Quality of Life. Medical Care, 27(3), S217-S232. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.www.bibproxy.du.se/stable/3765666 Pesudovs. (2010). Item Banking: A Generational Change in Patient-Reported

Out-come Measurement. Optometry and Vision Science, 87(4), 285-293. doi:10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181d408d7

Pesudovs, Burr, Harley, & Elliott. (2007). The Development, Assessment, and Se-lection of Questionnaires. Optometry & Vision Science, 84(8), 663-674. doi:10.1097/OPX.0b013e318141fe75

Reaney, M., Black, P., & Gwaltney, C. (2014). A Systematic Method for Selecting Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Diabetes Research. Diabetes Spectrum,

27(4), 229-232. doi:10.2337/diaspect.27.4.229

Rothman, M. L., Beltran, P., Cappelleri, J. C., Lipscomb, J., & Teschendorf, B. (2007). Patient-Reported Outcomes: Conceptual Issues. Value in Health, 10, Supplement 2, S66-S75. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00269.x

Sharma, S., Oliver-Fernandez, A., Liu, W., Buchholz, P., & Walt, J. (2005). The impact of diabetic retinopathy on health-related quality of life. Current opinion

in ophthalmology, 16(3), 155-159. Retrieved from

http://journals.lww.com/co-ophthalmology/Fulltext/2005/06000/ The_impact_of_diabetic_retinopathy_on.4.aspx

Stefanini, F. R., Badaró, E., Falabella, P., & Koss, M. (2014). Anti-VEGF for the management of diabetic macular edema. Journal of immunology research,

2014(8), 1-8. doi:10.1155/2014/632307

Stewart, M. (2014). Anti-VEGF Therapy for Diabetic Macular Edema. Current

Diabetes Reports, 14(8), 1-10. doi:10.1007/s11892-014-0510-4

Sullivan, M., Karlsson, J., & Ware, J. E. (1995). The Swedish SF-36 Health Survey 1. Evaluation of data quality, scaling assumptions, reliability and construct-validity across general populations in Sweden. Social Science & Medicine,

41(10), 1349-1358. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(95)00125-q

Svenningsson, I., Marklund, B., Attvall, S., & Gedda, B. (2011). Type 2 diabetes: perceptions of quality of life and attitudes towards diabetes from a gender perspective. Scandinavian journal of caring sciences, 25(4), 688.

Turkoglu, E. B., Celık, E., Aksoy, N., Bursalı, O., Ucak, T., & Alagoz, G. (2015). Changes in vision related quality of life in patients with diabetic macular edema: Ranibizumab or laser treatment? Journal of diabetes and its complications,

29(4), 540-543. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.03.009

UKPDS. (1991). UK prospective diabetes study (UKPDS). Diabetologia, 34(12), 877-890. doi:10.1007/BF00400195

UKPDS, & Group, U. P. D. S. (1998). Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). The Lancet, Volume

352 No. 9131(p 837–853).

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07019-6

Ware, J., & Sherbourne, C. (1992). The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care, 30, 473 - 483. Varma, R., Wu, J., Chong, K., Azen, S. P., & Hays, R. D. (2006). Impact of Severity

and Bilaterality of Visual Impairment on Health-Related Quality of Life.

Ophthalmology, 113(10), 1846-1853.

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.04.028

Watkins, P. J. (2003). Abc Of Diabetes: Retinopathy. BMJ: British Medical Journal,

326(7395), 924-926. Retrieved from

http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.its.uu.se/stable/25454302

Weldring, T., & Smith, S. M. S. (2013). Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs) and Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs). Health services insights, 6, 61-68. doi:10.4137/HSI.S11093

WHO. (2014). GLobal Status report on noncommunicablr diseases. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/148114/1/9789241564854_eng.pdf Wiebe, S., Guyatt, G., Weaver, B., Matijevic, S., & Sidwell, C. (2003). Comparative

Wu, E., Enoch, W., Andrea, L., Simon, K. H. W., & Wing-Yee, S. (2015). Health-Related Quality of Life after Bariatric Surgery and its Correlation with Glycaemic Status in Hong Kong Chinese Adults. Obesity surgery, 26(3), 538-545. doi:10.1007/s11695-015-1787-3

Yau, J. W. Y., Rogers, S. L., Kawasaki, R., Lamoureux, E. L., Kowalski, J. W., Bek, T., . . . Group, o. b. o. t. M.-A. f. E. D. S. (2012). Global Prevalence and Major Risk Factors of Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetes Care. doi:10.2337/dc11-1909

Visual functioning and health-related quality of life in diabetic patients about to undergo anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment for sight-threatening macular edema

Therese Granströma, b,⁎, Henrietta Forsmana, Janeth Leksellb, Siba Janic,

Aseel Modher Raghibd, Elisabet Granstamc, e

aSchool of Education, Health and Social Studies, Dalarna University, Falun, Sweden bDepartment of Medical Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

cCenter for Clinical Research Västmanland County Hospital, Uppsala University/County Council of Västmanland, Västerås, Sweden dDepartment of Ophthalmology, Dalarna County Hospital, Falun, Sweden

eDepartment of Ophthalmology, Västmanland County Hospital, Västerås, Sweden

a b s t r a c t a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history: Received 9 July 2015

Received in revised form 29 July 2015 Accepted 31 July 2015

Available online 1 August 2015

Keywords:

Patient-reported measurements Health-related quality of life Visual function Diabetic macula edema Anti-VEGF treatment

Purpose: To examine patient-reported outcome (PRO) in a selected group of Swedish patients about to receive anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) treatment for diabetic macular edema (DME).

Material and methods: In this cross-sectional study, 59 patients with diabetes mellitus, who regularly visited the outpatient eye-clinics, were included. Sociodemographic and clinical data were collected and the patients completed PRO measures before starting anti-VEGF treatment. PRO measures assessed eye-specific outcomes (NEI-VFQ-25) and generic health-related quality of life (SF-36).

Results: The participants consisted of 30 men and 29 women (mean age, 68.5 years); 54 (92%) patients had type 2 diabetes; 5 (9%) patients had moderate or severe visual impairment; 28 (47%) were classified as having mild visual impairment. Some of the patients reported overall problems in their daily lives, such as with social relationships, as well as problems with impaired sight as a result of reduced distance vision.

Conclusions: Further studies are needed to investigate PRO factors related to low perceived general health in this patient population. It is important to increase our understanding of such underlying mechanisms to promote improvements in the quality of patient care.

© 2015 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Inc. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a lifelong disease affecting an increasing number of people worldwide (International Diabetes Federation, n.d.). Diabetes is

Trial and Follow-up Study; Lutty, 2013; Stratton et al., 2001; UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS), 1991). Diabetic microvascular disease of the macula may induce macular edema, which can severely reduce visual acuity. The prevalence of diabetic macular edema (DME)

Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications 29 (2015) 1183–1190

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications

Diabetic Retinopathy Study Report number 1. Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study research group, 1985) clinically significant DME is sight threatening and requires treatment. Fig. 1 shows a fundus and optical coherence tomography (OCT) with moderate DME compared with a healthy fundus and macular OCT. Laser therapy was established in 1985 and has been shown to reduce the risk of severe vision loss by 50% (Photocoagulation for diabetic macular edema: Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Report number 1. Early Treatment Diabetic Retinop-athy Study research group, 1985). However, improvement in visual acuity by laser treatment is limited (Beck et al., 2009). In 2010, it wasfirst reported that repeated intravitreal administration of ranibizumab, an inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), reduces macular edema and improves visual acuity in patients with visual impairment as a result of DME (Massin et al., 2010). Other studies using ranibizumab (Elman, Elman, Aiello, Beck, & Bressler, 2010; Mitchell et al., 2011; Nguyen et al., 2012) and another inhibitor of VEGF, aflibercept (Do, Nguyen, Boyer, & Schmidt-Erfurth, 2012), have reported similarfindings. A strong association between visual acuity and patient-reported visual function independent of the severity of retinopathy and other compli-cations has been found in diabetic patients (Gonder et al., 2014; Hirai, Tielsch, Klein, & Klein, 2011; Klein, Moss, Klein, Gutierrez, & Mangione, 2001; Trento et al., 2013; Tsilimbaris, Kontadakis, Tsika, Papageorgiou, & Charoniti, 2013). The improvement in visual acuity induced by anti-VEGF treatment for DME observed in pivotal clinical trials has been found to be associated with enhanced visual function measured with the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire-25 (NEI VFQ-25) (Bressler et al., 2014; Korobelnik et al., 2014; Mitchell, Bressler, Tolley, et al., 2013), especially if the better-seeing eye has been treated (Bressler et al., 2014; Mitchell et al., 2013).

In Sweden, intravitreal administration of anti-VEGF drugs for sight-threatening DME is now part of routine clinical care. Previously, health-related quality of life and visual function were investigated in Swedish diabetic patients participating in a screening program for diabetic retinopathy (Heintz, Wirehn, Peebo, Rosenqvist, & Levin, 2012). However, information is limited about patient-reported health-related quality of life and visual function in patients with DME about to undergo intravitreal anti-VEGF treatment for visual impairment.

1.1. Aims of this cross-sectional study

• To describe visual function (NEI VFQ-25) and patient-reported health-related quality of life (36-item short-form health survey

[SF-36]) in a cohort of Swedish diabetic patients about to undergo anti-VEGF treatment for visual impairment due to DME in routine clinical care.

• To explore the relationship between patient-reported visual function and health-related quality of life with regard to visual impairment, degree of retinopathy, and whether treatment was planned for the better- or worse-seeing eye.

• To analyze the correlation between the two different objective measurements of visual acuity.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

This study enrolled participants with diabetes of either sex aged 18 years or older who were about to receive treatment with ranibizumab (Lucentis) for visual impairment due to DME. The patients had to be Swedish speaking and have the cognitive ability to complete the surveys and participate in an interview. Enrollment took place from May 2012 to February 2014 at two county hospitals in Sweden. We excluded patients who had previously been treated with intravitreal anti-VEGF for DME. All patients who met the inclusion criteria were asked about study participation.

2.2. Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala, Sweden, and was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The participants obtained written and verbal information related to the study. All the participants gave their written informed consent. The data were labeled using code numbers and were handled with respect for the participants’ privacy and integrity. 2.3. Clinical assessment

Social background characteristics, including age, weight, sex, level of education, marital status, and information about employment or retirement status, were collected from all patients by interview. Data about the duration of diabetes, diabetes treatment, and late diabetic complications were obtained from medical records. Late complications included retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, and macrovascular disease (previous stroke, transitory ischemic attack, or myocardial

Fig. 1. Left: male individual, aged 67 years, moderate diabetic retinopathy and diabetes macular edema in the right eye; visual acuity ETDRS 70, corresponding to logMAR 0.4. Right: healthy fundus and macular OCT in 51-year-old female individual.

infarction). Blood pressure was measured, and glycosylated hemoglobin (Lilja et al., 2013) level was obtained from electronic patient records. The patients also specified their number of late diabetic complications.

The initial eye examination included measurement of best-cor-rected visual acuity with the ETDRS or Snellen chart, slit-lamp examination of the anterior segment, intraocular pressure measure-ment, fundus biomicroscopy, and measurement of retinal thickness by OCT (Topcon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

We performed grading of diabetic retinopathy with indirect ophthal-moscopy as follows: mild non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR); moderate NPDR; severe NPDR; or proliferative diabetic retinopathy (Wilkinson et al., 2003). Clinically, significant diabetic macular edema was defined according to ETDRS (Photocoagulation for diabetic macular edema: Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Report number 1. Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study research group, 1985). Based on the patient’s better-seeing eye, visual impairment was categorized into three groups: normal vision logarithm of minimum angle of resolution (logMAR)≤0.10; mild visual impairment logMAR 0.20–0.50; and moderate/severe visual impairment logMAR≥0.60. The degree of diabetes retinopathy was categorized based on the worse-seeing eye as mild/ moderate, severe, or proliferative.

All the patients received two questionnaires– NEI VFQ-25 and SF-36– at baseline. The patients could choose either to answer the questionnaires at the clinic or to take them home, answer them there, and return the completed forms by mail to the clinic.

2.4. Questionnaires

The eye-specific questionnaire, NEI VFQ-25, reflects the respondent’s self-reported visual function in subscales: general health; general vision; ocular pain; near activities; distance activities; driving; color vision; peripheral vision and social functioning; role difficulties; and dependency (Mangione et al., 2001; Mangione et al., 1998). The instrument has been validated for Swedish-speaking patients in the EMGT-study (Eriksson, Sjöstrand, & Kroksmark, 2008). We employed the manual for scoring (Mangione, 2000). The subscale scores were 0–100, where a higher NEI VFQ-25 score indicates better visual functioning.

The SF-36 (Maruish) measures eight dimensions of health-related quality of life: physical function; role functioning (physical limita-tions); bodily pain; general health; vitality; social function; role functioning (emotional limitations); and mental health. The SF-36 has been validated and translated into Swedish (Sullivan, Karlsson, & Ware, 1995). This survey was designed for self-administration (Ware & Sherbourne, 1992).

2.5. Methods for measuring visual acuity

We measured visual acuity either according to the ETDRS using the ETDRS letter chart at a distance of 2 m or using the Snellen chart at 5 m.

Mean scores, standard deviation (SD), and range were calculated for the subscales in SF-36 and NEI VFQ-25. We used analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine the relationship between NEI VFQ 25 and SF-36 with regard to visual impairment, degree of retinopathy, and whether treatment was planned for the better- or worse-seeing eye. We employed the Spearman correlation analysis to analyze the correlation between ETDRS and logMAR values. Tukey’s post hoc test was used to determine subgroup differences.

3. Results

3.1. Study subjects

We enrolled 63 patients in this study. Two patients declined participation, and four patients discontinued participation after inclusion. In all, 59 patients completed the study.

3.2. Patient demographics and characteristics

Sociodemographics and clinical characteristics of the included partic-ipants appear in Table 1. The study sample was equally distributed regarding sex. The mean age was 68.5 (±10.0) years. Over half the participants had completed elementary school, and eight had attained university-level education. Most of the participants (64%) were cohabiting. The majority of participants (66%) had retired. Of the patients, 54 (92%) had type 2 diabetes. Regarding late diabetic complications, including DME, 40 (68%) patients had two or more late complications (Table 1).

Table 1

Sociodemographics and clinical characteristics of the subjects.

Variable Mean ± SD range N

Age, years 68.5 (±10.0) 45–86 59 45–60 11 61–70 23 71–80 18 N80 7 Gender 59 Male/female 30/29 Education level 59 Elementary school 33 Middle school 18 University 8 Marital status 56 Cohabiting (married) 36

Living alone (divorced/widow/widower) 20

Employment 59 Retired 39 Working 16 Unemployed/sick leave 4 Type of diabetes 59 Type 1 5 1185 T. Granström et al. / Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications 29 (2015) 1183–1190