A single case study exploring

mediatized activism:

How, why and with what consequences does the Danish

activist movement #hvorerderenvoksen make use of

Facebook as their primary communication channel?

Lill Hennschen

Media and Communication Studies: Master’s Thesis (One Year) Supervised by Pille Pruulmann Vengerfeldt

Abstract

This study aims to explore how the Danish grassroots movement #hvorerderenvoksen is shaped through the usage of Facebook as their primary communication tool. Using the embedded case study method, this thesis describes in detail how and why the movement arose and explains the role of Facebook’s features, primarily groups and sites, for the movements external communication. As such, it will become clear that using Facebook is not merely a means to an end. Being an activist on Facebook means using and being used, it entails the acceleration of mobilisation, but also disciplining activist action in accordance with Facebook’s terms and conditions. This thesis will draw upon modern communication theories such as mediatization and network media logic and analyse #hvorerderenvoksen as a digital social phenomenon. As will become clear, digitalisation and even more so datafication processes play a role when critically examining contemporary activism.

To sum up, this thesis aims to show how an activist movement is mediatized and strongly emphasizes the role of digitalization and media hybridity in this process. It suggests that future research will focus more on the influence datafication, and especially the collection of human data and its untransparent processing, has on mediatized activism.

Keywords: Mediatization, media logic, network media logic, Facebook, social media, digital activism, media hybridity, embedded case study, digitalisation, datafication.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction 4

1.1. Research questions 5

1.2. Thesis design 6

2. Context of #hvorerderenvoksen 7

2.1. Early Childhood Education and Care 8

2.2. Early Childhood Education and Care in Denmark 9

3. Theoretical Framework 11

3.1. Research Stance: Social Constructionism 11

3.2. Mediatization 12

3.2.1. What is mediatization? 13

3.2.2. Four phases of mediatization 14

3.2.3. Waves of mediatization 16

3.2.4. Digitalisation, datafication and deep mediatization 18

3.2.5. From media logic to network media logic 19

3.3. Four phases of mediatization revisited 22

4. Literature Review 24

4.1. Contemporary activism: what has changed? 24

4.2. What role does social media play for activism? 25

4.3. What are the consequences of using social media for activism? 26 4.4. How does social media change activism and activists? 28

5. Method and Methodology 30

5.1. Case Study Design 30

5.2. Data collection for #hvorerderenvoksen 32

5.2.1. Interviews 33

5.2.2. Unstructured Observation 35

5.2.3. Archival records 36

5.2.4. Documents 37

5.3. Ethical considerations and limitations 37

6. Analysis 40

6.1. The story of #hvorerderenvoksen: how did the movement emerge? 40 6.2. What identifies the movement as a (contemporary) activist movement? 46 6.3. What role does Facebook play for #hvorerderenvoksen’s communication

practices? 47

6.3.1. Virality is a digital tool for activism 48

6.3.2. Activism and media hybridity 48

6.4. What are the consequences for #hvorerderenvoksen when making use of

6.5. How can #hvorerderenvoksen be understood within the broader concept of

mediatization? 53

6.5.1. How is #hvorerderenvoksen placed in respect to the four phases of

mediatization? 56

7. Conclusion 57

7.1. Societal relevance and suggestion for further work 58

References 59

1. Introduction

The role of social media in contemporary activism, social movements and civic

engagement has become a focal point in media and communication studies. It is almost not possible to imagine one without the other as they seem to be increasingly

intertwined (Mortensen et al 2019, p. 156). Popular, globally active, social networking sites such as Twitter, Facebook and Instagram make it possible to reach, connect and mobilize vast amount of people in a short amount of time (Wang et al, 2016). In

connection to activism, they can be used to spread messages about unjust local, national or international circumstances fast and in a cost-efficient way (Wang et al, 2016). Altered forms of activism emerged on, or with the help of, digital platforms (Millward & Takhar, 2019). Global social movements such as #Occupy or the Arab Spring, hashtag activism such as #MeToo or #BlackLivesMatter, or national digital activism such as the Mexican student movement #YoSoy132 (Ramírez & Metcalfe, 2017) demonstrate the considerable relevance social media can have for civic protest. In addition, activism moved and transformed digitally. As such, civic participation found a whole new arena on social media (Kaun & Uldam, 2017; Svensson 2014), social

movements became networked social movements (Xiong et al, 2018; Schradie, 2018) and collective action transformed into connective action (Wang & Gao, 2016). However, recent studies warn that social media is not only used by us but is more and more using us. The hope for the golden digital age is fading away, and the world is observing a tipping point into, what is described as surveillance capitalism (Zuboff, 2019). This alarming view gets more attention and sparks discussions around

digitalisation, datafication and society. As such it is intriguing to study contemporary activism in relation to digital media and especially social media.

One way of analysing how (social) media is connected to activism is by looking at the studied case through the eyes of mediatization. Couldry and Hepp (2017) argue that our “social world is not just mediated but mediatized: that is, changes in its dynamics and structure by the role that media continuously (indeed recursively) play in its

is a social phenomenon were mediatization can be observed. As such, I will emphasize the role of social media for activism.

This thesis aims to explain and explore mediatized activism by applying an embedded single case study, which explores the Danish, Facebook-born, movement

#hvorerderenvoksen (Where is the adult?). #hvorerderenvoksen is a national parent movement demanding minimum standards (minimunsnormeringer) in Danish nurseries (0.5 -3 years old) and kindergartens (3-5 years old). Their demand is directed towards the Danish government. The movement criticizes the quality of Danish nurseries and kindergartens as they are lacking the staff to take proper care of children. The

movement mainly communicates to its members (followers and grassroots) via Facebook.

1.1. Research questions

By exploring the movement, my thesis aims to contribute to the ongoing discussion about social media and activism. My first question aims to shed light on the context of the movement and the role of social media in relation to activist communication and organisation. The second question aims to unfold the Facebook’s role in the movement. The third question will then place the movement within the theoretical framework of mediatization.

1. How did the movement #hvorerderenvoksen emerge and what role does traditional and social media play for the movement?

2. What role does Facebook play for #hvorerderenvoksen’s communication practices and in turn, what are the consequences for #hvorerderenvoksen when making use of Facebook's infrastructure?

3. How can #hvorerderenvoksen be understood within the broader concept of

mediatization and consequently, where is #hvorerderenvoksen placed in respect to the four phases of mediatization?

1.2. Thesis design

I will first provide a short introduction to the context of #hvorerderenvoksen, which compares the Danish daycare system with other European countries. This helps to place the movement’s relevance in a broader political spectrum. After explaining the

importance of the case, I will look at it through the lenses of mediatization and renew Strömbäck’s (2008) four phases of mediatization with network media logic. I will then review what has been studied in terms of social media and activism. The empirical data was gathered through the case study method. Within this method, I use the following data sources: direct observation, archival records, open-ended interviews and

documents. I approach my research question by multiple qualitative data sources, which according to Yin (2014) helps to construct validity and reliability. The analysis then aims to answer the three sets of research questions. The first part of the analysis is a narrative of #hvorerderenvoksen, which has been put together with the help of unstructured observations, archival records and documents. The second part of the analysis connects the main point of the literature review with the case (mainly interview) and the last part discusses the case in light of mediatization.

2. Context of #hvorerderenvoksen

Denmark is part of the European Union and has 5.781.190 inhabitants (Danmarks Statistik 2017, p. 11). The movement #hvorerderenvoksen is directed towards parents and potentially speaking to approximately 22% of the Danish population (Danmarks Statistik 2018, p. 7). With parents as the movements target group on the one side, the demand of the movement is also backed up by nursery workers and their unions.

Change in the total number of children 2008-2018

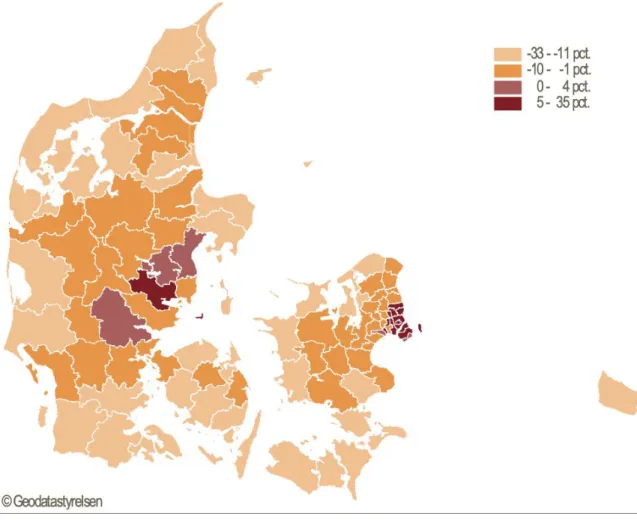

Figure 1. Change in the total number of children 2008-2018 in Denmark.

Reprinted from “Børn og deres familier 2018“, Danmarks Statistik, p. 12. Copyright by Danmark Statistik 2018.

Figure 1 shows that birth rates in the capital Copenhagen, Frederiksberg and Aarhus (Denmark's second-biggest city) have been increasing over the last years (Danmarks Statistik 2018, pp. 8-12). In 2040 the Danish birth rate is predicted to increase from

20,2% to 20,8 % (Danmarks Statistik 2018, p. 10). Especially the biggest urban regions of Copenhagen and Aarhus can expect an increase of children and therefore higher daycare centre participation in future. In 2016 12.759 children (under 3 years old) were registered in nurseries in Copenhagen, in 2017 it was 12.745 and in 2018 there were 14.153 registered children in nurseries in Copenhagen. At the same time, the number of nursery workers dropped from 3922 in 2016 to 3739 in 2018. Thus from 2016 to 2018, 1 there was an increase in children participating in nurseries, while the staffing number decreased.

In 2018, Danmarks statistik calculated that, on average, one adult watches over 6,2 2 children in Danish kindergartens, which is close to what the movement

#hvorerderenvoksen demands. However, another statistic shows that the real staffing number is 10-12 children per adult (Glavind & Pade, 2019). The contrast can be explained by the different methods used in their statistics. Danmark Statistik does for example not take sick days or holidays into account, whereas they include management hours into their calculation. Glavind & Pade (2019) on the other hand, base their

staffing on “children time” (børnetid). Meaning the time staff spends with children. The report also mentions that quality adult time spent with children is becoming less and less. Consequently, adults watch children but they do not have time to engage with children’s unique development needs.

2.1. Early Childhood Education and Care

The European Union introduces its shared vision towards Early childhood education and care (ECEC) in the report “Key Data on Early Childhood Education and Care in Europe” (2014; 2019). ECEC is defined as “Provision for children from birth through to compulsory primary education that falls within a national regulatory framework, i.e. which must comply with a set of rules, minimum standards and/or undergo accreditation procedures“ (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2019, p. 24).

The 2019 report is emphasizing on the overall goal of “universal access, high quality and integration of ECEC services”, which is far from being achieved in all 38

participating European countries (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2019, p. 9). Danmark, however, is often mentioned as a best practice example.

2.2. Early Childhood Education and Care in Denmark

Danish children have the right to a nursery spot from six month on, which is the earliest guaranteed starting age in Europe. The average age to start in nurseries (vuggestue) is 10,7 months and three out of four children are participating in nurseries before the age of two (Danmarks Statistik., 2018b, p. 1). As shown in Table 2, Denmark has, by far, the highest ECEC participation rate of children under three. In total over 79% of all children under six years old participate in daycare institutions in Denmark.

Table 2

Participation rates in daycare centre (children under 3) In Europe

Note. European country codes. From European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice 2019. Copyright 2019 Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency.

When it comes to time spent, Danish children (under 3) spend an average of 34,7 hours a week in nurseries, which is amongst the highest hours in Europe (European

Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2019, p. 71). Early participation in Danish daycare institution is part of Denmark's daycare history. Another aspect, which sheds light to the (in comparison to the rest of Europe) early entry age in institutional life, is the

development of women on the Danish labour market. Since the 60s Danish women have become more equal to men when it comes to participation to the labour market

(Danmark Statistik, 2015). Connecting equality and feminism to early institutional live, becomes interesting. One could furthermore look into how the Danish economic system depends on the workforces of both women and men, and therefore institutions are relevant for the welfare system. In addition, the more time children spend, the more they develop within the framework of institutions. It is here where it becomes important that children spend enough quality time with adults, as it will determine their psychological but also social development.

Looking at the increasing number of children in nurseries and kindergarten, while staffing is decreasing, and understanding that over 79% of all Danish children under six years old are participating in nurseries from age two, the movement

#hvorerderenvoksen can be seen to address an issue affecting society at large. In the ECEC report 2019, Danmark is seen as a best practice example as, but the lived realities of the parents and daycare workers tells a different story.

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Research Stance: Social ConstructionismAs it will become clear from the chosen theories, literature review and methods, I approach my research from a post-modern epistemological standpoint as I am making use of qualitative methods as an effort to understanding how meaning and knowledge is constructed (Andrews, 2012). I approach my research from the social constructionist angle and appreciate both subjective as well as objective realities. I will relate social constructionism in detail to the theory of mediatization and the methodology in the respective chapters. Here I aim to give an introduction in order to explain the foundation of this study.

As the name suggests, social constructionism is interested in studying phenomena from a societal perspective and believes that knowledge is constructed opposed to discovered. An individual's narrative about reality is influenced by how this individual experienced events, it is therefore not mirroring a universal truth but constructs meaning and

consequently reality. Acknowledging the social construction of reality, we can nevertheless gain valuable insights by listening to individual stories (by for example studying phenomena through the eyes of this individual) as their perspective

“correspond to something real in the world” (Andrews, 2012). Reality is defined by the social but experienced and reaffirmed by subjective everyday practices. It is this dynamic that characterizes studies within social constructionism and as such, they mostly are concerned in exploring complex processes, instead of “questions of

causation” (Andrews, 2012). Mediatization is an example for social-constructionism as it claims that we construct our reality through what is transferred via media.

I neither claim that there is one independent, objective reality (realist perspectives) nor do I believe that there are infinite, subjective realities (relativist perspective). I study the representation of a social phenomenon, the #hvorerderenvoksen movement as a

representation of mediatized digital activism. Even though my data (for example the conducted interviews) and my own interpretation of the data will influence the way

digital activism is perceived in this study, it still correlates to a lived reality. This means that I acknowledge that my own perceptions will influence my research and,

consequently, my research does not claim to be objective or reflect a single truth. However, it will add and affirm existing perspectives and as such contributes to the on-going discussion.

3.2. Mediatization

Since the communication and organization of the movement #hvorerderenvoksen are based on Facebook and was also born in the extension of a Facebook post, I find it relevant to untangle the relationship and dependencies of the movement to its medium. As argued in the introduction, social media and activism have entered a close

relationship. It is interesting to look at the interplay between social media and activism to explore how Facebook shapes #hvorerderenvoksen’s communication practices. In addition, language (discourse, text, image, et.c) is part of constructing social reality and Facebook (and its infrastructure) is meditating everyday conversation, or in my case activist communication. Social constructionism is then related to mediatization in terms of meaning is created with media or on (social) media. Couldry & Hepp (2019) base their concept of mediatization on social constructionism, which already becomes clear with the book title “The Mediated Construction of Reality”. Mediatization, as we will come around, is a process-oriented approach to seeking answers and, as understood within social constructionism, interested in exploring the status of different media in the “communicative construction of socio cultural reality” (Couldry & Hepp, 2013, p. 196).

Using Strömbäck’s four phases of mediatization as a starting point for the theoretical discussion, I will show how “social and cultural institutions and modes of interaction are changed as a consequence of the growth of the media’s influence” (Hjarvard, 2008, p. 114). Ever since the framework was conceptualized in 2008, there have been several changes in the digital media system. I am therefore revisiting Strömbäcks theory in the last part of the theory section. In order to make sense of a renewed model, contemporary mediatization mechanism such as digitalisation needs to be taken into consideration. In addition, the interplay between traditional- and social media, the influence of media

logic and network media logic, will be included in the revisit framework. This will then help me to place the case study timely and in reference to mediatization.

3.2.1. What is mediatization?

Mediatization is a meta-concept aiming “to analyse critically the interrelation between changes in media and communication on the one hand, and changes in culture and society on the other” (Couldry & Hepp, 2017, p. 35) and focuses on “the role of

particular media in emergent process of socio cultural change” (Couldry & Hepp, 2013, p. 197). When researching mediatization processes, one is interested in finding a piece to the puzzling questions:

How are everyday life, social relations, and the identity of people, how are organizations and institutions , and how are culture and society as a whole changing in the context of the media development? (Krotz, 2017, p. 45)

Mediatization, therefore, interprets change and transformation and tries to understand the consequences of these transformations and changes. Mediatization describes processes and dynamics within society and in relation to media and does not aim in approaching societal questions with causality. Hepp et al (2015) argue that

mediatization research gives a holistic view on a problem, where media is emphasized but does not stand alone or in the centre of the discussed problem area.

Since the term mediatization is a fairly new conceptualizing within media and communication studies, it is fair to mention that it stirs up the academic world and creates areas of conflict. A common critique is that the concept is being used

imprecisely and is missing a clear definition (Deacon & Stanyer, 2014; Schrott, 2009; Strömbäck, 2008). Mediatization is, as to now, rather recognised as a meta-concept in line with other meta-concepts such as globalization, digitalisation and individualization (Krotz, 2017). It, therefore, encompasses different actors of change and emphasizes the complexity of the social world. As will become clear in the method chapter, studying #hvorerderenvoksen is indeed complex and this study will take media, society as well as political processes into account.

I will now introduce Strömbäck’s (2008) four phases of mediatization, which work as a framework to capture the process-oriented character of mediatization and include media logic as a force.

3.2.2. Four phases of mediatization

Strömbäck (2008) developed the four phases of mediatization as an attempt to show that “mediatization is a multidimensional and inherently process-oriented concept” (p. 228). The four phases of mediatization are rooted in the theory of media logic. I will later talk more about media logic in relation to mediatization in the last part of the theory chapter and only give a short introduction here to show the connection between mediatization and media logic. Media logic is a theory by Altheide and Snow (1979), which had a conceivable impact on media and communication studies. In short, media logic

untangles “the process through which media present and transmit information” (Krotz, 2018, p. 42). Important to media logic is the “formats, content, grammar, and rhythm” of media, which are influencing and shaping relations to other institutions (Strömbäck, 2008, p. 238). Media logic in relation to political (logic), has been widely discussed as media logics have proven to be highly influential over politicians (Schrott, 2008, p. 55 ff) and political campaigns (Seethaler & Melischek, 2014). Strömback does not only refer to politicians but social actors in general. Thus I focus on social actors, whose aim is to influence politics, which in turn includes activists.

In the first phase of mediatization, media is recognized to be the main channel for information and communication. Media logic, however, is said to have a low impact on social actors communicative practices. How reality is pictured in the media influences how people perceive reality and form their opinion (Strömbäck, 2008, p. 236). As such, social actors, take media into consideration when forming opinions and spread

messages, but do not change their own communication practices.

The second phase describes how the media becomes more influential and independent. Media is guided by their own media logic, instead of other institutional rules and norms. Media makes their “own judgments regarding what is thought to be the appropriate

messages from the perspective of their own medium, its format, norms and values, and its audiences” (Strömbäck, 2008, p. 237). Social actors now have to acquire some media logic skills in order to be noteworthy and reportable.

In the third phase of mediatization, media is increasingly becoming independent and takes the form of an autonomous institution. This results in media being “governed more by media logic” and political actors having to adapt to media logic (Strömbäck, 2008, p. 238). He continues:

“(...) media have become so important that their formats, content, grammar, and rhythm—the media logic—have become so pervasive that basically, no social actors requiring interaction with the public or influence on public opinion can ignore the media or afford not to adapt to the media logic.” (Strömbäck, 2008, p. 238).

The distinction between the media world and the real world becomes blurry and “it is the mediated reality that people have access to and react to” (Strömbäck, 2008, p. 238). It is in this phase where the transformation and behaviour aspect of mediatization kicks in since people now start to act according to mediated realities and adopt media logics.

In the fourth phase of mediatization, social actors not only adopt but internalize media logics in order for their message to spread. Media becomes the most dominant and is the main source of information and communication. Media have become as independent as “any institutions can be from a social systems perspective, where total independence is always impossible (Strömbäck, 2008, p. 240). Media content is driven by media logics and “institutional and social actors have come to accept the media logic and its

consequences as an empirical reality and are inescapable” (Strömbäck, 2008, p. 240).

Within the four phases of mediatization, traditional media constantly gains more

institutional power and constitutes its own format, rules and norms. However, the media is not detached from other institutions or governmental rules, but it becomes more and more influential. As argued before, media can not be seen as standing in the centre of

change and transformation, but, instead, has emphasized role within mediatization studies. If a social phenomenon or social actor has been mediatized, it has recognised and maybe even internalized media logic. This depends on in which phase the social actor can be observed.

In the following, I aim to show that Strömback’s framework is valuable for other mediatized phenomena as well - and the mediatization of activism in particular.

Strömbäck already noticed in 2008 that media tends to become dependent on economic factors such as market forces and commercialization (Strömbäck 2008, p. 241). This is, even more, the case in today's media landscape where digital media, and social media, in particular, sinks deep into commercialization processes. Within the scope of my thesis, it is, therefore, crucial to develop Strömbäck’s model further and includes the development of the media landscape as well as their logic to the four phases of mediatization.

3.2.3. Waves of mediatization

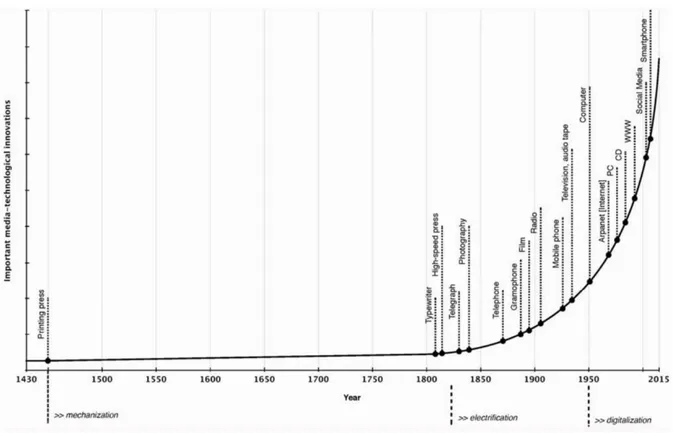

Krotz (2017) argues that mediatization is a meta-process and therefore has to been seen as a broad and long-term concept. He argues further that mediatization exists since society engaged with media (Krotz 2017, p. 107). In connection, Couldry & Hepp (2017) describe four important waves of mediatization: mechanization, electrification, digitalization and datafication (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2. Graph describing waves of mediatization. Adapted from The Mediated Construction of Reality (p. 41), by N. Couldry an A. Hepp, 2017,Chicester: Polity Press.

Processes of mechanization and electrification lay the foundation of the digitalization and research shows how, for example, the integration of television in our everyday life has changed family dynamics and thus mediatized families (Schlör, 2016; Kammer & Kramer, 2016). In correspondence with digital activism, it is most interesting to look at changes in media and technology from when the internet, especially social media and smartphones, were invented. Thus from the mid-2000s when our everyday life got more and more entangled with the internet, smartphones, web searches and content-driven blogs, video-sharing and social media - all of which added to our communicative practices (Couldry & Hepp, 2013, p. 193). I argue that the inventions within the digitalisation wave had a great impact on transforming activist communication and organisation. Therefore the literature review will focus on these changes, which will then be exemplified with #hvorerderenvoksen. Though there is less academic research on how datafication impacts our media usage and transforms society, it is meant to have the biggest impact on the societal change of all four waves of mediatization (Couldry & Hepp 2017, p.130 ff).

3.2.4. Digitalisation, datafication and deep mediatization

Social media are getting more and more intertwined in our everyday life and are deeply rooted in our everyday communication, organisation as well as behaviour. Couldry & Hepp (2017) introduce the term deep mediatization, which explains the complex relationships and the embedded processes between (social) media and society in contemporary times. Deep mediatization emerged after digitalisation, because of the “increased degree of interconnectedness between media that the digitalization of content and the parallel building of an open-ended space of connection (the internet) made possible” (Couldry & Hepp 2017, p. 215).

The interdependencies, which are described within deep mediatization, are even more profound in “the continuous production and exchange of data: the emerging wave of datafication, within the wider wave of digitalization” (Couldry & Hepp, 2017, p.130). What makes digitalisation and datafication processes challenging to study, is that features, such as Facebook pages or sites, are “increasingly entangled in powerful and distant processes, which we cannot unpick or challenge“ (Couldry & Hepp, 2017, p. 131). Krotz (2017) explains further, that in relation to digitalisation, social media and mediatization, Facebook can be seen as a powerful social institution. Facebook has built a monopoly and uses this to “influence its customers to do what is good for the

enterprise” by introducing features, including advertisements and personalizing information (Krotz 2017, p. 107). All of which means that Facebook is collecting human data, as such everything we do (like, share, post, click and so on) online and also offline. The commercial aspect is nothing new to the media system, but it has become more and more integrated in how we make sense of the platform and how our digital footprint is systematically collected in order to please commercial and capitalistic objectives (for example predict our buying behaviour). This is not to make the tools better for us to use, but to “generate data for the toolmaker’s use: that is, to enable us to better be targeted by advertisers and marketers” (Couldry & Hepp, 2017, p. 131). Thus, whenever we use a tool made of data, it is already using us (Couldry & Hepp, 2017, p. 137). Krotz (2017) furthermore warns “we are living in a huge experiment that may hold great importance for democracy and people’s self-realisation” (p. 105). The power

to control structures and rules within datafication processes is lying in the hands of a few, commercial based, institutions, such as Google, Facebook and Amazon (Couldry & Hepp, 2017, p. 206). Even though new social clusters might emerge, their

communication and organization depends on power structures owned by private companies and therefore subordinated private interests (in comparison to the public interest) (Couldry & Hepp, 2017, p. 200).

Even though the aspect of datafication within deep mediatization and, consequently the influence on constructing social reality, has not been captured to its full extent, they should nevertheless be taken into account when studying social phenomena such as contemporary activism. As such, it will serve as food for thought in my analysis of how the movement #hvorerderenvoksen makes use of Facebook features to communicate and organize.

3.2.5. From media logic to network media logic

Within the waves of mediatization, the norms and values that guide media have also changed. Klinger and Svensson (2018) explain that “ideals differ on social media”, which is why network media logic is used when analysing social media (p. 4657). This case study shows, however, that digital media and traditional media are shaping and influencing each other. Therefore they have to be studied in relation when studying contemporary activism. In the following, I will explain the importance of both media and network logic for mediatization processes to this study. Revisiting the four phases of mediatization, network media logic will be at work together with media logic.

The theory of media logic has its origin in Altheide and Snow’s (1979) often cited book Media logic. Media then referred to what is now called traditional or mass media, mostly focusing on newspapers, television and radio. Media was allocated a certain logic, meaning “specific norms, rules, and processes that drive how content is produced, information distributed, and various media are used” (Klinger & Svensson, 2018, p. 4656). Media is driven by “capturing people’s attention” and as such, media agents require skills within news values and storytelling (Strömbäck, 2008, p. 233). Looking back at the four phases of mediatization, it is not only the agent within media (for

example journalists) that acquire media logic expertise, but also increasingly, external actors (for example politicians and other social actors) that transform their skill repertoire to satisfy media logic.

Obviously, the media landscape has changed since the origin of media logic in 1979. Going from analogue to digital media, the internet has influenced how media is produced, distributed and used (Klinger & Svensson, 2014). Media is not passively consumed, but interactively shaped and spread by its audience. This is not to say that digital media necessarily fosters democratic structures, but audience input and usage play a bigger role in the new media landscape. Social media is often referred to like social networks, as it is a network of people or the “networked self” that is characteristic for platforms such as Facebook or Twitter (Papacharissi, 2011). These sites, among other things, “enable individuals to construct a member profile, connect to known and potential friends, and view other members’ connections” (Papacharissi, 2011, p. 304). The networking attribution is what Klinger & Svensson (2014) define as the main characteristic of the new media and suggest to develop media logic to network media logic as social media sites differ from mass media in terms of content production, information distribution and media usage (p. 1251). Network media logic “follow values of produsage, connectivity, virality, and reflexive sharing of information among peers and like-minded individuals“ (Klinger & Svensson, 2018, p. 4657). Social agents now need to be familiar with social media skills performing “responsiveness and connectedness” within content production and distribution on social media (Klinger & Svensson 2014, p 112).

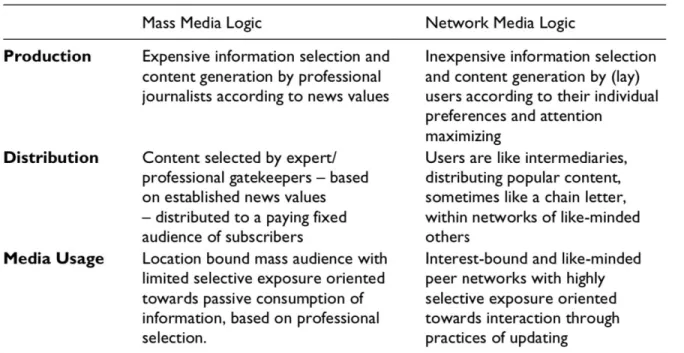

Inspired by Klinger and Svensson, D’heer (2018) explains that a “users’ collective endeavour (of likes, shares, or retweets)” is key to which content is distributed and becomes popular (p. 176). Storytelling is still a desirable skill on social media, but it takes “positive, personalized and emotional” forms (Klinger & Svensson, 2018, p.1253; D’heer, 2018, p. 176). This emotional and personalized storytelling can be observed in #hvorerderenvoksen’s Facebook posts and, especially, in the Facebook group Parents diary (see method chapter for a detailed explanation). Figure 3 presents the main difference between mass media logic and network media logic in terms of production, distribution and media usage.

Mass Media Logic versus Network Media Logic

Figure 2: Differences between mass media logic and network media logic in respect to production, distribution and media usage, adapted from The emergence of network media logic in political

communication: A theoretical approach, by U. Klinger and J. Svensson, 2014, New Media & Society, p. 1246.

While “network gatekeepers”, like Facebook, might challenge “traditional gatekeepers” mass media logic and network media logic are not mutually exclusive, but overlap in practice and share features such as desiring virality (D’heer, 2018, p. 175). A

mechanism that will be explained in the analysis in detail and in relation to this study. Couldry & Hepp (2017) refer to this as the media manifold, our media usage is complex as we can choose and pick from different media and constantly switch from one to the other - or use them simultaneously and in connection. Bernards (2018) explains further that the hybridization of the media landscape as well as mediatization results “in the emergence of shared media logics, both of field structures and practices” (p. 2254). He furthermore explains the hybrid field of media and network media logic by elaborating on the shift of journalistic reporting style: “objectivity and independence, emotion and subjectivity inevitably seep into the reporting process” (Barnard, 2018, p. 2256). In connection, Klinger and Svensson (2018) explain that both logics “overlap and intertwine” (p. 1252). This happens when, for example, Facebook groups share and

update their group with content from traditional media and then again social media content can experience a boost through mass media coverage (ibid).

Concluding, social media and traditional media are intertwined and influence each other. Even though both have their own logic(s), they are often used in reliance on each other. Therefore both logic(s) are and a media hybridity are at play when studying contemporary social phenomena. However, in relation to #hvorerderenvoksen, the media hybridity needs to be further elaborated on and will be exemplified in the analysis.

3.3. Four phases of mediatization revisited

In relation to media hybridity, meaning that both media logic and networked media logic influence and shape social agents and therefore are deeply intertwined, one can not simply replace media logic with network media logic in Strömbäck’s mediatization framework. However, at times of deep mediatization, network media logic is becoming more influential, which is why I revisit and update the four phases of mediatization.

In the first phase of mediatization, traditional media and social media are both

recognized as important information and communication channels. Mass media logic and network media logic are both at play. Though, network media logic is said to have a low impact on communicative practices. How reality is pictured in media and social media, has an influence on how people perceive reality and form their opinion. As such, social agents, take mass media and social media into consideration when forming opinions and spreading messages, but also stay true to media logic, recognizing news values and neutral storytelling.

The second phase describes how social media becomes more influential. Social media is guided by their own network media logic, and mass media recognises this logic. Social agents now acquire skills towards both mass media logic and network media logic in order to be noteworthy and reportable.

In the third phase of mediatization, social media is increasingly becoming independent and takes on an institutional form (see also Krotz, 2017). This results in social media becoming even so influential as mass media, and at times more influential. However, social and traditional media are still intertwined and shaping each other. Social agents and journalists are adapting to network media logic, which is characterised by

responsiveness, connectedness and emotional storytelling. In shaping reality, the world presented in social media sinks into people's understanding of the social world. It is the “mediated construction of reality” people react to (Couldry & Hepp, 2017). In addition, traditional media adapts to what is trending content on social media. Therefore social media reality becomes embedded in the real world.

In the fourth phase of mediatization, social actors and journalists not only adopt but internalize network media logic in order for their message to be spread. Social media has become the most dominant source of information and communication. Traditional media and mass media logic is secondary, if not trivial. Social media has become as independent as they can become from mass media and other institutions. This phase, however, is hard to picture in reality. As I will argue further, contemporary activism is defined by a media hybridity, where traditional and social media influence each other. Approaching the fourth phase from a netnography perspective, online and offline worlds are not existing parallel, but are intertwined (Kozinets, Dolbec & Earley, 2014). As such I have not observed a phenomenon where only network media logic is at play, which makes this phase highly theoretical. Also, it is an argument against technological determinism.

My revisited version of the four phases of mediatization focuses on the interplay between old and new logics within times of deep mediatization. As I will argue in the analysis, the #hvorerderenvoksen movement is situated in the third phase of

4. Literature Review

In order to understand how contemporary activism transformed in the digital age, I will now review recent literature on this topic. The literature review is structured in

accordance with the research questions and will, therefore, help to argue for relevance the research questions in combination with my own empirical findings.

4.1. Contemporary activism: what has changed?

Svensson et al (2014) define activist participation as “political participation from outside representative democratic institutions, but with an outspoken aim to influence public decision-makers” (p.850). This outspoken aim is formulated by a clear demand. “A demand may be formed into a more long-term social movement, or a single-issue campaign that disperses once the demand has been met (or considered lost)“ (Svensson, 2014b, p. 3). The overall goal of political participation is to influence the whole society (Neumayer and Svensson, 2016, p 133). In relation to digitalisation, Liu & Gao (2016) explain that activism has undergone a deep technological and organizational

transformation with personal networks and networked communication technologies at the core of digital activist participation. Online community building is one of the core elements of contemporary activism (Kaun and Uldam, 2018, p. 2104; Breindl, 2012, p. 33).

Early digital activism studies have focused on how information exchange online, and user-generated content sharing in particular, “fosters socio-political discussion and participation” (Xiong et al, 2019, p. 12). It is argued that the internet can lower barriers of political participation. Participation itself has become more flexible, which results in a mix of personal protest activities, like joining a Facebook group or signing an online petition, and internet-based collective action (Breindl, 2012, p. 55). Breindl (2012) furthermore explains that the internet has been assigned benefits like horizontal

communication and free speech (p. 33), which in turn could enhance democracy efforts. However, Breindl (2012) also evaluates, that the degree to which the internet can contribute to political and social debates, depends on how individuals and groups use it.

Consequently, the age of digitalisation was hoped to be the golden age for democracy with grassroots and bottom up forces giving back power to the people (Zuboff, 2019b).

4.2. What role does social media play for activism?

The following part will start by making general statements about social media in relation to activism, but then focus on Facebook in particular, since it is the most important social medium for #hvorerderenvoksen.

Going from collective to connective action, Svensson (2014a), as well as Segerberg and Bennett (2012), underline the network character of interactive digital spaces.

Personalized content sharing, co-production and self-organizing on social media is one of the key elements of participation in contemporary activism (Bennett and Segerberg, 2012, p. 752). “Connective action is self-motivated (...) sharing of already internalized or personalized ideas, plans, images, and resources with networks of others“ (Bennet and Segerberg, 2012, p. 753). Breindl (2012) argues that networked individuals are weakly tied together, but sharing a mutual demand, goal and values (p. 28). On social media, political participants are “active creators of meanings in social movements” (Xiong et al, 2019, p. 20). Since networks can organise themselves on social media, it is no longer necessary to set up an official organisation or to make use of traditional organisational methods (Breindl, 2012, p. 25). Kaun and Uldam (2017) summarize Facebook's role as being “vital in terms of synchronising action to coordinate bodies and objects in time and space“ (p. 2198). This is clearly observable in the case of #hvorerderenvoksen, as Facebook's infrastructure was used as a tool to communicate and mobilize parents all over the country.

An important concept, which is connected to the use of social media, is virality. Virality is a “social information flow process where many people simultaneously forward a specific information item, over a short period of time, within their social networks, and where the message spreads beyond their own (social networks) to different, often distant networks, resulting in a sharp acceleration in the number of people who are exposed to the message” (Nahon and Hemsley, in Liu and Gao, 2016, p. 852). An important tool for virality are hashtags. Hashtag activism then is the „act of fighting for or supporting a

cause with the use of hashtags as the primary channel to raise awareness of an issue and encourage debate via social media“ (Tombleson & Wold, as cited in Xiong et al, 2019, p. 12). The aspect of virality is described by Neumayer and Struthers (2019) as

acceleration, which can enhance activist mobilization, but it risks that the movement is only temporarily successful, thus not sustaining its influence (p.89). Temporary, instant actions (linking, sharing or following) thus can accelerate a message, but they can also be downplayed to be slacktivism or armchair activism with little lasting effect (Boykoff, in Ramirez and Metcalfe, 2017, p. 58)

Neumayer and Rossi (2016) collected research on activism in relation to media from 2000 until 2015. Since 2010, academics have addressed how social media (Twitter in particular) has shaped activism. Studies pre 2016 have focused on the positive effects social media has on activism. Twitter has made it easier to extract data, thus it is not surprising that this platform is widely used for research purposes as well.

“Social media and Twitter, in particular, have been referred to from a deterministic perspective as enablers, facilitators, vehicles of democracy, forces for social change, and catalysts as well as (in reaction to the deterministic hype) from a functionalist perspective as mere tools or channels activist can use” (Neumayer and Rossi, 2016, p. 7). Recent studies, however, are rather critical towards activism using digital platforms, and social media in particular. As we will come around in the literature review

datafication and commercialisation, among others, have changed the way academia research the societal meaning of social media.

4.3. What are the consequences of using social media for activism?

Activists, who would like to keep their organizational and communicational structure as horizontal as possible are challenged when using, for example, Facebook as a

communication channel. Facebook’s pages and sites are built with a commercial purpose (Kaun & Uldam, 2017). Thus they are built for brands and pushing posts made by administrators (the owner of the brand) as they want to assure that brands can reach their audience. By algorithmic default, Facebook favours administrators content (posts) over posts made by members (Kaun & Uldam, 2017, p. 2197) and as such the

communication is hierarchical. Administrators can also decide whether to make a post from a follower public. Thus, not all posts made by followers are visible.

Thus Facebook algorithms affect communication flows on Facebook pages as they are designed for commercial purposes, meaning for brands to push their marketing content. This means that even if activist groups aim to have horizontal communication with their members/followers, using Facebook sites or groups will not allow them to do so. In connection with the role of social media in activism, the concepts of affordances have been widely discussed. Affordances in this respect are defined as the “ability of a certain technology that emerges from the interaction between material qualities of the technology, and individuals or organizations’ perception of its utility” (Liu & Gao, 2016, p. 853). When seen as a technology, social media has subjective affordances which are shaped by a person's perception and usage of social media (Costa, 2018). In relation, Tsatsou (2018) explained that in the case of the Sunflower Movement, Facebook's infrastructure was mainly used for information sharing and spreading. The affordance of spreading, or updating, is also observed in the Svenssons (2014a) study about the Swedish Bathhouse case. In connection to deep datafication processes, Mahnke (2019) suggest to use the term social media materiality, as it “stands for algorithmic materiality entangled with user behaviour” (p. 132). To avoid

techno-determinism, it is important to mention that Mahnke does not see algorithms as detached from human behaviour or as simple artefact, instead, she introduces the term “communicative materiality” when talking about algorithm-user relations (p. 133). In connection, Neumayer and Struthers (2019) identify Facebook’s algorithms as part of their “techno-commercial materiality”, which together with an activist struggle to work around this materiality (in order to be visible on Facebook), forms the essence of activist representation on social media (p. 87). Kaun and Uldam (2017) sum up:

„Hierarchies are not created by social media per se, but by a combination of their technological affordances, the ways in which they are used, the discourses they propagate and the power relations in which they are embedded“ (p. 2203).

The skeleton of Facebook pages contradicts activist values such as “horizontalism, inclusivity, and leaderlessness” and softens collective identity (Coretti & Pica, 2019, p.

82). In addition, Facebook’s own rules (terms and conditions) play a central role in what activists are allowed to communicate. They shape activists communication by

moderating and sometimes even prohibiting content (Kaun & Uldam, 2017, pp. 2191-2192). In addition administrators of a Facebook group or site, have to constantly create content in order to appear in their followers’ news feed (Kaun & Uldam, 2017, p. 2198). Updating is thus a key action in order to gain influence on Facebook.

4.4. How does social media change activism and activists?

Using Facebook as the main communication tool „requires activist to adjust their communication accordingly“ (Kaun & Uldam, 2017, p. 2203). Activists skills decide whether one can keep others being interested in the cause, but also which position a person has inside the movement. Activism on social media is therefore similar to older forms of activism because it “requires technical skills and issue-specific expertise to be efficient (Breindl, 2012, p. 17). In the digital age, connectedness, recognition and networks play a significant role (Svensson, 2014a; Kaun & Uldam, 2017). Breindl (2012) argues further that central figures, or leaders, are usually the ones equipped with digital skills and an understanding of social media infrastructure (p. 16). Being

(pro)active in terms of updating and engaging others about the movement and movement related content, is one of the networking skills (Breindl 2012; Svensson, 2014b).

„Networking power is time bound to the participation of the user. Hence, constant participation in the form of continuous practices of updating is mandatory for negotiating the recognition that is needed to occupy of core-positions” (Svensson, 2014b, p.23).

Updating skills are not only relevant for internal communication and positioning but can also influence how the activist group is seen from the outside. Journalists often find content over social media and contact the person, who seems to be in charge of a group. Often they are marked as administrators. Thus engaged activist can potentially influence gatekeeping (news coverage) and the perspective from which an issue is talked about in mass media (Barnard, 2018, p. 2255). Thus, they can influence what and how journalists

report (Bennett & Segerberg, 2012, p. 742). In turn, the activist also leans on journalistic reporting styles, thus mixing “objective (and occasionally verified) information with opinion and emotion” (Barnard, 2018, p. 2264). In the case of the Student Federation of the University of Chile, Facebook was used to spread information from traditional news channels and as such highlights the before mentioned media hybridity (Cabalin, 2011).

Summing up, recent studies on digital activism have pointed towards both advantages of using social media in terms of communication and mobilization, while elaborating on that social media is not deterministic. This highlights the interplay between traditional as well as social media. The media hybridity become important when studying

5. Method and Methodology

5.1. Case Study DesignHaving explained my theoretical lens and reviewed literature about digital activism, this part will explain how this study aims to connect theory with empirical findings. I collect empirical data with the case study method. For this, I rely mostly upon, but not entirely, on Robert K. Yin’s book Case Study Research: Design and Method (2012; 2014). Robert K. Yin has been focusing on case studies since 1984 and has updated the method according to his observation and other critics over time. Case studies aim “to produce an invaluable and deep understanding—that is, an insightful appreciation of the

“case(s)”—hopefully resulting in new learning about real-world behaviour and its meaning” (Yin 2012, p. 4). The case study method provides rich, descriptive and insightful explanations, which is needed in order to understand the dynamics between the movement #hvorerderenvoksen and social media.

Yin (2014) defines a case study as “an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon (the case) in depth and within its real-world context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context may not be clearly evident“ (p. 16). A case is defined by Yin (2012) as a bounded entity, for example, a social phenomenon. I study #hvorerderenvoksen (the case) as a digital activist

phenomenon, which is proclaimed to be historical in its size and impact (Blønd, 2019). I aim to answer how and why the movement emerged and how it is shaped in relation to its primary communication channel (Facebook). Studying the context and complexity of the case is elemental to understanding the case (Yin 2012, p. 4). Collins (2010) agrees that the case study method is helpful when “measuring what is present and how it got there. In this sense, it is historical. It can enable the researcher to explore, unravel and understand problems, issues and relationships“ (p. 126). In connection to mediatization, a case study will help to explain the complex interrelations between social, political and media processes.

Figure 3: Figure showing single and multiple-case study designs. Adapted from Applications of case

study research (p 8), by R.K. Yin, 2012, Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

Using case study research, one can do a single-case study or a multiple-case study (see Figure 4). I have chosen to work with a single case, as extensive research was needed to understand the context and social media's role in the movement.

In order to use the case study as a methodological framework, sufficient access to data should be available. Planning a case study is also part of the method. It requires a substantial knowledge requisition (theory and literature review) to do a case study as one needs to know what to look for before collecting data (Yin, 2014, p70). Part of the preparation for this case study was to find a solid theoretical background and literature list, which would help to display the importance of the case for media and

communication studies. Theory and literature review are part of the case study design as it helps to understand “why acts, events, structures, and thoughts occur” (Yin 2012, p. 9). I have elaborate on this part in detail in the theoretical section and combine findings from previous studies with #hvorerderenvoksen in the analysis.

In addition, single case studies derive from theory, meaning they test or add to theory. However, they can also shed some new light on a theory by adding a new perspective or

extending circumstances, which has been done by revisiting Strömbäck’s four phases of mediatization.

It is worth to stop here and shed some reflection on case studies in terms of social constructionism. It is typical for social constructionist to work from data to theory in order not to influence or try to make data fit to theory. Working with single case studies in reference to Yin (2012) does not follow common social constructionist ways of studying the social, as it is not inductive. However, neither did I work strictly deductive. In reality, I went from theory to data back to theory. I was familiar with mediatization as a concept (as it was part of course literature) then made observations and conducted interviews, and in the end, turned back to mediatization and adjusted Strömbäcks four phases of mediatization in accordance to the empirical findings.

The concept of mediatization has been discussed in my previous studies and when looking for an interesting research case for the master thesis, I observed that the movement #hvorerderenvoksen could be studied in relation to mediatization.

5.2. Data collection for #hvorerderenvoksen

According to Yin (2014) a case study can construct validity, external validity, internal validity and reliability by working with four principles of data collection:

1. Using multiple sources

2. Creating a case study database

3. Maintaining a chain of evidence (timeline)

4. Exercising care in using social media communications as data

In line with Yin’s four principles (2014, p. 105), I have systematically collected data from multiple sources and will analyse this data consistently to be able to make analytical generalizations (Yin, 2012 p. 6). I have in total used four different methods: direct observations, archival records, open-ended interviews and documents (see appendix 1 for a detailed overview). The case study database is presented below.

Type Source Count Interviews Spokesperson #hvorerderenvoksen 1 BUPL, executive committee member 1

Direct observations Facebook (groups and page)

3

Archival records Newspaper articles 7

Blog posts 3

Documents E-mails 2

Facebook posts 9

In order to understand the complexity of #hvorerderenvoksen’s background and to shed light on the connection between the case and traditional as well as social media, I have chosen to narrate the story of #hvorerderenvoksen at the beginning of the analysis chapter. The story of #hvorerderenvoksen is a narrative based on the data collection for this study. It, therefore, refers to how I, with the help of the collected data, situate the case. The story of #hvorerderenvoksen is consequently a possible answer to the first research question.

5.2.1. Interviews

The interviews turned out to be the core method in this thesis. This was not planned, but it turned out the interviews provided this research with rich and insightful information. As I wanted to stay open-minded towards data and findings (social constructionist ambition), I did not choose a core method beforehand.

I have conducted two interviews and used both Yin (2012; 2014) and Kvale (1996) for preparation and analysis. Within case studies, interviews can be described as “a guided conversation” (Yin, 2014, p. 110). In line with social constructionism, the guided conversation can be described as a “practice during which our shared versions of knowledge are constructed” (Nielsen, 2012, p. 216). The knowledge produced under a

conversation is not merely an objective narrative of events, but rather a “product of (...) social processes and interactions in which people are constantly engaged with each other (ibid). Or as Kvale (1996) puts it, an inter-view is an exchange of views between people talking about the same topic. In order for me to be familiar with

#hvorerderenvoksen and ask intriguing questions, I prepared by reading articles,

watching documentaries, saw television debates and observed the movement over a time span of three months.

The interview guide was designed with open-ending questions aiming to stimulate a discussion. I had topics in mind and only wrote questions down, which should help me to stay focused. My interview was designed to explore #hvorerderenvoksen, as such the interview was “open and has little structure. The interviewer, in this case, introduces an issue, an area to be charted, or a problem complex to be uncovered“ (Kvale, 1996, p. 97). At the same time, it is helpful to ask „How“ question in order to get to the bottom of the case and also to appear „friendly and non-threatening“ to your interviewee (Yin, 2014, p. 110). In this sense, I showed my curiosity and tried to be a conversation partner and not a researcher with a hidden agenda.

I conducted a 1.5 hours unstructured interview with M. Blønd, the spokesperson of #hvorerderenvoksen. M. Blønd is a researcher and lab manager at the ETHOS lab at the IT University in Copenhagen . In order to ask for an interview, I both emailed and 3 called M.Blønd. The interview then took place at her office at the IT University in Copenhagen. The factual preparation for the interview (see direct observation, archival records and documents) also helped me to feel comfortable as I had a pre-understanding of the topic and the movement. This interview was an example of an inter-view (see Kvale, 1996) as we rather had a conversational format and I only ask a few initial questions and then probed her get deeper into the subject. As such, it was an unstructured, in-depth interview (Collins, 2010).

It is worth mentioning that M. Blønd is a key figure in the movement, as she is the spokesperson and often referred to or invited to speak on traditional media. Yin (2012) explains that insights are more valuable when interviewees are key persons because by

definition only one or a few persons will fill such roles, their interviews also have been called elite interviews (Yin, 2012, p. 12).

Furthermore, I conducted a one-hour semi-structured interview with M. Skovhus Larsen from the labour union Børne- og Ungdoms Pædagogernes Landsforbund BUPL (Danish National Federation of Early Childhood Teachers and Youth Educators). This interview was semi-structured as I asked most of the questions from the interview guide, but let M. Skovhus Larsen answer at length. This interview took place at BUPLs office in Copenhagen. M. Skovhus Larsen explained the relation between #hvorerderenvoksen and the worker union BUPL. In addition, she talked about the context of

#hvorerderenvoksen and the events happening before the movement arose on Facebook. This interview is mostly made to use in answering the first research question, which explains the complexity of the movement. Reflecting on the interview, M.Skovhus Larsen was speaking on behalf of the labour union and the communication was, therefore, more factual and I had to ask more questions in order to gain knowledge for this research.

I have recorded both interviews. After listening to the interview, I divided it into four categories: 1a) The background of the movement, 1b) the movement in relation to media, 2) the movement in relation to Facebook, and 3) the gain and constraints of making use of Facebook as the main communication channel. These categories also guided my research and as such was made explicit in the research questions.

Concluding, both interviews were insightful, whereas the interview with M. Blønd can be used for all four categories, M. Skovhus Larsen’s interview was mainly used in relation to the first category.

5.2.2. Unstructured Observation

In the time span of four-month, I have been observing all three external Facebook communication channels of #hvorerderenvoksen. My observations were unstructured and disguised in the sense that I did not have research aim, but rather research

intentions. This flexibility enabled me to find interesting components of studying the movement (Collins, 2019). In addition, none of the members/followers knew that the

Facebook groups and site was under observation. Thus, I assume, people behaved naturally (Collins, 2019). I have documented these observations by collecting Facebook posts, which show what and how the movement in communicating. These Facebook posts are collected in the detailed data collection (see appendix 1). The story of #hvorerderenvoksen then draws upon observation and Facebook posts.

For example, the observations helped to conclude that the movement is using three Facebook features for three different communication purposes. I have summarized the three channels as follows: The informativ Facebook site, the debating Facebook group and the storytelling Facebook group (see appendix 2).

5.2.3. Archival records

I am drawing upon eleven newspaper articles and blog posts in order to understand the context and media coverage of the movement. These articles and blog posts were used to prepare for the interview as I wanted to have a conversation, rather than asking questions where I can find factual answers elsewhere. I, therefore, tried to gain as much knowledge about the movement as possible. As such archival records and interviews are somewhat being used in combination as the interview is built on knowledge gained from archival records produced by traditional news outlets.

Newspaper articles helped me to find out that Marie Blønd is seen as the head of communication (spokesperson) of the movement, even before #hvorerderenvoksen announced her role on the Facebook page. Traditional media interviewed her frequently and she appeared as the face of the movement. I also used newspaper articles as well as television clips to make sense of the movement's name. In some places it is called ‚Hvor er der en voksen?‘ and in other places, it is called #hvorerderenvoksen, also spelt #HvorErDerEnVoksen. Another example is Marie Blønd: When looking her up on Facebook, she is spelt Marie Blond, but when encountering her name in the newspaper, I found out that her name is Marie Blønd. All in all, I retrieved rather factual

information from the reviewing archival records, and do not lean on their representation of #hvorerderenvoksen.

However, Yin warned to be aware of the accuracy of these documents. Newspaper articles were written to fit newspaper agenda and news logic and might therefore not be unbiased (Yin 2014, p.106).

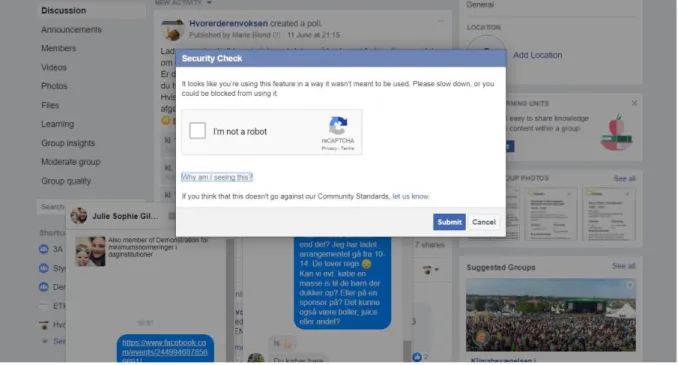

5.2.4. Documents

I have chosen to pin Facebook posts under documents. Documents are stable (can be reviewed repeatedly) and unobtrusive data, meaning they are not a direct outcome of the case study and do not serve a direct goal (Yin 2014, p.106). In order for Facebook posts to be reviewed repeatedly, I made a screenshot of them and stored them in a file. These Facebook posts were selected through my observation of the Facebook group and the Facebook site. The posts helped me to understand why the movement needed three different Facebook features in order to communicate with their community (see direct observation for a full overview). In addition to this, the post was also used to understand the language used to communicate with their members. In the post, the movement sounds friendly and including. The movement does not use harsh language or is defensive. Their friendly attitude is also mentioned is also a topic both of my interviewees brought up. In addition, I have received two emails with background information. One email was a follow up from one of the interviewers with a concrete example of a drawback she experienced when trying to mobilize people over Facebook. The other email included a figure showing how often the demand of the movement was mentioned in traditional media from the start of the movement and until the end of the Danish election. This table is put into perspective in the story of #hvorerderenvoksen and aims to exemplify how media hybridity is visible when studying the movement closely.

5.3. Ethical considerations and limitations

As I have gathered data from multiple sources and multiple methods, there are several ethical considerations that guided me through empirical work and the analysis. For once, I have conducted two interviews with representatives of a) the movement and b) an organisation working close to the movement. Both interviews present subjective realities and understandings of their experiences with the case study. It is their interpretation of events that shine through the interviews. However, I am also a