One-year Political Science MA programme in Global Politics and Societal Change Dept. of Global Political Studies

Course: Political Science Thesis ST632L (15 credits) Spring 2020

Supervisor: Kristian Steiner

Food insecurity in Nigeria

An analysis of the impact of climate change, economic

development, and conflict on food security

Abstract

Food insecurity is a major problem in Nigeria. The Food and Agriculture Organization esti-mates that Nigeria’s food security situation has worsened in the past 15 years. This thesis ex-amines the impacts of different factors that jeopardize the Nigerian food security situation. Ac-cording to previous literature, there are mostly three factors that affect food security; climate change, economic development, and violent conflict. Nigeria is the chosen case study because all the above mentioned factors play a key role in the country; it is affected by climate change, the economy is fluctuating and there has been the Boko Haram insurgency going on since 2009. This thesis aims, with the help of the concept of food security, to analyze these factors to see whether and to what extent they influence food insecurity in Nigeria.

The thesis uses a mixed-methods approach. Quantitative data are retrieved from several data-bases that give measurements on food security, climate change, economy, and conflict. Quali-tative data are reports and interviews that were conducted with Nigerian NGO’s.

Cautious findings show that all three factors can lead to food insecurity and, therefore, can explain why there is food insecurity in Nigeria. Finally, this paper concludes and confirms the results of existing research in the case of Nigeria.

Keywords: food insecurity, Nigeria, climate change, economic development, violent conflict Word Count: 16425 excluding Annex

Table of Content

List of Abbreviations ... 1

List of Figures ... 2

1. Introduction ... 3

1.1 Introduction to the topic... 3

1.2 Research problem ... 3

1.3 Aim and research question... 4

1.4 Organization of the thesis ... 4

2. Background ... 5

2.1 Nigeria and its economy ... 5

2.2 Climate change in Nigeria ... 6

2.3 Development of the Boko Haram terrorist organization ... 6

3. Literature review ... 9

3.1 Climate change as a driver of food insecurity ... 9

3.2 Economic development as a driver of food insecurity ... 11

3.3 Violent conflict as a driver of food insecurity ... 12

4. Conceptual framework ... 15

5. Methodology... 18

5.1 Research design and data ... 18

5.2 Food (in)security data ... 19

5.3 Climate change data... 21

5.4 Economic development data ... 22

5.5 Violent conflict data ... 24

6. Analysis... 26

6.1 Food security situation in Nigeria... 26

6.2 The importance of climate change... 28

6.3 The importance of economic development... 32

6.4 The importance of violent conflict ... 39

7. Conclusion ... 43

8. Bibliography... 45

1

List of Abbreviations

ACLED Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project AFAN All Farmers Association Nigeria

AQUIM Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb FAO Food and Agriculture Organization GDP Gross Domestic Product

GHS General Household Survey HAZ Height-for-age z-score

IAFD International Fund for Agricultural Development IDP Internally Displaced Person

IDMC Internal Displacement Monitoring Center NBS Nigerian National Bureau of Statistics NiMet Nigerian Meteorological Agency

OCHA United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs UCDP Uppsala Conflict Data Program

2

List of Figures

Figure 1: Food security concept ... 15

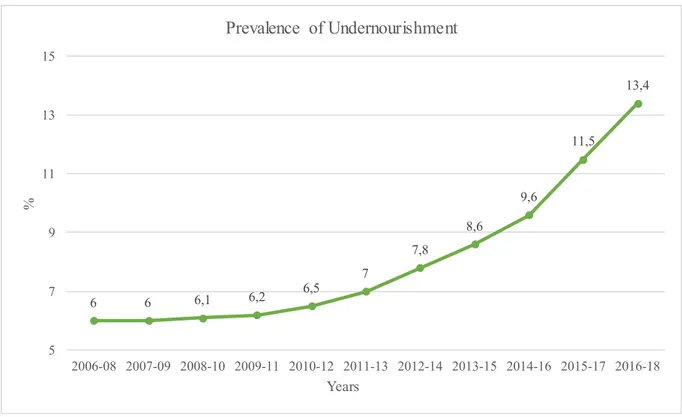

Figure 1.1: Prevalence of Undernourishment (3-year average), 2000-2018 ... 27

Figure 1.2: Households facing food shortage ... 27

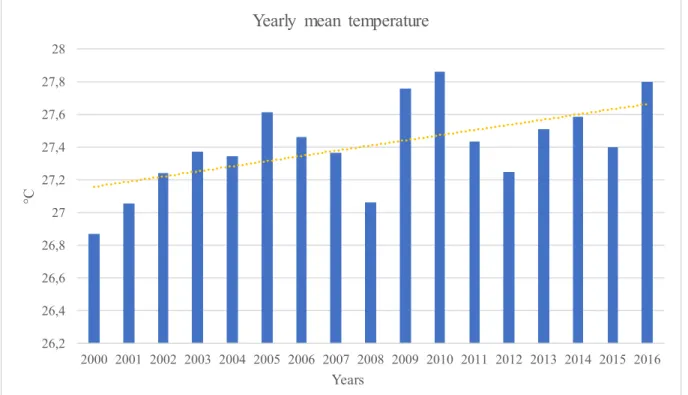

Figure 2.1: Yearly mean temperature in Nigeria, 2000-2016 ... 29

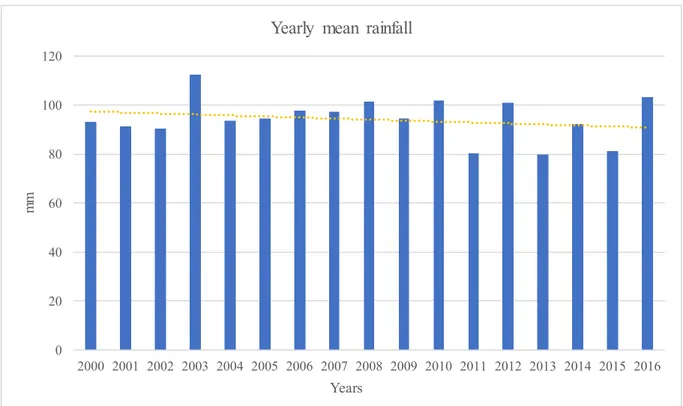

Figure 2.2: Yearly mean rainfall in Nigeria, 2000-2016 ... 30

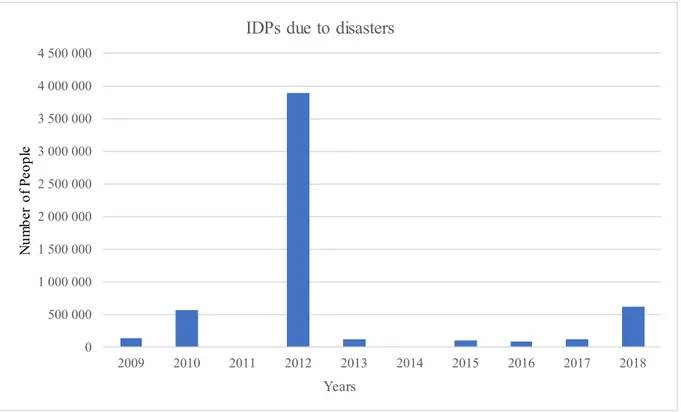

Figure 2.3: IDPs due to disasters, 2009-2018... 31

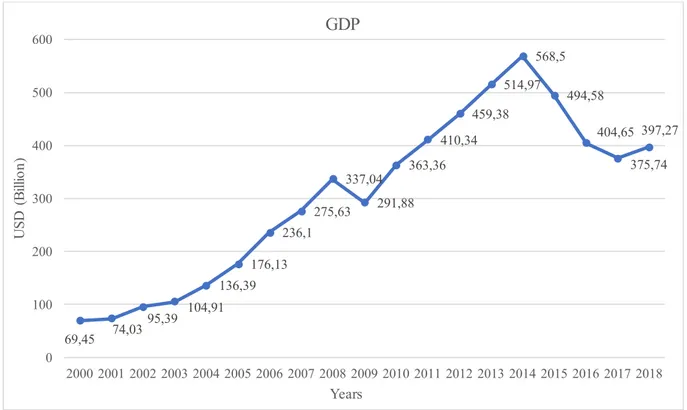

Figure 3.1: Nigeria’s GDP, 2000-2018 ... 33

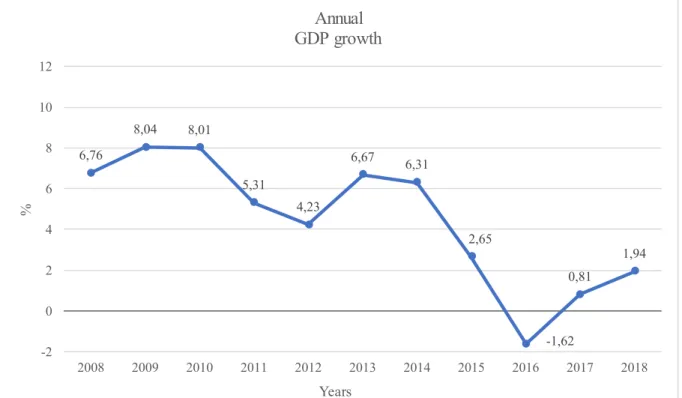

Figure 3.2: Annual GDP growth, 2008-2018 ... 34

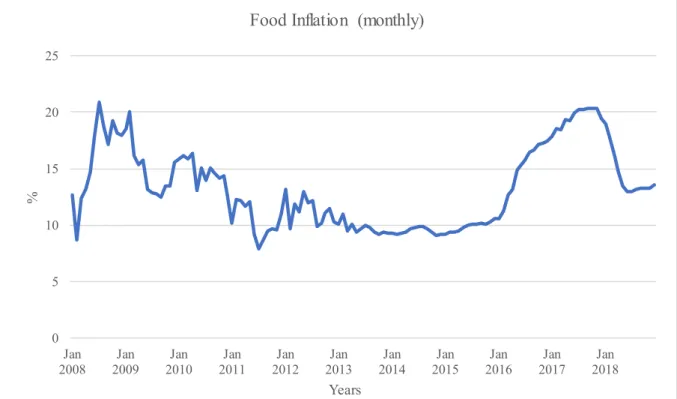

Figure 3.3: Food inflation (monthly), 2008-2018 ... 35

Figure 3.4: Trade Balance in Nigeria, 2008-2017 ... 35

Figure 3.5: Export total and Export of Mineral Products from Nigeria, 2008-2017 ... 36

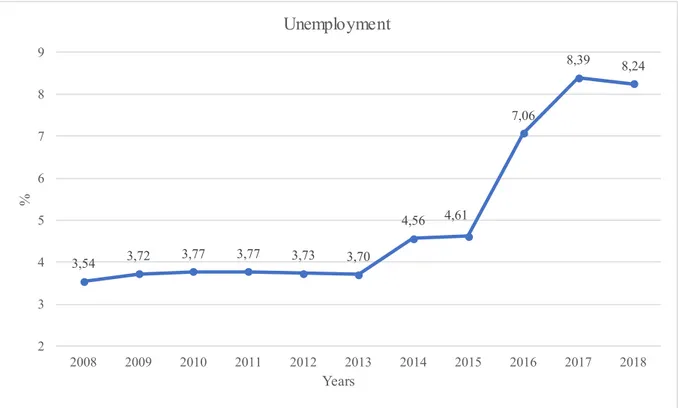

Figure 3.6: Unemployment, 2008-2018. ... 37

Figure 4.1: Conflicts with Boko Haram involved, 2009-2019 ... 39

Figure 4.2: Fatalities in conflicts, 2009-2019... 40

Figure 4.3: IDPs due to conflict, 2009-2019 ... 41 All figures are illustrated by the author.

3

1. Introduction

1.1 Introduction to the topic

Food security is a basic human need and fighting hunger is one of the greatest challenges of this century. (Ojo and Adebayo, 2012: 204). Although the number of people living in hunger has declined for many years, in 2015 it has started to increase again (FAO et al. 2019). Today, two billion people are still living in moderate or severe food insecurity, because they do not have regular access to food, not a necessary variety of nutritional value, or there is not enough food for the whole population available. 820 Million of these two billion facing food insecurity are living in hunger (FAO et al., 2019: 22). Particularly in developing countries, people cannot meet their nutritional needs (Oyinloye et al., 2018: 69).

It is an immensely discussed issue in our society and many scholars have studied the factors leading to food security with their direct and indirect impacts on food security (e.g. Berhanu and Wolde, 2019; Martin-Shields and Stojetz, 2019; Musemwa et al., 2015). Amongst others, Misselhorn (2005) has compared different drivers and three key factors causing food insecurity: conflict, climate change, and economic development. As many scholars analyzed, these drivers often co-exist and influence each other. Only assessing a single factor influencing food insecu-rity is almost impossible and it is important to take confounding drivers into account.

1.2 Research problem

A strong argument that encourages analyzing food security issues is the importance of food in our lives. There is evidence that climate change, economic development, and conflict affect food security negatively. For example, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Interna-tional Fund for Agricultural Development, United Nations Children’s Fund, World Food Pro-gramme, and the World Health Organization have for the last three years published the report ‘The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World’ that focused on conflict (FAO et al., 2017), climate change (FAO et al., 2018), and the economy as a driver of food insecurity (FAO et al., 2019). This shows that these factors are a global concern in today’s world.

Nigeria is one of the most food insecure countries and highly affected by all three drivers. For one, the country is vulnerable to climate change and successively hit by environmental disasters, that impact people’s livelihoods (Nkechi et al., 2017: 301). Furthermore, its economy is thriving, but around 48% of its population lives below the poverty line. (World Bank, 2020; World Poverty Clock, 2020). In addition to that, since 2009 northeastern Nigeria is struck by

4

conflict, with the terrorist group Boko Haram involved. Due to that, Nigeria is suitable to use as a case study.

1.3 Aim and research question

Research that has been done on food insecurity has mostly focused on one driver, acknowledg-ing others as compoundacknowledg-ing variables. Furthermore, many scholars have done a quantitative analysis. This thesis analyzes different drivers for food insecurity in a single country analysis. It focuses on Nigeria, because, as mentioned above, it is a food-deficit country and all three key drivers are existing in said country and can be analyzed. This leads to the following research question:

• What factors impact food insecurity and jeopardize the food security situation in Nige-ria?

The impact these drivers have on the food security situation in Nigeria is assessed in the thesis. The analysis can be examined with the help of deductive research and a case study re-search design. To answer the rere-search question there are three sub-questions to be answered:

• What impact does climate change have on food security in Nigeria? • What impact does Nigeria’s economy have on its food security situation? • What impact does the Boko Haram Insurgency have on food security in Nigeria? 1.4 Organization of the thesis

After this introductory chapter, the next chapter elaborates on background information on cli-mate change in Nigeria, Nigeria’s economy, and the Boko Haram terrorist group. The third chapter provides a review of previous literature. It shows what scholars found on the different drivers impacting food security. After this, the concept of food security that is used in this thesis is illustrated. Chapter five describes the research design, how the data for the analysis was col-lected, and its operationalization. Chapter six compounds the analysis. It is split into three sec-tions, analyzing each driver and its impact on food insecurity individually. The last chapter concludes the thesis and shows ideas for further research.

5

2. Background

The Federal Republic of Nigeria is a culturally and religiously multifaceted country located in West Africa. It consists of 36 states and a capital territory. With approximately 201 Million, it is the most populated country in Africa and its population is growing rapidly (World Poverty Clock, 2019). Nigeria declared its independence from Great Britain in 1960. After going through years of military junta, the country held its first democratic elections in 1999. Since then it has been an unstable democracy with a lot of corruption and struggles to fight terrorism (Kah, 2017; World Bank, 2016). This chapter gives a background on Nigeria’s economic sector, climate change in Nigeria, and the Boko Haram insurgency.

2.1 Nigeria and its economy

Today Nigeria has a key role in Africa’s economy with a large natural resource reservoir. It is a founding member of the African Union and an important, influential member of the Eco-nomic Community of West African States.

Nigeria’s biggest economic sector is the oil industry. With exporting these natural re-sources, its economic growth depends highly on the world market and world oil prices. (World Bank, 2020). Another important, but smaller sector, that has been contributing to Nigeria’s economic growth, is agriculture. Agriculture is the income for many Nigerians. The Nigerian Government operates on an agriculture strategy to achieve the first two goals of the sustainable development goals, reducing hunger and poverty, by for example bringing private sectors to invest in agriculture, building institutions in rural areas and developing the infrastructure over the country (Obi et al., 2020: 208; World Bank, 2020). The Nigerian government has started with its intense oil trade under British rule and as a result, neglected agriculture as an important economic sector when the oil industry got bigger and then invested more in oil exploration, however at the moment they are working on reinvesting in this sector (Ojo and Adebayo, 2012: 205; Babu, 2018: 113-114).

Despite being an overall rich country with oil assets, Nigeria’s economy has not created many more job opportunities and only a few people benefit from the GDP growth. (World Bank, 2019: 20). About 96 million people, 48%, of the population suffer from extreme poverty (Otekunrin et al., 2019: 4-5, World Poverty Clock, 2020). Since the population is growing rap-idly and the percentage of people living in poverty is only slightly changing, the absolute num-ber of people in poverty is increasing as well, which causes even more people to suffer from food insecurity (Ugwoke et al, 2020: 1).

6

While poverty in the South has been decreasing over the years, it has been increasing in the North, especially the North East, because the region is developing less than the South (Ug-woke et al, 2020: 1). The poverty level is more than 50% higher in the North than in the South. Oil reserves are in the South and the economy in the Northeast and the cultivation of land is mostly done in rural areas in the North (Otekunrin et al., 2019: 6).

2.2 Climate change in Nigeria

Climate change is a global issue that affects every country. Nigeria is, amongst most Sub-Sa-haran states vulnerable to the impacts of environmental problems. Throughout the years, envi-ronmental disasters have become more frequent. In 2012, for example, there was one of the worst floods in Nigeria in 40 years. This led to the loss of many lives, displacement of people, and farmland being washed away (Nkechi et al., 2017: 301). Nevertheless, climate change does not affect all states the same. Nigeria has four different geographical climate zones: ‘the warm desert climate in the Northeast, the warm semiarid climate in the other parts of the North, the monsoon climate in the Niger-Delta, and the tropical savannah climate in the middle belt and parts of the southwest’ (Akande et al., 2017: 2-3). Rainfall is low in the North and high in the South, which leads to shorter rain seasons and desertification in the North and floods in the South. The coastal area in the South has furthermore to deal with the sea level rise. However, all in all, the North is more vulnerable to climate change (Obioha, 2009: 107-108; Akande et al., 2017).

Desertification as well as too much rainfall can lead to damages in cultivation and displace-ment of people. Therefore, the whole country is hit by climate change. All in all, there is evi-dence that climate change will worsen Nigeria’s environment in the future (World Bank, 2016: 49; Abdulkadir, 2017; FAO, 2017).

2.3 Development of the Boko Haram terrorist organization

Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati WalJihad, commonly known as Boko Haram and in this

thesis referred to as Boko Haram, is an Islamic territorial terrorist organization in Nigeria. They do not only aim for territories but also want to destroy the current Nigerian political system in said area to establish their political and religious ideology. They do this through attacks on humans and public facilities as well as the destruction of infrastructure and economic develop-ment (ICC, 2014: 9; Adelaja and George, 2019: 185-186).

7

The group was established between 2002 and 2003 in northeastern Nigeria, where, contrary to the south, most of the population is Muslim. Boko Haram has surfaced in 2003 when they attacked police stations and public buildings in the northeastern Yobe State. The buildings were occupied for some days and the group demonstrated its sympathy with Afghanistan’s Taliban (Pham, 2016: 3).

Until Nigerian authorities captured and killed their leader Mohammed Yusuf in 2009, they were quite unknown, their attacks were small and simple. Yusuf wanted an Islamic government but achieving that politically in a nonviolent way (ICC, 2014: 9). With their new leader, Boko Haram launched an insurgency and got well-known. They turned to the Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQUIM) terrorist group, got supported, mainly with financial aid, by AQUIM’s leader and became a jihadist terrorist group. One attack, that gave Boko Haram international attention, was a suicide attack on a United Nations (UN) compound in Abuja in 2011. (Pham, 2016: 6).

Since the summer of 2009, northeastern Nigeria has struggled with numerous terrorist at-tacks, many of them suicide atat-tacks, regularly, aiming against the Nigerian government and its democracy. The three northeastern states, Adamawa, Borno, and Yobe, have a majority of Mus-lims and were targeted most. Other states were also hit, but they also dealt with people fleeing from the conflict, that took local government's resources and budgets away (Adelaja and George, 2019: 3).

Boko Haram aims to destruct selectively. They destroy assets, infrastructure, and ture. At the same time, they attack ‘government storage facilities, fertilizer factories, agricul-tural input transport systems and farms’ (Adelaja and George, 2019: 185), which they attack for their use and survival.

In 2012 the group got more power and became internationally recognized as a militant group that can build and use bombs. Boko Haram built an international network with other African Islamic groups and was able to expand to the neighboring countries, Niger and Came-roon. The militants attacked prisons to release the prisoners, destroyed government buildings, hospitals, and burned down schools, forcing students out of education. By mid-2013 Boko Ha-ram has controlled several local governments, having de facto authorities in these regions. In 2014 the Boko Haram insurgency hit its height. In the first half of the year, they killed at least 2053 civilians in numerous, almost daily attacks on marketplaces, churches, and residential areas. One of the most infamous attack was the kidnapping of 2776 girls in a school in Borno state (Human Rights Watch, 2014). In mid-2014, the fighters had enough money and resources to go into offense, executing people in public and expand successively. By then they were able

8

to occupy approximately 27-26 local governments. Most of the occupied regions were in a rural area, where agriculture is the livelihood of the population, hereby agricultural land was de-stroyed (Pham, 2016: 9-10; Adelaja and George, 2019: 186).

In 2015 Boko Haram showed weakness and the Nigerian army and government reclaimed the zones that were taken over. Nigeria declared victory over Boko Haram quickly. The group has had internal struggles and split into two factions. One faction pledged allegiance to the Islamic State (IS), turning into the Islamic West Africa Province (BBC, 2015; Amao, 2020). The number of attacks and fatalities has dropped, but in 2017, now being two groups, attacks have gone up again and the Nigerian government is continuously challenged (ACLED, 2019a; Amao, 2020: 7).

9

3. Literature review

This literature review discusses previous research on the causes of food insecurity. Most of the research on the effects on food security has been done quantitatively and previous studies usu-ally used either a statistical approach or simulation models, whereas the statistical approach is mainly used (Hertel and Rosch, 2010: 361). Scholars have studied different drivers that influ-ence food security. Amongst them, three drivers stand out: environmental and climate change, the economic situation of the population, and political and social unrest or war (Misselhorn, 2005: 37-38; Oyinloye et al., 2018:). To answer the research question, analyzing these three most examined factors impacting food security are important and are reviewed in this chapter. 3.1 Climate change as a driver of food insecurity

Climate change is defined as ‘any change in climate over time, whether due to natural variability or as a result of human activity’ (IPCC 2001: 2). Climate change has turned into a global issue and has worsened in recent times. It is now considered a climate crisis and threatens the agri-cultural production due to higher and more inconsistent temperatures as well as the variation in rainfall patterns and extreme events, such as droughts and floods, occurring more often (Ojo and Adebayo, 2012: 211; Ogbo et al., 2013: 221). With this change, researchers decided to study the relationship between climate change and food security. Studies were done concerning one single country, several countries, or simply regions. Most of the research has been con-ducted through surveys, direct observation, and weather data. They often used a modeling ap-proach, because they often predicted future scenarios (Zewdie, 2014; Berhanu and Wolde, 2019; Wossen et al., 2018; Fudjumdjum et al. 2019). Researchers agree upon several impacts that climate change already has or will have on food security: on the cultivation and crop yields, as well as on biodiversity.

Climate change affects the first aspect of the food supply chain most. Food production starts with crop growth and cultivation. These are strongly affected by climate variability and therefore especially the agricultural sector is hit by climate change. (Jung and Kunstmann, 2007; Wossen and Berger, 2015). In Iran for example Karimi et al. (2018) have with the help of crop modeling looked towards the possible impacts, the decline of water resources and pre-cipitation, warmer temperature, and higher CO2 emissions will have on crop growth and food

production. Their findings were similar to the majority of research: food production depends on a steady climate and enough clean water resources.

10

Another effect climate change has on the beginning of the food supply chain is in the fish-ery sector. According to Ficke (2007) and Muringai et al. (2020) droughts, that are happening due to climate variability are the biggest problem in that sector. Water temperature is increasing, and the level of oxygen is decreasing which leads to a change of fish habitats. The fish might then be contaminated with bacteria, might reproduce less, or get wiped out completely. Droughts can also lead to desertification and lakes disappear, on which small-scale fishers de-pend (Tirado et al, 2010: 1755)

Food quality can also be affected by climate change. People might consume toxic food or might not be able to eat the recommended amount of daily calorie intake. A meta-analysis of several different experiments by Taub et al. (2008) has found that the concentration of protein in crops has reduced when these crops were exposed to high CO2, and because CO2 is increasing

due to climate change, the food quality overall can decrease. Furthermore, Tirado et al. (2010) analyzed the contamination of local foods as a factor jeopardizing food quality that can severely affect food security and livelihoods. They found out that a higher risk of extreme weather events, such as droughts and floods can contaminate water, soil, and agricultural land with haz-ardous substances during crop production. Several climate-related events were analyzed and a correlation between these and the contamination of food has been found. For example, the 2002 flooding in Central Europe or Hurricane Katrina in 2005 (Umlauf et al., 2005; Manuel, 2006). Aside from food production, climate change also restraints people from having food avail-able and access to it. Extreme weather events can damage food storage. When it gets warmer, air conditioning and refrigeration are needed, which can get expensive, and sometimes there are problems with electricity. If it does not work, the harvested food cannot be stored and can get ruined or no longer be healthy to eat (FAO, 2008; James, 2010). Even though most research-ers argue that climate change negatively affects agriculture, some studies have found a positive correlation between global warming and agriculture. This research mostly focused on industrial countries and less on developing countries.

Climate change also forces people to leave their homes, which makes them vulnerable to food insecurity. Internally displaced persons (IDPs) are often forced to leave because of climate change and conflict; two of the three drivers reviewed here. McGregor (1994) addressed the nexus of climate change, forced migration, and food insecurity because already in 1994 there have been many involuntary population displacements due to climate change. Food is one of the most vital needs in displacement camps, where a lot of the IDPs have to live in for many years. They have limited access to it and because they mostly depend on aid, that is not always

11

given and most likely they are not able to consume the amount and diversity needed. Thus, they increase food insecurity in a country (McGregor, 1994; Mooney, 2005).

As this section shows, climate change affects food security in various ways. It mostly af-fects people’s livelihoods through food production, people live food insecure because there is less food available or the available food does not have enough nutrients. This leads to people not being able to access food. Most researchers focused on climate change and its impact on future food security or how it evolves and less on how climate change led to food insecurity. Therefore, it is worth it to explore how climate change has led to food insecurity in Nigeria. 3.2 Economic development as a driver of food insecurity

Previous literature suggests that the economy influences food security. Economic growth is one of the biggest variables to measure the economy and can be closely connected to food security. Studies by several scholars provide proof that the better the economic growth is, the more people are likely to be food secure (Warr, 2014). Hence a weak economy or an economic crisis can lead to food insecurity in a country (Tawodzera, 2011; Musemwa, 2015; FAO et al, 2019). Most research has been conducted in developing countries in Africa because especially developing countries might have thriving economic growth, but at the same time are vulnerable to an economic crisis, because they are often low-income countries, countries in conflict and the countries that are hit most by climate change. All this increases the vulnerability of a popu-lation (FAO, 2019: 59).

For the food security status of a household, the economic situation of the individual is significant as well. Many researchers analyzed unemployment as a factor leading to food inse-curity. It is one of the most explored factors in the field of economic development and food security. Being unemployed puts people into poverty and poor people usually depend on the market to obtain food. They spend a higher percentage of their income on food and conse-quently suffer more likely from food insecurity (Etana and Tolossa, 2017: 64). A lot of other literature argues that unemployment, in particular long-term unemployment, does not only re-sult in people spending less money on food but also causes people to change their diet. Evidence showed that they bought cheaper and less healthy food, which in turn impacted the quality of the daily calorie intake. Other studies also found that consumption patterns change when one gets unemployed (Leichenko and Silva, 2014: 540). Therefore, unemployment can lead to food insecurity on the individual level.

Food prices are another indicator leading to food insecurity (Hertel et al., 2010; Smith et al, 2017). Global food price drops or rises hit especially countries with an uneven trade balance.

12

When a country depends on exporting agricultural goods or minerals, they are more vulnerable to global price volatility (FAO, 2019: 66).

As mentioned above, most scholars argue that often developing countries are affected by economic crises. However, all countries can be affected by a sudden global economic shock. Especially the 2008 financial crisis and the recession that followed has negatively impacted several countries in the Global North. Davis and Geiger (2017) analyzed the demand for food aid in Europe after 2008. They argue that the need for more food aid represents higher food insecurity. They found a rise in food aid and therefore more food insecurity after 2008. Griffith et al. (2013) have, on the other hand, examined the food expenditure of people in the UK and concluded that after 2008 there was a significant change in what people bought. Further studies have also shown identical results in studies covering developing countries (Browning and Crossley, 2009; Huang et al, 2016).

The economic situation people are in affects their state of food security. Hereby it does not matter whether a country is in the Global North or Global South, an economic crisis can hit every country.

3.3 Violent conflict as a driver of food insecurity

The FAO (2017) has asserted that conflict-affected countries have on average higher rates of food insecure people than countries not affected by conflict. Violent conflicts can have short- term effects on people’s nutritional status. This in turn can have long-lasting impacts on their livelihoods. There are several ways where violent conflict affects food security. However at first, it has to be mentioned that the effect conflict has on food security depends on what kind of conflict it is, considering that ‘measuring and categorizing conflict is not straightforward’ (Martin-Shields and Stojetz, 2019: 151). Studies show that the outcome depends on the type of conflict.

Literature shows that conflict often occurs in rural areas, areas that have a lot of agriculture (FAO, 2017: 44). Consequently, violent conflict can especially impact agricultural production. On the one hand, food production can decrease. Cultivation is interrupted, where people depend on agriculture. Often fields were ruined by bombs, or it was simply unsafe to work on them (Baumann and Kuemmerle, 2016). Other times farmers abandoned their lands because farmers or workers were killed, people were forced to leave, fled voluntarily, or were involved in the fighting. This can lead to a labor shortage and therefore fewer people harvesting which then can lead to crop yield loss and food insecurity (Suthakar and Bui: 2008; Eklund, et al.: 2016; Adelaja et al., 2019: 184). On the other hand, agricultural productivity can increase and have a

13

positive impact on the food security situation in conflict areas. Agriculture can be an important income source for the militants. Jaafar and Woerz (2016) analyzed the agricultural productivity of the Islamic State in their controlled area until 2016. Their findings were that it is an important source of domestic food security.

Whereas the scholars above agreed that conflict impacts food security, Adelaja and George (2019) came to different findings. Their focus was also on food production. However, they could not clearly support the argument that conflict has an impact on food security at all. They collected data from household surveys and the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). When analyzing the data, they found that the amount of land that can be harvested does not decrease when the number of attacks goes up. Although at the same time they did find that a higher intensity of the conflict harms the output of agriculture (Adelaja and George, 2019).

Food access to households and individual food consumption has also been researched by people. A reduced production can lead to a decline in food availability which can cause a re-duction in market access to buyers.

An example of long-term impacts of food insecurity due to a conflict are studies that fo-cused on the long-term effect of children that were exposed to conflict at an early age (MartShields and Stojetz, 2019; George et al., 2020). The researchers often used the difference- in-differences approach. They analyzed one region where conflict occurred and one where there was no conflict and compared the results. Bundervoet et al. (2007), for example, studied the impact of the civil war in Burundi on children’s nutritional status over time. They use data from household surveys in civil war affected and non-affected areas. According to their study, chil-dren that were born in regions that at the time of birth experienced violence and had no access to food, due to the disruption of the agricultural production, had lower height-for-age z-score (HAZ) and were therefore not developing the same way as other children. Minoiu and Shemya-kina (2014), as well as Arcand et al. (2015), based their research on Bundervoet et al. and did similar studies in Côte d’Ivoire and Angola. With the same approach, their findings are similar: Children who were exposed to these conflicts while born or in their early childhood had a lower HAZ than others.

Lastly, other scholars focused on the impact on IDPs. As above mentioned, conflict can lead to people fleeing and as noted, they are especially vulnerable to food insecurity. The out-comes are the same as when there are IDPs due to climate change. However, these scholars show that not only climate change can lead to internal displacement, also conflict can be a reason (Tusiime et al., 2013).

14

As this section demonstrates, violent conflict can impact food security directly and rectly. Direct impacts are mostly on the national level and indirect impacts mainly on the indi-vidual level. For example, as the prior section of economic development on food security shows, unemployment, and reduced household expenditure can impact the household and indi-vidual level, this can happen due to interference into markets and food chains (FAO, 2017: 39). Therefore, although not every scholar supports this, it can be said that conflict can have an impact on all different levels of food security.

This literature review shows that these different drivers can lead to food insecurity but are also intertwined. Despite the wealth of literature and the diversity of studies, there is rarely literature disagreeing with the fact that these drivers impact food security in some way. Most scholars argue that the drivers they analyzed lead to food insecurity, but they also state that other drivers have to be acknowledged as interfering variables. They overall agree that each of the drivers can lead to food insecurity, in different parts more than in others. Therefore, when all the drivers are occurring in one country, this country’s population is more likely to be se-verely food insecure.

15

4. Conceptual framework

The literature review shows that the three main drivers affect food security in different dimen-sions. They can affect the global and national level through the availability of food, and the household and the individual level through access to and the quality of food. The concept that fits best hereby is the concept of food security because it covers all these dimensions of food security.

Initially, the concept of food security was ensuring enough food to meet the daily calories necessary. However, simply having a quantity of food available does not prevent people from food insecurity (Ojo and Adebayo, 2012; Burchi and De Muro, 2016, 11). Also, everyone should be able to afford it. This turned into the definition that food security means ‘access by all people to enough food to live a healthy and productive life’ (Pinstrup-Anderson, 2009: 5). People that are food secure do not have to live in hunger or have the fear of starvation (Bala, 2014: 154).

At the World Food Summit in 1996 this definition was revised and further extended and now included the nutritional value, counting in clean water and sanitation to get nutritional well-being and food preferences. Food preference means that the food taken is acceptable under cultural, ethical, and religious values. The definition until today is that ‘Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutri-tious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life’ (World Food Summit, 1996). According to that definition, the concept of food security is ap-plied on three dimensions: Food availability, access, and utilization. Food availability focuses on the national level, food access on the

household level, and food utilization on the individual level. In 2009, on the World

Sum-mit on Food Security, the definition was

re-vised for the last time so far: A fourth di-mension, the food stability, was added (FAO, 2009: 1). Food stability focuses on the function of all three other dimensions. As soon as one of the first three dimensions is not met, there is no food stability and thus, no food security (Pinstrup-Anderson, 2009).

Level Dimension

national Food availability household Food access individual Food utilization

Food stability

Food security

Figure 1: Food security concept. Source: Authors own il-lustration

16

Figure 1 shows the four dimensions, their levels, and how they are connected to food

se-curity. It is illustrated that when the food availability dimension on the national level, food access on the household, and food utilization on the individual level are met, then the dimension of food stability is met and that means food security exists. On the contrary, when one or more of the dimensions are not met, there is food insecurity.

To get measurements on food security, one single indicator or measure does not cover the whole scope of food security. To have a more accurate view and a better understanding of the food security situation, several measures are used (Blekking, 2020: 8). The most accurate un-derstanding can be established, when different indicators that incorporate all dimensions of food security are used. Universal global indicators that measure food insecurity is difficult. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) tries to monitor the worldwide food security situation. For example, they measure in terms of how many people suffer from food insecurity or how many calories are consumed per day (Peng and Berry, 2018). They collect data on all pillars, however often there is a lack of data. Therefore, another way to measure food security is through several household surveys, that are usually conducted on a country level and not necessarily only about food, but about their livelihoods, including indicators that can measure food security (e.g. Van Weezel, 2018; Martin-Shields and Stojetz, 2019). Household surveys are usually conducted by scholars or governments. (Bundervoet, et al., 2007; George et al., 2020). They can show differ-ent aspects that indicate how food secure a household is and how much access they have to food. Therefore, they primarily focus on the second pillar, and depending on the questions asked and who is asked, such surveys can furthermore state the utilization dimension.

Approaching food security through the four dimensions is not the only way to measure food security. One approach, that has been developed by Maxwell (1996), is the coping strategy approach. He argues that coping strategy is an alternative approach to food security on the household level. Depending on what strategy households use, such as changing the diet or re-ducing the number of people in a household (Maxwell, 1996: 159-160). However, coping mech-anisms can be also put into the food access and utilization dimensions because they are con-cerned with the household and individual level.

The concept of food security has developed from a global and national perspective to a household and individual perspective. It shifted from the objective perception to a subjective perception. Today the concept of food security is not only concerned on the national level, but also on the individual level and the livelihoods of individuals. Therefore, all three dimensions are important when measuring food security. Using indicators covering different dimensions,

17

including Maxwell’s coping strategy, can be a good way to measure the food security situation. Therefore, this thesis utilizes this concept.

18

5. Methodology

This chapter describes the research design and presents the data used in the analysis. As previ-ously discussed in the literature review, scholars have analyzed drivers for food insecurity from a different perspective. Three main drivers have been standing out; climate change, economic development, and violent conflict. In this study, these three drivers are independent variables. To analyze how these three factors are influencing food security in Nigeria, it is appropriate to do an in-depth case study.

5.1 Research design and data

Previous research on the factors driving food insecurity has been approached in different ways. Most articles were analyzed longitudinally and quantitatively, but some were in-depth case studies. This thesis does an in-depth case study. It uses a mixed-methods approach, because the data that is used, includes an analysis of existing statistical data, primary data from semi-struc-tured interviews, as well as some reports on this topic. This triangulation of information in-creases the reliability and validity of the findings in this thesis (Halperin and Heath, 2012: 177)

The advantage of an in-depth case study is that it focuses on one single country, which can then be ‘intensively examined even when the research resources at the investigator's disposal are relatively limited’ (Lijphart, 1971: 691). Although a single case study’s results cannot be ground for generalization, it can, however, indirectly contribute to creating a general proposi-tion which can contribute to theory building (Lijphart, 1971: 691).

The analysis is divided into three parts, examining each independent variable and their relationship to food insecurity. Each chapter is examined individually over several years, sup-ported by secondary and primary data.

Secondary data are statistics that help to explain how each of the independent variables affects food insecurity. Each of them uses various statistical data from several sources, which are explained in the following sections.

As primary data, this thesis uses semi-structured interviews with organizations connected to Nigeria to get a deeper understanding of how actors experience the food security situation and its causes. For this, semi-structured interviews were chosen. That way the questions are not restricted and can be adapted individually to the organization. About 25 different non-govern-mental organizations (NGOs) were contacted. Some of them never replied, which can have various reasons. One plausible explanation can be that the Covid-19 pandemic gave their staff extra work because the organizations that have used this excuse. In the end, five semi-structured

19

interviews were conducted either via video chat or as an email interview. The first three inter-views were via video chat. The conversation was recorded, and notes were taken. Both are saved. The other interviews were conducted via email. This can be easier and very convenient because no mutual time has to be found, which is an advantage, especially if both parties are busy and have different schedules (Halperin and Heath, 2012: 296). Covid-19 has made it easier for them to take time in between replying to the questions.

The first two interviews were with the All Farmers Association Nigeria (AFAN) and

Tech-noServe. These NGOs’ are working closely with farmers and help them with issues they are

facing. They were therefore a helpful source when it comes to food production. The next two interviews were with humanitarian aid organizations. Livelihoods Resource Centre and Red

Cross Nigeria. They could talk especially about the way people are dealing with food insecurity

and could speak much about the courses and obstacles of people living in food insecurity have. The last interview was with the Centre for Ecological and Community Development (CECD) which mostly focused on climate change.

5.2 Food (in)security data

The dependent variable in this theses analysis is food insecurity. As defined in chapter 4, when not all four dimensions of food security are fulfilled, there is no food security. The best way to analyze the food security situation in Nigeria and its different drivers is, to have indicators that state something about the first three dimensions of food security; availability, access, and utili-zation. If there is data on these dimensions, the fourth dimension, stability can also be measured.

Only publicly accessible data can be used to measure the food security situation in Nigeria specifically and not all data can be used to show the change in food security across time. As mentioned in the previous chapter, the FAO publishes raw data covering different dimensions. The indicator available, showing data across time, is the prevalence of undernourishment. It is often recognized and utilized by several scholars as the only indicator to show the food security situation (Berry et al., 2015; Martin-Shields and Stojetz, 2019).

‘Undernourishment is defined as the condition in which an individual’s habitual food con-sumption is insufficient to provide the amount of dietary energy required to maintain a normal, active, healthy life’ (FAO, et al., 2017: 95). This indicator incorporates the proportion of the population that is estimated to be at risk of caloric inadequacy and can be used for Nigeria as well. Only a three-year-average is accessible. A yearly measure would probably show more fluctuation, nevertheless, the three-year-average still shows that there has been a significant change towards more food insecurity between 2008 and 2018 (FAO). Because this indicator

20

alone, does not cover all dimensions of food security, another one was chosen, coming from the General Household Survey (GHS): the number of households that faced food shortage in the last 12 months.

To see how credible the data is, investigating the sources is significant for validity and reliability. Especially transparency is important. The FAO database is for the most part a cred-ible secondary source and suitable for this analysis. It is updated regularly and keeps a wide range of indicators that measure food security. The metadata on each indicator is available. It names the timeframe when the data was conducted, the unit of measurement, a contact person, further comments, and its source. They are FAO calculations with additional data from for ex-ample the World Bank, WHO, or national polls (FAO, 2020). In addition to that, the database is from and administrated by the FAO, a United Nations agency.

The other indicator was conducted from the Nigerian GHS. They are also transparent on where they conduct their data and they did not get their data from secondary sources. All data is collected by the authors, which are the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Develop-ment, the National Food Reserve Agency, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the World Bank (NBS et al, 2013: 11). In the reports, where the data was published and the steps on how the data was conducted, how the households were chosen, and how the staff was trained is transparently written down. (NBS et al., 2013; NBS et al., 2014; NBS et al., 2016; NBS et al., 2019). Even though they were not taken in the same interval, they still show the overall trend. The data was collected in four waves over the past decade, in 2010-2011, 2012-2013, 2015-2016, and the most recent in 2018-2019. The survey questions did not change and each time the same households have been participating, which gives reliability and validity to the data and can, therefore, be compared.

The available statistical raw data focuses on the household level (food access) and individ-ual level (food utilization). The interviews are a third indicator to support and strengthen the statistics and give an inside on food availability. It must be emphasized, that the data might be biased, and numbers can be over- or underestimated by the organizations. Furthermore, the data must be used cautiously, because it might not be enough data to determine the Nigerian food security situation. Besides the interviews on food production, there is only statistical data about all Nigeria and there are no reliable regional statistics available, even though it is likely and stated by the interviewees, that the food security situation is different in different regions.

The following illustrates the summary of the sources and variables used in the analysis to measure the Nigerian food (in)security situation:

21

FAO database (prevalence of undernourishment) Food (in)security GHS (food shortage)

Interviews (food security in general)

Source: Authors own illustration

5.3 Climate change data

As much of the literature shows, climate change is one of the causes of food insecurity and is therefore an independent variable to analyze. To answer the sub-question on what impact cli-mate change has on food security in Nigeria, data that shows trends in clicli-mate variability seem appropriate. This can be the trend of rainfall, the occurrence of rain and drought days, or mean temperatures. Descriptive data that is available on trends in climate variability is the trend of yearly mean temperature and rainfall pattern. Further data that can help get to the connection to food insecurity is data on internal displacement which shows how many people fled due to climate change. Further indicators used in the analysis are the interviews. Interviewees were asked about the experience of monthly rainfall change and droughts affecting cultivation. Sec-ondly, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) pub-lishes situation reports that give information about certain strong floods and its impact on peo-ple’s livelihoods in the areas hit.

The statistical data on the climate is retrieved from the Climate Change Knowledge Portal, which is part of the World Bank Group. Even though they do offer metadata information, it is not exactly clear where data comes from. They show that they get it from the Center for Envi-ronmental Data Analysis (CCKP, 2018). However, they do not definitely state where they get the information either. It is imaginable that the data for Nigeria is coming from the Nigerian Meteorological Agency (NiMet), although it is not sure. Consequently, conclusions have to be drawn cautiously. The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) is a source for data on IDPs due to climate change and due to conflict. For Nigeria, they offer data on said two indicators. IDMC is taking its data from several sources: The International Organization for Migration, Nigeria’s national emergency management system, and media articles. This trian-gulation shows that they are a source, that can be used for this thesis, although they state them-selves that the numbers might be estimated to low, due to biases.

OCHA situation reports are also a credible and transparent secondary source. They do joint analysis with local communities and actors in development, peacebuilding, and environment, which offers a variety of sources, and by working together with local sources, the information comes directly from the area they analyze. The situation reports are not necessarily statistical

22

data and raw data cannot be downloaded, however, they gather information into a report that they, as aforementioned, publish after certain disasters, such as floods. Therefore, they focus on specific events rather than some climate data.

The climate change section of the analysis has methodological drawbacks, concerning de-scriptive data. The data available is inadequate and uncertain for the analysis and this has to lead to a cautious analysis.

The following illustrates the sources and indicators used in the analysis to measure climate change and see whether it is a cause of food insecurity:

Climate change Climate Knowledge Portal (mean temperature; mean rainfall) OCHA reports (flooding) IDMC (IDP due to

cli-mate change)

Interviews (experience about droughts and rainfall)

Food (in)security

Source: Authors own illustration

5.4 Economic development data

Previous literature argues that whether somebody lives in food security is often also influenced by the countries’ current economic performance. Thus, economic development can be a cata-lyzer for food insecurity and is one of the three independent variables in this thesis. To analyze the economic development as a cause for food insecurity and answer the sub-question of what impact Nigeria’s economy has on the food security situation, data has to provide information about the economy in Nigeria and must be compatible with the given food security data.

An economy can be measured through multiple indicators. In general, the GDP can be a relevant summary of the overall economic performance (FAO, 2019). Therefore, GDP and eco-nomic growth are the first indicators to use in the analysis.

Further indicators to understand the economic situation in Nigeria and how it has evolved across time are the trade balance and products that are predominantly exported. Moreover, food inflation and the unemployment rate are used as secondary data. qualitative data and primary source, that contributes to the analysis are the interviews.

23

The secondary data is taken from two different sources: The World Bank and UN Comtrade Database. The World Bank shows a pool of statistics covering several areas from many different sources. This database is publicly accessible and is updated regularly. The indicators itself do not only come from the World Bank. The metadata with its source for every single indicator can be downloaded on their website. The GDP and GDP growth indicators are gathered by the World Bank and OECD National Accounts data files. Other indicators, for example, the unem-ployment rate for Nigeria, are collected from several sources, including from the Nigerian gov-ernment and the International Labour Organization (World Bank).

The second source where data is drawn from, is the UN Comtrade Database, a trade branch of the United Nations Statistic Division. This database offers trade statistics. They, for example, provide data on trade between two countries or data on the export and import of one single country. This database can bring information on Nigeria’s trade balance and how it evolved.

Both databases are reliable and valid sources because they are very transparent in how they work, where they get their data from, and their operationalization. For every single indicator, they have noted its source and it can, therefore, be traced back. The databases, together with the interviews are good sources to utilize. Though the data then is taken from credible sources, it also has to be analyzed with caution, because the World Bank gets secondary data from gov-ernments and sometimes the govgov-ernments are not reliable, due to lack of funding, or corruption.

As stated in this section, most data used in chapter 6.3 are descriptive data. The following shows the sources and indicators to measure whether economic development is a cause for food insecurity and in what way:

Economic development

World Bank

(GDP, GDP Growth; food inflation; unemployment)

UN Comtrade (trade balance; export)

24

Food (in)security

Source: Authors own illustration

5.5 Violent conflict data

According to existing literature, the presence of conflict plays an important role in how food insecure somebody is. Thus, a third independent variable chosen to analyze in this thesis is the Boko Haram conflict in Northeast Nigeria. To measure the food security situation in Nigeria and its relation to the northeastern conflict, especially interviews are good as a primary source. To get statistical data that can be compared to the FAO and Nigerian GHS data is data about the number of conflict and the fatalities that happened over the years since the Boko Haram insurgency began. As Adelaja and George state in their paper that longitudinal data for com-parison is limited, I found that this is true and it was difficult to get the right data for this anal-ysis.

There are several databases available that measure conflicts. Previous literature that used quantitative data usually either worked with the UCDP or ACLED. After consideration of what database fits best to the Boko Haram Insurgency, ACLED was chosen. This dataset offers in-formation on different kinds of violence in real time, broken down into the date and place of the event, the type of violence, and the actors involved (ACLED, 2019). Including the exact source for each event and even quotes that source to show that it was precisely taken from there.

According to ACLED, their data is collected by experienced researchers. However, it is primarily taken from secondary sources, but to make sure that the data is accurate and not bi-ased, ACLED uses a variety of sources and does not only trust one source.

In the case of the Boko Haram insurgency, ACLED released a statement, where they clarify that, since the split of Boko Haram, it is hard to separate events from who of the different factions of Boko Haram was involved. They cannot guarantee to get it right. The reasons they state are logical. In Nigeria, their sources are different media channels. These do not always differentiate between the factions and consequently, ACLED codes them as one. This solution might not be the best, nevertheless, in this theses case, because all the factions are part of the Boko Haram insurgency and part of Nigeria’s conflict, it does not matter whether they are re-ferred to as one. Only data from Boko Haram is extracted from the database because it is the main conflict in Nigeria and even though mostly happening in northeastern Nigeria, the food security situation in the whole country is more or less affected because even though in most regions agriculture is possible, the majority of cultivation is also happening in northeastern

25

Nigeria and when nothing can be harvested food insecurity can affect the whole country (ACLED, 2019a). For Nigeria, ACLED was the most reliable conflict database.

Further data for the analysis, besides interviews, are IDPs due to conflict. This data is taken from the IDMC, which is already described in section 5.3.

Interviews, the ACLED database, and IDMC, therefore, seem like three sources this thesis can rely on. The following graph shows the sources and indicators used in the analysis to answer the third sub-question on what impact the Boko Haram Insurgency has on the food security in Nigeria:

Violent conflict/Boko Haram insurgency

ACLED

(Number of conflicts and fa-talities)

IDMC

(IDPs, due to conflict)

Interviews

Food (in)security

26

6. Analysis

The following chapter shows the analysis of the thesis. With the help of all the data described in the previous chapters, this chapter analyzes said data. Previous scholars mostly approached their article by first conceptualizing and analyzing food security (e.g. Martin-Shields and Sto-jetz, 2019). Here it also seems appropriate to first examine Nigeria’s food security situation across time, because to analyze the different drivers, it is necessary to have the food security situation itself already laid out. After that, each of the independent variables and their relation-ship to food security is analyzed individually.

6.1 Food security situation in Nigeria

As shown and explained in previous chapters, food security in Nigeria is analyzed through data from the FAO database, the Nigerian GHS as well as interviews. This section shows evidence that there is a significant amount of people facing food insecurity in Nigeria. All conducted interviews with the NGOs have agreed that food insecurity is visible all over the country. Ac-cording to all of them, the food security situation worsened over the past years. They mentioned that since the Covid-19 outbreak it has gotten even worse and it will not get better in the next few years, but there are no evidential facts about it yet.

Aside from the interviews, the following descriptive statistics from the FAO, figure 1.1, and the GHS, figure 1.2, prove that many Nigerians are food insecure. The two figures are focusing on different factors, but together both show that there is a trend towards more food insecurity.

Figure 1.1 shows how food security has changed over time. Each measuring period has

been conducting its data in the same way and can, therefore, be compared. It indicates that there has been quite a change since around 2008. As shown in the figure from 2008-2010 the per-centage of undernourishment has been constantly on the rise. At first, it is slowly rising, but looking at the years from 2014-2016 and 2015-2017, there was a drastic rise, with an increase of almost two percent from 9,6% in 2014-2016 to 11,5% in 2015-2017 and after this again another two percent to 13,4% in 2016-2018. Due to the fact, that these numbers are always only a three-year average, it can be said that 2014-2016 was another significant turning point in the Nigerian food security situation.

27

Figure 1.1:2Prevalence of Undernourishment (3-year average), 2000-2018. Source: FAO Indicator (2019).

Figure 1.2 is from the GHS and demonstrates the percentage of households facing food

shortage in the last 12 months. In one decade, the number of households experiencing a food shortage has increased from barely 10% in 2010-2011 to over 31% in 2018-2019. Successively households are struggling with getting enough food regularly.

Figure 1.2:3Households facing food shortage. Source: GHS Indicators (2010-2011; 2012-2013; 2015-2016; 2018-2019). 6 6 6,1 6,2 6,5 7 7,8 8,6 9,6 11,5 13,4 5 7 9 11 13 15 2006-08 2007-09 2008-10 2009-11 2010-12 2011-13 2012-14 2013-15 2014-16 2015-17 2016-18 % Years Prevalence of Undernourishment 9,9 11,1 19,6 31,6 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 2010-2011

Wave 1 2012-2013Wave 2 2015-2016Wave 3 2018-2019Wave 4

%

Years

28

From wave 1 to wave 2, the number has not increased significantly. This can be because there was no pause between both waves. The other waves have one year without GHS in be-tween. The graph shows that there was a significant rise from wave 2 to wave 3 and then again from wave 3 on to wave 4.

Compared to figure 1.1, this graph can also show one of the turning points that can be interpreted in the FAO figure. The prevalence of undernourishment has risen quite fast since 2013. Before 2013 it rose, but 2012-2014 it started to make bigger jumps.

When somebody suffers from food insecurity, they use various coping mechanisms to get to their typical dietary intake. Coping mechanisms can be another indicator to show how food insecure a household is, or how the household distributes the food, which shows something about food utilization,

The interviewees were also asked about the coping mechanisms. They argued that the cop-ing mechanisms people choose or are forced to use, show how much they suffer from food insecurity. TechnoServe has stated that most of the communities they work in, help each other at first because there is strong solidarity within the community. They all expressed that when households or individuals are selling property or livestock just to get food, they are in extreme need of food because selling property is the last way out.

Although the different data cannot be put into direct comparison, these different indicators together show a pattern that Nigeria is currently struggling with food security and that the food security situation itself has worsened over the years and more and more visible. The following sections of this chapter are analyzing the possible reasons for this food insecurity.

6.2 The importance of climate change

According to previous research, climate change is one big driver for food insecurity. Most at-tention has been given to the food availability dimension. Research has especially found a pos-itive correlation between climate change and the beginning of the food chain; cultivation and food production. However, food access has also been discussed. This following section exam-ines and answers the sub-question: What impact does climate change have on food security in Nigeria? It also shows whether the findings are similar to previous literature. However, due to the lack of data, the results must be taken cautiously.

Some statistics were found that can help to explain the climate change over the years in Nigeria. These are examined first. After that, the interviews conducted help to explain in what

29

way and how much climate change influences food security. As described in the research de-sign, the interviewees were mostly talking about the North of Nigeria, where most food pro-duction takes place.

The following figures show the mean temperature and the mean rainfall and say something about the trend of climate across time. In figure 2.1 the yearly mean temperature from 2000 until 2016 is illustrated. This timeframe was chosen to show that there has been a significant change in the mean temperature up until 2016.

Figure 2.1:4Yearly mean temperature in Nigeria, 2000-2016. Source: Climate Knowledge Portal (2020).

The coldest year measured in this period was in 2000. It can be said that 2009 and 2010 2016 were on average very warm years. While the trend in mean temperature inclines, there were still years above or below the average. However, in total, the mean temperature trend has been going up half a degree. This shows that Nigeria also experiences a temperature rise, that has significantly changed in the past 20 years.

The next figure shows the rainfall pattern. It also shows the years 2000 until 2016. The overall trend is in line with the mean temperature. While the temperature is going up, the amount of rainfall is decreasing. Despite that, when comparing years, it does not mean that warm years have had less rainfall on average. It is not necessarily connected.

26,2 26,4 26,6 26,8 27 27,2 27,4 27,6 27,8 28 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 °C Years

30

Figure 2.2:5Yearly mean rainfall in Nigeria, 2000-2016. Source: Climate Knowledge Portal (2020).

Therefore, it is hard to say that these two figures can be compared directly to food insecu-rity. What they tell is, that the climate is overall changing and that Nigeria is affected by climate change as much as other countries. The connection to the food security situation is not given in solely taking these graphs into account. Further sources, that do not only show the average are more appropriate to directly compare to food insecurity.

OCHA situation reports show that there has been a significant flood in 2012 that is con-nected to the change of climate. According to OCHA, it was the ‘worst flooding in more than 40 years’ (OCHA, 2012). To this flood, there was more than one situation report, starting right after the flood in July 2012 until the end of October. They state how much and in what way food security is in danger. They note that access to the markets has been interrupted and wrote about obstacles in the distribution of food in displacement camps. This is one sign that can directly connect Nigeria’s food insecurity to climate change. Another matter OCHA focused on were IDPs, which is furthermore displayed in figure 2.3. It shows the number of IDPs in Nigeria due to disasters. In 2012 there were almost 4 million IDPs due to weather disasters and accord-ing to IDMC most of them were connected to said floodaccord-ing. The interviewees from the Red Cross and the Livelihood center have both said, that IDPs are some of the most vulnerable people to food insecurity. They are depending on humanitarian aid, but due to restricted re-sources, not everybody received aid and has to suffer from undernourishment and food insecu-rity. 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 m m Years Yearly mean rainfall

31

Figure 2.3:6IDPs due to disasters, 2009-2018. Source: Internal Displacement Monitoring Center (2020).

Besides making the connection between the IDPs and food insecurity, all interviewees have confirmed that climate change is an overall major issue in Western Africa, including Nigeria. They argued that climate change is a slow process that is influencing the country drastically and it has a big impact on food security. They mostly connected climate change to food pro-duction, the food availability dimension. As the Red Cross representative put it into one sen-tence: ‘Climate change affects the crop and livestock production’. The Red Cross and AFAN are in particular in contact with small-scale farmers and talked about one obstacle farmers face: The seeds cannot be planted when there is no rain during planting season. Farmers must wait until it rains, which means that the products cannot be harvested on time and might not be harvested at all because the growing season moved. Especially the storage has been mentioned here. Many of the common seeds cannot be stored longer than six months and the issue is ex-actly that the farmers have to wait for the rain because when these seeds are planted during the dry season they will not grow. Both, storing them too long or planting early can lead to harvest failure. At the same time, when there are heavy rains or floods one year, harvest can also be lost. This leads to fewer crop yields, more demand, and higher food prices. Hence the farmers and their cultivation are depending on the weather.

The interviewees supported the connection between climate change and food insecurity in Nigeria. They said that in 2013 a lot of harvests were lost due to the 2012 flooding and they also said that over the past years, less could be harvested and needs for food aid continuously rose because the North tends to desertification.

0 500 000 1 000 000 1 500 000 2 000 000 2 500 000 3 000 000 3 500 000 4 000 000 4 500 000 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 N um be r of P eo pl e Years IDPs due to disasters