“IN THAT CASE I CHOOSE TO

WORK WITH SHORT

STORIES”

A study about how English short stories are taught by nine upper secondary school teachers in Sweden and said teachers’ attitudes towards short stories

ANTON ENGWERS

English for Teachers in Secondary and Upper Secondary School: Degree Project. ENA314 15 credits

Supervisor: Karin Molander Danielsson Examiner: Thorsten Schröter

______________________________________________________________________

Abstract

Reading English literature can help learners of English as a foreign language (EFL) to develop their reading ability as well as other language skills. Reading can also have other benefits for EFL students such as learning about the target language’s culture or an English variety in written form. This present study investigates what types of literature are used in Swedish upper secondary school, the EFL teachers’ attitudes towards short stories compared to simplified novels/graded readers and their preferred assessment methods associated with literature teaching. The majority of the teachers that took part in this survey have a positive attitude towards short stories and use them in their EFL classes. The results also show that after the students have completed reading a short story, most of the teachers that participated in this survey preferred to combine examination methods such as a group discussion with a written test.

The title of this paper comes from one of the informants’ comments when asked if she would rather use a short story or a graded reader in her English class. This informant had used graded readers in her English language classroom, but she and everyone that took part in this survey chose short stories over graded readers.

______________________________________________________________________

Keywords: Short stories, Graded readers, EFL teachers’ attitudes, Teaching literature,

Table of Contents

1 Introduction ... 1

2 Background ... 2

2.1 English literature in the Swedish curriculum ... 2

2.2 Government reports regarding the importance of reading ... 3

2.3 Previous research ... 4

2.3.1 Literature in the EFL classroom ... 4

2.3.2 Teachers’ attitudes towards literature ... 5

2.4 Points of view regarding graded readers ... 6

3 Method ... 8

3.1 Informants and the context of this study ... 8

3.2 The questionnaire, data collection and analysis ... 9

3.3 Ethical considerations ... 10

3.4 Limitation of this study ... 11

4 Results ... 11

4.1 Literary forms, and how short stories are taught ... 11

4.1.1 Which literary forms have you used in your English classes? ... 11

4.1.2 For what reasons have you used short stories? ... 12

4.1.3 What is your preferred method of examination? ... 13

4.2 Upper secondary teachers’ attitudes towards short stories ... 15

4.2.1 Are you using more, or fewer short stories now compared to when you first started as a teacher? ... 15

4.2.2 What is your attitude towards short stories? ... 16

4.2.3 The choice between short stories and simplified novels/graded readers .. 20

4.3 Summary of the results ... 22

5 Discussion ... 22

5.1 Discussion of the results from section 4.1: Literary forms, and how short stories are taught ... 22

5.2 Discussion of the results from section 4.2: Upper secondary teachers’ attitudes towards short stories ... 23

6 Conclusion ... 25

Works cited ... 26

Appendix 1 – The structure of the questionnaire ... 29

Appendix 2 – Table of short stories... 33

List of figures:

FIGURE 1 – Types of literature that have been used ……….12FIGURE 2 – Reasons for using short stories ………..13

FIGURE 3 – Examination methods ………14

FIGURE 4 – Using more or fewer short stories ……….15

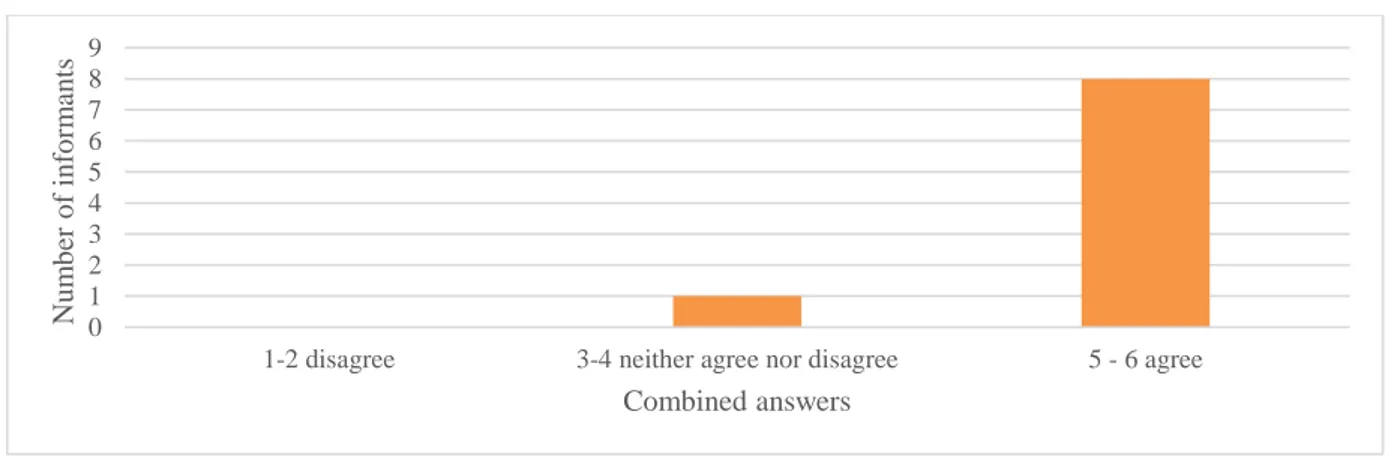

FIGURE 5 – Short stories can motivate students to read from the beginning ………...17

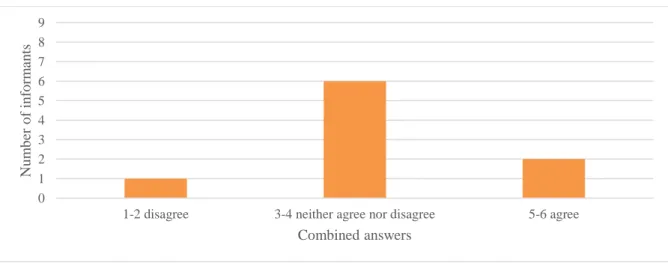

FIGURE 6 – Short stories are easy to use when I want to illustrate the structure of a story ………17

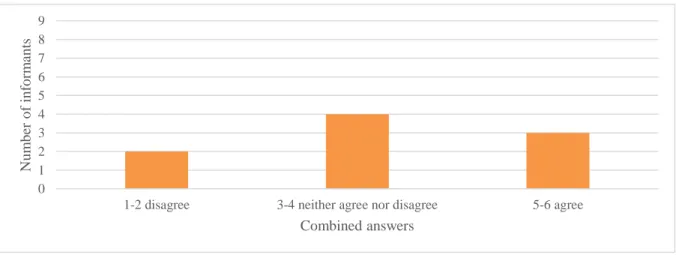

FIGURE 7 – Short stories have more benefits than simplified novels/graded readers ..18

FIGURE 8 – Short stories are perfect for students who have English as their third or fourth language ………...18

FIGURE 9 – It is better to use a short story than an excerpt from a novel ………19

FIGURE 10 – I can let my students find a suitable short story on their own ………….19

FIGURE 11 – Reading several short stories will generate more reading practice than reading one novel ………...20

FIGURE 12 – It is easy to find short stories that are appropriate for my students’ level of language proficiency ………..20

List of tables

TABLE 1 – How the informants responded to each statement ……….…161 Introduction

During my university studies as a teacher-student, I experienced that some of my teachers talked highly about how great novels are and the importance of students reading them, and when I had my practicum internship, I heard the same points of view from several teachers at the upper secondary school I had my internship. During the summers, I worked as a substitute teacher in Swedish prison education, which is similar to regular adult education in Sweden, but for convicted inmates striving to improve their grades. The teachers there talked about the benefits of graded readers as reading material to help develop their English students’ language skills and how graded readers can be useful for students who are beginners in English. These observations made me wonder if novels and graded readers are the preferred literary forms used in English as a foreign language (EFL) education or if short stories could be a more suitable literary form as reading material. While graded readers are based on pre-existing novels, they have a simplified linguistic structure and a limited vocabulary as well as a lower number of pages than a regular novel. On the other hand, short stories also have fewer pages than a novel, but short stories have the same well-written narrative structure as novels. Nick Dawson, editor for Penguin Readers Teacher’s Guide to Using Graded Readers, describes graded readers as books containing a language that matches the student’s level of proficiency (2). According to Dawson, the main idea of using graded readers is to help the learner increase their vocabulary and develop their reading skills. Therefore, reading a graded reader, with its simplified language structure, can encourage students to acquire new words and finish reading a book as well as it can develop their reading comprehension so that they later can read texts that have not been simplified (3).

Based on this definition of what graded readers are, I wanted to know if and how short stories are used in EFL classes in upper secondary schools in Sweden and if short stories are not more appropriate to use as EFL teaching material compared to graded readers. Since short stories are written without a simplified language structure.

Scholars have studied, or documented, teaching activities involving literature (Erkaya; Parkinson & Reid Thomas; Tso). They give examples of how longer texts can be read and worked within the classroom over an extended period. Shorter texts can be read within a few days or even within a lesson’s time frame. Graded readers could be used for students that have

trouble with reading and/or understanding. But their simplicity might not give the students input in the form of authentic English. Short stories, on the other hand, could also be read in a short amount of time and give the readers that kind of input.

There have been several studies conducted by teacher-students regarding how EFL teachers in upper secondary school work with different literary genres and texts, and how literature can be useful for language learning in EFL classes (Edsman 2019; Ekehult 2013; Falk 2015). The present study attempts to further investigate which role literature has in the EFL classroom, but focuses on the use of short stories as teaching material. It aims to answer the following research questions:

• How do the participating upper secondary English teachers work with short stories? • What attitudes do the participating English teachers have towards short stories

compared to graded readers?

2 Background

This section is divided into four subsections. Section 2.1 presents what the Swedish

curriculum has to say about how literature should be included in the English courses 5, 6 and 7 at upper secondary school. Section 2.2 reviews government reports regarding teaching literature as a part of language education and students’ attitudes towards reading. Section 2.3 examines previous research connected to the research questions. To give the paper a clearer structure, section 2.3 is divided into two subsections which describe literature in the EFL classroom and teachers attitudes towards literature. Section 2.4, finally, reviews the literature on benefits and drawbacks associated with graded readers in the EFL classroom.

2.1 English literature in the Swedish curriculum

It is not clearly stated in the curriculum for upper secondary school, published by the Swedish National Agency for Education, which literary genres or types of literature, such as novels, short stories, poems etc., teachers are supposed to teach and include in their English classes. In the specifics for the course English 5, which is the first English course in Swedish upper secondary school, it says in the subsection marked “reception” that the course should include “literature and other fiction” (Skolverket, 2011). This allows teachers to interpret what

literature they may use in their English classes. In the corresponding section for the English 6 and 7 courses, it is stated more clearly that the courses should include “contemporary as well as older literature such as poetry, drama, and songs” (Skolverket, 2011). So, while teachers are free to choose how to work with literature and which genres and texts they want to use in their English courses and classes, the curriculum recommends teachers have a diversity of literary texts from different literary epochs. A teacher should therefore ask him- or herself what the students should get out of the assigned reading and how to achieve this. Teachers can, apart from the curriculum, also read different research studies that have been conducted by the Swedish National Agency for Education regarding the importance of reading as well as regarding the function of literature in upper secondary school. The upcoming section presents some reports conducted by the Swedish National Agency for Education as well as the

Swedish Media Council.

2.2 Government reports regarding the importance of reading

Reading literature does not only have language learning benefits. Christoffer Dahl states in his article from 2016 that it could have beneficial effects in other subjects if the students are taught to read different sorts of texts. Teachers should therefore include different texts in their classes, so that the students learn how to recognise different text genres and what reading strategy they should use in order to understand as much as possible of the text (Dahl). He also argues that if students know the differences between different types of texts, it can help them further in their educational journey after they graduate from upper secondary school.

Therefore, it is necessary to read not only for language development but also for other educational aspects.

Reading literature should have a natural place in education. In Därför läser vi skönlitteratur (“That is why we read fiction”), Bengt-Göran Martinsson states the importance of reading and why it should be promoted in upper secondary school. Although his argument focuses on the subject of Swedish, it could be taken to suggest that literature be a part of any language development. One of his main points is that reading lets the students’ discover different points of view of the world so that “[t]hrough literature, a reader can leave his or her own world and enter the alternative world of literature with the outcome that his or her fundamental beliefs have been affected” (7) [my translation]. Literature is, therefore, a useful tool for introducing different points of view from other cultures to the students. However, Martinsson also states

that teachers should not only use literature as a tool for education. Otherwise, the students’ interests and desire to read may be hindered (1). In other words, as teachers implement

literature in EFL classes, the assigned reading should encourage students’ desire to read more. Swedish adolescents’ interest in reading is, however, declining according to a report by the Swedish Media Council (7). The report, from 2019, is a quantitative study about young people aged 9–18 years and their use of media. The results show that not only reading for

entertainment is decreasing overall, but also that the informants read less as they grow older (30). However, according to Martinsson’s article, students can become motivated to read if teachers do not merely focus on which books adolescents should read, but rather on how the teacher uses the reading material (3) and how he or she helps the students to find the beauty in reading fictional literature. Martinsson also argues with the support of Martha C. Nussbaum’s works, that reading literature educates students to become empathic world citizens (8).

Reading for entertainment and empathy are not the only reasons for using literature, however. The next section introduces the benefits of using literature in EFL classes, based on previous research.

2.3 Previous research

This section provides research findings connected to literature in EFL classrooms (2.3.1) and what attitudes teachers have to different forms of literature 2.3.2).

2.3.1 Literature in the EFL classroom

Literature has been used in second language learning for a long time (Bobkina 249; Erkaya 2). In the early days of language education, students translated a literary text from the target language to the students’ first language. Over the years, using literature in second language and foreign language learning has developed beyond translating and just learning how to read in the target language. Literature can be used for several purposes.

In EFL classrooms, literature can be used as a tool to increase students’ vocabulary (Arjmandi; Erkaya; Yilmaz; Zeybek), to develop their higher-order thinking (Erkaya; Zeybek), to teach the students about cultural differences (Krulatz et al.; Luukka), work with creative writing (Erkaya; Tso; Parkinson & Reid Thomas; Zeybek), and to develop their interpretative abilities (Arjmandi; Erkaya; Yilmaz). Thus, literature is a multifaceted tool in

EFL learning. How teachers choose what literary text to assign to their students and how to use literature is an important aspect of their lesson preparations.

2.3.2 Teachers’ attitudes towards literature

EFL teachers’ attitudes towards literature may vary depending on where in world the teachers live and work. In a study by Gülin Zeybek, she focused on Turkish pre-service teachers’ feelings associated with four literary forms: novels, short stories, poems, and plays. One of her findings is that short stories had the most teacher-related advantages such as teaching abstract relationships, presentation of the target language and its culture (35) to name just a few. The pre-service teachers’ attitudes towards short stories were more positive compared to their attitudes towards poems. The reason is that, according to Zeybek’s informants, they had more teacher-related advantages with using short stories during their EFL lessons, than when they used poems. Certainly, Zeybek also mentions problems with teaching short stories, for instance, lack of students’ involvement and time management (33) which refers to that one of the pre-service teachers had trouble completing his teaching activity involving reading a short story within a lesson. However, her findings show that poems had the most teacher-related problems. Out of the four literary forms that Zeybek used in her investigation, poems had seven out of nine teacher-related problems such as the students used their first language during the lesson and selecting the material for the lesson while short stories had none of these mentioned problems but the four problems such as mentioned earlier (33). However, other findings suggest that poems are more preferred by teachers.

In a Finnish study by Emilia Luukka, the majority of her 21 teacher informants answered that they used poems more than any other literary form in their EFL classes. The second most commonly used literary form was novels (204). However, only 2 of the participants indicated that they used any literary texts ‘often’ and the majority, 14 out of 21, used literary texts ‘rarely’ (203). According to Luukka and Zeybek’s findings, teachers had different attitudes regarding the different literary forms and faced different teaching problems with each form such as the students’ involvement in the reading activity (Luukka 206; Zeybek 33).

Luukka’s participating teachers also had different points of view regarding literary periods. The majority preferred authors from the 20th and the 21st century. The only authors from the 16th–17th century that her informants had chosen were William Shakespeare and John Donne

oldest author of the 20th century used by any of the teachers. Luukka’s findings showed that there are at least two literary periods, the Romantic period, and the Victorian age, that the teacher informants did not work with (204). This can be compared to the circumstance that, the Swedish curriculum states, and as mentioned earlier, that the core content of the English 6 and 7 courses, should include “contemporary and older literature […]” (Skolverket, 2011). Using older literature is also encouraged by Jenny Edvardsson, a university lecturer in educational science at Kristianstad University, in an interview titled Så får du eleverna att läsa klassiker (“How you get your students to read classic literature”) by Anna Hultberg (Läraren.se). Edvardsson believes that reading classic literature will give students “not just common knowledge but also takes the students on an exciting journey through time and space” [my translation]. Edvardsson promotes, as a first step in the working process, to have the teacher read the beginning of the text aloud as well as explain its historical and literary background (Läraren.se), which will help the students to actually read the assigned material. Edvardsson believes that both teachers and students can be encouraged to read classic

literature and that the students can gain the knowledge that is within reading classic literature or other older literary texts as suggested by the Swedish curriculum.

2.4 Points of view regarding graded readers

As mentioned in the introduction, graded readers have a limited vocabulary and simplified linguistic structure to help learners to learn new words and develop their reading skills. According to Dawson, when EFL students encounter familiar words and sentences this might help them to understand new words (2). In other words, even if a student does not understand one word within a sentence, they might understand the other words in the sentence so that they understand the context and by so learn what the unfamiliar word means. In the discourse regarding graded readers, one controversial issue has been their language authenticity. On the one hand, the simplified structure can motivate students to finish the text and improve their reading skills. On the other hand, graded readers do not represent how language is used authentically.

One who promotes graded readers is Rob Waring and he describes graded readers used with EFL students as steppingstones into reading literary texts that have not been simplified, and he compares using graded readers to how parents simplify their language when they are talking to young children as they acquire their first language (er-central.com). Because of the

structure of graded readers and their word limit (which can be as little as 500–1500 words, depending on the level of the text), learners can read several graded readers in a short amount of time. This is supported by Mustafa Albay. He presents in an article what different

researchers and scholars have found regarding the benefits of graded readers such as

improving their reading confidence and their reading speed (177). Therefore, Albay maintains that graded readers are good for language learners, and he states in the conclusion that

“[l]earners who read extensively are prone to make gains in overall language proficiency” (179). In other words, if students read several graded readers at their level of language proficiency, they improve their reading skills, but they will also gain the confidence of completing reading a regular book.

One of those who are sceptical of using graded readers in EFL learning is Amanda Gillis-Furutaka, who investigated some overlooked aspects regarding graded readers. One of her findings was that the Japanese EFL students that took part in her study had trouble

understanding the differences when the pronouns this and that were used and what they pointed to in the example texts (12). Gillis-Furutaka concluded that if students read texts that are at their level of language proficiency but “are still unable to read and comprehend directly in the L2 [second language], they are not getting the practice they need to build up

automaticity and improve their overall linguistic skills” (16). In other words, if students have troubles understanding a graded reader and need to translate the text in their heads to their first language rather than reading the text in the target language, then Gillis-Furutaka means that reading a graded reader may hinder their language development.

Another perspective is that learners do not have to read stories that have been written with a simplified sentence structure in order to learn the target language. Irma-Kaarina Ghosn writes in her book Storybridge To Second Language Literacy that if the reading material is too easy or if the student does not see the value of the reading material, they will not be motivated to read the assigned material and their language will not develop (10–11). Ghosn points out an important language difference between graded readers and good quality children’s literature:

good children’s literature often contains the kind of elaboration that can improve young learners’ comprehension. For example, in Velveteen Rabbit (Williams, 1985), a toy rabbit is left “out until long after dusk” (n.p.). While the word “dusk” is likely to be unfamiliar to young learners, the next sentence elaborates by explaining that someone had to look for the rabbit with a candle, and that the boy could not sleep unless he had his rabbit. Thus, it becomes clear that dusk has something to do with evening. Illustrations further help clarify the meaning. (17–18)

In other words, Ghosn points out how a more elaborate language might be easier for learners to understand than the simplified language of the graded readers.

To sum up what has been mentioned so far in this section, those favouring graded readers claim that these literary forms are designed to develop foreign language learners’ reading ability and increase their vocabulary. The ultimate goal with simplified texts is that learners should be able to learn how to read texts that have not been simplified. Those who disagree with using graded readers claim that even if students read texts that are appropriate for their level of language proficiency, they do not develop their understanding of the target language if they need to translate it to their first language. The opponents to graded readers suggest that it might be better to use texts that have been elaborated with paraphrasing and explanations of new or difficult words to help a student to fully understand the text.

Since different views of the usefulness of graded readers exist, this question is also addressed in my investigation, and especially in relation to short stories and what attitudes upper

secondary teachers’ have towards short stories.

3 Method

This section is divided into four subsections. Section 3.1 presents information about the informants and the context of this study. Section 3.2 presents the structure of the

questionnaire that was used to collect the relevant data, and how it was analysed in order to arrive at the results. The ethical considerations which are important when dealing with human informants are presented in section 3.3. Finally, section 3.4 presents the limitation of this study.

3.1 Informants and the context of this study

To collect relevant data, an online questionnaire was created in Google Forms and sent to two upper secondary schools in Sweden and a total of 20 English teachers. To minimize physical contact with the teacher informants during the COVID-19 pandemic that was in progress at the time of the data collection, an online survey was the preferred choice. The other reason for using a questionnaire was to receive as many informants as possible. However, I had to hope that the teachers who received the email would choose to participate and that they would not encounter any trouble with the link or the survey. In case they did, my contact information

was added at the beginning of the survey. As far as I know, all of the participating teachers were able to complete the survey without trouble.

Out of the 20 upper secondary English teachers approached, nine took part in the survey, seven women and two men. At the time of the data collection, three informants taught at theoretical programs, one only taught at vocational programs and the other five taught at both types of programs. The number of years that the informants had been teaching ranged from 6 to over 31 years.

3.2 The questionnaire, data collection and analysis

The link to the questionnaire was sent out to the teachers in November 2020, together with a letter asking for their participation as well as informing them about this degree project. The informants then had then two and a half weeks to participate. In addition, the attached letter gave information about some ethical considerations regarding the informants’ participation. The questionnaire comprised a total of 13 questions and statements divided into four parts (see appendix 1). The first four questions were designed to elicit information about the participating teachers. Next came two questions, one that asked to see what literary forms the teachers had used and another to see if the teacher informants had worked with short stories at all in their EFL classrooms. Question 6 was a so-called stop or go question: if a participant answered that they had never used short stories in any of their English classes, he or she did not have to participate further in the survey. However, all of the participants answered that they had used short stories, meaning that all the questions were answered by all nine

participants. After question 6, the survey focused on teaching literature and teachers’ attitudes towards short stories.

Part 3 consisted of eight statements and the informants were asked to answer on a scale of 1– 6, where 1 indicated that they fully disagreed with the statement and 6 indicated that they fully agreed with the statement. The statements were formulated to find out about the informants' views regarding short stories. To see more clearly how the informants answered and to better see trends and connections between the statements, the results section 4.2.2 presents a table of how each informant had answered and eight figures with merged answers. Part 4 began with eight reasons for using short stories. The informants were asked to check all the boxes that matched what they had done with short stories. Parkinson and Reid Thomas’

Teaching Literature in a Second language was used as a guide for formulating suggested activities, such as reading aloud, reading for content, and linguistic analysis, to name a few (27–33). Then followed questions about how the teachers would examine the students after they had read the assigned short stories and the informants could only choose one of the seven alternatives or write their own suggestion. To further connect to the discussion presented in section 2.4 regarding the use of graded readers, the informants were also asked: if you have to choose, would you use a) short stories or b) simplified novels/graded readers in your English classes. Then, the informants were asked to mention some titles of short stories that they had used in their EFL class, but the teachers did not have to name the author of the short stories. The reason for not asking about the name of the author was the assumption that if the teacher could not provide both author and title, they might not answer the question at all. However, this question is not presented due to the fact that some titles were not short stories and it could not be presented how these titles had been used. A table of what titles the informants wrote is presented in appendix 2.

Finally, the informants were asked if they would participate in an interview to receive qualitative data. If they wanted to participate, they could leave their email addresses in the commentary field. Two informants had left their email addresses, however when contacted again, they did not want to further participate in this study due to their workload that had increased during the pandemic.

The results from the online questionnaire were analysed both digitally and manually. The individual answers, free text comments and graphs were organized to better present the results in this written report. There were no other methods used to analyse the material.

3.3 Ethical considerations

This study conformed to the ethical guidelines published by the Swedish Research Council, in so far as the teachers that participated were informed about secrecy, anonymity, and their right to end their participation at any time. The Swedish Research Council recommends researchers follow the concepts of good research ethics and the four main requirements: information requirements, consent requirements, confidence requirements, and use

requirements (6). Before the teachers could answer the questionnaire, they were informed that they would be anonymous in this report and that they could at any time cancel their

3.4 Limitation of this study

Since there were only nine teachers from upper secondary school that participated in this study out of the 20 teachers that were asked, there is a limitation to what can be concluded how short stories have been used in EFL classes in general. However, how the participating teachers have answered gives us an idea how short stories could be used in EFL classes and what examination methods that could be used in order to assess the students after the reading assignment is completed.

4 Results

This section presents the results from the questionnaire and is divided into three subsections. Section 4.1 presents results regarding the teaching of literary forms in general and short stories in particular, as well as preferred form of examination. Section 4.2. shows what the informants’ attitudes are towards short stories and is divided into three subsections. Section 4.3 gives a summary of the results in order to draw a more accurate conclusion.

4.1 Literary forms, and how short stories are taught

This section is divided into three subsections and present the results regarding which literary forms that have been used in EFL classes, for what reasons short stories have been assigned to EFL students, and what methods the informants preferred to use after the students had

finished reading the short stories.

4.1.1 Which literary forms have you used in your English classes?

After some initial questions regarding the informants and if they have ever used short stories in their English classes, the informants were asked to indicate from a list which literary forms they had used. There was a commentary field if they wanted to add a literary form that was not included in the list. One informant commented that she had used the coursebook. No other comments or other literary forms were given by the informants.

Figure 1 shows that the most popular types of literature that are used by the informants are news articles and short stories. The least used literary types were comic books and, as the one teacher wrote in the commentary field, the coursebook. Three informants indicated that they

have used simplified novels/graded readers in their English classes: two female teachers with 26–30 years of teaching experience, and one male teacher who had been teaching for over 30 years. This question was used to determine which types of literature are used in upper

secondary schools and to find out if any teachers had used graded readers. That said, there might be other forms of literature that the teachers use that figure 1 does not include.

Figure 1 – Types of literature that have been used

4.1.2 For what reasons have you used short stories?

The informants were then asked to reflect on how they had worked with short stories and which method(s) they would use for examination after their students have read an assigned short story. The upcoming sections present why and how the teachers have chosen to work with short stories.

To further investigate why the informants had used short stories in the EFL classroom, they were offered ten suggestions. The teachers were asked to check all the boxes that

corresponded with how they had assigned short stories to their students. A commentary field was included with this question in case the informants wanted to add another reason or

additional information. Figure 2 illustrates the informants’ claims as to why they had assigned their students a short story, and the most commonly chosen reasons were to develop my students’ reading skills and to expand my students’ vocabulary. To develop my students’ writing skills and to teach about literary terms were also chosen by more than half of the informants.

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Comic books Other: Coursebooks Children's literature Simplified novels/graded readers Poems Dramas/plays Songs/lyrics Novels Short stories News articles Number of informants T y p es o f liter atu re w h ich th e teac h er s co u ld ch o o se fr o m

Figure 2 - Reasons for using short stories

Two informants commented on this question. One wrote that she had used short stories “[t]o practice discussing literary interpretation (message, imagery, symbols) and also to simply practice and assess literary analysis”. This was also the only teacher who ticked that she had used short stories to demonstrate different English dialects/variations in written form. Another teacher wrote that he had used short stories “[a]s basis for discussion”. Also, this informant stated that he had rarely used short stories in his teaching and that he preferred novels such as modern classics and teen classics. These comments will be discussed in section 5, but they give us an indication of teachers’ attitudes towards short stories. After this part about the reasons for using short stories, the focus of the questionnaire turned to how the teachers would examine the students after they have read short stories.

4.1.3 What is your preferred method of examination?

The informants were asked what kind of examination they would use after their students had read the assigned short story. They were given seven alternatives and the opportunity to add further information (see appendix 1, question 9). Figure 3 shows that the most commonly chosen alternative was a combination of an oral examination with a written test where the students must answer questions connected to the short story. The figure also shows that seven out of nine informants would have an oral examination, such as a group or a class discussion,

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Nu m b er o f in fo rm an ts

The different reasons

Reasons

1. To develop my students’ reading skills. 2. To expand my students’ vocabulary. 3. To develop my students’ writing skills. 4. To teach about literary terms. For

example, round character, turning point,

in medias res, rising action, intertextuality et cetera.

5. To give my students an understanding of different cultures where English is used.

6. To read aloud to develop with my students’ listening skills.

7. Other reasons.

8. To read aloud for other purposes (than listening comprehension).

9. In combination with a video clip, with a similar theme.

10. To demonstrate different English

dialects/variations in written form.

11. To prepare my students for the Swedish

and combine it with another examination method. Only one informant chose to only have an oral exam without combining it with another method. This was one of the male informants, who had been a teacher for 11–15 years and who, as mentioned earlier, preferred teenage novels and modern classics. The second most popular combination of methods, chosen by four informants, was to have a written test or a book report/essay combined with another method.

Figure 3 - Examination methods

Two informants chose to comment on this question about how they would examine the students after reading a short story. One teacher wrote “Oral discussion and analysis + comparison”. This answer is included in the category marked ‘other’ in figure 3, but it is also included in the category ‘oral discussion’. However, since it is not clearly stated how the analysis and the comparison are performed, they are not included in any of the other alternatives.

Another informant wrote, “I often use a wordtest [sic] as well, to encourage students to pick up new vocabulary.” This answer is only included under ‘other’ in figure 3 because it is not clear what “as well” refers to. Again, a combination of several methods is preferred by most informants. 0 1 2 3 Combine an oral discussion with a written test Other Oral discussion Book report/essay Combine an oral discussion with a book report/essay Combine an oral discussion, with a book report/essay and a written test A written test Combine a book report/essay with a written test Nu m b er o f in fo rm an ts Examination methods

4.2 Upper secondary teachers’ attitudes towards short stories

This result section illustrates the informants’ attitudes towards short stories and graded readers and thus connects to the discourse regarding graded readers that was introduced in section 2.4. The first subsection is about the informants' use of short stories in quantitative terms, the second about the teachers’ attitudes towards short stories and, finally, the third presents how the teachers would choose between short stories or graded readers to use in their EFL classes.

4.2.1 Are you using more, or fewer short stories now compared to when you first started as a teacher?

To further investigate the informants’ attitudes towards short stories and whether they use of short stories had increased or decreased during the years that they had been teaching, they were asked if they were using more or fewer short stories now compared to when they began teaching. Figure 4 shows the results.

Figure 4 - Using more or fewer short stories

The figure shows that six out of the nine informants answered that they use more short stories now compared to when they first started as teachers. One informant added a comment saying that although she had used the same number of short stories, she used different titles now. One of the informants gave a longer comment. He wrote that he used short stories “[…] very rarely, but since I didn't use them at all when I was new, I guess the answer would be more”. This informant also chose to check the box marked ‘more’. This informant commented in connection with another question that he had had difficulties finding suitable short stories that his students like and that he preferred novels.

0 1 2 3 4 5 6

More Fewer Same I do not know I have nothing to

compare to Nu m b er o f in fo rm an ts Answers

4.2.2 What is your attitude towards short stories?

The informants were presented with eight statements in an attempt to further explore their attitudes towards short stories and graded readers. For each statement, they had to choose on a scale between 1 (meaning that they fully disagreed with the statement) to 6 (meaning that they fully agreed with the statement) and only one answer was possible to give. Table 1 shows how the informants answered.

Table 1 - How the informants responded to each statement

Statements 1 Fully

disagree

2 3 4 5 6 Fully

agree 1. Short stories can motivate students to read

from the beginning to the end.

0 0 1 0 1 7

2. Reading several short stories will generate more reading practice than reading one novel.

1 1 2 2 3 0

3. Short stories have more benefits than simplified novels/graded readers.

0 0 2 0 3 3

4. It is easy to find short stories that are appropriate for my students’ level of language proficiency.

0 1 2 2 2 2

5. Short stories are perfect for students who have English as their third or fourth language.

0 1 2 4 0 2

6. I can let my students find a suitable short story on their own.

1 5 2 0 1 0

7. It is better to use a short story than an excerpt from a novel.

0 1 0 2 4 2

8. Short stories are easy to use when I want to illustrate the structure of a story.

To see trends and connections in how the informants answered, the results from this section of the questionnaire were merged into groups of three (1–2 disagree with the statement, 3–4 neither agree nor disagree with the statement, and 5–6 agree with the statement) which are presented in eight graphs and sorted according to the extent to which the informants agreed with the statement.

Eight out of nine informants agreed with the statements that “short stories can motivate students to read from the beginning to the end” and that “short stories are easy to use when I want to illustrate the structure of a story”. The figures show that to the first statement, the ninth informant neither agrees nor disagrees with the statement (figure 5) and figure 6 shows that the ninth informant disagreed with the statement that “Short stories are easy to use when I want to illustrate the structure of a story”. In other words, the statement that “short stories can motivate students to read from the beginning to the end” is the statement to which most of the informants agreed to.

Figure 5 - Short stories can motivate students to read from the beginning to the end

Figure 6 – Short stories are easy to use when I want to illustrate the structure of a story

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

1-2 disagree 3-4 neither agree nor disagree 5 - 6 agree

Nu m b er o f in fo rm an ts Combined answers 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

1-2 disagree 3-4 neither agree nor disagree 5 - 6 agree

Nu m b er o f in fo rm an ts Combined answers

There were four statements to which six out of nine informants have answered similarly. The first statement was “short stories have more benefits than simplified novels/graded readers” to which six informants answered that they agreed with the statement and two agreed somewhat (figure 7). One informant chose not to take a stance to this statement. Since no informant chose to disagree with this statement, the results indicate that all the informants somewhat agree with that short stories have more benefits than simplified novels/graded readers.

Figure 7 – Short stories have more benefits than simplified novels/graded readers

Figures 8 and 9 show that the informants had answered the same that “short stories are perfect for students who have English as their third or fourth language” and “it is better to use a short story than an excerpt from a novel”. Six informants had chosen that they neither agreed nor disagreed with the statements, two agreed and one disagreed. This shows that the majority of the informants neither disagreed nor agreed with the statements.

Figure 8 – Short stories are perfect for students who have English as their third or fourth language

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

1-2 disagree 3-4 neither agree nor disagree 5 - 6 agree no answer Nu m b er o f in fo rm an ts Combined answers 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

1-2 disagree 3-4 neither agree nor disagree 5-6 agree

Nu m b er o f in fo rm an ts Combined answers

Figure 9 – It is better to use a short story than an excerpt from a novel

The last statement to which six of nine informants answered the same was to the statement that “I can let my students find a suitable short story on their own”. This is the only statement with which the majority of the informants disagreed (figure 10). There was only one

informant that agreed with the statement, indicating that teachers, in general, have no confidence in the students’ ability to choose an appropriate short story for their level of language proficiency.

Figure 10 – I can let my students find a suitable short story on their own

Figures 11 and 12 show that the informants neither agreed nor disagreed with the statements “reading several short stories will generate more reading practice than reading a novel” and “it is easy to find short stories that are appropriate for my students’ level of language proficiency”. These figures show that there is a spread of the teachers’ attitudes to these statements. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

1-2 disagree 3-4 neither agree nor disagree 5 - 6 agree

N umb er of in for ma nts Combined answers 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

1-2 disagree 3-4 neither agree nor disagree 5 - 6 agree

Nu m b er o f in fo rm an ts Combined answers

Figure 11 - Reading several short stories will generate more reading practice than reading a novel

Figure 12 – It is easy to find short stories that are appropriate for my students' level of language proficiency

4.2.3 The choice between short stories and simplified novels/graded readers

In section 4.1.1, figure 1 showed that only three informants had used simplified novels/graded readers in one or more of their EFL classes. However, if they had to choose between short stories and graded readers the results would look differently. This question was asked to determine if the informants would prefer one form of text over the other, and they were also asked to give their reasons. All informants answered that they would choose short stories, though four informants did not motivate why. One of the female informants, who had been working for 16–20 years, commented:

I prefer short stories. My aim is to teach the students to cope with authentic English. A shorter text can be dealt with in detail and, when doing just that, I can push the students up to this more anvanced [sic] level. If we, on the other hand, were reading easy readers, students can manage more on their own, and they might learn to enjoy reading, but they do not meet the type of language that they are expected to cope 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

1-2 disagree 3-4 neither agree nor disagree 5-6 agree

Nu m b er o f in fo rm an ts Combined answers 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

1-2 disagree 3-4 neither agree nor disagree 5-6 agree

Nu m b er o f in fo rm an ts Combined answers

with. Simplifying is not the way (generally speaking). We should push our students instead (within reasonable limits of course).

This comment partly reflects this teacher’s opinion on texts in general and on the goal of using literature. More specifically, however, she also stated that there could be benefits with graded readers but that having to use simplified text is not the way to develop the students’ language skills. We can find a similar point of view in the comment by a female teacher with 6–10 years of teaching experience, who had written: “Short stories because they keep the students’ attention better and there are so many free sources available”. These claims further confirm the participating teachers’ view, reflected in figure 5 in the previous section, that short stories can motivate students to read from the beginning to the end.

Several informants confirmed what they had answered earlier in the survey, regarding

working with literature. One teacher wrote, “Short stories, I prefer texts in their 'raw' form for clarity and enhance [sic] students' vocabulary”. This statement gives us an idea of the

informants’ opinion regarding graded readers, which will be discussed further in section 5. A similar point of view is expressed by one informant who has been teaching for 26–30 years. She wrote, “In that case I choose to work with short stories because of the better quality and variety of vocabulary”. This comment confirms what many of the informants answered earlier regarding using short stories to expand students’ vocabulary (see figure 2). In fact, this comment came from one of the three informants that had used graded readers in one or more of their English classes. Another one of those three informants wrote, “I prefer short stories, for linguistic reasons as well as the better situation concerning

interpretation/analysis”. The third informant that had used graded readers was the male teacher who had been teaching for over 31 years. He did not motivate his answer that he would choose short stories over graded readers.

Another perspective was offered by a teacher that indicated that he preferred another form of literature. This informant commented:

I have never used simplified novels. Have never really thought about doing so. So it would be A [referring to short stories]. But I have also not had an easy time finding great short stories that my students like. I prefer novels, such as modern classics or teen classics.

This last comment indicates that if the informants could freely choose any literary form instead of having to choose between only the two that were specified, the results would look different.

4.3 Summary of the results

All the participating informants had worked with short stories in their English classes and saw them as useful tools in the EFL classes, for example, to develop the students’ reading skills, expanding their vocabulary, and developing their writing skills. After working with short stories, the teachers preferred to use combined examination methods such as an oral discussion with a written test.

There is a generally positive attitude towards short stories. However, some informants also pointed to difficulties regarding finding stories that are suitable for the students’ language level or texts that the students find interesting enough to read from the beginning to the end. Even with some problems, all the informants would choose short stories over graded readers because short stories contain authentic English and can motivate their students to read from the beginning to the end.

5 Discussion

The discussion section is divided into two subsections, with a focus on the two research questions that were introduced in the introduction. Each subsection will discuss the results presented in section 4 in order to deliver a clear conclusion.

5.1 Discussion of the results from section 4.1: Literary forms, and how

short stories are taught

The first research question in this study was how do the participating upper secondary English teachers work with short stories. Figure 1 in section 4.1.1 illustrated that short stories and news articles were the most frequently used types of literature in the teachers’ EFL classes. This might be due to the fact that both these types of literature can be read and discussed during one lesson where the students can discuss the text and better understand what they had read together. This is similar to Yilmaz’s results which showed that reading and discussing a short story helped the students to better understand what the text was about (90). Arjmandi’s investigation showed that using short stories could help improve EFL learners’ vocabulary, which could explain why many participating teachers had used short stories to improve both students’ language skills and develop their vocabulary, as presented in figure 2.

The results showed that literature, as a multifaceted tool, gave the teachers possibilities to use different examination methods when they wanted to assess the students after they completed the assigned short story. The most popular methods were an oral examination combined with a written test, which is indicated in figure 3. This would suggest that the teachers used combinations of examination methods so that they could assess several language skills. The students both received input and produced output when reading and then discussing a short story. After the students completed a written test, the teacher could then assess their writing skills too. According to Parkinson and Reid Thomas, teachers should assess multiple language skills when teaching literature (150–152). They recommend that teachers should encourage their students to use all their language skills when working with literature.

This study has been unable to demonstrate how teachers’ work with literature from different literary epochs and their attitudes towards different literary epochs since the Swedish

curriculum indicates that both “contemporary and older literature” (Skolverket, 2011) should be used in the EFL classroom. Compared with Luukka’s investigation which showed that the majority of the informants in her study preferred to work with titles from the 20th and 21st century which might be an indication that many of the informants in this study used news articles in their EFL lessons, which might be due to the fact that the participating teachers are more interested in recent time and that their students might be more interested to read

something that is connected to their own time.

5.2 Discussion of the results from section 4.2: Upper secondary teachers’

attitudes towards short stories

The second aim of this study was to investigate what attitudes do the participating English teachers have towards short stories compared to graded readers. Although the current study is based on a small sample of participants, figure 4 in section 4.2.1 showed that a majority of the teachers used more short stories now in their EFL classes compared to when they first started as teachers. This might be because many of them had positive teaching experiences with their students using short stories. If so, it would be similar to Zeybek’s results, whose informants had indicated that short stories had more teacher-advantages such as teaching abstract relationships, presentation of the target culture, and presentation of the target language (35) and fewer problems, such as lack of students’ involvement and time management (33) compared to other literary forms such as novels (39). Even though Zeybek did not include

graded readers in her investigation, her result indicated that the teachers had a positive attitude towards short stories.

An interesting aspect regarding the three of my informants that had used graded readers in one or more of their EFL classes is that if they had to choose to work with short stories or graded readers, all of them would choose short stories. They stated that they rather used short stories because of their linguistic structure and vocabulary, which would give the EFL learners a more authentic input of the English language. It has been suggested by Waring that graded readers with their simplified structure are used in a way that is similar to how parents talk to their young children so that they can acquire their first language. This does not appear to be a view shared by my informants, who suggested that Swedish adolescents at upper secondary school should read authentic literary texts, in order to further develop their language

proficiency.

One teacher informant, who had not used graded readers, commented that when “[…] reading easy readers, students can manage more on their own, and they might learn to enjoy reading, but they do not meet the type of language that they are expected to cope with”. This teacher sees the potential in using graded readers as material to encourage students to enjoy reading, even if she has not used them in any of her EFL lessons. This is supported by Albay’s investigation suggesting that assigning a graded reader would give students reading

confidence (117), which my informant does not oppose. However, the informant also wrote that her general belief is that “Simplifying is not the way” to develop students’ language skills. Gillis-Furutaka’s investigation showed that simplifying does not give students the practice they need to develop their reading comprehension skills (16). Thus, it would be of more interest to use authentic text with good quality regardless of the length of the text. There was one informant that seemed to have trouble finding suitable short stories to use in his teaching as well as to encourage his student to read those he had found. He wrote that he preferred to work with “[…] novels, modern classics or teen classics”, indicating that short stories are not the preferred literary form for every EFL teachers at upper secondary school in Sweden. In other words, if the informants had been asked which type of literature they

6 Conclusion

This present study aimed to find out how do the participating upper secondary English teachers work with short stories and what attitudes do the participating English teachers have towards short stories compared to graded readers. It can be concluded that the teachers have used short stories to develop EFL students’ language skills and above all their reading skills. Short stories could motivate the students to read the texts from beginning to end while they experience authentic English at the same time. Most of the teachers preferred to combine an oral examination with other examination methods to assess several language skills, so this could be a model to follow for other EFL teachers as well.

The participating teachers had a positive attitude towards short stories and preferred them over graded readers because of the former feature more advanced linguistic structures and vocabulary. Therefore, short stories will give students an input of authentic English. Further research might explore if Swedish adolescents at upper secondary school have developed their language skills when they had read graded readers, the students' attitudes towards the literary form and how the texts have been taught by upper secondary EFL teachers.

Works cited

Albay, Mustafa. “The Benefits of Graded Reading.” International Journal of Social Sciences & Educational Studies, vol. 3, no. 4, Ishik University, 2017, pp. 177–180,

doi:10.23918/ijsses.v3i4p177.

Arjmandi, Aladini. “Improving EFL Learners’ Vocabulary Learning Through Short Story Oriented Strategy (SSOS).” Theory and Practice in Language Studies, vol. 10, no. 7, July 2020, pp. 833–841, doi:10.17507/tpls.1007.16.

Bobkina, Dominguez. “The Use of Literature and Literary Texts in the EFL Classroom; Between Consensus and Controversy.” International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature, vol. 3, no. 2, Feb. 2014, pp. 249–260,

doi:10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.3n.2p.248.

Dahl, Christoffer. “Skönlitteratur i alla ämnen främjar lärande” Swedish National Agency for Education, Aug 29 2016

https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/forskning-och-utvarderingar/forskning/skonlitteratur-i-alla-amnen-framjar-larande Accessed 18

November 2020.

Dawson, Nick. “Penguin Readers Teacher's Guide to Using Graded Readers.” Pearson Education Limited in Association with Penguin Books Ltd., 2000.

Erkaya, Odilea. “Benefits of Using Short Stories in the EFL Context.” Asian EFL Journal (Busan) vol. 8, 2005 pp 1–13.

Edsman, Martina. ”A Choice in Reading: A Study of Student Motivation for Studying English Literature in Upper Secondary Schools in Sweden” Undergraduate thesis. University of Gävle. Faculty of Education and Business Studies. Department of Educational Sciences. 2019. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:hig:diva-30689

Ekehult, Mikaela. “Using Simplified Versions of Literary Classics in the Language

Classroom: A Case Study of the Penguin Readers Version of John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men.” Undergraduate thesis. Mälardalen University Sweden. School of Education, Culture, and Communication. 2013.

Falk, Linnéa. “Literature, a Gateway to New Worlds Encouraging: Aesthetic Reading through Transactional, Reader Response, and Envisionment Theories and Methods.”

Undergraduate thesis. Linnæus University. 2015. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:lnu:diva-46434

Forskningsetiska principer inom humanistisk-samhällsvetenskaplig forskning. Swedish Research Council, (2002). ISBN:91-7307-008-4

Ghosn, Irma-Kaarina. Storybridge to Second Language Literacy – the theory, research, and practice of teaching English with children's literature, Information Age Publishing, Incorporated, 2013. ProQuest Ebook Central,

https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/malardalen-ebooks/detail.action?docID=3315914.

Gillis-Furutaka, Amanda. “Graded Reader Readability: Some Overlooked Aspects.” Journal of Extensive Reading, vol. 3, no. 1, 2015, pp. 1–19., doi:http://jalt-publications.org/jer/. Hultberg, Anna. “Så får du elever att läsa klassiker” Ämnesläraren, April 1 2020

https://www.lararen.se/amneslararen-svenska-sprak/svenska-so-sprak/sa-far-du-eleverna-att-lasa-klassiker Accessed 15 November 2020. Web.

Krulatz, Steen-Olsen. “Towards Critical Cultural and Linguistic Awareness in Language Classrooms in Norway: Fostering Respect for Diversity through Identity Texts.” Language Teaching Research : LTR, vol. 22, no. 5, Sept. 2018, pp. 552–69,

doi:10.1177/1362168817718572.

Luukka, Emilia. “Selection, Frequency, and Functions of Literary Texts in Finnish General Upper-Secondary EFL Education.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, vol. 63, no. 2, Feb. 2019, pp. 198–213, doi:10.1080/00313831.2017.1336476.

Martinsson, Bengt-Göran “Därför läser vi skönlitteratur.” Perspektiv på

Litteraturundervisningen. 2016. (5) Swedish National Agency for Education. Parkinson, Brian & Reid Thomas, Helen. Teaching literature in a second language,

Edinburgh Univ. Pr, 2000, doi:10.3366/j.ctvxcrv20.

Skolverket. (2011). Ämnesplaner i gymnasieskolan, på engelska – Engelska. Stockholm. Retrieved from https://www.skolverket.se/undervisning/gymnasieskolan/laroplan-

Swedish Media Council. ”Unga och Medier” 2019. Stockholm ISSN 2001 – 6480

Tso, Anna. “Teaching Short Stories to Students of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) at Tertiary Level.” The Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, vol. 10, no. 1, Apr. 2014, pp. 111–17.

Waring, Rob. “Writing a Graded Reader.” Extensive Reading Central, 2003,

www.er-central.com/authors/writing-a-graded-reader/writing-graded-readers-rob-waring/.

Accessed: 16 October 2020

Yilmaz, Cevdet. “Introducing Literature to an EFL Classroom: Teacher’s Instructional Methods and Students’ Attitudes Toward the Study of Literature.” English Language Teaching (Toronto), vol. 5, no. 1, 2012, p. 86–99, doi:10.5539/elt.v5n1p86.

Zeybek, Gülin. “Turkish Pre-Service EFL Teachers’ Views on Integrating Various Literary Genres in Teaching English.” Language Teaching and Educational Research, vol. 1, no. 1, 2018, pp. 25–41.

Appendix 1 – The structure of the questionnaire

Hello. My name is Anton Engwers. I am a teacher student at Mälardalen University. At the moment, I am writing my degree project in English and the purpose of this survey is to collect the data that is needed for my analysis. want to investigate out how English teachers at

Swedish upper secondary school work with short stories in their English courses, which literary genres are used in Swedish upper secondary school, and what are teachers’ attitudes towards short stories compared to simplified novels/graded readers.

I would appreciate you taking the time to complete the following survey. You will be

anonymous, and your participation is optional. Responses will not be identified by individual. All responses will be compiled together and analysed as a group.

There are 13 questions/statements divided into four sections. Some questions/statements have a comment field. Please take a moment to give a short comment connected to the

question/statement.

If you have any questions or concerns, you are welcome to contact me.

Thank you for your participation.

Anton Engwers

xxxxxxxx@student.mdh.se xxx – xx xx xxx

Part 1

1. Choose your definition. I am:

o Male o Female o Other

2. For how many years have you been working as a teacher?

o 1 – 5 year(s) o 6 – 10 years o 11 – 15 years

o 16 – 20 years o 21 – 25 years o 26 – 30 years o Over 31 years

3. Which program(s) do you teach? More than one answer is possible.

o Theoretical program o Vocational program

4. Which English course(s) are you currently teaching? More than one answer is

possible.

o English 5 o English 6 o English 7

5. Have you used any of the following types of literature in your English classes? More

than one answer is possible. o Novels

o Short stories

o Simplified novels/graded readers o Poems o Dramas/plays o News articles o Comic books o Songs/lyrics o Children’s literature

o Other genres, please specify in the comment field. • Comment field

6. In which English class(es) have you used short stories? More than one answer is

possible.

o In English 5 classes. o In English 6 classes. o In English 7 classes.

o I have not used short stories in any of my English classes.

Part 2

If you answered, "I have not used short stories in any of my English classes.", in the previous question, read the instructions below. Otherwise, please continue.

Since you have chosen the alternative, “I have not used short stories in any of my English classes.”, you do not have to participate further in this survey. If you like to change your answer, press "Back". Otherwise, thank you for your participation. You have been most helpful. Press "Next" to get to the end of the survey and submit your answers.

Also, would it possible to contact you for a further interview? This is, of course, optional. If yes, please enter your email address at the end of the survey.

The up-coming questions will focus on teachers’ attitude to short stories and how they work with short stories in their English classes.

Part 3

This section contains eight statements regarding your attitude towards short stories.

7. What is your attitude to short stories?

o Short stories can motivate students to read from the beginning to the end. 1 (disagree) --- 2 --- 3 --- 4 --- 5 --- 6 (fully agree)

o Reading several short stories will generate more reading practice than reading one novel.

1 (disagree) --- 2 --- 3 --- 4 --- 5 --- 6 (fully agree)

o Short stories have more benefits than simplified novels/graded readers. 1 (disagree) --- 2 --- 3 --- 4 --- 5 --- 6 (fully agree)

o It is easy to find short stories that are appropriate for my students’ level of language proficiency.

1 (disagree) --- 2 --- 3 --- 4 --- 5 --- 6 (fully agree)

o Short stories are perfect for students who have English as their third or fourth language.

1 (disagree) --- 2 --- 3 --- 4 --- 5 --- 6 (fully agree)

o I can let my students find a suitable short story on their own. 1 (disagree) --- 2 --- 3 --- 4 --- 5 --- 6 (fully agree)

o It is better to use a short story than a text excerpt from a novel. 1 (disagree) --- 2 --- 3 --- 4 --- 5 --- 6 (fully agree)

o Short stories are easy to use when I want to illustrate the structure of a story. 1 (disagree) --- 2 --- 3 --- 4 --- 5 --- 6 (fully agree)

Part 4

8. I have used short stories for the following reasons. More than one answer is possible.

o To develop my students’ reading skills. o To develop my students’ writing skills.

o To read aloud to develop with my students’ listening skills. o To read aloud for other purposes.

o To teach about literary terms. For example, round character, turning point, in medias res, rising action, intertextuality et cetera.

o In combination with a video clip, with a similar theme.

o To demonstrate different English dialects/variations in written form.

o To give my students an understanding of different cultures where English is used.

o To prepare my students for the Swedish National Test. o Other reasons, please specify in the comment field.

• Comment field

9. What is your preferred method for examination after you and your students have

worked with short stories? Choose one answer.

o Oral (discussion groups/full class, oral presentation et cetera.). o Book report/essay.

o A written test where the students must answer questions connected to the short story.

o A combination of a) and b). o A combination of a) and c). o A combination of b) and c). o A combination of a), b) and c).

o Something else. Please specify in the comment field. • Comment field

10. If you have to choose, would you use a) short stories or b) simplified novels/graded

readers in your English classes? Please, motivate your answer. • Comment field

11. Are you using more, or fewer short stories now compared with when you first started

as a teacher? o More. o Fewer.

o I do not know.

o I have nothing to compare to. • Comment field

12. Could you please mention some titles of short stories that you have used, regardless of

what sort of assignment? • Comment field

13. Would it possible to contact you for a further interview? This is, of course, optional. If