Elsevier Editorial System(tm) for Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal Manuscript Draft

Manuscript Number: AENJ-D-11-00034R2

Title: Emergency nurses working with Manchester Triage - The impact of nursing experience on patient safety

Article Type: Original Research papers

Keywords: Triage, experience, patient safety, nursing, Sweden. Corresponding Author: Dr. Eric Dan Carlström, Ph.D.

Corresponding Author's Institution: Helath management First Author: Berit Forsman, BSC RN

Order of Authors: Berit Forsman, BSC RN; Susanne Forsgren, BSC RN; Eric Dan Carlström, Ph.D.

Abstract: Background: The article describes triage nurses perception of the impact experience and MTS have on patient safety during MTS triage assessment at emergency departments in Western Sweden. Methods: Data was collected from 74 triage nurses using a questionnaire containing 37 short form questions of Likert type, analyzed descriptively and measured the covariance. Data was also collected with two open questions by using the critical incident technique and content analysis.

Results: The results described that the combination of the MTS method, the nurses' experience and organizational factors accounted for 65% of patient safety. The study indicated that nurses' experience contributed to higher patient safety than the model itself. A standardized assessment model, like MTS, can rarely capture all possible symptoms, as it will always be constrained by a limited number of keywords and taxonomies. It cannot completely replace the skills an experienced nurse develops over many years in the profession.

Conclusions: The present study highlights the value of triage nurse's experience. The participants considered experience to contribute to patient safety in emergency departments. A standardized triage model should be considered as additional support to the skills an experienced nurse develops.

Suggested Reviewers: Opposed Reviewers:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Gothenburg, Sweden 17/1/2012

Australasian emergency nursing journal

Dear Editor

Attached please find a new version of our manuscript for publication in the

Australasian emergency nursing journal. This article focuses on triage assessment in

emergency departments in Western Sweden. The findings in the article indicated that

nurse´s experience contribute to higher patient security than the triage model itself.

Because of its empirical content and development of theory the article is interesting

for both researchers and practitioners. We are sending this article to Australasian

emergency nursing journal as the subject of triage assessment has been dealt with in

the journal previously.

This article has neither been published nor considered for publication in any other

journal.

Yours Sincerely,

Eric Carlström

Berit Forsman

Susanne Forsgren

Contact information:

Eric Carlström

Associate Professor

The Sahlgrenska Academy

University of Gothenburg

and University West, Trollhättan.

Adress: Department of Nursing, Health and Culture.

University West,

SE-461 86 Trollhättan, Sweden,

eric.carlstrom@hv.se

Tel. +46702738126

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61

Nurses working with Manchester Triage

- The impact of experience on patient security

Berit Forsman, BSc, RN Susanne Forsgren, BSc, RN

Eric D. Carlström, PhD, MA, RN1

Susanne Forsgren, is a Lecturer in Emergency Nursing, Department of Nursing, Health and Culture, University West, Trollhättan, Sweden.

Berit Forsman, is a Lecturer in Emergency Nursing, Department of Nursing, Health and Culture, University West, Trollhättan, Sweden.

Eric Carlström is an Associate Professor and Director of Research in Health Management, Policy and Economics, Department of Nursing, Health and Culture, University West, Trollhättan, Sweden.

Keywords: Triage, experience, patient security, nursing, Sweden.

SF, BF and EC conceived and designed the study. SF and BF developed the study protocol. EC, SF and BF designed and tested the study instruments. EC supervised data collection. SF and BF analysed the data. BF, SF and EC prepared and approved the manuscript.

1 Corresponding author: Eric D. Carlström, Department of Nursing, Health and Culture. University West, SE-461 86 Trollhättan, Sweden, E-mail eric.carlstrom@hv.se Tel. +46702738126

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Competing interests

There are neither competing interests nor conflicts of interest. *Provenance and Conflicts of Interest

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 Funding

No founding or research grants were provided. *Funding

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Australiasian emergency nursing journal

(

AENJ) editors and reviewer’s

comments and answers

Title: Emergency nurses working with Manchester Triage - The impact of nursing experience

on patient safety (Ms. Ref. No.: AENJ-D-11-00034).

Dear Editors and anonymous reviewers. We, once again, really appreciate all detailed

comments to the paper.

Below you will find our response to the reviewer’s comments. The revised parts are marked

yellow in the paper.

Thank you for your patience still considering our work

Sincerely

The authors

Editors:

1.We hope to receive a revised manuscript from you by Jan 26,2012 if possible.

We will submit before Jan 26, 2012

2.Please review comments from the reviewer 3 listed below, in particular the issues

Please see below

Reviewer 3

1.Whilst experience is important, one of the flaws of reliance on experience alone or as a

supplement to a objective system is that is it not reproducible between individuals. Experience

can also have a negative effect if there has been no follow through or learning/reflection after

an event. This should be made clear.

Please see line 255. Text has been rewritten and marked yellow

2.What you describe is piloting rather than validation but it provides more detail.

Line 133, the word is changed to piloting

3.I am still not convinced of the need for a formal statistical calculation because you are not

seeking causality and you cannot generalize from the sample selected.

The formal statistical calculation was a part of the methodological proceeding. We have

however tuned down the causality and generalizability of the results somewhat under the

subheading, limitations. Please see new text line 318-322, marked yellow.

4.You state that triage is not a predictive tool-triage is a process of assessment, a tool such as

the MTS may be used to help identify priority. The process is not predictive. MTS or other

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61

such tools are not designed to replace experience they are there to augement and support

decision making. This can be particularly useful with staff of less experience . However

experience does not always protect against poor judgement.

Please see line 247-249 and 255-256, Sentences changed and marked yellow.

5.The word commence is incorrect. I think you mean initial

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Emergency nurses working with Manchester Triage

1

- The impact of nursing experience on patient safety

2

3

Abstract:

4

5

Background: The article describes triage nurses perception of the impact experience and MTS have on patient safety during MTS triage

6

assessment at emergency departments in Western Sweden.

7

Methods: Data was collected from 74 triage nurses using a questionnaire containing 37 short form questions of Likert type, analyzed

8

descriptively and measured the covariance. Data was also collected with two open questions by using the critical incident technique and

9

content analysis.

10

Results: The results described that the combination of the MTS method, the nurses’ experience and organizational factors accounted for 65%

11

of patient safety. The study indicated that nurses’ experience contributed to higher patient safety than the model itself. A standardized

12

assessment model, like MTS, can rarely capture all possible symptoms, as it will always be constrained by a limited number of keywords and

13

taxonomies. It cannot completely replace the skills an experienced nurse develops over many years in the profession.

14

Conclusions:The present study highlights the value of triage nurse’s experience. The participants considered experience to contribute to

15

patient safety in emergency departments. A standardized triage model should be considered as additional support to the skills an experienced

16

nurse develops.

17

18

Keywords: Triage, experience, patient safety, nursing, Sweden.

19

20

What is known about the topic?

21

In previous studies, the need for theoretical triage assessment training is regarded as central to improve patient safety. Alternative forms

22

of training such as practical case exercises can further increase the ability to identify severely ill patients. Nurse´s experience has been shown

23

to improve decision ability, but there is no evidence that triage nurse experience improves decision accuracy in computer based triage cases.

24

25

What this paper adds or contributes?

26

This study highlights the value of experience. Experience contributes to more patient safety than the studied triage model itself.

27

Extensive experience is established over years of assessing severely ill patients. When triage assessment models are used it should be by

28

experienced nurses, skilled in interviewing techniques and clinical diagnosis.

29

Introduction

30

There is an ongoing debate in Sweden about the extent to which the practice of triage contributes to

31

patient´s safety. The debate is based on notification to the Swedish National Social Board where a

32

patient was left in a waiting room with a life threatening condition. Although the triage category was

33

correct according to the decision tool used, the patient's urgent condition wasn’t identified. The

34

criticism outlined was that in situations where assessment models are used, they might strongly

35

influence priority to a greater degree than the triage nurse's experience. 1 When a triage assessment is

36

not consistent with the triage nurse's perception; based on experience, the corresponding model tends

37

to be assigned first priority. If this is the case, the assessment model could be a hindrance and become

38

a real risk to the patient.1, 2, 3The present study describes 74 nurse´s perception of the impact

39

experience and Manchester triage system (MTS) have onpatient safety. Patient safety is defined as to;

40

minimize the risk of patient´s complications or early death as well as to identify the need for hospital

41

care. 4

42

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 Triage models

43

The workload of emergency departments varies according to the number and acuity of the patients.

44

5, 6

An efficient triage system regulate the length of the patients’ waiting times in the emergency

45

department by combining immediate assessments and interventions. 5 In order to properly assess the

46

care patient´s need, triage nurses must understand, identify and evaluate available information from

47

the patient. Triage is intended to ensure that patients are taken care of according to the urgency of the

48

clinical needs rather than the order in which they arrive. 5, 6

49

Modern emergency department triage was developed in Australia, United Kingdom, Canada and

50

USA.7 National Triage Scale (NTS) is a five- point triage scale adopted in Australia 1993/94. The

51

British and Canadian scales are based on this system. The NTS scale was revised in 2000/01 to include

52

the patients’ vital signs and symptoms, and was also renamed Australian Triage Scale (ATS). 8 The

53

need for a triage scale in Canada was described in the early 1970’s, but the scale did not become a

54

reality until the 1990’s, when The Canadian Emergency Department Triage (CTAS) was introduced.

55

CTAS is a scale based solely on the vital signs.9 The Manchester Triage System (MTS) was

56

introduced in the UK in 1996.6 US hospitals currently use a variety of triage scales, the most widely

57

used and dispersed triage system is a scale called Emergency Service Index (ESI). 10 The Cape Triage

58

Score (CTS) was introduced in 2004 in South Africa. It is a scale appropriate for specific problems,

59

which include a large number of people with HIV infections and severe trauma cases.11

60

In Sweden registered nurses work with triage assessment and there is no standard triage available.

61

Currently three different methods are of use; Adaptive Triage (ADAPT), Medical Emergency Triage

62

and Treatment Systems (METTS), and the Manchester Triage System (MTS). ADAPT and METTS

63

are based on subjective parameters combined with vital parameters such as respiratory rate, oxygen

64

saturation in blood, level of consciousness and pulse rate. 4 12

65

MTS has a five-level scale; immediate care, very urgent, urgent, and two levels of not urgent. The

66

highest category level means that gravely ill patients with a life-threatening condition is assigned red

67

and is given immediate care. Patients with very urgent conditions such as ongoing chest pain is

68

assigned category orange and is given care within ten minutes. Urgent cases are assigned category

69

yellow and can wait up to one hour, less urgent patients are assigned category green and can expect a

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

waiting time of up to three hours. Other patients are given a blue triage level. They can wait for four

71

hours. They can also be advised to visit a primary care medical clinic. 6

72

The first step in MTS assessments is when the nurse, responsible for triage chooses a flow chart

73

based on the patient’s reason for contacting the emergency department for example “chest pain”. The

74

chart begins by identifying possible criteria indicating life-threatening conditions for the patient, such

75

as affected breathing, blood pressure or pulse. If none of these conditions exist, the nurse continues

76

along the flow chart asking questions such as; do you have a problem breathing, dyspnea? If the

77

patient describes “pain correlated to breathing” the nurse assigns the patient a yellow category. MTS is

78

considered a sensitive instrument that identifies severely ill patients in need of intensive care.13 90% of

79

the nurse´s assigned patients to exactly the same triage categories in a study using fictive scenarios and

80

MTS. 14

81

Triage and nurses’ experience

82

83

Experience is considered to be an important part of nursing skills.15 In the present study the

84

definition of an experienced nurse, is a nurse who have acquired assessment skills that recognize

85

symptoms and relate symptoms to known disease categories.21 Skills are not based on education alone,

86

the transition into a skilled nurse requires experience that can be acquired during clinical work. 5, 16, 17,

87

18

Triage requires an ability to make independent decisions and a triage nurse is considered to be able

88

to establish trust and confidence with the patient. 19, 20 Dialogue improve trust and confidence between

89

nurse and patient and helps the nurse to collect data about the patient's condition.5

90

91

The ideal triage system should quickly and accurately distinguish patients in need for immediate

92

care and patients able to wait for treatment. 6, 22, 23 Triage scales and assessment levels must be absolute

93

comprehensible.24, 25 Sometimes the MTS model is not sufficient; the nurse has difficulties finding

94

matching keywords to the patient’s subjective parameters or symptoms, which might complicate the

95

assessment. 26

96

If the patient is assigned a lower triage priority than required the patient’s health may be

97

jeopardized, however, an over-triage can contribute to a less than optimal use of the emergency

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 department’s resources.24, 27

The triage nurses interview technique and the ability to make accurate

99

clinical observations contributes to patient safety.3 In order to reach an accurate priority quickly, the

100

length of the interview and added examinations must be limited. Time-consuming assessments are

101

balanced with the need to correctly identify a severely ill patient. A misjudgment can lead to unwanted

102

consequences due to incorrect triage category.23 Prioritizing requires a sufficient basis for evaluation,

103

the nurse must learn techniques to get the patient to focus on their symptoms and pass on relevant

104

information.28 A common cause of error is a conversation that is too superficial.28, 29

105

Experience has proven to contribute to accurate triage assessments 30. Nurses who regularly practice

106

triage, have proven to be those who make the best decisions.30 However, clinical experience do not

107

always make a significant difference.31 Risks may arise if a nurse generalizes his or her evaluation of

108

the patient's condition, comparing it with previous cases without considering alternative possibilities.

109

The nurse might make hasty assumption, “locks on the target” and acts within a limited set of data.

110

The potential risk of hasty assumptions underpins the need to meet every patient without bias. 32

111

Method

112

113

Questionnaires were sent to 102 triage nurses in four emergency departments in Western Sweden

114

working with MTS. All informants were registered nurses, working with MTS triage assessment only

115

during regular periods of their work schedule for at least six months. The supervisors at each

116

respective emergency department gave permission to approach staff to the research area.

117

The questionnaire design

118

119

A questionnaire was chosen as the best method for conducting the initial investigation to describe

120

the impact of emergency nurses' experience during MTS triage assessment on patient safety .The

121

instrument was designed by the authors to provide a possibility to answer the research question. The

122

survey included nurses basic demographic details; age, work experience, years working with triage

123

assessment, the education level and additional medicine courses. Other areas were job satisfaction

124

related to their nursing work at the ED, such as interesting and stimulating task, possibilities to take

125

initiative and to act independently.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Questions about their job satisfaction related to their triage assessment task, such as additional

127

triage training, triage organization and attitudes to the MTS and patient safety. The questionnaire

128

contained 37 questions with five possible Likert type answers. 35 Data was also collected with two

129

open questions using the Critical Incident Technique (CI). The informants were asked to describe two

130

triage assessment scenarios in text - one which they thought was satisfactory and one which they

131

thought was unsatisfactory (see appendix).

132

The instrument was piloted by five nurses responsible for triage assessment at respective

133

emergency departments. The purpose was to test the questionnaire on a small group of volunteers, as

134

similar as possible to the target group.36,37 This led to small adjustments to clarify some of the

135

questions.

136

A power calculation was performed before the study. With a power of 75%, and given the number of

137

included predictors (i.e. an alpha value at 0.05) a total of 70 participants were needed to be included in

138

the study.33,34 The instrument’s internal reliability was tested by calculating Cronbach’s alpha. The

139

results varied between 0.68 and 0.84, which is considered to be variable but satisfactory3,40

140

39

Questionnaires were numbered and the variables were defined and fed into the computer program,

141

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 14.0.34 Statistical Significance was established at p

142

< 0.05. The quantitative part of the analysis consisted of descriptive data, bivariate and multivariate

143

regressions. The CI was used to capture the informants’ views on the triage assessment. The technique

144

focuses on a factual incident, which may be defined as observable and integral episode of human

145

behavior. The incident must have had an impact on some outcome; it must have either a positive or

146

negative contribution to the accomplishment of some activity of interest.15, 42 The qualitative analysis

147

meant that the obvious part of the answers was extracted from each respective question. 43

148

149

Ethics

150

151

The study complied with ethical procedures according to Swedish law, 44 and the Declaration of

152

Helsinki.45 Participants fulfilling the inclusion criterions was included with the help from senior

153

managers and by the human resource departments. The questionnaire contained an introductory letter

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61

where the background of the study was described. It contained detailed instructions and information

155

stating that participation was voluntary. Participants were informed that they were free to withdraw at

156

any time. They were assured of strict confidentiality and secure data storage. Swedish statutes do not

157

require ethics approval for research that does not involve a physical intrusion that affects the

158

participants.44159

Results160

161

The survey response rate was 75%. The age of the informants were evenly distributed between 25

162

and 64, most of the nurses (25%) was between 35- 44 years. Sixty three percent of the nurses who

163

participated in the study had more than five years’ nursing experience, and 70% had practiced MTS

164

for more than a year. Sixty two percent of the triage nurses had undergone a one-day MTS training

165

course. Thirty percent had studied trauma care at university level. Only one of the nurses had been to

166

university to specialize in triage.

167

When asked if their employers had offered them any on-the-job additional triage training besides

168

the MTS introduction over the past six months, 20% of the nurses answered yes. The additional

169

training included briefings about fictitious patient cases and different triage situations. Sixty one

170

percent expressed a need for initial and additional triage training. Of these 46% felt that they

171

specifically needed more training on simulated patient cases.

172

The questionnaire contained questions concerning the nurse´s personal attitudes, to experience,

173

reliability and patient safety regarding triage assessments using the MTS method. There were 70% of

174

the informants that felt the need for experience. Seventy-eight of the informants thought that MTS was

175

patient safe and 77% thought that it was a reliable method. Asked if the nurses were given sufficient

176

time for the triage assessment 90% of the nurses answered yes. Sixty one percent had sufficient time

177

for analysis and 66% gained support for the task and cooperation at the ED.

178

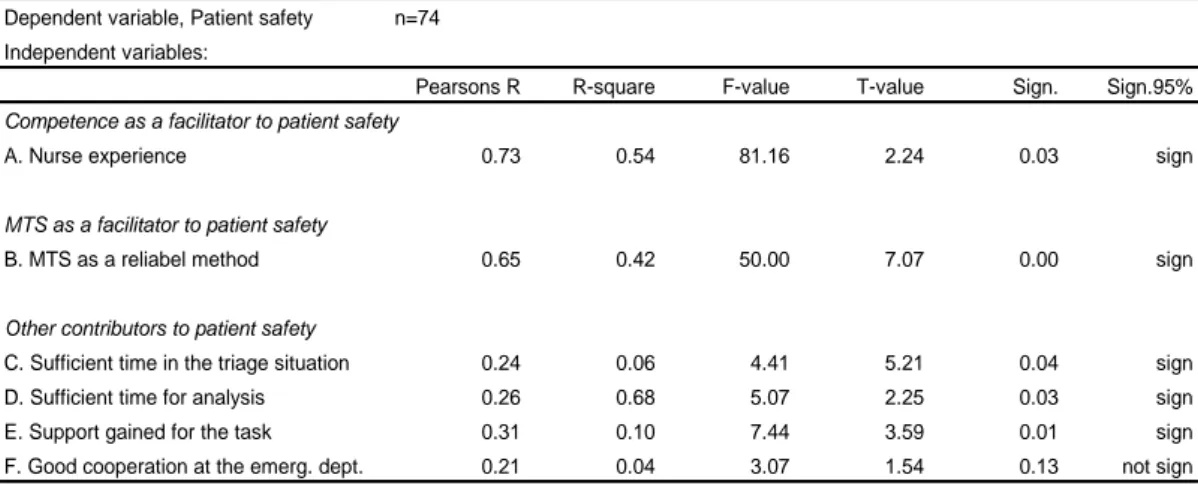

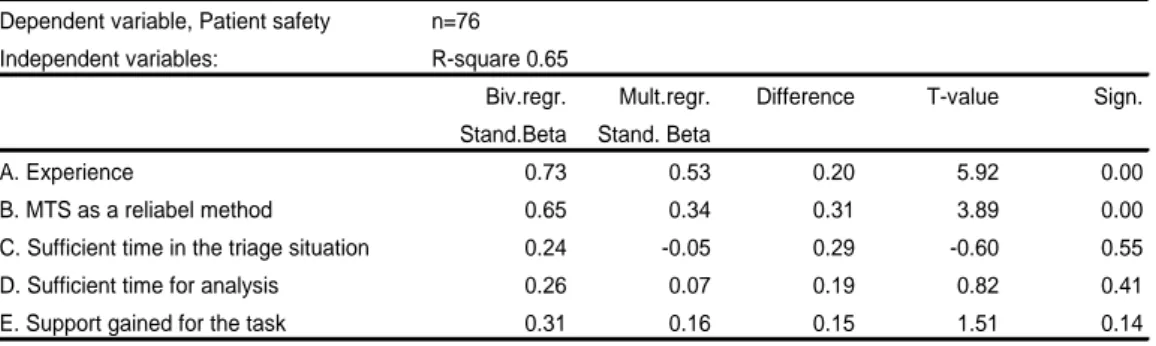

The relationship between the participant’s perception of the impact of MTS and nursing experience

179

on patient safety was tested in a number of bivariate regressions. The MTS triage model was

180

considered to contribute to patient safety (R = 0.65, R2 = 0.42). The triage nurse's skills as a result of

181

experience were however considered to be even more valuable. Experience was considered to improve

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

the patient’s safety (R = 0.73, R2 = 0.54). The patient safety was considered to increase the longer the

183

nurse had worked with triage (R = 0.33, R2 = 0.11).

184

Additional contributors to patient safety than nursing experience were found in the data. Patient

185

safety was considered to increase slightly when the nurse had enough time for assessment (R = 0.24,

186

R2 = 0.06) and enough time for subsequent analysis (R = 0.26, R2 = 0.68). If the organization offered

187

peer support to the triage nurse, patient safety was considered to increase even more (R = 0.31, R2 =

188

0.10) (tab:1).

189

Table 1: The importance of nurse´s experiences, MTS and other contributors as a determinant of patient safety,bivariate regression.

190

191

A multiple regression showed that nurses' skills, MTS as a method, and organizational factors

192

together accounted for 65% of patient safety (R2 = 0.65). This meant that 35% remained unexplained.

193

Two variables were still significant, nurse’s experience, and MTS as a method. The remaining

194

variables displayed low t-values, and were lacking significance on their own. The reason could be that

195

they co-variate or that they were present as an earlier link in connection to the cause. Results indicate

196

that experienced nurses combined with sufficient time for assessment and analysis while working with

197

MTS contributes to patient safety (tab.2).

198

Table 2: The importance of nurse´s experiences, MTS and other contributors as a determinant of patient safety,multiple regressions.

199

Table 1 Bivariate regression

Dependent variable, Patient safety n=74 Independent variables:

Pearsons R R-square F-value T-value Sign. Sign.95% Competence as a facilitator to patient safety

A. Nurse experience 0.73 0.54 81.16 2.24 0.03 sign

MTS as a facilitator to patient safety

B. MTS as a reliabel method 0.65 0.42 50.00 7.07 0.00 sign

Other contributors to patient safety

C. Sufficient time in the triage situation 0.24 0.06 4.41 5.21 0.04 sign D. Sufficient time for analysis 0.26 0.68 5.07 2.25 0.03 sign E. Support gained for the task 0.31 0.10 7.44 3.59 0.01 sign F. Good cooperation at the emerg. dept. 0.21 0.04 3.07 1.54 0.13 not sign

Table 2 Multiple regression

Dependent variable, Patient safety n=74 Independent variables: R-square 0.65

Biv.regr. Mult.regr. Difference T-value Sign. Stand.Beta Stand. Beta

A. Nurse experience 0.73 0.53 0.20 5.92 0.00

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61

200

Open questions201

202

The results of the quantitative part of the study were confirmed by the answers to the open

203

questions in the survey. Fifteen of the nurses gave comments on the positive value of MTS. They

204

argued that the method contributed to patients being cared for safely. When the nurse and the patient

205

met, the conversation was normally held in an environment characterized by peace and quiet, where

206

the nurses' communication skills were used optimally. Patients were rapidly assessed, even if the

207

workload was high. One nurse also stated that the model contributed to early finding and identifying

208

patients with life-threatening conditions.

209

210

“During triage you can directly identify patients with severe symptoms. One can quickly bring

211

them into the emergency room and start the assessment.”

212

213

“A patient with minor subjective symptoms was examined in the emergency room but had a high

214

pulse rate. It did not seem so serious but MTS gave him a high priority and the patient was taken care

215

of faster than usual. It was fortunate because the patient had a ventricular fibrillation shortly

216

afterwards and his life was saved.”

217

218

“The patient had an undefined chest pain, which we thought was nothing serious, but it turned out

219

to be a heart attack. I am glad that such discomforts are given a high priority.”

220

221

There were also critical voices expressing that MTS was sometimes a hindrance to patient safety.

222

They could not find matching keywords or flow charts to substantiate their decisions. They regarded

223

the model as sometimes “ambiguous”, which could make it hard to identify serious conditions. One

224

nurse described an unsatisfactory triage assessment;

225

226

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

“A patient arrived suffering from mild abdominal pain. He had different blood pressures in his

227

arms. There was no keyword for this. The patient was given low priority because he had almost no

228

pain when arriving at the emergency room. Fifteen minutes after arrival the patient was dead. He died

229

of an aortic aneurysm, despite intensive CPR.”

230

231

Experienced nurses could sometimes have a “gut feeling” or intuition that something important had

232

been missed in the assessment. The MTS however, gave no scope of action for this. The model was

233

based on observations sorted under a limited number of headings. When the nurse’s perception did not

234

agree with the triage model they sometimes chose not to express their concerns. The nurses did not

235

want to appear to be unclear or vague in their assessment. However, in some cases the nurses assessed

236

according to their “gut feeling” in order to safely care for the patient

237

238

"When my intuition says that the patient should have a higher priority than MTS provides, it makes

239

me feel uncomfortable. It is a situation that is difficult to manage.”

240

241

“Sometimes, patients have many different symptoms. After a short conversation, I usually give a

242

higher priority to these patients, because I know they cannot manage to sit and wait for a long time in

243

the waiting room.”

244

Discussion

245

The informants in this study stated that a standardized assessment model, like MTS rarely captures

246

all possible symptoms. MTS as a tool will always be constrained by a limited number of keywords and

247

taxonomies. It may be used to help identify priority and give support in decision making, but it seems

248

unlikely to replace the skills an experienced nurse develops over many years in the profession.

249

Identifying pattern recognition, intuition and “gut feeling” is the hallmarks of nursing. Repeated

250

exposure to certain conditions gives nurses’ confidence in their abilities to recognize potential danger

251

areas.On the other hand, an experienced nurse sometimes has a tendency to associate the patient’s

252

needs to a simplified classical condition and hence determine a priority level too quickly. They could

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61

thus rely on their experience and “lock on the target” by failing to carry out additional checks to

254

confirm the assessment. Experience can have a negative effect on nurse´s if there has been no follow

255

through or reflection after a serious event. It is important for nurses to question their experience and

256

meet each patient openly and unbiased.32 The nurses in present study reported while using MTS they

257

discovered subtle but serious symptoms that could otherwise have been missed. Both of these risks,

258

the limitation of MTS to identify serious conditions, as when a patient arrived suffering from mild but

259

lethal abdominal pain and on the other hand, nurses who performed the assessment too quickly and

260

assigned an incorrect priority – might be prevented by combining the model's benefits with an

261

experienced nurse's abilities (Fig. 1).

262

263

Fig.1264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

Comments fig. 1.The figure shows three types of triage assessments based on the nurse's experience and MTS. A is representing a

272

combination of experience and MTS. In position A it is probable that the patient will be properly assessed. B is based on experience and C on

273

the model's keywords and taxonomies. Both B and C decrease the patient safety. At B, generalizations can be made. The nurses can rely in

274

their own experience and make a hasty prioritization, associating the patient’s condition with a classical condition. At C, the model leads to

275

problems in assessing patients correctly because of the lack of keywords. B can decrease the risk by using the work processes of the

276

standardized model, and the risk of C can be prevented by the nurse’s experience.

277

278

When excessive influence is given to MTS, the experienced nurses’ ability to convey a “gut

279

feeling” or intuition could be hampered. The “gut feeling” or intuition is a synthesis of all information

280

the nurses register implicitly. Such information is for example; a visual, auditory or a tactile

281

impression associated with previously experienced situations and events.46The nurses in this study

282

were not always able to describe the association, or put it into words at that moment, but the reaction

283

is still valid and the signals are often important to the triage assessment. This phenomenon has been

284

A

C

B

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

termed “tacit knowledge”, knowledge based on experience 46

which cannot be classified in an explicit

285

triage model. Nurses’ concerns that seem vague or evasive may contribute to key findings being

286

ignored. 41 If a standard triage model is given such a superior dominance that no objection can be

287

raised against its taxonomies, the nurse's experience will be neglected. Such a situation can reduce the

288

safety of the patient. The results of this study indicated that a nurse’s experience contributed to higher

289

patient safety than the model itself. This means that if the opportunity to object to the model is

290

reduced, patient safety will be significantly reduced. A triage model should therefore be considered as

291

additional support in order not to miss serious conditions. On the other hand, MTS contributed to

292

increased patient safety because the scheme reduced the risk of missing important parameters in the

293

assessment. The risk of the nurse missing serious conditions was reduced because the model forced the

294

nurse to ask key questions and make vital inquiries.

295

In previous studies regular training develops the triage nurses ability to identify the patient´s degree

296

of urgency and was regarded central to improve patient safety. 48 49, 50, 20, 32, 51, 52 Present study

297

highlights the value of experience. Although training is important, inexperienced nurses should not

298

perform triage assessments without appropriate supervision, even if they are well educated. 49

299

Experience is established through years of assessing severely ill patients. An alternative form of

300

training, which may contribute to acquiring experience, is practical case exercises, because this

301

training can increase the ability to identify severely ill patients. 53 When standardized assessment

302

models are used, they must be combined with skills in interviewing techniques and experience in

303

clinical diagnosis, which is acquired through hands-on exercises.23

304

Strengths and Limitations

305

306

This study highlights the value of experienced nurses performing triage. Experience seems to

307

contribute to more patient safety than the studied triage model itself. Extensive experience such as

308

interviewing techniques and clinical diagnosis is established over years of assessing severely ill

309

patients. It should also be possible to question the priority that a standardized triage model indicates.

310

The limitations in the present study include the fact that the findings may not be able to be

311

generalized to emergency departments outside Western Sweden. Although 74 nurses from four

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61

suburban and urban emergency departments and trauma centers participated in the study, hospital

313

emergency departments from other parts of Sweden were not included. This study only describes

314

nurses working with MTS.

315

The fact that the study is based on a questionnaire measuring the perceived effects of experience

316

and MTS on patient safety can be considered as limitation. When analyzing results based on a

317

questionnaire a possibility of over- or underreporting cannot be ignored. In order to verify the

318

causality and generalizability of the results a study not just based on a questionnaire should be

319

performed. A study of the effects of experience versus triage models on the health status of patients

320

treated in emergency departments would give additional and important information.

321

A third limitation might be the fact that the informant´s descriptions of their critical incidents

322

related to the triage assessment are only short stories. A possibility to perform personal interviews 43

323

on the nurse´s perception of patient safety would have been valuable to the study.

324

325

In this study triage nurse’s experience proved to contribute to patient safety in emergency

326

departments. However, an experienced nurse might fail to notice important parameters through

over-327

reliance on his or her own reasoning. On the other hand, there is a risk that triage models may miss a

328

patient’s serious condition. Experience together with MTS minimizes the risk of patient´s

329

complications or early death as well as to identify the need for hospital care.4

330

Competing interests

331

332

There are neither competing interests nor conflicts of interest.

333

Funding

334

335

No founding or research grants were provided.

336

Acknowledgements

337

338

We would like to thank all of the emergency nurses who completed the survey.

339

340

341

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

References

342

343

1. Nyman U, Hellekant C. Har triagesköterskorna adekvat utbildning? Available at:

344

http://www.lakartidningen.se/includes/07printArticle.php?articleId=9845. Accessed June

345

12, 2011

346

2. Widgren BR, Örninge P, Grauman S, Thörn K. Akutvården säkrare och effektivare med

347

gemensamma metoder. Available at:

348

http://ltarkiv.lakartidningen.se/2009/temp/pda37415.pdf Accessed June 11, 2011

349

3. Forsgren S, Forsman B, Carlström E. Working with Manchester triage- job satisfaction in

350

Nursing. International Emergency Nursing 2009; 17: 226-32.

351

4. Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment (SBU): Triage and flow charts.

352

Available at:

http://www.sbu.se/sv/Publicerat/Gul/Triage-och-flodesprocesser-pa-353

akutmottagningen/ Accessed March 23, 2011

354

5. Grossman VGA. Quick Reference to Triage. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;

355

2003.p.3-20.

356

6. Mackway- Jones K, Marsden J, Windle J. Emergency triage- Manchester Triage Group.

357

London: BMJ publishing group; 1997. p. 1-50.

358

7. Burr G, Fry M. Review of the Triage Literature: Past, Present, Future? Australian Emergency

359

Nursing Journal 2002; 5: 33-8.

360

8. Australian college for Emergency Medicine policy document. Emergency Medicine 2002; 14:

361

335-6.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61

9. Murray M, Bullard M, Grafstein E. Revisions to the Canadian Emergency Department

363

Triage and Acuity Scale Implementations Guidelines. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine

364

2004; 6: 421-7.

365

10. Agency for Health care research and Quality. Emergency severity index version 4

366

implementation handbook. Available at: www.ahrg.gov/research/esi/esihandbk.pdf.

367

Accessed February 3, 2011

368

11.Wallis LA, Gottschalk SB, Wood D, Bruijns S, de Vries S, Balfour C. The Cape Triage Score

369

- a triage system for South Africa. South African Medical Journal 2006; 96: 53-6.

370

12. Olsson T, Terent A, Lind L. Rapid Emergency Medicine Score can predict long-term

371

mortality in nonsurgical emergency department patients. Academic Emergency Medicine 2004;

372

10: 1008-13.

373

13. Cooke MW, Jinks S. Does the Manchester triage system detect the critically ill? Journal of

374

Accident and Emergency Medicine 1999; 16: 179-81.

375

14. Versloot SM, Liutde J. The Agreement of the Manchester triage system and the

376

Emergency Severity Index in Terms of Agreement: A Comparison. Academic Emergency

377

Medicine 2007; 14: 57.

378

15. Sandberg J, Targama A. Ledning och förståelse: - ett kompetensperspektiv på

379

organisationer. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 1998. p. 73-5.

380

16. Chung J. An exploration of accident and emergency nurse experiences of triage decision

381

making in Hong Kong. Accident and Emergency Nursing 2005; 13: 206-13.

382

17. Ritchie J, Aldridge Crafter N, Little A. Triage Research in Australia: Guiding Education.

383

Australian Emergency Nursing Journal 2002; 5: 37-41.

384

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

18. Considine J, Hood K. A study of the effects of the appointment of a Clinical Nurse

385

Educator in one Victorian Emergency department. Accident and Emergency Nursing 2000; 8:

386

71-8.

387

19. Cone KJ, Murray R. Characteristics, Insights, Decision making, and Preparations of ED

388

Triage Nurses. Journal of Emergency Nursing 2002; 28: 401-6.

389

20. Göransson K, Ehrenberg A, Ehnfors M. Triage in emergency departments: national

390

survey. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2005; 14: 1067-74.

391

21. Benner P, Tanner C. How Expert Nurses Use Intuition. AJN-The American Journal of

392

Nursing 1987; 87: 23-34.

393

22. Öhlén G. Akutsjukvården kan få ett uppsving 2008. Läkartidningen. 2008; 4: 194-5.

394

23. Nyström M, Herlitz J. Möte mellan två kunskapsområden. In: Suserud BO, Svensson L,

395

editors. Prehospital akutsjukvård. Stockholm: Liber AB; 2009.p.13-21.

396

24. Fernandes C, Tanabe P, Gilboy N, McNair R, Rosenau A, Sawchuk P. et al: Five- level

397

triage: A Report from the ACEP/ENA Five-Level Triage Task Force. Journal of Emergency

398

Nursing 2005; 31: 339-50.

399

25.Travers D, Waller A, Bowling M, Flowers D, Tintinalli J, Hill C. Five- Level Triage System

400

More Effective Than Three- Level in Tertiary Emergency Departments. Journal of Emergency

401

Nursing 2002; 28: 395- 400.

402

26. Olofsson P, Gellerstedt M, Carlström E. Manchester Triage in Sweden-Interrater

403

reliability and accuracy. International Emergency Nursing 2009; 3: 143-8.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61

27. Considine J, LeVasseur S. The Australian triage scale: examining emergency department

405

nurses performance using computer and paper scenarios. Annals of Emergency Medicine 2004;

406

44:516-523.

407

28. Hjelm NM. Benefits and drawbacks of telemedicine. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare

408

2005; 11:60-70.

409

29. Eldh AC, Ekman I, Ehnfors M. Conditions for Patient Participation and Non-

410

Participation in Health Care. Nursing Ethics 2006; 13:503-14.

411

30. Chioffi, J. Triage decision making: educational strategies. Accident & Emergency Nursing

412

1999; 7: 106-111.

413

31. Cone K. The development and testing of an instrument to measure decision making in

414

emergency department triage nurses. Faculty of the Graduate School Missouri; St Louis

415

University; 2000.

416

32. Hamilton S. Clinical decision making: thinking outside the box. Emergency nurse 2004; 12:

417

18-21.

418

33. Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis

419

for the behavioral sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003.

420

34. Sjöberg L. Methods and practice of psychological research: three disasters. VEST: Journal

421

for Science and Technology Studies 1999; 12: 5-25.

422

35. Trost, J. Enkätboken. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2001. p. 158-9.

423

37. Teijlingen van E, Rennie AM, Hundley V, Graham W. The importance of conducting and

424

reporting pilot studies: the example of the Scottish Births Survey. Journal of Advanced Nursing

425

2001; 34: 289-95.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

38. Baker TL. Doing Social Research (2nd Edn.), New York: McGraw-Hill Inc. 1994

427

39. Bosma H, Marmot MG, Hemingway H, Nicholson AC, Brunner E, Stansfield SA. Low job

428

control and risk of coronary heart disease in Whitehall ll. British Medical Journal 1997;

314:517-429

23.

430

40. Bland JM, Altman DG. Stastistic notes: Cronbach´s alpha. British Medical Journal

431

1997;314:558-65.

432

41. Brace N, Kemp R, Snelgar R. SPSS for Psychologists. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

433

2006. p. 331-6.

434

42. Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. London: Chapman & Hall.

435

1997.p.277, 320-1.

436

43. Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing Research- Principles and Methods. Philadelphia. Lippincott

437

Williams & Wilkins. 2004. p. 344-5.

438

44. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Quality content analysis in nursing research: concepts,

439

procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today 2003; 24: 105-12.

440

45. The Swedish Code of Statutes: Act concerning Ethical Review of Research involving

441

Humans. Available at:

442

http://www.riksdagen.se/webbnav/index.aspx?nid=3911&bet=2003:460. Accessed

443

February 7, 2011

444

46. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical

445

Research Involving Human Subjects. Available at: http://www.wma.net Accessed

446

December 6, 2010

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61

47. Herbig B, Büssing A, Ewert T. The Role of Tacit Knowledge in the Work Context of

448

Nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2001; 34: 687-95.

449

48. Meerabeau L. Tacit nursing knowledge: an untapped resource or a methodological

450

headache? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2006; 34: 687-95.

451

49.Atack A, Rankin J, Then K. Effectiveness of a 6-week Online Course in the Canadian

452

Triage and Aquity Scale for Emergency Nurses. Journal of Emergency Nursing 2005; 31: 436-41.

453

50. Considine J, Hood K. A study of the effects of the appointment of the Clinical Nurse

454

Educator in one Victorian Emergency Department. Accident and Emergency Nursing 2000; 8:

455

71-8.

456

51. Considine J, LeVasseur S, Villanueva E. The Australian Triage Scale: Examining

457

Emergency Department Nurses Performance Using Computer and Paper Scenarios. Annals

458

of Emergency Medicine 2004; 44:516-23.

459

52. Ritchie J, Aldridge Crafter N, Little A. Triage Research in Australia: Guiding Education.

460

Australian Emergency Journal 2002; 5:37-41.

461

53. Stuhlmiller C, Tolchard B, Lyndall T, Crespigny C, Kaluncy R, King D. Increasing

462

confidence of emergency department staff in responding to mental health issues: An

463

educational initiative. Australian Emergency Nursing Journal 2004; 7: 9-17.

464

54. Tippins E. How Emergency Department Nurses Identify and Respond to Critical Illness.

465

Emergency nurse 2005; 13: 24-33.

466

467

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

APPENDIX: Questionnaire (reduced and translated from Swedish, likert scales not

469

presented)

470

471

Demographics472

Your Age? For how long have you been working as registered nurse?

473

For how long have you been working with triage assessment?

474

475

Work contentment in general

476

Do you find your work interesting?

477

Do you find your work stimulating?

478

Are you given opportunities to take initiatives at your work?

479

Are you able to make your own decisions at work?

480

Is it your opinion that; “you have a good work environment”?

481

482

Educational level

483

Have you attended and /or graduated from any additional medical courses?

484

Have your employer offered you any additional training in triage during the last six months?

485

Have you attended any additional training based on simulated patient cases?

486

Do you feel the need for commence and additional triage training – generally?

487

Do you feel the need for commence and additional triage training based on simulated patient cases?

488

489

General attitudes related to triage

490

Is it your opinion that: A triage nurse should possess certain characteristics?

491

If often or sometimes: Give an example

492

Is it your opinion that: A triage nurse should possess these characteristics (in order to minimize patient

493

complications or early death as well as to identify the need for hospital care)?

494

Triage assessment is a nursing task? If never or seldom: Explain…

495

496

Working conditions related to the triage assessment task

497

What was your attitude towards the implementation of Manchester triage?

498

Is it our opinion that:

499

You get sufficient time to evaluate and interpret the information you get from the patient

500

You have sufficient time to evaluate the triage decision

501

You get support gained for the task (from your colleagues and staff at the ED)

502

You have a good cooperation with all the other staff when you are responsible for the triage task

503

504

MTS the method

505

Is it our opinion that:

506

It is difficult to use the Manchester triage system

507

The MTS is a reliable method

508

MTS minimize patient complications or early death as well as to identify the need for hospital care?

509

Every (all nurses) can learn how to practice MTS

510

Not every nurse is suited to work with triage

511

Any nurse can, by training, become more competent in their triage assessment task

512

513

Work satisfaction related to the triage assessment

514

Is it our opinion that:

515

There is a need for triage at your ED

516

Manchester triage is the key to (lead to) a more “prompt” care of the patient

517

The patients are more content after the implementation of Manchester triage

518

It is patient safe to work /perform according to MTS

519

520

Describe a triage assessment that you perceive satisfactory

521

Describe a triage assessment that you perceive as unsatisfactory

522

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61

523

524

525

526

527

528

529

530

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Table 1 Bivariate regression

Dependent variable, Patient safety n=76 Independent variables:

Pearsons R R-square F-value T-value Sign. Sign.95%

Competence as a facilitator to patient safety

A. Experience 0.73 0.54 81.16 2.24 0.03 sign

MTS as a facilitator to patient safety

B. MTS as a reliabel method 0.65 0.42 50.00 7.07 0.00 sign

Other contributors to patient safety

C. Sufficient time in the triage situation 0.24 0.06 4.41 5.21 0.04 sign

D. Sufficient time for analysis 0.26 0.68 5.07 2.25 0.03 sign

E. Support gained for the task 0.31 0.10 7.44 3.59 0.01 sign

F. Good cooperation at the emerg. dept. 0.21 0.04 3.07 1.54 0.13 not sign

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61

Table 2 Multiple regression

Dependent variable, Patient safety n=76

Independent variables: R-square 0.65

Biv.regr. Mult.regr. Difference T-value Sign.

Stand.Beta Stand. Beta

A. Experience 0.73 0.53 0.20 5.92 0.00

B. MTS as a reliabel method 0.65 0.34 0.31 3.89 0.00

C. Sufficient time in the triage situation 0.24 -0.05 0.29 -0.60 0.55

D. Sufficient time for analysis 0.26 0.07 0.19 0.82 0.41

E. Support gained for the task 0.31 0.16 0.15 1.51 0.14

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Fig.1.

B

C

A

experience

triage model

Ethics

The study complied with ethical procedures according to Swedish law, and the Declaration of Helsinki.Participants in the intervention group were selected by senior managers and by the human resource departments. The survey contained an introductory letter where the background of the study was described. It contained detailed instructions and information stating that participation was voluntary. Participants were informed that they were free to withdraw at any time. They were assured of strict confidentiality and secure data storage. Swedish statutes do not require ethics approval for research that does not involve a physical intervention that affects the participants.