“I see it as my damn responsibility to

do what I can so that people become

aware of what is happening”

A narrative study about individual perception on

climate change

Authors: Julia Sjökvist & Belinda Medic

Bachelor of Science with a Major in Environmental Science Miljövetarprogrammet: människa, miljö, samhälle

15 Credits Spring 2020

2

Abstract

Climate change is one of the biggest threats towards humanity, and the consequences of climate change will increase in magnitude and severity as global warming intensifies. This leads to imminent risks to many areas of society. To keep global warming below 2 °C, major mitigation measures will need to occur in the near future. In this, individuals have an important role. How individuals perceive risk are of importance in order to understand their reactions to them. A majority of Swedish people no longer doubt that climate change is occurring. However, there is still a lot to be done on the individual level, as the households in Sweden stands for 60 % of the nation's total greenhouse gas emissions. At the same time, it is argued that there is an increased pressure from civil society, both when it comes to public activism and engagement in climate change. Based on the urgency in mitigating climate change, the aim of this study is to better understand how individuals with an interest or engagement in climate change perceives climate change and its associated risks and what their road to engagement has looked like. Furthermore, the aim is to better understand how their view, according to them, has evolved and how this view is expressed cognitively, emotionally, and behaviorally with the help of a narrative life-history method. The hope is to gain an understanding of the factors that have been key in their engagement with climate change, as this can bring insight to important components in fostering climate change awareness and engagement in the issue. Results demonstrate that climate change is perceived as a moral concern, linked to issues of justice. Critical events have led to an increased awareness of these issues. When consequences of climate change are grasped, the threats they pose to valued objects of care and core values triggers emotional responses, raised risk perception and activates personal norms leading to feelings of personal responsibility. Eventually these factors, along with others, have led to different engagements in climate change, which many times have been a gradual process.

Keywords: Climate change, risk perception, perception, engagement, mitigation,

pro-environmental behavior

3

Sammanfattning

Klimatförändringarna är ett av de största hoten mot mänskligheten, och konsekvenserna av klimatförändringarna kommer öka både i omfattning och allvar i takt med att den globala uppvärmningen intensifieras. Detta leder till överhängande risker mot många områden i samhället. För att den globala uppvärmningen ska hållas under 2 °C måste omfattande ske inom en snar framtid. I detta har individer en viktig roll. Hur individer upplever risker är viktigt för att förstå deras reaktioner gentemot dem. En majoritet av det svenska folket betvivlar inte längre att klimatförändringarna sker. Däremot finns det fortfarande mycket som måste göras på individnivå, eftersom hushåll i Sverige står för 60 % av nationens totala utsläpp av växthusgaser. Samtidigt argumenteras det att det finns en ökad press från samhället, både när det kommer till aktivism och engagemang i klimatfrågan. Baserat på brådskan i att mildra klimatförändringarna är målet med den här studien att få en bättre förståelse för hur individer med ett redan uttalat intresse eller engagemang om klimatförändringarna upplever dessa och risker kopplade till dem samt hur deras väg mot ett engagemang har sett ut. Vidare ämnar den även undersöka hur deras syn, enligt de själva har utvecklats samt hur denna synen tar sig uttryck kognitivt, emotionellt och beteendemässigt med hjälp av en narrativ livshistoriemetod. Hoppet är att få en ökad förståelse för de faktorer som har varit viktiga i detta engagemang eftersom det kan skapa inblick i de viktiga komponenter som krävs för att främja medvetenhet om klimatförändringar och engagemang. Resultaten visar att klimatförändringarna uppfattas som en moralisk oro som är starkt sammankopplad med rättvisefrågor. Kritiska händelser har lett till ett ökat medvetande om problemet. När konsekvenserna om klimatförändringarna omfamnats har hoten som uppvisas gentemot objects of care och ens kärnvärderingar triggat känslor, ökat ens riskperception och aktiverat personliga normer som lett till känslor av personligt ansvar. Så småningom har dessa faktorer, tillsammans med andra lett till olika typer av engagemang, vilket många gånger har varit en gradvis process.

Nyckelord: Klimatförändringar, riskperception, perception, engagemang, mildrande, ett mer

4

Table of Content

1. INTRODUCTION ... 6

1.1 AIM OF STUDY AND RESEARCH QUESTIONS ... 7

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ... 8

2.1. RISK PERCEPTION: THE CLIMATE CHANGE RISK PERCEPTION MODEL ... 8

2.1.1. Cognitive factors: knowledge ... 9

2.1.2. Experiential processing: holistic affect and emotion ... 9

2.1.2.1 Emotional aspects in addition to CCRPM ... 9

2.1.3. Experiential processing: personal experience ... 10

2.1.4. Socio-cultural influences: value orientations ... 10

2.1.5. Socio-cultural influences: social norms ... 11

2.1.6. Sociodemographics ... 11

2.2. PERSONAL NORMS ... 12

2.3. CONNECTEDNESS TO NATURE ... 12

2.4. DISSONANCE AND DENIAL ... 13

2.5. PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTANCE ... 14

2.6. ENVIRONMENTAL AWARENESS ... 15

3. CLIMATE CHANGE PERCEPTION AND RISK PERCEPTION IN PREVIOUS STUDIES ... 16

3.1. CLIMATE CHANGE AS A DISTANT RISK ... 16

3.2. LOCUS OF CONTROL AND PERCEIVED EFFICACY ... 18

3.3. MORALITY AND ETHICS ... 19

3.4. PERSONAL NORMS ... 20

3.5. SOCIAL NORMS ... 21

3.6. VALUES ... 22

3.7. CONNECTEDNESS TO NATURE ... 24

3.8. DEMOGRAPHICS, EXPERIENCE AND KNOWLEDGE ... 25

3.9. CLIMATE CHANGE RISK PERCEPTION AND PEBS ... 27

4. METHOD ... 29

4.1 METHODOLOGICAL OVERVIEW: THE NARRATIVE APPROACH AND LIFE-HISTORIES ... 29

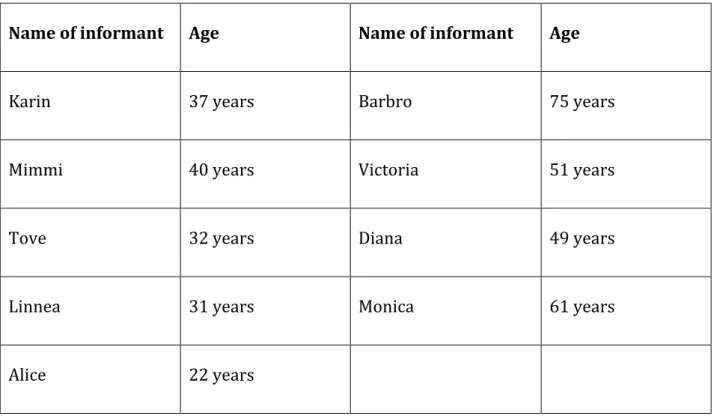

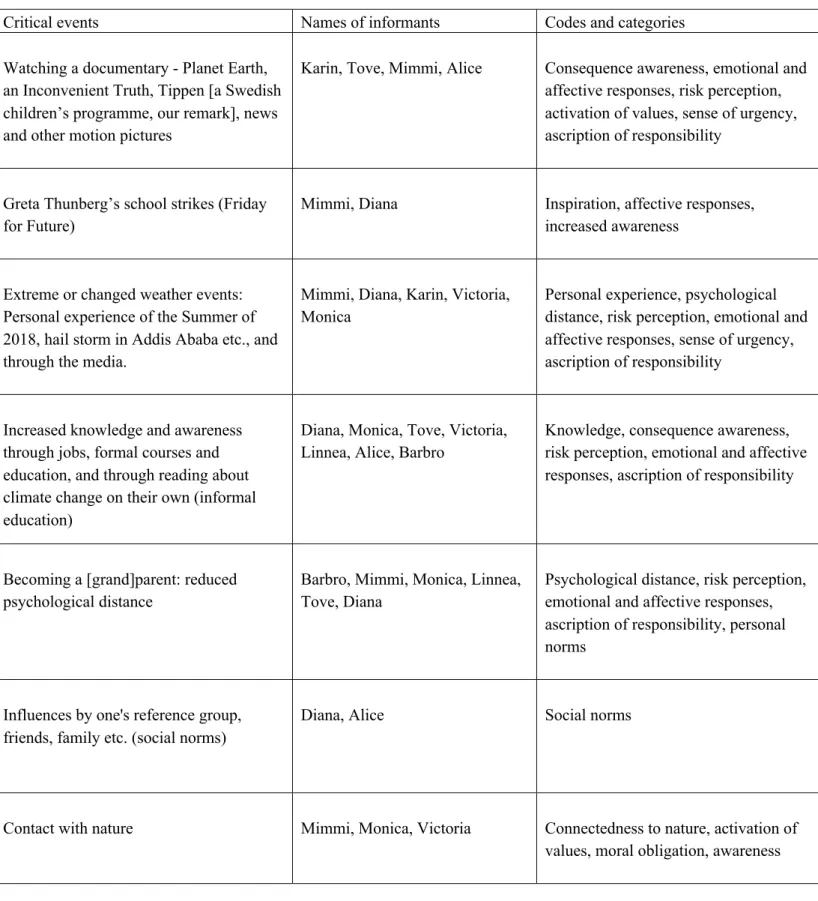

4.2. SAMPLE ... 30

4.3. EXECUTION ... 32

4.4. ANALYSIS: CODING, CATEGORIZING AND THEMATIZING ... 33

5. RESULTS AND ANALYSIS ... 34

5.1. CONNECTEDNESS TO NATURE ... 35

5.2. CCRPM SOCIO-CULTURAL INFLUENCES: VALUE ORIENTATIONS AND JUSTICE ... 37

5.3. CCRPM SOCIO-CULTURAL INFLUENCES: SOCIAL AND PERSONAL NORMS ... 40

5.4 CCRPM COGNITIVE FACTORS: KNOWLEDGE ... 41

5.5. CCRPM EXPERIENTIAL PROCESSING: AFFECT AND EMOTION ... 45

5.5.1. Consequence-based emotions and objects of care ... 45

5

5.6. CCRPM EXPERIENTIAL PROCESSING: PERSONAL EXPERIENCE ... 50

5.7 PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTANCE ... 51

5.8. DENIAL AND DISSONANCE ... 54

5.9. A GRADUALLY INCREASED AWARENESS AND GREATER ENGAGEMENT IN CLIMATE CHANGE - A ROCKY ROAD TO MITIGATIVE ACTION ... 56

6. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS ... 59

6.1 METHODOLOGICAL DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH ... 63

7. REFERENCES ... 65 APPENDIX I ... 78

6

1. Introduction

Climate change is one of the biggest threats towards humanity, and the consequences of climate change will increase in magnitude and severity as global warming intensifies (Hu & Chen, 2016; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC], 2018). Anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions have already caused an estimated global warming of 1 °C since pre-industrial times (IPCC, 2018), and new temperature records continues to succeed one another, with 2010-2019 being the warmest decade recorded to date (Sveriges meteorologiska och hydrologiska institut/the Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute [SMHI], 2020). When the global mean surface temperature (GMST) increases, processes such as desertification, land degradation, ocean acidification and food security are affected. This leads to imminent risks to food systems, infrastructure, livelihoods and ecosystem health, among other areas of society (IPCC, 2018; IPCC, 2019). As a response to the pressing threat of climate change, international policymakers have pledged to keep global warming to 1.5 °C, or a maximum of 2 °C, in the Paris agreement (United Nations [UN], 2015). This will require major mitigation measures throughout a range of levels in society in the near future (IPCC, 2018).

The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency calculated that households in Sweden emit 60 per cent of the country’s total emissions of greenhouse gases (Naturvårdsverket, 2018). Therefore, they state that private consumption must change if Swedish climate goals are to be achieved (Naturvårdsverket, 2020). Individuals therefore have an important role in answering to the threats that result from climate change (Wolf & Moser, 2011). Still, awareness and concern vary among the public (Lee, Markowitz, Howe, Ko, & Leiserowitz, 2015; Spence, Poortinga & Pidgeon, 2012; Weber, 2010; Wolf & Moser, 2011).

A majority of Swedish people no longer doubt that climate change is occurring (Rohne, 2012), and a survey conducted in Sweden showed that a majority (86%) thought it important for society to implement measures to deal with climate change, and 78% believed that they themselves can mitigate climate change (Naturvårdsverket, 2018). However, even though there's a will to mitigate climate change, there's still a lot to be done at the individual level. One reason for the absence of significant mitigative behaviors, could be that the risks of climate change are surrounded by uncertainty and that climate change is a slow process not yet noticeable to the majority (Choon, Ong, & Tan, 2019). This contributes to the perception of climate change as a distant threat, which

7

can hinder people's sense of urgency and willingness to act (Choon et al., 2019; Weber, 2010). Perception is the way in which an individual understands, interprets and makes sense of the world (Steg, van den Berg & de Groot, 2013).

Böhm and Tanner (2013) state that “how people perceive environmental hazards [...] is crucial for understanding their reactions to particular risks” (p. 23), where risk is described as an event that results in negative consequences for something that humans’ value (Böhm & Tanner, 2013). How individuals perceive climate change is therefore key in understanding their willingness to adopt more pro-environmental behaviors (PEB; Capstick, Whitmarsh, Poortinga, Pidgeon & Upham, 2015; Lorenzoni & Pidgeon, 2006), that is, behaviors that aim to decrease a one's negative impact on the environment as a whole (Gatersleben, 2013). For a long time, the level of engagement wasn’t as high as it is today (Rohne, 2012). Hügel and Davies (2020) state that with an increased pressure from civil society, there now is increasing levels of both public activism and engagement connected to climate change.

1.1 Aim of study and research questions

Based on the urgency in mitigating climate change and the important role of individual perception of climate change in mitigative action, the purpose of this study is to get a better understanding of climate engaged individuals' and their perceptions of climate change as well as how they got to engage with the issue. The aim is also to better understand how their perceptions, according to them, have evolved and how this view is expressed cognitively, emotionally and behaviorally. This is done through the use of an inductive, narrative approach by the use of limited life-stories. Our research questions were:

- How do individuals with an interest in environmental- and climate change issues perceive climate change and its associated risks and how do they feel that their perception has evolved? - How are their views of climate change expressed cognitively, emotionally and behaviorally?

8

2. Theoretical framework

Our working procedure have been constituted by an inductive and grounded approach (Bryman, 2018) to the empirical material. The concepts presented in the following section have been identified in the informants’ stories when they were analyzed and thus works as the theoretical framework in this study.

2.1. Risk perception: The climate change risk perception model

As mentioned in the introduction, the research on risk perception of climate change has used different combinations of variables, methods and measurements leading to scattered results. van der Linden (2015) therefore presents the climate change risk perception model (CCRPM). The aim of the model is to systematically compile the most important variables in determining climate change risk perception based on previous research in the social-psychological arena. The CCRPM consists of four categories, or dimensions, which contributes to individual risk perception regarding climate change. These are cognitive factors, experiential processing, socio-cultural

influences and sociodemographic factors (van der Linden, 2015).

Figure 1. The Climate Change Risk Perception Model (CCRPM; van der Linden, 2015).

9

2.1.1. Cognitive factors: knowledge

Cognitive factors are related to knowledge about climate change (e.g. knowledge about the drivers of climate change, its consequences and what action to take to mitigate climate change). van der Linden (2015) argues that the mixed results from previous research on knowledge and climate change risk perception could be explained by the different measurements of knowledge. When people rank their own knowledge on a subject, without providing evidence for it, this has led to mixed results as individuals' knowledge is subjective, i.e. not necessarily based on science but rather what they believe is true. van der Linden (2015) provides support for this in referring to studies which have employed a more objective evaluation of respondents' actual knowledge. In contrast to the general, self-reporting measurements used in some studies, this shows that actual

knowledge about climate change does affect risk perception positively (van der Linden, 2015).

2.1.2. Experiential processing: holistic affect and emotion

Experiential processes are divided into two subgroups in the CCRPM. The first one is holistic affect, which is used to describe people's affective evaluation towards climate change, i.e. how they feel about climate change (e.g. positive/negative emotions). The role of affect and emotion when people process information has gained attention and interest in the scientific community and is increasingly used in risk perception studies as well, where it has provided evidence as a predictor to risk perception (van der Linden, 2015; Böhm & Tanner, 2013). In van der Linden's (2015) study, where the CCRPM was tested, holistic affect was shown to be the variable with the greatest influence on risk perception.

2.1.2.1 Emotional aspects in addition to CCRPM

Related to the concept of affect, but not included in van der Linden's (2015) CCRPM, is the emotional reactions produced by environmental risks. For example, different emotions impact risk perception differently. Böhm and Tanner (2013) gives the example of fear leading to a higher risk perception, as this emotion is connected to the feeling of an event being uncontrollable, whilst anger is connected to the feeling of the event being controllable and thus less risky. Böhm and Tanner (2013) further distinguish from consequence-based emotions and ethics-based emotions. Consequence-based emotions arise when individuals focus on the consequences of an environmental hazard, which can be prospective or retrospective. A prospective consequence-based emotion may be fear due to the anticipation of climate change leading to drought and lack of food. Retrospective emotions could for instance be sadness from the loss of a species due to climate change. When it comes to ethic-based emotions, those can be directed to the self or towards

10

others. For example, an ethic-based emotion directed at the self is guilt, which according to Böhm and Tanner (2013) is extra salient when it comes to individual behaviour such as releasing emissions when driving a car. Ethic-based feelings towards others may be rage directed when there is a more clear-cut ascription of responsibility towards someone, for example a company releasing toxic waste into a river (Böhm & Tanner, 2013).

2.1.3. Experiential processing: personal experience

The second subgroup in van der Linden's (2015) category of experiential processes is personal experience. Personal experience of a hazard can evoke strong emotional responses, which leads to the hazards being more prominent in memory. van der Linden (2015) writes that "[...] people's emotional reactions to risks often depend on the vividness with which negative consequences can be imagined or experienced" (p. 115). It has been shown in multiple studies that experience with extreme weather events or changes to the local weather pattern can influence risk perception, if those are attributed to climate change (van der Linden, 2015). However, due to the fact that the consequences of climate change is not yet experienced by the majority of people, media sources

can contribute to the affective responses people feel towards the issue (van der Linden, 2015).

2.1.4. Socio-cultural influences: value orientations

The third category in the CCRPM is socio-cultural influences which is divided into two sub-groups; value orientations and social norms. In the first subgroup, egoistic, socio-altruistic and biospheric value orientations are presented. Egocentric values are focused on maximizing the individual's self-interest, socio-altruistic values are concerned with other people's welfare, and biospheric values are connected to concern for non-human species and the intrinsic value of the biosphere itself (van der Linden, 2015; Aguilar-Luzón, Carmona, Calvo-Salguero & Castillo Valdivieso, 2020).

Values work as stable principles of guidance in an individual's life, and they play an important part in building beliefs and attitudes towards various social issues, climate change included (Milfont, Milojev Greaves, & Sibley, 2015; de Groot & Thøgersen, 2013; van der Linden, 2015). They reflect a goal state of how things should be in a somewhat abstract manner, thus they exceed specific situations and work as principles to guide a person's goals and behaviors in the long term. Several values can exist at the same time and competing values can be prioritized according to situation (de Groot & Thøgersen, 2013). Previous research has been consistent in proving that people with altruistic values are more concerned with environmental issues (Brown & Kasser, 2005; Corner, Markowitz, & Pidgeon, 2014; De Groot & Steg, 2007; Poortinga, Steg & Vlek,

11

2004). On the opposite, self-enhancing behavior, or egoistic values, are generally connected to lower levels of concern towards the environment (Steg & de Groot, 2012). Biospheric values are different from altruistic values in that they see nature and the environment as something with an intrinsic value, while altruistic values primarily reflect concerns with welfare of human beings. However, values of both altruistic and biospheric kind often make for a pro-environmental behavior [PEB], since actions like these mostly are beneficial to both the well-being of others and the environment (de Groot & Thøgersen, 2013). However, all three values can function to promote pro-environmental beliefs, norms and behavior (de Groot & Thøgersen, 2013).

2.1.5. Socio-cultural influences: social norms

Social norms is the second subgroup under sociocultural influences in the CCRPM. Risk perception is influenced by how risk is socially represented in people's lives, both by other people in society and by people in a close reference group (e.g. family and friends). Social, or subjective, norms concern behavior that is accepted or not accepted among the general public (Keizer & Schultz, 2013). They guide behaviors of individuals without being laws that must be adhered to. van der Linden (2015) makes use of both descriptive and prescriptive social norms in the CCRPM. Descriptive norms refer to the behavior that is shown by most members of a group (Keizer & Schultz, 2013), which in the case of climate change risk perception could be translated to to which extent others are taking mitigative action (van der Linden, 2015). Prescriptive norms, on the other hand, refer to the behavior that is accepted or not accepted in a group or in the society (Keizer & Schultz, 2013). As such, van der Linden (2015) proposes that how a person's reference group views climate change (i.e. whether it's a risk or not and whether or not action should be taken) will impact

that person's risk perception as well.

2.1.6. Sociodemographics

The last category in van der Linden's (2015) CCRPM is socio-demographic variables (e.g. gender,

political ideology, educational level and income), as these have proven to influence risk

perception. However, van der Linden (2015) states that "[g]iven the often inconsistent effect of

socio-demographics, they mainly serve as control variables here to assess the net influence of cognitive, experiential and socio-cultural factors on risk perception." (p. 117). On grounds of this, sociodemographic information is not collected in this research, other than age and gender, and this category is therefore not further considered in this thesis.

12

2.2. Personal norms

There is a second construct in the norm arena, namely personal norms. However, van der Linden (2015) does not include these in the CCRPM. Regardless, we believe that personal norms fill a purpose based on our collected material, and therefore choose to acknowledge them here as well. Personal norms are rules and standards that individuals base their own behavior on (Keizer & Schultz, 2013). These personal norms aim to explain an individual’s belief in his or her moral obligation to act or behave in a certain way, meaning that what an individual feel is right is also what forms the behavior. A feeling of strong moral obligations to act in a certain way can outweigh the social, normative pressures (Keizer & Schultz, 2013). Moral is, according to Kronlid (2005), when our moral values and norms are expressed through individual actions and our way of living, hence when we act in conjunction with what we perceive as right and just. Steg and Nordlund (2013) argue that four key variables activate personal norms. However, not all studies are in agreement about this, but instead argue that it is the personal norms that activate the key variables. The variables are ‘problem awareness’, which refers to an individual’s level of awareness about an issue, ‘ascription of responsibility’, which has to do with feeling responsible for possible negative consequences of not acting in a pro-environmental manner, ‘outcome efficacy’, which is about identifying possible actions to mitigate environmental problems and lastly, ‘self-efficacy’,

that has to do with an individual’s own ability to actually act (Steg & Nordlund, 2013).

2.3. Connectedness to nature

‘Connectedness to nature’ is a theoretical approach that begins with the belief that individuals gain purpose and meaning in their lives when they feel an emotional connection to nature and as a part of the natural world (Joye & van den Berg, 2013). It has been used when researching restorative environments (Joye & van den Berg, 2013), but also as a concept that represents the emotional connection individuals' feel towards nature (Baur, Ries, & Rosenberger, 2020). Baur et al. (2020) describes that connectedness with nature can be seen as the emotional affiliation a person has with nature, which often encompasses a feeling of nature being a part of the self. Integrating nature as a part of one's identity makes it a relative stable component in a person's self-concept, much like the function of value orientations (Baur et al., 2020).

Individual's connectedness to nature has proven valuable in many areas, for example when understanding attitudes towards environmental issues and PEB:s (Wang, Geng, Schultz, & Zhou, 2017; Bradley, Babutsidze, Chai, & Reser, 2020; Baur et al., 2020; Wang, Hong, Lin & Tsai, in press). There has been indications in previous studies that individuals with a stronger sense of a

13

connection with nature are less likely to devote themselves to behavior that might result in harm to the environment, since harming the environment is seen as harming themselves (Schultz, Shriver, Tabanico, & Khazian, 2004). Seppelt and Cumming (2016) writes that “contact with nature and environmental change is central to both our desire and our capacity to care for the environment” (p. 1649). This contact with outdoor environments is a central part in order to develop a connectedness to nature. It's especially important for children to experience nature if they are to form a personal relationship with it, which can follow them through life and promote PEBs (Colding, Giusti, Haga, Wallhagen, & Barthel, 2020).

2.4. Dissonance and denial

Dissonance and denial are two barriers that, according to Stoknes (2014), can hinder behavior change. If people’s actions do not comply with their beliefs, they can experience what is known as dissonance (Stoknes, 2014). Cognitive dissonance is defined as an unpleasant feeling resulting from the tension when an individual’s actions does not align with their attitudes (Abrahamse & Matthies, 2013; Nilsson & Martinsson, 2012). Often, people try to eliminate the feeling of dissonance by changing their behavior, attitude or beliefs (Nilsson & Martinsson, 2012; Stoknes, 2014). More often than not, people do what is easiest for them at the moment (Nilsson & Martinsson, 2012). Continuously, Stoknes argues that dissonance paves the way for denying climate change.

Stoknes (2014) describes denial as “[...] a powerful defense mechanism” (s. 164), and psychoanalysis research have shown that humans often experience a resistance when faced with “[...] harsh and ugly realities” (s. 164). It can be seen as a sort of wishful thinking when one otherwise would be overwhelmed with anxiety or shame. Earlier research has shown that it appears people stop paying attention to climate change when they come to the realization that there are no easy solutions to solve the problem. Denial mechanisms can be shown in the form of denying one's own responsibility, claiming to be powerless in the issue or fabricating constraints (Stoknes, 2014). Responses of this kind to an issue like climate change can for example help lower feelings of guilt and support feelings of victimization (Stoll-Kleemann, O’Riordan, & Jaeger, 2001). Within the concept of denial, one type of denial is what Stoknes (2014) calls passive denial. Within this type of denial, individuals are often aware of an issue but choose not to expose oneself to information that causes distress in order to reduce anxiety. Anxiety is often reduced by choosing not to expose oneself to information that causes distress (Stoknes, 2014).

14

2.5. Psychological distance

Climate change is often perceived as a distant risk on various psychological dimensions. These include perceived spatial (geographical), temporal (time), social (socially close or distant group) and hypothetical distance (uncertainty of occurrence; Spence et al., 2012; Stoknes, 2014; Trope & Liberman, 2010; Steynor et al., 2020). In the Construal-level theory of psychological distance, Trope and Liberman (2010) proposes that people are able to mentally experience the past, plan for the future and take hypothetical alternatives into account, through "[...] forming abstract mental construals [i.e. mental representations, our remark] of distal objects" (p. 1). They clarify saying that people make "[...] mental constructions, distinct from direct experience", and thereby that "[p]sychological distance is a subjective experience that something is close or far away from the self, here, and now" (Trope & Liberman, 2010, p.1).

The different distance dimensions are also interrelated (Trope & Liberman, 2010). Something that seems spatially distant (i.e. more drought periods in Kenya), also often seems socially distant, uncertain and temporally distant. Moreover, if something is perceived as psychologically distant the level of abstraction of which the object is perceived is higher and people also tend to put the object in broader and more general categories. Contrary, something that is psychologically proximal is perceived more concrete and with more detail and is also often more connected to emotional and cognitive engagement (Trope & Liberman, 2010; Steynor et al., 2020). According to Trope and Liberman (2010), people who have a distant mental representation of an event, also deem the event as less likely to happen in comparison to those with a proximal mental representation. Trope and Liberman (2010, p. 2) writes that the different distances of one's mental representations "[...] thus expand and contract one’s mental horizon", and furthermore that the different distances can affect prediction and behaviour, since the outcomes are mediated by the psychological distance (Trope & Liberman, 2010).

So, when 2050 is mentioned as a point in time when many of the worst effects of climate change is expected to occur and hit Bangladesh or future generations the hardest, this appear distant in temporal, spatial and social terms to many in the Western world (Stoknes, 2014; Spence et al., 2012). In addition, extreme events still occur as exceptions, while more normal weather still dominates, making it even harder for us to embrace (Stoknes, 2014). In summary, people often seem to label climate change as someone else’s problem, leaving it to be dealt with in the future. In terms of threats, the human body is good at responding if these threats are close and visible,

15

have been experienced before and result in serious consequences. However, when there is a distancing effect it is often deemed much less concerning (Gifford, 2011).

2.6. Environmental awareness

The definitions of environmental awareness have varied in previous research. For example, Lee et al. (2015) and O'Connor, Bord and Fisher (1999) uses 'awareness' of climate change and environmental issues as a simple measurement of whether people know about, meaning if they are aware or unaware, about the existence of climate change. However, environmental awareness (including both environmental issues and climate change more specifically) is in this study used to describe the level of awareness a person has of environmental issues on the cognitive and emotional level. Awareness is defined in the Swedish dictionary as having achieved a deeper insight about something and having reflected about it on a deeper level (Medveten, 2015; Medvetenhet, 2009). Insight is in turn defined as when someone has gained a deeper understanding of the causality of different causes and effects, something that is usually attained after conscious cogitation (Insikt, 2009). Coertjens, Pauw, Maeyer and Petegem (2010) writes that environmental awareness can show through one striving to increase their knowledge about something or when one shows a willingness to take action to help protect the environment.

16

3.

Climate change perception and risk perception in

previous studies

According to Poortinga, Whitmarsh, Steg, Böhm and Fisher (2019), the extensive literature on climate change perceptions has contributed “[...] to a better insight into how different individuals perceive and engage with climate change” (p. 25). Multiple studies have been conducted on risk perception, climate change and behavior for instance, but with varied results (e.g. Aitken, Chapman & McClure, 2011; Libarkin, Gold, Harris, McNeal & Bowles, 2018; Liobkienė & Juknys, 2016; Smith & Mayer, 2018). Libarkin et al. (2018) argue that not enough research has been done to ensure reliability and validity in how climate change is understood, and they point out that this has led to a gap in studies dealing with climate change risk perception. This might not be surprising, considering the complexity and magnitude of climate change which makes it relatively unique as an object of risk (Wang, 2017; Weber, 2010), which is also consolidated by van der Linden (2015), who states that “public risk perceptions of climate change are clearly complex and multidimensional” (p. 120).

3.1. Climate change as a distant risk

The risks of climate change are surrounded by complexity, uncertainty of occurrence and severity and often perceived as spatially, temporally and personally distant (Böhm & Tanner, 2013; Choon et al., 2019; Chen, 2019; Wolf & Moser, 2011). This can lead to climate change being viewed as a distant hazard (Böhm & Tanner, 2013). Wolf and Moser (2011) concurs, stating that the perception of climate change as a distant threat in developed countries now is considered "[...] generalized findings" (p. 548). This has implications for mitigative measures towards climate change, as the view of a threat as distant may lead to less motivation to act upon the risk (Choon et al., 2019; Steynor et al., 2020; Weber, 2010; Wolf & Moser, 2011).

Fischer, Morgan, Fischhoff, Nair and Lave (1991) found that when people saw a threat as direct and personal, in comparison to when threats were more diffuse, they were more willing to take action to mitigate these threats. However, when threats were deemed less threatening in a personal aspect but presented dangers to more distant social circles, they showed less motivation to act on the risk in question (Fischer et al., 1991). Similar results have been found in other research as well, where a reduced psychological distance to climate change increases risk perception or feelings of fear, which in turn increases willingness to act to mitigate climate change (Brügger, Morton, & Dessai, 2016; Fox, McKnight, Sun, Maung, & Crawfis, 2020; Jones, Hine & Marks, 2017; Lee,

17

Sung, Wu, Ho, & Shiou, 2020). This gives some weight to the importance of psychological distance. If something, such as a hazardous event, is perceived as psychologically distant it is considered in more abstract terms, whilst something that is psychologically proximal is perceived more concrete and with more detail (Trope & Liberman, 2010). According to Weber (2006), this is important, as something that is perceived as psychologically close is more connected to emotion and affect compared to something that is perceived as distant. Weber (2006) argued that this could be an explanatory factor in the absence of PEB:s, as she meant that the negative affect linked to the instant costs of behaving pro-environmentally, coupled with the perceived abstract hazard and distance of climate change, leads to a lack of emotion and concern regarding remote climate change.

However, Chu and Yang's (in press) results indicated that it was more effective to frame climate change consequences as risky when they were more distant in time and space, as the respondents' increased risk perceptions in these situations mediated the positive effect on intentions to mitigate climate change. When climate change was described as something proximal, it was better to highlight the respondents' self-efficacy (Chu & Yang, in press). Chu and Yang (in press) argue that risk perception might be experienced stronger when a threat is portrayed in more psychologically distant dimensions because risk perception often represents the overall image of a threat, which affects people's motivation to act on the risk, while self-efficacy becomes more important when the threat is proximal, due to the threat then being concretized and people therefore must feel that their actions are effective. Chu and Yang (in press) also point out that climate change is not a new and uncertain threat anymore, but rather a known and present hazard. They argue that this may be an explanation as to why previous research on risk perception often showed positive effects between risk perception and behavioral intentions, while recent research instead emphasizes self-efficacy as a more important component for engagement (Chu & Yang, in press). Steynor et al. (2020) researched how climate change was perceived by informants in three southern African cities. Their results showed that climate change was perceived in proximal terms, as the vast majority (almost 90%) thought that climate change already had affected them or their cities, and about 87% answered that they viewed climate change as a big or very big threat to their city and themselves personally. For example, many had experienced extreme weather events and anomalies and other consequences, such as drying crops and water shortages, which brought climate change closer and affected them personally. While it is not possible to say that a specific weather event is the result of climate change (Steynor et al., 2020; Howe & Leiserowitz, 2013), however, "[...] it is possible to experience the perceived manifestations of climate change through

18

the experience of extreme climate events" (Steynor et al., 2020, p. 6). Steynor et al. (2020) argue that their results, which showed that the vast majority found climate change to be real, a matter of great concern, in need of meliorative action and already happening, was a result of their perception of having experienced the consequences of climate change, thus impacting the psychological distance, especially on the spatial and temporal dimensions.

Another factor hypothesized to decrease psychological distance to climate change is becoming a parent (Thomas, Fisher, Whitmarsh, Milfont & Poortinga, 2018). Having children is proposed to increase concern for the future of one's children, possibly leading to parents perceiving future generations as more proximal moral objects to worry about (Thomas et al., 2018). Thomas et al. (2018) performed a longitudinal study in which environmental attitudes, willingness to change behaviour as well as self-reported environmental behaviours was researched on individuals before and after becoming parents. Furthermore, they also included individuals that already had scored high on environmental concern to see if having children only affected environmental attitudes and behaviors on people already concerned with the environment. Results did not support their main hypothesis, as having children was negatively correlated with self-reported PEBs and attitudes; thus, having a child reduced PEBs. Only one variable showed a positive effect, which was the will to behave more environmentally friendly among those already high in environmental concern. However, the correlations were weak. Thomas et al. (2018) discuss that their finding are in line with other research, where parenthood is linked with several obstacles to behave in a more sustainable manner, where many obstacles are of a practical nature, as parents might find themselves with less time and energy to act for the environment as "[...] the reality and pressures of raising a new child may outweigh the motivation for sustainability" (Thomas et al., 2018, p. 274).

3.2. Locus of control and perceived efficacy

Strong risk perceptions can evoke fatalistic views on climate change, which can lead to less engagement in the issue (Mayer & Smith, 2019; Kurisu, Kimura & Hanaki, 2019; Lorenzoni, Nicholson-Cole & Whitmarsh, 2007). Kurisu et als. (2019) results support this notion. In their experiment, participants were shown a film about climate change which was made to induce fear. Results showed that participants who saw this movie experienced an increased risk perception, but also that it had the smallest effect on their behavioral intentions due to a lower belief in self-efficacy (Kurisu et al., 2019). Participants in Xie, Brewer, Hayes, McDonald, & Newells (2019) study who had a low belief in climate action efficacy also showed low behavioural intentions,

19

however, unlike Kurisu et al. (2019), Xie et als. (2019) respondents with a low efficacy belief also had a lower risk perception.

Several other studies have researched efficacy and perceived self-control in individuals and emphasized the importance of individuals' belief in self-efficacy (Aitken et al., 2011; Brody, Grover, & Vedlitz, 2012; Gifford, 2011; Hall, Lewis Jr, & Ellsworth, 2018; Kaiser & Gutscher, 2003; Mayer & Smith, 2019; Pichert & Katsikopoulos, 2008; Wang & Lin, 2018; Xie et al., 2019). According to a study by Mayer and Smith (2019) an individual's perceived self-efficacy is more important than concern for climate change when it comes to if he or she will change behavior. Aitken et al. (2011) studied self-efficacy in relation to helplessness in individuals. Based on their results they argue that an individual's own contribution to try and mitigate climate change is not enough, causing the individual to feel more helpless towards climate change. Gifford (2011) found that perceptions of climate change as a global problem further increased beliefs that individual efforts of mitigation are not enough, as it will be seen as having little effect. Many studies have also researched individuals’ attitudes towards flood mitigation, as flooding is a consequence expected to increase in frequency due to climate change (e.g. Grothmann & Reusswig, 2006; Poussin, Botzen, & Aerts, 2014). In studies by Grothmann and Reusswig (2006) and Poussin et al. (2014) self-efficacy has proven to be a powerful predictor for if one is willing to adapt a more mitigative behavior to lessen the risk of flooding.

Based on the findings from self-efficacy research above, its argued that climate change should be portrayed as a solvable problem that promotes the belief in collective and personal efficacy (Mayer & Smith, 2019; Kurisu et al., 2019; Steynor et al., 2020), and that risk perception is not as important for behavioral willingness as other factors not included in the CCRPM, such as efficacy beliefs, norms and perceived behavioural costs (Xie et al., 2019).

3.3. Morality and ethics

Wang (2017) found that risk perception of climate change impacted respondents' moral attitudes significantly when the risks were directed at other people or entities, but not when the risks were directed towards themselves. In contrast to this, personal risk did influence moral attitude and willingness to act in Wang and Lins' (2018) study. However, it is worth noting that personal risks in Wang and Lin's (2018) study included harm to oneself but also the respondents' in-groups (i.e. their community and society).

20

Wang, Leviston, Hurlstone, Lawrence and Walkers (2018) showed that people who displayed strong feelings towards climate change, such as fear, anger, sadness and optimism, also attributed more 'objects of care', i.e. valuable moral objects that may be negatively affected by climate change, than those who did not express as strong emotions. These valued objects included everything from planet earth, future generations, children, and the Great Barrier Reef (Wang et al., 2018). Those who displayed the most negative emotions (e.g. anger, fear) showed strong support for mitigative climate action, while those who only displayed weak feelings associated with climate change showed low support. Wang et al. (2018) concluded that whilst people's objects of care may differ, the emotions that the threat of climate change poses to these objects are alike and have a similar effect on support for action. Thus, the researchers meant that the emotions per se are not the reason for a specific behavior, but rather the result of a threat to something that people value. As such, Wang et al. (2018) concluded that communication with a focus on the valuable objects that are at risk by climate change possibly could bridge the psychological distance to climate change and provoke emotions and actions in favor of the climate.

3.4. Personal norms

Previous studies have found that personal norms are important to understand PEBs (Thøgersen, 2006). This is established in Chen's (2019) study, where personal norms were revealed as a key factor for the Taiwanese publics’ intention to adopt PEBs. As such, Chen (2019) underlines the necessity to promote and activate a sense of personal, moral responsibility to facilitate sustainable behaviours. The positive effect of personal norms on risk perception and PEBs have been found in several other studies as well (e.g. Ru, Qin, & Wang, 2019; Sia & Jose, 2019; Wolf & Moser, 2011; Wang, 2017; Yu, Chang, Chang & Yu, 2019). Yu et al. (2019) stated that individuals are more likely to engage in PEBs and work to avoid risks caused by climate change when they have “strong personal responsibilities towards the environment” (p. 25185), something that can also be characterized by strong, personal norms. A study by Dietz, Dan, and Shwom (2007) showed that individuals who showed a higher personal norm for taking action also showed greater willingness to support climate change policies. The same applied in Ru et als. (2019) study, in which personal norms were important amongst young Chinese people in terms of behavioral intention and attitude towards reducing their contribution to particulate matter pollution. Ru et al. (2019) also discussed that their respondents' personal norms may have been influenced by social norms, as their results showed that social norms had an indirect impact on behavioural intentions through personal norms.

21

Further, many previous research has studied personal norms in public transport as opposed to car use. Bamberg, Hunecke and Blöbaum (2007) writes that when it comes to understanding the roles of personal norms, looking closer at an individual's everyday travel mode is interesting due to the fact that in industrial societies, reducing fuel that is related to transport is important for reaching set goals to protect the environment. Bamberg et al. (2007) further argue that if enough evidence can prove a positive correlation between personal norms and what mode of transport one chooses, this is something that most likely can be applied to understand other PEBs as well. Bamberg et al (2007) concludes that when one becomes aware of the negative impacts one’s car has on the environment, feelings of guilt are often evoked. This in turn led to the individuals’ who took part in the study to feel obligated to choose more environmentally friendly modes of transportation (Bamberg, 2007). However, a study by Koestner, Houlfort, Paquet and Knight (2001) showed that personal norms which were supported by guilt were not always the best to initiate a change towards a more PEB. In relation to this, findings show that the strength of personal norms has much to do with how aware one is of the potential consequences of performing or not performing the behavior in question (see e.g. Nordlund & Garvill, 2003). Thøgersen (2006) showed that personal norms are not always internalized in individuals. This can happen when feelings of e.g. guilt as a result of a behavior occur, as opposed to when personal norms have become more internalized and a part of an individual’s self-concept (Thøgersen, 2006). Harland, Staats and Wilke (1999) tested, in addition to choosing other means of transportation than the car, the effect of personal norms on other PEBs, such as using unbleached paper, reducing one’s meat consumption, using energy-saving light bulbs and turning off water while brushing teeth. They too showed that personal norms contributed to all of these behaviors (Harland et al., 1999).

3.5. Social norms

Social norms also play an important role in PEBs. When an individual identifies with social norms, studies have shown that these individuals are more likely to partake in a behavior that is more pro-environmental (e.g. Yu et al., 2019). A study by Lo (2013) found that social norms were more influential than risk perception in a study involving an Australian population and their feelings towards flood insurance. A dominant view in studies on social norms is that they influence how climate risk is perceived (Grothmann & Patt, 2005; Renn, 2011). However, van der Linden (2015) argues that “[...] relatively little quantitative research has investigated the role of social factors in shaping individual risk perceptions of climate change” (p. 121). Results from prior studies have indicated, however, that risk perceptions of climate change are influenced by both prescriptive and descriptive social norms. Renn (2011) therefore argues that when important people close to an

22

individual (i.e. their reference group) act in a certain way, the more that individual is influenced to perceive issues in the same way.

Findings on the relationship between risk perception and social norms does not appear to be linear (Lo, 2013). Lo (2013) argue that knowledge on the connections between social norms, risk perception and related behavior should be further researched but that social norms can work as a mediator between perceived risk and the way in which an individual respond. Henceforth, Lo (2013) argues that “[s]ocial norms may act as a subjective filter determining the ways in which perceived risk is responded to” (p. 1256). Frank, Eakin and López-Carr (2011) moreover observed that in a study of a group of farmers, risks resulting from climate change were not motivation enough to take actions to change behavior, unless risk-information came from a reference group. This could be either a trusted out-group (a group to which the individual isn’t necessarily closely connected) or an in-group (an individual's own group, such as family or friends).

A study by van der Linden (2015) showed that descriptive and prescriptive norms were a predictor for risk perception in the studied population. Various other studies have researched norms in relation to risk perception. Xie et al. (2019), for example, researched socio-cultural influence on an individual’s perceived level of risk. Their results showed that descriptive norms were the ones that mainly affected to what degree individuals perceive a risk. When willingness to change their behavior then was studied, Xie et al. (2019) noted that prescriptive norms influenced decisions to a higher degree than descriptive norms did. The previously mentioned study from van der Linden (2015) however, shows that descriptive and prescriptive norms affect risk perception to the same degree. Zhu, Yao, Guo & Wang (2019) also emphasize social norms, saying that respondents in their study experienced a strong impact from individuals in their reference group (Zhu et al.,

2019).

3.6. Values

Research have shown that there is an association between pro-environmental values and a belief that climate change is anthropogenic (Poortinga, Spence, Whitmarsh, Capstick, & Pidgeon, 2011; Whitmarsh, 2011), but also a greater concern for climate change in general, how one perceives threats from climate change and if this leads to engagement in mitigative behavior (Whitmarsh, 2008). These findings are similar to other studies (e.g. Brody, Zahran, Vedlitz, & Grover, 2008; Kellstedt, Zahran & Vedlitz, 2008). Stern, Dietz and Kalof (1993) identified three value orientations that protrude in the environmental domain; social-altruistic, biospheric and egoistic

23

values. The meaning of these tend to be the same within cultures, but they are often prioritized differently by individuals (Steg & De Groot, 2012).

Bardsley et al. (2018) stresses the importance of understanding and developing knowledge on the connection between climate change perceptions and views on environmental risks and values, saying that it is important for policy making and for risks to be communicated accordingly. On the topic of values, Steg, de Groot, Dreijerink, Abrahamse and Siero (2011) highlight the importance of values for predicting environmental behavior. Previous research has mainly shown that biospheric values are closely connected to PEBs (e.g. Steg et al., 2011; Van der Werff, Steg & Keizer, 2013), and Slimak and Dietz (2006) points out how ecological awareness and feeling concerned for nature have proven important in understanding public perception of risk. In a study by Aksit, McNeal, Gold, Libarkin and Harris (2017), performed on a student sample, there was a positive correlation between knowledge of climate change and biospheric values. In the same study it was also proven that individuals who had a stronger belief in biospheric values appeared to perceive risks connected to climate change higher (Aksit et al., 2017). However, egoistic, altruistic and biospheric values can all function to promote pro-environmental beliefs, norms and behavior (de Groot & Thøgersen, 2013). For example, people with egoistic values might reduce their car use because they feel like the financial costs for driving are too high, but this simultaneously leads to less emissions being released (de Groot & Thøgersen, 2013).

In van der Linden's (2015) study, biospheric values were the ones that mainly worked as a predictor for risk perception. Along with descriptive and prescriptive social norms, biospheric values explained 16 percent of the risk perception variance found in the study. However, van der Linden (2015) concluded that the CCRPM had a greater and significantly better fit when it was divided into a two-dimensional structure, where risk on the personal and societal level was separated. When this was executed, egoistic value orientations turned out to be a significant predictor of personal but not societal risk perception, a result reflecting that self-centered individuals often feel mainly for themselves, and not society as a whole (van der Linden, 2015). Biospheric values were a predictor of both societal and personal risk perception, whilst social-altruistic values showed no significant correlation with either. van der Linden (2015) suggests that a possible reason for this is the strong correlation between altruistic and biospheric values. He argues that the biospheric values are more likely to be salient and activated in the environmental domain while "[...] altruistic values are unlikely to add any additional variance, unless both value orientations are in conflict" (van der Linden, 2015, p. 122). Indeed, individuals can prioritize values differently when values are in conflict with each other (de Groot & Thøgersen, 2013). For example, Schwartz (2009) points

24

to the role of pro-social values (e.g. altruistic values) in motivating prosocial behavior. He explains that values that are prominent to an individual are important for their self-image. As such, performing an action that is in line with a person's prioritized and most important values evokes positive feelings, and vice versa (Schwartz, 2009). However, Schwartz (2009) note that people, often unconsciously, make cost-benefit assessments of the considered behavior. If there isn't a clear outcome from this deliberation, an internal conflict occurs. When this happens, Schwartz (2009) states that people tend to diminish their prosocial values and personal norms through mechanisms aimed at construing the situation differently, such as perceiving less gravity in the situation and lessen one's own responsibility. Schwartz (2009) concludes that prosocial behavior usually is more high cost than its alternatives and thus that "[m]uch prosocial behavior requires planning and persistence" (p. 234).

3.7. Connectedness to nature

Connectedness to nature has been researched in many studies in connection with PEBs and environmentally friendly attitudes and identities (e.g. Restall & Conrad, 2015). Martin and Czellar (2017) performed an extensive study in which human-nature relationship was studied in its relation to biospheric values. Results indicated that connectedness to nature could work as the basis for the development of biospheric values, which in turn worked as a mediator between human-nature relationship and PEBs (Martin & Czellar, 2017). As such, they suggest that there exists a possibility that people who have integrated nature as a part of themselves and created a relationship with it are more likely to adhere to biospheric value orientations later on. Martin and Czellar (2017) therefore argue that contact with nature is important for building a bond with it. They further highlight that this should be promoted by policy makers, as this could work as a building foundation for biospheric values and by extension also PEBs. It's generally agreed upon that experience and contact with nature, not least during childhood, is important for building a connectedness to nature (Colding et al., 2020; Martin & Czellar, 2017; Restall & Conrad, 2015; Seppelt & Cumming, 2016; Wang et al., in press). As urbanization increases, nature experience and knowledge of the ecosystems that uphold humanity have diminished (Colding et al., 2020; Restall & Conrad, 2015; Seppelt & Cumming, 2016), something that Restall and Conrad (2015) write could lead to negative consequences for people's relationship with nature and thereby people's concern and care for the environment. Consequently, many scholars point to the importance in decreasing the distance people have to nature to foster a connectedness with it, which could emerge as an important component for shaping environmental attitudes, values,

25

conservation behaviours and PEBs (Baur et al., 2020; Colding et al., 2020; Martin & Czellar, 2017; Petersen, Fiske, & Schubert, 2019; Wang et al., in press).

3.8. Demographics, experience and knowledge

How risk is perceived has been shown to vary depending on different factors (Kim &

Wolinsky-Nahmias, 2014). Carlton and Jacobson (2013) state that risk perception, unlike risk assessments

done professionally, rarely are rationally grounded. Mayer, O'Connor, Shelley, Chiricos and Gertz (2017) supports this notion, as their results lend some evidence of risk perception being socially constructed. In their study, proximity to, and experience of, climate change and environmental risks rarely increased risk perception or policy support in significant ways, but rather political ideology and subjective factors such as risk tolerance were bigger predictors of policy acceptance and risk perception (Mayer et al., 2017).

As the perception of risk is subjective, what individuals therefore perceive as a threat vary widely (van der Linden, 2015). For example, climate change is generally less often perceived as threatening in developed countries compared to countries still developing (Kim & Wolinsky-Nahmias, 2014). Indeed, Lee, Markowitz, Howe, Ko and Leiserowitz (2015), who researched climate change awareness and risk perception in 119 countries, found that awareness of climate change varied greatly between developed and developing countries. Over 65 percent of the respondents in many developing countries, for instance in Asia and Africa, stated that they had never heard of climate change (Lee et al., 2015). However, Lee et al. (2015) also found that among the respondents in developing countries who actually were aware of climate change, the perception of it as a threat to them personally was bigger than for those in the developed world. The differences could partly be explained with previous research which shows that people with fewer years enrolled on a formal education appear more doubtful to if climate change is caused by anthropogenic effects (Lee et al., 2015; Milfont et al., 2015), as the level of education has proven important for awareness and knowledge of climate change being anthropogenic and for predicting risk perception. In many African and Asian countries however, individual experiences of climate change, such as temperature changes, were important factors for risk perception of climate change. Furthermore, research shows a coherent pattern over demographic groups. For example, it seems to be the case that men and older age groups appear more doubtful to if climate change is caused by anthropogenic effects (Milfont et al., 2015). Generally, they also show less concern about the impacts resulting from climate change (Whitmarsh, 2011). While women generally show greater concern and PEB intentions than do men, O'Connor et al. (1999) found that older and educated

26

men were more likely to support environmental policies than women, while women showed greater intentions to take ameliorative measures in their private sphere. Thus, it is hard to generalize climate change risk perception due to many variations that are country-specific or, more correctly, contingent upon socio-economical, -cultural, and -geographical factors.

Several studies have also found that individuals who have more knowledge on climate change have reported to not feel as helpless towards climate change, and therefore perceive a lower level of risk (Aitken et al., 2011; Haller & Hadler, 2008; Shi, Visschers & Siegrist, 2015). However, it has also been shown that knowledge about the causes, effects and solutions of climate change impact risk perception positively and predicts PEB intentions (Bradley et al., 2020; O'Connor, 1999; van der Linden, 2015).

A common pattern found in other studies is that climate change often is mixed together with other environmental issues (e.g. Besel, Burke, & Christos, 2017; Bord, Fisher, O’Connor, 1998; Fischer et al., 2012). For example, some of the students in Besel et als. (2017) study mentioned ozone depletion when writing about climate change, and furthermore listed water saving measures and buying biodegradable products when suggesting behavioural solutions to climate change. Besel et al. (2017) thus concludes that the students in their study "[...] blend their responses to climate change risks and advocacy for solutions with a general, environmentally friendly orientation" (p. 72). Fischer et al. (2012) received a similar result. They conducted a qualitative interview study with over 200 informants from five European countries on their views on energy and the future, with the aim of gaining understanding of their view on climate change. Their informants didn’t separate different environmental issues from each other either. Instead, they discussed them in connection and in more broad, general terms, reflecting a view of climate change interrelated with a multitude of environmental and sustainability issues, such as ozone layer depletion, and waste management (Fischer et al., 2012). Bord et al. (1998) argue that this can be problematic as threats concerned with other environmental and social problems generally aren’t as pressing as threats that can result from climate change. Fischer et al. (2012) however, disagrees. They instead conceive it as an opportunity for communication on climate change and argue that the interconnectivity of different environmental issues expressed by many, must not represent ignorance, but could be the result of actively perceiving the issues as interrelated or evidence of a "generalized more synthetic and holistic way of thinking" (p. 174).

27

3.9. Climate change risk perception and PEBs

Several studies have found that perceived risk of climate change is one reason why people mitigate their behavior (Aitken et al., 2011; Chen, 2019; Lee, Tung, & Lin, 2019; Luís, Vauclair & Lima, 2018; Masud, Akhtar, Afroz, Al-Amin, & Kari, 2015; O'Connor et al., 1999; Xie et al., 2019). However, even when there are clear benefits from this change in behavior and an awareness of the problem, individuals many times do not take action. Reasons for this can be many, but Pichert and Katsikopoulos (2008) found that, for example, inertia and possible transaction costs connected to a behavior change can influence a decision as well as a belief that individual contribution will not matter. Indeed, some studies found no evidence of a connection between risk perception and behavioral intentions (e.g. Boehm et al., 2019; Choon et al., 2019; Hu & Chen, 2016). In Hu and Chen's (2016) study, young students participated in a focus group with elderly people over 60 years who talked about their own experiences of changes to the local weather patterns. After this, the students showed an increased risk perception and perceived self-efficacy, but risk perception had no effect on the students' increased intentions to reduce their impact on climate change. Despite this, topics related to increased risk perception was most frequently discussed by the students during the individual interviews that the researchers held with some of the students after the focus groups (Hu & Chen, 2016).

Aitken et al. (2011) show that the perceived risk variable is the strongest predictor for taking action towards issues that have occurred due to climate change, which is a result corresponding to studies made by Bord, O’Connor and Fischer (2000) and Haller and Hadler (2008). The strongest relationship that Aitken et al. (2011) found was between the two variables perceived risk and human influence on climate change. However, in contrast to Aitken et al. (2011), Kellstedt et al. (2008) found that individuals rated possible risks from climate change lower when they had a greater confidence in science.

However, in a majority of research found, risk perception showed a direct or indirect, mediating effect on behaviors and behavioral intentions, albeit to varying degrees (Bostrom, Hayes, & Crosman, 2019; Carrico, Truelove, Vandenbergh & Dana, 2015; Chen, 2019; Chu & Yang, 2020; Lacroix & Gifford, 2018; Lee et al., 2020; Masud et al., 2015; O'Connor et al., 1999; Wang, 2017; Xie et al., 2019; Xue, Marks, Hine, Phillips & Zhao, 2018; Yu et al., 2019; Yu & Yu, 2017). For example, some studies found that risk perception had a mediating effect through its positive effect on the respondents' attitude towards climate change (e.g. Masud et al., 2015; Yu & Yu, 2017), their environmental concern (e.g. Bostrom et al., 2019) and on social norms (e.g. Yu et al., 2019),

28

which in turn affected their behavioral intentions or climate policy support. In Lacroix and Giffords (2018) study, it was shown that risk perception had a mediating effect between worldviews, perceived barriers to mitigative behavior and self-reported energy saving, as the informants perceived less obstacles to energy saving when they showed a higher risk perception. Lacroix and Gifford (2018) therefore argued that an increased risk perception could be used to reduce the perceived barriers to energy saving behaviors, while at the same time promote other PEBs.

29

4. Method

4.1 Methodological overview: The narrative approach and

life-histories

The human mind makes sense of the world through different filters and experiences. Webster and Mertova (2007) writes that people usually make sense of their lives and surroundings in a narrative way. By this they mean that time is experienced in a narrative manner, in which critical events and experiences are organized in stories told to ourselves and others. Through narrative methods the researcher is thus provided with a wider picture of the informants’ perceptions of the world. Webster and Mertova (2007) say that “narrative inquiry attempts to capture the ‘whole story’, where as other methods tend to communicate understandings of studies, subjects or phenomena at certain points, but frequently omit the important ‘intervening’ stages” (p. 3-4). The strength of a narrative focus lies in its capacity to capture human experiences which are set in complex and culturally conditioned situations and its ability to gather a person's most influential events (Webster & Mertova, 2007). Personal stories are not an objective organization of life events, however, but rather the person's interpretation of his or her experience, making it "a rendition of how life is perceived" (Webster & Mertova, 2007, p. 3).

Narrative methods have grown and developed across different disciplines, all with their own methodological and philosophical worldviews. Therefore, Webster and Mertova (2007) states that there isn’t a single, definitive narrative method at the moment. Life history research is a narrative method that has been renowned since as early as 1920-1930 through the Chicago school (Öberg, 2011), and has gained momentum mainly during the last decades (Webster & Mertova, 2007). A life history is a documented story where an individual’s experience about life is reflected upon (Barnhurst, Besel, & Bodmann, 2011; Öberg, 2011). Through documents of personal stories, the reader is offered a possibility to understand a new perspective and put him- or herself in another person’s situation. Life history material can be collected in different ways, for example through biographies, letters, journals, and interviews (Öberg, 2011).

One way to analyze narratives is through the identification of so-called critical events. Critical events are defined by Webster and Mertova (2007) as memorable events in a person's life, which are of importance due to the impact they've had on that person's life. Usually, critical events have brought on a change in the person's perception of reality or led to a development of understanding.