BACHELOR THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Sustainable Enterprise Development AUTHOR: Elin Hernelind and Freja Hogréus

JÖNKÖPING May 2020

Readiness for

Change Towards

Sustainability

A Study of Swedish Companies: Change Agent and

Employee Perspectives

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, we would like to sincerely thank our tutor, Ulla Saari, for being such a rock in the process of completing this thesis. Her guidance, support and insights proved extremely valuable throughout the project.

Secondly, we want to express our gratitude to the companies and organizational members who participated in this study despite these dire times. Their genuine enthusiasm and willingness to contribute were much appreciated.

Jönköping, 18th of May

____________________ ____________________

Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Readiness for Change Towards Sustainability: A Study of Swedish Companies: Change Agent and Employee Perspectives

Authors: Elin Hernelind and Freja Hogréus Tutor: Ulla Saari

Date: 2020-05-18

Key terms: Change readiness, Change agent, Employee, Sustainability, Business

Abstract

Background: There is an increasing importance of sustainable development in today’s

society as a result of various social, environmental, and economic challenges facing the people and planet. To create the change needed to shift from unsustainable activities, everyone must participate, including business organizations. Here, the concept of change readiness is highly relevant as it helps prepare individuals and organizations to accept and not be resistant to change initiatives.

Purpose: The purpose of this thesis is to investigate and explore (1) how change agents

create change readiness to prepare employees for organizational change towards sustainability and (2) how these efforts are perceived and experienced by employees.

Method: This thesis uses a qualitative approach with an exploratory nature where two

companies (case studies) are included. In total, five organizational members were interviewed to collect empirical data: two change agents and three employees.

Conclusion: The findings display that change agents use two strategies for spreading the

change message (persuasive communication and active participation) and unintentionally use the five cognitive components of change readiness (discrepancy, appropriateness, efficacy, principal support and personal valence) to prepare employees for organizational change towards sustainability. In turn, these efforts are perceived and experienced by employees as enhancing their level of change readiness.

Table of Contents

Glossary ... 1

1. Introduction ... 2

1.1 Background ... 2

1.1.1 Social and Environmental Challenges ... 2

1.1.2 Sustainable Development and Business ... 2

1.1.3 The Risk of Resistance ... 3

1.2 Problem Discussion ... 4

1.3 Purpose of the Research and Research Questions ... 5

1.4 Delimitations ... 5

2. Theoretical Framework ... 6

2.1 Corporate Sustainability ... 6 2.2 Organizational Change ... 6 2.2.1 Transformational Leadership... 7 2.3 Change Readiness ... 72.4 Individual Readiness to Change ... 8

2.4.1 Affective Change Readiness... 9

2.4.2 Cognitive Change Readiness and the Five Components ... 9

2.4.2.1 Discrepancy... 10

2.4.2.2 Efficacy ... 10

2.4.2.3 Appropriateness ... 10

2.4.2.4 Principal Support ... 10

2.4.2.5 Personal Valence ... 11

2.4.3 Antecedents on the Individual Level ... 11

2.5 Group and Organizational Readiness to Change ... 12

2.5.1 Antecedents on the Group and Organizational Level... 12

2.6 Trust Building ... 13

2.7 Fairness ... 13

2.8 Resistance to Change ... 14

2.9 Creating Buy-In and Getting Others on Board ... 14

2.10 Employee Satisfaction ... 15

2.11 Communicating the Change Message ... 15

2.11.1 Persuasive Communication ... 16

2.11.2 Active Participation ... 16

2.11.3 External Communication ... 17

2.12 Assessment ... 17

2.13 Summary of Theoretical Framework... 18

3. Methodology and Method ... 19

3.1 Research Philosophy ... 19 3.2 Research Purpose ... 20 3.3 Research Approach ... 20 3.4 Research Design ... 21 3.4.1 Case Studies ... 21 3.5 Selection Process ... 22 3.5.1 Companies ... 22

3.5.2 Interviewees ... 22

3.6 Primary Data Collection ... 23

3.7 Secondary Data Collection ... 25

3.8 Data Analysis ... 26

3.9 Ethical Considerations ... 27

4. Empirical Findings ... 29

4.1 Attitudes Towards Change for Sustainability ... 29

4.1.1 Change Agent Perspective ... 29

4.1.2 Employee Perspective ... 30

4.2 Type of Change ... 30

4.2.1 Change Agent Perspective ... 30

4.2.2 Employee Perspective ... 30

4.3 Business Strategy ... 31

4.3.1 Change Agent Perspective ... 31

4.3.2 Employee Perspective ... 31

4.4 Cognitive Change Readiness and the Five Components ... 32

4.4.1 Discrepancy and Appropriateness ... 32

4.4.1.1 Change Agent Perspective ... 32

4.4.1.2 Employee Perspective ... 32

4.4.2 Efficacy ... 33

4.4.2.1 Change Agent Perspective ... 33

4.4.2.2 Employee Perspective ... 33

4.4.3 Principal Support ... 34

4.4.3.1 Change Agent Perspective ... 34

4.4.3.2 Employee Perspective ... 35

4.4.4 Personal Valence and the Affective Component ... 35

4.4.4.1 Change Agent Perspective ... 35

4.4.4.2 Employee Perspective ... 36

4.5 Strategies for Delivering the Change Message ... 36

4.5.1 Persuasive Communication ... 36

4.5.1.1 Change Agent Perspective ... 36

4.5.1.2 Employee Perspective ... 37

4.5.2 Active Participation ... 38

4.5.2.1 Change Agent Perspective ... 38

4.5.2.2 Employee Perspective ... 39

4.5.3 External Information ... 40

4.6 The Concept of Change Readiness ... 40

4.6.1 Change Agent Perspective ... 40

4.6.2 Employee Perspective ... 40

5. Analysis ... 41

5.1 Attitudes Towards Change for Sustainability ... 41

5.2 Type of Change ... 41

5.3 Business Strategy ... 42

5.4 Cognitive Change Readiness and the Five Components ... 43

5.4.1 Discrepancy and Appropriateness ... 43

5.4.2 Efficacy ... 44

5.4.3 Principal Support ... 46

5.5 Strategies for Delivering the Change Message ... 49

5.5.1 Persuasive Communication ... 49

5.5.2 Active Participation ... 50

5.5.3 External Information ... 51

5.6 The Concept of Change Readiness ... 52

5.7 Deviations from Structure ... 52

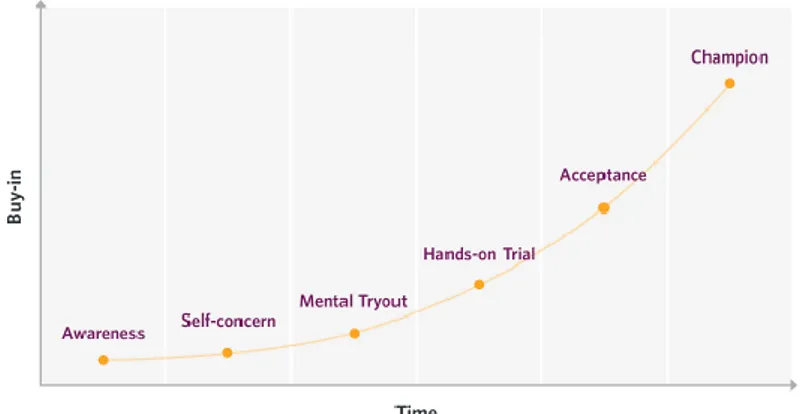

5.7.1 Six Stages of Buy-In ... 52

5.7.2 Education ... 53

6. Conclusion ... 55

7. Discussion ... 58

7.1 Implications ... 58 7.2 Limitations ... 58 7.3 Future Research ... 60References ... 62

Figures ... 69

Figure 1: Creating Buy-in and Acceptance for Change ... 69

Tables ... 70

Table 1: Summary of Interviewees ... 70

Appendices ... 71

Appendix 1: Interview Questions in Swedish and English ... 71

Questions to Change Agents ... 71

Questions to Employees ... 75

Appendix 2: The Distributive Trades Sector ... 78

1

Glossary

Buy-in: “The degree of a change effort’s acceptance by an organization, a unit, or an

individual.” (Raffaelli, 2017, p. 39)

Change: Make or become different (Lexico, 2020).

Change agent: “A group or individual whose purpose is to bring about a change in

existing practices of an organization that have become entrenched routines…” (Law, 2009)

Change readiness: “The cognitive precursor to the behavior of either resistance to, or

support for, a change effort.” (Armenakis, Harris, & Mossholder, 1993, p. 683)

Communication: The imparting or exchanging of information by speaking, writing, or

using some other medium (Lexico, 2020).

Resistance to change: “Reluctance or refusal to accept a change effort. Resistance can

be conscious or subconscious and manifests itself differently at different stages of a change effort.” (Raffaelli, 2017, p. 39)

Sustainable development: "Sustainable development is the development that meets the

needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs." (Brundtland, 1987, p. 41)

2

1. Introduction

This chapter will introduce the urgency of incorporating sustainability in business practices, the risk of failure when implementing change, and change readiness which can help reduce the risk of change initiative failure. A discussion of the research problem, the purpose of the research, and the research questions investigated in this study will also be presented, followed by delimitations.

1.1 Background

1.1.1 Social and Environmental Challenges

In November year 2019, the European Parliament declared climate emergency in Europe and globally (Haahr, 2019). There is a shared belief that the world is changing rapidly, and if continuous changes are not conducted, it will be challenging to keep up. The planet has an increasingly growing population, and the human consumption is causing consequences that not only harm the wellbeing and health of individuals but simultaneously put heavy pressure on the Earth and its ecosystems (United Nations, 2015). Nevertheless, during 2019, humanity consumed resources at a rate of 1.75 times higher than the Earth’s capacity to regenerate itself (Global Footprint Network, 2020). According to the United Nations (2015) and The Royal Society (2012), humanity is faced with the risk of natural disasters, global warming, and pollution, among others, which not only has an impact today but also for future generations.

1.1.2 Sustainable Development and Business

As indicated by many measures, it is apparent that sufficient actions must be taken in order to guarantee a sustainable future (The Royal Society, 2012). Thus, everyone must take responsibility, including business organizations, who are seen as dominant contributors to environmental degradation and unsustainable behaviors (United Nations Global Compact & KPMG, 2016a; Elkington, 1994). Voegtlin and Scherer (2017) explain

3

that the constraints on the Earth’s life-support system require global actors to make concentrated efforts toward sustainable development in order to preserve the planet for future generations. Millar, Hind, and Magala (2012) argue that in order to create the change needed and to shift away from unsustainable activities, the business organizations must participate by having a change of attitude, and thereby a change of business structures.

Brundtland (1987) states that economic growth is crucial, but that it should not be achieved at the cost of the social or environmental sustainability of today and the future. Based on this statement, Elkington (1994) introduced the concept of the triple bottom line, which is the accounting of social, environmental, and economic aspects within business activities. The triple bottom line emphasizes that companies should conduct business in a way that assures long-term economic performance while avoiding activities that are beneficial in the short-term that are environmentally or socially harmful (Porter & Kramer, 2006; Elkington, 1994). This capability is crucial in order to successfully create a transition towards sustainability, as it is highly dependent on the creation and maintenance of virtues such as loyalty and dependability (Elkington, 1994).

1.1.3 The Risk of Resistance

Approximately 70% of organizational change efforts fail due to resistance (Aiken & Keller, 2009; Kotter, 1996; Higgs & Rowland, 2005), which is one of the major barriers that could face change initiatives (Georgalis, Samaratunge, Kimberley & Lu, 2015; Rafferty, Jimmieson & Armenakis, 2013; Oakland & Tanner, 2007). Thus, employee reactions, perceptions, and attitudes to the initiated change play a critical role in the success of a change initiative (Georgalis et al., 2015; Vakola, 2014). Negative attitudes can, for instance, lead to resistance in terms of withdrawal from the change, material sabotage, and strikes, which can result in failed change initiatives (Pieterse, Canieels, & Homan, 2012). Further, it is argued that managing resistance solely leads to increased spending of resources, such as money and time.

4

Cândido and Santos (2015) state that measuring success and failure is difficult, and the definition of them is unclear. Nonetheless, Rafferty et al. (2013) and Armenakis and Harris (2002) describe a change to be successful when the desired end-state is achieved, and they argue that creating change readiness will make it simpler to reach that state. Attitudes and reactions are said to be determined by the level of readiness of an employee before a change initiative are realized, i.e., the change readiness of an employee (Vakola, 2014; Rafferty et al., 2013; Armenakis, Harris & Mossholder, 1993). If employees get to understand and accept the intended change, it is possible to not only avoid resistance but also to create a genuine motivation of the employee to perform and drive the change initiative, resulting in a more successful change process (Rafferty et al., 2013).

1.2 Problem Discussion

Several authors have observed that individuals’ beliefs and perceptions of their organization’s level of readiness have an impact on their acceptance and adaptation to change (Georgalis et al., 2015; Vakola, 2014; Rafferty et al., 2013), making the concept of change readiness interesting and relevant to study. Additionally, the concept of change readiness suffers from incoherency regarding its definition and which components that determine the creation of it, as it has not received any significant academic attention (Rafferty et al., 2013; Vakola, 2013). This study aims to contribute to the current body of literature as it investigates similarities and differences to either strengthen or develop the components of the existing research.

There is an urgency for businesses to change in order to tackle sustainability challenges and to create sustainable development on a global scale (United Nations Global Compact & KPMG, 2016b). However, it is important to bear in mind that the majority of change initiatives fail (Gigliotti, Vardaman, Marshall & Gonzalez, 2019; Georgalis et al., 2015; Rafferty et al., 2013). This can be closely connected to the resistance of employees (Pieterse et al., 2012) in the absence of acceptance to the change (Gigliotti et al., 2019), which means inadequate change readiness (Vakola, 2014; Rafferty et al., 2013; Armenakis et al., 1993). This study is beneficial for anyone, especially for change agents, who wish to successfully undergo or implement a change towards sustainability within a

5

business organization, which has induced urgent and essential challenges for business organizational change.

1.3 Purpose of the Research and Research Questions

The purpose of this thesis is to investigate and explore how change agents create change readiness in order to prepare employees for organizational change towards sustainability. Further, this study explores in what way employees perceive and experience the efforts for creating change readiness. As a result, the research questions discussed and examined were:

• “How do change agents create change readiness in order to prepare employees for organizational change toward sustainability?”

• “How are the change readiness efforts being perceived and experienced by employees?”

1.4 Delimitations

The topic of change readiness is delimited by focusing on sustainability-oriented change due to the current relevance of organizational change towards sustainability. Only companies registered in Sweden, that follow Swedish laws and regulations participated in this study to make sure that all companies have a similar prerequisite from a cultural and geographical perspective.

6

2. Theoretical Framework

This chapter presents the existing literature and relevant theories on the topics of sustainability in businesses, change, change readiness, and communication in which the framework of this study is built upon, including other factors of interest to help answer the thesis’s research questions.

2.1 Corporate Sustainability

External pressure, in the form of regulation and societal awareness, pushes organizations towards the need for change and to conform to corporate sustainability (Millar et al., 2012). Most definitions of corporate sustainability are based on the classical definition by Brundtland on sustainable development. Ashrafi, Magnan, Adams, and Walker (2020) state that one of the earliest and most cited definitions of corporate sustainability is formulated by Dyllick and Hockerts (2002) as “meeting the needs of a firm’s direct and indirect stakeholders (such as shareholders, employees, clients, pressure groups, and communities), without compromising its ability to meet the needs of future stakeholders as well” (p. 131). Another, more recent, example of a definition of corporate sustainability is formulated by Schaltegger, Hansen, and Lüdeke-Freund (2016), who write that a business model for sustainability is one that “helps describing, analyzing, managing, and communicating (i) a company’s sustainable value proposition to its customers, and all other stakeholders, (ii) how it creates and delivers this value, (iii) and how it captures economic value while maintaining or regenerating natural, social, and economic capital beyond its organizational boundaries” (p. 6).

2.2 Organizational Change

Organizational change initiatives are a carefully studied topic, but still, many change initiatives fail (Georgalis et al., 2015; Rafferty et al., 2013). Georgalis et al. (2015) and Vakola (2014), claim that employee resistance is one of the primary reasons for

7

organizational change failure. Armenakis et al. (1993), in accordance with the previously mentioned authors, argue that the resistance is an outcome from negative attitudes and reactions, which may be avoided if a certain level of readiness is established with employees before the implementation of a change.

It is vital to contemplate the type of change and understand the differences between fundamental (or radical) and incremental change. Fundamental changes are usually faced with a greater risk of resistance due to the size and nature of the change initiative and, therefore, require more extensive change messages. The incremental change commonly involves smaller modifications of processes (Rafferty et al., 2013; Armenakis et al., 1993).

2.2.1 Transformational Leadership

Transformational leadership is defined by Bass and Avolio (1997) as a style of leadership that motivates followers by appealing to their needs and introducing them to transcend self-interest for an organization. Furthermore, Men and Stacks (2013) states that transformational leaders seek to empower the followers and that this leader type is willing to share her/his power and assign responsibility and authority to make the followers feel independent. Therefore, personality traits such as interactive, passionate, caring, and empowering, are usually indicators for transformational leaders (Hackman & Johnson, 2004).

2.3 Change Readiness

The term ‘readiness’ can be divided into three different concepts; individual readiness for change, such as an individual’s confidence in hers or his abilities (self-efficacy); perceived organizational readiness for change, such as the confidence in the organization’s ability to manage the change; and the actual organizational readiness for change, which is the organization’s ability to implement the change (Vakola, 2013). Further, groups can have a powerful effect on members’ beliefs, values, and behavior (Rafferty et al., 2013; Vakola, 2013). Therefore, group readiness for change should also

8

be considered, just as individual readiness for change and organizational readiness for change is.

According to Vakola (2013), an issue of concern is that the existing literature on change readiness does not differentiate between individual readiness for change and organizational readiness for change, which creates confusion for both research and practice. Additionally, although groups can have a powerful effect on members’ beliefs, values, and behavior, group readiness to change is somewhat neglected in the existing literature. By neglecting the dynamics between the various levels of readiness, there will be a limit to the theoretical and empirical work concerning change readiness (Rafferty et al., 2013; Vakola, 2013). Therefore, group readiness for change should also be clarified and considered, just as individual readiness for change and organizational readiness for change is.

2.4 Individual Readiness to Change

Individual readiness to change is defined as an individual’s “beliefs, attitudes, and intentions regarding the extent to which changes are needed and the organization’s capacity to successfully undertake those changes” (Armenakis et al., 1993, p. 681). Other definitions for individual readiness to change have been developed from Armenakis et al.’s work. However, the mentioned definition has been the most commonly used one in studies (Rafferty et al., 2013). Crites, Fabringar, and Petty (1994, p. 621) write that attitudes are “evaluative summary judgments that can be derived from qualitatively different types of information (e.g. affective and cognitive).” This means that beliefs about an attitude object or target, and affective responses which consists of discrete, qualitatively different emotions such as; hate, happiness, excitement, acceptance, etc. (Crites et al., 1994), to an attitude object are distinct causes or antecedents of the overall evaluative judgment that is an attitude (Rafferty et al., 2013). Additionally, it is described by Weiner (2009) that negative emotions can have a bad influence on the level of readiness and the confidence of the employees. Hence, individual readiness is based on the interaction of enduring predispositions and responses induced by situations, which are affected by an individual’s affective and cognitive processes, and that the outcome of

9

these will result in either supportive or non-supporting behavior towards the change event (Rafferty et al., 2013; Vakola, 2013; Rafferty & Minbashian, 2019).

Rafferty et al. (2013) further explain that whereas Armenakis et al.’s original definition emphasizes beliefs, it does not address the affective components of change readiness. They also explain that in more recent discussions, affect has broadly become acknowledged as an important component that constructs change readiness. The definition by Holt, Armenakis, Field and Harris (2007, p. 235) takes affect into consideration as well as the definition of Armenakis et al.’s original work and: “the extent to which an individual or individuals are cognitively and emotionally inclined to accept, embrace, and adopt a particular plan to alter the status quo purposefully.”

2.4.1 Affective Change Readiness

As previously mentioned, the definition of individual change readiness by Holt et al. (2007) includes affect. Rafferty et al. (2013) and Rafferty and Minbashian (2019) propose that affective change readiness should be assessed by discrete emotion items that capture a group’s or an individual’s positive emotions regarding a specific change. Additionally, emotions can also emerge from the imagination, which can come to have an impact on the level of readiness for change of a member of an organization. For example, if an employee imagines being promoted as a result of the change initiative, she or he is likely to experience positive emotions in relation to the change. Even if the employee does not get promoted in the end, the positive emotions from assuming so may have a strong effect on the readiness level.

2.4.2 Cognitive Change Readiness and the Five Components

Armenakis et al. (1993) identified two cognitive beliefs as key components of individual change readiness. These are; the belief that change is needed (discrepancy) and the belief that the organization and individual have the capacity to undertake change (self-efficacy). This discussion was later expanded by Armenakis and Harris (2002), who discovered five cognitive beliefs that constitute an individual’s readiness to change. As the other beliefs

10

were added, these five beliefs have become the most popular and frequently used manner to operationalize individual change readiness (Repovš, Drnovšek and Kaše, 2019). The five cognitive beliefs are discrepancy, efficacy, appropriateness, and personal valence (Armenakis and Harris, 2002).

2.4.2.1 Discrepancy

Discrepancy refers to an individual’s perceived need for a change, and if a change is perceived as necessary or not (Armenakis and Harris, 2002). According to Armenakis et al. (2007), a sense of discrepancy emerges from the perceived gap between the current state and the desired state after a change. In contrast, Holt et al. (2007) suggest that discrepancy involves a recognition that change is based on legitimate reasons.

2.4.2.2 Efficacy

Efficacy is defined as an individual’s perceived capacity to implement a change event (Armenakis and Harris, 2002), whereas change self-efficacy is defined as an individual’s confidence that she or he has the capacity to implement a change event (Armenakis and Harris, 2002; Holt et al., 2007).

2.4.2.3 Appropriateness

Appropriateness is an individual’s belief that a change is an appropriate response to organizational issues (Armenakis & Bedeian, 1999), which is recognized by Rafferty and Minbashian (2019) as a commonly used definition in studies within the field.

2.4.2.4 Principal Support

Principal support refers to a range of organizational leaders, including both informal and formal leaders or change agents and opinion leaders, who provide support (Armenakis et al., 2007). In order to successfully undertake the change initiative, individuals need to be convinced that they have the support needed from the organization and managers (Armenakis and Harris, 2002). However, Rafferty and Minbashian (2019) explain that

11

change attitudes and reactions to change can also be influenced by one’s peers, which is why it is important to recognize different sources of support. Based on this, Rafferty and Minbashian (2019) define principal support as an individual’s belief that support is provided by not only formal organizational leaders, such as immediate supervisors and senior leaders, but also by one’s peers.

2.4.2.5 Personal Valence

Valence is defined as an individual’s belief that change has both intrinsic and extrinsic benefits (Armenakis and Harris, 2002). Furthermore, Holt et al. (2007) argue that personal valence refers to an individual’s perceived benefits of a change initiative. Thus, Rafferty and Minbashian (2019) define personal valence as an individual’s belief that the change is beneficial for them personally. In contrast, organizational valence accounts for and captures employees’ perceptions of the benefits that the change initiative will bring the company as a whole.

2.4.3 Antecedents on the Individual Level

Rafferty et al. (2013), Oreg, Vakola, and Armenakis (2011) and Rafferty and Minbashian (2019) identify several potential antecedents of cognitive and affective change readiness at the individual level. For example, the authors discuss that change management processes designed to enhance participation in events of change are associated with positive change attitudes and positive responses to change. When employees participate in decisions related to organizational change, a feeling of empowerment is created, providing them with a sense of control and agency. Also, Rafferty and Griffin (2006) indicate that as the scale of change increases, individuals’ attitudes and responses to the change become more negative.

Personal attitudes, characteristics, and individual difference variables have also been identified as antecedents of individuals’ change attitudes (Holt et al., 2007; Rafferty et al., 2013; Oreg et al., 2011; Rafferty and Minbashian, 2019). Examples of personal characteristics that have been studied include individuals’ values, needs, and personality

12

traits, such as dispositional resistance to change and generalized self-efficacy. It is also implied that employees who display positive traits, such as positive self-concept and risk tolerance, etc., will report more positive beliefs and affective responses to change. This will come to contribute to a positive overall evaluative judgment that an individual is ready for a change event.

2.5 Group and Organizational Readiness to Change

According to Weiner (2009, p. 68), organizational readiness for change refers to “organizational members’ change commitment and self-efficacy to implement organizational change.” Rafferty et al. (2013) and Vakola (2013) propose that a work group’s change readiness and an organization’s change readiness attitude emerge from individuals’ affects and cognitions that become shared through social interaction and that manifests at the collective level, which is the workgroup and organizational readiness for change. Therefore, a work group’s change readiness and an organization’s change readiness are influenced by (1) shared cognitive beliefs among workgroup members or organizational members and that they believe that change is needed, that the workgroup or organization has the capacity to carry out the change successfully, and that the change will derive positives outcomes for the workgroup or organization and by (2) the occurrence of current and future-oriented positive group or organizational emotional responses to an organizational change event.

2.5.1 Antecedents on the Group and Organizational Level

Rafferty et al. (2013) discovered a range of potential antecedents of affective and cognitive change readiness at the workgroup and organizational levels. At the group level, the authors suggest that workgroup leaders who create a clear group-level vision and who display emotional aperture will develop positive group beliefs about change and positive group affective responses to change events, and thereby contributing to a positive overall evaluative judgment that the workgroup is ready for change. It is also mentioned that experiencing work group psychological safety will be positively associated with group change readiness, for example; a group that is characterized by high levels of respect and

13

trust will promote openness for discussion about change events, which in turn will enhance beliefs that change is needed while also increasing the likelihood of the workgroup experiencing positive emotions associated with the change.

When it comes to the organizational level of change readiness, Rafferty et al. (2013) explain that the CEO readiness for change will be positively associated with collective beliefs that a change event is needed, which will also increase the possibility of experiencing positive collective emotions associated with the change event. In turn, this will contribute to a positive overall evaluative judgment that the organization is ready for the change event. Another factor that is positively associated with positive collective beliefs about change, as well as positive collective affective responses to the change, is organizational cultures that are characterized by the acceptance of adaptability and development. Thereby, a positive evaluative judgment regarding an organization’s readiness for change is derived.

2.6 Trust Building

Vakola (2013) explains that one should look at trust-building as a way of achieving readiness and managing change. Trust has been identified as the factor that yields the strongest relationship with change reactions because it was related to high acceptance and willingness to cooperate towards achieving a change initiative. Employees should be involved in organizational processes, decision-making, as this is found to have an impact on the development of trust (Armenakis et al., 1993; Armenakis & Harris, 2002; Vakola, 2013). Furthermore, Men (2014a) explains that employees who are satisfied and content with, trusts, and are committed to an organization tends to promote the business by practicing positive word-of-mouth, and overall view the business as valuable.

2.7 Fairness

Rafferty et al. (2013), Oreg et al. (2011), and Rafferty and Minbashian (2019) recognize that positive employee attitudes towards change in the organization can emerge from participation and information as antecedents of change readiness. Also, some employees

14

may be less likely to resists change if they experience high-quality leader-member exchange relationships as these relationships are notions of fairness and reciprocity (Georgalis et al., 2015).

2.8 Resistance to Change

The term resistance can be defined as the reluctance to accept a change effort. Throughout the years, the definition has evolved in addressing the four dimensions of employee responses to change: behavioral, intentional, affective, and cognitive. The behavioral dimension denotes actual behavior, the intentional dimension is based on the attitudes towards an organizational change, the affective dimension refers to feelings about change, and the cognitive dimension refers to thoughts, beliefs, perceptual responses, and knowledge structures about change (Repovš et al., 2019).

2.9 Creating Buy-In and Getting Others on Board

Raffaelli (2017) writes that resistance usually stems from perceptions of excess stress and stretching on the organization or on specific employees or units. This, in turn, creates opposition to the change initiative and makes buy-in very important but also the most challenging aspect of implementing the change. Therefore, it is important that leaders think carefully about whom to engage, how and when to engage them, and how much effort can be asked of each group. Raffaelli (2017) proposes that there are six stages of acceptance and adoption, which individuals should progress in order to build commitment and buy-in.

15

The first step includes the leader’s need to determine who should be aware of the change. It also includes the determination of who will most likely oppose the change and to see how powerful some individuals are. Then, the change leader should help others understand how the change will matter to them personally. The leader should also give individuals the opportunity to imagine what the change might look like before it happens. This provides a low-risk way of helping individuals experience what lies ahead without having to change their current behaviors. A hands-on-trial is also necessary, and the leader asks individuals to experience a specific change in a low-risk environment. This can be done through piloting. After having experienced the earlier stages, the individual’s acceptance of change will now be determined by them weighing the costs and benefits, and s/he will either accept the change and adapt it or reject the change. The individuals who accept the change may ultimately become champions of the change initiative for others. These individuals have the characteristics of eagerly communicating the benefits to others. However, not all individuals who accept the change will become champions.

2.10 Employee Satisfaction

A satisfying relationship can be defined as a relationship in which “the distribution of rewards is equitable, and the relational rewards outweigh the cost” (Stafford & Canary, 1991, p. 225). Further, as described by Hung (2006), satisfaction can be described as a favorable feeling of another party that can be nurtured through the positive expectation of the relationship. When employees are satisfied and contented, they are more likely to commit in a long-term relationship (Men, 2014a).

2.11 Communicating the Change Message

The change message is a primary instrument in the creation of change readiness (Armenakis et al., 1993; Armenakis & Harris, 2002; Rafferty et al., 2013). A satisfactory content addressing the components, or beliefs, of discrepancy, appropriateness, efficacy, principal support and personal valence must be conveyed through the change message in order to construct a readiness for the planned change (Rafferty et al., 2013; Armenakis & Harris, 2002). It is crucial that the change message includes all of the five beliefs,

16

otherwise, the message spread will be ineffective. However, other strategies to convey the components may be used, and each strategy may not address all five components (Weiner, 2009; Armenakis & Harris, 2002). There exist three types of strategies which can be used to deliver and communicate a change message (Armenakis et al., 1993; Armenakis & Harris, 2002); 1) persuasive communication, which refers to direct communication efforts; 2) active participation that involves people in activities designed to have then learn directly and; 3) external information, which includes the making of accessible and public information. These strategies may be used by change agents to convey the five components of the change message, in order to create change readiness (Armenakis & Harris, 2002).

2.11.1 Persuasive Communication

Persuasive communication can appear in various communication forms, either as live or recorded speeches, written communications such as emails or newsletters, or through annual reports, and the change message is usually directly communicated by the change agent or agents (Armenakis & Harris, 2002). Communication done in person is said to be the most powerful influencer within the Persuasive Communication strategy when it comes to the creation of change readiness. Furthermore, live speeches delivered in person sends indications of urgency, importance, and commitment, especially if delivered by a CEO or manager. Written communications, on the other hand, is not seen as effective as speeches due to the absence of direct feedback opportunity (Armenakis et al., 1993). Neither Armenakis et al. (1993) nor Armenakis & Harris (2002) recognizes any deficiency or disadvantage with this Change Message Strategy, but it is mentioned that some of the communication tools are more influential than others.

2.11.2 Active Participation

The Active Participation Strategy is regarded as the most effective and influential strategy when it comes to the creation of readiness and the delivery of the components, as individuals are encouraged and allowed to participate and discover the message of change themselves (Armenakis & Harris, 2002; Armenakis et al., 1993; Vakola, 2013). When the

17

message, or information, is self-discovered by the individual, a genuine feeling of trust and commitment is produced, and therefore, it is favorable to provide opportunities were members of an organization can discover the five components on their own through active participation (Armenakis et al., 1993; Armenakis & Harris, 2002). Active participation is, in practice, when individuals are welcomed and encouraged to develop strategies and goals, but also to deliver feedback on proposed change initiatives (Holt et al., 2007). It is described by Vakola (2013) that the purpose of this strategy is to establish a sense of ownership of the proposed change, which is supported by Rafferty et al. (2013) that state that participation creates a feeling of control and empowerment for the individual. One disadvantage with this strategy is that, based on the individual’s perceptions of the information received, the result of the participation cannot be assured (Armenakis et al., 1993), and that it is a rather challenging tool to apply (Weiner, 2009).

2.11.3 External Communication

Newspapers, scientific articles, and reports are examples of external information, which can be used to communicate and share relevant messages and information to the members of an organization through an external source (Armenakis et al., 1993). The most significant advantage of this Change Message Strategy is that external information is usually perceived as objective and hence, more trustworthy (Armenakis & Harris, 2002). But, it can be challenging to control what is selected to be reported on by the external media, and how much of the published material that will be read, and by whom (Armenakis et al., 1993).

2.12 Assessment

To determine employees’ readiness level prior to change, assessment is used. The result derived from assessment can be used as guidance in the design of the change message (Armenakis et al., 1993). Armenakis et al. (1993) state that unless the readiness level is acknowledged beforehand, confirmation of whether change readiness is successfully achieved or not, cannot be presented. It is mentioned by Valkola (2013) that assessment can be used to develop profiles of employees, which in turn can help to identify potential

18

resistors and potential carriers of the message. Further, this provides the opportunity to target individuals who might need more education and information delivered in the change message. However, it is recognized by Holt et al. (2007a) that 32 instruments for assessing change readiness exists, but it is emphasized that all instruments have issues with reliability and validity.

2.13 Summary of Theoretical Framework

Corporate sustainability is regarded as when a business works with all three dimensions of the triple bottom line in their daily and long-term activities.

It is evident that the five components and the affective component of change readiness are used to create change readiness, and the components are delivered through different change message strategies. This thesis considers individual readiness as it is created when change is performed.

Furthermore, investigating the assessment of readiness is considered to be beyond the scope of this thesis.

19

3. Methodology and Method

The third chapter introduces the research philosophy, purpose, approach, and design applied in this research. Additionally, it presents the process of data collection and describes the process of data analysis.

3.1 Research Philosophy

There are various distinct assumptions and worldviews, referred to as ‘research philosophies,’ that impacts all parts of business research when implemented. As all choices made throughout the research process are affected by the selected research philosophy, a suitable and relevant collection of assumptions is crucial in order to allow for comprehensible research (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2012).

Under the ontological assumption, one can either undertake an Objectivist or a Subjectivist point of view when conducting business research. The Subjectivist worldview assumes that reality is dependent on people’s perceptions and actions, meaning that there is more than one reality (Saunders et al., 2012; Collis & Hussey, 2014), and it is highly linked with interpretivism (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Interpretivism is the philosophy used in this research as it allows for the collection of rich data in order to establish a deep understanding of the researched topic (Collis & Hussey, 2014). However, engaging in an Interpretivist research, one must be aware of the potential challenge of being able to adopt an emphatic position and not to let own beliefs and values affect and influence the research findings (Saunders et al., 2012). Nevertheless, we believe interpretivism to be suitable as it enables the collection of rich data, as well as allows for the emergence of unexpected findings.

Moreover, this research could have applied a Positivist philosophy that aims to explain generalizations applicable to a whole population (Saunders et al., 2012). However, we argue that employing law-like generalizations to this research’s complexity, involving

20

individuals and their perspectives, can perhaps lead to failure of collecting valuable insights and understandings. Therefore, the Interpretivist philosophy was viewed as more appropriate, as interpretivism allows for generalization from one setting to another similar setting (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

3.2 Research Purpose

According to Collis and Hussey (2014) and Saunders et al. (2012), adopting an exploratory purpose to research is appropriate when there are no or very few earlier studies of the issue (Collis & Hussey, 2014; Saunders et al., 2012), which is true in the case of the concept of change readiness based on the conducted literature review. For this reason, an exploratory purpose was deemed the most suitable for this thesis, and also because we intended to explore how change agents create change readiness within companies and how these efforts are perceived and experienced by employees. Hence, we see the relevance of an exploratory research purpose as we aim to develop a better understanding and stimulate further research on the incoherence of the concept of change readiness. Further, due to the limited literature on the topic of change readiness, exploratory research enables us to be flexible by the cause of unexpected discoveries (Saunders et al., 2012).

3.3 Research Approach

Research can undertake two different approaches: deductive or inductive. The deductive approach involves the testing of developed theory, implying that data should be derived and measured quantitatively. Contrarily, the inductive approach is concerned with the collection of qualitative data to create an understanding of different points of view in order to build theory. Usually when using the inductive approach, first, data is collected to get a deep understanding of a phenomenon and is then analyzed to discover patterns and themes that can build a theory (Collis & Hussey, 2014; Saunders et al., 2012). Since the nature of the findings was not known until the completion of this study, we argue that the latter approach was the most suitable and beneficial for this research as the inductive approach allows for new perspectives and information to be uncovered during the

21

research process (Saunders et al., 2012). Moreover, this research is basic since it was designed to make a contribution to theoretical understanding, not to solve a specific problem (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

3.4 Research Design

Interpretivism is, as stated above, based on the worldview that social reality is subjective (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Closely associated with this research philosophy is qualitative research (Saunders et al., 2012).

Collis and Hussey (2014) write that the application of a qualitative research design is favorable and relevant when the existing literature is inadequate, and where the researchers desire to detect and display patterns and themes. The same authors also explain that a qualitative design of research supports the generation of rich and nuanced perspectives. We believe both statements above to be aligned with the desired outcome of this study. Thus, we preferred to use a qualitative design.

Collis and Hussey (2014) explain that a quantitative design can be applied in Interpretivist research but is mainly connected with the Positivism philosophy. Thereby, as interpretivism was our chosen philosophy, we decided only to use interviews to gather data. Further, we believe that valuable insights and observations can be lost by applying a quantitative design instead of the qualitative design. Thus, the qualitative design was selected as the final design.

3.4.1 Case Studies

Case studies are used to obtain in-depth knowledge about a social phenomenon by allowing researchers to collect insights from real-life settings (Collis & Hussey, 2014). This design has been applied to this study in order to create interesting insights that can contribute to the studied topic of change readiness in the context of sustainability-oriented change. In this study, each case represents a Swedish company.

22

3.5 Selection Process

3.5.1 Companies

Non-probability sampling was the sampling method applied to this study, meaning that, according to Saunders et al. (2012), the selected sample is particularly suitable for the topic of research. Probability sampling, on the other hand, means that all elements should have the same chance of being selected (Saunders et al., 2012). Further, in the selected sampling method of non-probability sampling, no rules stand when determining a suitable sample (Saunders et al., 2012). Due to the lack of guidance in regards to selecting a sample, we could select a sample that was regarded as appropriate in relation to the research questions.

In order to be part of the sample, an element – company – must be registered in Sweden. The company must also undergo a change towards becoming more sustainable. The sustainability changes taken in each company do not have to be the same across all elements. What mattered was that each company in the sample is involved in change towards more sustainable actions.

A brainstorming session was initiated to identify suitable elements for the research. This resulted in 15 companies being contacted and asked, by email or phone, to partake in the study. Initially, five companies accepted our proposition to be a part of the study. However, due to the unforeseen consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic, three of these companies declined, and only two companies were still willing to participate. Two new companies were contacted, but they also declined for the same reason as mentioned above. This resulted in two final companies being part of the research sample, both operating in the distributive trades sector (see Appendix 2). Thus, two company cases were included in this study.

3.5.2 Interviewees

When having decided on the companies suitable for the sample, it was time to find relevant organizational members to interview. In order to answer our research questions,

23

we needed both change agents and employees from each company to partake in the research.

First, the persons contacted were those who we believe have the resources and power to lead change, and who are acting as change agents for sustainability actions in their respective companies. One potential change agent from each company was contacted to be interviewed, and it was confirmed that they matched with the described profile. Thus, non-probability sampling was used, resulting in two change agents partaking in the study.

Further, through the initial contact with the two change agents, snowball sampling was used to find interviewees who are below the change agents and are organizational members who are somehow affected by, or included in the sustainability change. Snowball sampling is used when researchers contact the ‘first few’ subjects or samples with the intention to be recommended other subjects (Hussey & Collis, 2014). The change agents did so by contacting employees that they believe fit the presented criteria. In the end, three employees showed interest in partaking in the study, resulting in the participation of one employee from one company and two employees from the other company. Hence, three employees below the change agents were included in this study.

Henceforth, the organizational members leading the change for sustainability are referred to as ‘change agents’, and the organizational members below the change agents are simply referred to as ‘employees’.

3.6 Primary Data Collection

The primary data was collected through interviews. Semi-structured interviews were used, where questions had been prepared in advance. Semi-structured interviews are essential when it comes to the comprehension of the reasons behind decisions made by individuals, their opinions, and attitudes (Saunders et al., 2014). Additionally, semi-structured interviews allow for the development of questions during the interview session (Collis & Hussey, 2014), which can generate important insights and findings within areas not previously considered (Saunders et al., 2012). The intended outcome of using

semi-24

structured interviews was to encourage the participants to openly and freely discuss around the creation, perceptions and experiences of change readiness.

The interview questions were open-ended and based upon the developed theoretical framework. This, in order to allow for the discovery of potential links and resemblances, upon which conclusions later could be drawn. Two different sets of prepared interview questions were created, one adapted to the change agents, and one for the employees (see Appendix 1). Not all of the prepared questions were asked during each interview, either because the interviewee provided sufficient and relevant information when answering another question, or because we felt as if the question was not relevant in the direction of where the interview was heading. Further, new questions emerged during the course of the interview with the purpose of clarification or encouragement of elaboration.

All interviews were conducted in Swedish as all the participants (including us) speak Swedish as the native language. We believe that by using Swedish, more profound and elaborated answers from the participants were generated since there were no language barriers. It was also reasoned that using native language would create a more comfortable setting for the participants.

Interviews were conducted both in-person and via video calls. We preferred that the interviews were made two-on-one, on a face-to-face basis in order to help avoid biased interpretations and to further strengthen the validity of the data (Collis & Hussey, 2014). All the interviews lasted between 35-65 minutes, and they were audio-recorded and later transcribed.

According to Saunders et al. (2012), the way of interaction with the interviewees and the way of asking questions impact the collectible data. This was carried in mind while conducting the interviews and we tried to avoid asking leading questions and also tried not to influence the questions with personal beliefs. Further, Collis and Hussey (2014) explain that answers provided by interviewees can be influenced by how they believe the interviewers expect them to answer, and as a consequence, the participants may not express their true personal opinions as these might be seen as unacceptable ways of

25

answering. To tackle this obstacle, follow-up questions were used in order to increase the depth and understanding of some answers. We also used probes to verify our interpretations.

3.7 Secondary Data Collection

Preceding this research, a literature review on the topic of change readiness was conducted. The revision revealed that it is crucial to create readiness for change in order to undergo a successful change. In the literature review, the search for articles initially started with a keyword search on ”change readiness”, ”organizational change”, ”individual change”, ”change failure” and ”resistance to change”.

The articles revised under the literature review laid the foundation of the theoretical framework of the thesis. The vast majority of the articles were discovered by our initial search of the keywords mentioned above, but many articles were also discovered as they were used as references in the initially reviewed articles. Thereafter, a more extensive keyword search was conducted and included “individual readiness”, “organizational readiness”, et cetera., which helped us get a deeper understanding of the concept of change readiness as a whole. Moreover, it was necessary to obtain knowledge regarding sustainability and business, so the keywords “sustainability”, “sustainable development” and (“sustainab*” AND “business”) were used. Moreover, when combining “change readiness” and “sustainability” no relevant literature was discovered. Lastly, a search for articles including keywords such as “communication” and “change communication” was initiated in order to find articles containing relevant and applicable theories and concepts concerning communication in the context of change. Databases such as Primo, Scopus, and Google Scholar were employed as search engines for the literature search.

The article search was delimited to the year of publication, starting with a time span of 2015-2020. However, during the state of review, it became evident that highly relevant articles older than five years existed. Thus, literature published before the time span was accepted, as these articles discussed classical concepts and theories needed for a more comprehensive understanding and foundation of this research. Therefore, this

26

delimitation was removed. The journals mainly used for the literature search were Journal

of Change Management and Journal of Organizational Change Management.

Reports and websites belonging to multiple non-governmental organizations were also reviewed. For instance, sustainability reports by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Other websites were also used to gain relevant information, but this type of source was used sparingly and with caution. Only highly reliable websites, such as Lexico.com and the United Nations’s website, were used to retrieve newly updated data concerning definitions and sustainability.

3.8 Data Analysis

This thesis was concerned with the collection of primary qualitative data to create an understanding of different points of view in order to build theory, and so, an inductive analysis approach was used. It is stated by Thomas (2006) that an inductive analysis is an approach that primarily uses detailed evaluations of raw data to derive themes, concepts or models through interpretations made by the researcher from raw data.

We used Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six step-by-step guide to a thematic analysis as an inductive approach to analyze the raw data. It is argued by Braun and Clarke (2006) that thematic analysis is the foundation in the analysis of qualitative data and that the usage of these six steps will result in a final thesis that presents both trustworthy and rich finings.

The first step of Braun and Clarke’s step-by-step guide is known as familiarizing oneself with the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). This was done by going through and reading the interview transcripts carefully, and also several times, in order to let the contents sink in.

The second step was executed by connecting the relevant data with similar meaning, also referred to by Braun and Clarke (2006) as; generating initial codes. Codes were created by going through the transcripts over and over again, where raw data were extracted that supported the creation of relevant codes in order to make the codes more transparent and sensible. Since all transcripts are in Swedish, relevant quotes were translated into English.

27

All codes were plotted out in a table upon their completion. Both during the first and the second step of the thematic analysis, we analyzed the data individually in order to reduce the risk of influencing each other.

The third step is about searching for and create themes (Braun & Clarke, 2006). During this step, we came together for the first time to compare and discuss our findings. The process to develop themes included the categorization of codes. This was done by using different colors to highlight codes, in the sense that all codes that related to each other and had similar meanings were highlighted with the same color. The codes in the same colors later came to represent one overarching theme.

Consecutive, the fourth stage of reviewing the themes is about ensuring that the classified data is clear and to make sure that distinct boundaries exist between the themes (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Here, it was recognized that some of the initial themes were too similar and had similar codes, which resulted in them being combined. Then, we concluded that all themes were coherent since all codes under one theme clearly represented their theme.

The fifth step concerns the definition and naming of the themes and is about guaranteeing that each theme is capturing significant data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). After the fourth step, we felt confident about what the final themes should be.

The sixth and final step is about producing the finalized results in the thesis, including the themes and the analysis of them (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The generated themes are the headings presented in the next chapter: 4. Empirical Findings.

3.9 Ethical Considerations

For research involving people and businesses, it is of high importance to be aware of ethical considerations, both during the research process and after (Saunders et al., 2012). Therefore, we promised confidentiality and anonymity to all participants, for the individuals and the companies, in order to reduce the endangerment of identification and connection to thoughts and experiences. Furthermore, it was clearly communicated to the

28

participants that this study would only be published after their approval of the content in the finalized version.

Moreover, to ensure the interviewees’ comfort, they were informed at the beginning of each interview that they were free to end the interview at any point. They were also given a choice of having the interviews being audio recorded or not. All interviewees agreed to be recorded and were then ensured that the recordings and transcripts would only be reviewed by our tutor and us and that they will be discarded directly after the completion of the thesis.

29

4. Empirical Findings

This study aims to explore how change agents create change readiness and how employees perceive these efforts. To scrutinize this, interviews were conducted. All relevant findings from the primary data collection process will be presented in this chapter. To create a clear structure, the findings are structured in accordance with the components and strategies presented in the theoretical framework, and the change agent perspective and employee perspective will be separated.

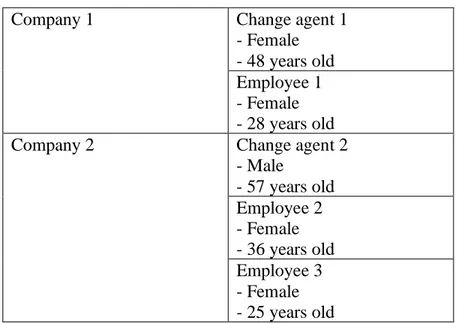

In the table below is a summary of the interviewees. This table will make it easier to understand which interviewee said what in this chapter.

Company 1 Change agent 1

- Female - 48 years old Employee 1 - Female - 28 years old

Company 2 Change agent 2

- Male - 57 years old Employee 2 - Female - 36 years old Employee 3 - Female - 25 years old

Table 1: Summary of Interviewees

4.1 Attitudes Towards Change for Sustainability

4.1.1 Change Agent Perspective

Both change agents described that there had been an increase in demand from customers for more sustainable products. Further, acting sustainably makes both change agents feel

30

happy, and change agent 2 explicitly expressed feeling high satisfaction. Both change agents experienced employee receptivity as high regarding change related to sustainability and mentioned that employee reactions have been positive.

4.1.2 Employee Perspective

Employee 1 thinks it is good for the world to work with sustainability and employee 2 and 3 recognize the benefits for society and the company due to trends, higher customer demand and competition. Employee 1 stated that feelings such as happiness and pride are experienced when the company acts in the interest of society. She also views such actions as strengthening the company and especially the corporate culture. All employees explained that change based on sustainability results in increased motivation and satisfaction.

4.2 Type of Change

4.2.1 Change Agent Perspective

Both change agents described how an entire company must change in order to incorporate sustainability into the foundation of all operations, and one of them, change agent 2, clearly stated the necessity to change the core of the company towards sustainability radically. Further, change agent 1 mentioned that the development of a clear sustainability vision and strategy is a work in progress, and emphasized the importance of achieving small successes in terms of low-hanging fruit.

4.2.2 Employee Perspective

Employee 1 explained that when the change towards sustainability was presented, an increase in organizational efforts towards sustainability was experienced. It was mentioned by employee 2 that a change in the utilization of, and attention given to sustainability has been experienced over the last years. Employee 2 and 3 recognize sustainability as an ongoing process. On the other hand, employee 1 did not mention any

31

specific sustainability strategy, however, explained how she has noticed small changes being implemented step-by-step.

4.3 Business Strategy

4.3.1 Change Agent Perspective

Change agent 1 stated that it is crucial to incorporate a sustainability mindset into the core strategy and that it cannot be treated as a separate component. It was further stated that the sustainability question is taken seriously and is a natural part of the strategical work even though the sustainability strategy is not yet fully completed. Change agent 2 explained that sustainability should always be the foundation for all activities and operations.

Both change agents recognized a clear strategy as a vital component to promote change readiness since it can deliver the message regarding how and why. Further, it was emphasized by change agent 2 that a sustainability mindset should be part of the corporate culture as it can send powerful messages to all stakeholders.

4.3.2 Employee Perspective

All employees believe that sustainability should be a central part of companies’ operations. It was described by employee 1 that the incorporation of sustainability has increased lately and that sustainability questions are now considered during all meetings, which has not been the case before. Employee 2 and 3 described sustainability as a natural element in operations, however, employee 2 explicitly stated that there is still room for further improvements as the world keeps changing.

32

4.4 Cognitive Change Readiness and the Five Components

4.4.1 Discrepancy and Appropriateness

4.4.1.1 Change Agent Perspective

Change agent 2 stated that in order to get employees on board, it is important for them to understand why a change towards sustainability is necessary, why the change is desired, what will change in every-day work, why certain activities need to be undertaken, and why the change is important to the organization as well as each individual. According to change agent 1, information about why the change is necessary and beneficial to the company, as well as to each employee, is important to communicate to get employees on board and avoid resistance. Both change agents also mentioned the relevance of up-to-date information to create a sense of urgency. Change agent 1 explained that no major resistance or negative attitudes have yet been encountered. Change agent 2 emphasized the importance of sharing information when dealing with people that are resistant to change because they are uncomfortable with change in general

4.4.1.2 Employee Perspective

All employees understand that change for sustainability is either good for the world and society, and they see personal benefits by pursuing sustainability, in the sense that they experience feelings of satisfaction and pride.

All employees feel well-informed about the change for sustainability. The reasoning for why the change was initiated, purpose and the implications the change has on everyone’s work tasks was communicated, which create a sense of comfort. Employee 1 stated that this information is also necessary to allow her to feel proud of the company’s work with sustainability. In order to feel comfortable, she prefers clear instructions so that one does not have to speculate about what will happen and she wants to be informed in advance if the change affects her directly.

Employee 1 mentioned that she has not been resistant to the change but recognizes that other employees are. She described how lights were changed to more sustainable lights