VT20

FACULTY OF EDUCATION AND SOCIETY

Department of languages, culture and media

Degree project in the major subject:

English and education

15 credits, advance level

Perceived Reality vs Taught Reality

in Compulsory School

Content based teaching in an unbiased setting

Herolinda Bici

English studies and Education, 300 hp Examiner: Shaun Nolan 2020-06-07 Supervisor: Chrysogonus Siddha Malilang

Acknowledgemets

I dedicate this project to Roland Gerbeshi, my mentor in life and my source of wisdom and peace who passed during the process of this study.

I would also like to extend my gratitude to my supervisor, Dr Chrysogonus Siddha Malilang for the great advice and encouragement throughout this process. I have been extremely fortunate to have received such support.

Lastly, I am forever thankful to everyone who participated in this study because without you, there would be no quality.

Abstract

This paper examines how we discuss social issues in the L2 classroom under the guidelines of Lgr11. To answer this, I ask the following sub-questions; How are the overall goals of education and parts (see Appendix B) of the Curriculum for English currently perceived by English teachers? How are the social subjects in the L2 classroom currently handled? Thirdly, what kind of lesson plan can be implemented in the classroom context under the guidelines of Lgr11? Looking at past research and relevant documents along with the qualitative data and through a triangulation of evidence carried out consisting of semi-structured interviews, supported by netnography research I propose a lesson plan using the collaborative action research model. All data was collected through technical means such as Zoom, phone calls and Facebook groups. The results of the interviews with teachers have shown that there is a unity in some respects with similar interpretations of Lgr11 and the curriculum. As well as differences of views and approaches concerning social issues in the L2 classroom. Based on the netnography research findings, most tasks given consisted of receptive skills while productive skills were used less. The netnography also supported the interview findings in the claim that popular topics were used more, whereas unpopular topics were neglected significantly. CLIL as a method was found to be absent in most of the collected data with some exceptions.

Keywords: ESL, CLIL, student-centred teaching,semi-structured interview, teacher-centred teaching, critical thinking , netnography, action research

Table of contents

1.Introduction

...12. Purpose and research questions...3

3. Theoretical perspectives...4

3.1 The motive behind Lgr11...4

3.1.1 Content and language integrated learning...5

3.1.2 The English curriculum and CLIL……….6

3.2 Student-centered and teacher-centered …………..……….………….7

3.3 Objectivity and subjectivity teaching………8

3.1.3 Critical thinking in the L2 classroom……….……9

4. Method...11

4.1 Action research...11 4.1.1 Action model...12 4.2 Semi-structured interview...13 4.2.1 Selection process...13 4.2.2 Participant background...14 4.2.3 Research procedures...15 4.2.4 Netnography...15 4.3 Data coding...16 4.4 Ethical considerations...175. Results

...18 5.1 Needs analysis...185.1.1 Student influence and lesson content...18

5.2 Social media data collection...20

5.2.1 The categories of the collective data...22

5.2.2 Fun and common vs uncomfortable and rare...22

5.2.3 Receptive vs productive skills ...23

5.2.4 Content and language integration...23

5.3 Lesson plan outline...24

5.3.1 Thirteen reasons why – motivating the lesson plan...25

5.3.2 Considerations...25

6. Discussion

...266.1 English teachers and Lgr11...26

6.1.1 Social issues in the classroom...26

6.1.2 Lesson plan of CLIL implementation...27

7. Conclusion...30

8. References...31

1

1.Introduction

As Ben Parker in Spider-Man puts it, “with great power comes great responsibilities” and it has never been so true as it is for teachers today, particularly for English teachers. Considering how English as a language has entered our lives so effortlessly, in a natural setting, it is to no surprise that an increasing number of Swedish students are now able to express themselves in a more purposeful manner using English as a means of communication. It is a natural part of everyday life be it through social media, games, movies and dramas or interpersonal ties. Teachers as well as students are experiencing and exchanging culture and expressions beyond borders. As individuals of a globalized and a highly technical world, our frames of reality are being broadened.

Interpretations and knowledge are most commonly expressed through language and as Kramsch (2010) puts it “human beings do not live in the objective world alone, nor alone in the world of social activity as ordinarily understood, but are very much at the mercy of the particular language, which has become the medium of expression for their society” Access to information is overwhelmingly increasing, which gives space for alternative arguments, narrations, descriptions, and expositions that go beyond what we once were exposed to in our angle of the world. In return, this helps shape our perception of things.

Meanwhile, The Committee of Education (2014) state that knowledge is not the imaging of reality but a human construction. Thus, no matter who we are, as we all process everything on an individual level and our world is open for interpretations. Knowledge is therefore not true or false in its absolute meaning, but something that can be argued and challenged. The views of what is knowledge has changed and is proven to be highly dependent on its time and place (Freire, 1970/2017).

2

Our current time and place consist of teens exposed to a great deal of information from an early age (svenskarochinternet, 2017). The annual look into Swedish annual internet habits reveal that 43% of children search independently on their devices for information, meanwhile 39% of children use their search devices for schoolwork (svenskarochinternet, 2018). Knowing that English is represented massively online, this comes with pros and cons for English teachers. One of the positive aspects to consider is the students’ great amount of exposure to the English language. However, with no preparation to interact with the online world safely and responsibly, teens are using technical tools that can easily access hard topics such as alcohol and drugs, pornography, self-harm among plenty other difficult topics. This creates a high demand for discussion to promote a deeper understanding of social issues and to better prepare our students for the real world.Except, as language teachers, we may not know how to take on this great challenge.

Based on my own teaching experiences, teachers tend to rely on what could be considered a safe approach by simply focusing on mostly pleasant topics that will promote language learning and less on the difficult subjects. The democratic mission of the Swedish school is to prepare students to be responsible and productive citizens and this requires a greater learning. With a shift of focus on the student’s needs, CLIL (content and language integrated learning) as an approach focuses on content and language simultaneously. This allows learners to take an active part of the teaching plan, participate in it and process information through their own existential experience and through interaction (Coyle, Hood & Marsh, 2010). The new curriculum that took shape in 2011 is offering no concrete solution as to what this knowledge concretely looks like (Svd,2019). Consequently, this creates a greater room for teachers to translate and process the curriculum in various ways which makes education highly subjective.

With the overwhelming access to sensitive data that may or may not be in line with our mission, in regard to what’s considered a reliable source of information, our role as teachers is being challenged where we are to create a learning experience and uphold the core values the Swedish schools rests upon. This is in correspondence to the individual’s education in “morals, generosity, tolerance and accountability” (Lgr11). Considering the issues we are faced with as English teachers, this paper seeks to find how we discuss social issues in the L2 classroom

3

2. Purpose and research questions

The purpose of this paper is to examine how we discuss social issues in the L2 classroom under

the guidelines of Lgr11. Questions A and B are meant to investigate the teachers’ viewpoint,

how they perceive the official documents, as well as how social issues are integrated in the L2 classroom (See Appendix B). Questions A and B provide a foundation for the creation of a lesson plan, through question C.

The questions I connect to the purpose are:

a. How are the overall goals of education and parts (see Appendix B) of the

Curriculum for English currently perceived by English teachers?

b. How are the social issues in the L2 classroom currently handled?

c. What kind of design possibilities can be implemented in the classroom context under the guidelines of Lgr11?

4

3. Theoretical perspectives

In this section, relevant parts of the Swedish curriculum are presented. Moreover, theory such as concepts related to the focus of this study are also provided.

3.1 The motive behind Lgr11

In the government proposition of a formation of what would be known as Lgr11, it clearly states the new curriculum was meant to “concretize the goal requirements for both teachers and students and increase the goal completion” (Utrikesdepartementet, 2008:12). The previous goal system and the difficulties expressed for teachers at school was claimed to be “vague” and “impenetrable”. The investigation revealed the section ‘the goals to strive for’ had been one of the causes resulting in difficulties to fulfill the goal system that was in place before Lgr11. Additionally, the investigation in place concluded that teachers were left with a great margin for interpretation when the curriculum coincided with the course syllabi.

For this reason, The National Agency for Education laid out official recommendations for teachers as support to plan and carry out lessons based on the curriculum and the syllabus in Lgr11. It consists of different sections where the purpose of each subject and grade including the long-term goals where the central content is described and revealed as this is essential to be able to provide students with an equivalent education (Lgr11).

5

In the current curriculum, there are little to no regulations to how the teaching experience should be (Fredriksson & Westerholm, 2018. According to some educators and experts, Lgr11 was meant to strengthen the emphasis on knowledge but failed to do so as it was “revealed” the officials at the Agency for Education, let the previous curriculum invade the new one (Svd, 2019). The argument given is Lgr11 lacks concretion of what students are supposed to learn, where it for instance is expected they learn to discuss but nowhere does it state what the content should looks like. Consequently, this could result in a future of young adults lacking knowledge, as well as independence and active citizenship in the society therefore arguing for a revolutionary curriculum with clear content, progression, and clear goals (Svd, 2019). In the overall goals and guidelines for compulsory school, it is clearly written that students should be able to consciously determine, and express ethical standpoints based on the grounds of human rights and basic democratic values, as well as personal experiences (Skolverket, 2011). Moreover, the students should be given the opportunity to develop their ability to draw connections in relation to content and their own experiences, life condition and interests on a wider spectrum as teachers are not told what that content must be.

3.1.1 Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL)

Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) is the theory and practice of a “dual-focused” approach where content and an additional language are taught simultaneously. It is a fusion of the two, proving to have multiple benefits where the student will enhance learning, other aspects of educational, social or personal development which are all major reasons for CLIL (Coyle, Hood & Marsh, 2010). When the teacher pulls back from “being the donor of knowledge and becomes the facilitator, as it is often found in CLIL practice, forces are unleashed which empower learners to acquire knowledge whilst actively engaging their own and peer-group powers of perception, communication and reasoning” (Coyle, Hood & Marsh 2010:6)

There are attempts to make learning a shift in experience where learners take an active part of the teaching plan, participate in it and process information through their own existential experience and through interaction. All in support of the “global change, converging technologies and adaptability to the subsequent Knowledge Age” (Coyle, Hood, Marsh 2010:18), CLIL (Content Language integrated learning) is “adapting” education to the current world we live in.

6

As the cognitive along with the knowledge processes within CLIL, is in place to “ensure all learners have access to developing these processes, but crucially they also have the language needed to do so (Coyle, Hood, Marsh 2010:30).”

Bloom’s taxonomy formed by Dr Benjamin, in the purpose of transforming the learning experience, making it more than remembering facts, shifting towards a higher learning (Orey, 2010). Thus, the pyramid was formed to present a prototype of a potential learning advancement. It has been updated since the original model in 1956 (Coyle, Hood, Marsh, 2010), Before being able to reach a higher learning, learners need to go through the different process dimensions, starting with the lower-order processing which entails remembering, understanding and applying preparing one for the higher-order processing, for analysing, evaluating and creating (Coyle, Hood, Marsh, 2010). The knowledge dimensions of the processes are “factual, conceptual, procedural, metacognitive” (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001).

CLIL, bilingual education focusing on a content subject taught in a foreign language partly or fully, is based on Krashen’s language acquisition model as well as Vygotskijs Zone of Proximal Development putting forth the four Cs content, cognition, communication and culture.

3.1.2 The English curriculum and CLIL

In the Swedish curriculum for English learners, the language learning is not merely about extending the vocabulary and knowing the irregular verbs. In addition, Lgr11 requires more than knowing how to take an order or ask for directions. The English requirements presented in Lgr11 point to students being able to “reflect on life conditions, societal questions and cultural phenomenon in different contexts and different parts of the world where English is being used” (Skolverket, 2011). This reveals that the purpose of teaching the language goes beyond the nouns and the verbs. In addition, it requires the student to implement English in a context that is linked to other subjects such as social studies.

Through CLIL and its many approaches “goes beyond language learning” with its planned “pedagogic integration of contextualized content, cognition, communication and culture into teaching and learning practice” (Coyle, 2004).

7

In contrast, Mehisto (2008) argues CLIL is complicated in its form and taking on the task can result in “malfunction” where advocates for the method do not actually state both content and language goals, which suggests the dual focus is impractical for teachers.

According to Bruton (2018) teaching content may divert away from the focus of the language learning and especially for less privileged students. According to Coyle, Hood and Marsh (2010), the implementation of CLIL into one’s classroom can be changed and adapted “ to suit any context without compromising the need to address fundamental issues of effective and appropriate integration of content and language learning” making it easier for teachers to pick and choose what to apply “starting small”.

Based on the goals for English, it is expected that students develop skills with an emphasis on teaching content. As the goals express, a student should be able to “briefly discuss some

phenomenon in different contexts and areas where English is being used and be able to make

simple comparisons through their own experiences and knowledge”(Lgr11). Moreover, the student is to show their understanding by briefly explaining, discussing, and commenting on content and details and by, through acceptable results, act based on the message and instructions in the content.

3.2 Student-centred vs teacher-centred

Contrary to teacher-centred learning which is the transmission of knowledge from the expert to the novice (Harden & Crosby 2000), a traditional approach where the power is primarily with the teacher, student-centred learning is ‘the shift from the expert teacher to the student learner driven by need for change in the traditional environment’. A focus where students were passively “apathetic” and “bored” (Rogers, 1983).

Additionally, Rogers (1983) exclaims students are in need of an authority figure confident in their role and in their relationship with others that they experience “an essential trust” in the willingness and capability to accept others to think for themselves, to learn for themselves. There are countless of scholars that seem to express the need of a shift in the classroom where teachers should not “interfere” with the process of “maturation”. Instead they should rather be a support system and a guide for the student to learn, connecting it to “readiness” and how a child will essentially learn once the child is ready to (Simon, 1999).

8

The need for a shift in education, has been raised by Freire (1970/2017) who introduces how the classroom mirrors the society as an oppressive state, where the teacher-centred way is equal to a dictatorship. He goes on to reveal a list of ways this takes place for instance how ‘the teacher teaches and the students are taught’ or ‘the teacher knows everything and the student knows nothing¨ presented among them as part of what Freire (1970/2017) calls the Banking

Concept which he describes as knowledge ‘considered a gift by those who consider themselves

knowledgeable onto those they consider to know nothing’.

When a teacher “gives” what’s considered valuable knowledge, and students continuously store the “deposits” given to them, they fail to develop their own critical consciousness ‘which would result in their interventions in the world as transformers of the world’ (Freire, 1970/2017). Although, one would think it does not have a place in the modern form of foreign language teaching, Grammar Translation as a method is still being used to promote language learning through strong on vocabulary and grammar rules. The Grammar Translation Method, a teacher-centred approach, was mostly used between 1840-1940 to “perfect” foreign language and still is, to this day, in modified forms. It is a method in which learners share the “tedious experience memorizing endless lists of unusable grammar rules and vocabulary and attempting to produce perfect translations of stilted or literary prose” (Richards & Rodgers, 2001) where the teachings are not adapted to its time and place. Essentially, the Grammar Translation has no advocates although it is widely used as it is an approach with no theory behind it (Ibid).

3.3 Objectivity and subjective teaching

Objectivity, being based on facts and not influenced by personal beliefs or feelings, is what is expected of us as teachers when dealing with students and moreover, it serves as a reminder that the school itself is a “neutral” place where we carefully and consciously word ourselves, making sure our language is as neutral as possible. This raises the question to what extent it is even possible. According to Hooks (1994) it all starts with accepting and facing the fact that most of us have been taught “a single norm of thought and experience” and for this reason, many learned to continue to “legacy” of this outdated approach to a reality far more complex, especially Hooks (1994) takes into account multiculturalism and how it fails to include other perceptions.

9

In what many refer to as a conservative form of teaching, Freire (1970/2017) writes about a

narration sickness in a setting where teachers are seen as the subject and students objects ready

to take in information. In contrast to this, Lgr11 encourages students to be active participants and influence their education. Skolverket (2019) clearly states that students should be part of the planning stages of a lesson plan. In addition, students’ own opinions and experience are to be taken into consideration including the aftermath, when the lessons have taken place and been evaluated. Moreover, it is important that the influence of the students should increase with age. The older the student, the more maturity will determine their ability to choose options freely concerning their own education (Skolverket, 2019).

Literature is one way of actively working with social issues from a critical pedagogical viewpoint, where Tyson & Park (2006) believe expanding the reading experience dealing with social realities, both positive and negative, will contribute in the development of the understanding and attitudes of caring, empathy and civic courage. Teaching itself becomes an especially ‘important action for social justice. By promoting the use of day to day experience of the students to provide a spectrum of perspectives in the classroom’ (Ibid). To further development Tyson & Park (2006) argue teachers could help students gain critical awareness of social issues in literature development promoting self-empowerment within the environment of the classroom.

3.1.5 Critical thinking in the L2 classroom

Michael Scriven and Richard Paul (1987) define critical thinking as “the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skilfully conceptualizing, applying, analysing, synthesizing and/or evaluating information”. In other words, this goes beyond cogitating by “observation, experience, reflection, reasoning or communication, as a guide to belief and action” (National Council for Excellence in Critical thinking, 1987).

Paulo Freire (1970/2017) as well as by Moacir Gadotti (1996), Peter McLaren (2002) and Carlos Alberto Torres (1998) within the Critical Pedagogy arena all stress the importance of applying critical thinking in language learning. They especially highlight the aspects which involves students getting the opportunity to express differences and of opinions, dialogue and empowerment, along with action and hope. However, cultural studies have shown that this

10

approach has been neglected in education, where the method has been replaced with “memorisation and interpretation of facts and by cultural generalisations or even stereotyping”. Generett (2009) believes critical thinking to be the most essential tool allowing change to be possible, no matter where an individual is from and whatever may be their reality. Engaged

pedagogy formulated by Bell Hooks (1994) promotes freedom in education and gives power to

the learner, allowing them to articulate their thoughts, ideas and opinions in the classroom. Generett (2009) recalls being told by her past professor to “claim her place” and give voice to a reality, something only each person could speak on alone looking at the world from one’s own eyes and in this case, giving voice as an African-American and as a woman.

Through a critical eye of one’s cultural understanding and political awareness, we disconnect ourselves from the order of things as we know them to be, to be able to see them from a critical standpoint in terms of what our boundaries of power may be, whether we are teachers or students. These are the teachings that “requires refusing the language of the dominant, the functionalist, the positivist, the ways of essentialising and of simply making our own practice serve the goal of implementing things” (Freire, 1970/2017).

Diaz-Greenberg and Nevin (2010) emphasize the importance critical reflection focusing on the student teachers in their path to awareness of their own personal and professional experiences of their role as critical pedagogues.

Dissentis, a disagreement of opinion, important for building competence in dealing “critically

and successfully with opposition and even conflict through critical awareness towards the self and others through honest and balanced negotiation” (Alison M & Guilherme, 2004).

The critical dialogue as part of the process of Critical Pedagogy, is the link between critical reflection and critical action by which the teachers and students can find a shared acceptance of voices. The need to give the suffering a voice is for Giroux (2014), an essential part of the work, raising social issues focusing on those who have been submitted to different forms of societal injustices such as sexual abuse and racism where the educational system isn’t designed to prepare these individuals to be critical citizens in the world being part of a system that neither allows or requires them ‘to make the most of their present lives both as individuals and as members of communities’. Giroux (2014) believes that Pedagogy of Responsibility helps counter this phenomenon, educating young people simultaneously for a professional future and accessing a critical citizenship (Alison M & Guilherme, 2004).’

11

4. Method

This paper takes a qualitative approach as it is meant to bring out the complexity of life based on the social phenomenon with a focus on the participant’s standpoint (Williams, 2007:67). To answer the first two research questions, I have chosen to collect data through semi-structured

interviews and netnography. This will contribute in answering the third question where the

findings are meant to help shape a lesson plan using an action research model to integrate social issues in the L2 classroom through CLIL as a method. For an increased reliability, three sets of data are implemented, creating a triangulation of methods to help strengthen and confirm findings (Heale, 2013). Triangulation as a strategy is used to increase the validity of evaluation and research findings. It eliminates the bias that can occur when using one single method through a combination of methods (Rahman, 2012).

The sections below are meant to describe and discuss the ways of collecting the empirical data with the methods into consideration, the process, considerations, and the data collection.

4.1 Action research

The gathering of data and formulating theories is normally where research ends, and it is the most common way to conduct it. Through action research, the possibilities go beyond this point. The action approach allows one to make real changes in the field of target, improving the setting based on the gathered data.

Action research is when professionals study their own practice in order to improve it (GTCW, 2002) but before the point of gathering data, the researcher looks at a situation and defines a problem (Stringer, 2013) and when this is achieved, the data comes is used to reflect on the possible causes of the outcomes.

12

In order to understand, evaluate, change and improve educational practice (Bassey, 1998), action research is a practical option as it emphasizes the problem-solving aspect making it a highly attractive approach to researchers (Bell, 1999:10).

4.1.1 Action model

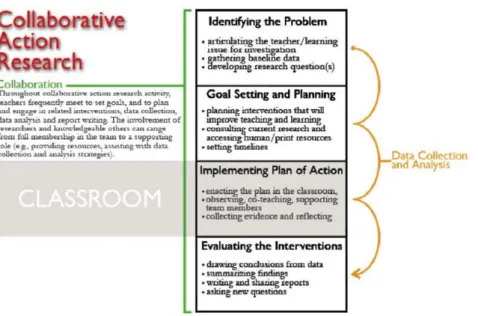

Action research invites an expert from the outside to collaborate with educators from the inside, to produce new knowledge. This collaboration distinguishes this form of action research, as it is typically done by individual educators with no collaboration in place (Johansson E, Emilson, A & Maija A, 2018). Through Collaborative Action Research, the inside perspective helps narrow down the gap between research and practice which then, gives way for real change and transformations to be made in schools (Bruce, Flynn & Stagg, 2011). The method consists of the identification of a problem followed by goal setting and planning, followed by the

implementing of the plan of action resulting in an evaluation of the interventions (see Figure 1).

This study will be based on Collaborative Action Research, although the implementation of the plan will be left unexplored. The focus will be put entirely on the Identification of the Problem as well as Goal Setting and Planning based on the collection of theories, interviews and findings as further work would require a form of a field study.

Figure 1. Collaborative Action Research (Bruce, Flynn & Stagg – Peterson 2011, Capobianco 2007)

13

4.2 Semi-structured interview

An interview comes in various forms, but the semi-structured approach is unique in its way of focusing on one respondent at a time. With a blend of closed and open-ended questions where follow-up questions are a natural part of the process, it is undoubtedly time-consuming and unpredictable (Adams, C.W. 2015).

This method, rather than structured interviews or case interviews, gives a deeper meaning to the individual, in exploring the depth of the mind and the ways in which we perceive/act naturally. It is also more practical with the current state of covid-19 limiting interaction and means to go about research in the school setting.

4.2.1 Selection process

In the search of English teachers of years 7-9 to partake in virtual interviews, I joined and posted requests on Facebook groups with thousands of potential candidates. I offered further information in the form of a letter (See Appendix A) to those who reached out and expressed interest in the study. This strategy made my choice of teachers highly randomized, limitless and highly voluntary. Willing participants responded to partake in a virtual interview, which would be possible on Zoom.

14

4.2.2 Participant background

All four interviewees are situated in different parts of Sweden giving a wider share of perspectives.

The schools the participants work in also differ in size and form. Three out of four of them are community schools and one is a private religious school.

Figure 2. Map of interviewees’ range of zones

To add, the subjects’ experience in teaching is ranging from 1-40 years.

- Interviewee A, based in Stockholm country having taught in different schools for 40 years and is currently retired but remains active in promoting and inspiring other teachers to use CLIL, having used the method since the mid-90s.

- Interviewee B, based in Dalarna County, a sparsely populated area. has been teaching English at a community school for at least six years, currently teaching from home due to covid-19.

- Interviewee C is a new teacher who has near completed the first year working as an English teacher for year 7-9 at an independent school of about fifty students in Skåne region.

- Interviewee D has been teaching for six years and works at a community school of 300 students, in the Västnorrland County. The participant is also a certified history teacher.

15

4.2.3 Research procedures

Confirming consent and proceeding to interview either on Zoom, or the phone, became the standard approach for all four participants. The interview was initially expected to take thirty minutes, but it varied between 40-90 minutes depending on the participant’s need to express further details.

Each participant had given consent after carefully being advised to read through the letter (see appendix A). Together, we decided on a date that was suitable and the subject was given the questions beforehand, and in Swedish. The two first interviews were held on the phone, as we experienced complications using Zoom. The calls were also recorded. Zoom was used with subject C and D and was also recorded.

I took notes during the interviews to prevent losing valuable data if anything technical were to go wrong. After each interview, I listened to the recording and made denaturalized

transcriptions of what had been said. Denaturalized transcripts emphasize how “within speech

are meanings and perceptions” that construct our reality (Cameron, 2001), and using this approach, helps capture the true essence of the interviews in this study.

4.2.4 Netnography

As part of a triangulation, Netnography is used in this study as a complementary component to the semi-structured interviews. The intention is to “capture the natural practices of what a lesson entails” (Kozinets, 2011) and to solidify the findings and gather more data and a wider understanding in what the current English classroom situation consists of. It is a method that derives from traditional ethnology and even if the focus remains on the individual, netnography is overwhelmingly used with a focus on social media.

As Kozinets (2011) exclaims, “In Netnography, social media research is human research”. Furthermore, the author (2011) explains how netnography is a “specific approach to conducting ethnography on the internet” with all its traits, belonging to the qualitative arena, as it is highly interpretative. Kozinets (2015) goes on to argue that Facebook with its active monthly users constantly increasing, making it, along with social media and the internet that are all widespread, “already recognized for changing politics, business and social life”, making it a worthy candidate of research attention.

16

Furthermore, the data gathering process and analysis requires the researcher to take an active part by joining the target community, to “become familiar with the context and the social aspects of the communities”. Through a thematic analysis, a method used to analyse qualitative data usually used on a set of texts for the researcher to closely examine the data to identify common themes.

4.3 Data coding

An essential feature of netnography is the use of categories, “which are repeatedly assessed and modified, if required” (Kozinets, 2015). To determine which skills and topics are most commonly being put into practice, each piece of data was split into different categories. The reason as to why receptive and productive skills were included and interesting for this study, was to comprehend to what extent students practise their reading and listening skills in comparison to their speaking and writing abilities. As Naiditch (2017) exclaims, critical thinking “does not require memory”. In addition, critical thinking requires more than the gathering and storing of information. In fact, it is about applying knowledge (Naiditch, 2017). Moreover, there was an attempt to see what kind of topics were part of language learning to determine if they consist of popular or unpopular topics. At last, there was an attempt to see which categories were potentially emphasized or neglected, also trying to see to what extent CLIL is used as a method.

Receptive skills were identified as listening and reading activities where students would take a

passive role in the making of a product contrary to productive skills, where the focus is writing and speaking based on active participation.

Productive skills were identified as speaking and writing where students would take an active

participation in second language usage.

The popular topics represent the lighter, oftentimes more fun, basic and ‘normal’ subjects.

Note that some of these topics can sometimes be uncomfortable yet belong to this category simply because it is socially acceptable to talk about it.

The unpopular topics are oftentimes uncomfortable, more complex, unconventional, rarely

17

CLIL seeks to find if the methodology is being used in the L2 classroom. This is determined

when English is used to teach a subject area. Note that it may be used more, but perhaps not expressed in the posts.

4.4 Ethical considerations

Informed consent is an important part of the process. The interviewee must be made aware of what the study entails and what is expected of them before any interview could take place. In reference to The European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity (2017), the research subjects were handled “with respect and care” throughout the process. The information regarding the interview was sent outin the form of a letter (see Appendix A) on a private Facebook message prior.

For one, the letter deals with confidentiality and the recording of the session was made clear beforehand. To confirm the participant’s awareness of the session being recorded, once more, I asked for consent in the beginning of each recording to make it clear.

4.5 Considerations

Due to technical difficulties, the two first interviews were held on the phone offering time benefits. However, it gives a different dynamic to the discussions where our social interaction was limited. The use of word and tone of voice because of the absence of face-to-face contact was therefore significant. The technical difficulties created difficulties of the first interview which may also affect the answers given. My overall experience was that Subject A took the time to respond to the questions thoroughly and did not express any rush or fatigue.

Another aspect to take into consideration is the aspect of time which was a miscalculation from my end having expected it would only take thirty minutes when, it took longer than anticipated. Most likely, the questions required more time to be answered thoroughly as all participants were encouraged to elaborate and give examples when discussing the different issues.

18

At last, the range of experience and background amongst the four interviewees is at great variance which is also an aspect to consider.

19

5. Results

For clarity of presentation, the results are presented within a ‘needs analysis’ corresponding to the “Identifying the problem” from the action research model which will help shape a lesson plan.

5.1 Needs analysis

Essentially, this section seeks to show what the interviews reveal, followed by the findings of the online research. Lastly, lesson plan will be shaped through the collected data and theory.

5.1.1 Student influence and the lesson content

Interviewee A expresses how students are the “great part” of the subject’s planning and how every new theme is introduced with a blank sheet. When the blank sheet is revealed to the students, they are surprised. The purpose is for them to “fill it” and decide what they would like to work with. Whichever proposal gets the majority votes is what is . Interviewee A emphasizes how “students should be allowed an active role in their education and given the voice to help form their lesson plans. motivate and give their learning personal meaning” (Interviewee A).

For teachers to be objective is a given to all interviewees even if it is expressed by interviewee D that it is “super hard but it is something teachers must be regardless”. Subject D goes on to explain that even the choice of books and movies is a biased statement on the teacher’s part simply because the teacher has chosen the material. Meanwhile, subject A feels the objectivity as a teacher is no difficulty and goes on to state that it is extremely difficult to teach year 7-9 students as they interpret everything, and teachers must always be attentive to this.

“High school students have their own imagination - you can never enter a student's head and interpret that student. The students interpret things through their own frame of references and from their experiences in life” (Interviewee A).

20

Interviewee B explains how important it is to be objective as a teacher especially since it is the students that have lots of opinions. “It is important that you do not just get into a subject as a teacher but actually make sure it contributes to something meaningful. That you feel comfortable that you can handle whatever comes up I believe is important for it to become as good as possible” (Interviewee B).

Interviewee A further believes using CLIL as a method has been proven to work as unmotivated students have expressed a liking to English that they had never experienced before, simply because they were given the freedom to choose topics they liked. Additionally, interviewee A feels students hardly ever question their grades as they are part of their own assessment, which allows more insight into their personal development when stating that she has taken the part where the curriculum writes, students should be part of planning “literally” (Interviewee A).

Interviewee B gives space for students to choose areas to work with related to a specific topic the teacher in question picks out. The topics are determined by the abilities that are the focus. Interviewee C picks out material that seem interesting and fun based on the subject’s own interests.

Interview D works out themes in collaboration with the other English teacher at school getting most material from textbooks and the internet. The focus is put into making sure there is some connection to the English-speaking world when deciding for topics. The students get to see the central content for them to understand what they will be working with.

Interviewee A and B, both expressed they mainly use the internet in search of material meanwhile subject C uses different media and no textbooks meanwhile subject D combines the internet and textbook.

To work with goals such as ‘reflecting on living conditions, societal issues and cultural

phenomena in different contexts and parts of the world where English is being used’ (Lgr11),

it appears the interviewees work with this goal in similar ways, letting the student pick which English-speaking country they are interested in learning more about. This can either be a limited (American states) or an unlimited (all English-speaking countries included) choice for the students to make usually resulting in most of the students picking “the typical” countries like England, Ireland, Australia, USA and New Zealand.

21

The teachers also explain how there is always a trend where at least one student wants to pick something “super-exotic”. Exceptionally, Interviewee 3 expresses the choice of country for students usually is fifty-fifty between the common and uncommon places also highlighting the importance for the students to particularly focus on captivating facts may it be related to history or geography and discuss those differences in particular. This way they also get to compare and discuss countries to their own experiences and knowledge of life.

Meanwhile interviewee B believes these goals “can easily become too broad for the students”, therefore putting an emphasis on concretizing each goal for instance when connecting to student’s experience, doing it through specific tasks such as “Christmas in Sweden in relation to an English-speaking country”.

5.1.2 Sensitive/unconventional / the common and the uncanny

There are topics each of the interviewees would likely avoid for different reasons. Firstly,

sexual orientation is avoided by interviewee A as there is always that one student in every

class suspected of being homosexual and bringing up this topic can make some students very uncomfortable and worst case scenario, even targets of harassment.

Interviewee C also chose to avoid discussing the topics of sexual orientation and pornography in year 7 when it was suggested by a colleague. The subject believes students would

“probably not be mature about it and it would only lead to a negative atmosphere”. One of the many reasons is believed to be due to the school’s identity and the students’ backgrounds. “Even if it would probably be alright to talk about it, as it is part of our mission at school” (Interviewee C).

Interviewee C also believes that many would oppose the discussion simply because it is against their beliefs. Usually hard topics are part of subject C’s mentorship, rather than the English classes even if it may be talked about to some extent there as well.

Interviewee A goes on to express that the best way to keep a good atmosphere in a classroom where students care more about how they are perceived by the other classmates, than learning itself – teachers need to take this into account and make the learning experience as

comfortable for them as possible. “Unless the students bring up a topic themselves, its best to avoid the sensitive subjects for the students’ sake” (Interviewee A).

22

Interviewee B feels that sex education would be “uncomfortable” to talk about and does not know what to say about it. The subject believes the main focus should be put on the language

learning and “what is talked about comes secondary, as long as we speak. Thereby, topics

such as Goals and Dreams, is something everyone can relate to – therefore also talk about” (Interview B). The subject expresses how one is becoming more brave dealing with different topics. In the beginning one often chooses what feels simple, oftentimes from the textbook to begin with, and in these books, usually lighter topics are dealt with such as goals and dreams or love, and then it becomes a natural part of learning.

Subject B continues to state “a teacher has to see where the discussion is going and if one can handle it as a teacher. Topics such as violence and cancer must be in a context. I cannot have abortion as the main subject, but rather a part of feminism perhaps.” The interviewee agrees that there is a sense of doubt because it is not easy to talk about topics such as racism but “maybe it is what we need to talk about anyway. Maybe we are scared sometimes and pick love instead.”

Interviewee D believes it is vital to talk about sensitive topics, stating that subject D believes one becomes inhibited when avoiding everything that is hard:

” This is children that are growing and developing and I believe there is a risk that teachers oftentimes avoid things that one finds difficult to talk about. Then the students will find the answers in other places. It is obviously things that they have questions about and that is important for them to take a stand on issues in relation to the world.”

When asked if there is a certain age one should talk about social issues believe subject D does not believe teachers need to avoid any topics simply because students are too young. “It all depends how you talk about it, and how you put the discussion at a level that is suitable for the students and from their perspective” (Interviewee D).

However, Interviewee 4 believes rape wouldn’t be part of the subject’s lesson plan and although believing it to be important to teach students what given consent is all about, it is impossible for any teacher to know if it is a sensitive topic for the students. “We know statistically speaking, and from experience, that there are students that have been victims of sexual abuse” (Interviewee D).

23

5.2 Social media data collection

As groups on Facebook are public, it makes it possible for researchers to use the data available without any restrictions. Collecting the data that was presented within the group made it possible to find what the topic range is, possible trends, possibilities, and limitations and what the considerations might be.

Through a Facebook group consisting of thousands of English teachers in Sweden, teaching year 7-9, all the activities and themes that had been posted dating back to January 2020, have been collected and included in this study. The findings within the categories of which the data then was split into, is presented in the next section.

5.2.1 The categories of the collected data

The data below reveals what skills and tasks were most frequently used for year 7-9 students in English as well as how widely used CLIL was based on the findings alone. The data findings (see graph in Appendix E) show below:

Receptive skills: 38,48% Productive skills: 17,02% Light topics: 38,22% Heavy topics: 5,24% CLIL: 1,05%

5.2.2 Fun and ‘common’ vs uncomfortable and unusual

It is to no surprise that the lighter topics are predominant in the lesson plans taking into account the interviews. When discussing hard topics, it is oftentimes described as something ‘heavy’. Some express that they would also like to work with the same content, but they do not know “how” referring to the American drama, Thirteen Reasons Why. Others discussed how it is a “heavy” drama that requires curator support to be handled in a group context

24

meanwhile others doubted their students “could handle such a drama” (post,2019). There were also teachers who completely dismissed it stating that it is advisable to leave it for the upper secondary school.

5.2.3 Receptive vs productive skills

Based on the data collection, receptive skills were used more frequently. This could be due to many reasons, one being the practice of the national test where the receptive skills tested take place in the spring term.

However, as a key rule in CLIL all skills should be practiced of every lesson in some way (Coyle, Hood & Marsh, 2010) and according to the collected data online, there is an emphasis on listening/reading. Of course, it is impossible to investigate every classroom and very unlikely, are they only working with the content posted on the forum. Regardless, the results show a significant difference in the use of receptive versus productive skills and mostly consisting of movies, old national tests and books. Many times, it is not expressed if the teacher in question would have the students process the receptive product in an interactive way making use of students’ own cognitive engagement and skills which enables the learner to think for themselves and articulate their own learning to further acquire new knowledge (Coyle, Hood & Marsh, 2010).

What is expressed is that many of the movie/book choices are based on the teachers’ own liking and there is also a trend where other teachers are asked for suggestions of material. All while reading is as important as any other skill and helps ‘develop understand and attitudes of caring, empathy and civic courage’ (Tyson & Park, 2006) including voices that are not

typically included in the traditional literature can be invited to classroom discussions (ibid), nowhere in the forum was it expressed the students had taken part in the choice of material, although some teachers requested content their “students would find interesting”.

When looking at the findings that clearly showed that most content was receptive, it suggests students may not acquire new knowledge developing thinking skills (Coyle, Hood & Marsh, 2010) if the reading and listening material isn’t being processed productively. This is also aligned with Freire’s (1970/2017) emphasis on the experience of how knowledge “only emerges through invention and re-invention” as something vital.

25

According to Freire (1970/2017), learners to be in charge of their own minds, by giving their perspective and discussing the views of the world “explicitly or implicitly manifest in their own suggestions and those of their own comrades” (Freire, 1970/2017) as the education itself cannot present its own agenda but must be in search of content with the learners involved in the process, participating in the formation based on their suggestions giving them an active role throughout the work.

5.2.4 Content and language integration

CLIL as a method is not mentioned in the Facebook group as such but there were a few teachers that had expressed a collaboration with other subjects and these were taken into consideration. There was no insight in “how” it was managed which therefore remains unknown in this study and whether it was CLIL-based.

Another interesting aspect is the recurring topics that are mentioned in the posts, with a substantial amount of those, not merely focusing on language but content as well.

5.3 Lesson plan outline

I utilize CLIL and its principles (2010:80) to form a lesson plan (see Appendix D). Parallel to the gathered data, this section outlines what possibilities there are when dealing with social issues using “the four C’s” (Coyle, Hood & Marsh, 2010): content, cognition,

communication, and culture.

5.3.1 Thirteen Reasons Why – motivating the lesson plan

Thirteen Reasons Why is a popular ‘Netflix drama’, also considered inappropriate and “too

heavy” to include in the L2 classroom according to the findings on the online teacher forum. Yet, most adults who engage with teens probably know the series is something students will be watching regardless, as predicted by Interviewee D. Cognitively speaking, teens may not be able to handle this kind of content by bench-watching a drama such as 13 reasons why on their own. However, if one takes a child’s age into account and their developmental stage to

26

explain different topics. This will make them more confident, prepare for the world, knowledgeable, compassionate and strong (Knorr, 2020).

Essentially, it consists of social issues that teens could relate to having to do with everything from school shootings, drugs, alcohol and mental health issues to extreme bullying and sexual violence only to mention a few. These are all not-so-pleasant topics to deal with, but

nevertheless we know it is something students may be drawn to.

5.3.2 Considerations

Instead of watching the drama series as a whole, this lesson plan will consist of shorter sequence of the episodes, capturing parts that may otherwise be avoided in the school setting as the tendency has shown to be focused in positive topics based on the majority of

interviews and online research findings. It will also be in collaboration with Sex Education as the drama heavily consists of topics that are both related to sex and drugs. For students to prepare for the real work, this could be a practice/experience taking place in a safe space giving the students all the tools they need to gain new knowledge. The communication will mainly be in English but the terms that are used will be in connection to their first language as well.

Practically speaking, the time aspect is essential for results and when dealing with social issues, it requires the time it needs. This may differ, depending on the group. It should not simply be “over and done” but thoroughly processed.

Another important aspect is to know one’s students and make wise determinations based off that. The overall preparations are vital to feel confident in the work. Get further educated and collaborate with the biology teacher to get more research-based information that students can discuss and develop further.

27

6. Discussion

The data allowed me to identify patterns and to answer the first research question, I synthesize the interviewees’ responses and compare it to Lgr11 as well as previous research. The second research question, allowed me to draw parallels between the interviews and the netnography findings, also looking at the relevant theories. At last, to answer the third question, I correlate the findings and the previous research forming and leading into a lesson plan.

6.1 English teachers and Lgr11

It seems the material varies depending on who your teacher is. On the one hand, the

interviews suggest that there are similar perceptions of the curriculum among the teachers but on the other hand, Lgr11 emphasizes student influence and based on the findings of this paper, it appears to be lacking where it could be greater. Naturally, this could be related to what Skolverket (2009) point out as one of four contributing factors to the differences in the result gap among students in Sweden referring to “the school’s inner work”.

6.1.1 Social issues in the classroom

Based on the interviews and the netnography data, the English classroom focuses excessively on the popular, comfortable, mostly positive, and light topics. At the same time, social issues that are uncomfortable, oftentimes negative, and heavy, are neglected on a significantly higher number. As interviewee B stated, this could be because it is easier to talk about fun things meanwhile it is hard talking about topics such as racism and these subjects should not be treated lightly by teachers. Another aspect to take into account is the time aspect where difficult topics could require more time to get in depth of social issues to avoid shallow content leaving students feeling bland as Interviewee D suggests. Also, as interviewees expressed, lighter topics make a pleasant atmosphere and a more comfortable learning experience, with little risks.

Topics like sexual orientation, abortion, depression, or sexual violence were excluded from the lesson plan, as “students most likely wouldn’t be able to handle it”, based on their maturity level according to interviewee A and C. Perhaps this indicates Freire’s (1970/2017) claims that

28

a lack of confidence in “people’s ability to think, want and to know” could be rather accurate in practice in fears of the result as the interviews suggest. However, interviewee B and D believe a teacher could probably talk about most things with students if it is done in a sensible way, designing the content based on the group.

Furthermore, Kramsh (2010) states language is a guide to social reality, where social issues are a real part of everyday life. In connection, participant 1 states, our responsibility to develop students’ capacity of thinking and understanding of others,

As many of the comments in the forum suggested, there were a great deal of teachers looking for new material and ways seeking guidance, some expressing a desire to work with sensitive topics but also, expressing a concern in “how” to go about it practically speaking.

6.1.2 Lesson plan for CLIL implementation

The dual focused learning experience should feel meaningful to the students and to reach that point, students need to contribute in the teaching plan, participate in it and process information through their own existential experience and through interaction (Coyle, Hood & Marsh, 2010) and as Paul and Elder (2007) state, “in this new world where change is rapid and intense, critical thinking is required for economic and social survival”.

With the work of CLIL, there are countless helpful models teachers can use such as the CIT analysis, for reflection and discussion simultaneously being practised by students or educators and researchers (Coyle, Hood & Marsh, 2010). Reflection and re-examination of oneself is important when interacting with others, allowing one to develop further (Coyle, Hood & Marsh, 2010). The formed lesson plan (see Appendix D) based on the findings is primarily focused on social issues in the L2 classroom staying in accordance with the teachings of CLIL.

The aim of working with consent and sexual violence is for students to understand what they

may never discuss in depth in their process of conceptualizing the world in a safe space as teens. Without in-depth discussions and reflections of any topic, little to no new knowledge can be acquired on the matter, especially with topics that are being neglected.

CLIL is flexible and has a variety of methods one can implement to suit the agenda depending on the content and the circumstances. The teachers interviewed had different experiences with content and language integration, the first expressing subject a great experience with CLIL as a method meanwhile interviewee C mentioned theme work was highly appreciated instead of

29

text books because of CLIL and its theories, which was taught in teacher education. Interviewee D also utilizes history into English, combining the two although it was unclear if it was based on CLIL or simply integrating the subjects subconsciously.

The neglected topics I am referring to are related to the netnographic research section of this study, sexual issues being one of them. To add, only based on the interviews alone, most topics that were avoided – for different reasons – all had to do with sex in some way, whether it was sexual preferences or sex crimes. In connection to Hooks (1994) describes how teachers may not take the uncomfortable path when one could simply take the comfortable path, choosing the safe approach, introducing a subject in a predictable way with limited amounts of sources, due to fear emulating potentially resulting in the old model of teaching being used to an extent. Our whole concept of education serves to prepare our students to become independent and capable citizens of the world. Yet, this basic yet essential part of human experience may only be put into teens’ educational context no more than once, taking place in sex education. At a time when teens go through hormonal and physical changes and at different stages, sexuality is a topic that is rarely talked about in subjects other than Sex Education which roughly covers 15-20 hours throughout the three school years (Skolverket>timplan, 2019). This alone is no indicator that issues related to sex are talked about in Sex Education as content and what teachers emphasize in the education varies.

All in all, the consideration and aim are to prepare students for the real world as well as focusing on the content being ‘factual, conceptual, procedural and metacognitive’ (Anderson & Krathwoll, 2001) to reach a higher learning

Striving towards being a facilitator (Freire, 1970/2017) the content used for this project is mainly picked on the basis of it being a popular and relevant for teens, giving the drama a high level of relevance in the l2 classroom inviting discussion to take place perhaps motivating the students to partake making it natural as it is something they themselves have invested their free-time on. As the drama deals with social issues related to teens in alternative ways, the intention is to let students partake in the choice-making which is in support of Lgr11.

With reference to Freire (1970/2017), rather than “giving” what a teacher may consider to be valuable knowledge to the students, the activities in place are intended to develop their critical consciousness through diving deeper into issues which requires differences of opinions and an exchange of voices focusing on the knowledge the students put forth.

30

The link provided in the lesson plan, I am a survivor, is meant to give students the tools that would long-term result in intervening in the world as transformers (Freire, 1970/2017), through awareness reflection on “life conditions and societal questions and cultural phenomenon in different contexts” (Lgr11)

To gain new knowledge however, students must be allowed to develop their vocabulary further by introducing new words and terms relevant to their field of subject, which will differ depending on the student in question age and level of English being two aspects to take into account. This is essential when working with CLIL (Coyle, Hood & Marsh, 2010) for students to get any meaningful input throughout the process. CLIL (ibid) introduces the implementation of familiar language and new language, starting off with no cognitive challenge to get students comfortable and in tune with what is about to take place.

Additionally, the vocabulary and phrases that are used are all related to the context that is of focus which will be heard and contextualized intensively before students feel confident to put the words and phrases to use. The more active the students are in the tasks given, highlighting differences of opinions, the more is the teacher’s trust in their ability to think for themselves (Rogers, 1983).

For the monitoring of the “self” in terms of prior knowledge, sharing unit objectives including acquired knowledge, for the student as well as the teacher to reflect on, the KWL chart is used to concretize for the individual in question of the development stages before, during and after the project. The KWL chart involves asking what one knows, want to know, and what has been

31

7. Conclusion

The world is changing rapidly and to create functioning and independent citizens, we need to reflect on our ways of teaching. This study contributes to the field of ESL and CLIL through the examining of how we discuss social issues in the L2 classroom under the guidelines of

Lgr11. The data suggests teachers agree on the perceptions of Lgr11 and the management of

the English curriculum, creating similar tasks. However, the difference lies in the selection of topics and how active students are in the development of lesson planning. Students may therefore acquire knowledge in different ways and what this knowledge consists of may also differ.

The data findings online reveal that many of the topics that are included in the classroom, consist of more than merely language as there is a subject behind it. This gives way for CLIL to be a natural part of the setting. Whichever topic one deals with, it requires that the student knows how to go about a group discussion or other forms of activities but in CLIL, this cannot be taken for granted. Similarly to how students develop knowledge and skills, they also have to learn the method in which they are practicing. CLIL is not used as widely as it could be, keeping in mind how teachers are encouraged to integrate content into language learning. This could be an indication that CLIL could be a revolutionary method that needs to be tried out and perhaps it would help develop the ways of teaching, creating a structure that could become the standard for teachers in all of Sweden.

The contribution of a student-perspective would bring out a different angle to the study. However, this proved to be impractical due to the covid-19 crisis where there was limited access to schools. In addition, not being able to fulfil the action research by executing the lesson plan through a field study raises questions that remain unexplored, due to no implementation and evaluation.

For this small-scale study takes a limited look into the current language learning experience, the intention is to see if the findings can be confirmed in the actual classrooms including students take on it. Furthermore, the implementation of CLIL using the designed lesson plan to see what the outcome would be is also an approach that would be compelling to take.

32

8. References

Adams, C.W. (2015) Handbook of practical Program Evaluation (4th ed). Jossey Bass: San Francisco.

Bassey, M. (1998) Action Research for improving educational practice in Halsall, R. (ed). Teacher research and school improvement: Opening doors from the inside. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Bell, J. (1999) A guide for first-time researchers in education and social science. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Bruton, A. (2013) CLIL: Some of the reasons why and why not. Sevilla:Elsevier vol4:3.

Cameron, D. (2001) Working with Spoken Discourse. Oxford:Sage.

Coyle, D, Hood, F & Marsh, D. (2010) CLIL:Content and Language Integrated Learning.

Coyle D. (2002) Relevance of CLIL to the European Commission Language Learning. Vancouver:Public Services Contract.

Dr Bhushan M, Dr Alok S. (2017) Handbook of research methodology. Edu Creation publishing: New Dehli.

Fredriksson, P, Westerholm, A. (2018) Ny kunskapssyn avgörande för Sveriges framtid. Retrieved from: https://www.svd.se/ny-kunskapssyn-avgorande-for-sveriges-framtid

Freire, P. (2017). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York:Bloomsbury Publishing Inc. (Original work published 1970).

Gadotti, Moacir. (1996) Pedagogy of Praxis: a Dialectal Philosophy of Education. Albany: State University of New York Press.

General Teaching Council for Wales (GTCW). (2002) Professional development and entitlement for all. Cardiff: GTCW.

33

Giroux, Henry A. (2004). Critical Pedagogy and the Postmodern/Modern Divide: Towards a Pedagogy of Democratization. Teacher Education Quarterly. P.31-45.

Harden R.M. & Crosby J. (2000). AMEE Guide No 20: The good teacher is more than a lecturer-the twelve roles of the teacher. Medical teacher. 22(4) p.334-347.

Heale, R & Forbes, D. (2013) Understanding triangulation in research.

Hooks, B. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. London: Routledge

Internetstiftelsen. (2017). Barn och internet. Retrieved from:

https://svenskarnaochinternet.se/rapporter/svenskarna-och-internet-2017/barn-och-internet/

Internetstiftelsen. (2018) Barn och internet. Retrieved from:

https://svenskarnaochinternet.se/rapporter/svenskarna-och-internet-2018/barn-och-internet/

Johansson E, Emilson A, Maija Puroila, A. (2018) Values Education in Early Childhood Settings: concepts, approaches and practices. Kalmar:Springer.

Kember, D. (1997). A reconceptualization of the research into university academic conceptions of teaching. Learning and instruction. P.255-275.

Kozinets, R.V. (2015) Netnography: Understanding Networked Communication Society. Sage: Toronto.

Kozinets, R.V. (2015). Netnography redefined. Sage: London.

Knorr, Caroline. (2020). How to talk to kids about difficult topics. Retrieved from:

https://www.commonsensemedia.org/blog/how-to-talk-to-kids-about-difficult-subjects

Kramsch, C. (2010) Language and culture. University Press: Oxford.

Läroplanskommittén. (2014). Ur KB:s samlingar, Retrieved from: https://www.svd.se/ny-kunskapssyn-avgorande-for-sveriges-framtid