Page 1 of 66

SENSE OF BELONGING AND CONNECTEDNESS IN THE

ONLINE ESPERANTO COMMUNITIES

Iliyana Parashkevova

Media and Communications Studies (One-year Master)

15 Credits

Spring 2018

Page 2 of 66 Abstract

The thesis is focused on researching the recent phenomena of the emerging virtual Esperanto communities. The aim is to understand how feeling of belonging and connectedness are generated online. The theoretical framework that the study follows is Sense of Community theory by McMillan and Chavis (1986). It presents 4 components that combined together create a strong bond within a community – membership, influence, shared emotional value, and reinforcement of needs, later revised to spirit, trust, art and trade respectively. This particular theory helped significantly structure the way the analysis was carried out.

The main results from the qualitative and quantitative data are that the sense of connectedness the respondents demonstrated to the Esperanto communities was strong. The interview participants have been members for more than 10 years, and have indicated they believed they shared similar values and needs with their co-members, but most strong ones with the groups they shared other interests except Esperanto. The Internet, as all interview participants confirmed, has played a huge role for the development of the Esperanto language and culture and currently connects thousands of Esperantists worldwide and provides them with a space to be producers of their media, Esperanto. Furthermore, some statements demonstrated that not speaking the language results in excluding people from the group, excluding also new members who used auxiliary languages (e.g. English or German) along with Esperanto, to help their communication at Esperanto gatherings. Finally, there were also found signs of segregation among an older generation of Esperantists, who made division between Esperanto speakers and non-speakers and between the different Esperanto institutions.

Keywords: Esperanto, Esperantist, Esperanto communities, sense of belonging, sense of community,

TEJO, UEA.

Page 3 of 66

Contents

1. Introduction ... 4

1.1 Context ... 5

1.2 Personal Motivation ... 8

2. Literature and Theoretical Framework ... 8

2.1 The First Esperanto Communities ... 10

2.2 The Esperanto Associations in the Past ... 10

2.3 Sense of Belonging and Connectedness in a Community ... 11

2.4 Online Communities ... 12

2.5 Classification of Community Members (fans) ... 14

2.6 Sense of Community theory ... 17

2.7 Social Identity Theory ... 19

2.8 Cultural Capital ... 21

3. Data and methodology ... 23

3.1 Methodology ... 23

3.2 Interviews and data sets ... 24

3.3 Extract from survey data ... 26

3.4 Digital ethnography ... 27

3.5 Ethical Consideration ... 27

3.6 Limitations of the Study ... 29

4. Findings and Analysis ... 30

4.1 Esperanto Facebook group and interviews ... 30

4.1.1 The Internet as a tool for community creation and development ... 34

4.2 Spirit & Membership ... 36

4.2.1 Boundaries and Exclusiveness – Us vs. Them ... 38

4.3 Integration and fulfilment of needs ... 42

4.4 Influence ... 44

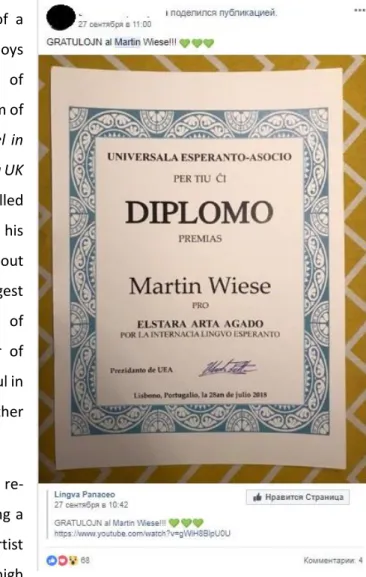

4.5 Trade & Reinforcement of Needs ... 45

4.6 The collective heritage ... 47

4.7 The continuum of the Esperanto fandom ... 48

5. Concluding discussion ... 53

5.1 Research implications and need for further investigations ... 55

Page 4 of 66

1. Introduction

The focus of this thesis is to understand if Esperantists demonstrate any sense of belonging and connectedness in the Facebook group Esperanto in which they form part of, and if yes - how is it generated and what is the role of the internet for the existence of these communities?

The Esperanto communities and language have grown significantly for the past 5 years with the rise of the Internet (Salisbury, 2017), where all kinds of people are given the chance to participate in Esperanto communities online. A big number of global and local gatherings and congresses are being organized every year and it becomes easier than ever to find and join a local community nearby if one desires to learn the language or simply belong to ‘something exclusive’, as Esperantists describe their communities. The little that is known today regarding the Esperanto communities makes them interesting to research from a sociological and media studies perspective for how a community is being virtually born and developed and Esperanto culture re-created an revived with the help of the Internet. This makes this media audience part of the consumer culture which uses the Internet to help its growth.

There are two very important organizations for the Esperantists - the Universal Esperanto Association (UEA) and the World Youth Esperanto Organisation (TEJO), which are also the oldest ones. Soon after its establishment, TEJO becomes the youth organization of UEA. Both organizations include smaller sub-communities, which are present both online and offline, as well as some independent local associations. These two organizations hold the biggest Esperanto congresses ever since their establishment, in 1908 and 1938 respectively. TEJO’s distinctiveness lies in its free lodging service exclusive to Esperantists, called Pasporta Servo, or PS. This service allows Esperantists to travel worldwide for free and be hosted by other Esperantists. The only condition is to speak well Esperanto. The purpose of this thesis is to be the first study on sense of belonging within the Esperanto online communities. Furthermore, the role of the Internet in relation to the development of the Esperanto culture and identity is also investigated with the help of 3 interviewees. Finally, it should be also mentioned that Esperanto is one of the very few languages created for peace and it is the most successful artificially constructed language to learn. It was argued that studying Esperanto does not bring the same reward as studying a language valued on the market. Therefore, examining people who learn such artificial languages can contribute immensely on what we already know about community behaviour and motivation.

Page 5 of 66

1.1 Context

Esperanto is an artificially constructed language developed by the Polish-Jewish doctor Ludwig L. Zamenhof in 1887. Its purpose was to work as an auxiliary language across countries and to bring peace and comprehension. The language after its creation in 19th century started to develop rapidly – many communities formed, and they started learning and disseminating the language all around the world.

However, around the Second World War and after Nazi’s rise, Esperanto communities’ development is impaired by oppression from Nazi regime as they perceived the movement as a threat due to its Jewish roots. The language was then officially banned in Germany from 1936 until 1956, followed by a ban in the Soviet Union, while Esperantists were targeted and executed by the Nazis (Harlow, 1993). Mentions of Esperanto are also found in Hitler’s book ‘Mein Kampf’, where he defines it as the language of the Jewish conspiracy (1925).

What we observe recently is the significant rise and revival of the language with the help of the Internet, where Esperanto enthusiasts all around the world gather and use the Internet as a tool to create countless online Esperanto communities and culture as never observed before. The community members are presented in this paper as media audiences, who create culture virtually of a language that had almost none 70 years ago. The Esperanto media audiences use now Internet as a virtual place to gather and share their Esperanto passion, by offering and spreading hundreds of online sources where one can study the language and being able to spread quickly information about upcoming real-life events and meetings. I have also described the Esperanto community as fans, for how similar this media audience is to fans’ or fanatic behaviour – similar for how much time members spend consuming and sharing about Esperanto, for how they behave in group, the linguistic code they use incomprehensible for outsiders, the boundaries they create, and for how defensive members are about their language and culture. What makes this audience interesting for media studies to investigate is how this media audience revives a forgotten language with the help of a medium, the Internet, creating stronger than ever culture by uniting hundreds of speakers worldwide. I chose specifically Facebook as the focus of the study as it is the most popular social network for members to connect and the fastest way to spread information in between, and in that sense this specific group it represents members in their natural habitat for having more than 22.000 members and on average 15 publications a day. Publications are made only in Esperanto and the content includes heavily music, art and literature in Esperanto, political and social discussions, information and news translated in Esperanto as one of the biggest categories. This FB group Esperanto is where the Esperanto culture is created and spread as much as possible.

Page 6 of 66 A very interesting aspect of being a part of the Esperanto community is Pasporta Servo, established in the 70s and owned by TEJO. Pasporta Servo is a portal for free lodging for Esperanto speakers all around the world, similar to Couchsurfing. It is a non-profit organization with the idea of networking and removing cultural barriers exclusive for Esperantists. The distinctiveness part that makes this service interesting to investigate within the community is its high level of hospitality. The purpose is to connect Esperantists for language exchange. The only requirement to participate is to speak Esperanto with the hosts on a comprehensible level, and to buy a small booklet published by TEJO (the World Esperanto Youth Organization) that contains all addresses of Esperanto hosts around the world.

The groupings of Esperanto are sometimes referred to as either the Esperanto movement or the

Esperanto communities (Forster, 1982). However, while communities have usually a goal to learn a

skill (or a language) on a smaller scale achieved within a community, a movement is characterized by trying to achieve this same goal while mobilizing a larger scale of people to bring a desired social impact.

Fig. 1. Movement vs. Community Source: Atkin (2012)

Atkin (2012) depicts the difference between these two definitions by pointing that a benefit for community members is the generation of sense of belonging in comparison to power for the members of movements. Relating these concepts to the literature review, the concept of movement is present much more often in writings of Esperanto in the past than it is now. As a reference, Forster describes the Esperantists as a movement not only in the presented researches of his book, but also in the title of the book itself The Esperanto movement (1982). Janton (1993) on the other hand uses instead the

Page 7 of 66 concept of communities and belonging. This is also highlighted as well in the most recent studies by Burghelea (2016) and Nielsen (2017a, 2017b), where light is brought to hospitality and belonging. Thus, when referring to movement in this thesis, I am referring to the initial Esperanto groupings in the last century, and to the groupings today as communities, which was suggested by the most recent academic sources.

To sum up, the purpose of this study was to examine if there was any sense of belonging in the Esperanto communities, as displayed by a Facebook group, the interview participants, and questionnaire respondents, how it is generated and represented.

As such, the main questions guiding the study are the following:

1. Is there any demonstrated bond and connectedness by members of the Facebook group

Esperanto? If yes, how is it expressed?

2. What is the role of the Internet in developing the Esperanto language, culture and bond between members in the Facebook group Esperanto?

Definition of terms

- Esperantist – A person who speaks Esperanto and uses it actively for any purpose.

- Esperanto communities/groupings – In this thesis, the term Esperanto community is used to name Esperanto speakers, forming part of a community, whose idea and effort is to spread the Esperanto language neutrally worldwide while striving for neutrality and usage along with other languages, instead of its domination over them.

- Tutmonda Esperantista Junulara Organizo (TEJO) – World Esperanto Youth Organization, established in 1938.

- Pasporta Servo (PS) – Free lodging network for Esperantists worldwide. In exchange, guests are supposed to speak Esperanto with their hosts. Established in 1966.

Page 8 of 66 - Universala Esperanto-Asocio (UEA) – Universal Esperanto Organization – the oldest and

biggest Esperanto association, established in 1908.

- Universala Kongreso (UK) – International Esperanto Congress.

1.2 Personal Motivation

My personal drive is that I am very passionate about languages, and have been part of several virtual polyglot communities for a while, some of which with more than 32.000 members1. I noticed that recently polyglots look more often for Esperanto speakers on these polyglot groups, and form discussions about the language and how useful it is to study an artificially created language.

Researching a bit Esperanto’s development throughout the years since its creation made me see it as a very interesting phenomena to look into from media studies perspective, taking into consideration that 80 years ago during WWII and Cold War periods it was a banned persecuted language. But with the rise of the internet, more people are becoming interested in learning Esperanto and becoming part of the communities. Therefore, I decided to devote this thesis and time to the Esperanto communities, to understand if there is any existing sense of belonging as demonstrated by members on the Facebook group Esperanto and as explained by interviewees.

2. Literature and Theoretical Framework

The literature in the field has been generally focused on Esperanto as a language from a linguistic point of view, and less on the communities from the perspective of sociology and media studies. The review begins with a history of the rise of Esperanto communities in the 20th century to provide the reader with insight on the background of these groups, how they emerged and how they were managed a century ago.

The majority of studies are significantly old, although there are scholars such as Burghelea (2016), who have recently researched cosmopolitanism and hospitality in Esperanto communities, presenting short but interesting findings about the culture in these communities. In addition, the Danish scholar

1 Polyglot group on Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/groups/polygotcommunity/?fb_dtsg_ag=AdxshTELQcEDR_HUUSLur7DOx1Tcti8fd eqfrL9hbvSMYA%3AAdwI0rHBLgsTf3SyZsI3eyLMBzy0FaMjnGxhqa2CoJygmQ (accessed: 04/09/18)

Page 9 of 66 Svend Nielsen (2017b), presents density of Esperanto speakers by variables such as location, contribution to science, culture and health, linguistic diversity, GDP, and others, which in a sense draws a demographic profile of the modern Esperantists.

One of the most prominent books on Esperanto, The Esperanto movement (Forster, 1982), also contributes to the review, as it is the first and one of the very few books on Esperanto with a sociological reference. Pierre Janton later introduces Language, Literature and Community (1993) that has a deeper research not only on Esperanto as a language, but also on the development of the Esperanto communities in the 1990’s. Another scholar used for reference is Rasic (1994), a Croatian sociolinguist, whose work is extremely valuable for this field. Rasic publishes a book with ten studies on different groups focused on countries such as Bulgaria, Finland and German Democratic Republic, and researching Esperanto speakers for a period of more than sixty years. His purpose is to understand these groups’ usage of the language, look for patterns and create a demographic profile of Esperanto members in terms of multilingualism and education.

The presented sources so far demonstrate the limited research in this field, and the need for new studies on the sense of belonging and connectedness of the Esperanto communities that this paper is focused on. The Esperanto communities are atypical and newly revived, which itself might be the reason for the lack of thorough and present investigations.

Page 10 of 66

2.1 The First Esperanto Communities

As extracted from Forster (1982), the earliest Esperanto local club was established in 1888, supposedly in Nuremberg, Germany. A couple of years since its establishment, the number of associations founded around Europe, Asia, USA and Latin America increases significantly.

In his book, Forster (1982) illustrates the growth of Esperanto groups between 1912 and 1926 as well as after WWII, showing how the communities develop rapidly around WWI. The period after WWI is considered a golden age for the language (Robert, 2016). The heaviest presence of Esperanto groups for Europe is documented in Germany and the Slavic countries, and outside Europe in Japan. The communities decrease significantly around and after WWII with the coming pressure from the Nazis and Stalin, who believe that the language supports Jewish domination (1925).

At present, the members of all Esperanto communities are impossible to count. A rough estimation has been made in 1987, where they were counted to be around 120.000 (Janton, 1993). In 2017, the Danish scholar Svend Nielsen makes an approximate calculation of 63.000 speakers worldwide based on a total of online profiles on the most popular Esperanto websites such as lernu.net, UEA, Pasporta

Servo, Esperantujo.directory, Edukado, as well as published official data on membership from

organizations (Nielsen, 2017a). Still, Nielsen does not mention if the profiles are active or in total, as that would certainly influence the number.

2.2 The Esperanto Associations in the Past

There are many specialized Esperanto associations established in the period after 1945 worldwide (Janton, 1993), where created by and for Esperanto enthusiasts, members desired to have a network within their professional field consisting of Esperanto speakers. Some of the biggest associations in the past are intended for Esperanto enthusiasts of music, law, medicine, philology, philosophy, journalism, economics, European affairs, cycling, and a few of the mentioned associations contribute significantly to the Esperanto communities, as they do research and publish on science and technology, despite their limited resources (ibid). Taking a note of the diverse associations that Esperantists worked on creating in the past says a lot about the personal values and culture members possesses.

The literature review does not reveal any collective representation such as special rituals, ceremonies, greetings or holidays practiced by the communities in the past and today. Today, there are two dates considered as Esperanto day, for which exist discussions: the first date is Dec 15th, the birth date of

Page 11 of 66 Zamenhof and most often celebrated as the Esperanto day, and the second date is July 26th, when the first Esperanto book Dr. Esperanto Lingvo Internacia (Eng: International language) was published for the first time(People's world, 2015) And finally, there is also the distinguishing Esperanto flag with its particular green colour.

Fig. 2. The Esperanto flag, first accepted in 1905, where the colors are said to stand for hope (green color) of the 5 continents (5-pointed star) in common understanding and peace (Martins, 2017).

2.3 Sense of Belonging and Connectedness in a Community

Communities as ‘the building blocks of a society’ have always played an essential role in our lives (Budiman, 2008). The earliest studies related to communities date back to 1880. Ferdinand Tönnies, a German philosopher and sociologist, best known for his contribution to the fields of philosophy and sociology, supports with his researches for the distinctions between the two kinds of social ties and groups (1887) - Communities defined as Gemeinschaft, and societies defined as Gesellschaft. Communities, according to Tönnies represent the structure of one’s social life that produces social relationships.

Page 12 of 66 Any kind of social co-existence that makes a person feel familiar, comfortable and exclusives is to be understood as belonging to a particular community (Tönnies, 1887). Societies on the other hand, or

Gesellschaft, are the artificially constructed entities, which consist of individuals living close to each

other but independent of one another (ibid). Such a sense of connectedness (or community) is also present in Maslow’s hierarchy under the third Love and belonging component (1943). This third level of the hierarchy represents friendship, trust, acceptance, affiliating and being part of a group as an essential human need to feel that one belongs (ibid).

Fig. 3. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

Communities are thus the more personal and intimate groupings who predispose members to contribute and strive towards a common goal and values of the particular grouping (Tönnies, 1887). Being a member with a strong community identity means that the individual would unconsciously see himself as a servant to the particular community, which creates fulfilment (McMillan & Chavis, 1986). Budiman (2008) add that communities are not necessarily based in a geographical proximity, as with the rise of Internet and technologies this is not a necessity. Wherever members are located, their bond stays strong, as they know they are working on the same task (ibid).

2.4 Online Communities

“Virtual communities are the social aggregations that emerge from the Net when enough people carry on public discussions long enough, with sufficient human feeling, to form webs of personal relationships in cyberspace. (Rheingold, 1993)”

Self – actualization

Esteem

Love and belonging

Safety needs

Page 13 of 66 Virtual communities are communities existing in the cyberspace and supported by computer-based IT, whose focus is communication and interaction driven by members (Yap & Bock, 2005, as ref. in Äkkinen, 2005). The very first virtual communities are tracked back in the beginning of the 90’s, with the rise of video games and had initially the idea to provide gamers with a place for sharing and distribution of different material, not necessarily related to games, which later contributes to the development of more communities (Preece J. M.-K., 2003). In their early rise, communities were perceived as exotic due to the still limited usage of the Internet (ibid). However, the feeling and perception of differentiation between virtual and face-to-face communities reduces with the heavier Internet usage in the end of the 90s (Rainie and Packel 2001, as ref. in Preece 2003) and the rapid development of technologies and Internet (Budiman 2008).

Similar to being a member in real-life communities, membership in virtual communities is also characterized by a strong need for sense of belonging and identity (Wellman, 1999). One of the earliest scholars to notice and study the early development of friendships, sense of belonging, trust and empathy among virtual communities that I managed to find, is Rheingold, who published the book “The Virtual Community” in 1993, based on his experience with The Well, one of the oldest virtual communities (Wingfield, 2012). In his book, Rheingold speaks of virtual communities not only as a virtual space for people to meet, but for also their function as a tool:

“Some people come to the WELL only for the community, some come only for the hard-core information, and some want both.”

Rheingold then compares virtual communities to real-life ones by defining the latter as having the strong need for a sense of space, where gatherings can happen compared to virtual communities that do not need such a sense of place, but instead need imagination (Rheingold, 1993). Later, in 1996, Hagel and Armstrong write “The real value of on-line communities”, with focus on how businesses can make profit on virtual communities. There the authors propose 4 different kinds of communities that meet consumer needs – communities of transaction, communities of interest, communities of fantasy and lastly, communities of relationships (Hagel & Armstrong, 1996). They further point out that the value of such virtual communities is in the intense loyalty these communities generate in their participants. They also highlight that all communities are characterized by interaction of members, as different as the communities might be from each other (ibid). In a later study, Wasko and Faraj conclude that “the most successful communities act out of community interest rather than

self-Page 14 of 66 interest”, simply because members believe this is the right thing to do (Wasko & Faraj, 2000). Another research by Typaldos from the same year proposes 12 elements from which online communities consist in a hierarchical order, very similar to the elements that Sense of community theory suggests for real-life communities (see fig. 4):

Fig. 4. Elements of virtual communities. Source: Typaldos, C. (2002) as ref. in Äkkinen (2005)

The table above, from my perspective, demonstrates more similarities to offline communities than differences – we all need a purpose, sense of belonging and identification with a community. Making such a distinction between offline and online communities is much more difficult today, and just as Lenard adds, “our physical and virtual life are blended into one” more than they have ever been (2015).

2.5 Classification of Community Members (fans)

A big part of the studies on media audiences are focused on researching of fans as part of the consumer culture (Sullivan, 2013). It can be argued that the Esperanto communities can be understood as a mix between communities of interest, relationships and fantasy, considering Armstrong and Hagel’s classification of communities (1996), where fans gather around a particular medium – the Internet, to cultivate their love towards the Esperanto language and culture. How communities develop with the help of the Internet makes them interesting for media studies.

Page 15 of 66 The origin of ‘fan’ is said to be an abbreviation for fanatic, originating from the Latin fanaticus, and had back in time the meaning of someone with ‘obsessive interest and enthusiasm for a particular

activity2’. The word ‘fan’ nowadays speaks more to a lesser degree of involvement of a fan, which which varies from low to high intensity (Thorne & Bruner, 2006).

Collectively fans constitute a particular media’s fandom or a subculture, where close feelings about a given media connect them, and one could often hear the usage of the same subject-specific jargon or linguistic code within this fandom (Fiske, 1992). This code could be expressed in the way they talk, greet each other, or dress. Fiske proposes that being a part of a fandom establishes not only self-identity, but it additionally could transform the fan’s participation into a political engagement and a form of resistance and emancipation from traditional authority (Sullivan, 2013; p.196).

As Sullivan mentions, fans are intriguing to research as they spend extraordinary amount of time and energy consuming one particular media and have their activities built around this particular media to fill out any gaps they might have, find out details and collect more information, which often means repetitive reading, searching, watching and looking (2013).

Along with this, Thorne and Bruner (2006) introduce a set of characteristics of fans: 1. Internal involvement

2. External involvement

3. The desire to acquire objects related to that particular media 4. Desire for social interaction with like-minded people.

The internal involvement relates to how fans focus their time and energy on the particular media, without being bothered if friends and family share their enthusiasm and understand them. The external involvement relates to the wish to engage more, maybe by attending group or community meetings or events. The desire to acquire objects becomes stronger after the internal and external involvement, and fans start consuming products related to that specific subculture in order to express their personalities (ibid, p. 54). Finally, the heavier involvement makes fans start interacting with each other, as scholars conclude (Thorne & Bruner, 2006).

Page 16 of 66 Abercrombie and Longhurst (1998) are some of the first scholars to recognize that there are different levels of excitement and involvement among fans, from which the scholars develop the so-called continuum of fandom (see fig.5). The continuum illustrates on one end the consumer, in the beginning of his excitement about a particular culture, to producer on the other end. The producer here might be anyone who decides to make something more out of their passion for particular media, but naturally, producers always start their journey by first being consumers.

Fig. 5. Continuum of Fandom

Source: Stephanie Plumeri, as ref. in Sullivan (2013)

The more fans’ enthusiasm about a given media text, TV show or music group grow, the more they desire to do something more with their passion than simply consuming it (Thorne & Bruner, 2006). As they move from consumers to enthusiasts, fans start interacting with each other, or reach the 4th characteristics of fans according to Thorne and Bruner - the desire to interact with like-minded people. They begin connecting with other fans with whom to share their interests and enthusiasm, discuss with over parts of that media, criticize together, engage in writing magazines or articles, and most importantly they start integrating elements of that media into their own lives (Sullivan, 2013). Distinguishing between consumers and enthusiast might be challenging in virtual communities. If the consumers are the new users, who simply read and do not interact, then noticing them and distinguishing them would be difficult. Preece et al. (2004) are one of the first scholars to research

lurkers, defining them as “the member who has does not post anything in the online community he

belongs to, but just reads what the others write about” (ibid). Such lurkers might be initially the

consumers, who start reading in order to collect more information about the group they have recently

Page 17 of 66 might be motivated from the fact that consumers or lurkers might already receive the information they need, so there is no need for further interaction at this point. To sum up, fandom can take many forms, depending on where a fan is standing within this continuum. The continuum can be understood as a map that allows movement – from consumers to fans and producers, when their interest is increasing, and from producers to fans and enthusiast, when their interest in particular media is decreasing.

Connection for such fandom nowadays happens most often on the social media due to the ease of access – in different forums, websites or virtual groups and communities (Budiman, 2008), but also in real life local and global meetings and gatherings, some of which themed according to the particular media (Sullivan, 2013). Social media community building demonstrates a positive level of interaction between students. More specifically learning communities report a higher engagement in class and better grades among students who use Facebook groups to study and keep up with other students (Felicitas M. Brecha, 2017). However, as Shareefah (2017) points out, Facebook has also several weaknesses concerning its possible censorship by governments, as well as other Internet regulations through which social media users could be constrained, such as user removal of groups and blocking. Facebook also has the right to remove content if the content has any offensive, religious or sexual tone (ibid).

2.6 Sense of Community theory

Other central studies on communities that need to be mentioned are by McMillan and Chavis. The scholars develop a definition that grasps the concept of belonging to a community as the core of their

Sense of community theory originating from 1986. Sense of community is defined as the feeling of

belonging and knowledge that one’s presence in the community is of importance (McMillan, 1986). Initially, in 1986, the scholars present 4 principles that constitute sense of community and belonging:

Membership, Influence, Reinforcement of Needs, and Shared Emotional Connection. Later, in 1996,

McMillan develops the theory further by extending the principles and re-arranging the names of the 4 initial components to Spirit, Trust, Trade and Art respectively. As described by him, ‘Sense of

community is the spirit of belonging together, a feeling that there is an authority structure that can be trusted, an awareness that trade, mutual benefit come from being together, and a spirit that comes from shared experiences that are preserved as art’ (McMillan, 1996, p. 315). The four concepts could

be found briefly described in the graph below (fig.6). It is important to mention that all these 5 attributes need to work together to define who is part of the community and who is not (McMillan &

Page 18 of 66 Chavis, 1986). The sense of belonging and sense of communities are for that reason the involvement and experience of an individual within a community, his perception of similarity with the rest of the members and willingness to contribute to the economy of that community, knowing one’s place and expecting that one’s needs will be met (Sarason, 1974, as ref. in Barbieri, 2014). All these aspects combined together create the desire to stay in the community, or the strong sense of community.

Page 19 of 66

Fig. 6. Sense of Community components Source: McMillan and Chavis (1986)

2.7 Social Identity Theory

Social identity theory is another theoretical framework as an addition to Sense of Community Theory, which is looking at ways to understand and explain intergroup behaviour. It is first introduced by Tajfel and Turner in 1979, and as the theory reads, a person’s perception of himself (that is, his social identity) depends in a big extent on the groups one forms part of (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Tajfel and

Page 20 of 66 Turner argue that social identity is the individual’s self-image, derived from the social categories with which one identifies himself. This is to say that a group membership affects one’s behaviour, as the social identity we expose to the world differs from one community to another, due to the different circle of people in each group (ibid).

Predominantly, members try to create a positive self-image of themselves within a particular group and compare the group with other social groups so as to ensure its distinctiveness (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). If the community is perceived as salient and exclusive, the result is usually that members are motivated to stay and contribute to that community, in order to protect the social status of the community or group (McKinley, 2014). This would consequently make them act as ambassadors for the positive image and perception of the community (ibid).

Adding on Sense of Community Theory, Tajfel points out that members’ stimulus to contribute is not always necessarily as an expectation for monetary reward later on as a result of their membership. Participation is also often influenced by the social and/or cultural capital that each one of us possesses. In an article from 1985, Bourdieu represents the social world as a multi-dimensional social space (or field), where agents are distributed and defined according to their position in this social space in accordance with the volume and composition of their capital (The social space and the genesis of groups, 1985). Knowledge of where one is situated within this social space speaks of his condition and position, however it also helps individuals create a sense of one’s place (ibid). Furthermore, Bourdieu argues that gathering of different agents in groups or movements is more probable to happen if they are in close relation to the social space of one another, but can also happen if other ideas unite them, e.g. national identity or moral views (ibid, p. 726). Still, the latter are more likely to split due to their differences in the social space, as Bourdieu explains. The concept of distinction, also called symbolic capital, is then presented as one’s position in the social space in relation to other groups seen through categories of perception of an agent (ibid, p. 730). There is to an extent a pursuit of distinction, which, as Bourdieu argues, might be expressed in the way one speaks, ultimately creating boundaries and separations. Such a distinction later attracts similar distinctions, or as Bourdieu states: “symbolic

capital goes to symbolic capital.” Another distinguishable work of his book Distinction (1987) was also

used for reference. There he speaks of the social hierarchy of consumerism, also called class, focusing his research on taste and preferences based on results from a survey. His writings demonstrate that the different choices are not objective and are all distinctions in oppositions to the choices of different classes of people (ibid).

Page 21 of 66

2.8 Cultural Capital

In another sociological essay from 1985, The forms of capital, Bourdieu introduces three distinct forms of capital: economic, social and cultural. Capital, as described in Cambridge dictionary is the wealth to

produce more wealth. In line with Bourdieu’s essay, social capital is the social connections and

relationships that can help a person achieve a higher status in society through the acquisition of cultural capital. In contrast, cultural capital is the intellectual knowledge that could be later converted into an economic capital.

Correspondingly to Bourdieu’s definitions, cultural capital exists in three forms: embodied, objectified and institutionalized (1985, p. 47). The embodied cultural capital is the knowledge that a person accumulates while growing up, e.g. culture and behaviour. The objectified is the capital in the form of material possessions, such as writings or paintings (ibid). And lastly, the institutionalized capital relates to the academic or professional qualifications of a person. A study building upon Bourdieu’s concepts from 1995 examines a sample of Mexican-origin US high school students, where authors find that cultural capital in the forms of grades and education is related to the later creation of ties between students and other institutional agents, such as teachers and counsellors (Stanton-Salazar & Dornbusch). In other words, acquiring cultural capital assumedly leads to a later acquisition of social capital. In another study from 2017, Pakistani scholars are exploring how Facebook contributes to

bridging and bonding of social capital among Business students in Pakistan, where Facebook allows

participants to sustain connections easily for its user-friendliness and fun to use (Raza, 2017).

Another scholar, drawing heavily upon Bourdieu’s concepts of capital and introducing the concept of “fan cultural capital” in relation to fans’ object of admiration is John Fiske, who speaks of fans trying to accumulate cultural capital in the form of any information related to their fandom, which ultimately increases their ties within the fan community3. Fiske, based on one of Bourdieu’s most known work

Distinction (1987), also explores cultural hierarchies in societies, societies being fan communities. He

presents how fans tend to separate themselves from the popular mainstream culture by joining distinguished communities. Fiske also proposes that fans can start discriminating within their community as well, becoming “the harshest critics of their favourite programs and movies” (Fiske, 1992, as ref. in Sullivan, 2013).

The Croatian linguist and sociologist Nikola Rasic is one of the first scholars to research multilingualism among Esperantists in the 20th century (1995), and his study shows that on average every Esperanto

3 Fan Culture; Fiske, J. https://sociology.iresearchnet.com/sociology-of-culture/fan-culture/ (accessed

Page 22 of 66 speaker can converse in 3 more languages, in addition to Esperanto and a native language. Interestingly, 4.4% of the interviewed participants knew no other language besides Esperanto (Rasic, 1995; as ref. in Fettes, 1996). English, German and French are reported as the most widely spoken languages among Esperantists. Rasic also notes that the majority of the participants have a higher education on a university level or similar, and many of them state that they feel more secure using Esperanto than any other language (ibid, p.56).

In one more research conducted by Svend Nielsen from 2017, an attempt has been made to evaluate the density of Esperanto speakers by variables such as country, contribution to science, culture and health, linguistic diversity, GDP (2017b). Nielsen concludes that there are more Esperanto speakers in countries that contribute a lot to science and culture than in any other countries, and the linguistic diversity is of no importance for them. The countries with the most Esperanto speakers were reported to be among other the Scandinavian countries, Switzerland, France, Lithuania, and Iceland (ibid). To sum up, to understand the way bond and connectedness are generated within the Esperanto community on Facebook, I have relied heavily on Sense of community theory (1987), Sense of identity

theory (1979), Bourdieu (1985; 1987), Fiske’s definitions of fandom (1992). While Sense of community

theory was initially created for real-life communities, I believe belonging and how people bond online and offline is very similar, as much as the Internet has given broader possibilities to be more connected. The used Sense of community theory is a classic theory in the sense that it provides 4 easily identifiable components within the interviewees’ speeches and the digital ethnography, and proved to be very similar to Typaldos’ 12 elements of online communities from 2002. To get an understanding of how a culture of community is created online is to also understand who the members are and what their motivation to join and stay in the communities is, as well as how they interact between each other to create bonding. Here Bourdieu’s definitions of cultural and social capital helped, which proposed new lenses on group behaviour, suggesting that groups or communities tend to stick more if they have the same values and interests, which was used to analyse interviewees’ responses regarding the more specific Esperanto communities they belonged to and also explaining boundaries which can be created in order to keep the group’s identity. The continuum then helped categorize the interviewees’ answers through for the 4 level of interactions, which were investigated within the FB group Esperanto group.

Page 23 of 66

3. Data and methodology

3.1 Methodology

For this study, I opted for an inductive mixed approach through the paradigm of interpretivism. As in most inductive approach studies, research is undertaken to make sense of the phenomena, and the theory is used to help interpret the collected data, allowing for a more flexible way of generating knowledge (Collins, 2010). As the Esperanto phenomenon is developing online and Internet is currently one of the main used media to create an Esperanto culture (Salisbury, 2017), the study was set to be collected online, as online was where a community was being developed and participant observation could be done while members interact with each other. Facebook was then chosen as the focus of the study after the first interviewee Enric highlighted several times that there are many Facebook groups used heavily for communication and sharing of material between the members, from which he also takes constantly part. I came across the public Facebook group Esperanto, which had more than 22.000 members sharing daily, making it perfect for digital ethnography and for further collection of data sets such as interviews.

Initially a questionnaire was created and spread in different Esperanto forums and groups online with the idea to ask members about their perception of the Esperanto communities, however this data set did not collect enough responses, but got 22 comments which I have used to analyse. Along with the questionnaire, the first interview to compare to the questionnaire findings was conducted, followed by a brief digital ethnography, 1 more interview and 1 brief conversation with a Bulgarian Esperantists, which are described further in the next sections from a social constructivism (also called constructionism) perspective. As much as an attempt was made to conduct more interviews, finding participants turned out to be very challenging, which is why the brief conversation with the Esperantists Mariana was done, as a way to accumulate more data sets in order to compensate for the not completed questionnaire.

My outsider position benefitted the study as I tried to present the findings in a non-biased way for not having any prior knowledge or opinions, focusing on what I get as information from participants. The expected outcome was to collect primary data on how sense of community is generated online through member interaction by comparing interviews, digital ethnography analysis, questionnaire and seeing how these relate to theory with the ultimate goal to contribute more to the studies of online communities and lack of researches on Esperanto.

Page 24 of 66 In terms of the research stand, social constructivism presents the epistemological view that knowledge depends on the interpretation of the social actors, constructed through their interaction with the environment of the social context (Collins, 2010). In other words, the aim of the chosen methods for this study was to understand the sense of belonging within the communities through the lenses of the members – from their experiences and created meanings, and from what I document from their online interaction, without highlighting one valid truth or objective reality. As Collins further adds, using such an approach is not to say that all extracted data is to be considered ‘the ultimate

truth’, but that their ‘truth’ is to be taken into consideration and critically reflected upon

simultaneously, in order to produce new meaning or knowledge. Moreover, this approach acknowledges that understanding of the phenomena may still be incomplete, as it also contains information available at the time from members participating at the time.

3.2 Interviews and data sets

A data collection method that was taken use of was conduction of semi-structured interviews. The idea of interviews is to use people as the primary source of knowledge for a particular study. Using an interview to research sense of belonging in the Esperanto communities enabled to hear about members´ opinion, ideas and behaviour towards these communities. The participants were based outside Denmark, therefore the interviews were conducted online.

The interviewees that could serve best for the purposes of this study were selected carefully. The administrators of the Facebook group Esperanto and Duolingo Facebook group for Esperanto speakers or learners were targeted. The administrators of the groups mentioned above were behind the creation of the virtual spaces for Esperantists, and assumedly could share insights on members’ behaviour as no other members could. The search process for administrators to interview began early in the project, the research question was presented to them, as well as a brief overview of topics that they will get asked for. I contacted 7 administrators from these 3 active Esperanto groups on Facebook, but there was only 1 positive reply by Enric Baltasar, one of the administrators of

Comunidad Esperanto Duolingo. I was also interested in the members’ opinion, as they would have

also provided interesting perspectives, but the invitation was, unfortunately, refused.

The interview criteria that respondents had to fulfil in order to participate were to be active Esperanto community members and to have participated in Esperanto global or local gatherings in the past and recently. Ideally, participants would speak Esperanto on an intermediate level and would have participated for at least 1-2 years in the virtual/real-life communities, and finally, they would have

Page 25 of 66 preferably travelled or hosted through Pasporta Servo. Variables such as income, age, location and education were also asked to form a demographic profile of the average Esperanto member.

The first participant that agreed to a Google Hangouts interview was the youngest president of TEJO (The Esperanto Youth Organization) Enric Baltasar, 26-year old Spaniard, initially being part of the Esperanto communities only as a member for a long time, and later becoming the Youth President of TEJO, where he spent 1.5 years. Furthermore, Enric Baltasar contributes to the Esperanto course on Duolingo since its launching in 2015. He is now an administrator of the popular group for learning of Esperanto for Spanish speakers, Comunidad Esperanto Duolingo, and is also working on personal projects. His participation enhanced the research due to the fact that he has been both a long-term member and a president of the youth organization for almost 2 years, making him a credible participant, who had seen the both sides of the communities – from members’ perspective and from leaders’ perspective. He was willing to share insights openly, which contributed a lot for a fruitful analysis. The interview was conducted on Google Hangouts, recorded, and lasted 40 min.

The second interview was conducted later with a Dominican Esperantists, a member for almost 20 years, who I found through a post he made on the FB group Esperanto sharing music in Esperanto. Rafael Hernandez has been part of UEA since his very first online involvement with the communities and has participated extensively in different events and congresses worldwide. He is currently working on establishing the first Dominican – Esperanto association in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. The third participant was a Bulgarian Esperantist, called Mariana Georgieva Evlogieva who has also been part of the communities for around 20 years and has been a teacher of Esperanto ever since. I found her contact through a comment she left on the FB group Esperanto and approached her in Bulgarian. She is the first woman to create an online Esperanto course for Bulgarians in 1998. The interview was in the form of a conversation on Facebook, where she agreed to answer questions. The interview preparation for Enric included a list of questions and topic areas that had to be covered, inspired by the Sense of community theory (McMillan & Chavis, 1986), Bourdieu (1985; 1987) and Fiske’s writings (1992). The questions were asked in a way that allowed for flexibility, depending on how willing the interviewees would be to speak and share. Similar questions got the other participants, but the focus there was to cover more topics regarding the interaction online and how the Internet contributes to the Esperanto culture and a member’s participation.

Page 26 of 66

3.3 Extract from survey data

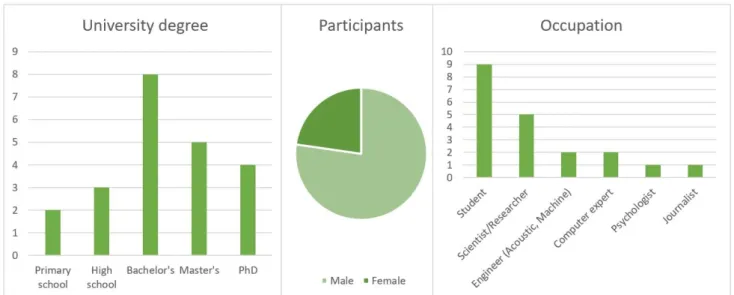

The initial set of collected data for this thesis involved a questionnaire (see app. 1), published in and targeted towards the Facebook group Comunidad Esperanto Duolingo, Duolingo forums, other smaller Esperanto groups on Facebook and Reddit Esperanto users. However, it did not receive a high response rate and was then replaced by the 3 conducted interviews and digital ethnography. The total responses for the questionnaire were 65 answers plus 22 comments, yet not all questions were answered. For this reason, I have still made use of it but concerning only the demographic profile and comments of the respondents who have left comments. The commenters’ demographic profile that was extracted from the survey could be seen in the graphs below:

Fig. 7: The graphs indicate University degree, gender (Participants) and Occupation of the 22 commenters in the survey. The vertical numbers show the number of people belonging to a category

(for University degree and Occupation).

The University degree table above shows that the Bachelor’s degree was the dominant degree among the respondents – 8 out of 22 indicated a Bachelor’s, followed by 5 respondents with a Master’s degree and 4 with PhD. 9 out of 22 respondents have pointed out student as their occupation. The middle pie chart shows that the majority of respondents who left comments were male (18/22). Their average age was 36 years and came mostly from the US, except for 5, who indicated they came from Russia, Brazil, Canada, Finland and Japan. This set of data was used together with Bourdieu’s theories on cultural and social capital, to be able to draw a profile of the average Esperantist online to the extent to which it was possible, and the cultural capital members possessed, used to compare to the literature reviews which was indicating high cultural and social capital among Esperantists in the past.

Page 27 of 66

3.4 Digital ethnography

Another used data set was the digital ethnography. As Varis (2014) describes it, it would be quite challenging to describe the process of digital ethnography, as it is not a method, but more an approach not reducible to specific techniques (ibid). The method consisted of observation of participants in the FB group Esperanto to gain brief behavioural insights. Web ethnography was done through collecting and analysing the posts generated in this group, as well as files and documents that were shared within the group. For three weeks, from 27.09. 18 until 13.10.18, I kept a diary of the daily activity in this group, where I tracked what members were posting, sharing, re-sharing, and discussing, to get an idea of the topics they found interesting to speak about, and how they used social media to create a community and a feeling of belonging. The tracking showed an average of 14.6 publications a day. All content for this period included exactly 190 publications, without counting posts not directly related to the community or the language. I also counted older posts who were newly re-shared and commented, as if they had activity, then it meant that it was type of content that members found appealing. The targeted audience for this method was all active participants in the group.

3.5 Ethical Consideration

As Collins (2010) writes, ‘we all have a moral outlook, governing how we behave and how we

determine what is right and wrong.’ And while there are many aspects on which the majority of a

society agrees, there could always be found disagreements about these same aspects. For this research I looked into a few important ethical codes, based on Resnick (2015), which are depicted below:

- Honesty and integrity – I believe to have conducted the literature review, data collection, analysis and results of the research in an honest manner. All quotations and borrowed work have been cited and are present in bibliography and as online sources.

- Objectivity – I strived for as objective research as possible. No interviewees or questionnaire participants were close to me as to avoid any bias based on a relationship, and I am also relatively new to the communities, thus I did not possess any prior views on the Esperanto communities before initiating the research. The target group and sample for both the questionnaire and interview were also chosen so as to reflect as objectively as possible the Esperanto communities.

Page 28 of 66 - Openness – The data collection process, analysis, and results from this study are open to public, and I am willing to share any further graphs, recorded and transcribed interview or

information needed later on. I am also open to new ideas and criticism of my work.

- Confidentiality and permission – Confidentiality was one of the most important aspects concerning the qualitative data for this study, as it involved conduction of interview with an Esperanto member, who was a former president of TEJO. Before the interview, the knowledge that this thesis might be disseminated and affect the participant was carefully considered. Upon initiating the interview, I asked for the interviewee’s consent to record and transcribe the interview. Enric, Rafael and Mariana agreed to have their real names stated with the condition that they will be later sent the transcribed interview and all parts that involved them directly, which was respected. No further issues were reported from the interviewees’ sides or participants.

The digital ethnography analysis followed the 4 main principles of the Code of Human Research Ethics by BSP from 20074:

1. Verifying identity – Researcher’s identity, research topic and method were shared with an

administrator of the group, presenting the aim of the study in detail and what is to be collected.

2. Public/private space:

– Address of forums & online pseudonyms not published – Names and profile pictures have been blurred. Nonetheless, the group is currently public and accessible by anyone, which also means that sources can be tracked.

3. Informed consent – One of the administrators of the Facebook group Esperanto, D. M. W. was aware of the research and provided his consent about its conduction.

4. Deception – The administrator was aware of how the data is to be collected, and that names and photos will be blurred.

5. Data protection: consent for processing of personal information. – Members were not aware of the data collected except for one of the administrators. The BPS report (2007) reads the

4 BPS (British Psychological Society) (2007). Report of the Working Party on Conducting Research on the

Internet: http://www.bps.org.uk/sites/default/files/documents/ conducting_research_on_the_internet-guidelines_for_ ethical_practice_in_psychological_research_online.pdf (accessed 30/10/18)

Page 29 of 66 following: “Visual researchers may conduct research in public places or use publicly-available

information about individuals (e.g. naturalistic observations in public places, analysis of public records, or archival research) without obtaining consent” (Papademas and IVSA, 2009: 255,

as cited in BPS 2007:3).

3.6 Limitations of the Study

As a limitation of the study, I would define my very basic proficiency in Esperanto, which affected the willingness of some members to participate, explaining they could not express themselves as well in English as they could in Esperanto. And while there are quite a few limitations of the study, I tried to make use of as much data sources as possible, presenting new

Similar to biases in interviews and questionnaires, the digital ethnography could also be biased. As Kirk (2014) explains, presented data and observations always remain incomplete and in a sense biased, as what we see depends on what the researcher would choose to show and mark as important. He further adds that when selecting a certain type of data, we simultaneously choose not to include other sets of data, but one still needs to be objective and follow the phenomena as they unfold and reflect them as good as possible. One more limitation to this method is the limited time frame when the data was collected - 27.09. 18 until 13.10.18. Digital ethnography is usually done within a larger time-frame to be able to track the content, as it might be that members share or get involved less in this period compared to other time of the year, which would certainly impact the findings. Still, to try to reduce the possibility of such kind of bias, I also reviewed older publications and active discussions as a way to ensure that all type of content was covered and documented in my findings while backing it up with interviews.

One more limitation that needs to be mentioned is that this research was done through my external research stand, as a member of the community who does not speak the language, nor engages in discussions due to my basic Esperanto proficiency. Thus, the documented findings are through my

observer lenses. There was also content on the Facebook group Esperanto that I could not grasp the

meaning of, and for this reason I counted it as other content (fig.8). This fact once again defined the boundaries between speakers and non-speakers, inevitably affecting the conclusions of this thesis. A final point that needs to be clarified is that the study is investigating the sense of belonging in the online Esperanto communities as a whole as it was represented by members, but has not been narrowed down to one particular community or location, which would have complicated the data collection, as none of the 2 big Esperanto organizations had one specific social media channel through which the research could have been done.

Page 30 of 66

4. Findings and Analysis

4.1 Esperanto Facebook group and interviews

The conducted observation online was focused on analysing the interaction between members in the biggest Esperanto group on Facebook, called Esperanto, which has a membership of 22.459 people. The group allows posts only in Esperanto, and is targeted towards Esperantists with a good level of Esperanto. I was interested in observing members’ discussions and publications, and I started collecting daily data on the type of topics they were discussing and sharing for a set time frame. My very first observations of this group were just to help me get an idea on the most discussed topics, which I divided in sections, and was then adding daily the number of publications belonging to each section. Yet, not all publications and activity were documented in my research diary as some posts included photos and texts I could not understand and translate due to not being part of the community, so I need to highlight once again that this research was through my lenses of an external observer and one not-interacting with the members in Esperanto. Also, another fact worth mentioning is that many old publications from 2014 and 2015 re-appeared as new posts for the ongoing engagement of members with these posts. They counted as one publication, and were distributed according to the categories. A summary of all shared content in the group for the chosen timeframe could be found in the graph below:

Page 31 of 66

Fig. 8. Categorized type of content in the Facebook group “Esperanto” for the period 27.09.18 – 13.10.18 (see app. 3, fig. 8 for clarification of the categories).

The total number of categories that I managed to define after going through the content of the group was 12, and the total number of all publications shared in the group for the selected period was 190. On average there were 14.6 publications posted a day, and the category with most publications was

Page 32 of 66 the one referring to posts about past and upcoming events, most often events organized by UEA, which was also indicated by the group itself. This as McMillan and Chavis (1986) explain as the emotional connection between the community members – the making and sharing of history of events within the community and the knowledge that this will continue to develop (see fig.6). The second most published category was news and information, which was most often an external link leading to Esperanto news websites and information about the communities in Esperanto. Publications related to news were one of the most engaging ones as they attracted discussions where members were presenting their views. This category also included posts related to Esperanto and its worthiness nowadays. This category also demonstrated how members develop their culture by being both in line with current political situations and practicing the language by translating the news at the same time.

Hobby and entertainment was the third most shared category consisting most often of funny videos

through external links. This was also one of the most commented and engaging categories (see the rest of the categories in app.3, fig. 8). The interviewee, Rafael, confirmed that this is the category in which he most often engages, in the posting of the so-called memes, as they are “a fun way to use the

language to laugh and to have a nice time in the group.” Enric explained that he does not engage often

in discussions under publications in the Facebook group Esperanto and in his group Comunidad

Duolingo Esperanto, but most often “takes the initiative to write posts and start discussions related Esperanto and its current leadership”, which he tries to challenge, and shares it with his friends

Esperantists on his personal profile, instead of in a group.

Besides keeping a daily journal on the activity in the group in terms of what members found interesting to share, I also noted down the most commented discussions in the group, for this period where I took notice only of the publications with more than 15 comments. The titles of the discussions are translated into English:

Page 33 of 66

Fig. 9. The most engaging publications from the Facebook group “Esperanto” for the period 27.09.18 – 13.10.18. The discussions with most engagement are highlighted in darker yellow, and it could be seen that 2 out of 4 are regarding UEA and relate to political discussions concerning migration and challenging Esperanto as a language.

Once again, the categorization above (fig. 9) demonstrates that the most popular discussions in the group relate to UEA (Universal Esperanto Association) events not only as the most shared ones but also as the most commented ones. Other very engaging discussions in the Facebook group Esperanto were related to current political events most often asking members’ for their opinion, and to Esperanto’s identity and worthiness nowadays. In the latter, members were defending Esperanto as if defending their community identity and purpose, present as ‘boundaries’ and Us vs. Them attitude in the Sense of community theory (McMillan & Chavis, 1986). Nonetheless, it needs to be mentioned that only the content that was approved by administrators was possible to analyse, as the administrators have the right to remove content in other languages than Esperanto, as well as offensive or religious posts (Shareefah N. Al’Uqdah, 2017), which might have affected the content that appears on the group.