A Qualitative Look into Auditor’s

Going Concern Assessment

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Civilekonomprogrammet AUTHORS: Aronsson, Jonathan

Granstedt, Adam

TUTOR: Jansson, Andreas

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: A Qualitative Look into Auditor’s Going Concern Assessment

Authors: Granstedt, Adam

Aronsson, Jonathan

Tutor: Jansson, Andreas

Date: May 2021

Key terms: Going concern, going concern opinion, going concern assessment, going

concern concept, GCO

Abstract

Introduction: The history of going concern have been surrounded by uncertainties. The

concept becomes relevant in times of economic crisis. The accuracy of existing procedures concerning GCOs have been questioned, where firms file for bankruptcy without any prior indications of going concern issues. Therefore, it has been questioned if the auditors are better than anyone else to predict the future. The standards and regulations leave out large room for professional judgement, thus there is a great risk of fluctuations in the judgement process in practice. Without a complete understanding of going concern, one could question the added value of the concept, and what conclusions can be made from prior literature.

Purpose: The purpose of our study is to enhance the understanding of the auditor’s going

concern assessment by looking further into their application and treatment of the concept in practice. This will provide a more complete nuanced picture of auditor’s conceptualization and their process of evaluating going concern.

Method: Our purpose in this study is achieved by using a qualitative research method. The

empirical findings are collected through using a semi-structured interview approach. The interview guide is developed from our model (Figure 2) which is derived from previous literature in the field. Our sample consists of 6 authorized auditors from the Jönköping region.

Findings: The findings indicate that the perception shifts based on the process. Going

concern is a difficult assessment, which is highly influenced by subjective judgement. Auditor’s application process in practice can be identified as a step-process. Between these steps, the perception changes. The process is characterized by auditors seeking evidence to the contrary of issuing a GCO.

Acknowledgement

We would like to take the time and bring our sincerest gratitude forward to thank everyone involved, who helped and supported us during this master thesis, for without it would not have been possible. We would like to tribute and pay our gratitude to our supervisor Andreas Jansson, for his continuing support and guidance. His advice and engagement for this thesis have been absolutely incredible and we are beyond grateful.

We also would like to thank all respondents who were willing to participate in our study. The knowledge and experiences of all respondents have been tremendous, and we could not praise enough all the valuable information and insights we derived for this study.

At last, we would like to thank all our fellow students who have put forward feedback on our seminar group sessions, which have with no doubt in mind helped us improve our thesis to what it is.

Thank you!

Jönköping, May 2021

_____________________ _____________________

Abbreviations

IAS – International Accounting Standards

IFRS – International Financial Reporting Standards ISA – International Standards on Auditing

IAASB – International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board US GAAP – Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (United States) IFASS – International Forum of Accounting Standard Setters

SOX – Sarbanes-Oxley-Act 2002. The act presented several reforms to counter corporate

frauds, but also to enhance corporate responsibility and financial disclosures.

Glossary

Subsequent events – Events and conditions that take place after the end of the financial year

and before the auditor’s report.

Type 1 error – When an auditor issues a GCO to a client which subsequently do not have to

file for bankruptcy.

Type 2 error – When an auditor does not issue a GCO to a client that subsequently have to

file for bankruptcy.

Going concern opinion (GCO) – The auditor expresses a risk of failure for their client. Statutory administration report – Management’s description in the annual report of events

and important information that the company has done during the year.

Litigation risk – Is the risk for individuals or companies to face legal actions.

Table of contents

1. Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1

1.2 Problematization ... 3

1.2.1 The concept is unharmonized in theory and regulations ... 3

1.2.2 Implications in practice ... 5

1.2.3 Lack of studies in the literature ... 8

1.2.4 Why is this gap problematic? ... 8

1.2.5 The necessity for research ... 9

1.3 Research purpose ... 10

2. Literature review ... 11

2.1 Theoretical model ... 11

2.2 Definition av going concern ... 12

2.3 Standards and regulations ... 14

2.3.1 Audit regulation, ISA 570 ... 14

2.3.2 Risk assessment methods and related practices ... 15

2.3.3 Financial accounting regulation ... 16

2.3.4 Implications of terms in standards ... 19

2.3.5 GCO in relation to regulatory changes ... 20

2.4 Process ... 22

2.5 Factors influencing auditor's judgement of GCO ... 23

2.5.1 Auditor judgement ... 23

2.5.2 Audit firm size ... 24

2.5.3 Industry specialization ... 25

2.5.4 Litigation and financial risk-factors ... 26

2.5.5 Characteristics of audit personnel ... 27

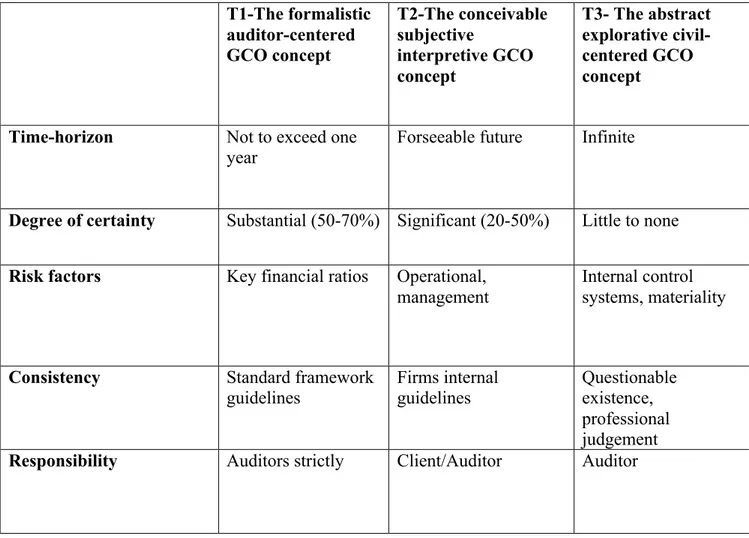

2.6 Development of conceptualization model ... 28

2.6.1 Time-horizon ... 29 2.6.2 Degree of certainty ... 29 2.6.3 Risk factors ... 30 2.6.4 Consistency ... 30 2.6.5 Responsibility ... 31 2.6.6 The formalistic ... 33 2.6.7 The conceivable ... 33 2.6.8 The abstract ... 34 3. Method ... 36 3.1 Research approach ... 36

3.2 Development of interview guide ... 37

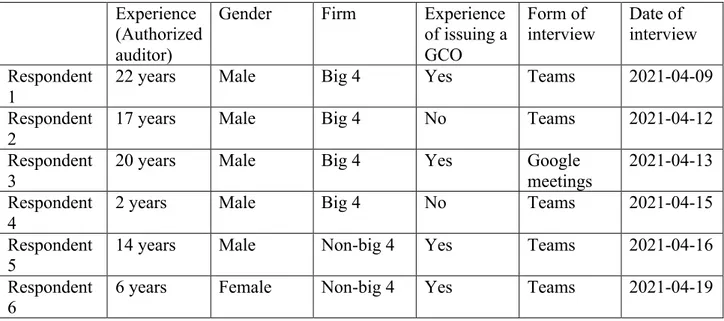

3.3 Data sampling ... 43

3.4 Data collection ... 44

3.5 Critique of chosen research design ... 44

3.6 Overview of respondents ... 45

3.7 Research analysis method ... 45

3.8Ethical consideration ... 47

4. Empirical findings ... 48

4.1.1 Client communications ... 49

4.1.2 Avoidance to issue GCOs ... 53

4.1.3 Balancing act of consequences ... 54

4.2 Individual conceptualization ... 56 4.2.1 Time horizon ... 56 4.2.2 Risk factors ... 59 4.2.3 Consistency ... 65 4.2.4 Degree of certainty ... 68 4.2.5 Responsibility ... 71 5. Discussion ... 76

5.1 Simplified model for assessing a GCO ... 76

5.2 Influence of external factors of process and conceptualization ... 78

5.2.1 Litigation risk and financial risk-factors ... 78

5.2.2 Auditor judgement ... 79

5.2.3 Characteristic of audit personnel ... 79

5.2.4 Industry specialization ... 80

5.2.5 Audit firm size ... 81

5.3 Influence of standards on process and conceptualization ... 82

5.4 Conceptualization applied in process ... 83

6. Conclusion ... 86

6.1 Practical implications ... 87

6.2 Theoretical implications ... 89

6.3 Limitations ... 89

6.4 Suggestions for future research ... 90

7. References ... 91

8. Appendices ... 102

Appendix 1 ... 102

1. Introduction

The first chapter of this thesis includes a background of the problem followed by a

problematization divided into sections to introduce the reader to the subject and its relevance. In the end of the chapter the research purpose is presented.

1.1 Background

Auditors serve as gatekeepers to ensure objectivity and add credibility to the financial information provided by entities to its shareholders and stakeholders (Satava et al., 2006). This function demands auditors to make a correct assessment. To accomplish this, auditors are required to sign an audit report where they have to state whether the entity is a going concern or not i.e., leave a going concern opinion (hereafter GCO). The going concern assumption is a general principle used by managers in the accounting practices when preparing an entity's financial information (ISA 570 §1).

The going concern assumption entails that the entity will be able to operate their business, realize their assets and pay their obligations in the foreseeable future, covering at least twelve months from the date that the financial statements are produced (ISA 570 §13). It is then up to the auditors to collect necessary information to validate the managers going concern

assumption. If the auditors have doubts about the entity's ability to survive, they are obliged to issue a GCO (ISA 570 §6).

There are differences in reporting frameworks whether managers are required to make an assessment regarding the entity's ability to continue as a going concern (IAS 570 §4). However, the problem with the statement is that it is just a judgement at a particular point in time about an uncertain future, which is the same argument often used to criticize the balance sheet in financial statements (Laudato, 2012). In practice, auditors are required to establish if the use of the going concern assumption by management in the accounting is appropriate, on a basis that the entity does not intend to liquidate the business or terminate their trading activity in the near future. However, the going concern assessment for financial reporting is not designed to provide a guarantee about the firm's ability to remain a going concern until the next report is published (Laudato, 2012).

The regulations do not contain a minimum of detail required in the assessment of going concern by management. Instead, they are required to satisfy themselves and justify that it is appropriate to prepare the financial statements on a going concern basis. The level of detail

required in the assessment will vary depending on the complexity and size of the company. However, as a satisfactory minimum requirement it would be advisable to include the preparation of a budget, estimates of trading, a forecast of cash flows and an analysis of the firm's borrowing requirements. For a small, noncomplex entity, it may not be necessary to provide such detailed analysis while for larger companies with complex business models, a more thorough analysis of the economic environment might be necessary considering competitors, market size and market share for example. (Laudato, 2012)

Auditing, as the name suggests, is historically figuring and analyzing in its nature, but the one important question which seeks to explain the future is going concern (Lennartsson, 2020). However, there seem to be a lack of consensus within the auditing profession in relation to the auditor's responsibility concerning going concern (Rodgers et al., 2009). Campbell and

Mutchler (1988) established how some members of the audit profession understand the going concern evaluation to go beyond what is considered the traditional role of the auditor and make judgements of an uncertain future. More recently, Bellovary et al. (2006) argued that auditors are not better suited than any other to predict bankruptcy of a client, questioning the usefulness of the adequate information provided to financial statement users. They even go as far as proposing an elimination of the going concern evaluation (Bellovary et al., 2006). During the current COVID-19 pandemic, this question has been put to the test, and become more important than ever. Following this, a discussion of what information that needs to be disclosed, in relation to the assessment of a company’s situation, have rose among

professional practitioners. New Zealand and Australia have released new standards to clarify the disclosure regarding going concern as the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the diversity in practice (IFASS, 2020). They argue that there is a lack of comparability in the current requirements and issued a request for more guidance which would derive more comparable information for users and provide auditors with an enhanced basis of accounting to give an opinion against. Despite previous critique, Lövgren points out that going concern is always in focus, however this year it has been put to its ultimate point (Lennartsson, 2020).

There seems to be a common pattern that the going concern assumption receives attention in unstable economic times. This should come as no surprise as the GCO only appears if the auditor finds considerable doubts about the firm's capability to continue as a going concern (Carson et al., 2013). Observing previous crises like the Enron scandal and the financial crisis

the Enron case it was the Special purpose entities (SPEs) used to hide debt without it

appearing on the balance sheet. In the financial crisis it was the unexplored new tech industry. Complexity together with incompetence is according to Arnold Brown, chairman of strategic consulting group Weiner, Edrich, Brown, what caused these crises (Cheney, 2009). The current COVID-19 pandemic differs in relation to these earlier crises in the sense that it is not complex accounting methods or new business models creating problems. Despite the

differences, the uncertainties of both crises are the same. Not a single company is unaffected by the on-going pandemic, the only question is to what extent, for how long, and how enduring the company’s balance sheet is (Lennartsson, 2020).

Not only are the troubled firms fearing the inconsistency in the issuance of GCOs, but the audit firms are just as troubled. There have been studies of the accuracy rate of auditors GCOs, where the results have highlighted the inconsistency in practice (Geiger & Rama, 2006). On a question posed to a professional practitioner of auditing about what not to testify about as an auditor, Björn Bäckvall, a chartered accountant at Ernst & Young, discuss going concern as included in assignments of particular risk (Halling, 2017) The reasons why it could be of a particular risk may vary, it is dependent on circumstances, but it is unclear to what degree and who would be harmed in the process. For example, the auditor’s reputation could be harmed if a wrongful decision of GCO is being made, or not. At the same time, a study found that it could protect them if they issue an opinion prior to a bankruptcy (Francis, 2004; Myers et al., 2014).

1.2 Problematization

1.2.1 The concept is unharmonized in theory and regulations

The going concern assessment is one of the most difficult and uncertain tasks an auditor may encounter, which poses problematic situations and tough decisions to be made for the auditor (Carcello & Neal, 2000; Altman & McGough, 1974; Rodgers et al., 2009). While being such a difficult task it also serves as one of the most fundamental principles when it comes to accounting. Financial statements are presented under the premises that firms will sustain and remain an operating business (ISA 570 §2). Subsequently, information concerning an entity's risk of failing is crucial for external users of financial information to be able to make rational investments and credit decisions (Rodgers et al., 2009).

In 1909, Hatfield had published a work including the going concern assumption. Hatfield (1927) broadened his discussion of the assumption and had now identified going concern as generally accepted amongst practitioners. However, there was no definition explicitly put forward. What’s notably interesting about the findings by Hatfield is that there was no formal standard-setting at the time (Hahn, 2011). In 1968, Fremgen phrased a definition based on how going concern could be viewed in its most general statement, an assumption of a continuation of business without halt for the foreseen future. Arthur Andersen & Co. questioned the definition in a memorandum, addressing the premises of the definition as unfounded. Despite whichever agenda or goal this memorandum by Arthur Andersen & Co. (1960) tried to achieve, it still proposed a legit criticism towards the definition.

The discussion of an explicit going concern definition is an on-going debate.

Practitioners from both auditing and accounting have debated whether to include a more specific definition. This led to a proposition by FASB to include going concern in the Statement of Financial Accounting Standards in 2008. The proposition was welcomed and generally agreed upon; however, it was still confusing and unclear regarding the core elements (Hahn, 2011). Commenters suggested that FASB should include a definition as to provide clarity and thus remove the subjective reasoning and uncertainty. Yet, FASB chose not to include a definition, therefore leaving the concept undefined both in accounting and auditing standards (Hahn, 2011). This means that on one hand, the practitioners seem to generally accept the assumption and have a general understanding of it, but on the other hand the concept receives attention and criticism for the diverse use in practice, especially in financial difficult times (IFASS, 2020).

In the light of financial crises, it is not only media and the general public that has questioned the problematic auditing regarding going concern. Audit regulators and supervisory bodies have reported auditing of going concern to be one of the most problematic areas in the auditing process (Laudato, 2012). According to Laudato, this shortfall is probably due to a number of factors such as directors and auditors underestimating the importance of a relevant going concern requirement. This becomes problematic as it regards a matter capable of affecting business confidence (Laudato, 2012).

The going concern concept is surrounded by uncertainty both from practitioners and experts as well as the general public. These uncertainties become problematic as people do not know

one of the most fundamental premises in accounting and auditing, and despite this there is a substantial amount of doubt surrounding both the use and understanding of the concept.

1.2.2 Implications in practice

In the literature it has been proven that making a correct assessment is not that easy. It has become apparent especially in relation to corporate collapses and financial crises. In the beginning of the 21st century, scandals such as Enron occurred, who went bankrupt without any warning indicators from their auditors (Healy & Palepu, 2003). Auditing scandals has questioned the auditor’s ability to successfully assess the financial position of their clients. However, it is not only corporate scandals that have shed light on and questioned auditors' ability to foresee and warn about firms' financial performance before they collapse. During the financial crisis, questions were raised how the auditors failed to warn about the bank collapse which started the crisis (Humphrey et al., 2009). Based on this it has been argued by several parties that the assessment and disclosure in the audit reports concerning firms as going concerns has not been satisfactory, this has been particularly evident by entities having to file for bankruptcy not long after their financial statements based on the going concern assumption was issued (Laudato, 2012).

In order to understand what constitutes the going concern principle for an auditor it is important to acknowledge different external factors and incentives that may influence an auditor in their consideration process. This is where most of the literature on the topic have evolved. While there are numerous problems posed by a diverse conception in practice, there are risks associated as well. The risks associated with a faulty decision and the possible consequences must be fully understood.

What has been demonstrated is that when an auditor fails to issue a GCO to an entity which later has to declare for bankruptcy, type 2 error, the cost can be quite large for the auditing firm (Myers et al., 2014). Therefore, they might have incentives to a further extent to issue a GCO to a financially distressed firm to protect themself from these costs (Myers et al., 2014). However, making a type 1 error, that is issuing a GCO to a client that does not declare for bankruptcy is not insignificant (Myers et al., 2014). Following a type 1 error the client may choose to opt for a different auditor (Francis, 2004) hoping to receive a more favorable

assessing the problem of client dependence of audit firms and fear of losing clients it has been tested whether audit opinions regarding GCOs are influenced by economically important clients (Li, 2009). The results indicate in line with prior studies that in general economically important clients do not get a favorable treatment. Rather the study showed that in 2003 following the introduction of the Sarbanes-Oxley-Act, there was a positive association between client fees and GCOs indicating that auditors became more conservative in their reporting of larger clients to avoid litigation costs and protect their reputation in this sensitive period (Li, 2009). The Sarbanes-Oxley-Act of 2002 was put in place to force down corporate frauds and enhance the responsibility in the financial reporting (Law & Act, 2002).

In relation to what consequences might be tied to a GCO issued to a firm, the market’s reaction has been studied. It was found that market reactions to GCOs being issued to entities had little to no effect, the GCOs would merely be a confirmation of information already possessed by the market (Mutchler, 1985; Dopuch et al., 1987). On the other hand, Ruiz-Barbadillo et al. (2010) examined the impact of a qualified GCO to a company’s capital market value. They concluded that entities with GCOs tends to have a lower market value than firms without a GCO. How the auditor operates within the work of a going concern assessment plays an important role. Independence and objectivity are the most fundamental strengths and key assets possessed by auditors (Rodgers et al., 2009). The assumption of going concern is critical to the usefulness of decisions by external users based on financial information supported by the accrual basis of accounting (Hahn, 2011). Information concerning an entity's danger of failing is of great importance and examining GCOs is one way of obtaining this information (Rodgers et al., 2009).

Questions have also been raised whether requirements included in the financial reporting frameworks are sufficient for the going concern assessment (FASB, 2014). The evaluation of entities done by auditors therefore cannot be said to faithfully achieve a complete and correct picture, thus questioning its appliance in its present state. Following these uncertainty

concerns regarding the going concern concept, FASB introduced an update to managements disclosure requirements while simultaneously clarifying some of the confusion related to the interpretation of “substantial doubt” and “going concern” (FASB, 2014). Important to note here is that this clarification only deal with management's assessment of going concern, the auditing standards does not include a definition of substantial doubt nor direct auditors to

previously been evident is that the term “substantial doubt” about an entity's ability to continue to operate as a going concern has been problematic. In a survey by Ponemon and Raghunandan (1994), it was found that bankers and analysts linked substantial doubt with the highest likelihood of failure, while judges and jurisdictive colleagues associated it with the lowest probability of failure. Auditors ended up between the two other groups and what is evident is that users assign more weight to the concept, resulting in an expectation gap and uncertainty surrounding the concept.

The going concern concept is rather vague both in literature and standards. Uncertainty surrounding such a key concept is problematic and bears the risk of being reflected in auditor's professional judgements. Expanding these concerns, auditing is only valuable if it can provide credibility, which demands that it is consistent and can provide a fair and proper assessment of the reporting entity's financial statements (Geiger et al., 2005). However, even if the going concern judgement is considered a critical one, prior research suggest that

auditors do not always arrive at what in hindsight might be the correct audit opinion (Herbohn et al., 2007; Humphrey et al., 2009). One plausible explanation of the inconsistency in going concern reporting is the great deal of professional judgement required by auditing standards, leaving these judgements to be influenced by individual's information processing, which makes it a complex audit judgement (Geiger et al., 2005). Inconsistency in interpretations of auditing standards in relation to going concern, especially in relation to the term substantial doubt, have in previous research indicated that different auditors can arrive at different conclusions based on the same audit evidence (Shelton, 1999). Hossain et al. (2018) found evidence of gender providing different auditing outcomes, further proving that subjective and behavioral differences have potential to influence auditing outcomes.

As the current effects of the economic situations opposed by the COVID-19 pandemic are still to be examined, a deeper understanding of what constitutes the term going concern and how auditors evaluate the going concern controversy in practice are needed. This will contribute to the understanding of the treatment which in turns improves predictability and explain reasons and consequences of the diverse and difficult treatment of going concern.

1.2.3 Lack of studies in the literature

Even though the going concern concept fluctuates heavily in the literature, there is relatively little qualitative research surrounding the actual essence of the principle. In an extensive literature review of GCOs, Carson et al. (2013) identifies three major areas where prior literature has evolved: (1) determinants of GCOs, including client factors, auditor factors, relationship between client and auditor and other environmental factors. (2) the accuracy of GCOs and (3) consequences arising from GCOs. The aim for most studies has been focused on a cause-effect relationship regarding the GCOs issued for entities. While this provides important and insightful knowledge regarding the auditor’s decision-making process, it does not reflect upon what the auditor’s perception of a GCO is. There is still a lack of research about the assessment of the going concern concept and its fundamental core, which clearly can be witnessed by the lack of definitions.

We argue that there is one key factor contributing to the failure in practice when evaluating and issuing a GCO, the unclear and potentially misunderstood going concern concept. If the foundation, the going concern term, for which every other understanding and research done by is unclear, it is hard to believe that we actually fully understand the concept and know how to apply it properly to achieve what it is intended to do. To our best knowledge a

conceptualization and application of the going concern principle have not been studied in the field of auditing before. How auditors turn a concept in theory, going concern, into practice and what implications this might have is still an unsettled issue. This then poses numerous other problems, such as where the same entity evaluated by two different auditors would end up with two different results, or the problem of how to correctly interpret the results of research based on GCOs. Therefore, a fuzzy and unclear going concern concept is the least optimal outcome for all parties.

1.2.4 Why is this gap problematic?

The literature concerning GCO provides clear evidence of the importance and implications of the concept in practice (Mutchler, 1985; Lennartsson, 2020; Carson et al., 2013; Fremgen, 1968; Healy & Palepu, 2003). In our opinion it is therefore odd that the literature has left aspects of the consideration process and application in practice unexplored. We ask the question why this is?

On this fundamental question we can come up with two reasonable explanations. Either the task is too complicated to obtain reliable insightful information, or this additional information is considered not to provide any added value to the understanding of GCO. Although as we argue, a concept without a uniform conceptualization and little insight in the application process, is indeed problematic in a field where quality, predictability and independence are crucial elements.

If we do not know how auditors assess the going concern concept, the research examining GCOs becomes difficult to interpret. Majority of the literature do not discuss or touch upon what the going concern judgement actually entails. There is a considerable amount of research examining reasons and consequences of the GCO. Although if we lack the understanding of what constitutes a going concern assessment, we might not be able to gain full benefit of the research surrounding the subject. Furthermore, or perhaps the most problematic aspect of this uncertainty is that auditing risks failing on one of its core statements. The core mission of auditing is to evaluate financial statements and make sure they are presented correct and fair and within this the going concern assumption constitutes a key concept. If we put it on the edge, missing how auditors conceptualize and apply this principle bear the risk of casting doubt on the entire auditing profession and one could question how reliable audited financial information really is.

1.2.5 The necessity for research

This paper aims at broadening the perspective of auditor's consideration process and treatment of the going concern principle by opening up the black box of the individuals responsible for the critical decision to issue a GCO or not. We have narrowed down the going concern assessment into two different themes, conceptualization & process, which we will consider throughout the report. Looking further into how individuals assign different weight to unclear and subjective phrasing in standards and how this can lead to an inconsistent perception in practice. The going concern concept is widely used in the literature as a valuation tool of audit quality and auditor’s ability to make correct assessments (Bills et al., 2015; Hardies et al., 2016). The auditing standards contains relatively little information concerning how theory should be interpreted, exposing the concept to subjective treatment. While subjectivity might not be bad per se, it sure raises doubt about a diverse treatment in practice. On top of this, the

auditing standards is generalizing which results in a lack of compassion for the size of companies.

We argue that since the going concern assumption seem to lack a uniform understanding and is heavily based on the auditor’s individual subjectivity. This does not only create issues for users of financial information, it also poses difficulties surrounding comparison and

understanding of the literature regarding going concern. When standards leave room for professional judgement, there is a great risk of fluctuations in the judgement process in practice. If we do not fully understand what constitutes a going concern assessment, how should we then be able to trust and interpret the research regarding the concept? Starting from uncertainties surrounding vague phrasing in the standards, we want to assess if auditors assign different weight to key elements of the going concern principle. Based on this the purpose of our study is to look at how auditors interpret the theoretical auditing premises when assessing the going concern concept in practice.

1.3 Research purpose

The purpose of our study is to enhance the understanding of the auditor’s Going Concern assessment by looking into their application and treatment of the concept in practice. This will provide a more complete nuanced picture of auditor’s conceptualization and their process of evaluating going concern.

2. Literature review

This chapter intends to provide the reader with a walkthrough of previous research,

standards, and regulations in the GCO field to get a deeper understanding of what previous literature have covered. The literature review includes a theoretical model, background to the going concern acceptance, standards & regulations, process, and factors influencing

auditor’s judgement. Finally, we will present our conceptualization model.

2.1 Theoretical model

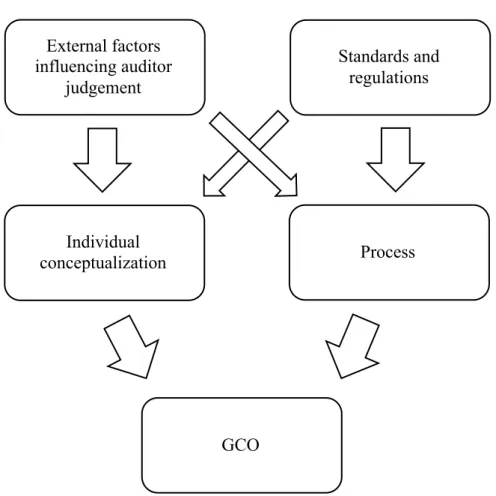

Based on our understanding of the GCO we have chosen to divide the literature review into two main sections. 1) Standards and regulations and 2) External factors influencing auditor judgement. The first section will include an overview of existing standards as well as the evolvement of standards and how these have impacted the GCO. The second section will have a focus on the main topics where research have concentrated regarding factors that seem to influence auditor’s judgement of the GCO. The later section will provide the reader a

comprehensive understanding of the problem simultaneously providing relevant information helpful for analyzing the empirical results. To help the reader follow our logic, we have illustrated a model describing our understanding and the structure of the literature. This model is presented below.

Figure 1: Theoretical model

2.2 Definition av going concern

The definition of going concern in its most general statement is an assumption of a continuation of business without halt for the foreseen future. Fremgen (1968, s.650) then phrases the definition, ‘’In the absence of evidence to the contrary, the entity is viewed as remaining in operation indefinitely’’. By this perspective, the ideal standpoint would be to view the going concern concept as abstract with an infinite time horizon. The definition is in various ways a contrary to the once historically popular business enterprise, single venture, which was originally constructed to affect a single and commonly large transaction. A going concern on the other hand is a design for a business which affects an unlimited sequence of transactions. The business is characterized as going concern for as long as the business is successful. Further it is stated that even the writers who used the assumption would find its limitations, and most agreed upon that it is not scientifically grounded. (Fremgen, 1968)

External factors influencing auditor judgement Standards and regulations Individual conceptualization GCO Process

There are numerous implications of a continuity assumption. Most often the discussions would observe the entity as a continuous operation in the foreseeable future that would not be liquidated. Fremgen (1968, s.650) would further imply and frame it as a ‘’sterile postulate at best’’ and invalid when considering all small new businesses which are most often to fail within a year. An alternate definition is formulated, ‘’the entity is viewed as remaining in operation indefinitely, in recognition of evidence to that effect’’ (Fremgen, 1968 s.650). Thus, this would include room for judgement based on the evidence there is in the individual case. Following this, a conclusion rather than an assumption would be the case of continuity. If the accountant to their best determination would seek evidence of the contrary, but no evidence was to be found, then the result would rather be a conclusion than an assumption. If the person determining going concern already were convinced of a going concern assumption without seeking evidence of contrary, then the assumption of continuity would be

meaningless, and all results would be unsignificant. If correct accounting depends on an unspoken compliance of a going concern, it could lead to incorrect financial statements with severe consequences. (Fremgen, 1968)

In 2008, FASB decided not to include a definition in the exposure draft, nor the finalized standard. Therefore, a going concern would be determined instead by the types of information required as part of management’s assessment, the time horizon for which the assessment is to be made, and disclosure requirements (Hahn, 2011). Notably the time horizon is one of few factors where differences exist between FASB and IASB, the two main accounting bodies issuing accounting guidelines. FASB is the financial accounting standards board publishing the general accepted accounting principle (GAAP). IASB is the international accounting standards board publishing international financial reporting standards (IFRS). According to FASB, the time horizon for the going concern assessment is generally considered to be made for a period not exceeding 12 months. IFRS on the other hand say that the assessment should be performed for a period of at least 12 months, where the period can be extended depending on decisive factors and circumstances occurring after 12 months. While differences exist in what regulators think should be considered a sufficient time period, what route is taken will have effect on the final product. At one hand, the market might desire a longer time frame for going concern to make long term investments. On the other hand, longer timeframes will require more speculative judgements of the future, where auditors are no better than anyone else to predict (Bellovary et al., 2006).

2.3 Standards and regulations

The regulatory process like many other regulatory frameworks consist of five general components: the setting of standards, their adoption, the implementation in practice, monitoring concerning compliance, and application procedures (Humphrey & Loft, 2012). The main objective of the regulation concerns the matter of ensuring that auditors follow best practice codes when conducting the audit, which is essential for auditor’s capability of detecting significant errors and report them faithfully.

The auditors working process involves judgement and opinions based on collected audit evidence. Evidence is typically obtained from financial statements, observations and

communication with the client. Based on this the auditor’s opinion can be either modified or unmodified, where the later implies compliance with standards and regulations and the former indicating a concern (ISA 705 §6). The modified opinion can be either qualified, adverse or a disclaimer. The qualified opinion entails material misstatements are found, although not pervasive, this is the less serious of the modified opinions (ISA 705 §7). An adverse opinion is where the auditor finds misstatements that are important for, and may impact a readers decision based on financial numbers (ISA 705 §8). Disclaimer of opinion is a somewhat different opinion; it’s issued when the auditor is unable to obtain sufficient evidence due to the client refusing to provide information and this information may be both material and pervasive (ISA 705 §9).

2.3.1 Audit regulation, ISA 570

The international auditing standard dealing with the auditor's responsibilities when reviewing a firm's financial statements in relation to going concern is ISA 570. According to ISA 570 going concern is the basis for the firm's accounting and implies that financial statements are prepared under the assumption that the firm will continue their operations as normal and be able to realize its assets and meet their obligations in the foreseeable future. The going concern principle serves as an underlying basic principle for management when preparing financial statements with exception if management intends to or does not have any other choice than to liquidate the entity. There are differences in financial frameworks, some require management to make a particular assessment regarding the entity's ability to continue to operate as a going concern. Other financial reporting frameworks may not explicitly require a specific assessment of the entity's going concern ability, although as mentioned above the

going concern assumption is a fundamental principle when it comes to preparing financial statements. Therefore, management is required to assess the going concern ability of the entity even if there is no explicit requirement included in the financial reporting framework to do so (ISA 570 §4).

2.3.2 Risk assessment methods and related practices

ISA 570 provides a list of events or conditions for practitioners to assist and guide their assessment of an entity. These are divided into three sub-categories, financial, operating & other. However, despite some events/conditions fulfilled, there are exceptions. A further explanation is to be found within ISA 570, which states that these events or conditions often can be mitigated by other factors which too play an important role. As a result, the auditor’s own perception and judgement is still required and needed to reach a result. The following listed events or conditions might individually or collectively sum up to significant doubt about an entity’s ability to continue as a going concern (ISA 570 A 3).

“Financial

- Net liability or net current liability position.

- Fixed-term borrowings approaching maturity without realistic prospects of renewal or repayment; or excessive reliance on short-term borrowings to finance long-term assets.

- Indications of withdrawal of financial support by creditors.

- Negative operating cash flows indicated by historical or prospective financial statements.

- Adverse key financial ratios.

- Substantial operating losses or significant deterioration in the value of assets used to generate cash flows.

- Arrears or discontinuance of dividends.

- Inability to pay creditors on due dates.

- Inability to comply with the terms of loan agreements.

- Change from credit to cash-on-delivery transactions with suppliers.

- Inability to obtain financing for essential new product development or other essential investments.

Operating

- Management intentions to liquidate the entity or to cease operations. - Loss of key management without replacement.

- Loss of a major market, key customer(s), franchise, license, or principal supplier(s).

- Labor difficulties.

- Shortages of important supplies.

- Emergence of a highly successful competitor.

Other

- Non-compliance with capital or other statutory or regulatory requirements, such as solvency or liquidity requirements for financial institutions.

- Pending legal or regulatory proceedings against the entity that may, if successful, result in claims that the entity is unlikely to be able to satisfy.

- Changes in law or regulation or government policy expected to adversely affect the entity.

- Uninsured or underinsured catastrophes when they occur.” (ISA 570 A 3)

To summarize, ISA 570 is the international auditing regulatory framework, for going concern assessments and provides guidelines for the auditors in their work-process. Basically, the firm generally construct financial statements on a going concern basis. However, what this implies is dependent on the assessment, which according to ISA 570 is not applicable in all cases. The mentioned list above of events/scenarios may or may not be fulfilled to sustain the argument that the firm is indeed a going concern.

2.3.3 Financial accounting regulation

Auditing standards do not contain an explicit definition of going concern, therefore auditors find themselves seeking guidance in accounting standards since the accounting standards contain more precise information (Hjalmarsson & Malmström, 2017). Historically, there was no need for managers to assess whether the entity was a going concern or not (Seyam & Brickman, 2016).Then it was solely the auditors who were required to evaluate if there is substantial doubt about the entity's ability to continue as a going concern, however there was no coherent definition of the term substantial doubt. Auditors are supposed to use their

professional judgement on this theoretical matter. When auditors use subjective judgement, it leaves room for interpretations which make it possible for different auditors to draw different conclusions based on the same underlying facts (Haron et al., 2009). This can potentially result in a lack of comparability between entities. These issues together with the gap that often occurred between auditors and management, where management disagreed with the auditor's professional judgement on substantial doubt about the entity's ability to continue operate as a going concern, led to the introduction of new requirements by FASB (Seyam & Brickman, 2016).

In 2008, questions were raised to provide guidelines in this area which led to an exposure draft. An exposure draft is a document with proposed changes to accounting standards released by the FASB to receive public comments and suggestions for improvement (FASB, n.d.). The draft received criticism as the terms “going concern” and “substantial doubt” were not clearly defined. Following this criticism, the board defined going concern as early warning disclosure about the entity's uncertainties (Seyam & Brickman, 2016). Regarding substantial doubt the board considered some alternatives although ended up with a high threshold. Formulated as defined to exist when conditions and events indicate that it is probable, with emphasis on probable that the entity will be unable to meet their obligations and become due within one year after the financial statements are issued (FASB, 2014). However, what conditions that should constitutes substantial doubt was a controversial issue.

To reduce uncertainty about the threshold gap between users of financial reports and

managers FASB provided some examples of circumstances where substantial doubt about the entity to continue to operate as a going concern might exist (Seyam & Brickman, 2016). These circumstances included repeated operating losses, working capital shortcomings, troublesome key financial ratios, and negative cash flows from operating activities (Seyam & Brickman, 2016). Other indications include default on loans, noncompliance with legal requirements and inability to finance activities due to bad credit. The evaluation of going concern includes a variety of methods to be used. According to Seyam and Brickman (2016) some of these methods include analyzing key financial ratios, reviewing board and committee meetings, how the entity complies with debt agreements, evaluating reasons for raising capital and borrowing and reducing dividends. These evaluations should then result in a professional judgement if there is substantial doubt about the entity's ability to continue as a going

concern. To clarify for the reader, these changes imposed by the FASB was only to accounting standards and left clarifications of auditing standards unchanged.

If we look at how the implementation of the new requirements included in the update of the GCO affected the responsibilities of the going concern evaluation. Our interpretation is that the auditor who previously had all the responsibility regarding the evaluation of this difficult process is now more shared between management and the auditor. The prior could be

considered a more formal understanding of the responsibilities. The introduction of new requirements relating to going concern is argued by professionals to provide a more coherent understanding of the topic which will help management, auditors, and financial information users (Seyam & Brickman, 2016). This more nuanced picture of the responsibility can be interpreted as a more conceivable understanding, where auditors and management in a collective effort deliver a correct and fair view of the entity as a going concern.

The auditing regulation contains several guidelines where the phrasing can be considered relatively vague. In addition to going concern, materiality is a concept surrounded by similar uncertainty. Materiality is a common phrase in accounting and is associated with the

minimum amount of exclusion or lack of information that would affect the judgement of a regular financial statement user (Ryu & Roh, 2007). In the auditing process, materiality constitutes a significant role since it is the auditor's responsibility to ensure that the financial statements are not materially misstated. Even with substantial research and the importance of the concept materiality, the current standpoint of the FASB is that “no general standards of materiality could be formulated to take into account all the considerations that enter into judgments made by an experienced, reasonable provider of financial information” (FASB, 2018).

The materiality concept is incorporated into the going concern assessment where a lot of responsibility is put on the auditor's professional judgement. Material uncertainties could be that of asset realization, contingent liabilities, or that of substantial doubt about the entity’s ability to continue as a going concern (Butler et al., 2004). Material uncertainty concerns is related to future economically relevant unknowns, which also could involve litigation risks and business uncertainties (Chen et al., 2016). Going concern is a topic currently under consideration by the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB). A

the requirements in auditing standards are sufficiently aligned with those in accounting standards has been open for consultation in beginning of 2021 (IFRS, 2021). This proves the relevance of the going concern concept and the desire by standard setters to achieve a more coherent treatment in practice.

This section takes both American and European frameworks into consideration. While the two frameworks acknowledge the same topics, there are some distinguishing differences such as the time-horizon factor. It is important to acknowledge that they are in many circumstances similar, although as Bogle (2020) argue the US GAAP is more developed and can provide additional guidance for IFRS standards preparers.

2.3.4 Implications of terms in standards

The above mentioned have incorporated both auditing and accounting standards. The focus of the following sections will now focus solely on auditing standards.

Daugherty et al. (2016) have examined differences in the interpretation of the terms used in auditing and financial reporting standards in the US compared to international standards. Looking at auditors in practice they find that the term “substantial doubt” under AU 341 averaged a threshold presumption of failure of 67% to assess a GCO. Comparing this to ISA 570 using the term “significant doubt” this was reported to average a threshold presumption of failure of 60%. Similarly, they find that differences in the reporting time frame influence the likelihood of issuing a GCO. Under AU 341 the time frame is phrased as “not to exceed a year” while ISA 570 use “foreseeable future” (Daugherty et al., 2016). These findings

highlight that subtle differences in the wording in auditing standards can have a significant impact on the auditor's professional judgement. The term “substantial doubt” has previously been questionable not only within the auditing profession. Ponemon and Raghunandan (1994) examined auditors, judges and banker’s perception of the term and found differences in the assigned weight to the concept. Judges associated it with the lowest prospect of failure (33%) whilst bankers linked it to the highest likelihood of failure (71%). Auditors understanding of the concept ended up in between the other groups (56%) giving rise to expectation gaps and uncertainty. Ponemon and Raghunandan (1994) argue that since the auditor should evaluate the audit report to conform by going concern and look for substantial doubt of the opposite, the process of determining substantial doubt might be one of the most crucial. Considering the importance of the term standard setters have still been reluctant to assign a precise meaning or

value to the expression. Boritz (1991) suggest that one reason might be that a precise value would expose audit firms to increased litigation. Assessing this problem Boritz (1991), in the book ‘’The “Going Concern” Assumption: Accounting and Auditing Implications’’,

developed a figure plotting out probability expressions frequently used in accounting and auditing on 100-point numerical scale.

From our understanding there seem to fluctuate differences regarding how strict the term “substantial doubt” should be interpreted. Furthermore, different standards have chosen different phrasings, where some refer to “substantial doubt”, others use the term “significant doubt”. A formal understanding of the concept would be to conceptualize it as a likelihood of between 50-70%, while a more conceivable perception would be a likelihood of failure between 20-50%. In an abstract view, doubt about an entity’s ability to continue in an unpredictable future will always be very high, whereby any confidence of the view can be questioned to exist at all.

2.3.5 GCO in relation to regulatory changes

Standards and regulations are put in place to guide and clarify auditors’ responsibilities, and while these responsibilities have remained quite stable, standards have progressed over time to clarify and update the reporting language regarding auditors’ obligations (Gissel et al., 2010). Majority of the literature regarding GCOs and regulations are comparative studies looking at a cause-and-effect relationship related to the accuracy of the assessment before and after introduction of new standards and guidelines. As an example, Holder-Webb and Wilkins (2000) examine the stock market's reaction to going concern announcements before and after the introduction of SAS No.59 and find that the market reaction on bankruptcy

announcements reflected in share prices is less negative under SAS No.59 than prior reports under previous requirements. SAS No.59 was an expansion of regulations regarding required reporting of going concern, specifically obligating auditors to evaluate and report on a client’s going concern status (AICPA, 1988). They also report that there is a greater difference

between a going concern bankruptcy surprise and a clean opinion bankruptcy surprise under SAS No. 59 than under previous requirements. Evidence is found to support that investors have benefited from the increased responsibility and requirements imposed on auditors by SAS No. 59 (Holder-Webb & Wilkins, 2000).

Since the introduction of SAS No. 59, several clarifications have been introduced to provide additional guidance in the issuing of going concern (Gissel et al., 2010). In 1990, a clarifying paragraph was introduced, requiring the auditor to include the terms “substantial doubt” and “going concern” when issuing a GCO (AICPA, 1990, as cited in Gissel et al., 2010). The auditor would therefore have to interpret the concepts, which Boritz (1991) clarified to be imposing a high degree of doubt. Later clarifications include spelling out that auditors are not required to reissue an opinion if the client resolves the uncertainties, although if a GCO is reissued as an unmodified opinion, the auditor is required to perform certain procedures (Gissel et al., 2010). Although, clarifications seem to have influenced the uncertainty

surrounding the subject in a positive way. There are still professionals calling for regulators to improve the clarification and specifications regarding going concern as there is a diverse application of the concept in practice (IFASS, 2020).

Examining auditor's behavior immediately after the introduction of new regulations or a major event such as a financial crisis, is interesting and necessary to evaluate the effectiveness and impact. It is however questionable if conclusions based on short term results are reliable. In 2003, subsequent to the introduction of SOX (2002) which was introduced as a response to the Enron scandal, Li (2009) found that audit fees are positively related with the auditor's tendency to issue a GCO. These results can suggest that the introduction of new standards changed auditors' assessment of the GCO. However, Kao et al. (2014) have recreated Li’s (2009) study extending the post-SOX period to 2011. Their results confirm Li’s results for 2001 and 2003, though what is more interesting is they find no significant coalition between GCO decisions and audit fee dependence for the successive years 2004-2011. Analyzing these results indicate that 2003 was not a normal reporting year in the U.S, where the audit

profession was in the spotlight of regulators influencing how auditors dealt with economically important clients (Geiger et al., 2019). These findings by Kao et al. (2014) highlight that regulatory changes need to be assessed under an extended period. Correspondingly Carey et al. (2012) examined type 1 going concern reporting errors for Australian auditors comparing 1995-1996 to 2004-2005. They find that reporting errors are similar for the two time periods suggesting differences in going concern decisions due to the expanded regulatory

environment subsequent to the corporate collapses 2001 were rather temporary. Together these studies suggest regulatory changes to be examined over an extended period of time. These findings contribute to the understanding of how regulatory changes affect auditor's judgement in relation to the GCO. Additionally, it addresses the issue and calls for caution of

reaching conclusions too soon. What can be argued based on this is that subtle changes to the regulatory environment only have short term effects which can diminish in the long run. This however is contrary to what has previously been mentioned that minor differences in the regulatory phrasing can have significant impact on auditor's professional judgement (Daugherty et al., 2016).

Summarizing standards and regulations, the section has provided a basic understanding of what the regulation regarding auditors going concern assessment looks like. Auditors should evaluate management appropriateness of the use of the principle by collecting evidence that may cast doubt of the firms’ future operations. Implications of key terms in the concept’s assessment, lacking a clear understanding and definition has been discussed. It has also been put forward how regulatory changes and clarifications have impacted the auditing of going concern. Below, the process will be touched upon where it has been described as a two-step process, first identifying financial distress, and secondly evaluating if a GCO is justified.

2.4 Process

Based on prior literature, it has been evident that auditors are able to point out economically troubled companies. Despite this fact, the auditors may choose not to issue a GCO (Kida, 1980); Mckeown et al.,1991; Krishnan & Krishnan 1996). Ruiz-barbadillo et al. (2004) discuss that the GCO is a two-stage process. The first step is identifying factors in a company that bears the potential of a going concern issue. This identification is dependent on two factors: financial distress and the auditor’s ability to detect the same, in other words the auditor’s competence. The second step involves determining whether or not the company with a going concern issue is eligible for an audit report with a GCO. According to Ruiz-barbadillo et al. (2004), this decision will be dependent on the auditor’s independence, which reflects the economic consequences and effects that follows.

A long-lasting argument as a consequence following a GCO is the “self-fulfilling prophecy’’. It entails that the GCO itself creates a negative chain reaction, causing the already distressed company to fail (Geiger et al., 2019). In a relatively recent examination by Gerakos et al. (2016) this problem is addressed, where it was identified that a financially distressed firm receiving a GCO, increases the probability of the firm having to file for bankruptcy. However, only by such a small amount that auditors should not be concerned with the prospect that a

GCO will send the company into bankruptcy. Moreover, earlier work by Amin et al. (2014) examined US companies and the increased cost of GCOs in terms of increased cost of equity financing. They found that an issued GCO significantly increased the company's cost of equity capital. These results are important to acknowledge as they indicate that there in some circumstances might be incentives for auditors to not issue a GCO if the auditor believe that it will put the client in worse position.

2.5 Factors influencing auditor's judgement of GCO

The literature regarding going concern is mainly focused on cause-and-effect relationships providing little insight in how the actual conceptualization are done in practice. While external factors are a significant element, we believe that understanding the effects of the GCO as well as conditions that may influence auditors in different directions in their

judgement process, is important to get a full understanding of the problem. These factors will also serve important in analyzing the empirical data gathered through the interviews. Based on this, it is possible to analyze potential differences for example gender, experience, or firm. Factors influencing GCOs have been fluctuating in previous literature (Hardies et al., 2016; Hossain et al., 2018; Sundgren and Svanström, 2014). Recent literature reviews (Carson et al., 2013; Geiger et al., 2019) have summarized the most reoccurring and highly influential factors. Out of these, the ones best suited for the purpose of this study will be presented below.

2.5.1 Auditor judgement

In the past, there have not been much experimental studies done in the field, or more

specifically, addressing GCO decisions and the judgement processes involved (Geiger et al., 2019). However, during the recent years of research in the field there have been an increase in such studies. The study by Lambert and Peytcheva (2017) was an experimental study which found evidence, or a tendency, that auditors are prone to make an average assessment of the evidence when performing a GCO assessment. This is the tendency for auditors to, despite a single strong negative evidence, assess jointly all evidence there is and appraise an average result from this. Thus, a strong negative evidence towards an GCO may be mixed or balanced with less negative evidence, or even positive evidence, which results in a more positive GCO evaluation than if one were to assess each evidence secluded (Geiger et al., 2019). This in itself becomes problematic, since the evaluation of solid negative evidence on its own would

lead to a GCO decision but mixed with other less negative evidence would decrease the chance of a GCO being issued (Lambert & Peytcheva, 2017). The issue becomes very much apparent when assessing the work process, which in most cases means that in the end of an audit the auditor summarizes the collected evidence. All evidence is then assessed and judged simultaneously, which furthermore proves the problematic situation. The results point towards a less than excellent GCO decision, than otherwise would be if one would assess the evidence as individual fragments (Lambert & Peytcheva, 2017).

Another important variable when assessing the quality of a GCO decision is the type of work done in the judgement process and review of evidence at hand. Duh et al. (2018) finds that this is the case. In an experiment, auditors were monitored in their GCO decision processes. The face-to-face format group in their review outperformed the other groups in evaluating the company at hand. The face-to-face also had, in general, a higher quality in their workpapers. The other group participating in the study was an e-mail review format group which were not performing to the same extent as the face-to-face format group and therefore resulted in poorer results and a less sufficient GCO decision. (Duh et al., 2018)

2.5.2 Audit firm size

In the aftermath of the tumbling events following 2001, Myers et al., (2014) found that amongst the non-big 4 auditors in US, there was a reduction in type 2 errors. However, this was a trade-off since it came at the expense of an increase in type 1 errors. Comparable are the results from the big 4 auditors where there was a decrease in type 1 errors without the corresponding increase in type 2 errors. In contrast to the findings of Myers et al., Foster and Shastri (2016) found no significant differences between big 4 auditors and non-big 4 auditors in their GCO decisions. Noteworthy is that the study was conducted amongst start-ups and enterprises in the development stage. In contrary, a meta study done by Habib (2013) on the determinants of GCOs finds that, in general, big 4 auditors are more likely to issue GCOs than non-big 4 auditors.

The financial crisis hit globally in 2007-2008 and most of the world felt the effects of it. In Australia, the effects of the crisis on GCO reporting were examined by Fargher et al. (2013). Findings suggest that while overall GCO rates increased during the period of the financial crisis 2007-2008, big 4 auditors in Australia had responded faster to the crisis than non-big 4 auditors. The big 4 auditors had increased their GCO rates earlier than non-big 4 auditors,

thus indicating a faster response time. Carson et al. (2016) documented the historical trend in Australia between 2005-2013 of big 4 auditors. In general, big 4 audit firms issued less GCOs than non-big 4 audit firms. In a different study done by Ratzinger-Sakel (2013), evidence is found that supports these findings that big 4 auditors are less likely than non-big 4 auditors to issue an GCO.

In a thorough study by Berglund et al. (2018), client financial stress is better controlled for than previous studies, that uncover findings which argues that big 4 auditors in the U.S issues more GCOs and have less type 1 errors than non-big 4 auditors. Furthermore, it is found that there are no differences in type 2 errors between big 4 auditors and non-big 4 auditors. Harris et al. (2015) conducted one out of the few studies done on consecutive GCOs. The outcome from their investigation of consecutive GCOs finds that big 4 audit firms issue less

consecutive GCOs, while non-big 4 audit firms issue GCOs at a greater rate. This follows previous findings done which suggests that big 4 auditors are less likely to issue GCOs than non-big 4 auditors.

Foster and Shastri (2016) found no significant difference between big 4 auditors and non-big 4 auditors in their GCO decisions. At contrary, Habib (2013) concludes that in general big 4 audit firms are more likely to issue GCOs than non-big 4 audit firms. On the other hand, Carson et al. (2016) finds evidence that big 4 auditors issue less GCOs than non-big 4

auditors. This is further supported by Ratzinger-Sakel (2013); Harris et al. (2015). Uncoherent and disagreeing findings of the three views exists, which at this point in time leaves the issue unsettled.

2.5.3 Industry specialization

In relation to accuracy and going concern reporting several earlier studies have examined whether industry specialization within audit firms have any impact on the decision to issue a GCO. There might be several reasons why audit firms may seek to specialize in certain industries, one is to enhance audit quality (Bills et al., 2015). What Bills et al. (2015) find when evaluating whether industry specialized audit firms have better audit quality is that industry specialists are more likely to issue a GCO furthermore specialists in homogeneous and complex industries seem to report similar results relative to specialists in other industries. In contrast to this Minutti-Meza (2013) find that there is no significant difference in GCOs between industry specialists and non-industry specialists. Furthermore, he problematizes prior

studies using within market share proxy as a measurement of specialization and expertise (Minutti-Meza, 2013). However, although the above-mentioned approach to control for industry specialization can be criticized, Sundgren and Svanström (2014) used this categorization and found similar results, indicating that industry specialization does not impact the decision to issue a GCO. In the light of these inconclusive quantitative studies, there seems to be confusion whether individual differences exist between industry specialized audit firms and non-specialized. In our perception this opens up the question if there are other differences in auditor's judgement affecting the GCO.

2.5.4 Litigation and financial risk-factors

From an auditor's perspective, litigation cost and loss of reputation has been evident in prior literature to influence the decision to issue a GCO or not (Geiger et al., 2019). Understanding the key risks an auditor may face when making a faulty assessment is important as it may influence the auditor's judgement. Litigation is arguably one of the most popular risks to be examined in the literature. There are several studies that have examined the impact of the introduction of SOX. Auditors became more prone to issue GCOs subsequently to the introduction of SOX (Geiger et al., 2005; Nogler 2007). Although Feldman and Read (2010) revisit this issue and found that the increase in going concern rates diminish in subsequent years and return to their initial level of the pre-SOX era. Later studies in the U.S have examined differences in liability across states. Anantharaman et al. (2016) find that auditors in a state with high legal liability are more likely to issue a GCO to a client than auditors in low legal liability states. Similarly, Cao et al. (2019) find that in industries with audit firm litigation, auditors are more likely to issue GCOs. Their findings support the argument that auditor litigation promotes lower misstatements rather than higher. This stream of research seems to be relatively consistent, recognizing an increase in the auditor's litigation exposure to generate an increased tendency to issue a GCO.

In relation to litigation risks, prior studies have tried to identify if the organizational form of the audit firm has any influence on the decision to issue a GCO. Similar to litigation risk this stream of research seeks to find if higher economic risks imposed to the audit firm influences their judgement. Firth et al. (2012) use a sample of Chinese audit firms to compare audit reporting procedures between audit firms formed as unlimited liability partnerships, and audit firms established as limited liability corporations. Their results provide evidence that auditors