Registered nurses’ experiences of assessing

patients with mental illness in emergency

care: A qualitative descriptive study

Mats Holmberg

1,2,3,4, Staffan Hammarb

€ack

1,2,3,4and

Henrik Andersson

3,5,6Abstract

Patients with mental illness are exposed and experience themselves as not being taken seriously in emergency care. Registered nurses need to assess patients with mental illness from a holistic perspective comprising both a physical and an existential dimension. The aim of the study was to describe registered nurses’ (RNs) experiences of assessing patients with mental illness in emergency care. Twenty-eight RNs in prehospital and in-hospital emergency care were individually interviewed. The interviews were analysed descriptively. The design followed the COREQ-checklist. One main theme ‘A conditional patient assessment’ and two themes; ‘A challenged professional role’ and ‘A limited openness for the patient’, comprising in turn four sub-themes emerged. Although the RNs showed willingness to understand the mental illness aspects of their patients, they were insufficient in their assessments. This implies the importance of developing emergency care RNs’ competence, knowledge and self-confidence in assessments and care of patients with mental illness.

Keywords

assessments, caring, emergency departments, emergency medical services, mental illness, registered nurses

Accepted: 23 June 2020

Introduction

Mental illness is increasingly being presented as a global health problem.1,2In this article, the term mental illness is used as an umbrella term and comprises a spectrum from severe disorders/diseases and common mental health prob-lems to mild symptoms. Examples of mental illnesses are bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, anxiety, depression, sub-stance use disorder, self-harm and difficulty sleeping. The literature reports an increase of mental illness for all ages. From a national perspective the number of healthcare visits in Sweden in relation to mental illness has increased in the 10–14 year age group.3An increase is also reported in mental illness among both women and men in the older population (> 77 years) during the period 1992–2014 in Sweden.4 One study of a Swedish special psychiatric ambulance unit shows that their assignments represented all ages (5–100 years) and several different conditions; severe suicide threats (36%), suspicion of severe psychiat-ric illness (25%), acute crises (18%), severe suicide attempts (6%), suspicion of intoxication/overdose (3%) and other assignments (12%).5From an international per-spective, an Australian study shows that the number of emergency department presentations increased between 2004 and 2016 across most mental illness diagnostic groups, but particularly psychoactive substance use-related disorders.6 In addition, a US study showed that

the number of children visiting emergency care with mental health illness had risen by 60% between 2007 and 2016.7 Taken together, this provides a picture of mental illness increasing internationally for all ages and more spe-cifically, an increase in emergency care (EC) visits due to such conditions. In this article, EC refers to the care and treatment provided by registered nurses (RNs) in ambu-lance or emergency departments.

Mental illness are often presented together with somatic comorbidities, leading to an increased requirement for EC among those patients.8 This will also influence the

1Region S€ormland, Department of Ambulance Service, Katrineholm, Sweden 2Linnaeus University, Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, V€axj€o, Sweden 3Linnaeus University, Centre of Interprofessional Collaboration within Emergency care (CICE), V€axj€o, Sweden

4Centre for Clinical Research S€ormland, Uppsala University, Eskilstuna, Sweden

5University of Bora˚s, PreHospen – Centre for Prehospital Research, Bora˚s, Sweden

6University of Bora˚s, Faculty of Caring Science, Work Life and Social Welfare, Bora˚s, Sweden

Corresponding author:

Mats Holmberg, Ambulanssjukva˚rden, M€alarsjukhuset, 631 88 Eskilstuna, Sweden.

Email: mats.holmberg@regionsormland.se

2020, Vol. 40(3) 151–161 ! The Author(s) 2020 Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI: 10.1177/2057158520941753 journals.sagepub.com/home/njn

assessments, care and treatment provided in EC. Studies have shown that patients in EC found that their somatic symptoms were not always noticed because their mental illness became the focus.9–11 Patients with mental illness also experienced discrimination, emanating from not receiving the same care and treatment as patients without mental illness in EC.9,12Being a patient in EC is to have one’s self-determination reduced and to be exposed when dependent on the RNs.13,14In addition, studies report that stigma following mental illness may create a barrier to EC.15,16 This together provides an understanding of patients with mental illness in EC as exposed, especially when RNs demonstrate a lack of knowledge as well as showing a negative attitude towards patients with mental illness.17,18 In addition, nursing staff in somatic care are found, more often than nursing staff in mental health, to show a negative attitude towards patients with mental ill-ness, and to regard them as being more dangerous and unpredictable than other patients.5

Registered nurses with or without specialist education who work in EC (i.e. prehospital and in-hospital emergen-cy care), have the responsibility to assess patients with many different symptoms and conditions in order to clar-ify whether the patient’s physical condition, is stable or unstable and what the patient’s care needs are.19,20 This patient assessment requires mainly the medical compe-tence to introduce urgent and life-saving interven-tions.20–22This may define EC to be focused on patients’ urgent and emergency somatic biomedical needs. However, RNs are compelled to contribute to a qualitative assessment within EC and provide care from a wider per-spective.23,24 Nursing practice is a context-specific inter-personal process characterised as expert nursing practice, interpersonal sensitivity and intimate relationships.25 Nursing care seen from a caring science perspective corre-sponds to a person as whole and complete in the moment and may call for discovering the sometimes subtle expres-sions of caring activities.26Thus, patient assessment in EC is found to be more complex than merely biomedical issues, involving the RNs’ relationships with the patients.27,28 In those relationships the RN may create preconditions to support and strengthen patients’ health, alleviate their multifaceted suffering and respect their dig-nity.27,29,30Hence, patient assessment in EC is described as concerning issues not only included in objective protocols, but encompassing an existential view of the patient’s suf-fering and his/her lifeworld.31A study on RNs working in Swedish EC found them to have a primary biomedical focus in the assessment but also highlighted the unique encounter with the patient as the core of their care.24 This can be understood as preceded by the encountered patient’s physical, psychological, social and/or existential/ spiritual suffering, striving towards enhancing his/her well-being. Patient assessments in EC are described as compris-ing the objective data based on patients’ vital signs, chief complaints and medical history together with an assess-ment based on the patient’s subjective lifeworld.31This is described as both generating a more valid assessment and reducing the patient’s perceived suffering. However, RNs’

care of patients in EC is organised with a focus on protocol-based biomedical assessment and treatment, described as an obstacle to fully assessing the individual and the illness.31Thereto, triage systems are used as pro-tocols in EC to early identify and triage somatic critically ill patients.20 In addition, RNs in EC are found to have insufficient education, limited experience and to be uncer-tain in their assessment of patients with mental illness.17,32,33

The rationale for this study is based on the fact that EC has a primary focus on assessing and providing care for patients with somatic conditions. However, the numbers of patients with mental illness, as common care-seekers in EC, are increasing at all ages. Thus, this may generate a disproportionate assessment of patients with mental illness compared to other patient groups in EC due both to organisational factors and RNs’ competence. In addition, patients with mental illness experience discriminative care and not being taken seriously within EC. However, RNs need to be capable of assessing patients with mental illness from a comprehensive perspective in order to reduce the patient’s suffering as comprising both a physical and exis-tential dimension. This then takes account of both somatic and mental aspects of patients’ suffering. In this regard, studies on RNs’ perspectives of assessing patients with mental illness in EC is important. Such knowledge will further add to the existing knowledge of mental illness in EC as well as the professional role of being an RN in this setting.

Aim

The aim of the study was to describe RNs’ experiences of assessing patients with mental illness in EC.

Method

Design

In line with the aim, this study adopted an inductive descriptive design with face-to-face interviews. The study was performed in line with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist.34

Setting

The study was conducted in one region in eastern Sweden, covering approximately 5,600 square kilometres and 295,000 inhabitants (52 inhabitants/km2). The EC organi-sation in the region covers an ambulance department located at eight stations and three emergency departments, covering both rural and urban areas. In 2017 the ambu-lance department had approximately 35,000 assignments and the emergency departments approximately 93,000 visits in total. The ambulance or emergency departments had no specific mental health competence on duty within the organisation, such as psychiatrists, specialist trained psychiatry RNs or psychiatric ambulance units.

Participants

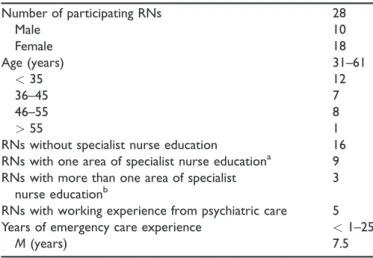

The participants were recruited at the region’s EC units by the second author. The inclusion criterion was: RN with or without specialist education. A purposeful sample35 was performed in order to achieve a variation in age, gender and experience as RN (Table 1). Contact details of RNs (N¼ 28) who met the inclusion criteria were provided by the first-line managers to the second author. Those RNs then received written email information about the study’s aim, procedures and ethical aspects of participation. Subsequently, they were asked by the second author whether they would consent to participate in the study. All 28 RNs gave their consent and were included in the study. The RNs worked in EC at the ambulance (n¼ 17) or at emergency departments (n¼ 11), were both women (n¼ 18) and men (n ¼ 10) and their age range was 31–61 years (M¼ 40). Their experience from EC departments varied between< 1–25 years (M ¼ 7.5) and five (18%) of the participants had working experience from psychiatric care.

Data collection

Data collection from open-ended individual interviews was conducted one to one during 2018 by the second author (SH) at the respondents’ workplaces. The interviews were moderated in order to encourage the participants to reflect upon their experiences of the phenomenon and introduced with the question; ‘Can you describe a situation involving a patient with mental illness, and how you handled the situation?’ Follow-up questions were posed where neces-sary to stimulate the RNs’ reflections over their experien-ces of assessing patients with mental illness such as; ‘You said you were lonely, what made you feel lonely in this situation?’ and/or ‘Why is this patient difficult to assess?’ The interviewer had experience from EC as an RN and that may have impacted the probing questions. The inter-view questions were pilot tested in the first interinter-views, with no amendments subsequently being necessary. Each inter-view was digitally recorded covering in total 700 minutes of data (M¼ 25 min/interview, ranging from 15 to 46 min). The verbatim transcriptions of the interviews were carried out in a careful manner so as not to alter the original data. The transcriptions were carried out by the second author together with an external transcriber.

Data analysis

The data analysis followed a qualitative descriptive method.36 The transcribed interviews were read through several times in order to get a sense of the whole. Subsequently, meaning units were extracted from the text, condensed, coded and merged thematically (Table 2).36 The relationships between sub-themes, themes and the main theme were then identified through constant comparison of meaning units and codes until they were judged not to overlap each other. While writing the results those relationships were made traceable and visible by using wording from sub-themes and themes in the

descriptions of the themes and main theme respectively. Quotations were used to clarify the sub-themes. When a slash /. . ./ appears within a quotation, a part has been left out, as those parts are not considered essential for the understanding of the text. The analysis was a process led by the first and last authors and was undertaken in Swedish and subsequently translated into English. All authors had preunderstandings based on clinical experien-ces from EC, which may have impacted the analysis pro-cess. However, in order to reduce the impact of preunderstanding and to ensure trustworthiness of the analysis and the eventual results, critical discussions and seminars were held between all authors and peers to address these issues. Finally, a professional language review was performed on the formulated themes as well as the manuscript as a whole.

Ethical considerations

The study was carried out in line with the Declaration of Helsinki37and the participants received verbal and written information about the study’s aim and procedures in advance. The ambulance and emergency department man-agers approved the study. Prior to the interviews the RNs had the opportunity to pose questions. The RNs were informed that participation was on a voluntary basis and that they could withdraw at any time without stating a reason. Finally, they signed a written informed consent. In the result, quotations have been labelled with partici-pant numbers in order to protect the RNs’ identities. This kind of research is regulated by Swedish Law38 and an advisory statement from the Regional Ethics Committee (Dnr. 2018/005) was obtained prior to starting the project.

Results

The results are expressed as one main theme ‘A condition-al patient assessment’. The main theme is underpinned by the themes ‘A challenged professional role’ and ‘A limited

Table 1. Socio-demographic and professional characteristics of the registered nurses (RNs). Number of participating RNs 28 Male 10 Female 18 Age (years) 31–61 < 35 12 36–45 7 46–55 8 > 55 1

RNs without specialist nurse education 16 RNs with one area of specialist nurse educationa 9 RNs with more than one area of specialist

nurse educationb

3 RNs with working experience from psychiatric care 5 Years of emergency care experience < 1–25

M (years) 7.5

aPrehospital, emergency, anaesthetic or infection care.bPrehospital care together with primary, intensive and/or anaesthetic care.

T able 2. Exampl e o f the analysis pr ocess. Meaning unit Condens ed meaning unit Co de Sub-theme Theme Main theme W e cannot for ce an yone. At the same time, yo u feel: ‘What if he d oes tak e mor e tablets then jumps off the balcon y?’ /.. ./ S o , it becomes /.. ./ a difficult situation (RN No . 2). Uns ur e o f how the pat ient will act but cann ot for ce him. Helpless ness A ques tioned responsibili ty A challenged professio nal role A condit ional patient assessme nt [I] ask ed her if she had an y contact with primar y car e earlier /.. ./ She had not been to an y emergency department after the traffic accident /.. ./ S o , [I] tried to explain to her that it does not sound lik e it is acute /.. ./ Rath er that she should pr obably seek primar y car e. /.. ./ Then w e had the w orst discuss ion ther e in the corridor . W e sat ther e in the corner and I tried to refer her to the primar y car e /.. ./ but she refused (RN No . 22). As the condition is not acute the RN tries to refer the patient to prima ry car e, but the patient refuses. Referr ed responsibility She doesn’ t talk. She follows us kindly to the ambulance, but she doesn’ t talk. Y o u tr y to talk to her . /... / I feel dejected. /.. ./ Y ou tr y to talk with her but it is not easy . (RN No . 17) The patient does not talk e ven if the RN tries to talk to her . N o t responding A willingness to reach the patient At the same tim e, yo u tr y to reach the patient. /.. ./I t w ent w ell fr om the beginning. When I talk ed to her in the emergenc y room she listene d and receiv ed the message. /.. ./ It w ork ed w ell. /.. ./ But then it appear ed as if she just turned off. (RN No . 20) The RN tries to reach the patient who sudden ly becomes unr eachable. Sud denly unr eachable RN: regis ter ed nurse.

openness for the patient’ and the adjoining sub-themes ‘A questioned responsibility’, ‘A willingness to reach the patient’, ‘Insecurity in patient encounters’ and ‘Insufficiency in the assessment’ (see Figure 1).

A conditional patient assessment

The respondents’ experiences of assessments of patients with mental illness was found to be complex. On the one hand, a professional responsibility was experienced with a willingness to reach the patients in the assessments. However, this responsibility was questioned from different perspectives. Thus, the respondents experienced an insuf-ficiency while assessing those patients. On the other hand, a conditional patient assessment was experienced with the respondents being on their guard, thus limiting the open-ness for the patient in the assessment and the performance of necessary nursing care interventions. In addition, the respondents experienced a lack of competence in assessing different kinds of mental illness, assumed that more could be done and wanted to hand over responsibility to some-one else. A conditional patient assessment was also founded on the fact that patients with mental illness were perceived as less interesting and given a lower priority compared with patients with emergency somatic conditions.

In the assessments some mental health conditions that were judged to endanger the patient existentially were taken seriously, while others were not taken as seriously. Hence, this affected the respondents’ empathy and patience in the assessments. One condition in the assess-ment was proper access to the patient’s lifeworld and sub-jective experience. In this regard, the respondents showed willingness to enter the patient’s subjective world, to understand him/her beyond the perspective of the mental illness. However, this was conditioned due to obstacles in gaining access to the patient’s subjective experiences.

A challenged professional role

The assessment was described as a challenged responsibil-ity while being forced to determine whether the patient suffered from either physical and/or mental illness. In this the willingness and need of reaching the patients were underlined as important in order to both assess the patient and alleviate his/her suffering. At the same time the need to categorise the patient’s condition as either a somatic or mental condition was stated as important in the assessments. In this, the assessment was conditioned by the lack of time adding to a questioned responsibility, while not having sufficient time to provide proper assess-ments. A genuine patient encounter was experienced as a certain important precondition for assessments of patients with mental ill health and thus required time. However, this was challenged by at times stressful working conditions.

A questioned responsibility. Professional responsibilities in the assessments were primarily addressed to patients with emergency somatic conditions. An important part of the assessment was to create an understanding of the patient’s condition and situation, in order to establish a clear pic-ture of what had happened. This was experienced as important for assessing whether the patient’s condition was due to somatic illness or mental illness and whether the mental illness affected the patient’s everyday wellbeing. However, it was described as a challenge to understand and trust the patients in this.

After all, it really becomes difficult knowing what is true or not true and what to believe or not believe. (RN No. 13)

The respondents’ primarily focus was to exclude any urgent somatic condition. Following this, the respondents expressed a need to refer the responsibility for mentally ill patients to other healthcare services, e.g. primary or psy-chiatric care. However, this opportunity was described as

limited due to the fact that critical somatic symptoms needed to be dismissed before the responsibility for the patients could be transferred.

You do not know if it is because of their mental illness they seek care /. . ./ They think they are in pain but maybe they are not in pain, so it is so difficult to assess /. . ./ when someone seeks care after six weeks because he has pain in the whole body, then it sounds very strange that you have not asked for primary care earlier. I think that is very difficult /. . ./ Why did they not seek primary care or the emergency department earlier? /. . ./ That is so difficult. Are they seeking help because they are in pain, really in pain, or do they want to hide in some way that they are mentally ill? (RN No. 22)

At the same time, there were examples of experiences from encounters with patients suffering from mental illness, leading to lost empathy and questioning of one’s respon-sibility. In this, the respondents described the negative influence of lost patience while assessing those patients. Following this, mentally ill patients were occasionally described as less interesting than patients with emergency somatic conditions.

My empathy disappears somewhat /. . ./ She is not very nice at all times to us /. . ./ You try to listen and you try to explain /. . ./ I lose my patience with such patients. (RN No. 14)

The respondents then felt helpless while assessing patients suffering from mental illness. Thus, this affected the respondents’ ability to create an understanding of the patient’s situation and to carry out a proper assessment with a patient subjective perspective as a starting point. A consequence of this was that the respondents questioned themselves and their professional role, seeing themselves as showing inadequate responsibility and care.

A willingness to reach the patient. Listening to the patient and thereby entering the patient’s ‘bubble’, was important in order to assess the patient’s mental health status and to create order in the perceived existential chaos of the patient. However, this was paradoxically challenging as the mental illness was described as an obstacle to reaching the patient in conversation.

The hard thing for me was probably to reach him, to try to get to him. You want to help, that’s my duty here in life. You want to care, you want to help and you want to sup-port and you want to fix everything that is broken and you can’t reach him. In his world his life was over. He didn’t want to live anymore, and this is a man who has toddlers and a child on the way /. . ./ It was difficult to get any contact with him. It was impossible. I did not manage, because he was not receptive. (RN No. 11)

Being reachable in conversation involved balance between being verbal or silent in order to obtain access to patients’

narratives. However, in the assessment a lack of answers to one’s questions created an obstacle as well as the percep-tion of not being able to enter the lifeworld of the patient.

She was not receptive, she was very shielded /. . ./ She was not receptive to any contact whatsoever, she was complete-ly in her own bubble. (RN No. 12)

At the same time, being a listener was experienced as essential in the patient conversation in order to assess the patient. On the other hand, taking control of the verbal part of the conversation was described as a part of the nursing care, diverting the patient’s focus from his/her symptoms or illness. However, a lack of knowledge regarding what one could or could not say to a patient with mental illness had a negative impact and reduced respondents’ confidence in the verbal conversation.

A limited openness for the patient

It was not always possible to reach the patients in the assessments when one’s preunderstanding limited the openness for the patient. This limited openness was under-pinned by an insecurity when encountering those patients, experiencing a threat to one’s own safety. There was then a risk that, for the patient, important aspects and time-critical conditions were neglected. Limited openness by not having access to the patient’s story made it necessary for the respondents to search for clues in alternative ways when the patient did not express his/her experiences of the illness. However, this also comprised an insufficiency in the assessments due to lack of knowledge and disturbing environments. In addition, there was a risk of being too personal with the patient hindering the respondents’ unprejudiced openness for the patient’s experienced suffering.

Insecurity in patient encounters. Interactions with mentally ill patients were described as unreliable. From time to time, when alone in the interaction with a patient it was experi-enced that the situation could quickly change and become insecure.

She sits quite half asleep on a kitchen chair. [seeing her through a window] /. . ./ There is a wine bottle on the bench and all that. On the kitchen counter there is a knife, the first problem was that, oh this was not the situ-ation we roughly expected based on the informsitu-ation [from the medical dispatch centre] /. . ./ We had to call the police to enter the patient’s home /. . ./ and for protection. /. . ./ Finally, she comes /. . ./ and opens. /. . ./ I started talking to her /. . ./ then she went quickly into the kitchen and the knife was still there. /. . ./ She was not about to grab it but in the heat of the moment you do not know what she is going to do. (RN No. 18)

Patients suffering from mental illness may be threatening or violent, creating a feeling of insecurity for the respond-ents. This meant that the respondents needed to deal with

both the patient’s and their own fears, and that it was necessary for the respondents to have situational aware-ness to assess the risk of threat and violence.

But she refuses. You try to approach her and talk about what to do. Then she kicks and beats and screams that you should not touch her. /. . ./ It ends with that four people may hold her and then I will be able to take the blood-sample /. . ./ It feels a bit like an outrage. (RN No. 15)

Hence, the respondents then needed to safeguard their own and others’ safety when the patient might behave threateningly or violently, having a negative impact on the openness in the patient assessment. At the same time, the insecurity was experienced as emanating from limited training in situational awareness, affecting the respond-ents’ ability to identify and assess patient safety risks. Insufficiency in the assessment. At times, the respondents felt their assessment was inadequate and assumed that more could be done. An ambition to take into account the patient’s subjective situation was expressed but was hin-dered by external factors such as language barriers.

We don’t know what she is talking about. /. . ./ We don’t even know if she spoke in her own language as well, she just mumbled and jabbered. /. . ./ I couldn’t see that it was any language at all. (RN No. 7)

Another aspect of this was that the respondents experi-enced time-pressure in short patient encounters, which meant that the assessment could not be carried out in a desirable manner. Hence, the respondents felt insufficiency when the assessed needs of the patient could not be cared for in a desirable manner.

It feels like this patient needs to have a calm and confident person who she trusts. /. . ./ We have a very short encounter with her. A very short time to create trust. Sometimes you succeed and sometimes you do not succeed. In my eyes it feels like /. . ./ What she needs is almost a couple of open arms and a confident person who can be receptive and tell her that ‘I see how you feel and I see that you not are feeling well’. (RN No. 8)

Sometimes there are disturbing surroundings affecting the assessment of the patient. This could be other present pro-fessions (e.g. police officers and/or fire fighters) at an ambulance assignment or an over-crowded emergency department. The respondents experienced a responsibility for the patient, which required competence to carry out a proper and solid assessment. At the same time, the respondents described that at times they experienced that those assessments were inadequately carried out. This inadequacy was based on the fact that the respondents did not always know or have insight into how to deal with patients suffering from mental illness. Patients who expressed their disinterest in receiving care also increased the respondents’ feeling of inadequacy. The respondents

highlighted limited theoretical knowledge of mental illness and lack of professional experience as limiting factors in their assessments. This in turn affected their ability to handle any difficulties that arose in connection with the assessments.

Discussion

In the present results, RNs experienced a conditional patient assessment, a challenged professional role and a limited openness for the patient while assessing patients with mental illness. This result is found to be paradoxical and may present an RN’s profession as multifaceted in EC. The RNs in the present results appear to be both willing and unwilling to assess and provide care to patients with mental illness. This is rather interesting as it might provide a picture of the RNs as insecure in their profes-sional role and responsibility in EC. This may be under-stood from different perspectives. Firstly, the RNs’ responsibility may see them as being entrenched within the biomedically focused EC setting, and understanding mental illness as something that cannot be handled by the care provided,39 nor it being their responsibility. This may also cause RNs to be apprehensive of their profes-sional role and responsibility and may form a culture in which patients with mental illness are not seen as a prima-ry responsibility within EC. In the present results this is described in the main theme as a conditional patient assessment. The risk is, however, that this understanding among RNs elucidates only the technical aspects (e.g. the performance of advance urgent medical care and/or resus-citation) of the RNs’ profession in EC. However, open-heartedness as a humanising face of procedural, instrumental, or technical knowledge is underlined as sig-nificant in nursing.40 Paradoxically, the RNs’ willingness to reach the unique patient’s lifeworld, as well their feeling of inadequacy in the assessments, corresponds to open-heartedness in nursing. Thus, the findings suggest that RNs are divided between different aspects of their profes-sional role when it comes to the assessments of patients with mental illness. This might be problematic as care-seekers in EC comprise a variety of different urgent and non-urgent conditions. Following this the need to provide a holistic EC has been stated earlier,22 and is relevant because patients with mental illness are common care-seekers in the EC. In this regard, patients’ experiences of specialist psychiatric EC units are found to contribute to a care without fear of being dismissed, ignored and judged.41 Summarised, the need to develop and expand the RNs’ understanding of the holistic aspects of their professional role is important and should be taken into account in when arranging EC. This is especially so when the care of people with mental illness in emergency departments may increase6,7 and be adversely affected by diagnostic overshadowing and avoidance by clinical staff.42

The present findings describe a limited openness towards patients with mental illness, in the RNs’ assess-ments. Patients with mental illness are described as less interesting compared to patients with emergency somatic

conditions and the RNs felt inadequate and had a limited amount of time to properly assess them. Thereto, the RNs needed to safeguard both their own and others’ safety while being insecure in the patient encounter. This togeth-er with a need to categorise the patient’s condition as either a somatic or mental condition impends a holistic assessment that originates from the patient’s subjective lifeworld. In this regard, the importance of caring assess-ments is underlined.31 Caring should then take the patient’s lived experiences into account in order to provide a nursing care that enhances his/her health.43 This is founded on the understanding of health as not analogous with the absence of illness.29In this regard, the RNs’ chal-lenged professional role may refer to the ethical aspect of encountering the patient as someone who can trust the RN. As humans we share each other’s worlds, and thus become responsible for each other’s trust as an ethical demand.44 RNs may experience a complex contradiction in their professional role, as a willingness to reach a patient that is not perceived as interesting compared with others. The ultimate aim of caring in professional nursing is described as preserving the patient’s dignity, absolute value as a human being and his/her right to self-determ-niation.45However, in the same review report, RNs expe-rience an inability to provide the care that preserves those values and thus risk burnout and drop-out from the pro-fession. This corresponds to the present result of a dicho-tomised rather than a holistic understanding of the RNs’ professional role in the assessments, excluding a caring perspective. This dichotomy is found in an earlier study on ambulance RNs’ experiences of the patient relationship in emergency and urgent assignments, as an inability to simultaneously provide advanced medical care and enter a trustful patient relationship.46With the aim of providing a holistic assessment and reaching the mentally ill patient this is problematic, and underscores the need for combin-ing the biomedical perspective with a lifeworld perspective on the patient in EC. This is also supported by earlier studies that underline the importance of establishing a pro-fessional/personal balance in the patient relationship.47,48 At the same time, the RNs in the present study show a willingness to take into account the patient’s subjective lifeworld but were hindered by several external factors, such as over-crowded emergency departments. Hence, holistic assessment in EC is not only related to the indi-vidual RN but influenced by e.g. hectic surroundings, time pressure and the patient’s condition. Following this, the responsibility for creating preconditions for providing holistic assessments lies both on the individual RN, his/ her training and the EC organisation.

In the present results the RNs describe occasionally a disinterest in and inadequacy to assess patients with mental illness in EC, e.g. due to insecurity in the patient encounter, lost empathy and lack of time. Emergency departments’ ambition to shorten patient time is found to force clinicians to decide whether the patient’s problems are somatic or mental before they were ready to do so.42 This, together with an inadequate assessment as in the present results, corresponds to trust as a core component

in the relationship between the RN and the patient. Providing care for patients in EC is described as being founded on the patients’ trust, in both the organisation and the RNs as professionals.13,14 Following that, being trustworthy as an RN is important not only as a response to the individual patient, but also because it may add to a general perception of the trustworthiness of nursing as an institution.49 However, based on the present result this may be impaired, e.g. due to the RNs occasionally losing empathy with mentally ill patients. In addition, trust may be impaired in patients with mental health illness as an effect of their illness.50 However, earlier findings describe patients in EC as handing over their responsibility to the professionals.51 The RNs hold a specific knowledge that the patients need. In the present results the RNs experi-enced a lack of knowledge in assessing patients with mental illness, leading to a feeling of inadequacy. The lack of knowledge and practical training related to mental illness in EC is found to cause discomfort among the clinicians when assessing and providing care.42Hence, the RNs in the present results may not hold the profes-sional knowledge that the patients expect, thus harming patients’ trust. The patients then might feel that they are given an inadequate assessment and that their suffering might not be alleviated. This may promote the risk that mentally ill patients experience not being taken serious-ly,9,12 adding this to their earlier perceived suffering, labelled as a suffering related to care.30 In the present results the RNs describe a conditional patient assessment related to factors such as lack of competence in assessing different kinds of mental illness, assuming that more can be done and a desire to refer responsibility to someone else. In addition, studies show that patients in EC with mental illness experience discriminatory and unequal care.9,12This might, in the light of the present results, con-tribute to a risk of a mentally ill patient suffering related to care within EC, violating their dignity.30An earlier study on RN students in EC found that preserved dignity was described as being there for the patient in the patient’s reality.52 Experiencing a lack of knowledge and a desire to hand over the responsibility, as in the present results, might therefore reduce the ability to be there for the patient in his/her reality, especially when the openness for the patient is limited. This together calls for highlight-ing trust as an essential part within assessments of patients in the EC. However, this may not only be related to the patient’s trust in the RN but to the RN’s trust in the patient.

Finally, at the same time the RNs showed a willingness to assess the patient with his/her lifeworld as a foundation, although with limited openness. They were found to be ‘detectives’ in their search for clues when the patient did not explicitly express his/her experiences of the illness. This may contradict the understanding of the RNs’ assessments as being influenced by a disinterest in mental illness and may prevent the patient’s suffering related to care.30In this regard a caring assessment based on the patients’ life-worlds is found to be important.31This requires openness to the situation and sensitivity to the patients’ suffering,

not solely focused on biomedical conditions and diagnosis. In the present result the RNs may be understood as having the willingness to take this into account, but occasionally fail due to several factors. This underlines the importance of developing RNs’ competence, knowledge and self-confidence in assessing and care for patient with mental illness in the EC. Summarised, holistic assessment in EC is important and needs to be facilitated both in RNs’ com-petence development and in EC organisations. This together calls for future research and interventions in order to improve the care of patients with mental illness from a holistic perspective.

Methodological considerations

In order to ensure trustworthiness; credibility, dependabil-ity, confirmability and transferability were taken into account throughout the study.53 One strength of this study is the rather large amount of qualitative interview data. This was judged to contribute to a wide variation of RNs’ experiences sufficient for the following analysis.

In order to contribute to the trustworthiness of the study the ambition with the analysis was in line with the aim to inductively describe patterns in the data.36The first and third authors together analysed data in an ongoing discussion until consensus was reached and sub-themes and themes emerged. In order to further ensure credibility, their analysis was subject to critical seminars involving all authors and peers not involved in the specific study. Following those seminars amendments were made, such as the labelling of sub-themes and themes. Dependability was taken into account by returning to the transcribed interviews with the labelled themes in order to ensure an inductive description to reduce the impact of the authors’ preunderstanding. Despite this ambition the impact of dif-ferent preunderstandings and interpretations is unavoid-able. However, in line with the method the ambition has been to re-present data in their own terms and interpreta-tion has not been used explicitly.36To ensure confirmabil-ity, the labelled themes have been exemplified with several quotations from the transcribed interviews while reporting data. In addition, in order to ensure confirmability of the results, the quotations were retrieved from several different respondents’ interviews. The transferability of the results may be considered through the authors’ efforts to describe in detail the participants, context, data collection and anal-ysis as carefully as possible. However, in order to transfer the findings to other settings they need to be de-contextualised following the authors’ efforts to describe the participants and context as thoroughly as possible.

A limitation of this study may be the rather wide under-standing of the concept ‘mental illness’. On the one hand this corresponds to the everyday work in EC. The RNs encounter a wide variety of patients with different condi-tions and have to assess them in order to define a proper level of care. On the other hand, a more limited under-standing of mental illness (such as specific medical diagno-sis) may probe the RNs’ reflections of a more specific character. However, the wider concept was judged to be

appropriate to elucidate the RNs’ experiences from a wider perspective, in order to subsequently serve as foun-dation for upcoming studies and interventions.

Conclusions

Based on this study the following conclusions are relevant for both nursing education and clinical EC. Firstly, RNs in EC need increased training and knowledge in assessing mentally ill patients both during their nurse education and as part of continuous professional development. Secondly, there is a need to develop interventions within EC that reduces the RNs’ feeling of being insecure in the assessments of patients with mental illness and thus pro-motes trustful relationships. Thirdly, the caring environ-ment has to be taken into account when organising EC in order to establish circumstances where trustful relation-ships are not disturbed when RNs are assessing mentally ill patients. Finally, RNs in EC need to be strengthened in the understanding of their professional role as a holistic practice and how different professional aspects can be combined rather than dichotomised. Taken together, based on the descriptive aim of this study upcoming stud-ies have to focus on interventions based on the conclusions above, in order to gain knowledge on how to improve RNs’ assessments of patients with mental illness. Future research projects could be based on an ambition to devel-op models for simulation of assessing mentally ill patients, in order to provide a comprehensive RN understanding of patient assessments in EC. Such models could benefit both nursing education and practice.

Acknowledgements

We want to express our most sincere thanks to all the RNs who shared their experiences of assessing patients with mental illness in EC. We would also like to sincerely thank Anders Wetell Jonsson (RN, BSc) and Hanna Johansson (RN, BSc) for their contribution to the study design and data collection.

Author contributions

MH, SH and HA: study design. SH: data collection. MH and HA: data analysis and preparing the manuscript. All authors took part in critical revision, rewriting and approval of the final manuscript.

Funding

The study was financially supported by Centre for Clinical Research S€ormland, The Swedish Society of Nursing together with Fredrik and Ingrid Thuring’s foundation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

ORCID iDs

Mats Holmberg https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1878-0992 Henrik Andersson https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3308-7304

Supplemental material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

1. World Health Organization. Mental health action plan 2013– 2020. Geneva: WHO. https://www.who.int/mental_health/ action_plan_2013/bw_version.pdf?ua=1 (2013, accessed 8 July 2020).

2. Potrebny T, Wiium N and Moss-Iversen Lundeg ˚ard M. Temporal trends in adolescents’ self-reported psychosomatic health complaints from 1980–2016: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0188374.

3. The National Board of Health and Welfare. Tillst ˚andet och utvecklingen inom h€also- och sjukv˚ard och socialtj€anst [The state and development of healthcare and social services], https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-doku ment/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2019-3-2.pdf (2012, accessed 8 July 2020).

4. Public Health Agency, Aging Research Center. Skillnader i psykisk oh€alsa bland €aldre personer: en genomg˚ang av veten-skaplig litteratur samt en epidemiologisk studie [Differences in mental health among older persons: a review of scientific liter-ature and an epistemological study]. Stockholm: Public Health Agency, Aging Research Center. https://www.folkh alsomyndigheten.se/contentassets/85e04b9f6cde4e8daa2894 d389ade1ad/skillnader-psykisk-ohalsa-aldre-personer.pdf (2019, accessed 8 July 2020).

5. Bj€orkman T, Angelman T and J€onsson M. Attitudes towards people with mental illness: a cross-sectional study among nursing staff in psychiatric and somatic care. Scand J Caring Sci2008; 22: 170–177.

6. Tran QN, Lambeth LG, Sanderson K, et al. Trend of emergency department presentations with a mental health diagnosis in Australia by diagnostic group, 2004–05 to 2016–17. EMA - Emerg Med Australas 2020; 32: 190–201.

7. Lo CB, Bridge JA, Shi J, et al. Children’s mental health emergency department visits: 2007–2016. Pediatrics 2020; 145: e20191536.

8. Gervaix J, Haour G, Michel M, et al. Impact of mental ill-ness on care for somatic comorbidities in France: a nation-wide hospital-based observational study. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci2019; 28: 495–507.

9. Clarke DE, Dusome D and Hughes L. Emergency depart-ment from the depart-mental health client’s perspective: feature arti-cle. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2007; 16: 126–131.

10. Happell B, Ewart SB, Bocking J, et al. ‘That red flag on your file’: misinterpreting physical symptoms as mental illness. J Clin Nurs2016; 25: 2933–2942.

11. McCabe MP and Leas L. A qualitative study of primary health care access, barriers and satisfaction among people with mental illness. Psychol Health Med 2008; 13: 303–312. 12. Harangozo J, Reneses B, Brohan E, et al. Stigma and

dis-crimination against people with schizophrenia related to medical services. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2014; 60: 359–366. 13. Holmberg M, Forslund K, Wahlberg AC, et al. To surrender

in dependence of another: the relationship with the ambu-lance clinicians as experienced by patients. Scand J Caring Sci2014; 28: 544–551.

14. Rantala A, Ekwall A, Forsberg A. The meaning of being triaged to non-emergency ambulance care as experienced by patients. Int Emerg Nurs 2016; 25: 65–70.

15. Crowe A, Averett P, Glass JS, et al. Mental health stigma: personal and cultural impacts on attitudes. J Couns Pract 2016; 7: 97–119.

16. Knaak S, Mantler E and Szeto A. Mental illness-related stigma in healthcare. Healthc Manag Forum 2017; 30: 111–116. 17. McCann TV, Savic M, Ferguson N, et al. Paramedics’ per-ceptions of their scope of practice in caring for patients with non-medical emergency-related mental health and/or alcohol and other drug problems: a qualitative study. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0208391.

18. Rayner G, Blackburn J, Edward K, et al. Emergency depart-ment nurse’s attitudes towards patients who self-harm: a meta-analysis. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2019; 28: 40–53. 19. Dalton AL, Limmer D, Mistovich JJ, et al. Advanced medical

life support: a practical approach to adult medical emergencies. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2007. 20. Widgren BR and Jourak M. Medical Emergency Triage and

Treatment System (METTS): a new protocol in primary triage and secondary priority decision in emergency medi-cine. J Emerg Med 2011; 40: 623–8.

21. Wihlborg J, Edgren G, Johansson A, et al. The desired com-petence of the Swedish ambulance nurse according to the professionals: a Delphi study. Int Emerg Nurs 2014; 22: 127–133.

22. Andersson H, Jakobsson E, Fur ˚aker C, et al. The everyday work at a Swedish emergency department: the practitioners’ perspective. Int Emerg Nurs 2012; 20: 58–68.

23. Melby V and Ryan A. Caring for older people in prehospital emergency care: can nurses make a difference? J Clin Nurs 2005; 14: 1141–1150.

24. Holmberg M and Fagerberg I. The encounter with the unknown: nurses’ lived experiences of their responsibility for the care of the patient in the Swedish ambulance service. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being2010; 5: 1–9.

25. Finfgeld-Connett D. Meta-synthesis of caring in nursing. J Clin Nurs2008; 17: 196–204.

26. Boykin A and Schoenhofer S. Transforming practice using a caring-based nursing model. Nurs Adm Q 2003; 27: 223–230. 27. Watson J. Nursing: the philosophy and sciences of caring.

Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 2008.

28. Travelbee J. Interpersonal aspects of nursing. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Co, 1971.

29. Dahlberg K and Segesten K. H€alsa och v˚ardande. I teori och praxis [Health and caring. In theory and practice]. Stockholm: Natur och kultur, 2010.

30. Eriksson K. The suffering human being. Chicago, IL: Nordic Studies Press, 2006.

31. Wireklint Sundstr€om B and Dahlberg K. Caring assessment in the Swedish ambulance services relieves suffering and ena-bles safe decisions. Int Emerg Nurs 2011; 19: 113–119. 32. Sj€olin H, Lindstr€om V, Hult H, et al. What an ambulance

nurse needs to know: a content analysis of curricula in the specialist nursing programme in prehospital emergency care. Int Emerg Nurs2015; 23: 127–132.

33. Clarke DE, Boyce-Gaudreau K, Sanderson A, et al. ED triage decision-making with mental health presentations: a ‘think aloud’ study. J Emerg Nurs 2015; 41: 496–502. 34. Tong A, Sainsbury P and Craig J. Consolidated criteria for

reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Heal Care 2007; 19: 349–357.

35. Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd ed. Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2002.

36. Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative descrip-tion? Res Nurs Health 2000; 23: 334–340.

37. The World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: eth-ical principles for medeth-ical research involving human subjects, https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-h elsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-h uman-subjects/ (2013, accessed 8 July 2020).

38. SFS 2003:460. Lag om etikpr€ovning av forskning som avser m€anniskor [Swedish law regarding research involving humans]. Stockholm: Sveriges Riksdag. https://www.riksda- gen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattnings- samling/lag-2003460-om-etikprovning-av-forskning-som_sfs-2003-460 (accessed 8 July 2020).

39. Marynowski-Traczyk D, Moxham L and Broadbent M. Emergency department registered nurses’ conceptualisation of recovery for people experiencing mental illness. Australas Emerg Nurs J2017; 20: 75–81.

40. Galvin KT and Todres L. Embodying nursing openhearted-ness: an existential perspective. J Holist Nurs 2009; 27: 141–149.

41. Lindstr€om V, Sturesson L and Carlborg A. Patients’ experi-ences of the caring encounter with the psychiatric emergency response team in the emergency medical service: a qualitative interview study. Heal Expect 2020; 23: 442–449.

42. van Nieuwenhuizen A, Henderson C, Kassam A, et al. Emergency department staff views and experiences on diag-nostic overshadowing related to people with mental illness. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci2013; 22: 255–262.

43. H€orberg U, Ozolins L-L, Ekebergh M. Intertwining caring science, caring practice and caring education from a lifeworld

perspective-two contextual examples. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being2011; 6: 1–6.

44. Løgstrup KE. The ethical demand. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1997.

45. Rundqvist E, Sivonen K and Delmar C. Sources of caring in professional nursing: a review of current nursing literature. Int J Hum Caring2011; 15: 36–43.

46. Svensson C, Bremer A and Holmberg M. Ambulance nurses’ experiences of patient relationships in urgent and emergency situations: a qualitative exploration. Clin Ethics 2019; 14: 70–79.

47. Joolaee S, Joolaei A, Tschudin V, et al. Caring relationship: the core component of patients’ rights practice as experienced by patients and their companions. J Med Etics Hist Med 2010; 3: 1–7.

48. Holmberg M, Wahlberg AC, Fagerberg I, et al. Ambulance clinicians’ experiences of relationships with patients and sig-nificant others. Nurs Crit Care 2016; 21: e16–e23.

49. Sellman D. The importance of being trustworthy. Nurs Ethics2006; 13: 105–115.

50. Gewurtz RE, Lahey P, Cook K, et al. Fear and distrust within the Canadian welfare system: experiences of people with mental illness. J Disabil Policy Stud 2019; 29: 216–225.

51. Ahl C and Nystr€om M. To handle the unexpected: the mean-ing of carmean-ing in pre-hospital emergency care. Int Emerg Nurs 2012; 20: 33–41.

52. Abelsson A and Lindwall L. What is dignity in prehospital emergency care? Nurs Ethics 2017; 24: 268–278.

53. Streubert HJ and Carpenter DR. Qualitative research in nurs-ing. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011.