Understanding Institutional Influences on Environmental and

Social Responsibility in Family-Run Wineries

A look at US and Hungarian CSR practices

Brandie Still & Veronika Thernesz

Main field of study – Leadership and Organization

Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organization Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organization for Sustainability

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Malmö University Urban Studies department for their guidance and counsel during the development of this thesis. We are incredibly grateful for the supervision provided by our supervisor, Jonas Lundsten, throughout the process. We would like to express gratitude to the wineries in the United States and Hungary, which provided time and energy for our interviews, making this research possible. We are inspired by our fellow SALSU students with whom we shared our educational experience this past year. We are encouraged to know that so many people care to take on leadership roles to further sustainability efforts throughout the world for future generations.

November 2020

Malmö, Sweden

Malmö University, Department of Urban Studies

Master’s Programme in Leadership for Sustainability

Researchers: Brandie Still – Veronika Thernesz

Supervisor: Jonas Lundsten

Abstract

Purpose – The purpose of the research is to explain how and why the internal and external influences

faced by family-run wineries affect their CSR practices and communication through institutional theory and stakeholder theory.

Methodology – Ten wineries were analyzed in winemaking regions in Hungary and the US, of which

nine semi-structured interviews were undertaken with family members and employees. The research available implies that family-run businesses within the wine industry are regulated by institutionalism (Brundin & Wigren-Kristoferson, 2013). Therefore, institutional theory is applied to the analysis of the data. The lens of institutional theory uses three pillars, regulatory, normative, and cultural cognitive to identify the external and internal influences on these businesses. Thematic analysis was utilized to code and analyze the data. In addition, the content of each interviewed winery is examined using thematic analysis. Thematic analysis is also applied to content provided on each winery’s website to back up the data.

Findings –In Hungary, the use of sustainable production methods in wineries is part of the winemakers’

personal value system. In the US, wineries have a fierce commitment to the land. In recent years they have worked hard to communicate their sustainability practices. Winegrowers have incorporated modern and old-school practices addressing sustainability issues to meet the expectations of all stakeholders.

Through institutional theory, it has been demonstrated that numerous drivers are influencing family-run wineries to implement environmental and social sustainability practices. However, there is a significant difference between these CSR practices and the need to communicate them between Hungary and the US.

There is a significant difference between the communication methods of Hungarian and US wineries. In Hungary, there is little communication of sustainability practices, although there is movement towards more communication about sustainability practices since the introduction of the web and social media. The experience, in general, was that instead of communication, the emphasis is put more on living and working according to the principles of sustainability – whether it is environmental, social, or economic. In the US, the communication of CSR is used as a marketing tool to engage and educate their stakeholders, mainly through social media.

Research implications –The implications of our research contribute to the knowledge of corporate

social responsibility and how institutional influences affect social and environmental responsibility within family-run wineries by bringing the wine industry, family businesses, and CSR together under the analysis of institutional theory. The findings in this paper should be looked upon by family wineries as a resource related to the current communication of social responsibility in the wine industry.

Research limitation – A limitation of this research is the lack of personal meetings with interviewees.

Due to the COVID-19 lockdowns, the possibility of conducting the interviews face-to-face was not an option. The researchers were challenged to obtain more personal information about the familial, organizational structure without conducting multiple interviews, building trust and rapport.

Keywords – wine, sustainability, family-run businesses, winery, wine industry, social responsibility,

Table of Contents

1 Introduction...1

1.1 Background...1

1.1.1 History and tradition of winemaking ...1

1.1.2 Family businesses ...3

1.1.3 Corporate social responsibility (CSR) ...4

1.2 Previous Research ...5

1.3 Research problem and aim ...5

1.4 Purpose ...6

1.5 Research questions ...6

1.6 Structure of the research paper ...7

2 Theoretical framework ...8

2.1 Institutional Theory ...8

2.1.1 The institution of family-run businesses ...8

2.1.2 Regulatory pillar...9

2.1.3 Normative pillar ...9

2.1.4 Cultural - cognitive pillar ...10

2.2 Stakeholder theory in sustainability ...10

2.3 Corporate social responsibility framework (CSR) ...11

3 Methodology ...13

3.1 Research design ...13

3.2 The sample population ...13

3.3 Method of data collection...14

3.3.1 Interview guide...14

3.3.2 Semi-structured interviewing ...15

3.4 Data analysis...16

3.5 Limitations...16

3.6 Reliability and validity ...17

4 Findings and analysis...18

4.1 Legitimacy through governance ...18

4.2 Responsibility to stakeholders...21

4.3 Legitimacy through values and norms ...23

4.4 Motivations leading to life in a family-run winery ...25

5 Discussion...28

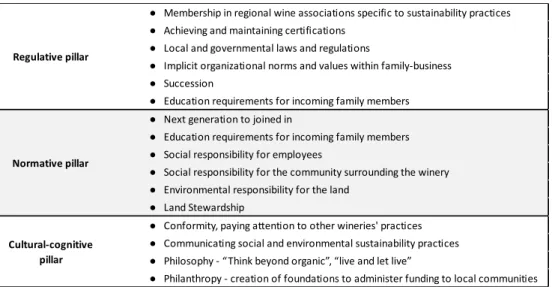

5.1 Influences on wineries and the three pillars ...28

5.1.1 Regulatory pillar...28

5.3.1 Economic CSR ...35

5.3.2 Ethical CSR...35

5.3.3 Moral CSR ...36

5.3.4 Rational CSR...36

5.4 Certified B Corporations – an alternative to CSR ...37

5.5 Addressing Covid-19...37

5.6 Summary of the research questions...37

Conclusion...39

Theoretical contribution and implications ...39

Recommendations...40

References ...41

Appendix A Interview guide...45

Appendix B Confidentiality & Consent ...46

Appendix C Previous research...47

Appendix D Codebook ...48

List of Tables

Table 1. Summary of selected sample and method of data collection ...14Table 2. Four most prevalent themes and association with theories in the research ...18

Table 3. Generations working together...20

Table 4. Examples of institutional theory ...33

List of Figures

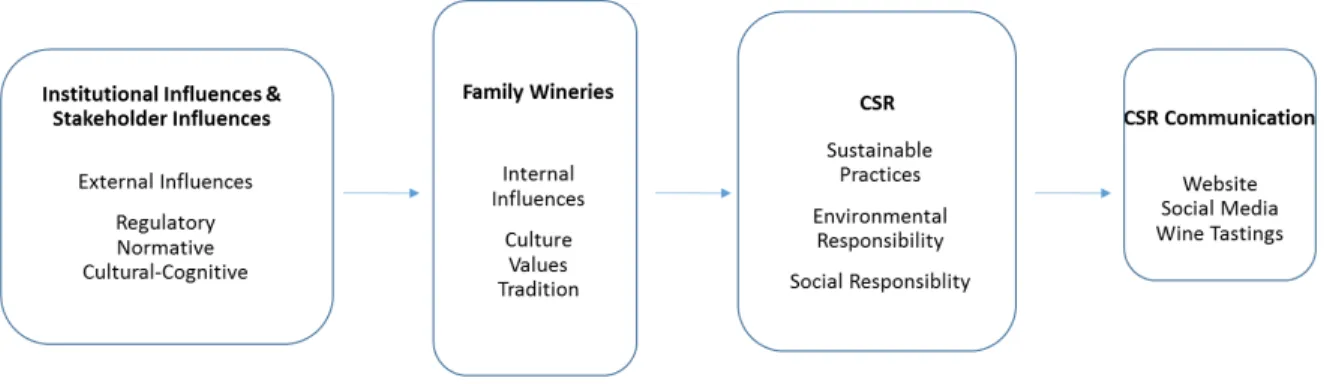

Figure 1. Theoretical analysis thought process ...281 Introduction

Sustainability is increasingly becoming more relevant among family-run businesses, with the wine industry already adopting the role of stewards of the land, ensuring the viability of the family business and the health of the natural and social environment. The visibility of sustainable practices has become more pronounced and noteworthy with the increased use of websites and social media, no longer limited to traditional marketing’s confines. Sustainability, both social and environmental, can be identified as

a core responsibility throughout the wine industry (Ledbetter, Darden, & Kruse, 2019). Family-run

businesses are heavily influenced by their history, identity, and impact on the ideology behind their personal values, social responsibility practices, and communication. The research will examine the current extent to which sustainability practices are communicated in the United States and Hungary, two distinct wine regions. Here, we will discuss family businesses in the wine industry, examining the regional influences on sustainability and corporate social responsibility (CSR).

1.1

Background

The unique ways in which family businesses and wineries organize themselves provide an ample opportunity for research to assess how the institutions of family businesses and the wine industry rationalize their social responsibility through communication. Our research lands at the intersection of these two institutions inciting an examination of corporate social responsibility implementation through the lens of institutional theory.

Family-run wineries are differentiated from larger corporate-run wineries in the organizational structure and succession structure. Many wineries have taken responsibility as stewards of the land and are so much more than farmers. They maintain structures and fences, deal with infestations and fires, employee management, water management, habitat conservation, economics, and branding. There are a wide range of decision-making roles involved in the leadership of family-run wineries. These can include crop and planting planning, logistics, operations, community engagement, and responsibility for the financial well-being of family members and employees.

In Sonoma County, California, 97% of grape growers in the region were part of the Sonoma County Winegrowers (SCW) sustainability program, and 89% were certified sustainable (Ledbetter et al., 2019). Each wine region in the United States appears to be on board through the local winegrowers’ associations by providing initiatives and sustainability leadership, aiming for 100% certification of members. The support from these organizations encourages commitment to sustainable practices in the wine industry.

While the importance of sustainability in the US is rapidly growing, in contrast, Hungarian wineries have challenges to overcome regarding sustainability. The root of all these challenges lies in the sector’s decreasing financial viability due to the import of cheaper foreign wines into the country and the decreasing price of wine grapes resulting in a sharp decrease in the area of vineyards (Pallás, 2016; Szamosköziné Kispál, 2018).

1.1.1 History and tradition of winemaking

History and tradition have sustained winemaking by adapting quickly to demands and changes. Both Hungary and the United States have cultivated their respective wine industries, though having two very distinct origins, both in history and tradition. A brief history of Hungary and the US helps us better understand how each has sustained throughout time and positioned in today’s wine industry.

international wine scene. It is important to learn more about Hungarian wine production because its 20th century socio-political climate did not favor high-quality wine production and set any sustainability-related initiatives significantly back. Between 1945 and 1989, the country was part of the Communist block and was ruled by a communist government. The state controlled all wine production that served the markets of the Soviet Union (Nándor, 2012). There were no privately owned wineries, only state-operated farming cooperatives that, in many cases, consisted of people who had never previously produced either grapes or wine. According to Nándor (2012), deprivatizing meant that there were only two options: either farmers were to turn over the grapes or wine to the government’s common collective, then the state would reappropriate it. In these few decades, “quantity” was emphasized over “quality.” Wine eventually made it to the North American continent via Spanish and French Huguenot settlers in the 16th century, who made wine with a North American native grape known as muscadine. According to Thach (2018), the Brotherhood Winery in New York State was established in 1839 and is the oldest continually operated winery in the US. Initially, pests plagued many of the vines brought to the US early on due to the moist climate. Moving westward, the vines came upon the drier climate of the Spanish missions in New Mexico in 1629, offering a sandy soil better suited for growing. Vineyards emerged in California around 1769 with the Spanish mission in San Diego. Twenty more missions were built throughout California, including Sonoma in 1823 and Napa in the 1830s. California is now responsible for 90% of US wine (Thach, 2018).

Today, every state in the US produces wine. Nearly half of the more than 10,000 wineries in the US are located in California. There are more than 4,500 wineries in California, 794 wineries in Oregon, and 792 wineries in Washington (Todorov, 2019). While many small and medium-sized wineries in the US are family businesses, the truth is - the majority of the wine produced comes from large conglomerates (Walker, 2013).

In Hungary, there are 22 wine regions. The country holds 2% of the EU area under vines, and most of the wines produced are consumed locally - only about a quarter of the production is exported. Within Hungary, it is ubiquitous that vineyards and wineries are mostly family-run. 73% of the vineyards are cultivated by the landowners who sell their grapes to larger wineries for wine production, while the remainder is for private and local consumption (Szamosköziné Kispál, 2018). However, there is a lack of data regarding the number of wineries that are family-owned in Hungary.

In the wine industry, there is a strict bond between family business and territory. Certain sets of values, traditions, and symbols are represented by multi-generational family-owned wineries rooted in the area from which the family originates (Iaia et al., 2019). When it comes to sustainability in the wine industry, it encompasses complex concepts. Sustainability involves economics, environmental impacts, and human resources, including family, employees, and the surrounding community (Ohmart, 2008; Santini, Cavicchi, & Casini, 2015).

Environmental concern in the wine industry is strongly related to the image of a winery’s brand. Isaak (2002) discerns between green and green-green businesses. Green indicates those firms that become green not based on ethical issues but aim for positive feedback or economic gains that being “sustainable” might create, whereas green-green businesses are green-oriented since their startup (Isaak, 2002; Santini et al., 2015). Unfortunately, there is no exemplary sustainable behavior; some companies, countries, and regions are considered “greener” than others. Szolnoki (2013) adds that wineries understand sustainability in various ways as there are differences and misunderstandings in the approach implemented between countries and wineries. On a global scale, California holds a leading position on sustainability practices (Santini et al., 2015). Hungarian multi-generational, family-run wineries seem to have nearly always included environmental sustainability in their production methods (Nándor, 2012). Additionally, regional regulations in Tokaj, a renowned wine region in Hungary, leave little space for non-eco-friendly production methods. Tokaj is labeled as a “historic landscape” and is under UNESCO’s protection. With the UNESCO title, there is a required expectation of sustainability, sustainable development, and use of ecological methods for grape-growing and wine production as a pathway for vineyards and wine producers to preserve the land for the future (Bender, Biagioli, & Prats, 2012; EU Commission, 2018).

Six drivers were identified to help understand the relationship between business and sustainability, including stakeholder influence; consumer demand for sustainable services and products, resource depletion; capital market scrutiny; employee engagement, and regulatory requirements (Santini et al., 2015). It was concluded that being sustainable represents a strategic choice regarding an internal or external stimulus for the business. Internal drivers of a firm are those taking place within the business, while external drivers take place in its external environment, including pressures from customers, institutions, associations, communities, competitors, regulators, activists, and environmental groups. Sustainability concerns strongly affect the image of a business. Creating sustainable awareness successfully among wineries lies in the local players’ networking capacity. For example, in California, the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices has been fostered by agro-ecological partnerships (Santini et al., 2015). Wineries are paying attention to each other and what others are doing to become better and ultimately more sustainable, resulting in widely-spread sustainable practices in the competitive environment.

1.1.2 Family businesses

A family business is an interaction between the business and the family, two separate but connected systems. Family businesses have been associated with values related to long-term orientation, strong relationships with employees, and strong ties to social and businesses in the community and concern for their family and brand reputation (Iaia et al., 2019). In general, these qualities may better advance the adoption of socially responsible behavior in a family business (Nekhili, Nagati, Chtioui, & Rebolledo, 2017).

The organizational structure of a family business is an important determinant of long-term success (Köhr, Corsi, Capitello, & Szolnoki, 2019). The factors that contribute to the heterogeneity within a family run business are dependent on the family culture and history and how the power in the organization is managed. The leadership of family businesses can prefer autonomy in the management and the need for other family members’ involvement as participative leaders. The centralization of power allows for support and unity under one leader and supports decision-making (Köhr et al., 2019). The adoption of a hierarchical approach avoids the risk of conflict and can lead to sustainable long-term development.

A “culture of informal cooperation with strong ties” represents the characteristics of a family business (Berghoff, 2006; Köhr et al., 2019, p. 184). Often family members must adhere to within the business multiple roles and adapt quickly. A high degree of flexibility is a pattern observed among family members in the wine industry and proves to create obstacles (Köhr et al., 2019).

As family businesses in the wine industry lean towards sustainability in their environmental and social responsibility practices, consideration of future generations as main stakeholders is necessary. Delmas and Gerguad (2014) recognize that the current owners’ decision to become ecologically certified addresses a long-term perspective for the family business, thus embracing organizational stability and sustainability. Two qualities that future generations possess are the ability to influence the current management and leadership behavior through the succession of the family business.

A characteristic that defines a family business is how the business is managed and passed through multiple generations (Delmas & Gergaud, 2014). This feature has a considerable influence on the decision-making processes and entrepreneurial innovation, especially in the wine industry. The succession of who will lead a family business in the next generation is an issue that needs to be dealt with by planning. Without planning, transition problems can occur, such as the viability of the business, next of kin choosing not to be part of the business or current leadership does not think a successor is prepared and is reluctant to relinquish control (Delmas & Gergaud, 2014). The success or failure of a

firm. Examples of such can create value by developing a philanthropic arm or branch out to create a new division within the family firm (Zellweger, Nason, & Nordqvist, 2012).

The analysis of sustainability in family-run businesses is pivotal, based on the inclusion of familial relationships. There are scores of definitions of family-run businesses, a single distinction that is maintained is the succession from one generation to the next (Delmas & Gergaud, 2014). These familial relationships have a significant influence on decision-making processes and entrepreneurial innovation. In the wine industry, where the customers have close connections to the business and its products, the prospective benefits of family management is capitalizing on communicating the family history, values, and identity to the customers as stakeholders (Gallucci, Santulli, & Calabrò, 2015).

The stakeholders who have reigned important within family-run wineries are the future generations. The succession process is defined as “the actions and events that lead to the transition of leadership from one family member to another in family firms” (Delmas & Gergaud, 2014, p. 230). Several elements qualify family member inheritors as stakeholders. The future generations are vital for the company’s survival, which influences how the current leaders of the company behave in anticipation of intergenerational succession (Delmas & Gergaud, 2014). Also, it is these future generations who will need to deal with possible externalities. If previous generations damage the land, the responsibility to reconcile the damage falls upon the children, grandchildren, or next owner to produce wine. Taking proper care of the land right now is essential for its survival in the long-run—thinking of future generations as stakeholders are particularly important for family firms compared to non-family firms. Business owners planning their succession are more likely to recognize future generations’ needs and adopt sustainable practices (Delmas & Gergaud, 2014). Reciprocally, they add that future stakeholders have a vested interest in their family business's future performance. The adoption of sustainable practices enables the businesses’ long-term economic viability that eco-certification can bring to these future generations (Delmas & Gergaud, 2014).

1.1.3 Corporate social responsibility (CSR)

Many companies today realize that financial development means very little without sustainability and, ultimately, sustainable development. As the consumer mindset evolves towards sustainability, businesses have been increasingly seen as major causes of social, economic, and environmental problems. Thus, resulting in the development of stakeholder management, business ethics, and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Without sustainability being part of firms’ core business, they cannot survive in the long-run. Emphasizing the importance of sustainable organizations, Paul Polman, the CEO of Unilever, stated, “A new business model with sustainability at its heart is vital for quality of life around the globe to improve. Only the businesses that grasp this will survive. Only those who grow sustainable will thrive” (Unilever, 2014, p. 3).

In this paper, we address the social responsibility that family-run wineries provide by the industry’s inherent nature and by the pressures and influences imposed by society. Within our research of family-run wineries, it was revealed that there was very little use of the term “corporate social responsibility” but found the term “social responsibility” to be the norm. There was very little data discussing the distinction between CSR and SR in the reviewed journals. Both CSR and social responsibility aim to ensure that no harm is done while benefiting society and the environment. The main difference is the context of businesses and how family wineries do not necessarily associate the term “corporate” to their family business. The researchers conclude that the term social responsibility best fits the self-perception of wineries and vineyards interviewed. It is essential to talk about CSR as businesses, specifically family-run wineries, are taking responsibility for the environment and social needs of the surrounding communities. Through their actions, they acknowledge their responsibility for the world around them and making sure to provide equal opportunities for the coming generations.

1.2

Previous Research

Previous research literature spans disciplines, including business management and economics, family business, and the food and wine industry. The majority of the identified research is centered on family businesses in the wine industry, with only one journal article researching family business, wine, and CSR, and another researching family business, wine, and institutional theory. Located in Appendix C is a table showing the literature reviewed and the concepts related to our research covered by each journal article.

There is very little written on the institutional influences imposed upon individuals at family-run wineries except for the research from Brundin, E. and Wigren-Kristoferson, C. in 2013. Their research aims to examine how institutional influences interact with entrepreneurial thinking and the effects on traditions and values. The findings of their research found that tradition, through identification with the land and cultivation of the wine, mattered more than influences leading to entrepreneurial activities (Brundin & Wigren-Kristoferson, 2013).

Family businesses in the wine industry possess a meaningful resource of close relationships of internal stakeholders, of which the management includes family members working together. These close relationships in family businesses often lead to the consideration of future generations. The research of Delmas and Gergaud (2014) found that US winery owners, with intent to pass the winery down to the next generation, are more likely to adopt sustainable certifications as a means of environmental and social responsibility due to their long-term perspective.

The public has grown aware of social responsibility issues and increasingly applies pressure to businesses to communicate their CSR efforts (Nekhili et al., 2017). The expectations of CSR communication comes in the form of annual reports or sustainability reports. The communication of CSR is valued greatly by stakeholders, specifically shareholders. The research from Nekhili et al. (2017) shows that family firms report less information than other non-family firms. Family businesses that have an image of contributing to CSR activities attain an image of nurturing stakeholders. Through a family’s business’ environmental and social responsibility efforts, they may be perceived more favorably by key stakeholders. Family businesses often receive a favorable reputation that is shaped by social and environmental actions. The literature available discusses the financial aspects regarding CSR disclosure visible to shareholders but not seen by the customers.

Iaia et al. (2019) researched the online CSR communications of Italian family businesses in the wine industry compared against non-family businesses. Iaia et al. (2019) findings resulted in both family and non-family businesses having intangible qualities such as traditions, history, and values as fundamental drivers in online CSR communication. CSR aligns with stakeholder theory (Freeman, 1984), asserting that a business needs to establish and maintain stakeholder relationships, including communication of environmental and social responsibility actions (Iaia et al., 2019; Lim & Greenwood, 2017). Morsing and Schultz (2006) stated that conveying information through websites makes exchanging information between stakeholders much simpler. This research indicates that winery websites and social media give more accessibility to CSR communication to stakeholders.

1.3

Research problem and aim

Studying family businesses is important since they constitute a large part of businesses worldwide and represent a unique combination of family and organizational values. These values can be long-term orientation, social and business community connections, employee relationships, and attention to reputation. According to Iaia (2019), family businesses adopt socially responsible behavior more than non-family businesses. It is described as the set of potential and real resources like norms, vision, cooperation, values, and trust that are implicit and intrinsic in a family business. These values are

Many family-run wineries incorporate environmental sustainability and social responsibility into their business practices (Bender et al., 2012). The research available implies that family-run businesses within the wine industry are regulated by institutionalism (Brundin & Wigren-Kristoferson, 2013). We do not know what specifically influences their decision-making to implement sustainability practices and why they do so. It is important to understand the external and internal influences that guide family-run businesses.

This thesis aims to explain how internal and external influences affect family-run CSR practices and communication identified through institutional and stakeholder theory. The values held by these organizations affect how they communicate and expedite what CSR means to their business and accountability to their stakeholders. Institutional theory can identify these internal and external influences of the operation of a family business. It also looks at how they conform through rational and unconscious choices. The three pillars of institutional theory include regulatory, normative, and cultural-cognitive, which gives legitimacy to the decisions that family-run businesses make regarding CSR. CSR practices of wineries are researched in parallel with institutional and stakeholder theory to show how and why wineries are responding to internal and external pressures. Hungary and the US were chosen due to their diverse histories in winemaking. Each having a unique perspective on the subject of sustainable practices. This research fills a gap seen in the research literature by discussing institutional influences on family wineries and their CSR practices.

Owners of family-run wineries generally maintain operational decision-making roles, suggesting that the wine industry is a good candidate for studying the influence of attitudes and norms on implementing environmental practices (Marshall, Akoorie, Hamann, & Sinha, 2010). Stakeholder pressures are felt from local communities, employees, government agencies, environmental activists, consumers, and the land’s ecological health. Local wine industry associations provide sustainability guidelines and best practices to avert impacts on the environment (Marshall et al., 2010). As a result, multiple stakeholder groups play important roles in influencing the wine industry to adopt sustainability practices for environmental and social responsibility. The pressure by stakeholders to improve sustainability performance in the wine industry is a presence that always needs to be addressed.

1.4

Purpose

The purpose of the research is to explain how and why the internal and external influences faced by family-run wineries affect their CSR practices and communication through institutional theory and stakeholder theory. Research on family businesses in the wine industry, specifically family-owned vineyards and wine production, has only been touched upon by researchers. Of the previous research, only Iaia et al. (2019) touches on the three factors of wine, family business, and CSR. Analysis of sustainability practices, both environment and social responsibility, direct our research on the stakeholder influences and the decisions that follow. This study is in response to fill a research gap by linking family businesses in the wine industry with their environmental and social sustainability practices to their CSR communications.

1.5

Research questions

RQ1 What drivers, both internal and external, influence family-run wineries to implement

environmental and social sustainability practices in their corporate

social responsibility efforts in the context of the three pillars of institutional theory?

RQ2 Why are corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices implemented and

1.6

Structure of the research paper

This chapter, the Introduction, provides the background defining the connection between family run-businesses, sustainability, and the wine industry, thus introducing the research context. It also gives an overview of the purpose and research problem, anchoring this paper to the research questions. The second chapter, Theoretical framework, presents the three pillars of institutional theory, stakeholder theory, and CSR framework. These theories and frameworks will help understand the internal and external influences felt by family-run wineries, leading to their environmental and social responsibility choices. The third chapter, Methodology, details the research process of data and methods collection. In the fourth chapter, Findings and analysis, the data from the interviews are presented in quotations. The identification of themes deducted from the data gives insight into the current mindset of family members and employees working at family-run wineries. The fifth chapter, Discussion, presents the findings to the research questions using the theoretical frameworks of institutional theory, stakeholder theory, and CSR. Finally, the Conclusion summarizes the research, including implications and recommendations for future studies.

2 Theoretical framework

This chapter details theories and frameworks which are at the foundation of the research. Here both institutional theory and stakeholder theory offer differing theoretical perspectives but provide a complementary approach to understanding the underlying influences that drive CSR in family-run wineries.

2.1

Institutional Theory

Organizations are continually responding to changing customer needs. External environmental influences such as socio-political, economics, and technology often determine the approach in which organizations respond to change. Institutions are traditionally defined by a set of economic, political, legal, or social frameworks that serve as a foundation for the production, sales, and distribution of goods and services (Scott, 2014). Scott (2014) specifies that rules and requirements often lend itself to conformity to achieve legitimacy and acceptance among other institutional organizations.

2.1.1 The institution of family-run businesses

Family-run businesses are subject to high levels of institutional control (Scott, 2014). Both the wine industry and family businesses are two well-established institutions. Within the wine industry, there is conformity that is globally adopted as a result of centuries of cultivation of grapes and winemaking (Brundin & Wigren-Kristoferson, 2013). Across the world, the industry uses homogenous methods of cultivating grapes and production of wine. At the same time, the differences in the finished product are mainly a result of the varietal of grapes, the quality of the soil, the weather of the region, and the personal taste of the winemaker (Brundin & Wigren-Kristoferson, 2013). An established family brand adds an additional personal touch to the wine. Family businesses are acutely aware that using the family’s name as a brand is highly associated with the quality of the wine produced and ultimately reflected on the family’s reputation.

“Institutions are social structures that have attained a high degree of resilience”(Scott, 2014, p. 33). Institutional theory is defined by three pillars; cognitive, normative, and regulative structures, which provide stability and meaning to social behavior, and activities. The organizational dynamics result from abstract dimensional levels of dominion, world systems to interpersonal relations, and principles that

include routines, products, and symbolic and relational systems(Scott, 2014).

The regulative pillar provides explicit guidance to organizational members through rules, controls, rewards, and sanctions. The normative pillar guides behavior through a less explicit system of social norms and values. The cultural-cognitive pillar directs behavior through the construction of social identity (Scott, 2014).

An alternative definition of institutional theory comes by DiMaggio and Powell (1983), which utilizes three institutional isomorphic change mechanisms. 1) Coercive isomorphism that comes from political influence and the need for legitimacy; 2) mimetic isomorphism that deals with the standard response to uncertainty; and 3) normative isomorphism, which associates with professionalism (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Leaptrott, 2005). Isomorphic change is defined as “a pressure that forces one unit in a population to conform to other units that face the same set of environmental conditions” (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Leaptrott, 2005, p. 216). The applicability of institutional theory is significant in the context of associating the value of internal and external influences on organizations (Weerakkody, Dwivedi, & Irani, 2009).

2.1.2 Regulatory pillar

The regulatory pillar consists of two factors: the capacity of establishing rules and the conformity to these rules. Regulatory compliance is driven by pressure. The organizational actors in the family make rational choices through behavior to further their best interests. This behavior allows for the maximization of rewards and minimization of unfavorable outcomes. A positive result of regulatory pressure is legitimacy. Legitimacy recognizes the organization as a proper actor in the pursuit of commerce (Leaptrott, 2005). A key defining feature of a family business is that it is passed down from one generation to another. The primary regulatory structure of a family business is the governance structure. The focal point of the governance structure is the ownership of decision-making rights. Governmental regulations are another aspect of the regulatory pillar that can impose policies that affect the business’s behavior through laws and regulations either by pressure or persuasion. If policies are not followed, the consequences are not conducive to a positive family business image or brand, reducing its legitimacy in both the industry and community. Sanctioning processes can operate through official institutions or informal mechanisms like shaming of the organization within the community. Leaptrott (2005) states that lack of compliance with regulatory structures often has a negative financial impact, leading to financial sanctions potentially making the business financially unsustainable.

2.1.3 Normative pillar

Both values and norms influence the normative forces. The norms cite the legitimate channel for pursuing goals bounded by values. Values, through ideals and actions, are compared and assessed against the behaviors and existing structures, while norms indicate how actions should be done to fit the objectives and bring value to society (Scott, 2014). The values and norms in a business can originate as a response to the environment or society in pursuit of legitimacy (Hinings, Thibault, Slack, & Kikulis, 1996; Leaptrott, 2005).

Both outside and inside influences affect normative forces. Community and industry organizations are an impetus of outside normative influences (Granovetter, 1973; Leaptrott, 2005). The normative forces, such as norms and values regarding environmental recommendations and obligations to employees by industry organizations, often request compliance of industry standards for membership (Scott, 2014). Business members have a strong need to maintain their business’s legitimacy and do not want to compromise the stakeholder relationship by crossing the boundaries.

Within a family business, the family members share social and learning experiences that create an environment for common norms and values. These are not merely anticipations but normative expectations that can determine how specified family members and non-family members are supposed to behave. The roles each member plays carry expectations of behavior (Scott, 2014). External pressures are more likely internalized by individuals than regulatory processes as there is more incentive to conform. (Scott, 2014). Sharing values and norms legitimizes adherence to similar normative principles. Family members who are not active participants, potentially retired or not employed in the family business, can also exert normative influence. These normative influences, such as the expectation of behavior, are not always applied equally to each family member, often only applied to family members in specific roles. A rules-driven behavior can lead to actions taken based on situations relative to the positional demands of the organization’s role (Scott, 2014).

Family businesses often go through a self-selection process in which they seek non-family employees. They identify attributes similar to themselves, such as personal attributes, values, and norms, all from the same geographical regions. For non-family employees, the conforming influence is high when family members’ values and norms are homogenous (Leaptrott, 2005).

2.1.4 Cultural - cognitive pillar

Culture can be defined as a “whole way of life of distinct people or other social groups” (Hesmondhalgh, 2013, p. 16). The cognitive forces of institutional theory refer to logical sense-making of social reality and shared understanding of culture (Brundin & Wigren-Kristoferson, 2013). The cognitive consistency of forces in relation to the social construction of reality. Legitimacy is attained through conformity, which ultimately results in an orthodox organizational structure. The naturalization of establishing patterns, definitions, and frames of reference becomes reciprocated between the actors within an

organization. In some cases, organizations can reduce uncertainty by mimicking the behavior of another

organization’s best practices to minimize anxiety about standing out from the prescribed norms. The use of symbols, actions, and words facilitate mimicry as a means to deal with uncertainty.

The use of implicit rules offers guidance for the actors within a family business. The family organization members guide the behavior of all employees within the business to not stand out and to use practices that have been successful in the past (Leaptrott, 2005). Family roles that develop over the generations, such as dominance, submission, rebellion, and conciliation, are understandably expected in a family business context. This is the deepest level of organizational governance as it rests on a subconscious, taken-for-granted understanding.

Changes are increasingly more difficult to make once the organization’s tasks and roles are naturalized. Family businesses that consist of family members with an absence of non-family employees are more likely to have difficulty implementing change. Conformity within the family business is higher for the nuclear family members than for non-family employees or family members outside of the nuclear circle (Leaptrott, 2005).

2.2 Stakeholder theory in sustainability

Sustainability represents a strategic choice for organizational leaders (Santini et al., 2015). Stakeholder theory provides a foundation as a holistic approach for understanding how pressures from stakeholder groups encourage the adoption of sustainable environmental practices (Marshall et al., 2010). A stakeholder within an organization is defined as “any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization’s objectives” (Freeman, 1984, p. 46). Within the wine industry, a growing number of family businesses are attuned to their environmental and social impacts. Freeman (1984) states that the purpose of business is not to make a profit. The purpose of a business is excited about an idea, creating value for all stakeholders, not just profits for shareholders. Business ethics is at the center of environmental and social sustainability (Hörisch, Freeman, & Schaltegger, 2014) Accountability of the impacts on society, environment, and economy are at the heart of sustainability. The stakeholder approach’s relevance is a method giving greater engagement with as many stakeholders as possible, leading to not only organizational sustainability but also environmental sustainability. Stakeholder theory asserts that a business’s success is dependent on its management of relationships with stakeholders. Freeman (1984) emphasizes the importance of stakeholder management for organizational sustainability. Building off of Freeman (1984), the term “environmental stakeholder” is defined as “individuals or groups that can affect or be affected by the achievement of a firm’s environmental goals” (Banerjee, Iyer, & Kashyap, 2003; Marshall et al., 2010, p. 406). The environmental stakeholders to family-run wineries are regulatory structures, employees, the community, the land, certification bodies, and industry associations. All stakeholders influence by exerting pressure on the business and industry.

Stakeholder theory focuses on managing stakeholder relationships instead of stakeholder management, implying the manipulation of stakeholders (Hörisch et al., 2014). Freeman (1984) specifies that relationships are interconnected between a business and its customers, suppliers, employees, investors, communities, reinforcing that a business should create value for all stakeholders, not just shareholders. The stakeholder pressure is part of the complex system, which influences business as drivers of sustainable practices.

Stakeholder trust has to be earned by gaining the societal license of organizational operation by “walking the talk, managing with integrity, making a profit with principles” (Miska & Mendenhall, 2018, p. 2). Miska and Mendenhall (2018) continue by highlighting the importance of leaders’ mindsets since a stakeholder-centered way of business operation requires a broader worldview and stakeholders over shareholders’ operation orientation. This “relational leadership approach” is based on cooperation, inclusion, and collaboration (Maak & Pless, 2006). Consequently, if an organization does not conduct its operations according to such principles, it jeopardizes its social legitimacy and future financial and possible spatial growth (Chandler & Werther, 2014).

2.3

Corporate social responsibility framework (CSR)

A broad base of stakeholders influences corporate social responsibility practices of family-run businesses. The CSR practices of family-run wineries are researched in parallel with institutional theory and stakeholder theory to provide a full picture. Stakeholder theory is interlinked within the concept of corporate social responsibility (CSR) as businesses incorporate social, environmental, and economic responsibility for relevant stakeholders. Institutional theory brings to light the external and internal influences leading to their CSR efforts. The inclusion of a broad set of stakeholders’ concerns for CSR decision-making is based on these influences.

Our societies are made of multiple organizations. Tolbert and Hall (2009) point out that the most effective way to change society is to make changes to the organizations. Relative to the nested view of sustainable development, businesses and organizations need to consider the outcome of their deeds since there is no ecological sustainability without corporate sustainability - organizations are not separated from their environment (Linnenluecke & Griffiths, 2010). Organizations can easily create problems, identified as externalities that ultimately, the rest of the society will have to manage. Tolbert and Hall define externalities as “the results of an economic transaction that affects others who did not participate in the transaction and whose interests were not taken into account” (Tolbert & Hall, 2009, p. 12). Relating to climate change: approximately 200 years after the industrial revolution, the people of the 21st century have to solve the negative externalities generated by these many years of development. Conducting business without sustainable environmental practices in place is simply not viable any longer. Sustainable development is a manner of reasoning concerning how growth can be maintained while preserving the environment in which we all live in. The environment encompasses all of the Earth, the place where we live, and within the environment, we conduct development. It is a long-term view of development where all people do well across future generations. This responsibility for future generations is focused on “intergenerational well-being” and calls for the international collaboration of all business and societal sectors worldwide. There are three moral imperatives: sustainable development is based on the satisfaction of human needs, respect of environmental limits, and ensure social equity. It is a normative value system (Holden, Linnerud, & Banister, 2017), which implies a relationship between an organization and society (Isa, 2012).

Definitions of CSR vary widely. Firstly, CSR is an internally complex concept and has relatively open rules for interpretation and execution. Second, the notion overlaps with other business-society relations, and third, it is a dynamic phenomenon (Isa, 2012). Strategic CSR is defined as an “implementation of a holistic CSR perspective of a firm’s strategic planning and core operations, managing the interests of a broad set of stakeholders to achieve maximum economic and social value over the medium to long term” (Chandler & Werther, 2016, p. 248). According to this definition, the use of CSR is one of the measured and well-reasoned social values and financial value. It assumes the social, economic, and environmental sustainability of the firm, ultimately generating moral capital. Chandler & Werther (2019) redefined CSR as sustainable value creation being the key element to the firm’s value-creating purpose. Aligning with stakeholder theory, it is the responsibility of a corporation to create value. Schwartz & Carroll

definitions of CSR to explain how and why businesses choose to pursue CSR initiatives to their stakeholders.

Stakeholder theory argues that CSR should be incorporated into an organization or firm’s day-to-day operations and strategic planning. Miska and Mendenhall (2018) add that there is neither real long-term business success nor financial viability without an organization. More importantly, its leadership acts responsibly towards all of its stakeholders. Opposition to the use of CSR comes from Hörisch et al. (2014), stating that a business’s operation should focus on integrating responsibility into the daily operations of a business. There should not be a separation of ethical issues from business, as they are interlinked (Hörisch et al., 2014). Residual CSR as a means of compensation to redistribute money and effort to make up for irresponsible practices is not ethical and should not be considered CSR.

Quite often, CSR and stakeholder theory conflict as to the limits of responsibilities of businesses to society. CSR proponents argue that businesses have an ethical and moral obligation, which is expected but not required (Carroll, 1991). Stakeholder theory and CSR are not the same. CSR specifically obliges society, while stakeholder theory cites responsibility to create value for their stakeholders (Freeman & Liedtka, 1991).

Stakeholder theory champions that a business needs to establish and maintain a relationship with all stakeholder groups who show interest by providing the information they need (Freeman, 1984). Delmas highlighted that stakeholders need to be informed about the good practices carried out by the business resulting in a positive attitude toward the concept of CSR. Through this logic, businesses can improve their corporate reputation and brand image. A business that implements CSR in many ways has a competitive edge over its competitors and added value can be brought to the company (Iaia et al., 2019). It enables an open dialogue between businesses and stakeholders, fostering responsibility, ethically, and socially (Lim & Greenwood, 2017), as well as allowing the firm to listen to stakeholders and gather information on their various expectations, and to obtain feedback on the perception of the firm’s CSR initiatives. CSR can be associated with the natural progression of marketing and provides social recognition, adding value to businesses and their bottom lines. Companies that have not yet implemented may not yet understand the importance of communication of CSR or believe in the contribution CSR

makes to its stakeholders (Iaia et al., 2019).

In many organizations, CSR is a proactive communication that engages stakeholders in creating a relationship today, most CSR communication occurs electronically, through newsletters and corporate websites. Businesses use their websites as a tool to project how they want to be perceived by their customers and stakeholders, and by this reaching the highest level of CSR communication (Iaia et al., 2019). The Internet and social media have enabled businesses to establish both one-and two-way communication making it possible to receive feedback from stakeholders and to create a direct dialogue with them on CSR issues.

CSR communication can be divided into two strategies. Stakeholder information strategy is a one-way model where only the company transmits information to its stakeholders, hoping to gain their positive support by informing them of its philanthropic actions. Whereas the stakeholder response strategy is a two-way CSR communication model in which the company transmits information to its stakeholders about its good intentions while paying attention to their answers (Morsing & Schultz, 2006). Communication of information is a value that stakeholders see as an advantage, although only implementing a response strategy is not enough (Ettinger, Grabner-Kräuter, & Terlutter, 2018). The actual involvement of stakeholders has to happen by actually activating and inviting stakeholders to engage in dialogue. The goal of the response strategy is not solely just engaging stakeholders but ensuring them that their opinions are recognized, and their needs are met (Iaia et al., 2019).

The characteristics of a business are essential parts of how a business conducts its behavior in CSR reporting and can be observed through the behavior of the individuals within the business. Internal influences on business practices are different from corporate to a family-run business. There is importance related to shifts in family values on the environmental and societal economy in which they are embedded (Bergamaschi & Randerson, 2016).

3 Methodology

This chapter will detail the methodology describing the research methods used to collect data from the research questions to complete this study’s purpose. A qualitative research method is used to facilitate the research questions, aiming to analyze the current CSR communication practices in family-run wineries in the US and Hungary.

3.1

Research design

The research design aims to ensure that the data obtained clearly and rationally addresses the research problems (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). The exploratory nature of the research calls for the identification of new patterns and relationships facilitated by using an inductive strategy (Bryman & Bell, 2015). The use of institutional theory and stakeholder theory will help us find consistencies and variations of CSR communication practices. The research problem determines the research design (De Vaus, 2001). Qualitative research is chosen to answer the research questions as to “why” and “how.”

This study aims to analyze sustainability practices in environmental and social responsibility, which direct our research on how the internal and external influences faced by family-run wineries affect their business operations and CSR communication. With qualitative research, the perspectives of persons working within the wine industry from both family members and non-family members regarding sustainability give insight into the wine industry. A focus on the social responsibility practices in family-run wineries was selected based on the wine industry’s visible commitment to land stewardship and personal responsibility of family-run wineries. The sampling is designed to capture the perspectives into the phenomena, generating committed and enterprising intentions. The design of the research explains actions materialized between elements of family-run wineries and the resulting CSR practices. Institutional theory and stakeholder theory are used to identify the external and internal influences and how they affect business decision-making and CSR communication. Institutional theory will help explain how family-run businesses conform through rational and unconscious choices. Stakeholder theory emphasizes the value of stakeholders, which supports the importance of CSR practices. A qualitative approach utilizing semi-structured interviews and document analysis are used to aid in the inclusivity of a complex industry that is difficult to quantify all of the moving parts. Qualitative research

also makes it possible to discover people’s attitudes and motivations. Ten wineries were analyzed in

winemaking regions in Hungary and the US, of which nine semi-structured interviews were undertaken with employees, seven of which were family members. Two interviewees responded with written responses. The interviews intend to highlight the current and relevant perspectives of the winemaking industry through a family business.

3.2

The sample population

The study’s focus was to obtain a range of perspectives from multiple family-run wineries to identify phenomena that influence wineries in their CSR practices and communication. Based on a clear set of criteria, the researchers used purposive sampling to locate participants based on their relevance to the research questions (Bryman & Bell, 2015). A goal was set to obtain one interview participant from ten family-run wineries. The wine regions of Hungary and the US were chosen based on their distinct differences in history and tradition. Both have sustained winemaking by adapting quickly to demands and changes. We aimed to represent a range of family-run wineries in Hungary and the US to provide current perspectives in the wine industry.

3. Locations Hungary and the United States

The criteria for recruiting interview participants included family-run wineries that focused on environmental sustainability, identified through wine association memberships and self-identification on their websites. All wineries were classified as family wineries. This classification was supported by the use of “family” in the winery name or was reflected upon in their written history located on the winery website. The targeted interview participants were both family and non-family member employees whose roles include decision-making within the family business and responsibility for implementing social responsibility. The aim was to interview a family member at the highest level within the organizational hierarchy, which meant the owner or family member worked beside the owner. Both family members and management in family-run businesses maintain decision-making roles. It is necessary to see how they are influenced and how this influence is implemented in CSR practices regarding environmental and social responsibility.

A total of 42 email requests, including contact through LinkedIn, and five phone calls were made to recruit interviewees. A preference for a family member as an interviewee was noted but not always made available per our request. Of the nine interviews granted, seven were family members. The interview participants are represented in Table 1.

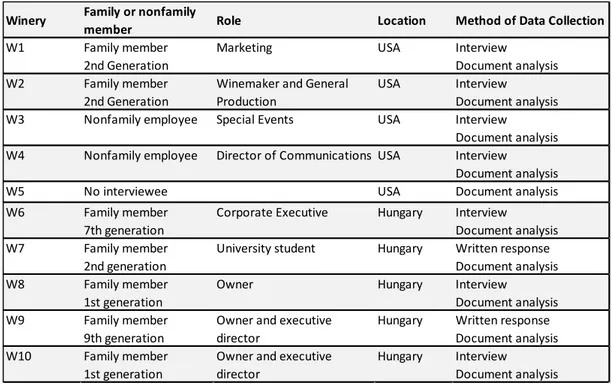

Table 1. Summary of selected sample and method of data collection

Winery Family or nonfamily

member Role Location Method of Data Collection

W1 Family member 2nd Generation

Marketing USA Interview Document analysis

W2 Family member 2nd Generation

Winemaker and General Production

USA Interview Document analysis

W3 Nonfamily employee Special Events USA Interview Document analysis

W4 Nonfamily employee Director of Communications USA Interview Document analysis

W5 No interviewee USA Document analysis

W6 Family member 7th generation

Corporate Executive Hungary Interview Document analysis

W7 Family member 2nd generation

University student Hungary Written response Document analysis

W8 Family member 1st generation

Owner Hungary Interview Document analysis

W9 Family member 9th generation

Owner and executive director

Hungary Written response Document analysis

W10 Family member 1st generation

Owner and executive director

Hungary Interview Document analysis

3.3

Method of data collection

Contributing to the background, research questions, and theoretical framework, an initial review of the literature was conducted, providing our secondary data pool. In addition to the aforementioned data, primary data was collected through semi-structured interviews and supported by document analysis.

3.3.1 Interview guide

The interview guide development was based on the review of literature and theory with the purpose of answering the research questions. Each question in the interview guide was geared towards uncovering

internal and external influences that the interviewee felt relevant to family-run wineries giving insight into their CSR practices. All questions were designed to allow interviewees the freedom to give in-depth feedback, allowing for personal perspectives. Personal perspectives were often given more freely by family members than non-family members. The interview guide questions were designed to allow the interviewees to disclose facts and include opinions and perceptions related to CSR practices. The execution of the questions was dependent on the researcher conducting the interview, while the questions varied from interview to interview, dependent on the information provided by the interviewee.

The initial interview guide was pilot tested with threepeople, two business owners of which two ran a

family business. The interview guide test participants provided instructional counsel on the direction of questioning. As an example, a test participant alerted to a potential hindrance. They pointed out that other interviewees may not necessarily reveal family operational succession plans as succession plans are private, or they simply are not finalized or discussed. They set an expectation that access to specific information could be hindered due to a one-time conversation and a lack of personal rapport.

The interview guide is located in Appendix A. The confidentiality and consent terms are located in Appendix B. All consent forms were agreed upon verbally at the beginning of each interview. Transcriptions of the interviews were made in the language of the interview. These transcriptions of relevant interview passages are available upon request.

3.3.2 Semi-structured interviewing

The research utilized a semi-structured interviewing method to obtain critical data and understanding. The selection of semi-structured interviewing is a widespread method used among researchers and can easily be applied to qualitative research. Semi-structured interviewing was chosen based on its flexibility

tobe spontaneous during the interview process by adapting questions based on the interviewee’s answers

(Brinkman & Kvale, 2018). Due to the inherent character of the research topic, understanding the personal experience of individuals closest to winemaking lends itself to the accuracy of the interview. The data collection methods and the logic behind the choice of semi-structured interviewing and coding are discussed below. Table 1 provides details of the format of the responses from the data collection and denotes whether the interviewee is a family member or non-family member employee, the interviewee’s role, and the geographical location of each winery.

The semi-structured interview was designed to flow smoothly and naturally, however short or long the responses may be. A range of 35-minutes to 1 hour 15 minutes was expected for each interview, with the majority falling around 45-50 minutes.

After the initial email or LinkedIn invitations to participate in the research interviews were acknowledged, a choice of online platforms was given. Zoom, WhatsApp, and FaceTime were offered, all of which provided video displays in addition to audio. Logistically, due to Covid-19 and imposed travel restrictions, online interviews were the best option due to the geographical constraints of the researchers and interviewees. Researcher 1, located in Lund, Sweden, was assigned to the US, and researcher 2, located in Göd, Hungary, was assigned to the Hungarian wineries. All research occurred during the Covid-19 pandemic from April 2020 to August 2020.

The online platforms provided a relaxed and comfortable environment for both the interviewer and interviewee, avoiding hassles of travel and being in one’s own space. All interviewees provided a confidentiality agreement giving verbal consent at the beginning of the recorded interview. Recorded conversations lasted between 25 minutes and 1 hour and 15 minutes. All interviews were transcribed using the language of the interview. The Hungarian interviews were translated via Google Translate for researcher 1 to review. The quotes from the Hungarian interviewees used in the analysis chapter were reviewed for semantics, syntax, rhetoric, pragmatics, and grammar to avoid misinterpretation by

interview guide was emailed to the participant. The advantages of using a questionnaire include no interviewer variability and convenience for the participant to complete the questionnaire at their free will. The disadvantage of using the questionnaire is that the interviewer cannot alter the questions to fit the responses and that the participant responder may tire of completing the questionnaire.

3.4

Data analysis

Nine interviews were conducted via Zoom, FaceTime, or Skype using video communication. Interviews ranged in time from 35 minutes to 1 hour 15 minutes. Researcher 1 interviewed 4 participants in the United States. A fifth participant interview was arranged but was canceled. To supplement the lost interview, researchers used document analysis of the winery’s website, social media content, and published materials. Researcher 2 interviewed 3 participants in Hungary. Two additional participants in Hungary indicated a preference to provide a written response. Document analysis was used for all interviewed wineries to support the data provided from the interviews.

Interviews were transcribed by hand in the language in which the interview was conducted, English and Hungarian. Following transcription, coding was conducted by hand using thematic analysis. Thematic analysis of the data aids in the identification of recurring patterns and locate commonalities in themes. Logical reasoning using inductive methods (Silverman, 2015) was used to develop the questions in the interview guide. Outcomes of the interviews were hypothesized to fall within a range of expected outcomes based on data from primary research.

Thematic analysis is used to identify, analyze, and interpret patterns of meaning within qualitative data (V. Clarke & Braun, 2016). Thematic analysis is a tool used to identify patterns within and across data relevant to the participants’ experience, perspectives, behavior, and practices. The research seeks to understand what participants think, feel, and the actions they take.

Multiple steps were used as recommended by Boyatzis (1998) to analyze the data using thematic analysis. First, creating preliminary codes based on theory prior to the interviews. After interviewing, the transcriptions allowed for further familiarization of the data. Next, the coding of the data was completed manually. After transcription, additional codes were created for data that did not fit the preliminary codes. Themes were then identified through the consolidation of codes.

A preliminary codebook, created as a spreadsheet, included the following codes: “formative

experiences,” “employee relations,” “family relations,” “environmental responsibility,” “social responsibility,” “expectations,” “values,” and “philosophy.” These codes were developed to correspond

with the interview guide questions associated with institutional theory, stakeholder theory, and CSR. Through multiple discussions and iterations of the spreadsheet, themes emerged agreed upon by both researchers. These themes are presented in the following Findings and analysis chapter. The final codebook is available in Appendix D.

3.5

Limitations

Consideration of the limitations is necessary to understand the process of this study. Firstly, a limitation of this research is the lack of personal meetings with interviewees. Due to the COVID-19 lockdowns, the possibility of conducting the interviews face-to-face was not an option. The researchers were challenged to obtain more personal information about the familial, organizational structure without conducting multiple interviews, building trust, and rapport.

Secondly, due to the wide-reaching social and economic impact of the pandemic COVID-19, family-run wineries experienced exceptional challenges that may influence who was made available to interview. The study’s initial plan was to interview family members; however, family members were not always offered as interviewees. We are grateful to those wineries who did have the time and staff who accepted interview requests.