Malmö högskola

Lärarutbildningen

Idrottsvetenskap

Examensarbete

15 HögskolepoängCareer transitions for Swedish golf

juniors – from junior to senior sport

Daniel Jorlén

Lärarexamen 270hp Examinator: Bo Carlsson Idrott och fysisk bildning

Abstract

Since the transition from junior to senior level within sport has been shown to be a crucial step, where many athletes fail, it is important to get more knowledge about this process. The objective of this study was to prospectively investigate perceived demands and barriers for golf juniors in their transition from junior to senior level, with college golf in USA. The purpose was also to find out what resources and coping strategies the juniors planned to use in order to succeed with the transition. The developmental model (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004), The analytical career model (Stambulova, 1994) and

The athletic career transitions model (Stambulova, 1997; 2003) were used as a

theoretical framework. The study was conducted through interviews with nine junior golf players at the age of 18 to 20 years. A semi-structured interview guide was used consisting of two main themes: Expected general life changes/challenges and expected changes/challenges within golf. Prior research has revealed five dimensions of stress during the transition to senior sport: interpersonal relationships, being away from home, academics, high performance expectations and training intensity. All of these factors were mention by the golf juniors as possible barriers during the transition. The result showed that the participants didn’t predict any drastic changes in their everyday life and didn’t expect any major problems in their relationships to family and friends.

Homesickness was mentioned by almost all of the players though as one of the biggest changes/challenges connected to the everyday life. The players also expected it to be difficult and hard to study at college in USA. Many stated that they would spend more time and focus on school, but at the same time, said that they would prioritize golf before school. Their main reason for going to USA was to succeed at golf, not to study. Harder climate and bigger rivalry among team players and on competitions were something that all of the players predicted. They also expected the college coaches to have a different leadership style and expressed concerns about the college coaches’ golf knowledge. Many of the players stated that they would continue to have a lot of contact with their old trainer in Sweden. The golf juniors reported of good external support from different persons with knowledge about golf college as well as from family and friends. The negative aspect of this support is that many of them are located in Sweden, far away from where the players will live. The golf juniors also mentioned internal resources such as different golf skills and personal characteristics, e.g., being social, positive, creative and goal-orientated as things that would be important for them during the transition. Many of the participants reported about goals and strategies concerning their golf play, but only a few of them mentioned preparations regarding their everyday life.

Sammanfattning

Eftersom övergången från junior till senior inom sport har visat sig vara ett kritiskt steg, där många idrottare misslyckas, är det viktigt att öka kunskapen kring denna process. Syftet med denna studie var att, i ett framåtblickande perspektiv, undersöka vilka krav och barriärer golfjuniorer upplever under övergången till seniornivå med spel på golfcollege i USA. Syftet var också att studera vilka resurser och copingstrategier som juniorerna planerade att använda för att lyckas med övergången. Utvecklingsperspektiv

på idrottskarriärens övergångar (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004), Den analytiska karriärmodellen (Stambulova, 1994) och Modellen över idrottskarriärens övergångar

(Stambulova, 1997; 2003) användes som teoretiskt ramverk. Studien utfördes genom intervjuer med nio golfspelare i åldern 18-20 år. Under intervjuerna användes en semistrukturerad intervjuguide bestående av två huvudteman; förväntade generella förändringar/utmaningar i vardagslivet och förväntade förändringar/utmaningar inom golfen. Tidigare forskning har visat på fem olika dimensioner av stress förknippat med övergången till seniornivå: personliga relationer, att vara iväg hemifrån, akademiska krav, höga prestationsförväntningar och hög träningsintensitet. Alla dessa faktorer nämndes av golfjuniorerna som möjliga barriärer under övergången. Resultatet av studien visade att deltagarna inte förutsåg några drastiska förändringar i sitt vardagsliv eller större problem i sina relationer med familj och vänner. Hemlängtan nämndes dock av nästan alla spelare som den största utmaningen när det gällde vardagslivet. Spelarna trodde även att det skulle bli svårt att studera på college i USA. Många av dem uppgav att de skulle spendera mer tid på skolarbete, men sa samtidigt att de prioriterade golfen framför skolan. Den största anledningen till att åka till USA var att lyckas med golfen, inte att studera. Tuffare klimat och ökad rivalitet inom laget och på tävlingar var något som alla spelarna förväntade. De trodde också att collegetränaren skulle ha en annan ledarskapsstil och uttryckte en oro över ledarnas golfkunskaper. Många av spelarna uppgav att de skulle fortsätta att ha mycket kontakt med sina tidigare tränare i Sverige. Golfjuniorerna uppgav att de hade bra externt stöd från olika personer med kunskaper kring golfcollege, liksom från familj och vänner. Den negativa sidan av detta stöd är dock att många av dem finns i Sverige, på långt avstånd från spelarnas nya hemort. Golfjuniorerna nämnde också interna resurser, såsom sina golfkunskaper och personliga egenskaper, t.ex. att de var sociala, positiva, kreativa och målinriktade, som viktiga faktorer för att lyckas med övergången. Många av spelarna berättade om mål och

strategier kopplade till golfen, men få av dem nämnde några förberedelser när det gällde det vardagliga livet.

Table of Contents

Preface

1. Introduction... 7

2. Key concepts... 8

2.1 Athletic career... 8

2.2 Career transitions in sport...8

3. Models of career transitions... 9

3.1 Career stage descriptive models...9

3.1.1 The developmental model... 9

3.1.2 The analytical career model...12

3.2 Career transition explanatory models...12

3.2.1 The athletic career transitions model...12

4. Research results on Career transitions... 14

4.1 The transition from junior to senior level according to the analytical career model... 15

4.2 Perceived challenges and demands during the athletes’ first college year...17

4.3 Dimensions of stress...19

4.4 Coping resources used by the athletes during their transition to college sport... 19

4.4.1 Coaches’ role in the career transition...19

4.4.2 Parents’ role in the career transition... 20

4.4.3 Social support... 21

4.5 Educational and vocational consequences of athletic participation... 22

5. Objective...24 6. Method... 24 6.1 Participants... 24 6.2 Instrument... 24 6.3 Procedure... 25 6.4 Data analyses... 25 7. Result...26

7.1 Changes/challenges in everyday life that the players expect to occur in their transition from junior to senior level in golf... 26

7.1.1 General expectations on the move to USA and how it will affect the everyday life... 26

7.1.2 Expected changes/challenges in relations with family and friends... 28

7.1.3 Expected changes/challenges in school, responsibility for their own

household and in time for leisure... 30

7.1.4 Expected changes/challenges in culture and language...32

7.2 Changes/challenges related to golf that the players expect to occur in their transition from junior to senior level in golf... 34

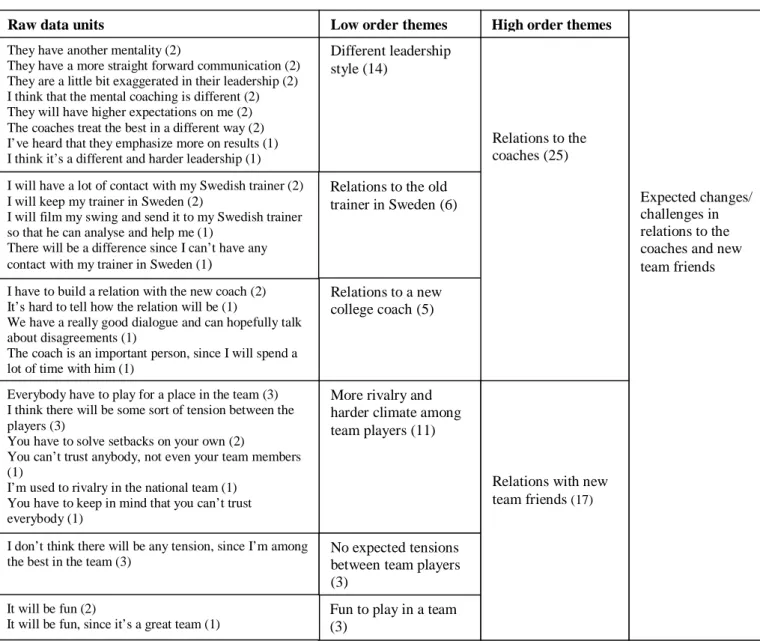

7.2.1 Expected changes/challenges in relations to the coaches and new team friends...34

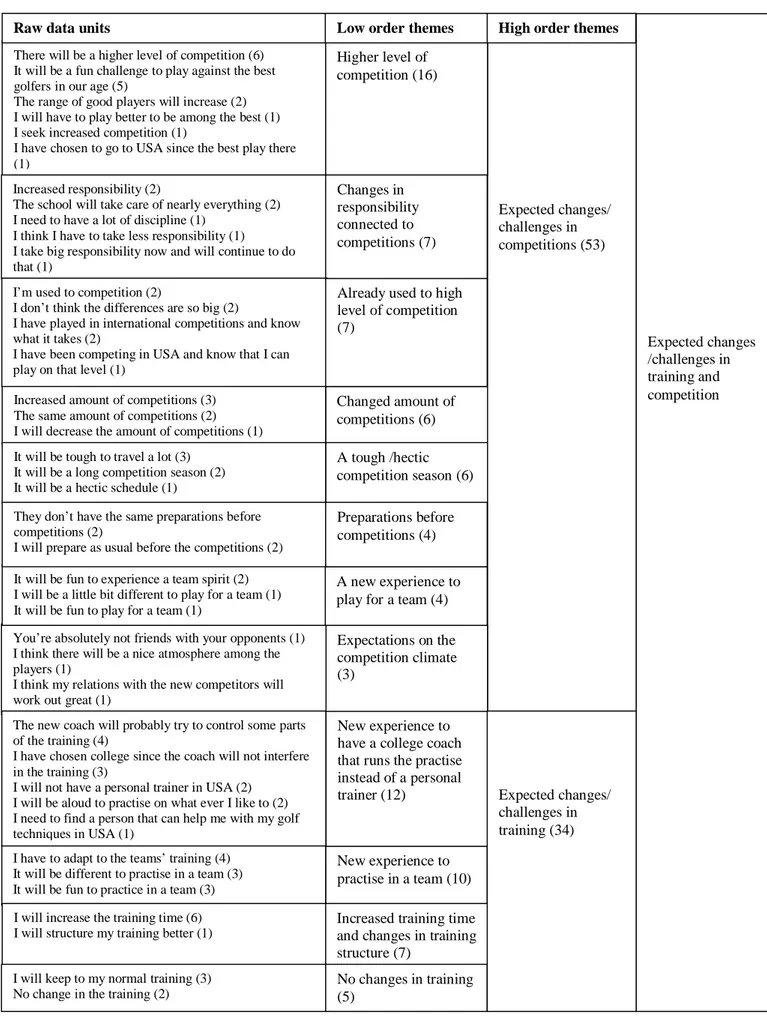

7.2.2 Expected changes/challenges in training and competition... 36

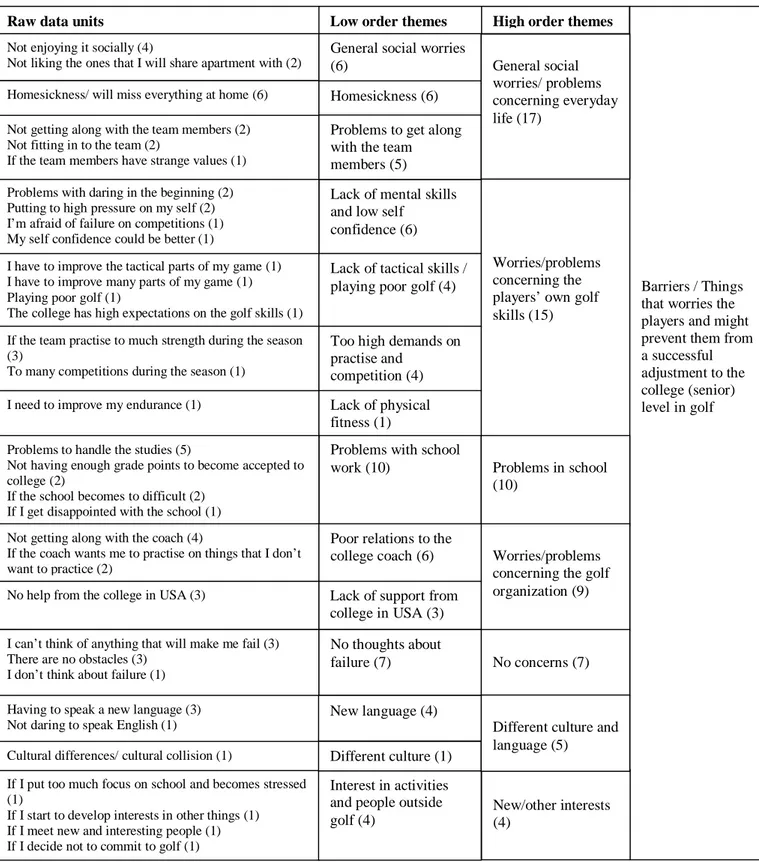

7.3 Barriers/ Things that worries the players and might prevent them from a successful adjustment to the college (senior) level in golf... 38

7.4 Resources that the players think will help them to handle the transition... 41

7.4.1 External resources that the players think will help them to handle the transition.... 41

7.4.2 Internal resources that the players think will help them to handle the transition... 44

7.5 Preparations /strategies and goals that the players think they will use in order to succeed with the transition... 47

8. Discussion... 51

8.1 Changes/challenges in everyday life that the players expect to occur in their transition from junior to senior level in golf... 51

8.2 Changes/challenges related to golf that the players expect to occur in their transition from junior to senior level in golf... 53

8.3 Barriers/Things that worries the players and might prevent them from a successful adjustment to the college (senior) level in golf...54

8.4 Resources that the players think will help them to handle the transition...56

8.4.1.External resources that the players think will help them to handle the transition...56

8.4.2 Internal resources that the players think will help them to handle the transition...58

8.5 Preparations /strategies that the players think they will use in order to succeed with the transition... 60

8.6 Limitations... 61

8.7 Future research... 62

References ... 64

Preface

This study is a follow-up on an earlier essay that I wrote during the autumn term, 2007 at School of Social and Health Sciences, Halmstad University. The first study covered young golfers’ transition from regional to national junior elite competitions. The same golf juniors that have participated in this study were then interviewed retrospectively about the transition that they already had made and succeeded with.

This study has been a continuation and development of the first essay and has covered the next career transition that the golfers now will face; the transition from junior to senior level with golf college in USA. The study has been conducted prospectively, where the golfers instead have been asked to talk about their expectations on the upcoming transition.

Since both these studies are based on the same theories about career transitions the same background information about the theories has been use in both essays. The text on page 8-16 in this essay is a repetition from the first essay. Some repetition can also occur in other parts of the essay since it’s a follow up on the former study with the same participants and theoretical background.

1. Introduction

Sweden has many golf players, both male and female, that are successful and belong to the world’s golf elite. But now, when the Swedish crown jewel within golf, Annika Sörenstam, has ended her career, it might be a good time for Swedish golf to ask questions about what the future looks like and how Swedish golf should continue to produce good golf players and harvest international successes in the future.

A natural step for many promising golfers in their development from junior to senior is to study at Golf College in USA. The transition from junior to senior level within sport has been shown to be a critical step within an athlete’s career though, and many athletes fail to handle this transition successfully. The athletes can be divided into two groups. The biggest group stagnates in their development, quits their sport or continues on an exercise level. The small group that succeeds with the transition from junior to senior has the possibility to continue to elite sport on a senior level. Auweele, Martelaer, Rzewnicki, Knop and Wylleman’s studies of Belgian track and field athletes from 2004 showed that as few as 17% of junior elite athletes can handle the transition to compete successfully on a senior level, 31% stagnate in their development, 28% perform irregularly and 24% drop out. The majority of promising juniors doesn’t succeed to reach the goals that are expected of them (Vanden, Auweele, De Martelaer, Rzewnicki, De Knop & Wylleman, 2004). The probability for a college athlete to progress into professional sport after this stage has also been shown to be very low; somewhat less than 2% (Kennedy & Dimick, 1987).

It is important to investigate why talented juniors often fail in their transition from junior to senior, and why many of them feel lost in the senior sport. Paradoxically it is often the most promising young athletes, with the fastest development in junior age, and the ones that have gained early social recognition, that are experiencing this period as especially difficult (Stambulova, in press).

Bearing in mind that Sweden is a relatively small golf nation and that only 17% of the junior elite can handle the transition to perform at senior sport (Vanden Auweele, De Martelaer, Rzewnicki, De Knop & Wylleman, 2004), it becomes obvious that it is important to give as many juniors as possible the chance to make a successful transition.

The objective of this study is to investigate perceived demands and barriers for golf juniors in their transition from junior to senior level, and to find out what resources and coping strategies the juniors think they will use in order to succeed. With a greater understanding about this process a larger share of juniors could hopefully succeed in their transition and in that way increase the chances for Swedish golf to bring up new stars.

2. Key concepts

2.1 Athletic career

In Alfermann & Stambulova (2007) the athletic career is defined in two ways. The first definition is “a term for the multiyear competitive sport involvement of the individual aimed at achieving his/her individual peak in athletic performance in one or several sport events” the second definition is “succession of stages and transitions that includes the athlete’s initiation into and continued participation in organized competitive sport and that is terminated by the athlete’s voluntary or involuntary discontinuation of participation in organized competitive sport.” (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004).

2.2 Career transitions in sport

A transition can be defined as “an event or non-event which results in a change in assumption about oneself and the world and thus requires a corresponding change in one’s behaviour and relationship” (Schlossberg, 1981 p. 5). A contemporary definition is that the career transitions in sport come with different demands related to practice, competition, communication and lifestyle. If the athletes want to have a successful sport career they have to cope with the new demands (Alfermann & Stambulova, 2007).

There are two types of transitions: normative and non normative transitions. The normative transition is generally predictable and anticipated. When a normative transition happens, an athlete leaves one stage and enters another stage. In the athletic domain normative transitions can include the beginning of sport specialization, the transition from junior to senior, from regional to national level of competitions and from amateur to professional status. Opposite to normative transitions non normative

transitions are hard to predict and often come involuntary (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004). They do not occur in a set plan or schedule. The non normative transitions are situation-related and specific for the individual (Alfermann & Stambulova, 2007). For athletes these transitions may include injuries, overtraining, the loss of a personal coach or changing a team. These transitions also include events that are expected or hoped for, but did not occur – labelled non-events. Examples of non-events are not being able to participate in major tournaments, or not being selected to the national team after years of preparation (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004).

3. Models of career transitions

Many of the theories and models that have been used to describe the athletic career have been taken from the mainstream psychological literature and been developed and

revised following research conducted in the area (Wylleman & Theeboom, 2004). The two major theoretical frameworks in sport career transition are athletic career stage descriptive models and career transition explanatory models.

3.1 Career stage descriptive models

The athletic career descriptive models try to predict what normative transitions athletes might experience. Athletic career descriptive models usually describe the athletic career as a “miniature life span course” and divide the athletic career into several stages and describe the changes in athletes and in their social environment across the stages

(Alfermann & Stambulova, 2007). The stages consist of the preparation/sampling stage, the initiation stage, the development/specialization stage, the

perfection/mastery/investment stage and the discontinuation of competitive sport involvement stage. The models don’t explain the transition processes, but they describe and predict the existence and order of the athletes’ normative career transitions

(Stambulova, in press).

3.1.1 The developmental model

(Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004)The strong links between the transitions in an athletic career and the transitions occurring in other domains of the athletes’ lives, such as individual, psychosocial and

academic/vocational levels, are reflected in the developmental model. The

developmental model uses a “whole person” and a “whole career” approach in order to help us see the athletes’ demands and transitions outside the sport as well as the athletes in a sport context. These transitions will usually occur in a simultaneous and interacting way. If the transitions in different spheres of life overlap, that can lead to difficult life situations for the athletes, so therefore it is really important to be able to predict such overlaps.

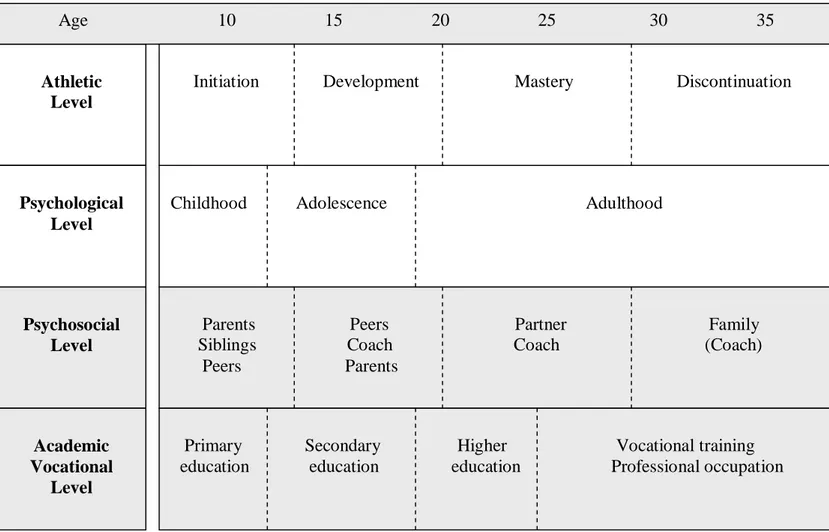

Figure 1 provides an overview of the normative transitions athletes will face at the athletic, individual, psychosocial, and academic/vocational levels, according to the developmental model (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004).

Figure 1. A developmental perspective on transitions faced by athletes at athletic,

individual, psychosocial, and academic/vocational levels (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004).

N

Note: A dotted line indicates that the age at which the transition occurs is an

approximation. Athletic Level Psychological Level Psychosocial Level Academic Vocational Level Age 10 15 20 25 30 35

Childhood Adolescence Adulthood

Parents Peers Partner Family Siblings Coach Coach (Coach) Peers Parents

Primary Secondary Higher Vocational training education education education Professional occupation

The top layer of this model reflects the athletes’ development in elite sport, but these stages can also be considered for athletes at a non elite level. The layer consists of four stages and transitions that the athletes face in their athletic development. The first stage is called the initiation stage and occurs when young athletes are introduced to organized sport and identified as talented athletes. The next stage, the development stage, occurs at the age of 12 or 13. The athletes then become more dedicated to their sport and start to specialize. They also increase the amount of training and competition. At the mastery stage, which occurs around the age of 18 to 19, the athletes have reached their highest level of athletic proficiency. When the athletes, at age 28 to 30, discontinue further participation in high-level competitive sport they have reached the discontinuation stage. It is important though to take into account that these age limits are averaged over many athletes and several different sports and therefore may not be seen as sport specific.

The second layer of the model reflects the athletes’ individual development of

normative stages and transitions occurring at the psychological level. It is divided into childhood, adolescence and adulthood (Lavallee, Kremer, Moran & Williams, 2004).

In the third layer the athletes’ psychosocial development is at focus. The layer concentrates on the development of relations to different groups and interpersonal relationships that are important to the athlete. Important persons and relations for the athletes can for example be parents, coaches, peers and spouses (Lavallee, Kremer, Moran & Williams, 2004).

The final layer contains the specific stages and transitions at the academic/vocational level. At the age of 6 or 7 years of age the transition into primary education/elementary school takes place. The transition to secondary education/high school takes part from the ages 12 to 13. At the age of 18 to 19 the transition into higher educating occurs. The last stage in this layer is the transition into vocational training/a professional occupation. This may occur at an earlier age but is here included after the higher education since this reflects the “normal” sports career in North-America, where college/university links to high school varsity and professional sport. The current development in Europe also implies that many athletes continue their education up to the level of higher education (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004).

The developmental model illustrates the concurrence of transitions occurring at different levels of development (e.g., the transition from primary education to secondary

education occurs at the approximate same time as the athletic transition from initiation to development) (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004).

3.1.2 The analytical career model

(Stambulova, 1994)The analytical career model predicts seven normative transitions in an elite sports career:

1. The beginning of sport specialization

2. The transition to more intensive training in chosen sport 3. The transition to high achievement sport

4. The transition from junior to senior sport

5. The transition from amateur sport to professional sport 6. The transition from peak to the end of sports career

7. Athletic career termination and transition to other professional career

3.2 Career transition explanatory models

The career transition explanatory models focus on reasons, demands, coping, outcomes and consequences of a transition. In all the career transition models, coping processes are seen as central in a transition and include all approaches the athletes use in order to adjust to the particular set of transition demands (Alfermann & Stambulova, 2007).

3.2.1 The athletic career transitions model

(Stambulova, 1997; 2003)Stambulova’s athletic career transition model follows the tradition to treat the career transition as a process and not as a single event. If the athlete should continue with a successful athletic career he or she has to cope with a set of specific demands

/challenges.

A set of transition demands creates a developmental conflict between “what the athlete is” and “what he or she wants or ought to be”. This stimulates the athletes to mobilize recourses and find ways to cope. How effective the athlete will cope with the transition depends on the balance between coping resources and barriers in the transition.

Resources and barriers can be of external and internal nature. The transition barriers include all internal and external factors that interfere with an effective coping e.g., lack of necessary knowledge or skills, interpersonal conflicts, lack of financial support and difficulties in combining sport and education or work, where transition resources include all internal and external factors that make the coping processes easier e.g., the athlete’s knowledge, skills, personality traits, motivation and financial support.

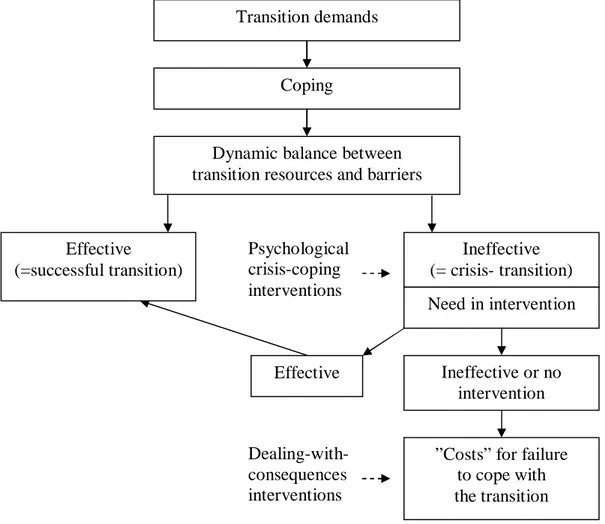

In figure 2 coping is shown as a key point, which divides the model into two parts. The upper part of the model considers the demands to cope with and the factors influencing coping, where the bottom part outlines two possible outcomes and consequences of a career transition.

Figure 2. The athletic career transition model (from Alfermann & Stambulova, 2007).

Transition demands

Dynamic balance between transition resources and barriers

Coping Effective (=successful transition) Ineffective (= crisis- transition) Need in intervention Ineffective or no intervention

”Costs” for failure to cope with the transition Effective Psychological crisis-coping interventions Dealing-with- consequences interventions

Successful transition and crisis-transition are the two outcomes of the coping process. Athletes that can mobilize their resources or develop necessary resources to cope with the demands in an effective way will have a positive transition. The athletes that can’t cope will have a crisis-transition. Reasons for ineffective coping can be low awareness of transition demands, lack of resources and/or persistency of barriers, and lack of ability to analyze the situation in order to make proper decisions. If the athlete receives psychological intervention he/she can change the ineffective coping strategies so they can have impact on the long term consequences of the transition. If the intervention is effective the athlete will make a positive, but delayed, transition. If the intervention is ineffective or the athlete doesn’t receive any qualified psychological assistance the athlete can face “costs” for the failure in coping with the transition. The possible costs include decline in sport results, overtraining, premature drop out from sport, different forms of rule violations, injuries, psycho-somatic illnesses, neuroses and degradation of personality e.g., alcohol and drug use or criminal behaviour.

During a career transition three kinds of interventions can be used. A crisis-prevention intervention is the first step that aims to prepare the athletes to cope with a transition and help them develop all necessary resources before or at the very beginning of each transition. Goal setting and planning, mental skills training and organization of social support systems are effective interventions at this stage of a transition that can help the athletes’ readiness for a normative sport career transition. When it is obvious that the athlete is in a crisis psychological crisis-coping interventions is needed. The

interventions strive to help the athletes to find the best available way to cope by analyzing the situation. When the athletes have experienced one or several negative consequences of not coping with a crisis transition psychotherapeutic or clinical intervention is often needed.

4. Research results on Career transitions

Research on transitions from one stage to another within sport is a relatively new interest and problem area for the sport psychologists. The amount of publications has increased from around 20 during the 1960-1970’s to more than 270 publications until today. The first studies that were conducted during the 1960’s and 1970’s emphasized

on the career termination among elite and professional athletes (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004; Stambulova, 2007). These studies tended to centre almost exclusively on the dysfunctional issues e.g., depression and alcoholism, that the athletes experienced. Since then the academic interest in the athletic career has clearly increased during the past two decades. Only a small part of the studies that have been conducted so far on career transitions have focused on the transition experiences, though. Most of the studies are still concerned with career termination and its consequences (Alfermann & Stambulova, 2007). But now, with an increased understanding of the career termination process, the sport psychologists have started to develop a more holistic view of the athletes, which takes in consideration the athletes’ life span perspectives by focusing not only on athletes’ development from beginning to end at an athletic level, but also on other domains of their life e.g., academic, psychosocial and professional (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004; Stambulova, 2007). Prospective research on the transition to college sport, which is the subject for this study, is still very rare though.

4.1 The transition from junior to senior level according to the

analytical career model

Stambulova’s study on Russian athletes from 1994 gave clear support to six out of the seven predicted transitions in the analytical career model (see page 12) because the third and the fourth ones were typically overlapped in real life. The normative transition step that is the most interesting for this study is the transition from junior to senior sport.

The transition from junior to senior sport plays the most critical role in the overall athletic career and marks the entry into the perfection/mastery/investment stage. Athletes frequently describe it as the most difficult career transition, and many of them had to acknowledge that they failed to cope with it (Stambulova, in press).

Table 1 provides an overview of the demands and coping recourses that occur in the transition from junior to senior sport according to the analytical career model.

Table 1. Demands and coping resources during the transition from junior to senior

sports (Stambulova, 1994; in press).

Perceived demands of transition Coping resources used during transition - To balance sport goals with other - Interest in scientific sport related life goals and to reorganize the lifestyle knowledge (physiology, psychology) - To search for one’s individual path in sport - Summarizing and drawing

- To cope with pressure of selection upon their own sport experience - To win prestige among peers, judges etc. - Implementation of psychological - To cope with possible relationship problems strategies in competition - Family and federation support

- Learning from mistakes of others

When the athletes enter this transition they realise that they need to set long term goals and make corresponding lifestyle changes if they want to succeed on senior level. Successful junior athletes often feel lost in senior competitions, even after they have made efforts and sacrifices, like putting their sport goals to the forefront at the expense of other spheres of life, such as family issues, communication with friends, work and studies. At this stage it’s important for the athletes to get noticed in the selection for the more prestigious competitions, and it also becomes a high priority to earn authority among opponents, team-mates and sport professionals. Many athletes try to solve this problem by refusing to imitate any model and start to search for an individual path or style that are built upon their own strengths, uniqueness and characteristics. A specific problem for junior athletes is that they often lack the energy for the most important competitions at the end of the season, because they have taken part in so many competitions. During this transition there is also an increased rivalry and competitiveness within the sport groups and teams as well as in the official

competitions, which can lead to relationship problems with coaches and team-mates and complaints about conflicts, misunderstandings and intrigues. The social support and admiration they were used to as juniors decrease. The different coping resources during this transition change from the transition to more intensive training in chosen sport. The role of social resources decline and the athletes instead relay heavily on their own competences and skills. This reflects their maturation not only as athletes but also as personalities. Research has shown that the most successful athletes manage to cope with this transition in 1-2 years of competitive seasons, but more often it takes 3-4 years (Stambulova, 1994; in press).

4.2 Perceived challenges and demands during the athletes’ first

college year

For many athlete students, starting college brings about a substantional psychosocial change and adjustment (Finch & Gould, 1996). Especially those in transition into or out of university can be at risk of developing adjustment disorders (Andersen, 2003). The demands placed on student-athletes, e.g., academic pressures, travels, sport performance and training demands, usually exceed the demands experienced by non-athlete students. Athlete students face a variety of developmental issues and have several special

pressures in addition to maintaining academic eligibility. (Andersen, 2002)

Researchers in the educational community have widely studied the adaptional processes of first-year, non-athlete students in college because over 25% of the first-year college students do not return for their second year (Giaccobbi, Lynn, Wetherington, Jenkins, Bodendorf & Langley, 2004). Ortez (1997) noted that there is a lack of research

focusing on the stress and coping processes that athlete students experience during their first university year though. For first-year university athletes the challenges associated with being in a new environment, adjusting to new training regimes and balancing school and academic demands makes this developmental period particularly difficult. Tracy and Corlett’s (1995) study on first-year university track and field athletes showed that the athletes felt both mentally and physically overwhelmed by the transition and experienced isolation and loneliness. The need to balance freedom and responsibility were seen as difficult challenges (Giaccobbi, Lynn, Wetherington, Jenkins, Bodendorf & Langley, 2004).

The life of athlete students is often a series of attempts to get catch up. An athlete student who is well ahead in his/her studies is rare. The pressure and demands for both academic and sport performances put significant burdens on their shoulders and often leave little spare time for the athletes to engage in common student activities and socializing, which could become very stressful (Andersen, 2002, Giaccobbi, Lynn, Wetherington, Jenkins, Bodendorf & Langley, 2004, Skinner, 2004) The fifteen participants in Skinner’s (2004) study were all concerned about time management in some form. This result correlates with the literature regarding balance in the lives of a freshmen student-athlete. Freshmen athlete students cannot devote much time to outside

activities after their daily studies and athletic obligations have been fulfilled (Skinner, 2004).

NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Association) Division I athletic programs are usually the largest and best funded college sport programs. Many of the athlete students receive full or partial scholarships. These sport programs often have regional, or even national, visibility, which means that athletes in these programs face a great deal of publicity. Some of the issues that athlete students bring to the sport psychologists include worries about maintaining their scholarships, expectations for success from athletic directors, parents and fans, pressure from coaches, and exposure in the media. Division I schools are often “pressure cookers” for the athletes, especially in the

revenue sports of football, basketball and baseball. One explanation to this could be that

the coaches’ livelihood is dependent on how well the athletes perform on the playing field. The athlete students know that in order to retain their scholarship or starting position, they need to work hard every day and remain in the coach’s favour. The combination of time commitments and stress related to athletic performance can take its toll on student athletes before they even open a book. Many schools also specialize in non-revenue sports, and pressures on athletes in those sports can also be substantial (Andersen, 2002, Skinner, 2004).

The athletes´ identities may also get deranged when they go from being a star player on the high school team to being just another member of the team in college. Learning such lesson may be particularly difficult for athletes who have moved away from their homes for the first time and are in new environments. The move to college can also be a

cultural transition. A foreign environment is something that can make the self-concept and identity suffer. Even some American athletes can feel like strangers in a different country when they make the transition to college. The pain and confusion that might come with a failure of meeting the new challenges for intimacy and identity can lead to a chronic use and abuse of alcohol and drugs in a self-medication purpose (Andersen, 2002).

4.3 Dimensions of stress

The pressure to perform athletically and in school often place athlete students under a great stress. Giaccobbi, Lynn, Wetherington, Jenkins, Bodendorf & Langley’s (2004) study explored the sources of stress and coping strategies of five female first-year university swimmers. The result revealed five dimensions of stress: interpersonal relationships, high performance expectations, training intensity, being away from home and academics.

Sources of stress related to interpersonal relationships often resulted from relationships with the coaches, people outside the sport and team-mates. High performance

expectations consisted of stress sources related to perceived expectations, pressure to perform, not performing as expected, being unable to contribute to the team and training while injured. Stress was also experienced as a result of being away from home and/or missing family and friends. Academic sources of stress were related to making the transition to university academic demands and balancing school with athletics (Giaccobbi, Lynn, Wetherington, Jenkins, Bodendorf & Langley, 2004). One major problem athlete students face involves missing classes and tests because of travels and competition commitments. Since academic performance is the students’ own

responsibility making up for missed classes and tests is part of being a student athlete. This can lead to test anxiety (Andersen, 2002).

4.4 Coping resources used by the athletes during their transition

to college sport

Nearly all students must handle forms of stress directly related to a new environment. It would be almost impossible not to feel the pressures of academic and social adjustment. Furthermore, athlete students face these problems along with high expectations of performance and many freshmen athlete students find themselves faced with difficult decisions with no one to turn to for advice (Skinner, 2004).

4.4.1 Coaches’ role in the career transition

Many athlete students select their school because of an athletic scholarship or a

traditional students, student athletes often pick the school for its athletic team first and academic program second. Some universities recruit students who are academically equipped, but most often coaches search for the most talented athletes in an effort to build strong teams. Not only are many student athletes poorly equipped for college academics, they also find that significant time is committed to athletics once they arrive on campus. Research has established a need for coaches to be more involved and work closely with the athlete students’ transition into college. They need to take a greater responsibility for the athletes’ total transitions, including school, since that could make the transition for student athletes smoother (Andersen, 2002).

4.4.2 Parents’ role in the career transitions

Conducted research has shown that the athletes’ parents play a major role in the athletes’ transition from one stage to another. Without a strong parental support during the earlier stages of sport participation a talented child is unlikely to fulfil her/his potential (Wolfenden & Holt, 2005). Bennie and O´Conner’s (2004) investigation of track and field athletes showed that the main facilitating factor on a successful transition was a supportive environment regarding the psychological, social and economic

situation. This is also highlighted in Carlsson’s study (1988) where the participating tennis players experienced their parents’ support differently. The players that developed into world class tennis players remembered their parents support in a more favourable way, with less pressure and demand for success than the players that didn’t succeed in the same way. This contributed to a more harmonious state of mind. The players that didn’t make a successful transition to the senior level reported of a greater demand for success from their parents (Carlsson, 1998).

Würt’s study (2001) that was conducted over a two year period with athletes averaging between 8 and 21 years of age also came to approximately the same conclusions concerning parental support. The athletes that perceived that they had a successful transition from one stage to another stated that their parents provided more sport related advice and emotional support than athletes that did not succeed in their transition. Lack of support from parents and coaches was the second biggest reason for dropping out of sport. The result of these studies supports the theory that parents and coaches are extremely influential in shaping the emotional responses of young athletes in their sport

involvement (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004). Similar results have also been found in Wylleman, De Knop and Van Kerckhoven’s study (2000) where they saw that the successful swimmers perceived their parents’ emotional support during their childhood sport participation in a positive way. The parents were underlining the need for

discipline and motivation in order to enhance athletic achievements (Wylleman & Lavallee 2004).

In Wolfenden and Holt’s study (2005) the result showed that parents were responsible mainly for social support and pressure, while the coach was responsible for teaching expertise and commitment to the sport. Another study showed that the athletes that had made a successful or qualified transition from junior to senior better could cope with stress and felt more supported by their parents in contrast to underachievers and dropouts. At the initiation and development stages the athletes are dependent on their families also due to financial reasons (e.g., hiring a top-level coach, buying sport equipment and travel costs) to promote their athletic career. (Auweele, Martelare, Rzewnicki & Wylleman, 2004).

When the athletes make the transition into high-level competitive sports the parents have an important role in providing the athletes with the possibility to take refuge from the sometimes excessive pressure of high level competitions (a support that is

independent of their childrens’ athletic achievements) (Wylleman, De Knop, Ewing & Cumming, 2000).

Also in the transition to higher education the parents play a major role. The parents “gently” pressure their children into continued formal education, on the way to a professional future. Therefore the parents can be a part of the transition stress that the athletes might feel, even if the parents are supportive and involved during the transition (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004).

4.4.3 Social support

The availability of social support and social support networks have been shown to have a strong influence on the athletes´ adjustment during athletic transitions (Wylleman, De Knop, Ewing & Cumming, 2000). To be closely associated with a group has proven to

be a strong component of a positive transition experience since a group association creates a bond that can be beneficial to those in a new environment. In Skinner’s (2004) case study on freshmen swimmers´ experiences in their transition to college the

swimmers expressed certain levels of anxiety during their first three weeks in college, that were consistent with the previous literature. The freshmen student swimmers then often looked to their peers for guidance and pointed out that the current team was a vital resource in their first three weeks adjustment phase (Skinner, 2004).

First-year students who make effective adjustments to college life in terms of behaviour and emotions often rely on social support as a coping resource and engage in self-exploring processes. Students, who enter university with relatively low levels of perceived stress, and those who have frequent discussions with their parents, tend to experience better adjustment throughout the whole year (Giaccobbi, Lynn,

Wetherington, Jenkins, Bodendorf & Langley, 2004).

In a study of five female first-year university swimmers conducted in 1997 social

support from parents and team-mates were commonly reported as very important coping resources. This result is similar to previous empirical findings. It appears that strong social support networks combined with humour/fun is an important coping strategy for helping both athletes and non-athletes to cope with academic, non-academic, emotional, and athletic related stress during the transition to university life. The social networks give the athlete students emotional relief from daily rigorous training. (Giaccobbi, Lynn, Wetherington, Jenkins, Bodendorf & Langley, 2004).

4.5 Educational and vocational consequences of athletic

participation

A possible conflict between the role of student and athlete may occur since the student- athletes need to cope not only with the transition in their athletic career, but also with the basic transition from secondary education to higher education level. These

transitions require student-athletes to adjust to, and cope with, challenges and changes occurring in the combination of academics and athletics. That includes for example adjusting to campus life, selecting a subject to study, or a major, making the college team and preparing for a post university career (Wylleman, De Knop, Ewing &

Cumming, 2000). It has been proposed that the commitment and exclusive dedication that is necessary to excel in sport may restrict the opportunities for student-athletes´ to engage in exploratory behaviour, which is critical for a subsequent personal and career identity development (Murphy, Petitpas & Brewer, 1996). In Yiannakis (1981)

observations of male scholarship student-athletes in college he noted that athletes generally are preoccupied with competitions, practice, winning and the next game. A significant portion of an athlete’s waking consciousness is devoted to daydreaming about athletics. As a result, such students may not be as attentive to their educational and career plans as other students (Blann, 1985).

Anxiety about sport performances is a symptom frequently reported by student-athletes. Whether lowered performance is a symptom of some other psychological problem or whether it speeds up emotional distress, the impact can be the same: a downwards cycle of lowered efficiency accompanied by a reduction in self-esteem. This negative spiral can be even more critical for the scholarship athletes whose ability is the medium through which they receive an education (Pinkerton, Hinz & Barrow, 1987).

Although many athlete students believe that they will have great careers as professional athletes, the reality is that few athletes even get to try out with professional teams and that professional careers often are extremely short (Andersen, 2002, Pinkerton, Hinz & Barrow, 1987). The probability for a college athlete to progress into professional sport after this stage has been shown to be somewhat less than 2%. Because of that reason it is important that student-athletes also are prepared for other careers. The athletes who seem to be most negatively affected by this are male college scholarship athletes in revenue producing sports, regardless of the size of the institution (Kennedy & Dimick, 1987). These serious athletes are not often in a position to think of alternatives beyond professional sport participation. If they did so they would acknowledge that the goal of continuing in athletics may not be possible. Since such thoughts are a threat to their dreams, they are often denied and blocked out of the athletes’ conscience (Pinkerton, Hinz & Barrow, 1987).

5. Objective

The objective of this study is to prospectively investigate perceived demands and barriers for golf juniors in their transition from junior to senior level, with college golf in USA. The purpose of the study is also to find out what resources and coping

strategies the juniors think they will use or already use today in order to succeed with the transition.

6. Method

6.1 Participants

The study was conducted on nine junior golf players, four male and five female, at the age of 18 to 20 years. The participants come from different parts of southern Sweden and are all playing Swedish national junior competitions and on the Swedish senior pro tour (SAS Masters Tour). Most of the players have represented Sweden in different national junior teams and have competed in junior and senior amateur competitions in Europe. The criterias to be in this study was that the players should be in the Swedish golf junior elite and that they were going to USA to play college golf with start in autumn 2008. All of the players had been in contact with college golf coaches or offered athletic scholarships on colleges in USA.

6.2 Instrument

The study was carried out with interviews. A semi-structured interview guide was used consisting of two main themes: Expected general life changes/challenges and expected changes/challenges within golf connected to the transition. The first part of the

interview guide focused on changes that the athletes expected to occur in their daily life such as relationships with family and friends, school or other responsibilities outside sports, e.g. living and travelling on their own. The athletes were also asked to describe their worries and what they thought could prevent them from a successful adjustment to the every day life in USA. Furthermore the athletes were asked about what resources and strategies they thought could help them to adapt to the changes and handle the new challenges. The second part of the interview guide focused on the expected changes/

challenges within golf connected to the transition. The athletes were asked to describe their expectations on for example training, competitions, organization and relations to coaches and team-members. There were also questions about their worries and about what they thought could prevent them from a successful transition. Finally the second theme also included questions about what resources and strategies they thought could help them to handle the new challenges. (See appendix 1) A pilot study was conducted to estimate the approximate time of the interview and to see if the questions were understandable and relevant for the purpose of the study. Minor changes were made.

6.3 Procedure

All participants were selected in collaboration with the two captains of the Swedish junior golf team for boys and girls. The players were contacted by telephone and consented to participation in the interviews. They were informed about the purpose of the study and information about ethical issues was emphasized. Nine out of ten players agreed to participate in the study. Time and place for the interviews were arranged individually. Before the interviews were conducted, the participants were informed of their rights. They were informed that the participation in the study was voluntary and that all data would be treated with confidentiality. The interviews lasted between 45-60 minutes and were recorded on a dictaphone. The interviews were conducted in January 2008, which was approximately six months before the players planed to move to USA.

6.4 Data analyses

First the recorded interviews were transcripted in their whole extent. After that all the interviews were highlighted in different colours and read several times in order to get a clear understanding of the participants’ thoughts and experiences. Based on the different questions of the interview guide the most relevant texts were selected and organized. Each question was analyzed separately and organized into different raw data units that were divided into low order themes. From the low order themes high order themes were generated. Some of the participants’ information weren’t categorized due to irrelevance to the purpose. To decrease the author’s bias, a triangulation took place. In this case two researchers independently treated the data, and then discussed it to achieve a consensus in case of disagreements.

7. Result

7.1 Changes/challenges in everyday life that the players expect to

occur in their transition from junior to senior level in golf.

The participants were asked about what changes/challenges they expect to occur in their everyday life when they move to USA to play college golf. The answers have been divided into four categories; General expectations on the move to USA and how it will

affect the everyday life, Expected changes/challenges in relations with family and friends, Expected changes/challenges in culture and language and Expected

changes/challenges in school, responsibility for their own household and in time for leisure.

7.1.1 General expectations on the move to USA and how it will affect the

everyday life.

The participants were asked about their general expectations on the move to USA and how they think it will affect their everyday life. Table 2 presents raw data units, low and high order themes for the category ”General expectations on the move to USA and how it will affect the everyday life”. Out of the total 13 raw data units that were generated for the high order theme “Expected changes in everyday life ” 38 % were purely idiosyncratic (individual), that is, stated by only one athlete. The most commonly mentioned low order theme was ”Do not expect the everyday life to change”, with raw data units such as ”I don’t think my life will change very much” and ”Not much change since I only play golf and study today anyway”. This low order theme covered 8 raw data units, which is 62 % out of the total number of raw data units. The low order theme ”Expect the everyday life to change” was supported by 5 raw data units.

Out of the total 11 raw data units that were generated for the high order theme ”General feelings about the move to USA” 73 % were purely idiosyncratic. The most commonly mentioned low order theme was ”Positive feelings”, with raw data units such as ”It will be fun” and ”The freedom feels nice”. This criterion covered 7 raw data units, which is 67 % out of the total number of raw data units. ”Negative feelings” with raw data units such as ”I’m a little bit worried about this” and ”I will probably be homesick” covered 4 raw data units.

The third high order theme was ”Expected challenge”, which covered 8 raw data units.

Table 2. General expectations on the move to USA and how it will affect the everyday

life.

According to table 2 the participants don’t expect their everyday life to change in any drastic way. Some of them already live at golf boarding schools in Sweden or report that their life only consists of golf and studies today anyway, so they don’t expect their lives in USA to be very different. Most of the athletes reported of overall positive feelings about the move. The players think it will be fun and have huge expectations on their new lives. Some of the players also feel a little bit nervous about the move though.

Some of the participants see the move to USA as a new challenge, while some of them state that they are prepared for the changes and don’t see the move as a challenge with any particular obstacles.

High order themes

Raw data units Low order themes

General expectations on the move to USA and how it will affect the everyday life. It will be fun (3)

The freedom feels nice (1) I have huge expectations (1) Fun to move to a new place (1)

Positive to learn how to take care of your self (1) I’m a little bit worried about this (1)

I will probably be homesick (1)

There will be some kind of reaction the first days (1) Mixed feelings (1)

Negativ emotions (4) Positiv emotions (7)

General feelings about the move to USA (11)

It feels like a new challenge (2) It feels like a big step (1)

I have to put higher demands on my self (1)

A challenge to move to USA (4)

I have been to USA and played golf before so I know how it works (2)

I can’t se any obstacle (1)

I have travelled a lot so I know how to do (1)

Expected challenge (8)

No challenge (4) I don’t think my life will change very much (4)

Not much change since I only play golf and study today anyway (1)

I don’t expect the everyday life to be any different (1) I don’t think it is a big difference from the Swedish golf boarding school (1)

I don’t think there will be a big difference since there are many Scandinavian golf players on the college (1)

Do not expect the everyday life to change (8)

There will definitely be some differences (2) My life will change very much (2)

It will be difficult having time to take care of everything in the beginning (1)

Expected changes in everyday life (13)

Expect the everyday life to change (5)

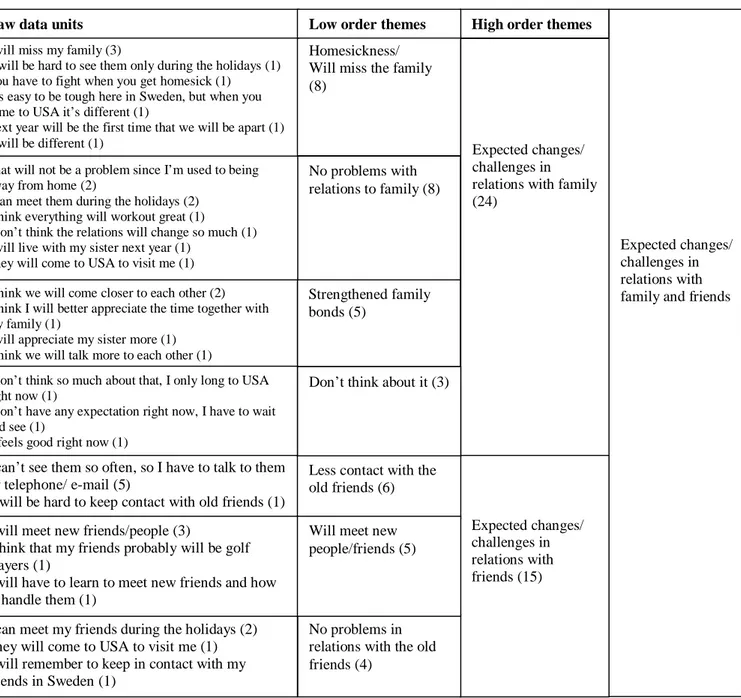

7.1.2 Expected changes/ challenges in relations with family and friends

The participants were asked about expected changes/challenges in relations with family and friends. Table 3 presents raw data units, low and high order themes for the category ”Expected changes/challenges in relations with family and friends”. Out of the total 24 raw data units that were generated for the high order theme ”Relations with family” 63 % were purely idiosyncratic. The most commonly mentioned low order themes were ”Homesickness/ will miss the family” and ”No problems with relations to family”. These criterias covered 8 raw data units each, which is 33 % out of the total number of raw data units. The low order theme ”Strengthened family bonds” with raw data units such as ”I think I will better appreciate the time together with my family” covered 5 raw data units. Some of the golf juniors also reported that they didn’t think about their relations to the family.

Out of the total 15 raw data units that were generated for the high order theme ”Relations with friends” 33 % were purely idiosyncratic. The most commonly

mentioned low order theme was ”Less contact with the old friends”, with raw data units such as ”I can’t see them so often, so I have to talk to them by telephone/ e-mail” and ”It will be hard to keep contact with my old friends”. This criterion covered 6 raw data units, which is 40 % out of the total number of raw data units. The secondly most mentioned low order theme was ”Will meet new people/friends”, which covered 5 raw data units. Some of the athletes also reported that they didn’t see any problems in their relations with the old friends.

Table 3. Expected changes/challenges in relations with family and friends.

According to table 3 many of the participants think that they will miss their families and get homesick, but a large share of the players also think that there will be no problems and that the move to USA even can lead to strengthened family bonds. They believe that they will talk to their families often and appreciate the time that they have together with the family more. Some players stated that they didn’t expect any problems in their relations to the families since they were used to being away from home and since they could meet their parents during holidays and other visits.

Many of the players think that it will be hard to keep in contact with their old friends in Sweden, but they believe that they will meet new friends in USA. Some of the players

High order themes

Strengthened family bonds (5)

I will miss my family (3)

It will be hard to see them only during the holidays (1) You have to fight when you get homesick (1) It’s easy to be tough here in Sweden, but when you come to USA it’s different (1)

Next year will be the first time that we will be apart (1) It will be different (1)

I can meet my friends during the holidays (2) They will come to USA to visit me (1) I will remember to keep in contact with my friends in Sweden (1)

Homesickness/ Will miss the family (8)

I think we will come closer to each other (2) I think I will better appreciate the time together with my family (1)

I will appreciate my sister more (1) I think we will talk more to each other (1)

I can’t see them so often, so I have to talk to them by telephone/ e-mail (5)

It will be hard to keep contact with old friends (1)

Expected changes/ challenges in relations with family (24)

Raw data units Low order themes

Expected changes/ challenges in relations with family and friends

Expected changes/ challenges in relations with friends (15) That will not be a problem since I’m used to being

away from home (2)

I can meet them during the holidays (2) I think everything will workout great (1)

I don’t think the relations will change so much (1) I will live with my sister next year (1)

They will come to USA to visit me (1)

No problems with relations to family (8)

Don’t think about it (3) I don’t think so much about that, I only long to USA

right now (1)

I don’t have any expectation right now, I have to wait and see (1)

It feels good right now (1)

Less contact with the old friends (6)

No problems in relations with the old friends (4)

I will meet new friends/people (3)

I think that my friends probably will be golf players (1)

I will have to learn to meet new friends and how to handle them (1)

Will meet new people/friends (5)

don’t expect any problems in their relations with the old friends since they can meet them during holidays and expect them to visit in USA.

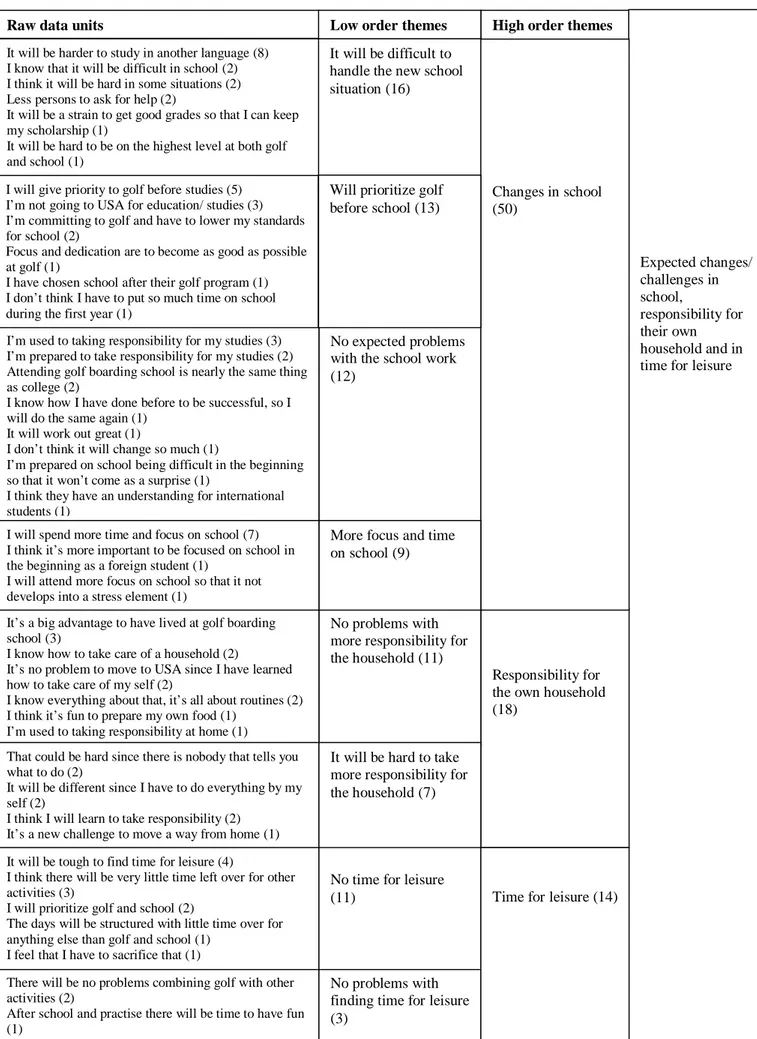

7.1.3 Expected changes/challenges in school, responsibility for their own

household and in time for leisure

The participants were asked about expected changes/challenges in school, responsibility for their own household and in time for leisure. Table 4 presents raw data units, low and high order themes for the category ”Expected changes/challenges in school,

responsibility for their own household and time for leisure”. Out of the total 50 raw data units that were generated for the high order theme ”Changes in school” 24 % were purely idiosyncratic. The most commonly mentioned low order theme was ”It will be difficult to handle the new school situation” with raw data units such as ”It will be harder to study in another language” and ”Less persons to ask for help”. This low order theme was created by 16 raw data units, which is 32 % out of the total number of raw data units. The secondly most commonly mentioned low order theme was ”Will prioritize golf before school”. This criterion covered 13 raw data units such as ”I will give priority to golf before studies” and ”I have chosen school after their golf program”. The low order theme ”No expected problems with the school work” covered 12 raw data units, e.g. ”I’m used to taking responsibility for my studies”. The low order theme ”More focus and time on school” covered 9 raw data units.

Out of the total 18 raw data units that were generated for the high order theme ”Responsibility for the own household” 17 % were purely idiosyncratic. The most commonly mentioned low order theme in this category was ”No problems with more responsibility for the household”, with raw data units such as ”It’s a big advantage to have lived at golf boarding school” and “I know how to take care of a household”. This low order theme was created by 11 raw data units, which is 61 % out of the total number of raw data units. The low order theme ”It will be hard to take more responsibility for the household” covered 7 raw data units.

Out of the total 14 raw data units that were generated for the high order theme ”Time for leisure” 21 % were purely idiosyncratic. The most commonly mentioned low order theme was ”No time for leisure”, which covered 11 raw data units. ”No problems with finding time for leisure” covered 3 raw data units.

Table 4. Expected changes/challenges in school, responsibility for their own household

and in time for leisure.

High order themes

Raw data units Low order themes

Expected changes/ challenges in school, responsibility for their own household and in time for leisure

Responsibility for the own household (18)

No problems with more responsibility for the household (11) It’s a big advantage to have lived at golf boarding

school (3)

I know how to take care of a household (2) It’s no problem to move to USA since I have learned how to take care of my self (2)

I know everything about that, it’s all about routines (2) I think it’s fun to prepare my own food (1)

I’m used to taking responsibility at home (1)

No expected problems with the school work (12)

It will be harder to study in another language (8) I know that it will be difficult in school (2) I think it will be hard in some situations (2) Less persons to ask for help (2)

It will be a strain to get good grades so that I can keep my scholarship (1)

It will be hard to be on the highest level at both golf and school (1)

It will be difficult to handle the new school situation (16)

I’m used to taking responsibility for my studies (3) I’m prepared to take responsibility for my studies (2) Attending golf boarding school is nearly the same thing as college (2)

I know how I have done before to be successful, so I will do the same again (1)

It will work out great (1)

I don’t think it will change so much (1)

I’m prepared on school being difficult in the beginning so that it won’t come as a surprise (1)

I think they have an understanding for international students (1)

Changes in school (50)

Will prioritize golf before school (13)

More focus and time on school (9) I will spend more time and focus on school (7)

I think it’s more important to be focused on school in the beginning as a foreign student (1)

I will attend more focus on school so that it not develops into a stress element (1)

That could be hard since there is nobody that tells you what to do (2)

It will be different since I have to do everything by my self (2)

I think I will learn to take responsibility (2) It’s a new challenge to move a way from home (1)

It will be hard to take more responsibility for the household (7)

There will be no problems combining golf with other activities (2)

After school and practise there will be time to have fun

No problems with finding time for leisure (3)

It will be tough to find time for leisure (4)

I think there will be very little time left over for other activities (3)

I will prioritize golf and school (2)

The days will be structured with little time over for anything else than golf and school (1)

I feel that I have to sacrifice that (1)

No time for leisure

(11) Time for leisure (14)

I will give priority to golf before studies (5) I’m not going to USA for education/ studies (3) I’m committing to golf and have to lower my standards for school (2)

Focus and dedication are to become as good as possible at golf (1)

I have chosen school after their golf program (1) I don’t think I have to put so much time on school during the first year (1)

The conclusion of table 4 is that the players expect it to be difficult and hard to study at college in USA, and especially to study in another language. Most of the players state that they will prioritize golf before studies. Their main focus is to succeed in golf, so school will come in second place. Since many of them are used to, and prepared to, take responsibility for their school work they don’t expect school to be a major problem though. Many players also state that they will spend more time and focus on school than before.

Some of the players state that they have prior experiences on how to take care of a household, e.g. through living at golf boarding schools. These players have learned how to take care of themselves and state that they will not have any problems with an

increased responsibility for the household. Other players state that it will be hard to take more responsibility for the household since nobody will tell them what to do and

because they will have to do everything by themselves.

The majority of the players expect it to be difficult to find time for leisure. They will prioritize golf and school and not have so much time left to participate in other activities. A minority of the players doesn’t expect it to be any problems combining golf, school and other activities.

7.1.4 Expected changes/challenges in culture and language

The participants were asked about what changes/challenges in culture and language they expect to meet. Table 5 presents raw data units, low and high order themes for the category ”Expected changes/challenges in culture and language”. Out of the total 20 raw data units that were generated for the high order theme ”New language” 40 % where purely idiosyncratic. The most commonly mentioned low order theme was ”Positive thoughts about speaking / learning English” with raw data units such as ”I have no problems with English” and ”To learn English well is like a bonus”. This criterion covered 15 raw data units, which is 75 % out of the total number of raw data units. The low order theme ”Negative thoughts about speaking English” covered 5 raw data units.

Out of the total 10 raw data units that were generated for the high order theme “Cultural differences” 60 % were purely idiosyncratic. ”General thoughts about learning to know