How have the grocery shopping practices of

university students in Jönköping been impacted

by the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study

Master Thesis in Business Administration, Number of credits: 15hp Program of study: International Marketing Authors: Aqsaa Bidiwala & Melanie Fijnheer Tutor: Songming Feng Jönköping, May 2021

2

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge and express our sincerest gratitude to everyone who supported us when writing this dissertation and contributed to its success.

First and foremost, we would like to extend our gratitude to our tutor, Songming Feng, who has guided and supported us throughout the entire process and provided us with excellent knowledge and valuable feedback that helped to improve this research.

Secondly, we would like to extend our gratitude towards all of the informants that volunteered to participate in this study which enabled us to carry out this research. We would also like to say a big thank you to Artem Syniuk, who on multiple occasions provided us with very helpful and constructive criticism that showed us a different perspective on the subject which allowed us to improve this research.

Lastly, we would like to thank Marcela Ramirez-Pasillas for providing us with useful guidelines and information throughout the course of writing this paper.

Thank you.

_____________________ _____________________

Aqsaa Bidiwala Melanie Fijnheer

Jönköping International Business School May 24, 2021

3

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: How have the grocery shopping practices of university students in Jönköping been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study

Authors: Aqsaa Bidiwala and Melanie Fijnheer Tutor: Songming Feng

Date: 2021-05-24

Key terms: practice theory, consumption, grocery shopping, COVID-19, pandemic, consumer behavior, university students, Jönköping

________________________________________________________________________ Abstract

With the COVID-19 pandemic taking over the world faster than anyone had anticipated and creating a ‘new normal’, consumers had to adapt and get used to these changes. The pandemic caused lockdowns in several parts of the world, where businesses, schools, and stores had to shut their doors, although essential stores such as grocery stores remained open. Not only did this happen, but consumers' social life was also impacted as they were asked to stay at home and limit their contact with other people. The COVID-19 pandemic caused a shift in the practices of consumers, with food and safety being one of the most essential needs, consumers converted to stockpiling on food and hygienic products which led to a lower on shelf availability in grocery stores. Even though many countries around the world imposed a lockdown, Sweden never imposed any lockdown during the COVID-19 period, making it an interesting country to research. Although Sweden did implement some measures which for all public areas meant a limited amount of people allowed in the store, whereas other measures were more focused on recommendations such as keeping distance, avoiding large crowds, and working and studying from home as much as possible. Ultimately, the COVID-19 pandemic did impact university students in Sweden, as student life completely stopped on campus and classes were partly given through Zoom. The city of Jönköping is a city where many students live, and over 19.000 students are registered at the university of Jönköping. These students are in a crucial stage of their life where new experiences and changes are happening. This initiated the purpose of the study to research whether the 19 pandemic has changed the grocery shopping practices of students pre and during the COVID-19 pandemic in the city of Jönköping. To perform the research a qualitative study has been conducted. An interview was formulated after reviewing the literature to gather information from university students in Jönköping, where the aim was to analyze their grocery shopping practices before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. A total of 15 university students were interviewed, in the age range of 23-26, who all study and live in the city of Jönköping during the pandemic. To study the practices of the students, the framework of Arsel and Bean (2013) has been applied. The objects and doings of the students pre and during COVID-19 have been researched and analyzed, and from the collected data, categories of meanings have been identified to analyze the meanings of the objects that were used and the doings that were performed by the informants. Changes in practices were identified in which the students mainly kept the same grocery shopping routine with adaptations to protect themselves against the virus. The grocery stores are visited less frequently,

4 and items are avoided out of fear of getting infected. The main practices identified is that the students started to wash their hands, keep distance, and started to use hand sanitizer as protective measures. This thesis provides a guide for governmental institutions on how consumers react to regulations during a pandemic. Also, this may help grocery stores to know how consumers adapt their grocery shopping practices amidst a pandemic.

5

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ... 7 1.1 Background ... 7 1.2 Research context ... 8 1.2.1 COVID-19 in Sweden ... 81.2.2 Jönköping University (JU) students ... 8

1.2 Problem Discussion ... 9

1.4 Purpose and Research Questions ... 10

2. Literature review ... 11

2.1 Consumer behavior during COVID-19 ... 11

2.2 Consumer grocery shopping behavior ... 13

2.3 Practice theory ... 15

2.3.1 Consumption and practice ... 16

2.3.2 The practice circuit of Arsel and Bean (2013) ... 17

3. Methodology ... 20 3.1 Research Philosophy ... 20 3.2 Research Approach ... 20 3.3 Research Strategy ... 20 3.4 Data collection ... 21 3.4.1 Semi-structured interviews ... 21

3.4.2 Design of the interview guide ... 21

3.4.3 Population and Sampling ... 22

3.5 Data Analysis ... 24 3.6 Research Quality ... 24 3.6.1 Credibility ... 24 3.6.2 Transferability ... 24 3.6.3 Dependability ... 24 3.6.4 Confirmability ... 25 3.6.5 Ethical Considerations ... 25

4. Findings and Analysis ... 26

4.1 Objects ... 26

4.1.1 Objects pre-COVID-19 ... 26

6

4.1.3 Comparison of objects ... 29

4.2 Doings ... 30

4.2.1 Doings pre-COVID-19 ... 30

4.2.2 Doings during COVID-19 ... 32

4.2.3 Comparison of doings ... 36

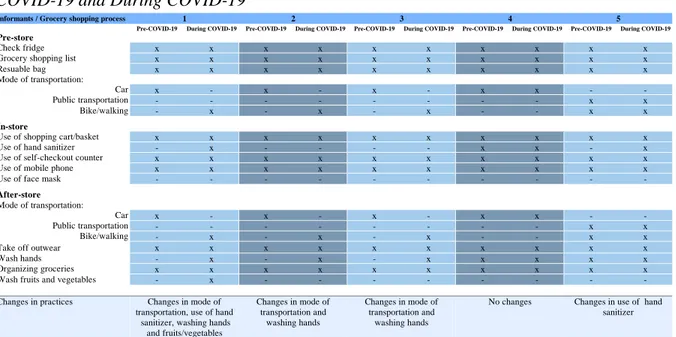

4.2.4 Comparison of Grocery shopping process ... 38

4.3 Meanings ... 40

4.3.1 Categories of meanings pre-COVID-19 ... 40

4.3.2 Categories of meanings during COVID-19 ... 41

4.4 Comparison of Categories for Meaning ... 42

5. Conclusion ... 46 6. Discussion ... 47 6.1 Managerial Implications ... 47 6.2 Limitations ... 47 6.3 Future Research ... 47 Bibliography ... 49 Appendices ... 55

Appendix 1: Consent Form ... 55

Appendix 2: Interview guide ... 58

Appendix 3: Tables of comparison of objects ... 60

Appendix 4: Tables of comparison of doings ... 61

Appendix 5: Tables of comparison of the grocery shopping process ... 63

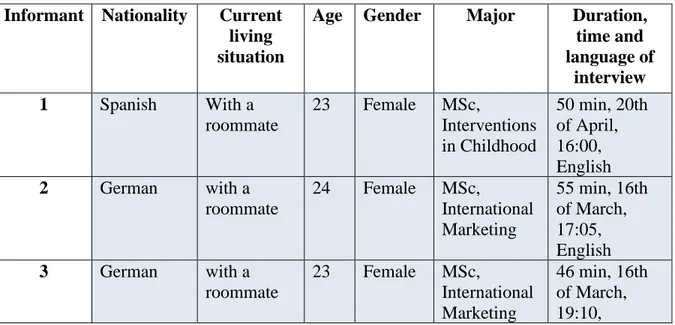

List of tables: Table 1: Table of Informants ... 22

Table 2: Comparisons of meanings in grocery shopping practices of he two periods ... 43

List of figures: Figure 1: An illustrated example of how taste regimes regulate practice (Arsel and Bean, 2013, p.910). . 19

Figure 2: Overview of changes in Objects ... 29

Figure 3: Overview of changes in Doings ... 37

7

1. Introduction

_____________________________________________________________________

This chapter introduces the background of the research topic, which is followed by the research context and problem discussion where the importance of this research will be further discussed. Lastly, the purpose of this thesis is presented together with the research question that this study attempts to answer.

_____________________________________________________________________

1.1 Background

The COVID-19 virus has spread quickly and turned the world upside down in a matter of a few months and the World Health Organization (WHO) (2020) declared a public health emergency on the 30th of January 2020. From November 2019 until February 2021, it has been over a year since the first case was reported in the city of Wuhan, China (Taylor, 2021) and roughly 102 million people around the world have been infected with the virus (Worldometer, 2021). As a result of the pandemic, several countries announced lockdowns and took serious measures in order to minimize the spread of the virus and the European borders were closed for international travel (Taylor, 2021). Furthermore, several recommendations have been given by WHO (2021) such as keeping distance, wearing a face mask, limiting the number of people at gatherings and events, and urging people to stay at home if they had any COVID-19 related symptoms. To follow the recommendations all Nordic countries, except for Sweden, decided for a lockdown and closed all stores, restaurants, businesses and other public places. Sweden chose not to announce a lockdown and kept all places open, although, to follow the recommendations given by WHO, the country incorporated specific measures that needed to be followed (Krisinformation, n.d, 2021). While the spread of the COVID-19 virus has developed very fast, several variants have also been found in different parts of the world, which according to Gray (2021) are far more aggressive and transmits faster. With this development, the recommendations in Sweden stayed the same where the focus was on people being encouraged to wear face masks in public transportation, and to meet and come in contact with as few people as possible (Krisinformation, 2021b; Krisinformation, 2021c).

Due to the governmental recommendations, stores and public events were affected, and people's everyday life was disrupted as many had to work remotely and schools and universities switched to online learning. This situation also brought changes in how people behave as they now were encouraged to stay at home and to avoid meeting too many people. When it comes to grocery shopping, prior to the outbreak, consumers did not have to face any fears or threats when physically visiting the stores and could be assured that most products would be available at their local store (Martin-Neuninger and Ruby, 2020). However, the pandemic caused a shift in the behavior of consumers as they started to visit the stores less frequently and started to spend more money during each visit. Furthermore, more consumers have moved to online shopping rather than physically visiting the stores (Ramos, 2020). Nonetheless, if the behavior of these consumers will change or remain unchanged after the COVID-19 pandemic is unpredictable (Puttaiah et al., 2020).

8

1.2 Research context

1.2.1 COVID-19 in Sweden

In December 2020 Sweden witnessed more than 8,000 deaths due to COVID-19, which was discussed in the media in different parts of the world, and it was also heavily criticized by neighboring countries where Sweden was criticized for adopting a very loose policy. Although, Sweden argued that the aim of their approach was to create herd immunity, which is why no lockdown was introduced (Claeson and Hanson, 2020). As of the 26th of January 2021, Sweden

introduced new regulations to prevent the spread of COVID-19: limited number of guests allowed in public spaces, recommendation to wear a face mask in public transportation during rush hour, shutdown of public buildings and an entry ban from non-EU countries (Krisinformation, 2021a). With the escalation of COVID-19, the government in Sweden introduced new rules such as the one that stores, and indoor facilities must calculate the amount of people that are allowed inside depending on the size of the area. Also, there is the policy of no more than 8 people allowed at public events (Krisinformation, 2021a).

While many stores and businesses were open, the Swedish population started to spend less time and money in retail stores during this period. In contrast, the population increased its expenditure in grocery stores (Hellstrand and Melnyk, 2020). During the COVID-19 pandemic, grocery stores adopted several measures such as limiting the number of people allowed in the store at the same time, putting up signs with the information about keeping distance, putting up plexiglass, providing protective equipment to protect their workers, and providing hand sanitizer for customers (Svensk Handel, 2021). Some stores even extended their opening hours by one hour, exclusively for their customers that are in the risk groups (Berthelson, 2020; Söderqvist, 2020).

1.2.2 Jönköping University (JU) students

The city of Jönköping is a university town with Jönköping University being the only university with over 19 000 registered students, both local and international, between the years 2020 and 2021. Normally, the university mainly offers on-campus teaching together with many student associations and activities for students to enrich their student life. During these events students have the opportunity to socialize with other students and apply to different student associations (Jönköping University, 2021a). However, the situation of COVID-19 resulted in JU adopting some measures to follow the guidelines of the government. The students who needed to continue their studies on campus were allowed to have physical classes on campus. Whereas some classes were divided into smaller groups where half of the group stayed in-class and the other half attended lectures online. Although, this was only required in the first semester, August till December 2020. As the spread of the virus escalated, the university decided to switch to online lectures as much as possible and students were encouraged to study from home, although this varied between different regions within the country (Jönköping University, 2021b; Krisinformation, 2021b). Not only were

9 the students' education affected, but their social life seemed to take a step back as well since all student associations at the university stopped all their activities and cancelled all their planned events (Jönköping University, 2021c).

Furthermore, young adults, namely university students, went through changes both mentally and physically when they moved away from the comfort of their hometowns and parents and started to live by themselves where they have to make decisions on their own. This is also a crucial part of their life in which they form their outlook on their life and the world around them. During this time in their life, they might make poor decisions as their understanding of the society and themselves has not yet matured. When faced with a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, their life was disrupted, and their actions and emotions will be affected creating a shift in their behavior and opinions in their student life (Wan et al., 2020).

With the backdrop of the pandemic and the difficulties faced by these university students and how they responded to the pandemic makes it an interesting group to research. They are in a crucial stage of their life, when they are experiencing many new and unexpected situations. The authors of this thesis have gained firsthand experience by being university students at JU and living in Jönköping during the pandemic. The research could be of interest for governmental institutions to understand how students responded to COVID-19 related regulations and recommendations issued by the government, and how these measures have impacted students or changed their behavior within the pandemic. The findings could be helpful for government agencies in the future to make decisions on how to communicate new regulations to the public. This could also be of interest for businesses operating in the retailing sector to understand how students perceive and respond to measurements adopted by grocery stores. Also, this study may offer insights about the shopping behavior of a particular customer segment for grocery retailers to plan and offer better services in the future.

1.2 Problem Discussion

It is evident that the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted both individuals in their everyday life, as well as companies on a larger scale (Grashius, 2020; Kirk and Rifkin, 2020; Sheth, 2020). There has been a change in the way people consume and it is discussed that while consumption is habitual it is also dependent on the context, which can be social contexts, development of new technology, changes of rules and regulations, and lastly less predictable situations of natural disasters such as earthquakes, wars, and global pandemics (Sheth, 2020). Kirk and Rifkin (2020) argue that the consumer journey during a pandemic is initiated by consumers realizing the potential for a pandemic and react to this by trying to control the situation and defend themselves against any possible threats. Although, with time, consumers start coping with the situation they are going through, by trying to adapt new behavior to gain control of the situation. In the field of consumers’ shopping behavior in times of crisis where the fear of being unprepared is present, Kirk and Rifkin (2020) further discuss that people engage in hoarding behavior, which is where products are

10 purchased in bulk, to feel a sense of preparedness. In such circumstances, essential products such as toilet paper, cleaning supplies, and food are commonly bought. Moreover, when people revert to bulk buying, the freedom to purchase essential products is reduced due to the limited on-shelf availability, and the scarcity of those products has been identified as a driver to such behavior (Gupta and Gentry, 2019). A sign of hoarding behavior could be seen during the first wave of the pandemic as various products ran out of stock quickly or were not available (Liu, 2020). According to Grashuis (2020) and Hellstrand and Melnyk (2020) there has been a rise in the expenditure on groceries, where grocery shopping has been recognized as one of the most important practices of consumers, as it is one of the most essential physiological needs (Lamb et al., 2017). Thus, the food industry has been identified as the second most affected industry because of the pandemic (Nicola et al., 2020).

While consumer behavior during a pandemic has been researched, not much attention has been given to the practice aspect of how consumers’ carry out the doings in grocery shopping during the COVID-19 pandemic. The focus has been on the aspect of panic buying (buying in bulk), also known as ‘hoarding behavior’, and scarcity during crisis situations and how it applies to the COVID-19 pandemic (Kirk and Rifkin, 2020). Additionally, Kirk and Rifkin (2020) and Sheth (2020) explain that during such times of uncertainty people have started to rethink what is important. This can be seen in stores during the COVID-19 pandemic, where there was a short supply of various products such as toilet paper, dry pasta, and canned food. Moreover, consumers' interest towards purchasing products related to well-being, safety, virus prevention, and pantry preparation, has increased (Anatasiadou et al., 2020). Looking at the signs of hoarding behavior and changes in consumer behavior makes it important to understand how consumers' grocery shopping practices might have changed during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, it is necessary to gain a deeper understanding of how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted on consumer practices and habits related to grocery shopping. Additionally, Sweden's different approach to the pandemic makes it necessary to study a Swedish context.

1.4 Purpose and Research Questions

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed consumers’ everyday life, especially their grocery shopping practices, due to the measures taken by governments and retailers to minimize the spread of the virus. University students are a special consumer group as they are in a crucial stage in their life with new experiences in a changing environment. Therefore, the aim of this research is to understand how grocery shopping practices of students at JU have changed as a result of the pandemic. This study asks this research question:

RQ1: How have grocery shopping practices of university students in Jönköping changed because of the COVID-19 pandemic?

11

2. Literature review

_____________________________________________________________________

This chapter presents background to the research topic and explains the theory to be used in this research. This section starts with giving an overview to the topic of consumer behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic, then the concept of practice theory is presented together with an explanation of the theory applied in this thesis.

_____________________________________________________________________

2.1 Consumer behavior during COVID-19

Consumer behavior can be described as “the study of how people or organizations behave when obtaining, using, and disposing of products and services’’ (Kumra, 2007, p.2). While behavior can be formed on an individual level or in a group, consumer behavior also involves the use of products and the decision making process of purchasing products. Behavior is bound to location and time and can change due to uncertainty or unexpected changes (Kumra, 2007). Salomon (2013, p.2) describes consumer behavior as “Consumers play several roles in the process of selecting, buying, and using goods, services and experiences.”.

From the two definitions it can be concluded that consumer behavior mostly revolves around the decision-making process of products, goods and services. Additionally, this also includes the considerations of consumers, regarding prepurchase, purchase and the post purchase process. The pre purchase process includes what the consumers think are the best choices and if there are any alternatives options. During this stage, the consumer needs to know if the product they are purchasing will be a stressful experience for them and what it will say about them. In this stage the consumers want to know how the products work and what the advantages are. The purchase depends on the situation, store, and time constraints and whether the consumer is satisfied with the product or service is part of the post purchase stage (Solomon, 2009).

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the everyday life of consumers and has changed the way how people behave. Sheth (2020) discussed several behaviors that have changed due to COVID-19. The first one is hoarding behavior, this behavior is affected because people start to panic and start to stockpile on products, which creates shortages of products. The scarcity of products leads to consumers changing their choices and looking for alternatives (Eger et al., 2021). Most products that are stockpiled are toilet paper, meat, bread, water and disinfecting and cleaning products. In situations when people start to feel uncertain, people will start to stockpile on these products. It can be identified that these consumers are mostly driven by fear in uncertain situations. A second behavior that is affected because of COVID-19 is improvisation, in situations where consumers are constrained, they start to improvise to pass the time. Radjou et al., (2012), describes this as developing solutions in times of constraints, with doing more with less.

12 During COVID-19 more people started to spend more online, for example by using Zoom for classes, work, and or other public events. Another behavior that changes can be seen in, is that consumers start to postpone buying or using services and products such as automobiles, bars, sports or going to restaurants. This behavior is called pent-up demand, although not much research has been done upon this type of behavior of consumers since most research has only been done to analyze the economy. In addition to this, another important change in consumers behavior is that consumers have started to embrace digital technology, especially Zoom and social media, which has become a part of their everyday life. While people become more constrained to their homes and spend more time online, whether it is for work or education purposes or consumption, it can be said that “the stores come to their home”. As it is more likely that consumers, due to spending more time online, make their purchases online rather than in a physical store. Consequently, this affects the impulse buying of consumers and the planned vs unplanned consumption (Sheth, 2020). However, due to people having to work and study from their home a blurring of work-life boundaries has been created. In which consumers find it difficult to create a boundary between their work and personal life, due to the limited number of resources and space. Additionally, since consumers had to stay at home and avoid contact with others, they were limited to meeting with friends and family. This resulted in a switch to keeping in contact through social media or Zoom, which according to Sheth (2020), a significant change is to be expected due to the adoption of new technologies.

The pandemic has also changed the behavior of how consumers spend their money. Especially for millennials, according to a research of Pastore (2020) conducted in the United States, millennials were the first to stock up on essential items in fear of the COVID-19 virus. Furthermore, the research also concludes that consumers started to spend less on clothes and luxury items and instead started to spend more on comfort food and other items as they spend more time at home. When stores began to open their doors again, 54% of consumers said they felt safe again to visit grocery stores and shopping malls. As can be seen, fear of getting infected is an important factor for these consumers.

In addition, a study of Ellison et al. (2020), researched food purchasing behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study shows that households involved themselves more in stockpiling behavior and before going to the grocery store, they were more likely to check their fridge and freezer to not forget any items. Since, they preferred to visit the grocery store less times per week. It is also important to remember that the routine of weekly grocery shopping is considered a low involvement activity. In which the consumers are used to buying the same food products, creating a weekly shopping routine (Beharell and Denison, 1995). Additionally, it is found that dietary habits are changed when there is an increased sense of risk. However, the moderation of reacting to the risk is also dependent on the characteristics of the person (Hoon ang et al, 2001). The behavior of consumers might shift to a more pessimistic outlook for the future, this has an effect

13 that people will spend less and save more. It is expected that consumer behavior will change after the pandemic, therefore, it is important to understand how consumer behavior affects people in all aspects of everyday life (Borsellino et al., 2020).

2.2 Consumer grocery shopping behavior

When it comes to grocery shopping, the choices consumers make when visiting stores involve notions of taste and are complex socially constructed. However, considering grocery shopping, consumers can easily choose and switch from brands (Elms et al., 2016). Additionally, for consumers to remember and process all the name brands, offerings, retailer names and reviews is a large overload of information to be processed. Nevertheless, engaging with new technology provides the feeling that it will solve a problem to cope with contemporary lifestyles and even household issues that may arise (De Kervenoael et al., 2014). In a consumption society, grocery shopping can indicate an individual's lifestyle and taste. The earlier phase of pre-made purchase is named the front-loading practice, this type involves ‘scripted behaviors’ (Erasmus et al., 2002). This ‘scripted behavior’ can involve making a list or planning meals ahead, and such practices may lead to a greater systematic process (De Kervenoael et al., 2014).

Nevertheless, the grocery shopping behavior and choices of consumers change during a pandemic. Sheth (2020) discusses that while consumption is habitual it is at the same time dependent on the context, and that over time consumers change or develop their habits. There are four key contexts that impact consumption. The first one is social context, which refers to aspects such as family, friends, marriage and moving to another city. The second context is the development of new technology that has the power to change old habits and the way we consume. While the third context is concerned with rules and regulations in public places, such as areas in which smoking is not allowed. Lastly, the fourth context refers to less predictable situations of natural disasters, for example conflicts and wars, hurricanes, earthquakes, or global pandemics. In this case, the fourth context of less predictable situations is highly relevant as this thesis tries to understand the changes in consumers grocery shopping behavior due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

There are several purchasing behaviors that have been shaped and affected during an outbreak of a virus. In the study of Anastasiadou et al., (2020), they describe different types of behavior that emerge during a pandemic. The first type is emergency purchasing behavior, this type of behavior is affected by an emergency where society is provoked with fear, which increases the desire to ease the fear. Due to the provoked fear, the behavior of society changes as fear arises and this is supported by messages and a strong connection that brings a source of relief. According to Tormala (2016), psychological certainty plays an important role in influencing the thinking, attitudes, and behaviors of an individual. Another behavior described by the authors is the stockpiling behavior which is influenced by sudden demand shifts. When there is a sudden shift in supply or demand the behavior of consumers leads to panic buying. In addition, when consumers want to regain control over a situation, they will manage their emotional states with “retail therapy” and this leads

14 to stockpiling. A study of Helsen and Schmittlein (1992), indicated that consumers are more likely to stockpile a product that is on offer, since consumers have a sense that there is lower availability of products that are on offer. This was also discussed by Kirk and Rifkin (2020) who explained that in times of crisis, where the fear of being unprepared is present, people revert to bulk buying as a part of hoarding behavior. This has been identified as a result of scarcity, where the lack of on-shelf availability of products creates a fear in consumers and drives them to purchase those products before they are sold out.

During a pandemic, product purchases and preferences change. For example, normally consumers are more likely to consume fruit over beer, however, if the consumer is aware that they will have to stay home for a longer period of time, the consumer is more likely to consume beer and snacks. Furthermore, as mentioned before, a shift in behavior is that consumers are more likely to hoard products that are lower in price or if consumers are more uncertain if the product will be available for a longer period of time. During the outbreak of the MERS virus, there was a significant increase in grocery shopping expenditure. A change can be seen with Spanish consumers during the COVID-19 outbreak was that alcohol and hygiene products were purchased more frequently. In Italy, long shelf-life products were more purchased such as, rice, flour, pasta. However, during the first outbreak of the COVD-19 pandemic, that started in January 2020, there was also an unexpected increase of consumers purchasing products such as oat milk. Contrastingly, in Sweden where no lockdown was imposed, consumers still stockpiled on food products during the first four weeks of the outbreak of the pandemic. This was due to the Swedish people having an overload of information from their governmental websites and the fear of the COVID-19 virus. Furthermore, consumers were more likely to have quicker visits to the store and disinfecting of the products became an important concern for them (Anatasiadou et al., 2020).

Moreover, a study performed by Anatasiadou et al. (2020) has identified six different types of threshold levels of consumer grocery shopping behavior during the coronavirus outbreak. First, there was a shift in consumers' proactive health-minded buying, indicating that these consumers increased their interest with products that endorse overall safety and well-being. Secondly, there was an increase in products for virus prevention, such as face masks and hygienic products. Thirdly, there was an increase of pantry preparation, this resulted in people making more visits to the grocery stores. Fourthly, with people being quarantined in their homes there has been an increase of online shopping. Fifthly, there was an insufficient supply of goods as visits to stores were constrained. Lastly, there is a structural change in the supply chain and patterns of hygiene. However, the model developed by Arsel and Bean (2013) provides meanings to the objects and doings of the consumers when visiting the grocery store. According to Elms et al., (2016), the practices of consumers involve preference of brands and stores. Their choices of stores mainly depend on how they want to fulfill their needs and the choices they make in the grocery store may have many different meanings and interpretations behind them. Additionally, theories of practice can also give an understanding behind the behavior of consumers. All in all, a pandemic has an

15 impact on the grocery shopping behavior of consumers, in which the fear of a virus increases stockpiling behavior and an increase in purchasing of hygienic products.

2.3 Practice theory

In the context of consumer research, ‘practice’ has been used in two ways, and to understand practice theory it is important to understand how the term ‘practice’ is used. Some studies use the word practice as a covering term for actions performed by an individual, which has been adopted by scholars such as Humphreys (2010) and Thompson and Arsel (2011). Whereas theorists of practice theory discuss that practice should be understood by analyzing “ongoing routines, engagements, and performances that constitute social life.” (Arsel and Bean, 2013, p. 901). Reckwitz (2002), as cited by Warde (2005, p. 249), explains that there is a difference between practice and practices, and describes them as followed:

“Practice (Praxis) in the singular represents merely an emphatic term to describe the whole of human action (in contrast to ‘theory’ and mere thinking). ‘Practices’ in the sense of the theory of social practices, however, is something else. A ‘practice’ (Praktik) is a routinised type of behaviour which consists of several elements, interconnected to one another: forms of bodily activities, forms of mental activities, ‘things’ and their use, a background knowledge in the form of understanding, know-how, states of emotion and motivational knowledge”.

Furthermore, another way to understand practice, as has been discussed and highlighted by various scholars, is the emphasis of understanding the unbreakable link and synergy between the ideas, materials that are used, and how something is done. Although, while the understanding behind it remains similar, different names, or labels, have been used for the triad, or circuit, of practices, such as understandings, procedures, and engagements (Warde, 2005) and objects, doings, and meanings (Magaudda, 2011). Thus, the practice theoretical approach perceives consumers as people who are tied by a linking between social and cultural factors, rather than perceiving them as purely structure dependent or rational (Arsel and Bean, 2013). Furthermore, Schatzki (1996), makes a contrast between two separate types of practices, dispersed practices, and integrated practices. In which, integrated practices are involved with a combination of several complex actions. Whereas dispersed practices refers to a practice that is not related to a specific type of action, rather it can be applied to other social contexts. Furthermore, according to Schatzki (1996), the doings that form a practice are linked through three stages, which are described as through understandings, through rules and instructions, and through ‘teleoaffective structure’. The ‘teleoaffective’ structure involves moods, emotions, purposes, and beliefs of a person. Furthermore, the ‘teleoaffective’ structure is also explained by Nicoloni (2012), in which it refers to the purpose behind performing the doing or using the objects, this structure guides a connection between objects, doings and meanings. It also refers to that all practices evolve based on a specific direction.

16

Practice theory is a collection, or family, of theories that aim to understand and describe the cultural and social world by examining practices performed by individuals by considering complex practices which take place in people's social life. The concept emerged in the late 1970’s stemming from various works of theorists and classical philosophers and sociologists, throughout history, such as Clifford Geertz’s work on symbolic anthropology, Karl Marx’s work on how social class and culture impact individual’s practices, and to some extent Claude Lévi-Strauss regarding structuralism (Ortner, 2006). Such philosophers laid the foundation to the concept of practice theory on which other theorists continued to explore and build upon, to better understand the concept. Regarding which two groups, or rather generations, of theorists can be seen. The first generation is the one that laid the foundation to practice theory such as theorists Bourdieu (1977) and Giddens (1984). Bourdieu (1977) argued that culture does not stem from free will but is formed by social actors. Furthermore, Habitus was introduced by Bourdieu as a way to better understand the fundamental rules of social behavior and explained it as the embodiment of socially rooted habits, skills and knowledge. Additionally, he introduced three forms of capital that constitutes habitus and decides an individual's social position, namely economic, social, and cultural capital. These capitals ultimately shape the way an individual acts. On the contrary Giddens (1984) argues that routinized behavior in the long-term can also shape practical knowledge. As it becomes a part of the practical consciousness of people on a long-term basis. Cleaning is an example of this, as the action dominates daily modes. While the second generation consists of theorists that extend and build upon the work of previous theorists by adopting different perspective and researching in different contexts, or disciplines, such as organizations, taste, and consumption (Warde 2005; Holt, 1995; Arsel and Bean, 2013; Reckwitz, 2002; Schatzki, 2005). The perspective of theorists involved within the field of studying consumption focus less on the individual undertaking the practice, rather they focus on the practices that are essential to social order and further highlight the routinized facets of life (Gronow and Warde, 2001).

2.3.1 Consumption and practice

Consumption, according to Schatzki (2005), is rooted in our everyday life and is an ongoing happening that starts from the moment we wake up and lasts until we go to sleep. While this is one way of understanding consumption, there seems to be no agreement between theorists when it comes to defining the concept (Wilk, 2002; Warde, 2005; Holt, 1995). Although, there are two main perspectives adopted by scholars within the realms of studying consumption. One perspective comes from Holts' (1995, p.14) study of categorizing consumption, where consumption is defined as “Consuming is a mode of action in which people make use of consumption objects in a variety of ways.” and refers to the act of consuming as ‘consumption practice’. Furthermore, he argues that consumption is the dominant factor which consists of practices and sub-practices. In his study, Holt (1995) developed a typology where he discussed the following four metaphors in relation to a baseball game: (1) Consuming as experience consists of accounting, evaluation, and appreciating, and it insinuates the consumers emotional response to the objects. Accounting includes the ability

17 to understand the game and rules, with the help of which the consumer can express good judgement, and this is when evaluating takes place. When a consumer can fully understand the game and can connect with it emotionally, that is when appreciating takes place; (2) Consuming as integration, refers to the symbolic connection the consumer feels towards the practice. This metaphor includes assimilating, producing, and personalizing. These three explain how consumers integrate with the practice in such a way that their way of thinking becomes natural and that they are able to contribute to the practice through their actions. This can happen when consumers wear club colors during the game which gives them “us-feeling”; (3) Consuming as play, refers to the interaction between consumers and the sharing of experiences. There are two ways that this can happen, either on an interpersonal level which, is referred to as communing, or through socializing where consumers entertain others by using their experience with the object; (4) Consuming as classification, includes the integration and differentiation of consumers through objects they own (“classifying through objects”) or by their actions (“classifying through actions”). Additionally, Holt (1995) has a similar approach as practice, as he considers concepts such as accounting, assimilating, evaluating, appreciating, and producing as an explanation for how consumers consume, or rather, practice consumption. Whereas Warde (2005), Arsel and Bean (2013), and Schatzki (1996) have a different understanding for consumption where it is argued that practice is the dominant factor which entails smallest consumptive moments, so it is practice that brings out consumption. The author describes it as “a process whereby agents engage in appropriation and appreciation, whether for utilitarian, expressive, or contemplative purposes, of goods, services, performances, information about ambience, whether purchased or not, over which the agent has some degree of discretion’’ (Warde, 2005, p.137).

To conduct an analysis within the realms of practice theory it is important to establish which form of understanding this thesis will adopt due to the different approaches and perspectives presented by theorists. As this thesis seeks to identify changes in consumers grocery shopping practices, by understanding the underlying meanings behind the usage of certain objects and performance of doings, this thesis adopts the perspective of understanding practice theory based on the definition of Arsel and Bean (2013) where practice is seen as the dominant factor consisting of smaller consumptive moments and the focus is on considering social constructs rather than on the individual. To get an insight to the fundamental meanings related to the practice of grocery shopping, this thesis will adopt the practice circuit of objects, doings, and meanings of Arsel and Bean (2013) which the authors of this thesis have identified categories that describe the most essential meanings based on the data. Furthermore, the authors in this thesis adopt the understanding of meaning as a ‘teleoaffective structure’ as per the explanation provided earlier in this chapter.

2.3.2 The practice circuit of Arsel and Bean (2013)

Arsel and Bean (2013), in their research regarding how taste regimes orchestrate practices, developed a framework (see figure 1) in which they explore the link between objects, doings, and

18 meanings through the circuit of practice. The authors adopted the terms objects, doings, and meanings, from the practice circuit presented by Magaudda (2011) and then identified three practices that explain the link between the triad. The authors derived the findings from a quantitative content analysis from different blogs, including in this was also a quantitative narrative analysis where the authors read blogs daily. Furthermore, the findings were also derived from 12 long interviews and participant observations. In their research Arsel and Bean (2013) have adopted the following understanding of the concepts: Objects are referred to as, not only the physical objects, but it could also be something abstract, such as an idea or brand. The object in this case does not offer much taste on its own and exists in a “network of materiality” that helps to establish the formation of the practice. In their study the authors provide an example of a dressing table (object) being found in a store (network). Whereas doings are referred to as the “bodily activities or embodied competences and activities” performed by an individual with the objects, such as finding, discovering something, or making use of items. While meanings are referred to as what the network of objects signify when put together with the doings, (Arsel and Bean, 2013, p.905). Furthermore, Arsel and Bean (2013) identified three practices, problematization, ritualization, and instrumentalization, which manage consumption and connect the objects, doings, and meanings. Whereas problematization is the connection between the meanings and objects, and this is where the reason behind one’s action is continuously questioned. Moreover, the authors adopt the same definition as Thompson and Hirschman (1995) further explain this term “to indicate how deviations from normative and cultural standards, such as physical appearance or gendered behavior, become coded as problematic.” (Arsel and Bean, 2013, p. 907). Ritualization refers to establishing a set of symbolic and expressive activities that are built on multiple behaviors that happen in an unchanging and particular order, that for the most part is recurrent over time. Rituals impact the way in which individuals acquire objects and what they do with them, and how these objects bring value and meaning to the individual. Lastly, instrumentalization refers to the process of linking objects and doings to actualize meanings (Arsel and Bean, 2013).

19 Figure 1: An illustrated example of how taste regimes regulate practice (Arsel and Bean, 2013, p.910).

20

3. Methodology

_____________________________________________________________________

This chapter discusses the methodology of this research. The chapter starts with discussing the research philosophy, research approach, and research strategy. Thereafter, aspects of the data collection process, data analysis, research quality and some ethical considerations are discussed. _____________________________________________________________________

3.1 Research Philosophy

As the aim of this research is to understand the social world by looking at consumer practices and how they may have changed as the result of a pandemic by interviewing a smaller sample, this thesis adopts interpretivism. According to Saunders et al. (2016) interpretivism is common for qualitative research where the objective is to create a deeper and richer understanding of the social world and context, which are often achieved by looking at smaller samples. To get a deeper and richer understanding of the informants' practices, the meaning behind using certain objects and performing certain actions will be looked at.

3.2 Research Approach

This thesis combines two different research approaches, namely the deductive approach and inductive approach. Firstly, the deductive approach starts with an existing theory, which is then tested with the collected data. In this case, this is adopted when applying Arsel and Beans (2013) practice circuit of objects, doings, and meanings. Whereas the inductive approach is adopted start by collecting data relevant to the topic and thereafter, the researcher will look for patterns in the collected data, to develop a new theory (Sekaran and Bougie, 2010). As the goal was to identify changes in grocery shopping practices of university students during the periods of pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19, common themes regarding the informants’ actions and choices have been identified from the transcripts of the interviews, based on which categories of meanings were formed to better understand the reasoning behind the choices during the two periods and to identify possible changes.

3.3 Research Strategy

The aim of this research was to understand how students' grocery shopping practices may have changed because of the COVID-19 pandemic, by looking at the underlying meanings of certain doings and the use of certain objects. Therefore, this research incorporated a qualitative research method, where the data was collected through semi-structured interviews. According to Saunders et al. (2016) qualitative research is conducted with the objective to understand or get an in-depth insight towards an issue, which is commonly done through collecting non-numerical data through different methods such as interviews and focus groups.

21

3.4 Data collection

3.4.1 Semi-structured interviews

With the aim of understanding how grocery shopping practices changed for students due to COVID-19, conducting interviews was considered the most appropriate method to achieve this. Interviews can be divided into the following three categories: structured interviews, semi-structured interviews, and unsemi-structured or in-depth interviews (Saunders et al., 2016). Since the goal with these interviews was to get an insight to each student's grocery shopping practices and their perspective of how the governmental restrictions have impacted their process, semi-structured interviews were considered the most suitable method to achieve this (Collis and Hussey, 2014; Saunders et al, 2016). Thus, when conducting the interview guide a set of standardized questions were formed, to stay within the areas of the topic. These questions were combined with open-ended questions to give the informant an opportunity to discuss more openly regarding their experience related to the research topic, and allowed the researcher to ask follow-up questions. Furthermore, this allowed the informants to discuss their thoughts freely and without influence from others. In order to follow the restrictions and recommendations given by the Swedish government, the interviews were conducted via Zoom or FaceTime. In total 15 semi-structured interviews were conducted which lasted between 40-60 minutes. The reason for incorporating video calls instead of only using voice call for the interviews is because it allows the interviewer to read the informant's body language and have a more accurate understanding of the meaning of the responses. Additionally, all interviews were conducted in both English and Swedish, where the informants had the opportunity to choose the language, they would prefer to do the interview in. The interviews that were conducted in Swedish were translated by the authors, and to prove the accuracy of the translation all content was confirmed by the informants to ensure that the translation represents the informant’s opinion fairly.

3.4.2 Design of the interview guide

The design of the interview guide was made to fit the practice circuit of objects, doings, and meanings, by Arsel and Bean (2013) that is applied in this thesis. The questions were divided into three sections and designed to look at the objects, doings, and meanings in the practice circuit (Arsel and Bean, 2013; Warde, 2005) to better understand the informants' grocery shopping practices during the two periods. When constructing the interview guide the authors researched how scholars within the field of consumption practices have framed their research, to see whether the design had provided the awaited result. Additionally, a test interview was conducted to see if the developed questions would provide the necessary information required to answer the research question of the thesis. After ensuring that the interview guide would allow the researchers to collect the necessary information for this thesis, the interviews were conducted.

22 3.4.3 Population and Sampling

As the aim is to get an insight to how university students in Jönköping practice grocery shopping, this study implements the convenience sampling method as it allows the researchers to use existing contacts to gather the necessary data. Convenience sampling is a type of sampling method in which interviewees are chosen simply because it is an ‘convenient’ source for the researcher (Sekaran and Bougie, 2010). The reason behind this is because the authors of the study live and study in Jönköping, meaning they have easy access to contact other university students. The informants were chosen based on the characteristics if they are/were conducting university studies during the time of the pandemic and that they lived in Jönköping during this time. However, in order to minimize the risk of bias, the informants were made aware of the subject prior to the interview and were also given an information sheet (see appendix 1) with all the necessary information. Furthermore, the informants were only chosen based on their willingness to participate and that they fulfill the criteria of being a student in Jönköping during the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, complete anonymity was given to decrease the level of bias. In addition, both international and local students were interviewed for this study. By including informants from various cultural backgrounds, it allowed the authors to understand the subject from different perspectives which was interesting as Sweden had a different approach to the situation, compared to other countries.

In the table presented below, the informants together with relevant characteristics of nationality, current living situation, age, gender, and major, as well as duration, language in which the interview is conducted in, and time of interviews are summarized.

Table 1: Table of Informants

Informant Nationality

Current living situation

Age Gender Major Duration, time and language of interview 1 Spanish With a roommate 23 Female MSc, Interventions in Childhood 50 min, 20th of April, 16:00, English 2 German with a roommate 24 Female MSc, International Marketing 55 min, 16th of March, 17:05, English 3 German with a roommate 23 Female MSc, International Marketing 46 min, 16th of March, 19:10,

23 English

4 Swedish lives alone 24 Female BA,

International Management 51 min, 18th of March 18:30, Swedish 5 Swedish lives alone 23 Female BA,

Biomedical Analyst 46 min, 19th of March, 17:30, Swedish

6 Dutch lives with

roommates 22 Female MSc, International Marketing 47 min, 18th of March, 13:30, English 7 Dutch with roommates 25 Female MSc, International Marketing 49 min, 19th of March, 15:00, English 8 Romanian with roommates 23 Female MSc, Interventions in Childhood 54 min, 3rd of April, 13:00, English 9 Romanian with roommates 24 Male BA, Psychology 50 min, 2nd of April, 13:00, English 10 Greek lives alone 25 Female MSc,

Interventions in Childhood 42 min, 2nd of April, 15:30, English 11 Spanish with roommates 26 Female MSc, Interventions in Childhood 59 min, 2nd of April, 17:00, English 12 Swedish lives alone 24 Female BA,

Human Resources 41 min, 20th of March, 16:45 Swedish 13 Swedish lives with

family 24 Female MSc, Civilekonom 40 min, 18th of March, 19:30, Swedish

14 Dutch lives with

roommate 23 Female MSc, International Marketing 44 min, 17th of March, 13:35, English 15 Swedish lives alone 24 Female MSc,

International Marketing

45 min, 17th of March, 12:15,

24 English

3.5 Data Analysis

In order to analyze the data, coding will be a beneficial advantage for this research, to reduce the collected data into segments with assigned categories. Coding will allow the researchers to see patterns from the interview transcripts which will help to analyze the data and identify the categories of meanings. However, before coding, the authors immersed themselves with the collected data to become familiar with it (Belk et al., 2013). For this thesis, the thematic coding approach was used to perform the analysis and interpretation of the data. This type of coding can be used to analyze a small sample of qualitative data, and this allows to provide a description and explanation of empirical findings through the lens of theories (Saunders et al., 2016). Firstly, the audios of all interviews were transcribed. Thereafter, the two authors separately read the transcripts to come up with initial themes and codes. Then, the two researchers exchanged findings and discussed further to reach agreements on common themes, upon which 8 categories of meanings were identified.

3.6 Research Quality

3.6.1 Credibility

Credibility refers to the truth of the findings and this allows the researchers to interpret and present the data collected in a truthful way (Collis and Hussey, 2014). A technique that is applied for this thesis is triangulation, meaning that more than one person will analyze the data (Lincoln and Guba, 1985). In this case, both authors will analyze the data separately in order to minimize the risk of involvement of personal values and or beliefs when the research results are presented. The process, as previously mentioned, consisted of the authors immersing themselves with the data and then coming together to share the findings and analyze the data.

3.6.2 Transferability

Transferability is the degree to which the findings from the research can be applied in different contexts to allow generalization (Collis and Hussey, 2014). A clear description of the research process and context is provided which will allow other researchers who want to use the data for their study in another context (Lincoln and Guba, 1985). Therefore, a detailed description of various aspects of the research process, including the research context, of this thesis is provided to the reader.

3.6.3 Dependability

Dependability refers to the extent to which the research could be replicated by other researchers and conclude similar results, with the information that is provided in a research (Collis and Hussey, 2014). To ensure dependability a thorough description of the entire research process and the steps taken when making decisions and conducting the research is provided.

25 3.6.4 Confirmability

Confirmability refers to the degree of neutrality the findings are presented in, such as signs of bias or personal motivation from the authors. Confirmability can be attained when credibility, transferability and dependability are established (Collis and Hussey 2014; Lincoln and Guba, 1985). In order to ensure confirmability in this study all above mentioned aspects have been considered as described previously, such as incorporating analyst triangulation to avoid bias.

3.6.5 Ethical Considerations

When conducting qualitative research, it is important to consider ethical considerations such as anonymity, informed consent and confidentiality. Prior to the interviews an information sheet (see appendix 2) containing relevant information about the research was distributed to the informants. As discussed by Sekaran and Bougie (2010), before the interview, informants were asked to sign a consent form, which states their rights and that the informants accepts to participate in the research. All the names of the participants are kept private to protect their privacy. However, since the interviews were conducted online the informants were asked to confirm their acceptance of the terms stated in the consent form during the recording. In the information sheet and consent form the ability for the informant to withdraw their participation in the study at any given point was discussed together with the assurance of complete anonymity and confidentiality. Moreover, it is also stated that the interview will be recorded and that once the research is completed the voice recording will be destroyed. Furthermore, it was also mentioned that only the researchers would have access to the recordings during the process of conducting this study.

26

4. Findings and Analysis

___________________________________________________________________

In this chapter the findings and analysis of the research are presented. The chapter is divided into three sections based on the framework of Arsel and Bean (2013) that includes objects, doings, and meanings. Each section includes the practices pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19. The two periods are compared, and a table is provided with the changed practices. Based on the finding’s categories have been identified to be able to form the meanings to the objects and doings.

______________________________________________________________________________

The framework by Arsel and Bean (2013) of objects, doings, and meanings, will be used in order to elaborate on the findings of the research. As the objection of the study is to compare the practices of the students before and during the pandemic, the findings will be divided up into two sections and then compared. Thereafter, categories that have been identified through the collected data will be presented and discussed.

4.1 Objects

4.1.1 Objects pre-COVID-19

When it comes to objects used by the informants before the outbreak of COVID-19 all informants used reusable bags, mobile phones and shopping carts or baskets. However, regarding the use of self-checkout counters all informants discussed that it depends on the situation, such as if the store is busy, the length of the queue and if they are in a hurry.

“I try to bring a shopping bag from home when I go shopping so that I don’t have to spend money on buying a bag each time I want to buy some groceries. I try to keep one with me for example when I go to the University in case I want to do the grocery shopping on my way home.”

- Informant 4 “I just pick the fastest one, since I will also see what is the fastest queue depending how fast it is moving. But if the one I am in line for is moving slower than another open check out, then I would switch to the one that's progressing the fastest. I don’t wanna waste time standing in a queue.”

- Informant 5 “I have a habit of writing down a shopping list on my phone before I leave my apartment to do grocery shopping. So, I use my phone to remember what to buy, so that I won't forget anything important and have to go back to the store. That would be a waste of time.” and “I always have canvas bags with me from home and I always bring these nets to put the

27 vegetables in so I don’t have to use the plastic bags. I do this more for sustainability reasons.’’

- Informant 7 “It depended on the store, some of the smaller stores that I visited only had normal checkouts. But if a store had both options I would just pick the one that had a shorter queue, to be done as fast as possible.”

- Informant 12 “I have several reusable bags at home that I like to use when I go to any store because then I can save money, because in most of the stores you have to pay extra for the bag. It might not be that much at the time, but it adds up if you buy a new one all the time and also what am I going to do with all of these bags? They just end up in the trash anyway. So this way I can save money and also be nice to the environment.”

- Informant 15 Although, when it comes to gloves, masks, and hand sanitizer, none of the informants used gloves or masks. While informants 4, 12 and 15 mentioned that they keep a bottle of hand sanitizer in their bags for hygiene reasons.

“I usually keep a small bottle of hand sanitizer in my bag so that I can use it any time I want and feel the need to sanitize my hands. So yes, even before covid I was always cleaning my hands with hand sanitizer, I find it weird that it was not used by more people before covid.”

- Informant 4 “I keep hand sanitizer with me so that I can sanitize my hands at any time and I’m also used to keeping it with me, so it’s just like a reflex to grab the bottle or check in my pockets so that I have it with me before leaving the house.”

- Informant 12 “I always keep a bottle of hand sanitizer with me because then I can sanitize my hands anywhere when I’m outside and don’t have access to soap and water. But I also think it's a habit because my mom always used to keep one in her bag so that's probably also a reason.”

- Informant 15 By taking looking at the quotes presented above, it can be concluded that the informants, pre-COVID-19, made use of the objects for a faster grocery shopping process and bringing their own reusable bag for sustainability reasons. It can also be seen that the informants used objects out of

28 habit, as it was discussed during the interviews that certain objects were used naturally without giving it much thought.

4.1.2 Objects during COVID-19

When it comes to objects used by the informants during the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, all informants use hand sanitizers, while informants 1, 4, 11, 12, 13 and 15 mentioned that they keep a bottle of hand sanitizer in their bags. Whereas, informants, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 14 use the hand sanitizers provided in the stores. Moreover, all informants use reusable bags and mobile phones when grocery shopping. However, when it comes to using shopping carts or baskets informants 7, 11 and 12 try to avoid using those when grocery shopping, while the rest of the informants use those objects. None of the informants uses gloves or masks when grocery shopping, except for informant 11 who uses a face mask before entering the grocery store.

“I only use the hand sanitizer that is in the store, because I usually forget to bring my own since I’m not used to keeping it with me. I have started to using it more now actually, because I want to protect myself from getting sick from the virus”

- Informant 5 “I mean I use the face mask now because I don’t want to get any infection but before corona I was never worried about any virus taking over this world, I prefer to wear it since in the area I live there are a lot of infections now, this is I think because a lot of students live here and they are less responsible’’

- Informant 11 “I don’t use shopping carts or baskets unless I have to, like only when I do grocery shopping for the entire week since I am not able to hold all of the groceries in my hands. I started using it less, because I try to touch as little things as possible in the stores because of the virus and since the stores don’t sanitize the carts or baskets. If the stores would sanitize them, then I would probably use them again.”

- Informant 12 When it comes to using checkout informants 2, 3 and 15 mentioned that they use self-checkouts, when possible, to not be in contact with other people. While the rest of the informants make their choice depending on availability and length of queue.

“I use the self-checkout counter so I don’t have to get close to anyone and I can do everything at my own pace and don’t have to stress, it is quite nice in the grocery store I go to there are a lot of self-checkout and less normal checkouts, so usually I will just go to the self-checkout counter’’

29 “I go to the self-checkout counter because normally where I go there are less people in that store so it is easier for me to keep my distance, especially in Sweden I like to do it as people here don’t wear face masks and some don’t keep distance and walk close by. So I try to do what I can to minimize the spread of the virus.”

- Informant 14

“I try to use self-checkouts so I don’t have to get close to other people, but also out of respect for those who work there, since they want people to use the self-checkout more. But it can also depend on the length of the queue. If the queue is longer in the self-checkout then I would go to the manned check out.”

- Informant 15

Looking at the quotes above it can be identified that the informants increased their use of hygienic products as a result of the COVID-19 virus, and this type of behavior is also described by Anatasiadou et al. (2020), in which consumers are more likely to buy or use hygienic products during the outbreak of a pandemic. However, during the period of COVID-19 the informants tried to avoid touching objects and therefore used shopping carts less frequently or started using the self-checkout counter more frequently, to keep distance from others.

4.1.3 Comparison of objects

After having identified which objects each informant uses during the two periods, a comparison has been made where an overview of the main changes are illustrated in figure 2. Detailed tables are provided in appendix 3, where the objects used by each informant and the changes in the use of objects are presented.

Figure 2: Overview of changes in Objects

Use of hand sanitizer: Informants increased the use of hand sanitizer to stay clean and avoid getting infected by the COVID-19 virus.

Use of shopping cart/basket: Informants reduced their use of shopping carts and baskets in the store.