ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

Linguistics

and

Education

j ou rn a l h om ep a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / l i n g e d

“We’re

talking

about

mobility:”

Discourse

strategies

for

promoting

disciplinary

knowledge

and

language

in

educational

contexts

Pia

Nygård

Larsson

FacultyforEducationandSociety,MalmöUniversity,20506Malmö,Sweden

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:Received28March2018 Receivedinrevisedform 28September2018 Accepted11October2018 Keywords:

Classroomdiscoursestrategies Metadiscourse

Disciplinaryliteracy Scienceteaching

Systemicfunctionallinguistics Semanticwaves

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Contentareateachershaveacrucialtaskinpromotingstudents’buildingofdisciplinaryknowledgeand language.Thispaperexplores,onanelaboratedtheoreticalfoundation,howsubject-specificknowledge anddiscourseineducationalcontextsmaybediscernedandpromoted.Thestudydrawsondatafrom aninterdisciplinarydesign-basedthree-yearresearchproject.Teacher–studentinteractioninalower secondaryscienceclassroomisexamined,andfindingsfromanalyzedvideo-recordeddatarevealthe complexuseofsemioticresources.Theteacherseekstopromotestudentparticipationandraise aware-nessaboutscientificdiscourse.Inthispaper,theverbalteacher–studentinteractionisvisualizedand described,andtheresultsdisplayadynamiclanguageuse,revealinghowthediscourse,inwavelike pat-terns,graduallymovestowardsdensenominalizedexpressions,alignedwiththefeaturesofdisciplinary discourse.Theresultscontributetotheunderstandingofcontentareateachers’discoursestrategieswhen theyseektofacilitatethedevelopmentofdisciplinaryknowledgeandlanguage.

©2018TheAuthor.PublishedbyElsevierInc.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBYlicense (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Languageandliteracyareembeddedwithinarangeofschool

subjects,along withtheir specialized knowledge. Content,

lan-guage,and other multimodal resourcesare inseparable aspects

inteachingandlearning(Schleppegrell,2016;Unsworth,2001).

Throughout their school years, students encounter increasing

focus on specific knowledge and expanding disciplinary

lan-guage and literacy demands. A school subject canbe regarded

asadisciplinarydiscourse,re-contextualizedineducational

con-text, with specific ways of reading, writing, speaking, doing,

and thinking, which differs from daily perspectives on the

world (Halliday & Martin, 1993). These specific conventions

within disciplinary practices become even more demanding at

the secondary school level. Therefore, it has been argued that

explicit knowledge about and attention to language

(metalan-guage)supportstudents’developmentofcontentandexpansion

ofsemioticresources(Rappa&Tang,2018;Rose&Martin,2012;

Schleppegrell,2016).Teachershavethecrucialtaskof

acknowl-edgingand building upon students’ knowledgesand resources,

E-mailaddress:pia.nygard-larsson@mau.se

promoting the use of various multimodal and multilingual

resources,aswellassupportingthedevelopmentofdisciplinary

lit-eracy(Danielsson,2016;Gebhard,Chen&Britton,2014;Hammond

& Gibbons, 2005; Haneda, 2014; Jakobson & Axelsson, 2017; Macnaught etal.,2013; NygårdLarsson,2011).In otherwords,

classroom activities and teaching strategies need to help fill

students’ “semantic gaps” (Maton, 2013) at the same time as

attempting to empower and engage the students (Cummins,

2014).

Thefocusinthepresentstudyisonhowthebuildingofand

movement towardssubject-specific knowledgeand disciplinary

discourseineducationalpracticemaybediscernedandpromoted.

Morespecifically,thestudyexplorestheeducationalpotentialin

teacher–studentinteractioninaSwedishlowersecondaryscience

classroom.How doestheteacher–studentinteractionintroduce

studentstoscientificdiscourseandwhatstrategiesdoestheteacher

usetopromotescientificknowledgeandliteracy?

To provide a foundation for the findings, the article starts

by exploring and outlining some major theoretical approaches

tobuildingknowledgeanddisciplinarylanguageandliteracyin

educationalcontexts,including perspectivesonhowthe

move-ment towards disciplinary discourse may be understood and

interpreted.Thepapersuggeststhatthegradualbuildingof

dis-ciplinary knowledgeandliteracyin classroomsin additionmay

beconceptualizedasrecurrentmovementsbetweenand within

discourses.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2018.10.001

2. Knowledge-buildingandthelanguageofschooling

2.1. Afunctionalviewoflanguage

Thelanguageindifferentdisciplinesconstitutesanimportant

researchfieldwithintheframeworkofsystemicfunctional

linguis-tics(SFL)(Halliday&Martin,1993;Halliday&Matthiessen,2004).

SFLscholarsmakea distinctionbetweenlanguageusein

every-daycommon-sensecontextsandlanguageuseinthespecialized

practicesofschooling,withtheirvariousdemandsinrelationto

registersandgenresfordifferentsocialpurposes.Language

profi-ciencycanthusberegardedasregisterspecific.Register,according

toMartin,concernslinguisticchoicesinsituationalcontextsand

consistsofthreevariablesrealizedthroughlanguage,whichvary

accordingtocontext(Rose&Martin,2012).SFLreconceptualizes

languageasasemioticthreefoldresourceformeaning-making.The

ideationalmetafunctionrepresentsexperiences,theinterpersonal

maintains relational dimensions, and the textual metafunction

organizestheflow ofinformation. Theregistervariables realize

thesepotentialsinsocialcontexts.Accordingly,languagechoices

and usagevarydepending on(1) ifthetopic, participants,and

eventswithintheregistervariablefield,areeverydayorientedor

specialized.Italsovariesdependingon(2)ifthecommunication

takesplaceincloseandinformalinteractionorismoreformaland

distanced(tenor).Finally,itvariesdependingon(3)theroleoral

andwrittenlanguageandothermodalitiesplayinthetextualflow

ofcommunication(mode).

Writtenacademictextisoftenabstract,distanced,and

techni-cal,typicallydenselypackedwithinformation(Halliday&Martin,

1993).Afteryearsofacademicstudy,knowledgehasbecome

fur-therspecializedand languageprogressivelymoretechnical and

abstract,whichisrelatedtogrammaticalchanges,wherecongruent

andmore“straightforward”expressionsarebackgroundeddueto

morenominalizedmetaphoricalways(e.g.,Halliday,1998)of

con-struingthefield.WithinSFLandgenre-basedpedagogy,theaim

isthereforetomakeexplicittherequirementsplacedonstudents

intheexpansionofliteracydemands(e.g.,Christie&Derewianka,

2008; Fang, Schleppegrell& Cox, 2006).Thus, thegenre-based

literacyapproach comprises an explicitfocus onmetalinguistic

awarenessandcrucialgenres,orstagedrealizationsofsocialgoals,

basedonHalliday’s SFL,Vygotsky’s “zoneof proximal

develop-ment”(ZPD),Bruner’snotionofscaffolding,andBernstein’svisible

pedagogy(Rose&Martin,2012).

2.2. Everydayandacademicdiscoursesineducationalcontexts

The differences and relations between informal discourse

and theacademic and scientific discourseswere highlightedin

Vygotsky’s (1986) distinction between everyday and scientific

concepts,andhavesince beenexploredandelaboratedfroman

SFLperspective(Section2.1)aswellasfromotherperspectives.

Bernstein(2000)distinguishedbetweenhorizontal(everyday)and

vertical(academic) discourseand furtherconceptualized

differ-entkindsof academicknowledgeashierarchicalandhorizontal

knowledgestructures.However,itisimportanttoemphasizethat

theeducationallevel constitutesa pedagogicdiscourse that

re-contextualizesverticaldiscourses.Maton(e.g.,2014)developeda

four-fieldedmodel,thesemanticplane,basedonlegitimationcode

theory(LCT)derivedfromBernstein’ssociologicalframeworkon

codesandknowledgestructures.Theplaneisafieldofsemantic

codes,withthevariablessemanticgravity(context-dependenceof

meaning)andsemanticdensity(complexityofmeaning).This

con-cepthasbeenfurtherconceptualizedwithintheinterdisciplinary

educationalresearchproject(DISKS)(Martin,2013;Maton,2013;

Macnaughtetal.,2013)andexploredinrelationtotheregister

variablesofSFL(Martin,2017;Martin&Matruglio,2013).

According to Maton (2014), the concept of semantic codes

avoidsdichotomous division in everyday and academic

knowl-edge.Thevariationandstrengthofsemanticgravityandsemantic

densitygeneratesemanticcodeswithinsocialfieldsofknowledge

practices(Martin&Maton,2017).Thetransformationof

knowl-edgecanbeviewedasmovementbetweenthesevariablesalong

a continuum of strength. Stronger semanticgravity indicates a

more context-dependent,specific,and concrete meaning,while

weakersemanticgravityimplieslesscontext-dependent,general,

andabstractmeaning.Strongersemanticdensityimpliesa

com-plexcondensationofmeaning,andweakerdensitystandsforthe

opposite.Semanticcodesaresituatedinknowledgepracticesand

canbe usedfor analysingpedagogic discourse (see alsoMaton

&Doran,2017,forlinguistic“translationdevices”).Accordingto

Maton(2014),thefour-fieldedmodelofthesemanticplane(Fig.1)

shouldnotbeinterpretedasseparateboxes.Rather,thestrengths

varyaroundtheplane.Thismeansthatactivitiesanddiscourses

withinpracticesmovebetweenandwithinthesespaces.Thus,all

practicesinvolvevariousstrengthsofsemanticgravityand

seman-ticdensity(SG+/−,SD+/−).

Fig.1. Thesemanticplane,orthefieldofsemanticcodes,adaptedfromMaton(2014).Semanticgravity(SG−/+)isthedegreetowhichmeaningrelatestoitscontext.Semantic density(SD−/+)isthedegreeofcomplexityandcondensationofmeaning.

Fig.2. Theteachingandlearningplane.Asecond-languageperspectiveonthedegreeofcontextualsupportandcognitivecomplexityinclassroomactivities(adaptedfrom Cummins,1981;Gibbons,2009;Mariani,1997).Inthepresentpaper,theaxesareturned:“contextualsupport”isnormallyplacedonthehorizontalline(higherdegreeto theleft),and“cognitivedemandsandchallenge”ontheverticalline(higherdegreeonthetop).

Froma second-languageperspective, Cummins(1979, 2000)

explored the language challenges related to school success

and developed the distinction between BICS and CALP (basic

interpersonalcommunicativeskills;cognitiveacademiclanguage

proficiency),oreverydaylanguageandacademiclanguageskills.

Cummins(1981) developedthese conceptsfurtherintoa more

dynamic educational four-fielded model, which combined the

degrees of cognitive demand and contextual support. Cummins’s

modelhasbeenrelatedtoafour-fieldedmodelofteachingzones

(Mariani,1997),comprisingthedegreesofchallengeandsupport,

whichothers,includingGibbons(2009),developedfurther.These

modelsareillustratedincombinationinFig.2.However,themodel

ispartlyreversedinthepresentpaper,withturnedaxes,inorder

tobemoreadaptedandcomparabletotheaxesinMaton’smodel

(Fig.1).

Accordingly,classroomtaskswithhighdegreesofboth

chal-lengeandsupportare,formanystudents,likelytoofferaneffective

scaffoldingdevelopmentalzone(thelower-rightzone,Fig.2),

con-taining rich contextual support such as practical assignments,

groupwork,interactionalnegotiation,visualaids,and

acknowl-edgementofstudents’backgroundknowledgeandfirstlanguages.

Inthiszone,studentshavetheopportunitytomanagecognitively

demandingtasksand,withtherightsupport,headtowardsstudent

autonomy(Gibbons,2009;Mariani,1997).Typically,thelower-left

zoneisdominatedbyordinarydailyinteractionsandexperiences,

whiletheupper-rightzonecomprisesmoredemandingacademic

taskssuchas writingessays. The upper-leftzone, inturn,

con-sistsoftasksthatstudentscanperformrelativelyeasily,without

processing.

The LCT model (Fig. 1) comprises a sociological

epistemic-semanticperspective,whilethesecond-languagemodel(Fig.2)is

orientedtowardslanguageusageandclassroominstruction.

How-ever,bothareusedaseducationalmodelsandaddperspectivesto

theexplorationofknowledge-buildingandthelanguageof

school-ing.Theemphasis intheLCTmodelisstrongregardingthefact

thatactivitiesanddiscourseswithinpractices“movearoundthe

plane”andvaryinstrength.However,thisisalsounderpinningthe

second-languagemodel,althoughitstressesthedevelopment

fac-tor.Thefollowingsectionswillfurtherexplorethecomplexityand

varietyofknowledge-buildingineducationalcontexts.

2.3. Semanticwavesandscaffolding

AccordingtoMaton (2013,2014),weakeningsemantic

grav-ity involves moving from the specific and concrete towards

more context-independent, general, and abstract meaning.

Fig.3.Twosimplesemanticprofilesonatime-line:ahighsemanticflat-line(the straightlineatthetop)anda“semanticwave”(thecurvyline),adaptedfromMaton (2013)andMacnaughtetal.(2013).

Strengthening semantic density means a movement towards

more complex and condensed constellations of meanings. The

DISKSprojectusesthenotionof semanticwaves(Martin,2013;

Maton,2013)todescribeandillustratetherecurrentmovements

in pedagogic discourse. In these analyses, the semantic codes

arecombinedinsemanticprofiles,whichtracechangesovertime

withinpractices,suchastheunfoldingofclassroompractice.In

other words, the semantic profile comprises and displays the

continuousstrengthsofbothcontextdependencyandcomplexity.

When illustrating semantic profiles, the variables of semantic

gravityandsemanticdensityarecombinedintwopoles(SG+/SD−

andSG−/SD+)(Maton,2013).Forthesakeofsimplicity,theDISKS

projectusedascaleinwhichsemanticgravityandsemanticdensity

moveinversely,thusnotinvolvingotherpossiblecombinationsof

thepoles(SG+/SD+,SG−/SD−).Ona time-scale,semanticwaves

occurwhenthereisavariationinstrengthandawidersemantic

range between thepoles. Low or highflat-lines,in turn, occur

whentherearelimitedshiftsindiscourse,andthereforedonot

displaythiswavingpatternonthetime-scale(Fig.3).

Maton (2013) and Macnaught et al. (2013) point out that

teachersoftenunpackdensewrittendiscourseintomore

context-dependent spoken discourse. However, teachers more seldom

repack, or model upwardshifts and create wavesby returning

tomorecondensedandcomplexmeanings.Thequestionis,how

canclassroomactivitiesmediatewrittendiscourseandavoidthis

“semanticgap”(Maton,2013)?Teachersandstudentsneedtoboth

unpackandrepackthenegotiatedmeaning,and“teachingtowave”

canthereforeserveasadiscoursestrategyforstudent

empower-ment(Martin,2013;Maton,2014).

Semantic profiles can be analyzed onmacro-level, between

practices,and onmicro-level,within(partof)practices (Maton,

2014).Thus,waveswithinwavescanbeconceptualizedas

ThismaybecomparedtoHammondandGibbons’(2005)notionof

teachers’scaffoldingonmacro-andmicro-levels,withtheaimof

“supporting-up”andextendingdiscourse,ratherthan

“dumbing-down” and simplifyingthe curriculum, in relationto Mariani’s

(1997)conceptualizationofscaffoldingasacombinationofhigh

challengeandhighsupport.AccordingtoHammondandGibbons

(2005),macro-scaffolding,or“designed-in”scaffolding,comprises

plannedtasksequencingthatinvolvesmetalinguisticawareness,

backgroundknowledge,andchoicesoftasksandparticipant

struc-tures(pair,group,whole-class).Micro-scaffolding,or“contingent”

scaffolding, in turn, includes moment-to-moment interactional

scaffolding, such as linking to prior experience and pointing

forward,summingupandrecapping,appropriatingstudents’

con-tributions,thenrecasting andexpanding intomore disciplinary

discourse by extending the third move in the three-part

IRF-exchangeInitiation,Response,Feedback.Moreover,Gibbons(2006)

conceptualizesoraldiscourseasabridgetowriting.Thatis,building

of academicknowledge and languageis supported bya

bridg-ingmovementalongamodecontinuum(theSFLregistervariable

mode), from oral small-group talk and hands-on activities, via

extendedwhole-classtalk,toformalwrittencommunication.

2.4. Semanticwavesfromafunctionallinguisticandmultimodal

perspective

Within the DISKS project, Martin (2013) outlines how the

buildingoftheregistervariablefieldthroughtechnicality(“power

words”)strengthenssemanticdensity.Atechnicaltermisoften

partof a complex web of meanings.Scientific taxonomies are

considerablydeeperthaneverydayonesandre-contextualizedin

pedagogicdiscourse(Halliday&Martin,1993).Learning

techni-caltermsinvolvesexpanding thesemeaningnetworks,through

unpackingandrepacking.Thatis,theyneedtobeelaboratedin

classroom interaction and specified in relation to the patterns

ofactivitysequencesandtaxonomies(Martin,2013).Accordingto

Martin,fieldsaresystemsofactivitysequences(e.g.,implication

sequences,temporal sequences).Theyinvolveprocessesaswell

astaxonomies,organizedbyclassification(kindsof;typeand/or

subtype) and composition (parts of; part and/or whole). These

field-aspects,activityandtaxonomy,organizetheknowledgein

interplayandleadfurthertonewdefinitionsandextended

descrip-tions and explanations in written and multimodal texts, thus

relatedtothenotionofgenreandgenre-basedpedagogy(Martin,

2013;Rose&Martin,2012;Unsworth,2001).Inrelationto

seman-ticwaves,thesetwofield-aspectsconstitutemovementsbetween

definition and classification (upward shifts towards condensed

meaning)and phasesof descriptionandexplanation(downward

shiftstowardsspecifiedandelaboratedmeaning).

From the perspective of SFL, grammatical metaphor (e.g.,

Halliday,1998)iscrucialforknowledge-building,andtechnicality

andsemanticdensitydependsonthis“powergrammar”(Martin,

2013).Furthermore,it allowsa movement towardsabstraction,

whichaffectssemanticgravity.Theconventionalcongruentway

ofexpressingmeaningistherepresentationofprocessesinverbal

groupsandtherepresentationofentitiesinnominalgroups.

Expe-rientialmetaphorrealizesthemeaninginincongruentways,suchas

representationofprocessesinnominalgroups.Therefore,

nominal-izedtechnicalterms,suchas“inflammation,”involvebothentity

and action, thereby posinga double, or metaphorical, meaning

(notably,notallnominalizationshavethisdouble,or

metaphori-cal,meaning).Furthermore,somenominalgroupscontaincomplex

activitysequences,forinstance“celldivision.”Processescanalsobe

realizedthroughadjectives(“livingspecies”),whichmaybecalled

adjectivization.Thisexperientialmetaphorissimilarlydensifying

andmayfacilitatescientific description(NygårdLarsson, 2011).

However, these“hidden” metaphorical meanings canbe partly

unpackedandrepackedintheclassroom.

Inaddition,arangeofsemioticresourcesisintertwinedwith

knowledge-buildingandcontributetothemultimodal

construc-tion of school subjects (e.g., Unsworth, 2001). Nygård Larsson

(2011)uses thenotionof discoursemobilityordiscursive

mobil-itytodescribethemultimodaltwo-waymovementbetweenand

withindifferent discoursesand their inherent,specific ways of

thinkingandacting.Thismobilityinvolvesmovementsbetween

commonsenseandun-commonsensemeaning,aswellasconcrete,

abstract,specific,andgeneralmeaning.Ahighlevelofdiscursive

mobilitymayimplythatteachersconsciouslymovebetween

dif-ferentexpressionstomaximizelearningopportunities.Similarly,

studentsneedtodeveloptheirdiscursivemobility,in stepwith

theexpansionof the literacydemands. Everydaylinguistic and

multimodalexpressionsmayconstitutearesource.However,the

potentialfor teachingandlearningliesinthemobility between

andwithindiscoursesandmodalities.Consequently,thereare

sev-eralconnectionstotheconceptofsemanticwaves(Martin,2013;

Maton,2013).

Examplesofthisdiscursivemobilityfromanethnographicstudy

(NygårdLarsson,2011),aretheuppersecondarybiologyteacher’s

acknowledgementof both verbiage and imagein thetextbook.

Naturalistic (everyday) and abstract technical images (Kress &

van Leeuwen, 2006) are explicitly interpreted and interrelated

in classroom interaction,providing thestudents various

repre-sentationsoftheobject.Thisleadstomovementsthatcomprise

concreteandabstract,aswellasspecificandgeneralobjects,such

asitems,colourphotographs,andanalyticaldrawingsdisplaying

classificationorcomposition.Furthermore,activitysequencesand

taxonomies(Martin,2013)areoftenvisualizedthroughwritten

boardnotesininterplaywiththeseimages.Moreover,theteacher’s

oralinteractionisnotsimplifiedbutextended,rewordingstudents’

responses and unpacking and repacking movements

compris-ingcongruentandincongruentgrammaticalrealization(Halliday,

1998).The implicit taxonomic relations in the textbook are in

additionexplicitlyacknowledgedintheteacher’srecurrent

visual-izationsoftaxonomicrelationsintheclassroom,creatingsemiotic

coherenceintime and space,onboth macro-and micro-levels.

Finally,theteachermodelsanddiscussesexplicitlyhowthe

con-struingofabstractandgeneralimages,derivedfrommoreconcrete

and specificimages, canserve astools inscientific

knowledge-buildingandthinking.Inotherwords,thereisameta-discussion

aboutmultimodalscientificdiscourse,althoughnotsomuchabout

metalinguisticaspectsofthisdiscourse.

3. Thestudy

The focus in this study is on the building of and

move-menttowardsmoresubject-specificknowledgeanddisciplinary

discourse in educational context. More specifically, how does

teacher–studentinteractioninascienceclassroomintroduce

stu-dentstoscientificdiscourse?Whatstrategiesdoestheteacheruse

topromotescientificknowledgeandliteracy?

Theanalysesdrawondatafromtheinterdisciplinaryresearch

project,ScienceandLiteracyTeaching.Theaimofthethree-year

project is to explore and enhance the development of

knowl-edge,language,andliteracyinscienceteachingandlearning,by

observingnaturalsettingsandtheenactmentofdesign-based

col-laboration(Deen,Hajer&Koole,2008;McKenney&Reeves,2013).

ThefulldatasetcomprisesclassroomdatafromtwoSwedishlower

secondaryschools,includingsurveysandinterviews,anddatafrom

asubsequentprofessionaldevelopmentliteracyprogrammeatone

wasconductedby following ethicalguidelinesasstated bythe

SwedishResearchCouncil(2017).

Thedatainthepresentpaperweretakenfromaninitial

sub-studyinoneschool,witha scienceteacherand agrade 7class

withstudentsaged13–14.Thescienceteacherhadlimitedtraining

inlanguage-relatedissues.However,hesharedtheattemptofthe

schooltodevelopstrategiesforalanguageapproachonteaching.

Ingrade7,about40%haveafirstlanguageotherthanSwedish.The

grade7classinthispaperconsistsof27students,and37%report

thattheyhaveafirstlanguageotherthanSwedish.Sixstudents

werebornabroad,whereasthreeofthemarrivedbeforeschooling.

The data from this class consist of classroom observations,

videoandaudiorecordings,students’assignments,photos,andfour

video-recordedinterviewswiththeteacher.Theteacherandthe

classparticipatedintheprojectfornearly2months.Theclassroom

datacomprisesfiveweeksofobservation,consistingofsix

one-hourvideo-recordedlessons.Thisperiodwasfollowedbyoneweek

ofinterventionalcollaboration.Thedesignofthelessonsduring

thisweekwasrealizedandflexiblyenactedbytheteacher,based

onproposalsfromanddiscussionswithmembersoftheresearch

project(MaaikeHajer,AndersJakobsson,PiaNygårdLarsson,Clas

Olander).Inthepresentpaper,thisenactmentinclassroomsetting

isanalyzedandthefocusisthewhole-classinteraction.The

video-recordedclassroomdatafromthis weekconsistoffourlessons,

about3.5hintotal,resultingin10hofrecording.Threecameras

recordedfromdifferentanglesandhaveallbeenusedinanalysis

andtranscription,toachievegreateraccuracy.

Intheexcerpts(Section4),theteachers’talkismarkedTand

thestudents’talkismarkedS.Tosomeextent,adaptationismade

towrittenlanguageconventions.Exactpronunciationandprecise

measurementsofthepausesareexcludedintheSwedishtranscript

andtheEnglishtranslation. Punctuation marks(fullstop,

ques-tionmark)areused.Inaddition,commasareusedintheEnglish

translationforbetterreadability.Omittedpartsoftranscriptare

markedwith/.../.Contextinformationis addedwithinbrackets

[writes].Extra-boldtypeintheexcerptsmarksanalyticalfindings.

Inexcerpts2–5,theSwedishtranscript(italictype)isplacedbelow

theEnglishversion.

3.1. Theinstructionalphasesofthedesignedlessons

Manystudentsintheclassshowedalowdegreeofparticipation

inclassroomwork,andaccordingtointerviewswiththeteacher,

thereweredifficultiesinengagingthestudents,exceptfora

cou-pleofhigher-performingstudents.Therefore,asastartingpoint,

themutualaimfortheteacherandtheprojectgroupwasto

pro-motestudentparticipationandengagementandraiseawareness

aboutscientificdiscourse.Hence,intheintroductionofanew

work-ingareawithinbiology(“Whatislife?”),theteacherconsciously

attemptstoengagestudentsinthefieldandmakethemawareof

thediscoursebymakingconnectionsbetweenstudents’wordings

andmorescientificdiscourse,atthesametimealternatingbetween

participationstructures(small-group,whole-class),duringthree

macro-phases.Belowfollowsanoverviewanddescriptionofthe

instructionalphasesofthedesignedlessons.

(1)Thefirstlessonstartswithanexplorativegroup-work,withfour

studentsineachgroup.Atfirst,thestudentsindividually

con-siderfourobjectsinfrontofthemonthetable(stone,worm,

pottedplant,potato).Theymustdecide,andwritedown,on

asharedfour-fieldedpaperinthemiddleofthetable,which

one of the items should be excluded and why. Then, they

aresupposed toread anddiscusstheanswers, andarriveat

a mutualdecision, whichtheyareinstructedtowritedown

in thecentre ofthepaper.Thiswork,drawingonstudents’

backgroundknowledge,isfollowed byawhole-class

interac-tioninwhichthechoicesarediscussed.Here,theteacher’saim

isalsotomakeconnectionsbetweenstudents’wordingsand

morescientificdiscourse.Thus,thisphasefollowsthepattern

“Individually–group–wholeclass.”

(2)Inasecondexplorativegroupwork,eachgroupreceivesan

enve-lopewith18picturesoforganisms(colourphotography),and

theyareinstructedtodiscussanddecidesuitablecategorizing.

Eachgroupgluesthepicturesonaplate,accompaniedbysome

writinganddrawing(labelling,shortdescription,arrows).This

work is followed by a whole-class interaction in which the

groupsreporttheirfindings,undertheguidanceoftheteacher.

Theplatesarethendisplayedontheclassroomwall.

(3)In a thirdgroup work,thestudents immersethemselves (in

expertgroups)inoneanimalspecieseach.Theyreadinthe

text-bookandsearchonInternet,andtheywritedowntheirresults

accordingtospecificwritinginstruction.Thisworkshouldlater

bereportedininter-groups.However,thismacro-phaseisonly

partiallyrealizedduetoexternalcircumstances.Instead,the

group-workisconcludedbyashortwhole-classinteractionin

whichtwoaspectsconcerningthespeciesarehighlightedby

theteacher.

Unfortunately,afterashortschoolholiday,theteacherdoesnot

returntotheschoolfortheremainingschoolterm,andbythat

ourcollaborationwiththeteacherandhisclassisinterrupted.Still,

theanalysesrevealsignificantfindingsinrelationtothetheoretical

underpinningoutlinedinSection2.

3.2. Analyticalapproach

Onamacro-level,theinstructionalphases(Section3.1)seemto

promoteagradualmovementtowardsmoredisciplinary

knowl-edgeandlanguage.Inrelationtotheteachingandlearningplane

(Section2.2,Fig.2),thephasesseemtobemainly,butnotentirely,

situatedinthelowerrightzoneandslowlymovingupwardsand

totherightwithinthiszone.Thisgradualmovementiscombined

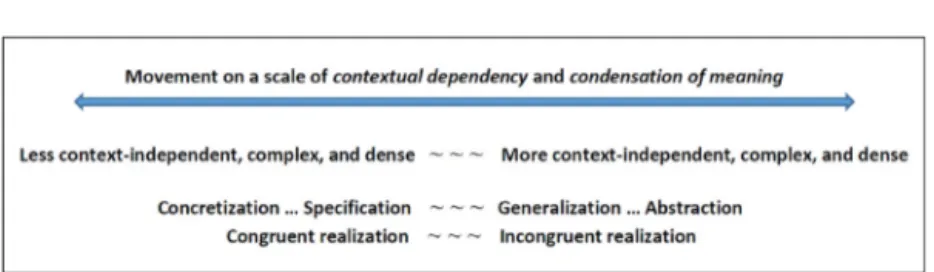

Fig.5.Thescaleofcontextualdependencyandcondensationofmeaning,adaptedfortheanalysesofteacher–studentinteractioninthisstudy.

with recurrent movements between explorative student-active

exercisesandteacher-led,subject-specificelaboration,which

com-prisemultimodalgroup-workinvolvingitems,pictures,drawing,

talking, and writing, and more language-oriented whole-class

interaction(Fig.4).

Thefocus ofthe case studyin this paperis thewhole-class

interactionsduringthesephases,andthefindingswillpresentthe

micro-wavingpatternwithintheseinteractions.Inlinewiththe

theorizationsinSection2,theanalysesdrawonthenotionsof

con-textualdependency,condensation ofmeaning, semanticwaves,

anddiscursivemobility(e.g.,Martin,2013;Maton,2014;Nygård

Larsson,2011).Thenotionofsemanticwavescanbeusedin

anal-ysesatvariouslevels,includingbothqualitativeandquantitative

comparativeapproaches (Macnaughtet al.,2013; Maton,2014).

Theconceptisusedinthepresentstudyforthecloseexamination

oflanguageuseinclassroomdiscourse.However,Maton’s(2014)

model(Section2.3,Fig.3)isreversed,illustratingclassroom

inter-actiononahorizontalscale,rangingfromlefttoright,insteadof

vertically.Thesemovementsconstituteacontinuousscalewithno

exactlimits.Fig.5displaystheoperationalizationofthemodel.

Withinaresearchprojectonlanguageuseinscienceeducation,

asimilarreversedmodelwasusedtotracechangesinstudents’oral

groupinteractionregardingmovementsbetweeneverydayand

sci-entificdiscourse (NygårdLarsson &Jakobsson, 2017).However,

themodelinthepresentpaperisfurtherelaboratedintermsof

howitdescribestheaspectsofthescale.Furthermore,thepresent

studyespeciallyfocusesonthemovementbetweencongruentand

incongruentrealizationofmeaning(e.g.,Halliday,1998),although

otheraspectsinFig.5arealsopresent.Incongruentrealizationis

conceptualizedasamorenominalizeddiscoursecomprising

nomi-nalizationsandadjectivizationsformingvariousdenseexpressions

withanunderlying“double”meaning,whichmayoccuras

gram-maticalmetaphors intexts. Grammaticalmetaphor realizesthe

meaninginincongruentways;forexample,representationof

pro-cessesinnominalgroups(nominalization,suchas“rapidgrowth”),

orrepresentationofprocessesthroughadjectives(adjectivization,

suchas“livingspecies”).Amoreconventionalandcongruentway

ofexpressingmeaningistherepresentationofprocessesinverbal

groups(forexample,“theylive,and theygrowfast”).AsMartin

(2013)points out,grammatical metaphor strengthenssemantic

density,asit iscrucialfor knowledge-buildingandtechnicality.

Italsoaffectssemanticgravity,asitallowsamovementtowards

abstraction(Section2.4).

Thus,themodelinFig.5isusedasananalyticaltoolthatserves

asameantoexamineandinterpretthevariedlanguageusage

dis-playedinclassroomdiscourse.Thereby,thefocusisnotmainlythe

interactionalexchangesperse,butratherthelinguisticmovements

inthediscourse.Furthermore,themodelprovidesvisualizationof

thediscourse(e.g.,Section4.1,Excerpt2),whichmayfacilitatethe

understandingof thedynamiclanguageuseineducational

con-texts.

4. Findings

Thegradualbuildingofknowledgeandlanguageineducational

contextsmayinadditionbeconceptualizedasasimultaneouslyand

constantmovementbetweenandwithindiscoursesorasa

wav-ingpatternofvariousstrengthsregardingcontextualdependency

andcondensationofmeaning(Martin,2013;Maton,2013;Nygård

Larsson, 2011). The findings focus analyses of teacher–student

whole-classinteractionduringthethreemacro-phases(see

Sec-tion3),revealingawavingpatternofcongruentandincongruent

discourse(Halliday,1998).

4.1. Phase1

Thefirstlessonstartedwithanexplorativegroup-work(Section

3.1),whichgavethestudentstimetothink,discuss,andwritedown

theirconclusions.Then,inthewhole-classinteraction,theteacher

initiallystated thathe wantedtohearthestudents’ arguments

aboutwhich object shouldbeexcluded and why.The students

suggestedthestone(Excerpt1).

Excerpt1.Teacher–studentinteraction.Teacher(T).Students

(S),numberedaccording tofirstappearance.Extra-boldtype in

theexcerptsmarksanalyticalfindings.Swedishtranscriptistothe

Mostofthestudents’argumentsduringwhole-class

interac-tion are connected to an everyday discourse (e.g., turn 2 and

6, Excerpt 1), in line with theanswers on the studenttablets

during group-work. This will also be evident in the

follow-ing excerpts. There is one exception, however. S2 (Excerpt 1)

uses theterm “organic” and the common-sense argument “it’s

hard” (8). Whenthe teacher asks him to clarify (9), he easily

extendshisstatementandmovesbetweenvariousarguments(10,

12): “It doesn’t consist of organic substances,” “it’s not alive,”

“the stone is foundon othercelestial bodies,”“it doesn’tneed

water.”

Initially,theteacher’sfeedbackonstudents’suggestions

con-sistsmainlyofrepetition,orallyandinwriting(e.g.,Excerpt1,turn

3,5).However,theteacherrapidlyseekstoexpandthestudents’

wordingsintomoredisciplinarydiscourse.Excerpt2displaysthe

students’argumentsabouttheremovaloftheworm.Theteacher

attemptstotransformthesesuggestionsintomoresubject-specific

wordings,andheseekstowriteeverydaywordingtotheleftonthe

board,andmoresubject-specificwordingtotheright.He

explic-itlytellsthestudentsthattheaimistofindtheseexpressions(7),

andheoccasionallydiscussesspecificwordchoices(9,“Shouldwe

rewriteitlikethat?”).Moreover,theteacher’sdisciplinarywording

ispartlyincongruentandabstract,whichbecomesvisibleinboth

speechandwriting.Excerpt2visualizesthismovement,onascale

fromlefttoright(seeFig.5,Section3.2).

Excerpt 2. Visualization of the teacher–student interaction.

EnglishtranslationisfollowedbySwedishtranscript(initalics).

InExcerpt2,threestudentsgraduallyexpandtheargumentsfor

thewormtobeexcluded:“It’stheonlyonethatisananimal(2),

“It’stheonlyonethatmovesonitsown”(5),“It’stheonlyonethat

canmovewithmuscles”(8).Theteacherthenexpands,bothorally

andinwriting,bysuggestingseveralmoreincongruent,abstract

anddenseexpressions(6,9,11):“abilitytomove,”“movement,”

“transportation,” “mobility” (in Swedish “förmågaatt röra sig,”

“rörelse,”“förflyttning,” “rörelseförmåga”). Student S3seemsto

seekamorespecificargumentwiththeproposal“canmovewith

muscles”(8).This inturnseems tocausetheteachertofind a

more appropriate wording, and he then decides torewrite by

usingtheword“mobility.”Thus,theexcerptdisplaystwodistinct

waves,peaking at thewordsmovement and mobility. However,

theSwedishword“rörelseförmåga”(mobility)isinEnglishrather

“movement-ability.”Thatis,thenominalizationthattheteacher

writesontheboardisadensecompoundword,graduallyderived

from theprevious incongruent wordings, which in turn builds

uponthecongruentwordingsofthestudents.

Thereafter (Excerpt 3), theteacher explicitly states that the

conversationisabout“mobility”(theSwedishword“rörlighet”).

Further,hefocusesmobilityasageneralprocessandexpandsby

askinganadditionalquestion,relatedtomobilityofthespecific

plantandpotato:“Aren’tthesemobile?”(1).Astudentresponds,

“Ithinktheygrow,buttheydon’tmove”(2).Theteachersuggests,

inhisfeedback,thecongruentexpansion“Theygrowandget

big-ger”(3),whichheimmediatelytransformsintothenominalization

“growth”(5) andexplicitlysuggestsasageneralcriterion.

Con-sequently,theacademicnoun“growth”(“tillväxt”)isnowused,

derivedfromtheverb“grow”(“växer”),andbythatanotherwave

Excerpt 3. Visualization of the teacher–student interaction.

EnglishtranslationandSwedishtranscript.

Thus,intheseexchanges,theteachermodelshowactionsare

turnedintoentities,whichcanbeusedascriteriaandfurther

dis-cussed. Thatis, themovementtowards adisciplinary discourse

is realizedthroughincongruent expressions. Excerpt4 displays

anadditionalexampleofthismovementtowardsabstractionand

subject-specificwordings.Theteacherinitiatesbyaskingforother

Excerpt4.Visualizationoftheteacher–studentinteraction(S2

alsoparticipatesinExcerpt1).

S1respondstotheteacher’sinitiationbysuggesting“Theyneed

watertobreathe”(2). Theteacherappropriatesthis suggestion,

both orallyand in writing, and in an extended third move, he

repeatsthecongruentwordings“needwater”and“needtobreathe”

severaltimes.He thenexpands byconcluding that thespecific

useofgills meansthatitis notreallyaquestionoftheprocess

ofbreathing.Healsoasksforamoresubject-specificwording(3).

S2suggests“oxygenintake”(theSwedishcompoundword

“syrein-tag”)(4).Consequently,anotherandmoregeneralnominalization

fortheprocessissuggested.Thiscausestheteachertorepeatthe

termandmovethediscoursetotheleft,byexpandingand

clari-fyingwiththecongruent“it’soxygenthattheyneed”(5).Hethen

extendsbymovingtotherightagain,withtheincongruent“need

foroxygenintake”(6).Finally,heconcludesbyaddingtheeven

moredisciplinaryterm“respiration”(6).Hence,intheinteraction,

connectionsareestablishedbetweenthesevariouswordingsand

thewavingpatternpeaksatthewordsoxygenintakeandrespiration.

Asawrittenproduct,thefollowingnotesarevisualizedonthe

board(Fig.6).Totheright,thenotesconsistmerelyofacademicor

subject-specificwordingsandnominalizations.

Whatstartedasarelativelycontextualdependentand

explo-rativegroup-work,nowmodelsacademiclanguagefeatures.This

includesamultimodalmovementfromartefactstoabstractoral

andwrittenwordings.Inotherwords,contextualindependency

and condensation of meaning strengthens, as the content is

“packed”intheinteraction(Martin,2013;Maton,2013).However,

theincongruentwordingsarenotexplicitlyhighlighted,perse.

4.2. Phase2

Excerpt5isfromthewhole-classinteractionfollowingupon

thesecondexplorativegroup-workbasedonstudents’background

knowledge(categorizationoforganisms,seeSection3.1).Asin

pre-viousexcerpts,itshowsasimilarmovementbetweencongruent(2,

6)andincongruent(3,7)expressions,andaquiteintensewaving

pattern.Here,adjectivizationsareusedforconstruingdescriptive

Fig.6. Copyfromtheboard.EnglishtranslationandSwedishoriginal.“Celestialbodies”totheleftmayseemsurprising.However,inSwedish,theword“himlakropp”may beslightlymoreassociatedwitheverydaydiscourse.

Excerpt 5. Visualization of the teacher–student interaction.

EnglishtranslationandSwedishtranscript.

Thisinteractionalsorevealstwointerestingquestionsposedby

thestudents(9,11).S3asksforclarificationaboutwhether“water

living”isthesamethingas“theyliveinwater”(9),whichis

con-firmedbytheteacher(10).Thisquestionsuggeststhattheuseof

moreincongruentwordingposesachallengeforsomestudents.

However,S11freelyusesbothcongruentandincongruent

word-ings,toreflectuponthecriteriaforcategorization(11,“Theyfly

aroundin theair...Butdo theycountas‘landliving’?”).Here,

theteacher’sfeedbackalsorevealshispositiveconfirmationofthe

students’explorativereasoningaboutclassification(12,“...These

couldbedividedintoflyingand‘landliving’...”).

Atthebeginningofphase2,theteacherexplicitlyhighlighted

classificationasadisciplinaryactivity.Inalinguisticallyextended

instruction,he referredtothe firstgroup-workwhile

Fig.7.Twoexamplesofstudents’categorizationoforganisms.

Fig.8. Teacher–studentinteraction–asummaryonaword-level.

andincongruentexemplifyingwordingsreferringtoclassification

(extra-boldtype below). Consequently, by using several

nomi-nalizations and dynamic verbs (material processes, Halliday &

Matthiessen,2004),hemovesbetweenthegeneralscientific

pro-cessandtheactiveworkofthestudents:

Thenyou’retalkingaboutdivision.Doyouagreethatwehave

made a division? You’ve selected criteria for what should

beexcluded, didn’tyou?Actually,that’stheway a biologist

works...It’softenaboutclassification.Todivide/.../You’llnow

getsomepictures,andyou’llsortthem,likeabiologistdoes.

Howdoyougroupthem?...AndIwantyoutofindarguments

forhowyoudidit...

(Dåärniinnepåuppdelning.Ärnimedpåattvigjorten uppdel-ning?Niharsjälvavaltutkriterierförvadsomskaborteller

hur?Detärfaktisktsåsomenbiologarbetar...Dethandlar

mycketomklassificering.Attdelaupp/.../Niskanufånågra

bilderochniskasorterauppdemsåsomenbiologgör.Hur

grupperarmandem?...Ochjagvillattnihittarargumentför

hurnihargjort...)(Excerpt6,EnglishtranslationandSwedish

transcript)

Attheendofphase2,theteachertellsthestudentstohangtheir

platesonthewall.Fig.7providesanoverviewoftwoexamplesof

studentcategorization.Themultimodalplatesdisplaycategories

suchas“liveonland,”“waterliving,”“animalsthatcanmove,”

“edi-ble.”Thesearenowvisualizedonthewall,andtheclassifications

maylaterbeextended.Furthermore,theplatesjointlydisplayboth

congruentandincongruentwordings,althoughnotequallyspread

overtheplates.

In addition, the whole-class interaction in phase 2 serves

anotherfunction.Whenthestudentsreportontheirfindings,the

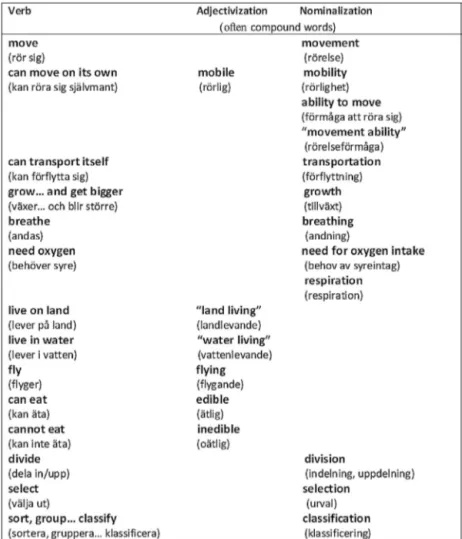

Fig.9.Thewritinginstructions.EnglishtranslationandSwedishoriginal(boldtypeisanalyticalmarking).

supportingthestudentstoidentifyandlabelthespecificspecies,

suchas“seaurchin.”Thatis,theclassifyingmovementcomprises

bothspecificandgeneralcategories.Whenconcludingphase2,the

teacherintroducesthebiologytextbookandthechapterof

organ-isms(systematics),whichtheywilluseinthenextphase.Healso

contextualizesandconfirmsthestudents’worksofar:

Thisishowyou’vebeenworkingtoday.Youfoundyourown

selection,asabiologistdoes.[quotingthebook:]“Theforesthas

itsorganisms,andtheseahasitsown.Alifeintheairrequiresa

completelydifferentbodythanaquietlifeonthebottomofthe

sea.”Andyou’vealsothoughtaboutair,bottomofthesea,land.

You’rethinkinglikeabiologist.(Excerpt7)

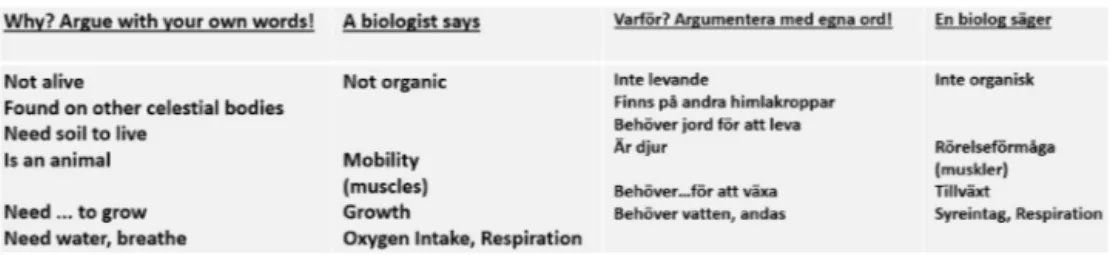

4.3. Asummaryonaword-level

Fig.8summarizes,onaword-level,thecongruentand

incongru-entrealizationsintheinteractionalexchangesinpreviousexcerpts.

Besidesincongruentrealizations,afrequentlyusedlinguistic

fea-turein Swedish is compound words. Thus, nominalization and

adjectivizationoftenoccurwithincompoundwords(e.g.

“rörelse-förmåga”or“movement-ability”).

Thewordstotheleft(Fig.8)aremostlyexpressedbythe

stu-dentsandthewordstotherightbytheteacher(adjectivization

andnominalization).Bothteacherandstudentsarealsoshunting

between the words to someextent. Thus, these language

fea-turesaremodelledinclassroomdiscoursealthoughnotexplicitly

acknowledgedasagrammaticalresourceformeaning-making.

4.4. Phase3

Inthethirdgroup-work(seeSection3.1),thestudentsimmerse

themselvesinoneanimalspecieseach,byreadingthetextbookand

searchingonInternet.Theywritedowntheirfindingsaccording

totheteacher’sspecificwritinginstructions.Intheseinstructions,

themovementbetweenvariousexpressionsalsobecomesvisible

(Fig.9).Theteacherhasplacedtheeveryday“translations”in

con-gruentformatwithinbrackets.Themoresubject-specificwordings

alterbetweencongruentandincongruentrealization.

Furthermore,thestudentsreceiveawritingframe,similartothe

instructions.Thereby,theyareatthisstagenotexpectedtoproduce

lengthy,structuredinformationreportsbutrathertofindandwrite

downdescriptionsundereachcaption.Thus,theframeisintended

tosupportthestudents’writing(students’textsnotanalyzedin

thispaper).However,thestudentsmostlyexplorethedisciplinary

discourseinthetextbookontheirown,althoughincollaborative

group-work.Thiswritingframemodelstosomeextentthetexttype

(classificationanddescription,combinedwithtemporalsequences,

Martin,2013).However,theteacherdoesnotexplicitlyreferto this.

Phase 3 is not completed by the end of the week (Section

3.1). However, to get some closure of this week’s work, the

teacherendswithashortcomparisonoftwoaspects:“nutrition”

and“reproduction.”Hewritesontheboard“eats–nutrition,”“get

children–reproduction.”Then,heasksthestudentstogive

exam-ples according to their species. Hence, these two abstract and

generalaspectsarehighlightedandrelatedtothemorespecific

contentthateachgrouphasbeenexploring,thusdisplayinga

sim-ilarwavingpatternasinotheranalysesinthispaper.

5. Conclusionandimplications

Thispaperhashighlightedhowthemovementtowards

disci-plinaryknowledgeanddiscourseineducationalcontextsmaybe

discernedandpromoted.Thegradualbuildingofknowledgeand

languageinthesecontextsmayinadditionbeconceptualizedas

awavingpatternorasarecurrentmovementbetweenandwithin

discourses(e.g.,Martin,2013;Maton,2013;NygårdLarsson,2011).

Thisissuggestedinthetheorizationsdescribedinthispaperand

maybesummarized bythevariables contextualdependencyand

condensationofmeaningaswellasfurtherconceptualizedbythe

metaphorssemanticwavesandteachingtowave(Macnaughtetal.,

2013;Martin,2013;Maton,2013).Thefindingsinthispaper

exem-plifythediscoursestrategiesofascienceteacherandcontributetoa

deeperunderstandingofcontentareateachers’discoursestrategies

whenseekingtopromotestudents’developmentofknowledge,

languageandliteracyandattemptingtobridgethe“semanticgaps”

(Maton,2013)betweenandwithindiscourses.

Research(e.g.,Hammond&Gibbons,2005)suggeststhe

bene-fitsofcarefulconsiderationonthechoicesofparticipantstructures

andtheuseofteacher-ledtalk.Thefindingsinthispaperdisplaya

recurrentinterplaybetweenmultimodalexplorativegroup-work

andlanguage-orientedwhole-classinteraction.Inthispaper,the

teacher–studentinteractionis visualizedanddescribed,and the

resultsdisplay a dynamic use ofsemiotic resourcesand reveal

howthediscourse,inwave-likepatterns,graduallymovestowards

dense expressions and between levels of concretization,

speci-fication, generalization,and abstraction.Grammatical metaphor

is a linguisticmeaning-making resource and crucial in literacy

development(Halliday,1998;Halliday&Martin,1993).The

find-ings display a movement between congruent and incongruent

realizationofmeaningandthevisualizationsofthewhole-class

interactionrevealamicro-wavingpattern.Consequently,thereisa

potentialforinteractionalscaffolding,whenitcomestomodelling

thesediscoursefeaturesandpromotingdisciplinarydiscourse.The

teacher uses the third move in theinteractional exchanges to

model,extendandexpandthediscourse(Hammond&Gibbons,

2005).However,evenmoreimportantly,theteacherforemostasks

openexplorativequestionsandcreatesaspacewherethestudents’

answersareappreciatedandbuiltupon.

Notallstudentsareorallyactiveinthewhole-classinteraction.

However,relativelymanystudentsare.Scienceisoftenconsidered

alienatingforstudents(e.g.,Lemke,1990;Olander,2013).When

itcomestostudents’participationandengagement,theteacher’s

contextualizedandexplorativestudent-activeapproach,aswellas

theaffirmationofthestudentsasco-constructersofknowledge,

maypromotestudentempowermentandastrongeracademic

lit-eracyengagement(Cummins,2014).Theteacherseekstoconstruct

thestudentsasknowledgeableandactivelyinvolvedinthe

explo-rativebuildingofknowledgeandlanguage.Thus,heattemptsto

constructthestudentsasscientists,providingaspaceforcuriosity,

wherethestudentsareencouragedtomakeproposalsand

legiti-mateclaimsofknowledge.Furthermore,accordingtotheteacher’s

ownreflexioninaninterview,hefeltthathewasabletoengage

manystudentsbythisapproach.

In other words, an analysis of the data suggests that the

teacherandthestudentsappeartojointlyapproachdisciplinary

waysofdoingandthinkingaswellasexpressingtheknowledge.

meaning-makingresources,allowingthemtoexpandtheir

knowl-edgeandsemioticresources.Thisapproachgoesbeyondafocus

onexperimentallab-workorlinguisticfeatures,perse.Instead,it

invitesthestudentsintoanexplorationofscientificdiscourseina

broadersense.

Theattemptoftheteacherinthepresentstudyisonlyemergent,

andthefindingssuggestseveralwaysfordevelopingamore

con-sciousapproach.Theteacherfocusesonsubject-specificwording

andmodelsthemovementsbetweeneverydayandsubject-specific

discourse.However,an explicitmeta-knowledgeabout features

suchasnominalizations maysupportboth theteacherand the

students inthe interpretationand production of densewritten

discourse(Fangetal.,2006;Gebhardetal.,2014).Therecurrent

movementsbetweenlevelsofconcretization,specification,

gener-alization,andabstractionmayalsobeacknowledged.

Theanalyticalmodelusedinthispaper,althoughnotdetailed

orpreciseineveryaspect,appearstocontributerelatively

effec-tivelytotheinterpretationandexplicitvisualizationofthedynamic

languageusage.It therefore also haspotentialto contributeto

teaching practice. That is, the visualization of teacher–student

interactionmaydeepenteachers’understandingofdisciplinary

dis-course.

Furthermore,theteacherhighlightsexplicitlythefield-aspect

taxonomy(Martin,2013)byfocusingclassificationasadisciplinary

activityin the whole-class interaction.This may bemore

con-sciouslyalignedwiththewrittendiscourseofthetextbook,which

inturnmayallowforthetechnicalityofthefield tobefurther

explored,therebystrengtheningthecondensationofmeaning.One

ofthemaingenresinschoolscienceisthe“informationreport”

(Martin,2013).Topayattentiontothisclassifyinganddescribing

texttypewouldbeinlinewiththecontent.Thus,theclassifying

activitiesandthewritingframeusedby theteachermayserve

asexplicitmodelsfor furtherinterpretationsoftaxonomiesand

activitysequencesandmoreextendedstudentwriting.

Addition-ally,anexplicitmultimodalapproachgivesopportunitiestodetect

thetaxonomicrelations suggestedintextbook(NygårdLarsson,

2011).

Moreover, further developments would be to acknowledge

student’smultilingualresourcesaswellascriticalliteracy

perspec-tives(García&Wei, 2014;Gebhardetal., 2014;Haneda,2014;

O’Hallaron,Palincsar&Schleppegrell,2015).

Theseapproachesinvolveprofessionaldevelopmentofcontent

areateachers whichis an essential concernin manycountries.

Thefindingsfromthisstudy,inlinewithotherstudies,illustrate

theimportanceofsuchadevelopment(e.g.,Hajer&Norén,2017;

Macnaughtetal.,2013;Rappa&Tang,2018).Knowledgeand

semi-otic resourcesare intertwined, and the buildingof disciplinary

discourseandliteracyrelyheavilyuponcontentareateachersand

theirabilitytoeffectivelysupportthestudents’inexpandingtheir

semioticresourceswhileexploringcomplexmeaningrelationsand

movingbetweenlevelsofconcretization,specification,

generaliza-tion,andabstraction.

Conflictsofinterest

None.

Acknowledgements

Thispaperrefersto datafromtheinterdisciplinaryresearch

project“ScienceandLiteracyTeaching”[grantnumber

721-2014-2015],fundedbytheSwedishResearchCouncil.Iwishtoexpress

mygratitudetomyresearchcolleaguesandtheteachersand

stu-dentswhocollaboratedinthisproject.

References

Bernstein,B.(2000).Pedagogy,symboliccontrolandidentity:Theory,research,critique. Oxford/Lanham:Rowman&LittlefieldPublishers.

Christie,F.,&Derewianka,B.(2008).Schooldiscourse.Learningtowriteacrossthe yearsofschooling.London:ContinuumDiscourseSeries.

Cummins,J.(1979).Cognitive/academiclanguageproficiency,linguistic interdepen-dence,theoptimalagequestionandsomeothermatters.WorkingPaperson Bilingualism,19,121–129.

Cummins,J.(1981).Theroleofprimarylanguagedevelopmentinpromoting edu-cationalsuccessforlanguageminoritystudents.InCaliforniaStateDepartment ofEducation(Ed.),Schoolingandlanguageminoritystudents:atheoretical frame-work(pp.3–49).LosAngeles,CA:Evaluation,DisseminationandAssessment Center,CaliforniaStateUniversity.

Cummins,J.(2000).Language,powerandpedagogy:Bilingualchildreninthecrossfire. Clevedon:MultilingualMatters.

Cummins,J.(2014).Beyondlanguage:Academiccommunicationandstudent suc-cess.LinguisticsandEducation,26,145–154.

Danielsson,K.(2016).Modesandmeaningintheclassroom–Theroleof differ-entsemioticresourcestoconveymeaninginscienceclassrooms.Linguisticsand Education,35,88–99.

Deen,J.,Hajer,M.,&Koole,T.(Eds.).(2008).Interactionintwomulticultural mathe-maticsclassrooms.Processesofinclusionandexclusion.Amsterdam:Aksant. Fang,Z.,Schleppegrell,M.,&Cox,B.(2006).Understandingthelanguagedemands

ofschooling:Nounsinacademicregisters.JournalofLiteracyResearch,38(3), 247–273.

García,O.,&Wei,L.(2014).Translanguaging:Language,bilingualismandeducation. Basingstoke:PalgraveMacmillan.

Gebhard,M.,Chen,I.,&Britton,L.(2014).“Miss,nominalizationisanominalization:” Englishlanguagelearners’useofSFLmetalanguageandtheirliteracypractices. LinguisticsandEducation,26,106–125.

Gibbons,P.(2006).BridgingdiscourseintheESLclassroom.London/NewYork: Con-tinuum.

Gibbons,P.(2009).Englishlearners,academicliteracy,andthinking:Learninginthe challengezone.Portsmouth,NH:Heinemann.

Hajer,M.,&Norén,E.(2017).Teachers’knowledgeaboutlanguageinmathematics professionaldevelopmentcourses:Fromanintendedcurriculumtoa curricu-luminaction.EurasiaJournalofMathematics,ScienceandTechnologyEducation, 13(7),4087–4114.

Halliday,M.A.K.(1998).Thingsandrelations.Regrammaticisingexperienceas technicalknowledge.InJ.R.Martin,&R.Veel(Eds.),Readingscience. Criti-calandfunctionalperspectivesondiscoursesofscience(pp.185–235).London: Routledge.

Halliday,M.A.K.,&Martin,J.R.(1993).Writingscience.Literacyanddiscursivepower. Pittsburgh:UniversityofPittsburghPress.

Halliday,M.A.K.,&Matthiessen,C.(2004).Anintroductiontofunctionalgrammar (3rded.).London:HodderArnold.

Hammond,J.,&Gibbons,P.(2005).Puttingscaffoldingtowork:Thecontributionof scaffoldinginarticulatingESLeducation.Prospect,20(1),6–30.

Haneda,M.(2014).Fromacademiclanguagetoacademiccommunication:Building onEnglishlearners’resources.LinguisticsandEducation,26,126–135. Jakobson,B.,&Axelsson,M.(2017).Buildingawebinscienceinstruction:Using

multipleresourcesinaSwedishmultilingualmiddleschoolclass.Languageand Education,31(6),479–494.

Kress,G.,&vanLeeuwen,T.(2006).Readingimages.InThegrammarofvisualdesign. London:Routledge.

Lemke,J.L.(1990).Talkingscience:Language,learning,andvalues.Connecticut:Ablex Publishing.

Macnaught,L.,Maton,K.,Martin,J.R.,&Matruglio,E.(2013).Jointly construct-ingsemanticwaves:Implicationsforteachertraining.LinguisticsandEducation, 24(1),50–63.

Mariani,L.(1997).Teachersupportandteacherchallengeinpromotinglearner autonomy.Perspectives:AJournalofTESOLItaly,23(2).Retrievedfromhttp:// www.learningpaths.org/papers/papersupport.htm

Martin,J.R.(2013).Embeddedliteracy:Knowledgeasmeaning.Linguisticsand Edu-cation,24(1),23–37.

Martin,J.R.(2017).Revisitingfield:Specializedknowledgeinsecondaryschool scienceandhumanitiesdiscourse.Onomázein,111–148.

Martin,J.R.,&Matruglio,E.(2013).Revisitingmode:Contextin/dependencyin ancienthistoryclassroomdiscourse.InG.Huang,D.Zhang,&X.Yang(Eds.), Studiesinfunctionallinguisticsanddiscourseanalysis(Vol.5)(pp.72–95).Beijing: HigherEducationPress.

Martin,J.R.,&Maton,K.(2017).Systemicfunctionallinguisticsand Legitima-tionCodeTheoryoneducation:Rethinkingfieldandknowledgestructure. Onomázein,12–45.

Maton,K.(2013).Makingsemanticwaves:Akeytocumulativeknowledge-building. LinguisticsandEducation,24(1),8–22.

Maton,K.(2014).Buildingpowerfulknowledge:Thesignificanceofsemanticwaves. InB.Barrett,&E.Rata(Eds.),Knowledgeandthefutureofthecurriculum(pp. 181–197).London:PalgraveMacmillan.

Maton,K.,&Doran,Y.J.(2017).Semanticdensity:Atranslationdeviceforrevealing complexityofknowledgepracticesindiscourse,part1-Wording.Onomázein, 46–76.

McKenney,S.,&Reeves,T.(2013).Conductingeducationaldesignresearch:What,why &how.London:Routledge.

Nygård Larsson,P.(2011).(Biologytexts: Text,languageandlearningina lin-guisticallyheterogeneousuppersecondaryclassroom)Biologiämnetstexter:Text, språkochlärandeienspråkligtheterogengymnasieklassDiss.Malmö:Malmö University.

NygårdLarsson,P.,&Jakobsson,A.(2017).Semantiskavågor–eleversdiskursiva rörlighetigruppsamtal[Semanticwaves–Students’discursivemobilityin groupdiscussions].Nordina,13(1),17–35.

O’Hallaron,C.,Palincsar,A.,&Schleppegrell,M.(2015).Readingscience:Using sys-temicfunctionallinguisticstosupportcriticallanguageawareness.Linguistics andEducation,32,55–67.

Olander,C.(2013).WhyamIlearningevolution?Pointerstowardsenactedscientific literacy.JournalofBiologicalEducation,47(3),175–181.

Rappa,N.,&Tang,K.S.(2018).Integratingdisciplinary-specificgenrestructurein discoursestrategiestosupportdisciplinaryliteracy.LinguisticsandEducation, 43,1–12.

Rose,D.,&Martin,J.R.(2012).Learningtowrite,readingtolearn:Genre,knowledge andpedagogyintheSydneyschool.Sheffield/Bristol:EquinoxPublishingLtd. Schleppegrell,M.J.(2016).Content-basedlanguageteachingwithfunctional

gram-marintheelementaryschool.LanguageTeaching,49(1),116–128. SwedishResearchCouncil.(2017).Godforskningssed.Vetenskapsrådet.

Unsworth,L.(2001).Teachingmultiliteraciesacrossthecurriculumchangingcontexts oftextandimageinclassroompractice.Buckingham:OpenUniversityPress. Vygotsky,L.(1986).Thoughtandlanguage.Cambridge:MITPress.