J

Ö N K Ö P I N GI

N T E R N A T I O N A LB

U S I N E S SS

C H O O L JÖNKÖPING UNIVERSITYCivilekonom Thesis within BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION Author: MONIKA CEDERVINGE

870126-2449

NATHALIE MONTAL 840623-3968

Tutor: Assoc. Prof. Dr.Dr. PETRA INWINKL

Jönköping May 2012

What trends can be seen in respect to independence, gender,

tenure and age among board members between 2001- 2010?

J

Ö N K Ö P I N GI

N T E R N A T I O N A LB

U S I N E S SS

C H O O L JÖNKÖPING UNIVERSITYAcknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the people that have been a part of the journey of finalizing this Master Thesis.

We would especially like to thank our tutor Assoc. Prof. Dr. Dr Petra Inwinkl at Jönköpings International Business School who has guided us throughout the whole

pro-cess with great advice and support.

We would also like to show our appreciation to our fellow students for their provision of constructive feedback and engagement during seminars.

--- --- Monika Cedervinge Nathalie Montal

Abstract

Corporate Governance is an important topic that has been given a great deal of attention the last decade and the attention has increased even more with the financial crisis of 2007-2009. The severe financial and economic crisis has worsened the relationship be-tween shareholders and corporations, including banks, as well as bebe-tween the executive management and the board of directors. There is a need to rebuild the trust between the-se actors and Corporate Governance is considered to be a helpful tool in order to achieve this.

A mean that is used within Corporate Governance to protect shareholders in the finan-cial market is the use of independent directors as a monitoring device for the executive management. Independent directors are considered to play an important role on boards and are preventing inside directors from abusing their power in hazardous ways. The ef-ficiency of independent directors has however shown to differ between industries. The banking industry in particular stands out in comparison to non-financial firms. It is vital that independent directors are provided with the right expertise that is needed to funda-mentally understand the complex industry of banks, and there is a risk that these direc-tors lack this kind of knowledge which makes their presence inefficient.

The aim of this thesis is to investigate whether there have been any changes in the num-ber of independent board memnum-bers in four Swedish banks within the time period of 2001-2010. The banks that are included in this study are Handelsbanken, Nordea, SEB and Swedbank. Variables that are covered in the study are, except for number of inde-pendent board members in respect to the bank and major shareholders, the number of executives on the boards, the gender distribution, average age and average tenure of the independent board members.

The result shows that there has been an increase in the number of independent board members within the investigated time period. The banks are complying with guidelines concerning board independence that are included in various recommendations provided by both the European Commission as well as the Swedish Corporate Governance Board.

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments ... i Abstract ... i 1 Introduction ... 1 1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Problem ... 2 1.3 Purpose ... 21.4 Outline of the thesis ... 3

2 Frame of reference ... 4

2.1 Board of directors ... 4

2.1.1 The role of board of directors ... 4

2.1.2 Board of directors on EU-‐ level ... 5

2.1.3 Board of directors in Sweden ... 7

2.2 Independent directors ... 8

2.2.1 Agency Theory ... 8

2.2.2 Definition of an independent director ... 10

2.2.3 The role of an independent director ... 11

2.2.4 Efficiency of independent directors ... 12

2.2.5 Gender distribution ... 13

2.2.6 Age ... 14

2.2.7 Tenure ... 15

2.3 Corporate Governance in Banks ... 16

2.3.1 The Basel Committee ... 16

2.3.2 Basel III ... 17

3 Method ... 19

3.1 Research approach ... 19

3.2 The Case Study ... 19

3.3 Calculation of variables ... 21

3.4 Data Collection ... 22

3.5 Reliability and Validity ... 23

4 Empirical Findings ... 25

4.1 Handelsbanken ... 25

4.1.1 Number of independent board members ... 25

4.1.2 Number of executives on the board ... 27

4.1.3 Distribution of gender of the independent directors ... 28

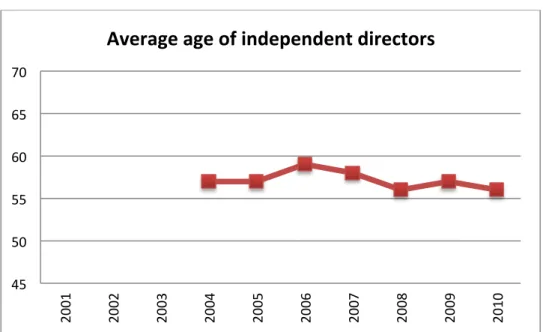

4.1.4 Average age of independent directors ... 29

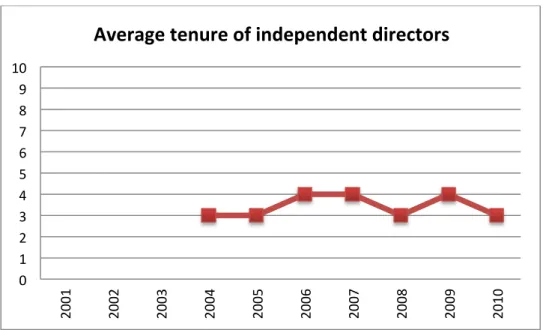

4.1.5 Average tenure of independent directors ... 30

4.2 Nordea ... 31

4.2.1 Number of independent board members ... 31

4.2.2 Number of executives on the board ... 33

4.2.3 Distribution of gender of the independent directors ... 34

4.2.4 Average age of independent directors ... 35

4.2.5 Average tenure of independent directors ... 36

4.3 SEB ... 37

4.3.1 Number of independent board members ... 37

4.3.2 Number of executives on the board ... 39

4.3.3 Distribution of gender of the independent directors ... 40

4.3.5 Average tenure of independent directors ... 42

4.4 Swedbank ... 43

4.4.1 Number of independent board members ... 43

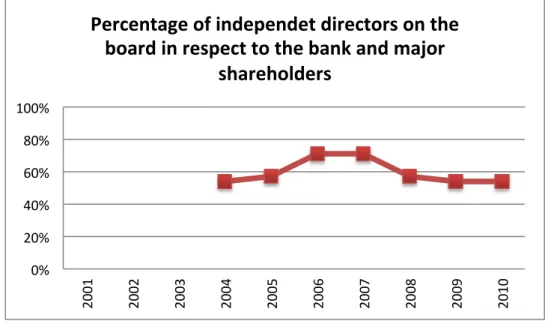

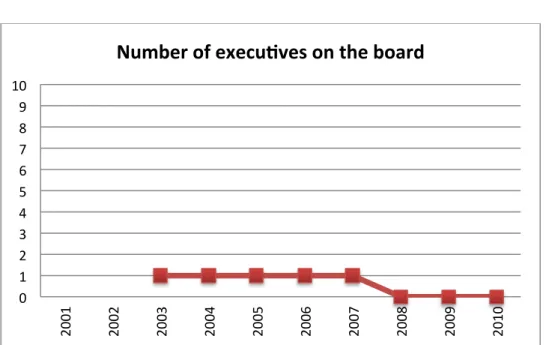

4.4.2 Number of executives on the board ... 45

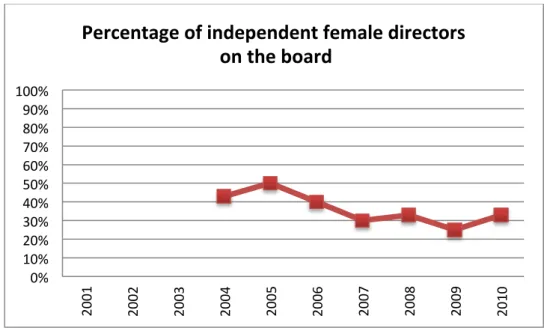

4.4.3 Distribution of gender of the independent directors ... 46

4.4.4 Average age of independent directors ... 47

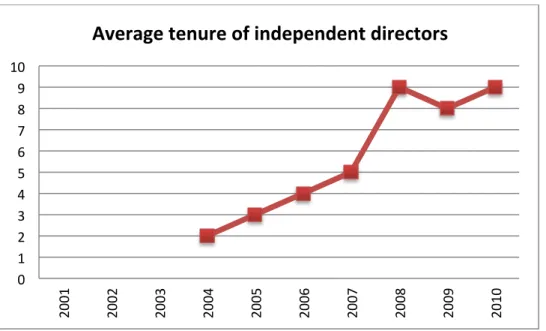

4.4.5 Average tenure of independent directors ... 48

4.5 Summary of Empirical Findings ... 49

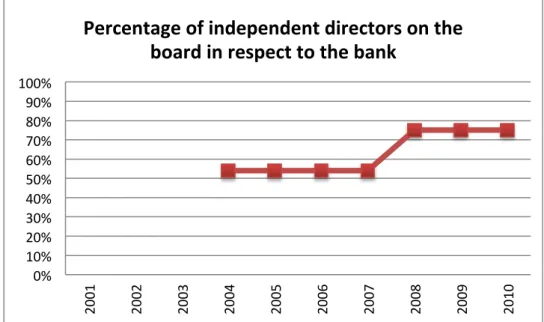

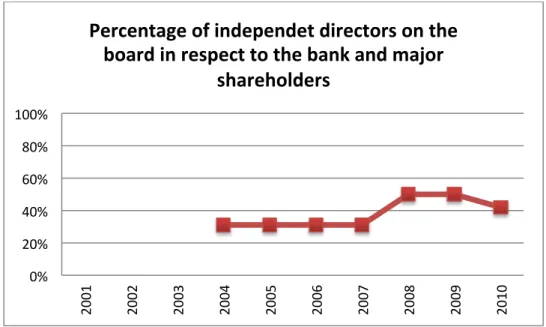

4.5.1 Number of independent board members ... 49

4.5.2 Number of executives on the boards ... 51

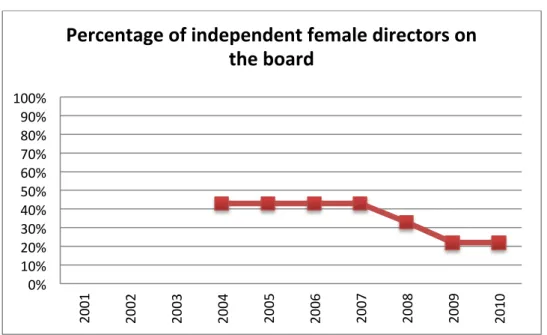

4.5.3 Distribution of gender of the independent directors ... 52

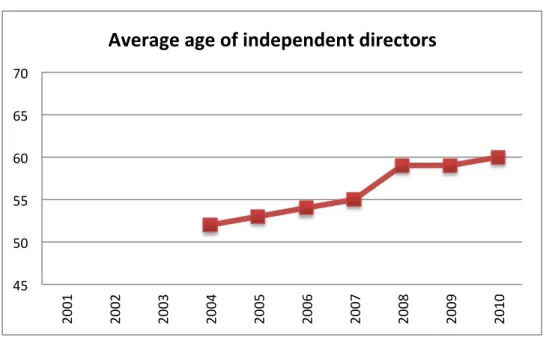

4.5.4 Average age of independent directors ... 53

4.5.5 Average tenure of the independent directors ... 54

5 Analysis ... 56

5.1 Number of independent board members ... 56

5.2 Number of executives on the boards ... 59

5.3 Distribution of gender of the independent directors on the boards ... 61

5.4 Average age of independent directors ... 62

5.5 Average tenure of independent directors ... 63

6 Conclusion ... 66

References ... 68

Tables Table 1 Handelsbanken-‐ Number and percentage of independent board members………. 26

Table 2 Handelsbanken-‐ Percentage of independent directors on the board in respect to the bank………..………...26

Table 3 Handelsbanken-‐ Percentage of independent directors on the board in respect to the bank and major shareholders……….……….…27

Table 4 Handelsbanken-‐ Number of executives on the board 1……….28

Table 5 Handelsbanken-‐ Number of executives on the board 2……….28

Table 6 Handelsbanken-‐ Number and percentage of independent female directors on the board…………..………29

Table 7 Handelsbanken-‐ Percentage of independent female directors on the board……… 29

Table 8 Handelsbanken-‐ Average age of independent directors 1………30

Table 9 Handelsbanken-‐ Average age of independent directors 2………30

Table 10 Handelsbanken-‐ Average tenure of independent directors 1………31

Table 11 Handelsbanken-‐ Average tenure of independent directors 2………31

Table 12 Nordea-‐ Number and percentage of independent board members……….32

Table 13 Nordea-‐ Percentage of independent directors on the board in respect to the bank……….……….33

Table 14 Nordea-‐ Percentage of independent directors on the board in respect to the bank and major shareholders………..……….………33

Table 15 Nordea-‐Number of executives on the board 1……….………..34

Table 16 Nordea-‐ Number of executives on the board 2………..34

Table 17 Nordea-‐Numer and percentage of female independent directors on the board………35

Table 18 Nordea-‐ Percentage of independent female directors on the board………..35

Table 19 Nordea-‐Average age of independent directors 1………..36

Table 21 Nordea-‐Average tenure of independent directors 1………..37

Table 22 Nordea-‐ Average tenure of independent directors 2……….37

Table 23 SEB-‐ Number and percentage of independent board members……….38

Table 24 SEB-‐ Percentage of independent directors on the board in respect to the bank ……..39

Table 25 SEB-‐ Percentage of independent directors on the board in respect to the bank and major shareholders………..………39

Table 26 SEB-‐ Number of executives on the board 1……….……..40

Table 27 SEB-‐ Number of executives on the board 2………40

Table 28 SEB-‐ Number and percentage of female independent directors on the board………….41

Table 29 SEB-‐ Percentage of independent female directors on the board………41

Table 30 SEB-‐ Average age of independent directors 1………..……42

Table 31 SEB-‐ Average age of independent directors 2………..……42

Table 32 SEB-‐ Average tenure of independent directors 1………..43

Table 33 SEB-‐ Average tenure of independent directors 2………..43

Table 34 Swedbank-‐ Number and percentage of independent board members……….44

Table 35 Swedbank-‐ Percentage of independent directors on the board in respect to the bank………..……….45

Table 36 Swedbank-‐ Percentage of independent directors on the board in respect to the bank and major shareholders………..………45

Table 37 Swedbank-‐ Number of executives on the board 1………46

Table 38 Swedbank-‐ Number of executives on the board 2………46

Table 39 Swedbank-‐Number and percentage of independent female directors on the board……….47

Table 40 Swedbank-‐ Percentage of independent female directors on the board………..47

Table 41 Swedbank-‐Average age of independent directors 1………..48

Table 42 Swedbank-‐ Average age of independent directors 2……….48

Table 43 Swedbank-‐Average tenure of independent directors 1………49

Table 44 Swedbank-‐ Average tenure of independent directors 2………..49

Table 45 Summary-‐ Average number and percentage of independent board members………..50

Table 46 Summary-‐ Average percentage of independent directors on the boards in respect to the banks……….……….50

Table 47 Summary-‐ Average percentage of independent directors on the boards in respect to the banks and major shareholders………..51

Table 48 Summary-‐Average number of executives on the boards 1……….52

Table 49 Summary-‐ Average number of executives on the boards 2………52

Table 50 Summary-‐Average number and percentage of independent female directors on the boards………..53

Table 51 Summary-‐ Average percentage of independent female directors on the boards………53

Table 52 Summary-‐Average age of independent directors 1………..54

Table 53 Summary-‐ Average age of independent directors 2……….54

Table 54 Summary-‐Average tenure of independent directors 1………..54

1 Introduction

1.1 Background

Corporate Governance is an ongoing evolving subject which has created an extensive awareness the last decade, especially during the financial crisis in 2007-2009 (Bonaci & Mustata, 2011). The recent financial and economic crisis led to a number of significant collapses which hit financial institutions throughout the world, caused turbulence in the economy and engendered a loss of confidence in the market. As a result, several banks faced severe difficulties to survive and some influential ones were forced to file for bankruptcy (OECD, 2009). This world-wide financial crisis has had substantial negative impacts on the society, which are present still today, where millions of people have lost their jobs (IMF/ILO, 2010). There is presently a need to restore investors’ confidence in the market in order to secure the growth of the economic future. One way of achieving this ambition is to increase the accountability and transparency of entities’ operations and activities in order to protect and maintain the rights of shareholders (ICGN, 2009). Corporate Governance is a tool that is used to enhance the trust between various actors in a market. The primary reason for the use and implementation of Corporate Govern-ance is for shareholders to be able to protect their interests and exercise control over the corporation’s management. Hence, Corporate Governance can be seen as a stakehold-er’s control tool (Kose & Lemma, 1998).

A central part of Corporate Governance in corporations, including banks, is the board of directors (Kose et al, 1998). The board of directors serves to resolve potential conflicts of interest that may arise among decision-makers in a corporation. They also strive to reduce potential costs that the separation of ownership by the shareholders and control by the management in the market causes (Baysinger & Butler, 1985). Further on, the in-dependency of the directors who serve on the boards is a factor that has been considered to have a large impact on corporation performance. An independent director is playing a key role on a corporate board and brings many important benefits to a corporation. They are independent from the management and therefore considered to have good possibili-ties to perform solid monitoring of the operations of the company without being threat-ened by any conflict of interest. They are also seen as providers of new knowledge and

contribute with outside perspectives which may benefit the company (Duchin, Matsusa-ka & Ozbas, 2009).

1.2 Problem

The scrutiny of corporate boards by the public has highly increased in the recent years and the main focus for regulators and Corporate Governance reformers has been to in-crease the number of independent directors represented on boards in order to compose well-functioning boards with an efficient division of power. It is argued that independ-ent directors are important to include on boards since they will enhance the protection of shareholders and decrease conflict of interests (Duchin et al, 2009).

However, a number of other evidence has also been revealed from research within this area, showing opposite results and several studies made to analyze the effect of having large parts of boards represented by independent directors have shown many potential disadvantages. Independent directors face limitations due to inferior expertise about the corporation they work for compared to inside directors which may in many cases harm their performance. It is argued that regulation within this area might be risky and harm-ful for corporations where a large representation of independent directors is not appro-priate and directly inefficient (Duchin et al, 2009). Due to the mixed evidence concern-ing the efficiency of independent directors, this study investigates how the representa-tion of independent board members has changed in Swedish banks the last ten years. The choice of topic for our thesis concerns the number of independent board members in four Swedish banks between the period of 2001- 2010.

We have found that much research has been conducted concerning independent direc-tors’ representation on corporate boards covering both US and European level. Howev-er, we have not found any research that sufficiently has covered how the representation of independent directors on boards in Swedish banks has changed in the last decade.

1.3 Purpose

The purpose of this thesis is to conduct a case study in order to investigate whether the number of independent board members in four banks in Sweden has changed between 2001 and 2010 and analyze possible reasons behind any potential changes. The study will also include a number of additional variables that concern the independent directors namely: age, number of executives, gender and tenure.

Research shows both positive and negative effects of including independent directors on boards and our aim is to link our findings to different theories concerning the topic. The main goal of our thesis is to answer the question:

What trends have been seen in the proportion of independent directors represented on corporate boards in four Swedish banks between 2001 and 2010 in respect to number, age, gender and tenure?

1.4 Outline of the thesis

Chapter 2 presents the prior research and the frame of reference for this study. It pro-vides a description of the definition, role and purpose of the board of directors and in-dependent directors as well as relevant regulation within this area.

Chapter 3 contains the method for this research and describes what approaches that are used as well as what data that is collected, processed and analyzed.

Chapter 4 shows the empirical findings and a summary of the material that is gathered for each of the banks. The time frame used in the case study is 2001-2010.

Chapter 5 provides an analysis of the obtained results from the empirical findings. The analysis is based on the received results along with the earlier reviewed literature. Chapter 6 expresses concluding statements.

2 Frame of reference

2.1 Board of directors

2.1.1 The role of board of directors

The board of directors in a bank has many vital responsibilities and is viewed as a pri-mary mean for shareholders to feel safe in the market (Kose et al 1998). One of the board’s most important duties is to monitor and evaluate the work of the executive management. A corporate board oversees the performance of the bank and comment on important decisions that are made in the organization (Steven, 2005). The tasks of a corporate board are generally the same for financial and nonfinancial firms (Adams, 2009).

In order for the board to perform efficient monitoring, it is vital that the directors on the board have a solid understanding of the bank’s long-term strategies, risks, goals and business. The board shall also represent an independent view, which is not influenced by the top management of the bank and always have the interest of the companies’ stakeholders as their core focus when performing their responsibilities. A corporate board of directors works in order to assure that the bank takes wise decisions that do not jeopardize the company’s long-term success and to prevent management from taking excessive risks (Steven, 2005).

A proper balance and mix of qualifications should be maintained among the directors on a corporate board. The board should determine which qualities that are needed to achieve the necessary knowledge, experience and judgment that is required in order for the board to perform their tasks in an appropriate way. The qualities needed can differ between firms and depend on the size, business and overall activities of the firm (EC, 2005). The particular industry of banks is very complex and consists of several multi-faceted institutions. This requires directors to have a deep knowledge in finance to fun-damentally understand the operations of a bank and contribute to its performance (Ad-ams, 2009). As an appointment of a director is proposed, a disclosure of the appointed director’s competence should, according to recommendations provided by the European Commission, be presented so that the public can make an assessment of whether the qualifications are appropriate for the service and tasks that the director is appointed to. Further on, a new director should be offered a tailored introduction program covering

the ongoing activities of the company and the responsibilities that will be dedicated to the director. The board is also in charge of annually reviewing the directors to identify if there are any areas where the directors’ skills and knowledge need to be updated (EC, 2005).

2.1.2 Board of directors on EU- level

The board of directors is an issue that has been raised at EU level and a number of rec-ommendations regarding this subject have been released. In 2003, the European Com-mission presented a proposal for an action plan, “Modernizing Company Law and En-hancing Corporate Governance in the European Union - A Plan to Move Forward”. The main goal with this plan was to strengthen shareholders’ rights and to increase the pro-tection of other stakeholders. The plan was accepted and a recommendation was intro-duced in 2005 (EC, 2005). The recommendation mainly proposes to enhance the use of Corporate Governance in the European Union and to improve the Company Law in the member states. It consists of a number of specific objectives for corporations to focus on and one of these objectives is the modernization of boards of directors. Top priority is to prevent any conflict of interests to occur on boards and to streamline the composi-tion of the boards. The recommendacomposi-tion developed by the European Commission con-tains 6 core objectives regarding the composition of corporate boards, namely:

- An appropriate balance of executive and non-executive directors on boards, in-cluding a separation of the functions of chairman of the board and chief execu-tive officer, (CEO)

- A sufficient number of independent directors on boards, as well as adequate disclosure on the determination of board members’ independence

- The creation of board committees, which should mainly comprise independent non-executive directors

- The regular evaluation of the board’s functioning and competence

- An enhanced transparency and communication from companies towards share-holders on board’s activities

- A clarification of standards of qualification, competence, and availability for board members (Commission of the European Communities, 2007).

The member states of the European Union were in 2006 invited to put this recommen-dation into practice either through legislation or best practice rules. The European

Commission does not find it necessary for the member states to apply detailed binding rules in order to achieve the purpose of the recommendation and many member states have chosen to implement the recommendation in their Corporate Governance Codes that are based on a “comply or explain” basis. In this case, companies in the member states disclose whether or not they comply with the recommendation and explain any deviations from it (EC, 2005).

Except for the recommendation that has been implemented by the European Commis-sion, the Commission has in respect to Corporate Governance the recent years issued a number of consultation papers. “The Green Paper – The EU Corporate Governance Framework” issued in 2011 is one of them. One of the main subjects that this Green Pa-per addresses is the board of directors. The paPa-per highlights that fact that it is important to have efficient boards to challenge the executive management. Further on, such boards should include non-executive directors that possess diverse skills, values and visions. According to the Green Paper the greater the diversity among the board, the more moni-toring is generated because of increased discussion and more ideas that are raised due to the variety of people (EC, 2011a).

In the feedback statement for “the Green Paper on the EU Corporate Governance Framework” one question is especially raised when it comes to independent directors. The question is if there should be a legal measure on EU level that is limiting the num-ber of mandates that independent directors can hold. The result of the feedback shows that less than 25% of the respondents were in favor of such a proposal. They instead provided suggestions that a recommendation would be sufficient enough or that such legislation, if so, only shall apply to listed or complex companies.

Most of the respondents that replied to the feedback statement recommended a limit be-tween three and five, although there were many respondents that thought that it was dif-ficult to set an appropriate number to find the right balance. Others pointed out that such a measure would not be effective to determine since different companies might need different amount of independent directors on the board in order to function in an opti-mal way (EC, 2011c).

By using the feedback on the consultation paper as a basis, the Commission will decide whether they will form any legislative proposals concerning the issues raised in the Green Paper or not (EC, 2011b).

2.1.3 Board of directors in Sweden

In Sweden, rules and recommendations concerning board of directors and independent directors can be found in the Swedish Companies Act and in the Swedish Corporate Governance Code. The Code includes recommendations concerning the board of direc-tors such as information about the main tasks of the board and their responsibilities. It also brings up criteria for an appropriate composition of the board and specifies the re-quirements of having independent directors present (Swedish Corporate Governance Board, 2010).

The body that is responsible for the development and maintenance of the Code in Swe-den is the Swedish Corporate Governance Board. Their main task is to manage and make necessary improvements to the Code in order to promote good Corporate Govern-ance among listed companies in Sweden (Kollegiet för Svensk Bolagsstyrning, 2010). The first Corporate Governance Code in Sweden was presented in 2004 and introduced in July 1st in 2005. All Swedish listed companies on the A and O-list with a market val-ue that exceeded three million kronor were obliged to comply with the Code. In 2007, the first revision of the Swedish Code was made and now required all listed companies to comply with the Code (Kollegiet för Svensk Bolagsstyrning, 2010).

The Code was further revised again on July 1st 2008. The revised Code was implement-ed and now comprisimplement-ed all Swimplement-edish companies tradimplement-ed in the NASDAQ OMX Stockholm and NGM Equity. A third revision was made in 2010 mainly because of material chang-es that were made to Swedish legislation. One of the major changchang-es that led to the re-cent revision of the Code was the fact that NASDAQ OMX Stockholm decided to abro-gate regulation concerning independent directors and now the revised Code instead put emphasis on this matter (Kollegiet för Svensk Bolagsstyrning, 2010).

The Swedish Code is not a part of the listing rules in Sweden or any other regulation. However, it does express commonly accepted market practice. Hence, the Swedish Code can be seen as being indirectly a part of Swedish regulation since corporations

have to follow commonly accepted market principles in order to fully comply with ap-plicable listing rules (Kollegiet för Svensk Bolagsstyrning, 2010).

According to the Swedish Code, a board shall be composed in a way that ensures that the management of a bank’s affairs can be conducted in an effective and appropriate way. The Code requires the board to consist of at least three board members in a total. Only one member of the board is, according to the Code, allowed to work as an execu-tive director for the company or any subsidiary company. It is quite common that the board has no executives at all represented on the board, but if they do, the CEO of the company usually takes this position. Hence, the board mainly consists of non-executive directors. Further on, the Code states that the majority of a board shall consist of non-executive directors, who are independent from the company and the management. An-other requirement implies that two of the board’s independent directors also have to be independent, not only from the bank itself and its management, but also from the bank’s largest shareholders. If a shareholder directly or indirectly controls more than 10% of the shares or votes in a company, this shareholder is considered as a large shareholder (Kollegiet för Svensk Bolagsstyrning, 2010).

2.2 Independent directors

2.2.1 Agency Theory

The importance of independent directors on corporate boards is linked to the agency theory. The history of the agency theory goes back to the 1960s and 1970s when a group of economists investigated risk sharing among individuals and the different groups that are formed when cooperating parties do not share the same attitude towards risk. The agency problem originates from this area and besides risk attitude that differs between cooperating parties, the theory also includes the problems that arise when co-operating parties do not share the same goals (Eisenhardt, 1989).

The agency relationship in the agency theory relates to a principal and an agent. The principal is a party who delegates work to the agent, and the agent is the party that per-forms the work (Eisenhardt 1989). Principal and agent relationships can occur in many different shapes but the most common is the one where the management is thought of as the agents and the shareholders are the principals (Kosnik 1987). Kosnik (1987) argues that disagreements between managers and shareholders may occur when managers do

not bear the full wealth effect of the decisions they make when they do not own a part of the equity in the corporation. This kind of situation increases the risk that a manager will act in a way that increases his or her own personal wealth, but which might be un-desirable by shareholders.

As the globalization of the economy has diversified the ownership structure, a share-holder today has a more limited insight into the corporation in which he or she invests. This has created a so called “gap” between shareholders and managers, where most of the power in a corporation today lies in the hands of the management. A consequence that may arise from this is a phenomenon referred to as agency-problems (Mallin, 2010). There may be a conflict of interest between managers and shareholders as their goals and attitudes toward risk in many cases differ and the actions taken by manage-ment can therefore, in many cases, be unwanted by shareholders which create this prob-lematic gap (Ooi, 2000).

According to the agency theory, the best way to resolve such a dilemma is by the use of a contract. In order to prevent the various problems that may occur, the focus shall be to find the most efficient contract that will align the two parties and their goals (Eisen-hardt, 1989). Researchers within the area of the agency theory are trying to identify the ideal structure that will ensure an effective control function of management’s behavior to reduce agency costs and to decrease the negative effects that management’s decisions can cause shareholders (Kosnik, 1987).

One monitoring device that has found to be efficient is the board of directors in a corpo-ration. The board of directors works as a representative for the shareholders and helps to prevent agency problems from occurring by monitoring the decisions taken in the firm and making sure that the business is appropriately managed. Hence, the board of direc-tors is an important tool that is used to reduce agency problems in corporations (Kosnik 1987). Further on, having independent directors represented on the boards will provide additional protection to shareholders since they are working independently from the management (Platt et al, 2011).

2.2.2 Definition of an independent director

The definition of an independent director is rather unclear. According to “the EU rec-ommendation of 2005 on the role and definition of non-executive or supervisory direc-tors of listed companies and on the committees of the (supervisory) board”, there is a lack of a common understanding of what the word independent director in fact compris-es. The European Commission has however provided a number of guidelines in their recommendation concerning the description of an independent director. According to this recommendation, a director is independent if he or she is free from any material conflict of interest that could weaken his or her judgment. This indicates that there should be no close ties between the director and the controlling shareholders, manage-ment or the company. An independent director should further on be free from family, business or other relationship with the company.

The recommendation of 2005 states that threats to a director’s independence can differ with circumstances, from member state to member state and from company to company. Despite this, the European Commission has developed a list of criteria that should be taken into consideration when determining the independence of a director. The nine cri-teria that should be considered are the following;

An independent director cannot:

- be or have been employed by the company within the recent three years

- be or within the recent five years have been an executive or managing director of the company or an associated company

- receive any remuneration from the company except from the remuneration re-ceived as a consequence of the role as an independent director

- represent any controlling shareholder

- have had any important business relationship with the company or any associat-ed company the recent year

- within the last three years have been an employee or partner to the external audi-tor of the company or any associated company

- have been on the supervisory board as an independent director more than three terms or maximum 12 years

- be an executive or managing director in another company where an executive or a managing director is an independent director of the company

- be a close family member of any managing or executive director of the firm or any of the persons mentioned in the points above (EC, 2005).

The Swedish Corporate Governance Board has followed on these criteria and included them in the Swedish Code. If a member of the board does not attain these conditions, he or she should not, according to the Code, be considered as independent in relation to the company and its management (Kollegiet för svensk bolagsstyrning, 2010)

2.2.3 The role of an independent director

A description of an independent director’s role on a board is included in “the recom-mendation on the role of non-executive or supervisory directors of listed companies and on the committees of the (supervisory) board” issued by the European Commission. A great amount of focus in this recommendation is put on the importance of independent directors as being in charge of overseeing the executives and managing directors in the company.

A director who meets the criteria to be classified as independent, is considered to play a key role on a corporate board and brings many important benefits to the corporation. According to previous studies, independent directors are believed to contribute with vi-tal outside expertise to entities and hence, work as good advisors to improve a corpora-tion’s performance. They are also generally justified as being in a good position to ef-fectively monitor inside directors’ work in the company since they are being independ-ent from the managemindepend-ent (Duchin et al, 2009). Independindepend-ent directors help to align the goals of shareholders and managers and prevent inside directors from abusing the power they have by taking excessive risks in the firm (Mallin, 2010). It has for a long time been recognized that an independent director is an important representative for share-holders in the capital market (Platt et al, 2011).

In Sweden, the Board Academy has published a guidance document for good board practice. In this document the Board Academy highlights the importance for independ-ent directors to maintain their independency. The role of the director is to protect the in-terests of all shareholders and it is, according to the guidelines, not appropriate for an independent director to have any close relationship to any person in the company’s management. A board should always be composed in order to minimize any conflict of interest (StyrelseAkademin, 2003).

2.2.4 Efficiency of independent directors

Despite the known advantages associated with independent directors, research has shown that the efficiency of having independent directors represented on a board differs between companies. An important factor that determines the effectiveness of having in-dependent directors represented on a board is the cost of acquiring information about a corporation. When the cost of acquiring information is low, the performance increases as a corporation adds independent directors to its boards. However, when the cost of ac-quiring information is high, performance instead decreases when having a large part of the corporate board represented by independent directors (Duchin et al, 2009). Another factor that creates a potential risk with having too many independent directors repre-sented on boards is the fact that many independent board members, especially during times of financial and economic crises, put pressure on corporations to raise new equity capital. Independent directors fear that their reputation in the market for directorship will decrease if the performance of the corporation worsens or if the corporation goes bankrupt and therefore, push the company to increase their loans. The consequence of this action is a wealth transfer from shareholders to debt holders (Erkens, 2010). An ex-ample of this can be found in a study conducted by Erkens (2010) showing that during the financial crisis in 2007- 2009, firms with a higher percentage of independent board members raised more equity capital.

When it comes to banks, research has shown that there are more potential disadvantages of having independent directors on boards in financial corporations compared to non-financial corporations. Banks are complex institutions which require directors to have extensive expertise within the financial field (Adams, 2009). According to Adams (2009), independent directors on boards of banks are rarely members of other boards of financial institutions because of potential conflicts of interest that might arise. The con-sequence of this is that independent directors of boards in banks tend to lack the finan-cial expertise and the in-depth knowledge that is needed to understand the complexity of the banking industry and to effectively monitor the management’s work. These findings show that a large representation of independent directors on boards in banks in many cases may be inefficient due to the lack of experience of the directors (Adams, 2009). A study performed by Adams (2009) demonstrates the potential disadvantages with having independent directors on the boards in banks. His study shows that banks that

received bail out money in connection to the financial crisis in 2007-2009 in the United States had boards with more independent directors compared to banks which performed better and did not need financial help from the government (Adams, 2009). Other re-search that further supports this is another study conducted by Erkens (2010), which found that financial institutions with more independent boards performed worse dur-ing the crisis 2007-2009 than institutions with less independent directors represented. The results of Erken’s study indicate that independent directors on corporate boards might not always be beneficial for all corporations, especially not for the ones in the fi-nancial industry (Erkens, 2010).

2.2.5 Gender distribution

The gender of a board director is another aspect that is taken into consideration when it comes to the composition of boards. Many recent Corporate Governance Codes are pay-ing attention to the topic of gender distribution (Tyson, 2003). Accordpay-ing to the Swe-dish Corporate Governance Code (2010) a corporation should strive for an equal gender distribution among the members on the board of directors.

It is a known fact that men are overrepresented on corporate boards (Sealy & Vinni-combe, 2012). According to the European Commission, the percentage of women on board of directors in listed companies within the European Union is on an average of 12% (EC, 2011a). A study conducted by Brammer, Millington & Pavelin (2007) which included the largest banks in the UK, shows that only 10,9% of the board members in the UK banking sector consisted of women. The same study also shows that there is a reputational effect linked with having women represented on the boards. The presence of women on boards can, according to the results from this study, both harm and benefit the reputation of the firm.

One cost that might occur when adding women to a board is that the decision-making process in some cases might become slower since heterogeneity can increase conflicts (Blau, 1977). Another cost of increasing the gender diversity on the boards is the cost of teaching directors to trust each other (Tyson, 2003).

However, there are also many benefits linked with having women on the boards. It is argued that women can add different viewpoints, opinions and experiences to a group. Women are also seen as having higher anticipations concerning their responsibilities

(Fondas & Sassalos, 2000). A number of studies have shown that female board mem-bers attend more board meetings than male board memmem-bers, which indicates on a greater commitment (EC, 2011a).

A study conducted by Ellis and Keys (2003) finds a positive effect on stock prices when corporations announce actions that are diversity-promoting. Studies that are being high-lighted in the Green Paper- the EU Corporate Governance Framework, issued by the European Commission (2011), suggest that there is a positive correlation between cor-porate performance and a high proportion of women on boards.

Another study that concerns the development and recruitment of independent directors by Tyson (2003) highlights the fact that when it comes to independent directors, gender is a variable that has to be considered. Diversity of background and skills among inde-pendent directors is increasing the mix of important experiences. It might also increase the independence of the directors since diversity can elicit a challenging attitude. Final-ly, diversity of independent directors on boards can be beneficial for a company’s repu-tation. A great diversity on the board can increase the perception of the company as be-ing a responsible corporate citizen in the eyes of a stakeholder (Tyson, 2003).

2.2.6 Age

Age is also a factor that is considered when composing a board. As a director gathers experience throughout his career and working life, with age comes more expertise and knowledge. This implies that older board members should have a more positive effect on companies’ performance in comparison to younger members (Platt & Platt, 2011). In a study conducted by Platt et al (2011) it is on the other hand argued that older directors in respect to age tend to act more conservative compared to younger directors and are less willing to explore and try new ideas which might inhibit the development of a com-pany. However, regardless of the pros and cons concerning directors’ age, the study shows that companies with a higher average of older directors perform better than com-panies with a younger average of board directors. (Platt et al, 2011).

According to a study made by Nestor (2009) that is bank specific, the best practice codes in the majority of the countries included in the study suggest that there should be no age limit for the board members. However, the study points out that investors request good reasons from a bank that chooses to have directors that are over the age of 70.

2.2.7 Tenure

Tenure is yet another variable argued to affect the quality of a board director. The views regarding the effect directors’ tenure have on their behavior are however conflicting. The advantages of long board tenure are linked to the expertise hypothesis, which ar-gues that a director who is engaged in a corporation for a longer time will receive great-er expgreat-erience and commitment. The longgreat-er a director stays at a company or a bank, the more knowledge the director gains about the organization and the business environ-ment. A director will, by staying longer in the corporation, develop his or her compe-tence and confidence and hence, be better placed to perform a good job (Vafeas, 2003). Forcing directors to retire will only, according to Vance (1983), result in a loss of both experience and talent. Extended tenure will increase the organizational commitment and enhance the effort to reach companies’ goals (Salancik, 1977).

On the other hand, other researchers argue the opposite (Vafeas, 2003). Katz (1982) does not find board tenure as being positively related with the performance of a compa-ny. He argues that the performance of a company increases because of early learning ef-fects of directors which decline with time.

There has been a raised voice in the business community concerning board tenure and that directors stay on the board for too long. In order to enhance the critical thinking of board directors and to encourage innovativeness, the European Commission has provid-ed suggestions for maximum tenure limits on boards (Vafeas, 2003). According to the recommendations provided by the European Commission (2005), an independent direc-tor may serve at the board for a maximum length of 12 years in order to stay independ-ent (Vafeas, 2003).

There is further on, according to Lipton and Lorsch (1992), a risk that directors who stay at boards for a long period of time will try to usurp the role of the CEO in the com-pany. Therefore a time limit of board tenure is needed. It is also argued that the tenure of a director will affect his or her behavior toward the company. Long board tenure in-creases the risk that the directors will become too friendly, which in turn will lead to the fact that these directors will not fulfill the monitoring role to the same extend as the di-rectors who have not been sitting on the board for the same amount of time will. Limit-ing board tenure will further on, increase the amount of fresh ideas that new directors would bring to a corporation (Vafeas, 2003).

In a bank specific study, conducted by Nestor Advisors Ltd in 2009, a conclusion was drawn that independent directors tenure should not be less than four years or more than nine years. The ultimate tenure according to this study should lie between four and nine years. This result is based on the performance of 25 banks during the financial crises be-tween 2007 and 2009 correlated with the average tenure rates for the independent direc-tors. The conclusion is however, according to Nestor Advisors Ltd, made with caution and is telling boards in banks to aim at a number of an average tenure rate between four and nine years in lack of evidence that are more convincing to make a stronger conclu-sion.

However, as for Sweden, there is no tenure limit specified in the last revised Swedish Code that was implemented in 2010. Sweden has hence not included the European Commission’s recommendation in their current Code nor any other specific guidelines concerning board tenure (Wigart, 2010).

2.3 Corporate Governance in Banks

2.3.1 The Basel Committee

Besides the recommendations provided by the European Commission and legislation on national level, which holds for all types of companies, the banking sector also has a sep-arate set of recommendations concerning Corporate Governance, which is issued by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Ten countries established the committee in 1974 and the member states are represented by their central banks where Sweden is one of the members. The main goal for The Basel Committee is to improve the quality of banking supervision worldwide and to increase the understanding of supervisory issues in the banking industry. The Basel Committee develops and provides guidelines and su-pervisory standards that they recommend the member states to follow (Bank for Interna-tional Settlements, 2012).

The Basel Committee encourages a convergence between the member states towards commonly used standards; however, the recommendations they publish do not have any legal force on the member states. The Committee simply issues guidelines and recom-mendations and let the member states themselves implement the standards in the way that is best suited for them. The work of the Committee is robust and solid, and they have issued a large amount of documents with appropriate standards that can be used by

each member state to make sure that there will be no gaps in the coverage of banking supervision between the member states (Bank for International Settlements, 2012). The recent years, the Basel Committee has increased their effort to promote supervisory standards worldwide. In 1997, The Committee developed a set of “Core principles for effective Banking Supervision” together with jurisdictions that are not members of The Committee. Two years later they also implemented the “Core Principles Methodology” to simplify the implementation of the principles (Bank for International Settlements, 2012).

2.3.2 Basel III

In 2006 the Basel Committee issued eight Corporate Governance principles and in 2010 they introduced Basel III, which is a document of global standards on banking supervi-sion in response to the financial crisis of 2008. Basel III is developed to strengthen the regulation, supervision and risk management in the banking sector. It aims, among other things, to increase banks transparency and disclosure and to improve the ability of banks to maintain stability and to deal with pressure during times of financial downturns (Bank for International Settlements, 2012).

The guidelines found in Basel III help banks to enhance their Corporate Governance Framework. The document stresses the importance of effective Corporate Governance practices in order to achieve and enhance the public confidence in the banking industry. The trust of the public is argued to be a fundamental corner stone to create a proper functioning of not only the banking sector, but the economy as a whole (Basel Commit-tee on Banking Supervision, 2010)

Basel III consists of a set of principles to enhance Corporate Governance where the se-cond principle concerns the topic of the board of directors and its qualifications. The principle provides the following recommendations concerning the board:

“Board members should be and remain qualified, including through training, for their positions. They should have a clear understanding of their role in corporate governance and be able to exercise sound and objective judgment about the affairs of the bank. Board perspective and ability to exercise objective judgment independent of both the views of executives and of inappropriate political or personal interests can be enhanced by recruiting members from a sufficiently broad population of candidates, to the extent

possible and practicable given the bank’s size, complexity and geographic scope.” (Principle 2, Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, 2010)

Further on, Principle two states that banks can increase the independence of the board by adding a sufficiently large number of non-executive directors to the board. These di-rectors should, according to the principle, have adequate qualities to be able to exercise sound control and objective judgments. It is, according to Basel III, highly important to assure the independency and objectivity of the candidates when electing members to the board (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, 2010).

3 Method

3.1 Research approach

The research conducted in this study aims to answer what trends that have been seen in the proportion of independent directors represented on corporate boards in Swedish banks between 2001 and 2010 in respect to number, age, gender and tenure. The num-ber of executives directors represented on these boards is also studied.

We do not use any particular theory as a starting point in this thesis but previous litera-ture, research and scientific theories within the area of Corporate Governance and board of directors is reviewed before the execution of the investigation. This is used as a foundation for our analysis and evaluation of the collected data, which indicates towards a deductive approach of our study. Deductive research is a logical process where the re-searcher uses existing literature to try to identify theories that will be used as a founda-tion when the researcher will evaluate data that has been collected (Saunders, Lewis & Thornill, 2009). When one chooses to use the deductive approach to perform a study, the conclusions that are drawn, come from research that is already known to be true (Zikmund, 2000).

3.2 The Case Study

For the study of our thesis, four banks are chosen that we collect data from in order to analyze and discuss changes in the proportion of independent directors on the boards in these banks. The case study has a descriptive approach, which is used when the re-searcher wants to discover and describe trends in a certain situation (Olsson & Sören-sen, 2011).

The main variable that we study and analyze in our research is the number of independ-ent directors. Further on, there are other variables included that are linked to the inde-pendent directors, namely the number of executives on the board, gender, age and ten-ure of the independent directors. The tables included in the empirical findings are the following:

- The percentage of independent board directors in respect to the bank

- The percentage of independent board directors in respect to the bank, who are also independent towards the major shareholders of the bank

- Number of executives on the board

- The division of gender among the independent board directors - The average age of the independent board directors

- Average tenure of the independent board directors

Initially, our plan was to collect data from the ten largest banks in Sweden to use in our study. The collection was made by choosing the banks that in the year 2011 had the largest amount of total assets. Using a sample of ten banks would, in our opinion, cover a large part of the Swedish banking industry and provide a wide base of information to use when trying to come up with conclusions about the changes in the percentage of in-dependent members on the board. However, as the work of collecting the data begun, we struggled to find the needed information in the banks’ annual reports. The amount and quality of the data heavily differed between the banks and many annual reports were lacking informative data about the board members’ independence. The larger banks provided more clear information about this topic in their annual reports with spe-cific information about each board member, while the smaller banks presented a very limited amount of information about the topic of board independence which could not be used for our study. We tried to obtain closer information by e-mailing the banks, ask-ing for more specific information concernask-ing the independency of the board members. The answers from the banks were however weak, if any. Since no comprehensive analy-sis could be conducted because of the lack of information, we had to revise our sample and instead we narrowed it down to four banks. The banks that are used in our study are: SEB, Swedbank, Handelsbanken and Nordea. These banks provide useful data about the independency of their board members and much deeper information that we use to conduct a good analysis and interesting conclusions. It is, in our opinion, very un-fortunate that we were not able to use a broader range of banks. On the other hand, we find this revision necessary in order to carry out a solid research. Sweden does not have a very large amount of large banks, and we are therefore confident that these four banks are a large enough sample to use when performing our study.

The time frame that is used in our research is the period of 2001-2010. As changes in these types of contexts, in our opinion, take time we find it appropriate to use a fairly long time frame so that we are able to obtain evidence that show a clear pattern of changes. We find that the use of ten years as a timeframe increases our chances to

ob-tain more accurate information, and reduces the risk of obob-taining results that are strong-ly influenced by temporary events.

After the revision of the sample we find that the information provided by the four cho-sen banks still is very poor for the years 2001-2003. Regardless of this, we find it im-portant to include these years in our study as well in order to obtain a useful timeframe. The fact that the information is poorly presented these years is an observation we find interesting and that we include in our analysis.

3.3 Calculation of variables

When calculating the variables for this study the information is collected from the banks’ annual reports. The major parts of the variables are calculated as average num-bers and are put in relation to the total number of board memnum-bers. The denominator to-tal number of board members, which is used for most of the calculations, comprises the total number of members represented on the boards in the banks including employee representatives but excluding deputies. The variables are calculated in the following way:

- The percentage of independent directors in respect to the bank

Total number of independent directors in respect to the bank Total number of board members

- The percentage of independent directors in respect to the bank, who are also in-dependent towards the major shareholders of the bank

Total number of independent directors in respect to the bank and major shareholders Total number of board members

- Number of executives on the board

The information about this variable is primarily collected from the banks’ corpo-rate governance reports, where it is stated in text form how many executives the bank have represented on the board. In cases where such information could not be found, we instead compare the presentation of the directors on the executive board with the directors of the board of directors in the annual reports to see how many of the representatives on the executive board that also are present on the

board of directors. This is for the most part done for the earlier years, since the Corporate Governance reports provided by the banks were not as developed then as they are the latter years.

- The division of gender among the independent board members

The annual reports provided by the banks all include a presentation of the whole board with information about each of the directors, such as name, age, their in-dependence and how long they have served on the board along with pictures of all the members. From this information we have been able to obtain information about how many woman that have been serving on the boards and whether they are classified as independent directors. This information is also used when cal-culating average age and tenure of the independent directors.

Total number of independent female directors

Total number of independent board members with respect to the bank

- The average age of the independent board directors

The sum of the age of each independent director on the board Total number of independent board members with respect to the bank

- The average tenure of the independent board directors

The sum of the years each independent director has been serving on the board Total number of independent board members with respect to the bank

3.4 Data Collection

Our study comprises collection and analysis of secondary data. Secondary data consist of information that already exists and which, in some form, has already been published (Holme & Solvang 1997). It can take many different forms like for example published statistical data, surveys, academic articles and other documentations (Saunders et al, 2009). It comprises data that has been collected for other purposes than the research question we are investigating in this particular thesis and therefore, it is of great im-portance for us to first make assessments about whether the collected material and data

indeed is appropriate and valid for our study. Using secondary data is, in our opinion, appropriate and efficient in this case since much of the data that we need is relatively straightforward and easy to obtain.

The empirical data is collected by gathering information from the published annual re-ports of the four chosen banks. We also study literature and academic articles in order to deepen our knowledge within the area that our research concerns to receive a solid foundation to base findings and conclusions on. Important factors that are considered when choosing what kind of literature to use are how old the literature is, if the author has authority within the area and the quality of the source. The chosen literature func-tions as a help when planning the empirical phase and when analyzing the given results. Therefore, it is of great importance to choose literature with a high degree of caution (Merriam, 1994).

3.5 Reliability and Validity

The effect of the results one obtain when planning or performing a research project de-pends on two well known characteristics within the area of research method, namely va-lidity and reliability. These two concepts are related to each other and important to con-sider when conducting empirical studies (Olsson et al, 2011).

When conducting our study we strive to attain results with high reliability a well as high validity. Reliability essentially provides a measure of the extent to which a study pro-vides results that are consistent when repetitively performing the very same test. In or-der for a test result to be consior-dered as reliable, the same result should be obtained every time the test is performed, with the premise that the test is performed under the same conditions every time. The higher the consistency of the result, the higher reliability the study is considered to have. Reliability provides a measure of the stability of the scores that one receives when conducting a research test and hence, gives a measure of the ac-curacy of the results (Olsson et al, 2011).

There are many threats that can cause decreases in the reliability of data. Especially when tests include assessments of results, reliability is at risk to decrease. When the as-sessments of the results are performed by different persons, are highly subjective or if the assessments of the results are taken over a longer period of time, the results may end up in diverse ways which results in inconsistent unreliable data (Hartman, 2004). As

mentioned earlier, the data used to answers our research question is for the most part collected from our chosen banks’ annual reports. Since the data that we use is mainly presented in numbers, there is a low level of subjectivity involved. Annual reports are further on, considered as being reliable since they are audited and examined before they are provided to the public and no changes are being made to the reports after they have been published. Hence, we consider our data as having a high level of reliability.

We also take into consideration that the results that we obtain in our study are relevant in respect to the purpose of our thesis. It is important that the data that we collect in fact concerns the research question and the topic which the investigation regards. This is re-lated to the concept of validity and it is a vital part when performing a study (Saunders et al, 2009). The value and the usefulness of the collected data are measured by validity. Two questions concerning validity are good to consider when performing a study:

- Will we be able to obtained data that is relevant for the specific purpose and re-search questions of the thesis?

- Will the data collected be useful when making an analyze of the results and draw final conclusions? (Burell & Kylén, 2003)

We are keeping these two questions in mind during the whole process of our research and make sure that all the data that we use and that the results that we obtain are clearly linked to the purpose of our thesis. It is helpful to clearly specify the purpose of a study in order to increase the validity and only to use questions that directly concerns and are relevant to the specific research questions. It is important to remember that reliability does not automatically create validity and vice versa. Data and information may be per-fectly reliable without being useful at all as well as useful information may be incorrect and therefore have a high level of validity, but lack reliability (Burell et al, 2003).