Challenging the Stereotypical

Roles of Mentorship

How reverse mentorship could be used as a tool to foster diversity

within male-dominated organisations

BACHELOR THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 hp

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Marketing Management AUTHORS: Elin Antus Flyckt & Linnéa Asklöf

TUTOR: Nadia Arshad JÖNKÖPING Spring 2020

Acknowledgements

We would like to emphasise our gratitude to everyone who has been contributing to this thesis by supporting, motivating, and participating. First of all, we would like to sincerely express our gratefulness to our tutor Nadia Arshad who patiently has provided us with helpful insights, wisdom, and irreplaceable constructive feedback.

Second of all, we would like to thank the participating organisations and each respondent for their enthusiasm and for providing valuable information and perspectives that have enabled us to accomplish in-depth findings and a thorough analysis.

In addition, we would like to truly express our appreciation to Anders Melander who has been giving us guidance during the process of our thesis. We would also like to send love to our friends and family who have been supporting us throughout this rollercoaster. A special thank you to Beatrice Carpvik for planting the idea of reverse mentorship and to Alexandra Greus for mentoring us.

Lastly, we would like to thank you for taking the time to read this thesis and for showing interest and commitment to this significant topic.

Abstract

The purpose of this study has been to examine how reverse mentorship could be used as a tool to foster diversity within dominated organisations. This has been done by analysing male-dominated organisations’ perceptions and attitudes towards implementing reverse mentorship. Additionally, the authors investigated potential challenges and success factors with the reverse mentoring model along with the outcomes that the programme could generate. With the forthcoming generational shift, traditional mentorship has started to lose its relevance which has resulted in an increased demand for alternative mentoring models that could be used to utilise the diversity that the shift could contribute with.

A qualitative research approach was applied, where the primary data collection process was initiated with ten semi-structured interviews with the male-dominated organisations: Volvo Cars, Volkswagen Group Sverige, and Spot On. Volkswagen Group Sverige represented the perspective of practical experience from their reverse mentoring programme. Volvo Cars and Spot On, on the other hand, contributed with their theoretical perceptions and understanding of the phenomena since they had not implemented the concept yet.

The research recognised six themes where the authors could distinguish significant insights that enabled them to draw conclusions and extend the conceptual framework. In particular, the findings generated new perspectives of the challenges with reverse mentorship and how they could be translated into success factors if utilising them in an efficient manner. Consequently, a reverse mentoring programme could derive positive outcomes for the individual as well as for the organisation as a whole. The findings and analysis further indicated that the concept could be used as a tool to foster diversity, not only within male-dominated organisations but also within other organisations, as diversity is an everlasting topic.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ... 1 1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Problem Formulation ... 3 1.3 Purpose ... 5 1.4 Delimitations ... 5 1.5 Definitions ... 6 2. Frame of Reference ... 72.1 Method for Frame of Reference ... 7

2.2 Diversity ... 8

2.2.1 Diversity Within the Workforce ... 8

2.3 Mentorship ... 10

2.3.1 Traditional Mentorship ... 10

2.3.2 Alternative Mentoring Models ... 12

2.3.3 Reverse Mentorship ... 13

2.4 Conceptual Framework ... 20

3. Methodology & Method ... 22

3.1 Methodology ... 22 3.1.1 Research Philosophy ... 22 3.1.2 Research Approach ... 22 3.1.3 Research Strategy ... 24 3.2 Method ... 25 3.2.1 Data Collection ... 25

3.2.2 Population & Sampling ... 26

3.2.3 Question Design ... 28

3.2.4 Test Interviews & Question Formulation ... 29

3.2.5 The Interviews ... 29

3.2.6 Data Analysis ... 33

3.2.7 Data Quality ... 34

4. Empirical Findings & Analysis of Findings ... 36

4.1 Reverse Mentorship... 36

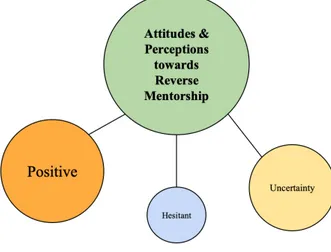

4.1.1 Attitudes & Perceptions towards Reverse Mentorship ... 36

4.1.2 Challenges with Reverse Mentorship ... 39

4.1.3 Success Factors when Implementing Reverse Mentorship ... 45

4.1.4 Positive Outcomes with Reverse Mentorship ... 50

4.2 Diversity ... 56

6. Discussion ... 64

6.1 Limitations ... 64

6.2 Practical Implications for Male-Dominated Organisations ... 64

6.3 Theoretical Contribution & Suggestions for Future Research ... 65

7. References ... 66 8. Appendices ... 75 Appendix 1 ... 75 Appendix 2 ... 76 Appendix 3 ... 77 Appendix 4 ... 78 Appendix 5 ... 79

1. Introduction

___________________________________________________________________________ This chapter will introduce reverse mentorship and explain how and why the mentoring model has been established. Thereafter, the problem and the purpose will be formulated to present the research questions of this study. Subsequently, the delimitations will be presented and lastly, definitions within this research will be clarified.

___________________________________________________________________________

1.1 Background

In 1999, the former CEO of General Electric, Jack Welch, acknowledged the knowledge differences in the company’s hierarchical levels, where a large number of the more experienced employees had none or limited expertise of the current technologies and the Internet. Consequently, Welch arranged so that 500 of the company’s top managers encountered a junior employee in the lower hierarchy as a mentor to attain their expertise of new technologies and the Internet (Dunham & Ross, 2016). This was one of the first attempts of reverse mentorship, and since then, this practice has been applied in several large global corporations (Chaudhuri & Ghosh, 2012; Greengard, 2002). Today, several authors define reverse mentorship as a relationship where a junior employee acts as a mentor for a senior employee to acquire new knowledge that the junior employee obtains (Clarke, Burgess, van Diggele, & Mellis, 2019; Kaše, Saksida, & Mihelič, 2019; Kram, 1996; Kram & Hall, 1996; Murphy, 2012).

Recalling back to the origin of mentorship, traditional mentorship can be defined as a relationship where a senior individual, with wisdom and experience, takes the role as a mentor for a younger less experienced individual (Harvey, McIntyre, Thompson, & Moeller, 2009; Kram, 1983). Since then, mentorship has been a phenomenon widely used in organisations and has been recognised as the most imperative tool for retaining and promoting workers (Bova & Kroth, 1999). The existing literature identifies mentorship as helpful and powerful when aiming to understand and advance organisational culture, bestow admission to informal and

receiving a promotion, and are more satisfied with their career choices (Allen, Eby, Poteet, Lentz, & Lima, 2004).

Taking the history of traditional mentorship into consideration, the understanding of the evolution of reverse mentorship can progress. In the 21st century, the relevance of reverse mentorship has increased and developed into one of the most popular alternative mentoring models (Brînzea, 2018; Kram, 1996; Kram & Hall, 1996). The phenomenon has further become more valuable to investigate since professional careers have shifted from traditionally linear and stable into boundless and unpredictable (Arthur, Inkson, & Pringle, 1999; Hall, 2002). Chen (2013) further addresses the dynamic shift by explaining that organisations have chosen to apply alternative methods of mentorship due to the rapid changes of organisational structures and the generational shift. Continually, alternative mentoring models have become popular as a result of the growing diversity focus which demands a mix of gender, race, age, sexual orientation, as well as values and beliefs in the organisation (Lopez, 2013). Lastly, Brînzea (2018) addresses that in line with the advancing technology and with the younger generations entering the workforce, reverse mentorship could be a solution to meet the changes in the organisational environment.

However, even though multiple organisations globally have used reverse mentorship, there is still a scarcity of information about reverse mentorship and how it could be used as a tool to foster diversity within organisations that obtain an inadequate level of it (Clarke et al., 2019; Kaše et al., 2019; Lopez, 2013). Therefore, this study will focus on examining if reverse mentorship could be a suitable mentoring model to foster the growth of diversity within male-dominated organisations.

1.2 Problem Formulation

According to Kaše et al. (2019), there is limited research about reverse mentorship and the phenomenon still needs to be explored further. The research so far has mainly been limited to how reverse mentorship has been used to increase the competence of technology for senior employees. Thus, research reflecting any other positive outcomes of reverse mentorship is scarce. Some authors mention diversity as one of the positive outcomes of the reverse mentorship, however, this has not been studied in depth (Chaudhuri & Gosh, 2012; Legas & Sims, 2011; Lopez, 2013). Lopez (2013) expands on this by addressing that the existing mentoring literature has generally ignored the aspect of diversity linked to mentoring. However, some researchers claim that reverse mentorship can result in an increased understanding of the importance of diversity as it fosters cross-generational relationships (Chaudhuri & Gosh, 2012; Legas & Sims, 2011). Messmer (2006) further states that a successful organisation will be the one who takes advantage of the different abilities, aspirations, and work styles that a diverse team contributes with. Along with a forthcoming generational shift in the workforce, organisations do not only need to concentrate on cross-generational wisdom sharing but also on the implementation of efficient methods of leveraging diversity within cross-generational relationships (Chaudhuri & Gosh, 2012). Thus, traditional mentoring models have started to lose relevance and organisations are seeking for alternative mentoring models to meet the new demand of generational diversity and cross-generational learning, where it is suggested that reverse mentorship could be used (Chaudhuri & Gosh, 2012; Chen, 2013; Legas & Sims, 2011).

In line with the scarcity of literature about the link between reverse mentorship and additional positive outcomes, such as diversity (Chaudhuri & Gosh, 2012; Legas & Sims, 2011; Lopez, 2013), the authors argue that it is relevant to further investigate how and why diversity could be a positive outcome derived from the reverse mentoring model. To study the aspect of diversity with regard to reverse mentorship, the authors have chosen to limit the primary data collection process from organisations that traditionally lack diversity, which inter alia could be termed as homogenous organisations (Campuzano, 2019). As mentioned, the previous literature acknowledges that diversity could be an outcome of reverse mentorship, where a

relevance of investigating if a homogenous organisation could use reverse mentorship as a tool to develop their diversity.

Hence, for this study, the authors have chosen to analyse one type of homogenous organisation, namely male-dominated organisations. A male-dominated organisation can be considered as homogenous as it is an organisation reflected by a more traditional business environment that is created, maintained, and controlled by men since its origin (Campuzano, 2019). As a result of that, one of the most common shortfalls of diversity is gender diversity, as the organisations are mainly represented by one gender (Campuzano, 2019; Wright, 2016). What further distinguishes a male-dominated organisation are stereotypical masculine traits such as aggressiveness, decisiveness, risk-taking, and competitiveness (Campuzano, 2019). Moreover, the scarcity of diversity could result in a number of issues, such as the belief that minorities do not have the ability to lead (Campuzano, 2019) or an increased gap between the generations (Legas & Sims, 2011). With the problem formulation in mind, the purpose of this study is, therefore, to investigate how reverse mentorship could be used as a tool to foster diversity within male-dominated organisations.

1.3 Purpose

The importance of fostering diversity within male-dominated organisations are becoming more essential as the scarcity of diversity could, as mentioned, result in several issues for the organisation (Campuzano, 2019; Legas & Sims, 2011). Therefore, this research paper will examine the perceptions and attitudes of male-dominated organisations about using reverse mentorship along with investigating the challenges, success factors, and outcomes that a reverse mentoring programme could generate. Consequently, the purpose of this study is to discover if reverse mentorship could be used as a tool to foster diversity within a male-dominated organisation, answering the following research questions:

RQ1: What are male-dominated organisations’ attitudes and perceptions about implementing

a reverse mentoring programme as a tool to foster diversity?

RQ2: What are the success factors for implementing a reverse mentoring programme within

male-dominated organisations?

1.4 Delimitations

This study will examine if reverse mentorship could foster diversity, exclusively from two perspectives: (1) the perspective from one male-dominated organisation who have implemented reverse mentorship, and (2) the perspective from two male-dominated organisations who have not yet implemented reverse mentorship. Male-dominated organisations will be examined as they are not yet fully diverse, and are, therefore, in need of finding methods that could be used to respond to the diversified generation entering the workforce (Campuzano, 2019). Additionally, this study will examine the concept of reverse mentorship along with its challenges, success factors, and its outcomes. Nevertheless, this study will not contribute with a practical guide on how to execute a reverse mentoring programme. Lastly, this research will be limited to companies operating in Sweden.

2. Frame of Reference

___________________________________________________________________________ This chapter will establish a fundamental understanding of diversity to continue describing the concept mentorship as diversity training. Firstly, the method of the frame of reference will be described as a guidance of the process. Thereafter, diversity and mentorship will be described to further provide a theoretical basis for reverse mentorship, elucidate its similarities and differences from traditional mentoring, and further clarify the possible challenges along with the positive outcomes of reverse mentorship for individuals and organisations. Lastly, based on the literature, a conceptual framework will be established and presented.

___________________________________________________________________________

2.1 Method for Frame of Reference

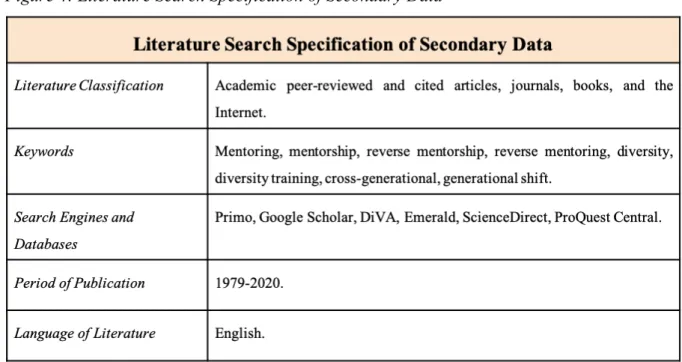

The process of finding and analysing existing literature within the field was initiated by the secondary data collection process. The search engines Jönköping University’s library database Primo and Google Scholar were used for the initial search with keywords such as mentoring, mentorship, reverse mentorship, reverse mentoring, and diversity. The authors recognised that the existing reverse mentorship literature was limited and that the connection to diversity was rare (Lopez, 2013). Therefore, the keywords were extended to diversity training, cross-generational, and generational shift. These articles contributed with a deeper understanding of reverse mentorship and how it could be used to foster diversity. With support from Saunders and Lewis (2012), the authors had a qualitative judgement criterion to follow for the selection process of the literature. Elements such as the number of citations, if being an academic peer-reviewed article, and whether the study was published recently were used when selecting articles. To increase the relevance of the literature, the authors decided to select information from the last decade. However, due to the scarcity of research within the field, it was relevant to study highly cited literature from 1979 and onwards. This enabled an understanding of the development of mentorship and why the relevance of traditional mentorship is decreasing, along with the reasoning behind alternative mentoring models becoming more popular.

2.2 Diversity

2.2.1 Diversity Within the Workforce

Since the early 1990s, and in line with the changing demographics and globalisation, diversity has become a popular topic for organisations (Hite & McDonald, 2007). There are multiple definitions of diversity, where Jackson, May, and Whitney (1995) define it as “the presence of differences among members of a social unit” (p.217). Likewise, Combs and Luthans (2007) define diversity as the range of different genders, ages, races, abilities, and ethnicities within a group of individuals. Thus, within the term diversity, there are multiple of different types of diversity such as gender diversity, age diversity, generational diversity etc. (Jackson et al., 1995; Legas & Sims, 2011; Parry, 2018).

According to Cho and Mor Barak (2008), diversity and involvement within an organisation are two of the most crucial factors for encouraging the employees to contribute with commitment and performance within an organisation. Further, the authors refer workplace diversity to be a recognisable factor that may have damaging or beneficial effects on the organisation, depending on how the differences are dealt with. The factors are based on common perspectives within a cultural context (Cho & Mor Barak, 2008). Commonly, de Meuse, Hostager, and O’Neill (2007) address that workplace diversity are generally considered to be beneficial for the organisation in terms of social, legal, strategic, and competitive assets. Lastly, Combs and Luthans (2007) argue that it is vital that organisations operate in line with the emerging issues with equality and fairness.

Younger generations are continuously entering the workplace with new perspectives, expectations, and values which gives the managers in organisations new opportunities and challenges that they need to adapt to (Brînzea, 2018; Chaudhuri & Gosh, 2012). In contrast to the older generations, younger generations have a higher tolerance of diversity as they have been exposed to differences in terms of lifestyles, cultures, gender, races, and sexual orientations to a higher extent, both through school and the Internet. Due to this, they are extraordinarily comfortable with diversity which will contribute to new demands in the organisational environment as well as on the employers (Beck & Wright, 2019; Bell & Narz, 2007; Chaudhuri & Gosh, 2012).

Diversity Training

To meet the increased importance and interest in diversity, organisations have implemented diversity training programmes. Researchers have agreed upon the importance and effectiveness of using training as a tool to develop into a more diverse organisation (Hite & McDonald, 2007). According to Yang and Matz-Costa (2018), diversity training is vital to develop a mutual understanding of how to collaborate with supervisors who are different from oneself, for instance, someone considerably younger than oneself.

Diversity training is unmistakably a common strategy used by organisations to understand the differences in values and perceptions of different individuals as well as minimise biases and stereotypes (Legas & Sims, 2011; Yang & Matz-Costa, 2018). However, it is not enough with just understanding the differences to become a successful business, organisations also need to implement diversity training programmes where the organisation capitalise the variation of assets, motivations, and ways of working by the different generations (Legas & Sims, 2011). Legas and Sims (2011) further address that mentorship could be a successful strategy to leverage diversity and close the gap between the generations. Implementing a mentoring programme could derive intergenerational learning where both parties, from different generations, could learn from and with each other (Brînzea, 2018; Schlimbach, 2010). Lastly, one of the main challenges with diversity is to create an efficient and effective intergenerational communication within the organisation. This is often resulting in misunderstandings that creates a larger gap between the generations, which derives unsuccessful results for the organisation. Therefore, it is imperative that organisations implement strategies to devote effort into diversity (Legas & Sims, 2011).

2.3 Mentorship

2.3.1 Traditional Mentorship

Kram (1983) was one of the first to define mentorship as a relationship where a senior employee would take the responsibility to provide advice and counsel a junior employee. Likewise, Harvey et al. (2009) define traditional mentorship as an exchange of knowledge and support from an experienced senior mentor to an inexperienced junior at the beginning of their career. “Protégés observe, questions, and explore; mentors demonstrate, teach, and model...” (Bova & Kroth, 1999, p.10) Previous studies have found that mentoring functions are advantageous for both individuals and organisations (Allen & Eby, 2007; Allen & Finkelstein, 2003; Ragins & Kram, 2007; Ragins & Scandura, 1999). Richardson, Levinson, Darrow, Klein, Levinson, and Mckee (1979) were the first to argue that mentorship is beneficial for a person’s personal growth and professional career. Harvey et al. (2009) later advance on this argument and claims that traditional mentorship improves career development for protégés and contributes to increased personal growth and professional development for the protégé through mental support given by the mentor. Similarly, Murphy (2011) argues that a mentor within a traditional mentorship supports future generations by transferring their knowledge and experiences.

Different mentoring functions has been defined throughout the existing literature, where three functions have been identified: (1) career development, (2) psychological support, and (3) role modelling (Noe, 1988; Scandura & Ragins, 1993). These functions have further been referred to as advantages of using mentoring programmes within an organisation by more recent literature (Burdett, 2014; Cooke, Patt, & Prabhu, 2017; Curtin, Malley, & Stewart, 2016; Harvey et al., 2009; Murphy, 2012) and can, therefore, be considered as relevant to consider when implementing a mentorship programme in an organisation.

Mentor

As defined by Kram (1983), a mentor in a traditional mentorship is a senior employee who acts as guidance for a less experienced junior employee, by, for instance, advising on how to encounter dilemmas in the early stage of the protégés career or by sharing wisdom. According to Kram (1983), the mentor is mainly providing two types of functions to their protégé: (1) career functions and (2) psychosocial functions. The former refers to all actions that aim to assist and prepare the protégé for a hierarchical promotion, such as coaching, sponsoring, and giving challenging assignments, while the latter represents functions that will build trust, intimacy, and interpersonal connections. These functions will increase the protégé’s professional and personal growth, identity, self-worth, and self-efficacy (Ragins & Kram, 2007). Chen (2013) further elaborates on the role of the mentor, consisting of the three mentoring functions, namely career development, psychological support, and role modelling. Career development and psychological support goes in line with Noe (1988) as well as Scandura and Ragins (1993) suggested mentoring functions, where Chen (2013) further argues that these two functions are resulted from the mentor’s capability to transfer up-to-date knowledge that the protégé can apply to their career and personal growth. The third mentoring function, role modelling, adds value in terms of inspiring the protégé to continue their career within the organisation, to take initiatives, and, lastly, to improve their recognition of their responsibilities at work (Chen, 2013).

Protégé

A protégé, also called mentee, is defined as an employee with less experience who often obtains fewer career resources than the mentor (Kram, 1983). The protégé is personally advised, coached, and counselled by its mentor (Broadbridge, 1999; Chao, 1997; Kram, 1983). Allen et al. (2004) found that, generally, a former protégé is more likely to receive promotions and acquire greater salaries, than an employee who has not previously been in a mentoring relationship. Harvey et al. (2009) argue that one of the major benefits for the protégé is that they obtain knowledge and wisdom from the more experienced mentor. Moreover, by previously participating in a mentoring relationship within their career, many individuals are

2.3.2 Alternative Mentoring Models

The initial literature of mentorship acknowledged that alternative mentoring models could be of interest (Eby, 1997; Kram & Isabella, 1985). Continually, with a dynamic and changing workforce environment, where more organisations develop a flatter organisational structure and the leaders from younger generations increases, new perspectives have generated alternative mentoring models (Chen, 2013). Correspondingly, the older workers are entering their retirement age and younger generations, such as Millennials, will continue to embark on the labour market. Lopez (2013) further addresses the issues of power within traditional mentorship and argues that there is a demand for alternative mentoring models. Additionally, Lopez (2013) identifies multiple reasons for using alternative mentoring models, where feminism, co-mentoring, and collaborative mentoring are mentioned as approaches used to acknowledge the growing diversity. Moreover, reverse mentorship has been identified as one of the most popular alternative mentoring models (Brînzea, 2018; Kram, 1996; Kram & Hall, 1996). Therefore, considering that the business structures are becoming more dynamic in line with a generational shift, the traditional mentoring functions are being supplemented with new theories and models, where reverse mentorship could be a useful tool to meet the dynamic and rapid changes in the business environment along with developing a competitive advantage (Harvey et al., 2009).

2.3.3 Reverse Mentorship

According to Murphy (2012), reverse mentorship can be described as an innovative way of mentoring, where a junior employee acts as a mentor for an older employee. The purpose of reverse mentorship is to share expertise and knowledge as well as creating a cross-generational relationship. Furthermore, reverse mentorship can be defined as a modernised and cost-effective professional development tool that benefits from building bridges between generations (Harvey & Buckley, 2002; Hewlett, Sherbin, & Sumberg, 2009). Similarities can be discovered in the article written by Harvey et al. (2009), where reverse mentorship is defined as a paradigm where a newer, younger employee is partnered with a more experienced senior employee to help her/him develop a more in-depth understanding of technology and the dynamic marketplace.

The modern society’s relationship to the advancement of technology is one of the reasons for the progress within the mentoring field. Generally, the younger employees in today’s workforce have a more tech-savvy approach than their senior managers, and, therefore, this creates an opportunity for valuable knowledge to impart (Burdett, 2014). Similarly, Harvey et al. (2009) address the fact that reverse mentorship is effective to use in a high-technology business operating in a dynamic marketplace. On top of that, reverse mentorship can be used to get a better understanding of the younger generations and their perspectives, which in turn will lead to a more profitable company due to the understanding of employees, as well as potential consumers (Harvey et al., 2009).

Already in the late 20th century, research within traditional mentorship found that mentors obtain valuable, work-related knowledge as well as self-rejuvenation from their protégés (Mullen, 1994). These findings are what developed the foundation for what was to become reverse mentorship. Correspondingly, Gerpott, Lehmann-Willenbrock, and Voelpel (2017) declare that the previous findings from intergenerational learning imply that the structure of the reverse mentoring relationship may result in valuable advantages for both members of the dyad. Moreover, this was acknowledged in a case study of a large government department in Australia, where a project was executed and promoted as a reverse mentoring model (Burdett,

Figure 1: Aspirations from a Reverse Mentoring Relationship

Procedures of Reverse Mentorship

The Set-up of the Reverse Mentoring Relationship

Regarding the set-up of the mentor and the protégé, Kaše et al. (2019) argue that there are certain factors the managers need to take into consideration. When choosing an older employee for the protégé role, it is vital that they emphasise the importance of structure and interactivity where the older employee is offered continuous feedback from the manager. On the other hand, when attracting the younger employee as the role of being a mentor, the manager should address a rewarding system for their engagement in the reverse mentoring programme along with mentoring training as this will increase the younger employee to thrive (Kaše et al., 2019). Further, the protégé should respect the skills of the mentor as well as have clear communication about the needs that the protégé have (Clarke et al., 2019). Continually, Kaše et al. (2019) emphasise the importance of both parties having an interest in the mentoring relationship as that will lead to a greater exchange and result of the mentorship.

The Mentoring Sessions in a Reverse Mentoring Programme

In a reverse mentoring programme, the junior mentor and the senior protégé will meet for mentoring sessions, at which the protégé will supply insights of their daily work so that the mentor can provide accurate mentorship (Burdett, 2014; Clarke et al., 2019). This can further be done through shadowing and observations of the protégé’s daily work functions (Burdett,

2014). Further, these coaching sessions could take place weekly or monthly, depending on how the reverse mentoring programme is structured, along with, for how long it is expected to operate (Burdett, 2014; Chen, 2013).

Challenges within Reverse Mentorship

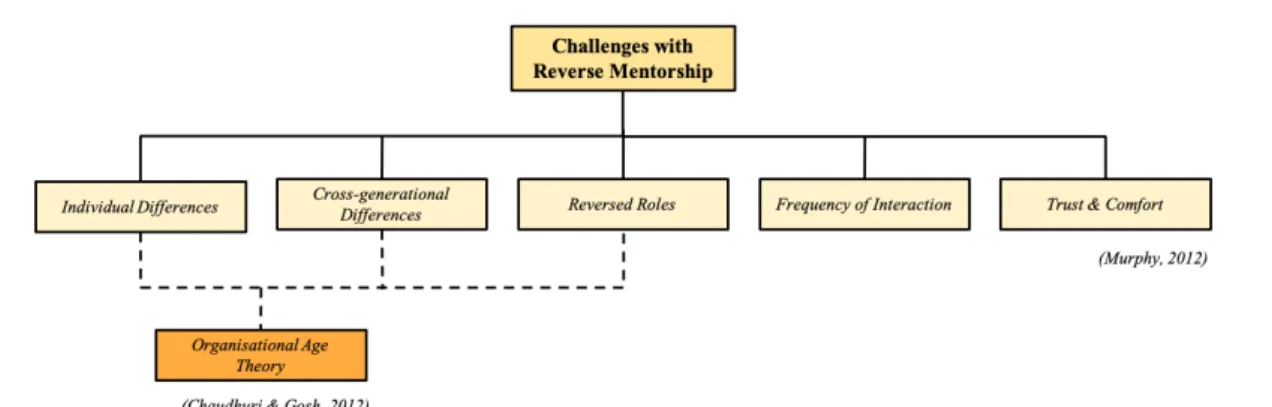

Key Antecedents of Reverse MentorshipAccording to Murphy (2012), five major antecedents could create challenges when establishing a reverse mentoring relationship: (1) individual differences, (2) cross-generational differences, (3) reversed roles, (4) frequency of interaction, and (5) trust and comfort. These five challenges will be described and supported by other authors’ perspectives.

1. Individual Differences

Within traditional mentorship, differences such as gender, ethnicity, and personality have always been a possible challenge for creating a successful relationship between a mentor and a protégé, thus could potentially be a challenge within a reverse mentorship as well. Individuals tend to connect with other individuals that are similar which can result in limitations within personal growth due to gender obstructions, lack of diversity, and stereotypes. These factors may become a challenge and are therefore important to consider when pairing a mentor with a protégé (Murphy, 2012).

2. Cross-Generational Differences

According to Murphy (2012), there are significant differences between the generations in regard to values, behaviour, and personality at the workplace. It is relevant to address these differences as reverse mentorship takes advantage of the similarities and differences between the mentor and protégé, who in most cases represents different generations. Utilising these differences may be relevant to understand to establish a successful and efficient reverse mentoring relationship (Murphy, 2012).

➢ However, in contrast, Brînzea (2018) and Chaudhuri and Gosh (2012) argue that the multigenerational environment along with the advancements in technology derives new

a reverse mentoring relationship can be cross-generational, but that it is not invariably dependent on age, but rather on a willingness to share wisdom. Additionally, Breck et al. (2018) address that reverse mentorship could be an excellent tool to defy the age norms and create a more inclusive society.

3. Reversed Roles

In a reverse mentorship, the junior employee has most likely no experience of previously being a mentor professionally. It is, therefore, highly relevant that the older protégé understands that he/she is in this relationship to learn and has to set aside the fact that they are usually the one in a leading position. Nevertheless, this may be a challenge for the older protégé. Therefore, the protégé needs to be open-minded and accessible for learning through a new perspective (Murphy, 2012).

➢ The Organisational Age Theory

Another challenge that ties in with individual differences, cross-generational differences, and reversed roles presented in Murphy’s (2012) key antecedents is the organisational age theory. Chaudhuri and Gosh (2012) addresses the challenge of age norms and refers to the organisational age theory, which emphasises that age norms can establish stereotypical impressions about which age suits which role in a relationship and the organisation. Age norms, in this manner, are referred to shared assumptions that certain things should be accomplished at a certain age (Chaudhuri & Gosh, 2012). If a young individual is succeeding tasks that are assumed to be accomplished at an older age, the age norms are violated, and other individuals may be concerned about this. This challenge may occur in a reverse mentoring relationship as the mentoring model is violating the stereotypes and norms of a mentorship. As a result of the age norms, the protégé, i. e. the senior employee, may not feel comfortable sharing their needs of development and understanding as they may feel ‘behind the schedule’ according to the organisational age theory and the age norms (Chaudhuri & Gosh, 2012).

4. Frequency of Interaction

Within all types of mentorships, time and energy need to be invested from both parties. This may be perceived as a potential challenge for a reverse mentoring relationship as the junior mentor most likely need to invest time in getting to know the organisation as well as managing multiple new job tasks. This, along with managing and developing a successful reverse

mentorship might be overwhelming. Further, it may also be a challenge for the protégé as he or she needs to find time to commit into the relationship at the same time as devoting time for the other responsibilities that he or she has at the organisation (Murphy, 2012).

➢ Cooke et al. (2017) and Lopez (2013) agree and further identifies that it takes time to build a trusting mentoring relationship and argue that it is important to invest time as it will be a crucial factor for a successful mentorship.

5. Trust and Comfort

To build trust and comfort in the mentorship, it is relevant that the mentor and protégé feel comfortable with each other. This will enable a more open environment where both parties are more confident to reflect and ask questions. According to Murphy (2012), comfort is created when the parties can relate to each other, which is commonly achieved when two individuals’ personalities and identities match, for example, when they are of the same gender or race. A situation where the senior protégé questions the expertise of the junior mentor may occur, and it is, therefore, of high importance that both parties understand that the goal with the reverse mentorship is to learn from the mentor’s expertise through sharing knowledge and skills to the protégé (Murphy, 2012).

➢ Correspondingly to Murphy (2012), multiple studies within the existing mentoring literature addresses the importance of trust within a mentoring relationship. Allen and Poteet (1999) analyse that one of the most important factors for a successful mentorship is trust, which could allow for more open communication. Further, Lopez (2013) argues that characteristics such as trust, understanding, and communication are key factors for effective mentorship. In terms of creating a reverse mentorship to foster diversity, trust may be one of the most imperative factors as it opens up for a safe environment where the parties feel that they can share tensions and thoughts (Lopez, 2013). Cooke et al. (2017) further address the importance of mutual trust and argues that it is when a friendship is created between the mentor and protégé that the opportunities within the mentoring relationship will arise.

Outcomes of Reverse Mentorship

According to Burdett (2014), Chen (2013), and Murphy (2012) a successful reverse mentoring relationship awards both parties, both in terms of their individual learning as well as professional development. Further, Burdett (2014) addresses that the mentoring programme can enhance the organisation through leadership development, knowledge creation and sharing, as well as networking and relationship building.

Outcomes for the Mentor

Leadership development in the form of personal learning is one of the outcomes associated with reverse mentorship which can influence and increase job satisfaction as well as diminish role ambiguity (Lankau & Scandura, 2002). Spreitzer (2006) further acknowledge that these factors grant support to nurture leaders to develop and advance. Continually, Burdett (2014) and Murphy (2012) emphasises that through the reverse mentoring programme, the mentor, i.e. the junior employee, is given the opportunity to display their competence, interpersonal skills, and coaching ability to their superior which may lead to a future promotion within the organisation. The mentor will also obtain essential organisational knowledge (Burdett, 2014), for instance, about informal procedures and gain a deeper understanding of the hierarchy of leadership (Murphy, 2012). Ultimately, reverse mentorship may broaden the mentor’s inter-organisational network, and, therefore, increase their social capital in the organisation, which refers to the capability to have access to the resources of colleagues through social ties (Lankau & Scandura, 2002). Several of the mentioned outcomes for the mentor is supported by more recent literature by Clarke et al. (2019), where it is also addressed that the mentor will practice providing honest feedback to senior colleagues.

Outcomes for the Protégé

The protégé will, as mentioned, gain knowledge as well as develop a clearer understanding of current and emerging trends (Chen, 2013; Murphy, 2012). Further, the understanding of the younger generations and their work values will progress along with the ease for the cross-generational communication (Burdett, 2014). Moreover, just like the mentor, the protégé will expand their social capital within the organisation (Lankau & Scandura, 2002). Correspondingly, Clarke et al. (2019) highlight several positive outcomes for the protégé such as a greater insight into the workplace, inspiration and enthusiasm.

Outcomes for the Organisation

According to Murphy (2012), reverse mentorship is an innovative approach for the talent management of the business. By taking part of the mentoring relationship, the mentor’s and the protégé’s interactions will increase in frequency as they meet more continually and also in quality as their participation will increase the quality and their willingness to deliver good results. This will, in turn, enhance the assessment for leadership development in terms of accuracy and reliability, as they will have more information to base their talent management decisions on. This might be imperative in regard to identifying future leadership talent for the organisation (Murphy, 2012). Moreover, reverse mentorship has been acknowledged as a technique for recruiting and retaining early-career employees. In the Millennial generation, the employees desire ways of being challenged and to feel that they are being seen along with their ideas being heard and appreciated (Meister & Willyerd, 2010). The reverse mentoring programme enables the mentor to be challenged and get appreciation while they are bridging the gap between the generations in the organisation, and finally discover individuals’ incentives as well as disincentives (DiBianca, 2008).

Additionally, Harvey et al. (2009) address that reverse mentorship can simplify and increase the admission of females and minorities to employees in powerful organisational positions within the organisation. Compared to traditional mentorship, reverse mentorship enables a more diverse relationship and avoids the common biases that often occur in traditional mentorship, where mentors often choose protégés that remind them of themselves (Ragins & Cotton, 1991), or selecting the mentor/protégé with the same-sex or same-race (Gibson & Lawrence, 2010). Lastly, the organisation will acquire information in the way that junior mentors will introduce subjects from their individual perspective and experiences, representing the part of the market that organisations spend a lot of resources trying to investigate and figure out (Murphy, 2012).

2.4 Conceptual Framework

This section will present the conceptual framework for this thesis, based on three theories developed in the study made by Chaudhuri & Gosh (2012), Clarke et al. (2019), and Murphy (2012). The first theory (Figure 2) within the conceptual framework addresses five challenges that may occur when implementing a reverse mentoring programme (Murphy 2012) as well as the organisational age theory (Chaudhuri & Gosh, 2012). The reason for including two different theories in the figure of challenges is because both of the theories have a strong connection with each other and will enable for a more thorough and valuable analysis.

Figure 2: Challenges with Reverse Mentorship

Further, the second theory (Figure 3) highlights the positive outcomes that the individuals and the organisation will acquire from a successful reverse mentoring programme. The bold lines represent the main model reflecting the outcomes addressed by Murphy (2012), while the dotted lines represent the outcomes that Clarke et al. (2019) further have added to Murphy’s (2012) positive outcomes. The reason for choosing to add Clarke et al. (2019) into the conceptual framework is because the three additional outcomes are relevant in today’s workforce and will provide more validity to Murphy’s (2012) key outcomes. The conceptual framework will provide a deeper insight into how a male-dominated organisation could implement a reverse mentoring programme in a fruitful manner. Thus, contribute to an in-depth analysis of the empirical findings to come to a conclusion and answer the research questions.

3. Methodology & Method

___________________________________________________________________________ Within this part of the thesis, the research methodology will be presented including the research philosophy, research approach, and finally, research strategy. Additionally, this chapter will present the method for the study including the data collection, the sampling procedure, and the interview guide. Conclusively, the data analysis and data quality will be outlined and discussed.

___________________________________________________________________________

3.1 Methodology

3.1.1 Research Philosophy

There are two main paradigms for the research philosophy: positivism and interpretivism. Firstly, it is imperative to consider whether the study is broadly positivist or interpretivist. This can be determined by considering the three philosophical assumptions that exist as a foundation of the two main paradigms: ontological, epistemological, and axiological. This study can be considered to be broadly interpretivism as the research process goes in line with a subjective social reality with multiple realities, insights are derived from subjective data from participants, and the authors are continually interacting with the research topic. Lastly, the authors recognise that the research is subjective and that the findings are biased and valued to the highest degree (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Furthermore, the research philosophy interpretivism will be applied as the aim of the study is to examine reverse mentorship through the participants’ perceptions, interactions, and connections to the topic. This will be done to gain rich findings and discover different perspectives of reverse mentorship connected to the problem formulation (Collis & Hussey, 2014; Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill, 2016).

3.1.2 Research Approach

When conducting a study, the research approach must be suitable for the purpose of the study. According to Collis and Hussey (2014), two of the commonly discussed research approaches are namely, inductive and deductive. The inductive approach refers to exploring the phenomenon through observations of the empirical reality, while the deductive approach examines the validity of the hypothesis derived from the theory (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

Nevertheless, there are limitations within these approaches where inductive reasoning restricts the author from developing theory-building, while deductive reasoning obstructs the process of selecting theory in line with the strict logic of testing the theory and altering hypotheses (Bell, Bryman, & Harley, 2019). To overcome the restraints within inductive and deductive reasoning, researchers can use the abductive research approach.

The abductive research approach refers to research where the authors examine recognised significant fundamental patterns of a selected phenomenon to understand the complex reality and develop synthetic reasoning of it (Ong, 2012). In other words, first, examine and find patterns, and then describe the observations and reveal deep structures (Mentere & Ketokivi, 2013; Saunders et al., 2016). This research paper will apply the abductive research approach as the study was initiated with several perspectives of reverse mentorship to further pursue the most suitable clarification of the observations. The interpretivist philosophy comprehends that the world is based on a social setting and accordingly complex to a great extent (Collis & Hussey, 2014), thus the interpretivist philosophy is considered appropriate to the abductive approach. Moreover, this research approach will grant the authors the ability to enhance the relevance of this papers frame of reference as it will operate as a channel between the field and the theory (Urdari & Tiron Tudor, 2014).

According to Ong (2012), the abductive research approach can be persecuted through several steps. For this study, the first step was to formulate the problem and present the purpose of discovering how diversity could be fostered through a reverse mentoring programme in a male-dominated organisation. Thereafter, the existing literature about the topic was examined to support the primary data collection. Further, the interview guide was established, followed by pilot interviews to increase the clarity of the interview guide. Based on the feedback, the question design was reviewed and refined. When further conducting the semi-structured interviews, new perspectives and themes appeared, which was later researched, analysed, and added to the frame of reference. By using the abductive approach, the authors were enabled to use the back-and-forth process to improve the frame of reference along with creating a harmonised bridge between the theory and the data. Lastly, the authors’ understanding of the empirical data were sent to the participants to ensure validity and genuineness towards them.

3.1.3 Research Strategy

This study will follow the qualitative method since it provides a better chance of obtaining new insights and accurate data to answer the research questions in a detailed and extensively manner (Saunders et al., 2016). Further, since this research paper desires to explore a rather new phenomenon, it aims at being an exploratory study (Saunders et al., 2016). The exploratory strategy strives to understand the phenomenon in-depth as well as comprehend the fundamental behaviour of humans (Bell et al., 2019), which will be derived from using the conceptual framework throughout the research process (Saunders et al., 2016; Yin, 2018).

According to Yin (2018), a study that aims to acknowledge the questions “how” and “why” when not depending on controlling behavioural events nor being historical but presently relevant, could benefit from applying a case study as the research strategy. This research paper has the purpose to examine “how” and “why” a male-dominated organisation could benefit from using reverse mentorship as a tool to foster diversity, and, therefore, this research paper fulfils the criteria of being a case study. Moreover, a case study approach enables in-depth comprehension of the phenomenon while leaving room for reflection as well as interpretations to a broader extent (Saunders et al., 2016).

However, as this study will be analysing different male-dominated organisations with different cases, the final strategy that will be conducted in this research will be a multiple case study (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007; Saunders et al., 2016; Yin, 2018). Compared to a single case-study, multiple case studies are beneficial since perspectives from multiple respondents generate a greater authentic theory which, in line, increases the trustworthiness of the result. Correspondingly, it allows for a more extensive investigation of the research questions and theoretical evolution (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007).

3.2 Method

3.2.1 Data Collection

The data collection of this research paper consists of two parts: secondary data and primary data. Secondary data refers to data accumulated from another source, while primary data refers to data that is originally conducted by the authors themselves (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

Secondary Data

The authors commenced the data collection process with searching for literature within reverse mentorship to gain an understanding of what the existing literature has examined about it. From the secondary data collection, the authors could establish a conceptual framework as a foundation for the study, to further proceed with the primary data collection.

Figure 4: Literature Search Specification of Secondary Data

Primary Data

Primary data was collected through semi-structured interviews with three male-dominated organisations, where each organisation was represented by three to four respondents. This type of collection method is commonly applied within qualitative research and allows the authors

mentorship, diversity, and the future of the company (Appendix 2 & 3). Nevertheless, they left space for additional follow-up questions which allowed the authors to modify the process along with the execution of the interview to gain as in-depth answers as possible (Saunders et al., 2016).

3.2.2 Population & Sampling

The sampling procedure was chosen in line with the research purpose and the research questions (Saunders et al., 2016). According to Saunders and Lewis (2012), the first step is to decide whether the sample should fall under a probability sample or a non-probability sample. To be referred to as a probability sample, all individuals in a population should have an equal chance of being selected, accordingly, the sample could be referred to as a statistical representation of the population. When the individuals do not have the same probability as others of being selected from the population, the sample is referred to as a non-probability sample (Saunders & Lewis, 2012). This study will apply a non-probability sample as this research desires specific organisations and respondents, namely that they should be representing a managerial perspective from a male-dominated organisation.

Within this research paper, the purposive sampling approach was applied which enabled the authors to select a small sample that could generate relevant empirical findings in regard to their research questions (Bell et al., 2019). Likewise, this procedure was applied since a small sample was studied and the results of the study could not be anticipated to be a statistical representation of the whole population (Saunders et al., 2016). Furthermore, as this study followed the qualitative approach with an interpretivism philosophy, a small sample were chosen as it would bring a more thorough understanding of the situation (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

Two criteria were established prior to the sampling procedure and were used when determining the chosen sample. First of all, the participants should be working in a male-dominated organisation, as these organisations tend to lack in diversity (Campuzano, 2019). The second criterion was that the participants should have a managerial position within the organisation, as this would bring a valuable managerial perspective. Further, the authors strived to include organisations from both perspectives: (1) organisations who have implemented a reverse mentoring programme, and (2) organisations who have not. This was sought since the authors

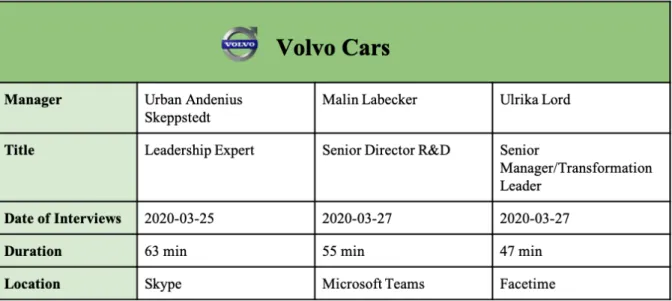

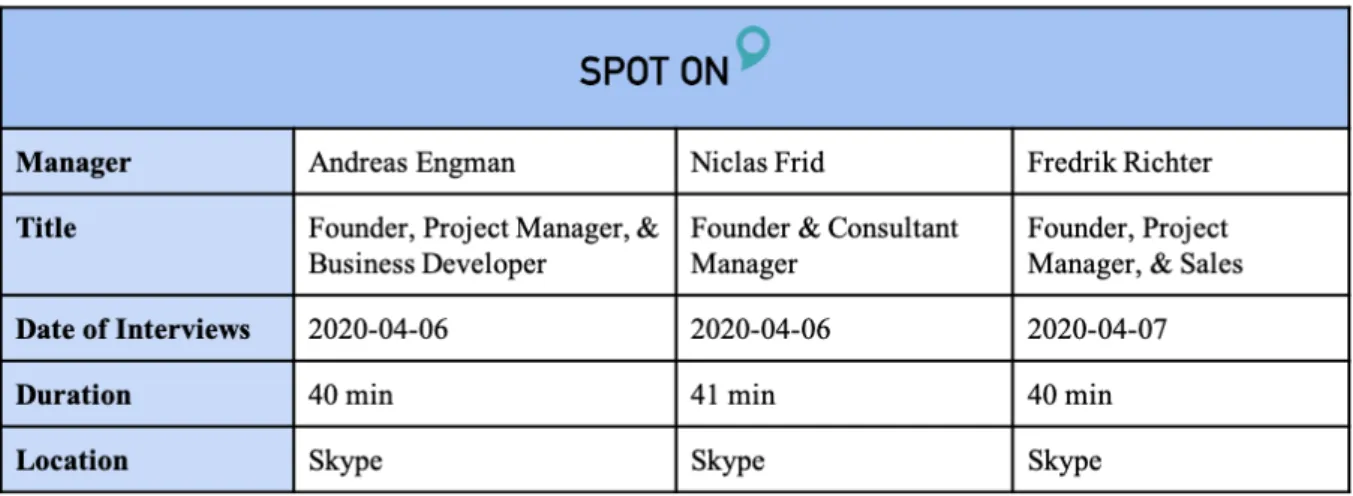

wanted to get a less biased perspective of how a successful reverse mentoring programme could be established. Lastly, the authors aimed for at least three representatives from each company to increase the trustworthiness and transferability of the data. The male-dominated organisations that were chosen for this study fulfilled the previously mentioned prerequisites and consisted of Volvo Cars, Volkswagen Group Sverige, and Spot On.

Volvo Cars

Volvo Cars is a global organisation with sales in over 100 countries and are considered to be one of the most recognised and respected premium car brands. The company was founded in Sweden and 1927 they launched their first car. Since then, they have grown to become a global company, developing innovative solutions for the future that will be all-electric, autonomous and connected (Volvo Cars, 2020). Volvo Cars is a male-dominated organisation with 24% female employees and 76% male employees, as expressed by the participants from the company. The organisation does not have a reverse mentoring programme implemented yet but do have a traditional mentoring programme within their graduate programme.

Volkswagen Group Sverige

Volkswagen Group Sverige is a subsidiary of Europe’s largest car manufacturer Volkswagen AG and is classified as Sweden’s largest car importer of the brands Volkswagen Personbilar (Passenger Cars), Audi, SEAT, SKODA, Porsche, and Volkswagen Transportbilar (Commercial Vehicles). They launched their first car in Sweden in 1948 and has, since then, become one of the most popular car brands in Sweden (Volkswagen Group Sverige AB, n.d.-a, n.d.-b). Volkswagen Group Sverige is a male-dominated automotive organisation consisting of 33 % female employees and 67% male employees in 2020, as expressed by Jeanna Tällberg who is the HR Director of the company. The organisation has a reverse mentoring programme since 2017 and the respondents from Volkswagen Group Sverige are, therefore, representing a perspective based on their experiences from the programme.

Spot On

Spot On is a Swedish IT company working with e-commerce, web- and system development. The company was founded in 2011 in Jönköping by Andreas Engman, Niclas Frid, and Fredrik Richter. Today, the company has offices in Jönköping, Göteborg, and Stockholm with 33 employees in total (Spot On, 2020). Spot On is a male-dominated organisation consisting of 34 % female employees and 66 % male employees, as expressed by the founders of the company. The organisation does not have any reverse mentoring programme implemented, nor a traditional mentoring programme.

3.2.3 Question Design

Within the interpretivism paradigm, it is valuable to use semi-structured interviews as it allows the researchers to conduct interviews with the purpose of collecting data that reflects the respondents’ understandings, opinions, attitudes, and feelings (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The questions prepared prior to the interview was made to encourage the respondent to speak about the major topics of interest and during the interview, the researchers developed additional questions (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Further, to bestow the researchers with a sense of guidance during the interviews, the questions were designed in regard to the conceptual framework. Within semi-structured interviews, there are three categories of questions to be used, namely: (1) open, (2) probing, and (3) specific and closed questions (Saunders et al., 2016). Open questions call for a longer, descriptive answer compared to closed questions which only requires a simple “yes” or “no”. The semi-structured questions were divided upon the mentioned categories. Firstly, the respondents were to answer pre-interview questions (Appendix 1), which were mostly specific or reclosed questions to get to know the respondents and their professional career. Continually, the in-depth questions were asked from the three themes in the interview guide: reverse mentorship, diversity, and the future of the company. This was done to receive more extensive answers to develop an understanding of the respondents’ opinions and perspectives. Lastly, probing questions were used as follow-up questions and to clarify answers where needed.

Interview Guide

Based on the developed question design, an interview guide was generated to allow the authors to deliver consistent interviews. Based on the purpose of the study, two different types of interview guides were created: one focusing on interview questions for an organisation that have implemented a reverse mentoring programme (Appendix 2), and the other focusing on questions for an organisation that have not (Appendix 3). This was established as the two different types of organisations required different types of questions to get a greater understanding of their perspective. However, the questions were, likewise, focusing on the three themes reverse mentorship, diversity, and the future of the company. Lastly, the authors created an English version and a Swedish version of the interview guides since all of the interviews were held in Swedish. Considering that all respondents were native Swedish speakers, the researchers decided to conduct the interviews in Swedish as that would considerably generate more in-depth answers from the interviewees along with making them more comfortable to share and formulate their opinions.

3.2.4 Test Interviews & Question Formulation

When the question design and interview guides had been established, the authors conducted test interviews with two individuals who had no connection to the chosen male-dominated organisations that were to be interviewed. With the question design and the interview guide, the authors tested the questions to practice interviewing as well as gaining feedback from the test respondents. The feedback was both in terms of clarity and reasonably of the questions, as well as in terms of the planned length of the interview. The feedback and suggestions from the test interviews were not only imperative to formulate questions of high quality, but also in terms of valuable insights regarding how to execute a professional and efficient interview.

3.2.5 The Interviews

Ten semi-structured interviews were conducted, and the initial goal was that all interviews were to be held face-to-face to observe body language, reactions, and other physical indications that could be valuable for the study. However, due to the prevailing circumstances and the consequences of Covid-19 that took place during the process of this study, the interviews

their three participants from the study, which decreased the number of participating organisations from four to three. Each interview was audio-recorded to make the transcribing of the interviews more valid and accurate. To further ensure confidentiality, the researchers informed the respondents about the publication of the thesis on a digital publishing archive and were, thereafter, asked if they wanted to be anonymous or not in this study. All respondents answered that they did not want to be anonymous.

The interviews were conducted in Swedish to get as rich data as possible from the respondents and to eliminate any insecurities the respondent might have about the level of knowledge and vocabulary in English. Therefore, it was imperative that the authors translated the answers mindfully and considered potential differences in phraseology between the languages. Lastly, all respondents were given the opportunity to take part of the translated answers prior to the authors using it in the report to make the respondents approve the translation and use of their opinion.

Volvo Cars

Volvo Cars were represented by three participants with managerial roles from different departments. The respondents expressed their own opinions and perspectives and did not necessarily represent the whole organisation’s perspective.

Volkswagen Group Sverige

From Volkswagen Group Sverige, all of the respondents had a connection to the organisation’s reverse mentoring programme. Charlotte Haggren and Miyako Soeda Thornton had been mentors in the programme, while Jeanna Tällberg had been a protégé. Hanna Holmlund, on the other hand, had not participated in a reverse mentoring relation yet, but could still contribute with valuable insights on how it has affected their organisation. Miyako Soeda Thornton is no longer working at Volkswagen Group Sverige but represents her experience as a former mentor in their programme. Lastly, the respondents expressed their own opinions and perspectives and did not necessarily represent the whole organisation’s perspective.

Spot On

Spot On was represented by the three founders of the company, who expressed their own opinions and perspectives in the interviews, but also their organisational perspective since they are the founders.

3.2.6 Data Analysis

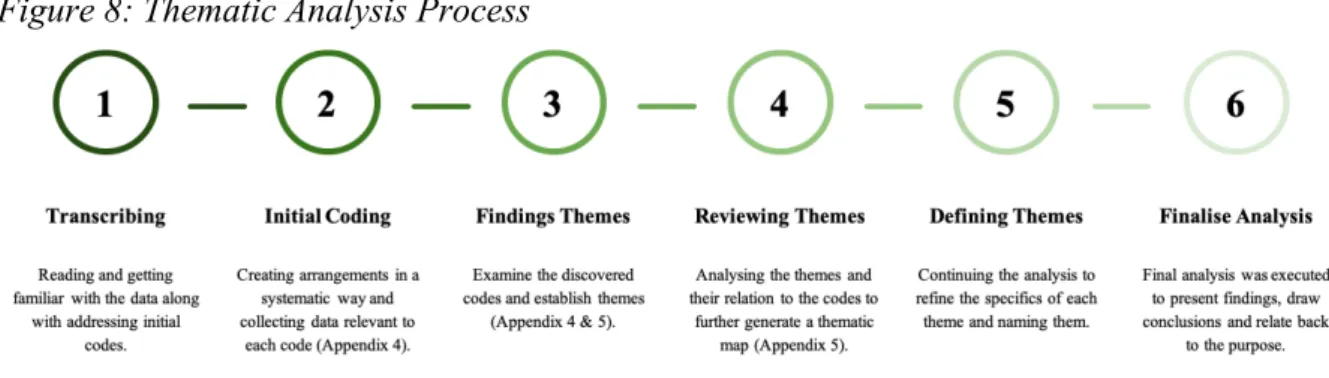

In this study, the data was analysed by using the thematic analysis which is an appropriate approach within qualitative research. To identify and analyse common themes and patterns from the data, the authors followed a continuous process recommended by Miles and Huberman (1994). Further, the themes derived from the empirical findings were connected to the conceptual framework.

The thematic analysis process consisted of six steps (Miles & Huberman, 1994), where the first step was concerned with transcribing the interview material. The authors did not transcribe unnecessary things such as pauses and repetitions to make the answers more seamless and clearer. Thereafter, the answers were translated into English and sent to the respondents to get their approval to cite them accordingly. Moreover, the authors investigated the transcript to get acquainted with the material. The second step in the process was to initiate the coding process (Appendix 4), which included creating arrangements in a systematic way that would allow for potential codes to be included. The third step was to examine the discovered codes to establish common themes (Appendix 4 & 5). The fourth step concerned analysing the discovered themes and deciding whether to consolidate or separate them. In the fifth step, the final themes were given a representative title and were further explained. Lastly, the final analysis of the collected data was bestowed consistently and reasonably (Miles & Huberman, 1994).

3.2.7 Data Quality

This part will present the credibility, transferability, dependability, confirmability, as well as the ethical considerations of this research paper.

Credibility

Credibility is an imperative factor to consider when conducting research and is concerned with whether the research has been completed in a way that the topic of the study is correctly identified and described (Collis & Hussey, 2014). To deliver high quality within each section of the research process, the authors have been required to gain a thorough level of knowledge about the topic of the study. Furthermore, the authors have worked closely together through the whole process and have continuously executed peer debriefing between each other’s work (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Lastly, the authors have applied triangulation within the collection of the data, meaning that they have collected data from multiple different sources to gain a broader perspective of the phenomenon reverse mentorship (Collis & Hussey, 2014; Patton, 1999). Transferability

Transferability refers to whether or not the study can be applied to similar situations, also referred to as generalisation (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Within this study, as mentioned in 3.2.2 Population and Sampling, the utilisation of qualitative methods, an interpretivism philosophy, small samples, and a purposive sampling technique may create obstacles in terms of the findings not being statistically representative of the wider population (Saunders et al., 2016). Nonetheless, it is relevant to thoroughly describe each step of the research process so that future researchers can follow these when examining the topic in another setting (Saunders et al., 2016), which has been executed in this paper. Regardless of the level of transferability within this research paper, this study contributes with observations, insights, and a potential tool of how to foster diversity within male-dominated organisations.

Dependability

Whether the research process of this paper is systematic, accurate, and well-documented are factors that determine the dependability of the study (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Within a qualitative study, it is imperative to describe the research process in detail so that future researchers could follow the same structure and obtain similar results (Shenton, 2004). Multiple measures were taken to increase the dependability, for instance, both authors were involved in the data collection process, the interview questions were divided into two parts, and they were

asked by the same person to ensure consistency and reduce bias. Furthermore, each interview was recorded and uploaded on a shared cloud so that no data was lost or destroyed. Thereafter, the interviews were transcribed by one author, and, thereafter, reviewed and accepted by the other author to reduce biases. As this research applies the data collection method of semi-structured interviews, the dependability may be questioned since interviews display the matter of a specific time. Nevertheless, as the chapter about the applied method for this thesis is rigorously described in detail, this research paper could be considered as dependable (Saunders et al., 2016).

Confirmability

Confirmability relates to whether the research process is fully described and concerns the authors’ capabilities to remain objective throughout the research process (Collis & Hussey, 2014; Shenton, 2004). There is a risk of the human factor influencing this thesis, as both of the authors have strong personal beliefs in diversity. Nevertheless, since the authors had very limited knowledge about reverse mentorship prior to the thesis, they have been very strict with not allowing their own opinions influencing their work. To further increase the confirmability of the thesis, the authors explained the whole research process in detail with a clear methodology and method. Along with that, confirmability was ensured by audio-recording each interview and reviewing each answer in detail.

Ethical Consideration

It is of great importance to consider the ethical aspects when conducting research (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Firstly, the participation was voluntary, and the participants could withdraw at any time. Moreover, the respondents were given the opportunity to read through the data interpretation conducted by the researchers so that they could confirm, validate, and feel assured that their statements and the translations were in line with their perception of the interview.