This is the way...or is it?

A Qualitative Study of SMEs’ Crisis

Management in the Context of COVID-19

Master thesis within: Business Administration Number of Credits: 30

Programme of study: Strategic Entrepreneurship Authors: Balázs M. Hepp & Luis F. Humpert Tutor: Michal Zawadzki

Acknowledgements

First of all and foremost, we would like to express our genuine gratitude for our supervisor Michal Zawadzki, who took on the responsibility of assisting and guiding us throughout the whole research. His feedback always helped us to overcome challenges arising regarding our thesis work and to be able to keep advancing with the study. His commitment was indispensable in order to improve and finish our work.

Furthermore, we want to present our gratitude towards our peers, whom we were able to engage in constructive discussion regarding our paper, through the seminars, providing invaluable insights and ideas.

We would like to thank all the decision makers who were willing to participate in this study. Without their time dedicated to our research and their honest engagement, this study would not have been possible.

We also would like to express our appreciation for Karin Hellerstedt, who as a Course Examiner for our Master Thesis oversaw and ensured prompt flow of information throughout the semester, providing help with all structural or administrative issues. We must also mention that we are grateful for all our professors, teachers, and guest lecturers, who fostered motivation and helped us learn and grow both professionally and personally, throughout our studies at Jönköping International Business School.

Lastly, we want to thank our families and friends since, without their constant support and dedication we would not have been able to achieve this research, and for that we would like to express our eternal gratitude towards them.

Sincerely,

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: This is the way...or is it? A qualitative study of SMEs’ crisis management in the context of COVID-19

Authors: Balázs M. Hepp & Luis F. Humpert

Tutor: Michal Zawadzki

Date: 2021-05-24

Key terms:

SMEs, Crisis Management, Hungary, Germany, COVID-19, Contingency Theory, Crisis

Abstract:

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way we live and conduct business around the world. SMEs around the globe are facing dire times, as they lack the power of size and reserves in comparison to large multinational firms. This crisis must be navigated well for companies to survive it. As the pandemic escalated, it turned into a full-scale economic crisis leading to a surge in uncertainty. Contingency theory is a management theory centralized around uncertainty and adaptability, thus making it an interesting approach in the context of a crisis. In this paper, the way companies deal with the situation is analysed through the theoretical lens of contingency theory. This research looks at crisis management actions taken by SMEs in Hungary and Germany. 15 semi structured interviews with decision makers in different SMEs were conducted. Based on their interpretation and personal experiences, the nature of measures and the process of crisis management on an organizational level was explored. A conceptual model is proposed, discussing the relation of different aspects of crisis management. The crisis highlighted the complex demand of being agile and being able to integrate contingency plans on the level of organization. The measures taken by the researched population show that, in line with the main paradigm of contingency theory, there is no single best universal way to avert the negative impact of the crisis. SMEs' reactions were highly dependent on their individual and specific factors. It can, however, be concluded that a systemic crisis like the current COVID-19 pandemic generally increases uncertainty and volatility, further emphasizing the need for fit of contingencies for companies.

“It cannot but happen that those individuals [organizations] whose

functions are most out of equilibrium with the modified aggregate of

external forces, will be those to die; and that those will survive whose

functions happen to be most nearly in equilibrium with the modified

aggregate of external forces”

Contents

1. Introduction ... 1 1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Problem Discussion ... 2 1.3 Purpose ... 4 2. Literature review ... 62.1 The COVID-19 epidemic ... 7

2.1.1 Economic implications ... 8

2.1.2 Exposure of SMEs ... 8

2.1.3 Government restrictions & support affecting SMEs ... 10

2.2 Contingency theory ... 12

2.3 Crisis and issue management ... 15

2.4 Crisis management through the lens of contingency theory ... 18

3. Methodology ... 21 3.1 Research philosophy ... 21 3.2 Research Approach ... 22 3.3 Research strategy ... 23 3.4 Methods... 24 3.4.1 Selection ... 24 3.4.2 Interview Design ... 26 3.5 Data collection ... 29 3.6 Data analysis ... 30 3.6.1 Content analysis ... 30 3.6.2 Report on analysis ... 32 3.6.3 Data structure ... 35 3.7 Research Ethics ... 39 3.8 Research quality ... 40 4. Findings ... 42 4.1 Perception of threat ... 42

4.2 Diversification as a reaction ... 43

4.3 The need for flexibility ... 44

4.4 Expect the unexpected ... 45

4.5 Value of flow of information ... 46

4.6 Self-reflection ... 47

5. Propositions ... 49

5.1 The Perception of threat as a trigger for reaction ... 49

5.2 The nature of diversification as a coping reaction ... 49

5.3 Improvise, adapt, overcome ... 50

5.4 Experience as a foundation for contingency plans ... 51

5.5 Value of information as a mediator ... 51

5.6 Retrospective learning ... 52

5.7 Conceptual Model ... 53

6. Discussion... 55

6.1 Discussion on emerged propositions and findings ... 55

6.2 Discussion on the research gap ... 59

7. Conclusion ... 61

8. Implications ... 63

8.1 Theoretical Implications ... 63

8.2 Implications for practice ... 64

8.3 Limitations ... 65

8.4 Suggestions for future research ... 67

Reference list ... 69

Tables

Table 1 - Factors determining whether an enterprise is a SME...4

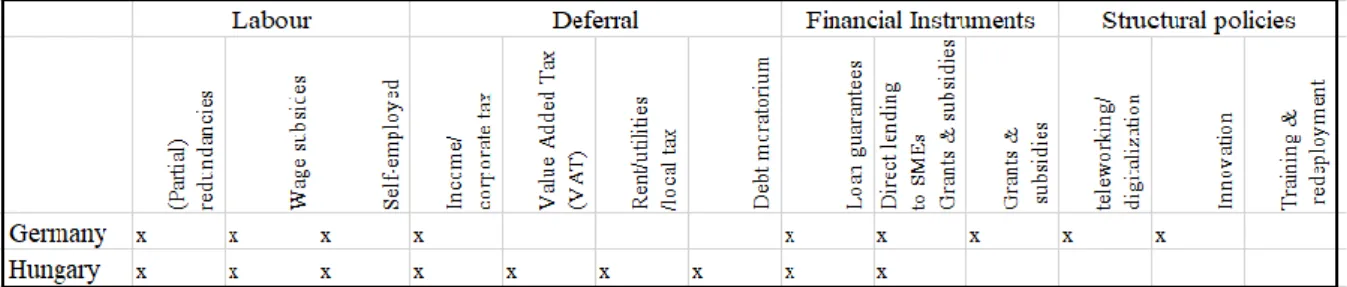

Table 2 - Measures to support businesses in Germany & Hungary... 11

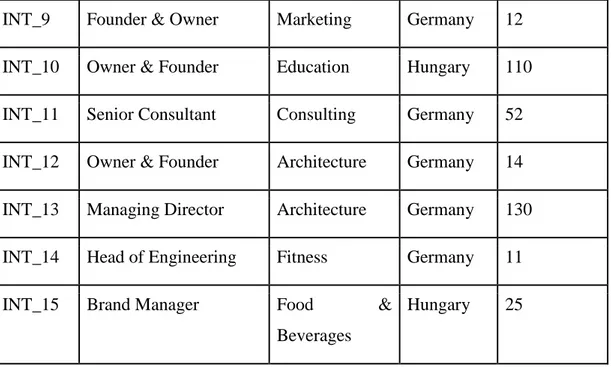

Table 3 - Information of final sample... 25

Table 4 - Information on individual interviews... 29

Figures

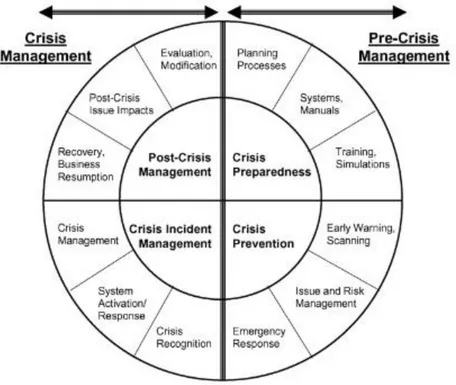

Figure 1 - COVID-19 cases reported... 7Figure 2 - Issue and crisis management relational model... 16

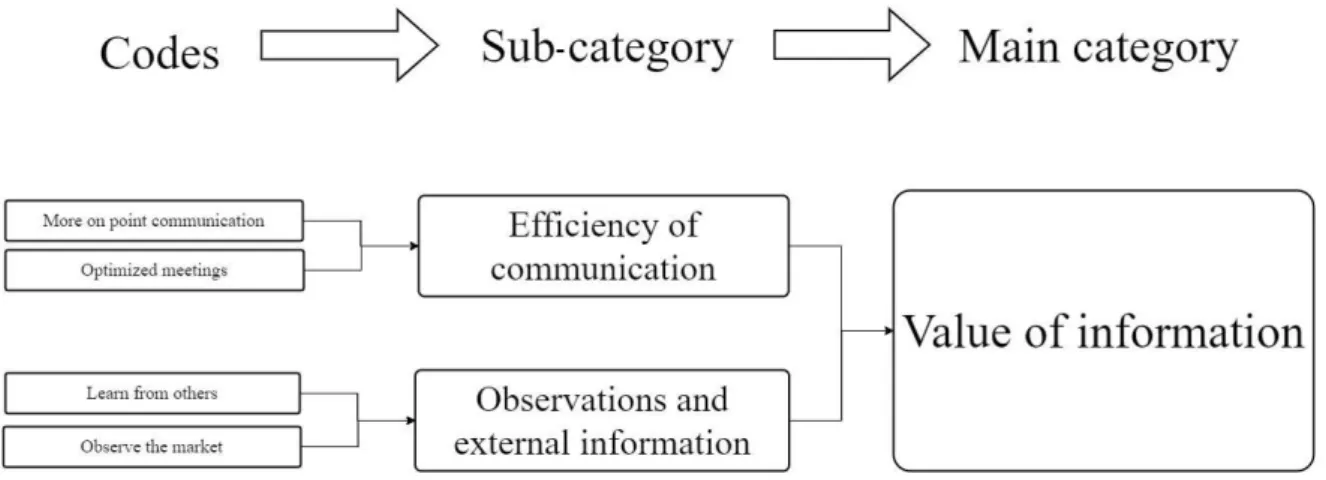

Figure 3 - Logical sequence of Existential threat main category... 35

Figure 4 - Logical sequence of Diversification main category... 36

Figure 5 - Logical sequence of Need for flexibility main category... 37

Figure 6 - Logical sequence of Expect the unexpected main category... 38

Figure 7 - Logical sequence of Value of information main category... 38

Figure 8 - Logical sequence of Self-reflection main category... 39

Figure 9 - Conceptual model... 54

Appendices

Appendix 1 - Start-up support schemes in France, Germany, and the UK... 79Appendix 2 - Translation examples...80

Appendix 3 - Detailed Interview topic guide... 81

Appendix 4 - Examples representing coding process... 82

Appendix 5 - Detailed results of coding………... 83

1

1. Introduction

The introductory part covers a brief summary of the development of the COVID-19 pandemic, it describes how it has engulfed the world and led to a widespread systemic crisis. It goes on to describe how this crisis is creating widespread economic uncertainties and challenges, before continuing with a description of the specific type of challenges SMEs are facing which leads to the research question and ends with a description of the purpose and motivation fueling this research.

1.1 Background

In the beginning of 2020, many were not aware how much our lives were about to be changed by the pandemic of COVID-19, which had started in late 2019. The disease turned into a global pandemic. Throughout its development, it changed the way we work, live and socialize. Ratten (2020) has described that a new normal has been created, where social distancing and working from home are essential parts of everyday life. Furthermore, in many countries facilities and businesses were limited in the way they operate or had to shut down completely. One example are German Schools and non-essential businesses, which had to shut down, gatherings got banned, curfews were instituted and stay-at-home orders as well as travel restrictions were introduced (Bundesregierung, 2021). Businesses not only had to deal with all the new regulations imposed on them, but they needed to react to the new lifestyle of individuals in order to avoid falling victim to the pandemic. Being able to remain accessible to customers and consumers became a challenge.

Ansell and Boin (2019) pointed out that in our age, due to the increased pace of life and the immense amount of information made and processed it is difficult to anticipate crisis events. The amount of ‘unknown unknowns’ are expected to be exponentially growing leading to them being more threatening. As these are difficult to plan for they are not considered in many crisis planning models and can therefore result in grave consequences for companies (Kim, 2012). They further argued that the vast complexity of intertwined systems leads to more frequent global crises as general complexity provides more room for errors. Naturally as these events influence life on an individual level, it has a similar impact on the organizational level as well. Challenging leadership through a crisis, fostering change management, enforcing adaptation

2

by emphasizing the ‘survival of the fittest’ approach. The complexity of the problem further deepens if we admit that there is no best way, as every case is different.

When speaking of a crisis, there is a huge spectrum of extraordinary events ranging from pandemics, through natural disasters to social disturbances such as social crises situations such as social turmoil and riots. All these can threaten markets, infrastructure, and paradigms which were ‘normal’ up until the point of the crisis. (McConnell, 2011) In order to survive such volatile events, actors on the market need to adapt to the quickly shifting circumstances. Mack and Khare (2016) emphasized the importance of adaptability as in our modern systems the environment is constantly shifting toward a more VUCA (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, Ambiguous) oriented state. They argued that this might be the consequence of the fact that the most frequently applied managerial tools and frameworks remained unchanged. They are still the same, meanwhile the environment itself, the actors and the processes went through many iterations, increasing uncertainty and informational asymmetry. During an ongoing crisis, gaps in available products and services tend to be exposed as suddenly new needs rise. Unique opportunities often present themselves, which in turn can be exploited by innovators who are agile and able to address these problems and therefore close the arisen gaps (Morgan et al., 2020).

1.2 Problem Discussion

Crisis events pose many challenges to individuals, the society, and to economic actors as well. In our context especially small and medium sized enterprises (SME), who lack the vast resources of larger companies, face a major challenge. They need to keep adapting in such a changing environment, under strenuous time pressure. Without the reserves large companies usually possess, smaller organizations experience a higher level of pressure stemming from the external volatility. The liability of smallness implies that the smaller a firm is, the more vulnerable it can be to exogenous shocks (Eggers, 2020). Size and reserves are what matters in an attrition of war and small businesses do not necessarily possess enough to weather these storms without drastically changing their business model. Morgan et al., (2020) also pointed out that some actors on the market have the power to negotiate special arrangements with local government or authorities, due to their perceived importance in the local economy and market. They also coined the term, ‘too big to fail’ regarding businesses which grew large enough to be sheltered from lethal consequences of exogenous crises, such as the pandemic. Since the outbreak, equity investments drastically dropped due to the drastically increased uncertainty,

3

putting a strain on smaller businesses and start-ups in need of external financing (Brown & Rocha, 2020). Clearly, this can result in reduced growth potential for SMEs, sometimes even completely inhibiting their expansion.

SMEs make up a large portion of the economy, in the US for example, 50% of the workforce is employed by them (Bartik et. al., 2020). If a large number of them go bankrupt, it poses a systematic risk to the whole economy. Unfortunately, SMEs tend to respond to economic uncertainties by reducing their borrowing & lending behavior which can render many measures implemented by governments to aid struggling companies less useful than they would otherwise be (Cowling et al. 2020). Additionally as a big portion of the population is employed by SMEs, them going bankrupt in a large number can put the livelihoods of many households in jeopardy. SMEs are an integral part of the economic landscape and a decrease in their number can produce the above mentioned micro and macro level problems (Cowling et al. 2020).

Exogenous shocks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic can cause major disturbance on the market and end up rendering current business models ineffective. In such cases, especially amongst SMEs, pivoting is considered a versatile tool to reposition oneself on the market in response to these shocks. (Morgan et al., 2020). As SMEs are exposed during a crisis event, and in most cases without extensive reserves, they have to rely on their personnel knowledge and managerial instincts in order to make the right decision to navigate such an environment. SMEs have to rely on constant generation of revenues in order to be able to finance day to day operation because of the lack of reserves (Cowling et. al., 2020). During the pandemic, family businesses and SMEs are dealing with discouraged investors, diminishing number of customers and challenges regarding remote work (Castoro & Krawchuk, 2020). In sense of the above-mentioned aspects, our research aims to:

“Gain insight and research the nature of decisions and actions taken as crisis management by strategic decision makers in SMEs in order to minimize the negative impact of the pandemic.” Thus, the identified research gap and lack of understanding regarding what kind of measures were taken by decision makers in SMEs that have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic formulated our research question:

How did SMEs react and what measures did they take, in order to cope with the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in their strategic context?

4

The purpose and the research question is designed to provide valuable insights based on relevant data and literature for actions and steps taken by SMEs in order to minimize damage caused by the direct and indirect impacts of the pandemic. Focusing mainly on the nature and consequence of strategic decisions made by responsible stakeholders such as managers or leaders. Although Ansel and Boin (2019) pointed out that crisis management happens on two levels, both operational and strategic, this paper will mainly focus on the strategic decisions taken, and their relevance and extent of success, looking into why a given measure was thought to be a solution, and what measures were actually employed by SMEs. Throughout the study we follow the definition of SMEs proposed by the EU Commission (2003). The definition of SMEs is based mainly on head count, but either turn over or balance sheet total can be used for classification as it can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1: Factors determining whether an enterprise is a SME (EU Commission, 2003)

1.3 Purpose

The aim of this research is to gain a better understanding of decision makers’ reactions in SMEs, through gathered qualitative data in the context of the economic and social crisis caused by COVID-19. We are expanding the knowledge about the way in which members of organizations, holding decision making power, ranging from CEOs to managers, changed processes and made decisions in reaction to the crisis. The context of contingency theory is applied, leaning on the framework of crisis management proposed by Pearson and Mitroff (1993), as well as the relational model of crisis and issue management by Jaques (2007). The study is further interested in whether amongst the different scenarios similarities can be observed. This is done in the context of crises and change management, and based on this the viability of contingency theory is researched. As the pandemic is identified as the exogenous shock in this study, we are aiming to provide a better understanding on strategic decisions

5

which were able to mitigate the effect caused by the global crisis ignited by the spread of the virus, focusing on the context of SMEs.

In these turbulent times no single set of actions can be pinpointed as of now, which would without a doubt lead to the survival of a given company. This is in line with the basic idea of contingency theory, which suggests that solution and the right approach is always highly dependent on the variables and external or internal circumstances, hence no best and universal solution can be identified (Donaldson, 2001). Thus, the identified research gap of crisis management in contingency theory is studied in this paper. The lack of already proven ways of solutions facilitates leaning on instinct, further resulting in a wide variety of approaches. However, defining and using a framework to evaluate different approaches might help to conceptualize some approaches pointing towards methods that can be used in a more general set of aspects.

6

2. Literature review

In the literature review a synopsis of the COVID-19 pandemic is provided, the economic effects as well as the specific impacts on SMEs are touched upon. It introduces both contingency theory as well as the phenomena of crisis management. The literature review is concluded by taking a look at previous research in the field of crisis management and contingency theory, discussing their mutuality.

As, at the time of the research [Spring of 2021], the pandemic was still ongoing and new information and findings were emerging rapidly, therefore the segment concerned with COVID-19 is subject to change. It is rather aimed at informing the reader about the context we were conducting our research in, presenting the environment. Furthermore, the effects of the crisis are presented, with a focus on the economic implications, with SMEs in the centre. Crisis management and contingency theory and their relevant previous literature are discussed, ultimately pin-pointing the theoretical gap of crisis management in contingency theory. The literature that this study is based on has been gathered from multiple online and written sources specifically, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect and the Jönköping University Library database (Primo). Once the literature had been gathered it was cross checked with the Academic Journal Guide (Chartered Association of Business Schools, 2018), this guide rates the quality of journals on a scale 1 to 4* starting with the lowest and respectively ending with the highest a 4*. We checked the quality of our sources with this guide and most of the journals with a rating of less than three have been removed from our literature list. Those that remained were thoroughly reconsidered, based on their relevance and other metrics of research quality, such as impact factor and Cite Score. Only peer reviewed journals were used throughout our study. The search for literature was repeated multiple times due to the situation still evolving and a lot of findings were being released at the time of writing. In order to ensure an in-depth collection of relevant information and preliminary knowledge, the literature list was constantly revised during the study.

7

2.1 The COVID-19 epidemic

The virus known widely as COVID-19 (SARS-CoV2) was discovered for the first time in 12.2019 in China. It was originally reported to the WHO by Chinese authorities as pneumonia of unknown cause (Gorbalenya et al. 2020)..

On 07.01.2020 it was classified as a strain of Coronavirus by the Chinese authorities. The virus is believed to be a spill over from animals and developed the ability to spread from human to human (Liu et al. 2020) The weeks following the first cases outside of China were reported in Thailand, Japan and Korea all of these were travellers that had previously been to China (WHO, 2020).

The virus swiftly started to spread and turned into a global occurrence, in 03.2020 it got classified, by a global team of 17 researchers, as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronaviruses (SARS-CoVs) (Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, 2020). While the virus was originally geographically quite limited it continued to gain traction over the months since the first recognized cases, at the time of writing (19.05.2021) there were over 5 million cases being reported weekly as can be seen in Figure 1 (WHO, 2021a).

8

2.1.1 Economic implications

The on-going crisis led to the current world increase in volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity. So called VUCA scenarios, they are the subject of many discussions, known as a phenomena, referring to the informational anomalies present in the environment, resulting in a complex and unpredictable market (Mack & Khare, 2016). As the virus started to engulf the whole planet, most countries were reacting with policy measures and a wide range of different restrictions. Those had a severe impact on the world economy, closures of borders, restrictions on air travel as well as a heightened degree of uncertainty in a rapidly changing global environment which resulted in a “global stress test” affecting all aspects of our lives (WHO, 2020; Rattan, 2020). This large-scale crisis led to a global recession by the first quarter of 2020, in June the World Bank predicted the largest per capita income contraction to occur since 1870 (World Bank, 2020).

Increased uncertainty especially affected SMEs. Small to medium sized companies are an integral part of many global economies, making up a significant portion of local economies (Eggers, 2020; OECD, 2020a). The OECD (2020a) found that many of the SMEs are struggling with the effects of the pandemic on a global scale. These issues are multifaceted and range from having to pause operations, to having their supply chains disrupted, being forced to lay-off employees and facing liquidity problems.

2.1.2 Exposure of SMEs

SMEs are affected on two sides. Both the side of supply and demand were exposed to damage. On the supply side they faced issues due to the disruption or sometimes even total collapse of their supply chains. Furthermore, the mobility of their employees was being restricted and they might have been subject to additional quarantine rules. In addition to those issues, many employees also had to look after dependents and children due to school closures, limiting their availability for work. These circumstances lead to a shortage of the labour supply (OECD, 2020b).

Taking a look at the demand side, they were facing a sudden loss of orders, which eventually resulted in a decrease in revenue. This led to the fact that many companies were facing liquidity issues. Those got further exacerbated as consumers were reducing their spending and consumption as a reaction to increased uncertainty and a loss of income (OECD, 2020b; Klein & Todesco, 2021). Many SMEs and start-ups were struggling to secure their financing as they often lack assets that they could borrow against (Brown et al., 2020 & Cowling et al., 2020).

9

Because of this fact they are overly reliant on equity investments. For example Brown et al. (2020) found that in the UK sources of funding significantly decreased in the last months in the SME environment.

SMEs rely more than other firms on constantly generating revenue as it is more difficult for them to access other sources of funding (Cowling et al., 2020). Bartik et al. (2020) who conducted a survey among 5800 SMEs in the United States found the same, with many businesses being financially fragile. In the median the SMEs were facing monthly expenses of over 10.000$ which is vastly higher than the reserves they have. Of the businesses surveyed 43% were temporarily closed and they reduced their employee numbers by around 40%, showing that relying on their reserves is not a sustainable approach.

As found by the OECD (2020b) many SMEs might not survive this pandemic, this is in line with the predictions of Bartik et al. (2020). Due to this large-scale crisis, many effects were spilling over into the financial markets. This even worsened liquidity problems for organizations as it made it more difficult for them to get financial help to overcome liquidity issues (OECD, 2020b). An additional factor making the situation more challenging is the fact that in crisis and uncertainty smaller companies tend to be more adverse to taking on additional credit. (Doshi et al., 2017). Even if they decided to take up credit, they would then be liable to repay those once their financial situation improved, therefore extending the time financial strain is put on them.

The issue of being more prone to crisis events due to their small size, resulting in less options when it comes to gaining appropriate funding for operational aspects is described as the” Liability of Smallness” (Eggers, 2020). Many SMEs were reliant on getting external aid to survive this crisis, however there are serious concerns about the availability and access to get financial aid (Bartik et. al., 2020; Brown et. al., 2020)

Many SMEs did not remain idle and took the initiative in the ongoing pandemic. However, the way they reacted to the changing externalities shows a wide variety. As these changed externalities demanded new and different skills, they had to adapt, for example through digital transformation. If they failed to adapt appropriately, they were forced to temporarily or permanently close (Klein & Todesco, 2021; SEBRAE, 2020). Beqiri (2014) even claimed that many companies that filed for bankruptcy went down not only because of the crisis, but also because they were not intent on implementing radical changes, for example adapting their business models. These statements are further supported by Osiyevskyy et. al. (2020), claiming

10

that the severity of a crisis acts as a positive contingency on idea and opportunity exploration for a given organization. Sedláček and Sterk (2017) also showed that shocks on the market can lead to the birth of many new firms, due to booming demands in new areas.

One of the main reactions when it comes to digital transformation is using new online sales channels, for example in Brazil almost one third of SMEs started selling through social media as a new approach (SEBRAE, 2020). Nevertheless, many companies also had to reduce their overhead, as in their survey amongst SMEs Bartik et al. (2020) found that many companies were laying off workers and closing physical locations and facilities. This was likely done in an attempt to tackle liquidity issues and an attempt to make the oftentimes limited funding stretch as far as possible retaining some of the reserves.

2.1.3 Government restrictions & support affecting SMEs

As the pandemic is a global phenomenon, governments reacted differently depending on the country (University of Oxford, 2021). As our research focuses on the two European countries of Germany and Hungary, we took a closer look at the restrictions that had been put in place by their governments as a reaction to COVID-19.

The regulations for companies in Germany were quite limited. All of them had to develop a hygiene concept. They also had to make home office possible if the nature of jobs allowed it. Besides this, jobs that still require presence had to offer at least one free of charge COVID-19 test to their employees per week. Schools and kindergartens got closed for extended periods but were slowly reopening at different pace with hygiene concepts and reduced attendance numbers. Furthermore, there was a limit on the number of people that were allowed to gather, which was five, including a maximum of two households (at the time of writing 05.2021). In publicly accessible spaces it was mandatory to wear masks of the FFP2 or KN95/N95 certification (Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung, 2021).

Based on the official COVID-19 Taskforce of the Hungarian Government, first restrictions were issued in 03.2020. For the following year, restrictions and regulations were varying but continuously present. The government issued employers, to let their employees work from home, if it is applicable, restaurants, pubs, tourist accommodations and hotels had to cease their operations and a curfew was introduced (Hungarian Government, 2020a).

Similarly, in Germany cultural life had been mostly shut down as well with bars, restaurants, clubs, cinemas, theatres and other venues being closed. However there had been ongoing

11

discussions about reopening strategies for certain areas depending on the current infection numbers (Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung, 2021). As Germany is a federal state the regulations vary between each state and get adapted frequently depending on current infection numbers. However this also led to a difficult to overview situation with varying rules and regulations varying depending on the federal state in Germany (ZDF, 2021). One part of the strategy to combat the spread of COVID-19 was the introduction of free tests for all citizens. This aimed at providing a certain level of security for citizens, and allowed them to get one test a week (Staatsministerium Baden-Württemberg, 2021; Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung, 2021)

In both Hungary and Germany, international travel, especially entry was significantly limited by authorities, border control was tightened with mandatory quarantine rules applying (Police of Hungary, 2020; Auswärtiges Amt, 2021). The increasing number of infections led to, all non-essential facilities, shops and services getting shut down, schools and universities converted to digital education and festivals, concerts and other events and gatherings of crowds were banned or postponed (Police of Hungary, 2020; Hungarian Government, 2020b; US Embassy in Hungary, 2021; Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung, 2021)

The OECD (2020b) expects that the financial support instruments will still miss many companies, due to misfit or being too late for others. As with governments reacting differently on the restriction level they also react differently when looking at the way they support businesses during this time of crisis. Support is presented in Table 2, as it provides a quick overview over the measures taken by the German and Hungarian governments.

Table 2: Measures to support businesses in Germany & Hungary adapted from OECD, 2020a

Germany offered a number of different ways to support businesses, in this context mostly already existing channels were used. One important measure was providing better access to short term work arrangements (Kurzarbeit). This was aimed at reducing the number of workers

12

getting laid off as it allowed companies to reduce the work time of their employees while the government covered a big part of their wages (Arbeitsagentur, 2021).

In Hungary similar developments took place, a number of measures were introduced to support struggling businesses, a list of industries was also provided later on, which got approved for wage support. meaning the Hungarian Government paid a part of the wage of the employees in a given sector, to ease the pressure on employers (Salgó, 2021).

There were also a number of other measures introduced, among these were social security exemptions for the sectors most affected by the crisis, as well as suspending loan repayments. Pausing evictions for individuals and small businesses falling behind on rent payments, as well as providing tax free operation for SMEs for up to four months (Hungarian Government, 2020a). The Hungarian Government (2020a) further announced that loan repayments would be frozen until the end of the year 2020 to help individuals and SMEs to financially cope with the pandemic. This measure aimed at reducing the number of companies that had to declare bankruptcy because they were falling behind on payments. With the same goal in mind changes to the insolvency law in Germany were introduced. German insolvency laws were adapted, pausing the legal requirement of firms to declare bankruptcy (Bundesministerium der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz, 2021). As one more measure an economy stabilization fund was put in place on 25.03.2020, this whole fund had the size of over EUR 750 Billion, it also includes help specifically tailored for SMEs of EUR 50 Billion (OECD, 2020a).

Similar measures were introduced in Hungary, therefore on 08.04.2020 the Central Bank announced a HUF 3000 Billion (EUR 8.6 Billion) support package of which 50% were available to refinance SMEs (OECD 2020a, Hungarian Government 2020b).

To specifically target start-ups which often fit the definition of SMEs, Germany introduced a start-up support scheme of a volume of EUR 2 Billion. This program is aimed at equity financed start-ups and is offering support if they are facing liquidity issues, as many of the other programs do not apply to newly founded companies as it is shown in Appendix 1 (OECD, 2020a).

2.2 Contingency theory

Contingency theory is a major theoretical approach to management, organizational fit and leadership. As we are conceptualizing our framework around contingency theory, it is important to clarify how this paper interprets it. Throughout the study, we follow the main

13

statement of contingency theory, that says: in organizational management there is no single best way for decision making or leading and organizing, but it is dependent and contingent upon the external and internal circumstances and variables, meanwhile different ways of organizing are not equally effective (Donaldson, 2001; Ketokivi, 2006; Tosi & Slocum, 1984; Burns & Stalker, 1961; Eriksson-Zetterquist et al., 2020). This approach is deemed viable in the sense of this research as it is mainly concerned with the uncertainty of given environmental variables. This is further supported by Otley (1980), as he claimed that organizational features are dependent on specific circumstances, identified by the firm itself.

Its paradigms state that organizational effectiveness is significantly dependent on the extent to which the characteristics of the organization could be adapted to the circumstances (Donaldson, 2001; Osiyevskyy et. al.,2020). Uncertainty is a central aspect of contingency theory, which further supports the need for flexibility and the ability to adapt, based on the individual circumstances of given organizations (Donaldson, 2001; Ketokivi, 2006). This fact further strengthens the choice of contingency theory to look at crisis management. Tosi and Slocum (1984) submitted that most discussion on contingency approaches claim that performance is based on the fit of several factors, such as structure, personnel, strategy, or culture, to mention a few.

Based on the discussion of Otley (1980), we can further theorize that the contingency theory of crisis management states that there is no universal, single set of actions that would without a doubt help a given organization to successfully manage a crisis. The designs of systems for control and planning should be specific on the individual level (Dermer, 1977). Eriksson-Zetterquist et al. (2020) argued that contingency approach theorizes that due to the different environments of organizations, the design of an organization should depend on its contextual conditions, both internal and external. Donaldson (2001) further supports this statement, by arguing that organizational structure can (and should) be fitted to relevant contingencies, and if done properly, it should yield high performance, meanwhile a misfit of contingency-based structure will result in low performance. Despite in the early literature it was claimed that methodological approaches in justifying the importance of contingency theory had criticism, regarding the measurability of variables (Mitchell et al., 1970), contingency theory became a widely accepted management theory evolving from leadership theory. Hanisch and Wald (2012) pointed out how contingency theory remained one of the major theoretical branches of management theory, despite in many fields its literature is still being fragmented or unspecified.

14

Contingency theory literature converged upon two main perspectives, the Cartesian view on fit or Configurational fit. The Cartesian view was mainly focusing on ‘why’ certain contingencies affect certain practices of one organization, assuming that there is a continuous relationship between the factors, meaning, that an incremental change of a given factor results in an incremental change in the value of an organization (Donaldson, 2001). The other main approach, the Configurational view on fit, theorizes that organizations and their environments are considered and interpreted as a system (Eriksson-Zetterquist et al., 2020). As each component interrelates with many other components, they are not defined by their change (like in the Cartesian view) but by their role in the system. Hence, relationships between different factors are defined as configurations, theoretically leading to an endless number of combinations based on factors. As Luthans & Stewart (1977) argues, the increasing environmental impact and rate of change, with an increased degree of complexity, implies the more significant importance of variables or contingencies, implying a constant interest amongst researchers in contingency theory. Both the Cartesian and Configurational fit are mainly researched through quantitative analysis, due to quantifiable variables (Eriksson-Zetterquist et al., 2020).

In a contemporary view, contingency theory differentiates between two organizational systems; these are organic or mechanic (Chenhall, 2006). Organic systems have a tendency to be positively related to uncertainty, while mechanic systems are positively related to certainty. In contemporary research contingency theory is mostly tested in culturally homogeneous societies and considered to be helpful for all parties in the value chain, as in many cases it includes not only the organization itself, but its suppliers, transporters or consumers as well (Eriksson-Zetterquist et al., 2020). Burns and Stalker (1961) were the first to introduce the difference between mechanistic and organic approach of management, claiming that mechanistic is best in times of stability, while organic excels in tackling unstable and volatile periods. Whalen et al. (2016) introduced the contingency approach that is applied in highly uncertain fields, such as marketing. We argue that crisis management poses such an in depth uncertainty, that a contemporary contingency approach in the sense of general uncertainty and ambiguousness is a viable theoretical perspective to research and include crisis and issue management. There are extensive lists of contingencies, trying to gather and list all the different external and internal variables that should be taken into consideration (Tosi & Slocum, 1984), however as these factors tend to be highly specific for organizations (Otley, 1980), we refrain to list them as this research is not limited to given industries. It can be seen that the different

15

approaches of contingency theory, like Cartesian or Configurational, with the introduction of Contemporary, discusses a lot of different phenomena. However, none has been before tied to crisis management. Despite contingency theory being concerned with uncertainty and firm specific variables, there is a gap regarding contingency theory literature discussing crisis management.

2.3 Crisis and issue management

Crisis management literature is split into two main perspectives, on one hand considering a crisis as a singular event, which is easy to identify and pin-point. It is clearly distinguishable on a timeline. On the other hand, a crisis can be perceived as a sequence of continuous sub-events resulting in the crisis itself being a process. (Pedersen et al., 2020). Both strands of literature agree that without being managed appropriately, crises result in negative outcomes. The literature of crisis management, however, aligns on the fact that crisis management is the process aimed to lessen the impact and damage a crisis can induce in an organization and its stakeholders. Some identified the importance of the different phases of a crisis, such as pre-crisis, crisis and post-crisis (Coombs, 2007). These three phases became a commonly incorporated approach in crisis management literature based on Coombs and Laufer (2018). Drawing from Fink and Mitroff, Coombs (2007) described the life cycle of a crisis by four interrelated factors. These factors are firstly the “Prevention” which is describing how well an entity is able to detect warning signals, the next factor in this model is “Preparation”, describing whether and to which degree an organization is able to identify its own vulnerabilities and develop a plan to counter them. The third factor in the model is “Response”, which encompasses how well the tools developed during the preparation stage can be applied, and how well they adapt to new circumstances. Lastly the “Revision” topic is the process of the evaluation of the response.

Jaques (2007) pointed out the fact that several sources treat an event of crisis as a linear chain of subsequent events, resulting in linear crisis life-cycle models. He also proposed the relational model of issue and crisis management which follows the above mentioned life-cycle composed of four aspects as shown in Figure 2:

16

Figure 2: Issue and crisis management relational model by Jaques (2007)

The model itself presents four major clusters: Crisis Preparedness, Crisis Prevention, Crisis Incident Management and Post-Crisis Management. They represent the different aspects tackled during a crisis. These elements are not necessarily taken in sequential order, there are cases where simultaneous reactions are desired to avert a crisis. In this study we consider this model as a general guideline to put crisis management into a frame of reference as it provides a detailed representation of the different aspects of crisis management. The model influenced and helped us prepare and assume the right methodology for the research, providing a comprehensive but compact framework for crisis management. In the paper our assumptions are based on aforementioned models, interpret crisis management including the four aspects defined above. General preparedness of firms are considered just as important as the more hands-on aspects of prevention and incident management. Furthermore, despite the fact that the crisis is still on-going, some organizations might have already entered the post-crisis management phase, as these phases can happen simultaneously (Jaques, 2007).

Pearson and Mitroff (1993) outlined five stages regarding crisis management. Supporting previously discussed literature and the choice of Jaques’s (2007) model, they also identified different stages throughout the life-cycle of a crisis. The first and second stages are defined as preparation and prevention respectively. Stage three is considered damage containment, which

17

is in line with the response factor mentioned before. However, Pearson and Mitroff (1993) considered recovery a different stage, and learning as a final stage, which is part of the next crisis as prevention. Due to limitations, which are discussed later on, we decided to use Pearson’s and Mitroff’s (1993) discussion as a secondary approach besides Jaques’s relational model (2007), which is more compact and takes a novel approach on defining contemporary crisis cases. It is used to set a general framework for the discussion of crisis management throughout the research.

Complexity and volatility in a crisis should be approached in an innovative way, scrapping established practices and ways of thinking, breaking up with routine processes (Ansell & Boin, 2019), bringing entrepreneurial approaches into the spotlight. Osiyevskyy et. al. (2020) claimed that during a crisis, firms either react by exploration or exploitation to keep their organization and strategic fit in line with the shifting environment. It is assumed by literature that organizational culture and the people involved have a significant role in shaping the response of an organization to crises, as general agility of teams, or group dynamics is considered an essential factor. It is further discussed that effective leadership, coordinated teams and motivated employees are an important aspect of crisis management (Bhaduri, 2019). Veil (2011) made an attempt to connect the theoretical gap between crisis management literature with rhetorical theories identifying barriers prohibiting learning from crises, mainly focusing on the post crisis phase of crisis management. She emphasized the importance of a mindful organizational culture and the opportunity that by learning from post crisis stages, future crises can be averted or their consequences can be made less threatening by allowing organizations to gain a universal approach of dealing with crisis situations. Another important aspect of crisis management is the contradiction of being prepared and being able to improvise. Barrett (2012), showed that top managers like to show or present the impression that everything is going according to a plan. There are contingency plans, a strict structure, of what needs to be done during a crisis. They even have drills to simulate challenging situations. Meanwhile it was shown that during such periods, actors take actions without plans, making up reasons on the go, discovering new perspectives and opportunities along the way of an ad hoc reaction (Barrett, 2012). Castoro and Krawchuk (2020), reached a similar consensus in their research regarding COVID-19, that agile managers were needed to act upon the current reality, pivoting adaptive solutions.

However, based on literature it seems that two common propositions have taken foothold: problems left unaddressed trend towards increasing in seriousness, and the longer an issue is

18

present, the number of solutions decrease as the cost of intervention dramatically increases (Pedersen et al., 2020). Foreshadowing the importance of speed and reaction time, as well as the ability to adapt in such environments. It must also be mentioned that the perception of threat can be the catalyst for strategic responses (Osiyevskyy et. al., 2020)

Shirokova et al., (2020) claimed that macro-level or industry-wide economic crises as an exogenous shock affect SMEs differently. One of the most common interpretations of crises amongst managers of SMEs is financial instability (Herbane, 2010). Besides the significant impact on public health, COVID-19 also led to a major economic shock, as massive dislocation among small businesses followed the collapse of supply chains due to regulations aimed at containing the spread of the virus (Bartik et al., 2020). The COVID-19 crisis facilitated SMEs to adopt digital technologies and highlighted the importance of knowledge, as knowledge plays a significant role in overcoming the pandemic (Klein and Todesco, 2021). Klein and Todesco (2021), claimed that knowledge management and digitalization were the main tools employed by SMEs in response to the pandemic. Although the process of digitization can encounter a range of different limitations based on industry or sector, we hypothesize that it is still one of the most cost efficient and dominant tools employed by SMEs as a method of crisis management. To define the successfulness of crisis management, we incorporate the approach proposed by Pearson and Clair (1998), thus crisis management efforts can be considered successful if an organization is able to sustain its operation, maintain or regain its momentum and resume its core activities by transforming input into output, satisfy customer needs, while minimizing stakeholder and organizational losses.

Change, crisis and issue management are an essential part of this research. It is important to define crisis precisely in our context, as nowadays the term is overused, even abused in some contexts by social sciences and in everyday language (Shrivastava, 1993). We follow Coombs’s (2007) proposition, that a crisis is defined as a significant threat and disruption to operations resulting in negative outcomes. In our given case we can also define a crisis as the subsequent chain of events caused by the COVID-19 pandemic or more directly, the pandemic itself will be referred to as the crisis in our paper.

2.4 Crisis management through the lens of contingency theory

Literature is vast and detailed on the different aspects of crisis, and varying approaches to crisis management exist. Despite the fact that literature on crisis management expanded exponentially, we found that the literature is still fragmented, which is in line with

19

Shrivastava’s (1993) findings, who stated, the literature is scarce and the approach is still dominated by ad hoc reactions. Further supporting these suggestions, Herbane (2010) argued that despite small firms being subject to many studies, SMEs’ crisis management is a neglected topic:

“...database searches of the title and abstracts of the International Small Business Journal (1982–present), Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development (1994–present), Journal of Small Business Management(1962–present) and the Journal of Small Business Strategy (1990–present) found that not a single article published in these journals made reference to [...] ‘crisis management’...” (Herbane, 2010, p. 44)

Although literature suggests that COVID-19 had a serious impact on SMEs, studies as of now are scarce on the nature of measures they took to cope with the given situation. Issue and crisis management through the lens of contingency theory, based on our research into literature, seems to be a so far uncharted field of study. Especially considering that contemporary studies of contingency theory focus on marketing or accounting, meanwhile a contingency approach in the sense of crisis management is rarely mentioned (Eriksson-Zetterquist et al., 2020). This provides an opportunity to investigate crisis management in the context of contingency theory. In contemporary contingency theory, despite the relevance of changing variables in the environment, crisis management is not discussed. Thus, researching the process of crisis management based on the contemporary approach of contingency theory presents a research gap. As it was discussed in the literature review, in order to build the theoretical framework, the foundations of contingency theory is based on the organization dependency on uncertain environmental variables, meanwhile crisis and crisis management are defined with volatility and uncertainty. Contingency theory is used to contextualize the uncertainty that is the very trigger and essence of the process of crisis management.

Previous research into crisis management was also dominated by case studies, as they are perceived to represent the unfolding of a crisis well in a given situation (Doern et. al., 2018). By expanding sample size, a better scope of different variables can be captured.

We will take a look at the ‘why’ and ‘how’, of the appropriate measures taken to fit the approach of crisis management of the individual SMEs. This is essential in order to test contemporary contingency theory in the field of crisis management. As the pandemic itself is a recent, still on-going event, literature and research is novel in the field, saturation of knowledge is not identifiable. So far individual case studies dominate the literature regarding

20

adaptation and struggle of organizations impacted by the direct and indirect effects of the world pandemic. Contemporary contingency theory can be the foundation of a universal framework for crisis and issue management as they share many theoretical similarities.

Despite the shared fundamentals of crisis management and contingency theory, embedded in the context of uncertainty and variable dependency, based on Herbane (2010) and Eriksson-Zetterquist et al. (2020) crisis management was not discussed in-depth through contingency theory. Therefore in this research, crisis management will be embedded in this context, to make a fit of contingencies in crisis management. An optimal alignment presents itself, as both crisis management and contingency theory are mainly concerned with uncertainty and volatility on an organizational level.

21

3. Methodology

In the following section we present the ontological and epistemological foundations of the research, as well as the given methods used to gather and analyse the data. The qualitative research design will also be introduced in detail, including the philosophy, approach and strategy of the research. The alignment of philosophy, approach and strategy is essential in order to be able to design coherent and reliable research (Staller, 2015). Sampling or selection, it’s criteria and the nature of data are also discussed as well as our chosen method to convert data into information as a tool to develop knowledge and provide insight into the researched topic.

3.1 Research philosophy

The purpose of this study is to understand how, why and which decisions were taken by decision makers (managers, stakeholders etc.) in SMEs in order to cope with the ambiguous and abrupt impact of the COVID-19 crisis. Our aim is to get an insight based on the experience of people responsible for making given decisions. In order to understand the experience of those decision makers, we are to connect and interact with them. Their reality is not separate from ours, on the contrary, it is our aim to be a part of it. We, in order to get a better comprehension on the topic, with regard to subjectivism, assume the ontological approach of relativism. Ontology conceptualizes the nature of reality and is concerned with what there is to know (Ritchie et al., 2014). In relativist ontology it is stated that reality is a finite subjective experience, thus reality is defined by human experience (Levers, 2013). We expect that our candidates will construct and interpret reality based on the context of their own environment. There are ‘more than one’ truths, as facts are dependent on the observer’s point of view and their perception of the environment (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Ritchie et al. (2014) claimed that in relativism there is no one shared social reality, but the set of individual and unique constructions.

In relation to our chosen ontology of relativism, social constructionism is considered as an appropriate epistemology. Epistemology is the approach of learning about the world and reality (Ritchie et al., 2014). Social constructionism supports the assumption of relativism, as Easterby-Smith et al. (2018) suggested, that reality is determined by people and not necessarily

22

by objective and external factors. As Levers (2013) argued, in constructionism meaning is made through the interaction of the interpreter and interpreted. Since the candidates will describe their experience, the result will depend on their involvement and their individual interpretation of their own reality. This implies that reality itself is influenced by the language, social and cultural context of individuals, defined and contextualized by their own experiences. Our choice of adopting ontology and constructionism is further supported by Ritchie et al. (2014), as they describe individual interviews as a method where generation of data is embedded in the verbal communication and perception of participants and its interpretation is based on the researchers. Nonetheless, Blaikie (2007), warns that in constructionism reality is affected by the research process itself, objective value-free research is hardly possible, meanwhile reality cannot be portrayed accurately as different (even competing) perceptions are present. In order to handle these aspects of our philosophy, we as researchers aim to be as transparent as possible, meanwhile we try to adopt a neutral position in order to minimize our personal influence throughout the process (Ritchie et al., 2014).

3.2 Research Approach

We aim to use an inductive approach of theory formation, as our assumptions are derived from the data and constructs produced by the analysis of the responses for the semi-structured interviews which is described in more detail under the segment methods (3.4). Inductive reasoning is mainly concerned with making predictions on novel cases, supported by existing knowledge and observation, pointing from individual cases to a more general interpretation (Hayes et al., 2010). Knowledge is built from the bottom up, through observation of the environment, which makes the foundation of theory development via the discovery of patterns that might be able to explain the data (Ritchie et al., 2014; Berg & Lune, 2017). Inductive reasoning is applicable, as we are researching the different approaches employed by decision makers in SMEs to cope with the impact of COVID-19, by making assumptions based on our observations (Locke, 2007), linking it to theory in order to build a better understanding. In line with social constructionism, Crotty (1998) pointed out that the engagement of the viewer and viewed, is what ultimately leads to the perceived truth and meaning to come into existence. Priori definitional codes are not present (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Therefore, our observations and interactions will make up the basis of our inductive and exploratory way of contributing to the theory of crisis management considering COVID-19, through the perspective of contingency theory.

23

Throughout the process of the construction of theory, researchers should be independent entities with nonlinear relationships towards the data as they should acknowledge the fact that as theory emerges, it is significantly influenced by the individual interpretation of the researchers (Levers, 2013). Preconceptions should be taken into account as the researcher is expected to have knowledge of the topic to a given extent. In order to tackle these challenges, we acknowledge that there should be a bridge in understanding between existing knowledge and emergent new ideas in relation to what the data shows (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Furthermore, we have produced an extensive review on literature concerning our chosen topic, in order to gain the necessary knowledge to be able to probe deeper into the studied cases, meanwhile staying coherent with previous studies. In addition, in many cases qualitative studies are initiated because researchers are interested in a topic, which can suggest that they have preconceptions (Berg & Lune, 2017). Our extensive literature review also helps to reduce the influence of such presumptions.

3.3 Research strategy

Qualitative research is more concerned with theoretical generalization than numerical generalization (Flick, 2021). He further argued that in order to increase validity of qualitative research, the research environment should be standardized. We aimed to set up the same staging and atmosphere for all interviews to help us minimize environmental noise. In order to do so, we built a predefined structure for our interviews, which should help minimize environmental influence on our results, regarding the interviews. To further help in ensuring this, we conducted a first test interview together, this enabled us to observe the way both of us conducted interviews. This enabled us to set the standard circumstances desired throughout all other interviews. Although it would have been preferable to conduct all the interviews, with both of us present, this was due to linguistic and time related limitations not possible. Exploratory and inductive research aims to understand a given phenomenon by fusing the interpretive horizon of researchers and research subjects, as social reality is dependent on culture and social background (Reiter, 2017).

Inductive strategy in a qualitative approach is concerned with extension or generalization, based on a selection of a specific group (Reichertz, 2021). In our case the broader group is SMEs which introduced various approaches to counteract the implications of COVID-19, meanwhile the subgroup is the set of representatives of SMEs we are doing interviews with. Even during generalization in qualitative research, explanation and context are intimately

24

correlated, generalities are derived from the understanding of specific phenomena or contexts (Mason, 2018). It is acknowledged in our paper that results and the validity of generalization is dependent on the context of data collection and our personal perception.

3.4 Methods

In our paper, a qualitative approach is taken, in the form of semi-structured interviews with decision makers who took action in response to the pandemic. Semi-structured interviews involve prepared questions guided by given themes providing flexibility for more personal answers and specifically inquiring and going into further detail, meanwhile keeping a systematic nature of data collection (Dumay & Qu, 2011). Main features of qualitative, semi-structured interviews emphasize the interactional exchange of dialogue, relatively informal yet topic-centered narrative, and they accept being dependent on context (Mason, 2018). Individual interviews are a way of data generation, which is based on verbal communication and personal narratives (Ritchie et al., 2014). The aim of the interviews is to identify what kind of strategic decisions were made to adapt to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic as a measure for navigating through the crisis. Sub-questions include: what decisions were made, how they were made, and why they were made in order to avert the outcomes of the exogenous shock caused by the virus. As the extent of success or failure is highly dependent on the perspective, measurement might prove to be abstract. The framework for crisis management proposed by Pearson and Mitroff (1993) complemented by Jaques’s proposed model of relational crisis and issue management (2007) will be used as the fundamental framework during our work to guide our analysis, interpretation and translation of data collected. We also discussed how success in crisis management can be interpreted in our literature review, considering Pearson’s and Clair’s (1998) approach.

3.4.1 Selection

Our selection is based on purposive sampling, as our topic required interviewees, who are eligible to be part of the sample based on given criteria, which were predefined by us. Purposive sampling is a form of non-probability sampling, where only those entities are included who meet the criteria to be involved in the sample based on the principle of the study or existing knowledge. (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018; Ritchie et al., 2014). In order to identify the set of eligible candidates, more efforts must be taken compared to random, or probability sampling, however nonprobability sampling, such as purposive sampling, tends to be the norm in qualitative research (Berg & Lune, 2017). In qualitative research, samples are selected on

25

purpose to facilitate the yield of information about the phenomena the research is focusing on, resulting in criteria specific selection (Merriam, 2002). Criteria have been already discussed in the purpose (1.3) of the research, however we provide a more clear statement here. These criteria are the following: directly be part of the strategic decision-making processes in a responsible role, which means, that our candidate actively participated and/or contributed to the decision that were made; in an SME that was clearly impacted by the implications of the pandemic, either directly (had to close facilities for example) or indirectly (operational interruption due to governmental restrictions as an example); measures were already taken in order to cope with certain aspects of the economical shock of the virus (such as introduction of new product, or reducing the amount of employees, taken as examples).

Due to better reach and exposure of the researchers, this paper considers the population from which sampling is done, German and Hungarian SMEs. In our literature review we also looked upon the general implication of COVID-19 in these countries, in the sense of governmental intervention and position of SMEs. The research does not explicitly search for patterns regarding different approaches in connection with the country of origin of SMEs, however it can be hypothesized that differences will be noticeable, due to the unique local regulations and micro-level contingencies. In Table 3 we present a detailed chart with information on our sample of interviewees:

ID Position Industry Country Size

INT_1 Manager Tourism Germany 120

INT_2 Owner Architecture Germany 28

INT_3 Owner & Founder IT Germany 12

INT_4 Production Manager Film

Production

Germany 15

INT_5 Owner & Founder Retail Germany 18

INT_6 Founder & CEO Clothing Germany 32

INT_7 Owner & Founder Construction Hungary 10

26

INT_9 Founder & Owner Marketing Germany 12

INT_10 Owner & Founder Education Hungary 110

INT_11 Senior Consultant Consulting Germany 52

INT_12 Owner & Founder Architecture Germany 14

INT_13 Managing Director Architecture Germany 130

INT_14 Head of Engineering Fitness Germany 11

INT_15 Brand Manager Food &

Beverages

Hungary 25

Table 3: Information of final sample

Throughout qualitative research sample selection should ensure inclusion of relevant events or processes that can contribute to understanding. Relevance of choice depends on whether the subject holds a characteristic that is expected or not. Symbolic representation is the essence of qualitative research sampling, as samples ought to represent and symbolise features important in the context of given research (Ritchie et al., 2014). Throughout this study, industrial differences will not be regarded during sampling, as we are researching managerial decisions made in a broader sense through the lens of contingency theory. Hence, the research will not be limited to one given industry specifically. Although patterns may rise regarding given sectors, sampling is not built around it. Therefore, the selection regarding organizations is based on eligibility of the criteria defined above, such as to be considered an SME in our research. This consideration was motivated by the official guidelines of the EU Commission (2003).

3.4.2 Interview Design

In qualitative interviews the researcher directs a conversation evolving around a certain topic (Lofland & Lofland, 1984). The goal is to get a better understanding of the “world” of the interview partner, and this is achieved by asking the participant questions which encourage them to further explain their view of the world. The researchers have to steer the interview while giving the participant enough room to explore their own ideas and worldviews. Occasionally the interviewer might have to help the interview partner to specifically explain their ideas. The goal of this type of interview is to better understand the motivations and