GEOGRAPHIC PROFILING

A SCIENTIFIC TOOL OR MERELY A

GUESSING GAME?

MEIT ÖHRN

Degree Project in Criminology Malmö University 6190 hp Health and Society

GEOGRAFISK PROFILERING

ETT FORSKNINGSBASERAT VERKTYG ELLER

BARA EN GISSNINGSLEK?

MEIT ÖHRN

Öhrn. M. Geografisk profilering. Ett forskningsbaserat verktyg eller bara en gissningslek? Examensarbete i kriminologi 15 högskolepoäng. Malmö högskola: Fakulteten för hälsa och samhälle, Institutionen för Kriminologi, 2016. Geografisk profilering har blivit en av de mest kontroversiella och moderna metoderna som används under brottsutredningar i nuläget. Framgången och tillförlitligheten av metoden är ett debatterat ämne inom forskningsvärlden. Den här studien ämnar att undersöka huruvida geografisk profilering är ett användbart verktyg för Polisen. Syftet med studien är att analysera hur väl metoden fungerar som ett verktyg och komplement till en brottsutredning samt om geografisk profilering är användbart inom bostadsinbrottutredningar. Genom att skapa en systematisk litteraturöversikt och utföra nyckelpersonsintervjuer fann författaren att geografisk profilering fungerar som ett utmärkt komplement till utredningar. Resultatet visade att de geografiska profileringsprogrammen inte alltid är mer framgångsrika än andra metoder inom området men att de oftast är konsistenta i tillförlitligheten. Resultatet visade även att metoden är användbar inom bostadsinbrottutredningar så länge profilen är gjord ordentligt och utav en utbildad analytiker. Studiens slutsats är att geografisk profilering är mycket mer än bara en gissningslek och kan identifiera gärningsmän om analysen är gjord av en erfaren utredare. Detta resultat diskuteras senare i studien, samt valet av metod och möjligheter för framtida forskning. Nyckelord: Bostadsinbrott, commuter, crime pattern theory, geografisk profilering, gärningsman, marauder, tillförlitlighet.

GEOGRAPHIC PROFILING

A SCIENTIFIC TOOL OR MERELY A

GUESSING GAME?

MEIT ÖHRN

Öhrn, M. Geographic profiling. A scientific tool or merely a guessing game? Degree project in Criminology 15 credits. Malmö University: Faculty of health and society, Department of Criminology, 2016. Geographic profiling is considered as one of the most controversial and innovative technologies used in criminal investigations today. The accuracy of the methodology has become a popular topic amongst scholars and has caused a heated debate regarding the success of geographic profiling. This study seeks to evaluate if geographic profiling is a useful tool for the police. Thus the aims of this study are to examine if the methodology is a viable tool during investigations and further to establish to what extent geographic profiling has been successfully applied within the area of property crime, in particular burglary investigations. By conducting a systematic literature review and key informant interviews this study found that geographic profiling can be a very useful tool for analysts. Further the results showed that geographic profiling systems are not always more accurate than simpler methods, however simpler strategies are not necessarily as consistent as a computerised system. Moreover the results indicate that geographic profiling can be applied during burglary investigations, if done correctly and by a trained investigator. The study concludes that geographic profiling is more than just a guessing game and if applied appropriately it will most likely identify the offender. Lastly the results and shortcomings of this study, including the need for future research is discussed. Keywords: Accuracy, burglary, commuter, crime pattern theory, geographic profiling, marauder, offender.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to express my very great appreciation to Professor Marie Torstensson Levander, my project supervisor, for her patient guidance, inspiration and indeed valuable and useful critiques of this project. I would also like to offer my special thanks to Dr. Kim Rossmo for his sincere and helpful advice to a very confused student, it was greatly appreciated. Further I also wish to acknowledge and extend my greatest appreciation for their participation to Mr. Magnus Andersson and Mr. Jonas Hildeby as they generously provided me with very valuable information for this project. Lastly I wish to thank my family and friends for their endless support and encouragement throughout this project, I could not have done it without you! Meit Öhrn Malmö, June 2016.TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. INTRODUCTION 6 1.1. Aim 6 1.2. Research questions 6 1.3. Disposition plan 7 1.4. Abbreviations 7 2. BACKGROUND 8 2.1. The art of geographic profiling 8 2.1.1. Generating a geographic profile 9 2.2. Geographic profiling and property crime 10 3. THEORY 10 3.1. Theoretical approach 10 3.2. Crime Pattern Theory 11 3.3. Situational Action Theory 12 3.3.1. Notes on other criminological theories 12 3.4. Journeytocrime & The Least Effort Principle 14 4. METHOD 14 4.1. Systematic literature review 15 4.1.1. Search criteria 15 4.1.2. Qualitative content analysis 16 4.2. Key Informant Interviews 16 4.2.1. Interview 1 17 4.2.2. Interview 2 17 4.2.3. Thematic analysis 18 4.3. Validity & Reliability 18 4.4. Ethical aspects 19 5. RESULTS 19 5.1. Geographic profiling, is it merely a guessing game? 22 5.1.1. Applicability & accuracy of the methodology 23 5.1.2. The importance of theory and expertise 24 5.2. Geographic profiling in burglary investigations 25 5.2.1. Generating accurate profiles in burglary investigations 25 6. DISCUSSION 26 6.1. Results 27 6.2. Method and future research 28 7. CONCLUSION 29 8. REFERENCES 31 9. APPENDIX 331. INTRODUCTION

One of the most controversial technologies used in criminal investigations today is geographic profiling. Not only has it caused heated debates amongst

criminologists but the methodology is also a popular topic in the media.

Newspapers and news networks such as CNN, Svenska Dagbladet, Aftonbladet and Svensk Polis have published several stories about the new phenomenon known as geographic profiling. The method has been used in several high profile cases, for instance in the Örebro rapist case and during the murder investigation 1 of the young girl Ida in 2015 (Svensk Polis, 2013; Aftonbladet; 2015). On both occasions the geographic profiles were a successful addition to the investigations and helped locating the offender. The methodology of investigative spatial analysis was first implemented in the late 1970s during the Hillside Stranglers investigation, when the Los Angeles Police Department used the technique to analyse the distance between dumping sites and abduction sites to locate the perpetrators (Rossmo, 2013). A similar investigative method was later used in the 1980s in England during the Yorkshire Ripper case, however it wasn’t until the 1990s that geographic profiling was fully established (Rossmo, 2013; Rossmo & Velarde, 2008). Scholars at Simon Fraser University’s School of Criminology developed the geographic profiling method that is frequently used today (Rossmo & Velarde, 2008). Although geographic profiling has had much success, the methodology has caused doubts with scholars and crime analysts, who have questioned if the achievements are purely a result of good luck, if the computer programmes used are as reliable as some scholars argue and if it only can be applied in murder cases. Clearly this has been the foundation for a heated debate that is still ongoing and which also spiked this author’s interest in the matter. The thought of a methodology that can ease the burden of identifying an offender in a criminal investigation surely must be what an ideal world looks like for an investigator. Thus it is important to evaluate geographic profiling as a tool used during police investigations to be able to establish the success of the methodology. 1.1. Aim The aim for this paper is to evaluate geographic profiling as an investigative tool used during police investigations. Further the aim is to assess if geographic profiling should be applied more often as a tool in investigations, particularly in burglary investigations. 1.2. Research questions 1. Can geographic profiling be a viable tool to use during police investigations? 2. To what extent can geographic profiling successfully be applied within the area of property crime, e.g. burglary? To be able to answer the first research question one must analyse the benefits and disadvantages of geographic profiling to establish the success of the methodology. 1 Also known as Hagamannen, author’s own translation.

Geographic profiling has received a lot of media attention and scholars have both praised and questioned the validity of the methodology. Therefore the word “viable” has been chosen for the first research question since the word allows us to explore the accuracy and implications of geographic profiling, in order to ascertain its usefulness. Further to establish the accuracy of the methodology this study will investigate individual offending patterns and how they interact with environmental and social settings as these factors are frequently used within the area of geographic profiling. The second research question is an attempt to establish the diversity of the methodology. Geographic profiling has especially been questioned since it has mainly been applied within violent serial crime investigations, thus the existing research is mainly based upon crimes such as murder and rape. Therefore this study will shed light on geographic profiling within property crime to explore if the method is an effective and viable tool to use during criminal investigations. Since the category for property crime is fairly large, as will be explained further in the next coming chapters, this study and the second research question will focus on burglary. Burglary was selected because there is existing, yet limited, research on this crime category and it has been debated amongst scholars if geographic profiling can generate accurate profiles regarding burglary, which is what intrigued the author to choose that crime category. 1.3. Disposition plan The disposition of this paper will include an introduction to the chosen topic for this study in chapter one, followed by a description of the background and history to geographic profiling and property crime, including the aims for this study (chapter 2). In chapter 3 the theoretical approach to this study will be discussed before the method section is introduced in chapter 4. The results from the current study will be presented in chapter 5 and later analysed in the discussion (chapter 6), until lastly the author will draw to a conclusion in the final chapter. 1.4. Abbreviations A few abbreviations are mentioned below that will be used on occasion in this study. GP Geographic profiling SAT Situational action theory NOA The Swedish National Operative Unit FBI Federal Bureau of Investigation

2. BACKGROUND

In the following section the history and background of geographic profiling will be discussed, including a short presentation of the crime category known as property crime. 2.1. The art of geographic profiling Geographic profiling relies on the basics of environmental criminology, including concepts and theories that scholars often use within the study of environmental criminology, e.g. Crime Pattern Theory, Circle Theory and Routine Activity Theory. This study will explore the Situational Action Theory and Crime Pattern Theory in an attempt to modernise the theoretical approach. These theories will be explained further in the next chapter. Brantingham and Brantingham (1981) laid down the foundation for spatial analysis by investigating and analysing patterns in crime in the early 1980s. They deduced that most offenders commit crimes in the near vicinity of their homes, or as they explain the socalled crime trip is short. By crime trip they refer to the distance the offender has to travel to commit the crime (Ibid; Brantingham & Brantingham, 1984). Studies show that as the distance from a perpetrator’s home increases, there is a decrease in criminal activity, a phenomenon that has been named “distance decay”. Distance decay refers to the notion that any routine activity an individual faces, for instance social interactions, work, school patterns and criminal behaviour all cluster around one central point of origin, such as a base location or home (Brantingham & Brantingham, 1981). To interpret these patterns one must remember that travelling a distance to commit a crime will require more money, time and determination by the criminal, thus usually closer locations will be preferred over distant locations, however it differs between offenders (Brantingham & Brantingham, 1984). It is important to remember that an individual moving within his or her home base will have more knowledge about the area than a criminal who has travelled a distance, hence areas close to home will be considered “good” targets (Ibid; Block & Bernasco, 2009). Offenders that tend to travel further to commit crimes have been categorised as commuters and criminals that stay closer to their anchor points or home whilst offending are known as marauders (Canter & Larkin, 1993; Kocsis et. al, 2002).

The two concepts have been the cause of a discussion between scholars if both types of criminals can be used when generating a geographic profile. Emeno et. al. (2015) explains that geographic profiling is better suited for criminals that fall under the category marauders. This is because research show that geographic profiles consisting of commuters currently have little accuracy compared to marauders (Paulsen, 2007). Rossmo (2005) provides four conditions which ought to be upheld in order to generate an accurate profile. The offences need to be committed by the same offender and preferably there should be at least five crimes linked together (1), the criminal should not have moved anchor points (2), the offender responsible should not travel to commit the crimes, i.e. should not be a commuter (3) and the criminal’s distribution of targets, i.e. the target backcloth, should be fairly uniform (4) (Ibid; Emeno et.al., 2015). The methodology underlying geographic profiling was initially applied to cases of violent serial criminality, e.g. murder and rape, but in recent years the technique has been used in investigations of serial fraud, arson and burglary (Rossmo & Velarde, 2008).

2.1.1. Generating a geographic profile Firstly one must understand that a geographic profile cannot solve crimes, only physical evidence, confessional statements or witnesses can be used during trials. Rather, geographic profiling is a tool that will assist the police in investigations to more efficiently reach one of the abovementioned resolutions in combination with other investigative means (Rossmo & Velarde, 2008). Geographic profiling is generally used to analyse repeated/series criminality since the computer software relies on data volume to be successful (Wang, 2012), however in recent years scholars have attempted to apply the software to single crimes that involves several crime sites (Rossmo, 2013). The crimemapping program includes an analytic engine, a geographic information system (what is also known as GIS), database management and of course a powerful visualisation tool. There are currently a few different programs that can be used to generate this geographic profile, i.e. Rigel, Dragnet and CrimeStat (Ibid).

The process of creating a geographic profile has a few steps. Firstly one needs to conduct a comparative case analysis which detects case similarities, e.g. connect crime locations, which will provide a more detailed investigative picture for the profile (Rossmo, 2013). Secondly, to consider different crime and environmental factors, an exploratory analysis of the data is conducted in order to generate an accurate geographic profile. Rossmo (2013) lists ten factors that needs to be reflected on when making a geographic profile, for example crime sites, physical boundaries, temporal aspects and arterial roads to name a few. With these factors Rossmo (2013) refers to that an offender, like any other individual, follow certain geographic patterns that, for example, can be affected by routine activities, the surrounding environment and psychological aspects. For instance, imagine a hypothetical case of a series of burglaries that have occurred in a city. To be able to apply a geographic profile to identify the offender one must analyse several crime factors and certain environmental aspects. For example analysing the location of the crime sites, some of them may differ from the others, including analysing the elements of the crime sites. In the case of burglaries have the offender stolen the same type of objects in every house (Ibid)? Further one must investigate the physical boundaries and arterial roads because, like any other human, a criminal have to travel using the existing roads or walkways, thus they will be restricted if they were to encounter a river or a mountain (Ibid). By distributing the crime sites on a map it is possible to find the routes the offender most likely used to access the house, but also the potential escape routes. Further it is indeed relevant to investigate the temporal factors of the burglaries since time, date and day of the crimes can provide wisdom of the criminal’s routine activities but it is likewise as important to put the crimes in chronological order to help with the investigation of the crime sites (Rossmo, 2013; Hildeby, 2012). Therefore it is important to consider the abovementioned factors before creating a geographic profile since forgetting one small detail, such as physical boundaries, would greatly decrease the probability of an accurate profile (Rossmo, 2013; Ainsworth, 2001). Once all factors have been taken into consideration it is possible to generate a geographic profile that can later be of use to investigators.

2.2. Geographic profiling and property crime According to Rossmo (2016) the speciality of using geographic profiling for property crime investigations was developed by the National Law Enforcement and Corrections Technology Center (NLECTC), which is a part of the US National Institute of Justice (NIJ), back in 2001 (Ibid). Geographic profiling has been used within the area of property crime for the past 15 years, however it has received criticism from scholars because research show that the methodology is not always applicable to property crime (Canter & Hammond, 2007). According to the FBI (2010) property crime includes burglary, arson, larcenytheft and motorvehicle theft. Arson placed within this category since it can be defined as destruction of property, which is also a definition of property crime. One of the most frequently discussed offences within the category of property crime is burglary, therefore burglary will be explored further in this study and not the other crimes within this crime category (Canter & Hammond, 2007). Brantingham and Brantingham (1981) explained that a burglar tend to choose a target that is located within a safe area for the offender, i.e. with an easy escape route. Moreover burglary criminals tend to travel further from their anchor points, i.e. base locations, to ensure that they will not be recognised by other people (Ibid). Burglars who travel to other locations will often commit more than one crime in that area since it requires more time, money and effort than committing an offence closer to their anchor point (Hildeby, 2012). Therefore one can assume that if there has only been a single burglary in an area, the offender has most likely been able to reach the location comfortably (Ibid). Further by applying geographic profiling to burglary cases it is possible to disclose the offender’s knowledge of the area, for instance if the crimes have been committed near highways or larger roads this could be an indication that the burglar does not have much knowledge about the area, compared to an offender that targets houses in neighbourhoods further away from the easy escape routes (Ibid). By travelling a distance to commit crimes, burglars fall within the category of commuters. As previously mentioned commuters are not always suited to include when generating a geographic profile, thus a cause for concern (Rossmo, 2005; Emeno et. al, 2015; Canter & Hammond, 2007). This issue will be further analysed later on in the thesis.

3. THEORY

In this chapter the theoretical approach to this study will be explained, including the theories that can be linked to geographic profiling. Although Routine Activity Theory and Rational Choice Theory are commonly applied within this methodology, this paper will shed light on a newer approach, i.e. Situational Action Theory, and the possible theoretical benefits when compared to the other theories. Further Crime Pattern Theory and the Least Effort Principle will be described since they are often used within geographic profiling. 3.1. Theoretical approach Geographic profiling is a methodology that is theory based. To understand the behaviour and patterns of an offender, profilers rely on theories such as Crime Pattern Theory, Rational Choice, Circle Theory and Routine Activity Theory(Rossmo, 2013). Human behaviour is often predictable since individuals usually follow the same routines and patterns in their everyday life, they create habits (Rossmo, 2000). Studies show that offenders, just like everyone else, have habits and patterns that can be fairly easily tracked, but also that criminals often deliberate, or rather there is a rational process of thought, before making a decision (Ibid; Wikström & Treiber, 2007). The opportunities and temptations that different environments offer are important aspects for a profiler to consider since the surroundings can explain the reasoning behind the chosen location, and the target. Theories can help investigators understand the criminal’s reasoning and are a good foundation for any investigation (Rossmo, 2013). In this paper Crime Pattern Theory will be discussed since it is one of the most fundamental theories applied within the methodology. Furthermore this study will shed light on the Situational Action Theory since it is a newer approach that uses both individual and environmental aspects. Rational Choice and Routine Activity Theory will be discussed shortly and compared to the Situational Action Theory towards the end of this chapter and a short description of the Circle Theory will follow. 3.2. Crime Pattern Theory Crime Pattern Theory is based on the belief that individuals learn about their environment when they go about their normal life, i.e activity nodes (Bernasco, 2010). An activity node is a place where an offender stops and executes activities for a certain amount of time, for example, as mentioned earlier these activities can be the person’s workplace, school, place for leisure activities and home (Ibid; Brantingham & Brantingham, 1981). Paths are the routes, or rather trips that an individual takes from one node to another. Together nodes and paths form a person’s activity space (Brantingham & Brantingham, 1984; Bernasco, 2010). An activity space is the trace of activity patterns and the geographical identification of an individual’s most common activity nodes and paths to the locations. Criminals, just as most people, spend most of their time not committing crime. Thus offenders tend to spend most time in non criminal pursuits such as one's home, workplace, school or shopping areas, making it easier to map criminal’s activity spaces since they would be fairly similar to non criminals (Brantingham & Brantingham, 1984). Within the activity space an individual is aware, to a certain extent, of their surroundings, this is what is known as awareness space. The awareness space is geographically limited since an individual will most likely only remember familiar and habitual paths and spaces (Ibid). Further awareness spaces are limited and after a certain amount of time after an offender moves into a new area their activity and awareness spaces become predictable. As previously discussed in accordance with the distance decay principle, the further away from a person’s anchor point, the less knowledge the individual will have of the area, i.e. their awareness space decreases in intensity as they move away from their normal activity spaces (Ibid). A criminal is bound to choose his or her target in a location where he or she feels safe. The areas with potential for “good” targets will most likely be subareas within the criminal’s awareness space (Brantingham & Brantingham, 1981). It is important to note that an individual’s awareness space is not necessarily fixed but can change over time. For instance a young offender will base his or her first crimes in an awareness space that is based on their non criminal activities but with due time the criminal will expand his or her horizons by edging into new and foreign areas (Ibid). Over time these foreign areas will be added to that offender’s

awareness space as they have learnt the surroundings of that particular area, thus indicating that awareness spaces are not fixed, but can expand depending on experience (Ibid). Crime pattern theory is a good example for showing that individuals are usually looking for a routine, or rather room for habit formation. Thus further emphasising that human behaviour is predictable, i.e. mappable, and can therefore be used in geographic profiling (Bernasco, 2010). 3.3. Situational Action Theory The Situational Action Theory (SAT) is a general theory of crime and moral actions. It seeks to explain some of the issues with criminological theory, i.e. causal mechanisms and the role of individual and environmental aspects in crime causation (Wikström & Treiber, 2007). The theory defines crime as a moral rule breaking, i.e. the notion that actions can be right and wrong. According to SAT, human actions are the result of how a person “(a) perceive their action alternatives and (b) make their choices” (Wikström & Treiber, 2007, p. 245). Wikstöm and Treiber (2007) explains that for a crime to occur, situational mechanisms, such as the setting (the physical and social environment) and a person’s traits and experiences will affect the decisions we make as humans, what can be explained as a moral setting. The theory centers on the morality of an offender, i.e. because people have different moral categories, i.e. moral judgements and moral habits, they are bound to act in different ways (Ibid). Committing a crime may indicate flaws in a person’s moral beliefs and habits, meaning that the offender’s belief of “right and wrong” might not be in accordance with another individual’s opinion (Ibid). Moreover SAT discusses that motivation, a person’s inclination to act on their action alternatives, causes opportunities which in turn cause temptation (Wikström & Treiber, 2007). Temptation is one of the most common motivational forces, thus it usually leads to moral rule breaking, i.e. acts of crime (Ibid). Whenever there is any form of deliberation before acting upon temptation an individual will go through what is known as a process of choice. The process of choice is a phrase used within SAT, which includes rational choice, free will, selfcontrol and finally deterrence. An individual must deliberate on all these things before making his or her decision to commit a moral rule breaking (Ibid). Selfcontrol is only part of the process if the individual deliberates on his or her options since Wikström and Treiber (2007) argue that when an act is committed out of habit there is no deliberation since habits are automated. It is interesting to use SAT when exploring the methodology of geographic profiling since it is somewhat based on rational choice and understanding the offender’s process of thought, or rather their mental map (Rossmo, 2000). As mentioned by Rossmo (2000; 2013) opportunities and temptations in certain settings are fundamental when an offender chooses a site for a crime, thus the criminal usually goes through a rational choice process of weighing pros and cons. SAT’s process of choice could therefore indeed be an excellent option to apply when investigating a geographic profile, since it includes all of the abovementioned criteria and also selfcontrol. 3.3.1. Notes on other criminological theories The reason SAT was chosen for this study is because it shares certain similarities with both Rational Choice and Routine Activity Theory, but further SAT also

highlights some of the shortcomings of the previously mentioned theories. For instance the Rational Choice Perspective describe that criminals often seek some kind of gain from their actions, e.g. money, and that individuals are guided by a process of making decisions using rationality (Cornish & Clark, 2014). This aspect of rationality can be found within SAT’s process of choice as well, however SAT has adapted the process of choice so that it explains all types of criminal behaviour, compared to the Rational Choice Perspective which Trasler (1993) argues is more focused on economic crime. Trasler (1993) also mentioned that Rational Choice is in need of another theory to complement the part of the perspective that is lacking, i.e. in this case an explanation regarding which factors that affect crime tendency. This is something that Wikström and Treiber (2007) has included in SAT in the form of moral settings. Additionally the moral settings discussed in SAT can to some extent be recognised within the Routine Activity Theory. Cohen and Felson (1979) clarify how opportunities for crime are created using their routine activity approach. According to Cohen & Felson (1979) crime is the result of three elements that converge in time and space, e.g. a motivated criminal (1), a good target (2) and absence of a capable guardian (3). They demonstrate that opportunities for crime are formed when one of these factors are missing, for example the absence of an adequate guardian (Ibid). Although Routine Activity Theory has been of use within geographic profiling because the theory is based upon routine activities, it is questionable if it is an ideal theory since it lacks individual aspects. As previously mentioned individuals follow geographic patterns, which can be affected by routine activities, however it is noteworthy to remember that the surrounding environment and individual factors (such as psychological aspects) are equally as important to consider when analysing a geographic profile (Rossmo, 2013). SAT includes both environmental and individual factors as causal mechanisms, thus it is preferable to use for this study (Wikström & Treiber, 2007). Moreover SAT discuss the notion of selfcontrol and how selfcontrol is a vital part of an individual’s process of choice, thus not an individual trait but rather linked to a person’s morality (Ibid). This type of analysis is missing in both Routine Activity Theory and the Rational Choice Perspective, therefore SAT was chosen for the current study. Further another theoretical approach often used within geographic profiling is the so called Circle Theory of Environmental Range (Canter & Larkin, 1993; Kocsis et. al., 2002). Circle Theory is to some extent based on the early work of Brantingham and Brantingham (1981), as it is established on the notion that a criminal’s choice of crime site is usually related to that offender's point of origin, i.e. anchor point (Kocsis et. al., 2002). Thus there is a presumed fixed area known as the “home range” and an area called “the criminal range”, i.e. the spatial area in which the offender has committed his or her crimes (Ibid). The Circle Theory is important to consider in regards to burglary investigations as these offenders tend to be classified as commuters (Paulsen, 2007). A commuter is an offender that has his or her home base outside of their criminal range, compared to a marauder which often commits crimes within his or her home range (Ibid).

Figure 1. The figure shows the criminal range and home range for a marauder and a commuter. The concepts marauder and commuter will be explained more in depth later on in this thesis as they are of high importance when generating a geographic profile, thus Circle Theory will be used to some extent in the study. 3.4. Journeytocrime & The Least Effort Principle The journeytocrime is an important factor that profilers take into consideration whenever they generate a geographic profile. As previously mentioned scholars have found that offenders do not necessarily travel far from their anchor points to commit crime since travelling requires time, money and effort (Brantingham & Brantingham, 1984). An individual does not want to travel further than they must to achieve their goal, in this case a crime. The journeytocrime research is based upon the least effort principle, sometimes also known as the nearness principle by geographic profilers. The principle is built upon the notion that humans are comfortable beings and will not travel too far from their comfort zone. For instance, if you were to ask a person to go and buy a carton of milk, that person would most likely go to the nearest shop they could find. The same principle can be applied to crime, which is why the journeytocrime aspect is important to consider in any investigation (Brantingham & Brantingham, 1984).

4. METHOD

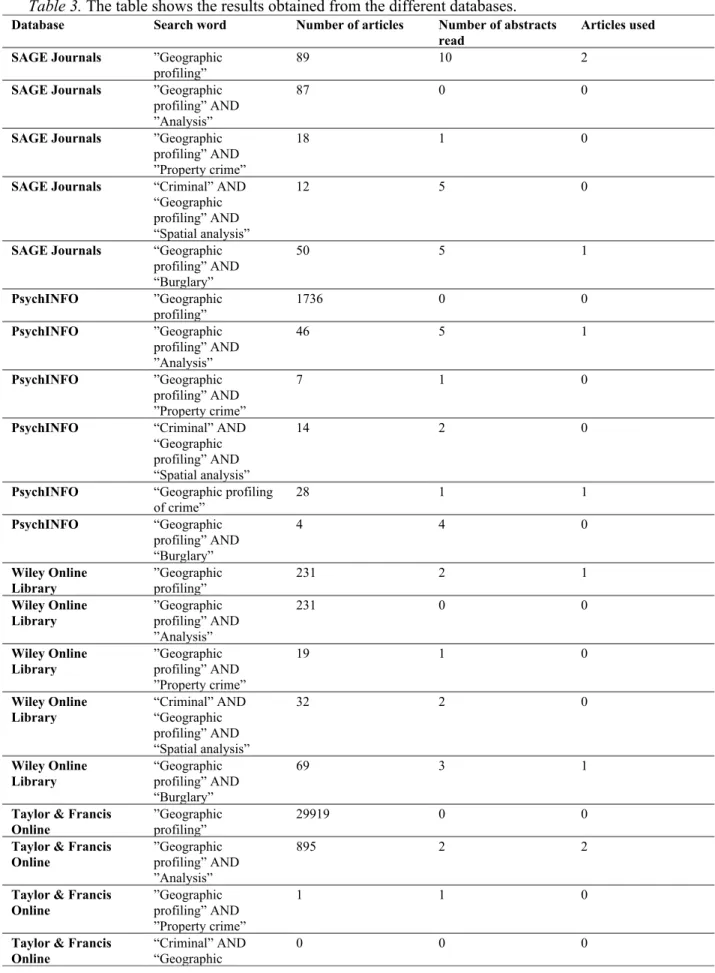

This study is of a qualitative nature as the aim is to reach a greater understanding regarding geographic profiling as well as evaluate the methodology, thus a study of quantitative nature would not be as suited. The methods used for this paper were a systematic literature review and two key informant interviews. To be able to achieve the best results to answer the research questions it was decided to use both a systematic literature review and interviews. (Bryman, 2008). By combining two different sources of data it is more likely to get a wider understanding of geographic profiling and it is a way to facilitate the search for valid and useful data. Furthermore by using two different methods to gather information it will improve the study’s external validity since the data gathered is not only international but also Swedish, thus conducting the interviews was a given choice.4.1. Systematic literature review A systematic literature review was conducted in order to gather relevant data for this paper. By using a systematic literature review one will ensure that the chosen data has been collected in a systematic manner and therefore there should be transparency, i.e. one should be able to replicate it. Further a systematic literature review should aim to identify the relevant research within a specific field of study, in this case geographic profiling (Forsberg & Wengström, 2015). The studies selected should be critically reviewed, and ought to present different opinions in regards to using the methodology. There is no set number for the amount of studies one should use for a systematic literature review, thus for this particular thesis nine studies were chosen, since they fulfilled the relevant criteria for the study (Ibid). The criteria will be discussed further in the next section. 4.1.1. Search criteria For this systematic literature review four databases were used to ensure the most relevant articles were found. The databases, SAGE Journals, PsychINFO, Wiley Online Library and Taylor & Francis Online, were accessed via Malmo University’s library website. The reason these databases were chosen was because they have been recommended by lecturers and librarians previously, thus they were automatically the databases selected for the study. The following words were used during the search: “geographic profiling”, “geographic profiling” AND “analysis”, “geographic profiling” AND “property crime”, “criminal” AND “geographic profiling” AND “spatial analysis”, and “geographic profiling” AND burglary”. The words “geographic profiling” were evidently chosen due to the topic of the paper, but they were put together with quotation marks since it was not desired to get any hits on offender profiling. Since the majority of research you find when putting profiling in the search box concerns offender profiling this was not an optimal word for this study as it does not aim to include that particular area, thus it was excluded. Further the words “analysis” and “spatial analysis” were chosen since these are commonly found in the literature, thus of high relevance to the current study. Lastly “property crime” and “burglary” were used in the search since that is the crime category that is applicable to the aim of the paper. Table 3 with the full list of number of hits per word can be found in appendix I. Additionally there were a couple of inclusion and exclusion criteria chosen, for example only peerreviewed articles were included in the search since those were most relevant for a scientific study. Moreover to assure that all articles were relevant for police investigations, the studies chosen were either written by a former investigator or they were based on criminal records. Further there was a timespan added to the criteria to ensure the articles included were not outdated, therefore only articles from 19902016 were used. Any study conducted prior to 1990 have been used in the background chapter of this thesis, thus building the foundation for the modern research. Of course one should note that for this part of the study only secondary sources were used since there was simply not enough time to conduct a study of larger magnitude. Fortunately, as you will notice later in this chapter, the interviews will provide the primary source data for this thesis.

4.1.2. Qualitative content analysis One of the most frequently used approaches to analyse documents is a qualitative content analysis. The method involves a search for the themes that highlight the documents, i.e. the studies used for the systematic literature review (Bryman, 2008). For this study the following themes were selected, with consideration to the research questions; geographic profiling (1), accuracy/effectiveness (2), theory (3), burglary (4). Table 1. The table shows the recurring themes found in the articles used for the systematic literature review. Author & year of publication Type of study Themes

Snook et. al., 2005 Quantitative study 1, 2 & 4 Emeno et. al., 2015 Quantitative study 1 & 2 Kocsis et. al., 2002 Quantitative study 1, 3 & 4 Paulsen, 2007 Quantitative study 1, 2, 3 & 4 Bernasco, 2010 Quantitative study 1, 3 & 4 Block & Bernasco, 2009 Quantitative study 1, 2, 3 & 4 Paulsen, 2006 Quantitative study 1 & 2 Canter & Hammond, 2007 Quantitative study 1, 2 & 4

Rossmo, 2005 Qualitative study 1 & 2

N= 9, N= number of articles included. In table 1 it is possible to see that most of the articles used for this study are of a quantitative nature. To explain mainly quantitative studies were selected one must understand that the existing research on geographical profiling is mainly based upon this method, thus qualitative studies are not commonly found. Moreover using themes was a strategic decision as this will facilitate the analysis by placing the articles into different categories that will be further discussed in the results and the discussion chapters. 4.2. Key Informant Interviews Two key informant interviews were conducted for this study. The interviews were based on a snowball sample, i.e. contact was initially made with one of the key informants and this person was later used to establish contact with the second key informant (Bryman, 2008). This is a form of convenience sampling and it was preferred because it ensured that the people interviewed had relevant knowledge of the topic. One issue with snowball sampling is that it is improbable that the sample will be representative of the population, however this was an uncertainty worth taking since the professional knowledge of geographic profiling in Sweden is still fairly limited (Ibid). Further a semistructured interview design was used since it gives the interviewees some leeway in their replies but it also makes sure that certain topics, or rather questions, were covered. Similar interview guides were used for this study, however in interview 2 a couple of questions were added since this key informant had a great deal of knowledge regarding geographic profiling. It is important to note that when the initial interview guide was written, it was done without many preconceptions, i.e. by writing it before the literature was scrutinised, to ensure the best results. A semistructured design entails that the process is flexible since it adapts according to the direction the interviewee, i.e. by letting the interviewee “ramble” or follow their train of thoughts, one can

get insights to what that person considers relevant to the topic (Bryman, 2008). Thus for this study the key informants were encouraged to express their opinions. The design is preferable since it allows structure, but there is also conversational, twoway communication. Further the design can contribute with reliable and comparable qualitative data. A disadvantage of semistructured interviews could be that proper interview skills are required and one needs to interview a number of people to ensure a generalizable result. Due to the time frame only two interviews were conducted, which can be rather ominous, however this is why a structured literature review was organised as well. Moreover the interviews were conducted in Swedish, thus the material included in this paper has been translated to English by the author. 4.2.1. Interview 1 The first interview was conducted with the Chief of the Intelligence Analyst Unit in Malmö, Sweden. The interview was conducted facetoface at Rättscentrum in Malmö and took approximately 25 minutes. The interview took place in a fairly busy setting unfortunately which could have had an impact on the interview, however since the interview was conducted at the person’s workplace one can assume he was comfortable in the setting. The interview went well and the interviewee answered the questions and elaborated on some. Due to the location of the interview, i.e. a building of the Swedish courts, it was not possible to record the interview. Thus notes were taken during the interview instead, however this could be seen as a weakness in this particular interview since the analysis relies on the interviewer’s notes and memory. The key informant was informed of the right to confidentiality and although he was comfortable with using his name in the study the author has opted not to due to ethical reasons, i.e. confidentiality, therefore he will be referred to as IP1. 4.2.2. Interview 2 The second interview was conducted with an Intelligence Analyst/ Geographic Profiler working for the Swedish Police’s National Operative Unit (NOA), located in Stockholm, Sweden. This interview was organised and later on conducted over the phone since the time frame for this paper did not allow for a trip to Stockholm. A telephone interview can be a disadvantage since one cannot observe body language or record the interview, however studies show that there are possible benefits of phone interviews, i.e. it is cheaper and asking sensitive questions by phone can be more effective since the interviewee may be more relaxed since the interviewer is not physically present (Bryman, 2008). This particular telephone interview went very well indeed and it took approximately 30 minutes. As previously mentioned the interview was not recorded since it was done over the phone, thus the transcription and analysis relies on the interviewer’s notes and memory. The interviewee seemed at ease during the interview and the interview was indeed very fruitful, the interviewee even offered to send some reports regarding geographic profiling and burglaries in Sweden. The key informant was informed of his right to confidentiality and he was also comfortable with the interviewer using his name in the current study, however as previously mentioned due to confidentiality and the sensitivity of the matter he will be referred to as IP2.

4.2.3. Thematic analysis

A thematic analysis was chosen for the interviews since the purpose was to focus on what was said, not how it was expressed (Bryman, 2008). The notion of a thematic analysis is to create an index of the existing themes and subthemes in the interviews and then present them in a matrix. These themes are basically recurring patterns one can find in the text when thoroughly analysing and reading the transcribed texts from the interviews (Ibid). Before one can find core themes though, it is necessary to transcribe the interviews, i.e. you modify reality and experiences to text (Malterud, 2012). There are four steps to follow when conducting a thematic analysis according to Malterud (2012). It is important to grasp the overall judgement of the transcribed interview before finding the core themes in the text (1). Further one needs to ascertain the parts of the transcribed interview that are significant for the analysis (2), later these parts are categorised into different categories, or rather sub themes that will give insight of the meaning of the themes (3). Lastly (4) one summarises the transcription using the themes found during the analysis into a rational statement (Ibid). Table 2. The matrix shows the five core themes used in the thematic analysis and the sub themes, or categories, chosen. Further the significant units in each sub theme has been coded in numbers. The numbers represent the key informants, i.e. the first numbers labelled 1 and 2, and then the units of significance. By numbering the units of significance it was easier to code the transcribed material from the interviews.

Core Theme Sub Theme Units of significance

Geographic Profiling Generating a profile 1:1, 2:4, 2:8 Computer programmes 1:2, 2:11 Type of cases 1:3, 2:2 Man vs. Computer 1:2, 1:1, 2:9 Applicability Currently used 1:4, 1:1, 2:1, 2:4, 2:6 Accuracy 1:2, 1:3, 2:4, 2:5 Complement to investigations 1:5, 1:3, 2:6: 2:9 Theory Principles used 1:6, 1:1, 2:10 Rational Choice 2:10, 2:2 Usefulness in field 1:4, 2:4, 2:6 Expertise People qualified to use GP 1:7, 2:6 International 1:8, 2:7 Sweden 1:7, 1:8, 2:6 Cases The Haga case 2:2 The Bus shootings’ case 1:3, 1:1 The Örebro Rapist case 2:2, The Ida murder case 2:2, 2:10 A matrix was made to show the chosen themes and the procedure of the thematic analysis. The core themes were selected since the topic were reoccurring throughout the transcribed texts, thus they seemed suited for the analysis (Bryman, 2008). Further by not inserting any quoted data in table 1 it is not as confusing to read. 4.3. Validity & Reliability Validity and reliability are two important aspects when assessing the quality of a study. The criteria might be more commonly discussed within quantitative

research, however it is equally as relevant to evaluate when conducting qualitative studies as well (Bryman, 2008). Internal validity refers to what extent the observed data coincide with the theoretical ideas that have been established, i.e. are you identifying or observing what you intend to? For this particular study the internal validity has been guaranteed by defining the keywords used and explicitly explaining the research questions and the conduct of the study. However the internal validity may be questioned since the sampling of participants was not random, nevertheless a snowball sampling was necessary to find the best suited key informants (Forsberg & Wengström, 2015). The external validity concerns if the finding of the study can be generalised (Bryman, 2008). Due to the small sample used in this study the external validity may be questioned (Forsberg & Wengström, 2015), however since research regarding geographic profiling is fairly limited this was unavoidable . The reliability of a study regards to what degree a project can be replicated, e.g. the study should be transparent so that another scholar can conduct a similar study (Bryman, 2008). Thus the method chapter of this paper is fairly detailed and the data used has been shown in tables to ensure that anyone can follow the same steps to conduct the literature review for instance. However one cannot be sure that another person would interpret and analyse the articles or the transcribed interviews the same way as this author, therefore one cannot guaranteed they would achieve the same results as in this study (Forsberg & Wengström, 2015). 4.4. Ethical aspects Ethical issues arise when social research is conducted in a few different forms, for instance in regards to informed consent, privacy concerns and participants (Bryman, 2008). There was no need to apply to the ethics council for this study since the participants were only questioned regarding their professional life, however to ensure they were informed about the study an information letter (see appendix II) was sent to them beforehand. The letter included aspects concerning confidentiality and that participation was voluntary. As it happened both key informants were at ease with the author using their names in the study, however to protect their confidentiality their full names will not be used in this thesis. Further they were informed that they would have access to the final draft of the paper, including a copy of the transcribed material if they inquired about it. Since one of the participants sent the author two reports this material has been handled with care, thus no specific information will be used from them, due to the sensitive nature of the reports. Moreover all other material, i.e. transcribed material, will only be accessible to the author and after the submission of the paper the material will be disposed.

5. RESULTS

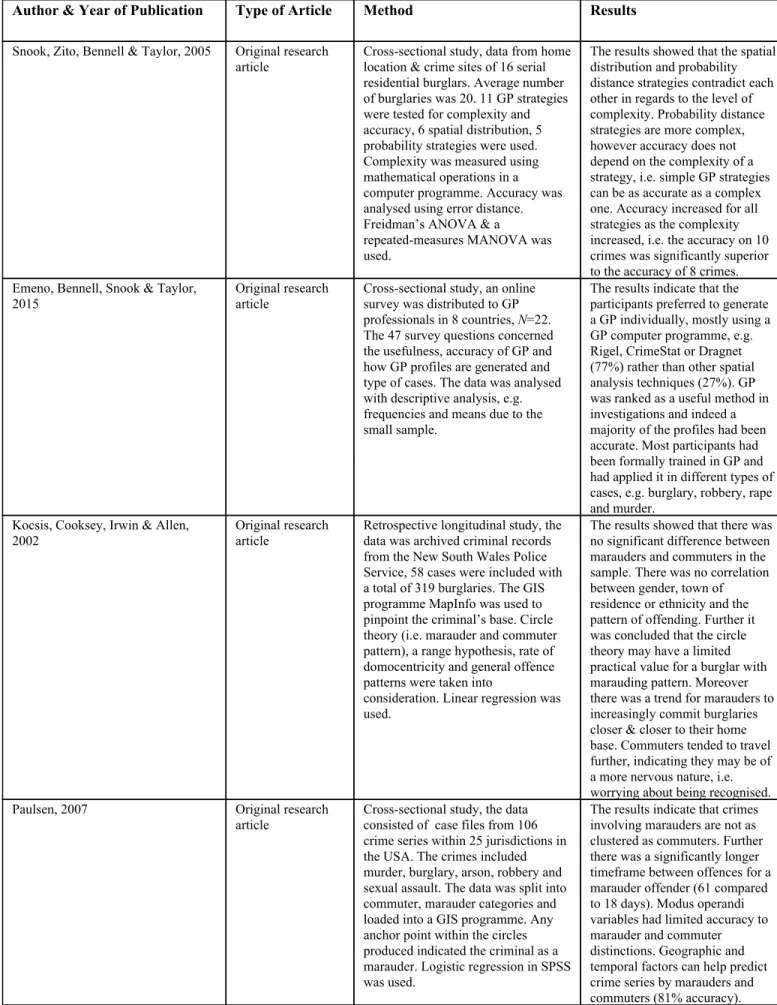

In this chapter the results from the systematic literature review and the interviews will be analysed. Further the results will be presented based on the research questions this study is exploring. Firstly the question regarding geographic profiling as a viable tool during investigations will be analysed and lastly the research question regarding the applicability of the methodology in burglary investigations. The analysis is based upon the core themes chosen for the systematic literature review and the two key informant interviews.Table 4. The table shows the results from article 14 in the systematic literature review.

Author & Year of Publication Type of Article Method Results

Snook, Zito, Bennell & Taylor, 2005 Original research

article Crosssectional study, data from home location & crime sites of 16 serial residential burglars. Average number of burglaries was 20. 11 GP strategies were tested for complexity and accuracy, 6 spatial distribution, 5 probability strategies were used. Complexity was measured using mathematical operations in a computer programme. Accuracy was analysed using error distance. Freidman’s ANOVA & a repeatedmeasures MANOVA was used. The results showed that the spatial distribution and probability distance strategies contradict each other in regards to the level of complexity. Probability distance strategies are more complex, however accuracy does not depend on the complexity of a strategy, i.e. simple GP strategies can be as accurate as a complex one. Accuracy increased for all strategies as the complexity increased, i.e. the accuracy on 10 crimes was significantly superior to the accuracy of 8 crimes. Emeno, Bennell, Snook & Taylor,

2015 Original research article Crosssectional study, an online survey was distributed to GP professionals in 8 countries, N=22. The 47 survey questions concerned the usefulness, accuracy of GP and how GP profiles are generated and type of cases. The data was analysed with descriptive analysis, e.g. frequencies and means due to the small sample. The results indicate that the participants preferred to generate a GP individually, mostly using a GP computer programme, e.g. Rigel, CrimeStat or Dragnet (77%) rather than other spatial analysis techniques (27%). GP was ranked as a useful method in investigations and indeed a majority of the profiles had been accurate. Most participants had been formally trained in GP and had applied it in different types of cases, e.g. burglary, robbery, rape and murder. Kocsis, Cooksey, Irwin & Allen, 2002 Original research article Retrospective longitudinal study, the data was archived criminal records from the New South Wales Police Service, 58 cases were included with a total of 319 burglaries. The GIS programme MapInfo was used to pinpoint the criminal’s base. Circle theory (i.e. marauder and commuter pattern), a range hypothesis, rate of domocentricity and general offence patterns were taken into consideration. Linear regression was used. The results showed that there was no significant difference between marauders and commuters in the sample. There was no correlation between gender, town of residence or ethnicity and the pattern of offending. Further it was concluded that the circle theory may have a limited practical value for a burglar with marauding pattern. Moreover there was a trend for marauders to increasingly commit burglaries closer & closer to their home base. Commuters tended to travel further, indicating they may be of a more nervous nature, i.e. worrying about being recognised. Paulsen, 2007 Original research

article Crosssectional study, the data consisted of case files from 106 crime series within 25 jurisdictions in the USA. The crimes included murder, burglary, arson, robbery and sexual assault. The data was split into commuter, marauder categories and loaded into a GIS programme. Any anchor point within the circles produced indicated the criminal as a marauder. Logistic regression in SPSS was used. The results indicate that crimes involving marauders are not as clustered as commuters. Further there was a significantly longer timeframe between offences for a marauder offender (61 compared to 18 days). Modus operandi variables had limited accuracy to marauder and commuter distinctions. Geographic and temporal factors can help predict crime series by marauders and commuters (81% accuracy).

Table 5. The table shows the results from article 59 in the systematic literature review. Author & Year of Publication Type of Article Method Results Bernasco, 2010 Original research article Crosssectional study, three types of data was used; records from the Hague Police Force (random sampling), population registration data records & data from the national postal code database. 3,784 individuals were included for the analysis. Descriptive statistic and a multinominal/conditional logit model were used for analysis. The results suggest that an area where a criminal has lived or currently lives is prone to be chosen for committing an offence. Further the criminal is 36.72 times more likely to commit a crime in their home/base area than a previous place of residence (8.63 times). Moreover an offender tends to select areas where they’ve lived more recently and where they lived for a longer period of time. Block & Bernasco, 2009 Original

research article Crosssectional study, data from police records was used to find 62 criminals who had been involved in burglaries (5 or more). A total of 573 burglaries, the offenders were split into marauder/commuter categories. The empirical Bayes method was applied to the data. The Friedman test and the Cochran test were used. The results from the study reveal that the conditional risk surface was significantly more likely to predict the offender’s home. All risk surfaces were more accurate for the marauder category since the distance decay principle is not applicable to commuters. The empirical Bayes method is a viable tool for investigators and the results support that the method should primarily be applied to “common crimes”, i.e. robbery, burglary. Paulsen, 2006 Original

research article Crosssectional study, the data was based on a data set of 247 serial crime series, random sampling was used to get a sample of 25 crime series. The data was analysed using 7 algorithmbased methods and 3 spatial distribution methods. 25 students acted as “judges”. Several accuracy measures, e.g. simple error measurement, error distance analysis were employed to evaluate how accurate the GP methods are. The Friedman’s test and a Chisquare test was applied to the data. The results indicate that the 3 spatial distribution strategies performed better than the other methods. There was no significant difference in the error distance measurement when comparing the profiling methods. Further the results revealed that the algorithmbased profiling methods were not more accurate than the spatial distribution methods. Canter & Hammond,

2007 Original research article Retrospective longitudinal study. The data consisted of 92 burglary series, 1998 to 2001. Total number of crimes was 1600. The data was mapped with ArcGIS. The offender's anchor point was predicted using the coded data. Applying prioritisation methods the perpetrators/suspects were given a rank depending on the distance travelled. Dragnet was used for the analysis. The ranking achieved by the logarithmic function and centre of gravity methods in Dragnet were most efficient out of the prioritisation methods tested. The criminals were mostly located within the top 5 % of the ranking, thus indicating that GP is indeed applicable for burglaries. Rossmo, 2005 Secondary

research article Commentary to Snook, et. al’s (2004) study on GP. The reply includes a commentary on their study and the shortcomings, e.g. if the data fitted the assumptions needed for GP and that Snook et.al did not analyse all serial crimes included. Further the analysis is questioned as error distance is not always accurate. For a geographic profile to be accurate one should include the five GP assumptions. Further instead of using error distance, area is recommended as the most accurate measure for a profile. The data and analysis used by Snook et. al. were not suitable for the study. Moreover the two heuristics applied, distance decay and circle heuristic, are not used appropriately.

5.1. Geographic profiling, is it merely a guessing game? There are four conditions that ought to be followed when generating a geographic profile according to Rossmo (2005), e.g. that the crimes are linked or that the offender is not a commuter. However Emeno et. al. (2015) argue that often geographic profiles are generated even though one or more conditions are violated, for instance the offender has moved anchor points or he or she is a commuter. This is a cause for concern because mistakes such as missing one of the assumptions can affect the accuracy of the geographic profile, thus it will not be as useful in an investigation (Rossmo, 2005). Further one might question why profilers would violate the conditions and scholars have found that often the reason is due to a lack of training or experience (Emeno et. al. 2015). Noting that certain conditions can implicate a geographic profile it is important to understand that if all assumptions are met it is more likely one will generate an accurate profile (Rossmo, 2015). Further the debate on geographic profiling computer systems, e.g. Rigel, Dragnet and CrimeStat, are interesting since scholars have very different opinions regarding accuracy and usefulness (Paulsen, 2006; Snook et. al., 2005; Canter & Hammond, 2007). For instance regarding issues such as if the computer programmes can be used by the police during investigations. CrimeStat and Dragnet have proven to be more research based systems, e.g. CrimeStat is mostly statistics on a map and not very useful for operative field work (Canter & Hammond, 2007; IP2; Block & Bernasco, 2009). Rigel is the geographic profiling system that is used frequently by the Swedish Police, however it has proven to be expensive (IP1; IP2). Snook et. al. (2005) showed that complex strategies, such as probability distance strategies, are usually incorporated into the geographic profiling systems that are used today. These complex strategies are indeed useful, however they require months of training, thus taking time and effort from the police authority wishing to purchase the systems (Ibid). Therefore Snook et. al. (2005) argue that simpler spatial distribution strategies may be a more suited choice since it does not require the same amount of skill. However the simpler strategies, e.g. error distance, often have “an ‘X’ marks the spot” (Paulsen, 2006, p. 82) approach which is a serious shortcoming. “People often assume geographic profiling is some sort of magic wand where you get an ‘X’ on the map telling you the location of the offender, that no knowledge or resources are required. It is simply wrong2.” (IP2) Geographic profiling does not give you an exact location of the perpetrator, rather it is a tool that provides investigators with a smaller area to search, in which hopefully the offender has his or her anchor point (IP2; Paulsen, 2006; Rossmo, 2005). Further it is important to note that geographic profiling is only a tool that can be used to identify the offender, thus it should not be used as evidence in courts (IP1; IP2). For example in the Örebro rapist case geographic profiling helped the investigators by narrowing down the search into different areas, thus knowing which of the 1000 suspects would be of interest to the investigation, however it could not be used as evidence (IP2). 2 Author’s own translation.