0

The management of family firms: supportive work-family

culture and work-family conflict in Sweden

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration - Management NUMBER OF CREDIT: 30 ETCS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Civilekonomprogrammet AUTHORS: Elisa Baker & Emma Johansson

1

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our genuine appreciation to several individuals who have supported us throughout this course.

Firstly, we would like to express our gratitude to all participants in our study that contributed with their experience and knowledge. We also want to thank the CeFEO - Centre for Family Entrepreneurship and Ownership at Jönköping university for the feedback and guidance.

Secondly, we want to thank the individuals in our seminar group that have given us constructive feedback and comments throughout the process.

Finally, we wish to give an extra recognition and acknowledgement to our tutor Elvira Ruiz Kaneberg for devoting time and engagement in sharing her knowledge and giving us the

feedback necessary for completing this study.

Without all these contributions, it would not be possible to carry out the study.

From Author Elisa Baker:

I would like to dedicate a few words and special appreciation to my partner Mohamed for the never-ending support and continuous encouragement. Thank you!

Elisa Baker Emma Johansson

0

Master Thesis in Business Administration – Management

Title: The management of family firms: supportive family culture and work-family conflict in Sweden

Authors: Elisa Baker & Emma Johansson

Tutor: Elvira Ruiz Kaneberg

Key terms: Family business, Small and medium-sized enterprise (SME), Boundary management

______________________________________________________________________________

Abstract

The management of work-family conflict is an important aspect within the context of family firms. Managing work and family domains successfully are often known to be an issue for members of family firms and may result in negative outcomes affecting both individuals and organisations. Organisational cultures supporting individuals in managing work and family domains is believed to reduce the level of work-family conflict and constitutes the focus of this study.

Historically, most of the scholarly contributions within the field of work-family conflict and organisational culture are within a non-family firm context. This thesis contributed to current literature with in-depth insights on the family business concepts by relating it with work-family conflicts. Family firms possess unique characteristics that are different from non-family firms, making the management of work-family conflict more difficult. The study shows that the relationships between the components of supportive work-family culture and work-family conflict are factors that impede individuals’ ability to manage multiple roles satisfactorily. The findings of this study could be used to contribute understanding in future research within the field of family firms and in connection to the management of work-family conflicts.

1

Table of content

1. Introduction ... 3 1.1 Background ... 4 1.2 Problem statement ... 5 1.3 Research purpose ... 7 1.4 Research questions ... 7 1.5 Delimitations ... 71.6 Definitions of key terms ... 8

2. Literature Review ... 9

2.1 The management of family firms ... 9

2.1.2 Family-owned small and medium-sized enterprises ... 10

2.2 Work-family conflict ... 11

2.2.1 Dimensions of work-family conflict ... 12

2.2.2 Three types of work-family conflict ... 12

2.2.3 Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict ... 13

2.2.4 Work-family conflict in family firms... 14

2.3 Organisational culture in family firms ... 16

2.3.1 Defining culture ... 16

2.3.2 Organisational culture ... 17

2.3.3 Organisational culture in family firms ... 18

2.3.4 Supportive work-family culture ... 19

2.3.5 Three components of supportive work-family culture ... 19

2.4 Boundary management ... 22

2.5 Summary: the hypotheses related to the family business theory ... 25

3. Methodology ... 26 3.1 Research philosophy ... 26 3.2 Research approach ... 27 3.3 Methodological choice ... 28 3.4 Research strategy ... 28 3.5 Time horizon ... 28

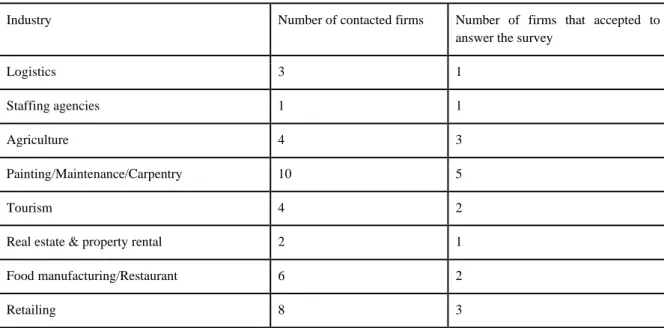

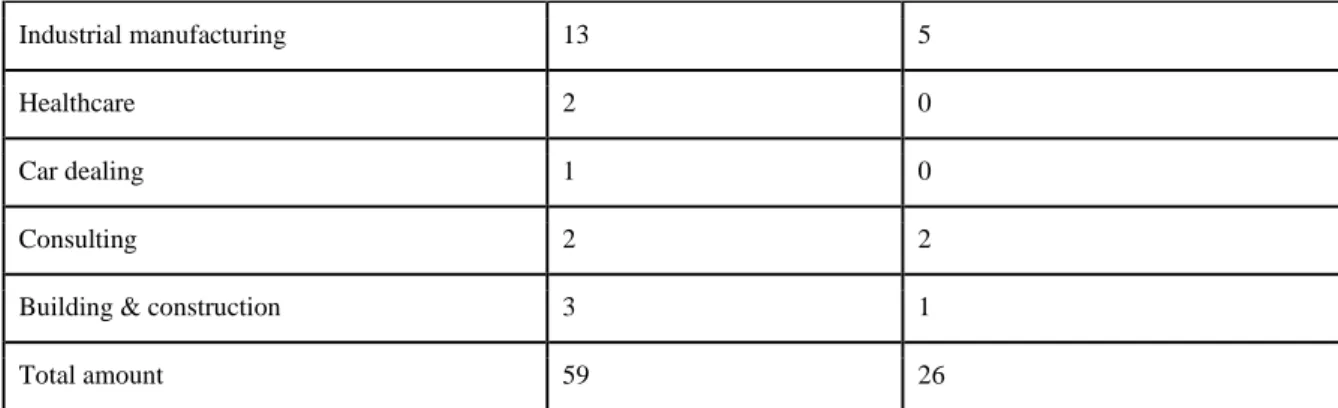

3.6 Participant selection and sampling techniques ... 28

3.6.1 Sample characteristics ... 31 3.7 Data collection ... 31 3.8 Questionnaire design ... 32 3.9 Measures ... 33 3.9.1 Dependent variables. ... 33 3.9.2 Independent variables ... 34 3.9.3 Control variables ... 35 3.10 Pilot testing ... 35 3.11 Data analysis ... 35

3.11.1 Data Entry, coding, and cleaning ... 36

3.12 Quality of survey ... 37

3.13 Quality of research ... 38

2

4. Empirical results ... 41

4.1 Descriptive statistics ... 41

4.1.1 Descriptive statistics for categorical variables ... 41

4.1.2 Descriptive statistics for continuous variables ... 43

4.2 Correlation analysis ... 45

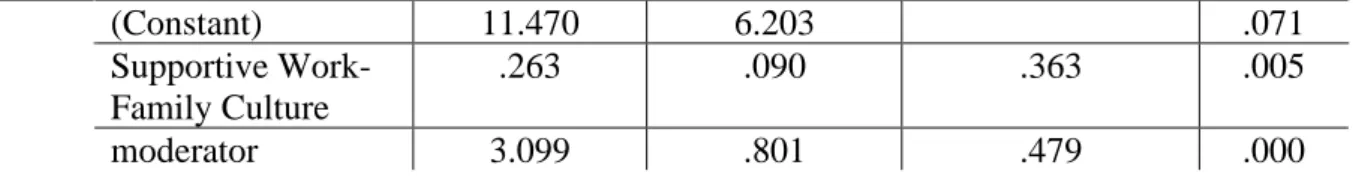

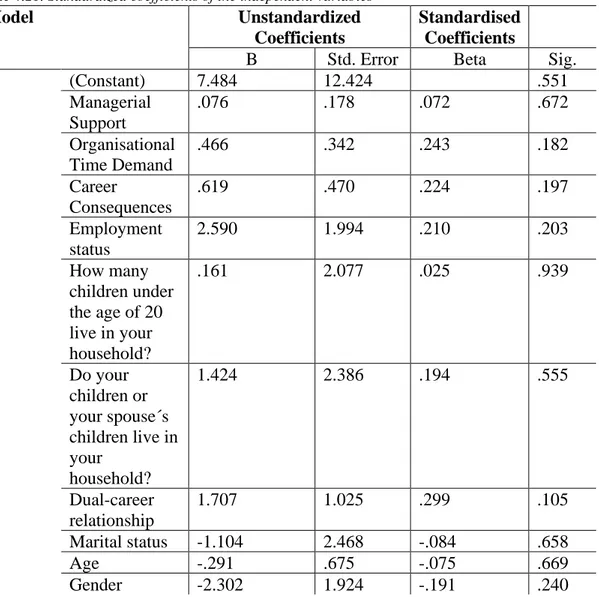

4.3 Multiple regression model ... 50

5. Analysis ... 53

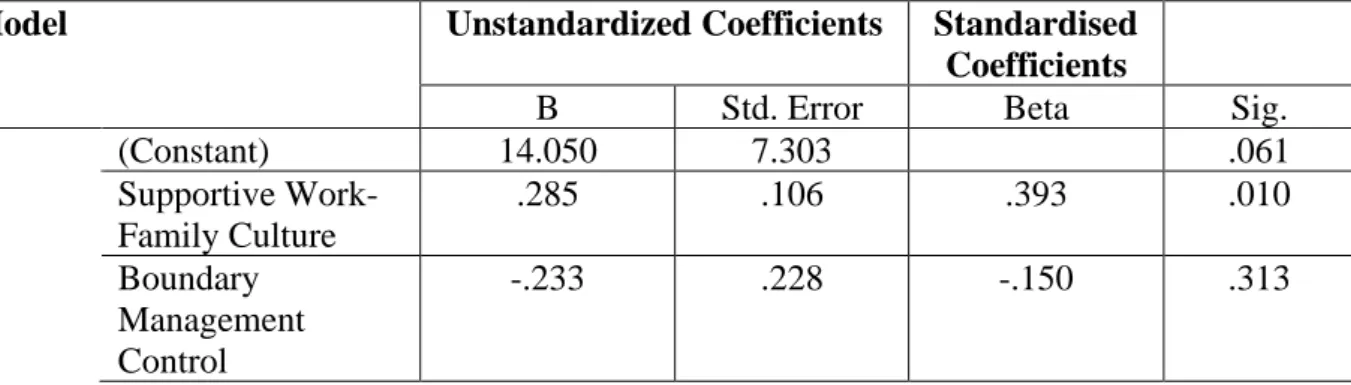

5.1 Analysis related to hypotheses 1 ... 53

5.2. Analysis related to hypothesis 2 ... 55

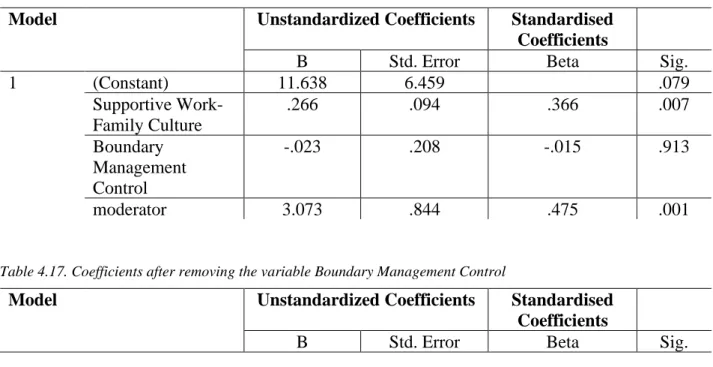

5.3. Analysis related to hypothesis 3 ... 56

5.4. Analysis related to hypothesis 4 ... 58

5.5. Analysis related to hypothesis 5 ... 59

6. Conclusion and discussion ... 61

6.2 Implications ... 63 6.2.1 Theoretical implications ... 63 6.2.2 Managerial implications ... 63 6.2.3 Ethical implications ... 64 6.3 Limitations ... 64 6.4 Future research ... 65 List of references ... 66 Appendices ... 75 Appendix 1 ... 75 Appendix 2 ... 80 Appendix 3 ... 81 Appendix 4 ... 82 Appendix 5 ... 83 Appendix 6 ... 85 Appendix 7 ... 86 Appendix 8 ... 87

3

1. Introduction

_____________________________________________________________________________________

This chapter will introduce the topic of this thesis. First, the chapter presents a short introduction followed by background information and research problem of the topic. Further, the purpose is defined together with the research questions. Lastly, there is a section with delimitations and key definitions.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Work and family are the two most dominating domains in working individuals’ lives (Medina-Garrido, Biedma-Ferrer & Ramos-Rodríguez, 2017). Successfully balancing these two domains has been and still is a challenge for many employees (Parasuraman & Simmers, 2001). The interest among scholars in examining this relationship and its potential outcomes and antecedents has grown during the last decades (Allen et al., 2000; Brough & Kalliath, 2009; Edwards & Rothbard, 2000; Ferguson et al., 2012; Powell, Francesco & Ling, 2009; Greenhaus & Powell, 2006; Ruizalba et al., 2016; Wayne & Casper, 2016). The growing interest has emerged from changes in families and the workforce, such as increases in the number of single parents, women in the workforce, dual-career couples, and fathers taking parental leave (Allen et al., 2000; Clark, 2001; Edwards & Rothbard, 2000; Frone 2003; Powell et al., 2009; Greenhaus & Powell, 2006; Hirschi, Shockley & Zacher, 2019; Moshavi & Koch, 2005). These changes have resulted in more individuals participating in both work and non-work roles, and when expectations, responsibilities, and demands from work and home collide, conflict occurs (Medina-Garrido et al., 2017). This conflict is common among all working individuals, but scholars have suggested that it may pose an even bigger challenge and issue for individuals working in family firms (Ruizalba et al., 2016; Moshavi & Koch, 2015), who often experience difficulties separating work and family roles (Stafford & Tews, 2009).

Organisational culture has proven to be of great importance for employees’ experience of work-family conflict. Scholars have argued that a supportive work-work-family culture is essential for lowering employees’ level of work-family conflict, and to enable them to balance work and family roles successfully (Thompson, Beauvais, & Lyness, 1999: Allen, 2001: Anderson, Coffey & Byerly, 2002). Such cultures are also believed to enable employees to enact a boundary management style that fits their boundary preferences for balancing multiple roles. This fit between style and preference is referred to as boundary management control, which is important for organisations since it is associated with lower levels of work-family conflict (Kossek & Lautsch, 2012).

4

1.1 Background

The conflict between work and family roles has by far been the most researched area within the management of work and family domains. Two dominating concepts have emerged from previous research within the field: work-family conflict and family-work conflict. Work-family conflict implies that the conflict resides in the work domain and that work interferes with family (Medina-Garrido et al., 2017), while family-work conflict implies that it resides in the family domain (Frone, 2003; Lambert et al., 2006). Most research has been conducted within the work-family context, which also is the direction of a conflict that according to scholars is the most common type of conflict (Frone, 2003). Two of the most known and cited authors within the field are Greenhaus and Beutell (1985) who identified three types of work-family conflict: time-based conflict, strain-based conflict, and behaviour-strain-based conflict (Rothausen, 2009: Anderson et al, 2002).

Organisational culture is often regarded as a key for organisational growth, success, effectiveness, and competitive advantage (Cherchem, 2017). But it may also affect the level of work-family conflict that employees in a firm experience since it is considered as important for the development and implementation of work-family friendly programs and policies (Allen, 2001). Many scholars have argued that a supportive work-family culture that offers flexibility, tolerance and support for family obligations are directly related to the level of work-family conflict (Thompson et al., 1999: Allen, 2001: Anderson et al., 2002). Thompson et al. (1999) identified three components of a supportive work-family culture: organisational time demand, perceived career consequences, and managerial support. It is generally suggested that such cultures decrease the perception of work-family conflict (Fiksenbaum, 2014).

Family firms offer unique characteristics that distinguish them from non-family firms (Ruizalba et al., 2016; Boles, 1996). It is widely known that members of family firms often face difficulties in separating work and family roles due to its high level of integration between family and business (Stafford & Tews, 2009). This makes work-family conflict a complex but relevant topic within the context of family firms (Ruizalba et al., 2016; Moshavi & Koch, 2015). What further complicates the issue is the fact that family firms often employ both family employees and non-family employees (Moshavi & Koch, 2015). Some scholars have argued that non-family employees experience less personal advantage in family firms compared to family employees (Beehr, Drexler, Jr., & Faulkner, 1997).

Research has suggested that one explanation for this is because the organisational culture of family firms often is built upon the values of the founder (Denison, Lief & Ward, 2004; Zahra, Hayton, &

5

Salvato, 2004; Hall, Melin, & Nordqvist, 2001) who often also is a family member of the firm. Therefore, it is likely that the organisational cultures of family firms benefit family employees more than non-family employees. One concept that has been used by scholars to understand how individuals are affected by organisational cultures is boundary theory. It has been used to understand how individuals manage multiple roles by creating and maintaining boundaries (Piszczek, DeArmond, & Feinauer, 2018; Ashforth, Kreiner, & Fugate, 2000). Individuals hold different boundary preferences (Ashforth et al., 2000), and according to Piszczek et al. (2018), family employee’s preferences often differ from the preferences held by non-family employees. Kossek and Lautsch (2012) argued that the most effective organisational culture for reducing the level of work-family conflict considering different boundary preferences is a culture that enables employees to enact a boundary management style that fits their boundary preference. This will lead to boundary management control which is associated with lower levels of work-family conflict.

Sweden offers an interesting area for investigating work-family conflicts in the context of family firms since they are Sweden’s largest source of income. Family firms account for around one-third of Swedish employment and GDP and is the most common form of organisation in Sweden covering almost 90 per cent of all employing companies. Furthermore, according to Annink, den Dulk and Steijn (2016), Sweden reports high levels of experienced work-family conflict. This is supported by Lippe et al. (2006) who also reported that Sweden is the country in EU that reports the highest level of pressure from combining work with family. Despite this theme’s importance on family business performance, limited research exists regarding the work-family conflict in the Swedish context. The current literature mainly examines the work-family conflict from the perspectives of working fathers (Allard, Haas & Hwang, 2011), managerial fathers (Allard, Haas & Hwang, 2007), teachers (Richter et al., 2015), and nurses in Sweden (Leineweber et al., 2014). None or very limited, research has been conducted examining work-family conflict in Swedish family firms. Considering family firms importance for the Swedish economy and the high reported levels of work-family conflict in Sweden, it provides an interesting area for research.

1.2 Problem statement

Much of the effort in studying family firms have been devoted to the challenges caused by work-family conflict. A large amount of research has concluded that work-work-family conflict impact organisations and employees in an often negative way (Rothausen, 2009; Anderson et al., 2002; Parasurman & Simmers, 2001). Cultures that support employees in the management of work-family roles also referred to as supportive work-work-family cultures, have been suggested to reduce the

6

level of work-family conflict in businesses (Thompson et al., 1999: Allen, 2001; Fiksenbaum, 2014; Anderson et al., 2002). However, the literature that does exist regarding the relationship between a supportive work-family culture and work-family conflict investigate it in a non-family firm context. To our best knowledge, no research exists regarding the level of impact that supportive work-family cultures have on employee’s level of work-family conflict within the context of family firms. This implies that there is a gap in the literature whether the components of a supportive work-family culture show similar relationships to the work-family conflict in family firms as it has shown in non-family firms. Karofsky et al. (2001) and Smyrnios et al. (2003) suggested that work-family conflict models also apply to family businesses and their members. Thus, we could expect to see the same relationship within family firms as has been seen in non-family firms. However, there is no evidence supporting this assumption. Therefore, there is a need for investigating the relevance of previous research in the context of family firms.

Furthermore, even though family firms often employ both family employees and non-family employees, non-family employees have previously often been neglected in studies of family firms (Moshavi & Koch, 2005). This is a major problem for family firms since non-family employees often represent a large proportion of the firm's human capital (Ployhart, van Iddekinge & MacKenzie, 2011). Family firms are highly dependent on their human capital for performance and long-term survival (Rothausen, 2009), thus, enabling both non-family employees and family employees to manage work and family domains successfully is essential. Nevertheless, no research has suggested how family firms may achieve this. Supportive work-family cultures are suggested to reduce the level of work-family conflict (Thompson et al., 1999), but there is a gap in the literature whether this relationship holds for both family employees and non-family employees. According to Kossek and Lautsch (2012), organisational cultures can reduce individuals’ level of work-family conflict when it enables them to perceive boundary management control. Supportive work-family cultures are strongly associated with the perception of such control (Kossek & Lautsch, 2012). However, no literature has proven that supportive work-family cultures support both family employees and non-family employees in perceiving boundary management control. Therefore, there is a gap in the literature whether a supportive work-family culture supports both family employees and non-family employees in achieving such control.

7

1.3 Research purpose

The purpose of this study is to examine the management of family firms, specifically, the work-family conflict and the supportive work-work-family cultures in small and medium-sized firms in the context of Sweden.

1.4 Research questions

RQ1. What is the relationship between a supportive work-family culture and work-family conflict in family-owned small and medium-sized firms?

RQ2. How is the perception of boundary management control affected by supportive work-family cultures in work-family-owned small and medium-sized firms, and how does it affect the relationship between a supportive work-family culture and work-family conflict?

1.5 Delimitations

Firstly, this thesis will focus on work-family conflict and not include any aspects of the family-work conflict. Since family-work-family conflict implies that the conflict resides in the family-work domain (Frone, 2003; Lambert et al., 2006), and organisational culture is part of the work-domain, it is more relevant to study work-family conflict when examining the effect of organisational culture on interrole conflict.

Secondly, the focus of this study is small and medium-sized family firms operating in Sweden. However, the study will only sample family firms operating in Småland county since the authors of this study live in Småland which makes it easier to reach out and keep close contact with the firms. Furthermore, the study is limited to small and medium-sized enterprises. This is because larger family firms may not hold as strong family firm characteristics as smaller family firms and may not exclusively be in control of the family. It is a higher likelihood that the ratio between family employees and non-family employees is more even in smaller family firms compared to larger family firms. Since this study includes both types of employees, focusing on small and medium-sized family firms decreases the likelihood of getting a much larger proportion of answers from non-family employees compared to family employees, which most likely would have been the case if studying large family firms.

8

1.6 Definitions of key terms

Supportive work-family culture: a supportive work-family culture refers to a culture that supports and values the integration of work and family dimensions among employees (Thompson et al., 1999).

Work-family conflict: A work-family conflict is a form of inter role conflict that occurs as participation in one role (e.g. work) conflicts with meeting demands and responsibilities of another role (e.g. family) (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985).

Family firm/business: a firm/business that is governed to form and pursue the vision of the business held by a dominant coalition controlled by members of the same family or a small number of families in a way that is potentially sustainable across generations of the family or families (Chua, Chrisman & Sharma, 1999).

Family employee: an employee working in a family business that also is a member of the family owning the business (Baker & Johansson, 2020)

Small and medium-sized enterprise (SME): a business that employs between 0-250 employees (European Commission, 2018).

Boundary management: the creation and maintenance of boundaries between multiple roles, that are based on personal needs and desires and shaped by cultural and institutional arrangements (Padhi & Pattnaik, 2017).

Boundary management control: this is achieved when individuals can enact a boundary management style that fits their boundary management preference (Kossek & Lautsch, 2012).

9

2. Literature Review

__________________________________________________________________________________

This chapter provides relevant literature related to this thesis. First, it offers a literary discussion concerning family firms, followed by relevant theoretical aspects about work-family conflict, culture, and supportive work-family culture in connection to boundary management and control. A presentation of the hypotheses and sum up conceptual model is provided.

__________________________________________________________________________________

2.1 The management of family firms

Family firms are by far the most common form of ownership and corporate structure throughout the world (Sekerci, 2018; Andersson, Karlsson & Poldahl, 2017; Gedajlovic et al., 2012; Jack et al., 2013). They play a key role in general economic development as it is estimated that 80-98 per cent of businesses worldwide are family firms (Gedajlovic et al., 2012; Sekerci, 2018; Ramadani & Hoy, 2015). Furthermore, they employ more than 75 per cent of the global workforce and generate around 75 per cent of the worlds gathered gross domestic product (GDP) (Ramadani & Hoy, 2015). For these reasons, their stability, prosperity, and health are important factors for generating new job opportunities and maintaining global financial growth they generate (Ramadani & Hoy, 2015).

Despite the significant role that family firms have for single nations as well as the global economy, the field of family business research is relatively new and emerging (Bird et al., 2002; Chrisman et al., 2008; Craig et al., 2009; Gedajlovic et al, 2012; Senftlechner & Hiebl, 2015). For these reasons, defining family firms are a somewhat complex task and a major challenge for researchers. There are however several distinguishing characteristics that differentiate them from non-family firms (Hiebl & Senftlechner, 2015). The definition adopted in this thesis is that family involvement, participation, and control - either in the form of ownership and/or management -, is distinguishing factors (Ramadani & Hoy, 2015; Bjuggren, Johansson & Sjögren, 2011).

The literature is in general unclear about what is meant by and included in the word ”family” when referring to the term family firm. For example, Sekercis (2018) definition of a family firm is that the firm assembles related family members to ownership coalitions. This covers a wide spectrum, as related family members can include everything from the closest family such as spouses, children, and siblings, to grandparents/grandchildren, or even cousins and aunts/uncles. Carsrud

10

(2006) broadens the spectrum, implying that family members should not be limited only to those sharing blood ties, but also include marriage ties. The definition we have decided to follow in this thesis when referring to the family is a combination of the two, implying that families are not only related by blood but also by marriage ties.

With all this in mind, it is worth remembering that family businesses come in all sizes. Most family businesses are small enterprises engaging only the closest family members, but medium- and large-size companies are also represented. Even publicly listed multinational companies are represented as family firms (Gedajlovic et al, 2012). These family businesses employ thousands of people ranging over several industries. Research, however, indicates that the characteristics that differentiate family businesses from non-family businesses are more noticeable when looking at smaller firms compared to large ones (Duller et al, 2013). Regardless of size, they are all to some extent influenced by the control exercised by the family, which makes them unique compared to non-family firms (Chua et al, 1999).

The most common form of corporate structure in Sweden is family businesses. There are roughly 410 000 family businesses in Sweden. This means they make up about 90 per cent of all companies within the country (Andersson et al, 2017). Of listed businesses worldwide, 34 per cent are family firms (Sekerci, 2018). Sweden thereby follows the international average where it is estimated that 35 per cent of listed firms are owned and managed by the family (Andersson et al, 2017). At least one-third of the workforce is employed by family firms and the GDP sourced from family firms within Sweden are estimated to be roughly a third of the total, making them Sweden’s largest source of income (Andersson et al, 2017).

2.1.2 Family-owned small and medium-sized enterprises

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are very important for economic growth globally (Singh, Garg & Deshmukh, 2008; Caliskan, Arikan & Saatci, 2014), and accounts for one-third of all businesses on a global scale (D´Angelo, Majocchi & Buck, 2016). SMEs are most often defined based on the number of employees (Caliskan et al., 2014; Singh et al., 2008; Ayyagari, Beck & Demirgüç-Kunt, 2003), but the definitions and measures can vary between countries (Ayyagari et al., 2003). According to the European Commission (2018) definition, SMEs are those employing between 0-250 employees. In Sweden, 99,9 per cent of all enterprises are SMEs.

Work-family conflict is according to Caliskan et al. (2014) one factor that can determine the success of SMEs. SMEs are more dependent on individual contributions from employees for success and long-term survival compared to larger organisations (Cegarra-Leiva, Sánchez-Vidal &

11

Cegarra-Nevarro, 2012). Work-family conflict has proven to harm employee’s job performance and satisfaction at work, therefore, managing work-family conflict becomes highly important for SMEs.

Family-owned SMEs are perhaps even more affected by work-family conflict than non-family-owned SMEs (Caliskan et al., 2014) since family firms in comparison are even more dependent on their human capital (Rothausen, 2009). Family-owned SMEs are the most common type of firm worldwide and accounts for approximately 85 per cent of all firms in the EU and USA (Kontinen & Ojala, 2012). In Sweden, approximately 87 per cent of all family firms are SMEs (Andersson et al., 2017).

2.2 Work-family conflict

Most working individuals have two dominating domains that often conflict with one another: work and family. Balancing and/or separating those two domains are easy for some but challenging for others. When expectations, responsibilities, and demands from work and home collide, conflict occurs. In academic terms, this conflict is often referred to as work-family conflict (WFC) (Medina-Garrido et al., 2017), and is according to Greenhaus, Collins and Shaw (2003) occurring when there is an imbalance between work and family. This conflict is believed to influence an individual’s quality of life (Lambert et al., 2006; Rothausen, 2009).

The most influential and cited model of work-family conflict is the model developed by Greenhaus and Beutell in 1985 (Rothausen, 2009). They defined work-family conflict as “a form of interrole conflict in which the role pressures from the work and family domains are mutually incompatible in some respect” (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985, p. 77). According to them, work and family are two separate roles that cannot be integrated. Participation in one domain is believed to conflict with participation in the other domain. This view has been supported by other authors who also argued that work and family are two separate, independent systems (Edwards & Rothbard, 2000; Rothausen 2009). The underlying concept that this theory of work-family conflict relies on is the assumptions of scarcity, origin in the Conservation of Resource (COR) model. This model states that individuals have a limited amount of resources (e.g. time and energy) that they can devote to different roles (Rothausen, 2009; Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985; Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). Devoting more resources to one domain (e.g. work) means that fewer resources can be devoted to the other domain (e.g. family). Moreover, it refers to the assumption that people strive to acquire, retain, and protect resources (Wayne et al., 2020), and that stress and strain are a result of individuals’ perception of losing resources. It suggests that negative outcomes of work-family

12

conflict are a result of resource depletion. Anything that drains resources (e.g. child or elderly care) will lead to higher levels of work-family conflict, and anything that can hinder this depletion of resources, such as supportive work-family programs, policies, and cultures, are associated with lower levels of work-family conflict (Premeaux, Adkins, & Mossholder, 2007). The scarcity model, in turn, is based on role theory (de Luis Carnicer, Sánchez, Pérez & Jiménez, 2004), which states that role conflict is a form of interrole conflict that occurs when individuals experience problems performing in multiple roles due to conflicting demands between roles (Allen et al, 2001). Scholars who base their assumptions on the scarcity model and role theory argue that individuals with multiple role responsibilities unavoidably experience conflict between the roles (Rothausen, 2009).

Some researchers have however criticized the use of role theory and COR model concering work-family conflict (de Luis Carnicer et al., 2004) and instead argued that multiple roles may also contribute with advantages that outweigh the disadvantages (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). These researchers have instead used the expansion model which states that participating in multiple roles provides individuals with alternative resources which offset the potential negative outcomes on well-being proposed by COR model and role theory (de Luis Carnicer et al., 2004).

2.2.1 Dimensions of work-family conflict

Two dimensions of the conflict have been identified by scholars: work-family conflict and family-work conflict. These imply that conflict can either reside in the family-work domain or the family domain (Frone, 2003; Lambert et al., 2006). According to Netemeyer, Boled, and McMurrian (1996, p. 401), work-family conflict is defined as “a form of interrole conflict in which the general demands of, time devoted to, and strain created by the job interfere with performing family-related responsibilities”. Family-work conflict is defined as “a form of interrole conflict in which the general demands of, time devoted to, and strain created by the family interfere with performing work-related responsibilities”. Anderson et al. (2002) argue that there is a clear distinction between work-family conflict and family-work conflict. According to them, each type of conflict is associated with different types of outcomes and antecedents. Most researchers however suggest that work-family conflict is more common than family-work conflict (Frone, 2003).

2.2.2 Three types of work-family conflict

Within the context of work-family conflict, Greenhaus and Beutell (1985) identified three types of work-family conflict: time-based conflict, strain-based conflict, and behaviour-based conflict. Time-based conflict refers to the conflict in which meeting demands in one domain steals time

13

from meeting demands of the other domain. Lambert et al. (2006) explained time-based conflict as when time at work interfere with responsibilities at home. Strain-based conflict refers to the situation where strain from one domain hinders the ability to meet the demands of the other domain (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). Another explanation is that strain-based conflict occurs when work causes stress that affects the individual's psychological and mental health which consequently affects the individual’s family life (Lambert et al., 2006). Smyrnios et al. (2003) identified three independent components of strain-based conflict: interrole conflict, after-hours worked, and business dissatisfaction. Interrole conflict occurs when pressure from one role conflict with demands coming from another role. After hours worked reflects the issue that many business owners often work after office hours, which then may lead to business dissatisfaction. However, the positive relationship between after-hours work and business dissatisfaction proposed by Smyrnios et al. (2003) was only significant for employees in non-family firms. The last type, behaviour-based conflict, refers to the situation in which behaviours from one domain are incompatible with role demands in the other domain, and the individual is incapable to adapt behaviour when moving between domains (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). According to Lambert et al. (2006), behaviour-based conflict can be divided into two subtypes: the first one is when work roles are inappropriate in family roles, and the second one is when family roles are inappropriate at work. Smyrnios et al. (2003) also talked about behaviour-based conflict by referring to it as a form of interrole conflict in which behavioural expectations in one role conflicts with behavioural expectations of another role. Overall, all three components of work-family conflict are associated with job dissatisfaction and lower family satisfaction (Smyrnios et al., 2003).

2.2.3 Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict

Previous research has explored the potential antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict (Frone, 2003; Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). Some researchers have focused more on the potential outcomes and effects of work-family conflicts, such as the level of job satisfaction, turnover intention, life satisfaction, psychological distress, and health outcomes (Rothausen, 2009: Anderson et al, 2002). Other researchers have instead focused on investigating the antecedents of work-family conflict, that is, what factors may cause work-family conflict to occur (Rothausen, 2009; Frone, 2003). Regarding antecedents, Frone (2003) argued that work-family conflict could be an outcome of behavioural involvement, psychological involvement, role-related stressors, and/or role-related resources. Jeffrey et al. (2003) found that individuals who devoted more time and involvement in the family domain compared to the work domain had the lowest level of work-family conflict. On the contrary, individuals devoting more time to work than work-family was shown

14

to have the highest level of work-family conflict. Clark (2001) suggested that dual-career parents, having many children, and working long hours at work were positively related to work-family conflict. This is further supported by Anderson et al. (2002) who also argued that certain types of family structures were associated with higher levels of work-family conflict. These structures were assumed to create excessive demands on the individual, resulting in work-family conflict. Regarding outcomes, Anderson et al. (2002) stated that work-family conflict is related to decreased job satisfaction, increased turnover intentions, and strain. Frone (2003) supports these arguments, adding lower performance at work as a potential outcome. Furthermore, he also argued that work-family conflict had negative outcomes in the work-family and personal domain as well, such as work-family dissatisfaction, family withdrawal, lower family performance, and poor mental and physical health.

The most common conclusion made by scholars is that participation in multiple roles leads to negative outcomes in the form of conflict. However, as noted, some researchers propose the opposite, stating that individuals participating in multiple roles can experience positive outcomes that outweigh the negative ones if certain factors are present. These factors include flexibility, support, recognition, reward, and autonomy (Rothausen, 2009). According to Rothausen (2009), what determines whether participation in multiple roles result in positive or negative outcomes is the quality of the roles and the support offered by the organisation. This is supported by other researchers who argue that a supportive work-family culture is important for reducing the risk of work-family conflict and increasing the possibility of positive outcomes (Grandey, Cordiero & Michael 2007; Allen, 2001; Fiksenbaum, 2014; Thompson et al., 1999; Wayne & Casper, 2016). Clark (2001) strengthened this argument by stating that a supportive work-family culture could allow employees opportunity to successfully manage role conflict. Additionally, it is assumed that supportive work-family cultures not only create positive outcomes in the work domain but also facilitate family outcomes (Rothausen, 2009).

2.2.4 Work-family conflict in family firms

In the context of family firms, limited research has been conducted regarding the level of overlap between the family and the business, and the potential conflict that may appear among family members due to this (Stafford & Tews, 2009; Ruizalba et al., 2016). Some exceptions exist (Ruizalba et al., 2016; Stafford & Tews, 2009), but considering the unique nature of family firms regarding ownership and role involvement, it deserves greater attention (Boles, 1996).

Scholars have argued that the issue of conflict between multiple roles is assumed to be even more complex in family firms than in non-family firms (Ruizalba et al., 2016; Moshavi & Koch, 2015).

15

Although the opportunity for control and flexibility over one’s work may be higher for family employees in family firms (Parasurman & Simmers, 2001), they often experience difficulties separating work and family roles in a satisfactory way (Stafford & Tews, 2009). The reason for this is because there is often an overlap between work roles and family roles. This overlap is very common to individuals working in the family business and simultaneously belong to the owning family. Because of the two existing forces of family and business within the context of family businesses, it may sometimes result in one force dominating over the other. When this situation occurs and is badly managed, negative outcomes may affect the harmony between family and work dimensions (Ruizalba et al., 2016). Besides, family firms sometimes employ multiple family members, and when this is the case, the possibility of inter-domain conflict increases (Boles, 1996). Edwards and Rothbard (2000) clearly stated that for family members working in a family business to find a balance between work and family roles, there needs to be a clear distinction between the two roles and domains. This assumption is based on role theory, which often is used within the context of work-family conflict and family firms since members of family firms often experience conflict between the roles of being a family member and at the same time being a member of the business (Memili et al., 2015). According to this theory, participating in multiple roles create tension and role strain (Allen, 2001), and since members of family businesses often are required to engage in minimum two subsystems at the same time, they face a greater risk of conflict between the roles (Memili et al., 2015). Accordingly, family employees often experience this separation of roles more challenging compared to non-family employees (Edwards & Rothbard, 2000).

Family firms often consist of more individuals than the founder and its family. Many family firms also employ non-family members who may also experience work-family conflict. According to Moshavi and Koch (2015), family firms are less likely to adopt work-family friendly policies (e.g. flexible scheduling, childcare programs, and financial support for dependent care) compared to non-family firms. This means that they are less likely to be responsive to solving work-family conflicts. This argues against the common belief that family firms should be more concerned with people’s individual needs than non-family firms since family firms are known to be driven more by values than profits. Moshavi and Koch (2015) and Miller et al. (2000) suggests that this may be because family business owners often are used to sacrifice family responsibilities over work responsibilities, and rather adjust the family system than the business system in times of conflict. Therefore, they often also expect both family-employees and non-family employees to share these habits and values and do the same. Prioritising business demands over family demands is perhaps

16

not a surprise in family firms, as owners of family firms often depend on the financial success of the business for personal well-being (Carr & Hmieleski, 2015).

Another explanation for the assumption that family-owned firms are less supportive of managing work-family conflicts and implementing work-family friendly policies is that family firms sometimes view family members as the most powerful stakeholders and consider non-family members as less critical to the functioning of the business. Therefore, the firm may put less emphasis on offering work-family support for non-family members (Moshavi & Koch, 2015). With that said, Moshavi and Koch (2015) also point out that this does not mean that family firms do not implement any work-family practices at all. Research has shown evidence that family firms often offer some benefits to their employees, but these benefits tend to be at a lower cost.

Understanding the potential antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict is important for businesses, but it is perhaps even more important in family firms because they are highly dependent on their human and social capital for long term survival and success. Employees´ perception of control, choice, autonomy, and support to successfully balance multiple roles are assumed to increase a business human and social capital (Rothausen, 2009). Rothausen (2009) further argued that role quality home and at work contribute to stronger human capital within family businesses. Therefore, reducing the risk of work-family conflict among all members of a family business is key to the firm's long-term success and survival.

2.3 Organisational culture in family firms

2.3.1 Defining cultureCulture has throughout the years been defined in many ways. Among others, culture has been defined as “the human-made part of the environment” (Triandis, 1982, p. 139), consisting of both objective and subjective elements. Another definition is the one from Hofstede (2011, p. 82) who defined culture as “the collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one group or society from those of another”. According to him, culture influence how people create meaning of the world, what values they hold, and what beliefs they consider as the truth. A third known definition is from Schein (1985, p. 2) who defined culture as “a pattern of basic assumptions – invented, discovered, or developed by a given group as it learns to cope with its problems of external adaptation and internal integration – that has worked well enough to be considered valid and, therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems”. A fourth and last definition is from Powell et al. (2009, p. 599) who

17

argued that “culture refers to deep-rooted group differences in cognitive, attitudinal, and behavioural patterns.

Culture has been used in a variety of contexts, including tribes or ethnic groups, nations, gender, generations, social classes, occupations, and organisations. Individuals are influenced by culture in all different types of contexts; however, some cultures are more deeply rooted than others. According to Hofstede (2011), societal, national and gender cultures are more deeply rooted in people’s minds compared to occupational or organisational cultures, because the latter is learned much later in life and can also change when changing environment. The main differences between societal and organisational cultures, what makes them distinct, are that societal cultures inhabit values, both conscious and unconscious ones. On the contrary, organisational values reside in the visible and conscious practices of the organisation.

2.3.2 Organisational culture

Organisational culture is the shared values, beliefs and behaviours that provide an organisation with its distinctive social and psychological environment (Messner, 2013). According to Fincher (1986) and Denison et al. (2004), organisational culture is based on ideas, patterns, and values, and often reflects a variety of political, ideological, sociological, experiential, economic, and psychological factors (Zahra et al, 2004). Furthermore, competitors, economic conditions, cultural networks, the nature of the business, and the nature of the organisational members are all factors believed to impact the development and evolution of organisational cultures (Messner, 2013; Denison et al., 2004). Organisational cultures are something deep-rooted within organisations that employees rarely notice but are highly influenced by (Triandis, 1982).

Organisational cultures are an important factor for a firm’s long-term viability and success and have been considered as a key for organisational growth, effectiveness, and competitive advantage (Cherchem, 2017). Three characteristics of corporate culture, identified by Barney (1986), were assumed to be vital for organisations ability to perform over a long period of time: be value-added to the bottom line, have uncommon characteristics, and be “imperfectly imitable”. The latter is often a strength for family firms due to their often unique history of culture (Denison et al. 2004; Zahra et al. 2004; Hall et al. 2001).

One important characteristic of organisational culture is that it is unique to an organisation and can often not be applied to any other organisation. A major issue within the studies of organisational cultures is that theories developed to understand and make sense of organisational cultures are often adapted to the social world that they know and understand. In addition to the uniqueness of

18

organisational cultures, this means that theories developed for one specific culture are often unsuitable and ineffective to another culture (Triandis, 1982). This indicates that theories developed to understand non-family firms may be inappropriate for understanding family firms since the culture of a non-family firm often differ from that of a family firm.

2.3.3 Organisational culture in family firms

Cultures in family firms are highly complex (Denison et al., 2004). Family firm cultures can be defined as “an important strategic resource that family firms can use to achieve a competitive advantage by promoting entrepreneurship and enhance the distinctiveness of these firms’ products, goods, and services” (Zahra et al., 2004, p. 373). It consists of shared values among family individuals, therefore, a family culture that is supportive for balancing work and family responsibilities will most likely impact how individuals feel about their work and family roles in a positive way (Rothausen, 2009). The development of family firm cultures is shaped by the owner´s values, organisational history, and accomplishments, as well as by national and regional cultures (Zahra et al., 2004).

Organisational culture is important for family firms because it is believed to be the determinant of organisational success (Cherchem, 2017). One of the things that make cultures in family firms so unique is the fact that the values embedded in the culture are often the individual values of the founder. This uniqueness is often considered as a competitive advantage for family businesses (Barney, 1986; Zahra et al. 2004). The fact that family firm cultures are strongly influenced by multiple factors contributes further to its uniqueness and source of competitive advantage (Zahra et al. 2004). Besides, some research has even suggested that cultures in family businesses may even be stronger than cultures in non-family businesses (Hall et al., 2001; Denison et al., 2004; Vallejo, 2008) because they often result in higher levels of employee commitment, loyalty, trust, and participation. Moreover, it is suggested that it leads to greater organisational harmony and long term orientation. Cultures in family firms are often built upon values of the founder, fostered by succeeding generations and embedded in family history and dynamics. This makes family firm cultures hard to replicate and imitate (Denison et al., 2004; Zahra et al., 2004; Hall et al., 2001). Rothausen (2009) suggested that organisational cultures within family firms are key for building strong human capital. Since family firms are highly dependent on their human capital, cultural values and norms that enable the creation of strong human capital are vital for a family firm’s survival and long-term success.

19

2.3.4 Supportive work-family culture

Cultures in family firms serve not only as a key to growth, success, effectiveness, and competitive advantage (Cherchem, 2017). Cultures are also important for the development and implementation of work-family programs and policies. A supportive work-family culture is assumed to offer flexibility, tolerance, and support for family obligations (Allen, 2001), and increase productivity and personal wellbeing (Fiksenbaum, 2014). Thompson et al. (1999, p. 394) defined a supportive work-family culture as: “the shared assumptions, beliefs, and values regarding the extent to which an organisation supports and values the integration of employees work and family lives”. It is suggested that work-family programs are only effective if there is an organisational culture supporting them (Thompson et al., 1999; Anderson et al., 2002). Wayne and Casper (2016) supported this by stating that a firm’s informal culture, which refers to the degree that shared assumptions, beliefs and values encourage the work-family integration, is more important for shaping employee behaviour than is formal policies. Therefore, it is of great importance that firms establish an organisational culture that supports multiple responsibilities from family and work. Research has also suggested that supportive work-family cultures decrease employees’ perception of work-family conflict and also reduce the potential negative outcomes of it. This indicates that supportive work-family cultures are a source for employee satisfaction and well-being at both work and home (Fiksenbaum, 2014). Another view of it is provided by Premeaux et al. (2007) who connects a supportive work-family culture with the theory of COR, by arguing that a supportive work-family culture increases individuals pool of resources, which leads to less stress and conflict regarding work-family intervention.

Thompson et al. (1999) further argued that organisational cultures could either encourage or discourage the use of work-family programs. Allen (2001) stated that employees who experienced their organisational culture as less supportive for family responsibilities were also less likely to utilise work-family benefits. For example, cultural norms that associate working long hours with commitment and career dedication most likely discourage employees to utilise work-family benefits that offer the opportunity to take time off or reduce the workload to meet family demands. Therefore, an unsupportive culture could make such programs ineffective (Thompson et al. 1999).

2.3.5 Three components of supportive work-family culture

Thompson et al. (1999) defined three components of a supportive work-family culture: organisational time demand, perceived career consequences associated with utilising work-family benefits, and managerial support. Work-family benefits refer to benefits that allow employees to

20

balance work and family responsibilities, such as flexitime and parental leave. Flexibility in work schedules has as an example proved to reduce the level of work-family conflict and increase the level of job satisfaction (Anderson et al. 2002).

Organisational time demand

The first component of a supportive work-family culture is organisational time demand and refers to an organisation's expectation that an employee will prioritise work over family. This component of a work-family culture includes norms about the number of hours at work and employees´ use of time regarding work. It is suggested that organisational cultures with such norms are expected to affect employee’s behaviour by indicating that working long hours is a sign of dedication and productivity. This has been proven to produce conflict between role responsibilities (Thompson et. al, 1999). Wayne, Randel and Stevens (2006), Mauno (2010), and Anderson et al, (2002) support this, claiming that employees who experience great time demands from work also report higher levels of work-family conflict. In a study of Allard, Haas and Hwang (2011) about how fathers experienced work-family conflict in Swedish firms, it was found that 25 per cent of the fathers thought that working long hours showed loyalty and increased the opportunities for advancements. This was also associated with greater work-family conflict. However, Glaveli, Karassavidou and Zafiropoulos (2013) argue that devoting a large amount of time at work to be perceived as committed and productive by the employer could be the desired outcome and lead to increased job satisfaction among employees.

Accordingly, it is suggested that high organisational time demand may encourage employees to spend more time at work than at home and to prioritise work above family. Researchers have suggested that this may result in employees experiencing conflict in where to devote time, as well as feeling that pressure from work affects one’s ability to perform in the family role. Based on this, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1: High organisational time demand is positively associated with work-family conflict.

Perception of career consequences

The second component refers to employees´ fear of negative career consequences from utilising work-family benefits. Even though work-family policies exist in an organisation, employees may fear to utilise them due to the underlying cultural norm that visibility at work is a direct indicator of an employee’s commitment and performance. If employees who utilise work-family benefit feel they may risk the opportunity for career advancements, increased payment, or other promotions, it will result in employees not utilising those benefits in fear of negative consequences (Thompson

21

et al. 1999). The perception of career consequences associated with utilising work-family benefits is related to the level of work-family conflict and is directly impacting work-family conflict outcomes such as job satisfaction and turnover intention (Anderson et al. 2002). Thompson et al. (1999) also reported that when the perception of negative career consequences for utilising work-family benefits was low, work-work-family conflict decreased.

An organisational culture with norms about negative career consequences from utilising work-family benefits is thus assumed to make it more difficult for employees to meet demands and responsibilities of multiple roles, since they may not utilise the benefits that enable such balance in fear of negative career consequences. Furthermore, the norm that visibility at work reflects employee’s level of commitment is also assumed to put pressure on employees to spend more time at work than at home. In general, this may lead to employees feeling they need to behave in a way that suits the expectations from work but may not be appropriate at home. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Perception of negative career consequences from utilising work-family benefits is positively associated with work-family conflict.

Managerial support

The last component is managerial support, which refers to the supervisor’s support and sensitivity to employees who have responsibilities at home (Thompson et al., 1999). Supervisors have an important role when it comes to reinforcing norms that encourage employees to utilise work-family benefits to balance work and family roles (Wayne, Randel & Stevens, 2006). They have the authority to determine the level of effectiveness of work-family programs, hence also influence the level of work-family integration among employees (Thompson et al. 1999; Anderson et al. 2002). Fiksenbaum (2014) also supported this by arguing that managers have a key role in terms of embracing a work-family supportive culture. Fiksenbaum suggested that managers must be supportive and tolerant for employee’s family responsibilities since they are the ones with the authority to implement formal and informal policies regarding work-family benefits. In family firms, the role of the manager becomes even more important since managers of family firms often also are the manager/leader in the family. This means that they have the authority to create a culture in both the family and the mutually supportive work domain (Rothausen, 2009).

Researchers have argued that work-family conflict can be reduced if supervisors support employees to balance work and family responsibilities (Thompson et al., 1999; Anderson et al., 2002; Wayne et al., 2006; Mauno, 2010), and that supervisor support have a direct impact on job satisfaction,

22

turnover intention, stress, and absenteeism (Anderson et al., 2002; Mauno, 2010). Furthermore, the perception itself of manager support was proven to be positively related to the perception of work and family control which in turn was associated with lower levels of work-family conflict and other types of strain (Thompson et al., 1999). O’neill et al. (2009) suggested that positive managerial support provide employees with more satisfying and reasonable time expectations and reduces the level of role conflict. Edwards and Rothbard (2000) also proposed that supervisors that support work-family balance also make it easier for employees to develop a behaviour in one role that does not interfere with the role performance of another role. Based on these findings, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: Positive managerial support is negatively related to work-family conflict.

2.4 Boundary management

Work-family conflict has often been discussed in association with boundary theory. Boundary theory has been widely used among researchers to explain and understand why individuals may differ in their perception of work-family conflict (Padhi & Pattnaik, 2017). Boundary theory demonstrates the nature of the boundaries that individuals have between work and family roles (Piszczek et al., 2018), and the transition between the roles (Ashforth et al., 2000). It suggests that individuals create boundaries based on personal needs and desires that are shaped by cultural and institutional arrangements (Padhi & Pattnaik, 2017). Two distinct boundary management styles have previously been identified by scholars: segmentation and integration (Ammons, 2013). Individuals´ boundary management style lies on a continuum ranging from high integration to high segmentation (Ashforth et al., 2000). High integration means the boundaries are highly flexible and permeable, allowing for transition and spillover between roles. High segmentation, on the other hand, means the boundaries are inflexible and impermeable and restrict the level of spillover between roles. Individuals hold different preferences for how to manage boundaries (Kossek & Lautsch, 2012).

Some researchers have argued that one style leads to a more positive outcome than the other. For example, Hecht and Allen (2009) suggested that permeable boundaries allowing role integration were positively related to work-family conflict. Voydanoff (2005) support this by arguing that role integration is associated with higher levels of work-family conflict. Padhi and Pattnaik (2017) also found that individuals preferring integration experienced higher levels of work-family conflict since they are more likely to be influenced by negative spillover from one domain to another. This conclusion has further been supported by other authors (Danner‐Vlaardingerbroek et al., 2013:

23

Heraty et al., 2008). Contrary, other scholars have shown contradicting results, indicating that boundaries enabling integration rather leads to lower levels of work-family conflict. Ilies, Wilson, and Wagner (2009) found that integration allowed positive spillovers from one domain to another under certain conditions. Kirschmeyer (1995) showed that employees who thought their organisation supported the integration of multiple roles also showed higher organisational commitment. Thus, according to previous research, a specific boundary management style may sometimes show positive outcomes and sometimes negative outcomes, indicating that one style does not fit all.

Nevertheless, some researchers have argued that the level of work-family conflict is not solely determined by a specific type of boundary management style. Rather, the level of work-family conflict perceived by individuals is determined by the level of fit between an individual’s boundary management style and preference (Kossek & Lautsch, 2012; Piszczek et al., 2018). When individuals can enact the boundary style that fits their preference, they perceive boundary management control. According to Kossek and Lautsch (2012), perceived boundary management control is both directly and indirectly affecting an employee’s perception of work-family conflict. Similar findings have been identified by Mellner, Aronsson and Kecklund (2014) who demonstrated a relationship between boundary management control and work-life balance. They found that high boundary management control was related to good work-life balance.

One factor largely influencing the level of perceived boundary control that employees experience is the organisational culture. Kossek and Lautsch (2012) argued that two types of work-family cultures exist: standardized and customized. Standardized cultures often expect employees to adapt to the preferred boundary management style of the organisation, thus strongly influence the type of boundary management style that employees enact. Such cultures increase the risk of a mismatch between boundary management style and preference and may lower employees perceived level of control which ultimately leads to increased work-family conflict. Sundaramurthy and Kreiner (2008) supported this argument, stating that organisations may support one type of boundary style more than another. Customized cultures, on the other hand, allow employees to enact a style that fits their preference to a larger extent, increasing their perception of control and reducing the risk of work-family conflict. Such cultures often provide customization using work-family policies and benefits that offer employees the opportunity to manage multiple roles in a successful way (Kossek & Lautsch, 2012). Having a customized work-family culture is perhaps even more important within family firms compared to non-family firms since family firms often are composited by both family employees and non-family employees. Piszczek et al. (2018) suggested that non-family employees

24

may have different preferences regarding boundary management style compared to family employees. Furthermore, they argued that family firms may put pressure on all its employees, both family and non-family employees, to integrate work and family roles because it reflects the business core values where family identity often is highly incorporated and highlighted as very important to the business. Therefore, a standardized work-family culture would most likely reduce perceived boundary management control among those employees in preference of segmentation since there would be a mismatch between boundary management style and preference.

Since this study examines family-owned SMEs, it is likely that the businesses we base our study on also employs non-family members. Moshavi and Koch (2005) pointed out that non-family employees are often ignored in studies of work-family conflict in family firms. Hence, in this study, we include also non-family employees by arguing that a work-family culture supporting customization will enable all employees, both family and non-family, to enact a boundary management style that fits personal preferences. As a result, the overall level of work-family conflict within the firm can be reduced. Kossek and Lautsch (2012) argued that the implementation of work-family policies support customization by allowing employees to enact a style that fit their preference. Since a supportive work-family culture is assumed to encourage the use of work-family programs and policies (Thompson et al., 1999), it could be suggested that a supportive work-family culture also increases employee’s perception of boundary management control. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4: A supportive work-family culture increases employees’ perception of boundary management control.

Perceived boundary management control is also associated with high psychological control. It is suggested that psychological control acts as a resource for individuals that they can use to reduce stress and strain resulting from work-family conflict. Higher psychological control leads to more resources (Kossek & Lautsch, 2012), which is proven to be related to lower work-family conflict (Kossek, Lautsch & Eaton, 2006). This is supported by COR theory which states that work-family conflict is the result of resource depletion and that people strive to acquire, retain and protect resources that enable them to devote more time and energy to multiple roles (Premeaux et al., 2007). According to Kossek and Lautsch (2012), psychological control strengthens the relationship between the benefits of a boundary management style and work-family conflict by increasing the feeling of more resources that one can use to manage multiple roles and reduce work-family conflict. Since a supportive work-family culture is believed to increase individuals´ pool of

25

resources (Premeaux et al., 2007), it could be suggested that higher perception of control increases the amount of resources available, thus strengthening the relationship between a supportive work-family culture and work-work-family conflict. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5: Boundary management control moderates the strength of the relationship between a supportive work-family culture and work-family conflict.

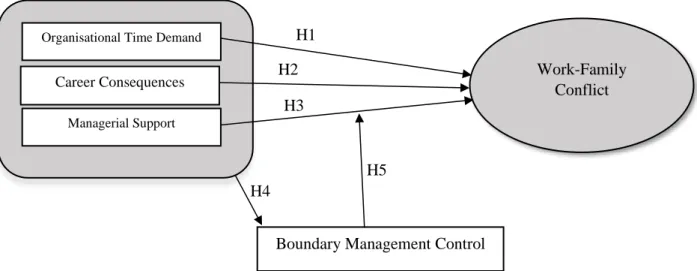

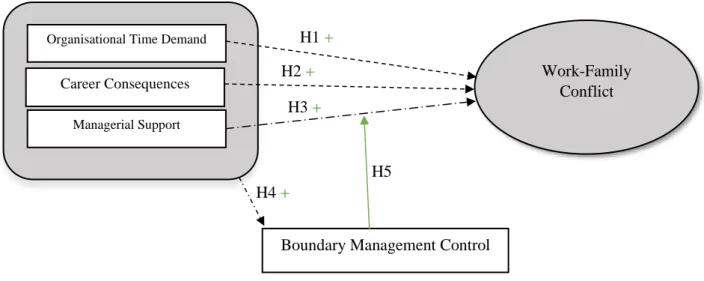

2.5 Summary: the hypotheses related to the family business theory

H1: High organisational time demand is positively associated with work-family conflict.

H2: Perception of negative career consequences from utilising work-family benefits is positively associated with work-family conflict.

H3: Positive managerial support is negatively related to work-family conflict.

H4: A supportive work-family culture increases employees’ perception of boundary management control.

H5: Boundary management control moderates the strength of the relationship between a supportive work-family culture and work-family conflict.

Figure 2.1. A conceptual model for visualizing the relationship between the work-family culture and work-family conflict.

Source: By the thesis authors Baker and Johansson (2020).

Supportive Work-Family Culture

H2 H1

H4

H5 H3

Organisational Time Demand

Career Consequences

Managerial Support

Work-Family Conflict

26

3. Methodology

__________________________________________________________________________________

This chapter provides and discuss the research philosophy, approach, methodological choice, strategy, and time horizon of the study. The method for sampling and data collection is described, and the quality of the survey and research are discussed regarding the research ethical aspects.

__________________________________________________________________________________

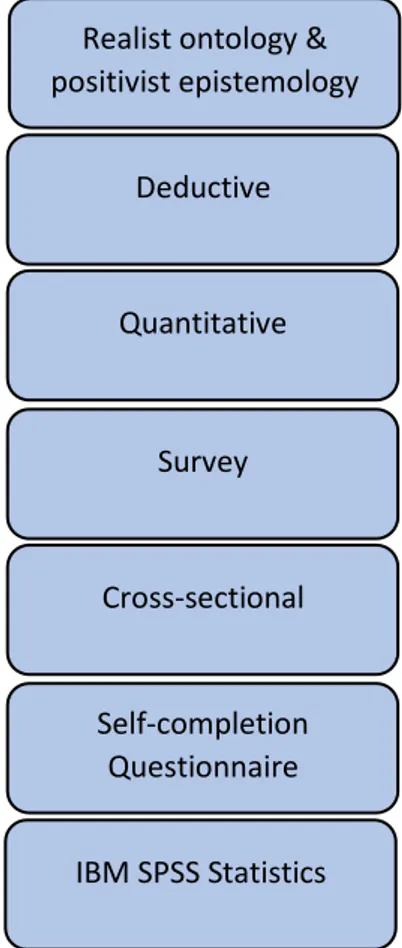

Figure 3.2 (Baker & Johansson, 2020) display the methodological approach of this study and help the reader get an overview of the decisions and approaches taken during this study.

Research Philosophy Research Approach Methodological Choice Research Strategy Time Horizon Data Collection Data Analysis

Figure 3.2. Methodological Approach (adapted by the authors; Baker & Johansson, 2020).

3.1 Research philosophy

Research philosophy clarifies how research knowledge is developed and often refers to the beliefs of reality that the research investigates (Bryman, 2012). This study takes on a realist ontology and a positivist epistemology approach. According to Easterby-Smith et al. (2018), this research philosophy approach is associated with quantitative research methods.

Realist ontology & positivist epistemology Deductive Quantitative Survey Cross-sectional Self-completion Questionnaire IBM SPSS Statistics