Parental Support

on the

Nascent Entrepreneur

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 Credits

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Strategic Entrepreneurship AUTHOR: Jordan-Dawn De Laender & Antonia Focke JÖNKÖPING May 2021

An Empirical Study on the Emotional Support

Provided by Entrepreneurial Parents

II

Acknowledgment

This Master Thesis is a final part to close off our studies of the Master’s program in Strategic Entrepreneurship at the Jönköping International Business School (JIBS). During the period of writing this thesis, we stumbled upon various successes as well as barriers; which together we have conquered with the help and support of various people to whom we want to express our gratitude. Both of us have learned quite a lot during these past few months. Not only have we gained more knowledge on our thesis subject but also transformed the obtained knowledge into rightful recommendations and advice to our target audience. Therefore, we are proud of the final result of this Master Thesis.

First, we would like to give special regards to our supervisor Tommaso Minola, who guided us through the writing process and supported us with valuable insights and feedback. Even when in doubt, he assured us that we were on the right track and allowed us to move forward in our study with his additional advice and tips.

Moreover, we would like to thank our fellow students, who also provided constructive feedback and recommendations to further improve our thesis during the various (online) seminars. Also, we are thankful to JIBS and its resources for giving us the right preparation as well as the possibility of conducting this thesis.

Furthermore, we would like to thank all our interviewees again, who offered their time to share with us their valuable insights on their very personal experiences. As they are the core of our research, their commitment has contributed significantly to the quality of our research.

Finally, we would like to thank our families and friends for their emotional support during the past months. With that being said, we hope that the topic of our Master Thesis is as interesting for the reader to read, as it was for us to research.

Tack så mycket, Antonia & Jordan

III

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Parental Support on the Nascent Entrepreneur – An Empirical Study on the Emotional Support Provided by Entrepreneurial Parents

Authors: Jordan-Dawn De Laender & Antonia Focke Tutor: Tommaso Minola

Date: 2021-05-24

Key terms: Entrepreneurship, Entrepreneurial Parents, Emotional Support, Family Business, Nascent Entrepreneur, Parental Emotional Support, Social Support

Abstract

Background: Receiving social support facilitates the founding of a nascent entrepreneurs’

business. Support that is received from entrepreneurial parents contributes towards the development of the entrepreneur’s capabilities as well as potentials, thus, shaping the nascent entrepreneur. Our study will focus on one part of social support, namely emotional support, provided by entrepreneurial parents. While parents intend to positively influence the nascent entrepreneur’s well-being and emotional stability, the exchange of support happens rather simultaneously and unconsciously.

Purpose: This thesis aims to create a better understanding of the influence of entrepreneurial

parents concerning the support system received by a nascent entrepreneur when in the founding stage. Therefore, creating theoretical consistency in the form of a developed conceptual model, which can be put into the broader context of family business and entrepreneurship.

Method: Ontology – Relativism; Epistemology – Social Constructionism; Research Approach

– Inductive; Methodology – Exploratory Study; Data Collection – 15 Semi-structured interviews with nascent entrepreneurs and three interviews with entrepreneurial parents; Sampling – Purposive, Convenience and Snowball Sampling; Data Analysis – Grounded Analysis.

Conclusion: The influence of entrepreneurial parents affects the support approach of a nascent

entrepreneur. Specifically, it contributes to the development of the entrepreneur’s entrepreneurial competence and spirit, which in its turn enhances the entrepreneurial activities connected to the founding of a new business.

IV

Table of Contents

Acknowledgment ... II

Abstract ... III

Table of Contents ... IV

1. Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Research Problem ... 2 1.3 Purpose ... 32. Theoretical Background ... 4

2.1 Literature Review Process ... 4

2.2 The Origin of a Nascent Entrepreneur ... 5

2.2.1 The Nascent Entrepreneur ... 6

2.2.2 Entrepreneurial Intentions ... 6

2.3 Family as a Resource ... 8

2.3.1 Acquisition of Resources ... 9

2.3.2 Social Capital ... 11

2.3.3 Family Social Capital ... 13

2.4 Social Support ... 13

2.5 Emotional Support in the Family Context ... 15

3. Methodology ... 18

3.1 Research Philosophy ... 18

3.2 Research Approach ... 19

3.3 Research Design ... 20

3.4 Data Collection ... 20

3.4.1 Sampling of Primary Data ... 21

3.4.2 Interview Design ... 24

3.5 Data Analysis ... 25

3.6 Research Quality ... 28

3.7 Ethical Considerations ... 30

4. Empirical Data ... 32

4.1 Background and Entrepreneurial Motivation ... 32

4.2 Family as a Resource and Emotional Support ... 38

V 5.1 Results ... 49 5.1.1 Entrepreneurial Parent ... 49 5.1.2 Support Approach ... 54 5.1.3 Social Support ... 58 5.1.4 Nascent Entrepreneur ... 62 5.2 Model ... 66

6. Conclusion ... 69

7. Discussion ... 71

7.1 Theoretical Implications ... 71 7.2 Practical Implications ... 72 7.3 Limitations ... 73 7.4 Future Research ... 758. References ... VII

9. Appendix ... XIII

VI

Figures

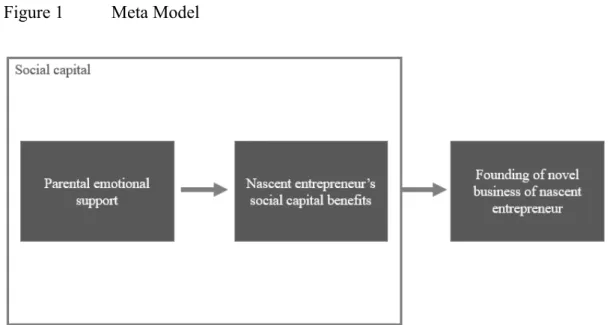

Figure 1 Meta Model ... 17

Figure 2 Our Coding Tree ... 26

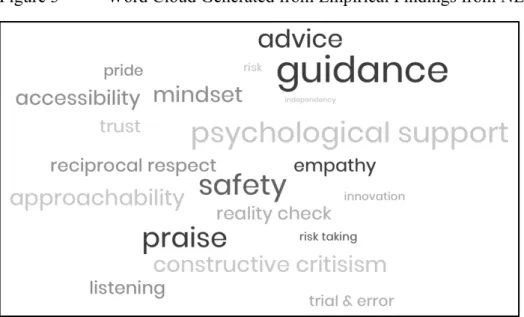

Figure 3 Word Cloud Generated from Empirical Findings from NE ... 47

Figure 4 Our Model ... 67

Tables

Table 1 Overview Interviewee Participants ... 22Appendix

Appendix 1: Definition Table ... XIII Appendix 2: Snippet of the Literature Review (Exemplary) ... XV Appendix 3: Structure of Mapping the Literature ... XVI Appendix 4: LinkedIn Post ... XVII Appendix 5: Interview Guide (Questions) ... XVII Appendix 6: Files ... XVIII Appendix 7: Our Coding Tree Example ... XIX Appendix 8: Linking our Findings ... XIX Appendix 9: Snippet Analysis (Exemplary) ... XX

Abbreviations

1

1. Introduction

______________________________________________________________________ This section of our master thesis aims at presenting a general introduction to the topic. First of all, the background of parental emotional support to nascent entrepreneurs will be presented, followed by a description of the research problem. Further, we will define the purpose of this research study which will then lead to the formulation of our research question.

______________________________________________________________________

1.1 Background

Nascent Entrepreneurs (NE) discover an idea from scratch or recombine pre-existing ideas in order to create a new venture (Aldrich & Cliff, 2003; Ruiz-Palomino & Martínez-Cañas, 2021). However, not all entrepreneurial intentions are eventually followed by undertaken actions (Ruiz-Palomino & Martínez-Cañas, 2021). Therefore, NE require both tangible and intangible resources to transform their intentions into actions (Chang et al., 2009; van Weele et al., 2020). While researching the general means of intangible resources, we have identified that social support as part of social capital appeared to be an important asset to NE. Social support is defined as “the perception/experience that one is loved, cared for by others, esteemed, valued and part of a mutually supportive social network” (Edelman et al., 2016, p. 430), which is mainly distinguished between instrumental and emotional support. Studies have highlighted that in entrepreneurial families, social support notably differs from the social support provided by non-entrepreneurial families (Baluku et al., 2020; Edelman et al., 2016; Forcadell et al., 2018; Luis-Rico et al., 2020; Powell & Eddleston, 2017). Therefore, we want to focus on the connection of entrepreneurial parents1 as they play an essential role in the life of their children. Moreover, they already influence the NE throughout their early entrepreneurial life, as they imprint their children with entrepreneurial behavior, are role models, or influence their entrepreneurial intentions (Aldrich & Kim, 2007; Chang et al., 2009; Jayawarna et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2013; Kirkwood, 2007; Ruiz-Palomino &

Martínez-1 In the following, for a better reading flow we refer to the plural in the term “entrepreneurial parents” even when there is only one parent (either mother or father) entrepreneurially active.

2

Cañas, 2021; Staniewski & Awruk, 2017). Consequently, resulting in influencing the children’s capabilities and potentials towards an entrepreneurial career (Soleimanof et al., 2021). From the literature, we have seen that entrepreneurial parents’ interaction – such as providing motivation, sense-making, dealing with challenges, etc. (Arregle et al., 2015) – stimulates the NE in pursuing entrepreneurial endeavors; also referred to as emotional support. Emotional support by entrepreneurial parents is therefore a distinctive contribution towards the well-being and emotional stability of the NE (Arregle et al., 2007; Edelman et al., 2016; Pearson et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2014). Thereby aiming at enhancing entrepreneurial actions despite potential entrepreneurial risks and obstacles, for example, related to financing or stress (Arregle et al., 2015; Edelman et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2013; Leung et al., 2020; Minnotte & Minnotte, 2018).

1.2 Research Problem

From the previous section, we can see that emotional support provided by parents with an entrepreneurial background (in the following parental emotional support) plays an essential role in the entrepreneurial intentions of NE (Cardella et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2020; Zanakis et al., 2012; Zellweger et al., 2011). However, there is yet a lot to discover concerning emotions, referring to feelings, as well as sentiments, such as nostalgia and memories, in family business and entrepreneurship research (Berrone et al., 2012; Gottlieb & Bergen, 2010). In the past, literature has used both instrumental and emotional support to research family support for NE (Edelman et al., 2016; Powell & Eddleston, 2017). Hence, both types of support were researched. However, emotional support is rather intangible and, thus, can lead to case-related findings which cannot be generalized into the broader context of family business and entrepreneurship (Edelman et al., 2016; Klyver et al., 2018); meaning, there is a need for conceptual research on emotional support. Also, the lack of theoretical consistency in literature among the parents’ support to NE who are founding a new business suggests room for further research (Gimenez-Jimenez et al., 2020; Soleimanof et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2020).

The exchange of emotional support among parents and their children pursuing entrepreneurial endeavors happens simultaneously and most of the time unconsciously; some might take it for granted without appreciating or questioning the added value that

3

emotional support provides (Klyver et al., 2018). However, it remains unclear as to how parental emotional support is directly linked to the founding of a new business and whether it enhances or diminishes the founding process (Klyver et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2020). For that reason, we want to put our focus on parental emotional support as a part of social capital for NE who are founding a new business.

As highlighted by one of our respondents throughout our study: “It doesn't matter how successful the self-employed household was […] but this freedom to decide for yourself what and how I do and to be my own fortune forge, I think of course that's in you, but you get a good portion of home then also” (Respondent B). We want to form a deeper understanding on this “portion” that nascent entrepreneurs tend to receive from their entrepreneurial parents, thereby, laying a special focus on the support approach.

1.3 Purpose

Thus, the objective of our master thesis is to provide a better understanding of the influence of emotional support that NE receive from their parents with entrepreneurial backgrounds. We also consider how this insight might help us to better understand the role of the family in new venture creation to enhance or diminish NE’s new business founding. The outcome of our research will contribute to the existing literature as additional insights on emotional support provided by entrepreneurial parents will be given; therefore aiming at closing the research gap in the literature. Furthermore, it helps entrepreneurial parents as well as NE in providing and receiving emotional support more actively. In addition, our study can enhance the way entrepreneurial parents lead their children towards their entrepreneurial future. However, the focus of our empirical research mainly lies on the NE’s insights since they received emotional support. Thus, we focus on how they are (un-)consciously influenced by their entrepreneurial parents as well as how the support was received. Therefore, we will elaborate on the way they have experienced the founding of a new business.

For this, we defined a research question that is guiding us along with our research: How does parental emotional support influence the nascent entrepreneur during the founding phase?

4

2. Theoretical Background

______________________________________________________________________ Before we will provide an overview of the literature, we will start by introducing the process of how we conducted the literature review. Then go over outlining the theory, starting from the origin of NE and their intentions to create a new business. Further, we will continue with the family as a resource. Here we look at the family, more specifically parents, and how they play a role in the founding of a new business by their child. From there, we will shift our focus onto social capital as a family resource. Following this, we will deepen ourselves into the topic of emotional support, which is part of social capital, provided by parents to their entrepreneurial children. Here the lack of research will be disclosed as well as the formulated research question for this thesis.

______________________________________________________________________

2.1 Literature Review Process

Prior research is described as already existing information in the form of written publications that have been collected by the researcher (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018; Saunders et al., 2016). In our study, we used this in the form of a literature review with the help of the search engine Scopus, supported by Google Scholar to gain a deeper understanding of the background of our research. We chose to use both search engines since they are easy navigation tools for academic papers while also providing access to a database of the world’s research literature (Elsevier, 2021; Google Scholar, 2021).

Throughout our search for publications we mainly directed ourselves towards academic articles which are peer-reviewed and published in journals that scored highly on the ABS-list of 2018; meaning with a high impact factor of three or above (Chartered Association of Business Schools, 2018). Within the search engines, we initially utilized keywords – such as “new venture”, “nascent entrepreneur”, “family involvement”, “entrepreneurial parents”, “parental support”, etc. – relevant to our research topic. Later on, we connected our main keywords with a Boolean operator – for example, “emotional social support” AND “parents” AND “entrepreneurship” – to narrow down our results on the search engine even more. The search results were ordered in terms of “relevance” which allowed us to scan the results most relevant to our topic. Through careful assessment (Appendix

5

9.2) we were able to scan and select relevant articles in regards to their title, abstract, and registered keywords on the search engines. In addition, we also looked at similar articles which were either cited by or have cited our previously found articles and are thus relevant to our research topic.

To track our step-by-step process on how we found the articles utilized in this study, we created an Excel spreadsheet (Appendix 9.3). In the file, we recorded all the keywords and Boolean searches while also adding an overall summary of each found article; thus, we created a systematic and structured overview for us both and so facilitated the development of the literature review. Through this method, we were able to synthesize findings and critical perspectives on themes within our research topic. Starting with the NE, their entrepreneurial intentions, and the founding stage. Then we went over into the family’s perspective, with a specific focus on parents with an entrepreneurial background, how they contribute towards the new business of the NE, and as well as to the NE’s social capital. Further, we deepened our knowledge into social support, as part of social capital, and focused on the close relationships that entrepreneurs have with their parents; therefore resulting in emotional support that parents provide when their children are in the stage of founding a new business. From our literature review, we were able to identify gaps which we then turned into the research problem, the research question, and also led to the development of the interview guide for the primary data collection.

In the following, we will focus on the various topics related to our research question. For a better overview of the theoretical part, we summarized our findings in a table that is retrievable in Appendix 9.1.

2.2 The Origin of a Nascent Entrepreneur

The concept of entrepreneurship has been described as a dynamic and multidimensional process (Cardella et al., 2020; Ruiz-Palomino & Martínez-Cañas, 2021; Wang et al., 2018). It starts with an opportunity that has emerged, either created from scratch or through the combination of pre-existing attributes and followed by actions and phases undertaken to pursue that opportunity (Aldrich & Cliff, 2003; Chang et al., 2009; Ruiz-Palomino & Martínez-Cañas, 2021). However, those start-up activities take place in no

6

particular sequence but depending on the approach utilized these can either facilitate or hinder the entrepreneurial process (Edelman et al., 2016; Ruiz-Palomino & Martínez-Cañas, 2021).

2.2.1 The Nascent Entrepreneur

For this study, we will utilize the term “nascent entrepreneur” to describe the individual that undertakes those activities in the entrepreneurial process. A nascent entrepreneur is defined as an individual that is engaged in activities with the intention to start the creation of a new business (Zanakis et al., 2012); “self-employed” and “founders” are alternative terms generally used in literature for describing entrepreneurs (Aldrich & Cliff, 2003; Arregle et al., 2015; Jayawarna et al., 2014). Furthermore, in a study by Løwe Nielsen et al. (2017), an entrepreneur is called “nascent” when they find themselves at the beginning stage of a new business; which we will refer to in this study as the founding stage. The study further explains that during the founding stage ideas arise and are being explored by the entrepreneur to find business opportunities (Løwe Nielsen et al., 2017; Ruiz-Palomino & Martínez-Cañas, 2021). Therefore, leading to the entrepreneur’s business intentions.

2.2.2 Entrepreneurial Intentions

Actions that a NE pursues to chase the opportunity, face challenges, and grow the new business (Chang et al., 2009; Kirkwood, 2007; Muñoz-Bullón et al., 2019; Ruiz-Palomino & Martínez-Cañas, 2021) are called entrepreneurial behavior (Abbasianchavari & Moritz, 2020). An individual’s entrepreneurial behavior is formed by their characteristics and the ability to get access to means (Abbasianchavari & Moritz, 2020). In addition, literature has stated that entrepreneurial intentions shape one’s entrepreneurial behavior (Cardella et al., 2020; Chlosta et al., 2012; Jayawarna et al., 2011).

Entrepreneurial intentions are influenced among others by the correlation of (1) entrepreneurial self-efficacy, (2) parental role models, and (3) entrepreneurial education (Cardella et al., 2020; Jayawarna et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2018). First, entrepreneurial self-efficacy is a process where entrepreneurs assess themselves through social comparison with peers – for example, accomplishments, business performance, or

7

personal abilities – and social persuasion by close environment and/or external stakeholders (Wang et al., 2018). Research concerning the link between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and the role of the family has been done comprehensively in prior studies. Main findings state that the family background boosts the entrepreneurial self-efficacy of NE due to the presence of family role models (Abbasianchavari & Moritz, 2020; Hoffmann et al., 2015; Lindquist et al., 2015; Palmer et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2018); as a result, NE experience minor fears of entrepreneurial failures (Abbasianchavari & Moritz, 2020).

Secondly, parental role models are an individual’s tendency to identify themselves with their environment, more specifically with their parents, while engaging in social and cognitive behavioral patterns (Cardella et al., 2020). Parents are serving as early role models for their children by providing exposure, interaction, and guidance through the parents’ own business experiences (Abbasianchavari & Moritz, 2020; Botha, 2020; Hopp et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2013; Mathias et al., 2015; Pittino et al., 2018; Ruiz-Palomino & Martínez-Cañas, 2021; Sørensen, 2007). In entrepreneurship literature this is also called “parental imprinting” (Kim et al., 2013; Mathias et al., 2015), meaning that parents create a positive attitude of their children through their own entrepreneurial experiences and exposure towards undertaking entrepreneurial activities (Abbasianchavari & Moritz, 2020; Gimenez-Jimenez et al., 2020; Palmer et al., 2019; Zellweger et al., 2011). However, there is also a downside to role modeling, when parents with entrepreneurial backgrounds experience unsuccessful business outcomes an aversion of the children’s attitude towards entrepreneurship might occur (Criaco et al., 2017; Gimenez-Jimenez et al., 2020; Mungai & Velamuri, 2011; Pittino et al., 2018).

Lastly, entrepreneurial education is a cognitive process where an individual obtains knowledge, forms beliefs, and learns from experiences through (in-)formal learning objectives which are direct learning and observations (Hickie, 2011; Jayawarna et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2018). Entrepreneurial education can be used by NE as a tool to gain self-confidence and security when creating a new business (Cardella et al., 2020). Prior studies have shown that parents with entrepreneurial backgrounds are a source for these learnings and experiences (Bloemen-Bekx et al., 2019; Soleimanof et al., 2021). Moreover, children growing up in entrepreneurial families are exposed to entrepreneurial

8

career intentions; through involvement in the family business where they can also gain social and human capital useful for their own (future) entrepreneurial endeavors (Bloemen-Bekx et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2018).

Moreover, arousing entrepreneurial interests happens admittedly unintentionally (Ruiz-Palomino & Martínez-Cañas, 2021), this is often formed throughout adolescence where the family background plays a key role (Abbasianchavari & Moritz, 2020; Luis-Rico et al., 2020; Pittino et al., 2018; Ruiz-Palomino & Martínez-Cañas, 2021; Wang et al., 2018). In literature, the findings concerning the role that family plays are mixed, mainly because there is no significant evidence that the presence of entrepreneurial family members influences the entrepreneurial interests of a child (Soleimanof et al., 2021). Other studies have found that prior professional experiences and the media are other influences on an individual’s interests (Aldrich & Kim, 2007). However, studies have proven that family members, more specifically parents, contribute to an individual’s motivations, values, attitudes, and early education that shape the NE’s intentions (Jayawarna et al., 2014; Luis-Rico et al., 2020). “Not all intentions are followed by actions” (Ruiz-Palomino & Martínez-Cañas, 2021, p.3); therefore, the role that family members take to stimulate NE in pursuing their entrepreneurial intentions is important according to literature (Kotha & George, 2012; Rogoff & Heck, 2003).

2.3 Family as a Resource

“Families are an important source of the oxygen that fuels the fire of entrepreneurship”, (Rogoff and Heck, 2003, p. 561); meaning, entrepreneurship is comparable to a fire that needs resources, such as family structures, to be maintained. Prior studies have shown that entrepreneurs commonly choose to utilize their close environment, also known as “family, friends and fools” (Kotha & George, 2012, p.1), to get easy access to valuable resources (Kotha & George, 2012; Ruiz-Palomino & Martínez-Cañas, 2021). Family, more specifically when having an entrepreneurial background, is a key source of initial capital for entrepreneurs (Anderson et al., 2005) to easily acquire and accumulate resources internally and at a low cost (Arregle et al., 2015; Forcadell et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2020), mainly due to its close ties and personal relationships (Aldrich & Cliff, 2003; Arregle et al., 2015; Kotha & George, 2012; Ruiz-Palomino & Martínez-Cañas, 2021).

9

Having an entrepreneurial background plays an important role in the social ties of the entrepreneur and as a foundation for financial, human, physical, and other resources (Aldrich & Cliff, 2003). It can also provide NE with social networks such as suppliers, business partners, or even customers (Ruiz-Palomino & Martínez-Cañas, 2021; Soleimanof et al., 2021). Moreover, family relationships are based on trust (Anderson et al., 2005; Arregle et al., 2007; Soleimanof et al., 2021), the entrepreneur can rely on the family members as they will provide their most valuable capital (Arregle et al., 2015; Soleimanof et al., 2021).

By having a look into the family system as one of the most important subsystems in which individuals grow and develop psychological determinants (Staniewski & Awruk, 2017), parents can play a particular role. As mentioned previously, especially their trait as role models can influence NE via business exposure (Aldrich & Kim, 2007; Carr & Sequeira, 2007; Gimenez-Jimenez et al., 2020; Jayawarna et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2013); more particularly when they are entrepreneurs themselves (Carr & Sequeira, 2007; Kirkwood, 2007). Moreover, studies have found that children from entrepreneurial families do not always have the intention of taking over the family firm and instead want to pursue other career (entrepreneurial) opportunities (Gimenez-Jimenez et al., 2020; Zellweger et al., 2011). However, children who are raised in an entrepreneurial family, where the parents are self-employed, are more likely to become entrepreneurs by themselves (Abbasianchavari & Moritz, 2020; Kim et al., 2013; Palmer et al., 2019).

2.3.1 Acquisition of Resources

NE usually start their entrepreneurial process with the search for access to resources (Baluku et al., 2020; Chang et al., 2009; van Weele et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020). Past experiences in new business creation or prior industry, as well as obtained market knowledge by NE, eases this process of getting access to valuable resources compared to entrepreneurs without these experiences or prior knowledge (Ammetller et al., 2014; Kotha & George, 2012). Although, over the past couple of years, many efforts have been taken by governments, business institutions, and incubators to remove barriers for NE – such as providing access to grants, counseling services, and rationalizing administrative procedures – making it more attractive to establish a new business (Ammetller et al.,

10

2014; Jayawarna et al., 2011; Luis-Rico et al., 2020; Muñoz-Bullón et al., 2019). However, as previously mentioned, entrepreneurs tend to reach out to their family for initial capital (Anderson et al., 2005) which is why we will direct our focus on the types of resources that NE commonly receive from the family’s perspective.

During the founding of a new business, NE are more focused upon obtaining tangible resources as initial capital which are physical objects such as workspace, appropriate equipment, and funding (van Weele et al., 2020). The latter can also be obtained through financial institutions. However, in most cases, these institutions are hesitant to hand out loans due to the perception that new businesses are high-risk investments; therefore, funding can be seen as a common tangible resource that NE receive from the family since it is less costly (Jayawarna et al., 2011; Kotha & George, 2012; Lindquist et al., 2015; van Weele et al., 2020; Vladasel et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020). In general, tangible resources are used as a foundation for the new business, and therefore, they are important to NE (Edelman et al., 2016). As a result, the importance of intangible resources is being neglected (Edelman et al., 2016; van Weele et al., 2020).

Intangible resources are non-physical resources and can be divided into three types: network, legitimacy, and business knowledge (van Weele et al., 2020). First, legitimacy which includes a track record of the new business’ performance intertwined with the reputation of the family background with whom the business and its founder are associated. Second, business knowledge consists out of motives, attitudes, skills, and information that shapes the NE’s behavior and so influences the new business’ performance (Chang et al., 2009; Ruiz-Palomino & Martínez-Cañas, 2021; van Weele et al., 2020; Vladasel et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020). Lastly, the network consists out of the family’s connections obtained from years of experience in being professionally active (Anderson et al., 2005; van Weele et al., 2020).

Besides this, the entrepreneurs’ family is commonly perceived as a bundle of resources: due to interaction between the two systems of family and business. A combination of social, human, financial, and physical capital is created as family capital or family’s capital (Forcadell et al., 2018). Moreover, findings have shown that family members provide NE with access to a broad range of connections (Aldrich & Cliff, 2003; Kotha &

11

George, 2012). Those connections can lead to the further development of a NE’s social capital which they need to pursue their entrepreneurial actions and create value for their new venture (Arregle et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2018).

2.3.2 Social Capital

Social connections are a complex network on a personal and organizational level (Anderson et al., 2005) which can be a valuable resource to the entrepreneurs as they facilitate the entrepreneur’s access to general resources, e.g. financial capital or distribution channels (Aldrich & Cliff, 2003; Forcadell et al., 2018). Those networks of relationships are often the basis for social capital as it is the goodwill of social relations by providing valuable resources towards the NE (Arregle et al., 2007). Social capital is the sum of the resources that are available and derived through this network of relationships (Pearson et al., 2008). The term is often used as an umbrella term for “informal organization, trust, culture, social support, social exchange, social resources, embeddedness, relational contracts, social networks, and interfirm networks”, (Adler & Kwon, 2002, p. 18). Finally, it facilitates the process of gaining access to information, resources, and social approval (Edelman et al., 2016; Gimenez-Jimenez et al., 2020) and thus, influences the net value of social capital (Adler & Kwon, 2000) which facilitates the entrepreneurs’ startup activities (Aldrich & Cliff, 2003; Arregle et al., 2015).

From an organizational perspective (Adler & Kwon, 2000), social capital can be seen from three interrelated dimensions, these are defined as: structural, relational, and cognitive (Adler & Kwon, 2000; Arregle et al., 2007; De Carolis & Saparito, 2006; Forcadell et al., 2018; Nahapiet, 1998). The structural dimension of social capital refers to the structure of a network and the pattern of the ties between the involved individuals. The relational dimension refers to the nature and the quality of the personal relationships that develops between these individuals (Arregle et al., 2007; De Carolis & Saparito, 2006; Nahapiet & Ghosal, 1998); which later on manifests in both strong and weak ties. Moreover, other assets are built such as trust, norms, obligations, and identification (De Carolis & Saparito, 2006; Nahapiet & Ghosal, 1998). Especially trust plays a unique role in the relational dimension as it can enhance or hinder information flows (De Carolis & Saparito, 2006). Both the structural and the relational dimensions help NE in the

sense-12

making of emerging opportunities (Jayawarna et al., 2011). However, the last dimension helps them to make sense of information in general as it is the cognitive dimension (De Carolis & Saparito, 2006). This draws attention to the skills required to establish and maintain the relationships (Jayawarna et al., 2011) by providing shared language and narratives, but also shared interpretations, representations, and systems of meaning (Arregle et al., 2007; De Carolis & Saparito, 2006; Nahapiet & Ghosal, 1998). All dimensions have two characteristics of social capital in common: it is inherent in relationships between and among individuals – so it is owned by them and cannot be traded easily such as a tangible resource – and it facilitates the actions of the involved individuals (Nahapiet & Ghosal, 1998).

From that, we draw the impression that social capital provides certain benefits towards the founding of a new business of NE. Adler and Kwon (2000) have summarized the discovered social capital benefits found in literature into three main ones. The first one being information access, referring to the facilitation and reduced cost of gaining knowledge and information through a social network (Adler & Kwon, 2000; Anderson et al., 2005; Lindquist et al., 2015). The second is power as social capital leads to competitive advantages (Adler & Kwon, 2000; Vladasel et al., 2020) as well as facilitates the task-completion as it can enhance the collaboration within a group (Adler & Kwon, 2000). Lastly, there is solidarity being norms, beliefs, and rules in a network that can lead to closer ties and encourages the members of a network to comply with them (Adler & Kwon, 2000; Luis-Rico et al., 2020; Pearson et al., 2008).

Moreover, literature refers to two forms of social capital: bonding and bridging capital (Davidsson & Honig, 2003; De Carolis & Saparito, 2006). At this, the quality of the network relationship is important. Strong ties are based on the core family and romantic relationships (Gottlieb & Bergen, 2010) but also frequent contact and a long-term relationship such as with family, friends, and close communities (Anderson et al., 2005; Edelman et al., 2016). They can provide bonding social capital. The likelihood of using these resources at the beginning of running a venture is higher (Davidsson & Honig, 2003) since the resources are well-focused on the specific needs of the NE and the future business (Anderson et al., 2005). Weaker ties are based on short-term relationships (Edelman et al., 2016), they are emotionally distanced (Anderson et al., 2005). However,

13

here bridging social capital is used and needed for the long-term. One reason is the broader knowledge that a distant network has (Davidsson & Honig, 2003). Another reason is the problem that bonding social capital might bring in, this being that the focus often does not go beyond the entrepreneur’s scope (Anderson et al., 2005) and an inward-looking perspective is thus taken on (Arregle et al., 2015).

2.3.3 Family Social Capital

In particular, family social capital is social capital limited to the family members as a source, creator, or user of unique resources (Arregle et al., 2007; Forcadell et al., 2018; Pearson et al., 2008). It is fundamental for entrepreneurial actions (Campopiano et al., 2016). Family social capital is information channels and family norms such as obligations and expectations among each other, collective trust, identity, and moral infrastructure. As social capital is provided by other networks also the family social capital is developed through iterative, dynamic, and trustworthy relationships (Chang et al., 2009). Therefore, trust plays a crucial role in family relations (Arregle et al., 2015).

2.4 Social Support

As mentioned previously, social support is one part under the umbrella of social capital as a resource (Adler & Kwon, 2002), the term can also be the foundation of health, happiness, and well-being (Jacobson, 1986; Klyver et al., 2018; Minnotte & Minnotte, 2018; Suurmeijer et al., 1995). Social support, in general, is seen as the experience and perception of an individual that one is loved, respected, cared for by others, valued, and part of a mutually supportive social network (Edelman et al., 2016). This can be received from private and professional networks, whereby, as mentioned before, private networks have a stronger influence (Edelman et al., 2016; Leung et al., 2020; Turan et al., 2014). Thus, social support is defined by the characteristics of social networks, the environment, and the benefits the network provides (Turan et al., 2014).

Social support is multidimensional and context-dependent. In research, there is mainly the distinction between emotional or socioemotional and instrumental or tangible support (Baluku et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2013; King et al., 1995; Klyver et al., 2018); but also information and appraisal. The last two do not appear to be prevalent in the relationship

14

of business and family (House, 1981). Other equivalent distinctions of social support exist, those being the social exchange and economic exchange where the focus mainly lies on the exchange of something: e.g. financial capital for repayment (Xu et al., 2020). Instrumental support is focused on tangible assistance of providing information or aiming to solve a problem (Edelman et al., 2016; Klyver et al., 2018; Powell & Eddleston, 2017). Whereas, emotional support is reflected in intangible behaviors or attitudes such as listening and understanding (Edelman et al., 2016; Gottlieb & Bergen, 2010; Klyver et al., 2018; Minnotte & Minnotte, 2018), encouragement (Klyver et al., 2018; Leung et al., 2020; Nielsen, 2020; Powell & Eddleston, 2017), promotion of passion towards the venture creation (Klyver et al., 2018; Stenholm & Nielsen, 2019), and positive regard to fuel a positive self-image through the creation of trust, closeness, and a sense of intimacy (Jacobsen, 1986; Klyver et al., 2018; Leung et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020). This resource is perceived to contribute to the NE’s well-being and emotional stability that helps to focus on entrepreneurial actions despite potential obstacles and risks, for example, investments or crises (Arregle et al., 2015; Edelman et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2013; Leung et al., 2020; Minnotte & Minnotte, 2018). In addition, emotional support enhances NE to absorb entrepreneurial knowledge and new information (Klyver et al., 2018), consequently, to use the provided social capital (Arregle et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2018). As mentioned previously, emotional support, which is a sub-division of social support, also falls under the umbrella of social capital (Adler & Kwon, 2002). Therefore, emotional support also affects the ability of a NE to receive social capital (Klyver et al., 2018).

Furthermore, Klyver et al. (2018) put these together and so defined three relatively interdependent mechanisms of emotional support. However, the mechanisms are related to emotions and affect to have an impact on the entrepreneurial activities and its persistence; therefore, to the founding of a new business of a NE. The first mechanism of emotional support is the influence of subjective perceptions by objective means towards a more positive sense; which is labeled as optimism. The external world is seen more positively through emotional support actions like encouragement, the support of creativity, or the ability to deal with stress (Klyver et al., 2018). Second, is belonging and identity, which is the emotional support that shapes the identity feeling of the entrepreneur. Through emotional approval of network ties, the entrepreneurs receive

15

social acceptance and legitimacy for their business activities (Klyver et al., 2018). Lastly, emotional support increases positive feelings towards the engagement in entrepreneurial activities. This mechanism is called entrepreneurial passion, which is strongly present during the starting phase of founding a business but is also to be continuously maintained in the following phases. As mentioned, these three mechanisms can affect the entrepreneur’s new business founding (Klyver et al., 2018).

Literature has shown that both dimensions of social support, namely instrumental and emotional support can intermingle and overlap (Klyver et al., 2018; Nielsen & Klyver, 2020; Stenholm & Nielsen, 2019). Having higher levels of both dimensions result in higher levels of support but also a greater diversity of resources like knowledge, information, and perspectives due to the unique network ties (Klyver et al., 2018). Moreover, research stated that having a lack of social support has negative impacts on the process of starting a new venture (Zanakis et al., 2012). However, it does not mean that having more social support is more beneficial (Farooq et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2013) since the effectiveness of the support depends on the alignment of resources received; here diversity is important to get the most out of it (Kim et al., 2013). Furthermore, social support does not always have a positive impact on the NE or is perceived as helpful. Explanations are lying in the individual characteristics of the entrepreneur and the support provider(s). One example might be arguments within the family context that then lead to negative thought patterns that interfere with business activities (Leung et al., 2020; Minnotte & Minnotte, 2018). Also, the family members could be too involved which might lead to negative effects when receiving support and so hinder the founding activities (Edelman et al., 2016). As a result, individuals having social support available from family are not as likely to provide support to other entrepreneurs. According to Nielsen (2020), the explanation for this is due to those entrepreneurs being more introverted and therefore isolated from external networks.

2.5 Emotional Support in the Family Context

Bonding social capital or closer relationships, as within the family, tend to generate a wider range of support in comparison to weak ties as the support is more specialized (Anderson et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2013; Schröder et al., 2011). People that have strong

16

relationship ties to each other are perceived to be repositories of support (Gottlieb & Bergen, 2010). In general, family support as a contextual factor plays an important role in the entrepreneurial process of having the intention to engage in action towards the founding of a new business (Baluku et al., 2020).

Family support can descend from various sources – such as siblings, romantic partners, or other close ties – which an individual develops throughout their life (Vladasel et al., 2020). In research siblings are considered to be a source of emotional support, however, competition among siblings might occur and so revolve in implications later on in life (Gimenez-Jimenez et al., 2020). Romantic partners, also referred to as spouses, can also be seen as a source of one’s emotional support (Aldrich & Cliff, 2003); but are considered less important compared to close family members in terms of the future entrepreneurial activity of an entrepreneur (Vladasel et al., 2020). As explained previously (in Chapter 2.3), parents can play a particular role in the life of the NE as well as their entrepreneurial intentions. Following this, we focus our study on emotional social support by entrepreneurial parents that either founded a company or are self-employed. Research showed that emotional support by parents is crucial for young entrepreneurs with limited career experience whom are at the early stages of founding a new business (Edelman et al., 2016; Klyver et al., 2018; Luis-Rico et al., 2020); whereas instrumental support plays a bigger role in later stages of the business’ life cycle (Klyver et al., 2018). Parents are willing to support the NE and therefore act in their best interest to overcome certain obstacles. Moreover, NE can access the social capital of their entrepreneurial parents to get early contact with suppliers, business partners, customers, etc. and so facilitate the founding (Edelman et al., 2016). In addition, the proportion of emotional support that NE receive from their parents depends on the type of interactions between both parties which enhances emotional connections, esteem, and mutual understanding (Zhu et al., 2014). Furthermore, findings have shown that family cohesiveness (Edelman et al., 2016; Luis-Rico et al., 2020) and family embeddedness (Arregle et al., 2015) strongly influence the emotional support which parents provide to NE (Aldrich & Cliff, 2003; Arregle et al., 2015; Edelman et al., 2016; Pittino et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2020).

We are focusing our empirical research on emotional support provided by entrepreneurial parents; as explained previously (in Chapter 2.3), they have a special influence on their

17

children regarding their entrepreneurial intentions. We will label this as parental emotional support. The context of parental emotional support, as a helping hand for NE, has been largely understudied in research, and therefore limited information is available in the literature (Berrone et al., 2012; Klyver et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2020). Thus, the influence of parental emotional support on the NE can be defined as the research problem. This leads us to our research question which will be our main focus area throughout our empirical research:

How does parental emotional support influence the nascent entrepreneur during the founding phase?

We summarized our theoretical findings of the relationships in a meta-model (Figure 1). This meta-model facilitates the development of our empirical research process, as we will use this as a guide for the interviews. We chose to create this as research has stated that emotional support is rather intangible and therefore, difficult to measure on its own (Berrone et al., 2012; Klyver et al., 2018). However, the model presents the parental emotional support, being the emotional support provided by entrepreneurial parents to their likewise entrepreneurial children. Hence, the parental emotional support contributes either positively or negatively to the NE’s social capital which influences their abilities when founding a new business (Chapter 2.3.2).

Figure 1 Meta Model

18

3. Methodology

______________________________________________________________________ In this section, we will explain the chosen research philosophy of our thesis including ontology and epistemology. We further go into detail with the research design as well as on our data collection process and the chosen methodology for data analysis. Finally, we are explaining how we ensure data quality and ethical considerations.

______________________________________________________________________

3.1 Research Philosophy

The philosophy of research supports researchers as a foundation, they need to comprehend to have a clear sense of their reflexive role in their study. Knowing which philosophy a study follows is also helpful to know which design and methodology will be applied. In order to better understand the structure of research philosophy, it can be imagined as a tree with roots, the trunk, and resulting in the treetop with its leaves and fruits (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018).

Starting with the roots and the densest part of the trunk of the metaphorical tree: the research tradition ontology. This is the basis of the whole research. Within ontology, the nature of reality and existence is described. Research traditions distinguish between realism, internal realism, relativism, and nominalism ontological positions; these positions are situated on a continuum (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018; Tracy, 2013). Considering that we analyze the relationships between people, being NE and their entrepreneurial parents, many truths are depending on the different points of view.

Our findings will be valid for some entrepreneurs while the opposite is true for other entrepreneurial families due to individual relationships and the influence of variables. Thus, scientific laws are not simply out there to be discovered, they are shaped by people. The truth reveals through discussions and interactions with others; research will be more accurate and credible if it is made from various perspectives. Consequently, the relativist ontology suits best the research of this thesis (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018).

19

Further, the trunk of the research tree is epistemology. It shows views about the most appropriate ways of exploring the nature of the world. Epistemology is the theory of knowledge and tries to enquire it physically and socially. Two constraint epistemological views are introduced: positivism and social constructionism. With a positivism epistemology, the researcher makes sense from the external world and uses objective methods on measuring the results. Social constructionism describes the idea that reality is rather determined by people than by external factors and objectives; the way that people make sense of their experience is thus key. We are taking a social constructionism epistemological perspective since we make sense of the people’s experiences and behaviors, therefore, different perspectives will be incorporated. Our research follows the aim of getting a general understanding of the situation and the whole picture of what people experience. With social constructionism, a rather small number of cases is examined. Thus, we are conducting a qualitative study (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018; Tracy, 2013).

Social constructionism epistemology has its strengths for developing new theories since it enables generalizations beyond the present sample. Thus, the efficiency of data collection might be higher and less unnatural since it mirrors real experiences (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). As mentioned, our findings will be valid for some entrepreneurs while the opposite might be true for others due to individual relationships and influences. However, there are some weaknesses that we also have discovered and included in the research limitations (Chapter 7.3) of this study.

3.2 Research Approach

As indicated, we are researching how people make sense of their world and experiences in it as we are examining the relationship between NE and their entrepreneurial parents; especially how the latter supports the NE. By building further onto existing theory we aim at deepening our knowledge by conducting an in-depth analysis of people’s experiences. In research, three approaches exist for theory development where more insights are given to better understand the topic; as it is currently under-researched in the existing literature (Saunders et al., 2016). These approaches are deductive, inductive, and abductive. We are following an inductive approach as data is first being collected to

20

explore a phenomenon which then aims at creating or building a novel theory (Saunders et al., 2016; Tracy, 2013). Moreover, the insights of our thesis are emerging from the field, behaviors, and experiences which are described by people, as well as context-related. Additionally, we are aiming to draw conclusions that form a conceptual framework and thus, build theory. Besides this, the purpose of a study can be distinguished between exploratory, descriptive, and explanatory (Saunders et al., 2016). Since this can vary over time, our current research purpose can be rather described as exploratory; as we conduct in-depth interviews to analyzing people and their experiences, therefore, gaining new insights.

3.3 Research Design

Following this approach, we conducted semi-structured interviews to collect data; which will be explained in Chapter 3.4.1. Then we engaged in an open line-by-line analysis to create larger themes from the data and linked them together to get the whole picture. By coding our insights, we developed these into a theory. Thus, we are following a grounded theory approach in our thesis as it is an open as well as inductive approach to analyze data while using no pre-defined codes. In our case, the construction of the codes is obtained from the conducted interviews. It is a comparative method as it is focused on the same process but from different perspectives and means. So with this, we can derive a theory out of the primary data; of which we will go more into detail in Chapter 3.5. Later for developing our model, we enrich the gained insights from NE with prior research, which we explained in our literature review, as well as additional perspectives from the entrepreneurial parents. Thus, the grounded theory approach will allow us to combine different types of data to generalize it but also sensitizing the individuals’ experiences (Charmaz, 2014; Easterby-Smith et al., 2018; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Tracy, 2013).

3.4 Data Collection

For this study, we have chosen to combine primary data collection with prior research to get an integrative view of our topic. Therefore, we gathered primary data through in-depth interviews with NE and a few entrepreneurial parents in addition to the data that we retrieved from existing literature. Through the combination of these, we were able to

21

examine the research question from different perspectives and so address understudied themes about our topic. Throughout the process of our data collection, we initially started to collect data from prior research and used that as a base for collecting our primary data.

3.4.1 Sampling of Primary Data

Following the previously discussed research philosophy and research design, we found the qualitative design for primary data collection to be the most appropriate method to link parental emotional support with the process of founding a new business by NE. Here we utilized non-probability sampling designs, such as purposive sampling, convenience sampling as well as snowball sampling, to get a general overview of our topic with the help of a small sample size.

Hence, we used purposive sampling where we defined criteria for our potential participants to evaluate whether they fit our desired sample (Easterby-Smith et al. 2018; Saunders et al., 2016; Tracey, 2013). We chose to mainly focus on interviewing NE, to develop a better understanding of their experiences on receiving parental emotional support when being in the stage of founding a new business as well as in retrospect. In order to enrich these data, we added some viewpoints from entrepreneurial parents as an addition to the insights provided by the NE; hence these insights were not the main focus of our study. In terms of the NE (definition in Appendix 9.1), we selected interview participants that have entrepreneurial parents, acting in various industries and from different company sizes; since our main focus was on emotional support rather than the type of company. In the context of our study, we defined an entrepreneurial parent as an individual who is currently still acting as an entrepreneur of their own business which is different from the business of their child; therefore the child is not the successor of the parents’ business. We also included parents in our sample that have been entrepreneurs before but are currently retired. However, parents that were entrepreneurial in the past but currently employed in a company, which is not their own, were not part of our set criteria and thus excluded from the interviewee selection. An overview of our participant sample can be seen in the following.

22 Table 1 Overview Interviewee Participants

Source: Own elaboration.

The first three columns of Table 1 provide information concerning the interviewed NE; stating when they founded their business as well as the industry they are currently operating in. The remaining columns provide more information concerning the entrepreneurial parents; elaborating whether only one parent or both parents of the NE are entrepreneurs themselves and in which industry they are operating. Thus, a visual comparison can be made, in terms of industry, whether the entrepreneurial parents and their children operate either in the same or in a different one. We also included a column with the duration of each interview for both NE and, in three cases, the parents. It generally varied between half an hour and just over one hour. Here we did not include the small talk before and after each interview; this would be for each interview around ten to twenty minutes more. We also included a column with the participant codes for the NE as well as the entrepreneurial parents whom we were able to interview.

Furthermore, we added a column where we summarized our connection to the respondents. Initially, we utilized convenience sampling, which implies that we reached out to contacts to which we would have easy access (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Hence,

23

we reached out to our personal and online networks (as visible in Table 1), for the following respondents: A, B, C, D, E1, E2, G, I, J, M, and N. We contacted these respondents via telephone, private messaging, and email; to gain our first list of potential interviewee participants. Moreover, we created a post on LinkedIn (see Appendix 9.4) to reach out to our online network; therefore making use of snowball sampling. A sampling approach where we reached out to our network and asked whether they have connections with others who would meet our set criteria for the interviewee participant sample (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018; Tracy, 2013). With this approach, we were able to connect with respondents F, H1, and H2. Further on LinkedIn we used the purposive sampling approach as we also expanded our reach by connecting with entrepreneurs that have participated in contests (e.g. Gentrepreneur Awards) or were mentioned in news articles (e.g. Founders Magazin), being the respondents K, L1, L2, and O. The use of these sampling approaches allowed us to collect a total of 18 interview participants for our study, who provided us with insights on their personal experiences. So, obtaining a better understanding of our thesis topic. From this, we were able to further develop our study’s key themes, which we initially used when creating the interview design.

Purposive, convenience, and snowball sampling fall under non-probability sampling designs, which is a sampling design where the possibility is excluded that each member of the population is represented (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018; Saunders et al., 2016; Tracy, 2013). Our aim for choosing non-probability sampling designs was to focus on “precision” yet obtain quality data relevant through a small sample size. Following the grounded theory approach, we aimed at using the selected sample size to cover the generality of NE receiving parental support. However, we cannot guarantee that our findings will be a replica of the general research group. This could occur due to the character of our sample findings which might lead to contradictions among each other or other similar studies on our topic (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018); but we rather aimed at getting an overall view of our targeted research group. In Chapter 3.6, we will discuss how we aimed at providing quality in our conducted research.

24 3.4.2 Interview Design

As for our research, we chose to utilize semi-structured interviews for collecting primary data. Through this method, we wanted to develop an understanding of our participant’s views on our topic, getting insights on their opinions and beliefs about their experience within the exchange of emotional support during the founding of a business (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). However, there is no step-by-step way of doing so and certain experiences can depend on the context a person finds themselves in. That is why we aimed at gaining an overall view and find similarities among the stories we have heard throughout our conducted interviews.

Due to the current COVID-19 regulations in many countries, we decided to conduct our interviews remotely. Meaning that all interviews were conducted via internet-based video calls. This allowed us and our participants to be more flexible in terms of time and place. However, there was also a downside to conducting interviews remotely. One is the lack of contextualization in both verbal- and body language and another reason being the higher risks in distractions throughout the conversation and sudden (technological) issues; such as internet drop-outs and a lack of experience in utilizing video call software (Tracy, 2013).

In order to form our in-depth interview structure, we first revisited our research questions, research design, and sampling strategy to determine the purpose of our interviews; as suggested by Easterby-Smith et al. (2018). Further, we started to develop an interview guide for semi-structured interviews with the selection of themes, related to our research topic, that need to be covered. From our literature review and also our meta-model (Figure 1), we have identified four main themes: “Entrepreneurial Background Parent or Child”, “Nascent Entrepreneur and Entrepreneurial Intentions”, “Emotional Support”, and “Social Capital”. This to identify the connection between parental support on the founding of a business by NE. Based on the recommendations on structuring an interview guide by Tracy (2013) and Easterby-Smith et al. (2018), we developed the guide (Appendix 9.5). The interview guide starts with (1) opening questions, where the participant introduces themselves and their entrepreneurial story. Then we went over to (2) questions that are linked to our key themes, such as the entrepreneurial background of the parents, the NE and their entrepreneurial motivations, emotional support received by entrepreneurial

25

parents, and social capital of NE. Lastly, (3) closing questions were asked, which gives the participants space to go deeper and provide further insights on the themes beyond the questions asked in the previous segment (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018; Tracy, 2013). Hence, no questions were derived from interview guide examples of prior research, the interview questions were solely formed with the help of our literature review.

We tried to carefully conduct the semi-structured interviews since Easterby-Smith et al. (2018), summed up various interview concerns; such as obtaining trust, appropriate attitude and language, lack of social interaction, an environment where the interviews are held, recording of the interviews, etc. In addition, we steered the interview into a meaningful and pleasant conversation, thereby listening and laddering our questions up and down to understand and reflect on the participants’ experiences. We also gave them room to further elaborate on the benefits and potential downsides of their entrepreneurial journey (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018; Tracy, 2013). When possible, we tried to conduct the interviews in the respondents’ native languages, being either Dutch or German, or in English when the respondents were comfortable to do so. However, all interview transcripts were translated into English by using our translation skills, but also with the help of translation tools such as Google Translate to ensure that we both were able to fully comprehend the insights provided during those interviews. Next to that, we have chosen to not include theoretical terms in the interview questions and conversations. This to make the interview questions clear and easy to understand for someone who has no academic background in the topic. However, at the very end of the interview, we asked one question to our interviewees concerning our main topic which is “parental emotional support”. Our aim with this was to let them interpret and get their thoughts upon the concept without any theoretical or background influences.

3.5 Data Analysis

As explained in Chapter 3.3, we followed a grounded theory approach. This is also reflected in analyzing the data with the aim of building theory from categories that are grounded in the data. Here we applied the seven steps of grounded analysis which is closely linked to grounded theory as well as its comprehensive research. Grounded analysis encourages researchers to be more creative and use their strategies in a flexible

26

way (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018; Glaser & Strauss, 1967), but the researchers’ engagement must be viewed with caution (see Chapter 3.6). Moreover, this approach is time-consuming and can be difficult. However, the potential of gathering new and valuable insights is high. As a practical approach that allows contradicting perspectives and preserves ambiguity, grounded analysis was a right fit for our thesis (Charmaz, 2014; Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). In the following, we will go into detail about how we conducted the coding. Here the seven steps of grounded analysis are used to, in the end, develop a model out of our findings. Our seven steps are summarized in the following figure. We used Microsoft Excel as our main tool for the coding process (see Appendix 9.9).

Figure 2 Our Coding Tree

Source: Own elaboration.

In the first stage, called familiarization, we were getting familiar with our recorded interviews and the insights gained. Therefore, we reviewed the semi-structured interview questions, our notes, and we wrote out the transcripts (Appendix 9.6). In some cases we also translated the interview from either Dutch or German into English, allowing both of us to fully comprehend what has been said during the interview. Thereby we also listened to the audio recordings. With every interview we have reviewed, we reminded ourselves of the focus of our thesis, the research question, and from whose perspective, either NE or entrepreneurial parents, we got insights.

27

The second stage, namely reflection, focuses on the evaluation of the reviewed interviews, audio recordings, and transcripts. Here we kept in mind the theory where we asked ourselves whether these insights from the interviews are supporting existing research. Moreover, we questioned if this would challenge existing research and in which manner. With this in mind, we highlighted the most relevant phrases in the transcripts of the interviews of both NE and parents. After that, we implemented the highlighted quotes of the NE into a table, in Microsoft Excel, sorted those according to the question and theme (see Chapter 3.4.2) to facilitate the coding in the next stage.

Thirdly, the first round of coding the quotes by NE started in the stage of open coding. “A code is a word or a short phrase that summarizes the meaning of a chunk of data” (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018, p. 367). Here we both independently linked the quotes gained from the interviews with our research question and gave every quote a code. To increase the credibility and confirmability of our study, we each did this individually for all the 870 quotes of the NE; therefore diminishing the chance of personal influences and biases in our study. Individually, we defined 187 and 133 codes, so combined in total 320 codes.

The stage of conceptualization can be also called axial-coding as patterns or groups of codes are sought here, which are then organized into categories (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). With this conceptualization, we aimed at getting an overview of the general picture for answering our research question and understanding what is going on. So, we focused on the answers regarding the support receiving and, thus, we created links between the overwhelming data and our individual codes from the open coding into systematic categories. These appeared from a set of codes that seemed to be related or were similar. Moreover, we kept in mind the research question, aim of our research, and defined themes. With this in mind, we were able to link the codes to in total 37 categories related to themes answering our research question. In Appendix 9.7, a coding tree shows exemplary of how we followed the approach of grounded analysis. Moreover, in Appendix 9.6 the whole quotes with codes and categories can be retrieved.

In the fifth stage, being the focused re-coding, we coded again but rather with more detailed codes. In the research literature, this process of re-coding is also called