Impact of e-commerce on internationalization of Iranian SMEs

Full text

(2) Abstract The immediate goal for any small to medium-sized enterprise (SME) is to survive and maintain its independence. But, sooner or later, a small company will probably want to expand. With the trends towards global convergence and the adoption of outsourcing by firms of all sizes, growth usually means entering the international market. Meanwhile internet and e-commerce pose new challenges and provide new competitive opportunities for small and medium sized firms. The propose of this study is "To gain better understanding on impact of e-commerce on small and medium sized internationalization in Iran". It is done by comparison of existing literature and Iranian sample. The findings show that, Iranian SMEs use their websites as a brochure. Also the present research examined the influences of internet on export barriers and the findings show that internet may help Iranian SMEs in challenging with market risks. Key words: Small and Medium Sized enterprises, export barriers, Internet, website, ecommerce..

(3) Acknowledgments First I would like to thank Mr. Lennart Persson, my instructor, who has kept giving us invaluable advices, great supports, and all kinds of help. His kindness is always unforgettable. Next I would like to give thanks to Mr. James H Tiessen at Mc Master University who gave me many supports by his papers and also answering my questions. And then, I would like to thanks to Mrs. Nahavandi, supervisor at Tarbiat Modares University, and my friends. Finally I should thank my father, mother and my sisters. Without their love, trust, understanding and support, I would never have completed this thesis. I would like to give the best wishes to their health here.. Bahman Ajdari.

(4) Table of Contents 1. CHAPTER ONE-INTRODUCTION AND RESEARCH PROBLEM.....................................2 1.1 INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................2 1.2 SME'S DEFINITION .................................................................................................................3 1.3 INTERNATIONALIZATION DEFINITION .....................................................................................3 1.4 E-COMMERCE DEFINITION ......................................................................................................4 1.5 OPERATIONAL DEFINITIONS ...................................................................................................4 1.5.1 Internationalization ..........................................................................................................4 1.5.2 Small and medium sized enterprises in Iran .....................................................................4 1.5.3 E-commerce definition......................................................................................................4 1.6 GENERAL DOMESTIC ENVIRONMENT ......................................................................................5 1.6.1 Iranian exporter SMEs .....................................................................................................5 1.6.2 Iranian SMEs....................................................................................................................5 1.7 RESEARCH PROPOSE ...............................................................................................................5 1.8 PROBLEM DISCUSSION ............................................................................................................6 1.9 MANAGEMENT BEHAVIORS AND USING E-COMMERCE INTERNATIONALLY .............................6 1.10 ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS AND THEIR ROLES TO USE E-COMMERCE .....................................7 1.10.1 Economic perspectives.................................................................................................7 1.10.2 Industry norms .............................................................................................................8 1.10.3 Firm Factor..................................................................................................................8 1.11 SMALL AND MEDIUM SIZED ENTERPRISES AND EXPORT BARRIERS..........................................9. 2. CHAPTER TWO- LITERATURE REVIEW ..........................................................................13 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5. 3. INTRODUCTION.....................................................................................................................13 LITERATURE REVIEW ...........................................................................................................13 THE STUDY OF INTERNATIONALIZATION...............................................................................19 SMES AND EXPORT BARRIERS ..............................................................................................22 E-COMMERCE USE BY EXPORTING SMES .............................................................................26. CHAPTER THREE- METHODOLOGY.................................................................................28 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.6.1 3.6.2 3.7. 4. INTRODUCTION.....................................................................................................................28 RESEARCH APPROACH ..........................................................................................................28 RESEARCH STRATEGY ..........................................................................................................29 SAMPLE SELECTION ..............................................................................................................30 DATA COLLECTION ...............................................................................................................30 DATA ANALYSIS ...................................................................................................................30 Factor analysis ...............................................................................................................31 Mann Whitney U test ......................................................................................................31 SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................31. CHAPTER FOUR - RESEARCH DATA DESCRIPTION ANALYSIS AND RESULTS...32 4.1 DEMOGRAPHICS ...................................................................................................................32 4.1.1 Responses (questionnaires).............................................................................................32 4.1.1.1 4.1.1.2. 4.1.2. Firms with website .............................................................................................................. 32 Firms without website ......................................................................................................... 32. Number of employees......................................................................................................32. 4.1.2.1 4.1.2.2. Firms with website .............................................................................................................. 33 Firms without website ......................................................................................................... 33. 4.1.3 Years launched website...................................................................................................33 4.1.4 Productions.....................................................................................................................34 4.1.5 Firms work experience ...................................................................................................35 4.2 INTERNATIONAL ACTIVITIES.................................................................................................36 4.2.1 International experiences ...............................................................................................36 4.2.2 Sales and production volume of exporting......................................................................38 4.2.3 Target market .................................................................................................................39 4.2.4 International marketing plan ..........................................................................................40 4.3 RESULTS...............................................................................................................................41.

(5) 4.3.1. How Iranian SMEs use E-commerce internationally?....................................................41. 4.3.1.1 4.3.1.2. 4.3.2 4.3.3. Functional sophistication .................................................................................................... 41 Cultural adaptation.............................................................................................................. 45. Why Iranian SMEs use E-commerce internationally? ....................................................45 How use of internet affects perception of export barriers? ............................................48. 4.3.3.1 4.3.3.2. Export barriers .................................................................................................................... 48 Internet affects on export barriers ....................................................................................... 52. 5 CHAPTER FIVE – CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FURTHER RESEARCHES .....................................................................................................................................53 5.1 INTRODUCTION.....................................................................................................................53 5.2 CONCLUSIONS FROM THE STUDY ..........................................................................................53 5.2.1 Conclusions regarding the first research question .........................................................53 5.2.2 Conclusions regarding the second research question ....................................................53 5.2.3 Conclusions regarding the third research question........................................................54 5.2.4 Conclusions regarding the whole study..........................................................................54 5.3 SUGGESTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCHES .............................................................................55 REFERENCES...................................................................................................................................…56 APPENDICES. Appendix A : questionnair Appendix B: Factor analysis.

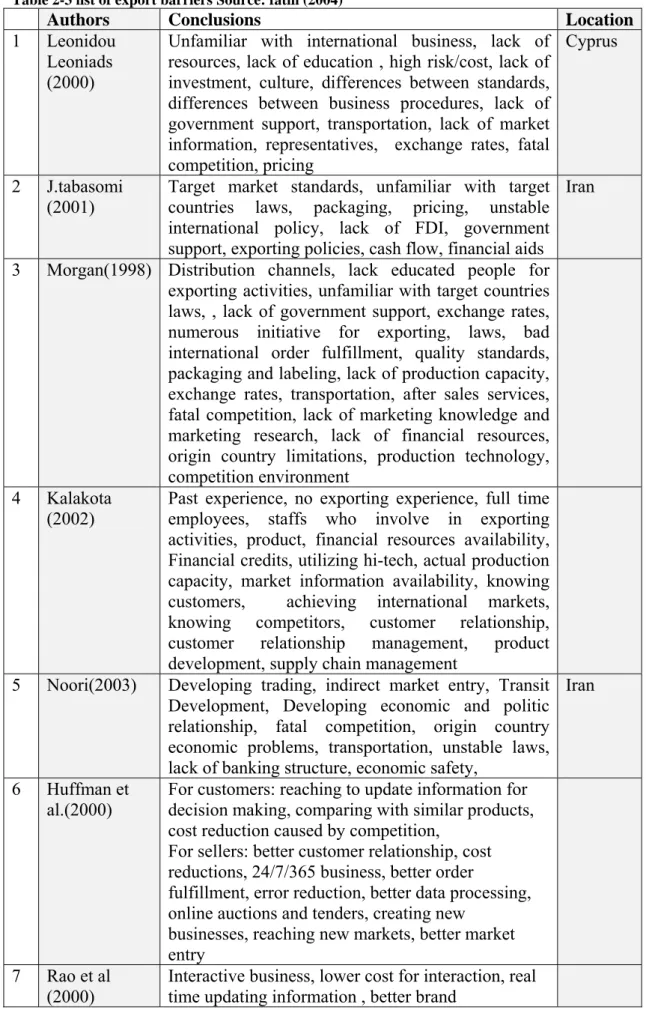

(6) List of Tables TABLE 1-1 ACTIVE SMALL FIRMS IN IRAN .................................................................................................5 TABLE 1-2EXPORT BARRIERS AS PERCEIVED WITH DIFFERENCES BETWEEN SMES WITH WEBSITES AND SMES WITH OUT -WEBSITES. .........................................................................................................11 TABLE 2-1 METHODOLOGIES, SAMPLE SIZES AND FRAMES, DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS TECHNIQUES USED .........................................................................................................................15 TABLE 2-2 BARRIERS TO SMES EXPORT ENGAGEMENT. .........................................................................24 TABLE 2-3 LIST OF EXPORT BARRIERS .....................................................................................................25 TABLE 3-1 RELEVANT SITUATIONS FOR DIFFERENT RESEARCHES............................................................29 TABLE 4-1NUMBER OF EMPLOYEES BY TWO GROUPS ..............................................................................33 TABLE 4-2 YEARS OF WEBSITE USING BY TWO GROUPS ...........................................................................34 TABLE 4-3 COMPARING TWO GROUPS THROUGH PRODUCTION TYPE .......................................................35 TABLE 4-4 FIRMS WORK EXPERIENCE IN EACH GROUP ............................................................................36 TABLE 4-5 FIRMS INTERNATIONAL ACTIVITIES........................................................................................37 TABLE 4-6 FIRMS’ INTERNATIONAL ACTIVITIES FOR EACH GROUP ..........................................................38 TABLE 4-7 SALES VOLUME OF EXPORTING ..............................................................................................38 TABLE 4-8 PRODUCTION VOLUME OF EXPORTING ...................................................................................38 TABLE 4-9 TARGET MARKETS FOR EACH GROUP .....................................................................................40 TABLE 4-10 MARKETING PLAN FOR EACH GROUP ...................................................................................40 TABLE 4-11 FIRMS USING THEIR WEBSITES AS "BROUCHURE WARE" ......................................................41 TABLE 4-12 MARKETING AND ADVERTISEMENT .....................................................................................41 TABLE 4-13 FIRMS USE WEBSITE FOR MARKETING AND INFORMATION ...................................................42 TABLE 4-14NUMBER OF WEB SITES HAVE COMMUNITY AND COMMUNICATION TOOLS ...........................42 TABLE 4-15 ACCEPTING ORDERS THROUGH WEBSITE ..............................................................................42 TABLE 4-16 RECIEVING PAYMENTS .........................................................................................................42 TABLE 4-17 ACCEPTING CUSROMIZED ORDERS .......................................................................................43 TABLE 4-18 RELATIONSHIP .....................................................................................................................43 TABLE 4-19 CULTURAL ADAPTATION .....................................................................................................45 TABLE 4-20 CULTURAL ADAPTATION VS CUSTOMER TYPE CROSS TABULATION ...................................45 TABLE 4-21 FACTORS FOR USING WEBSITE..............................................................................................46 TABLE 4-22 REASONS USING WEBSITE BY IRANIAN SMES ......................................................................47 TABLE 4-23 KMO AND BARTLETT'S TEST ..............................................................................................48 TABLE 4-24 PERCEPTION OF EXPORT BARRIERS BY IRANIAN SMES ........................................................49 TABLE 4-25 VARIMAX ANALYSIS OF PERCEIVED EXPORT BARRIERS AMONG IRANIAN SMES..................51 TABLE 4-26 MANN-WHITNEY U TEST .....................................................................................................52 TABLE 4-27 DIFFERENCES IN COMBINED ATTITUDE SCORES....................................................................52 FIGURE 1-1 VALUE OF EXPORTING GOODS BETWEEN 1376-1383 ..............................................................5 FIGURE 2-1 MODEL OF SME INTERNATIONAL E-COMMERCE. .................................................................27 FIGURE 4-1-NUMBER OF EMPLOYEES......................................................................................................33 FIGURE 4-2- YEARS LAUNCHED WEBSITE BY FIRMS…………………………………………...……….34 FIGURE 4-3 PRODUCTION TYPE IN WHOLE SAMPLE ..................................................................................35 FIGURE 4-4 FIRMS WORK EXPERIENCE IN WHOLE SAMPLE .......................................................................36 FIGURE 4-5 FIRMS WORK EXPERIENCE IN WHOLE SAMPLE .......................................................................37 FIGURE 4-6 TARGET MARKET FOR WHOLE SAMPLE ................................................................................39.

(7) To my Father and Mother.

(8) Chapter 1- Introduction and research problems. 1 Chapter one-Introduction and research problem 1.1 Introduction The world is changing dramatically. Government-imposed barriers and structural impediments, which segmented and protected domestic markets, are falling rapidly, while technological advances in production, transportation, and telecommunications especially internet allow even the smallest firms access to customers, suppliers, and collaborators around the world. Economic growth and innovation, both domestically and internationally, are fuelled increasingly by small companies and/or entrepreneurial enterprises. These trends will impact profoundly on management strategies, on public policies, and on the daily lives of all of us. Studies have shown that small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have embraced E-Commerce to strengthen their competitive position. In the case of SMEs engaging in export activities, the Internet is supposed to be useful in reaching out to International markets. As stated above, the immediate goal for any small to medium-sized enterprise (SME) is to survive and maintain its independence. But, sooner or later, a small company will probably want to expand. With the trends towards global convergence and the adoption of outsourcing by firms of all sizes, growth usually means entering the international market. The transition from a small domestic firm to an established and committed international company is a major step for any SME. Internationalization throws up a number of challenges for managers of such firms. The twin phenomena of globalization and e-commerce pose new challenges and provide new competitive opportunities for large and small firms alike. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs), in particular, are only beginning to embrace these new opportunities. Although they account for more than half the employment and added value in most countries, SMEs do not contribute proportionately to export trade (UNCTAD, 1993). The main barriers to exporting faced by SMEs include the lack of capital and capacity, and the general complexity of serving overseas markets (UNCTAD, 1993).. 2.

(9) Chapter 1- Introduction and research problems. 1.2 SME's definition Many researchers identified quantitative criteria for defining small and medium sized enterprises. From this point of view SME refers to companies in all industries as long as a given sized is not exceeded. Economic propose indicators, such as profits, invested capital balance sheet total, earnings total capital market position, production and sales volume, and number of employees and turn over. In order of simplifying and compatibility and practical application "number of employees" and "turn over" are two factors that most recommended for quantitative area. In 1996 the European Union (EU) set the following ranked criteria for defining SMEs: 1. less than 250 workers 2. a maximum of 40 million euros annual turn over 3. a maximum 27 million euros annual balance sheet 4. minimum of 75% of company assets owned by company management 5. owner managers or their families manage the company personally It is obvious these limited factors are differing from country to country.. 1.3 Internationalization definition Internationalization is a continuous process of choice between policies which differ maybe only marginally from the status quo. It is perhaps best conceptualized in terms of the learning curve theory. Certain stimuli induce a firm to move to a higher export stage, the experience (or learning) that is gained then alters the firm’s perceptions, expectations and indeed managerial capacity and competence; and new stimuli then induce the firm to move to the next higher export stage, and so on (Cunningham and Homse, 1982, p. 328) This definition of internationalization concerns the exporting firm but early internationalization theory focused mainly on the international activities of the Multinational enterprise or corporation (Ayal and Zif, 1979; Beamish and Banks, 1987). Internationalization has been used to describe the outward movement in an Individual firm’s or larger grouping’s international operations (Johanson and Vahlne, 1977; Piercy, 1981). Welch and Luostarinen (1988) interpret it as the process of increasing involvement in international operations while Steinmann et al. (1980) note that existing frameworks describe the process as scaling up the strategy-ladder of internationalization. Johanson and Wiedersheim-Paul (1975) noted that although the majority of research tends to centre on the multinational firm, a large number of smaller firms are involved in international activities and continue to grow over time in stages or phases: . . . we have several observations indicating that this gradual internationalization, rather than large, spectacular foreign investments, is characteristic of the internationalization process of most Swedish firms. It seems reasonable to believe that the same holds true for many firms from other countries with small domestic markets (Johansson and Wiedersheim-Paul, 1975, p. 305).. 3.

(10) Chapter 1- Introduction and research problems. 1.4 E-commerce definition By many previous researches and also some organizations e-commerce is a business activity conducted using websites on internet. This is a subset of e-commerce as defined by OECD: "all business occurring over network using the transmission control protocol/internet protocol(TCP/IP) "(OECD,1998). Also some researchers defined e-commerce as a subset of e-business activities that take the financial activities of the business and its related information, as Khalifa(2003) define e-commerce: "Sharing business information, maintaining business relationships and performing business transactions by electronic means.". 1.5 Operational definitions 1.5.1 Internationalization Based on definitions mentioned in this chapter and regarding the Iranian SMEs situations we define internationalization as an action that firm willing to export their products and services and also the process of expanding their business activities into foreign markets.. 1.5.2 Small and medium sized enterprises in Iran Since 1995, when the first "economic development plan" was launched in Iran, industries were divided in two groups small firms large industries While small firm were private and the large firms belong to the government and defined as enterprises with more than 500 employees (according to the development plan). With respect to the lack of information about the small and medium sized firms and the problems of accessibility to the correct data and regarding to definitions of SME in this study we limited the factors to the "number of employees" meanwhile, regarding to lack of definition for medium sized firms we define maximum 250 employees as the upper limit for medium sized enterprises.. 1.5.3 E-commerce definition Regarding to definition of e-commerce that mentioned before, most of the firms use internet and their web sites as a brochure and they use their web sites to share information with their customers due to lack of electronic payment in Iran. In this research we define e-commerce as business activity such as getting orders or providing information by electronic means such as e-mail or web site.. 4.

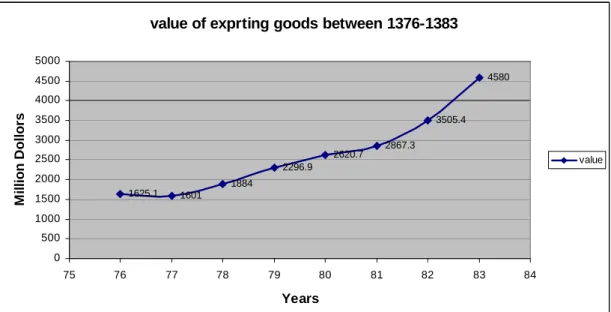

(11) Chapter 1- Introduction and research problems. 1.6 General domestic environment 1.6.1 Iranian exporter SMEs SMEs are of crucial importance to the Iranian economy and are export trade. From 1375 (1995-1996) to 1384 (2004-2005), the total value of Iran's exporters grew from $1625.1 million in to $4580 million. The increase in the volume of exports was 16% per year. Figure 1-1 shows the increase in exports among firms which not included in oil and gas industry. Figure 1-1 Value of exporting goods between 1376-1383 Source: Iran census center. value of exprting goods between 1376-1383 5000 4580. 4500. Million Dollors. 4000 3500. 3505.4. 3000. 2867.3. 2620.7. 2500. value. 2296.9. 2000. 1884 1625.1. 1500. 1601. 1000 500 0 75. 76. 77. 78. 79. 80. 81. 82. 83. 84. Years. 1.6.2 Iranian SMEs Table 1-1 shows the number of small firms categorized by the number of employees. Table 1-1 Active small firms in Iran source: ISIPO 2005. Number of firms up to 50 persons 62088. Number of firms more than 50 persons 4658. Total 66746. This table shows the 93% of small firms has less than 50 employees, so the operational definition for small enterprises is firms fewer than 50 employees.. 1.7 Research propose In view of above discussions, the propose of this study is: "To gain better understanding on impact of e-commerce on small and medium sized internationalization in Iran" Due to lack of studies about internationalization of SMEs and lack of published studies from this point of view (e-commerce) we conduct this study among Iranian SMEs which get the exporting bonus from ministry of commerce.. 5.

(12) Chapter 1- Introduction and research problems. 1.8 Problem discussion SMEs has central role in industrial sector in Iran, radical changes in business environment and joining domestic business to global business and lack of academic studies about internationalization of SMEs and ecommerce affects lead us to selection of this area of research. Also small and medium sized enterprises always wish export their products but always face with some barriers, and this research is going to show if SMEs can overcome these barriers through e-commerce. As stated, we will attempt to clarify propose of this study (To gain better understanding on impact of e-commerce on small and medium sized internationalization in Iran) through investigating these issues: 1. the factors influence SMEs to use e-commerce internationally 2. how use of the Internet affects perception of export barriers So the research problem regarding would be: “To describe and discuss e-commerce and internationalization of Iranian SMEs. 1.9 Management behaviors and using e-commerce internationally Studies on SME exporting highlight the importance of management behaviors to performance (e.g., see Leonidou et al., 1998 for review). The categories used to assess these behaviors range from the general to the specific that is from the overall orientation of firm managers to their strategic or marketing initiatives. In this study, we focus on three aspects of international e-commerce behaviors: the level of management commitment to its use as an export tool, the function and content of the web page, and the degree to which firms adapt their e-commerce efforts to foreign markets. The first dimension of international e-commerce use — the level of management commitment — is derived from the extensive literature on SME internationalization (e.g., Leonidou et al., 1998; Coviello and McAuley, 1999). This work recognizes the importance to exporting of commitment, the degree of ‘‘deliberate interest in and allocation of financial and human re sources to developing and serving foreign markets’’ (Le onidou et al., 1998). Researchers have consistently found that such levels of commitment are positively associated with export performance (Leonidou and Katsikeas, 1996; Cavusgil, 1984; Cavusgil and Kirpalani, 1993; Beamish et al., 1993). The importance of this factor to exporting reflects the fact that it is not enough for firms to have a good exporting plan; it is necessary to devote the resources necessary to follow through and properly execute it. A second, more specific dimension of international e-commerce use arises from the emerging practitioner and academic literatures on the commercial use of the Internet. This body of work has identified three levels of web functions. In order of sophistication, these are the provision of information or ‘‘brochure ware,’’ providing customer service and information, and conducting on-line transactions (Ho, 1997; Seybold, 1998).1 A fourth level is practiced by web-enabled or ‘‘Internet-based’’ businesses, which comprise portals such as Yahoo.com, market-makers such as Ebay.com and product/service providers such as Amazon.com (Mahadevan, 2000). These differences in how firms deploy web-based initiatives highlight the range of e-commerce activities that can be practiced by SMEs. The third aspect of e-commerce use arises from the international marketing literature. Whether firms should adapt their. 6.

(13) Chapter 1- Introduction and research problems marketing mix to different markets or offer standardized product or service programs has long been the source of considerable debate (Levitt, 1983; Jain, 1989; Cavusgil et al., 1993; Shoham, 1999). The case for adaptation is based on the alleged persistence of culture-based market differences, such as consumer and manager characteristics and legal environments (Cavusgil et al., 1993; Shoham, 1999). The proponents of standardization claim that world market characteristics are converging, thereby allowing firms to reap economies of scale by offering similar product, promotion and distribution mixes across the world markets (Levitt, 1983). The Internet reinvigorates this debate because a website potentially becomes a global advertisement the moment it goes live. In this study, we focus on a narrow aspect of adaptation: the offering of web page content and e-mail communication in the languages of target markets. Therefore with respect to the three dimension, management commitment, web functions and adapting marketing mix, we formulate the first research question regarding the way that SMEs use e-commerce internationally. So the first research question is: "How are Iranian SMEs using e-commerce internationally?". 1.10 Environmental factors and their roles to use e-commerce Internet technology is changing business environments in many ways. Economic perspectives of the firm highlight the most obvious effects, those related directly to the markets in which the firms operate (tiessen2002). A second perspective, informed by institutional theory (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983; Oliver, 1991), highlights how social factors, notably industry norms, influence firm behaviors.. 1.10.1. Economic perspectives. Taken together, two broad theories of economic competition, bas ed respectively on industrial organization (IO) and Schumpeter’s work on innovation, help us nderstand the uncertainty introduced to markets by the Internet (Barney, 1986). The IO view, exemplified by Porter (1985), draws attention to three ways the Internet disrupts markets (Sahlman, 1999; Evans and Wurster, 1999). First, it alters the relative power of buyers and suppliers, as well as those in the middle, by lowering the cost of finding and distributing market information (Mahadevan, 2000). Further, the spread of information through e-commerce enables more firms to offer substitute goods and services. Finally, the rush to stake out ‘‘cyber-territory’’ is creating vigorous rivalry in Internet-related markets. These factors a re changing the competitive landscape, and the final outcomes are not yet clear. Though published in English more than 60 years ago, Schumpeter’s (1961) description of the process of ‘‘creative destruction’’ as the engine of capitalism resonates today. This process highlights how revolutionary ‘‘new combinations’’ of technologies and markets disrupt economic equilibrium and contribute to growth. Schumpeter’s view captures the idea that, while this process offers opportunities to innovators and adaptors, it also threatens established businesses. The Internet is associated with all five types of innovation, which Schumpeter described: the web is a new product itself, which facilitates new production methods, opens up markets, and offers access to more suppliers and potentially fragments or concentrates industries. Firms operating in industries characterized by such changes face high levels of competitive uncertainty (Porter,. 7.

(14) Chapter 1- Introduction and research problems 1985; Barney, 1986). In addition to market structure and disequilibrium, another economic factor associated with commitment to exporting is the attractiveness or munificence of the market. Firms will take steps to internationalize their marketing approaches if it is seen as economically worthwhile. This is a special concern for SMEs, which may lack the resources to deal with, or even supply, all the possible markets available to them. For example, in this study, a firm may only wish to exports its products to middle east countries so they translate their site in Arabic or and language their customers can communicate.. 1.10.2. Industry norms. Organizations do not, however, act solely in response to economic factors. Rather, they often follow ‘‘collective norms,’’ leading to ‘‘homogeneity in structure, culture and output’’ (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983, p. 147). DiMaggio and Powell (1983), in their seminal work, attribute these tendencies to three institutional influences, all salient in the case of Internet use by SMEs. Less able to shape their environment than larger firms, SMEs are compelled generally to ‘‘acquiesce’’ (Oliver, 1991) in response to these influences. The first mechanism unfolds as a firm reacts to environmental uncertainty by imitating the actions of others in their markets. Typically, a company models itself after organizations it perceives as successful or trend setting. This process is especially relevant to Internet use. The market dynamism and uncertainty introduced by the technology compels SMEs to follow leading firms and use the web because this technology is likely to reshape industries, though the firm may not precisely know how (Kassaye, 1999). The second mechanism related to norms is ‘‘coercive.’’ This describes situations in which organizations upon which a firm depends demand that it act in certain ways. In the case of e-commerce, customers, rather than regulatory authorities, typically wield influence. The potential for these buyer demands in the e-commerce realm is considerable, as illustrated by the decisions of Ford and General Motors to move all of their procurement — worth hundreds of billions of dollars — to the Internet (Carroll, 1999). These initiatives will force suppliers to adopt e-commerce practices if they plan to continue serving these important customers. The third institutional factor arises because firms need legitimacy in their business markets. DiMaggio and Powell (1983) offer the example of professionalism, the effort to establish standards of practice and legitimacy in an occupation. The concept of legitimacy is important in the realm of e-commerce because the relevant technologies are both new and sophisticated. Could a computer company that lacks a website, for example, be considered a legitimate player in the minds of potential customers or investors.. 1.10.3. Firm Factor. The resource view of the firm, which focuses on the importance of its unique assets (Barney, 1991; McDougall et al., 1994), offers an overview of firm factors associated with levels of commitment to international e-commerce by SMEs. Two capabilities especially relevant to international Internet use are computer competence and cultural expertise. Other firm factors include the size of the firm, and whether the firm’s products reach final buyers through intermediaries or by direct sales. An information systems perspective helps explain how the level of computer skills in a business 8.

(15) Chapter 1- Introduction and research problems affects its use of e-commerce. Research in this field has found that three factors — perceived ease of use and usefulness, task-technology fit and experience using technology —are linked positively to the use of new technologies (Davis, 1989; Davis et al., 1989; Dishaw and Strong, 1999). The implication for this study is that SMEs will use Internet technology for international activities if the employees have sufficient technical skills, and if they view the technology as useful. Further, Dishaw and Strong (1999) suggest that these conditions are related: the perceived usefulness will be linked to the technical capability of those in charge of managing Internet initiatives. The instant global reach of the Internet also invokes the potential need for cultural capabilities, especially language skills. Analogous to technical capability, cultural capabilities enable firms both to adapt their promotion mixes to foreign buyers, and to become aware of the opportunities that justify this effort. This view is supported by research demonstrating that foreign language skills and overseas experience are linked to exporting and to success in foreign markets (McDougall et al., 1994; Leonidou et al., 1998; Reuber and Fischer, 1997). More generally, the overall availability of resources, especially employees and capital, is associated with international e-commerce. In contrast, larger firms have found that exporting is related positively to firm size, though the tie is not very strong (Bonaccorsi, 1992; Calof, 1994). With respect to this study, it is clear that smaller companies will not always be able to acquire — on a contract basis or in-house — the dedicated expertise required to execute e-commerce strategies. Larger firms are more able to risk committing resources to innovations, such as implementing websites. Further, larger companies will be more likely to be able to bear the costs, such as search and negotiation, associated with directly conducting business abroad (Williamson, 1985; Peng and Illinitch, 1998). The last influential firm factor is what we label ‘‘business relationships,’’ or a firm’s place in and use of distribution channels. There are two broad issues here. The first is the degree to which firms are dependent on distributors, especially in foreign markets. In general, firms that sell products with more ‘‘commodity content,’’ especially those with limited pre- and after-sales service, are more able to use intermediaries, because transaction costs are lower (Peng and Illinitch, 1998). In contrast, firms selling more complex products are more engaged in direct relations with final users (Peng and Illinitch, 1998). A second, overlapping set of issues is associated with differences between business-to-business (B2B) and business-to-consumers (B2C) markets. B2B firms also typically deal with more complex transactions with fewer, but typically more direct, interactions with customers. These factors, environmental factors and firm factors, meanwhile respecting the theoretical framework that mentioned above we formulated the second research question as below: "Why are Iranian SMEs using e-commerce internationally?". 1.11 Small and medium sized enterprises and export barriers Theoretically, exporting SMEs should have a higher propensity for Internet uptake (Glen Hornby, 2002). Devins (1994) identified that successful SMEs had certain innovative activities, which included exports. Hence if SMEs who are more innovative are more likely to take up exporting, they are probably more likely to take up new technologies such as the Internet. Poon and Swatman (1997) identified that businesses with localised markets do not gain as much benefit from such factors as 9.

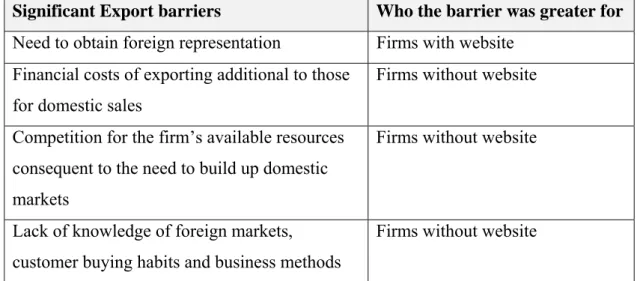

(16) Chapter 1- Introduction and research problems low cost communication or widened corporate exposure as businesses with wide geographic consumer base. It is logical extension then, to suggest exporters or international traders have a lot to gain from the use of the Internet. Traditionally, small businesses wishing to export face a number of internal and external obstacles (Hamill,1998; Hamill and Gregory, 1997; Julien, Joyal, Deshaies, Ramangalahy, 1997; Leonidou, 1995a; Bennett, 1997, Bennett, 1998). Leonidou (1995b) suggested that fear of intense competition in foreign markets was the biggest barrier to export activity, with attitudes towards risk and innovation also being important. The research confirmed Previous research by Dicht et al. (1990) that psychic distance from the foreign markets greatly affected firms export activities. Hamill and Gregory's (1997) work identified four main categories of barriers to export activities Small business has traditionally had a lack of resources, which has created barriers to international trade (Khoo, McGill, Dixon, 1998; Lefebvre E., Lefebvre L., Prefontaine., 1999), the growth of the Internet may allow SMEs to compete in the global business environment (Khoo et. al, 1998; Kandasaami, 1998; Lefebvre et. al., 1999). Lefebvre et. al. (1999) examined the role of technological capabilities in the internationalization of SMEs, focusing only on R&D intensive firms, and posed that because competition is increasingly technology based, firms’ technology capabilities would play a major role in determining a firm’s propensity to export. Khoo (1997) also suggests that small exporters are able to compete in foreign markets because of their technological capabilities. A study (Bennett, 1997) into the experiences of web site use and perceptions of export barriers among UK businesses, found barriers to exporting may become considerably lessened by the use of the Internet. The study included a sample who did and did not possess a website, enabling a contrast between the severity of export barriers perceived by the two groups. A number of major barriers (3.95 or higher in a likert scale of 5), existed for all businesses: 1. transport problems 2. documentation problems 3. exchange rates 4. import restrictions Table (1-2) presents the findings of significant differences between the barriers faced by firms with websites, and firms without websites. Note that three out of the four barriers where significantly higher (to a p < 0.05 level) for firms who did not own a website, and each can be linked to resource shortages that are experienced by SMEs.. 10.

(17) Chapter 1- Introduction and research problems. Table 1-2Export barriers as perceived with differences between SMEs with websites and SMEs with out -websites. Source: Bennett, 1997. Significant Export barriers. Who the barrier was greater for. Need to obtain foreign representation. Firms with website. Financial costs of exporting additional to those. Firms without website. for domestic sales Competition for the firm’s available resources. Firms without website. consequent to the need to build up domestic markets Lack of knowledge of foreign markets,. Firms without website. customer buying habits and business methods There were also findings suggesting that businesses who had their own website felt less psychic distance from foreign markets and were less concerned with resource constraints (Bennett, 1997). Causal effect was not established between this and perceptions of export barriers, though the finding could imply a generally more progressive and innovative attitudes towards exporting than found in non-web site owning businesses. This supports the role of innovative attitudes as a major factor in SMEs overcoming barriers to export and E-commerce adoption. A firm that owns a website has had the resources and attitude to overcome the barriers to SME ECommerce uptake, thus it could be suggested that a predominant “progressive” attitude may also be what enabled the firms to overcome the barriers to exporting. Generally, exporters held favorable views of the Internet's contributions to the facilitation of export. Internet use was regarded especially valuable for generating sales leads, helping the firm sell in remote countries, penetrate unfamiliar markets, create international awareness of the enterprise, and avoid having to bother with foreign cultures and business practices. A follow-up study by the same author (Bennett, 1998) comparing the perceptions of British and German firms using the WWW for international marketing (Bennett, 1998), found that the Internet: . Helps firms sell anywhere in the world no matter how remote the country Avoids the need to bother about foreign cultures and business practices Avoids having to obtain foreign representation. The findings suggested that the Internet “avoids having to obtain foreign representation” was intriguing since in the earlier study (Bennett, 1997) firms with websites saw the need to obtain foreign representation as a significantly higher barrier than those without websites - while the later study (Bennett, 1998) concluded that using the Internet avoids having to obtain foreign representation (Glen Hornby, 2002). If the Internet can truly deliver on its promise (or potential) to be able to access a “global market”, then it would be assumed that this barrier would be more redundant for firms with a website. Bennett (1998) found German respondents significantly less concerned about foreign representation and understanding foreign languages. From analysis, Bennett (1998) concluded German exporters were more ethnocentric in their approach to export business. 11.

(18) Chapter 1- Introduction and research problems The intriguing result between the need for foreign representation and the use of websites needs further investigation. The examination of the export philosophies taken by firms may be able to help us understand this relationship, since the need for foreign representation is intrinsically linked to the way a business deals with foreign cultures and business practices. The role of foreign representation is to give the export business a local adviser, who is familiar with the local cultures and business practices. The 1998 study by Bennett pointed towards the need of further examination of export philosophies, which may be able to give further explanation of confounding results. Computer interface literature has suggested cultural and language differences impact on website interface design (Takasugi, 1999; Murrell, 1998; Vassos, 1996; Andrews, 1994; Russo and Boor, 1993). Meanwhile, export philosophies taken by SME exporters; face many barriers and internet seems can be a perfect tool to overcome these barriers so the third research questions would be: "How use of internet affects perception of export barriers?". 12.

(19) 2 Chapter Two- Literature review 2.1 Introduction In this chapter based on a thoughtful and critical review of related, we aim at building a theoretical framework for research questions and research problem. This chapter shows that this research does not duplicate what others have already done. The main propose of this chapter is to review internationalization among SMEs all around the world that related to our problem area. Therefore, we aim at conducting a systematic search for reviewing following disciplines: • internationalization literature and export philosophies • internationalization of SMEs • previous studies on "e-commerce and exporting SMEs" • previous studies on "export barriers for SMEs". 2.2 Literature Review A review of the internationalization literature was carried out in order to determine factors such as the research methodology adopted, including the data collection and analysis technique, the particular internationalization topic under investigation, the country of origin of the study and firm size in order to identify dominant methods of investigation and knowledge gaps. Table 1 contains a representative sample of works connected with internationalization spanning the past number of decades, beginning with the key work from the Uppsala school in the 1970s (Johanson and WiedersheimPaul, 1975; Johanson and Vahlne, 1977). The nature of the subject and the fact that articles tend to be published in a diverse fashion make the process of analysis difficult. However, this review is intended as a survey of the current state of knowledge in internationalization and not as a review of the entire population of works. The journals range from specific publications concerning international marketing to more general works dealing with management and business issues relating to the small and medium sized firm. The journals consulted can be divided into four main groups: a- those concerned with international business and marketing; b- Marketing journals with no main international outlook; c- Small business management; and d- Those of a general business orientation. A survey of the research methodologies, sample sizes and sampling frames, data collection and analysis techniques show the range of procedures in use and highlight.

(20) Chapter 2- Literature Review preferences for one method over another. In order to form solid conclusions requires a truly cross-cultural approach, ideally tracking problems longitudinally. However, constraints in the research methods used, such as the time available and associated costs, result in studies which tend to be short term in focus and applied to country specific situations. The methodologies have an overall quantitative slant and it has been noted that in order for theory to progress in a meaningful way, an increased qualitative input could prove useful. Many of the empirical works tend to be replicate and some do not fully justify their choice of methodology and use of a particular statistical approach. Quantitative works dominate the literature, although conceptual studies, literature reviews and discussions are also reasonably well represented. However, there is a drastic shortfall in the number of truly qualitative studies, although a number of works do involve either some qualitative interpretation of the data or endeavor to conceptualize and model using some qualitative input. The case study method is also underrepresented: this can either utilize quantitative or qualitative data collection and analysis, or both, and has the benefit of adopting a longitudinal approach. This longitudinally tends to be lacking in the other approaches, although some studies have compared data collected over various time periods. Investigating the country of origin of the studies shows a shift from North America in the early 1970s. This spreading out of internationalization research has resulted in the questioning of the conceptualizations and empirical results of the American studies. Models developed so far cannot be generalized and tend to only fit into specific country situations. There is still an overemphasis on North American studies. However, it can be noted that there is also a reasonable body of work involving the assessment of primary and secondary data from a number of other countries. The UK has a fairly strong research representation, followed by Canada. Although this survey indicates that the study of internationalization is reasonably widespread, its state of envelopment is fairly immature in most countries. There are variations in the degree to which data is analyzed; some studies utilize descriptive statistics while others spend some time on factor analyzing the data. Either approach can produce equally valid results but ultimately, the figures must be interpreted qualitatively and the experience of the researcher and the associated degree of subjectivity must be taken into account. The dominance of the quantitative method serves to slow down new theory generation and, in a climate where more and more smaller firms are internationalizing than ever before, there is a need for a range of alternative methodologies in order to try to understand such behavior. Many of these smaller firms exhibit behavior where traditional stages of internationalization are omitted, entering international markets almost instantly.. 14.

(21) Table 2-1 Methodologies, sample sizes and frames, data collection and analysis techniques used Source: Ian Fillis 2001. Methodology. Author. Are discussion. Case study. Coviello and Munro (1995). Networking and the entrepreneurial firm internationalization of the firm Internationalization of the firm: two cases in the industrial explosives industry. New Zealand. SME. Sweden. Grow the from SME to large Grow the from SME to large. Stability an d profitability o f international joint ventures. Japan, Caribbean and US A. MNE. Turpin (1993). Strategic alliances Japanese firms. Japan and USA. Large. Boter and Holmquist (1996 ). Industry characteristics and small firm internationalization. Norway, Sweden and Finland. SME. Shaughnessy (1995). International joint ventures. Multi country. Range of size. Johanson and Vahlne (1977 ). A model of know ledge development and foreign market commitment. Sweden. Growth small to large. Welch and Luostarinen (1988 ). Evolution of internationalization concept. Generalization. Firm level. Johnson and Wiedersheim-Paul (1975) Whitelock and Munday (1993). Beamish (1995). Conceptualization , modeling and frameworks. and. Inkpen. under Country of origin Company of the study size. with. Britain Sweden. Data collection techniques. and. an. analysis. In -depth interview s with key decision makers and mail survey o f other firms in same industry Construct ion of establishment profiles of firms Analysis by behavioral approach of Uppsala model and the rational-economic eclectic paradigm. Discussion of reasons why some joint ventures thrive while others are unstable, using data from a number of sources including case study, longitudinal study, field interviews Analysis of case studies - Borden Inc. and Meiji Milk Product s Co., General Electric’s joint ventures, Sumitomo 3M Exploratory case study approach, focusing on management styles in conventional and innovative firms. from. Investigation of problems encountered in international joint ventures using three case studies Model based on empirical observations in international business, focusing on gradual acquisition, integration and use of knowledge about foreign markets and operations and on increasing commitment to foreign markets Dimension s of internationalization, hypothetical comp any comparison , determinants of forward momentum.

(22) Chapter 2- Literature Review. Methodology. Author Wiedersh eim-Pau Olson and Welch (1978 ). Literature review or discussion. Are discussion l,. under Country of origin Company of the study size. Data collection and an analysis techniques. Pre-export activity: the first step in internationalization. Australia. Majority firms with < 200 employees. Eroglu (199 2). Internationalization process of franchise system s. USA. Franchises. McAuley (19 93). Perceived usefulness of export information source s. United Kingdom. Small < 50, large > 50 employees. The export assistance model. Cavusgil and Zou (1 994). Marketing strategy performance relation ship and the empirical link in export ventures. USA. Average n umber of employees = 1000, average annual sales = $200m. Conceptual framework of export marketing strategy and performance. Walters and Samiee (19 90). Mod el for export performance. USA. Small firms. Formulation of model following validation of questionnaire data by factor analysis ± principle components analysis, varimax rotation, t-tests, chisquare tests and stepwise multiple regression analysis. Miesenbock (1988). Small businesses and exporting. Multi country. SME. Compiling, systematizing and comparing empirical studies. Abby and Slater (1989). Review of empirical literature concerning management influences on e xport performance. Multi country. Range of sizes. Describes an integrative mo del of export performance, classifying results of export research (1978 -88 ) to model parameters. assessing. of. De velopment of model c oncernin g the imp ortance of a firm’s activities and pre-exp ort beha viour following a nalysis o f ``traditio nal’’ resea rch and mo re re cent d evelo pmen ts in locatio n theor Mod el of the d etermina nts of franchise internatio na liza tion. 16.

(23) Chapter 2- Literature Review. Methodology. Author. Are discussion. Chetty and Hamilton (1993) Thomas and Araujo (198 6). Firm-level determinant s of export performance Analysis o f export behavior theories. Multi country. Range of sizes. Multi country. Growth of the firm. Johanson and Vahlne (1990). Mechanism of internationalization. Multi country. Growth of the firm. Bilkey (19 78). Review of literature on export behavior Review of contemporary empirical re search. 11 country review. Range of sizes. Multi country. SME. Empiric al research on export barriers Difference s among exporting firms based on degree of internationalization. American o r European. Range of sizes. USA. Style s an d Ambler (1994). Successful export practice. Unite d Kingdom. Sa les of < $10m, between $10m an d $100m, > $1 00m W inners o f 1992 Queen’s award for export achievement. Katsikeas and Morgan (1994). Difference sin perceptions of exporting problems based on firm size and export market experience. Greek. Coviello and McAuley (1999) Leonid ou (1995) Quantitative studies. Cavusgil (1984). under Country of origin Company of the study size. Smaller < 100 , large r > 10 0 employee s. Data collection and an analysis techniques Assessment of knowledge of influences on export performance b y meta-analysis Examination of theories of export behavior ± models developed by Johanson and Vahlne , Wiedershe im Paul, Bilkey and Tesar, Cavusgil and Nevin, Reid Description and discussion of the mechanism of the internationalization process and contrasts mad e with the eclectic theory Review of 4 3 studies involving 11 countries subdivided into topic areas Review of 1 6 articles from 1989 to 19 98 in international al business and small business / entrepreneurship areas Review, assessment and synthesis of empirical research concern in g exp ort barriers Personal interviews with executives mainly responsible for international business activities of firm, semi-structured data collection instrument, tape recorded interview Collection b y questionnaire. Data an analyzed by rank, mean standard deviation , t-test and goodness of fit test. Key informant technique, principal components analysis, hypotheses testing, test for significant differences, t-test. 17.

(24) Chapter 2- Literature Review. Methodology. Author. Are discussion. Barrett and Wilkinso n (1985). Export stimulation and exporting problems. Australia. Small, medium an d large. Barker and Kaynak (1992). Difference s between initiating and continuing exporters Ex port behavior of firms and ex porter profile s. Canada. Small and medium-sized. USA. SME. Exp ort market research orientation s. Turkey. Small = sales of<$ 500,000, medium = sales between $500,000 and $5m. Personal and organisational determin ant s of export trade activities Contextua l fa ctors affec ting cross-c ultural relatio nship suc cess. Australia. Companies with 50 ± 1000 employee s Medium-sized. Questionnaire data analysed by stepwise regression analy sis, de velopme nt o f causal analytical model. Fillis (2 000b). Internationalization process of the smaller craft firm. United Kingdom a nd Republic of Ireland. Microe nterprise focus. 30 in-depth interviews w ith own er/man agers fo llow ing larger scale p ostal survey. McA uley (1999). Entrepreneurial in stant exporters in crafts sector. Scotland. Microe nterprise focus. 15 in-depth interviews w ith own er/man agers fo llow ing larger scale p ostal survey. Cavusgil, Bilkey Tesar (1979) Bodur (1985). and. and. Cavusgil. Holzmuller and Kasper (1 991). Qualitative works, either stand alone ; or as part of mixed me technology. Kanter and Corn (199 4). under Country of origin Company of the study size. USA. Data collection and an analysis techniques K-means me th od of n on-hierarc hical cluste r a nalysis, mean ra tings carried o ut o n se condary data (from 1969 ) Calcu lation of me an scores from question naire d ata. Data from authors’ previou s stud y (1975) ana lyse d for possible exp orte r profiles, multiple cla ssific ation analysis and au tomatic interac tion detec tor analysis Chi-square test, t-test, ran king carried out on data from personal interviews. 75 interviews w ith senio r and midd le mana gers of English-b ased American compan ies ac quired by foreign compa nies , qualitativ e assessmen t. Note : Many stu dies utilise combin ation s of emp irical work, con ceptua lisa tions, framew orks etc. This table indica te s the main emp hasis of the work and is on ly a sample o f the w ork rev iew ed. Fo r m ore details, please contac t the author. 18.

(25) Chapter 2- Literature Review. 2.3 The study of internationalization Historically, discussion on internationalization can be traced to economic commentators such as Adam Smith (Sutherland, 1993) and David Ricardo (Sraffa,1951). Smith remarked on the importance of recognizing the scarcity of resources and subsequently endeavoring to implement a distribution system which involved: . . . Transporting either the rude or manufactured product from the places they abound to where they are wanted (Sutherland, 1993, p. 128). The sale of exported goods served to compensate for the cost of labor incurred in producing it in the domestic market. Had it not been sold or exchanged overseas, the labor costs would never have been recovered. Ricardo (Hollander, 1979) sought to explain the mechanisms of international trade by means of viewing it as competitive resource allocation in an international context, both in terms of barter and in the presence of a monetary medium of exchange. Haberler (1933) notes that the contributions made by Smith, Ricardo and also David Hume formed the basis of what became known as classical theory of international trade. These approaches are economic in nature whereas many of the more recent conceptualizations of the internationalization process centre on the behavioral theory of the firm (Reid, 1980; Leonidou,1989) . International marketing theory in general tends to be underdeveloped (Wind, 1979) and there are inherent dangers in relying on approaches with theoretical and methodological deficiencies (Ford and Leonidou, 1991). With the globalization of markets, and the increasing speed with which industry and product life cycles occur, various methods may be needed in order to understand contemporary behavior of the internationalizing firm: Internationalization is a continuous process of choice between policies which differ maybe only marginally from the status quo. It is perhaps best conceptualized in terms of the learning curve theory. Certain stimuli induce a firm to move to a higher export stage, the experience (or learning) that is gained then alters the firm’s perceptions, expectations and indeed managerial capacity and competence; and new stimuli then induce the firm to move to the next higher export stage, and so on (Cunningham and Homse, 1982, p. 328) This definition of internationalization concerns the exporting firm but early internationalization theory focused mainly on the international activities of the Multinational enterprise or corporation (Ayal and Zif, 1979; Beamish and Banks, 1987). Internationalization has been used to describe the outward movement in an Individual firm’s or larger grouping’s international operations (Johanson and Vahlne, 1977; Piercy, 1981). Welch and Luostarinen (1988) interpret it as the process of increasing involvement in international operations while Steinmann et al. (1980) note that existing frameworks describe the process as scaling up the strategy-ladder of internationalization. In researching medium sized firms, the author view internationalization as involving only the last phase of the progression: foreign direct investment in own production facilities (Buckley and Casson, 1976). Here the firm is viewed as consisting of an internalized package of resources which are then allocated among product groups and between national markets. This model appears to fit the behavior of the larger internationalizing firm but fails to take account of the behavior.

(26) Chapter 2- Literature Review of its smaller counterpart, where product, firm size, industry and owner/manager issues impact on internationalization behavior to greater degrees (Boter and Holmquist, 1996; Fillis,2000b). Johanson and Wiedersheim-Paul (1975) noted that although the majority of research tends to centre on the multinational firm, a large number of smaller firms are involved in international activities and continue to grow over time in stages or phases: . . . we have several observations indicating that this gradual internationalization, rather than large, spectacular foreign investments, is characteristic of the internationalization process of most Swedish firms. It seems reasonable to believe that the same holds true for many firms from other countries with small domestic markets (Johansson and Wiedersheim-Paul, 1975, p. 305). Their research centered on a longitudinal case study of four large Swedish firms involved in international operations, with over two thirds of their turnover coming from overseas markets. The authors noted that studies of international firms at that time tended to focus on those businesses already established abroad, while ignoring those firms new to international activities. They also discuss the true meaning of the international firm in that international can refer to an attitude of the firm relating to overseas activities or the actual process by which the firm carries out these activities. International experience affects the attitudes of the key decision makers involved; it is the lack of knowledge and limitation of resources which tend to prevent the firm from growing. Uncertainty about foreign markets is also linked to the incremental process of internationalization: We are not trying to explain why firms start exporting but assume that, because of lack of knowledge about foreign countries and a propensity to avoid uncertainty, the firm starts exporting to neighboring countries or countries that are comparatively well-known and similar with regard to business practices (Johansson and Iedersheim-Paul, 1975, p. 306). As experience and knowledge increases, culturally distant export markets will then be selected. Johanson and Wiedersheim-Paul accept that there are limitations to their framework: the overseas market may not be large enough to merit the large resource commitments linked to foreign direct investment and some firms may be able to jump several of the stages due to their experience gained in other markets. However the firm behaves, one of the main factors is the decision making abilities of the key personnel involved in the firm. Several alternative approaches to stages theory have been developed in order to understand and explain internationalization behaviour; for example, transaction costs analysis (Anderson and Gatignon, 1986) and the eclectic paradigm (Dunning, 1988, 1994). Anderson and Gatignon investigate the hypothesis that the choice of particular mode of entry is related to the degree of control available and the costs of the particular resources involved, which are in turn connected with varying degrees of risk and uncertainty. The authors construct a transaction cost framework to assess market entry mode efficiency incorporating dimensions including uncertainty and transaction-specific assets. Examples of transaction-specific assets include specialized physical and human investments, peculiar to a limited number of users. Other factors involved include external uncertainty which relates to the dynamic nature of the. 20.

(27) Chapter 2- Literature Review external environment, while internal uncertainty centres on measurability problems in assessing observable output performance by various agents. Free-riding potential is determined by the agents’ ability to acquire benefits without incurring associated costs. Whitelock and Munday (1993, p. 19) promote the use of the eclectic paradigm as an alternative method of understanding internationalization behaviour, given the limitations of process/ stage theory: This approach emphasizes the role of ownership advantages in the form of intellectual property rights and proprietary know-how, the ability of the multinationals to exploit location advantages to gain lowest cost production, and the benefits of using the internal market by operating through foreign subsidiaries. With regards to the smaller firm, ownership specific advantages could refer to factors such as knowledge and competency-based issues. Given that the majority of firms are small (Storey, 1994), this approach in its present form, biased towards multinational firm behaviors, is not best suited to explaining small firm internationalization behavior. Conversely, SME behaviors is mostly described using process/stage theory and, although its validity is continually being questioned, it is currently perceived to be the most dominant paradigm of internationalization: Although most empirical studies seem to have validated the process theory of internationalization, some results also contradict the generally accepted description of this process. Some reports indicate an increased tendency on the part of firms to leap-frog low-commitment modes or jump immediately to psychically distant markets (Vahlne and Nordstrom 1993, p. 530). Additional factors which impact on the process include the industry type, product type and the particular cultural characteristics of the domestic and foreign country. Rao and Naidu (1992) remark that the issue of internationalization has tended to be dealt with at the conceptual/theoretical level much more than on an empirical basis. Andersen (1993, p. 218) summarizes the merits of both the transaction cost approach and the eclectic paradigm by viewing them as being ``more relevant at the later stages of the internationalization process’’. Given that many small firms do not progress beyond a certain stage, these frameworks will be largely redundant in explaining their internationalization behavior (Fillis, 2000b). Following a critical analysis of existing internationalization frameworks Johanson and Vahlne (1990) propose an additional conceptualizations by examining the phenomenon of international industrial networks and the impact of relationship building on internationalization behavior. The authors link existing knowledge and commitment of the firm to other actors in the overseas market, through business activities carried out by all participating firms. Internationalization through networking can be achieved by establishing and building new relationships in new markets and also by connecting to existing networks in other countries. Johanson and Mattson (1988) discuss the usefulness of a network model of internationalization by examining exchange relationships between firms and analyzing existing internationalization paradigms. The network approach has been derived from Swedish research concerning industrial internationalization processes, distribution systems and behavioral interaction between firms. Coviello and McAuley (1999) view internationalization through networking as being more multilateral than the stages approach. Internationalization is driven by the formation and exploitation of. 21.

(28) Chapter 2- Literature Review the firm’s group of network relationships, rather than through the existence of particular strategic and firm level advantages.. 2.4 SMEs and export barriers Review of literature concerning the internationalization of the firm enables us to affirm that, particularly in the case of small and medium-sized firms with limited funds (Buckley and Ghauri, 1993; Durán, 1994), and in general for all companies that are taking the first steps towards international business (Young,1987), internationalization is a process of incremental involvement. This process is guided by the risks that are inherent in the lack of knowledge about foreign markets and the new tasks that such an involvement will imply (Johanson and Vahlne, 1990; Johanson and Weidersheim-Paul, 1975). Within this sequential view of the internationalization process, exporting becomes a key learning tool in that process (Cavusgil and Nevin, 1980), since it is an entry mode to foreign markets which (a) involves little or no investment – thus minimal business risks – and (b) allows a firm’s products to reach foreign markets while the company still lacks knowledge about export operation procedures (Root, 1994). Based on the aforementioned assumptions and also on the parallelism that has been established between the process of initiating export activities and that of the adoption of an innovation (Reid, 1981), a series of export development models has emerged (e.g. Chetty and Hamilton, 1996). Concerning this research stream, Cavusgil (1990) states that three main conclusions can be made: first, initial steps towards internationalization are characterized by being a gradual process, occurring in gradually increasing stages and over a relatively long period of time; second, these initial steps can be considered as an innovation within the immediate context of the firm; finally, many small and medium-sized companies start exporting without having carried out much rational analysis or deliberate planning. Also, according to Leonidou and Katsikeas’s (1996) literature review, despite differences among the various models as to the number, nature and content of the stages, the export development process can be divided into three broad phases: the preengagement phase – including those firms not interested in exporting, those seriously considering export activity, and those that used to export in the past but no longer do so – the initial phase and the advanced phase. As Glen Hornby (2002) stated in his study about “PERCEPTIONS OF EXPORT BARRIERS AND CULTURAL ISSUES” the Internet has become an integral part of most successful businesses. Few businesses today do not have a website. Small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have been increasingly enjoying the benefits of ECommerce (Bennett, 1997; Fink, 1998). Two of the most commonly cited benefits of E-Commerce revolve around being a low cost and effective marketing tool, and an ability to reach out to a global audience (West Australian Electronic Commerce Centre, 1999). Some even suggest that the Internet is “the only cost effective way in which many such firms can engage in trade across borders” (www.dfat.gov.au). General consensus of opinion is that the Internet is a low-cost option, and SMEs that have traditionally been restrained from international trade because of resource limitations (Kandasaami, 1998; Poon & Swatman, 1995) are able to present themselves and their products in as eye-catching and professional manner as those of larger corporations (Bennett, 1997). With testimonials such as these from both. 22.

(29) Chapter 2- Literature Review academic and government organizations, the Internet is almost proclaimed to SMEs as the perfect tool, providing express routes to international trade. SMEs traditionally have some typical barriers to adopt internet and e-commerce in their business some of these barriers are as follow (Chau & Pederson, 2000): • • • • • • • •. Lack of cost effective e-commerce enabled software General lack of resources Complications in implementing change Lack of technical skills and training Computer apprehension Ongoing support costs Inter-organizational motivation Giving priority to e-commerce initiatives. Theoretically, exporting SMEs should have a higher propensity for Internet uptake. Devins (1994) identified that successful SMEs had certain innovative activities, which included exports. Hence if SMEs who are more innovative are more likely to take up exporting, they are probably more likely to take up new technologies such as the Internet. Poon and Swatman (1997) identified that businesses with localized markets do not gain as much benefit from such factors as low cost communication or widened corporate exposure as businesses with wide geographic consumer base. It is logical extension then, to suggest exporters or international traders have a lot to gain from the use of the Internet. Traditionally, small businesses wishing to export face a number of internal and external obstacles (Hamill, 1998; Hamill and Gregory, 1997; Julien, Joyal, Deshaies, Ramangalahy, 1997; Leonidou, 1995a; Bennett, 1997, Bennett, 1998). Leonidou (1995b) suggested that fear of intense competition in foreign markets was the biggest barrier to export activity, with attitudes towards risk and innovation also being important. The research confirmed previous research by Dicht et al. (1990) that psychic distance from the foreign markets greatly affected firms export activities. Hamill and Gregory's (1997) work identified four main categories of barriers to export activities.. 23.

Figure

Related documents

Camilla Nothhaft (2017): Moments of lobbying: an ethnographic study of meetings between lobbyists and politicians.. Örebro Studies in Media and

Although the examples of clashes have been reported in different places and involvement of immigrant families with local social workers, this study focused on identifying

10 clusterings were performed per dataset (40 in total). 4) Reproducibility of SOM using noisy data. Hence, it is the clustering reproducibility in the presence of

With respect to some attributes that we used to distinguish a firm’s internationalization process as following the Uppsala or traditional paths (importance of the home market,

Perhaps we should simply conclude that this particular decision problem was so complex that no rational method for evaluation could assist the decision makers.. The Swedish

In a digital financial context, money and transactions are basically represented by information, wherefore records management becomes crucial, and also plays

where r i,t − r f ,t is the excess return of the each firm’s stock return over the risk-free inter- est rate, ( r m,t − r f ,t ) is the excess return of the market portfolio, SMB i,t

The public administration is thus in need for checks and balances, or in this case a separation of interest (Dahlström et.al, 2012). Meritocracy creates this separation of