The Impact of

the EU

Taxonomy on

Greenwashing

BACHELOR PROJECT

THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15

PROGRAM OF STUDY: Sustainable Enterprise Development

AUTHORS: Sofia Lentfer, Lison Mavon, and Sofia Anna Ilona Stenberg

JÖNKÖPING May 2021

i

Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration

Title: The Impact of the EU Taxonomy on Greenwashing - with a Case on the Swedish Sustainable Finance Sector

Authors: Sofia Lentfer, Lison Mavon & Sofia Anna Ilona Stenberg Tutor: MaxMikael Wilder Björling

Date: 2021-05-24

Key terms: Greenwashing, EU Taxonomy, Investors, Sustainable Financial Sector

Abstract

Background: The trend in environmental reporting has been continuously increasing.

However, there is a lack of accepted uniform standards for accreditation, standardization, and evaluation of green investments, which slows down the process of mobilizing capital to meet sustainability objectives. In response to this, the European Union has created, in summer 2019, a new Taxonomy Regulation in an effort to increase green investing.

Purpose: Skepticism towards green organizations is on the rise and the phenomenon, namely

greenwashing, can be argued to be one of the biggest threats to sustainable development. Previous research on greenwashing has so far only looked at the effects it has on consumers. This study identifies this research gap and alternatively investigates the perspective of the investors on greenwashing. Prior to the EU Taxonomy, there were limited regulations in place to ensure a universal measurement of sustainable actions that were mandatory. This raises the question of whether the EU Taxonomy truly has the potential to reduce greenwashing or not. A descriptive investigation of the current literature on problems of greenwashing within the financial sector can seek to identify the critical themes concerning the EU Taxonomy. Construct a framework on which the EU Taxonomy may be most effective in reducing the types of greenwashing.

Research Question: What is the potential of the new EU Taxonomy to increase transparency

within the sustainable financial sector that is threatened by greenwashing?

Method: Qualitative study; exploratory case study approach; the paradigm of interpretivism as

our research philosophy; interviews based on the inductive approach, semi-structured interviews with a mix of open- and close-ended questions; purposive sampling method; triangulation data analysis with findings visualized in a tree diagram.

Conclusion: A framework is presented that identifies the high/moderate/low potentials of the

EU Taxonomy decreasing greenwashing in the financial sector. Our findings conclude that the EU Taxonomy showed great potential in giving a more comprehensive understanding of the company’s sustainable actions. The development of our findings contributes to a better current understanding of the threats of greenwashing for investors and can help to increase their confidence in sustainable investing.

ii

Table of Contents

1.

Introduction ... 1

1.1Background ... 1 1.2Problem ... 2 1.3Purpose ... 4 1.4Perspective ... 4 1.5Delimitation ... 42.

Frame of Reference ... 5

2.1 Method ... 5 2.2 Greenwashing ... 62.2.1 History of the greenwashing phenomenon ... 6

2.2.2 Drivers of Greenwashing ... 7

2.2.3 Types of Greenwashing ... 10

2.2.4 Greenwashing in the Financial Sector ... 14

2.3 Financial Sector ... 15

2.3.1 Sustainable Finance ... 15

2.3.2 How Investors Evaluate Companies for Sustainable Investments ... 16

2.3.3 Company and Investor Relations ... 18

2.3.4 Lack of Regulation in Sustainable Financial Sector... 19

2.4 EU Taxonomy Regulation... 20

2.4.1 What is the EU Taxonomy? ... 20

2.4.2 Need for the EU Taxonomy ... 22

2.5 Summary of Frame of Reference ... 23

2.5.1 Our Suggested Types of Greenwashing ... 24

3. Methodology ... 27

3.1 Case Selection ... 27 3.2 Research Philosophy ... 28 3.3 Data Collection... 28 3.4 Data Sampling ... 30 3.5 Data Analysis ... 31 3.6 Ethical Considerations ... 324. Empirical Findings & Analysis ... 34

4.1 Complexity of Sustainability ... 35

4.2 Lack of Education on Sustainability and the Impacts of Greenwashing .... 37

4.3 Better Data Transparency with EU Taxonomy ... 38

4.4 EU Taxonomy Criticism ... 41

4.5 Future Challenges... 42

4.6 Evaluation of Suggested Framework ... 43

5. Conclusion ... 49

6. Discussion ... 51

6.1 Implications ... 51 6.2 Limitations ... 52 6.3 Future Research ... 53Reference list ... 55

iii

Figures

Figure 1 Drivers of Greenwashing ... 8 Figure 2 Tree Diagram Environment-Specific Characteristics ... 34 Figure 3 Levels in Reducing Greenwashing with the EU Taxonomy ... 46

Tables

Table 1 Article Search Process... 6 Table 2 Interview Guide ... 29 Table 3 Interview Information ... 31

List of Abbreviations

CSR - Corporate Social Responsibility

ESG - Environmental, Social, and Governmental EU - European Union

INT - Interviewee

NFRD - Non-Financial Reporting Directive NGOs - Non-Governmental Organizations SDGs - Sustainable Development Goals UN - United Nations

1

1. Introduction

______________________________________________________________________ In this chapter we introduce the phenomenon of greenwashing and the new EU regulation that was put in place. We then present our research question in the case study of looking at the Swedish sustainable finance sector. To conclude, we describe the study’s perspective and delimitations.

______________________________________________________________________

1.1 Background

Recent theoretical developments have revealed the increasing numbers of companies that are recognizing the competitive advantage of promoting sustainable practices (Dimitrieska et al., 2017). However, oftentimes environmental claims made by companies are expressed very vaguely and may include inaccurate information as an effort to attract a “green” audience (Dimitrieska et al., 2017). A skepticism towards green organizations is on the rise from investors and consumers (De Jong et al., 2018). This is described by the phenomenon, namely greenwashing, and can be argued to be one of the biggest threats to sustainable development, yet it is a topic that is still not widely understood. Delmas and Burbano (2011) define greenwashing as the collision of two different firm behaviors, which occur when firms have strong positive communication about their environmental contribution, while still having poor environmental performance. This allows for unethical behaviors within organizations that are rarely monitored.

The idea of incorporating sustainable reporting and non-financial reports in companies has been around for many years or even decades. The goal of using such reporting methods is to receive positive reputations and recognitions from consumers and to provide more legitimacy for sustainable action (Vanhamme & Grobben, 2008). The trend in environmental reporting has been continuously increasing and is now seen as a crucial tool in demonstrating sustainable performance (Hedberg and, 2003). However, there is a lack of accepted uniform standards for accreditation, standardization, and evaluation of green investments, which slows down the process of mobilizing capital to meet sustainability objectives (European Commission, 2019b). In response to this, the European Union (EU) has created a new Taxonomy Regulation in an effort to increase green investments (European Commission, 2019a). The EU Taxonomy consists of a

2

classification system that will be legally binding for all EU Member States starting in December 2021. This was done to guide investments to appropriately defined green projects. The EU Taxonomy lays out a set of six environmental objectives (European Commission, 2020a). According to the regulation, an investment can only be qualified as European Taxonomy aligned if it substantially contributes to one or more of these objectives and does not significantly harm any (European Commission, 2020a). By implementing this new regulation, the EU will ensure that all Member States follow a uniform set of criteria in terms of green investing.

The EU Taxonomy is an essential action plan that will benefit our planet and our society to ensure sustainable growth (European Union Law, 2018). The purpose is to meet the emission reduction target set by the Paris Climate Agreement and the United Nations (UN) 2030 Agenda involving seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to slow down climate change, limit the emissions of greenhouse gases, and fight biodiversity loss. It constitutes a uniform classification system of sustainable economic activities to favor green investments (European Commission, 2019a). Moreover, it could potentially increase the share of renewable energy sources and convince investors to move away from fossil fuel energy investments as quickly as possible (Kempfer, 2019). By quickly increasing green investments, the EU will accelerate the expansion of renewable energies through technological innovation to create new economic opportunities (Kempfer, 2019).

1.2 Problem

For the past few decades, organizations have been required to make increasingly large contributions to social and environmental development. Investor and consumer expectations have shifted, and organizations now need to focus on their sustainable performance (De Jong et al., 2018). Yet, unsurprisingly, this has resulted in many firms trying to gain the benefits of being green without accounting for their actions, known as greenwashing (Delmas & Burbano, 2011; De Jong et al., 2018). Capital flows are not directed to companies that make significant progress in the field (De Jong et al., 2018; European Commission, 2019). Various authors have suggested that having a straightforward definition of greenwashing can cause more harm than good. The term is very ambiguous and needs to be understood in a multidimensional way (De Jong et al.,

3

2020). By its nature, the issue of greenwashing is becoming increasingly sophisticated and harder to detect, which raises the question of whether the EU Taxonomy truly has the potential to reduce it or not.

Before the introduction of the EU Taxonomy, there were no regulations in place to ensure a universal measurement of sustainable actions that are mandatory (Schuetze & Stede, 2020). This means that reports, such as Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) reports, are voluntary and allow companies to discuss only the positively contributing outcomes while withholding the negative outcomes (Vanhamme and Grobben, 2008). Yet, with the EU implementing numerous agreements to reach sustainable goals and climate neutrality by 2050, such as the SDGs in 2015, the Paris Climate Agreement in 2016, and the European Green Deal in 2019, it requires better regulation criteria for companies to follow (European Commission, 2020a). Moreover, it is becoming increasingly apprehensive that the economy must drastically transform to comply with the imposed EU goals. According to the European Commission (2020a), this is most influential for the financial market looking to invest in green bonds. Suppose companies do not clearly discuss how their activities are contributing to the EU environmental objectives. In that case, it can discourage investors from comparing different companies to find the most suitable sustainable investment for them (European Commission, 2020a). For this reason, it is imperative to study the potential impact the EU Taxonomy could have on transforming the investment sector.

As the EU Taxonomy is still at its preliminary stages, there are limited research articles regarding the potential effects it could have on greenwashing. The topic is still under current debate with different opinions on the potential success rate. For this reason, our research is timely and highly relevant in today’s business discussions on the EU Taxonomy. Our research will use the current information provided by the EU commission and relevant peer-reviewed articles to make a new connection on the effect the EU Taxonomy might have on greenwashing. More specifically, the focus will be maintained on the sustainable financial industry as it is the industry with the highest impact on the sustainable economy.

4

1.3 Purpose

This thesis aims to address “what the potential of the new EU Taxonomy is to increase transparency in the sustainable financial sector threatened by greenwashing.” A descriptive investigation of the current literature on problems within greenwashing can seek to identify the critical themes concerning the EU Taxonomy. With a comprehensive understanding of the impacts that the greenwashing phenomenon has on the sustainable financial sector, we thereby investigate how the EU Taxonomy can influence this. We use these themes to create a framework on which the EU Taxonomy may be most effective in reducing the types of greenwashing. This framework is tested through a qualitative case study within the Swedish sustainable financial industry to understand its feasibility and its consequences for sustainable investments.

1.4 Perspective

To better understand the effects of the EU Taxonomy on greenwashing, our study takes the investors' perspective. This point of view allows us to get an applicable insight on which areas of greenwashing investors could use the EU Taxonomy to gain more confidence.

1.5 Delimitations

The scope of the study will be limited to the case of Sweden. The potential of the EU Taxonomy is therefore not looked at from the perspectives of other EU Member States. Additionally, the sampled population is focused on a small amount of financial market participants with high knowledge on the sustainable sector. It therefore limits its coverage by not considering the entire financial sector.

5

2. Frame of Reference

______________________________________________________________________ The purpose of this chapter is to provide the theoretical background to the topic of greenwashing, the sustainable finance industry, and the new EU Taxonomy Regulation. This chapter concludes with an introduction to a preliminary framework that looks at what different types of greenwashing can be reduced with the EU Taxonomy.

______________________________________________________________________

In order to answer our research question, we established a theoretical background focusing on our key themes: (1) greenwashing, (2) the sustainable finance industry, and lastly, (3) the EU Taxonomy Regulation. The Frame of Reference starts by examining the phenomenon of greenwashing, more specifically its drivers and the different greenwashing types, as highlighted by relevant literature. We will also analyze the perception of greenwashing in the financial sector. The second theme continues with the sustainable finance industry by focusing on the lack of transparency in the current regulations and certifications of sustainable investments for investors. Our third theme introduces the new EU Taxonomy Regulation, its purpose, and its need in the current financial sector. The Frame of Reference concludes with an introduction to the preliminary framework of greenwashing types having the highest potential to be reduced with the EU Taxonomy. This literature research is the base knowledge needed to analyze the interconnectedness of our main themes and how our empirical results can build on this.

2.1 Method

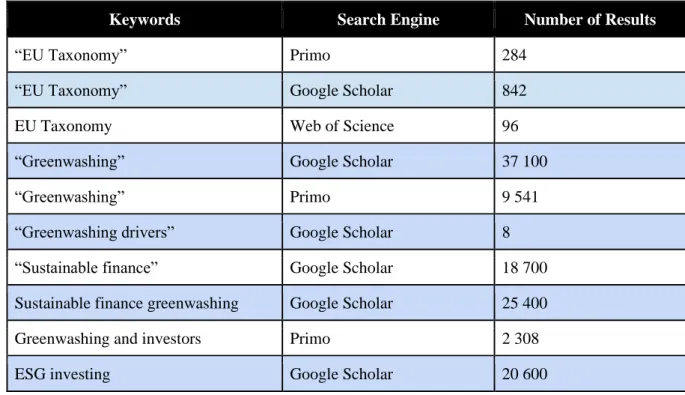

To efficiently find relevant peer-reviewed articles for our theoretical background, we used three specific search engines: Google Scholar, Primo, and Web of Science. Seemingly due to the recent publication of the EU Taxonomy, there was little research to be found. Therefore, we relied mainly on publications from the EU Commission to gather the necessary information on the EU Taxonomy. Furthermore, we selected relevant keywords that applied to our central themes to facilitate the research, such as “Greenwashing,” “EU Taxonomy,” and “Sustainable Finance.” Additionally, relevant word combinations were used to get more specific findings such as; “Greenwashing drivers”, “Sustainable finance

6

greenwashing”, and “Greenwashing and investors” (see Table 1). To categorize our findings, we constructed a table that included the article names, keywords found in the article, which journal it was published from, and any notes or comments. With this systematic process, we were then able to identify the most relevant articles for our study. By selecting our articles with specific criteria, we ensured they were all peer-reviewed and relevant in answering our research question. We compared different articles with similar themes to find recurring cited authors that were deemed most relevant to examine. Moreover, by focusing on recent articles, the validity of our research could be increased.

Keywords Search Engine Number of Results

“EU Taxonomy” Primo 284

“EU Taxonomy” Google Scholar 842

EU Taxonomy Web of Science 96

“Greenwashing” Google Scholar 37 100

“Greenwashing” Primo 9 541

“Greenwashing drivers” Google Scholar 8

“Sustainable finance” Google Scholar 18 700 Sustainable finance greenwashing Google Scholar 25 400

Greenwashing and investors Primo 2 308

ESG investing Google Scholar 20 600

Table 1: Article Words Search

2.2 Greenwashing

2.2.1 History of the greenwashing phenomenon

The greenwashing phenomenon already began in the late 1980s, yet, with very little literature on it. The topic only began to take off with the book on environmental marketing by Greer and Bruno in 1996. This book describes how 20 big corporations heavily lie and deceive the public with their environmental intentions and behaviors (Gottlieb, 1998). The book also describes the theory of “green capitalism” in detail to deliver the first glimpse of green marketing’s complexity (Gottlieb, 1998). Understanding greenwashing

7

is not always found through the nature of experiments but rather theoretical findings (De Vries et al., 2013). It is said by Vries, Terwel, Ellemers, and Daamen (2013) that the evidence of greenwashing is seen as consequential instead of precedent. Companies that can be accused of greenwashing must give out a message that is proven false while also misleading the consumers and investors with their promises (Seele & Gatti, 2015). In the survey conducted by TerraChoice in 2007, 1018 products with a “green” message were examined, and over 95 percent of the products demonstrated some level of greenwashing. This led to governments attempting to set more guidelines for environmental information; however, with the significant rise in environmental interests by consumers and investors, the commissions could not keep up (TerraChoice, 2007). Nevertheless, there are also increasing amounts of truly sustainable companies entering the market, making it even harder for investors to compare companies claiming the same environmental benefits when few follow through with their promises (Hohnen & Potts, 2007).

2.2.2 Drivers of Greenwashing

To further analyze the greenwashing phenomenon and how this impacts the sustainable financial industry, it is necessary to also look at greenwashing’s specific drivers. The immense growth in greenwashing is seen as a significant contributor to the lack of confidence investors face in green bonds (Delmas & Burbano, 2011). This is leading to higher numbers of socially irresponsible investing. “Why, then, do firms engage in greenwashing despite these risks?”. This is the question that Delmas and Burbano ask themselves in their widely reviewed and discussed study on the greenwashing drivers from 2011. It was referenced by many peer-review authors, including De Jong et al., as well as Lyon & Montgomery. This study analyzes the drivers of greenwashing through information gathered from work in management, strategy, sociology, and psychology. This is a critical research study for our work to accurately understand greenwashing and its circumstances for companies, consumers, and investors. These drivers are split into three levels: external, organizational, and individual (see Figure 1) that will now be looked at more closely.

8 Figure 1: Drivers of Greenwashing

Source: Delmas, M. A., & Burbano, V. C. (2011). The drivers of greenwashing. California management

review, 54(1), 64-87.

(1) Non-Market External Drivers: The Regulatory and Monitoring Context

Globally speaking, there are minimal amounts of regulations in place to avoid greenwashing. This is seen as one of the critical drivers of greenwashing. The study mentioned some efforts, such as the Federal Trade Commission in the United States, that have implemented an advertising violation section that can allow companies to be fined up to 10,000 dollars or even one year in prison. Nevertheless, regulations such as the Federal Trade Commission advertising violation have shown insufficient enforcement efforts. With limited knowledge of what can be qualified as misleading or punishable compared to harmless miscommunication, regulations do not take the necessary action to detect greenwashing that is misleading consumers. Where the regulations are lacking, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) have stepped in to create more pressure with the media’s help to monitor greenwashing and hold these companies accountable for their lies. What the world is in desperate need of is a fundamental change in environmental actions and having such a large number of companies deceiving the public about doing

9

the right thing is not helping the actual cause at hand. NGOs have begun to share the message that consumers and investors need to open their eyes to the widely spread misinformation on environmentally positive claims.

(2) Market External Drivers: Consumer, Investor, and Competitor-Induced Incentives

This driver focuses on the competitive pressure from the consumers and investors to appear more sustainable. This could incentivize unsustainable companies, also known as brown companies, that are not attempting to incorporate environmentally friendly practices to greenwash because of demands shown from stakeholders. In today's society, it can be observed that sustainable companies are now starting to receive the competitive advantage that brown firms wish. Thus, with the fear of falling behind the sustainable companies, brown companies risk the practice of greenwashing in order to keep up.

(3) Organizational-Level Drivers

The firm's size can also play a significant role in greenwashing drivers as larger firms face considerably higher levels of pressure from investors than small or medium-sized firms that are not yet publicly owned. Organizations will gain more extensive access to green consumers and investors and use greenwashing to their advantage. Differences in organizational drivers can also be found based on how ethically engaged a company is or whether they are still solely driven by economic incentives. If brown companies do not value ethical behaviors very highly, they are more inclined to engage in illegal or morally unacceptable behaviors such as greenwashing. Other firms that work more socially responsible would avoid the shortcuts of greenwashing. Additionally, organization scholars have examined factors on information sharing within an organization. For companies that do not have a robust system in place for the transfer of knowledge, it is far easier for inadvertent greenwashing due to accidental miscommunication.

(4) Individual-Level Psychological Drivers

Finally, the study examines the drivers on an individual level. This can indicate uncertainty about greenwashing's negative repercussions for leaders or managers in their decision-making process. These individuals may not have the tools and information necessary to make these difficult decisions without understanding the effects of greenwashing activities for the firm. This can be considered narrow decision-making that

10

does not involve considering consequences in the future and is rather done in isolation (Kahneman & Lovallo, 1993).

With these drivers, we can determine the most prevalent drivers of greenwashing that could affect the relationship between companies and investors. We see that the non-market and non-market drivers are most critical to look at when determining the effects greenwashing will have on green investing. The internal drivers instead look at how the company makes the decisions internally which is not a focus for the EU Taxonomy.

2.2.3 Types of Greenwashing

To better understand how the EU Taxonomy could help increase transparency within the financial sector, it is crucial to examine the different types of greenwashing in the current market. In order to do so, different peer-reviewed articles were assessed, and relevant greenwashing types were identified. Additionally, the TerraChoice (2007) "Six Sins of Greenwashing" were used to give examples of how greenwashing looks like in practice. As previously mentioned, there is no common consensus of what the topic of greenwashing entails. It is indeed ambiguous and needs to be understood in a multidimensional way to be addressed (De Jong et al., 2020). Once all the main types of greenwashing have been identified, we can assess which ones are the most relevant for the financial industry and how the EU Taxonomy could potentially reduce them.

(1) Selective Disclosure

Perhaps one of the most broadly studied types of greenwashing is selective disclosure (Lyon & Montgomery, 2015). Marquis, Toffel, and Zhou (2016) define this as “a symbolic strategy whereby firms seek to gain or maintain legitimacy by disproportionately revealing beneficial or relatively benign performance indicators to obscure their less impressive overall performance”. Even though this form of greenwashing has been widely studied, researchers still have not come to a common understanding of whether greener firms are the ones who disclose more information or not (Lyon & Montgomery, 2015). Without a uniform set of criteria for what information needs to be disclosed to the public, firms can strategically reveal only parts of their private information to create a misleading and overly optimistic narrative based on inaccurate

11

environmental claims (Marquis et al., 2016). TerraChoice (2007) identifies three sins that fall under selective disclosure, which can be for understanding how firms use this type of greenwashing.

The Sin of the Hidden Trade-Off

Netto et al. (2020) define this sin as claiming, “a product is ‘green’ based on a narrow set of attributes without attention to other important environmental issues”. This could, for example, include paper companies who claim that their products are sustainably harvested yet do not bring any attention to the environmental impacts of manufacturing (TerraChoice, 2007).

The Sin of Lesser Two Evils

This sin includes ‘green’ claims made to distract consumers or investors from the more considerable impacts the product has on the environment. These claims might be truthful within the product category, yet they are not helpful if a consumer wants to make environmentally friendly choices (Netto et al., 2020). For instance, organic cigarettes are marketed as a greener alternative for smokers; however, the health effects and air pollution caused by smoking remain the more significant issue that is not addressed (TerraChoice, 2007).

The Sin of Irrelevance

The Sin of Irrelevance includes claims that distract consumers and investors from finding greener alternatives by providing unimportant information. To illustrate, many firms still have labels stating that they are ‘CFC-free’, even though CFC has been legally banned for almost 30 years (TerraChoice, 2007).

Additionally, in a study made by Gillespie (2008), two more greenwashing signs were identified that contribute to selective disclosure. This includes Fluffy Language, which concerns “words and claims with no clear meaning”, and Best in Class which refers to companies claiming that they are slightly greener than competing companies, even though their competitors would be causing substantial environmental damage (Gillespie, 2008).

12 (2) Empty Green Promises

Firms often issue green promises and claims that they cannot live up to (Lyon & Montgomery, 2015). Many have been accused of making empty promises as a method of green marketing, which has led to a decrease in trust for green products and companies (Saha & Darnton, 2005). Until recently, firms have not been legally obligated to publish environmental policy statements or fulfill empty green claims (Ramus and Montiel, 2005). Therefore, it is no surprise that significant evidence of greenwashing can be linked to the use of unfulfilled environmental promises (Lyon & Montgomery, 2015). TerraChoice identifies two types of greenwashing that can be linked to Empty Green Promises.

The Sin of No Proof

TerraChoice (2007) defines the Sin of No Proof as “any environmental claim that cannot be substantiated by easily accessible supporting information, or by a reliable third-party certification”. If environmental claims cannot be verified, the firm is unlikely to do what it is claiming to do, and promises are less likely to be fulfilled.

The Sin of Vagueness

The Sin of Vagueness consists of claims that are too broad and can easily be misunderstood by consumers and investors (TerraChoice, 2007). This includes, for instance, green promises that do not specify the timeframe in which they are supposed to be met. Additionally, claims such as “All-Natural” and “Eco-Friendly”, are too broad to have any meaning without being elaborated on (Netto et al., 2020).

(3) Untrustworthy Certifications and Labels

Lyon and Montgomery (2015) argue that some environmental certifications can be used as a form of greenwashing in certain instances. Even though certifications and labels can be an efficient way of reducing greenwashing, they are not immune to the phenomenon itself. One of the most well-known certifications for environmental management is ISO 14001, which has been created for organizations seeking to manage their responsibilities in a way that contributes to environmental sustainability (ISO, 2015). However, even though the certification has been widely accepted globally, there is still evidence suggesting that it is solely used to impress external stakeholders. Additionally, some

13

studies have found that ISO-certified companies do not have a higher degree of regulatory compliance than non-certified companies (Lyon & Montgomery, 2015). Untrustworthy certifications and labels are a type of greenwashing that can be highly misleading for investors, as actually green companies become impossible to detect. TerraChoice identified one sin that relates to this type of greenwashing.

The Sin of Worshipping False Labels

By using certification-like images and false suggestions, companies can mislead consumers and investors into thinking that a legitimate third party has been involved (Netto et al., 2020). However, many of these certifications are too vague or irrelevant to tell the consumers and investors about the true state of ‘greenness’ in that company. Gillespie (2008) also highlights that many companies mislead external stakeholders by using information that can only be understood and fact-checked by scientists and made-up labels that look like third-party endorsements. This type of greenwashing can be tough to detect, as labels and certifications are usually associated with signifying trustworthiness.

(4) False Narrative and Lying

Much of the other types of greenwashing have been focused on creating loopholes that do not force the companies to state anything that is blatantly untrue. However, in some instances, companies have been caught creating environmental narratives based solely on lies (Lyon & Montgomery, 2015). This form of greenwashing is the most uncommon one, as it is highly unethical and can severely damage a company’s reputation if they were to get caught. Nevertheless, it is still essential to consider getting a complete understanding of the different existing types of greenwashing. TerraChoice defines this additional sin as followed.

The Sin of Fibbing

Environmental claims that are untrue and are solely based on false information. This can, for instance, include misrepresentations of certifications created by independent authorities (TerraChoice, 2007). The study provided examples of shampoos claiming to be “certified organic” even though no such certifications were found to exist.

14 2.2.4 Greenwashing in the Financial Sector

Previous studies have mainly focused on consumers’ greenwashing perspectives but rarely on investors’ perspectives, while companies are now seeking more alternative forms of financing and, therefore, new investors (Nyilasy et al., 2014; Gatti et al., 2021). Nowadays, stakeholders tend to be more unsure about investing due to consumers’ and medias’ pressure for environmentally friendly products and services (Gatti et al., 2021). The numerous public scandals firms had to face because of greenwashing actions, such as Volkswagen’s development of a device to manipulate carbon emissions, has participated in investor’s deceptions (Siano et al., 2017). However, the lack of definition and regulation regarding greenwashing makes it hard to regulate and punish by the law (Delmas & Burbano, 2011).

The vague or misleading communication done by organizations gives investors the impression that the company met its objectives and, therefore, followed its green engagements (Gatti et al., 2021). It is usually more complex, explaining why companies try to show a greener side to meet the stakeholders’ expectations (Gatti et al., 2021). Therefore, greenwashing is widely used in organizations reporting in order to strategically select the positive information a firm has to attract more shareholders, leaving aside their negative or potentially harmful performances (Bini et al., 2018). By using greenwashing and manipulating their information for the most favorable performances, organizations hope to convince and satisfy their stakeholders’ expectations (Beske et al., 2020; Hahn & Lülfs, 2014).

However, greenwashing is not without consequences when it comes to the investors’ reactions and responses as it impacts their perception of an organization (Collison, Lorraine & Power, 2003). The use of greenwashing is intentional when it comes to its communication; it sometimes leads to reputation problems, scandals, or boycotts for the organization (Torelli et al., 2019). Adverse effects on the investment side usually follow the misleading communication on the environmental benefits of a product or a service once it is discovered. Investors tend to lose their confidence and are starting to get more skeptical about green products (Delmas & Cuerel Burbano, 2011). These actions often lead to stakeholders’ deceptions which can negatively impact an organization’s

15

investments (Gatti et al., 2021). Another issue that has been highlighted regards the increasing demand investors have for environmentally friendly firms. Consequently, unsustainable firms are more likely to use greenwashing in their communication to appeal to their interest and try to convince them (Vos, 2009). The pressure stakeholders might put on organizations for greener actions can also lead to counterproductive consequences and encourage greenwashing (Delmas & Burbano, 2011).

Therefore, greenwashing needs to be considered by companies, not only from their customers’ perspectives but also from their investors’ perspectives (Gatti et al., 2021). Torelli et al. (2019) reached the same conclusion in their study and highlighted the need for companies to be more cautious in disclosing their environmental strategies and activities. Being transparent can improve their legitimation and improve their investors’ perceptions of the firm and its activities. A company’s communication style will have repercussions on its shareholders and should be part of the overall communication strategy (Torelli et al., 2019). Organizations’ understanding of greenwashing and its consequences is essential to avoid suspicion or loss of legitimacy. The communication strategies directly affect the stakeholders and should be included in the overall strategy’s decision-making process. Stakeholders also need to be aware and understand greenwashing in order to avoid investment deceptions as it is a broad concept that can be implemented in various ways and at different levels of an organization (Torelli et al., 2019).

2.3 Financial Sector

2.3.1 Sustainable Finance

In the urge of direct investments towards sustainable activities, sustainable finance has started to become very popular (Flammer, 2021). The concept of sustainable finance has evolved over the last decades embedding sustainability at different levels of both the society and the financial system (Flammer, 2021). The EU Commission (2020a) defined sustainable finance as investment decisions made considering the environmental, social, and governmental (ESG) considerations to favor long-term investments in sustainable economic activities. According to Fatemi and Fooladi (2013), we tend to have a narrow definition of value creation, excluding most non-financial costs and the adverse outcomes

16

on the social and environmental aspects. These are often excluded for the purpose of economic benefits. Therefore, Fatemi and Fooladi (2013) suggest focusing on a sustainable value creation approach, where the social and environmental costs and benefits are accounted for, instead of the traditional shareholders’ wealth maximization. Thus, sustainable finance aims to support economic growth while reducing the pressure on the environment and including the social and governmental perspectives (EU, 2020a).

It is achieved by channeling private, and public capital flows towards green investments for climate-neutral activities and ensuring a resilient economy. The European Green Deal is part of the EU Commission’s measures to support the EU’s climate and energy targets for 2030 and meet the Paris Agreement (EU, 2020a). The EU has also recently announced an EU Green Bond Standard as green bonds play a significant role in sustainable finance. It is bonds that financed the assets needed for the carbon-neutral transition as they are committed to supporting environmental and climate-friendly projects (Flammer, 2021). As green bonds require third-party verification to ensure the project’s environmental benefits being financed, companies often use this as a credible sign of their sustainable transition. This is highly valuable for the investors who often lack information and data regardings the company’s environmental commitment (Lyon & Montgomery, 2015). For these reasons, green bonds have become highly popular in recent years, but the lack of standards makes it complicated for investors to accurately assess these investments’ effectiveness and credibility (EU, 2020a).

2.3.2 How Investors Evaluate Companies for Sustainable Investments

Sustainable investing can be seen as an umbrella term for several environmentally friendly investment categories such as ESG or CSR disclosed in the non-financial reporting directive (NFRD) (Caplan et al., 2013). Often investors refer to one of these for the investment process they wish to pursue (Van Durren et al., 2015). These are necessary to know in order to make a comparison with the EU Taxonomy and how the responsible investment process may shift in the near future. Traditional investing, on the contrary, evaluates companies solely through monetary criteria such as a cash flow analysis. This neglects the critical areas of environmental and social values that are part of the triple bottom line. That is why an increasing number of investors have adopted sustainable

17

investments in their practices. The idea of incorporating more transparency in the sustainable investment industry is a significant research gap to consider (Cunha et al., 2020). The sustainable reporting that this study focuses on is ESG investing, as well as the NFRD.

(1) Environmental Social and Governmental Investing

ESG investing considers the companies’ reports on their environmental data regarding resource consumption and emissions, social data on organization structure and behaviors, and governance based on diversity, politics, and corruption programs (Amel-Zadeh & Serafeim, 2018). According to Amel-Zadeh and Serfeim’s survey (2018) on ESG, focusing on social and environmental aspects rather than purely profit has become an apparent trend in financial markets. Despite this, it can still be seen that mainstream investors are slow in adopting sustainable investment opportunities, and there is more to be done (Friede et al., 2015). The global survey done by Amel-Zadeh and Serfeim gained much attention on the motivations for using ESG in the investment process while also addressing the challenges of using ESG information. The motivations are listed as performance motives, financial motives, and norms-based motives. The most prominent motivations found in the survey included financial reasons for growing client demand and development of investment products. Amel-Zadeh and Serafeim conclude their study by addressing the biggest threats to using ESG in the investment process. This includes the difficulty of comparing the information from the results amongst different firms and the lack of standards regarding the ESG reporting. This makes it more challenging for investors to successfully use the ESG information provided by companies and could demotivate them from integrating sustainable investment in their decision-making process.

(2) Non-Financial Reporting Directive

The NFRD (Directive 2014/95/EU, NFRD) requires large companies with over 500 employees to disclose non-financial information considered essential for the sustainable transition (EU, 2020b). This amendment combines the long-term profitability of the global economy with social justice and environmental protection (Beerbaum, 2021). Thus, the NFRD spreads awareness about CSR issues within the European Community and increases transparency in the information provided by the companies (Caputo et al.,

18

2019). It does this by asking them to disclose their environmental matters; social responsibility and treatment of employees; respect for human rights; anti-corruptions and bribery; and diversity on the company board (in terms of age, gender, educational and professional background) (EU, 2020b). They will also be able to disclose information regarding their business model, their policies, their outcomes, risk management, and key performance indicators they believe are relevant (Beerbaum, 2021). The regulation leaves some room for companies to adapt; if they cannot justify the five matters mentioned above, they will have to explain why not doing so (Beerbaum, 2021).

Therefore, it is a way to incentivize companies to have a responsible approach to their reporting system without imposing excessive obligations (Caputo et al., 2019). However, it can be perceived as a gap, as no standards or frameworks provide specific requirements, such as the types of indicators per sector (Beerbaum, 2021). It provides the opportunity for companies to disclose information they consider relevant but might also allow them to select specific information and avoid disclosing others. The NFRD keeps adapting over time and follows up with the new regulations that the EU is publishing. Thus, the Commission will adopt a new delegated act this year, specifying the information companies will have to disclose how and to what extent their activities align with those considered environmentally sustainable by the EU Taxonomy regulation (EU, 2020b). It provides the investors, civil society organizations, and other interested parties with the non-financial indicators to assess the companies’ performances and alignment with the EU Taxonomy (EU, 2020b).

2.3.3 Company and Investor Relations

Another perspective that is crucial to consider in order to understand the implications of the EU Taxonomy on investors is how companies manage their relations with investors. Traditionally, managing investor relations has mainly been focused on accurately valuing the firm in monetary value. However, for the past two decades, investors have increasingly paid more attention to the non-financial aspects of the companies they decide to invest in (Hockerts & Moir, 2004). Therefore, environmental and social aspects are now critical for companies to consider if they want to ensure long-lasting investor relationships. According to Hockets and Moir (2004), when all investor relations

19

professionals included in their study were asked to explain corporate responsibility, they were aware of how it encompasses social, environmental, and economic aspects.

Additionally, it has been found that firms with higher levels of information disclosure through investor-relations have more institutional shareholders and higher market capitalization (Chang et al., 2008). However, even though companies seem to understand what the investors expect from them, greenwashing prevails, and investor confidence is lacking (Delmas & Burbano, 2011). Ferrón‐Vílchez, Valero‐Gil, and Suárez‐Perales (2021) suggests that the reason why companies still greenwash is that it could be partly unintentional. This could be because some companies use environmental certifications for auditing purposes and to comply with specific requirements. If this is the case, then hiding information and misleading the investors is not the motivation behind their actions. Instead, companies are simply trying to comply with requirements set by, for instance, regulators or suppliers (Ferrón‐Vílchez et al., 2021).

2.3.4 Lack of Regulation in Sustainable Financial Sector

The European sustainable finance sector plays a crucial role in meeting the policy objectives set by the European Green Deal. Additionally, the sector has a crucial part in ensuring a resilient economy and sustainable recovery from damages caused by COVID-19. The importance of the sustainable financial sector for the European Union is undeniable. Nevertheless, as mentioned above, one prominent issue remains to be unsolved. There is a lack of accepted uniform standards for accreditation, standardization, and evaluation of green investments, which slows down the process of mobilizing capital to meet sustainability objectives.

Regarding ESG investments, specific investment classification tools within specific problems have not been developed so far. Plastun, Makarenko, Yelnikova, and Makarenko (2019) identify three main complex problems where regulations regarding ESG investments are still missing. Namely, (1) existing abundance of different models for environmental aspects of corporate activities, (2) absence of universal governance theory, and (3) there is a significant difference with the interests of internal and external stakeholders regarding responsible investments (Plastun et al., 2019). Additionally, other

20

standards such as the recommendations of the World Federation of Exchanges, as well as the Model Guidance on Reporting ESG Information to Investors of Sustainable Stock Exchanges Initiative are solely general guidelines for investors and companies.

The most suitable methods, principles, standards, and responsible activity tools should be adopted for every investment process (Plastun et al., 2019). By having a standardized form of classification criteria for sustainable investments, coordination and compliance amongst investors and companies can be improved. Regulators will be able to evaluate investments by implementing control procedures and practices across the sector. This will, most likely, leave less opportunity for companies to greenwash, and appropriate investments can be guided towards projects that will support sustainable economic growth and help in achieving global environmental targets. With the help of the EU Taxonomy, the issue at hand can be addressed, and the potential for a more sustainable financial sector exists.

2.4 EU Taxonomy Regulation

2.4.1 What is the EU Taxonomy?

On March 8th, 2018, the EU Commission published a comprehensive action plan regarding their approach to sustainable finance. At the heart of this plan, the need for a unified classification system for sustainable activities was established. According to Dombrovskis, the Vice-President in charge of the Financial Stability in the Financial Services and Capital Markets Union,” To meet our Paris targets [EU becoming

climate-neutral by 2050], Europe needs between €175 to €290 billion in additional yearly investment in the next decades. […] Yet, public money will not be enough.” (European

Commission, 2019b). Therefore, in June 2020, the European Council and the Parliament announced that the “Regulation (EU) 2020/852 on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment, and amending Regulation (EU) 2019/2088,” commonly name the “EU Taxonomy Regulation” has been voted (EU, 2020a). The first delegated act on sustainable activities for climate change adaptation, and mitigation objectives were published on April 21st, 2021 (European Commission, 2021). A second delegated act for the remaining objectives will be published in 2022. The term ”taxonomy” is used as this regulation is a classification system that determines whether an economic activity is

21

qualified as environmentally sustainable and to which degree to ensure sustainable investments (Article 1; EU, 2021). Therefore, this unified classification system aims to incentivize private capital flows towards green projects and provide guidance and transparency for policymakers, industries, and investors to reach a climate-neutral economy. The Taxonomy Regulation has a significant scope of action, including the entire management industry, which cannot deny the application of this classification (Ingman, 2020).

The EU Taxonomy is based on a core set of six Environmental Objectives, which are as follow (Article 9; EU, 2021):

❖ Climate change mitigation,

❖ Climate change adaptation,

❖ The sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources,

❖ The transition to a circular economy,

❖ Pollution prevention and control,

❖ The protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems.

Any activities that substantially contribute to one or more of these Environmentally Sustainable Economic Activities will be classified as sustainable in the EU Taxonomy. Additionally, any activities that directly enable other activities to contribute to one or more environmental objectives substantially will be classified as ”Enabling Activities” (Article 16; EU, 2021). The function of the EU Taxonomy is supplementary to the NFRD (Ingman, 2020). It will require large EU public-interest corporations and financial firms to publish their data regarding their activities’ impacts on technical screening criteria and to which extent these activities are environmentally sustainable. Each Member State is obligated to have competent authorities ensuring that financial market participants comply with the technical screening criteria presented by the EU Taxonomy.

According to the EU Taxonomy Regulation (2020/852), these six objectives will be more closely looked at through the criteria for climate mitigation (2021). For example, the EU Taxonomy requires companies to declare the use of renewable energy in terms of generating, transmitting, storing, or distributing. Additionally, the company must work

22

towards improving energy efficiencies and clean or climate-neutral mobility. Materials used must also be sourced sustainably without mitigating natural landscapes. The EU Taxonomy will also require companies to disclose their economic activities concerning sustainability. This ensures better transparency in terms of what proportion of the company’s turnover can be linked to environmentally sustainable activities. To better assess a company’s different criteria on environmental impacts and transparency, a technical screening will be done by the EU commission. This includes the identification of short-term and long-term impacts of economic activities, as well as the minimal obligation that is needed to prevent significant harm to the six environmental objectives. The company’s footprint will also be assessed per union labeling and statistical certifications while also determining the product/service life cycle, especially the use and end life. The screening will look for inconsistencies in a company’s incentives to transition to a sustainable market and economy (EU, 2021).

This single classification system applied in Europe will have consequences far beyond the geographical boundary of the EU by shaping the flow of investments, influencing the financial regulations, and mapping the future of sustainable finance (Ingman, 2020). Due to this framework’s legitimacy, the EU can expect to attract investors from outside, looking for reassurance in their sustainable investment and avoiding greenwashing. The focus today of the EU Taxonomy is the environmental perspectives due to the Paris Climate Agreement’s goal. Even if the classification indirectly addresses the social and governance aspects, the European Commission is already planning a broader ESG Taxonomy proposal, including all three perspectives, by December 31st, 2021 (Ingman, 2020).

2.4.2 Need for the EU Taxonomy

The absence of regulations and punishment of greenwashing and the communication of false information about company’s environmental practices lead stakeholders to lose trust and confidence in green investments (Delmas & Burbano, 2011). This creates a challenge for investors and funds supporting ESG to evaluate and assess accurate green investments as there is an absolute lack of verifiable information. The current regulatory system does not help and is even considered a key driver of greenwashing due to the limited punitive

23

consequences (Delmas & Doctori Blass, 2010). The variation of regulations in different countries increases the complexity of the problem as organizations tend to have cross-country practices. The regulatory context also has indirect consequences on the other drivers of greenwashing, identified by Delmas and Burbano, as it influences organizations’ communication availability and reliability.

The purpose of the EU Taxonomy in the first place is to create a more transparent structure for green investments in order to facilitate and encourage stakeholders’ investments in sustainable practices (EU, 2020a). This might have positive consequences on greenwashing as it will pressure companies to have more transparent records and communication. However, the EU Taxonomy will not focus on the types of greenwashing these regulations will affect or the benefits this might have on the investors’ confidence and other issues that might arise from these new classifications. The critical themes we identified in the literature regarding greenwashing will be looked at through the lens of the EU Taxonomy and its influence on the financial sector and will, later, allow us to create a framework focusing on the different types of greenwashing the EU Taxonomy might reduce the most. This framework will be made from the investors’ perspectives, as they face the different types of greenwashing and, therefore, will bring a better understanding of this complex phenomenon.

Nevertheless, it is still unclear whether the financial sector contributes to sustainable development because of profitable opportunities or the benefit of society and the environment (Wiek and Weber, 2013). That is why the EU Taxonomy can be seen as a necessary tool to improve transparency in the financial sector and better understand their perspective towards sustainable development. This will be done through stricter regulations that will need to be followed by companies. It should reduce the chance for companies to display misleading information or false claims and should help investors make better comparisons between different companies.

2.5 Summary of Frame of Reference

By analyzing the interrelation between greenwashing, the sustainable investing industry, and the EU Taxonomy Regulation, we are now able to summarize and identify which forms of greenwashing we deem to have the most potential in being reduced by the EU

24

Taxonomy. Existing literature more often discusses what follows greenwashing rather than what leads to greenwashing. That is why we will use the new sustainable regulation, the EU Taxonomy, to propose preliminary findings on a framework that could reduce greenwashing from occurring instead of dealing with the consequences.

2.5.1 Our Suggested Types of Greenwashing

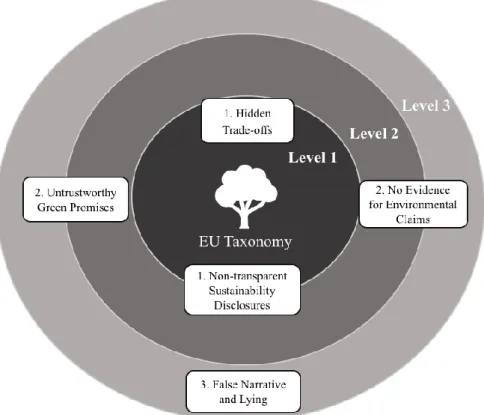

Taking examples from the types of greenwashing described by existing literature from TerraChoice, Lyon & Montgomery, and Gillespie, we have chosen the most relevant forms of greenwashing in terms of the investor’s perspective and the Taxonomy Regulation. These were modified to be more fitting to our purpose and are found as the following: (1) Hidden Trade-offs, (2) Non-transparent Sustainability Disclosures, (3) No Evidence for Environmental Claims, (4) Untrustworthy Green Promises, (5) False Narrative and Lying, (6) Unreliable Certifications and Labels. These types of greenwashing were presented to the interviewees to gain knowledgeable insights from people in the financial sector. They were asked to rank them from highest potential to be reduced by the EU Taxonomy to least potential to be reduced by the EU Taxonomy.

(1) Hidden Trade-offs

The hidden trade-off is by far the most common type of greenwashing. Firms can mislead investors by strategically disclosing only positive aspects of their financial activities, leaving out information that could potentially be harmful to them. However, as the EU Taxonomy requires firms to state their performance regarding all six environmental objectives, it leaves less room for hidden trade-offs to be made. For a company to be EU Taxonomy aligned, it is required that none of the six objectives are significantly harmed, meaning that it could potentially reduce this form of greenwashing.

(2) Non-transparent Sustainability Disclosures

It was found that many of the currently published sustainability reports do not follow a uniform set of criteria on what environmental information needs to be disclosed. Many claims remain too vague and can easily be misunderstood by investors. The EU Taxonomy provides investors with information that has been approved by competent

25

authorities and will not leave any space for vague and non-transparent sustainability claims.

(3) No Evidence for Environmental Claims

Companies commonly use greenwashing to communicate about sustainable actions or behaviors they have without supporting these claims with evidence. Such misleading information often leads to confusion on the investors’ side, as they are not provided with any supporting data and can only base their judgment on trust. The six Environmental Objectives stated by the EU Taxonomy have potential, as the classification will verify the environmental claims made by these companies according to their sustainability reports and the EU Taxonomy’s criteria. In order to reassure investors with access to evidence and data supporting the companies’ environmental claims.

(4) Untrustworthy Green Promises

Green promises are often made to convince investors of the companies’ willingness to become more sustainable as it is their primary interest. However, these are often empty promises due to the considerable engagement and the potential costs it represents. It is also current that companies do not respect the deadline set in the first place and extend it as they did not manage to meet their promises on time. Again, this creates an unpredictable climate between the company and the investors. The EU Taxonomy will not consider empty promises made by companies and instead focus on facts and data to have an unbiased judgment.

(5) False Narrative and Lying

Sustainable reporting, such as CSRs, and ESGs, have made it easy for companies to lie about the information they communicate to investors as there are no clear guidelines as to what information needs to be disclosed in the report. We identify the EU Taxonomy to have the potential to eliminate this type of greenwashing problem, as the data given by the company will be analyzed with the technical screening criteria done by an expert EU Commission board. The regulation will especially look towards transparency in the company and determine any unethical behaviors in the published data.

26 (6) Unreliable Certifications and Labels

From the articles we reviewed about greenwashing, it was discovered that there are existing labels and certifications that are presumed to be unreliable or even false. Investors can be misguided by sustainable labels that are not truthful and can cloud their judgment on how sustainable a company truly is. The EU Taxonomy will be a trustworthy classification that will determine what companies are aligned with the EU Taxonomy’s criteria and bring more confidence to the investors’ choice in sustainable companies.

27

3. Methodology

______________________________________________________________________ This chapter first describes the research approach and the case selection for this study. It then goes to define the research philosophy chosen, followed by the data collection and data sampling. Thereafter, the chapter goes into the method of how the data is analyzed. It finishes with the ethical considerations taken in this study.

______________________________________________________________________ Given the nuance of the determining factors to be analyzed, this thesis will adopt a qualitative case study approach using the sustainable finance sector in Sweden. An exploratory case study approach was deemed most suitable for the study, as this allows us to build relationships between already existing research and our Empirical Findings (Stebbins, 2008). This approach will allow the study to have an in-depth exploration of the greenwashing phenomenon and build on existing theory (Yin, 2009). The data collection process uses a Frame of Reference to identify the determinants of the lack of transparency in the sustainable finance sector and conduct interviews to study the implications of the EU Taxonomy further.

3.1 Case Selection

The case study aims to recognize the dynamics of the single setting presented (Merriam, 2002). We seek to understand the particular business group of sustainable investors. As the European sustainable financial sector encompasses numerous countries, the study was narrowed down by focusing on the case of Sweden. The country has been ranked in the top ten of the Environmental Performance Index for more than a decade and is the first country in the world to have passed an environmental protection act (Environmental Performance Index, n.d.). Additionally, Sweden often ranks as one of the least corrupt nations in the world and one of the happiest (Simons & Manoilo, 2019). This shows that Sweden is a very progressive country in environmental action and is a pioneer in sustainable development. Therefore, it can be assumed that the sustainable financial sector will be more willing to implement a classification system as the EU Taxonomy sooner than perhaps other European countries. Moreover, as the country has such a significant focus on sustainable development, the investors will be familiar with the concept and offer insightful information about how they are impacted by greenwashing.

28

A limitation that often arises with a case study approach is that there exists little basis for generalization (Yin, 2009). This means our findings may be relevant for our case that was selected yet, more difficult to transfer to other settings. We aim to solve this external validity by providing sufficient transparency in the description of our methodology and steps taken in order for better trustworthiness. The researcher's background, as well as their level of involvement in our research is also discussed to ensure transparency on the selected case.

3.2 Research Philosophy

We used the paradigm of interpretivism as our research philosophy because the topic of study is not quantifiable; instead, we must interpret the insights from professionals in the field to develop a workable framework (Merriam, 2002). Furthermore, to develop a framework on greenwashing, it is vital to establish the social reality in a subjective matter. Interpretivism uses a smaller sample size that focuses on generating highly valid theories and allows the results and theory to be generalized to similar settings. Therefore, the use of interpretivism is seen as most suitable for this study.

3.3 Data Collection

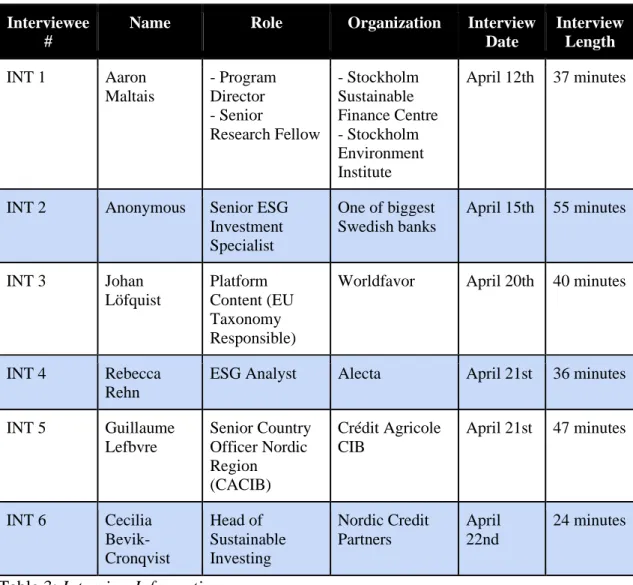

Accordingly, we collected our data through multiple interviews based on the inductive approach to better understand the sustainable financial sector and the potential and implications of the Taxonomy on green investments. The inductive theory approach allows us to use the observations and theories from our collected data to identify clear patterns and links, which we can condense into a summary format (Thomas, 2003). However, as suggested by Dietterich (1989), taking an inductive approach might limit us to only consider a small number of potential hypotheses. Nevertheless, this limitation could be overcome by continuously reviewing the patterns and by being critical of the links we identify. Additionally, the transcripts were read several times to identify emerging themes (Thomas, 2003). This systematic approach helped us to develop a comprehensive summary of our Empirical Findings.

29

The interviews were conducted with investors and specialists of the sustainable finance industry to discuss their perspectives and the benefits of the Taxonomy. In-person interviews were preferable as they would foster more in-depth responses. However, due to COVID-19, and considering that all our interviewees were not located around Jönköping, the interviews were conducted online through Zoom. The interviews were recorded in order to get the interviews’ transcripts to facilitate the data sampling process. The interviews were conducted using semi-structured interviews with a mix of open- and close-ended questions. This means that the questions were formulated before the meeting, but the discussions were free-flowing and accompanied with follow-up questions to invite the interviewee to express their thoughts without any unnecessary parameters (Adams, 2015). Our interview questions were based on the five themes identified in the frame of reference: (1) interviewee background, (2) sustainability in finance, (3) EU Taxonomy, (4) greenwashing, (5) our suggested framework (see Table 2). Follow-up questions for each theme were asked to help guide the interview.

Main Theme Follow-up Questions

Interviewee Background

• What is your position at the company you work for?

• What are your roles and responsibilities in this position? Sustainability in

Finance

• Vision: How does the company you work for support investors and the financial system to become more sustainable? Do you use any tools, if yes, which ones?

• Mission: What are your sustainable agendas and their time frame? More about innovative solutions, tools, and research.

• How will it affect your position at the company you work for?

• What is it going to change for you and what do you think of it? EU Taxonomy • Have you heard of the EU Taxonomy?

• How will it affect your position at the company you work for?

• What is it going to change for you and what do you think of it? Greenwashing • How do you identify the problem of greenwashing (lack of

transparency) in the financial sector? How does it differ from the greenwashing that consumers deal with?

• Do you see potential benefits of the EU Taxonomy on greenwashing? If so, how?

Suggested Framework

• We found 6 types of greenwashing that we consider being most impacted by the introduction of the EU Taxonomy. For us to test this framework, we would like to ask you to rank them (1 having the highest potential of being reduced by EU Taxonomy) Table 2: Interview Guide