Keeping SaaS business

clients loyal

An exploratory multi-case study on how to design loyalty initiatives

MASTER: Digital Business

THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Digital Business

AUTHOR: Lena Katharina Kaiser & Anna Federika Würthner TUTOR: Ryan Rumble

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Keeping SaaS business clients loyal - An exploratory multi-case study on how to design loyalty initiatives.

Authors: Lena Katharina Kaiser and Anna Federika Würthner Tutor: Ryan Rumble

Date: 2020-05-18

Key terms: Customer Loyalty, Software-as-a-Service, Business-to-Business, Loyalty Initiatives, Loyalty Actions

Abstract

Business-to-business customer loyalty management is an essential and long-standing theme in business research and practice. Loyal clients are of great importance within Software-as-a-Service (SaaS), as the business model relies strongly on long-term business relationships, e.g. due to subscription models. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, there is no study on how to design loyalty initiatives used in business-to-business SaaS relationships yet. Therefore, our thesis asks the question “How can loyalty initiatives be designed to improve the loyalty of SaaS business clients?”. By applying a qualitative research methodology with multi-case studies, we were able to investigate the status-quo of customer loyalty management by looking at the vendor side and then analysing the perception of loyalty initiatives, with respect to the client’s perspective. A broad number of in-depth empirical data was collected in semi-structured interviews conducted with employees of six SaaS vendor firms and seven of their clients. As we used an abductive approach, we were able to compare our findings with the existing literature and extend previous theory. Our interview findings were then clustered into eight dimensions, which were based on the customer lifecycle, and various initiatives have been assigned to them. All initiatives included several actions performed by the vendors, which were then classified into three categories, according to how important it was perceived by their clients. We concluded our research with the ‘Design Guide for Loyalty Initiatives’ that summarises our findings and provides an overview for SaaS vendors to review and adjust their initiatives. Hence, we deliver valuable insights for SaaS vendors to gain a deeper understanding of their clients’ needs and to, in turn, prioritise their performed loyalty actions and allocate their budget accordingly.

Acknowledgement

Since the conceptualisation of this thesis would not have been possible without the contribution of many individuals, we would like to take the opportunity to thank these people.

First and foremost, we would like to thank the interviewed participants for taking the time to share their knowledge and experiences with us. Their valuable insights enabled us to conduct this research and their enthusiasm has further increased our interest in the topic and the SaaS industry. Second, we would like to thank our thesis supervisor Ryan Rumble, who shared his broad knowledge about business research with us and gave us valuable tips on how to improve our study. His support and guidance helped us to overcome the different obstacles, that we faced during the conception of this thesis. Moreover, we are grateful for the insightful feedback from the other thesis students of our seminar group.

Further, we would like to thank our friends and families who accompanied us through this nerve-wracking time and supported us emotionally. A special thanks goes to Ashly Vackachan whom also provided us with tips on how to improve our academic writing in English.

Finally, we also want to thank Jönköping International Business School, as this thesis is the result of our two years of study. We are grateful that we have been able to be amongst an exciting student body, great teachers and amazing people from all over the world.

Table of contents

1

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Problem ... 2 1.3 Purpose ... 32

Literature review ... 4

2.1 Cloud computing and the Software-as-a-Service business model ... 4

2.1.1 Introduction to cloud computing ... 4

2.1.2 The Software-as-a-Service business model ... 5

2.2 From a goods- to a service-dominant management strategy ... 6

2.3 The concept of customer loyalty ... 8

2.3.1 The definition of customer loyalty... 8

2.3.2 Antecedents of customer loyalty ... 10

2.3.2.1 SaaS performance ... 10

2.3.2.2 Interpersonal bond ... 12

2.3.2.3 Customer satisfaction ... 14

2.3.2.4 Switching costs ... 16

2.3.3 Initiatives that contribute to customer loyalty ... 18

2.3.3.1 The concept of loyalty initiatives and its delimitations ... 18

2.3.3.2 Defining loyalty initiatives in SaaS ... 19

2.3.4 The model of the customer loyalty construct ... 22

3

Methodology ... 23

3.1 Research philosophy ... 23

3.2 Research approach ... 24

3.3 Research design ... 25

3.4 Research method ... 26

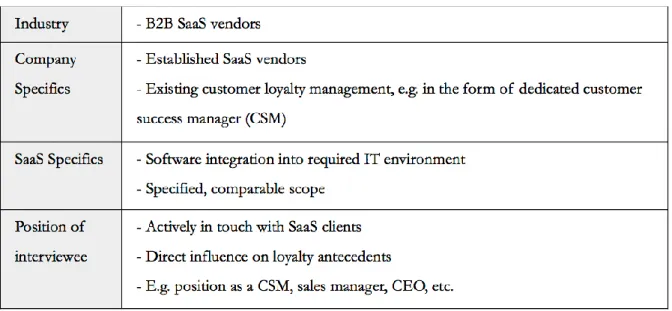

3.4.2 Sampling ... 28 3.5 Company cases ... 30 3.5.1 Vendor cases ... 30 3.5.2 Client Cases ... 31 3.6 Data collection ... 32 3.7 Data analysis ... 33 3.8 Research quality ... 35 3.9 Research ethics ... 37

4

Findings and Analysis ... 38

4.1 Data structure ... 38

4.2 Eight dimensions within the SaaS lifecycle ... 40

4.2.1 Project Phase ... 40

4.2.1.1 Findings of the status-quo of the project phase ... 40

4.2.1.2 Description and analysis of the project phase ... 41

4.2.2 Training ... 43

4.2.2.1 Findings of the status-quo of training ... 43

4.2.2.2 Description and analysis of training ... 44

4.2.3 Monitoring and Maintenance ... 46

4.2.3.1 Findings of the status-quo of monitoring and maintenance ... 46

4.2.3.2 Description and analysis of monitoring and maintenance ... 49

4.2.4 Support and complaints management ... 52

4.2.4.1 Findings of the status-quo of support and complaints management ... 52

4.2.4.2 Description and analysis of support and complaints management ... 53

4.2.5 Feature development ... 56

4.2.5.1 Findings of the status-quo of feature development ... 56

4.2.5.2 Description and analysis of feature development ... 58

4.2.6.1 Findings of the status-quo of events and workshops ... 60

4.2.6.2 Description and analysis of events and workshops ... 61

4.2.7 Recommendations ... 62

4.2.7.1 Findings of the status-quo of recommendations ... 62

4.2.7.2 Description and analysis of recommendations ... 63

4.2.8 Switching Barriers ... 64

4.2.8.1 Findings of the status-quo of switching barriers ... 64

4.2.8.2 Description and analysis of switching barriers... 65

4.3 Proposed guideline ... 67

5

Conclusion... 69

6

Discussion ... 70

6.1 Theoretical implications ... 70

6.2 Managerial implications ... 70

6.3 Limitation and further research ... 71

7

List of References... 73

Figures

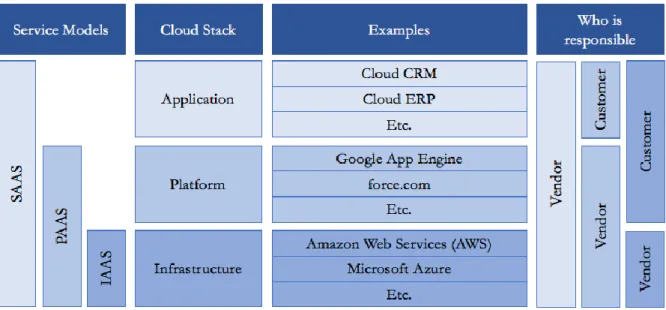

Figure 1 Adapted cloud stack ... 5

Figure 2 Classification of SaaS performance dimensions ... 11

Figure 3 Overview Switching Costs ... 16

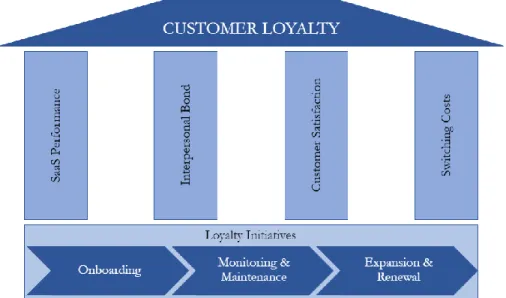

Figure 4 The loyalty construct ... 22

Figure 5 The research procedure ... 23

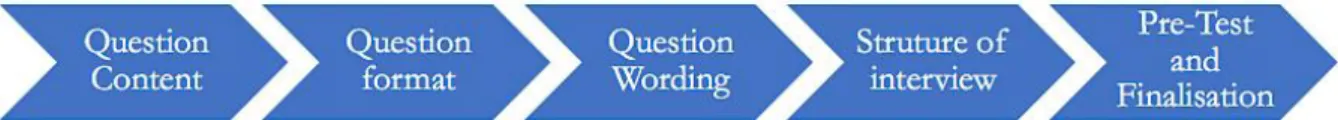

Figure 6 Procedure creation of interview guide ... 27

Figure 7 Data Structure ... 39

Figure 8 Summary of switching costs findings ... 66

Figure 9 SaaS client lifecycle ... 67

Tables

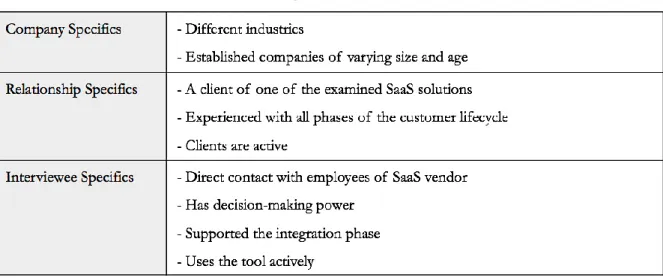

Table 1 Characteristics of sampling strategy for vendor interviews ... 28Table 2 Characteristics of sampling strategy for client interviews ... 29

Table 3 Overview Vendor Cases ... 31

Table 4 Overview Client Cases ... 31

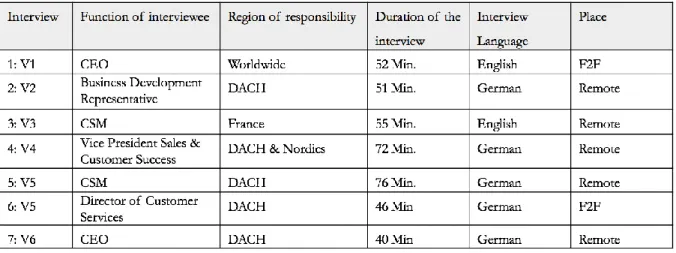

Table 5 Overview Vendor Interviews ... 32

Table 6 Overview Client Interviews ... 33

Table 7 Example of vendor interview coding ... 34

Table 8 Extract of client interview coding ... 35

Table 9 Classification of Project Phase... 43

Table 10 Classification of Training ... 46

Table 11 Classification of Monitoring and Maintenance ... 52

Table 12 Classification of Support and Complaint ... 56

Table 13 Classification of Feature Development ... 60

Table 14 Classification of Event and Workshop ... 62

Table 15 Classification of External Recommendation ... 64

List of Abbreviation

Abbreviation Full WordAPI Application programming interface

B2B Business-to-Business

B2C Business-to-Consumer

C1, C2, … Client 1, Client 2, …

CRM customer relationship management

CSM Customer Success Manager

EU European Union HR Human Resources IaaS Infrastructure-as-a-Service IT Internet technology p. page PaaS Platform-as-a-Service

SLA Service Level Agreements

SaaS Software-as-a-Service

USA United States of America

V1, V2, … Vendor 1, Vendor 2, …

1 Introduction

1.1 Background

Cloud computing is one of the key technologies of the 21st century (Goyal, 2014). It enables its users to access a shared pool of computing resources such as networks, servers, storage, application and services over the internet at any time and with any device, with minimal management effort or service provider interaction (Goyal, 2014; Mell & Grance, 2011). The global research and advisory firm Gartner (2019) revealed a study that the global public cloud services market will continue to grow about 33% between the years 2020 and 2022 to a total of $354 billion US-Dollars. Especially among enterprises, cloud computing has become tremendously popular in recent years, and almost all companies, independent of their size, started to adopt a cloud model into their business (Goyal, 2014). Gartner (2019) further found that a third of enterprises rank investments in cloud computing among their top three investment priorities. The COVID-19 crisis has further fuelled the demand for cloud computing as companies are forced to let their employees work from home. Cloud technology is an essential basis for home office, as it allows employees to access the same data and programmes from home and communicate over video conferences. Hence, cloud businesses could be one of the big winners of the crisis (Kiren, 2020).

Cloud computing can be divided into three different subsets; Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS), Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS) and Software-as-a-Service (SaaS). While IaaS and PaaS are forecasted to grow more rapidly in the next years, SaaS will not only remain the largest market segment but will grow even further (Gartner, 2019). As a study conducted by Forbes in 2018 among enterprise end-users showed, 12% of the companies surveyed already shifted to cloud solutions, while another 52% of respondents stated that they were undergoing the lift-and-shift to the cloud (Forbes, 2018). Consequently, traditional on-premises software models are slowly being replaced. One reason for this development is the easy scalability of SaaS. Besides, customers can benefit from lower IT costs, increased flexibility, as well as a simplified implementation. Additionally, it is easier for SaaS enterprise customers to switch between different SaaS vendors1 as the SaaS vendor market is highly competitive and SaaS customers are only bound by terminable contracts with no or low up-front investments (Armbrust et al., 2010; Benlian, Koufaris, & Hess, 2011; Goyal, 2014).

1 By definition, a vendor is “a company or person that sells goods or services” (Merriam-Webster, n.d.-d), while a

provider is “a group or company that provides a specified service” (Merriam-Webster, n.d.-c). In the following, both terms are used synonymously.

In order for vendors to prevent customers from switching, they need to use different initiatives to nurture the relationship with customers, which help them to retain their customer base loyal. One reason why a loyal customer base is crucial is that new customer acquisition alone will not ensure long-term success (Duffy, 2003) as, according to different studies, acquiring a new customer is between five and 25 times more expensive than retaining an existing one (Gallo, 2014). Another reason is that loyal customers are more likely to recommend the solution they are using and are less likely to react positively to the approach of competitors (Rauyruen & Miller, 2007; Reichheld, 1996). Further, as customer loyalty seems to have a more significant role to play in B2B than B2C because customers are often fewer in numbers in B2B, making them more valuable, and their loss even more undesirable (Sagar et al., 2013; Tamaddoni Jahromi, Stakhovych, & Ewing, 2014). For this reason, we have decided to focus on loyalty initiatives in B2B.

1.2 Problem

According to Zineldin (2006), increasing customer loyalty is a recurring debate at board level within many organisations. The concept of customer loyalty has been researched extensively in the past, and the available literature has mainly indicated that various antecedents have a direct or indirect influence on customer loyalty. For example, several articles see the interpersonal bond and the overall satisfaction between SaaS vendors and SaaS customers as well as the perceived service quality, customer value, and switching costs as influencing factors of customer loyalty (Lam, Shankar, Erramilli, & Murthy, 2004; Russo, Confente, Gligor, & Autry, 2016). These antecedents can be strengthened through different loyalty initiatives by businesses aiming for loyal customers (Duffy, 2003, 2005). However, researchers have found that currently, most companies only focus on satisfaction as an antecedent for loyalty but fail to cover the others (Narayandas, 2005; Nyadzayo & Khajehzadeh, 2016). According to Kumar, Pozza, and Ganesh (2013), this is not enough to fully explain loyalty, as all the other antecedents need to be taken into account to depict a complete picture.

Compared to on-premises solutions, the SaaS monetisation model is based on long-term relationships, which makes initiatives designed to retain clients even more critical during the whole customer lifecycle. With on-premises solutions, the vendor “typically earns 50 to 75 percent of the product’s lifetime customer revenues during the first year after the sale” (Pineda & Izaret, 2013, para. 14) because of high initial licensing costs. For SaaS, the percentage share of customer lifetime value is distributed more evenly over an extended period due to subscription payments plus an increasing added value which comes with usage growth, add-ons and cross-selling over time (Pineda & Izaret, 2013). Hence, they need to consider their clients within all their business

initiatives, such as software development, support delivery, user training. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, only a few articles are focusing on loyalty antecedents in the SaaS environment and only a minority provides actual management implications on how SaaS vendors should design their customer loyalty initiatives (Rauyruen & Miller, 2007).

1.3 Purpose

The purpose of this thesis is to investigate the current customer loyalty management initiatives of SaaS vendors to enrich existing theoretical literature with practical insights as well as deliver a guidelinefor SaaS vendors with recommendations how to design loyalty initiatives. This purpose translates into the following research questions: “How can loyalty initiatives be designed to improve the loyalty of SaaS business clients?”. As the wording of the research question implies, the study is about loyalty initiatives that aim to retain clients2. However, we aim to focus on actions rather than on key performance indicators such as the retention rate. To answer the main research question, two sub-questions will be used. Firstly, we want to examine and understand the vendor-side with its current initiatives by answering our first sub-question: “How do SaaS vendors manage the loyalty of their business clients currently?”. Secondly, the sub-question “How do SaaS business clients perceive the loyalty initiatives of SaaS vendors and what are they missing?” will allow us to take the perspective of the SaaS clients to clarify how they perceive the status-quo and how loyalty initiatives can be improved.

2 The words customers and clients are synonymously used within the literature. By definition a client is a person, “who

is served by or utilizing a service” (Merriam-Webster, n.d.-b), while a customer only “purchases a commodity or service” (Merriam-Webster, n.d.-a).

2 Literature review

2.1 Cloud computing and the Software-as-a-Service business model

As SaaS is the object of our investigation, the following chapter will give a brief introduction about cloud computing and highlight the advantages and disadvantages of SaaS.

2.1.1 Introduction to cloud computing

Even though there is already a significant amount of literature available, researchers have not agreed on a uniform definition for cloud computing yet. However, many authors refer to the NIST definition which states that cloud computing is “a model for enabling ubiquitous, convenient, on-demand

network access to a shared pool of configurable computing resources (e.g., networks, servers, storage, applications, and services) that can be rapidly provisioned and released with minimal management effort of service provider interaction.” (Mell & Grance, 2011, p. 2). Due to the strong growth of the cloud industry within the

last years, the market is highly competitive (Marston, Li, Bandyopadhyay, Zhang, & Ghalsasi, 2011). Consequently, cloud computing vendors are required to address the requirements and doubts of potential customers and guarantee support along the whole customer journey.

Cloud computing can be narrowed down to three service models: 1) Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS), 2) Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS), and 3) Software-as-a-Service (SaaS). However, authors like Armbrust et al. (2010) avoid distinguishing between IaaS and PaaS because of their view that they are more similar than they are different. Nevertheless, one of the oldest and enforced classifications, the SPI cloud classification, considers all three types (Youseff, Da Silva, Butrico, & Appavoo, 2010). The Cloud Stack (shown in simplified form in Figure 1) is a further development of the SPI classification, which offers a more structured view and examples and therefore provides the reader with a better understanding (Kavis, 2014).

As one can see in Figure 1, IaaS vendors provide infrastructure like servers and storage, firewalls, networks. Within PaaS, vendors offer a platform of software environments and application programming interfaces (APIs) that can be utilised mainly by developers in developing cloud applications (Youseff et al., 2010). Finally, SaaS is targeting the end-user with ready-to-use software applications. Here, the vendor is in charge of the underlying cloud infrastructure, application logic and deployments, while the customer can only configure some application-specific parameters and manage users. (Kavis, 2014) For example, SaaS customer can grant shared access to the application (multi-tenancy) to create economies of scale and lower costs. Looking at the interlink between these elements, IaaS is the foundation tone upon which the other two (PaaS and SaaS) are built

(Dempsey & Kelliher, 2018). Therefore, SaaS vendors are only in some cases, also the provider of the cloud storage infrastructure. This means that SaaS customers, who are concerned about the security of a SaaS vendor, will sometimes also have to check third parties that deliver the data storage (Armbrust et al., 2010; Goyal, 2014).

Figure 1 Adapted cloud stack3

Based on how cloud services are made available to users, deployment types can be broken into the following: 1) public, 2) private, 3) hybrid and 4) community cloud (Goyal, 2014). Since most SaaS solutions run on public clouds, and we only consider those in our research, we do not further discuss the differences but only define the public cloud. Public cloud means that the cloud infrastructure is provisioned for open use by the general public or a large industry group (Mell & Grance, 2011). One benefit of public clouds is that formidable up-front investments on the customer side, e.g. in hardware, are eliminated and that customers can scale their usage according to their demand (Armbrust et al., 2010; Hsu, Ray, & Li-Hsieh, 2014). Nevertheless, customers have to face downsides like less data security and a loss of control (Goyal, 2014).

2.1.2 The Software-as-a-Service business model

SaaS solutions can be delivered over web-based user interfaces, that are usually accessible on any device that can connect to the internet. Another option is API where customers can integrate features into their existing applications or connect them with other SaaS solutions (Weinhardt,

3 Adapted from „Architecting the cloud: design decisions for cloud computing service models (SaaS, PaaS, and IaaS)”

Anandasivam, Blau, & Stosser, 2009). Either way, SaaS clients benefit from the advantages that public cloud computing brings (Armbrust et al., 2010; Hsu et al., 2014).

Furthermore, SaaS does not require a company’s IT team to build and manage everything, such as installing and managing servers, developing and installing the software as well as ensuring its security. Thus, SaaS allows customers to cut costs, for example, maintenance and employee costs (Goyal, 2014). This makes it easier for customers to switch between different SaaS vendors as they are not bound to a particular vendor due to no or low up-front investments and terminable contracts, with pricing models like “pay-as-you-go” or subscription models. However, it must be critically noted that switching a SaaS vendor is not generally seen as a benefit by SaaS customers due to change management related issues (Seethamraju, 2014).

Another essential benefit of SaaS is that vendors usually provide systematic support, and the systems are updated and continuously maintained. As a result, all customers are benefitting from the latest technological changes. In comparison, traditional on-premises software is maintained mostly once a year, so they provide less room for innovation (Goyal, 2014). On the contrary, this leads to high staff costs at the vendor-side as the pressure for continuous software updates, the requirement for customer service and the constant education and training of new features is high. Additionally, vendors have to offer training courses to increase user acceptance and guarantee continuous interaction. Here, however, difficulties arise from the fact that there is often no personal contact between vendor and customer. Therefore, vendors need to get in touch with the right contact person to keep customers engaged. Moreover, vendors are continuously struggling with the requirements of customers to have customised solutions which allow for interoperability with other solutions (Hentschel, Leyh, & Petznick, 2018). As the literature shows, SaaS vendors have to consider a lot to satisfy their customers’ needs and keep them loyal.

2.2 From a goods- to a service-dominant management strategy

Until the 1980s, most companies have placed their products at the centre of their operations (Vargo & Lusch, 2004). Within this so-called goods-dominant (G-D) logic companies embedded value into mostly tangible units of output (products) and offered those to customers. The customer only played a passive role in this process, as the aim was to produce standardised and inventoriable goods in isolation from the customer to increase efficiency (Vargo & Lusch, 2008). With the emerging interest in services and the growing variance of customer needs, the service-dominant (S-D) logic came into play which focuses on the process of serving rather than the product itself (Barqawi, Syed, & Mathiassen, 2016; Lusch & Nambisan, 2015). According to Vargo and Lusch

(2004, p. 2), the S-D logic implies “the application of specialized competences (knowledge and skills) through

deeds, processes, and performances for the benefit of another entity or the entity itself.” This means that value

creation becomes a collaborative process of co-creation between the service provider and the customer, where the customer becomes part of the service providers network and resources. Goods can thereby still play an important role as conveyors of competences, but it is the service that creates the actual value (Vargo & Lusch, 2004, 2008). Grönroos and Svensson (2008) therefore introduced the concept of value-in-use, as the value arises only in the service process. This also implies that value is not a fixed unit of measure that can be added in the manufacturing process. Hence, value also depends on the customer’s individual perception, which is inherently linked to the specific needs, requirements and the situation it occurs (Vargo & Lusch, 2004).

Applying the S-D strategy is especially crucial to the IT industry as computer software and hardware are only valuable to the extent to which they contribute to the value propositioning and value co-creation. Hence, the attention of IT providers should shift from the sole offering of hardware or software towards the delivery of expected services (Barqawi et al., 2016; Brocke et al., 2009; Lusch & Nambisan, 2015). Especially the SaaS environment has to deal with a high failure rate and many vendors have to deal with low performance, caused by service issues such as the inability to provide personalised service or implement IT solution (Chou, Chang, & Hsieh, 2014). With recurrent release management cycles, SaaS vendors try to overcome these issues and thereby try to adjust their value proposition continuously to their clients’ needs. Hence, the S-D logic is a highly suitable analytical framework for studying the delivery of SaaS applications (Barqawi et al., 2016; Lusch & Nambisan, 2015).

Further, some literature argues, that the S-D logic idolises customer-centricity, yet does not entirely focus on client needs but still remains provider-centric (Brown, 2007; Heinonen et al., 2010). Hence, the authors Heinonen et al. (2010) introduced the so-called customer-dominant logic of service, which centres around the customer rather than the service. It will allow companies to build business activities that are based on in-depth customer insights about their practices, experiences, and context. The insights are used to adjust the service offerings according to the customers’ needs. Building this relationship of collaboration and interaction is key for a successful SaaS vendor (Chou et al., 2014). To retrieve this deep customer insights, companies started to use customer relationship management (CRM) systems to identify, attract, differentiate, and retain customers. The main focus of CRM is to nurture long-lasting business-relationships by concentrating entirely on the customers’ needs (Gee, Coates, & Nicholson, 2008). The concept around retaining

customers to build long-lasting business relationships is of high importance and will be further discussed in the upcoming customer loyalty section.

2.3 The concept of customer loyalty

2.3.1 The definition of customer loyalty

The evolution of the loyalty concept has a long history and has been intensely discussed throughout the years by many different authors. Most of the latest articles, however, link back to the historical findings of customer loyalty and its influential factors from researchers like Oliver, Zeithaml, Berry and Parasuraman (Haghkhah, Rasoolimanesh, & Asgari, 2020; Huang, Lee, & Chen, 2019; Russo et al., 2016).

In the beginning, researchers strongly focused on the behavioural outcomes of loyalty towards mostly tangible goods (Caruana, 2002). This so-called behavioural loyalty is mainly demonstrated by repeated or increased frequency of purchases of specific products (Rauyruen & Miller, 2007; White & Yanamandram, 2007). But authors soon realised that loyalty consists of more than just behavioural components and that the attitude towards a brand also plays an essential role (Caruana, 2002). Therefore, attitudinal loyalty got introduced, which is about a customer’s psychological attachments and positive feelings towards a brand/provider. It is expressed in the form of providing positive word-of-mouth as well as recommending and encouraging others to use the specific product or service (Rauyruen & Miller, 2007; White & Yanamandram, 2007; Zeithaml, Berry, & Parasuraman, 1996). Consequently, several authors tried to incorporate both, the behavioural and attitudinal component in their definitions. It must be critically noted that some authors argue that behavioural and attitudinal loyalty cannot be considered on the same level. This is because attitude may even be a consequence of behaviour and the fact that both attitude and behaviour may change over time (Rowley & Dawes, 2000).

Later, a few scholars introduced a third dimension to the definition of loyalty and labelled it cognition. According to this dimension, a customer is considered as loyal when he or she does not actively seek out or consider other firms (Gremler & Brown, 1996). By combining the third dimension with the first two, researchers have introduced a concept of loyalty, including behaviour, attitude, and cognition. One of the most cited definitions is the one by Oliver (1999, p. 34), which describes loyalty as

“a deeply held commitment to rebuy or repatronize a preferred product/service consistently in the future, thereby causing repetitive same-brand or same brand-set purchasing, despite

situational influences and marketing efforts having the potential to cause switching behavior.” (Oliver, 1999, p. 34)

With time, the importance of the services, which are intangible goods offered by people, enterprises and technologies, grew. Hence, scholars started to consider services within their definitions (Hill, 1999). Thereby, Gremler and Brown (1996, p. 173) came up with the following definition:

“Service loyalty is the degree to which a customer exhibits repeat purchasing behavior from a service provider, possesses a positive attitudinal disposition toward the provider, and considers using only this provider when a need for this service arises.” (Gremler & Brown, 1996, p. 173)

Moreover, some researchers realised that the available definitions for customer loyalty only covered the business model of recurring, one-time purchases, which is often associated with tangible goods. Therefore, Zeithaml et al. (1996) extended the definition above by saying that customer loyalty is a consumer’s intent to not only make repeated purchases but also stay in an existing business relationship.

Further, approximately until the year 2000, researchers partly differentiated between loyalty in the business-to-consumer (B2C) and business-to-business (B2B) contexts. However, researchers started to acknowledge differences between the two, for example, that B2B customers are more likely to engage in cooperative actions which is beneficial as it can lead to lower transaction costs and increase the competitive advantage. Hence, a close relationship between the vendor and customer is even more critical in the B2B context (Lam et al., 2004).

To the best of our knowledge, no definition consolidates all three loyalty characteristics in the service context by considering the unique characteristics of B2B SaaS. Therefore, we propose customer loyalty as a composite concept combining different aspects of the above’s definitions:

Customer loyalty in the SaaS context can be defined as a business customer’s intent to maintain in a long-term relationship with its SaaS provider (behavioural) despite competitive approaches (cognitive), and a willingness to recommend and encourage others to use the software (attitudinal).

It must be noted that customers might not show all aspects of the above’s definition, which is why some authors try to avoid using loyalty definitions like the one above (White & Yanamandram, 2007). Nevertheless, our research will further build on all three loyalty characteristics.

2.3.2 Antecedents of customer loyalty

To understand the sources of customer loyalty, researchers introduced various models that investigate its influential factors. These so-called antecedents range from interpersonal aspects to more professional service-oriented characteristics. In subsequent sub-sections, we present the most relevant antecedents, which we grouped into the following categories: 1) SaaS performance, 2) interpersonal bond, 3) satisfaction, and 4) switching costs. It is worth noting that scholars like Fredericks and Salter II (1995) also introduced external forces influencing customer loyalty, such as customer characteristics or external market factors. As they can be hardly controlled by management, they will not be considered here. Instead, we only define the antecedents mentioned above. However, as they are often overlapping, a clear distinction is impossible. To reduce confusion, where there are multiple terms with almost identical definitions to describe an antecedent, we use a uniform term, e.g. interpersonal bond instead of relationship quality and relationship benefits. The definitions are then followed by a discussion of their influence on loyalty. As there is limited literature about customer loyalty in SaaS, we mainly focused on articles considering antecedents in the B2B context.

2.3.2.1 SaaS performance

Early scholarly writings suggest that service quality stems from a comparison between what clients feel the SaaS firm should offer (i.e. expectations) and their perception of the actual service performance (Benlian et al., 2011; Parasuraman, Zeithaml, & Berry, 1985). Perceived service quality is therefore defined as the “degree and direction of discrepancy between consumer’s perception and

expectations” (Parasuraman, Zeithaml, & Berry, 1988, p. 4).

Using insights from these studies as a basis, Parasuraman et al. (1988) developed and refined SERVQUAL, a multiple-item instrument to quantify customers’ global assessment of a company’s service quality, which has since been quoted by various sources (e.g. Benlian et al. (2011); Huang et al. (2019); Jayawardhena, Souchon, Farrell, and Glanville (2007); Wilson, Zeithaml, Bitner, and Gremler (2016)). The original SERVQUAL instrument identified five service quality dimensions: Tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance and empathy (Figure 2 – left). Tangibles deal with the physical environment and appearance of the service provider, while reliability and responsiveness describe the provider’s ability to react in time and quickly provide the promised service. Assurance describes the customer’s confidence in the service provider’s courtesy, knowledge and ability. Finally, empathy is about a service provider’s ability to understand

problems, provide individualised attention, and act in the clients’ best interest (Benlian et al., 2011; Parasuraman et al., 1988; Wilson et al., 2016).

As SERVQUAL is mainly focused on service quality in the offline/physical world, Benlian et al. (2011) introduced the SaaS-Qual (Figure 2 – second from left), a measure for service quality in the SaaS context. While the authors kept the dimensions of responsiveness and reliability from the aforementioned SERVQUAL, the dimensions of assurance and empathy were merged into one factor that they called rapport. Additionally, the tangibles dimension was renamed to features. They then added the dimensions of flexibility and security. Flexibility describes the freedom to make contractual or functional changes, while security includes all actions to avoid data breaches or corruptions (Benlian et al., 2011). Other studies brought in additional factors such as the importance of professionalism, competence, communication, and information (Janita & Miranda, 2013; Jayawardhena et al., 2007).

Figure 2 Classification of SaaS performance dimensions

To simplify the definition of service quality, we found it more reasonable to group these dimensions into two clusters, as outlined by the approach used by Zineldin (2006). They suggest classifying dimensions either as ‘quality of process’ or ‘quality of object’ (Figure 2 – right). ‘Quality of process’ refers to the way the vendor delivers the software, while ‘quality of object’ is about the

perceived quality of the software itself. According to this, responsiveness, reliability, rapport, professionalism, competence, communication and information could be assigned to ‘quality of process’. Flexibility, features and security, on the other hand, can be preferably used to specify the performance of the actual software (quality of object).

One can say that Zeithaml (1988) equates ‘quality of object’ with customer value, which stands for the customer’s overall assessment of a product/service’s utility based on the perception of what is received and what is given. Similar to service quality, customer value is a perception of the customer. It depends on personal characteristics such as prior product knowledge and financial resources as well as on circumstances such as time frame and the location of consumption (Nyadzayo & Khajehzadeh, 2016).

Different sources highlight that a positively-perceived SaaS performance has a direct influence on customer loyalty (Ramaseshan, Rabbanee, & Tan Hsin Hui, 2013; Rauyruen & Miller, 2007; Yang & Peterson, 2004). The authors Ramaseshan et al. (2013) even state that service quality is one of the most essential antecedents next to the interpersonal bond. Moreover, according to Benlian et al. (2011), responsiveness and security are most important for a positively-perceived service. Finally, Nyadzayo and Khajehzadeh (2016) state that confidence in the quality and reliability of services also increases the customer's trust.

To sum up, the literature suggests that the identified dimensions have a direct, positive influence on customer loyalty. To make it clearer, we created and introduced the antecedent SaaS performance as a further development of the SaaS-Qual. Additionally, we enriched it with the dimensions professionalism, competence, communication, and information, while leaving out the interpersonal dimensions, namely rapport. Hence, the SaaS performance consists of both the ‘quality of object’ as well as ‘quality of process’.

2.3.2.2 Interpersonal bond

Generally, a business relationship describes the kind of link a company establishes between itself and its clients (Dempsey & Kelliher, 2018). Further articles define it as the degree to which personal relationships exist between employees of different organisations (White & Yanamandram, 2007). As our loyalty definition consists of three dimensions which go beyond the mere purchase of software, we follow the definition of Čater and Čater (2010, p. 1323) who describe it as “bind[ing] members to each other in such a way that they are able to reap benefits beyond the mere

exchange of goods”. This interpersonal bond occurs through various dimensions including familiarity,

care, friendship, civility, friendliness, rapport, and trust (Crosby, Evans, & Cowles, 1990; Gremler & Gwinner, 2000; Jayawardhena et al., 2007). Since most of these scholars focus on rapport and trust, we are only going to explore these two dimensions in more detail.

Benlian et al. (2011) state that rapport includes all aspects of a SaaS provider’s ability to provide knowledgeable, caring, and courteous support and individualised attention. Since we aimed to filter out the emotional elements from the combination of emotional and professional elements in the definitions above, we would rather use the following definition of Gremler and Gwinner (2000, p. 92) which states that rapport is “a customer’s perception of having an enjoyable interaction with the service

provider’s employee, characterised by a personal connection between the two interactants.”. Further, Moorman,

Deshpande, and Zaltman (1993, p. 82) define trust as “a willingness to rely on an exchange partner in

whom one has confidence”. Finally, some authors argue that satisfaction and commitment are aspects

of the interpersonal relationship. Since our research looks at overall satisfaction, we will consider it independently in the next section. Moreover, we would rather classify commitment as an aspect of loyalty rather than an antecedent (Liu, Guo, & Lee, 2011).

Various researchers that examined the influence of an interpersonal relationship on customer loyalty found that a good interpersonal bond enhances customer loyalty. Ramaseshan et al. (2013), for example, state that the interpersonal relationship is as important as the service quality, while Čater and Čater (2010) even see the emotional bond as mainly important. The authors argue that customer loyalty depends more on emotional than on rational motivation in the form of software or service quality. Hence, they suggest that managers should do everything in their power to increase the perceived trustworthiness in the eyes of their clients. An article by Ramaseshan et al. (2013) states that the relationship has a significant influence on loyalty and that trust mediates this relationship completely. According to Rauyruen and Miller (2007), trust in the supplier increases attitudinal loyalty but does not influence behavioural loyalty. Moreover, the authors found trust in a supplier’s employees does not affect attitudinal loyalty, while trust in the supplier itself as a whole has a positive effect. However, trust in the supplier’s employees does not have a significant influence. In comparison, Colgate et al. (2007) argue that recruited, trained, well-supported employees are perceived as more friendly and caring by customers, which increases the social bond between customers and service provider. The influence of rapport on behavioural and attitudinal loyalty is supported by the study of Gremler and Gwinner (2000), who also states that rapport influences satisfaction.

Concluding, we identified the interpersonal bond between vendor and client as the second antecedent of B2B customer loyalty in SaaS.

2.3.2.3 Customer satisfaction

Satisfaction has been defined in many different ways. A broad definition is provided by Oliver (1999, p. 34) which states that “satisfaction is defined as a pleasurable fulfilment”, which means that the consumption of a product or service fulfils a need or expectation and that it is perceived as exceeding the standard (Nyadzayo & Khajehzadeh, 2016). Scholars like Kandampully (1998) argue that exceeding the standard should be called customer delight instead of satisfaction. While customer satisfaction is generally based on meeting expectations, customer delight means that the customer receives a positive surprise that goes beyond their expectations. Therefore, delight can be viewed as an emotional response that commits a customer to the product (Berman, 2005).

It should be noted that the use of the term ‘expectations’ used in the context of satisfaction differs from its usage in the context of service quality (i.e. SaaS performance). In the literature around service quality, expectations are regarded as desires or wants of consumers, i.e. what they feel a service provider should offer rather than would offer. In contrast, in the literature around satisfaction, expectations are viewed as predictions made by customers about what is likely to happen during a transaction or exchange (Parasuraman et al., 1988). Here, satisfaction is known as transaction-based or service-encounter and only focuses on one special occasion, such as the moment of transaction or receiving a service. Further research, therefore, introduced cumulative (overall) satisfaction. Geyskens, Steenkamp, and Kumar (1999, p. 224) provide a definition for cumulative satisfaction which states that customer satisfaction in the B2B context is “a positive

affective state resulting from the appraisal of all aspects of a firm's working relationship with another firm.”

Cumulative satisfaction has been generally seen to be a more fundamental indicator for a firm’s overall performance.

Some researchers also differentiate between cognitive and affective satisfaction. While cognitive satisfaction is based on firm performances (Danaher & Haddrell, 1996), affective satisfaction describes the emotional attachment of customers with its vendor, which we consider within the interpersonal bond.

The concept of customer satisfaction is one of the most controversial discussed antecedents of loyalty, and the literature provides mixed results when analysing their relationship. Many authors

agree that satisfaction has some sort of influence on customer loyalty. However, most of them proposed different types of relationships. Firstly, some articles discussed the direct influence of satisfaction on customer loyalty without an interplay of other antecedents. An early article from Bloemer and Kasper (1995) found that latent satisfaction has a lower direct impact on customer loyalty than manifested satisfaction. The difference between both satisfaction types is that manifested satisfaction results from a well-elaborated evaluation, while latent satisfaction only takes an implicit, non-elaborated evaluation.

The direct interlink was further supported by Gremler and Brown (1996), who argued that customer loyalty could only occur after some level of satisfaction. However, this is not a linear relationship, according to Dagger and David (2012), as it oversimplifies the complex relationship between these two constructs. That is why they proposed that satisfaction has a mediating or moderating role. For example, different articles discovered that satisfaction mediates the relationship between customer value and customer loyalty (Blocker, Flint, Myers, & Slater, 2010; Lam et al., 2004; Spreng & Mackoy, 1996). Further, some authors also found that satisfaction also acts as a mediator between service quality and customer loyalty (Parasuraman et al., 1985; Yang & Peterson, 2004). Contrarily, Kumar et al. (2013) proposed a relationship between satisfaction and loyalty but expressed that other relevant variables are needed as moderators, mediators or antecedent variables. The reason is that customer satisfaction has only a weak influence on customer loyalty and can, therefore, hardly change it in a significant way (Kumar et al., 2013).

Nyadzayo and Khajehzadeh (2016) found that the customer satisfaction-loyalty relationship is strengthened through highly-perceived customer trust and commitment. Additionally, the satisfaction–loyalty relationship might change in the course of the customer lifecycle. This is because the customer's purchase intentions today might not be the same tomorrow, because of the influence of the moderators in the intervening period. Additionally, it could also happen that the customer gets attracted by a competitor’s product or that their memory about the positive experience blurs over time (Mazurski & Geva, 1989).

Finally, different authors reject the opinion that satisfaction influences loyalty at all. Janita and Miranda (2013), for example, found that satisfaction neither has an influence on customer loyalty nor plays a mediating role. The research of Colgate, Tong, Lee, and Farley (2007) further revealed that customers often stay with a service provider, even when they are unsatisfied until they experience a truly negative incident.

As shown, the available literature about the satisfaction-loyalty relationship varies a lot. For our thesis, we assume that there is some relationship between satisfaction and loyalty, which is why we introduce customer satisfaction as the third dimension of customer loyalty.

2.3.2.4 Switching costs

Finally, switching costs are often discussed antecedents of customer loyalty. At its broadest level, switching costs can be defined as the “perceived economic and psychological costs associated with changing

from one alternative to another.” (Jones, Mothersbaugh, & Beatty, 2002, p. 441). As such, it affects

loyalty, as high switching costs can be seen as barriers that keep customers in relationships (Jones et al., 2002; Sagar et al., 2013). Examples of switching costs are habit/inertia, setup costs, search costs, learning costs, contractual costs, and continuity costs (Gremler & Brown, 1996).

One way to cluster different forms of switching costs is classifying them into internal and external switching costs (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Overview Switching Costs

Internal switching costs are primarily rooted in an individual customer who may lack in expertise, skills, or ability to gather necessary information and evaluate service providers (preswitching costs), risk of lower performance when switching (uncertainty costs), to learn the procedures and routines of a new vendor (postswitching and behavioural costs) and costs associated with the establishment of a new relationship (setup costs) (Blut, Beatty, Evanschitzky, & Brock, 2014; Jones et al., 2002). External switching costs capture costs stemming from specific benefits and privileges that could be lost when switching from a current provider (costs of lost performance), and from previous investments and costs already incurred in establishing and maintaining a relationship (sunk costs) (Blut et al., 2014; Jones et al., 2002). Further, Burnham, Frels, and Mahajan (2003) argue that the provider’s relationship-building efforts result in relational switching costs. Consequently, when a customer must break a bond with a provider brand (brand relationship costs) or with a customer-contact employee (personal relationship loss costs), it can lead to emotional and psychological

discomfort. Finally, it must be noted that compared to B2C, the complexity and costs of switching B2B software solutions are much higher, but as we have said before, it is far more doable and likely than with on-premises solutions (Mehta, Steinmann, & Murthy, 2016).

Several articles see a direct, positive relationship between switching costs and customer loyalty. While Jones et al. (2002) concluded that all switching costs dimensions that have been introduced so far relate positively with repurchase intentions, Lam et al. (2004) revealed that switching costs influence not only behavioural loyalty but also influence attitudinal loyalty. Further, Blut et al. (2014) found that while both, internal and external switching costs, influence customer loyalty directly, external switching costs have a stronger effect on customer loyalty. One explanation for that is that external switching costs are viewed as more certain as the customer faces an actual loss of additional benefits when switching. A more specific explanation in this context might be findings of Colgate et al. (2007), who argue that the longer a business relationship, the higher the switching barriers are becoming. Internal switching costs, on the other hand, are less certain because the individual does not know how much effort will be required to search for an adequate new vendor, or how much learning effort will be necessary with a new service vendor (Blut et al., 2014).

Further, several authors propose that switching costs take a moderating role between satisfaction and customer loyalty. This occurs when the switching costs are so high that customers do not switch vendors even when they are dissatisfied with a product (Heide & Weiss, 1995). Further, Dagger and David (2012) argue that besides the fact that switching costs can intensify the satisfaction-loyalty relationship, they can also weaken it. They found that satisfaction has a reduced effect on customer loyalty as both the interpersonal bond and switching costs (monetary and emotional) increase. This may be because high benefits serve to further “lock” the customer into the relationship. Benefits serve to increase the customers perceived switching costs, which in turn, reduce the effect of satisfaction on loyalty (Dagger & David, 2012). Additionally, the study of Yang and Peterson (2004) found that switching costs only have a moderating role if satisfaction and service quality are above average. Their explanation, therefore, is that the higher the customers’ perceived switching cost seem to be, the higher their satisfaction or perceived service quality is. If this situation is not given, Yang and Peterson (2004) do not support the mediating role of switching costs, which they explain with the conflicting role of switching costs and satisfaction or service quality. While switching costs are perceived as negative by the customer, satisfaction and service quality are positive contributors to customer loyalty. In line with this finding, Wang (2010) tested

if switching costs would also moderate the relationships between service quality and loyalty. However, his results showed that switching costs could not overcome the urge to look for another vendor if service quality reduces.

Finally, as the literature proposes a positive link between switching costs and customer loyalty, this is our fourth and last dimension of the antecedents’ construct.

2.3.3 Initiatives that contribute to customer loyalty

Since there are countless terms and forms used in connection with customer loyalty initiatives, this chapter presents the delimitations and the definition employed for this thesis.

2.3.3.1 The concept of loyalty initiatives and its delimitations

Generally, initiatives which aim for customer loyalty-building seek stronger and more long-lasting relationships with customers, thereby increasing overall sales and profits (Duffy, 2003, 2005). Authors like Lacey and Morgan (2008) and Berman (2006) present so-called loyalty programmes which are targeted marketing activities, such as discounts, free goods, offers and mailings. While these programmes take place at a very operational level, different authors argue for a more strategic approach (Duffy, 2003), where all of a company’s units and departments are designed around customer loyalty (Reichheld, 1996). To reach this mindset, the commitment of senior management, as well as a customer-focused company culture which transcends through all departments, is essential (Day, 2003). To implement a real customer-centric company culture, authors like Yohn (2018) and Jones and Sasser (1995) state that companies must train their employees accordingly and pay incentives for employees who achieve high client retention. Jones and Sasser (1995) state that companies must train their employees accordingly and pay incentives for employees who achieve high retention. Our study, however, will only focus on initiatives that are directly targeted towards the clients and/or performed in collaboration with them.

Moreover, authors like Kumar and Shah (2004, p. 322) argue that “building loyalty without focusing on

profitability may tantamount to failure over time.”, because stable and healthy growth is built on customer

profitability, rather than customer loyalty (Reinartz & Kumar, 2002). Consequently, they propose to treat customers differently based on their status (Kumar et al., 2013; Reinartz & Kumar, 2002; Rowley & Dawes, 2000). In contrast, authors like Wood (2005) criticise this customer segmentation, as even low-value customers produce revenue. Hence, firms cannot afford to reject

any customer (Wood, 2005). Based on our rationale that B2B customers are generally more valuable, we will be following the statement of Wood (2005) and argue that all customers should receive the same attention.

2.3.3.2 Defining loyalty initiatives in SaaS

In this chapter, we provide examples of loyalty initiatives to conclude with a final definition. To present these examples in a structured way, while maintaining the customer-centric view presented above, we make use of the customer service lifecycle introduced by Ives and Mason (1990), consisting of four phases: 1) requirements, 2) acquisition, 3) ownership and 4) retirement. By definition, loyalty initiatives can only be targeted towards active clients. Consequently, we only focus on the ownership phase with its sub-items training, monitoring and maintaining, and upgrading. Following Vaidyanathan and Rabago (2020)’s statement that the first sub-item includes not only training but also other initiatives to set-up and activate users, we denote this phase as ‘onboarding’. Moreover, the upgrading is usually accompanied by the client’s decision to continue or expand their relationship with the vendor. Hence this phase is called ‘renewal and expansion’ (Vaidyanathan & Rabago, 2020).

Within the onboarding process, clients learn how to use the SaaS solution effectively and realise its value, which is why an excellent first impression is essential. Hence, an initiative during this phase is that vendors devote a lot of time and effort for the training to increase the clients’ overall understanding about the software (Chou et al., 2014; Vinje, 2017; Whiting, 2019). Further, Macintosh (2009) states that clients who feel supported and understood in their needs will develop trust and rapport towards the vendor. Hence, it also enhances the interpersonal bond between vendor and client.

The second phase of the lifecycle begins when clients start to use the software regularly (Vinje, 2017; Whiting, 2019). At this phase, SaaS vendors must ensure the availability and performance of their software at all time, as clients are looking for the assurance of a consistent and superior SaaS performance (Benlian et al., 2011; Kandampully, 1998). Yang and Peterson (2004) state that vendors have to guarantee a precise execution of transactions, errorless maintenance of customer records, and fast delivery. Knowledge sharing and process coordination can help to achieve this perceived superior SaaS performance and to strengthen the interpersonal bond (Chou et al., 2014). Vendors should, therefore, interact with their customers directly to actively seek additional opportunities for knowledge-sharing. According to Peppers and Rogers (2017), it does not matter

if the contact builds up over telephone, videoconferences or face-to-face, as either way companies can nurture and establish a genuine, long-lasting relationship. Ramaseshan et al. (2013) found that effective and timely communication with trained personnel will increase the customer’s trust and lead directly to customer loyalty. Further, a positively-perceived ‘quality of process’ influences the overall satisfaction of the client (Anderson & Sullivan, 1993). Thereby, one can differentiate between reactive customer communication, where the client reaches out to the vendor, and proactive customer service, where the vendor establishes the contact to the client. The proactive strategy is often practised by customer success managers (CSM), who are trained to reach out and anticipate clients’ needs (Dempsey & Kelliher, 2018). The reactive strategy, in comparison, is often practised by a support team, for which the responsiveness (e.g., 24-7 hotline support) is mainly crucial (Benlian et al., 2011). Even though Vaidyanathan and Rabago (2020) suggest basing the decision for a proactive/reactive strategy on the customer’s percentage of the vendor’s revenue, various other authors would not do so. This is because they see the ability to listen and react to customers’ comments, complaints, and questions at the heart of appropriate satisfaction management (Gee et al., 2008; Jones & Sasser, 1995; Yang & Peterson, 2004). Zineldin (2006) argues that companies should even welcome complaints as they provide a second chance to recover dissatisfied customers and prevent churn. Soliciting customer feedback can help managers to have better knowledge about the possible negative, critical incidents beforehand to be able to avoid them or implement effective recovery policies (Benlian et al., 2011; Colgate et al., 2007; Jones & Sasser, 1995). A possible solution is interaction tools to solicit customer feedback and track retention rates to enhance the understanding of customer’ needs and their development over time (Barqawi et al., 2016; Zineldin, 2006). According to Chou et al. (2014), joint problem-solving and aligned working styles and processes on both sides can help to manage critical situations. However, Benlian et al. (2011) state that providing knowledgeable, caring, and courteous support through joint problem-solving or aligned working styles is not enough, but that individualised attention in the form of support tailored to individual needs is also crucial (Benlian et al., 2011). Solving critical incidents for the benefit of customers might even help companies to enhance their client’s satisfaction beyond the initial state before the incident (Colgate et al., 2007). Finally, Benlian et al. (2011) highlight the importance of ensuring security. Security includes all aspects to ensure that regular (preventive) measures (e.g. security audits, antivirus technology) are taken to avoid unintentional data breaches or corruptions, e.g., through loss, theft, or intrusions.

The upgrading and renewal phase in the customer lifecycle aims to enhance the willingness to stay with the vendor and expand the subscription package with additional features (Vinje, 2017;

Whiting, 2019). Within this phase, vendors must know how to address the customers’ expressed and latent needs by applying not only a responsive but also a proactive customer orientation to increase the customers’ value perception (Blocker et al., 2010). A proactive customer orientation will allow the vendor to show their clients that they are highly valued and increase their feeling of being honoured (Colgate et al., 2007). Knowledge sharing and process coordination will allow SaaS vendors to co-create their services together with their clients and to find out where there is room for improvement and innovation (Chou et al., 2014). Moreover, it helps the SaaS vendor to understand within which area they should allocate investments to improve their SaaS performance and to increase continued SaaS usage (Benlian et al., 2011). Generally, constant service innovation - which describes the approach of transforming a company’s assets including technology, service processes, environment and staff - leads to greater value for the customers and the organisation itself (Kandampully, 1998). By transforming and innovating its service constantly, SaaS vendors can also increase the complexity and hassle for customers to switch to another vendor, as existing and upcoming features become more difficult to compare (Chou et al., 2014; Colgate et al., 2007). By allowing the client to choose from a list of features, vendors can also provide their customers with some option of customisation by using a charge-per-feature approach (Dempsey & Kelliher, 2018). Additionally, Benlian et al. (2011) argue for freedom in terms of contractual contents such as cancellation period and payment model. Providing customers with rewards for repeat purchases (e.g. a discount on renewal) is another more superficial option to increase switching barriers. While this strategy is common in B2C, research confirms that this also increases switching barriers and builds barriers for market entry in B2B (Dempsey & Kelliher, 2018). Nevertheless, companies should seek to have committed customers, instead of customers that feel locked in (Zineldin, 2006). Additionally, according to Dagger and David (2012), managers should consider how benefits and switching costs are perceived by customers, as too many benefits lead to greater switching costs which in turn reduce the effect of satisfaction on loyalty.

The presented examples above show that loyalty initiatives can be executed in many different ways and leave room for numerous different actions, however, they all affect the antecedents previously presented. Considering the aforementioned delimitations, we present our definition for a loyalty initiative:

“Loyalty initiatives take place during the whole customer lifecycle and consist of a set of actions targeted towards clients to meet the antecedents of customer loyalty.”

2.3.4 The model of the customer loyalty construct

As a summary of our literature review about the concept of customer loyalty, we propose the following customer loyalty construct (Figure 4). The model visualises how the individual chapters are related. In the illustrated house, the loyalty initiatives serve as the foundation on which the antecedent pillars are built, which in turn are the dimensions of customer loyalty.

3 Methodology

The contents of this chapter will present, justify and discuss our methodological approach and the applied methods, illustrated in Figure 5, which will allow us to answer our research question. Further, the research quality and ethical principles will be discussed.

Figure 5 The research procedure4

3.1 Research philosophy

The first step was about gathering a deep understanding of the underlying research philosophy, namely ontology and epistemology. The ontology of research asks the question about the nature of reality, so it shows ‘what’ we can know about a research field. The epistemology then establishes on the ontology by answering the question of ‘why’ we have some specific knowledge about a topic. It thereby provides ways of enquiring into the physical and social world (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe, Jackson, & Jaspersen, 2018). As the aim of our research was to answer the question of “How can loyalty initiatives be designed to improve the loyalty of SaaS business clients?”, the research has to consider different loyalty initiatives, hence several different truths, which leads to

4Adapted from “Management & business research (6 ed.)” by M. Easterby-Smith, R. Thorpe, & P. R. Jackson, 2018, p. 65, Copyright by London: Sage.

a relativistic ontology. Our study belongs to the field of social science; hence our ontological viewpoint delimits itself from realism since realism would consider the physical and social world as independent. Moreover, it also delimits itself from nominalism as our research assumes that there is a truth which is dependent on the observer’s viewpoint. Further, our study tries to increase the existing knowledge about the complex social construct of loyalty management, which is why we classified our research as social constructionism. This epistemological approach is also supported as the human interest is the main driver for answering our research question. Additionally, social constructionism allows us to accept several, specifically chosen data sources and to interpret as well as generalise our findings (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018).

3.2 Research approach

We applied an abductive research approach to our study, as it allows us to combine real-world empirical findings with the theory found in available literature (Dubois & Gadde, 2002). Abductive research uses a wide range of existing theoretical findings and compares them with the collected data to support existing knowledge and introduce novel insights (Timmermans & Tavory, 2012).

Within our research, we first explored how loyalty initiatives are currently used (status-quo) and afterwards questioned how they are perceived and tried to compare our findings with the collected insights from theory. Thereby, we aimed to generate new insights to invent further theory that can be tested in future research. This approach supports the statement of Dubois and Gadde (2002), which says that an abductive research approach is indeed closer to an inductive than deductive research as its success hinges on the discovery of something new. Moreover, they stated that empirical data and theory are inevitably linked to each other, as theory is needed to understand empirical observation and vice versa.

However, abductive research has also some downsides. One of them is that the systematic combination of theory and empirical data often leads to theory refinement instead of theory invention (Dubois & Gadde, 2002). Further, some critics warn that researchers might not find the right balance between theory and method (Van Maanen, Sørensen, & Mitchell, 2007). As the abductive approach allows more flexibility to reconsider both, theoretical and empirical domains, and thereby allows boundary changes to chase methods, it might be more challenging to guarantee transparency to the reader (Dubois & Gibbert, 2010). To overcome this issue, Dubois and Gibbert (2010) suggest excelling openness and transparency towards the research process and the research ethics.