Oral Health Care among European

Native and Immigrant’s Children

and Adolescents:

A systematic review and meta-analysis

By: Akikun Nahar

Supervisor: Patrik Dinnetz

Södertörn University | School of Natural sciences, Technology and Environmental Studies

Master’s dissertation 30 credits

Environmental Science, spring semester 2021 Programme Infectious Disease Control

Tandhälsovård bland europeiska barn och ungdomar,

infödda eller immigranter: En systematisk granskning

och meta-analys

Oral Health Care among European Native and

Immigrant’s Children and Adolescents:

Table of Contents

ABBREVIATIONS ... 3

Abstract ... 4

Burden of oral diseases ... 6

Oral health care in Europe ... 7

OBJECTIVES ...8

MATERIALS AND METHODS ... 8

Search strategy ...9

Data extraction ... 10

Type of outcome measures ... 10

Statistical analysis ... 10

RESULT ... 12

DISCUSSION ... 24

CONCLUSION ... 27

ABBREVIATIONS

DMFT Decayed Missing and Filled Teeth index MeSH Medical Subject Headings

OR Odds Ratio

WHO World Health Organization

NCHS National Centre for Health Statistics SSB sugar-sweetened beverage

Key words

Abstract

Background: Globally, oral health remains a public health concern, particularly in relation to well-being of children and adolescents. Dental caries, one of the most common oral health problem in this group, is considered as a transmissible, infectious disease with significant health consequences. Migration in Europe has increased over the recent years due to geopolitical causes, employment, family reunion, and so forth. Earlier studies show that immigrant

populations in Europe have a higher rate of oral problems, and are at higher risk to oral diseases. This review aims to evaluate oral health status among children and adolescents with immigrant and native backgrounds and to evaluate if there are disparities in oral health between these two groups.

Methods: This study involved a systematic review of research articles comparing oral health between native European and immigrant children and adolescents. MeSH terms and key words comprised oral health, Europe, dental care, disparities, immigrant, environment, social and cultural, mouth care, children and adolescent. An open-access, validated tool was used to perform meta-analysis.

Results: 15 studies were eligible for inclusion in the systematic review; 6 of which reported differences in mean Decayed Missing Filled teeth index (DMFT) scores, 7 reported odds ratios (OR) and two studies reported prevalence. The combined effect size for the DMFT scores was 0.54 (95% CI: 0.35 – 0.73), indicating a statistically significant difference of 46% in the mean DMFT scores between natives and immigrants, with the former having lower DMFT scores. The combined effect size for studies yielding ORs was 4.12 (95% CI: 2.51-6.78); implying 4-fold higher odds of dental caries among immigrants. Significant heterogeneity among the studies were observed. The likelihood of publication bias was also high.

Conclusion: This review captured higher risk of dental caries, plaque formation and staining on teeth among immigrant than native children and adolescents in Europe. However, the studies included did not have the scope to examine potential causes for such a gap; which is an important knowledge gap to be addressed in future.

INTRODUCTION

Oral health is an integral aspect of holistic wellbeing. Moreover, oral health is of greatest

importance when it comes to health status of children and adolescents. Dental caries, considered to be a transmissible infectious disease with multifactorial causation, leads to significant short- and long-term consequences (Çolak et al., 2013). Interestingly, there is a remarkable social gradient associated with the status of oral health of populations, very similar to what has been observed and documented in general health (Sgan-Cohen, Harold and Mann, 2007). Despite major improvement in oral health services globally, shortcomings remain at community level, particularly among underprivileged groups in developed as well as developing countries

(Petersen, 2003). One National Centre for Health Statistics (NCHS) data brief in 2012 revealed that among children and adolescents aged 5-19 years in the United States, those belonging to poor or ethnic minority families had higher rates of untreated dental caries in comparison to their counterparts from wealthier non-minority families (Dye, Li and Beltran-Aguilar, 2012). There is ample evidence in the literature of the existence of social gradients in various aspects of oral health (Marmot and Bell, 2011). On top of that, potential barriers in accessing oral health care in host countries can affect oral health of children and adolescents from immigrant families.

Despite that immigrant populations have been an important focus of public health research for several years, studies examining oral health status among immigrants’ children and adolescents from the perspective of equity and social determinants of health perspective are relatively few.

Many developed countries have introduced regular dental health care for the residents particularly for children and adolescents (Skeie and Klock, 2018) irrespective of their residency status. This has not always been translated into optimum utilization by children and adolescents from all strata of the society (Petersen and Kwan, 2011). Consequently, the burden of oral diseases in developed countries fall disproportionately on the disadvantaged part of populations including urban poor, minority families, refugees, and immigrants. Lower utilization of dental care among these populations could reflect their prioritization of needs or lack of awareness, rather than mere unwillingness to seek oral health care. On the other hand, recent evidences suggests that socio-behavioural and environmental factors play a significant role for variation in oral disease (Watt, 2005; Gupta et al., 2015). Important factors related to oral health of children and adolescents are consumption of sugary products, parental awareness and assistance in tooth-brushing, and institutional environment (e.g. a day-care centre)(Hall-Scullin et al., 2015)

(Duijster et al., 2015). Additional interplaying factors among immigrant populations relate to their lower socioeconomic status, knowledge of oral health, personal beliefs, care seeking practices and cultural influences (Dahlan et al., 2019).

There are oral diseases and non-communicable chronic diseases such as severe periodontal disease and diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis and stroke, that are interrelated and primarily a result of common risk factors (Petersen et al., 2005). Earlier studies have linked oral health status with children’s academic performance (Seirawan, Faust and Mulligan, 2012). It is also reported that oral and other diseases, can be prevented and controlled through a combination of community, professional, and individual achievements (Silva, Mendonça and Vettore, 2008). Between the years of 2005 and 2015, Europe has absorbed a staggering number of international migrants. Therefore, migration has emerged as an increasingly important phenomenon for European societies. Due to the complexity of oral health care service and long-term nature of the migrant integration process, it is challenging to minimize the inequalities to ensure good oral health for all. A systematic review pooling information from the scholarly works addressing oral health among children and adolescents in European context with a lens of comparison between native and immigrants will provide insights into any existing inequality and inform policy makers with evidence-based inputs required to formulate better policies for improvement of oral health.

Burden of oral diseases

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines oral health as “a state of being free from mouth and facial pain, oral and throat cancer, oral infection and sores, periodontal disease, tooth decay, tooth loss, and other diseases and disorders that limit an individual’s capacity in biting, chewing, smiling, speaking, and psychosocial wellbeing” (WHO, 2003). Oral disease is one of the most common public health problems, however, frequently neglected in health policy (Petersen, 2009). It is estimated that about 90% of the world’s population, during parts of their life, suffer from some form of oral diseases (Jin et al., 2016). Dental caries, a common chronic disease of childhood and periodontal disease are the most prevalent oral diseases (Petersen, 2009, Jin et al., 2016). A recent review reported that untreated caries in deciduous teeth was the 10th-most prevalent health condition in 2010 (Kassebaum et al., 2015). Moreover, oral cancer is one of the commonest cancer in adults (Johnson et al., 2011). Oral diseases are linked to chronic

diseases probably due to common risk factors (Petersen et al., 2005). For adults, poor socio economic condition including unhealthy diet and poor nutrition, physical inactivity, tobacco use, and psychosocial stress are important risk factors. For children, both in Europe and outside Europe, low parenteral education was identified as one of the main risk factors for development of caries (Cvikl et al., 2014).

Oral health care in Europe

In European countries, one difference between provision of dental care and medical care is that the cost for dental check-ups and treatment of an individual patient is considerably higher compared to medical care. Although oral health has improved significantly in Europe over the last few decades, it is still a matter of concern and is considered as a public health problem. A review reported that the Decayed Missing and Filled Teeth index (DMFT) for dental caries experience in children is higher in the European Region (DMFT = 2.6) than in most African countries (DMFT = 1.7) (Petersen et al., 2005). A recent report recommended that knowledge of prevention/oral hygiene practices and access to high quality but affordable oral health care are the key essentials to prevent oral health diseases (Patel, 2012).

In the European Union (EU), the annual expense of oral care is about €79 billion, which creates a huge economic burden on the government. Apart from being under insurance coverage, there are also out-of-pocket expenditures and indirect costs for oral health care services, which creates an economic burden, especially on the low-income groups. Individuals are also effected in terms of time lost from school, work or other activities due to dental problems and treatment (Jin et al., 2016). Thus it results in loss of substantial amount of both money and time. In the European Union, financial support for dental care vary country to country, depending on which country the individual originated from. This variation in financial support creates a higher risk for those who are either not aware of the possibility of having dental care services as part of their health package or those who cannot afford the additional expense. For example, In Sweden, there are special rules for asylum seekers to get support for dental care. However, only 38% of them had visited a dentist (Zimmerman, Bornstein and Martinsson, 1995). Studies from Norway and Sweden suggested that among the immigrants inequality in oral health results from social and cultural differences (Karlberg and Ringsberg, 2006). Factors such as discrimination and unemployment lead to lower socio-economic condition of the immigrants than that from the

natives. It was seen that the immigrants face difficulty in accessing the dental care support and thus instead of seeking preventive measures, they usually seek the services for primary care or during an emergency, such as when they are in immense pain (Patel, 2012).

Recent studies found that oral diseases such as dental caries and periodontal diseases are more prevalent in the immigrant population than the native population (Jacobsson et al., 2011, Portero de la Cruz and Cebrino, 2020). The risk of dental caries was higher in children with foreign born parents and increased progression into their adolescence, compared to children of the native-born parents (Julihn, Ekbom and Modéer, 2010).

RESEARCH QUESTION

Are there any differences in incidence of dental caries, an oral health problems and access to proper dental care in children and adolescents with immigrant and native backgrounds, in Europe?

OBJECTIVES

The objectives of this study are to:

evaluate the differences in dental caries, an oral health problem in children and adolescents with immigrant and native backgrounds, in Europe.

evaluate determinants of oral health, including access to dental care among children and adolescents with immigrant and native backgrounds.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

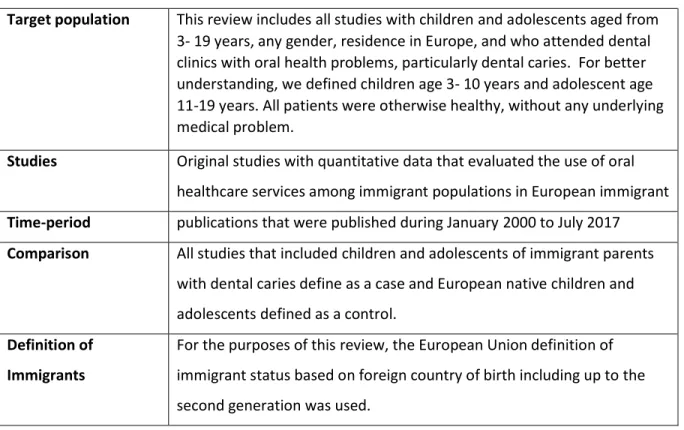

A systematic literature review was performed to identify the available evidence on children of immigrant’s dental care practices and utilization of services using predefined criteria (Table 1). Articles considering children of undocumented immigrants, asylum seekers and/or refugees were included.

Table 1. Selection criteria for studies in oral health to be included in the systematic review

Target population This review includes all studies with children and adolescents aged from 3- 19 years, any gender, residence in Europe, and who attended dental clinics with oral health problems, particularly dental caries. For better understanding, we defined children age 3- 10 years and adolescent age 11-19 years. All patients were otherwise healthy, without any underlying medical problem.

Studies Original studies with quantitative data that evaluated the use of oral healthcare services among immigrant populations in European immigrant Time-period publications that were published during January 2000 to July 2017 Comparison All studies that included children and adolescents of immigrant parents

with dental caries define as a case and European native children and adolescents defined as a control.

Definition of Immigrants

For the purposes of this review, the European Union definition of immigrant status based on foreign country of birth including up to the second generation was used.

Search strategy

To select literature on oral health specially on dental caries which addressed disparity between children and adolescents of immigrant and native parents in Europe, the National Library of Medicine (PubMed) and the Web of Science were searched for all relevant literature published in the English language spanning a period from 1st January 2000 to 31st July 2017. This time-period

was selected because the number of immigrants increased two times during his period in comparison with the period 1990-2000.

The MeSH (Medica Subject Headings) terms used in the search included “oral health”, “dental caries”, “Europe”, “dental care”, “disparities”, “immigrant”, “environment”, “social” and cultural” and “mouth care”, “children”, “adolescent”. Reference lists were also examined for pertinent articles that may have been overlooked. Studies on children and outcome measures which were dental caries or caries prevalence were included in the meta-analysis (Table 2). Studies that did not evaluate outcome based on residential status (native and immigrant) were not included in the analysis (Appendix: Table 1A.).

Data extraction

The following information was extracted from each publication that was selected for review. context of the study (country and year),

objective of the study,

characteristics of the included population (definition of immigrants), methodological components (design of the study and sample size), main results,

recommendation by authors, and

if available, confounders affecting dental care utilization (individual determinants, measures of need, socio-economic indicators, and cultural factors).

Type of outcome measures

The primary outcome was differences in children’s and adolescent’s dental caries measured by odds ratio, mean DMFT scores and the proportion of caries. Odds ratios were used by the studies to compare the relative odds of the occurrence of the dental caries between immigrant and native children and adolescents in Europe. DMFT scores has been developed by WHO and

recommended as a framework of reference to index dental caries (Khamis, 2016). The DMFT is the most commonly used epidemiological index for evaluating dental caries.

Statistical analysis

Following the structured review of the identified studies, data from individual studies was analyzed quantitatively with a meta-analysis. The meta-analysis was done to test the

generalizability of results across identified quantitative studies and to obtain a single summary estimate of the effect to evaluate dental caries in children and adolescents with immigrant and native backgrounds in Europe. It was also used to evaluate whether studied findings are

consistent or not, and if not consistent, then to assess the differences among the studies, in terms of study characteristics such as use of measures, same exposure or not, study design, and

participants’ characteristics. To understand the nature of variability in studies, we tested the heterogeneity and evidence of publication bias. Cochran’s Q (Q-value), and I2 values examined

bias. While confidence interval takes into account the uncertainty due to sampling, prediction interval accounts for this as well as for the variability of individual observations around the estimated value (IntHout, Ioannidis and Borm, 2014).

There are some assumptions underlying such meta-analytical pooling of data: all studies included should be conducted at samples drawn from one homogenous population, the studies should be comparable, specifically in terms of effect size measures adopted in those studies (Steven J and Jerry A, 2009). Commonly pooled effect size measure includes the standardized mean

difference, the odds ratio or the Pearson correlation co-efficient. The purpose is to compute a mean effect size, which is a weighted average of the summary statistics from the individual studies reflecting the magnitude of the effect of the studied relationship or association.

The statistical techniques underlying such quantitative synthesis fall broadly into two categories, namely ‘random effect model’ and ‘fixed effect model’ (Egger et al., 1997).

Considering the plausibly higher likelihood of variations among the included studies regarding various study and sample characteristics, a ‘random effect model’ would be adopted, which takes into account a different underlying effect for each study and assumes that the effects are

randomly distributed. However, ‘random effect model’ produces somewhat wider confident intervals in comparison to ‘fixed effect model’.

The Meta-Essentials is a statistical tool for performing meta-analysis that is cost-free as well as validated. It was developed by the Erasmus Research Institute of Management

(Suurmond, van Rhee and Hak, 2017). It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 International License.

The data management required for such meta-analytical pooling was carried out in following steps:

The studies identified for this systematic review were categorized according to the reported summary statistics- either odds ratio (OR) or mean DMFT scores to compare oral health

problems between children’s of immigrant parents and natives. One meta-analysis incorporated the studies reporting ORs, and another the studies reporting mean DMFT scores. However, two studies reporting prevalence of dental caries were not included in the meta- analysis. In response to age-related stratification of the data in the studies, ORs for different age groups were treated as independent ORs and such age-specific ORs, when from the same study, contributed separate

inputs of ORs for meta-analysis. For studies that reported OR, the combined effects size were measure based on the log odds ratio analyzing the difference in log odds for having good oral health status between children of immigrants and native children. After the analyses all effect sizes shown in tables and figures were transformed to odds ratios and odds. For studies that reported DMFT mean scores, the combined effect size measured the calculated difference of DMFT mean score between children of immigrants and native children.

RESULT

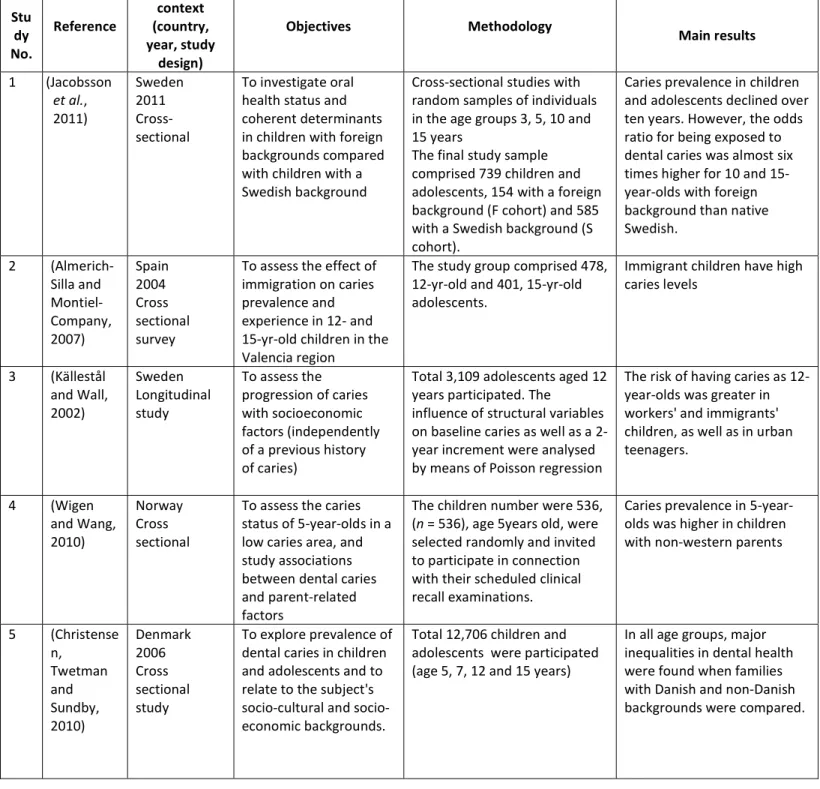

A total of 15 studies were included in this systematic review. A flow chart of the search strategy and the quantity of included and excluded literature were summarized in Figure 1. There were seven articles that presented result as odds ratio (study 1-7; Table 3), six articles that presented result in DMFT score (study 8-13; Table 4), and two studies that reported prevalence of dental caries (study 14 and 15).

The sample sizes of the included studies varied from 144 to 15,538 participants of different ages ranging from 3 to 19 years. The exposure of all cases was the same; i.e. ‘immigration

experience’, implying that the participants or both of their parents must have moved to the country of study. The comparison group consisted of native children of the same age. All fifteen included studies found a significant difference in oral health status (dental caries) between immigrant children and adolescents compared to native (Table 2), but the reason behind the differences varies. Most of the studies found that low socio-economic status was a significant predictor for dental caries in immigrant’s children. However, one Norwegian study (study no. 7, Table 2) found that dental caries was prevalent among immigrants with high socio-economic status because they have greater ability to buy sweets, soft drinks, and sticky food (Skeie et al., 2006).

Figure 1. Flow chart of literature search process for a systematic review of articles on oral health problems in immigrant and native backgrounds children and adolescents in Europe.

Studies identified at initial search: 66 (PubMed: 60 & Web of Science: 6)

Articles excluded for being duplicates or not meeting selection criteria: 20

Studies assessed for eligibility 46

Full text of studies selected after abstract review: 30

Articles excluded after full text review: 15 Articles excluded after abstract review: 16

Final selection of studies for systematic analysis after full text review: 15

Table 2: Descriptive summary of the studies included in the review Stu dy No. Reference context (country, year, study design)

Objectives Methodology Main results

1 (Jacobsson et al., 2011) Sweden 2011 Cross-sectional To investigate oral health status and coherent determinants in children with foreign backgrounds compared with children with a Swedish background

Cross-sectional studies with random samples of individuals in the age groups 3, 5, 10 and 15 years

The final study sample comprised 739 children and adolescents, 154 with a foreign background (F cohort) and 585 with a Swedish background (S cohort).

Caries prevalence in children and adolescents declined over ten years. However, the odds ratio for being exposed to dental caries was almost six times higher for 10 and 15-year-olds with foreign background than native Swedish. 2 (Almerich-Silla and Montiel-Company, 2007) Spain 2004 Cross sectional survey

To assess the effect of immigration on caries prevalence and experience in 12- and 15-yr-old children in the Valencia region

The study group comprised 478, 12-yr-old and 401, 15-yr-old adolescents.

Immigrant children have high caries levels 3 (Källestål and Wall, 2002) Sweden Longitudinal study To assess the progression of caries with socioeconomic factors (independently of a previous history of caries)

Total 3,109 adolescents aged 12 years participated. The

influence of structural variables on baseline caries as well as a 2-year increment were analysed by means of Poisson regression

The risk of having caries as 12-year-olds was greater in workers' and immigrants' children, as well as in urban teenagers. 4 (Wigen and Wang, 2010) Norway Cross sectional

To assess the caries status of 5-year-olds in a low caries area, and study associations between dental caries and parent-related factors

The children number were 536, (n = 536), age 5years old, were selected randomly and invited to participate in connection with their scheduled clinical recall examinations.

Caries prevalence in 5-year-olds was higher in children with non-western parents

5 (Christense n, Twetman and Sundby, 2010) Denmark 2006 Cross sectional study To explore prevalence of dental caries in children and adolescents and to relate to the subject's cultural and socio-economic backgrounds.

Total 12,706 children and adolescents were participated (age 5, 7, 12 and 15 years)

In all age groups, major inequalities in dental health were found when families with Danish and non-Danish backgrounds were compared.

Table 2: Descriptive summary of the studies included in the review Stu dy No. Reference context (country, year, study design)

Objectives Methodology Main results

6 (Hjern and Grindefjor d, 2000)

Sweden

2010 To describe access to dental care in a population-based sample of foreign born Swedish residents in relation to dental health.

The study included

2,228 children and adolescent aged 3-15 years in the minority households and 2,892 children and adolescent in the

households of the Swedish-born study group.

This study demonstrates that adults in minority populations in Sweden use less dental care despite having greater needs of dental treatment.

7 (Skeie et

al., 2006) Norway 2006 This study sought to map existing disparities in oral health among immigrant and western native children in Oslo and to identify

differences in parental, cultural and ethnic beliefs and attitudes towards oral health.

Caries was recorded of 735 children (3- and 5-year olds), supplemented with radiographs among 5-year olds.

Among immigrants,

consumption of sweet drinks at bed and social status were the dominant caries risk indicators among the 3-year olds. Among the 5-year olds, parental indulgence, attitude to diet, attitude to oral hygiene, social status and age starting tooth brushing.

8 (Enjary et al., 2006) France Cross sectional survey To examine the relationship between socioeconomic status measured as an area-based ecological variable and dental status.

All 5- 10 years old school children were included in this study.

Parents completed a questionnaire and children were examined for dental caries

Children of deprived school groups are likely to have received less dental care and to have poorer dental health.

9 (Ferro et

al., 2007) Italy Cross sectional survey

To investigate dental caries experience among preschool children aged 3-5 years and compare indigenous

and immigrant children.

Total 4,198, 3-5-year-old children participated. The participants were categorized into 2 subgroups according to the country of origin of their mothers

Inequalities associated with mothers with

an immigrant background were observed in the distribution of caries experience among the children.

10 (Bissar et

al., 2007) Germany Cross sectional survey

To evaluate the dental caries experience, the provided care, and the unmet treatment need in 11- to 13-year-old schoolchildren with immigration background compared to native children A cross-sectional study of 502 schoolchildren, 48% of which have immigration background.

Children with immigration background demonstrated more caries and received less dental care when compared to children without migration experience.

Table 2: Descriptive summary of the studies included in the review Stu dy No. Reference context (country, year, study design)

Objectives Methodology Main results

11 (Cvikl et

al., 2014) Austria 2014 To evaluate whether a higher educational level of parents can overcome risks for

the development of caries in immigrants in Vienna, Austria.

The educational level of the parents, the school type, and the caries status of 736 randomly selected twelve-year-old children with and

without migration background was determined in this cross-sectional study

Children with

a migration background are at higher risk to

acquire caries than other Viennese children, even when the parents have received a higher education. 12 (Julihn, Ekbom and Modéer, 2010) Sweden 2000 retrospective longitudinal register-based cohort study

The influence of child and parental migration background on the risk of a proximal caries increment in Swedish adolescents was investigated

13-yr-old adolescents

(n = 18,142) who were resident in the County of Stockholm, Sweden, in 2000, and followed them up to 19 years of age. logistic regression analysis was done.

Adolescents with foreign-born parents, irrespective of whether the child was born in Sweden or abroad, exhibited a significantly elevated risk for a proximal caries increment [decayed, missing or filled surface (DMFSa) values more than 0] 13 (Waltimo et al., 2016) Switzerland 2016 Cross sectional To investigate the changes

in caries experience and prevalence

among schoolchildren of the canton of Basel Landschaft, Switzerland

A random sample of

either schoolchildren aged 7, 12 , and 15 years (in 1992) or aged 12 and 15 years (in 1997) or their respective school classes (2001, 2006 and 2011) was selected so that

approximately 10% of schoolchildren could be examined.

Schoolchildren with a migrant background had approximately two- to threefold higher dmft/DMFT values. 14 (Almerich Silla, 2006) Spain 2004 Cross sectional survey

To study the evolution of child oral health in the Valencia Region, Spain

A random sample of 509 children aged 6 years, 478 aged 12 years and 401 aged 15-16 years included in the survey

Immigrant children have high caries levels 15 (Baggio et al., 2015) Switzerland 2015 Cross sectional

to define the Early childhood caries (ECC) prevalence among children living in French-speaking Switzerland

856 children were screened from 36 to 71 months old for ECC. Prevalence rates, prevalence ratios and logistic regressions were calculated.

The overall ECC prevalence was 24.8 %. ECC was less frequent among children from higher socioeconomic

backgrounds than children from lower ones (prevalence ratios ≤ 0.58).

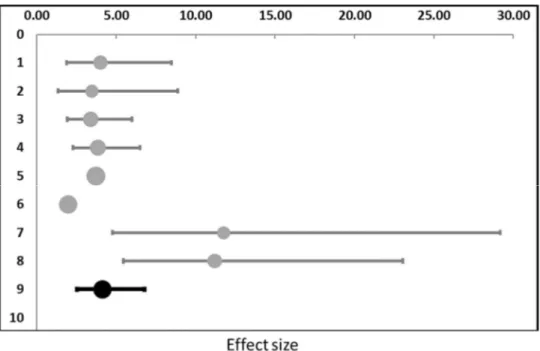

Meta-analysis of studies that reported ORs

All studies that presented odds ratios (Table 3) were included in a meta-analysis except a study by Källestål et al. (Källestål and Wall, 2002). This study indicated significant difference of prevalence of dental caries between immigrants´ and natives´ children. However, the authors did not report the number of native and immigrant participants. Therefore, it could not be included in the meta-analysis. There are six studies with eight separate inputs, because of ORs reported in an age-specific manner in study number 1 and 7 (Table 3).

Table 3. Results presented as adjusted odds ratios (OR) for dental caries in immigrant children compared to native children

*No of native and immigrant participants were not mentioned in the article. Therefore, did not included in the meta analysis

¥ Presence of dentin caries experience’ (decay3-5, missing, filling, and surface > 0) as the dependent variable Study

No. Articles Participants age (years) No of participants Odds Ratio Adjusted (95% CI)

Total Natives Immigrants

1

Jacobsson, B., et al, 2011. Oral health in young individuals with foreign and Swedish

backgrounds--a ten-year perspective. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 12, 151–158.

3 and 5 167 126 41 2.48

(0.95–6.50) 10 and 15 186 151 35 5.80 (2.01-16.7)

2

Almerich-Silla, J.et al., 2007. Influence of immigration and other factors on caries in 12- and 15-yr-old children. European Journal of Oral Sciences 115, 378–383.

12 and 15 879 825 54 2.86

(1.46-5.59)

3

Källestål, C., et al., 2002. Socio-economic effect on caries. Incidence data among Swedish 12-14-year-olds. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 30, 108–114.*

12-14 3,107 – – 1.4

(1.2–1.7)

4

Wigen, T.I.,et al., 2010. Caries and background factors in Norwegian and immigrant 5-year-old children. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 38, 19–28.

5 523 453 70 4.8 (2.5–9.2)

5

Christensen, L.B., et al., 2010. Oral health in children and adolescents with different socio-cultural and socio-economic backgrounds. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica 68, 34–42.

5,7,12, and

15 12,629 9,058 458 (3,113 descendent) 2.0 (1.8–2.1) 6 Hjern, A., et al., 2000. Dental health and access to dental care for ethnic minorities in Sweden.

Ethn Health 5, 23–32. 3-15 4,148 1,920

2,228 1.6

(1.4–1.9)

7¥

Skeie, M.S., et al., 2006. Parental risk attitudes and caries-related behaviours among

immigrant and western native children in Oslo. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 34, 103–113.

3 and 5 353 313 40 4.2 (1.4–12.9)

5 382 341 41 4.3

The main outcome of the meta-analysis involving the studies that reported ORs is the forest plot (Figure 2). The ORs show how many times larger the odds of having dental caries is among the immigrants’ children versus the natives’ children. If the odds ratio is 1 there is no difference in odds between immigrants’ and natives’ children. If the odds ratio is >1, immigrants’ children have a higher odds of dental caries than have natives’ children. The reported odds ratios varied from 1.4 to 5.8. The highest of 5.8 was found in study 1 (Jacobsson et al., 2011), comparing immigrant and native children and adolescents of the age of 10-15 years in Sweden. In that study they found that parents educational background, eating snacks between meals and the amount of plaque were the main causes of the high odds ratio for dental caries (Jacobsson et al., 2011). Wigen et al. also found parents’ education level as risk factor along with parents’ oral health behaviours and attitudes (Wigen and Wang, 2010). The combined OR was 4.12 (95% CI: 2.51-6.78), implying that there is a 4-fold greater odds of having dental caries among the immigrants’ children compared to the natives’ children (Figure 2). The study by Källestål et al.(not included in the meta-analysis) found that immigrants’ boys had higher odds for dental caries, but that girls had lower odds ratio of dental caries. The reason behind the difference was not evaluated

(Källestål and Wall, 2002).

Figure 2. Forest plot showing eight individual effect size measures (row 1 - 8) expressed as odds ratios with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (grey). The combined effect size (9th row) with its 95%

Box 1. Heterogeneity measures related to the meta-analysis of studies that reported ORs.

Box 1 shows the heterogeneity statistics retrieved for the meta-analysis reported ORs. The Q-value of 77.38 with a p-Q-value of <0.0005 indicate true heterogeneity. An I2 value of 90.95% is

also markedly high, indicating a high degree of heterogeneity, and therefore, the combined effect size, although statistically significant, must be interpreted carefully. The funnel plot is indicating a publication bias or that the model needs improvement by including modifiers (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Funnel plot showing the dispersion of the observed effect sizes from the studies reporting ORs.

Q-value 77.38 (p < 0.001) I2 90.95%

τ2 (OR) 0.20

τ (OR) 0.45

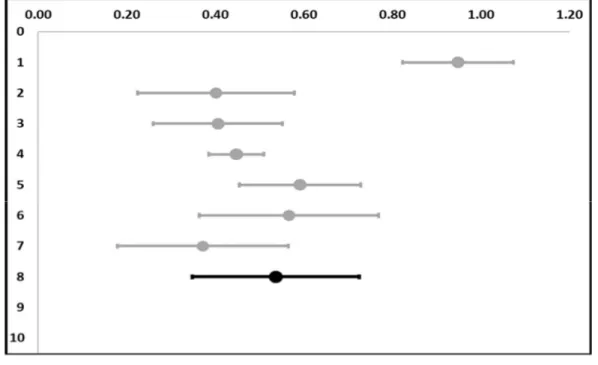

Meta-analysis of studies that reported DMFT index

All studies that presented Decayed Missing Filled teeth (DMFT) index (Table 4) were included in a second meta-analysis. Among the studies included in this meta-analysis, the DMFT index in children 3 to 5 years old living was significantly lower in native European children compared to children with immigrant parents (Ferro et al., 2007).There was also a large degree of variability among studies and between native Europeans and immigrants (Table 4).

Table 4: Studies which reported results as mean DMFT scores among native and immigrant children.

Study

No. Articles

Age of the participants

Number of participants DMFT score Mean ±SD Total Natives Immigrants

8

Enjary, C., et al., 2006. Dental status and measures of deprivation in Clermont-Ferrand, France. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 34, 363–371

5 years 453 246 185 0.58 ± 1.65 native 1.40 ± 2.78 immigrants 10 years 427 200 192 0.44 ± 0.96 native 1.17 ± 1.56 immigrants 9

Ferro, R., et al, 2007. Oral health inequalities in preschool children in North-Eastern Italy as reflected by caries prevalence. Eur J Paediatr Dent 8, 13–18.

3-5 years 3,401 3,124 277 0.8 ± 2.2 native 3.1 ± 4.2 immigrants

10

Baggio, S., et al., 2015. Early childhood caries in Switzerland: a marker of social inequalities. BMC Oral Health 15, 82 11-13 years 502 261 241 0.8 ± 1.51 native 1.49 ± 1.92 immigrants 11

Cvikl, B., et al., 2014. Migration background is associated with caries in Viennese school children, even if parents have received a higher education. BMC Oral Health 14, 51.

12 years 736 373 363

1.50±1.77 native 2.33± 2.28 immigrants

12

Julihn, A., et al., 2010. Migration background: a risk factor for caries development during adolescence. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 118, 618–625. *

13-19 years 11,522 10,404 1,118 1.12 ± 2.47 native 2.27 ± 3.60 immigrants

13

Waltimo, T., et al., 2016. Caries experience in 7-, 12-, and 15-year-old schoolchildren in the canton of Basel-Landschaft, Switzerland, from 1992 to 2011. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 44, 201–208.¥

7-15 years 1,158 912 246 0.8 ± 0.71 native 1.33 ± 1.14 immigrants

* DMFT scores increment from 13 to 19 years of age among adolescents with native Swedish parents and foreign

born parents

¥ Average DMFT scores in the permanent dentition of native and immigrant school children at the age of 7,12, and

The immigrants’ children in Europe presented the worst figures, with DMFT scores ranging from 1.17 to 3.12 and a mean of 1.87. The native European children generally had good outcomes, with a mean DMFT score of 0.75 (Table 4). In the meta-analysis, six studies are managed as seven separate inputs, because of DMFTs reported in an age-specific manner in study number 3 (Table 4, Figure 4). The main outcome of the meta-analysis involving seven separate inputs from six studies that reported mean DMFT scores among native and immigrant’s children is the forest plot shown below (Figure 4). The X-axis represents the effect size measures (plotted on the top of the plot).

Figure 4. Forest plot showing seven individual effect size measures (row 1 - 7) with its confidence interval (grey) of differences in mean DMFT scores among native and immigrant children and adolescents. The combined effect size (8th row) with its 95% confidence interval (black).

Each numbered horizontal gray colored row (except the very bottom one that is numbered 8) illustrates the difference in mean DMFT scores between the children of natives and immigrants reported by the individual studies in the form of a blue circular point along with a 95%

confidence interval (CI); the CI being the estimated interval within which the true population difference in mean DMFT scores lies. The line extending vertically from the effect size of zero marks the “line of no effect”. The horizontal row at the very bottom (the summary row,

numbered 8) reveals the combined effect size (i.e. the combined difference in mean DMFT scores) by displaying a black circular point with a 95% CI marked in black Figure 4

demonstrates a combined effect size of 0.54 (95% CI: 0.35 – 0.73). As the CI does not include 0, the combined effect size is statistically significant, implying that there is a statistically significant difference of about 54% in the mean DMFT scores between natives’ and immigrants’ children, with natives’ children having lower DMFT scores. Further assessment of the heterogeneity requires evaluation of Cochran’s Q (Q-value), τ2 (Tau squared), and I2 values which are

presented below in Box 2.

Box 2. Heterogeneity measures related to the meta-analysis of studies that reported mean DMFT scores.

The Q-value (also referred to as Cochran’s Q) represents the weighted sum of squared

differences between the observed effects and the weighted average effect. It is the output of the statistical test for determining heterogeneity (Huedo-Medina et al., 2006). The Q-value of 56.98 with a p-value of <0.001 suggests presence of true heterogeneity. However, due to the inclusion of only a small number of studies in this review, Q statistic has a poor power to detect

heterogeneity among the studies. Besides, Q-value does not suggest the extent of the

heterogeneity (Huedo-Medina et al., 2006). On the other hand, the τ2 and I2 values reflect the

direct estimate of the between-study variation and the proportion of the observed heterogeneity that is real and not due to random error respectively (Borenstein et al., 2010). Conceptually, I2

value is similar to the intra-class correlation in cluster sampling.

Considering the markedly high I2 value, a subgroup analysis would be a plausible step in the

process of meta-analysis. But, as shown in Figure 4, point estimates of the effect sizes of all the Q-value 56.98 (p < 0.001)

I2 89.47%

τ2 0.04

τ 0.19

would be less informative in this review. Nevertheless, publication bias analysis could provide the opportunity of testing the assumption that the chance that a statistically significant result is published is higher than a statistically non-significant result; leading to computation of combined effect size that might be larger than it actually is in reality. The funnel plot retrieved from Meta-Essentials, show that six out of the seven inputs (6 studies) included (each represented by a small blue circle) are scattered within the red triangle. The X-axis of the funnel plot represents the effect size scale and the Y-axis reflects the precision of the studies in terms of SE (standard error).

Figure 5. Funnel plot showing the dispersion of the observed effect sizes from the studies reporting mean DMFT values.

The red vertical line in the middle of the triangle stands for the combined effect from the meta-analysis. Three blue circles fell to the left side of that line and one fell to the right side; indicating considerable symmetry and lower likelihood of publication bias. Additionally, there are no imputed values in figure 4. Again, the result of this funnel plot cannot be interpreted

meaningfully considering the high degree of heterogeneity among the studies and the small number of included studies.

Studies that reported prevalence

There was one study from Switzerland and one from Spain assessing prevalence of dental caries in children and adolescents. The prevalence of early childhood caries in the Swiss study was doubled among immigrant’s children (42.5%) compared to native children (17.1%). The overall prevalence of caries in children aged 36 to 71 months was 24.8 %. Caries was more frequent among children from low- compared to children from high socioeconomic backgrounds (Baggio et al., 2015). In the Spanish study, prevalence of caries at 6 years of age was 32% (DMFT=1.08) in primary dentition, at 12 years was 42.5% (DMFT=1.07) and at 15-16 years was 55.9%

(DMFT=1.84) in permanent dentition. Dental caries levels at all three age groups in immigrants’ children were significantly higher compared to natives’ children (Almerich Silla, 2006).

However, in the Spanish study only a weak association of dental caries with socioeconomic status was found. In the Spanish study, almost similar differences for prevalence of dental caries were evaluated between immigrants’ and natives’ children at 6 (64.1% and 37%), 12 (45.7% and 89%), and 16 (54.6% and 76.99%) years of age.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this systematic review was to analyse the oral health problems in children and adolescents with immigrant background in comparison to native children in Europe. The review captured significant disparity in oral health status between immigrants’ and natives’ children and

adolescents, as well as higher risk of dental caries, plaque formation and staining on teeth among the former. Regardless of their birthplace, many studies have shown that children of immigrants have poorer oral health condition than native children. A few studies also identify caries on routine examination among immigrant’s children, which indicate poor awareness or less access to use dental services. Most of the studies included in this analysis did not have the scope to investigate the underlying causes of poor oral health status in immigrant’s children, but several factors were suggested: dietary habit, socio-economic condition, educational level, brushing behaviour are most common influential factors.

The dietary practice, appropriate tooth brushing and fluoride dentifrices are beneficial in caries reduction. Studies reported that sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) has strong link with dental caries (Bleich and Vercammen, 2018). The amount of SSB consumption is higher in immigrants’ children in contrast to native children due to cultural difference or ignorance of the parents (de Hoog et al., 2014). This plays a role to increase dental caries incidence in

immigrants’ children. Eating snacks between principal meals is also a risk factor for dental caries among immigrants’ children (Jacobsson et al., 2011). Moreover, Wigen et al. showed that

frequency of tooth-brushing and sugar consumption had a role in dental caries prevalence when controlling other factors (Wigen and Wang, 2010). Fluoride is a mineral that prevents tooth caries. A Cochran review reported that children aged 5 to 16 years who used fluoridated toothpaste two times a day has lower risk of dental caries (Collett et al., 2016). Effective tooth brushing can help in the management of dental caries and ensure oral hygiene in children. Studies suggested that parents must supervise the tooth brushing of school-age children until age 7 to 8 years (Fazele and Saede, 2018). In general, immigrant parents started brushing their child’s teeth later compared to native parents. Furthermore, the immigrants’ children even had less help from adults in daily tooth brushing (Sundby and Petersen, 2003).

Both low and high socioeconomic status (SES) has adverse role in increasing dental caries prevalence among immigrants. Low socio-economic level affects the frequency of visit to dentist. Parents with lower socioeconomic status visit the dentist less frequently, thus increasing the probability of getting dental caries (Christensen, Twetman and Sundby, 2010). Immigrant parents having high socioeconomic status are also responsible for increasing the dental caries rate as the ability of buying SSB and other sugary products increases with increasing income (Wigen and Wang, 2010). Socioeconomic status enhance the risk of new caries in those children already identified and treated (Källestål and Wall, 2002). This is not only due to variation of dental care but also due to inherent features of society. Some European countries such as Sweden, are providing hybrid (publicly funded [free]) oral health care for children and adolescents (Eaton et al., 2019). However, the preventive methods are not proving to be

sufficient to alter the social gradient of caries among the immigrants (Källestål and Wall, 2002) . Communication between parents and oral health care providers plays a key role for ensuring appropriate dental care. Educational level of parents is another plausible factor

to be the main determinant of children’s caries level (Christensen, Twetman and Sundby, 2010). A lower educational level means a lower ability to process and conform to certain information and oral health messages, creating difficulty to engage with healthcare professionals in a fruitful way and to follow care-seeking instructions at facilities. It also affects the ability to adopt to health promoting behaviors. Immigrant parents are often limited by their language barriers and lack of access to healthcare information, resulting in a lower utilization rate of preventive care and services (Chen et al., 2014). In addition to that, insurance policy varies among different locations. As for example, in Spain, children aged 7–15 years are covered by publicly funded oral healthcare. However, it varies according to the types of care required and local health authority (Bravo et al., 2015). On the other hand, all children and adolescents in Sweden have free oral healthcare including all specialist treatments up to 21 ( planned for 24) years of age (Pälvärinne et al., 2018). So, many of the immigrant parents are not even aware that dental care is possibly included as part of their insurance scheme.

Almost all the studies were cross sectional. For better understanding of risk factors

longitudinal studies are recommended. Immigration is a broad term encompassing many factors. The assessment of immigrants and non – immigrants is not easy as the numerous differences make it difficult to account and control for them all. To achieve an unbiased conclusion, all factors (diet, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, population demographics, patient history and time since immigration) should be investigated properly because all the factors have influence on the oral health status of an individual, though they can vary considerably among the many ethnic populations. There were variations in definition of immigrant and non-immigrant children among studies. Some studies defined children as immigrants if mother or father had immigrant

background when other studies has defined them as immigrant only if both parents had

immigrants background. Some studies did not include any clear-cut definition of immigrant. The age range of the children who were included were not similar for all studies. Presentation of data were also not similar. Some studies were presented as odds ratio, some were in DMFT score and others in percentages. This approach was undertaken to answer the research questions focused on the fundamental and simple differences in oral health status of immigrant’s and native children. The age of the children may present another bias, as DMFT scores of mixed dentition across age groups are the result of the dynamics of exfoliating deciduous teeth and their replacement by permanent teeth.

The studies included in this review recommended various strategies for minimizing the disparity in oral health; concerning further evaluation of risk factors by employing different study design, changes in policy and arrangement of specific need-based programmes. Wigen et al. recommended longitudinal study for better evaluation of the factors related to high prevalence of dental caries among immigrant children (Wigen and Wang, 2010). Most of the studies

prescribe specific programmes concentrating efforts on improving accessibility for children and adolescents with specific attributes like immigrant background in combination with measures to change behaviours. One such measure could be arrangement of periodic oral health risk

assessment free of cost followed by a contingent referral and treatment plan for those deemed to be requiring treatment. Although the issue of accessibility to this type of assessment is a complex one, it could be increased through concerted efforts from day-care centres and schools which could serve as channels for reaching those children and adolescents, sensitizing and motivating them to avail the opportunity of periodic risk assessment and also, for conveying to them the knowledge and messages pivotal to a sound oral health. In order to engage these institutions effectively, specific policy initiatives need to be in place.

With the turn of the first decade of twenty first century, countries across the world have decided to commit to concrete actions to fulfil the long-cherished dream of ensuring essential quality health services for everyone on this planet without financial hardship (WHO, 2015). At the heart of this vision lies an ambition to eliminate inequities in health. The social gradient in oral health has established an unfavourable scenario for children and adolescents with immigrant background living in European countries. Studies capturing this were included in this systematic review to summarize the findings, to elicit potential underlying factors and to solicit a way forward. Considering the multidimensional link between oral health and overall wellbeing, an evidence-based co-ordinated action plan is necessary to tackle the inequality in oral health status among immigrants’ children and adolescents.

CONCLUSION

Immigrant children and adolescents have higher risk of dental caries and poorer health status

than their native counterparts in Europe. Non-biological factors such as dietary practices, socioeconomic status, parental educational level, tooth-brushing habit, and so forth are likely to be catalysing this disparity. However, how these influences lead to this well-documented

gradient of inequality remains to be investigated with appropriately designed studies. Further research should be undertaken to critically examine how, despite having free dental care in many settings, the oral health status of immigrants’ children and adolescents is not improving. It is also important to adopt mixed methods aiming not only to quantify the problem but also to be able to shed light on sociocultural and behavioural dimensions that render these children and adolescents more susceptible to poor oral health. Furthermore, specific programmes based on inputs from these studies could be planned and implemented focusing specific groups to minimize the disparity.

REFERENCES

Almerich Silla, J. M. (2006) ‘Oral health survey of the child population in the Valencia Region of Spain (2004)’, Medicina Oral, Patologia Oral Y Cirugia Bucal, 11(4), pp. E369-381. Almerich‐Silla, J. M. and Montiel‐Company, J. M. (2007) ‘Influence of immigration and other factors on caries in 12- and 15-yr-old children’, European Journal of Oral Sciences, 115(5), pp. 378–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2007.00471.x.

Baggio, S. et al. (2015) ‘Early childhood caries in Switzerland: a marker of social inequalities’, BMC oral health, 15, p. 82. doi: 10.1186/s12903-015-0066-y.

Bissar, A.-R. et al. (2007) ‘Dental health, received care, and treatment needs in 11- to 13-year-old children with immigrant background in Heidelberg, Germany’, International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry, 17(5), pp. 364–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2007.00846.x.

Bleich, S. N. and Vercammen, K. A. (2018) ‘The negative impact of sugar-sweetened beverages on children’s health: an update of the literature’, BMC Obesity, 5(1), p. 6. doi: 10.1186/s40608-017-0178-9.

Borenstein, M. et al. (2010) ‘A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis’, Research Synthesis Methods, 1(2), pp. 97–111. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.12.

Bravo, M. et al. (2015) ‘The healthcare system and the provision of oral healthcare in European Union member states. Part 2: Spain’, British Dental Journal, 219(11), pp. 547–551. doi:

10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.922.

Chen, C.-C. et al. (2014) ‘Immigrant-native differences in caries-related knowledge, attitude, and oral health behaviors: a cross-sectional study in Taiwan’, BMC oral health, 14, p. 3. doi:

10.1186/1472-6831-14-3.

Christensen, L. B., Twetman, S. and Sundby, A. (2010) ‘Oral health in children and adolescents with different socio-cultural and socio-economic backgrounds’, Acta Odontologica

Scandinavica, 68(1), pp. 34–42. doi: 10.3109/00016350903301712.

Çolak, H. et al. (2013) ‘Early childhood caries update: A review of causes, diagnoses, and treatments’, Journal of Natural Science, Biology, and Medicine, 4(1), pp. 29–38. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.107257.

Collett, B. R. et al. (2016) ‘Observed child and parent toothbrushing behaviors and child oral health’, International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry, 26(3), pp. 184–192. doi:

10.1111/ipd.12175.

Cvikl, B. et al. (2014) ‘Migration background is associated with caries in Viennese school children, even if parents have received a higher education’, BMC oral health, 14, p. 51. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-14-51.

Dahlan, R. et al. (2019) ‘Impact of social support on oral health among immigrants and ethnic minorities: A systematic review’, PLoS ONE, 14(6). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218678. Duijster, D. et al. (2015) ‘Establishing oral health promoting behaviours in children – parents’ views on barriers, facilitators and professional support: a qualitative study’, BMC Oral Health, 15. doi: 10.1186/s12903-015-0145-0.

Dye, B. A., Li, X. and Beltran-Aguilar, E. D. (2012) ‘Selected oral health indicators in the United States, 2005-2008’, NCHS data brief, (96), pp. 1–8.

Eaton, K. A. et al. (2019) ‘Variations in the provision and cost of oral healthcare in 11 European countries: a case study’, International Dental Journal, 69(2), pp. 130–140. doi:

https://doi.org/10.1111/idj.12437.

Egger, M. et al. (1997) ‘Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test.’, BMJ : British Medical Journal, 315(7109), pp. 629–634.

Enjary, C. et al. (2006) ‘Dental status and measures of deprivation in Clermont-Ferrand, France’, Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 34(5), pp. 363–371. doi:

10.1111/j.1600-0528.2006.00284.x.

Fazele, A.-M. and Saede, A.-M. (2018) ‘Tooth Brushing in Children’, Journal of Dental Materials and Techniques, 7(4), pp. 181–184.

Ferro, R. et al. (2007) ‘Oral health inequalities in preschool children in North-Eastern Italy as reflected by caries prevalence’, European Journal of Paediatric Dentistry: Official Journal of European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry, 8(1), pp. 13–18.

Gupta, E. et al. (2015) ‘Oral Health Inequalities: Relationships between Environmental and Individual Factors’, Journal of Dental Research, 94(10), pp. 1362–1368. doi:

10.1177/0022034515592880.

Hall-Scullin, E. et al. (2015) ‘A qualitative study of the views of adolescents on their caries risk and prevention behaviours’, BMC Oral Health, 15. doi: 10.1186/s12903-015-0128-1.

Hjern, A. and Grindefjord, M. (2000) ‘Dental health and access to dental care for ethnic

minorities in Sweden’, Ethnicity & Health, 5(1), pp. 23–32. doi: 10.1080/13557850050007310. de Hoog, M. L. A. et al. (2014) ‘Racial/ethnic and immigrant differences in early childhood diet quality’, Public health nutrition, 17(6), pp. 1308–1317. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013001183. Huedo-Medina, T. B. et al. (2006) ‘Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2

index?’, Psychological Methods, 11(2), pp. 193–206. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.193.

IntHout, J., Ioannidis, J. P. and Borm, G. F. (2014) ‘The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method’, BMC Medical Research Methodology, 14(1), p. 25. doi:

Jacobsson, B. et al. (2011) ‘Oral health in young individuals with foreign and Swedish backgrounds--a ten-year perspective’, European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry: Official Journal of the European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry, 12(3), pp. 151–158.

Jin, L. J. et al. (2016) ‘Global burden of oral diseases: emerging concepts, management and interplay with systemic health’, Oral Diseases, 22(7), pp. 609–619. doi: 10.1111/odi.12428. Johnson, N. W. et al. (2011) ‘Global oral health inequalities in incidence and outcomes for oral cancer: causes and solutions’, Advances in Dental Research, 23(2), pp. 237–246. doi:

10.1177/0022034511402082.

Julihn, A., Ekbom, A. and Modéer, T. (2010) ‘Migration background: a risk factor for caries development during adolescence’, European Journal of Oral Sciences, 118(6), pp. 618–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2010.00774.x.

Källestål, C. and Wall, S. (2002) ‘Socio-economic effect on caries. Incidence data among Swedish 12-14-year-olds’, Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 30(2), pp. 108–114. Karlberg, G. and Ringsberg, K. (2006) Experiences of oral health care among immigrants from Iran and Iraq living in Sweden. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v1i2.4924.

Kassebaum, N. J. et al. (2015) ‘Global burden of untreated caries: a systematic review and metaregression’, Journal of Dental Research, 94(5), pp. 650–658. doi:

10.1177/0022034515573272.

Khamis, A. H. (2016) ‘Re-Visiting the Decay, Missing, Filled Teeth (DMFT) Index with a Mathematical Modeling Concept’, Open Journal of Epidemiology, 06(01), pp. 16–22. doi: 10.4236/ojepi.2016.61003.

Marmot, M. and Bell, R. (2011) ‘Social Determinants and Dental Health’, Advances in Dental Research, 23(2), pp. 201–206. doi: 10.1177/0022034511402079.

Pälvärinne, R. et al. (2018) ‘The healthcare system and the provision of oral healthcare in European Union member states. Part 9: Sweden’, British Dental Journal, 224(8), pp. 647–651. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2018.269.

Patel, R. (2012) The State of Oral Health in Europe - Report Commissioned by the Platform for Better Oral Health in Europe. Available at: http://www.oralhealthplatform.eu/our-work/the-state-of-oral-health-in-europe/ (Accessed: 8 March 2020).

Petersen, P. E. (2003) ‘The World Oral Health Report 2003: continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century--the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme’, Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 31 Suppl 1, pp. 3–23.

Petersen, P. E. et al. (2005) ‘The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health.’, Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 83(9), pp. 661–669.

Petersen, P. E. (2009) ‘Global policy for improvement of oral health in the 21st century – implications to oral health research of World Health Assembly 2007, World Health Organization’, Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 37(1), pp. 1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2008.00448.x.

Petersen, P. E. and Kwan, S. (2011) ‘Equity, social determinants and public health programmes - the case of oral health: Equity, social determinants and public health programmes’, Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 39(6), pp. 481–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2011.00623.x. Portero, S. and Cebrino, J. (2020) ‘Oral Health Problems and Utilization of Dental Services among Spanish and Immigrant Children and Adolescents’, International Journal of

Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), p. 738. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17030738. Seirawan, H., Faust, S. and Mulligan, R. (2012) ‘The Impact of Oral Health on the Academic Performance of Disadvantaged Children’, American Journal of Public Health, 102(9), pp. 1729– 1734. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300478.

Sgan-Cohen, Harold, D. and Mann, J. (2007) ‘Health, oral health and poverty’, Journal of the American Dental Association (1939), 138(11), pp. 1437–1442.

Silva, A. N. da, Mendonça, M. H. M. de and Vettore, M. V. (2008) ‘A salutogenic approach to oral health promotion’, Cadernos De Saude Publica, 24 Suppl 4, pp. s521-530.

Skeie, M. S. et al. (2006) ‘Parental risk attitudes and caries-related behaviours among immigrant and western native children in Oslo’, Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 34(2), pp. 103–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2006.00256.x.

Skeie, M. S. and Klock, K. S. (2018) ‘Dental caries prevention strategies among children and adolescents with immigrant - or low socioeconomic backgrounds- do they work? A systematic review’, BMC oral health, 18(1), p. 20. doi: 10.1186/s12903-018-0478-6.

Steven J, V. and Jerry A, C. (2009) ‘Basic Meta-Analysis: Conceptualization and Computation’, Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 30(1), pp. 75–80. doi:

10.1097/DBP.0b013e318196b0ba.

Sundby, A. and Petersen, P. E. (2003) ‘Oral health status in relation to ethnicity of children in the Municipality of Copenhagen, Denmark’, International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry, 13(3), pp. 150–157. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263X.2003.00449.x.

Suurmond, R., van Rhee, H. and Hak, T. (2017) ‘Introduction, comparison, and validation of Meta‐Essentials: A free and simple tool for meta‐analysis’, Research Synthesis Methods, 8(4), pp. 537–553. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1260.

Waltimo, T. et al. (2016) ‘Caries experience in 7-, 12-, and 15-year-old schoolchildren in the canton of Basel-Landschaft, Switzerland, from 1992 to 2011’, Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 44(3), pp. 201–208. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12206.

Watt, R. G. (2005) ‘Strategies and approaches in oral disease prevention and health promotion.’, Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 83(9), pp. 711–718.

WHO (2003) World Oral Health Report 2003. Available at:

https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/68506/WHO_NMH_NPH_ORH_03.2.pdf?sequ ence=1&isAllowed=y (Accessed: 11 June 2020).

WHO (2015) Universal Health Coverage: Supporting Country Needs. World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/contracting/UHC_Country_Support.pdf. Wigen, T. I. and Wang, N. J. (2010) ‘Caries and background factors in Norwegian and

immigrant 5-year-old children’, Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 38(1), pp. 19–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2009.00502.x.

Zimmerman, M., Bornstein, R. and Martinsson, T. (1995) ‘Utilization of dental services in refugees in Sweden 1975-1985’, Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 23(2), pp. 95–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1995.tb00208.x.

APPENDIX

Table 1A: Articles that were excluded in the systematic review after reviewing full text

Author Title of the paper Reason for exclusion

Nørrisgaard PEet al Prevalence, risk surfaces and inter-municipality variations

in caries experience in Danish children and adolescents in 2012 Not evaluated the migration status Dahlander et al The influence of immigrant background on the choice of

sedation method in paediatric dentistry Not evaluated the dental caries Aljafri AK et al Failure on all fronts: general dental practitioners' views on

promoting oral health in high caries risk children--a qualitative study

Qualitative Gläser-Ammann P Dental knowledge and attitude toward school dental-health

programs among parents of kindergarten children in Winterthur Qualitative Meurman P Mutans streptococci colonization associates with the

occupation of caretaker, a practise-based study

Out of context Ekstrand KR Factors associated with inter-municipality differences in dental

caries experience among Danish adolescents. An ecological study

Ecological Study Benger S Are pit and fissure sealants needed in children with a

higher caries risk? Migration status was not evaluated

Cortés Martinicorena FJ Dental health of children and adolescents of Navarra, 2007 (4th

edition) Not in English

Haugejorden O Analysis of the ups and downs of caries experience among Norwegian children aged five years between 1997 and 2003

Not compare immigrants and non immigrants

Ferro R Comparison of data on Early Childhood Caries (ECC) with previous data for Baby Bottle Tooth Decay (BBTD) in an Italian kindergarten population.

Migration status was not evaluated

Marthaler Changes in dental caries 1953-2003 Not specific in Europe

Paredes Gallardo Prevalence of dental caries: comparison between immigrant and autochthonous children

In Spanish language Heinrich-Weltzien R Dental health of first molars among Westphalian immigrants

and German students In German language

Azogui levy S Evaluation of a dental care program for school beginners in a Paris suburb

Out of context Kalyvas Dental health of 5-year-old children and parents' perceptions

for oral health in the prefectures of Athens and Piraeus in the Attica County of Greece.

Immigrant status discussed in abstract and discussion but the data were not