Africans! “Our destiny is largely in our hands. If we find, we shall have to seek. If we succeed in the race of life it must be by our own energies and our own exertions. Others may clear the road but we must go forward, or be left behind in the race of life. If we remain poor and dependent, the riches of other men will

not avail us. If we are ignorant, the intelligence of other men will do but little for us. If we are foolish, the wisdom of other men will not guide us. If we are wasteful of time and money, the economy of other men

will only make our destitution the more disgraceful and hurtful”.

1

INTRODUCTION:

The Problem, And The Theoretical Framework

“The Third World is not a reality but an ideology.” Hannah Arendt

AFRICA

, – “the Jungle,” “the Dark Continent,” “the underdeveloped,” “the developing,” “the poor,” “the undeveloped,” “the Wretched of the Earth,” “the white man’s burden” (Schreader, 2000: 94). These are some of the most popular appellations of the Continent that remains the question mark on the globe. Quel dommage!To the European, and maybe until only yesteryear the history of Africa began with David Livingstone, just as that of America began with Christopher Columbus.

Historians have long observed the changes in human existence and have labelled it ”Revolution.” They, like Victor Hugo, believe that revolution is the larva of civilization.

The theme of this essay, in retrospective, is “the Revolution that was not”, and the obvious implication is a bit unsavoury. History is passing Africa by. Africa is the last continent of the “Third World” to come to independence. She is the deepest sunk in political and socio-economic backwardness. She has the most appalling problems and yet revels in the most effusive optimism. If anything, to my best knowledge, for the most part she is wallowing in an endless web of misery and despair. It is a continent of mass poverty but the obsession of the ruling groups is with luxuries and/or petit power plays. The leaders who came to power mouthing the rhetoric of change faced the critical poverty of their countries with frivolity and fickleness (First, 1972: 9). Those who are convinced that the Africans are unfit to rule themselves, that the empire opted out of Africa too quickly and that the continent was bound to go back into decline after the premature granting of independence, only succeeded in muddling the issue. The colonial era was a period of swindle and cupidity and these, any theory of conspiracy will reveal to the enquiring discerning eye.

In Marxian analysis, the Great Depression of 1929 should have triggered a war of liberation for the colonised people everywhere. When the opportunity was aborted, however, the imperialists

decided not to be caught napping, especially not in the shadow of their Nemesis, Communism. They decided to disengage coolly, and cunningly transferred power to stooges and collaborators who were to perpetuate the horrors and depredations of their masters.

It is not only fitting but also therapeutic to give African politics a FRANK and PITILESS analysis. Such an analysis will help us understand the position and behaviour of African countries in International Relations. Are they pretending in the international arena, or are they wholly integrated into it? For the purpose of analysis, the institutions and instruments of government the Imperialists handed their colonies at independence, defies description, from the point of view of constitutional history. The net effect was the creation of little ”de Gaules,” little ”King Leopolds” and the replicas of Westminster on a continent as ravaged as its mosaic appearance would allow. The supposition that the colonial period was a period of tutelage of barbarous Africans by the ’civilised’ West is highly flawed and objectionable. It is an uncomfortable naiveté. The haste with which the imperialists engaged and disengaged belies this assertion. In the words of Sir Andrew Cohen, a former colonial governor and former head of the British Colonial Office, the debauchery was planned and expedited out of premonitions of a debacle. ”Britain needed a new colonial policy for Africa. She should recognize that successful cooperation with nationalism was the greatest bulwark against Communism. The transfer of colonial power need not be a defeat but a strengthening of the Commonwealth and the Free World” (First, 1972:42).

1.1. COMMENTS ON METHODOLOGY

This thesis will proceed within the framework of a redefinition and challenging of theories and assumptions in view of the dyadic nature of the analysis. The key questions that guides this study can be grouped under five main headings:

1) Socio-political modernization and socio-political decay. Is Modernization a Westernization process? (This formulation of the empirical problem is coeval with the belief of the notion or law of inevitable progress).

2) The traditional web of social existence and societal order.

a) What kind traditional institutions existed in pre-colonial Africa? b) What was the authority and legitimacy of the institutions?

c) Was there democracy and accountability in Traditional African societies? 3) How did the traditional institutions changed under the impact of Colonialism?

4) The transfer of power in colonial Africa – how was power transferred from the British colonial governors to African elites?

This analysis is crucial if the dilemma of African “independence” and the problems that came with it can be discussed honestly. The situation is parallel to a case of Hamlet without the Prince -- a farcical drama.

The chosen case study is Ghana (the old name ‘Gold Coast’ is used interchangeably) and the reasons for the choice are manifold. The choice of the case study is influenced largely by the following reasons:

1) The socio-political history of Ghana, especially its relationship with Europe, which spans a period of over five centuries. Its unique historical experience affords a clear insight into the dynamics of modernization.

2) The plethora of secondary sources – based on the fact that Ghana is the first country that achieved independence – at least in a formal sense -- in sub-Saharan Africa.

3) Finally, the fact that I am an African (though not a Ghanaian) and thus partially familiar with the African political and social phenomena which I aspire to understand and explain.

This paper is not by any means exhaustive, and for obvious reasons its many drawbacks are unavoidable, and therefore it may be found wanting in some respects. In many respects, it is a relative exercise in contemporary history of Africa, yet there is no distinct systematic chronological basis for such an exercise. A further shortcoming is the use of secondary materials for the case study. Here again this cannot be held to be a weakness in view of the lack of proximity to the primary sources. However, in the main, it offers multiple critiques of the many conceptualizations from economic determinism to historical realism. Thus it is a modest effort to reconstruct a conceptual framework for the analysis of politics in the mal-developed area—sub-Saharan Africa. The chosen method in this thesis is comparative, descriptive, analytical and argumentative.

Finally, I write this thesis not to nag nor to whine, but to prod. Thus, I am keenly aware of many repetitions throughout the work, unavoidable because of comparative methods used, and others for emphasis – which may have turned out to seem over-emphasis. I am hopeful that this humble effort would contribute to some illumination of the problems of socio-economic and political modernization in this part of the “Third World”.

1.2. TOWARDS A CRITIQUE OF THE ALTERNATIVE APPROACHES

“Third World” politics presents the discipline of international relations, and even the international relation scholars for that matter, with a great challenge -- a challenge that, according to Professor Riggs (1967:317), ”we are indeed only numbly beginning to appreciate.” These challenges and problems, it is hoped, may some day lead to a restructuring of the whole discipline.

In so far as political theories and ideologies – that is, an orientation that characterizes the thinking of a group or nation -- are concerned, there are none. Only a barrage of speculations and hypothesis has been advanced. Apter (1967:viii) puts it aptly: but ”the events are confusing. Our research ideas are similarly untidy. Quite often we are as much imprisoned in our concepts as the political leader is in his rhetoric.”

The trend then, for all international relations scholars (particularly those interested in African politics) is to tread cautiously and to avoid overzealous generalizations. As the most quoted scholar in African Studies, Thomas Hodgkins (Apter, 1967:viii) poignantly puts it,

our profound ignorance of African History, our lack of comprehension of African attitudes to the contemporary situation, our remoteness from the ideas of revolutionary democracy, the distortions in thinking produced by the colonial mythology--- these, I would suggest, are good reasons for doubting whether we are likely to have any sensible contributions to make to a discussion of the direction of social

and political change in post-colonial Africa. Such questions are best left to the Africans.

Touche! Dr. Harris, in the preface of his book ’Studies in African Politics, 1970, seemed to have

concurred with this view, as he remarked, ”seen through a number of diverse topics, Africa’s problems can best be understood, if not solved, in African terms without reference to norms and conceptions derived from other sources.”

For an African analyst however, these prospects are not reassuring: Schooled in Western norms and concepts, he can but grope in the dark in the dearth of Western political theories and ideologies to guide him.

An interesting problem one encounters in utilizing some models of political analysis is the unsavoury discovery that in Africa politics is not policy-making. Political power is equated with acquisitive power. When for instance the ”Elite model” is used, the answer to the question, ”who has power?” or ”Who rules?” appears anomalous. Power lies without rather than within the country. It is sad.

The grotesque nature of the situation is not only unnerving but also irksome. Jean-Paul Sartre (Fanon, 1971:7), gives some relief though when he said:

…the European elite undertook to manufacture a native elite. They picked out promising adolescents; they branded them, as with red-hot iron with the principles of Western culture; they stuffed their mouths full

with high-sounding phrases, grand glutinous words that stuck to teeth. After a short stay in the mother country they were sent home whitewashed. These walking lies had nothing left to say to their brothers; they only echoed. From Paris, from London, from Amsterdam we would utter the words, Parthenon! Brotherhood! And somewhere in Africa or Asia, lips would open…thenon!!…therhood! It was the Golden

Era.

Of late, however, efforts have been made towards a normative approach to the political problems in developing areas and it is to these approaches I owe a debt of gratitude. The first approach is reflected in Kenneth Organski’s book, ”Stages of Political Development.” He fails to provide a theory of stages in political development. He is rather concerned with a set of problems (crises) faced by developing countries (Riggs, 1967:33). These problems are mostly socio-economic and they are preferred to any other, for, like Marx (1913:11-12) said: ”It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence but on the contrary, it is their social existences which determines their consciousness.”

Organski reached the conclusion that there are essentially four stages of development: 1) political unification,

2) industrialization, 3) national welfare, and 4) abundance.

During the first stages, national governments gain effective political and administrative control over their populations and territories. Without such control, all policies designed to encourage economic growth through industrialization are bound to fail (Riggs, 1967:332). However, the Organski model is not without its shortcomings. The first stage of political unification (described by Lucien Pye as the crises of identity, legitimacy and penetration) is said to have been achieved by pre-modern European societies but that non-Western societies are still struggling with this stage of development. What is not pronounced is the historical evidence (like the one given for the second stage--industrialization), of the means utilized in achieving these ends. A glaring obfuscation of such genre is an indictment of the entire model, and for that matter all approaches in the Development Theory are equally blighted.

What they succeeded in blurring is the relevance of the means, and when, especially in this instance, it is the hub of the problem. The task of political unification demands a totality of efforts if “stability” and “orderly” change is intended. Hence the need for a totalitarian ideology. In retrospect, the Western bourgeois system, and for that matter any other system that ever succeeded in scaling this hurdle, did so only under the aegis of an ideology as totalitarian as it was mobilizing in kind. Where else can one put the import of the eerie Catholic Inquisition in the achievement of unanimity in pre-modern Europe? Or can it be argued that Augustinian theology, Lutheranism, Calvinism and later Puritanism, appearing in various phases of cultural changes in the West, were all totalitarian in content and scope, their other-worldly-outlook notwithstanding? The emphasis on ”westernization” in the non-Western world, therefore, becomes a byword for a superimposition of culture. For, what inheres in this blatant and inveterate phenomenon is nothing short of the foisting of alien cultural practices on a people with a totally different cultural and historical background. In the main, this cultural superimposition is considered innocuous, yet its impact is so grotesquely repugnant to even the naive observer. It is the onus of the ”political decay” immanent in the “Third World.” Is not the index of politics in these areas the quintessence of cupidity of political actors?

If we are to understand Western democracy as a response to the challenges of the allocation problem (in tandem with the peculiarities of Western European circumstances), tallying with the third and fourth stages of national welfare and abundance in Organski’s model, then its superimposition on non-European cultures is deviously anachronistic. Thus, is not the nauseating pre-emption of the scarce resources in the “Third World” by political actors, in itself a distribution process of a sort? It is indeed the acme of the westernization process.

However, in hindsight, when the dynamics of modernization are viewed as ”technological” change rather than ”cultural”, the cross-cultural transmission of the Industrial Revolution is given wings. It is in this sense that Lenin’s contribution to Scientific Socialism becomes monolithic. The paradox thus expressed elsewhere that “modernization can thus be seen as something apart from industrialization—caused by it in the West but causing it in other areas,” is as abstruse as it is hollow. Almost invariably, the tragedy of cultural superimposition, in the exogenous change process, is illustrated vividly by the case study, Ghana. In the absence of a highly disciplined revolutionary party, committed to the initial tasks of political unity, unification and ceaseless participation, political action assumed the shape of a sordid debauchery. Flung down the gauntlet the nationalist party all but withered overnight.

During the second stage of economic development, i.e., the industrial revolution, governments have to make possible the accumulation of capital, which can only be done at great social cost.

Organski believes that historically speaking, three different patterns of government have proven successful in solving the problems of industrialization: the bourgeois (that is, Western Democracy), the Stalinist (Communism), and the Syncratic (Fascists) (Riggs, 1967:33).

This view is upheld by Professor Pares, who said: ”If they (the liberated peoples) insist on building their own capital the hard way, like the Russians, they will certainly have to resort to dictatorship—perhaps Communist dictatorship—since no other form of government can easily oblige the peasant and the worker to tighten his belt for the sake of the future” (Harris, 1970).

Pye’s approach tallies with Organski’s, especially the first stage of unification, namely, the crises of identity, legitimacy and penetration (Riggs, 1967:333).

In any case, however, it is David Apter’s complex but intriguing theory of stages and alternative paths of political development in the larger framework of modernization that provided the beacon light for this analysis.

The net effect is the eclecticism permeating the paper. The pre-occupation with a critique of theories is due to the cue from Samuel Huntington’s essay on ”Political Development and Political Decay”. In it he argued that what is going on today in the third word should frequently be characterized as a process of decay rather than of development (Riggs, 1967:334).

2

ON MODERNITY AND SOCIAL PROGRESS “You are born modern, you do not become so.”

Jean Baudrillard ”Modernism may be seen as an attempt to reconstruct the world in the absence of God.” Bryan Appleyard

This chapter is based on the rejection of the view that all human societies everywhere had to develop (if they have to develop at all) through the same or similar series of developmental stages. In order to put the problem of inevitable progress (social evolution) in the right perspective, and in order to assail its ubiquitous biologism, we shall make a passing remark on the “vogue of Evolution.” We shall turn to that turbulent period in Western Europe, which is referred to as the “Withdrawal of Philosophy.” My reason is very simple: the withdrawal of philosophy led to a form of rationalization or an attempt to explain and justify imperialist expansion. Imperialism marked the beginning of the process of rationalization of non-hierarchical African structures since there was growth on human knowledge in African societies. However the shared system which imperialism brought presupposes a symbiosis in which growth without development is the only thing possible and conceivable. The obvious implication then is that imperialism is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for human progress.

2.1 THE LEGACY

Philosophy in the 19th century was not able to resolve the conflict of competing relativities or to

provide absolute standards. Its withdrawal from the traditional business of providing comprehensive metaphysical ontologies left the particular branches of science philosophically on their own (Brecht, 1970: 189-190). Hegel, – in weird premonition – dubbed himself as the last philosopher. In this, Hegel was right that he could know if what we mean by philosopher is a producer of metaphysical systems. When Hegel gave up the ghost, the fervour for such creations seemed to have been spent for good. The decisive reason for this sudden decline was not the towering greatness of Hegel’s philosophy, or that of his predecessors, but the growing awareness of the scientific weakness of all metaphysics. The exacting demands put on scientific inquiries operated as a deterrent to metaphysical speculations. That science was on able to prove the

existence of God solely by scientific means was becoming a scientific commonplace. This led into a formidable move of historical dialectic, to two extreme alternative doctrines, the one personified by Sören Kierkegaard, who called for “jump into faith” out of the scientifically unsolvable dilemma; the other by Friedrich Nietzsche, who declared that “God is Dead.” Caught between these extremes, scientists turned to empirical research with growing success (Brecht, 1970:189-190).

The ‘unsolvable dilemma’ began as pangs of guilt. The issue was not the existence of God, but the stern disapprobation of an ethical system believed to be imposed upon society by God. Thus the need to reject the foundations of the ethical systems was imperative. The “jump into faith” and “God is Dead” doctrines proved inadequate for this task – for, lo, both doctrines implied a tacit acceptance of the ethical system. The demolition of the ethical foundations must of necessity be thorough. To jump into faith is to relent, and to postulate that God is dead is to affirm that He was there before, (which none can prove anyway). Thus to conclude that He is not there, in fact, he has never been there at all affords a greater relief from the dilemma.

Darwin and the concept of ethical neutrality provided the facility to solve the dilemma. His “On the Origins of Species By Means of Natural Selection” played a role in this development. It led to a distinction between religious or metaphysical doctrines and strictly scientific enquiries. The primary subject of the ensuing controversies were geological history, the origin of man and divine intervention; not ethical questions (ibid, 191). Darwin’s opponent spoke of “doctrinal moralism” – meaning that science should take moral consequences of their theories into account (ibid).

For the emotional attitude of evolutionalists, we turn to C .H. Waddington (Popper, 1974:106-107), who cautioned: we must accept the direction of evolution as good simply because it is good.” Professor Bernal (ibid) also stated: “it was not … that science had to fight an external enemy, the Church; it was that the Church … was within the scientists themselves.”

This intense emotional attitude crystallizes itself in the theory of inevitable progress. The logic is very simple: With the violent rejection of the imposed norms (the ethical system in which God is held to be the almighty arbiter) what was left was the original system of values, and this provided the basis for the frenetic and ingenious conjecturing on the nature and origins of human society. Stemming from this biologism is the view that the masses should be ruled by the intelligent (Brown, 1964:15). Thus the need to change the value of human existence.

In the study of the Greek Tragedy, Fredrich Nietzsche, in his book “The Birth of Tragedy,” discusses two diametrical opposed ways of arriving at the values of existence – the Dionysian and the Apollonian.

The Dionysian pursue them through the ‘annihilation of the ordinary bonds and limits of existence;” he seeks to obtain in his most valued moments escape from boundaries imposed upon him by his five senses, to break through into another order of experience. The desire of the Dionysian, in personal experience and in ritual, is to pass through it towards a certain psychological state, to achieve excess. The closest analogy to the emotions he sees is drunkenness, and he values the illumination of frenzy. He believes that “the path of excess leads to the place of wisdom.” The closest analogy to this kind of social existence can be found in modern societies.

The Apollonian distrusts all this, and has often little idea of the nature of such experiences. He finds means to outlaw them from his conscious life. He knows but one law, measure in the Hellenic sense. He keeps the middle of the road, stays within the known map, and does not meddle with disruptive psychological states. Apollonian way of life implies the distrust of individualism. The known map, the middle of the road, to the Apollonian, is embodied in the common traditions of his people. To stay within it is to commit himself to precedent, to tradition. Therefore, those influences that are powerful against tradition are uncongenial and minimized in their institutions, and the greatest of these is individualism and discord. It is disruptive, even when it refines upon and enlarges the tradition itself (Benedict, 1968:56-57). The near parallel to this kind of social structure is in traditional societies.

Nietzsche says, “Wherever the Dionysian prevailed, the Apollonian was checked and destroyed ... wherever the first Dionysian onslaught was successfully withstood, the authority and majesty of the Delphic god [Apollo] exhibited itself as more rigid and menacing than ever.” Yet neither side ever prevails due to each containing the other in an eternal, natural check, or balance.

The essential difference between these two types of social structures is not their value systems (quite distinct from each other, anyway), but rather, it is the absence of the essential element in one, and its stagnation in the other. This essential element is knowledge, and the mystical entity determining its growth is to be found in the aggressive tendencies in the other. This interplay of forces, then, is the dynamics of social evolution but not of social development and progress. A necessary inference here is that, imperialism -- which is the crystallization of social evolution -- produces growth and not progress and development.

As this thesis commence, we shall henceforth equate the modern-industrialized way of life to the Dionysian way of life, and the traditional way of life to the Apollonian way of life, respectively.

2.2. MODERNIZATION-WESTERNIZATION DEBATE REVISITED

“All truly historical peoples have an idea they must realize, and when they have sufficiently exploited it at home, they export it, in a certain way, by war; they make it tour the world.”

Cousin Victor

Modernization is a global process that all social systems are experiencing. Modernization theory began in the 1950s mainly amongst American development sociologists. It is referred to as “the applied enlightenment” (Pieterse, 2001:42-43). Unlike the evolutionary theory, which conceives human and societal development as being “natural and endogenous,” the modernization theory considers both endogenous and exogenous forces in their development paradigm (ibid, 43). The endogenous changes are: “social stratification, rationalization, the spread of universalism, achievement and specificity,” while the exogenous change are: “the spread of market relations or capitalism, industrialization through technological diffusion, Westernization, nation-building … , state formation (as in postcolonial inheritor states)” (ibid, 43).

Modernization increases levels of asymmetrical interdependence and integration across state frontiers and between different peoples. On the individual, institutional and the group levels, “these changes appear to have the most impact upon elites and leadership groups, [and the masses]” (Evans and Newnham, 1998:336).

MOVEMENT OF SOCIETY

A

B Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 Level 4LEADERSHIP (ELITE) AND MASSES CHASING THE GOALS GOALS

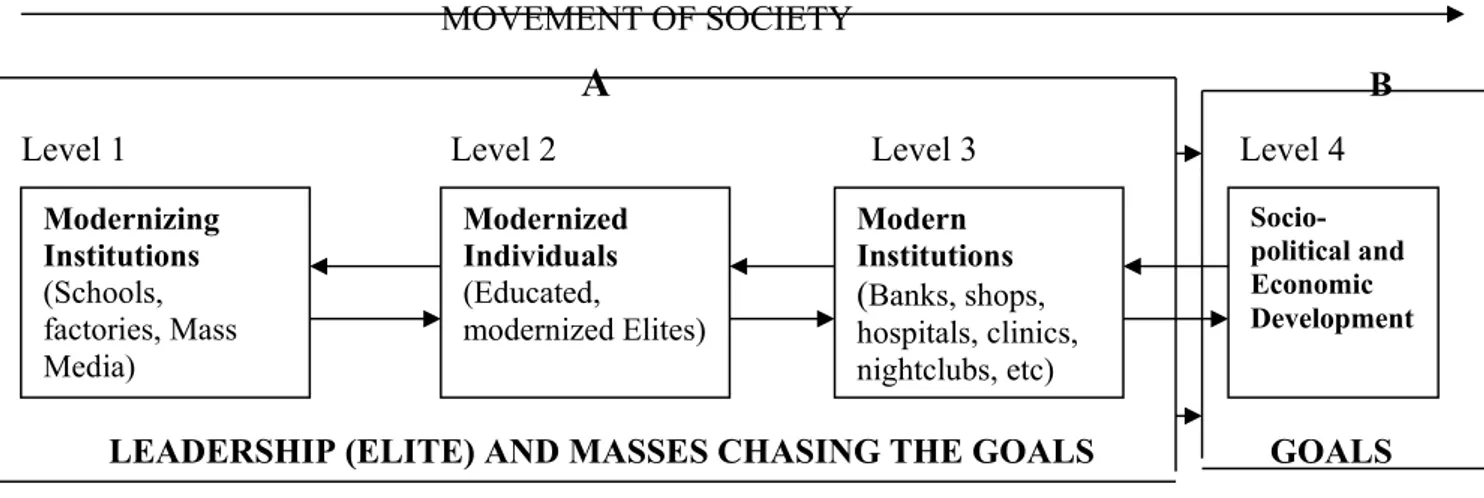

Figure 1. Interplay of the necessary and sufficient Conditions for Modernization. Modernizing Institutions (Schools, factories, Mass Media) Modernized Individuals (Educated, modernized Elites) Modern Institutions (Banks, shops, hospitals, clinics, nightclubs, etc) Socio-political and Economic Development

As figure 1 illustrates, modernizing institutions are necessary but not sufficient conditions for modernization – economic development. To realize economic development as a goal, there must be interplay between all the three levels (1, 2 and 3). The leader must identify his or herself with the masses in order to achieve socio-political and economic development.

Modernizing institutions such as the schools, factories and the mass media create modern individuals -- the educated elites -- who staff the modern institutions (banks, hospitals, clinics, etc) that are necessary for economic growth. Modernizing institutions are prior causers to modernized individuals and modern institutions. As such, traditional individuals must be modernized before they can create and staff modern institutions. The strength of the modernizing institutions should be the most policy-relevant. If a modernizing elite attempts to foster economic development directly by creating modern institutions without first cultivating the necessary human capital (modernized individuals), the modern institutions are likely to be abortive. Modernizing institutions such as the school and the media are typically State sponsored, controlled, and influenced. Political elites may seek to diffuse modern values and attitudes through these institutions in order to prepare the work force for the staffing of modern institutions in the production realm and elsewhere. They may also use these institutions more directly to promote the mobilization of the population in support of national programs of economic development. The reach and influence of modernizing institutions is the starting point in modernizing a society.

The process of modernization therefore, is a universal phenomenon. It is the burden of our age. “It is an objective that is not confined to a single place and region, to a particular country or class, or to a privileged group or people. Modernization, and the desire for it, reaches around the world” (Apter 1967:1). Individuals, institutions and nations are bound to modernize. The right to modernize is therefore God-given and natural, and no man or nation is chosen by God or by nature to determine the direction of modernity of other men and/or nations.

Africa has suffered from the effects of invasions, conquests and migration – such that the very conditions that promote the growth of human knowledge, and the necessary and sufficient conditions that favour this growth of human knowledge, and therefore, of social progress and development, have been bedevilled by the formidable crisis of identity which engulfs the culture, the society and the individual. Any theory of social development or modernization, therefore, must first perforce consider the solution of this crisis as the sin qua non. However theories of modernization do betray a glaring obfuscation of this essential variable, pontificating, instead, on

the virtues of westernization. Empirically, theories of social evolution can be logically indicted for the lack of fit between western imposed structures and traditional African structures, which results in social disintegration.

Aplenty eminent scholars blatantly equate modernization in the non-European world with westernization or Europeanization. This drives us to the pertinent question: Is modernization a westernization (Europeanization) process?

The use of the term ”Westernization” or “Europeanization” to denote the economic, political, social and intellectual transformation of African countries can be logically dismissed. The logic for the dismissal is manifold. Here are two of them: 1) the rising communalistic and solidarity sentiments of the African peoples opposes western individualism and social discord; and 2) westernization’s inadequacy in improving the standards of living of the “westernized” is proven -- “glance at the low estate of the underdeveloped three--quarters of mankind as the imperialist era draws to a close” (Emerson 1960: 7), and the failing African nation-states, illustrates the point. There is no gainsaying the fact that ‘modernization first occurred in the West through the twin process of commercialization and industrialization” (ibid 43), yet simply regarding it as westernization is to commit a faux pas, disdainful enough in these modern days. “Europeans were by no means the pioneers of human civilization. Half of man’s recorded history had passed before anyone in Europe could read or write” (Emerson, 1960: 3). Therefore, to posit that the industrial revolution fostered by the humanistic upsurge of the Renaissance period is wholly European is to commit an intellectual hara-kiri.

What is modernization? What is westernization? The Marxian definition will be preferred in this paper: “modernization, in this view, can be understood as a series of altering material relationships out of which a more abundant and kindlier world will eventually emerge”(Apter 1967:6). Modernization can be seen as something apart from industrialization – caused by it in the West and causing it in other areas (Emerson, 1960: 44). It is a complex process. As a revolution, it predates the Industrial Revolution. Its origins lie beyond the Renaissance since as an innovation process it is as old as man. “Thus, modernization as the process leading to the state of modernity begins when man tries to solve the allocation problem” (ibid 9). It employs “roles that have been drawn from various industrial societies (and ordinarily associated with Western industrial society, although modernization can no longer be claimed as peculiarly Western)” (Emerson 1960: 60). How does one explain away the paradoxes above? Firstly, there is the case

of the cart-before-the-horse-situation that cannot be overlooked. Secondly, modernization is considered to be a relative term. The overtones of racial supremacy and arrogance which the term “westernization,” embodies are based on the notoriously false assumption that, but for the West, the world would not have experienced an industrial revolution.

Westernization, on the other hand, is defined as the “conversion to the ways of Western Civilization.” Europeanization is defined by dictionary.com as “assimilation into European culture,” or “to make European.” Westernization and Europeanization will be used here interchangeably.

Before we proceed, we shall here make a passing remark on the term Western Civilization. Correct me if I am incorrect -- “Europe reads with letters and counts in numbers that come from the crossroad of Africa and Asia. “Civilization”, if anything, “is composite, an accretion of experiences and ideas beyond race or region.”

Professor Palmer (1967:2), describes modernity (the Dionysian way of life) this way:

It is a world characterised by modern science, by modern industry and machines, modern sources of energy, modern transport and communications, modern medicines, sanitation and methods of raising food…. It is a world common men begin to sense the attractions of a higher standard of living, of better

food and housing in return for less laborious and spirit-killing work.

The converse of what is revealed here is the grim reality of Traditional-Apollonian way of life and existence prevalent in the non-European world, particularly Africa. We here come closer to answering the pertinent question, “Is the African village best left alone within its unbroken cake of custom, or should there be a frontal attack upon the superstition, ignorance, infant mortality, hunger, slavery and tribal warfare which are the price it pays for its traditional [Apollonian] existence?” (Emerson1960: 14).

Is Westernization the answer? Obviously not. This is where I anchor my argument, with a cue from Emerson, about the “revolution that was not.” Emerson (1960:18) says:

The inadequacy of the way the task has been done, is vividly illustrated within each of the underdeveloped countries by the disparity which exists between certain segments of their people in terms of acquaintances

familiarity with the west and its ways through education abroad in the imperial centres or in Western established schools and universities.

The process of transformation or conversion that connotes the term westernization consists of the adoption of forms of life and production which were first developed among western European intellectual classes and bourgeoisie in the eighteenth century. These new forms of life, thought and production can be summed up as follows: rationalism, individualism and industrialism. The dynamic forces of westernization undermined, underdeveloped and revolutionalized the intellectual attitude, the social life, and the economic structure of African countries. These new ways of life and production is referred to as modern civilization. It spread from the intellectual classes of the west to African countries and classes. As it penetrated, it destroyed the traditional (Apollonian way of life) structures of African society. This expansion was immanent in its very nature.

The forms of adaptation to western civilization vary from country to country, and from class to class. In African nations, as it were in European nations, all kinds and degrees of transition and fusion, of the traditional and modern, can be observed. The tempo of the transition process depends upon the government: where national governments promote it, it is faster; it is slowest where colonial government unconsciously impede its development. It springs from the blatant misinterpretation of the tendencies of history, from a bias belief that modern civilization is reserved for, or beneficial to, certain races and classes only. Westernization in Africa has failed to encourage change, and individuals, states and regions are regressing into a cul-de-sac of traditionalism. Modernization through westernization, instead of liberating Africans has become a veritable instrument of socio-political and economic blackmail. This treachery sadly belies social change in Africa. The problem of identity begets dialectic in the Hegelian sense:

there was an almost universal tendency within a newly rising leadership to accept the conquering Western civilization as superior and in itself desirable. If the first reaction of the peoples on whom the West imposed itself was generally a xenophobic order, the next phase was likely to be a swing in the direction

of an uncritical self- humiliation, and the acceptance of alien superiority. The third phase…was a nationalist synthesis in which there was an assertion of a community with pride in itself and its past but

still looking, at least as far as its leaders were concerned, in the direction of Westernization and modernization. (Emerson 1960:10-11).

(This will be surveyed under the chapter on ideology). Those leaders were, almost without exception, men who had achieved substantial acquaintance with the West (Emerson, 1962:10-11). The point, however, is made clear: instead of goals and ideas based on futurism, African efforts have been oriented to the past, to a lost Golden Age. The mild and unaccentuated flirtation with modernization that prevails is directed at the duplication of the immense material advance, which characterises the West. Such self-hypnosis is what forms the substance of African politics and society today. It is sad.

The diffusion of western culture has given an unmistakable stamp on Africa traditional structures. Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx clearly foresaw and interpreted this tendency in their 1848 Communist Manifesto:

In place of the old local and national seclusion and self-sufficiency, we have intercourse in every direction, universal inter-dependence of nations. And as in material, so also in intellectual production. The intellectual creations of individual nations become common property. National one-sidedness and

narrow-mindedness become more and more impossible, and from the numerous national and local literatures, there arises a world literature. The bourgeoisie, by the rapid improvement of all instruments of production,

by the immensely facilitated means of communication, draws all, even the most barbarian, nations into civilization. The cheap prices of commodities are the heavy artillery with which it forces the barbarians' intensely obstinate hatred of foreigners to capitulate. It compels all nations, on pain of extinction, to adopt

the bourgeois mode of production; it compels them to introduce what it calls civilization into their midst, i.e., to become bourgeois themselves. In one word, it creates a world after its own image.

Marx and Engel’s prophecy has been fulfilled. It is true: “All truly historical peoples have an idea they must realize, and when they have sufficiently exploited it at home, they export it, in a certain way, by war; they make it tour the world.” The West has proven it by the superimposition of western-imposed cultures on non-western cultures. We find today in all African countries stages of transition similar to those witnessed by Europe in the 19th century – the “growth” of

industrialism, the emergence of the individual from the traditional restraints of family, the “urbanization” of the country-side, the spread of modern education, transformation of religion under the impact of rationalism.

Now, the question is: was such expansionism a unique peculiarity of the West? No, there have been other expansions before. African has known great conquering empires before. Western expansion begun as response to the rise and expansion of the Arab and Turkish civilization. The west was faced with a challenge to its system, so it had to respond. The west was not unique in its expansionist appetite. They merely excelled in their capacity to carry it into practice.

According to the historian Arnold Toynbee's (Marwick 1970:85), all civilizations are faced with a crisis (a challenge), which is either one of ideas, or one of technology. How they respond to the crisis determines whether they will survive or not. An example is the Fall of Rome. Toynbee points out, as we shall discuss below, that the Byzantine Empire (the Eastern Roman Empire) used Christianity to revitalize and reform the Roman Empire for another thousand years.

Toynbee (Marwick 1970:85) remarks:

When civilizations rise and fall and in falling give rise to others some purposeful enterprise, higher than theirs, may all the time be making headway and in a divine plan the learning that comes through the

suffering caused by the failures of civilization may be the sovereign means of progress.

His concepts -- Challenge and Response -- is of special interest here. Their application to the study of history is not only entertaining but also highly rewarding. They afford a rare insight into human affairs.

For an interesting study of a topic in history through the application of these concepts, we shall begin with the Islamic expansion into Europe. I shall endeavour to stick to the bare outlines in a bid to refute the odious premise. We shall regard the Islamic expansion into Europe as the ”challenge” to the European world system of the 17th century A.D. Professor Pirenne reached the

conclusion that a Roman civilization, based on the Mediterranean survived the barbarian invasions, and did not collapse till the Muslim expansion of the 17th century. Medieval

civilization began only with the Carolingians: “without Mohammed, Charlemagne would have been inconcieved!”(Marwick, 1970:63). Charlemagne and the Holy Roman Empire becomes the ”response” and in time, becomes the ”challenge” to the world system. In this vein, the Crusades mark the beginnings of Western imperialism.

Now, lets stop here to recapitulate the situation! What happened when the East met the West? The obvious reason for the chosen debate in history can now be appreciated: The Arabs (East), by virtue of their location and subsequent conquests had become the custodians of human civilization. Palmer (1967:16-17) pulls it:

In mundane matters, the Arabs speedily took over the civilization of the lands they conquered. In the caliphate, as in the Byzantine Empire, the civilization of the ancient world went its way without serious interruption. Huge buildings and magnificent palaces were constructed, ships plied the Mediterranean, …

in the sciences the Arabs not only learned from but went beyond the Greeks. The Greek scientific literature was translated: some of it is known today through these medieval Arabic versions. Arab geographers had a wider knowledge of the world than anyone had possessed up to their time. Arab mathematicians developed Algebra so far beyond the Greeks as almost to be its creator (”algebra” is an

Arabic word), and in introducing the Arabic numerals (through their contacts with India) they made arithmetic, which in Roman numerals had been a formidably difficult science, into something that every

schoolchild can be taught.

The intercourse that took place when East met West (first, by the Islamic expansion and later the Crusades) made the Arabs, as well as the Europeans, some centuries later, mere ”transmission belts” in the process of modernization. Wherein lies the overstatement and “fly your own kite” that Modernization is a Westernization process?

The product of this intercourse, the Renaissance or Humanism, nurtured in Italy and later unleashed on the decadent and backward tribes beyond the Alps created the conditions necessary to open the floodgates of modernization to the entire human race.

Thus, employing the principle of the diffusion of culture, we can grasp the proper historical position of Africa as a full participant in the development of human civilization, as a continent that has contributed much of its own to other cultures, as well as one whose cultures received ideas and artifacts from outside. It thus becomes pointless to speak of Africa as underdevelop and moving into a wider world. As a matter of fact she was never out of it (Herkowitz, 1962:6).

2.3. A CRITIQUE OF THEORIES OF IMPERIALISM

Imperialism is a policy of extending the control or authority over foreign entities as a means of acquisition and/or maintenance of empires, either through direct territorial or through indirect methods of exerting control on the politics and/or economy of other countries (Evans and Newnham, (1998:244). It is the policy of a country in maintaining colonies, for example, the subjugation by Europe of most of Africa between 1870-1914, in what is known as the Scramble for Africa. The ends of this policy are often an attempt to gain more land, resources, or people. “Theories of imperialism” may differ, but the underlying premise is the same. According to P. W. Preston (1997:139), imperial expansion “to encompass large areas of the globe can be understood

in terms of the expansion of one form-of-life at the expense of other long established local forms-of-life.” The consequence of this invasion is the radical restructuring of “the indigenous patterns of economic, social, political and cultural life” (Preston, 1997:139). In what follows is the application of the Hobson-Leninist’s theories in explaining the European scramble for Africa.

In December 1958, Ghana served as host to the All-African Peoples’ Conference, which made the unification of Africa one of its central themes. Chairman Tom Mboya of Kenya vehemently screemed: “Europeans, scram out of Africa” in explicit refutation of the European scramble for Africa (Emerson, 1960:5). This is not anymore strange since historic African nationalism can be dubbed the crybaby of the century. The ardour and gusto with which the colonialists were excoriated betray the consternation and despair of the nationalist leaders, who had themselves, achieved substantial acquaintances with the West (the base of their popularity).

Its sonority reached an all-time high in the writing of the late Kwame Nkrumah, the eminent African statesman. For those who fail to fathom this quixotic exercise in exorcism, I do not hesitate to point out that “Mumbo Jumbo” is an African word, and the exercise is of tremendous import to the mind of the African. It is scapegoating. Or is it? (Lloyd, 1971:253-258).

Beyond the hullabaloo, however, the reactions of the imperialists were palpable. It was a mixture of collective remorse and indignation. In a rare outburst of temper, the late Professor Richard Pares asked: “what answer are we to make to the revolt of three-quarters of the human race against colonialism? Obviously we shall not say to the liberated peoples: Come and stamp on us for a hundred and fifty years; then we shall be all square and you will feel better”(Harris, 1970:16).

It is obvious that of the plethora of theoretical arguments put forward in a bid to explain the European scramble for Africa in the late 19th century, the only one the African nationalists found

clinching is the Hobson-Leninist thesis. Lenin’s argument is basically simple and it rests on the notion that the poverty of Africa is a direct result of external exploitation. If the advanced economic countries of the world were relatively rich this is because those countries had exploited colonies (Harris, 1970:12). This argument, wholly true, will be dismissed here on two grounds. First, the denunciation of imperialism in terms of its primary purpose is considered insufficient. Sure enough, imperialism promotes the interests of the few advanced powers, but the real weakness of the argument is that it obscures its principal role as a necessary condition for revolutionary change. The Marxian dialectics considers imperialism crucial, and as one Soviet ideology phrases it, “Imperialism itself is the stimulator of revolutions”(Emerson, 1960:7).

I am not by any means absolving the Imperialists from their remorse and infamy. In trying to accentuate the role of colonialism as a modernizing factor, par excellence, I run the risk of being branded an apologist. But far from me be it. If it is flattering to the ego of the Western world to be ascribed the role of modernizers, then the sarcasm here is that they did it the Western-way-haphazard, as it were. The balance sheet shows more debit than credit. The records are sullied by the inhuman traffic in slaves, the decimation of Indian populations in the Americas, the disintegration of the peoples in the South Pacific and the atrocities of King Leopold in the Congo. Who holds brief for such notorious crimes against humanity?

Without losing track for the second reason for rejecting this thesis, I shall here digress to expatiate at length about the Spirit of Imperialism. Professor Emerson (1960:7) summed up the epic thus, “the entire process appears to be far less the product of conscious human intent than of the working of forces of which men were only dimly aware.” In sum, it is human development and progress coming to roost. The Western world was just a cog in a big wheel of development and progress.

Imperialism, by definition, “involves the domination of one people over another, of a stronger over a weaker community; yet it would be grossly improper to assume a universal identification of greater strength with loftier culture”(Emerson, 1960:6).

Professor Carlo Cipolla’s (1972:26) theory of the “Two Revolutions” offers some relief here. He says that:

The Agricultural Revolution which occurred in the Near East some time around 9.000 B.C. spread all over the world. By A.D. 1780 the hunting stage had long since been abandoned by nearly all mankind and the last strongholds of the hunters were being invaded by the triumphant farmers. Then, late in the eighteenth

century, the second Revolution was born: the Industrial Revolution. England was its cradle. Its diffusion was… Wherever the Industrial Revolution penetrated, it brought into the entire structure of agriculture the

dominant productive sector of the society.

This is the closest that one can come, to an analysis of the situation. It is the allocation problem, once again being modified. Cipolla (1972:109-110) likens the two revolutions to ‘muscle power’ and ‘machine power’ in his evaluation of the energy sources of man. He shade more light on the point in these words:

The Industrial Revolution is spreading all over the world. We witness that the changes are ‘not merely industrial but also social and intellectual’… A new style of life has to be emerging, as another disappears forever. Every aspect of life has to be geared to the new modes of production. Family ties are on the wane and give way to broader perspectives for larger social groups. Individual saving gives way to collective social services, undistributed profits and taxes. The rounded philosophical education of the few is set aside

in favour of the technical training of the many. Artistic institutions must give way to technical precision. New juridical institutions, new types of ownership and management, different distributions of income,

new tastes, new values, new ideas have to emerge as an essential part of the industrialization process

I have here quoted quite extensively from Cipolla for two main reasons: First, it saves the trauma of describing the Traditional-Apollonian African existence all over again. I do not mean to “deny the developmental aspects of pre-colonial systems. Traditional societies were not all subsistence economies … various forms of money were in use long before European intervention. Ports and markets were very elaborate”(Apter, 1967:50-51). But these did not preclude modernization. Does it matter if it came at the point of a gun?

The second reason for quoting him extensively is that we find in his resume a blueprint for social and political change.

And precisely to the point, my views about the Hobson-Leninist thesis being the cause of nationalists’ penchant to inveigh and berate the imperialists is given eloquent proof. The disequilibrium created by the inroads of modernization a la Western Imperialism, coupled with the paucity of resources to resolve the pressing issues made the ‘quixotic exercise in exorcism’ ineluctable. It must be remembered that at this stage, most of the nationalists had inherited the garb of governance of their own people.

A little gift of hindsight will convince the observer that most of the invectives had to do with what Colonialism failed to do and not what it did. The suspicion does not unnaturally grow that in the garrulous nationalist, the exploitation that mattered was not the pre-emption of the natural resources but the failure of the imperial powers “to devote themselves to the social welfare and advancement of the alien communities overseas which they had come to dominate in a generally haphazard process of expansion”(Emerson, 1960:9). To posit such an argument is to lose the real substance of imperialism. “The passion to plunder is what kept the imperialist going. The imperialist, out for the profit, strategic advantage, or glory of his own people”(ibid) was not likely to fulfil the divine role of modernizers. We here run into a headlong collision with

historical reality. What was the fate of the common masses in Europe during the imperial epic? Were they not being exploited too?

With the Hobson-Leninist thesis out of the way we shall now consider another thesis, which is of thunderous importance to African politics and society. This is the role of the missionary in the modernization process. “The missionaries were in effect auxiliaries of the colonial administration”(Crowder, 1968:1,13). They sanctified the activities of colonial governors. Their complaisance is variously in toned in the imperialist triad, Gold, God, and Glory (GGG) or better still, the three C’s: Colonization, Commercialization, and Christianization (CCC). “Hobson had admitted the importance played by missionary idealists, but dismissed them as the tools of economic interests”(Marwick, 1970:233).

Without indulging in value judgment, we can see the role of the missionary as vital in the modernization process. In a bid to save benighted souls, he provided education for the colonized people. It is a fact of African life that almost all the westernized elites including the nationalists were products of mission schools. The answer to the question why African nationalism never became revolutionary can now be formulated. Robert Merton (1967:42) explains:

The social role of religion has of course been repeatedly observed and interpreted over the long span of many centuries. The hard core of continuity in these observations consists in an emphasis on religion as an

institutional means of social control whether this be in Plato’s concept of ‘noble lies’ or in Aristotle’s opinion that it operates “with a view to the persuasion of the multitude” or in the comparable judgement

by Polybius that “the masses… can be controlled only by mysterious terrors and tragic fears.” If Montequieu remarks of the Roman lawmakers that they sought to “inspire a people that feared nothing

with fear of the gods and to use the fear to lead it whithersoever they pleased, then Jawaharlal Nehru observes, on the basis of his own experiences, that the only books that British officials heartily recommended (to political prisoners in India) were religious books or novels. It is wonderful how dear to heart of the British Government is the subject of religion and how impartially it encourages all brands of it

True to form, the onus of the westernization process rested on the missionary. He benumbed the African mind with noble lies, in a gist he offered him a better life after death and the present was denied him. The importance of this assertion will be seen in the chapter on ideology in this essay.

However, before any inconsistency charge is levelled at me, I must explain that the contradiction in the missionaries’ role in modernization is not my fault. The cue lies in the ‘unholy alliance between priest and pirate.’ The Historian Palmer (1967:622) couches the entire drama in such beautiful language: Imperialism “would bring civilization and enlightened living to those who still sat in darkness. Faith in ‘modern civilization’ has become a kind of substitute religion. Imperialism was its crusade.”

“To assess the effects of imperialism one must take the wider context and the universal meaning. Karl Marx, who was of course on the side of the ‘march of history’ noted the modernizing effects, as well as the evident exploitation, inherent in imperial rule”(Marwick, 1970:235). Thus, the “history of colonization is the history of humanity itself”(ibid).

2.4. PATTERNS OF COLONIALISM

Colonialism and imperialism may indeed be a lopsided partnership, but one thing is certain: we do not invade and occupy, enclose and dispossess the socio-economic, cultural and political history of races, and then sit back and compose hymns of praise in their honour.

Colonialism is a “variety of imperialism” – “it involves the settlement of foreign territories, the maintenance of rule over a subordinate population and the separation of the ruling group from the subject population” (Evans and Newnham, 1998:79). And “the relationship between the ‘mother country’ and the colony is usually exploitative” (Ibid)

Viewed from the perspective of a transformation process, Westernization, (Modernization, Western-Style) was and is a failure. Three-quarters of humanity variously referred to as: ‘the Third World’, or ’the Wretched of the Earth’, still scratches a precarious survival from the obstinate earth. The modernizers have returned to their bastions priding themselves with the sloppy way in which they accomplished their ’task’. “The imperial mystique, so passionately propagated to excuse colonial control, has been relegated to the reference shelves of history. The French, who spoke once as if a separation from any part of their empire was an ultimate drain of their blood, see now a closer community of interest with Holland [and the rest of European nations] than with Senegal. The British, so much of whose past was invested in colonial expansionism, search for their future in Germany [and the rest of Europe] rather than in India or Nigeria”(Segal, 1963:22-23). It is nothing short of a palpable sense of collective paranoia forcing them to club together (Ibid).

Now, let us survey how the task of modernization was carried out by the various colonial powers. Of special interest here are the British, French and the Belgians.

The colonial attack on African traditional systems was dislocative, and had different patterns. ”For the French, and in different fashion, the British, the key point of attack is the elite who can serve as the link between the colonial power and the native masses, for the Belgians, it is the mass itself, or at least a substantial middle class, which must be raised as a whole without thrusting a Europeanized few above it”(Emerson, 1960:8). How far the colonial stereotype of the African shaped these patterns is a matter of conjecture. The French for example, believing fervently in the idea that the Africans lacked any future or history worth calling such, ”were convinced that the only salvation for the African was his assimilation into French civilization”(Crowder, 1968:22). The qualification for assimilation was a mastery of the language, history and art of Metropolitan France. In reality, ”not more than 10% of the population of the so-called French-speaking African countries have a working knowledge of the French language. Even more elitist perhaps is the search for the black soul, which is made in terms of French philosophy, French education, literature and modes of thought. French models are the accepted models (even perhaps the ubiquitous ’negritude’), although in practical terms this may seem no more than the pursuit of the ’baccalaureate’ as the key to a job. Indeed the baccalaureate has been described as ’the superior fetish, the most powerful of fetishes in modern Africa’”(Harris, 1970, 22).

Recalcitrant and dissenters were ostracised. There was the case of Guinea; she was ’dewesternized’ overnight for refusing to toe the line.

Guinea has clearly been an exception to the usual francophone rule. When de Gaulle returned to power in 1958, the Guineans rejected the referendum. The new French President decided that if the Guineans wanted disengagement they should have it. Within days French civil servants withdrew. Out of four thousand of these civil servants, all but fifteen had gone in three weeks. Cash registers were ripped out, the

weapons of the police were withdrawn and even the library of the Ministry of Justice was removed. The Governor was ordered to remove the furniture from Government House and strip all fittings, movable and

immovable and ship them back to France. Fruit trees were cut, walls were torn down, gardens decimated, telephone wires were cut, and a ship bringing five thousand tons of rice was re-routed.

These were the modernizers at their best. One cannot withstand the glamour of comparing this phenomenon with President Nixon’s decision to ’bomb North Vietnam back to the Stone Age.’ The glamour lies not in the comparison but in the inference -- to ’dewesternize’. A sad

realization.

Strictly speaking then, in terms of decolonization, it was only Guinea that experienced this. The rest of the Francophone African countries went into a new stage of colonialism.

”The object of the Belgian colonial policy was to create a prosperous black working class (sociologically undefined) which would be content with wages rather than votes. It was felt unnecessary to provide freedom of the press, and the Belgian Charte Coloniale omitted these rights”(Harris, 1970:24). The administrative policy here was to remove the Congo from ‘politics’. Another effort was to prevent the growth of a landed European class. “In the social sphere, Belgium’s policy involved a step-by-step preparation of Congolese nationals as they evolved into Western civilization. The number of evolues were small, for the implementation of this policy called for mass primary education rather than the production of a highly educated elite”(Apter, 1963:34). The importance of the elite can be seen when we turn to the British pattern.

British colonial pattern evades definition. With slight modifications, the objective can be described as follows: Britain pursued a settler form of colonization. South Africa, Rhodesia (present day Zimbabwe) and the frustrated efforts in East Africa are eloquent proofs. Western Africa seems to have been the exception and here, the efforts were frustrated by the obduracy of the climate. Administrative policy took various turns, from the very inception of British rule. A “combination of commercial and political administration formed the classic British pattern (Apter, 1963:34). They claimed only a limited jurisdiction, and that in a circumscribed area. The climatic conditions were described as the “miasmic marshes and poisonous mists”. Reason enough to fall on local material for administrative purposes.

The first political development was the indirect rule—the administration of the country by the British in cooperation with the chiefs. At this stage the “climatic conditions had assuaged” and the “senior posts in the administrative system and legal services became the preserve of the Europeans, thus while in 1883, nine out of forty-three senior posts were held by Africans by 1908, only 5 out of 278 and by 1919 only 2 were held by Africans (Crowder, 1968:22).

In a way the westernized elite appeared only in West Africa during the colonial era because of the above-mentioned reasons. British colonial pattern generally, is a reflection of the social stratification that characterizes English life. In the colonies however, race is the determinant.

3

THE GHANAIAN TRADITIONAL SCENE AND THE IMPACT OF THE WEST

“If a race has no history, if it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated”

Carter G. Woodson

To think that Africans have a tradition and beliefs systems was something that if ever uttered, would have received little attention during the colonial era.

This chapter offers a brief excursion into the historical background of our case study – the Gold Coast. First, it is intended to provide a brief definition of the people of the Gold Coast as they moved from independent tribal status into colonial status. Secondly, it is intended to point out some of the traditional patterns of political institutions and leaders, and show how the British authorities met (and altered) such institutions. And lastly, it sets out to analyse the impact of colonialism on the Ghanaian traditional institutions. The description of tradition is very important for therein lies the key to understanding the importance of traditional leaders and institutions.

Samuel Fleischacker (1994:45) defines tradition as “a set of customs passed down over the generations, and a set of beliefs and values endorsing those customs.”

The Ghanaian Philosopher, Kwame Gyekye (1997:221), recognizes the value of tradition, but argues that in practice tradition is often questioned and modified by its adherents over time, so that it remains dynamic. Tradition to him is “ any cultural product that was created or pursued, in whole or in part, by past generations and that, having been accepted and preserved, in whole or in part, by successive generations, has been maintained to the present.” As such traditional institutions are not incompatible with modernity. Gyekye (1997:217) concurred:

it may be said that from the point of view of a deep and fundamental conception of tradition, that every society in our modern world is “traditional” inasmuch as it maintains and cherishes values, practices, outlooks, and institutions bequeathed to it by previous generations and all or much of which on normative

grounds it takes pride in, boasts of, and builds on.

There were well-defined norms, beliefs and techniques of social control in African system. The structures of “belief were not only mandatory in a social sense but also explanatory in a material

one, and, as such, were the basis of rational thought” (Davidson 1969: 114). Traditional leaders are the guardians of traditional norms that are respected in particular communities from generation to generation. These norms could be outlooks on life, ways of relating or of resolving disputes, institutions etc, and as such traditional leaders and institutions are an important channel through which social and cultural change can be realized.

Apter (1963:83), says that the most important element that these traditional systems have in common is a basic knowledge and commitment to the primordial past -- ”the best way to act in traditional systems, is the way our fathers have ordained. That which is legitimate is that which is enshrined in the past”. To understand traditional politics one must first understand religion. The ancestors were the “jealous guardians of the highest moral values … the axiomatic values from which all ideal conduct has been deemed to flow” (Davidson 2000: 109). Religious integrity is social integrity, and the religious supports to social structure are fundamental to the maintenance of the system. Originally religion ”pervades everything: everything social is religious,” this is how Durkheim saw the situation. According to Burns and Ralph (1974:16) ”religion is everywhere an expression in one form or another of a sense of dependence on a power outside ourselves, a power which we may speak of as a spiritual or moral power.”

Thus in these societies, individuals develop what David Riesman, in his ‘modal personality typology’, calls a ‘traditional-oriented personality’ – “a personality that has a strong emphasis on doing things the same way that they have always been done. Individuals with this sort of personality are less likely to try new things and to seek new experiences”.

What is the future of a society, wholly submerged in a total commitment to the past? The immediate answer is such society cannot brook any substantive change.

3.1. THE ASHANTI (AKAN) TRADITIONAL SYSTEM

The Ashanti, occupying the central area of Ghana, once held sway over most of the territory that make up modern Ghana. They were industrious in pursuing attacks and forays against the Fanti who occupied the western coastal area. The Fanti were quick to ally themselves with European outposts and settlements along the coast, such alliance after European intervention being manifest in collaboration with the British in wars against the Ashanti Confederacy.

The Ashanti Confederacy, a federal grouping of Ashanti states under the control of a paramount chief (Asantehene), was an elaborate military hierarchy with powerful armies, a bureaucracy, and a taste for imperialism which brought them into immediate conflict with the British, often to the