Exploring Nonverbal Interaction

in Face-To-Face and

Computer-Mediated Communication

Jonas Drewling

jonas.drewling@gmail.com Interaction Design Bachelor 22.5HP Spring 2020Abstract

This thesis aims to contribute to the field of interaction design by exploring the use of nonverbal cues in FTF communication with the aim of generating knowledge that can be used as an alternative approach for assessing and designing text-based CMC media.

To achieve this goal, movement in is analysed in the nonverbal and collaborative dimensions of FTF communication. This presents the possibility to assess text-based CMC media based on a better understanding of the use of nonverbal cues and FTF communication as a standard.

The assessment and design based on this concept is tested in the design phase.

This process provides a platform for discussion and evaluation of an alternative approach for designing text-based CMC media with a focus on interaction between communicators.

Keywords:

Nonverbal Interaction, Nonverbal Cues, Computer-Mediated Communication, Face-To-Face Communication

Table of Contents

Contents

Table of Contents ... 3 1 Introduction ... 4 1.1 Context ... 4 1.2 Aim ... 51.3 Structure of the Thesis ... 5

1.4 Research Questions ... 6

2 Methodology... 6

2.1 User-Centred Design Process ... 6

2.2 Interviewing ... 7

2.3 Focus Groups ... 8

2.4 Affinity Diagramming... 8

2.5 Story Completion ... 8

2.6 User Interaction Diagrams (UIDs) ... 9

2.7 Prototyping ... 9

2.8 Laban Movement Analysis ... 10

3 Background ... 13

3.1 The Cues-Filtered-Out Approach ... 13

3.1.1 The Lack of Social Context Cues Hypothesis ... 13

3.1.2 Social Presence Theory ... 14

3.1.3 Media Richness Theory ... 14

3.2 Newer Theories ... 14

3.2.1 Social Information Processing Theory ... 14

3.2.2 The Hyperpersonal Model ... 15

3.2.3 Media Naturalness Theory ... 16

3.3 Related Work ... 17

3.3.1 Digital Body Language ... 17

3.3.2 Nonverbal Cues and FTF Communication ... 18

3.3.3 Nonverbal Communication in Service Encounters ... 20

3.4 Summary and Way Forward ... 21

3.5 Participants ... 22

4 Research Phase ... 23

4.1.1 Field Interviews ... 23

4.1.2 Online interviews ... 24

4.1.3 Summary and the Way Forward ... 25

5 Exploration Phase ... 25 5.1 Affinity Diagrams ... 26 5.2 Story completion ... 28 5.3 Nonverbal UID 1 ... 29 5.4 Video Analyses ... 30 5.5 Nonverbal UID 2 ... 35

5.5.1 Summary and Way Forward ... 35

6 Design Phase ... 36

6.1 Ideation Session One ... 36

6.2 Text-based CMC ... 36

6.3 Ideation Session 2... 38

6.4 Live Feed Messaging ... 38

6.5 Eye Contact in Video-Based CMC ... 40

6.6 Face and Eye Isolation ... 43

7 Discussion ... 44

8 Conclusion ... 49

9 References ... 50

1 Introduction

1.1 Context

Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC) is a broad term that encompasses both text-based media such as email or chat apps, and video-based media like Zoom or Skype. CMC is hugely accessible today given the technical capabilities of technology and integration into our lives. Communicating via technology is more effective than ever, with more possibilities for interacting and socializing with one another.

The foundational theories surrounding CMC present a dilemma. The cues-filtered-out (CFO) approach argues that CMC media differs in its ability to

convey various forms of information, both nonverbal and verbal, resulting in fewer social cues and thus less social context. The overall hypothesis of the CFO approach goes as far as to suggest that CMC is only good for the exchange of impersonal or task-oriented information and in no way capable of conveying the same level of meaningful and personal exchanges as face to face (FTF) communication.

My personal bias toward CMC media tended to somewhat agree with the CFO approach until I became aware of the newer theories that challenge that bias. Social information processing theory (SIPT) supports some of the concepts presented by the CFO approach. For one, it agrees that CMC is often limited in the ability to convey social cues. Furthermore, it explains that these cues are linked to emotions and meaning, with their absence having an impact on communication. However, that might not always be negative, but instead different.

Within the divergent views concerning CMC related to theoretical research (Walther, 1992) presented a research gap that existed in the field of communication. He raised concerns with much of the research regarding the perspective of the CFO approach. Claims made regarding both FTF communication and CMC were not as credible as they might seem, due to the lack of understanding regarding the use of nonverbal cues. This research gap presented an opportunity for the field of interaction design, by analysing movement, interaction, and collaboration in FTF communication.

1.2 Aim

This thesis aims to contribute to the field of interaction design by exploring the use of nonverbal cues in FTF communication with the aim of generating knowledge that can be used as an alternative approach for assessing and designing text-based CMC media.

To achieve this goal, movement in is analysed in the nonverbal and collaborative dimensions of FTF communication. This presents the possibility to assess text-based CMC media based on a better understanding of the use of nonverbal cues and FTF communication as a standard.

The assessment and design based on this concept is tested in the design phase.

This process provides a platform for discussion and evaluation of an alternative approach for designing text-based CMC media with a focus on interaction between communicators.

1.3 Structure of the Thesis

The theoretical research presented an open-ended design opportunity. As such the initial research question was formulated in a manner that invited open-ended exploration of the design opportunity. Throughout the research

phase the initial research question began to take on additional meaning which prompted the formulation of two additional research question to help with the investigation.

The thesis consists of the following sections:

Section 2 explains the methods that were used in the design process. Section 3 elaborates on the theoretical background research.

Section 4 marks the beginning of the design process and describes the research phase. This section also explains the framing of the additional research questions.

Section 5 describes the exploration phase.

Section 6 describes the design phase and concludes the design process. Section 7 focuses on the discussion and reflection of the design process and the findings.

Section 8 concludes the thesis.

1.4 Research Questions

How are nonverbal cues used in face-to-face communication and how might they be used in the design of computer-mediated communication?

Additional research questions:

1) How are nonverbal cues used interactively in FTF communication? 2) How might we assess, and design text-based CMC media based on a

better understanding of FTF nonverbal interaction?

2 Methodology

This section describes the most important methodology regarding this thesis.

2.1 User-Centred Design Process

A user-centred design (UCD) process, at its core is iterative and inclusive. In UCD we as designers are focused on the thing that is being designed, whilst trying to ensure that it meets the user’s requirements and needs (Sanders, 2002). Sanders explains that in the case of UCD, the researcher serves as a sort of interface between the designer and the user, with aim of mediating the information that is generated throughout the design process. The end goal is to have fluency and understanding between the designer and the user, which will allow for the thing that is being designed to be meaningful in its outcome.

A UCD process can consist of a mixture of methods and tools, both investigative and generative which are used to develop an understanding together with the user.

Generally, there are four design phases in UCD.

1) Understanding the context in which a system or artefact is used by participants.

2) Identifying and specifying the participants requirements. 3) A design phase in which solutions are proposed.

4) An evaluation phase used to assess the outcome of proposed solutions and evaluate those against the participants requirements and the context. This can be used to evaluate the performance of the design. It is worth noting that the design process in this thesis, although not using the same terms, follows the same structure presented above. For example, the research phase presented in Section 4, represents the first design phase shown above where the aim is to understand the context of the system or artifact. The exploration phase presented in Section 5, represents the second phase shown above, where the participant’s needs, and requirements are identified and specified.

2.2 Interviewing

Described as one of the most common ways of data collection in qualitative research (Jamshed, 2014), interviewing is an invaluable method for a UCD process, especially early on, when the goal is to understand the context and design space in relation to the users. Jamshed (2014) points out that as research interviews do not generally lack structure, they can usually be categorized as semi-structured, lightly structured, or in-depth.

This thesis employed a semi-structured interview format, which in definition consists of presenting the interviewee with a focused set of questions or topics, whilst trying to make optimal use of the timeframe in which the interview is held. Typically, there are one or more core questions, followed by smaller relevant questions that explore the topic of interest.

In combination with the interviews, video and sound recordings were used to capture the exchanges, which Jamshed (2014) explains as a useful asset it allows for the chance to analyse the material in depth. Furthermore, none of the information is missed as can be the case with hand-written notes. The action of recording can however be controversial and thus it is important to deal with the captured material appropriately in accordance with the interviewees and the guidelines for ethical research by the Swedish Research Council.

2.3 Focus Groups

Much like interviewing, focus groups make use of questioning and probing the feedback given by participants (Guest, Namey, Taylor, Eley, & McKenna, 2017). The main difference between focus groups and individual interviews is the potential benefit of the group dynamic that becomes part of the design process. The gist of it is, that a group setting allows for the potential gathering of information that might not emerge when questioning individually. Group setting have a different level of interpersonal and interactive dynamics, which as a result can produce different information than a one on one interview might.

Guest et al. (2017) additionally point out that some researchers pertain the notion that individual interviews produce more detailed information than focus groups. Individual interviews generally lend themselves more for the discussion of and insight into the interviewee’s personal perspectives and opinions, whereas focus group settings generate more of what is referred to as surface data. With this taken into consideration, focus groups were used to compliment individual interviews, rather than replace them.

The focus groups were help multiple times throughout the project.

2.4 Affinity Diagramming

Affinity diagrams are a way to make sense of large amounts of qualitative data that might be unstructured, broad or otherwise difficult to connect (Lucero, 2015). The practice of affinity diagramming, according to Lucero (2015), often focuses on analysing contextual inquiry data, which can then be used to derive user profiles or requirements, as well as help with problem framing and ideation.

Generally, a common way to create affinity diagrams is by writing down information on sticky notes and then clustering this data into relevant clusters in relation to the goal of the project.

Affinity diagramming seemed like an appropriate technique in combination with the UCD process this project was employing, where large amounts of contextual data were being generated in the research and exploration phases in order to establish the user requirements and design space.

2.5 Story Completion

Story completion, a method previously unknown to me, was something I became aware of whilst searching for ways to work and conduct design research online. Story completion is a novel approach for qualitative research. As such, it is often described as a very different style of inquiry when compared to traditional techniques such as interviewing.

Like many qualitative research methods, story completion is described as a useful tool that lets researchers access meaning around a particular topic

(Clarke, Braun, Frith, & Moller , 2019). The reason as to why I wanted to try and make use of this method specifically, was that the nature of it draws on the understanding and expression of the participant’s perception of the topic in light of social norms. Considering that communication in any form is full of social norms, which often influence or even dictate the behaviour of participants, the idea that this would be a suitable method for exploring the topic seemed plausible. Additionally, as pointed out by Clarke et al. (2019), participants may feel more open to provide information they would not otherwise due to a sense of less accountability. This can be the result of story completion not being done face-to-face and stories and the narrative in which the story is written, both providing some the sense of it being nonpersonal or indirect.

Clarke et al. (2019) mention that analysing patterns is one way to make use of the data collected with story completion, which was the main use of the data in this project.

2.6 User Interaction Diagrams (UIDs)

User interaction diagrams (UIDs) are diagrammatic representations of the interaction between users and applications (Zeferino & Vilain, 2014). They are useful for summarizing and showing the information that is being exchanged between the user and the application, which is known as states. Additionally, these states are exchanged via transitions, which gives the interaction a different focus.

2.7 Prototyping

Prototypes are widely recognized as a means for exploring and expressing designs, especially in interactive artifacts. Primarily prototypes are built as a means to express the different states of a design and reflecting the way in which it evolves throughout the design process (Houde & Hill , 1997). Houde & Hill (1997) pointed out that a key factor for prototyping is focusing less on what the prototype is and more on what it is in fact prototyping. In other words, the prototype should strive to find out how the artifact exists in the user’s life, through what it is testing. When the prototype aims to be less concerned with what it is and more with what it is testing, we as designers have the potential to explore things such as how an artifact might look or feel, or how it might be implemented.

With that in mind, another important element of prototyping is that the process should be iterative. Prototypes should evolve along with the concepts and goals of the project, adapting the findings in a way that makes sense in terms of what is being prototyped.

2.8 Laban Movement Analysis

Laban movement analysis (LMA) can be viewed as a sort of method for describing, visualizing, interpreting, and documenting human movement in depth.

The intention of using LMA in this thesis was to help with the task of understanding movement and nonverbal cues in FTF communication. Computer animator and certified Laban movement analyst Leslie Bishko gives an excellent summary of the principles and categories of movement of LMA (Bishko, 2014), as well as practical information for utilizing the language.

Principles of LMA

Among the core principles of LMA are function and expression. Function is regarded as proceeding expression. In other words, movement comes before meaning. This posits the idea that to be able to gauge meaning it might be logical to start by analysing the movement.

Inner and outer are two terms used regarding the body’s relationship with the environment. Movement reveals how an individual exists within their surroundings. Inner and outer are fluctuating states that affect one another. A simple way to explain inner and outer is by imagining the exposure to loud noise from perhaps construction work. The noise affects your internal experience prompting an external response of covering your ears whilst making a facial expression that might indicate discomfort.

Stability and mobility are continuous states which movement goes through. Stability represents a resting place, whereas mobility explains how movement leaves or arrives at this resting place.

The final principles of LMA are exertion and recuperation. Energy is exerted to bring ourselves into action through movement. This exertion is followed by periods of recuperation. Exertion and recuperation often present patterns and rhythms.

The most obvious way to observe these principles is in sport. Take a game of football. The athletes exert energy in bursts chasing and kicking the ball, followed by brief periods of rest, where they recuperate their energy. The pattern demonstrated here is very basic yet consistent.

Categories of Movement

The full scope of the parameters of movement in LMA is outlined in five categories (Bishko, 2014),

Phrasing

Phrasing can be viewed as an overview of movement that includes a complete description of how movement components are sequenced, layered, and

combined within a timeframe. Movement phrases facilitate the patterns of movement that make individual expression unique.

There are five stages in a movement phrase known as: preparation (intent), initiation (anticipation), exertion/main action, follow through/recuperation and transition. These stages can be explained with the action of jumping in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Diagram of LMA categories (Bishko, 2014).

Preparation includes the build-up and preparation that leads to the initiation of the main action. During this stage facial expressions are usually prominent alongside more subtle movements, like a slight shift of the body mass before bigger movements are made.

The initiation phase consists of the final movements that transition into the main action. With full body movements this often involves a major weight shift and movement in the opposite direction of the main action. This can be seen in the action of jumping, where the arms and body pull back, before exerting the energy in a forward motion in Figure 1.

Exertion happens when the main action is performed. This is the purpose or intention of a movement. The intent of jumping is exerting energy to become airborne.

Follow through does not specify the following through of motion, but rather the following through of the main action. This stage represents the part of the phrasing where recuperation from the action occurs, returning to a neutral stance or resting place for movement. At this stage, the actor can transition into another action.

Body

This component is tasked with describing the structural aspects of the body in motion. That means looking at how body parts are connected and how they influence one another during an action. One of the important aspects of this

category is making the distinction of where a movement begins and where it ends. This makes it easier to figure out the start and finish of a movement sequence.

Effort

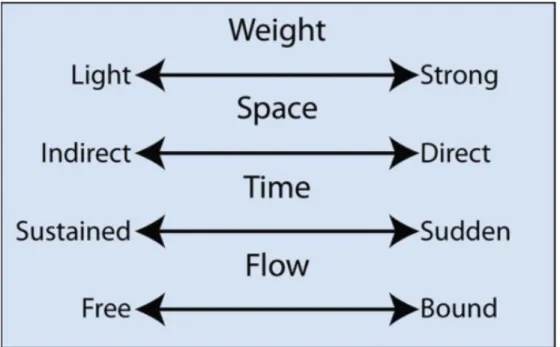

Effort reflects the inner intention of a performed action, by identifying the qualities of the movement attributes. In LMA effort is defined by four factors known as weight, space, time, and flow shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Effort factors (Bishko, 2014).

The effort factors provide additional depth to the interpretation of an action. Every meaning of an action can thus be interpreted on various levels. For one the action itself indicates a purpose or intention, like swinging a bat with the intention of hitting a ball. The way the bat is swung can give additional meaning regarding the person that is swinging it.

Movements usually include multiple effort factors which are defined as states and drives. Furthermore, flow is considered to always be present.

Shape

Shape describes the way that shape changes in relation to movement over time. Shape can indicate how the body feels about the circumstances of the situation. In other words, Shape often reflects the internal feeling or emotion that is communicated through gesture.

Space

The final category concerns the environment that performed actions are situated in. Whereas the body category describes the relationship of bodily components to one another, space describes the relationship of the body to the environment in a geometrical manner.

Notation

Making use of the categories presented above relies the ability to document information. There are two prominent notation systems in LMA defined as labanotation and motif description (Bishko, 2014).

Labanotation is the primary notation system of LMA. It is characterized by employing a detailed array of symbols able to depict all the components of the five categories of movement.

The other, lesser-known labanotation system labelled as motif description is described as an observation tool and a creative means for interpretation of movement, with a more thematic approach. Despite focusing mostly on the essential elements of movement, it still employs the vast number of symbols used in labanotation.

3 Background

3.1 The Cues-Filtered-Out Approach

The CFO approach according to (Sumner & Ramirez, 2017), consists social presence theory (Short, Williams, & Christie, 1976), media richness theory (Daft & Lengel, 1986) and the lack of social context cues hypothesis (Sproull & Kiesler, 1986), among others.

Sumner and Ramirez summarize that within the CFO approach, FTF communication is characterized as being the richest and therefor superior form of communicational style. In the same theoretical context, CMC is associated with having leaner channels due to the absence or lack of social context cues, making it the inferior form of communication due to allowing less interpretation of social content and therefore convey less meaningful communication.

3.1.1 The Lack of Social Context Cues Hypothesis

CMC has long been considered as being unable to support socio-emotional communication in a satisfactory way when comparing it to FTF (Riva, 2004). The lack of social context cues hypothesis (Sproull & Kiesler, 1986) is one the earliest assessments CMC and FTF communication. It concludes that CMC is void of nonverbal and contextual social cues that exist within FTF interaction. The glaring issue with this hypothesis was that it did not take into consideration that humans tend to adjust to their environments. People often showed way of overcoming the absence of social cues in CMC, showing levels of personal and emotional information being exchanged. This realization was

a crucial aspect which is also recognized in other theories in the CFO approach.

3.1.2 Social Presence Theory

Social presence theory acknowledges the notion that CMC can convey social cues and therefor social context content.

(Walther, 2011) explains social presence theory in relation to CMC. The theory acknowledges that the ability to convey levels of nonverbal communication and verbal content differs between CMC media but is not totally absent. It concludes that because CMC media supports fewer social cues it therefore conveys less social content experienced by users, overall making it inferior to FTF communication for personal and emotional exchanges.

3.1.3 Media Richness Theory

(Kock, 2004) referred to the concept of richness, explaining it as being more elaborate than that of social presence, and by this standard he suggested that media richness theory can be seen to some extent as an extension of social presence theory.

With this in mind, media richness theory (Daft & Lengel, 1984) made similar claims to those of social presence theory (Short, Williams, & Christie, 1976). The idea was that media could be ranked by the immediacy of communicators and the bandwidth of social cue support in the media channels. Media richness theory thereby posits that communication is best when the needs of individuals are met by matching the channel richness and the complexity of the message.

According to (Daft & Lengel, 1986) media richness theory also held the stance that CMC media which facilitates less support for social cues are lesser than those with more support.

3.2 Newer Theories

On the other end of the theoretical spectrum, numerous newer theories challenged the assessment of FTF communication and CMC made by the CFO approach.

Among some of these theories were social information processing theory (SIPT) (Walther, 1992), the hyperpersonal model (Walther, 1996) and the psychobiological model (Kock, 2004).

3.2.1 Social Information Processing Theory

Walther (1992) developed SIPT under this premise that FTF communication and CMC are much more complicated than the CFO approach made them out to be.

Described as one of the dominant theories in CMC focusing on the interpersonal relations (Sumner & Ramirez, 2017), SIPT was primarily used as a model for understanding how relationships are formed despite the absence of social cues in CMC media.

According to (Walther, 1992) SIPT supports various concepts presented by the CFO approach. Namely, the notion that nonverbal cues convey and influence emotion, thus providing meaning and impression to communicators, ultimately allowing relationships to form in CMC through interpersonal interaction. Furthermore, SIPT also pertains the idea that the ability to support social cues has a considerable outcome on the quality and experience of communication. Finally, SIPT agrees that CMC media often falls short when compared to FTF communication in these regards.

SIPT argues that the absence of social cues does not render communication void of meaning. Walther (1992) highlights that the CFO approach oversimplifies its assessment of social cues. SIPT assumes that social cues, especially nonverbal cues, are typically perceived as a whole and therefor the absence of one or more of these cues might alter communication but does not necessarily render it inferior for communicating. In other words, the absence of social cues is often exaggerated, resulting in a questionable assessment CMC media.

Humans are social by nature and tend to adjust to their environments. This means that individuals engage in relational behaviour regardless of medium. Despite the lack or absence of social cues in some CMC media, people tend to reach similar levels of interpersonal interaction found in FTF communication by adjusting their behaviour to the situation.

3.2.2 The Hyperpersonal Model

(Sumner & Ramirez, 2017) explain that the hyperpersonal model can be viewed as an extension of SIPT. It takes the idea that CMC can reach similar levels of interpersonal interaction as FTF communication to further, proposing that CMC can reach heightened levels of interpersonal interaction when compared to FTF communication. This builds on the idea that fewer social cues can be a good thing for communication. Furthermore, it provides an example of how communicators adjust and overcome the lack of social cues in CMC.

The model explains how this might be the case in the context of text-based CMC, describing four distinct factors relating to message construction and reception:

1) Effects due to receiver process.

Receivers of messages might exaggerate the perception of the sender. In absence of FTF cues, rather than failing to form an impression, receivers create the missing information based on what they perceive to be missing. This can include idealization or personal interest.

2) Effects among message senders.

Senders of messages may only transmit the perception that they want the receiver to have. In other words, the message is formulated in a way that portrays the sender in a self-selective manner. People generally do not transmit information that could negatively affect the perception of themselves by the receiver. Messages also do not suffer from the same potential undesirable interaction behaviours as FTF communication, such as mismanaged eye contact. This is one example of positive effect due to lack of a nonverbal cue.

3) Attributes of channel.

Channel refers to how CMC as a medium enables deliberate construction of messages which are favourable. In short, users exploit the mechanics of CMC media. One such mechanic is the ability to respond after having taken the time to consider a response that is favourable, as opposed to the immediate expected response in FTF communication. Other exploits include the abilities to edit or delete messages, altering the initial meaning. Overall, this challenges the need for immediacy in CMC, which is present in FTF communication, explaining again how the absence can have positive effects on the situation.

4) Feedback effects.

Feedback refers to the three previous factors being felt mutually among individuals. This creates a feedback system, which explains how text-based CMC magnifies the dynamics of each of the previous factors. In other words, a receiver gets a selectively self-presenting message and idealizes it. That receiver might then respond in a manner that is mutually felt and reinsuring in respect of the partially changed persona of the sender, potentially amplifying the dynamics of the exchange in a positive way.

3.2.3 Media Naturalness Theory

The psychobiological model developed by (Kock, 2004) was an attempt to replace media presence theory and media richness theory. It is today referred to as the media naturalness theory. The model argues that the naturalness of CMC media consists of assessing its similarity to the FTF medium and the cognitive effort required from an individual using the media for knowledge transfer.

(Kock, 2004) explains the various scientific components that support the notion that our brain is predisposed to be better at FTF communication. This assessment is based on our biological communication apparatus, which is made up of sensory and motor organs relevant to communicating, as well as brain functions associated with these organs, which are primarily made for FTF communication.

Media naturalness was assessed by five key elements: (a) colocation, which would allow individuals engaged in a communication interaction to share the same context, as well as see and hear each other; (b) synchronicity, which would allow the individuals to quickly exchange communicative stimuli; (c) the ability to convey and observe facial expressions; (d) the ability to convey and observe body language; and (e) the ability to convey and listen to speech. These key factors affectively represented what was considered as the full spectrum of FTF communication.

3.3 Related Work

3.3.1 Digital Body Language

The first of these works is a project that explores body language in digitally mediated written communication. This concept is explored via a text processor that takes the input properties of the typing on the keyboard and then uses that data to dynamically change the text output, reflecting the typing characteristics.

The aim of this project is to explore the interaction with technology and characteristics therein, investigating how this might open up the design space for alternative context regarding language (Knudsen, Billewicz, & Di Giovanni, 2018).

Apart from concerning itself with communication and technology, the main reason I found this project inspiring for my topic was the possibility to try out the artifact that was created by Knudsen et al. (2018). This was a nice change from the usual research in which you read and view images or illustrations, whilst trying to understand the concepts that are being discussed by the authors.

Figure 3. Digital Body Language example.

Figure 3 illustrates the result of my try with the text processor known as Digital Body Language.

The processor records four types of typing characteristics, which it then translates into the generated text. The resulting text then reflects the supposed characteristics associated with the person that typed it, which one can reflect on in an effort to give the words additional meaning. The categories, or characteristics which are present in the text are defined as tempo, reflection, hesitation, and regret.

In Figure 3 the resulting text shows these categories. Tempo is the most straight forward. The faster you typed, the closer together the letters are. In my case most of the words were typed quickly. Breaks between words are shown by whitespaces. The bigger the space the longer time between each word was taken. This is where it becomes interesting. The way you interpret this information is subjective and speculative. Did someone interrupt you while you were typing? Or perhaps you were taking your time to really think about the wording. That might mean you care about the other person or you simply care what the other person thinks about you. This notion is taken further by words that are faded. This happens when you begin typing a word and then pause in the middle of typing it. This could perhaps show further hesitation and thus speculation as to why you might have hesitated. Lastly, you have regret. Regret is shown by font size changing depending on how many words were deleted.

Something I found fascinating was how meaning was added to static text and just how subtle differences in elements of communication can have such a large impact on the process in terms of user behaviour and interaction. In other words, this drove my curiosity more toward wanting to explore the existing dynamics in the FTF communication process and how exactly nonverbal cues can affect the outcome of engagements between individuals. Lastly, perhaps one of the most inspirational aspects of the Digital Body Language project, was seeing the potential for changing a form of communication that seemed so strict and conventional by opening the design space creatively.

3.3.2 Nonverbal Cues and FTF Communication

(Bavelas, Hutchinson, Kenwood, & Matheson, 1997) assessed FTF dialogue as a standard for other forms of communication, including CMC.

One hypothesis is that CMC could be designed for the natural features of human communication, with the characteristics of those being naturally found in FTF communication. This means rather than focusing on solving problems based on technical aspects, design should focus on the principles closely related to the communicational dimensions exist in FTF communication. The conclusion of their research is that using FTF dialogue as a standard for other forms of communication, the design of new communication systems might benefit and serve as a source for solutions.

The main reasoning for their approach is that FTF interaction is the original form of human communication. This is also supported in media naturalness theory. (Kock, 2004) explains that FTF interaction is an important part of understanding CMC because of the biological disposition of humans. In short, this means that FTF interaction is seen as the most natural form of communication because our bodies are made for this type exchange, further proposing that CMC should in some way adhere or at least be aware of this fact.

Bavelas et. al. (1997), like many of the theories surrounding CMC, hypothesize how the lack or limitation of nonverbal and verbal communication in text-based CMC affects the experience of communication. In their framework, they provide three features that are according to them, are only fully realized in FTF dialogue. They are defined as: unrestricted verbal expression, meaningful nonverbal acts, and instantaneous collaboration between individuals.

Three important questions were asked regarding other forms of communication:

• In comparison to FTF dialogue, what is lacking?

• What consequences might the loss of accustomed capacities of daily communication have?

• Based on how people make up for this loss, how can design make up for those losses?

Much like SIPT and the hyperpersonal model, Bavelas et. al (1997) explain that the limitations found in various forms of communication, reveal the way people modify formats to simulate the missing features of FTF communication.

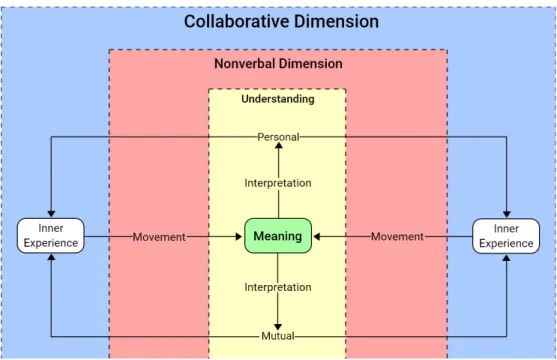

The Nonverbal Dimension

The nonverbal dimension potentially includes any act other than words. This is a huge scope and the authors limited themselves to nonverbal acts that are directly connected to the words. These nonverbal acts are specified as facial expressions, gestures, eye contact and paralinguistic features of spoken voice. They point out that these nonverbal components are usually used together with words to create a message in FTF communication, where the meaning of the words includes the meaning of the nonverbal act. Nonverbal information such as posture, smell or clothing is less associated with the words in this sense and are thus excluded by the authors.

The Collaborative Dimension

Bavelas et al. (1997) state that the fact that FTF communication is social interaction is often overlooked, meaning that it consists of two-way interaction, not one-way interaction. This is labelled as the collaborative

dimension, which summarizes the nature of FTF dialogue in relation to interaction attributes, such as synchronicity or immediacy.

The collaborative dimension is reflected in the CFO approach, which highlights that the presence of social cues is not the only important aspect of meaningful communication. FTF communication allows elements that affect the interactivity and collaboration between individuals, such as immediacy or synchronicity, acknowledging that they are often less prevalent in CMC. FTF is a collaborative process, where people coordinate and monitor their mutual understanding.

The authors also pertain the notion that people transmit a great deal more than mutual understanding through the collaborative dimension, such as irony. Concepts like these can be easily misunderstood in other forms of CMC due to limitation of the collaborative dimension of communication. Emails for example, happen asynchronously, which affects the collaboration in terms mutual understanding of concepts such as irony. The words together with the nonverbal act form meaning. This combination is received and understood by the other person and acted upon by responding with either words, or nonverbal acts, or both. This creates a mutual understanding of the concept of irony through the collaborative dimension.

3.3.3 Nonverbal Communication in Service Encounters

This project, as the name indicates, explores the importance of nonverbal employee-customer interactions in service encounters. The reason I engaged in this project was first and foremost the immediate relation to my own goal of exploring and understanding nonverbal communication from a process standpoint.

The fact that nonverbal communication is a crucial aspect of all types of communicational encounters is not a mystery, but the idea of looking at various projects that explore nonverbal elements of communication in different fields and scenarios seemed like a useful starting point for my own project.

Perhaps one of the biggest realizations or reflections I had whilst researching this piece of related work was the emphasis that was put on the importance that the use of nonverbal cues of service employees has on customer experience. It affects the immediate experience and has a huge impact on the way customers evaluate services, products, and brands. With that, the realization that nonverbal communication quite possibly has similar effects on the way users experience and thus evaluate various different digital media was made and thus became one aspect which I ended up paying much attention to during the design process of my project.

The project outlined some of the various powerful channels of nonverbal communication which I found useful as a starting point for my own investigative inquiry, both in terms of desk research as well as interviewing.

Eye contact became one of the more thoroughly explored aspects throughout my design process and this piece of related work provided some good information regarding the use of the yes in communication. Eye contact is particularly important regarding interpersonal relations and perception of one another during a communicational exchange (Sundaram & Webster, 2000). In the case of service encounters, it is particularly important for creation warmth and serving as the basis for many other nonverbal elements that help to form a relationship. Additionally, Sundaram & Webster (2000) cover other parts of the body such as the mouth and head, explaining their individual qualities in terms of expression, but more importantly the notion that they together have the biggest impact on the way out movements are perceived.

In other words, the project outlined that individual body parts, while some may have a bigger impact than others, essentially rely on their dynamic relationship with one another, which has the biggest overall impact on relationship building and communicator experience.

In summary, the work of Sundaram & Webster (2000) made me eager to explore the relationship that existed in FTF communicational exchanges and exploring how this perhaps translates into the digital realm of communication.

3.4 Summary and Way Forward

My initial interest in communication was solely focused on the idea of redesigning CMC media. This interest was a result of my personal bias, which very much reflected the idea that FTF communication is superior to most, if not all forms of CMC.

As I began my research, I gradually learned that my views of communication might not be entirely unfathomed. The CFO approach, for one, supported my personal bias toward CMC media whilst providing an explanation in the matter. My personal bias, however, began to fade, as I worked my way through the numerous newer theories regarding CMC. These theories challenged my perception of most forms of CMC being inferior to FTF communication by providing equally convincing arguments supporting these claims.

With a more open-minded outlook regarding my enquiry I noticed, that even in their divergence, the two opposing sides of the theoretical spectrum shared some mutual agreement.

The turning point for my enquiry was marked by a research gap that highlighted the oversimplification of the way nonverbal cues are assessed in the CFO approach (Walther, 1992). This research gap voices the need to generate a better understanding of nonverbal cues in FTF communication which would ultimately be able to form a more complete assessment of their

role in CMC. Although newer theories had expanded the understanding of the use of nonverbal cues, the need for further exploration persisted.

I saw this an opportunity to generate knowledge in the field of interaction design. Perhaps a better understanding of how nonverbal cues function in FTF communication could be used to explore an alternative approach to the design of certain CMC media.

The type of media that I wanted to explore in this regard was text-based media, inspired by the Digital Body Language project (Knudsen, Billewicz, & Di Giovanni, 2018).

My decision was further supported by the work of (Bavelas, Hutchinson, Kenwood, & Matheson, 1997), which drives the notion that FTF dialogue can be a standard for assessing and ultimately designing CMC and communication technology, which in my eyes seemed to go hand-in-hand with exploration of text-based CMC media.

With the nature of my research enquiry first and foremost aiming to generate knowledge and understanding, the initial research question was formulated to be open and explorative, based on the findings of the background research. The aim of this was to investigate the design space in such a way, that it might open up possibilities of finding more specific design opportunities regarding the topic.

3.5 Participants

As mentioned by (Bavelas, Hutchinson, Kenwood, & Matheson, 1997), communication is a two-way interactive process. As such, I planned to recruit people that could participate in my design process. Furthermore, I was aiming at recruiting long-term participants.

Another aspect that I considered when deciding to have consistent participants, were previous experiences with participant involvement in projects. What I found was that having different participants at various stages of a project can limit their ability to contribute because of information that they were lacking because they were not part of the design process throughout the project. By being involved from the beginning to the end I hoped to provide them with more opportunity to keep track of developing and evolving concepts and drive design process. Furthermore, as pointed out in Section 2.2, group dynamics can bring forth information that might not emerge in a one-on-one setting and thus having both individual and group settings was an attempt at increasing the chances of meaningful insight and discussion. By the end of the interviews the focus group consisted of five enthusiastic participants.

3.6 Ethical Considerations

The recruitment process relates to the ethical considerations that had to made in accordance with the guidelines for ethical research by the Swedish Research Council.

Interviewees were asked if they would like to be more involved in the project. If they were interested, they were presented with a formal consent form. The form summarized the aim of the study, as well as the procedure of design activities. The topics of data storage, anonymity, and confidentiality were also covered. The consent form concluded with information about the withdrawal from the project.

Upon reading the form, potential recruits were asked if they had any questions or concerns. If they agreed to be part of the study and if they were satisfied with the conditions, they were asked to sign the form.

Whilst making sure that ethical guidelines were followed, the secondary objective was to make participants feel comfortable with their possible involvement in the project. Therefor it was important that they understand what their engagement might entail. With the project being conducted online I felt additional need to reassure the participants of the various aspects concerning their involvement.

4 Research Phase

This section describes the interviews framing of additional research questions.

4.1.1 Field Interviews

Based on the background research, I was curious to find out how people assess and understand the role of nonverbal cues in communication. As such, the questions were focused on the use of nonverbal cues and the number of nonverbal cues supported.

Six separate interviews were conducted. Preference and Perception

• FTF communication was regarded as the preferred type of engagement.

• CMC media was described as serving a more functional role, whereas FTF communication goes beyond formality and purpose, into more personal and meaningful engagement between individuals.

• Nonverbal cues are used to express meaning through movement. • Without nonverbal cues some emotions and meanings might be

inexpressible.

• Nonverbal cues were also compared individually on their importance based on how expressive or useful they are.

• Interviewees argued that fewer social cues will affect communication negatively, based on their assessments.

• Nonverbal cues were regarded as more important than verbal cues based on three reasons. Firstly, there are a greater number of nonverbal cues. Secondly, nonverbal cues often overrule verbal cues. Thirdly, interaction with nonverbal cues is more fluid.

• The eyes were generally regarded as the most powerful tool for generating nonverbal cues, followed by the rest of the face.

• Movement and positioning were described as the two major factors for creating nonverbal cues with the eyes. These nonverbal cues were usually referred to as expressions.

• Nonverbal cues were often defined as movements and positioning. Nonverbal Cue Support

• Interviewees evaluated different media by their ability to facilitate nonverbal cues, assessing the number, type and use of the cue itself. • The absence of nonverbal cues can be overcome via the numerous additional features situated in CMC technology, such as emoticons and graphics interchange formats, more commonly known as GIFs. • Interviewees argued that these features are less expressive and might

be more prone to misinterpreted than their FTF counterparts.

• On the contrary, the notion that many features enable new or enhanced possibilities over traditional nonverbal cues was pointed out. In the case of using a Gif, the sender has an enormous amount of extra ability to express themselves. Whole stories can be expressed I a matter of seconds. In comparison, an individual would have trouble achieving similar results in FTF communication through the use of nonverbal cues.

4.1.2 Online interviews

Five online interviews were conducted. These interviews put emphasis on the role collaborative dimension in relation to the use of nonverbal cues.

• Again, comparisons between FTF nonverbal cues and digital adaptations of those cues were made, this time to try and understand the collaborative dimension.

• Digital adaptations of FTF nonverbal cues were regarded as having a lower form of interaction because they are limited to the affordances of the medium.

• This was further explained with the use of emoticons. As emoticons are often used in text-based CMC media, they inherit many of the interactive attributes that the medium affords. Though emoticons can be animated, their interactive use is always asynchronous, such as the medium they reside in. FTF communication affords an entirely different experience of collaboration in comparison.

• As such, FTF nonverbal cues were regarded as having the highest level of interaction, whereas verbal cues were ranked second.

• Some things cannot be expressed, or at least not expressed the same way in CMC e.g. support or care. This is also due to the elements of collaboration.

• FTF communication affords a different level of interactivity and collaboration than CMC. As such, the use of nonverbal cues differs. • The use of nonverbal cues in FTF communication had been generally

regarded as better, and maybe this was a result of the collaborative qualities of the interaction.

• Video communication was considered as being on par with FTF communication, at least from an affordance standpoint

4.1.3 Summary and the Way Forward

The interviews had provided some insight into the way people perceive and understand the use of nonverbal cues in communication.

Understanding the use of nonverbal cues was more closely related to understanding their interactive use in communication. With the focus being to understand this in the context of FTF communication, the next step was to explore this based on the data that had been generated so far in the research phases.

Additionally, with the interviews, the initial research question had taken on some additional meaning due to the probing of the topic. As a result, additional research questions were formulated to assist with the investigation of the main research question:

3) How are nonverbal cues used interactively in FTF communication? 4) How might we assess, and design text-based CMC media based on a

better understanding of FTF nonverbal interaction?

5 Exploration Phase

The exploration phase focused on more thorough analysis of the use of nonverbal cues regarding interaction between individuals.

5.1 Affinity Diagrams

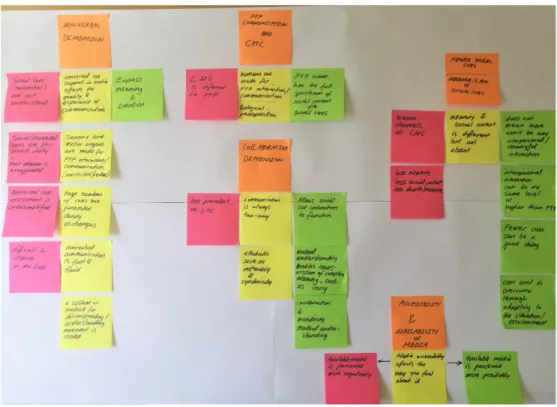

Two affinity diagrams were created. Due to issues with timing, the first of these was created by me. This diagram represented the main points from the background research.

The first diagram was presented during a focus group session.

Figure 4. Background research affinity diagram.

The categories in the initial diagram represent the main topics of interest that were identified in the background research as clusters in which some of the finer details can be found. For example, the nonverbal dimension cluster includes things such as the notion that the support of nonverbal cues affects the quality of the interaction, or that social cues are not properly understood. In short, this diagram holds some very general pointes that were identified in during in the background research and the second affinity diagram consists of more refined aspects based on those points and the interviews, categorized and prioritized by the participants during the focus group.

Figure 5. Interview/focus group affinity diagram.

Figure 5 can be seen as an elaboration or extension of Figure 4, because of the analysis of the background research affinity diagram, based on the interviewing process and insights.

Looking again at the nonverbal cluster, the more generic statement of nonverbal cue support has been refined relating to the previous discussions during the interviews. Nonverbal cues were described as affecting the experience by the way they are supported, but additionally by the way they are used as well. Rather than stating that the topic of nonverbal cues is not understood is expanded upon with information on how participants describe the understanding of nonverbal cues.

As the focus group continued to work through the clusters, a more complete image of what was most important to the participants became clearer. This was a result of the participants voicing their concerns and interests regarding the various points that were being discussed.

Although there were some disagreements on which aspects were considered the most important, especially regarding the next steps of the design process, everyone generally agreed that every question and variable that might lead somewhere fell back to the same issue. That issue was that the nonverbal communicative process thus far had only been assessed based on personal experience and imagination. Additionally, everyone agreed that to better understand the process, movement would have to be more thoroughly investigated as it is the start and end point of nonverbal cues.

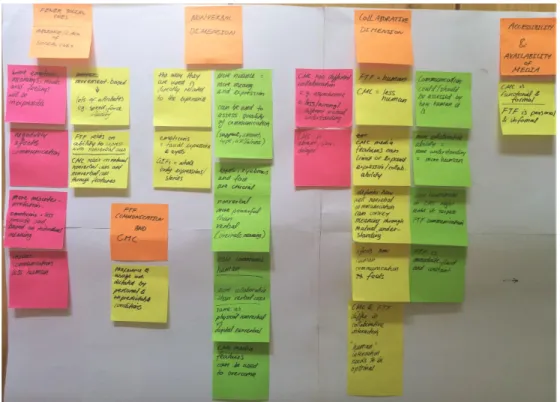

5.2 Story completion

Based on the previous focus group, the next step was to get our toes wet, so to speak. To do so, story completion was used as a way for the participants to express their understanding of nonverbal communication in a more hands-on manner.

The story completion exercises consisted of two hypothetical scenarios. Each scenario described the verbal exchange between two individuals. The participants were tasked with providing the facial movements in these scenarios. Furthermore, they were asked to provide an explanation of what meaning the nonverbal cues provided.

Figure 6. Story completion section.

The way that the patterns were identified was through the analysis of the material produced by the participants. As every participant was presented with the exact same scenarios, it was possible to make comparisons of the information given for each of the actions. That included comparing the different verbs that were used, such as frowning, and the movements that were used to describe the actions. Based upon similarities and differences patterns were thus identified. For example, if three out of five participants used the same actions or movements for describing a moment in the scenario, I would then take that as a pattern that positively supports the nonverbal communication process to occur in such a way. If participants had vastly different answers, then I would generally assume that this part of the process was either unclear, misunderstood or simply able to occur in multiple ways. Figure 6 shows some of the material that was produced during the exercise which was then analysed as described above.

I regret not having done follow-up interviews or a focus group to discuss the findings with the participants to try and clear up which of my assumptions might have been accurate.

5.3 Nonverbal UID 1

The UID shown in Figure 7, reflects the understanding of the nonverbal communication process based on the patterns identified in the story completion exercise.

Figure 7. Focus Group UID of Nonverbal Interaction.

As mentioned, UIDs are useful for showing states and transitions. States would refer to the meaning that the transitions express in this case. That means a state could be helplessness or sadness, as described by one participant in Figure 6.

In the UID, states are seen as passing from one communicator to another. The state is expressed and turns into meaning, which then gets interpreted, understood, and turns into an impression.

States move via transitions, in this case movements which form nonverbal cues. States and transitions are part of a fluid and seamless process.

5.4 Video Analyses

The process of analysing the movements of nonverbal interaction started with identifying sections of video footage that was recorded during the interviews and following video calls. From this footage, smaller segments were extracted which were easier to manage. The five categories of LMA were then used to analyse this material and document the findings.

In accordance with formal consent contracts, this section does not include any of the video footage that was analysed but describes the process together with some of the documentation material that was generated. Additionally, video footage was kept and analysed offline during the process.

The LMA notation systems mentioned in Section 2.8 were rather complex, being comparable to reading and writing sheet music by professional composers and musicians. As such the employment of one of these exiting systems was deemed too time-consuming and a simpler version for documenting and visualizing the analyses was developed. This system aimed to record movement with sketches.

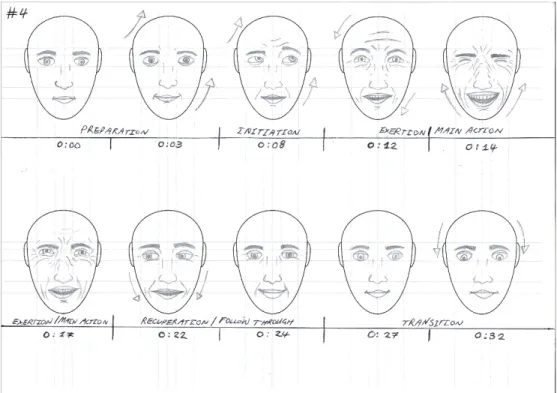

To speed up the sketching process a template of a head was created seen in Figure 8. Guidelines were marked out indicating the position of facial features to help with the consistency of sketching. The template was then finalized digitally.

Figure 8. Template creation.

The final template shown in Figure 9 was printed and used to document movement as phrasing sequences.

Figure 9. LMA documentation template.

Complete phrasing sequences were stored online and made available to participants accompanied by written notes. The video analyses produced two types of phrasing sequences.

The first thing to note is that LMA did not lend itself well to the analysis of facial movements as it is generally better used for movements of the body. The principles still applied, but the overall process sometimes felt a little bit ‘creative’.

Figure 10 illustrates a traditional phrasing sequence following the exact movement stages of LMA.

Figure 10. Phrasing sequence 4.

In Figure 10, the five movement categories of LMA can be seen. This is referred to as a phrasing sequence.

This phrasing sequence shows one individual’s movement over 32 seconds. The main action that is performed is laughing. In the preparation phase the subject shows very little movement in the corner of the mouth and eyes, accompanied with a slight head tilt. This was a common occurrence during the analyses, and often the movements in the preparation phases were so subtle that they were almost impossible to notice. This highlighted that LMA might be inefficient for facial movement analyses on one hand, but on the other hand it showed the delicate nature of nonverbal communication. This will be further explained in Figure 11.

When studying one individual’s movements, the most noticeable phase was always the main action or exertion phase. Coincidently this is the part of the phrasing sequence that is associated with the main state that is being expressed. The other phases all have the ability to alter the way the main action is perceived or interpreted, as well as forming their own meaning or nonverbal cues.

As a number of these phrasing sequences were analysed, I noticed that although providing detailed observations of movement, there was no way to assess or analyse interaction between communicators. As such the phrasing sequences took on another format.

Figure 11 illustrates a unique adaptation of the traditional phrasing sequence. Two individuals are analysed side by side to compare their actions and

movements directly, helping to observe the interaction with nonverbal cues and movements more easily.

Figure 11. Phrasing sequences 9 and 10.

As mentioned before, the preparation phase often consists of the most subtle movements. In Figure 11 we can see that this is not an issue during the process of nonverbal communication, and analyses indicated that communicators pick up on even the most subtle of movement. This can be seen in Stage 2 where the individual in phrasing sequence 10 has expressed their understanding and recognition of the individual’s subtle responsive movement in phrasing sequence 9.

As we look at the different stages in Figure 11, we can see and compare the movements that each individual made during the segment of the recording. Something highlighted by the analyses was that whilst many nonverbal cues might also be considered as gestural expressions, the term nonverbal cue could be applied in ways that were not limited to movement. One such instance was the absence of movement being described as a nonverbal cue. Additionally, the characteristics of facial features outside of movement were also associated with being nonverbal cues. Nonverbal cues were also pointed out as sections of movement or movements themselves. During many of the movement analyses, it was noticeable that the eyes are one of the more effective tools for nonverbal communication.

Focus Group

Another focus group was held to discuss and go over the material from the video analyses.

Perhaps the most noticeable component of LMA was shape. Shape often reflected the most obvious transitional states, reflecting a major change in meaning or part of the interaction where two individuals understood meaning mutually or personally.

Participants acknowledged that LMA was perhaps not best suited for this type of analysis. Certain categories such as the body and space were not able to be applied in our analyses. Participants described this as a result of focusing on the face, as well as having conducted the analyses on recordings rather than in person.

Effort, although perfectly applicable to the face, was not recorded in the documentation of the phrasing sequences. This was a shortcoming of the system that I used to record the movements. The participants agreed that effort is crucial to the understanding of intent of movement but acknowledged that it was difficult to illustrate by means other than writing the different effort factors down. With that said, various effort factors were discussed in terms of how they change the qualities of the movements and thus the meaning of nonverbal cues. Participants often described movements as sudden or strong. Describing these individual movements or parts of movements gave the overall action or phrasing sequence a descriptive quality of a similar style. Additionally, the whole process of nonverbal communication was often described as being fluid and synchronous, even if the individual movements were sudden or strong. Participants stated that even with sudden and strong movements, the interaction between individuals with these movements usually remains smooth and continuous.

Despite that, the material that was produced as a result and the knowledge generated was still largely helpful for understanding movement in nonverbal communication especially in terms of interaction using movement during FTF encounters. Many of the concepts and points made during the interviews had been observed and were understood more thoroughly, particularly in Section 4.1.1 under the title ‘The Use of Nonverbal Cues’.

Looking at the various phases that happen both before and after the main, highlighted how one can overgeneralize the intricate nature of nonverbal cues. Based on this notion, participants outlined the importance of not neglecting the smaller aspects of the interactive movements, as they can often play a big part in the overall experience of the exchange.

5.5 Nonverbal UID 2

After the completion of the video analyses another UID was created. Seen in Figure 12, this diagram can be seen as an extension of the UID in Section 5.3, Figure 7.

The general principles of LMA apply here as opposed to the previous UID and are better explained with this visual than the video analyses material.

Figure 12. Nonverbal interaction in FTF communication flowchart.

The inner experience represents the inner and outer states. They replace some of the states from the previous UID but show the same thing, which is the state that the individual is in. These states change continually based on the information that is being processed. In other words, states change as meaning is sent and received, based on the way it transitions during the exchange, and with that the thing that the individual wishes to express changes too. Stability often occurs when the inner experience is realized, as this is the state in which information is processed and movements tends to rest. Mobility refers to movement that defines how states transition to their resting place. The principles of exertion and recuperation are not so distinct, and their application as such can be rather broad or flexible. For example, exertion can be observed when the main action is performed through movement, followed by recuperation which usually occurs as stability is found in the inner experience state. The problem is that with facial movements, their starting and end points are much more difficult to identify and observe.

5.5.1 Summary and Way Forward

Thus far, this study focused its efforts on the exploration of FTF communication and understanding the use of nonverbal cues therein. The

goal of this was to be able to assess various CMC media with FTF as a standard, to potentially identify opportunities within the design space. With that, the next stage was to try and apply this knowledge to CMC.

6 Design Phase

This section describes the ideation, prototyping, and user testing.

6.1 Ideation Session One

The first ideation session consisted of some brainstorming and discussion regarding the research questions and the findings from the research and exploration phases. Referring to the work of Knudsen et al. (2018) and considering the research question, the logical start was to assess text-based CMC media.

The participants opted for messenger applications, emphasizing that they are hugely popular. Additionally, during the interviews, the participants had said that messenger apps were their most used form of not only CMC but communication altogether.

With that we set out to assess the use of nonverbal cues and interaction in a messenger application.

6.2 Text-based CMC

The assessment consisted of exchanging messages via phone between participants. Participants were asked to take notes of their assessments and experience.

In accordance with the formal consent forms, the real text messages are not included. Instead Figure 12 illustrates the formats of the text messages that were exchanged.

Figure 13. Text-based CMC Prototypes.

In comparison to FTF nonverbal communication and interaction, the immediate differences were mostly related to the effort factors described in the movement analyses in Section 5.4. Although there were no face or body parts to move, nonverbal cues consisted of various components found in the messenger application. Nonverbal cues consisted of things such as spelling, font size, punctuation, and timing between messages. The use of these components could be associated with effort factors in the same way that bodily movements could in FTF communication. As such they could also be described with effort factors and qualities related to those factors. For example, the timing between messages was described as direct, sudden, or slow. What participants found was that despite the different qualities associated with the messages, the overall experience was still described as feeling disconnected. The complete phrasing sequence of a text-based conversation was described as lacking immediacy, continuity, and fluidity. This was usually the case because of the characteristics associated with the use of messages themselves. This makes sense in that they represent a form of nonverbal communication within this context, and as such when someone pauses between messages, this can be experienced as affecting immediacy, continuity, and fluidity.

Comparted to FTF communication this the whole experience was lacking the immediate feedback or response. Additionally, even when communicators were attentive and sent messages immediately, the exchange still felt less continuous and immediate than FTF exchanges.

Participants explained this as an implication of the way in which the medium supports the use of nonverbal cues. During the interviews, participants referred to digital adaptations as being very reliant on the medium’s affordances and this could be seen in this assessment.