Department of Global Political Studies Peace and Conflict Studies 61-90 Bachelor Thesis Malmö University Spring 2013

Stopping Destructive Arms Proliferation:

How the Arms Trade Treaty can improve peace and

security by introducing the first international

regulations on transfers of conventional arms

Author: Simon Saldner

19880206-1971

Supervisor: Darcy Thompson Total Number of Words: 16 420

This thesis explores how the newly adopted Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), the first international treaty to regulate the trade in conventional arms, can address the issue of the illegal and irresponsible proliferation of small arms and lights weapons (SALW) and improve peace and security. By far the most commonly used weapons in modern conflicts, SALW and their effects mainly on intrastate conflicts, I argue, are the most important issues for the ATT to address. Being one of the prime sources of fuel for, and even cause of, the new trend of increasingly deadly and destructive intrastate conflicts today, controlling the largely illegal and internationally unregulated SALW market would be a crucial step to improving peace and security.

The thesis uses Security Dilemma theory to describe how arms and their proliferation pose threats to peace and security, while international law and regime theory is used to identify how legal action and structures of cooperation (regimes) can offer solutions to these problems. To determine to what extent the ATT can address these issues, the thesis uses a case study approach together with a content analysis of the ATT text to identify the relevant legal provisions and how they can operate in the context of the theoretical framework.

The findings of this study suggest that the most important aspect of the ATT is that it imposes prohibitions on any arms transfer that risks being used to commit acts of genocide, human rights abuses and other violations of international law, or that risk leading to diversion. These provisions could be used to stop the irresponsible kinds of arms transfers that facilitate these crimes. The effects of the ATT are however largely dependent on the will of states, which will determine the effectiveness of the treaty. Nonetheless, as this thesis shows, the ATT provides tools and a legal platform that could, if utilized, have a substantial impact on these issues.

Title: Stopping destructive arms proliferation - How the Arms Trade Treaty can improve

peace and security by introducing the first international regulations on transfers of conventional arms

Key words: Arms; Arms Trade; Arms Trade Treaty; Intrastate conflict; International law;

I owe a great deal to my supervisor Darcy Thompson. Supervisors listening to their students have to suffer like the wedding-guest who “cannot choose but hear”. But far from just being my hostage during our supervision meetings, Darcy went out of her way to help me through meetings, emails and weekend Skype sessions even though I know she has plenty of other more important (and probably more interesting) things to attend to. With her clever and kind advice Darcy managed to transform the incoherent jumble of ideas that I brought to her into a workable thesis, and for this she deserves more credit for this thesis than I can acknowledge. I also want to thank Elli Kytömäki and my former colleagues at UNIDIR, who it was a privilege to work with and get to learn during my internship with them, and who helped introduce me -among many other things- to the intricacies of the Arms Trade Treaty.

1. Introduction ...1 1.1 General introduction ...1 1.2 Layout ...2 1.3 Research problem ...3 1.4 Aim of study...4 1.5 Delimitations ...5 1.6 Previous Research ...7 2. Background ...9

2.1 The Arms Trade Treaty ...9

2.2 Contents and Purpose of the Arms Trade Treaty ... 11

2.3 Intrastate Conflicts ... 13

2.4 Small Arms and Light Weapons ... 17

3. Methodological Framework ... 20

3.1 Choice of method ... 20

3.2 Ontological and epistemological discussion ... 20

3.3 Case Study ... 21

3.4 Content Analysis ... 22

4. Theoretical Framework ... 24

4.1 Choice of theory ... 24

4.2 The Security Dilemma ... 25

4.2.1 Arms and Arms races ... 26

4.2.2 Anarchic Structures and the Security Dilemma ... 27

4.2.3 The Security Dilemma in Intrastate Conflicts ... 27

4.3 International Law ... 29

4.4 Regime Theory ... 30

5. Analysis ... 33

5.2.1 Preventing diversion and wrongful use of arms ... 33

5.2.2 Transparency and Cooperation Measures ... 37

5.3 Indirect Effects ... 39

5.3.1 Strengthening International Law ... 39

5.3.2 Strengthening the Arms Control Regime ... 43

6. Critical Discussion ... 44

7. Conclusions ... 47

8. Sources ... 50

ATT - Arms Trade Treaty

CIL - Customary International Law IHL - International Humanitarian Law ILC - International Law Commission ICC - International Criminal Court

PoA - Programme of Action to Prevent, Combat and Eradicate the Illicit trade in Small Arms and Light Weapons In All Its Aspects

RT - Regime Theory

SALW - Small Arms and Light Weapons SD - Security Dilemma

1. Introduction

1.1 General introduction

The trade in arms is paradoxical in that it is a highly globalized phenomenon, while being almost completely outside the control of global institutions. It has the most dangerous potential of being misused, yet it is virtually unregulated at the global level. This has been particularly true of Small Arms and Light Weapons (SALW), the ubiquitous portable weapon systems perhaps most readily associated with the handguns, automatic rifles, rocket launchers etc. that is commonly seen used by militants, criminal gangs and other armed groups in everyday news items. SALW are by far the most commonly used in today‟s warfare, and therefore arguably have the most devastating effects on global peace and security.1 It is hard to make accurate estimates, but by all accounts the world has vast numbers of weapons. Some estimates put the total number of SALW alone at approximately 875 million, out of which the bulk of weapons, some 650 million, are in civilian hands.2 The number of bullets produced each year number around 12 billion.3 The destructive effects of arms proliferation on peace and security are well attested - including exacerbating conflicts in weak states and undermining peace efforts4, facilitating human rights offences,5 and as being the one of the largest single contributors to corruption world-wide.6 The arms trade has important impacts on issues of poverty and development, the prospects for peace-building, geopolitics and the making of strategic alliances, geo-economics, international terrorism and more.7 Arms constitute natural precondition and even a driving factor behind armed conflicts. The security

1

“Small arms and light weapons were the only weaponry used in 46 out of the 49 recorded regional conflicts between 1990 and 2000”: DiGiusto, 2007, p.249:

See also: O‟hanlon 2005, p.113

2

Small Arms Survey 2011, p. 1

3 Wallacher; Harang 2011, p.2 4 SIPRI 2013, p.5 5 Amnesty International 2010, p.3 6

See also: Pyman 2009, p. 5

7

dilemma theory (SD) is an effective way of illustrating this, showing how the mere presence of arms can be enough to aggravate tensions between groups to the point of war, as is commonly recognized in an arms race. Despite this, the international arms market has been almost entirely unregulated.8

The lack of action on arms control is largely owed to the fact that any multi-lateral agreements relating to arms are notoriously hard to reach at the international level. It was therefore a historically significant event when in April 2013, the first international treaty to regulate the international arms trade was adopted in United Nations General Assembly. „The Arms Trade Treaty‟ (ATT) is meant to regulate the trade in conventional arms, ammunition and parts, and to impose prohibitions on arms transfers that may lead to e.g. human rights abuses, genocide or violations of international law. This is the first instance where some of the norms concerning what are generally considered unacceptable arms transfers (e.g. the Russian arms transfers to the oppressive Syrian regime during the on-going civil war) find concrete expression in international law. This gives many reason to hope that the adverse effects of arms trade can finally be addressed, while others have cast grave doubts over the ATT‟s potential to make a concrete impact, pointing e.g. to the previous failures of the international arms control regime and to weaknesses in the ATT text.9

1.2 Layout

This thesis explores to what extent arms control measures as employed by the ATT can address the issues of SALW proliferation and intrastate conflicts. In section 2 are described the background and contents of the ATT. I also provide a general background on SALW and intrastate conflicts, and motivate why I consider these to be the two most important areas in need of arms control measures. In section 3 I develop the methodological framework of the study, which relies on a case study analysis of the ATT, together with a content analysis of the ATT text. In section 4 I develop the theoretical framework used to inform the study. I use security dilemma theory, which describes the aggravating and destabilizing effects of arms, as

8

For an overview of the global arms trade, and the issues connected to proliferation and lacking regulation, see: Control Arms 2006:

http://controlarms.org/en/news/states-vote-overwhelmingly-for-ground-breaking-arms-trade-treaty/.

9

For an example of some differing reactions from arms control NGO‟s, see:

Control Arms. "States Vote Overwhelmingly for Ground-breaking Arms Trade Treaty." Available at:

http://controlarms.org/en/news/states-vote-overwhelmingly-for-ground-breaking-arms-trade-treaty/.

See also: Campaign Against Arms Trade. "Arms Trade Treaty." Caat.org.uk/. Campaign Against Arms Trade, 30 Apr. 2013. Web. 27 May 2013. <http://www.caat.org.uk/issues/att/>.

well as international law and regime theory to describe some of the solutions to these problems. In the analysis of section 5, I explore to what extent the ATT can address some of the issues identified in this thesis. Section 6 provides a critical discussion of the results and an assessment of the possible impact of the ATT on the issues described. Finally, in section 7 I present the conclusions of the study.

1.3 Research problem

Arms control and its related issues is a large topic that is the subject of study in many fields - including international relations, international and domestic law, development studies and peace and conflict studies. There are therefore many different approaches to take on the causes of and solutions to arms related issues. The problems associated with arms proliferation are not limited to or caused exclusively by arms or the lack in regulation thereof. There are of course innumerable social, political and economic factors - both at the higher, international level as well as at the grassroots - that contribute to the „demand‟ for arms. The causes of arms proliferation can be explained in terms of state political motives (as when for example the US transferred large shipments to the Contras of Nicaragua and Mujahedeen of Afghanistan in the 80‟s); the economic interests of military industries; or societal factors such as poverty and inequality, crime, nationalism and so forth.10 Likewise, the solutions are not limited to the international level of UN decision-making and treaties.

A common feature however is that arms, particularly in modern times, usually have international dimensions - in terms of their sources, areas of use or both - ignoring national boundaries and spilling over across societies,11 which has contributed to making arms and arms transfers an international concern. This is one of the reasons why arms has long been the subject of attempted or enforced international agreements, limiting which weapons can be used and how. The ever increasing destructiveness of arms during the 19th and 20th century, together with the increasing involvement of civilians in war, advanced the development of international humanitarian law (IHL) regulating the rules of conduct in war - both of states, combatants and their use of arms. Several attempts to limit the destructiveness of war were made, through e.g. the Hague and Geneva conventions, the League of Nations on to the

10

For more on this subject, see: Hartung 2013

11

Trade in particular has long been recognized for its tendency to escape state borders. The World Trade Organization predicted that, at the turn of the 21st century, around 60% of the world trade would be conducted without any customs barriers. Stern 2000, p. 248

United Nations - but the experiences of the 20th century shows that these attempts have been far from satisfying.12 This failure must be largely attributed to the political impasse of the cold war period as well as the intractable nationalist policies and extreme political climate of the 20th century in general. But even in the more cooperative climate of today, reaching solutions to arms control and related issues has proved difficult.

The ATT raises important questions about the future development of the arms control regime, and opens up new possibilities for controlling the international flow of arms and limiting its negative consequences. It also raises a number of questions as to if and how the ATT will be able to make an impact on peace and security issues in the future. In order to meet its goal, the ATT must not only be able to regulate the trade as such, but to be able to provide real security improvements. There are several ways one could attempt to measure such an improvement: trough studying its impact on organized crime, corruption levels, developmental factors etc., or even an ability to prevent inter-state conflicts. But since the most common and destructive conflicts today and for the foreseeable future is intrastate conflicts - driven, maintained and fought almost exclusively using SALW armaments, to a large extent obtained through illegal markets or irresponsible arms transfers - these are the most acute problems the ATT must be able to address.

1.4 Aim of study

My presupposition, as argued in the background section, is that the most common and destructive conflicts today take place within the intrastate context, involving combatants that are almost exclusively reliant on supplies of SALW and ammunition. Therefore, for the ATT to make real improvements on peace and security, the most important issue that the it needs to address is halting the irresponsible SALW proliferation that fuels these conflicts and makes possible human rights violations and other violations of international law that are some of the worst causes of human suffering and prolonged conflict today.

The aim of this study therefore is to explore to what extent the ATT can address and prevent the illegal proliferation and irresponsible trading of SALW and consequently to what extent this can help to prevent and halt intrastate conflicts.

12

To this end I will rely on previous research of the impact of arms proliferation in intrastate conflicts and explore to what extent the ATT can addressed some of the problems that have been identified there. I will make use security dilemma theory as a theoretical framework both to provide an explanatory model of how arms related issues such as arms races fuel conflicts, and in order to identify what arms control measures can achieve to prevent conflicts. I will also make use of other background research to identify and explain some of the issues connected to intrastate conflicts and SALW.

To summarize, the aims of this study are to:

● Investigate how measures imposed by the ATT can address the problems posed to peace and security by SALW in intrastate conflicts;

● Investigate how the ATT may contribute to the advancement of international law and the arms control regime;

● Position the ATT in a theoretical context;

● Identify what measures are inadequate or missing in the ATT

The overarching goal of this thesis is to provide a balanced picture of the ATT with its merits and demerits, and to place it within the theoretical context used in this study. Because of its recent adoption and the historical novelty of the ATT as being the first arms control instrument of its kind, this study can hopefully contribute by providing some preliminary findings with which to fill an initial gap of research. The aim is that the reader of this thesis will gain a better understanding of the ATT and its future effects, and how states and other groups can use the ATT for the interests of peace and security.

1.5 Delimitations

The reasons for choosing to explore intrastate conflicts and SALW have already been stated, but some further distinctions may still be needed. Intrastate conflicts encompass many different aspects and modes of conflict - terrorism for example, is a large area of study in its own right, and even if it occurs in the intrastate context, to cover the many issues peculiar to the study of terrorism are beyond the scope of this study. There are many other aspects of intrastate conflicts that deserve to be studied, for example criminal networks, ethnic, political or societal factors etc. are some of the approaches that can be used to explain the complex dynamics of intrastate conflicts. Since the focus of this study is on arms control of SALW in

the context of intrastate conflicts, I will not attempt to give a detailed theoretical account of how intrastate conflicts operate. Instead, I will only venture to give a brief background of what I believe are quite uncontroversial assertions, despite what theoretical approach one takes: that intrastate conflict is the most common and therefore important theatre of war today, that intrastate conflicts are fought almost exclusively using SALW, and that improved arms control of SALW is needed. The study will focus on how the ATT can improve the arms control of SALW in the interests of peace and security, and I will therefore focus on theories that directly address the issue of arms and arms control. These theories will be further described in section 4.

As will be explained in section 2.2, the ATT also covers large-scale conventional weapons. Such weapons are by no means unimportant to issues of peace and security, however these weapons are already subject to some regulation both international and domestic,13 and are by their nature less likely to be obtained or even successfully operated except by major state-owned army units that have, as I will argue, become increasingly irrelevant factors in modern conflicts. For these reasons, and those stated in section 2.3, the focus of this thesis is on SALW, together with its parts and ammunition. For roughly the same reasons as just stated, neither will I devote much attention to interstate conflicts. By interstate conflicts I mean the „classical‟ large-scale conflicts between states and their armies. It is not so much that the interstate level has become irrelevant - the intrastate conflicts I will describe are highly globalized phenomena that often involve trans-border interactions - it is rather that intrastate conflicts tend to ignore state boundaries. This will all be familiar to some as the „New Wars‟, but for reasons of simplicity and in order not to be too restricted by or risk abusing this theoretical concept, I will keep to the label of intrastate conflicts.14 By this label I mean to encompass the groups that are typically the recipients, users and victims of SALW, both state and non-state actors. These concepts will all be further defined in section 2.3 of this thesis. The basis for these delimitations, as already stated in section 1.4, is these are the issues that pose the main threats to peace and security today and are therefore the most important for the ATT to address.

13

Holtom, Paul, and Mark Bromley. "June 12: Looking Back to Ensure Future Progress: Developing and Improving Multilateral Instruments to Control Arms Transfers and Prevent Illicit Trafficking." SIPRI.org. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 12 June 2012. Web. 23 May 2013.

14

A justified objection to this thesis may be that: even though the ATT might address some of these issues, what reason is there to think that there will be enough political will to successfully implement it? It is indeed a very real possibility that countries such as the US, Russia and China will not ratify the treaty, limiting the effect of the ATT (more on this in the discussion section). I will not attempt to speculate as to whether the ATT will have this political support, however in the analysis I will evaluate some of the factors that may influence the levels of compliance and implementation.

Even though much research has been conducted on the ATT, and theoretical literature devoted to arms control issues, I have not found studies of the ATT in its present form in the theoretical literature except by short references of its on-going development. The future implications of the ATT, and its place within the theoretical literature and the arms control regime, I will contend constitute the biggest gaps in research at present. Because of the highly theoretical nature of this study, it is important to point out that in no way is this thesis aspiring to accurately predict how the ATT will or will not function once in effect. Since the ATT is a recent development – the concrete effects of which are still years in the future – the findings of this study will necessarily be somewhat speculative. With this in mind however, the study is aimed at giving a preliminary account of how the ATT relates to and can improve on the issues described in this thesis, of SALW proliferation and its role in intrastate conflicts, based on the contents of the treaty and the theoretical models used in this thesis.

1.6 Previous Research

There exists a large body of research on arms control and related issues, including the ATT. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) is one of the leading research institutes in the area, conducting empirical research including comprehensive data sets, analyses and recommendations on arms related issues, and its impact on peace and security. The United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR) has provided extensive research on the political development of the ATT - including analyses of states and international organizations positions towards the ATT - as well as detailed analyses of its technical aspects such as particular treaty provisions and issues. The ATT have been studied by a number of NGO‟s - such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and Oxfam - monitoring the flow of arms and its sources, as well as its humanitarian impacts. The ATT has also recently been the subject of a close legal analysis by the Geneva Academy of

International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights, for in-depth analysis of the ATT as a whole, refer to this report.15

Arms control is an important subject of analysis in many different fields, approached by a number of different schools and perspectives. Briefly summarized, arms control is subject to the same discussions between different approaches/paradigms as is common to topics within international law and peace and conflict studies, including: realist and liberal; state-centered and institutionalist; rationalist and constructivist debates. The legal dimensions of arms control also makes it relevant to international law theory where roughly the same debate applies, although with somewhat different implications, e.g. for legal interpretation. Because of its importance for this study, a longer discussion and a literature review of the theoretical framework will be provided in section 4.

15

2. Background

2.1 The Arms Trade Treaty

The ATT is a multilateral treaty negotiated under UN auspices and adopted in the general assembly on 2 April 2013,16 and is the first treaty to regulate the international trade in conventional weapons, including SALW. The purpose of the treaty is, briefly, to set common standards for the largely unregulated global arms market, to prevent arms from ending up in the wrong hands and from violating international law or committing human rights offences. Although there already exist a number of multi-lateral treaties regulating weapons of mass destruction, mines, cluster weapons and other particularly harmful weapon systems - the bulk of the arms trade including conventional weapons and SALW remained largely unaddressed by the international community until the adoption of the ATT. Regulating arms has long been a highly prioritized goal in the international community, as is reflected in the UN charter where a system of arms control was one its primary goals.17 However, despite several attempts, arms control proved perhaps the most difficult issue in which to reach international agreements, and very little progress was made.

SALW has hitherto been a largely neglected issue in international arms control negotiation and therefore its inclusion in the ATT marks a widening of the arms control regime. In view of this, the ATT marks a historic and important step forward in strengthening international peace and security and the international arms control regime, a regime which historically is marked by its slow progress and intransigent positions. At present, international arms control is mainly exercised through domestic jurisdictions. Provided that such jurisdiction even

16

General Assembly A/CONF.217/2013/L.3

17

exists, which is not the case in the majority of states today,18 it is often lax or subject to arbitrary decisions, even in well developed countries.

After 7 years negotiations, the ATT was intended to be adopted by consensus, which requires that there be no formal opposition from any state. In March 2013, Syria, North Korea and Iran alone prevented this from happening. The ATT was then sent on to the general assembly by April, where it was passed by a majority of 154 states voting in favour, including three Security Council members (the US, GB and France), while only three states voted against (again: Syria, North Korea and Iran). At the outset, the fact that the very states who may be among the most likely to be targeted by the ATT took such firm resistance to it suggests that they may have felt there was good reason to be apprehensive. Despite the apparent success, what impact the ATT will have is up to question, considering the limited impact that the UN has had on issues of peace and security in the past, particularly concerning arms control. It remains to be seen how many states will finally decide to ratify the treaty. The extent of support from the Security Council members, together accounting for around 70-80% of the global arms trade,19 will have a crucial impact. Moreover it remains to be seen how strong the treaty provisions will prove to be, and to what extent potential loopholes risk to undermine it.

But more important than the immediate effect of the ATT will be its staying power and ability to produce long term effects in strengthening the arms control regime. Regimes can be briefly summarized as systems of cooperation that arise in the international arena, around which different actors‟ behaviour converge. Textbook examples of regimes include the international postal, shipping and economic systems; as well as human rights and arms control. The importance of regimes is their ability to affect attitudes and behaviour - as a central concept in regime theory “...behaviour follows from adherence to principles, norms, and rules, which

legal codes sometimes reflect”.20

More specifically, arms control regimes strengthen the conventions of war by advancing the position that the use of certain weapons should be banned or limited, specifying which ones.21The development and future function of the ATT

is indeed largely dependent on how states will interpret and execute it, influencing the common practice or „praxis‟ which will in turn influence the development of the arms control

18

According to Oxfam International, only 90 countries employ national arms control. See: Oxfam 2013

19 Hartung 2013, p.443 20 Puchala, Hopkins p.62 21 Heinze 2012

„norm‟/‟regime‟.22

Echoing this fact, one representative speaking on behalf of 96 states after the treaty was passed, stressed how the ATT would need to adapt to future developments, and, ending on a note of due resolve and appropriate circumspection called for at such moments, concluded that: “This is just the beginning … the hard work starts now.”23

The rules applying to treaties are themselves contained in a treaty - the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. Treaties are in essence written, international agreements concluded between states governed by international law.24 Treaties are bi-lateral (between two states) or multi-lateral (involving more than two states) as with the ATT. Consenting to a treaty is voluntary - the ATT is therefore not legally binding (as e.g. a Security Council chapter VII resolution would be) even though it has been adopted, that is, until the state in question accepts it. This is done by signature and ratification. Since the ATT opened for signature in June 2013, states can sign the treaty25. The signature merely indicates that the state is interested to join the treaty in the future and does not make it legally binding, but it does obligate the state “not to take any action that would undermine the object and purpose of the treaty”.26

Once the state has signed, it can choose to ratify the treaty. Doing so means that the state is party to the ATT and legally bound to follow it.27 Finally, the ATT formally enters into effect a period after 50 states have ratified it.28

2.2 Contents and Purpose of the Arms Trade Treaty

This section is to give a brief outline of the ATT‟s general contents and purpose. The provisions of the ATT are wide-ranging, making them difficult to give separate accounts of. I will therefore sometimes refer to the articles in the ATT text (attached to this document as an appendix). More detailed accounts of the provisions will be provided in the analysis section (section 5).

The purpose of the ATT is as an arms control instrument, it is not designed as a disarmament mechanism. In practical terms, this means that the provisions of the ATT are not directly

22

Regimes will be more thoroughly described in section 4.3.2

23

UN general assembly 2013, GA/11354: General Statements

24

Wallace, Martin-Ortega 2009, p. 265

25

As of 2013-08-09, a total 81 states have signed the treaty.

26

United Nations (2013), Arms Trade Treaty: Signature and Ratification, article 1

27

Ibid. article 2

28

aimed at reducing arms levels either in terms of existing stockpiles or the arms on the marked - except those of the illegal markets. This has been criticized by some as giving undue legitimacy to the arms trade.29 All states are however to a large extent dependent on arms trade to sustain their military, which means that arms trade is and has been viewed as a legitimate practice by states historically. Many states were therefore apprehensive that the ATT would constrain this trade to the detriment of that most sacred of state rights - the right of self-defence.30 The ATT therefore explicitly recognizes legitimate arms trade (and without such an acknowledgement the ATT could hardly have been expected to pass).

The main objectives of the ATT (article 1) may be worth outlining in full. They are to: -”Establish the highest possible common international standards for regulating or improving

the regulation of the international trade in conventional arms;

- To prevent and eradicate the illicit trade in arms and their diversion.

- For the purposes of: Contributing to international and regional peace, security and stability; Reducing human suffering; Promoting cooperation, transparency and responsible action by States Parties in the international trade in conventional arms, thereby building confidence among States Parties.”

The contents of the ATT can roughly be divided into three main categories:

Scope31 - the materials and transfers to be included.

Criteria32 - what criteria are to be met before an arms transfer can take place, and;

Implementation33 - what measures that are to be taken to ensure that the ATT is followed

and implemented

The scope encompasses a range of major conventional weapons (tanks, aircraft, battleships etc.) already defined in an earlier multi-lateral instrument - The United Nations Registry of Conventional Arms (UNRCA) - with the addition of SALW, and the parts, components as well as ammunition needed to assemble and maintain the included weapon systems. The scope also includes the different kinds of transfers to be encompassed, including e.g. exports,

29

See for example: Campaign Against Arms Trade 2013; Feltham 2013

30 Kytömäki, UNIDIR 2012, p.10 31 ATT article 2-5; 8-10 32 ATT article 6,7 33 ATT article 12 - 19

imports, brokering and trans-shipments. The provisions imply that not only importers and exporters are responsible, but also third party states acting as “middle men”.

The transfer criteria are the core of the treaty. They obligate states to make a series of risk assessments before they approve of arms transfers. States are forbidden to authorize transfers that violate their international obligations, in particular to Security Council obligations and arms embargoes. Before accepting a transfer the state also has to assess if it risks being used for e.g.: human rights abuses; genocide; illegal diversion; violations of international law and the 1949 Geneva conventions.

The implementation measures are simply concerned with how to implement and enforce the measures of the treaty. This is the main responsibility of state, and the provisions mainly instruct states on how to make appropriate adjustments to their national legislation and its enforcement. However implementation also includes measures at the international level. These include monitoring state compliance; transparency measures; dispute settlements; assistance with implementation; funding etc. - some of which will be handled by an international secretariat for the ATT.

An important tool of the ATT, and an end towards the purpose of building confidence among states (as outlined in the last paragraph of article 1), is the use of „transparency measures‟. By making the arms trade „transparent‟ e.g. by the act of enforcing reporting mechanisms where states have to be open about their arms trade and stockpiles, the aim is to avoid build-ups of dangerous and destabilizing arms accumulations by building confidence among member states - this is recognizable as a central themes in the SD.

2.3 Intrastate Conflicts

Intrastate conflicts (variously labelled „internal‟, „domestic‟, „civil‟ conflicts or „societal wars‟) can be difficult to define. Though generally accepted to be confined within the borders of a single state, intrastate conflicts are nonetheless often „internationalized‟, i.e. involve outside actors as with ISAF and other international forces in Afghanistan; or they can even be difficult to distinguish from interstate wars - as in the case of Russia in North Ossetia/Georgia. Intrastate conflicts may also be difficult to distinguish from one-sided or state-sponsored violence. A typical definition of intrastate conflict generally includes that the

conflict is: a) inside of state borders; b) Involves the government; and c) involves effective resistance from both sides.34 But this definition may be extended to include foreign involvement or reduced to only involve non-state actors.35 For my use and understanding of the definition, refer back to section 1.5.

Since the end of the second world war, and particularly after the end of the cold war, conflicts between states have become less and less common, instead the vast majority of conflicts today take place within states. Since the Second World War, around two-thirds of the conflicts have been intrastate conflicts and only 17% „classical‟ interstate conflicts, which is a notable break from former trends.36 Intrastate conflicts were on a steep rise during the cold war while interstate wars have been in decline, both in terms of numbers and magnitude (see figure 1 below).37 It can be argued that with few exceptions, only two kinds of war are fought today: „civil wars‟ and „policing wars‟.38

Civil wars are most often waged in poor countries by non-state actors using irregular troops - such as rebels, warlords, terrorist, criminal organizations etc. - fighting over sectarian issues, weak governments or just for private gain and loot. Policing wars are efforts, usually by developed countries, to intervene in intrastate conflicts or in countries ruled by despotic regimes, with the stated goal of restoring order.

In terms of levels of destruction, intrastate conflicts are particularly devastating - it is estimated that over 20 million deaths resulted from intrastate conflicts since WWII, most of which were civilian. This may be caused in large part by the fact that intrastate conflicts generally involve non-state actors that are often difficult to distinguish from civilians, which means that civilians are often drawn into or even become targets in the conflict, leading to practices of rape and other human rights violations, mass killings or even genocide.39 As the state descends further into chaos, such practices become more wide-spread, and as entire societies get drawn into the violence, conflicts become embittered and more difficult to resolve.

34

Smith 2010, p.99

35

For more developed definitions, The Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) is a commonly cited authority. UCDP definitions are available at: http://www.pcr.uu.se/research/ucdp/definitions/

36

Morgan 2006, p. 163, 164:

“For at least the past 180 years, with an exception during the cold war period, war has been in decline, with 150 states not experiencing war at all, 49 states one or two times, and only 8 states being at war 10 times or more.”

37

Large scale inter-state conflicts proving as exceptions to the trend since WWII being: the Arab-Israeli wars, the Vietnam war, the wars involving Iraq, and the Ethiopia-Eritrean war.

Systemic Peace, 2011, pp. 4, 5

38

Mueller 2006, p. 73, 74

39

The increase of internal conflicts is part of the new patterns of conflict that has emerged since WWI. Today‟s conflicts usually grow out of a state of anarchy or lawlessness, and feed of criminal activity and black markets. These conditions generally result from the weakness, incompetence or even complete failure of states or their governance. Between the years of 1955-2003, the research project „Political Instability Task Force‟ has identified 141 episodes of political instability world-wide.40 Weak states generally suffer from all manner of problems, including: weak economies, failing infrastructure, rampant corruption, poor rule of law, weak institutions, high crime rates and more - they are also much more prone to outbreaks of conflict (see figure 2). Importantly, weak states often lose the ability to impose authority over their territory, which leaves paramilitary bands, terrorists and other armed groups outside of state reach, letting them operate more or less freely.41 These combatants usually do not have the economic means, logistical capability and training required to command modern large scale military equipment like tanks and aircraft, instead they rely on unconventional tactics and the use of SALW. These new patterns of conflicts described above are sometimes labelled the „New Wars‟, from a theory most prominently represented by Mary Kaldor. Key features in New Wars is the low-intensity power struggles based upon and mobilized around nationalist or sectarian grounds, with limited or no involvement of the state and with many global connections ignoring state boundaries. Another key feature is the way these wars are driven by a “Globalized War Economy”:

“...these economies are heavily dependent on external resources. In these wars, domestic production declines dramatically because of global competition, physical destruction or interruptions to normal trade, as does tax revenue. In these circumstances, the fighting units finance themselves through plunder, hostage-taking and the black market or through external assistance.”42

This makes New Wars the magnets of international black marked trade, where SALW is an integral part. SALW is also necessary in order for the fighting units to continue the extortion which is so important to their upkeep.

40

Political Instability Task Force 2005, p. 5

41

Krasner 2008, pp. 180, 181

42

Figure 1. Global Trends in Armed Conflict, 1946-201043

(By: The Center for Systemic Peace, 2011)

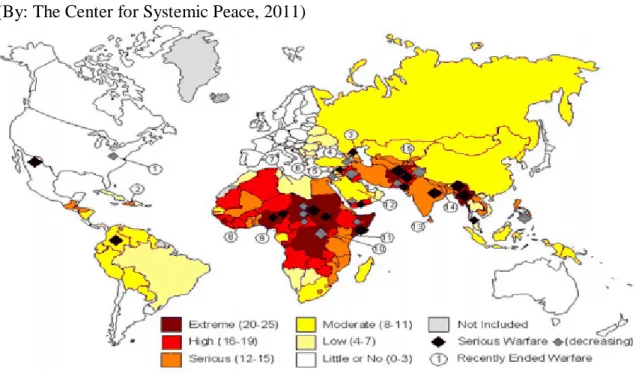

Figure 2. State Fragility and Warfare in the Global System, mid-201144

(By: The Center for Systemic Peace, 2011)

43

The Center for Systemic Peace 2011, p. 3:

“Interstate and civil wars must have reached a magnitude of over 500 directly-related deaths to be included in the analysis. The magnitude of each “major episode of political violence” (armed conflict) is evaluated

according to its comprehensive effects on the state or states directly affected by the warfare, including numbers of combatants and casualties, affected area, dislocated population, and extent of infrastructure damage. It is then assigned a score on a ten-point scale; this value is recorded for each year the war remains active.”

44

Ibid, p. 5: The figure uses the same data set and criteria as described in the above footnote. For the complete data-set, coding and methodology, see: http://www.systemicpeace.org/warlist.htm

2.4 Small Arms and Light Weapons

As with intrastate conflicts, SALW is a broad term that can be difficult to accurately define. SALW weapons range from small pistols and rifles to missile launchers capable of destroying tanks or large aircraft in mid-flight. A United Nations Panel of Governmental Experts on Small Arms was convened in 1997 to determine the nature and effects of the ill-defined SALW category. The definition they agreed upon included 21 categories of weapons, including e.g.: machine guns, mortars, explosives, rocket launchers, assorted ammunitions etc.45 They further distinguished small arms from light weapons in that: “Broadly speaking,

small arms are those weapons designed for personal use, and light weapons are those designed for use by several persons serving as a crew.”46

Small arms are handheld weapons such as the ubiquitous Kalashnikov rifle, while the light weapons operated by crews are such as the mortar equipment used at the Markale massacres during the siege of Sarajevo.

The same UN panel on SALW quoted above also described the devastating impact that SALW has on intrastate conflicts and is found to be closely tied to its increasing prevalence.47 SALW empowers irregular troops, insurgents, terrorists, criminal gangs etc., eroding the legitimacy and authority of governments, making it difficult for them to cope with both the causes and the effects of its proliferation. SALW are easily obtained, concealed, and can be used to devastating effect by practically anyone without requiring much training - this means that the weapons can be thrust into the hands of child soldiers of a very young age, something which is commonly exploited in many intrastate conflicts.48

Since the end of the cold war and the collapse of the Soviet Union, vast quantities of formerly state-owned SALW armaments spilled out on the global market, often into the hands of non-state actors, and further exacerbated the destructive new conflict trends. The UN panel was one in a series of reactions to this rapid development that, arguably, set the stage for the development of the ATT. Preceding the above mentioned panel was a 1995 report by the UN secretary general where the new patterns of conflicts that were described in the last chapter,49 including the use and spread of SALW, were acknowledged. It was concluded that the spread of SALW had gone beyond state power to control; that it had given free rein to criminals and

45

United Nations General Assembly 1997, A/52/298, paragraph 26

46

Ibid, paragraph 25

47

United Nations General Assembly A/52/298 27, 1997, part II, article14

48

Ibid, paragraph 18

49

consequently a reason for citizens to acquire arms themselves in turn in order to defend themselves; and finally that regional solutions were the only way to effectively tackle the problem.50 The problem as described here, with a breakdown of government authority and citizens having to provide for their own security while the state is awash with weapons, has been identified as precisely the conditions leading to a feedback loop of worsening insecurity that causes an intrastate SD.51

SALW transfers made a further dramatic increase during the early 2000‟s - growing by around 28% between 2000-2006 to a total figure of 1.44 billion USD in 2006, and with a large gap in data resulting from under-reporting and the illicit trade, the figure was probably higher by factors of millions or even billions.52 The illicit trade alone has been estimated at 55% of the total trade in SALW.53 Today, SALW armaments are the only weapon system used in around 90% of all conflicts, and are the attributed to account for 30-90% of the civilian casualties.54

Ammunition is a choke-point for the illegal trade, since no matter the amounts of illegal arms there is, to be of any use they need to be supplied by large amounts of ammunition. The ammunition will usually need to be mass-produced using high precision tools, which means that ammunition supplies most often comes from industrial arms producing countries, often outside of the region in which they will eventually be used (as already mention, up to 80% of the arms production takes place in the Security Council states). It has been argued that monitoring this trade could provide early warning of dangerous arms accumulations and the risk of impending conflict.55

To counter-weigh these arguments, it should be said that although SALW can be an important exacerbating factor of conflicts, it is not necessarily the cause of conflict. Countries such as the US, Switzerland and Finland are heavily stacked with weapons, placing them in the top five of highest per capita civilian gun ownership in the world,56 while also being amongst the 50 Ibid, paragraph 63 51 Bourne 2005, p. 156 52

Small Arms Survey 2009, p. 52

53 Hill 2004, p. 5 54 Bourne 2005, p. 155 55 Laurance 1999, p. 190, 191 56

Finland and Switzerland has approximately 45 guns per hundred citizens, while the US tops the list at 89. Small Arms Survey 2011, p. 2

most internally stable countries in the world (as opposed to „fragile states‟).57

Echoing this fact, the aforementioned United Nations Panel on Small Arms nonetheless concluded that:58

“While not by themselves causing the conflicts in which they are used, the proliferation of small arms and light weapons affects the intensity and duration of violence and encourages militancy rather than a peaceful resolution of unsettled differences. Perhaps most grievously, we see a vicious circle in which insecurity leads to a higher demand for weapons, which itself breed still greater insecurity, and so on.”

This statement is a good summary of the problems posed by SALW in conflict situations, and how its proliferation leads to the “vicious circle” of insecurity which the SD describes. One can hardly overstate the importance placed on SALW by the panel, stating that: “...virtually

every part of the United Nations system is dealing with the direct and indirect consequences of recent armed conflicts fought mostly with small arms and light weapons.”59

57

See eg.: The Center for Systemic Peace 2011, p. 34, 35

58

United Nations General Assembly 1997: foreword by the Secretary General

59

3. Methodological Framework

3.1 Choice of method

The objective of this study is to explore and evaluate the possible effects of a single particular program (the ATT), it therefore seems adequate to conduct a case study. To this aim, I will need to study the ATT text, and to position the ATT within the theoretical and historical context. The ATT text serves as the empirical basis for analysis. In analysing the text I am studying the three main categories outlined in section 2.2, and how the provisions they contain relate to this thesis. This evaluation is done based on the findings presented in the background and theory sections, which I will refer back to throughout the analysis. Because some of the effects described by regime theory and international law involve a more long term perspective, which requires a different discussion from the rest of the analysis, I have for reasons of simplicity divided the analysis into two sections: direct and indirect effects. These will be further explained in section 5.1.

3.2 Ontological and epistemological discussion

Interpretivism (or: constructivism) is a term used as a contrasting epistemology to positivism, often referred to by social scientists critical of a positivist approach to human behaviour. Interpretivists contend that an explanation of human behaviour and a focus on the forces that brought about that behaviour - the positivist approach - is inadequate because it fails to address to meanings that are attributed to and influence human behaviour, and that one must instead seek an understanding of human behaviour by interpreting the world from their own point of view.60 The general positivist approach of studying things “as they are” in an „objective‟ sense, should in this context be distinguished from the branch of legal positivism. Legal positivism asserts that, rather than study the law as it should be (in juridical terms: de

60

lege ferenda), one should study the law „as it is‟ (de lege lata). In this view, any description

of law must reflect the social practises that make up the law.61 As opposed to this approach, the „process school‟ sees international law as not only based on past legislation, but as an on-going process which involves considerations of both past and present affairs as well as future goals.62 In terms familiar to the social sciences, the process school is thus more akin to subjectivism, while the positivist school is more identifiable with objectivist views. Since the ATT is still very much in development, I view it as necessary to take a process oriented approach, if not only for practical reasons. The development of the ATT will be to a large extent influenced by how states and others interpret and put it to use, it is therefore a process in a very real sense as well as in a legal one. It is probable that this was what the above mentioned speaker was alluding to by saying that “...the hard work starts now”. This speaker, who is urging for a strong treaty (i.e. interpreting and enforcing its obligations as rigorously as possible), and others who have different goals, are aware that law is constantly evolving and that present circumstances will determine the direction of this development.

3.3 Case Study

For this thesis, the goal of using the case study approach is to explore how the ATT could potentially address a number of identified issues. To this end I rely on background information from previous research and theory to contextualize the ATT, followed finally by a content analysis of the ATT informed by theory and background to draw conclusions.

Because of its recent adoption there are for obvious reasons no cases where the ATT can be studied „in operation‟ - in other words the program effects are in the future and therefore unknown, and in an empirical sense one could argue that they are in fact unknowable. Since these effects are the subject of the investigation, choosing a proper case study design/type can pose problems, since most designs are addressed at investigating present or historical cases. However, by comparing issues where arms control measures have been identified as having effects, with the contents and function of the ATT, it is possible to draw some conclusions to what impact the ATT can have on the identified issues. Also, since the ATT has a carefully defined program „plan‟ (the treaty text) where specific issues, provisions, objectives, instruments etc. are outlined, one can immediately draw a number of conclusions as to its

61

Çali 2010, p. 74

62

effects. For example: contrary to the wishes of many state groups, there are no provisions in the treaty that prohibits arms transfers to non-state actors - one can therefore reasonably conclude that the ATT will not directly prevent such transfers from continuing to take place. To judge the effects of the ATT therefore, it is crucial to study the treaty text - consequently a content analysis of the treaty will be the primary mode of data collection.

This thesis is a single case study, where I intend to provide a descriptive account, with exploratory elements - to use in Yin‟s terminology; or an „intrinsic case study‟ in Creswell‟s terminology. 63 The reasons for choosing this approach are that the aforementioned importance of the context, as well as the novelty of the case requires an extensive descriptive account - this makes the description both a precondition and an end in itself. Also because of its novel, and to some extent unexplored nature, the case is interesting from an exploratory point of view. This is also necessary in order to meet the aims and answer the questions of this thesis.

Common criticisms against case studies are that they lack scientific rigor and easily let biased views influence results; lack basis for scientific generalization; and are impracticable and lengthy. To avoid these pitfalls, it is important to maintain an orderly procedure and to report evidence fairly. Considering the generalizability of the study, case studies must only venture to generalize theoretical propositions, not to make „statistical‟ generalizations about the outside world.64 Because of the nature of this study, it is easy to slip into all too far-reaching speculations or generalizations - so the danger of biased views is especially relevant for this study. In order to give a fair account of the ATT, it is important to stress that the study investigates how the treaty could operate - given the contents of the treaty text, previous experiences etc., - but also to point to evidence against such predictions, and stress that future developments are still uncertain.

3.4 Content Analysis

A useful procedure to go about a content analysis is to use the following steps:65 First, identifying your research material and what parts are relevant to answer you research 63 Creswell 2013, p. 99, 100 64 Yin 2009, p.14-16 65

Adopted from: Mayring, P (2000), “Qualitative Content Analysis” Read in: Flick 2009, p.323, 324

questions; second, analyse how the data was created (by whom, how, where does it come from?); third, characterize how the material was documented (was there transcription involved etc.?); fourth, the researcher specifies the direction of the analysis, research questions, and what one wants to interpret from the text; fifth, the researcher identifies analytical units - “coding unit” defines what is the smallest element of the text which may fall under a category while the “contextual unit” defines the largest, finally the “analytical unit” defines which passages are analysed. Next the researcher may want to summarize and narrow down the text - reducing it down to the essentials, and generalizing its core contents.66

These steps are intended to be addressed in the background section (section 2.2). As mentioned, I will also strive as far as possible to refer directly to the ATT text that is annexed to this thesis so that any conclusions I draw from the text can be easily reviewed by the reader.

The analysis of documents has some strength, since documents are generally: stable i.e. they can be reviewed repeatedly; unobtrusive - not created as a result of the case study; and finally, exact. A weakness of the document analysis is that there is sometimes a bias by the researcher in selecting which documents to study.67 I do not consider selection bias to be a much relevant issue for this study, since the contents of the ATT are contained in a single document (the treaty text). This is the unequivocal primary source of the analysis. There is however other documents connected to the ATT from other UN sources, such as other treaties, meeting procedures, statements from states and other officials, earlier draft decisions of the treaty etc. that could be of use either for their own sake, or for developing the context of the ATT. Also an important source for the interpretation of the treaty is the theoretical framework and background used to inform this study. Together these form the secondary sources of the thesis. 66 Flick 2009, 325 67 Yin 2009, p. 102

4. Theoretical Framework

4.1 Choice of theory

Even though studies in arms control and of related subjects abound, there have been surprisingly few attempts to construct a „general theory‟ of arms control - in fact no such fully developed theoretical framework can be said to have been devised.68 Studies of arms control come from a number of different disciplines, most notably: international law, international relations as well as peace and conflict studies. For the purposes of this study, I will use the Security Dilemma (familiar to peace and conflict studies as well as international relations) to describe the effects of arms flows, and their destabilizing and conflict inducing consequences, creating mutual fear and antagonism between groups. I choose SD theory because two of its key factors are arms and the anarchic context. These two factors are also crucial in intrastate conflicts, where the failing, anarchic state context and the access to SALW play crucial parts. Since arms are a central factor in the SD, arms control measures can be seen as an ameliorating factor or even a possible solution to the SD.69 Another such ameliorating factor described by SD theorists is the effects of institutions and norms such as the arms control regime in reducing the mutual antagonism created by the SD and creating options for cooperation instead of competition in the anarchic context.70 In order to explain this further, I will use Regime Theory which describes how such cooperative structures develop and operate, and which treats arms control initiatives as an important case in point. Finally I will use international law as a crucial tool to interpret how the ATT‟s legal provisions will operate, and to describe how the international legal system can enforce the objectives of the treaty.

68

For an enlarged discussion of this, and a history of theoretical approaches to arms control, see: Morgan 2012, chapter 3

69

See: Croft 1996, p.14

70

These concepts will all be developed further in this chapter. The purpose of the previous comparison is showing the interrelatedness of the two theoretical frameworks used in this study. Again, one can categorize the security dilemma as describing the problems and effects caused by arms, while regime theory and international law describes how to reach solutions to some of these problems.

4.2 The Security Dilemma

The SD describes a relationship between two or more actors (e.g. states) where a mutual mistrust and fear of each other‟s military motives may exacerbate or even cause a state of military tension which may escalate into conflict. The term „security dilemma‟ was first described by John Hertz and Herbert Butterfield in 1951, but the term describes a phenomena that they both argue influence all human relations: a deep-seated uncertainty and fear of others intentions caused by the essential insecurity of human nature, that in the worst case may lead to a logic of „kill first or risk being killed‟ - leading two parties to try to pre-empt each other even though both parties did not harbour any harmful intentions to begin with.71 This may appear to place the SD theory squarely in with a hard-nosed realist school, presenting a somewhat bleak view of human nature, as if straight from Hobbes.72 But the SD does not arise out of purely realist conceptions: it is caused by a tragic combination of a desire growing out of uncertainty for actors to prepare for the worst, coupled with a failure to realize how threatening their own security measures appear to others around them. This phenomenon is described by Booth and Wheeler as the „Security Paradox‟, where a concern for one‟s own security leads to an overall decrease in security.73

Ken Booth and Nicholas J. Wheeler, who present one of the most developed and up to date accounts of the SD, considers that the desire to prepare for the worst case scenario grows out of an „unresolvable uncertainty‟ - a sense that no actor can be completely certain about the current and future motives and intentions of those that might harm them, even of friends and allies.74

71

Roe 1999, p. 183, 184

72

Briefly summarized - Hobbes imagined the human condition and society as dominated by a concern for one‟s own security, often at violent odds with that of other people or societies. This for Hobbes entailed that human interaction would also be dominated by fear. For a longer discussion of Hobbes ideas and how they relate to the Security Dilemma, see: Roe 1999, p. 185

73

Sec studies, p. 142

74

4.2.1 Arms and Arms races

Uncertainty is therefore at the heart of the SD. Booth and Wheeler defines the SD as consisting of two interrelated dilemmas: the „dilemma of interpretation‟ - knowing whether the other‟s motives are defensive or offensive; and the aspect of response - how one should respond to the other‟s actions.75

The fundamental uncertainty in interpreting the intentions of others military development and political posturing leads to a state of insecurity which motivates one actor to increase its security (e.g. by acquiring more arms) - but this security poses an increased threat for others, leading them to increase their security in turn, and so on. This becomes a feedback-loop of action-reaction which Robert Jervis (another influential figure in SD theory) calls a ‘spiral model’, something which is easily identified in arms races where one or more groups tries to keep a steady pace with or up-ante their rival‟s increasing arms arsenals in order to maintain the same level of security.76 This mutually aggravating process is driven by the fear that the rival‟s military power will out-balance one‟s own, this threat is aggravated further by perceived grievances and hostilities. In an intrastate conflict, a disintegrating state and ethnic rivalries may exacerbate the situation further and motivate groups to take advantage of other groups‟ relative weakness and to fill the vacuum left by the state.77

Even though military capability and arms are often euphemistically termed „defensive‟, all weapons have the potential of being used for offensive purposes, and so defensive actions are almost indistinguishable from aggressive ones. This leads Jervis to define the SD as “these

unintended and undesired consequences of actions meant to be defensive”.78 Despite the unintended signals and consequences they may provoke, arms can be intended for many different purposes other than direct violence:

States will arm themselves either to seek security against the threats posed by others or increase their power to achieve political objectives against the interests of others. Military power can be used to achieve objectives through use of force, implicit and explicit threats, or symbolism”.79 75 Booth; Wheeler, p. 139 76 Roe 1999, p. 186 77 Jeong 2008, p.138, 139 78 Tang 2009, p. 591 79 Buzan, Herring 1998, p. 83

Arms can therefore be thought of as a kind of „power currency‟, making them attractive to acquire for a number of reasons, and making it a key component of the SD.

4.2.2 Anarchic Structures and the Security Dilemma

An underlying cause of the uncertainty and insecurity central to the SD, is for many writers the notion of an anarchic state structure. Anarchy is sometimes viewed as the cause or a necessary condition of the SD, since it encourages the uncertainty, insecurity and self-help behaviour that forms a kind of breeding ground for the SD predicament.80 In the completely unmitigated, or „worst case‟, anarchic structure associated with Hobbes81

and certain realists - put bluntly - the lack of a higher authority to govern the behaviour of states puts them in a precarious situation where they can never fully rely on anyone but themselves for security and are so essentially dependent on self-help. Such a structure promotes uncertainty and insecurity, and motivates states to assume the worst case scenario with regards to others‟ intentions.82

Few scholars, however, would subscribe to a definition of anarchy quite as unbending or fatalistic as the one just provided. Even if they may accept such conditions as applying to

complete anarchy, most scholars would consider that anarchy can be, and is, overcome to

different extents. Either by imposing overarching structures such as international law and the UN in the liberal tradition, or by the dominance of a hegemon in the realist tradition - anarchy, and consequently the SD, can be mitigated.83

4.2.3 The Security Dilemma in Intrastate Conflicts

The SD was traditionally used mainly to explain arms races and conflicts between states, like the great power struggles of the cold war. But the theory has lately been applied to intrastate conflicts as well. Stephen M. Hill cites Barry Posen as the first scholar to draw attention to how the SD can operate in intrastate conflicts. Posen argues that as anarchy promotes SD

80

Roe 1999, p. 186

81

Briefly summarized - Hobbes influential idea of anarchy was that it would be characterized by what he famously phrased as a “War of all against all”. The only way to avoid this predicament for Hobbes, was by installing a strong overarching structure, or “Sovereign”, with a clear monopoly on violence. On the local level, this meant the presence of a strong state. But since no such “sovereign” exists on the international level, the society of states would be in violent anarchy. For a developed discussion on how this relates to the security dilemma, see: Wendt 2008

82

Roe 1999, p. 186

83