BACHELOR THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Sustainable Enterprise Development AUTHOR: Mimmie Berglund & Sanna Nalin

JÖNKÖPING May 2020

Beyond Legal

Borders

Why SMEs in Sweden communicate its sustainability

performance, through a lens of stakeholder engagement

i

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our gratitude to all the people that have shown their support and contributed to the development of this study. In particular, we would like to thank the four participating enterprises for sharing their stories and experiences with us.

We would also like to give a special thanks to our tutor Oskar Eng for the excellent support, helping us through the process to create a study with confidence and pride. Along this journey, Oskar told us to symbolise our bachelor thesis with a pile of sand that we had to sculpt ourselves in order to build the castle.

And finally, here it is, out very own sandcastle, that was possible to build thanks to the involved parties’ great help and support.

Thank you, Mimmie & Sanna

ii

Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Beyond Legal Borders – why SMEs in Sweden communicate on their sustainability performance

Authors: Mimmie Berglund and Sanna Nalin Tutor: Oskar Eng

Date: 2020-06-09

Key terms: Sustainability, Sustainability Communication, Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprise (SME), Stakeholder Engagement.

Abstract

Background: Existing literature implies research about Sustainability reporting and SMEs to

be limited. SMEs are more vulnerable to economic pressure which may result in enhanced challenges in integrating sustainability practice. Because of SMEs’ vulnerability to financial pressures, and the law’s burden, the Swedish government, has excluded them from the law of sustainability reporting. Despite being excluded from the law, some SMEs are communicating on sustainability anyway, and the literature suggests that indirect forces could influence the strategies of sustainability performance.

Purpose: This thesis aims to explore the underlying rationale of why SMEs in Sweden

communicate on their sustainability performance, through a lens of stakeholder engagement.

Method: The study is built upon enterprise occurrence, where four SMEs based in the

Jönköping region has been interviewed with open- and semi-structured questions. The study follows an interpretivism approach with an exploratory nature of discovering the topic of SME and sustainability communication.

Conclusion: This study has shown that the answer to why SMEs communicate on their

sustainability performance is rather complex as it is hidden behind enterprise’s unique institutional structures with internal and external influences that shape decisions and attitudes. Throughout this study, it has been recognised that SMEs’ sustainability communication is performed beyond legal borders due to various reasons, and in particular the following; pressure from surrounding institutional structures; stakeholder relationships; and visions based on personal values and strong organisational core beliefs.

iii

iv

Table of Contents

1.

Introduction ... 1

2.

Literature ... 4

2.1 Assessment of Literature ... 4 2.2 Literature Review ... 5 2.2.1 Institutional Theory ... 5 2.2.2 Stakeholder Engagement ... 7 2.2.3 Communicating on Sustainability... 10 2.2.4 SMEs ... 112.2.4.1 Characteristics Differences: SMEs vs LEs ... 11

2.2.4.2 Leadership and Management ... 12

2.2.4.3 Challenges in Communicating Sustainability for SMEs ... 13

3.

Problem Discussion ... 16

3.1 Research Purpose and Research Question ... 17

4.

Method ... 19

4.1 Pilot Study and the Main Study ... 19

4.2 Data Collection ... 20

4.2.1 Selection of Enterprises ... 20

4.2.2 Interviews ... 20

4.2.2.1 Specifications for the pilot interview and the main interview ... 22

4.2.3 Ethical Considerations ... 22

4.3 Analysis ... 23

4.3.1 Pilot Analysis... 25

4.3.2 Main Data Analysis ... 25

5.

Pilot Study ... 28

5.1 Participant... 28 5.2 Empirical Data ... 28 5.3 Analysis ... 30 5.3.1 Sustainability Practice ... 30 5.3.2 Sustainability Communication ... 31v

6.

Empirical Data ... 34

6.1 Participants ... 34 6.2 Findings ... 34 6.2.1 Enterprise A ... 34 6.2.2 Enterprise B ... 36 6.2.3 Enterprise C ... 387.

Analysis ... 40

7.1 Owner Perception of Sustainability ... 40

7.1.1 Enterprise A ... 40 7.1.2 Enterprise B ... 41 7.1.3 Enterprise C ... 42 7.1.4 General Observations ... 43 7.2 Stakeholder Salience ... 45 7.2.1 Enterprise A ... 45 7.2.2 Enterprise B ... 47 7.2.3 Enterprise C ... 49 7.2.4 General Observations ... 51

8.

Conclusion ... 55

9.

Discussion ... 57

9.1 Practical Contribution ... 57 9.2 Limitations ... 579.3 Suggestions for Future Research ... 58

Reference list ... 59

Appendix ... 64

Figures

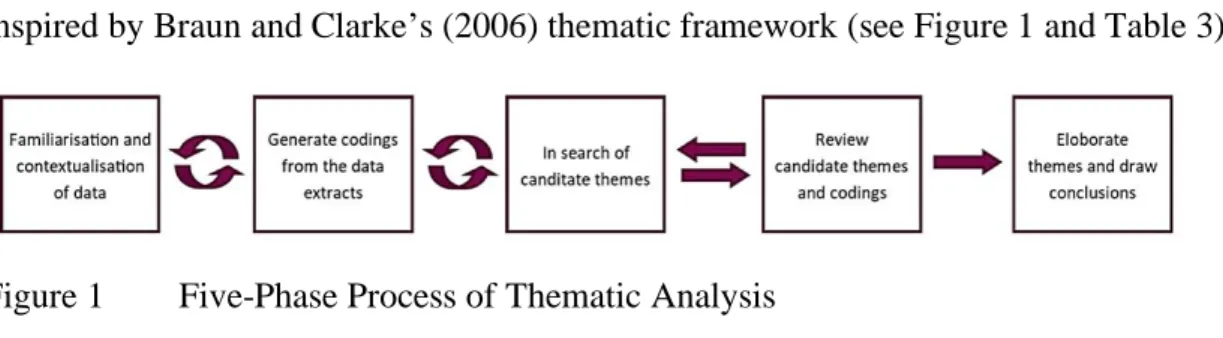

Figure 1 Five-Phase Process of Thematic Analysis ... 24Figure 2 Themes of the Main Analysis... 40

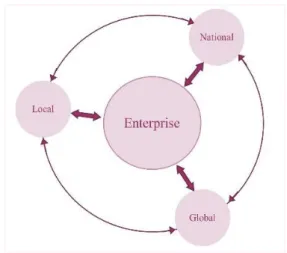

Figure 3 An Enterprise’s Interplay with its External Surroundings ... 54

vi

Tables

Table 1Interview Preparation: Pilot... 22

Table 2 Interview Preparation: Main ... 22

Table 3Description of the Five-Phase Process of Thematic Analysis ... 24

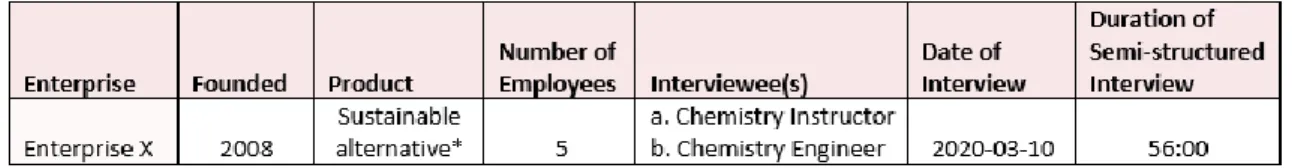

Table 4Overview of Pilot-Enterprise ... 28

Table 5Theme outline – Pilot Analysis ... 33

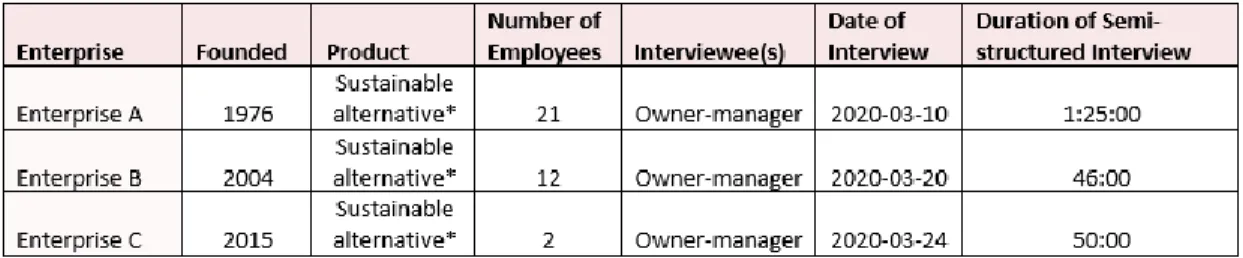

Table 6 Overview of Participating Enterprises ... 34

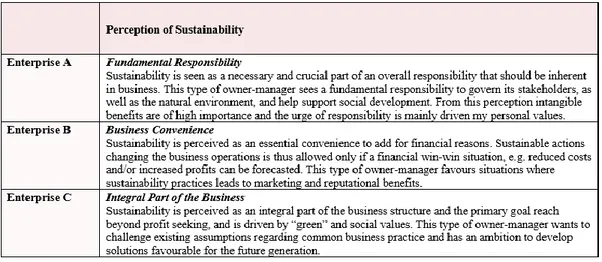

Table 7Perception of Sustainability... 45

Appendix

Appendix 1 ... 641

1. Introduction

In 2019, deforestation rates across the Amazon spiked with a number of 76.000 rainforest wildfires (corresponding to approximately 906.000 hectares), most of which were caused by human activity (WWF, 2019). This has been one of the worst years of rainforest wildfires in many years. However, despite this tremendous increase, this is not a new phenomenon. Before this tragedy, it was not globally known that farmers and loggers are purposely setting rainforests on fire for their own winning, e.g. growing crops for business. Due to the lack of information disclosure, these destructive activities have, for a long time, been globally unknown. Though today, it is commonly known that these fires are not just fires caused by natural disasters, and one could thank the debate that began when communication was increasingly set in motion. The global communication opens up for more extensive opportunities for action-taking. Thus, one could conclude that communication is a crucial and powerful tool invaluable in performing actions towards sustainable development.

Deforestation across the Amazon is, unfortunately, not the only tragedy revealing how human activities are causing ecological and social harm for selfish business reasons. However, for the latest decades, various stakeholders have increased the pressure on enterprises to do better, and to do good, and today there is an apparent trend in the concern of sustainability (Speziale & Kloveiné, 2014; Engert, Rauter & Baumgartner, 2016). This trend seems to be recognised by the generation of today’s adults and young adults, as they have shown to care and value humanity and nature more than generations before. The enhanced pressure creates a need for transparent activities, and thus some sort of communication on the enterprises’ actual performance. The call is no longer solely in financial terms.

External incentives for businesses to practice sustainability can, arguably, be beneficial for a nation and its governmental entities for several reasons. Sustainability performance amongst enterprises can enhance societal and environmental benefits. Also, by implementing sustainable actions, the nation is likely to be recognised as a caring role model, which, one can assume, is to be favourable for any country (Ministry of Enterprise

2

and Innovation, 2017; Malm, 2016). European Commission’s (2020) regulatory initiative on sustainability reporting1 aims to support the citizens to evaluate large enterprises’ (LEs’) sustainability performance, as creating a trustworthy atmosphere between civilisation and business.

As a consequence of acknowledged benefits, or even responsibility, more enterprises are today becoming regulated to perform and communicate its social and environmental practices. The European Union (EU), for example, has acknowledged benefits and are now regulating businesses within the union to, e.g. report on their sustainability performance (European Commission, 2020). In 2016, as a response to the EU-initiative on the sustainability reporting, the Swedish government implemented an extended legislation on large enterprises2 to report on its sustainability performance in a formal setting (Malm, 2016). Since LEs attain a remarkable power position in the marketplace, and thus also have significant influence over a vast population, of both enterprises and individuals, one can understand a rationale behind this inclusion. The logic of why solely LEs are included, and thus Small- and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs3) are excluded from this legislation, is the governmental incentive of decreasing the additional burden on enterprises. SMEs are evaluated and considered to be more vulnerable to the cost that follows this particular reporting legislation and are, therefore, excluded (Malm, 2016).

Even if the SMEs are excluded from the Swedish legislation on sustainability reporting, it does not mean that they are without the power to adapt and create a sustainable business future. Despite being relatively small in size, SMEs are described by economists as the “engine of growth” (Battisi & Perry, 2011). If looking globally, SMEs are fundamental to national economies as they roughly account for 90% of all enterprises (IFC, 2020), as well as contributes to around 33% of GDP in emerging economies (World Bank Group,

1 Directive 2014/95/EU - Non-financial Reporting. EU law obligates larger enterprises to disclose social and environmental

information over operations and how to manage challenges (European Commission, 2020).

2 Large enterprises (LE) is, along the study, defined as an enterprise with more than 250 employees. For a more detailed

definition, see concept list, p.3.

3 SMEs is a concept of included enterprises that is small- and medium-sized. However, what is defined as small, or medium,

to its size varies amongst nations and unions. For example, In Europe, SMEs are enterprises with less than 250 employees, turnover of less than 50 million euros or a balance sheet that does not exceed 43 million euros, while the United States defines an SME as an enterprise with less than 500 employees, and other criterions varies depending on the type of enterprise it is (OECD, 2018). Along this study, SMEs are defined as enterprises with less than 250 employees. For a more detailed definition, see concept list.

3

2020). Although no proportion of the SMEs resource consumption has been identified, one can, from the presented economic statistics, conclude that SMEs are likely to account for a considerable amount of the world’s resource consumption as well. Hence, both LEs and SMEs play a crucial role in a sustainable future through responsible business practice (OECD, 2018). When reflecting on such data, it becomes apparent that, in order to reduce the impact of unsustainable economic activities, there is a need to increase SMEs’, and not only LEs’, engagement of sustainable performances.

What influences the world’s enterprises to enhance their sustainability performance is, however, complex and not only driven by regulations (Delmas & Toffel, 2005; Mio, Fasan & Costantini, 2020). For instance, enterprises (as any individual or institutional structure) are subject to a complex network of institutional forces which influences and depends on its specific institutional environment (Furusten, 2013). External factors, from local to global levels, are affecting enterprises in many constellations, for example, with a profit-seeking economic system, enterprises are incentivised to perform and consider financial benefits prior to sustainability practices (Bobby Banerjee, 2014). It is also known that an enterprise’s structure, initiatives and performance is influenced by its constraints of resources, capabilities, employees, suppliers etc. (e.g. Dagiliene & Nedzinskiene, 2017; Furusten, 2013; Delmas & Toffel, 2005).

The enhanced institutional pressure on enterprises to perform on sustainability also requires them to communicate it somehow, as a way to show that they are implementing actions towards a sustainable future and that they are following regulated practises. For this reason, it becomes essential to delve deeper into the topic of sustainability communication. Even though research is gaining momentum in this particular academic field, there is an apparent need to add studies looking especially at SMEs, that have been given scarce acknowledgement by scholars.

This study aims at contributing to the literature with empirical observations in the sustainability communication for SMEs in Sweden, embedding a stakeholder-oriented view of institutionalisation.

4

2. Literature

______________________________________________________________________ In this section, the theorietical background of the study is presented together with a description of the method in assessing the literature. The assessment of literature has been an iterative process and is, for the sake of simplicity, presented before the literature review.

______________________________________________________________________

2.1 Assessment of Literature

At the beginning of the study, it was recognised that the topic is somewhat new and not yet very explored amongst scholars. A nation-wide scope with no specific limitation was thus appropriate. This was accomplished by searching through the databases ABI/INFORM, ProQuest and Emerald. In addition to these databases, a cross-check process was conducted in Primo, to find other relevant academic publications that happened not to be covered in the previously mentioned databases. By doing so, additional book chapters and journal articles were identified. Still, the strategic collection of literature has been strictly on peer-reviewed articles and -book chapters (see Appendix 1 for the first search strings).

The first search strings provided the authors with available literature reviews around the topic, which helped establish a comprehensive view where a “skeleton” of the literature assessment for this study was created, referred to as the first draft. The investigated literature reviews were also strategically used to collect suitable references commonly related in these reviews, and/or citations to find similar articles. This process was completed rigorously and transparently, and led to the following research question:

Why do SMEs in Sweden communicate on sustainability?

Once the research question was initiated, and the first draft of the literature was settled, the authors could recognise that the literature of the topic covers an extensive collection of concepts, conclusions and theories. Enterprises are complex in that sense, because, every enterprise is its own unique product of many different institutional creations, making it difficult to cover and integrate the extensive collection within only one paper.

5

In order to narrow the study and find a lens, a pilot interview and - analysis was conducted (described in section 4.2 and 4.3). The pilot-process led the research to the lens of a stakeholder perspective, and the research question became modified:

Through a lens of stakeholder perspective, why do SMEs in Sweden communicate on their sustainability performance?

The modified research question required additional search of the literature, and new search strings were, thus, organised (see Appendix 2). The lens applied to the study was a stakeholder perspective aiming to look at the external as well as internal stakeholder surroundings. Moreover, additional description of the study’s methods can be found in the fourth section (Method).

2.2 Literature Review

2.2.1 Institutional Theory

Institutional theory is based on assumptions that enterprises are affected by other enterprises or institutions. This reasoning is, however, not limited to organisations, the same idea applies to individuals, as it is unreasonable to be completely isolated from what is happening in the surrounding environment. External factors, from local to global levels, are affecting individuals in all constellations, private as well as for a workplace. Thus, if seen from an enterprise perspective, one can say that owner-managers are greatly limited from taking decisions in a completely autonomous manner (Cassells & Lewis, 2017; Furusten, 2013). Even though enterprises might feel able to act in whatever way they wish for, it is far from the truth as they are subject to a complex network of institutional forces depending on their specific institutional environment. Owner-managers must, therefore adapt and adjust to both its direct business relations but also to the surrounding environment to be seen as valid actors in the particular sectors they operate (Furusten, 2013).

Within this specific environmental surrounding, there are particular so-called institutional demands, i.e. what is collectively perceived as “correct” in a specific setting for the institutional environment. It is, however, essential not to forget that these demands are far from immobile as that would have meant that no change would ever happen. Instead, these commonly accepted understandings are continually evolving due to influences from

6

both global and local confluence of opinions and beliefs regarding organisation and management. These forces include societal factors such as ideas, rules, knowledge and norms, which are developed and distributed amongst enterprises. It is the result of a social interplay amongst many various actors that are creating, widening and safeguarding these factors that are shaping the elements of an institutional environment (Furusten, 2013; Dagiliene & Nedzinskiene, 2017). As these institutional demands become taken-for-granted and thus seen as a necessity amongst stakeholders, these demands or structures are said to be institutionalised, creating a pattern of normalised behaviour (Tolbert & Zucker, 1996). Bobby Banerjee (2014) argues that all enterprises operate within an economic system that favours financial prioritisation, signifying profit-seeking to be an accepted and the dominated nature for business.

If all enterprises are its own subject to external forces, all enterprises will, according to Masocha and Fatoki (2018), adopt similar strategies, and eventually, become the same over time. An example suitable in this context is the Swedish government that has implemented a (relatively) new legislation on LEs to report on its sustainability performance. This legislation was initiated in 2016 and required LEs in Sweden to publicly report on its non-financial performance, in a formal setting (Malm, 2016). There are various types of pressure, aside from the adoption of regulations, including following guidelines ethically and imitating successful competitors. These types of pressures are, however, not adapted uniformly; thus, the organisational responses are all shaped in different ways (Masocha & Fatoki, 2018).

Referring back to the previous example, the implementation of sustainability reports will differ from one enterprise to another. The reason for this is deeply inherent in the enterprise as sustainability can be interpreted in many different ways; representing a certain value (Masocha & Fatoki, 2018). In today's society, there has been an apparent shift towards increasingly valuing sustainability. Actors within the field, including the community, customers, NGOs, as well as other organisations, put external pressure on enterprises (Speziale & Kloviené, 2014). The implications of this follow that enterprises realise that they must apply a sustainable behaviour and implement sustainability values within their core business, whether it is due to legal requirements or other institutional pressures. At the same time, enterprises are bounded to integrate a financial approach in

7

order to survive and thrive as a business, meaning that an enterprise sometimes must compromise and priorities what values to consider by the time (Bobby Banerjee, 2014). This is seen as the underlying rationale for why organisational responses vary. The response of an organisation, however, depends on how influential the different stakeholders are, which is influenced by the enterprise’s characteristics.

Many stakeholders, with various interests, want to influence what they believe is essential; thus, the understanding of divergent organisational responses to change can be explained with institutional notions. However, it is difficult to describe the interplay between stakeholders, its different institutional expectations, and the enterprise itself with only institutional approaches (Delmas & Toffel, 2005; Masocha & Fatoki, 2018). With that said, one could claim that, since SMEs are not legally required to perform such a report but yet are communicating its sustainability performance, they must be driven by other institutional pressure than the regulatory ones (Mio 2020). Since these pressures are driven by the surrounding stakeholders (Engert et al., 2016), it becomes challenging to comprehend the interplay between an enterprise and its stakeholders to understand how an enterprise is being influenced and why some stakeholders are, in some instances, more influential than others (Masocha & Fatoki, 2018). In order to understand the phenomena of stakeholder salience, it is thus suitable to add the perspective of stakeholder engagement.

2.2.2 Stakeholder Engagement

The apparent trend where many stakeholder groups value sustainability concerns is becoming institutionalised (Speziale & Kloviené, 2014; Furusten, 2013). For the stakeholders to receive transparent information about the enterprise's sustainability practice, they demand some sort of communication. Various and coherent ways of communicating and engaging with stakeholders have been recognised and established, throughout the years of increased pressure (Speziale & Kloviené, 2014; Engert et al., 2016; Cassells & Lewis, 2017).

Even though “stakeholder” is a word with a, somewhat, everyday usage in business, it has, since the first beginning, been acknowledging the value perceived when buyers and sellers exchanged resources and capabilities. The aim of this exchange is to become better

8

off than before, for both (all) parties. Trade is thus seen as a creation of value (ecological, social and/or economic) between partners which is an inherent belief of stakeholder engagement (Freeman, 2017). There is, however, no uniform agreement on how to describe and envisage stakeholder engagement, it can take various forms and activities including, for example, conversations, written ideas, general availability and confrontation. By engaging with stakeholders, it becomes possible to create an understanding of what is expected when it comes to responsibilities taken by an enterprise seen from an economic; environmental; and ethical and social perspective (Rinaldi, 2013).

Gallego-Alvarez, Ortas, Vicente-Villardón and Àlvarez Etxeberria (2017) claim that an enterprise’s stakeholder orientation is influenced by the nation where it originates. They distinguish two approaches, namely communitarianism and contractarianism. These two approaches build on institutional notions and the influence of a nation’s belief in one enterprise’s interplay with its stakeholders, which is argued to influence the corporate governance structure of the enterprise. Communitarianism is described with a worldview where enterprises are social organisations with a social, as well as environmental responsibility. This should influence the enterprises to believe that they have an obligation reaching beyond solely maximising corporate financial performance. Communitarianism acknowledges that enterprises have a responsibility towards all stakeholders, and this perspective is particularly often seen in continental European countries. Contractarianism, on the other hand, consider enterprises with a primary purpose of maximising shareholder wealth. This perspective is considered to be a standard and encountered by the US and other Anglo American countries. This finding implies for one, of many, possible influences an enterprise has from its institutional surrounding (Dagiliene & Nedzinskiene, 2017; Furusten, 2013).

As a response to the contractarian perspective, Zakhem and Palmer (2017) claim that this view is problematic when it comes to reflecting business reality as it fails to consider the interplay with more than just one stakeholder. They suggest two styles within the view of a pro-stakeholder perspective, which includes a descriptive- as well as a normative aspect. The descriptive view is when the enterprise reflects on its stakeholders with rationality and by looking at factual- and descriptive claims and prioritising what is said to be agreed

9

upon as essential and implementing actions accordingly. The normative view, on the other hand, emphasises an ethical viewpoint, where the enterprise is looking at ethically desirable outcomes and take actions correspondingly. This view is thus aiming at recognising the intrinsic value of stakeholders.

Shnayder and Rijnsoever (2018) announce the vital importance for an enterprise to prioritise some sort of engagement with its stakeholders since stakeholders’ opinions, beliefs and worldviews can aid for a comprehensive understanding about present expectations, which can help with advancing sustainability performance. In order to create an effective relationship amongst stakeholders, it is recommended that stakeholders get the opportunity to look at the enterprise’s economical; environmental; and social behaviour, to let stakeholders provide criticism and expression of views and expectations in a timely fashion (Freeman, 2017; Shnayder & Rijnsoever, 2018; Rinaldi, 2013). This is, according to Rinaldi (2013), seen as an independent stakeholder-driven procedure that opens up for feedback and opinions aiming at continuously problematising and developing the enterprise’s performance, but also to decrease reputational risks that can be linked with unsustainable activities.

Further, Rinaldi (2013) contributes with two broad perspectives of what drives organisations to engage with their stakeholders. These perspectives may be viewed as two opposing sides of a continuum and are as follows:

The first perspective sees stakeholder engagement as holistic and as a way to extend and regards enterprise as inherently responsible for their integrated impact and thus, corporate accountability. This insinuates that all stakeholders, no matter how much power they possess, are equally important and should be treated with mutual respect to create long-term relationships.

The second perspective views stakeholder engagement as a strategic tool and a way to win or maintain the support of the most powerful stakeholders (most commonly financial power) that have a significant influence on the enterprise. The stakeholders are valued unequally, where the most powerful stakeholders also are the more important ones.

10

It has been apparent amongst scholars that analysing and engaging with stakeholders is essential for an enterprise’s existence and development (e.g. Wan Ahmad, Brito and Tavasszy, 2015; Freeman, 2017; Cassells & Lewis, 2017). However, by understanding the complexity of institutional influences on stakeholders and its demands, an enterprise can create more suitable decisions. For example, direct business relations are unquestionably crucial for enterprises. Still, it is also essential to comprehend that the legal, social and psychological environment in which all relations happen is equally important (Furusten, 2013).

2.2.3 Communicating on Sustainability

Throughout the last three decades, a new institutional business environment has been created, and due to internal and external pressures, social and environmental responsibility has emerged (Speziale & Kloviené, 2014; Engert et al., 2016; Borga, Citterio, Noci & Pizzurno, 2009). Enterprises are increasingly implementing and integrating social and environmental concerns which include an expansion of business wanting to develop towards corporate sustainability (Engert et al., 2016), as well as closer interaction with stakeholders to satisfy the demand of information-sharing regarding sustainability concerns (Speziale & Kloviené, 2014). As this pressure has been intensified over the last years, it has resulted in a rapid increase in disclosing information about social and environmental performance (Cassells & Lewis, 2017). In a similar vein, Wan Ahmad, Brito and Tavasszy (2015) validate the importance of public dissemination of information about sustainability practice. Further, they argue that this information is helpful for stakeholders as they get more in-depth knowledge regarding initiatives and performance towards the sustainability issues that are addressed by the enterprise. The usefulness, from an enterprise’s perspective, is reflected as the enterprise translates its sustainable commitment into indicators that can be measured. As a result, this will allow for the identification of improvement opportunities, as well as unlocking future potential strategies that can further increase the effectiveness. However, for communication to become valuable, it has to be communicated somehow. Thus, communication should be seen as a primary component to connect and coordinate activities within an enterprise (Holá, 2012).

11

There are some traditional ways of disclosing this type of information done in a more formal setting, including for example integrated reporting, EMAS systems, ISO 26000, sustainability reporting and other similar globally accepted frameworks (Malm, 2016; Kloviené & Specialé, 2014; Dagiliene & Nedzinskiene, 2017). Wan Ahmad et al. (2015) further discuss the importance of sharing information about sustainability practises via sustainability reports to create transparency towards stakeholders that are of high value, seen from both the stakeholders’ and the enterprise’s perspectives. Holá (2012) interprets any communication activity as an iterative and complex process of providing, trading and collecting information, which emphasises that the “right” style of disclosing information may differ depending on the characteristics of an enterprise and its institutional context.

Information sharing leads to transparency and helps to build trust and loyalty amongst employees (Holá, 2012), and other internal as well as external stakeholders (Speziale & Kloviené, 2014). In order to attain beneficial outcomes, it is crucial to view communication as a synergy between the visions and communication capabilities of the owner-manager(s) and the internal communication amongst all members of an enterprise. Additionally, communication could also be viewed as a continuous process that must be prioritised every day with room for feedback, which should help align the needs of stakeholders with the performance of the enterprise and create a common goal with its surrounding stakeholders (Holá, 2012; Cassells & Lewis, 2017).

2.2.4 SMEs

2.2.4.1 Characteristics Differences: SMEs vs LEs

It has been recognised that LEs and SMEs often differ in characteristics and does, therefore, not always face the same challenges and nature of pressure (Panwar, Nybakk, Hansen & Pinkse, 2017). However, stakeholder pressure seems to occur regardless of an enterprise’s size (e.g. Speziale & Kloviené, 2014; Engert et al., 2016; Cassells & Lewis, 2017).

Recent literature focuses primarily on listed enterprises (mainly LEs) when it comes to producing empirical data examining how an enterprise communicate and address social and environmental actions (e.g. Borga et al., 2009; Bos-Brouwers, 2010). Continuously, Bos-Brouwers (2010) and McCann, and Barlow (2014) states that SMEs differ

12

substantially from LEs in its characteristics, including the size in a financial and employment sense, technological expertise and the nature of stakeholder pressure. According to Elikan and Pigneur (2019), however, the main differences between SMEs and LEs are management and research processes. They argue that the LEs operate with visionary management based on extensive market research, while it is more common for smaller enterprises to have a vision based on an individual’s own (often the entrepreneur) values, personality and perception. More specifically, by having a leadership style that is informal and entrepreneurial, SMEs owner-manager has a clear advantage over LEs (Bos-Brouwers, 2010). Camilleri (2018) validates this argument and describes that, when discussing socially responsible activities, SMEs instinctively intertwine events together with its organisational culture, more than what LEs does, indicating for beneficial effects on the internal communication, e.g. increased trust and loyalty amongst employees. This seems to, generally, happen inevitably within habits and routines stimulated by authentic leaders as opposed to as a common practice in job descriptions or procedures.

2.2.4.2 Leadership and Management

Leadership at various stages in an enterprise shapes the organisational communications, climate and culture (Men, 2014). The leader within an SME has been recognised to play an even more significant role than for LEs, since owner-managers within SMEs oftentimes have closer proximity to its most vital stakeholders and is seen as the only linkage between these stakeholders (Baumann-Pauly, Wickert, Spence and Scherer, 2013), which requires a close connection. The leadership style of an SME owner-manager is thus often described as authentic and relationship-driven (Cassel & Lewis, 2017).

It has been recognised by Engert et al. (2016) that internal organisational influences and drivers are crucial for enterprises in sustainability strategies and the disclosure of relevant information, which seems to be highly dependent on the leadership style. Also, Men (2014) argues that employees are directly linked with organisational performance, and are representing the enterprise to external stakeholders as corporate ambassadors. From this statement, it is possible to say that it should be of high interest for the owner-manager to satisfy employee-organisation-relation to sculpt a productive workforce that cherishes relations with external stakeholders and uplifting organisational reputation. Hence, in this

13

sense, the owner-manager’s close connection to the core business amongst SMEs is seen to be highly favourable. This puts the leader in a prominent position; for example, the results from Camilleri’s (2018) study shows that SMEs owner-managers’ attitude is positively linked with stakeholder engagement. On the same note, Cassells and Lewis (2017) have acknowledged that SME-owner-managers that encompasses previous knowledge and experience on sustainability practice, mainly environmental practises, are more likely to implement such practices within its enterprise. Thus, the implementation of an authentic relationship-oriented leadership style that encompasses previous knowledge and prioritises internal stakeholders is favourable when it comes to establishing positive stakeholder engagement, both internally and externally.

Despite the crucial role of leadership styles, it is essential also to understand that owner-managers cannot obtain total control of the nature and scheduling of all decisions taken (Speziale & Kloveiné, 2014). It takes a comprehensive understanding of the surrounding environment to realise how institutional constraints affect decisions that are made to increase the level of control (Cassells & Lewis, 2017). For example, external factors for what is technically and economically attainable limits the owner-manager’s framework of actions. Thus, the skill of grasping the surrounding network of institutional structures is as important as the traits of an owner-manager, meaning that better decisions can be made by taking both the leadership style and the more comprehensive external understanding into consideration (Camilleri, 2018; Men, 2014; Engert et al., 2016).

2.2.4.3 Challenges in Communicating Sustainability for SMEs

SMEs, just as LEs, are confronted with augmented expectations from stakeholders requiring them to act considerately with respect to social (Camilleri, 2018) and environmental management (Cassells & Lewis, 2017). Even though these expectations are increasing, Shields and Shelleman (2015) are recognising that the majority of SMEs do not have a structured approach when it comes to accommodating this changing environment, which could be problematic if the drawbacks of failing the adjustment increase the level of burden to a damaging state. One possible scenario could be if regulatory institutions would put legal pressure on SMEs to report on its sustainability performance with financial punishments if failing to do so.

14

Furthermore, according to both Cassells and Lewis (2017) and Bos-Brouwers (2010), SMEs often face limitations in the implementation phase of environmental management practices, which will hinder the ability to communicate, and thus engage, with stakeholders. On the same note, Baumann-Pauly et al. (2013) express that SMEs struggle with communicating its social sustainability performance to external stakeholders. Some of the underlying factors generating challenges that SMEs’ face when implementing environmental practice include resource scarcity, limited absorptive capacity, and the absence of security to achieve long-term change over short-term financial security. A noticeable drawback with resource- and capability demanding nature of sustainability practises is that SMEs choose, due to lack of convincing practical relevance, not to prioritise the implementation of sustainability (Verboven & Vanherck, 2016; Elikan & Pigneur, 2019; Arena & Azzone, 2012). This is problematic as communicating sustainability performance is a way for an enterprise, as previously mentioned, to engage with its stakeholders.

Even though SMEs face various limitations, a positive attitude on environmental responsibility has been recognised amongst a number of enterprises, which increases the likeliness of implementing sustainability practises (Cassells & Lewis, 2017). In order to perform within the resource constraints, Shields and Shelleman (2015) see simplicity, flexibility and straightforward manner as crucial factors to include when integrating sustainability consideration into its business model. On the same note, Arena and Azzone (2012) recognise that genuine and proactive (Borga et al., 2009) collaboration with stakeholders is crucial to create a clear consistency with current accountability requirements of voluntary reporting. Irrespective of what factors that correspond to the most “optimal” activities for an SME, it is argued by Speziale & Kloviené (2014), Engert et al. (2016) and Cassells and Lewis (2017) that stakeholder engagement is seen positive as the commitment is valuable for enterprises.

Cassells and Lewis (2017) argue that, SMEs themselves commonly see sound environmental practices as a responsibility, but that the individual enterprise should choose to implement it on their own terms. The strive towards autonomy is likely to be desirable amongst SMEs, which is arguably reasonable as they are not as restricted with

15

regulations as LEs are (Panwar et al., 2017). This autonomous nature is seen as acceptable by Cassells and Lewis (2017) only if it emerges into positive approaches towards sustainable actions. Supposedly independent characters, however, comes with risks as it might end up with neglect and lack of efforts towards sustainable practices. Due to this inherent dichotomy, it is essential to look at what is argued to be the most feasible starting point to ensure a motivated workforce taking sound environmental actions. In reality and theory, it is claimed that a balance between legal compliance and organisational initiatives provides the most favourable situation to accomplish outcomes that are positive for both the business bottom line as well as the sustainability as a whole (Cassells & Lewis, 2017).

16

3. Problem Discussion

______________________________________________________________________ This section aims to identify the relevance of the studied topic by discussing the main points from the reviewed literature and provide the reader with the logical reasonings to the topic. At the end of this section, the purpose and research question is formulated. ______________________________________________________________________ In Sweden, and globally, there has been an apparent shift towards increasingly valuing sustainability. As the climate continues to change, the shift towards increased pressure on business seems to follow accordingly. Today, the external pressure on enterprises to implement sustainability behaviours is increasingly being viewed as a common practice amongst various institutional structures (Speziale & Kloviené, 2014; Engert et al., 2016; Cassells & Lewis, 2017). One example is the Swedish government that has implemented a (relatively) new legislation on LEs to report on its sustainability performance (Malm, 2016). This legislation was initiated in 2016 and required LEs in Sweden to publicly report on its non-financial performance, in a formal setting. Legal requirements are however far from the only type of external pressure an enterprise is facing (Furusten, 2013). As the trend of sustainability concerns rise and develop globally, all enterprises will be affected by other significant levels of pressure, regardless of size and characteristics. This may be because, as a trend expands and develops, it will eventually become institutionalised in various stakeholder settings, creating a normative behaviour that is not driven by legal forces (Tolbert & Zucker, 1996), a phenomenon given extra emphasis throughout the study.

Even if SMEs are excluded from the non-financial reporting legislation, it has been recognised that some SMEs are communicating on its sustainability performance, anyway. This observation could possibly explain that the underlying rationale behind what motivates an SME to communicate its sustainability performance does not only derive from a legal pressur (Mio, Fasan, & Costantini, 2020; Delmas & Toffel, 2005; Furusten, 2013). Yet, SMEs are faced with various challenges hindering them from implementing sustainability practises, including resource scarcity as well as limited absorptive capacity (Panwar et al., 2017; Bos-Brouwers, 2010; McCann & Barlow, 2014).

17

These hurdles make it essential to further investigate why SMEs actually communicate on their sustainability performance, in order to empirically contribute to the existing literature, and practically inspire SMEs to either begin or continue with evolving its sustainability communication. Because, SMEs play a crucial role for the future that we are, hopefully, heading towards.

Most of the existing literature is discussed with a focus on listed enterprises (mainly large), and some researchers (e.g. Speziale & Kloveiné, 2014; Gallego-Alvarez et al., 2017) seems to believe that, since it is seen as beneficial for LEs to communicate on its sustainability performance, it should be beneficial for and bring added-value to SMEs as well, but with scarce empirical justification. There are obvious characteristics differences between SMEs and LEs, making the broad and generalised findings from literature on listed enterprises not very convincing to be applicable for smaller enterprises. This indicates for a gap in the literature that describes SMEs’, distinguished from LEs’, value-creation of sustainability performance and the followed communication. The literature looking into SMEs’ value-creation of sustainability practice is limited and does not cover a comprehensive understanding as findings are looking at different structures of enterprises as well as their external surroundings such as stakeholders. As already touch upon, SMEs has, just as LEs, a crucial role in responsible business practice for a sustainable future, which argues for the essence of investing in more research that covers SMEs’ performance, consequences and reasonings.

For these occasions, it became compelling to fill the identified gap and investigate in subjective and practical reasonings covering why it seems to be of added value to communicate its sustainability performance for an SME. However, the recognition of the studied literature’s extensive collection of concepts, conclusions and theories narrowed the study (argued for, and described, in section 2.1) by applying a lens of stakeholder engagement.

3.1 Research Purpose and Research Question

The purpose of this study is to explore the underlying rationale of why SMEs communicate on their sustainability performance. The contribution of empirical data aims to inspire SMEs in evolving their sustainability communication. To fulfil the purpose, the

18

study will answer the following question: In a lens of stakeholder engagement, why do SMEs in Sweden communicate on its sustainability performance?

19

4. Method

______________________________________________________________________ This section part follows a methodological clarification of the study, followed by an in-depth description of the qualitative methods, including data collection, ethical considerations and data analysis. The first part of the method, i.e. the assessment of literature has, for the sake of simplicity, been dispositioned as an introduction to the literature review.

______________________________________________________________________ This study is exploratory and follows an interpretive philosophy4 (Corbin & Strauss, 2008) where the authors have subjected the nature of reality to its context, which means that the authors considered, for example, subjective meanings, details of a particular situation and motivating actions as valid knowledge. With that said, the reality is considered to be subjected to its context5 where, e.g. motivating activities, details of a particular situation and subjective meaning6 has been regarded as valid knowledge along with the study.

4.1 Pilot Study and the Main Study

When the first “draft” of the literature was conducted, the lens was, as earlier mentioned, not yet discovered, and found by observing an SME in its subjective nature, supported by the yet reviewed literature. This procedure is, hereafter, referred to as the pilot study.

The pilot study and the main study has been undertaken with two different purposes; thus, these two procedures also contain different characteristics, meaning that certain methodological verifications were applied throughout each process. This will be further defined in section 4.2.2.1 and 4.3. The main parts of the following sections describe the common method for both the pilot study and the main study where sub-headings define the specific differences.

4 Interpretivistist philosophy allows the researchers to explain observations and elements by integrating subjective contexts

(Duignan, 2016a)

5 Ontology refers to what the research considers as the nature of reality. One can explain ontology as the systems of belief that

announce the understanding of what forms a fact (Dudovskiy, 2019).

20

4.2 Data Collection

4.2.1 Selection of Enterprises

The enterprises under study were selected, by the authors, with help from two consultants with a sustainability focus within their profession, one sustainability reporting consultant, and one accredited business coach and mentor. In order to match the selection of participating enterprises with the purpose of the thesis, as well as the identified research problem, specific criteria were defined. These criteria entail that the enterprises should be (i) an SME7 that (ii) somehow involve sustainability within their practice.

Moreover, the enterprises selected for the study were situated within the Jönköping region. This was, however, not a criterion as enterprises outside this region were contacted as well. The main principle of the geographical specifications was to choose enterprises that were, according to the authors, within a reasonable distance to allow for the possibility of a physical meeting. Also, the study is sector-wide, and thus no emphasis was put on any specific sector in the selection. The sustainability consultants recommended to contact members of CSR Småland as these enterprises, somehow, include consideration of social responsibility within their business. Keeping these criteria in mind and thus applying a judgemental sampling method8, ten suitable enterprises were selected, eight of which found on the members-list of CSR Småland 9 and two of which had been in collaboration with the Sustainable Enterprise Development program in previous courses. Out of these ten enterprises, four enterprises from different sectors agreed to be a part of the empirical data of this study.

4.2.2 Interviews

The interviews were held in Swedish, as this is the native language of the participants of the study, as well as for the authors. The choice of language was strategic as it helped to get a natural flow throughout the interviews and to gain well-formulated answers that

7 Enterprises with less than 250 employees. For a more detailed definition of SME, see concept list.

8 Judgemental sampling method refers to a method in which the samples are chosen according to certain criteria based on

knowledge and judgement of the researcher (Duignan, 2016b).

9 CSR Småland is a networking entity with the aid to help enterprises to learn about practical ways to implement actions for a

21

probably would have been shorter and more concise if the interviews would have been held in English because of potential language barriers and limitations.

The data were conducted through interviews that were held by, in total, three physical meetings and one online meeting. The physical meetings were arranged at the workplace of the participants, i.e. in a setting where the participant(s) felt safe and comfortable, gaining an understanding of the organisation and its culture and atmosphere. Throughout the non-physical interview, it was not possible to gain the same experience, which made it more challenging to unlock this in-depth understanding. However, the authors yet experienced a genuine connection throughout the interview and interpreted the participants just as comfortable as the other participants. As this is an interpretive study, the focus is to gain a comprehensive understanding of the viewpoint of the participants, and it is reasonable to assume that comfortable participants are more willing to provide more evaluated answers, and less likely to reject questions. Therefore, a pleasant environment for the participant(s) was, hence of high priority for the authors.

All interviews were semi-structured with open questions aiming for the authors’ possibility to recognise the jargon needed to keep an atmosphere where the participants feel confident. The semi-structured interviews also allowed the authors to ask additional relevant questions throughout the interview session, which was needed for the study as it follows an exploratory purpose, where areas of investigation were created alongside interactions between the participant(s) and the authors.

Throughout the interviews, the flow varied alongside the jargon of and the connection amongst the participants and the authors. For example, some of the participants were given a few more “warm-up” questions while other participants wanted to get right into the so-called “core and purpose” of the interview. Thanks to the semi-structured style of the interviews, this was made possible and allowed for a less “strict” form aiming at gaining more significant qualitative answers. Also, all participants were provided with questions in advance, which was to give the participants a chance in providing solid and well-thought-on answers since it was not assumed that the participants would have an answer to all questions right away. This procedure has been of value for the study in the collection of qualitative data.

22

4.2.2.1 Specifications for the pilot interview and the main interview

When it comes to characteristic differentiation of the pilot interview and the main interview, there are some notable things necessary to mention. The pilot study was aiming at grasping a broad view and understanding and thus consisted of broad and open questions (see Table 1). After the pilot interview was completed, the authors evaluated the interview with self-reflecting questions regarding, for example, the suitability of the language and understanding of concepts, scope of relevancy and the participant’s experience level of comfortability and engagement. After the interview was evaluated, refinements were completed, and a niched angle was spotted, and a refined structure for the upcoming main interviews was created. The pilot data was also analysed before modifying the interview questions making it possible to include the applied lens within the niche of the questions (see Table 2).

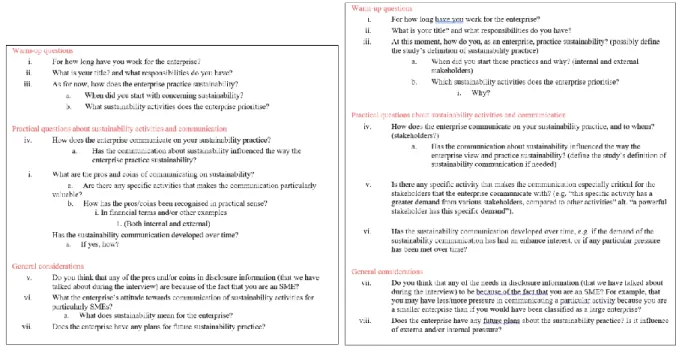

Table 1 Interview Preparation: Pilot Table 2 Interview Preparation: Main

4.2.3 Ethical Considerations

Throughout the study, no formal ethical consideration guidelines were formulated nor signed between the parties, but much emphasis was put on such reasonings. Some important notes that were taken into consideration followed, e.g. to treat the participants with respect and gratitude, and by no means, risking misunderstandings that could

23

develop feelings of being undermined. The participation was voluntary, with the right to withdraw at any time, which was communicated in written form early in the process. Also, the purpose of the study was communicated with the request for involvement. The purpose was communicated to create a transparent relationship and a safe culture between the parties. These considerations fall under the same reasoning that is stated by Collis and Hussey (2014) in the book Business research: a practical guide for undergraduate & postgraduate students.

Every interview was audio recorded, and this was asked in written form in advance of the interview and then agreed upon in verbal form just before the interview started. The study does not, per se, touch upon subjects that are generally seen as a risk for harming participants’ occupation nor the enterprises’ reputation. However, it is still critical to take these potential risks with thoughtful attention, hence it was communicated, in advance but also throughout the interviews, that the participants were allowed to neglect questions.

Another important ethical consideration includes the author's capability of objectiveness. Since the authors are studying sustainable enterprise development, and are thus passionate to locate positive correlations therein, there is a risk that the authors unconsciously seek patterns that correspond to their beliefs. This phenomenon, also known as confirmation bias10, could possibly have destructive effects on the authenticity of the study. For this reason, one might argue that it is impossible to conquer this issue fully, yet the authors did their best to remain objective and be conscious of the tendency of this issue.

4.3 Analysis

The method used in analysing the data was of a thematic structure11, with the reasoning to, early in the process, be able to link the empirical data with the research purpose as well as the research question. The aim with thematic analysis was, however, to identify somewhat patterned responses or meanings within data sets (themes) to develop findings

10 Confirmation bias refers to the tendency of one to deal with information by looking for information that is in line with

existing beliefs of one (Confirmation bias, 2020).

11 According to Braun and Clarke (2016), thematic analysis is a method for qualitative analysis where patterns are identified

with codes and themes. Thematic analysis does not include any specification regarding style, struct ure nor guidelines, allowing for a wide flexibility.

24

relevant to the research question (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Holloway & Todres, 2003). Further, another main reason for choosing a thematic approach was due to its flexibility allowance, making it possible to make active choices regarding the particular form of this analysis which has been important in this research since there have been two analyses (pilot and main) with two different purposes. Since the study has an interpretivist nature, aiming at looking subjectively at various enterprises' reasonings towards its communicated sustainability performance, a thematic analysis was seen as a good fit for the study. With this method, it was possible to include useful data and eliminate the irrelevant data in order to establish data sets correlated to the research question.

The thematic approach of the analysis was managed through a five-phase process, inspired by Braun and Clarke’s (2006) thematic framework (see Figure 1 and Table 3).

Figure 1 Five-Phase Process of Thematic Analysis

25

Though the approach of analysing the two different data-set has been thematic, the aim, and thus characteristics, of the two analyses were different.

4.3.1 Pilot Analysis

When analysing the pilot data, the aim was to seek for a narrowed lens for the study; hence the pilot-analysis had an inductive12 character, with a purpose to

not influence the coding and themes with any specific theoretical framework. According to Braun and Clarke (2006), this pilot analysis would be more of a semantic13 character since the intention was not to look beyond what was being said throughout the interviews.

With these guidelines, the five-phased process structured the analysis. Since the questions asked throughout the interview were open and broad, the answers provided were well-formulated and nuanced, yet widely dispersed. Align with the study’s purpose, the pilot analysis aimed to develop rather broad themes that could potentially be relevant for other SMEs than just the pilot enterprise (hereafter referred to as Enterprise X). After initial codes were created, clear patterns could be identified, accompanied by interview extracts that linked with sustainability and communication as candidate themes. These two themes were easily motivated since the existing literature background covered these parts in particular. After reviewing the themes once again, and looking for patterns in semantic content, one somewhat obvious pattern was identified. Since both sustainability and communication could be seen as parts of an overarching head-theme, namely stakeholder engagement. This head-theme seemed to open up for more comprehensive understanding seen from various perspectives rather than just from the enterprise point of view. For this reason, this theme was later added as the lens for the upcoming main analysis.

4.3.2 Main Data Analysis

The analysis of the main data was driven by the theoretical lens, stakeholder engagement, which indicates for the analysis of the main data to be deductive14, making the codings

12 Inductive research is referred to as a study moving from an observed empirical reality into theory (Collis & Hussey, 2014) 13 A semantic approach aims at recognising themes within the surface context of the data, hence no observation beyond what

has been said or stated by the participants (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

14 Deductive research is referred to as a study that moves from a conceptual and theoretical structure into findings that are

26

and themes interpreted by the authors. For this reason, the process of analysing the main data has been constructed using a latent15 approach, where the meaning beyond the words in the collected data have been interpreted when identified, to examine an underlying essence behind the statements. In order to analyse the participating enterprises to its own context, the enterprises are analysed separately.

With a more narrowed scope and niche, as well as more detailed interview questions, it was somehow easier to become familiarised with the data as clear patterns between the literature and the data was instantly discovered.

In order to spot reasonings behind why the various enterprises communicate its sustainability performance, codes were developed using interview extracts that described any underlying connection with stakeholders and the participating enterprise’s view. At this stage, the authors went back to the familiarisation phase and mapped out differences and similarities with the participating enterprises to locate possible patterns as well as uniquenesses amongst the enterprises. With this information mapped out, the authors tried to target underlying patterns that could answer the purpose of communicating its sustainability performance, and various incentives could be spotted. Throughout this phase, the authors combined their personal impressions together with codes and data extracts to develop a subjective understanding, illustrating parts of the iterative process (see Figure 1).

Since the aim of the research question was to use the lens of stakeholder engagement, not only the incentive seen from the participant view was used but also a more holistic view, looking at the enterprise’s surrounding environment. When clustering together the codes from the interview extracts, two emerging “main themes” were spotted, suitable to the research question, namely Owner Perception and Stakeholder Salience. Separately, these main themes aim at describing an internal as well as an external perspective and in

15 A latent approach aims at recognising themes outside the surface context of the data, meaning that it is expected to look for

27

conjunction with each other they aim at providing a nuanced way of analysing. For this reason, it is vital that these are understood in combination with each other.

28

5. Pilot Study

_____________________________________________________________________ This section aims to outline a summary of collected pilot data, as well as the analysis from the semi-structured pilot-interview. The analysis will evaluate and discuss the data in themes following the order – Sustainability Practice, Sustainability Communication, and Stakeholder Engagement. A table explaining the justification of the themes is provided at the end of this section.

______________________________________________________________________

5.1 Participant

Table 4 Overview of Pilot-Enterprise

5.2 Empirical Data

Enterprise X aims at creating a circular loop for the purchased material, that after the recycling process becomes the product they sell. Though the Enterprise X’s production and product can be seen as a contribution in sustainability actions, the enterprise itself expresses its resource scarcity, especially in terms of employees, to develop their sustainability practice even further. Amongst the employees at Enterprise X, being few at the workplace is seen as “a part of the charm in being a small enterprise” since this motivates them all to be highly engaged with the business, even if there is an apparent wish of being able to do more than today, in terms of sustainability practice.

The enterprise is a member of CSR Småland, which is a networking entity aiming at helping enterprises to learn about practical ways to implement actions towards sustainable development. The engagement in CSR Småland is a way to become inspired to, e.g. create a circular business model and gaining valuable network opportunities towards enhanced sustainability business practice.

29

The sustainability communication mainly occurs amongst suppliers and partners, not as a common practise but rather on request if, for example, code of conduct or certifications are being asked for. The largest pressure is from large actors that are putting the pressure on communication in terms of requiring, for example, environmental certifications.

Sustainability communication is not a high priority for Enterprise X as they do not see it as an improvement area that ought to be focused on for now. This is mainly because Enterprise X has very few employees and prioritise other areas of improvements. Despite the low level of priority, communication channels are planned to be developed, where their webpage is one of the main focuses. This is to make the enterprise’s every-day sustainability practice becomes more visible and easier to access.

Enterprise X is engaging with various stakeholders; for example, the enterprise itself is putting pressure on its suppliers concerning test-samples on the material before it is bought. This is since Enterprise X wants to make sure that the materials that they purchase reach a desirable level of quality. However, this type of pressure can sometimes be difficult as the demand will require an added activity for the supplier, which is seen as irrelevant to some suppliers. This situation of clashing interest puts Enterprise X on the urgency to find a balance when engaging with its supplier. From Enterprise X’s perception, putting too much of a pressure on the supplier could leave the enterprise without any supply, while at the same time purchasing material with lower quality will require more resources of the production process. Along with this, a dilemma for Enterprise X appears where the enterprise needs to consider their reputation, because this type of pressure and engagement could symbolise what the enterprise represents, which today is, according to the enterprise itself, an enterprise delivering a sustainable, recycled, product with high quality.

Also, Enterprise X is heavily reliant on its distributors, since the enterprise is using its distributors as a communicator about their sustainability performance of the production. Enterprise X further finds it challenging to convince its customers about the quality of their products. It is common that the distributors, and thus the consumers, think that it would be logical if the recycled product does not keep the same quality and capacity as non-recycled products, because that would be too good to be true.

30

The response and engagement from governmental institutions and local authorities, however, is perceived as positive. This is said to be mainly because these stakeholders have an interest in helping Enterprise X, due to its contribution towards sustainable actions for the consumer. The survival of the enterprise is crucial for the governmental institutions and the local authorities, not only because the enterprise contributes to the nation’s sustainable development, but also because they are customers of Enterprise X.

For Enterprise X, the internal stakeholders are mainly the employees where everyone is, somehow, involved within all steps of the process for the product. This is with high engagement where decisions can be made quickly, not only because of good internal communication but also because of trust and every employee’s high involvement and understanding of the production process.

5.3 Analysis

5.3.1 Sustainability Practice

Throughout the last decades, enhanced pressure on enterprises to take social and environmental responsibility has emerged (Speziale & Kloviené, 2014; Engert et al., 2016). The fact that Enterprise X’s product is a more sustainable alternative to existing products illustrates Enterprise X’s aim of satisfying a customer need in conjunction with this enhanced trend. The enterprise’s main sustainability practice is the product, hence the entire business model includes performance on sustainability in some sense. In other words, the main sustainability practice for Enterprise X is to satisfy customers and consumers of the product. This commitment is in line with Engert, et al.’s (2016) acknowledgement of enterprises practice on sustainability because of the increased demand. However, for Enterprise X to satisfy their customers, a trustworthy relationship with the suppliers is vital to guarantee that the products remain at a high level of quality. The engagement with various stakeholders of Enterprise X seems to be of value for the enterprise’s reputation, and since the consumer sees value in using a more sustainable alternative, this practice could be beneficial to communicate with the purpose to create some sort of loyalty (Shnayder & Rijnsoever, 2018).