Collaboration within

Supply Chains

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 Credits

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: International Logistics and Supply Chain Management

AUTHOR: Alexander Andersen and Ludvig Brewitz

TUTOR:Susanne Hertz

JÖNKÖPING May 2016

Can conflicts be attributed to the different roles of

logistics companies?

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Collaboration within Supply Chains: Can conflicts be attributed to the different roles of logistics companies

Authors: Alexander Andersen – 900318

Ludvig Brewitz - 921021

Tutor: Susanne Hertz

Date: 23/5-2016

Subject terms: Supply Chain Management, 3PL, 4PL, Collaboration, Conflicts

Abstract

Introduction – Supply chains increase in size and complexity, more actors are becoming involved and an increased collaboration among actors are a necessity. Still, undesired conflicts occurs and are unavoidable in a collaboration. There are ways to reduce the negative effects and improve management of conflicts provided by previous researchers focus on conflicts and conflict management in general. However, this thesis emphazises on investigating what conflicts that occur within different collaboration setups that can be attributed to the type of logistics company involved. Therefore, the following purpose is stated:

Investigate what types of conflicts occurring during collaboration that can be attributed to the different roles of 3PL and 4PL companies.

Methodology – To answer the purpose a single case study was conducted which involved a focal firm and its collaboration with two different logistics companies (a 3PL and a 4PL) within the same economical climate. Due to the uniqeness of the case, a multiple methods qualitative study was performed and to strengthen the validity of the data collected both documantary analysis as well as semi-structured interviews were conducted. Respondents were handpicked based on knowledge of both collaboration setups, to ensure quality of the data collected. Gathered data were sumarized and categorized using Mamad and Chahdi (2013) conflict factors, and later analyzed to accurately detect key points to generate a result and answer the research questions.

Result – To summarize the result, findings of what we discovered through our data analysis generated similarites and differences in conflicts occurred within both collaboration setups. These conflicts are linked to Mamad and Chahdi (2013) conflicts factors regarding collaboration among actors, in order to clarify why and which conflict area these conflicts occurred in.

Analysis – From the conflicts identified in the result, further analysis were conducted. Where, previous literature regarding logistics companies (3pl and 4PL) were applied in order to enable attribution of conflicts to company types.

Conclusion – Through the analysis, many conflicts that occured are based on factors such as operational structure, problem solving and company policies which are not affected by the company type. However, three conflicts and problem areas can be connected to be generally more common either with 3PL companies or 4PL companies. The first lies within the commitment area where 3PL companies can generally be seen as less committed. The second area is communication were important information were more often late due to passing through more actors, causing more conflicts when collaborating with a 4PL. The last problem area were within formalization where findings suggests that there are conflicts caused by 4PLs using several carriers which causes problems such as varying regulations and truck dimensions from carriers.

Table of Contents

1

Introduction ... 1

1.1

Background ... 1

1.2

Problem Description ... 2

1.3

Purpose and Research Questions ... 3

2

Theoretical Framework ... 5

2.1

Introduction ... 5

2.2

Supply chain management ... 5

2.2.1

Network approach ... 6

2.3

Outsourcing ... 7

2.4

Definition of Actors ... 8

2.4.1

3PL and 4PL companies ... 8

2.4.2

Distribution Center ... 11

2.5

Collaboration ... 13

2.6

Supply Chain Conflicts ... 17

2.7

Theory summary ... 18

3

Methodology ... 21

3.1

Research Methodology ... 21

3.2

Research Philosophy ... 22

3.3

Research Approach ... 23

3.4

Strategy ... 24

3.5

Methodological Choice ... 26

3.6

Time horizon ... 26

3.7

Data collection ... 27

3.7.1

Semi-Structured Interviews ... 27

3.7.2

Documentary Analysis ... 29

3.7.3

Selected Sample ... 29

3.7.4

Interview Process ... 30

3.8

Data Analysing Techniques ... 31

3.9

Research Quality ... 32

3.9.1

Research Ethics ... 33

4

Result ... 34

4.1

Collaboration Structure ... 34

4.1.1

Planning Process ... 35

4.1.2

Differences Between the Collaboration Setups ... 38

4.2

Conflicts and Problems Revealed ... 39

5

Analysis ... 48

6

Conclusion and Discussion ... 56

6.1

Conclusion ... 56

6.1.1

Contribution ... 57

6.2

Limitations ... 57

6.3

Future Research ... 58

Table of Figures

Figure 1: Supply Chain Management antecedents and consequences (Mentzer

et. al., 2001) ... 5

Figure 3: Customization of third-party services (Stefansson 2006) ... 9

Figure 2: Hertz and Alfredsson (2003) ... 9

Figure 4: The CLM model (Stefansson 2004) ... 10

Figure 5: Multi-level Supply Chain Network (Tsao, 2013) ... 13

Figure 6: Theory Summary ... 19

Figure 7: Link between Research Questions and Theoretical Framework ... 19

Figure 8: The Research Onion (Saunders et al., 2012) ... 21

Figure 9: Data Analysis Process ... 31

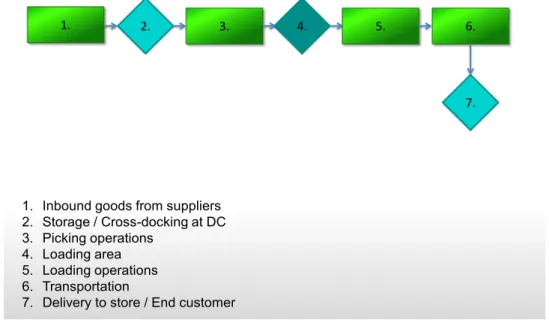

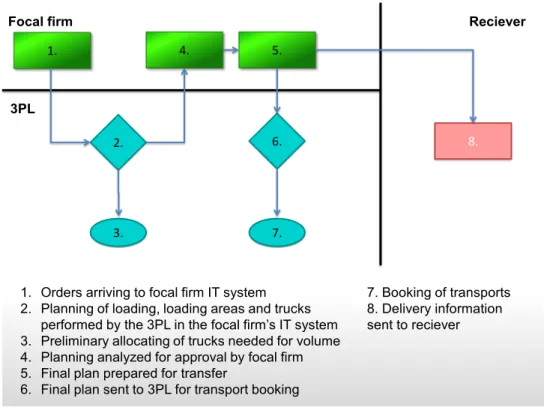

Figure 10: Simplified Flowchart ... 35

Figure 11: Collaboration Process with the 3PL ... 36

Figure 12: Collaboration Process with the 4PL ... 37

Tables

Table 1: Effects on Collaboration ... 16

Table 2: Interviews Performed ... 31

1

Introduction

This chapter provides an introduction to the current research in this field. Initially background will explain key motives of the thesis, which breaks down to a more detailed problem description. Then the purpose of the thesis as well as the two research questions is presented.

1.1 Background

In today’s globalized economy, single companies no longer compete with other single companies, instead competition has moved towards whole supply chains competing with each other, even on a global scale (Coyle, Langley, Novack and Gibson, 2013). The traditional definition of supply chain is centered on the idea that a supply chain covers the entire flow from the first supplier to the final customer (Jespersen and Skjott-Larsen, 2005). The academic research results have overtime point in the direction that a key success factor for supply chains is its ability to integrate all the involved actors and manage the supply chain as a whole (Bowersox, Daugherty, Dröge, Rogers and Wardlaw, 1998; Council of Logistics Management, 1995; New, 1996; Lee, 200; Christopher, 2005). Integration can be described as a way of handling relationships, sharing information and resources, as well as coordination between actors (Lee, 2000). Furthermore, managing global supply chains involves collaboration with several actors, which during the last decade has led to supply chains becoming increasingly complex (Bode and Wagner, 2015). As former vice president of supply chain operations from Coca-Cola North America (Gilmore, 2008) stated, “If you are in supply chain management today, then complexity is a cancer you have to fight”. One of the roots regarding this increased complexity is firms’ strategy of focusing on core competencies to operate more effectively and efficiently within their own processes (Coyle et al., 2013). Due to this, outsourcing have become a more or less a standard solution in order to focus on core competence and share risks (Dinu, 2015) This has amplified the necessity for actors in supply chain to collaborate in order to achieve an efficient and effective supply chain by bringing in special competency through outsourcing (Ellram and Cooper, 1990; Horvath, 2001).

The increased need of specialized services and firms’ focus on their own core competencies, outsourcing of logistics services and activities have also grown substantially over the past decade (Bagchi and Virum, 1998; Knemeyer and Murphy, 2004; Ashenbaum, Maltz and Rabinovich, 2005; Langley, Albright, Morton, Wereldsma, Alf, Swaminathan, Smith, Murphy, Deakins and Peters, 2009) both domestically and globally (Coyle et al., 2013). In addition to this, customers being more demanding and market competition escalating, further strengthen the need for outsourced services (Kotler, 1997). One service which companies often outsourced is the logistics business function of handling and managing the flow of goods. This is often addressed by the use of a third party (3PL), or fourth party (4PL), logistics service provider.

A 3PL company can be seen as a middleman, providing logistics services for other firms, however 3PL companies have expanded, providing more and more services within supply chains and have transformed from merely focusing on transporting and handling goods to providing strategic and value-adding services throughout the supply chain such as merge-in-transit, consolidation and administrative services (Skjoett-Larsen, Halldorsson, Andersson, Dreyer, Virum and Ojala, 2006; Maloni and Carter, 2006; Mortensen and Lemoine, 2008, Marasco, 2008).

The 4PL is generally viewed as having more of a consultant role, providing no physical assets themselves but rather building, managing and operating supply chains through administrative work (Bumstead, 2002; Hertz and Alfredsson, 2004; Stefanson, 2006; Burnson, 2011).

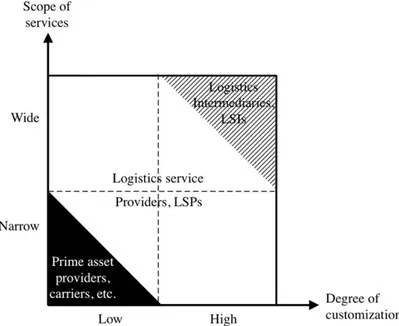

There are different levels of integration and different supply chains as well as actors themselves handle integration differently depending on their goal. This creates a wide variety of types and levels of collaboration and integration. As explained by Stefansson (2006), logistics companies can be divided into different categories, namely carriers, logistics service providers (3PL) and logistics service intermediaries (4PL). Stefansson (2006) classifies the carriers as providers of transportation and the most basic services, 3PL’s as a more advanced service provider who in addition to the basic services also provides more advanced logistics services as well as administrative and operational services. The classification of a 4PL is the role of a consultant who builds and manages the logistics operations, however without their own physical assets (they outsource physical activities). Hertz and Alfredsson (2003) provides a similar type of framework of classifying different logistics firms, which shows that there are a wide variety of logistics service providers operating, who all provide different types and levels of integration and services.

Whereas integration has been proved to be beneficial to performance, integration, cooperation and communication between actors it has also been confirmed to be difficult (Childerhouse and Towill, 2011). With the increase in size and complexity of supply chains, more actors are becoming involved and collaboration between actors increases. Shaiq, Shaikh and Ahmed (2015) state that conflicts are an undesired but unavoidable phenomenon of functional interaction, when collaborating within a company or with chain partners such as suppliers or logistics service providers. Furthermore, according to Razmi and Haghighi (2014) buyer-supplier relationships and collaboration is a sensitive issue since it can provide benefits for both parties while at the same time trigger conflicts and problems due to differences. In addition to this and due to the unavoidable nature of conflicts, Shaiq et al. (2015) found that 91% of managers in their study had faced conflicts with one of their supply chain partners.

While conflicts might not be completely avoidable, ways to reduce the negative effects and improve the handling and management of conflicts as well as the area in general have been extensively studied in previous literature (Gaski, 1984; Ayoko, Ashkanasy and Jehn 2014). With the many different type of collaboration partners that exists, there are several types of collaboration setups that can be seen within different supply chains. Previous research have focused heavily on conflicts and conflict management in general, however there are little research regarding the differences of how collaboration setups work depending on what type of logistics partner that is involved.

1.2 Problem Description

As mentioned in the background, supply chains have increased its complexity due to firms increased focus on core competencies (Coyle et. al., 2013; Bode and Wagner, 2015). Collaboration with actors within the supply chain are a necessity to sustain an effectively and efficient supply chain (Ellram and Cooper, 1990; Horvath, 2001). Furthermore, Lee (2000) stated supply chain integration as one key element of cooperation, including handling of relationships, sharing of information and resources as well as coordination between actors. Several studies highlight the importance of integration and collaboration within supply chains. Hardy, Phillips and Lawrence (2003) stated that collaboration can develop, maintain and even enhance competitive advantage. Additionally Ireland and Webb (2007) arguing that relational issues such as trust and power should be simultaneously managed among members for firms to become fully committed to supply chain efficiency and effectiveness. Furthermore, the advantage of cooperative relationships can be seen as synergy gained through shared expertise and resources, exchange of information, better planning and support, and joint problem solving (Stank, Crum and Arango, 1990).

Even with all the research pointing on the advantage of collaboration, integration and relationships among actors within the supply chain, firms still struggle to involve other firms in such ways that the supply chain can gain or sustain competitive advantage (Min et. al., 2005). Shaiq et. al. (2015) claim that actors have different if not contradictory targets and missions. This has been previously studied by Barutçu, Dogan, Barutçu and Kulakli (2010) who found that involved partners in the supply chain often have different objectives, a prevailing sense of mistrust between partners, weakness in operational structure, lack of cooperating spirit and substandard quality of communication and providing insufficient information or stating half truths.

This claims that conflicts among actors are common and whether the conflict is with a supplier, with a customer or with a service provider, the nature of the majority of conflicts as found by Shaiq et al., (2015) is policy issues, contractual, financial or operational issues. The reasons of why conflicts occur as Barutçu et al. (2010) stated are well known by actors in supply chains and as stated in the background, extensive research has been performed in the field of conflict management (Gaski, 1984; Ayoko et al., 2014). However previous research often has a more general point of view of examining conflicts between a buyer and a supplier or what type of conflicts that generally occurs within a supply chain.

Previous research rarely touches upon if conflicts can be specifically derived from collaborating with different company types that covers the same area of business. By predicting and preparing before collaboration between two actors starts regarding what type of conflicts that might occur, companies can have a better starting point for their collaborations (Shaiq et al., 2015). Therefore, investigating if certain conflict types can be generalized and linked to specific logistics company types can enable prevention of conflicts at a much earlier stage in the collaboration.

This thesis will focus on a focal firm who has collaborated with two different types of logistics companies within a supply chain. As mention previously, this setup is rarely looked upon in previous research where conflicts that occurs between one focal firm and its different collaboration partners. The specific focal firm in this case has collaborated with a 3PL company and a 4PL company which are two different types of companies while still performing similar roles within the supply chain. The goal is to provide a deeper insight in the existing theory by analyzing if collaboration with a 3PL creates certain conflicts compared to collaborating with a 4PL company and identify any similarities and differences that can be linked to the role of the logistics companies.

1.3 Purpose and Research Questions

With the problem description and gap in the literature whether conflicts that occur are different or similar between different types of firms, the purpose of this study is formulated as follows:

Investigate what types of conflicts occurring during collaboration that can be attributed to the different roles of 3PL and 4PL companies.

To fulfill this purpose, two research questions will be answered. The first research question is needed to identify the areas where conflicts may occur between a focal firm and a 3PL company as well as between the focal firm and a 4PL company. Therefore, the first research question is stated as follows:

1. What type of conflicts occur when a focal firm collaborates with a 3PL company as well as when the same focal firm collaborates with a 4PL company?

Answering the first research question will provide data in order to analyze if it is possible to derive conflicts to the different roles of 3PL and 4PL companies. This leads to the second research question, which is stated as follows:

2. How can conflicts occurring between a focal firm and a 3PL company as well as between the same focal firm and a 4PL company be attributed to the different roles of 3PL and 4PL companies?

Answering these research questions allow us the possibility to fulfill the purpose of identifying conflicts occurring in different collaboration setups as well as analyzing what type of conflicts that can be derived from the different roles of 3PL and 4PL companies.

2

Theoretical Framework

This chapter initially presents the theories applied, followed by a summary of the theories, explaining how these are connected to the thesis in order to fulfill its purpose.

2.1 Introduction

The outline in theoretical framework is constructed through funneling, meaning that each theory is used in order to generate a theme. Starting with an overview perspective, this is narrowed down to the specific theories of focus in this thesis. Still, theories presented at the top of the funnel are required in order to fully grasp the theories presented at the end. Therefore, the theories are structured in following: Supply Chain Management (SCM), Network Approach, Outsourcing, Definitions of Actors, Collaboration and Supply Chain Conflicts (SCC).

2.2 Supply Chain Management

Even though SCM is well known and constantly used both in the world of academia and practice, authors still argue for different definitions of SCM, which creates a considerable confusion as to its meaning. Tyndall, Christopher, Wolfgang and Kamauff (1998) summarize that some authors define SCM in operational terms involving the flow of materials and products, some view it as a management philosophy and some view it in terms of a management processes. Furthermore, Cooper and Ellram (1993) research highlight that SCM has even been conceptualized differently among authors within the same article, stating that SCM is a form of integrated system between vertical integration and separate identities and also as a management philosophy. In additional to this, SCM can be classified into three categories: a management philosophy, implementation of a management philosophy and a set of management processes (Mentzer et. al., 2001). Due to different definitions as well as classifications the term SCM presents confusion for those involved in the supply chain in reaching the phenomena but also for those attempting to establish a supply chain to management.

Figure 1: Supply Chain Management antecedents and consequences (Mentzer et. al., 2001)

Therefore, Mentzer, DeWitt, Keebler, Min, Nix, Smith and Zacha-ria (2001) as can be seen in Figure 1: Supply Chain Management antecedents and consequences (Mentzer et. al., 2001) clarifies the understanding of the term SCM, where the management philosophy refers to supply chain orientation (SCO) instead of SCM with the definition as “recognition by an organization of the systemic, strategic implications of the tactical activities involved in managing the various flows in a supply chain”. More accurately, SCM is the actual implementation of this orientation across various companies in the supply chain with the definition as “the systemic, strategic coordination of the traditional business functions and the tactics across these business functions within particular company and across businesses within the supply chain, for the purposes of improving the long-term performance of the individual companies and the supply chain as a whole“ (Mentzer et. al., 2001).

In other words, SCO is an essential for SCM, which should be interpreted as actions undertaken by actors in a supply chain in order to realize the SCO. According to Mentzer et. al. (2001), supply chains has a SCO (management philosophy) when all the key firms involved in a supply chain share the same willingness to fulfill these antecedents (see Figure 1: Supply Chain Management antecedents and consequences (Mentzer et. Al., 2001)). Through management actions, across suppliers and customers, the implementation of all the principles of the SCO can be performed and therefore called SCM. The outcome of SCM or as Mentzer et. al. (2001) refers to as consequences are lower costs and improved customer value and satisfaction to acheive competetitve advantage. This is supported by Sople (2011) stating that SCM primary focus is to serve consumers with excellent goods and services againt optimum costs and quick response time, in order to improve customer value and satisfaction, which is the purpose of SCM. In additon, Sople (2011) defines similar activities identified in SCM:

v Integration of customers and suppliers to business processes

v Information flow among channel member for planning, implementation and monitoring processes

v Sharing channel risks amongst partners to gain a competitive advantage

v Co-operation among channel members to effectively manage the distribution process v Integration of processes for synergistic effects

v Building and maintaining long-term relationships with partners

The fundamental of SCM is based on the idea of partnerships with suppliers, marketing channel members and other service providers with the goal to maximize profit through enhanced competitiveness, imparting benefits to all partners in the supply chain (Sople 2011).

2.2.1 Network approach

A network consists of several actors linked together through their relationships, which Håkansson and Snehota (1989) explain that this web of relationships can be seen as a network. The relationships that create a network are usually complex and multifunctional and require a method to tackle this, which is called the network approach. Ekman, Thilenius and Windahl (2014) stated that the network approach focuses on the complex or multifunctional relationships among actors and their activities and resources connected within the network. Furthermore, Holmlund and Törnroos (1997) used the definition of relationship to define the network approach as follows “an interdependent process of continuous interaction and exchange between at least two actors in a business network context”. According to Håkansson and Snehota (1995) these interaction and exchange can vary from processes, activities or resources that bonds actors together.

Snehota (1990) and Tikkanen (1996) argue that the network approach has a high compatibility with the inter-organizational business environment firms’ encounter in their everyday

operations. It creates a “visible hand”, meaning that inter-organizational exchange is visualized by the process of networking, linking together with various market actors and their complex activities and heterogeneous resources (Arnd, 1979; Cova 1994; Forsgren and Johanson, 1992; Håkansson and Johanson, 1993; Mattsson, 1985; Snehota, 1990; Thorelli, 1986).

In order to create a network with this network approach, two different setups can be used, the network approach can be based on the complete network (Tikkanen, 1998) or take the focal firm viewpoint that is acting in the network (Hertz, 1993; Li 1995; Salmi, 1995). According to Edward et. al. (2013) this network can be modeled with set of “nodes” that represent firms and set of “links” that connect the firms with each other within the supply chain. Furthermore, Edward et. al. (2013) argue that these links between nodes represent exchange relationships and underlying contracts if there are any. This can easily create several types of links between firms but the most critical types of connections are presence of contracts, various flow types including material flows, information flows and financial flows (Edward et. al., 2013). All with the greater purpose in mind of creating products or services (Edward et. al., 2013).

2.3 Outsourcing

Actors that are included in the supply chain are chosen due to their specialization within a certain area as well as adding a value to the chain. This allows companies to focus on their core competencies and operate more effectively and efficiently within their own processes (Coyle et. al., 2013). There are different ways to establish which actors that cooperate within the supply chain. According to Lysons and Farrington (2012) this can be done through vertical integration or horizontal integration, where vertical integrations refers to which extent an organization expands upstream into industries that provide input (backward integration) or downstream (forwards integration) into industries that distribute the organization’s products. Within vertical integration, a focal firm can outsource to industries upstream or downstream in the supply chain, which according to Lyson and Farringtion (2012) can be defined as “a management strategy by which major non-core functions are transferred to specialist, efficient, external providers”. Jonsson and Mattsson (2011) support this by stating that outsourcing is an opportunity to focus on core competence as well as that the activities outsourced can be performed more cost efficient by other companies. Therefore, several firms outsource their external transports and warehouse activities to 3PL companies (Jonsson and Mattsson, 2011) as well as 4PL companies, since manufacturing industries or other companies do not see distribution or warehousing as their core competencies. This has lead to more actors being involved in the supply chain network and therefore in order to attain an efficient logistics, it has been an increased focus on how each actor is connected with one and other (Jonsson and Mattsson, 2011).

According to Dinu (2015) the main factors for why companies outsource are generally lower operational and labor costs, lack of own employee specialization, accessibility to cheaper labor, ability to focus and concentrate on core competencies and risk sharing. Therefore, actors within a supply chain entail to collaborate in order to achieve an efficient and effective supply chain by using special competency through outsourcing (Ellram and Cooper, 1990; Horvath, 2001). As mentioned above companies now more often outsource their logistics business function of handling and managing the flow of goods, which often are addressed by 3PL or 4PL companies. In order for logistics companies to handle and manage the flow of goods, the collaboration is crucial in order to create value for the whole supply chain which is mentioned by Wang, Persson and Huemer (2014). To further support this, Simatupang and Sridharan (2002) define collaboration as occurring when “two or more independent companies work jointly to plan and execute supply chain operations with greater success than when acting in isolation”. Collaboration also focuses on the long-term relationships among actors, which according to Min

et. al. (2005) implies that collaborative strategies focus on joint planning, coordination, and process integration between suppliers and customers and other partners in a supply chain, such as a logistics company.

2.4 Definition of Actors

This thesis encounters three actors within a supply chain, therefore a literature review regarding each actor’s definition are presented, starting with theories about third (3PL) and fourth (4PL) party logistics providers, which is then followed by distribution center (DC) theory.

2.4.1 3PL and 4PL Companies

Third (3PL) and fourth (4PL) party logistics providers have emerged as a result of the increased demand for specialized logistics services. As mentioned in the background, 3PL companies can be seen as a form of middleman company providing logistics services for other firms by being the link between a supplier and a buyer/customer. The definition of 3PL companies have changed over time due to 3PL companies providing more and more service to fulfill customer demands. Originally 3PL companies focused on providing the transportation and handling of goods from one point to another, however now they tend to be strategic partners providing value in administrative services in addition to the physical handling of goods (Skjoett-Larsen et al., 2006; Maloni and Carter, 2006; Mortensen and Lemoine, 2008, Marasco, 2008). There are a wide variety of 3PL firms depending on their focus they provide value and services in different ways. According to Persson and Virum (2001), examples of how different 3PL companies strategizes and provide services can be identified by looking at what they base their business around. Some 3PL companies are based around physical warehouses with their business revolving around logistics functions such as inventory management and storage connected to their warehouses. At the same time, other 3PL companies can be based around distribution networks with the main focus of providing channels for distribution through terminals and transportation (Persson and Virum, 2001). There are many different variations of 3PL companies and definitions of what each type of logistics company actually is and what they do vary from author to author. The same confusion and different interpretations from author to author applies to the term of 4PL companies. However the 4PL term has its origin from Andersen Consulting (today Accenture) and their definition of a 4PL company was (Bumstead and Cannons, 2002, pp. 79):

“An integrator that assembles the resources, capabilities and technology of its own organization and other organizations to design, build and run comprehensive supply chain solutions.”

While this definition provides a picture of what a 4PL company does, it does not provide enough information to clearly separate the term 4PL from the term 3PL. Examining the literature provides a general view that a 4PL operates more as consultant where there goal is to make their customers gain economical benefits and by doing so gaining benefits themselves by providing no physical assets but rather act as managers and controllers, taking over other firms logistics functions (Bumstead, 2002; Hertz and Alfredsson, 2004; Richardson, 2005; Stefanson, 2006; Burnson, 2011; Lumsden, 2012). In addition to this, Win (2008) emphasizes that 4PL companies are heavily focused and measured by how much value they provide to their customers while 3PL companies are much more measured by how much their services costs. Hertz and Alfredsson (2003) provides a framework, which divides 3PL (third party logistics providers) by the characteristics “General problem solving ability” which is essentially the ability to solve problems in terms of providing services to solve said problems and “Customer adaption” which is the degree of customized services that a company provides. This result in

four different types of 3PL firms, Standard TPL (third part logistics) provider, Service developer, Customer adapter and Customer developer (see Figure 2: Hertz and Alfredsson (2003)).

With Hertz and Alfredsson’s classification in mind, Stefansson (2006) provides a framework for classifying logistics companies in general, without the focus on 3PL companies. Stefansson analyzed companies and found that the main differences between the logistics companies were its scope of services and their degree of customization. This resulted in a framework (see

Figure 3: Customization of third-party services (Stefansson 2006)) where logistics companies

are divided into three main categories, Prime asset providers such as carriers, Logistics service providers and Logistics service intermediaries.

Figure 3: Customization of third-party services (Stefansson 2006) Figure 2: Hertz and Alfredsson (2003)

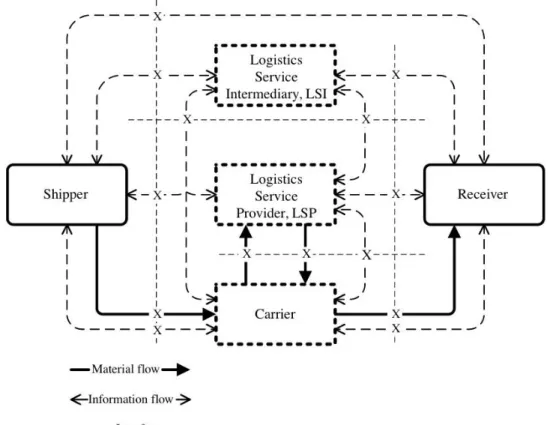

Figure 4: The CLM model (Stefansson 2004) further illustrates the different actors and their role within the supply chain. The figure shows that the material flow goes from the shipper, to the carrier, and can pass through the LSP before finally reaching the receiver. Essentially the LSP could be providing carriers services themselves or outsource the physical part to fully committed transportation companies. The figure also illustrates how the information flow connects all of the actors together meaning that information, as opposed to material affects and reaches all of the different actors. As the figure illustrates, LSI’s have no connection to the material flow, which means that they outsource all the physical handling (Stefansson, 2006). Stefansson (2006) emphasizes the high level of customized services provided by LSI’s and means that providing a complete list of services is unrewarding. However the general view of the operations of LSI’s is that LSI’s design the logistics system for their customers, contract LSP’s or carriers to carry out the physical handling and activities and then perform the administrative work needed to operate the logistics system, essentially being more of a consultant (Stefansson, 2006).

Analyzing the theories and frameworks provided by Hertz and Alfredsson (2003) as well as Stefansson (2004) and Stefansson (2006) gives a view of different classification and types of logistics companies. Hertz and Alfredsson’s (2003) framework classifies logistics companies similar to the framework provided by Stefansson (2006) in the sense that the characteristics “general problem solving ability” from Hertz and Alfredsson (2003) is on par with the characteristic by Stefansson (2006) of “scope of services”. This because of the fact that the “general problem solving ability” discussed is a company’s ability to solve customers’ problems in terms of providing different services. In the same sense, the second characteristic from Hertz and Alfredsson (2003) “customer adaption” is essentially the same thing as “degree of customization” from Stefansson’s (2006) framework. In addition to this, our view is that the

“customer developer” company type from Hertz and Alfredsson (2003) can be seen as more of a 4PL company rather than a 3PL company as it’s described as providing more of a consultant role. This fits with the description of the “LSI” definition provided by Stefansson (2006) and further strengthens the similarities between the frameworks.

The main difference between the frameworks is the lack of prime asset providers or carriers in the framework provided by Hertz and Alfredsson (2003) and comparing it with the framework by Stefansson (2006), Hertz and Alfredsson (2003) framework could be seen as only looking at and analyzing LSP and LSI companies and disregarding the prime asset providers. Otherwise, these two frameworks provide similar definitions of different types of logistics companies which also fits the general descriptions of 3PL and 4PL companies provided by several different authors when reviewing existing literature (Bumstead, 2002; Burnson, 2011; Jonsson and Mattson, 2011; Lumsden, 2012; Lysons and Farrington, 2012).

To summarize and exemplify the differences between 3PL and 4PL companies based on the theory provided above, a shorter example can be made. A 3PL company can be seen as a provider of a wide variety of logistics services ranging from the basic transportation to cross-docking, consolidation and administrative services. Generally 3PL companies have their own assets that they use in order to provide their services, which mean that they have and operate their own trucks and transportation cars in order to fulfill their customers’ needs. A 4PL company on the other hand, can be seen as a consultant who basically takes over and operates the logistics department within their customers companies. Rather than being the providers of actual services and physical transportation and handling, a 4PL acts as a middleman who manages the logistics function by hiring transporters and building the supply chain structure. By hiring a 4PL company you basically outsource your whole logistics management and operation department who in turn will work to find and hire transporters and services to fulfill the company needs. On the other hand, when you hire a 3PL company you basically have to find, hire and secure transporters and manage your logistics operations yourself, much like a 4PL would do if you select that route. This can be seen as you either keep your logistics department and buy a essentially a “product” in terms of transportation and services from a 3PL company, or you hire a 4PL company who goes in as a consultant who manages the logistics department and you let the 4PL company buy the transportation and service “product” from others.

Different supply chains can vary greatly regarding what different actors do and as such, listing specific activities that a 3PL, respectively a 4PL is unrewarding in terms of necessity for this study. The case description will provide detailed information as to what each actor does within this specific case in order to give an overview of the detailed differences between the 3PL and 4PL in this case. However detailed description of the differences between 3PL and 4PL companies in general, beyond the above example and explanation that a 4PL is more of a consultant would simply just be a long list of different activities. It’s the backbone of these activities that is important in this case which is the difference explained above regarding that 3PL companies are asset based and 4PL companies’ non-asset based and acts as a consultant.

2.4.2 Distribution Center

To describe a distribution center you first have to define the basic version, which is a terminal and is defined by Lumsden (2012, pp. 598) as:

“A point in the material flow system where you connect and divide the flow of goods”

In addition to this definition, Lumsden (2012) as well as Jonsson and Mattsson (2011) puts heavy focus on the many functions a terminal can fulfill such as cross-docking, consolidation,

sequencing, sorting, warehousing and kitting which creates different types of terminals, depending on their focus. This essentially means that terminals can be seen as many different things, depending on what type of functions that are performed.

With the many functions that a terminal can perform, it makes it hard to describe a distribution center solely depending on its functions. However, one of the key choices that companies have to make is whether they want to use a centralized or a de-centralized strategy in terms of warehousing and where to locate their terminals, warehouses and transport routes (Lumsden, 2012; Huang, Menezes and Kim, 2012). Jonsson and Mattsson (2011) describes one of the typical strategies as a centralized strategy focusing on “delivery through distribution central/logistics central”. In addition to this, Jonsson and Mattsoson (2011) describes the distribution central as a point in the material or goods flow where consolidation, picking operations and warehousing takes place. This means that a distribution center can be seen as a larger terminal within a supply chain with a centralized strategy.

Reviewing additional literature reveals that according to Coyle et al. (2013) distribution center’s carries out four primary functions in traditional distribution operations:

v Accumulation – Receiving goods from several suppliers in order to consolidate and ship complete orders.

v Sorting – Sorting goods for storage or for transfer to customers.

v Allocation – The function of being able to split/break bulk orders down to match customer demand rather than shipping large bulk deliveries which suppliers might demand when ordering.

v Assortment – The ability to have a wide variety of goods from different suppliers available for shipment to customers. Consolidation of goods from different suppliers creates a mixing capability for the distribution center.

While these might be the most traditional functions according to Coyle et al. (2013), they much like Lumsden (2012) and Jonsson and Mattsson (2011) emphasizes the wide variety of functions that a terminal acting as a distribution center can fulfill.

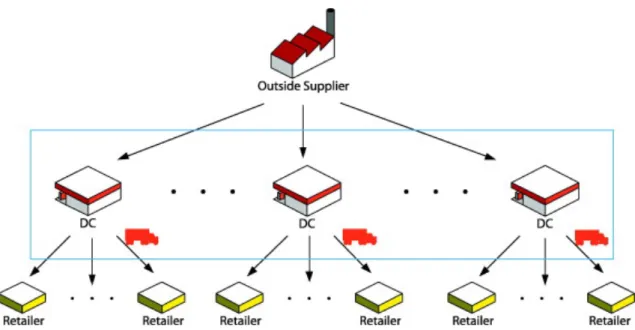

When a distribution center is involved in a retailing supply chain, the typical flow of goods goes from the suppliers in bulk to the distribution center who break bulk, sort and consolidate the goods before sending it to the retail stores (customers) (Craig, Dehoratius, Jiang and Klabjan, 2015).

Figure 5: Multi-level Supply Chain Network (Tsao, 2013)

Tsao (2013) illustrates how a typical supply chain involving distribution centers within retailing can look like with an outside supplier delivering goods to the distribution centers who perform different functions (depending on their role in a specific supply chain) and then sends the goods to the retailers (see Figure 5: Multi-level Supply Chain Network (Tsao, 2013)).

There are a vast amount of different types of terminals acting as distribution centers, all with different functions, goals and roles in the supply chain. Examining the literature provides no clear definition of what a distribution center is since each distribution center is different from another in terms of functions and roles performed.

However, Figure 5: Multi-level Supply Chain Network (Tsao, 2013)

by Tsao (2013) resembles a typical supply chain layout involving distribution centers and similar figures can be found by other authors (Coyle et al, 2013; Lumsden, 2012). The common view of a distribution center is a form of centralized terminal providing several value adding services in the form of handling goods but also administrative functions. Listing all the different functions that a distribution center can perform is simply unrewarding, however there seems to be a consensus between authors that a typical distribution center handles sorting, consolidation and storage of goods as their main functions, with a vast amount of additional functions differing from case to case (Jonsson and Mattsson, 2011; Lumsden, 2012; Tsao, 2013; Coyle, 2013; Craig, 2015).

2.5 Collaboration

Strong relationships through collaboration are more prone to achieve common goals for obtaining the competitiveness of the partners (Chen, Daugherty and Landry, 2009; Whipple and Russell, 2007; Baratt, 2004; Xiande, Baofeng, Barbara and Jeff, 2008). In order to develop and maintain a collaborative relationship Mentzer et. al. (2001) argues that it requires: trust, longevity of the relationship, sharing information, openly discussing processes and systems, leadership, technology and benefit sharing. This is supported by earlier research by Ganesan (1994) that suggests trust, commitment and communication as important requirements for an effective collaboration. All these requirements are necessary as mentioned above to achieve common goals and according to Min, Roath, Daugherty, Genchey, Chen, Arndt and Richey (2005) also achieve improved visibility, higher service levels, increased flexibility, greater end-customer satisfaction and reduced cycle times.

To further clarify the concepts regarding the factors of collaboration, research by Mamad and Chahdi (2013) summarize previous literature and provides seven factors to include when looking upon collaboration issues. Therefore, these factors will be used since it provides a solid based regarding the main conflict factors, which are the following: trust, commitment, communication, information technology, dependence, formalization and control, these are presented more in-depth below.

Trust

There is no distinct definition of trust; according to Ganesan (1994) it can be defined as a belief, a feeling or expectation vis-à-vis an exchange partner that results from its expertise, reliability and intentionality. In a supply chains trust is a multidimensional phenomenon consisting of two components, credibility of an exchange partner and an expectancy that the partner’s word or written statement can be relied on and benevolence (Ganesan, 1994; Doney and Cannon, 1997). Meaning that to which extent a partner is genuinely interested in the other partner’s welfare and motivated to seek joint. Furthermore, trust is a belief of an actor that the other actors in the supply chain will carry out actions that will have positive outcomes (Anderson and Narsus, 1990; Moorman, Deshpandé and Zaltman, 1993). Doney and Cannon (1997) emphasize that “collaborative relationships rely on relational forms of exchange characterized by high level of trust” and according to Ganesan (1994) “the high levels of trust characteristic of relational exchange enable parties to focus on the long-term benefits of the relationship”. Therefore, trust is widely preserved as a major component of collaboration relationship.

The incentive to gain a high level of trust as Mohr and Spekman (1994) mentions is highly related to firms’ desire to collaborate which Anderson and Narus (1990) support and further stated that once trust is established, firms discover that joint efforts can achieve and exceed the outcomes than a firm acted solely in its own best interest would accomplish.

Commitment

Commitment refers to the desire to see the relationships continue in the long-term (Ganesan, 1994), which Morgan and Hunt (1994) also mentions by saying that it is the durable desire to maintain a privileged relationship. This can be related to Dwyer, Schurr and Oh (1987) definition of commitment as a “implicit or explicit guarantee on the continuity between exchange partners”. Furthermore, mutual commitment implies willingness of partners to make sacrifices in the short term to achieve long-term benefits (Dwyer et. al., 1987). Commitment leads to mutual gain and performance for both parties in a supply chain relationship (Tellefsen and Thomas, 2005; Mohr and Spekman, 1994). Both parties can also achieve individual and joint goals without raising the specter of opportunistic behavior, when firms commit to long-term partnerships (Lambert, Emmelhainz and Gardner, 1999). Previous research by El Alaoui, Chakor and Mdaghri (2012) discovered that commitment had a direct and positive impact on performance and is an important indicator of the health of the relationship.

Communication

Early research by Frazier and Summers (1984) stated that communication acts as a process by which information is transmitted. In addition to this, Anderson and Narus (1990) define communication as a formal or informal sharing of relevant information between firms. There are several suggestions why communication is of high value when maintaining the relationships. Moor (1998) argues that partners are both able to act independently to maintain the relationship over time and to reduce uncertainties. Furthermore, Mohr and Nevin (1990) also mention that communication can reduce doubt, mistrust, asymmetric information and opportunistic behavior. But sharing ambiguity information can be damageable for the relationship and research of Zhou and Benton (2007) emphasizes that companies must prevent any ambiguity information to be transmitted between actors. In order to sustain a functional

communication, characteristics that clearly need to be included in the communication strategy are: quality, frequency, direction and content (Mohr and Nevin, 1990). These characteristics are significant factors for a successful collaboration and for long-term performance (Anderson and Narus, 1990).

Information Technology

The use of information technology (IT) strengthens the links between actors in the supply chain (Pramatari, 2007), since IT connect users to facilitate the optimization process in the supply chain (Ahmed and Ullah, 2012). Therefore with IT, adequate formal and informal communication among partners is the basis for the collaboration to grow between them (Anderson and Narus, 1990; Heide and Miner, 1992). Paramati (2007) also state that IT can contribute to reduce transaction costs and limits opportunistic behavior and IT is summarized through Bowersox (1990) who argues that IT is a critical factor if partners are to realize benefits of collaboration.

Dependence

Some authors argue that in order for businesses to achieve their goals, each business depend on their environment and on other organizations for obtaining resources necessary (Kumar, 1996; Lusch and Brown, 1996). This is supported by Pfeffer and Salanncik (1978) who states that companies desire to secure the resources necessary for their survival and development puts them in a position which each is dependent on the other. Dependence is determined by two dimensions, firstly, the “essentiality” of resources and, secondly, the “difficulty of replacing partner” (Kumar, 1996; Heide and John, 1990). To establish interdependence between actors in the supply chain, these dimensions require a mutual dependence. Interdependence is an outcome from a relationship in which actors perceive mutual benefits from the interaction (Mohr and Spekman, 1994). Furthermore, Pfeffer and Salanncik (1978) state that interdependence develops collaboration relationships in order of complementary contributions of each partner and the assets exchanged. In order to achieve mutual beneficial goals of both parties within the supply chain, mutual dependence seem to be the key (Ryu, Arslan and Aydin, 2007).

Formalization

Formalization can be defined as “agreements in writing between two or more parties, which are perceive or intended, as legally binding” (Lyons and Mehta, 1997; Woolthuis, Hillebrand and Nooteboom, 2005), therefore it can also be seen as a formal contract. Other research by Mamad and Chahdi (2013) argues that it is an agreement or a bilateral coordination mechanism by which two parties agree on another’s behavior. In order for stakeholders to overcome the contradictions and control potential hazards that may occur throughout the supply chain, the formalization of collaboration is one of the most effective mechanisms (Mamad and Chahdi, 2013). The formal contract must clearly state the goals pursued and the means to achieve these goals (Ellram, 1995) as well as providing solutions to differences of potential interests (Nickerson and Zenger, 2002; Dekker, 2008). This is critical in order to make an effective collaboration within the supply chain (Malhotra and Lumineau, 2011) and reduce uncertainties regarding the opportunistic behavior of partners and minimize operating costs (Ellram, 1995). Control

Control can be characterized within a supply chain as an incentive to monitor and evaluate in order to to ensure that partners behave as expected (Mamad and Chahdi, 2013). In addition to this, it can also be seen as set of mechanisms and processes, which enables the parties of a chain to ensure that decisions and behaviors developed by them correspond with the objectives (Fenneteau and Naro, 2005). Furthermore, control is considered as a necessity for the efficiency and value creation in a supply chain (Woolthuis et. al., 2005). Therefore, by the use of tracking

devices and monitoring tools, evaluation and monitoring can be accomplished and are needed in order to establish a collaborative framework between actors within the supply chain. As a consequence of this, these devices can set collaborative behaviors (Kanda and Deshmukh, 2008) and to further gain actors motivation in terms of learning and as a safeguard against the risk of opportunism (Williamson, 2008).

Summarization of Conflict Factors

In order to highlight how each factor affects collaboration between actors in the SC, dependant on the level of collaboration, a summary of the theory previously explained within the conflict factors presented by Mamad and Chachdi (2013) can be found below in Table 1: Effects on Collaboration.

Table 1: Effects on Collaboration

Factors Low level High level

Trust

Weak relational exchange, focus on short-terms benefits of the relationship. Not interesting in other party’s welfare and not motivated to seek joint.

Good relational exchange, focus on long-term benefits of the relationship. Interested in other party’s welfare and motivated to seek joint.

Commitment

Unhealthy relationship, negative impact on performance, reduced

possibility to achieve joint goals

Healthy relationship, positive impact on performance, achieving individual and joint goals

Communication

Do not share relevant informal- and formal information, creates uncertainties, doubt and mistrust.

Share relevant informal- and formal information, reduce uncertainties, doubt and mistrust.

Information Technology

Weakens the link between actors, complicates the optimization of SC processes and increases transaction costs.

Strengthens the link between actors, facilitates the optimization of SC processes and reduces transaction costs.

Dependence

Interdependent through non-mutual benefits, seek to provide complementary contribution and assets exchange for own interests.

Interdependent through mutual benefits, seek to provide

complementary contribution of each partner and assets exchange.

Formalization

Harder to overcome contradictions and control potential hazards in the SC with unclear goals and solutions to differences of potential interest and increase uncertainties

Easier to overcome contradictions and control potential hazards in the SC with clear goals and solutions to differences of potential interest and reduce uncertainties

Control

Uncertain if partners perform as expected, may decrease efficiency and value creation in a SC.

Partners perform as expected, may increase efficiency and value creation in a SC.

As mentioned in the background and according to Coyle et. al. (2013) companies no longer compete on one-on-one basis, instead due to the severe competition companies prefer to cooperate to establish functional chains of interdependent companies (Coyle et. al., 2013; Razmi and Haghighi, 2014). According to Barutçu et. al. (2010), this has become a necessary part of competitive strategies and is no longer an option. Sople (2011) mention the importance of the entire supply chain to be closely integration to have the possibility to achieve the common goals for the supply chain.

2.6 Supply Chain Conflicts

A positive and well working collaboration among actors can generate a better outcome of the supply chain performance, which senior management is well aware of. Even though businesses realize the importance of collaboration, still according to Shaiq et. al. (2015) conflicts is an undesired but unavoidable phenomenon of functional interaction either within a company or with chain partners like suppliers, logistics service providers or any other support service provider. Furthermore, operational conflicts have a higher probability to occur in a collaborative network, the higher number of members operating in the chain (Shaiq et. al., 2015). By minimizing number of actors within a supply chain, Min and Zhou (2002) argue that inclusion of all potential actors from different levels might complicate the concept of strategic collaboration. This support Scott and Westbrook (1991) statement that “the number of members in any supply chain collaboration network should not exceed more than the minimum required number to minimize the conflicting goals of different members organizations and to concentrate more on the performance overall supply chain”. To generate a well performing supply chain, the supply chain management is crucial and Baratcu et. al. (2010) argues that one of the major disciplines of supply chain management is conflict management itself.

To further focus on the conflict in relationships, the collaboration and interaction between two parties within a supply chain are as equally important to highlight. Therefore, the conflicts between actors’ relationships can hamper the overall performance of the entire supply chain. The concept of conflicts have different definition and meanings, which according to Thomas (1992) is based on that conflict is a process which initiates quietly when either of the parties starts thinking that his interests are being frustrated by the other party. Looking at the general literature concerning conflicta, it is mostly defined in different ways emphasizing its different characteristics. According to Ramzi and Haghighi (2014) definition, which can be seen as the most comprehensive one, they argue that the conflict is a byproduct of human interaction, “people who are functionally interdependent but perceive conflicting goals, contradictory aims and contrary values and who feel the opposite party is potentially interfering with the realization of the goals, end up having conflicts”. Since a supply chain is purposely crafted with the partnerships involved to achieve similar targets for mutual interests one would believe that common goals would be typical, however according to Shaiq et. al. (2015) the parties involved still often has different if not contradictory targets and missions. If the supply chain is not properly managed it helps breeding conflicts due to it is inherent in the system (Levine, 2012). Reasons that primarily trigger conflicts among supply chain partners and even more specifically between buyers and suppliers are according to Barutcu et. al. (2010) the following:

v Partners in the chain have different objectives v A prevailing sense of mistrust between partners v Weakness in operational structure

v Lack of cooperating spirit

v Substandard quality of communication and providing insufficient information or stating half-truth

Barutcu et. al. (2010) means that different objectives put the focus of supply chain partners in different directions. For example, during collaboration between a distributor and a transportation firm, the distributor’s main objective could be to always deliver on time while the transportation firms main focus could be to always drive with full trucks. These different objectives could create conflicts when decisions whether to drive with a less than full truck load or to not deliver on time has to be made. To point out one reason that is the controlling factor for all other reasons above, Shaiq et. al. (2015) highlights that a prevailing sense of mistrust between partners is the main trigger of conflicts in collaborations between actors. This prevailing sense of mistrust is essentially when supply chain partners have a hard time to trust their collaboration partners’ incentives and reasons for different decisions and actions which makes it harder to come to mutual agreements and decisions and essentially drives the partners further away from each other (Barutcu et. al., 2010).

Weakness in operational structure revolves around facilitators, which enables effective collaboration such as IT systems and operational processes. Having an IT system which forces certain tasks to be done a specific way by supply chain partners or operational processes that become ineffective due to regulations by other supply chain partners or due to how other supply chain partners operate can create frustration and tensions which in turn can trigger conflicts. Lack of cooperating spirit logically creates conflicts if one party within a supply chain collaboration setup tries to cooperate and work for the better of the whole chain while other partners might lack cooperating spirit and are less interested in the collaboration. Basically a lack of cooperating spirit from at least one partner in a supply chain collaboration can create frustration and trigger conflicts when another party compromises and puts energy into a collaboration and get nothing in return (Barutcu et al., 2010).

The last point regarding substandard communication can take form in many ways. A typical scenario would be when one supply chain partner suffers from delays, having to reschedule production, transportation or similar issues due to lack of information or communication from a supply chain partner. However substandard communication can also trigger conflicts in scenarios where one supply chain partner does something that affects other partners without informing them in time, such as switching transportation routes, changing volumes of a delivery or increasing/reducing production volumes during a holiday season. As mentioned above, these five points can be seen as the main triggers to supply chain conflicts where a prevailing sense of mistrust often is a central driver to the other triggers (Barutcu et al., 2010; Shaiq et al., 2015).

2.7 Theory Summary

Through this summary the purpose of each theory previously presented will be clarified and how these are connected to this thesis (see Figure 6: Theory Summary). Since the focal firm and each logistic company operate within a SC, providing theory regarding SCM enriches the understanding of managing entire supply chains. In additional, it enlightens the important factors in order to gain a competitive advantage through solid management, which can be related to how the actors collaborate within the SC. Furthermore, by using the network approach the SC can be visualized and simplified, due to nodes and links that connect the actors with each other creating a supply chain network. This enables the possibility to link the actors looked upon in this thesis, which is the focal firm and the logistics companies, and inform that the link between actors represent relational exchange. This relational connection between actors is according to Edward, Hearnshaw, Mark and Wilson (2013) through contracts and various flow types, such as material flow, information flow and financial flow. Therefore, SCM and network approach provides an overview to this thesis and supports why collaboration and conflicts not only affect two or more actors but rather the entire supply chain.

The focal firm operates as a DC and was previously connected with a 3PL and is currently connected to a 4PL. Therefore, definitions of actors are stated in order to define the three main actors, the DC, the 3PL company and the 4PL company. This also supports what types of flows that creates the link between the logistics companies to the focal firm. In addition to this, by stating the definitions of each actor used in this thesis, enhancement of the analysis and conclusions is made. Furthermore, the focal firm, which is a DC that has earlier outsourced their activities regarding the outbound distribution to a 3PL and now currently to a 4PL. By theory regarding outsourcing it clarifies why actors such as a DC outsource distribution to logistics companies and more specifically how these are linked together.

By narrowing the theories down at the end of the funnel, collaboration and SCC are chosen in order to have the possibility to fulfill the thesis purpose with support from the other theories. Collaboration focus on the actual relationship between actors and what factors to consider in order to establish a solid collaboration setup. If these factors are not thoroughly considered, conflicts may occur and through SCC theory we highlight the typical conflicts within SCs, which is similar to the ones stated in the collaboration theory.

Outline

SCM Outsourcing Network Approach1

stResearch

Question

Collaboration SCC Empirical material2

ndResearch

Question

Research Question I Definition of Actors CollaborationSupplier( Focal(Firm( Customer(

3PL( 4PL( Overview:( • Supply(Chain(Management( • Network(approach( • Actor(>(DC( • Actor(–(3PL/4PL( • CollaboraCon( • Supply(Chain(Conflict( • Conflict(Management( • Outsourcing( Figure 6: Theory Summary

As mentioned above, SCM, network approach and outsourcing are theories providing an overview and are used throughout the whole thesis. Remaining theories will be clarified in Figure 7: Link between Research Questions and Theoretical Framework, by connecting which theory is used for each research question. Additionally, the answer from research question one is also applied in order to enable answering of the second research question.

3

Methodology

This chapter will guide the reader through the methodological choices made by the authors in order to fulfill the purpose of the study

3.1 Research Methodology

This chapter will go through and explain the methodological choices behind this master thesis. The importance of explaining the method properly lies in the ability for others to take your research seriously and accept it (Crotty, 1998). Our choices of different approaches, strategies and methods will be explained through each layer of the “research onion” by Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill (2015) who explain the need to defend and motivate choices in each layer in order for the reader to fully understand choices made within the inner layers of the research onion (see Figure 8: The Research Onion (Saunders et al., 2012)).

The first layer that will be explained is the layer of philosophies which is a term that explains different ways of viewing the nature of reality, what is considered acceptable knowledge and what role values play in the research. The second layer is the research approach which focuses on how you approach your research in terms of theories, generalize of and the use of data and the general logic of how you go forth with your research. The third layer is the layer of strategy which consists of different strategies that you can use in order to achieve the goal of fulfilling the purpose.

The fourth layer is your choice of how you will approach the use of methods by using one or several methods and/or mixing them in order to fulfill your purpose. The fifth layer considers your time horizon for your study where you decide on how you will distribute and use the time available. The sixth and final layer is the data collection and analysis layer which is essentially the hands-on methods you will use to collect and analyze data (Saunders et al., 2015).

All of the layers of the research onion and our choices within each layer will be more in-depth discussed and explained below to motivate the methodological foundation of our study.