Skärlund, S. (2020).The recycling of news in Swedish newspapers: Reused quotations and reports in articles about the crisis in the Swedish Academy in 2018. Nordicom Review, 41(1), 69–84. https:// doi.org/10.2478/nor-2020-0005

The Recycling of News in Swedish

Newspapers

Reused quotations and reports in articles about the crisis

in the Swedish Academy in 2018

Sanna Skärlund

School of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences, Halmstad University, Sweden

Abstract

Newspapers in Sweden are experiencing reduced revenues due to decreases in advertise-ment sales and reader subscriptions. Given such circumstances, one way of being more cost-effective is for journalists to recycle pieces of texts already published by others. In this article, I investigate to what extent and how the four biggest newspapers in Sweden do this. Following a close reading of 120 articles about the crisis in the Swedish Academy in 2018, I found that the newspapers included recycled quotations attributed to other media to a great extent. Moreover, recycled statements from other media were often intermingled with quotes from new interviews; however, social media were not used as sources very often. A discus-sion of the problematic aspects of “a culture of self-referentiality” concludes the article.

Keywords: journalism, recycling of news, churnalism, Swedish newspapers, social media

Introduction

Since at least 2008, the crisis of journalism has been widely discussed (e.g., Davies, 2009/2008; Lewis et al., 2008b). Picard (2014: 500) summarised the issue by stating that “there is a widespread perception that legacy news providers are dying, that quality journalism is disappearing, and that we are witnessing the twilight of an age in which journalism informed and ensured democracy”. Newspaper newsrooms are often con-sidered the centre of the alleged crisis (Luengo, 2014).

The circulation of printed newspapers has declined in Sweden over the last two dec-ades (Allern & Pollack, 2019; Nygren et al., 2018). In 1990, 81 per cent of the people interviewed in the annual Swedish Opinion and Media survey reported reading a printed daily newspaper at least five times a week – in 2017, only 34 per cent did (Martinsson & Andersson, 2018). According to Nygren and colleagues (2018), the circulation of printed newspapers peaked in 1989 and has since declined by 40 per cent. At the same time, income from advertisements has decreased dramatically.

For decades, journalists have – at least to some extent – relied on press releases and news agency material to create news stories (e.g., Boumans, 2018; Martin, 2015). As newsrooms are being allocated increasingly less time and money to produce more news than before (e.g., Lewis et al., 2008a; Moloney et al., 2013), this tendency to recycle texts originally produced by others has become more accentuated (e.g., Cagé et al., 2019). Social media platforms make it additionally possible to find newsworthy pieces of text in new places not limited to press releases or news agencies. Furthermore, the digital publishing of other newspapers gives instant access to texts that can be quoted or referred to in new articles within minutes. These factors result in journalists recycling texts more and in new ways than before.

In the present article, I investigate this recycling of news, taking articles about the crisis in the Swedish Academy in 2018 as a point of departure. The aim of the study is to show to what extent and how Swedish newspapers recycle pieces of texts from one another, and from other media, to create new articles. This recycling creates an intertextual network between different media, and it relates to concepts such as “ag-gregation” and “churnalism” discussed among media researchers lately (e.g., Bakker, 2012; Davies, 2009/2008). I explore the study’s overarching aim through the following two research questions:

1. To what extent are the Swedish news articles about the crisis of the Swedish Academy in 2018 made up of material attributed to other media?

2. Which media are the preferred sources for attributed material recycled by Swedish journalists during the crisis?

Because extensive recycling is often described as a threat to democracy (e.g., Jackson & Moloney, 2016) – and social media, on the other hand, is pointed out for its democratic potential (e.g., Brandtzaeg & Chaparro Domínguez, 2018) – research question 2 takes a special interest into what extent content is derived from social media.

The amount of recycled news has been analysed in Denmark (Lund, 2000, 2001; Lund et al., 2009) and Norway (Erdal, 2010), but these studies were mainly quantitative and focused on whether the entire article, or its topic, had been taken from another source, and not on the amount of recycling within the texts, which is the subject of this study.

The next section presents research on journalists’ recycling practices, followed by a short overview of journalists’ use of social media systems. A description of the study’s materials and method precede the presentation of results, which I relate in two sections. The first section addresses the quantity of recycled quotations and the number of articles that build on old and new interviews, respectively. The second section reports on the sources used in the articles. I conclude by discussing the problematic aspects of extensive recycling and the possible democratic potential of social media.

Recycling of news – aggregation and churnalism

Even though text recycling has long been common practice in journalism, the simplicity by which anyone can now find and copy-paste material from sources on the Internet into new texts is undoubtedly new. Today, pieces of news are increasingly being circulated in the digital landscape – links connect news to older news, and news stories are circulated

from newspapers to various forms of social media and vice versa. Moreover, some web-sites have taken on the role of aggregators, that is, they collect news from the web and publish summaries along with links to the original sources (Bakker, 2012; Coddington, 2019). In Sweden, the app Omni is a typical example of this aggregation practice.1

The practice of “journalists sitting behind their desks recycling or regurgitating PR and wire material” has derogatorily been labelled “churnalism” (Witschge & Nygren, 2009: 38). The term is usually traced back to Nick Davies, who popularised it when he used it to describe how “the heart of modern journalism [is] the rapid repackaging of largely unchecked second-hand material” (2009/2008: 60). Today, the concept churnal-ism sometimes encompasses other types of recycled content as well, for example from social media and online news sites (Johnston & Forde, 2017).

The increased reliance of newspapers on recycling strategies, especially in online news production, has been widely discussed. Most recent studies either describe journal-ists’ own conceptions of changed journalistic practices (from interviews, surveys, and ethnographic studies; e.g., Boczkowski, 2010; Manninen, 2017; Phillips, 2010; Thurman & Myllylahti, 2009), analyse quantitatively to what extent news are recycled, or both (e.g., Cagé et al., 2019; Erdal, 2010; Hendrickx, 2019; Lewis et al., 2008b; Lund et al., 2009; Saridou et al., 2017; Vonbun-Feldbauer & Dogruel, 2018; Wheatley & O’Sullivan, 2017). The overall picture emerging from these studies is that of more news being pro-duced over time, but largely because more recycling is taking place.

Boczkowski (2010) points out that neither journalists nor consumers like this “spiral of sameness” (173), where “more has become less in an evolving age of information abundance” (186), but that people feel unable to do anything about it. Moreover, Man-ninen (2017: 215) notes how the Internet has contributed to increased productivity, but it is realised as “more products, instead of better products [emphasis original]”. Sup-porting this, Saridou and colleagues (2017: 1020) state: “Instead of being exposed to more pluralism, to more independent reporting, and a more transparent and wider news agenda, citizens are faced with a shrinking and elite-influenced news diet”. Even people working with public relations, in fact, seem to be unhappy about increased churnalism, since such practices erode trust in journalism, thereby making public relations copy reprinted in newspapers less credible (Jackson & Moloney, 2016).

In an analysis of more than 100,000 edited Danish news pieces, Lund and colleagues (2009) found that the number of articles recycled from other media increased from 42 per cent in 1999 to 64 per cent in 2008. Likewise, in a Norwegian study, half of the news articles from newspapers covering the whole country were taken from news agencies or from other media – although these articles were often short compared to those produced by the papers themselves (Erdal, 2010). Recycling increased in Greek online news media during the period 2013–2016, and the most common sources for recycled content in an analysis of 100 articles from 2016 were the national news agency, press releases, and other mainstream media websites (Saridou et al., 2017). Moreover, a study of online pieces in Finnish media shows that about half of the 113 analysed texts were based on press releases or other media only, and most pieces using several sources combined preproduced and new content (Manninen, 2017).

There are, however, some notable exceptions from the overall picture of diversity being lost in modern journalism (Boumans, 2018; Van Leuven et al., 2014). Boumans (2018) did not find any evidence of increased reliance on press releases among Dutch

newspapers and news agencies 2004–2013 and relates this to less market pressure af-fecting journalists in the Netherlands than in the US or the UK.

Most recent studies on the recycling practices of journalists have focused on online publications and large datasets, and more in-depth analyses of how material recycled from different sources is woven together to make new news articles are scarce. This study explores 120 printed articles pertaining to one specific topic: the crisis in the Swedish Academy in 2018. Thus, it is possible not only to conclude that recycling takes place, but also to investigate to what extent direct quotes attributed to other media are recycled and how newspapers create new articles from old material.

Use of social media by journalists

Social media platforms have become important locations for journalists engaged in mak-ing news observations, collectmak-ing material from politicians, findmak-ing comments, under-taking research, and looking for new stories (e.g., Brandtzaeg & Chaparro Domínguez, 2018). In Sweden, 88 per cent of the 263 journalists included in a 2017 survey reported that they used social media platforms for sourcing stories during a typical week (Gulyas, 2017). Moreover, 27 per cent conveyed that they published a story from information found in social media sources “every day” or “every week” (Gulyas, 2017: 892). Hedman and Djerf-Pierre (2013: 376) found that information gathering was the most important task carried out on social media by Swedish journalists, and concluded that “social media are perceived mostly as a new tool for carrying out the traditional task pertaining to all journalistic work – to find out what is going on in the world”.

People who were formerly used as sources in news reports, according to Wahl-Jorgensen and colleagues (2016), are now communicating with the public directly – through social media platforms. In addition, politicians and entertainment stars alike use social media to break news and make announcements they know will be picked up by traditional media (Schifferes et al., 2014). Social media systems have an important democratic potential, suggest Brandtzaeg and Chaparro Domínguez (2018), since jour-nalists’ use of them in news gathering makes it possible for several different voices to be heard. Similar arguments that social media platforms enable easier access to “the voice of the people” have been made by other researchers (e.g., Picard, 2014); however, the risk of social media becoming “an echo chamber with fellow journalists and political insiders” has also been highlighted (von Nordheim et al., 2018: 811).

In a study of how two Belgian newspapers referred to YouTube, Twitter, and Face-book, Paulussen and Harder (2014) found that only a few articles in each newspaper mentioned social media on an average day, and that most of these articles used other sources as well. In addition, quotations reproduced from social media were mostly from well-known people, especially celebrities, while ordinary citizens were normally referred to anonymously, as a crowd rather than as individuals. In three newspapers (American, British, and German) analysed by von Nordheim and colleagues (2018), Twitter was a more popular – and elitist – source than Facebook. Another study showed that tweets in Dutch and British press were most often used to illustrate an event by adding a quota-tion from someone involved – a celebrity, athlete, ordinary citizen, or politician – and that Twitter made it possible for journalists to add quotes from persons not available for interviews (Broersma & Graham, 2013).

Materials and method

The data analysed in this study comprises articles from 2018 pertaining to the crisis in the Swedish Academy. This subject was chosen as an example of a big media event that had recently taken place in Sweden. The starting point of the crisis came in the wake of the #MeToo movement, with an article published in the Swedish daily newspaper Dagens

Nyheter (DN) in November 2017, wherein 18 women accused a man married to one of

the members of the Swedish Academy of sexual abuse. This article set off a series of events that led to severe conflicts between Academy members and culminated with the resignation of Permanent Secretary Sara Danius in April 2018, as well as several other members leaving the Academy.

The articles for this study were selected from the six Swedish newspapers that, according to the 2018 Orvesto Consumer Report (Kantar Sifo, 2019), had the most readers in 2018: DN, Svenska Dagbladet (SvD), Göteborgs-Posten (GP), Sydsvenskan,

Aftonbladet, and Expressen (including printed and digital versions; free papers such

as Metro and the newspaper Dagens Industri were excluded). Through the media data-base Mediearkivet (Retriever, n.d.), articles from these six papers, published in 2018 and including the phrase “Svenska Akademien” [Swedish Academy], were retrieved, resulting in 2,453 articles (including printed press and digital articles). This study only included the 1,710 printed articles, due to the fact that digital articles about the Academy published in 2018 were only included for DN and Sydsvenskan in the database, and that many digital articles were the same as the printed versions.

Only a few articles about the Swedish Academy were found from January through March, whereas April and May included the most articles on this topic (587 and 218, respectively). During 2018, DN published the most extensively about the Swedish Academy (414 printed articles), followed by SvD (370), Expressen (322), Aftonbladet (251), Sydsvenskan (192), and GP (161).

All printed articles starting from 1 January 2018 about the Academy were analysed, and relevant news articles excerpted. Nonrelevant examples included all non-news ar-ticles, instances where the Academy was not the main topic of the article, articles about the Academy’s dictionary, and articles entirely written by the Swedish news agency TT Nyhetsbyrån. First-page notes were also excluded (since the topic was repeated in lengthier articles within the main body of the paper).

In GP and Sydsvenskan, only a handful of relevant articles were found from the period January–May (because most news pieces about the crisis were originally from TT Nyhetsbyrån), despite significant coverage of the crisis in the other four newspapers. In light of this finding, GP and Sydsvenskan were excluded from the rest of the study.

Relevant articles from DN, SvD, Aftonbladet, and Expressen were excerpted in chronological order from January to mid-May until the sample reached 30 news articles from each of the four newspapers (i.e., 120 articles total). Overall, 635 articles about the Academy were analysed in order to collect the final sample.

All instances of quotations and reports attributed to other media or to older articles from the same newspaper were coded in the 120 articles. Attributions to press releases were also included in this process, because press releases were normally used in the same way as other media (offering quotes to be reproduced within new articles). Furthermore, in some cases, press releases were quoted directly by one newspaper and second-hand by another (not attributed to the press release but to another media). Thus, if press releases

had been excluded, the exact-same quote would have been included in some instances and not in others. In addition, some newspapers mentioned “statements” published on the homepage of the Swedish Academy or the Swedish Royal Court, whereas other newspapers attributed the same quote to a press release. Since press releases were pub-lished on the homepages of the two organisations, quotations and reports attributed to these homepages were also included.

Among the instances attributed to other media or to older articles from the same newspaper, the number of words in recycled direct quotations were counted. Direct quotations included statements marked with quotation marks (“ ”), a dash (–), or pre-ceded by a colon (:). Reporting clauses that informed the reader of the source of the quotation were not included. An example is given in extract [1], from an article in DN wholly dedicated to relating the content of a radio show in which Academy member Horace Engdahl had been interviewed. The words counted as recycled direct quotations have been underlined.2

[1] In the interview, Horace Engdahl’s own relationship with the so-called Culture Profile and the public quarrels with other members were discussed, among other things. For instance, he was asked about an interview with Björn af Kleen in DN two years ago, where Engdahl paid tribute to the so-called Culture Profile with the words: “He lives the good life, he is almost alone in that, the only one who has sense enough.”

– That statement was made two years ago, before the charges were made, and what I said was not about sex. It’s a topic I never discussed with [the name of the Culture Profile], we guys don’t talk about such things. (DN, 25 April 2018: 3)

In addition to counting the number of words in recycled direct quotations, I sorted the sample into three types according to to what extent they included recycled material: 1. articles that included (almost) no quotations or reports attributed to other media; 2. articles in which all statements from persons interviewed were found in quotations

or reports attributed to other media;

3. and articles that included a combination of statements from new interviews and quotations or reports attributed to other media.

Since most of the analysed articles included at least one statement attributed to other media, type 1 articles (with no – or little – recycling) could include quotations or re-ports attributed to other media, up to 10 per cent of the words. Without this exception, some extensive articles would have been classified as type 3 (articles that combine new interviews with statements attributed to other media) only because of a single short quotation taken from other media, despite the fact that almost all of the statements were from new interviews.

Moreover, the sources of quotations and reports were noted. In cases where several texts from the same source had been used in one single article, the source was counted as many times as the number of texts used; for example, if two different programmes from Sveriges Radio (SR) – Sweden’s national publicly funded radio broadcaster – were quoted, SR was counted twice.3

Results

In the following two sections, the results of the study are related. In the first section, the amount of recycled quotations are described. In the second, the sources used in the articles are presented.

The amount of quotations recycled in the articles

In total, the 120 analysed articles – written by 77 identified and 5 anonymous journalists – amounted to 64,100 words.4 Of these, 10,215 words were found in quotations from statements attributed to older texts; that is, on average, 16 per cent of the words in the articles were recycled quotations. In 24 of the 120 articles, there were no recycled quota-tions at all, while in 5 of the articles, the proportion of reused quotaquota-tions was more than 50 per cent of the words (at the most, 60%). Aftonbladet recycled the most quotations (21% of the words), while SvD recycled the least (12%) (see Table 1).

Table 1. Amount and share of recycled quotations

Newspaper

Number of words in recycled quotations

Recycled quotations as shares of the total number of words (per cent)

Aftonbladet 2,683 21

Dagens Nyheter 3,158 16

Expressen 2,427 16

Svenska Dagbladet 1,947 12

Total/Average 10,215 16

Comments: Only quotations attributed to other media or to older articles within the same media are included.

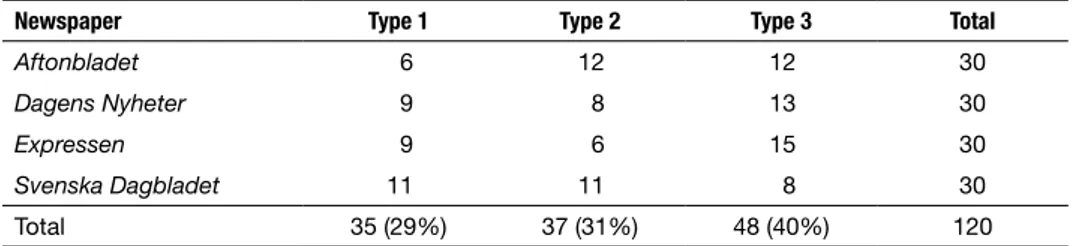

My analysis of the extent of recycling in the 120 news articles reveals that the number of articles including (almost) no quotations or accounts attributed to other media (type 1) was similar to the number in which all statements from persons involved in the events were attributed to other media (type 2). However, the most common pattern was for the articles to combine new interviews with statements attributed to other media (type 3). Table 2. Distribution of article types

Newspaper Type 1 Type 2 Type 3 Total

Aftonbladet 6 12 12 30

Dagens Nyheter 9 8 13 30

Expressen 9 6 15 30

Svenska Dagbladet 11 11 8 30

Total 35 (29%) 37 (31%) 48 (40%) 120

Comments: Type 1 articles have (almost) no quotations or accounts attributed to other media; type 2 articles have all statements from

interviewees in quotations or reports attributed to other media; type 3 articles include a combination of statements from new interviews and quotations or reports attributed to other media.

Table 2 demonstrates that in 48 of the articles (40%), new interviews were used together with recycled statements from other media sources; in some cases, both the new and recycled statements were from the same person. In excerpt [2], the Swedish Royal

Court’s head of information Margareta Thorgren is quoted both in a statement made for the newspaper in question (Aftonbladet) and from a comment made to another newspaper (DN). The media quoted is highlighted in bold, and words counted as recycled direct quotations are underlined:

[2] – The king should not, and does not have, any views on the Academy’s internal work. His main interest as the protector of the Academy is that they can continue their work, Margareta Thorgren says to Aftonbladet.

According to a source that DN has spoken to, the Court thinks that the Academy’s statement is “below all criticism”.

– They try to insinuate that the king has had his part in the game and try to pull the king into their gang, the source tells the newspaper.

Margareta Thorgren denies a scenario where the king dissolves the Swedish Academy.

– This has not been in question, she tells DN. (Aftonbladet, 14 April 2018: 6)

In the four newspapers, recycling sometimes led to quite different interpretations of the original message. Compare the following examples from passages quoting a radio programme where phrases included in only some of the papers have been highlighted in bold:

[3] – I do not want to say it was the king’s advice. It was the conversation with the king that lasted for an hour that led to this within me. It’s really what came

after the conversation, but we shared approximately the same analysis, Olsson

told P1 Morning. (DN, 14 April 2018: 10)

[4] – I do not want to say it was the king’s advice, but it was the conversation with the king that lasted for an hour that led to this within me. But we shared the same analysis, Anders Olsson told SR. (Aftonbladet, 14 April 2018: 6)

[5] – I do not want to say it was the king’s advice, but it was the conversation with the king that led to this. We shared the same analysis, Anders Olsson said. (SvD, 14 April 2018: 38)

[6] – The conversation with the king that lasted for an hour, that led to this [sic]. We shared the same analysis, he said. (Expressen, 14 April 2018: 15)

The quote published in DN is almost verbatim to the statement made by Anders Olsson in the radio programme. In the other three articles, however, some or all of the hedg-ing phrases were excluded, thereby attributhedg-ing much more responsibility to the khedg-ing’s involvement in the events.

Excerpts [3] – [6] also demonstrate that it was common for the newspapers to quote the same sources. In fact, some quotations were used again and again in the articles, es-pecially when background information was given to new events. A typical example of this is a statement made by Academy member Horace Engdahl about Sara Danius being “the worst secretary of the Academy since 1786”, which was repeated in numerous articles.

The sources used in the articles

Within the 120 articles, there were 256 cases of reported or quoted texts attributed to other media or press releases (every recycled text was counted only once per article). Thus, on average, the newspapers used more than two older texts attributed to other media in every article.

Table 3 lists the ten sources most often recycled in the analysed articles and which were used for 221 of the 256 cases (86%) of reported or quoted texts.

Table 3. Most used sources of recycled quotations and reports

Source DN SvD Afton-bladet pressenEx- Total

Dagens Nyheter – 13 19 18 50 Svenska Dagbladet 17 – 7 12 36 TT Nyhetsbyrånª 9 11 7 6 33 Sveriges Television 5 2 6 12 25 Sveriges Radio 3 5 9 4 21 Expressen 8 4 4 – 16

Press releases from the Swedish Academyb 3 7 6 0 16

Aftonbladet 5 1 – 5 11

Press releases from the Nobel Foundation 2 3 1 1 7

Press releases from the Swedish Royal Courtb 1 2 2 1 6

Total 53 48 61 59 221

Comments: ª The number includes quotations and reports from TT Nyhetsbyrån, not entire articles (entire articles from TT Nyhetsbyrån

reproduced within the newspapers were not included in the study).

b A couple of attributions to messages published on the homepages of the Swedish Academy and the Swedish Royal Court were also

inclu-ded, since other newspapers referred to the same messages as press releases.

As demonstrated in Table 3, DN was the most popular source among the analysed newspapers during the crisis, followed by SvD and TT Nyhetsbyrån. Sveriges Television [Swedish Public Service Television] (SVT) and SR were also popular sources. There are no substantial differences between the newspapers in this respect: they all used DN the most and SvD to a great extent, although Aftonbladet seems to favour SR over SvD, and Expressen recycled information from SVT as often as SvD. However, a much larger study than the present one is needed in order to draw any conclusions about such differ-ences in preferred sources between the newspapers.

Press releases from the Swedish Academy, the Nobel Foundation, and the Swedish Royal Court were also important sources for the newspapers in relating information about the crisis. Information from social media, on the other hand, was not recycled very often: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and two different blogs were used as sources 14 times in total. Furthermore, when social media was used as a source, it was never the only source in an article. Content attributed to social media in the newspapers was always reproduced quotations, similar to extract [7], where Twitter and Instagram were used as sources for quotations from politician Annie Lööf and Academy member Peter Englund:

[7] “The strong woman who tried to clean up the Swedish Academy is forced away. In fact, I am completely speechless. Completely unworthy handling. But Danius leaves with honour”, Annie Lööf wrote on Twitter the evening before last. [...] The Academy member Peter Englund, who has left the Academy, writes on

Ins-tagram that the tie blouse “was a little cramped, but possible to squeeze into!”

(Aftonbladet, 14 April 2018: 9)

A problematic aspect concerning the extensive recycling of texts became apparent from one of the non-news articles encountered during the data collection stage of news pieces for the study. The first half of the article, which is a correction of another article, is presented in excerpt [8]:

[8] In parts of SvD’s edition yesterday, it was stated that Sara Danius had demanded that Katarina Frostenson depart from the Swedish Academy if she herself were to retire. But there is no evidence that such a requirement was asserted. The source of the mistake was a misreading of a text message that the member Sara Stridsberg sent to DN, which read: “The deal in the Academy was that Katarina Frostenson leaves her job in the Academy, not her place, if Sara Danius retires as Permanent Secretary. I cried at the meeting”. (SvD, 14 April 2018: 39)

The misinterpretation made by the journalists of SvD resembles the “telephone game”, when a message passes through several individuals and the risk of misunderstanding is great. In this case, Academy member Sara Stridsberg sent a text message to DN, which published the message in an article, and journalists at SvD apparently misunderstood the message and published a misinterpretation of it.

The sources of recycled quotations and accounts were usually explicitly stated in the articles, but there are some exceptions. For example, in Expressen, the text message mentioned in [8] was reproduced without any attribution to DN at all, stating only that this is what Sara Stridsberg “writes in a text message”. Similar examples of stealing are not common, but since they are not attributed to another media source, they have neither been included in the word count for quotations nor in the analysis of used sources; thus, the newspapers use other media somewhat more extensively than the numbers presented in this article suggest.

Conclusions

In this article, I aimed to describe to what extent and how the four biggest newspapers in Sweden recycled statements originally published by other media in 120 print articles about the crisis of the Swedish Academy in 2018. A conclusion to be drawn from the study is that the newspapers used other media extensively and often combined new interviews with recycled statements attributed to other media. Also of note is that DN was the most popular source for reports and quotes attributed to other media, followed by SvD and TT Nyhetsbyrån, and that press releases were used more often than social media as sources; that is, the Swedish print articles showed a similar pattern to Finnish and Greek online news media, preferring content from other (mainstream) media, news agencies, and press releases (Manninen, 2017; Saridou et al., 2017).

A sample of 120 articles cannot be taken to represent all of Swedish journalism today; furthermore, the crisis in the Swedish Academy was a rather special case, involving several strong-minded persons disagreeing with one another. This soap-opera quality probably made newspapers more prone to quote statements by Academy members found in other media. Moreover, the small number of people at the centre of the crisis might have made it particularly difficult to find original material to pub-lish. All of this makes the results of the study difficult to generalise to Swedish news practices. A larger investigation incorporating more diverse news articles would be needed in order to be able to draw any general conclusions. Rather than painting a universal picture of recycling, the present study gives insight into the extremes of the phenomenon, thereby raising some important questions about what journalism is and what we want it to be in the future.

Lund (2001: 41) noted that “it is a lot easier (and cheaper) to update news material that has already been partially digested by other professionals, than to jump into the bewilder-ing world out there and hunt for original material”. This is what churnalism practices are about (e.g., Witschge & Nygren, 2009). In the articles about the Swedish Academy, the newspapers not only reported on the same events, but often used the exact same words, since quotations from Academy members were circulated in all papers. Hence, it did not matter if you read DN or Aftonbladet – you received much the same information.

This might sound like a positive outcome, considering that the “editorial aim of most mass media is that their readers, listeners or viewers should be kept informed of all the major events of the day, and so will need to consult one media source only” (Lund, 2001: 39). But such recycling of the exact-same material is also problematic, as it may lead to a loss of diversity and the emergence of “a culture of self-referentiality” (Martin, 2015: 88), not to mention the risks of misinterpretation and of fake news be-ing distributed widely. Lewis and colleagues (2008a) even go as far as proclaimbe-ing that the trend of journalists relying on “pre-packaged material” results in “the decline of independent journalism” (42), and that “the quality of information in a democratic society is steadily impoverished” (43). Hendrickx (2019: 13) also points out that small media markets (such as the Flemish) are especially vulnerable to “the erosion of news diversity, viewpoint diversity and opinion diversity”, since the number of legacy media is limited, resulting in recycling being more harmful for the freedom of the press (and in the end for society and democracy) than in bigger media markets. This is probably also true for the situation in Sweden.

In a Danish study, a lot of the recycled material was not attributed to the original source, but rather passed off as new information (Willig & Lund, 2009); however, this pattern was not replicated in Norwegian media (Erdal, 2010). Pieces of texts stolen from other media without attribution were not included in the present study, but analysing 120 articles in depth and examining more than 500 additional articles more briefly, I may conclude with some confidence that the original sources of quotations and reports were usually (though not always) revealed. This may be an area where journalistic practices have changed somewhat recently; current discussions regarding fake news may have made the importance of stating the source of non-original material more accentuated than before.

In the study by Gulyas (2017), 27 per cent of Swedish journalists reported that they published a story from information found in social media at least once a week. In the

articles analysed here, however, social media were not used very often, and never as the main information source (cf. Paulussen & Harder, 2014, who found similar results in a study on Belgian newspapers). Instead, social media – blogs, Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram – were used in the same way interviews recycled from other media were: to gather comments from people involved in the events to quote in new articles, usually together with other recycled material (i.e., the illustrative function most common for tweets in a study by Broersma & Graham, 2013).

The quotations recycled from social media in the analysed articles were all from “elite” individuals: Academy members, politicians, authors, and journalists. Thus, the democratic potential of social media in making more voices heard pointed out by some researchers (e.g., Brandtzaeg & Chaparro Domínguez, 2018; Picard, 2014) might be somewhat overrated. Furthermore, social media platforms make it possible for this elite group to have more control over the way they are represented in media than before. Broersma and Graham (2013) argue that the “negotiation-through-conversation” that previously took place between sources and journalists is bypassed when reporters rely on social media, thereby altering the power relations between them and their sources. In the Academy crisis, this pattern was evident when Academy members Peter Englund and Sara Danius felt they had been misunderstood by the media. They did not write debate pieces for newspapers that could be edited by several journalists before being published; instead, they communicated directly with the public by writing disclaimers on blogs and Facebook, knowing that the information would be picked up by the legacy media (cf. Schifferes et al., 2014). In this way, social media do empower some people, but likely not as much of the general public as some researchers hope.

Funding

The study was funded by a grant from Wahlgrenska stiftelsen.

Notes

1. See http://om.omni.se/.

2. All translations were made by the author of this article. For the original Swedish texts, see the Appendix. 3. “Text” is here used broadly, extending to both written material and conversations in television shows

and radio programmes (cf. Karlsson, 2007).

4. Pieces of texts that accompany images, as well as billboards, were excluded from the study.

References

Allern, S., & Pollack, E. (2019). Journalism as a public good: A Scandinavian perspective. Journalism, 20(11), 1423–1439. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884917730945

Bakker, P. (2012). Aggregation, content farms and Huffinization. Journalism Practice, 6(5–6), 627–637. https://www.doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2012.667266

Boczkowski, P. (2010). News at work: Imitation in an age of information abundance. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Boumans, J. (2018). Subsidizing the news? Organizational press releases’ influence on news media’s agenda and content. Journalism Studies, 19(15), 2264–2282. https://www.doi.org/10.1080/146167 0X.2017.1338154

Brandtzaeg, P. B., & Chaparro Domínguez, M. Á. (2018). A gap in networked publics? A comparison of younger and older journalists’ newsgathering practices on social media. Nordicom Review, 39(1), 95–109. https://doi.org/10.2478/nor-2018-0004

Broersma, M., & Graham, T. (2013). Twitter as a news source: How Dutch and British newspapers used tweets in their news coverage, 2007–2011. Journalism Practice, 7(4), 446–464. https://www.doi.org/1 0.1080/17512786.2013.802481

Cagé, J., Hervé, N., & Viaud, M.-L. (2019). The production of information in an online world. The Review of Economic Studies, 1–39. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdz061

Coddington, M. (2019). Aggregating the news: Secondhand knowledge and the erosion of journalistic author-ity. New York: Columbia University Press.

Davies, N. (2009). Flat Earth news: An award-winning reporter exposes falsehood, distortion and propaganda in the global media. London: Vintage. (Original work published 2008)

Erdal, J. (2010). Hvor kommer nyhetene fra? [Where does the news come from?] In Norges offentlige utred-ninger, (2010: 14), Lett å kommet til orde, vanskelig å bli hørt – en moderne mediestøtte [Easy to talk, difficult to get listened to – a modern media support system] (pp. 129–137). Retrieved October 2, 2019, from https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/nou-2010-14/id628603/sec13

Gulyas, A. (2017). Hybridity and social media adoption by journalists. Digital Journalism, 5(7), 884–902. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2016.1232170

Hedman, U., & Djerf-Pierre, M. (2013). The social journalist. Digital Journalism, 1(3), 368–385. https://doi. org/10.1080/21670811.2013.776804

Hendrickx, J. (2019). Trying to survive while eroding news diversity: Legacy news media’s catch-22. Journal-ism Studies, 1–17. Advance online publication. https://www.doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2019.1694430 Jackson, D., & Moloney, K. (2016). Inside churnalism: PR, journalism and power relationships in flux.

Jour-nalism Studies, 17(6), 763–780. https://www.doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2015.1017597

Johnston, J., & Forde, S. (2017). Churnalism: Revised and revisited. Digital Journalism, 5(8), 943–946. https://www.doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1355026

Kantar Sifo. (2019). ORVESTO Konsument 2018 Helår [ORVESTO Consumer 2018 Full Year]. Retrieved Oc-tober 4, 2019, from https://www.kantarsifo.se/rapporter-undersokningar/orvesto-konsument-2018-helar Karlsson, A.-M. (2007). Multimodalitet, multisekventialitet, interaktion och situation: Några sätt att tala om

”vidgade texter” [Multimodality, multi-sequentiality, interaction and situation: Some ways of speaking about “extended texts”]. In B. L. Gunnarsson, & A.-M. Karlsson (Eds.), Ett vidgat textbegrepp [An extended text concept] (pp. 20–26). Uppsala: Uppsala University.

Lewis, J., Williams, A., & Franklin, B. (2008a). Four rumours and an explanation: A political economic ac-count of journalists’ changing newsgathering and reporting practices. Journalism Practice, 2(1), 27–45. https://www.doi.org/10.1080/17512780701768493

Lewis, J., Williams, A., Franklin, B., Thomas, J., & Mosdell, N. (2008b). The quality and independence of British journalism: Tracking the changes over 20 years. Cardiff, UK: Cardiff School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies.

Luengo, M. (2014). Constructing the crisis of journalism. Journalism Studies, 15(5), 576–585. https://doi.or g/10.1080/1461670X.2014.891858

Lund, A. B. (Ed.) (2000). Først med det sidste: en nyhedsuge i Danmark [First with the latest: A week of news in Denmark]. Århus: Ajour.

Lund, A. B. (2001). The genealogy of news: Researching journalistic food-chains. Nordicom Review, 22(1), 37–42. https://doi.org/10.1515/nor-2017-0342

Lund, A. B., Willig, I., & Blach-Ørsten, M. (Eds.) (2009). Hvor kommer nyhederne fra? Den journalistiske fødekæde i Danmark før og nu [Where does the news come from? The journalistic food-chain before and now]. Århus: Ajour.

Manninen, V. (2017). Sourcing practices in online journalism: An ethnographic study of the formation of trust in and the use of journalistic sources. Journal of Media Practice, 18(2–3), 212–228. https://doi.org/10 .1080/14682753.2017.1375252

Martin, F. (2015). The case for curatorial journalism... or, can you really be an ethical aggregator? In D. Craig, & L. Zion (Eds.), Ethics for digital journalists: Emerging best practices (pp. 87–102). New York: Routledge.

Martinsson, J., & Andersson, U. (Eds.) (2018). Svenska trender 1986–2017 [Swedish trends 1986–2017]. Gothenburg: SOM Institute, University of Gothenburg.

Moloney, K., Jackson, D., & McQueen, D. (2013). News journalism and public relations: A dangerous relation-ship. In K. Fowler-Watt, & S. Allan (Eds.), Journalism: New Challenges (pp. 259–281). Bournemouth, UK: Centre for Journalism & Communication Research, Bournemouth University.

Nygren, G., Leckner, S., & Tenor, C. (2018). Hyperlocals and legacy media: Media ecologies in transition. Nordicom Review, 39(1), 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1515/nor-2017-0419

Paulussen, S., & Harder, R. A. (2014). Social media references in newspapers: Facebook, Twitter and YouTube as sources in newspaper journalism. Journalism Practice, 8(5), 542–551. https://www.doi.org/10.108 0/17512786.2014.894327

Phillips, A. (2010). Old sources: New bottles. In N. Fenton (Ed.), New media, old news: Journalism and democracy in the digital age (pp. 87–101). Los Angeles: Sage.

Picard, R. G. (2014). Twilight or new dawn of journalism? Journalism Studies, 15(5), 500–510. https://doi. org/10.1080/1461670X.2014.895530

Retriever. (n.d.). Mediearkivet [database with Swedish newspapers]. Retrieved October 17, 2019, from https:// www.retriever.se/product/mediearkivet

Saridou, T., Spyridou, L.-P., & Veglis, A. (2017). Churnalism on the rise? Assessing convergence effects on editorial practices. Digital Journalism, 5(8), 1006–1024. https://www.doi.org/10.1080/21670811.201 7.1342209

Schifferes, S., Newman, N., Thurman, N., Corney, D., Göker, A., & Martin, C. (2014). Identifying and veri-fying news through social media. Digital Journalism, 2(3), 406–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/2167081 1.2014.892747

Thurman, N., & Myllylahti, M. (2009). Taking the paper out of news: A case study of Taloussano-mat, Europe’s first online-only newspaper. Journalism Studies, 10(5), 691–708. http://dx.doi. org/10.1080/14616700902812959

Van Leuven, S., Deprez, A., & Raeymaeckers, K. (2014). Towards more balanced news access? A study on the impact of cost-cutting and web 2.0 on the mediated public sphere. Journalism, 15(7), 850–867. https:// www.doi.org/10.1177/1464884913501837

von Nordheim, G., Boczek, K., & Koppers, L. (2018). Sourcing the sources: An analysis of the use of Twitter and Facebook as a journalistic source over 10 years in The New York Times, The Guardian, and Süd-deutsche Zeitung. Digital Journalism, 6(7), 807–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2018.1490658 Vonbun-Feldbauer, R., & Dogruel, L. (2018). Regional newspapers’ sourcing strategies: Changes in media-ci-tation and self-cimedia-ci-tation from a longitudinal perspective. Journalism, 1–19. Advance online publication. https://www.doi.org/10.1177/1464884918817639

Wahl-Jorgensen, K., Williams, A., Sambrook, R., Harris, J., Garcia-Blanco, I., Dencik, L., Cushion, S., Carter, C., & Allan, S. (2016). The future of journalism: Risks, threats and opportunities. Digital Journalism, 4(7), 809–815. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2016.1199469

Wheatley, D., & O’Sullivan, J. (2017). Pressure to publish or saving for print? A temporal comparison of source material on three newspaper websites. Digital Journalism, 5(8), 965–985. https://www.doi.org/ 10.1080/21670811.2017.1345644

Willig, I., & Lund, A. B. (2009). Publicistisk produktion: Sådan gør man nåheder til nyheder [Publicistic production: How to turn non-news into news]. In A. B. Lund, I. Willig, & M. Blach-Ørsten (Eds.), Hvor kommer nyhederne fra? Den journalistiske fødekæde i Danmark før og nu [Where does the news come from? The journalistic food-chain before and now] (pp. 163–178). Århus: Ajour.

Witschge, T., & Nygren, G. (2009). Journalistic work: A profession under pressure? Journal of Media Business Studies, 6(1), 37–59. https://www.doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2009.11073478

Copyright: © 2020 The Author(s) and Nordicom. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

Appendix: Original Swedish texts

[1] I intervjun diskuterades bland annat Horace Engdahls egen relation till den så kallade Kulturprofilen och de offentliga bråken med andra ledamöter. Bland annat ställdes frågan om en intervju med Björn af Kleen i DN för två år sedan, där Engdahl hyllade den så kallade Kulturprofilen med orden: ”Han lever det goda livet, han är nästan ensam om det, den ende som har förstånd.”

– Det uttalandet gjordes för två år sedan innan anklagelserna hade framförts, och det jag sa handlade inte om sex. Det är ett ämne jag aldrig diskuterat med XX [nam-net på Kulturprofilen], vi grabbar pratar inte om sådant. (DN, 25 April 2018, p. 3) [2] – Jag vill inte säga att det var kungens råd. Det var samtalet med kungen som pågick i en timme som ledde fram till det här inom mig. Det är egentligen det som kom efter samtalet, men vi delade ungefär samma analys, sa Olsson till P1 Morgon. (DN, 14 April 2018, p. 10)

[3] – Jag vill inte säga att det var kungens råd, men det var samtalet med kungen som pågick i en timme som ledde fram till det här inom mig. Men vi delade samma analys, sa Anders Olsson till SR. (Aftonbladet, 14 April 2018, p. 6)

[4] – Jag vill inte säga att det var kungens råd, men det var samtalet med kungen som ledde fram till det här. Vi delade samma analys, sa Anders Olsson. (SvD, 14 April 2018, p. 38)

[5] – Samtalet med kungen som pågick i en timme, som ledde fram till detta [sic]. Vi delade samma analys, sa han. (Expressen, 14 April 2018, p. 15)

[6] ”Den starka kvinna som försökt städa upp i Svenska Akademien tvingas bort. Jag är faktiskt helt mållös. Fullständigt ovärdig hantering. Men Danius går med högt huvud”, skrev Annie Lööf på Twitter i förrgår kväll. […]

Avhoppade ledamoten Peter Englund skriver på Instagram att knytblusen ”var lite trång, men den gick på!” (Aftonbladet, 14 April 2018, p. 9)

[7] – Kungen ska inte, och har inte, synpunkter på Akademiens interna arbete. Hans främsta intresse som beskyddare är att de kan fortsätta sitt arbete, säger Margareta Thorgren till Aftonbladet.

Enligt en källa som DN har talat med tycker hovet att Akademins uttalande är ”under all kritik”.

– De försöker insinuera att kungen har haft sin del i spelet och försöker dra in kungen i deras mansgäng, säger källan till tidningen.

Margareta Thorgren förnekar ett scenario där kungen upplöser Svenska Akad-emien.

[8] I delar av SvD:s upplaga i går uppgavs att Sara Danius hade krävt Katarina Frostensons avgång för att själv lämna Svenska Akademien. Men det finns inga belägg för att något sådant krav ställdes. Källan till misstaget var en felläsning av ett sms som ledamoten Sara Stridsberg skickat till DN och som löd: ”Dealen i Akademien var att Katarina Frostenson lämnar arbetet i Akademien, inte sin plats, om Sara Danius lämnar som ständig sekreterare. Jag grät på mötet”. (SvD, 14 April 2018, p. 39)