RACIAL PERFORMANCES ON SOCIAL MEDIA

A STUDY OF THE SWEET BROWN MEMESMEDIA AND COMMUNICATION STUDIES: MASTER'S THESIS

School of Arts & Communication K3 Malmö University

Spring 2019

Course codes KK649A & KK644B Simone Sevel-Sørensen

Master Thesis 2019

3rd Submission: October 21th Final submission: November 4th Supervisor: Temi Odumosu Examiner: Erin Cory

Date of grade: November 11th

Abstract:

Social Media has become a powerful tool in several aspects. It can mobilize movements, rallying for social or political causes, and it can bring people together to share experiences or interest on a global platform. Social media platforms have facilitated more dynamic ways of presenting and performing identity positions such as race, gender, class and sexuality. Though many scholars have agreed that the internet and social media offers interesting new aspects in relation to identity exploration and self-expression, the performance of identity online can also contribute to problematic discourses that reinforce old social stereotypes online affecting what happens offline. This thesis explores racial performance on social media by examining the phenomenon of ‘Digital Blackface’, which is a virtual continuation of a historical phenomenon that operates, in particular, through Internet memes. The thesis studies different versions of an American meme, which represent an altered representation of a real person, known as Sweet Brown. Sweet Brown is an African American woman who after she was interviewed on television became a viral celebrity. Due to her expressive personality, her image has been remixed into several popular Internet memes.

The theoretical framework consists of a theorization of racial performance and media representation theory. This theoretical lens is used in the analysis that sets out to answer the questions, how is the Sweet Brown meme used as a form of racial performance online? What is Digital Blackface and how does it operate online? And In what way can racial performance reinforce stereotypic representations?

The methodological approach the thesis employs to conduct the analysis and exemplify the problematics are visual analysis, critical discourse analysis and critical theory. Further, the implication of racial performances in Internet memes is linked to other recent cases or incidents that relates to issues of racial performance in the media.

Keywords: Racial Performance, Internet memes, Minstrelsy, Digital Blackface, Internet

Table of Contents

TABLE OF FIGURES ... 3

1. Introduction: ... 4

2. Research Purpose and Questions: ... 5

3. Thesis Structure ... 6

4. The Story of Sweet Brown ... 6

5. Background/Context and Literature Review: ... 8

5.1 Defining Race ... 8

5.2 Historical Context of Racial Performance and Blackface Minstrelsy ... 8

5.3 Race and Internet Cultures ... 13

5.4 Racial Performances Online ... 15

5.5 Internet Memes ... 16

6. Theoretical Framework ... 18

6.1 Theorizing Racial Performances: ... 18

6.2 Representation ... 21

7. Methodology and Data: ... 24

7.1 Empirical Data ... 25 7.2 Analytical Approach ... 26 7.2.1 CDA ... 26 7.2.2 Visual Method ... 27 7.2.3 Limitations ... 28 8. Ethical Considerations ... 29

9. Analysis and Observations ... 29

9.1 Sweet Brown Memes ... 30

9.2.1 YouTube Remix Videos ... 30

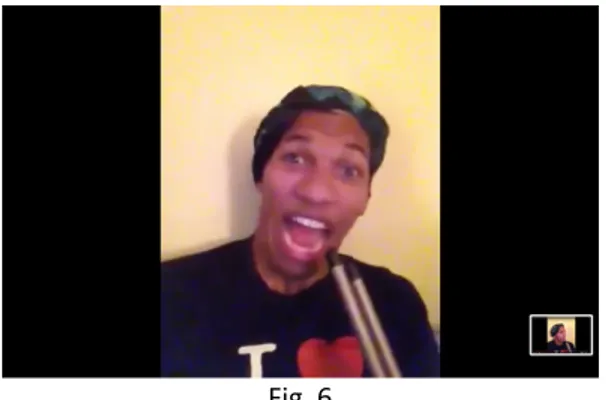

9.2.2 YouTube Reenactment Videos ... 31

9.2.3 Image Macros Memes ... 33

8.2.4 Level of Connotation and Interpretation ... 36

10. Discussion ... 39

11. Conclusion: ... 42

TABLE OF FIGURES

Fig. 1: Image p. 6 Fig. 2: Image p. 31 Fig. 3 Image p. 31 Fig. 4 Image p. 32 Fig. 5 Image p. 32 Fig. 6 Image p. 32 Fig. 7 Image p. 33 Fig. 8 Image p. 33 Fig. 9 Image p. 33 Fig. 10 Image p. 34 Fig. 11 Image p. 34 Fig. 12 Image p. 34 Fig. 13 Image p. 35 Fig. 14 Image p. 35 Fig. 15 Image p. 35 Fig. 16 Image p. 361. Introduction:

Social media is an incorporated part of society today, and undoubtedly it has brought many positive aspects along with it. However, as with all new technology it also brings problematic aspects and issues that can cause unpredicted consequences. An ongoing discussion in relation to social media, is about identity politics online. Many scholars continually contribute to this discussion. However, it seems to be a troublesome discussion. One of the difficulties within this discussion of identity politics is the issues of ethnicity and race online and complications of performed racial identity.

Racism and racial performances, as an execution of racism, is something that goes back a long time and as we have seen many examples on through history. Examples are Blackface minstrelsy, stereotypic representations in movies, theaters, and music videos etc. Blackface performances have constantly reappeared in new forms of media throughout the years.

Moving into the digital age of the internet, many speculated that the internet could be “a utopian place for identity play” (Nakamura, 2008;3), where race and gender could be eliminated, and discrimination on theses grounds therefore no longer exist. However, several scholars both within the field of media and communication studies, as well as other fields, have examined how racism and discrimination have moved along into the digital era and taken on new digital forms. Nakamura et al. explains “cyberspace has often been constructed as something that exist in binary opposition to “the real world,” but when it comes to questions of power, politics and structural relations, cyberspace is as real as it gets (…)In spite of popular utopian rhetoric to the contrary, we believe that race matters no less in cyberspace than in real life”

(Nakamura et al, 2000; 4). Their work articulates how social structures have a way of repeating themselves in new technologies.

The recent development within the digital era and popular online communication is the way people communicate on social media platforms. Where earlier modes of communication where text-based we now see a domination of visual communication consisting of image, animations and videos, spread on the social media platforms such as Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and Facebook. These platforms encourage visual communication in form of different photo editing tools, such as filters, ‘stickers’, images, icons etc., and by adding and altering these images, people ad layers of meaning to the message they are communicating, which eventually affect social discourse.

The term Digital Blackface has recently appeared in numerous articles and viral discussions. Digital blackface has been used to refer to the use of memes, GIFs, emojis and other digital visual material of black people, created and shared online, by white people (I elaborate the term further, later on in the thesis). Other recent episodes have raised concern about the problematic issues with online racial performance. One episode in 2018 was the Swedish influencer Emma Hallberg who was accused of Blackfishing on her Instagram profile. Balckfishing is a term used to describe people who are pretending to be black or mixed race on social media. Another incident from 2018 was the production of a fake Australian Black Lives Matter Facebook page, run exclusively by a white man who was profiting on sponsorships and donations for the black community.

These cases all links to a form of online racial performance however, this thesis seeks to specifically understand the term Digital Blackface, therefore the analysis will focus on Internet memes as a form of performative practice. The study will focus on the specific case of Sweet Brown and memes of her. Sweet Brown is an African American woman, also known as Kimberly Wilkins, who became a viral celebrity after she were interviewed on television. The Interview was uploaded to YouTube and following this, her image was remixed into several popular Internet memes, and widely spread on the internet. I will relate the concept of Digital Blackface to other forms of racial performances such as “Blackfishing” and “Catfishing” in order to address some of the different problematics of online racial performance and hereby contribute to the ongoing debate on identity politics in social media.

2. Research Purpose and Questions:

This study seeks to understand the phenomenon Digital Blackface, by situating it in a historical context, and engaging with the ongoing debate about identity politics on social media platforms. In particular it will explore how the use of internet memes of Black personalities complicates racial discourse, and potentially reinforces historical stereotypes; in this way arguing for the topic’s importance in the field of media and communication studies specifically. The thesis uses the case of the Sweet Brown and how this meme has been remixed and used online.

In order to address the topic of racial performance on social media in a focused way, the thesis will engage the following research questions:

- How is the Sweet Brown meme used as a form of racial performance online? - What is Digital Blackface and how does it operate?

- In what way does the Sweet Brown memes reinforce stereotypic representations?

3. Thesis Structure

To approach these questions, first, I will present some background information on the story of Sweet Brown. Then I will introduce the historical context and give an overview of blackface minstrelsy to ground the discussion of online racial performances. Next I will give an overview of previous research done in relation to internet culture and racial performance, with an emphasis on key concepts that can inform the further discussion. In addition, since this thesis focuses on Internet memes and discusses racial performances in this context, I will also discuss memes and give a definition of the term. Following chapters will present the theoretical framework that is applied in this thesis, which is theorization of racial performances and media representation theory. Then the methodological approach and research design, as well as the empirical data and ethical considerations, will be presented. The final chapters will present the analysis of the empirical data followed by a concluding discussion that will present the observations of this study.

4. The Story of Sweet Brown

To give an understanding of the Sweet Brown case and the memes I discuss in this these, I will initially present the circumstances and story behind how Kimberly Wilkens, better known as Sweet Brown (Fig 1), turned into a numerous of different remixed Internet memes and became an online artefact that have spread all over the Internet’s social media platforms.

Sweet Brown Micro Image Meme

Sweet Brown is a pseudonym used by the woman Kimberly Wilkens, a black Oklahoma resident who overnight became a viral celebrity after she appeared in a TV interview. It was the local news station KFOR News Channel 4 who had interviewed the Oklahoma City resident after she had been evacuated from her apartment building that was set on fire the morning of April 7th, 2012. Wilkens testimony of the incident in the interview led

to an extreme exposure online and this was what brought her to fame. Wilkens interview and expressive description of the incident is quoted below;

“Well I woke up to get me a cold pop. And the I thought somebody was barbequing. I said oh lord Jesus it’s a fire. Then I ran out, I didn’t grab no shoes or nothin’ Jesus! I ran for my life! And then the smoke got me. I got bronchitis. Ain’t nobody got time fuh that!”

(See original interview; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j2EEZKVCZ4E ).

The last line “Ain’t nobody got time for that!”, instantly became a catch phrase used in everyday context and as common humoristic comment on social media, several of the lines from the interview are remembered and have been used as statements and punch lines, in different online content such as Memes, remixed videos and impersonations of Sweet Brown.

The original interview of Wilkens was uploaded to YouTube by KFOR employee Ted Malave the same day as the interview, however another version was uploaded April 9th,

2012 by a white YouTuber called luscasmarr, this version has since become the most shared version to date with over 1 million views and over 109.000 Facebook shares within only 48 hours.1 Following this, several sites uploaded and reposted the interview

with Sweet Brown, and the video received extreme public attention.

It is interesting to consider the original interview and how Wilkens was portrayed by the TV station. KFOR’s converge of the fire incident payed most attention and time to Wilkens’s testimony of the episode, giving little space to further details about the episode and damage to the building which had left the residents without power and depending on help from the red cross, nor was there given much attention to the woman in wheelchair who was brought to the hospital to be treated for smoke inhalation. Considering the fact that Wilkens became an online celebrity, the sensation in this, somehow shallow media story, was the persona Wilkens or Sweet Brown as she presents herself and is perceived by many. One could speculate that KFOR brought the story, not because of the news value of the story but because they knew that Wilkens expressive testimony and persona would attract and entertain their viewers.

Following the upload of the interview to YouTube, Wilkens image started circulating online in an abundance of humorous remixed video versions of the interview, various memes, twitter accounts, and impersonation videos on YouTube with people performing ‘Sweet Brown’.

Moreover, Wilkens herself suddenly appeared as a public figure, as guest in TV shows, and different interviews. She was also used in a number of commercials where she recited her famous lines from the original interview, one being a dentist commercial where she appears as having tooth pains, to what she states “Ain’t nobody got time for that” (See commercial (https://www.memecenter.com/fun/1113876/sweet-brown-got-a-toothache). The Boston radio station WAAF released a ringtone featuring Wilkens catchphrase from the interview. A remixed audio version of her interview on KFOR, “I

Got Bronchitis”, was released for purchase on Apple iTunes store in April 2012, Wilkens however, filled a copyright lawsuit and complaints against this unauthorized use for commercial purpose, the song has therefore since been removed from the iTunes store. Wilkens herself, also made used of her own catch phrases when launching a BBQ sauce called, “Sweet Brown – Oh lord it’s a fire” and a small clothing line with prints of her and her famous lines.

5. Background/Context and Literature Review:

This study is founded in an interest in the phenomenon Digital Blackface and how it operates online. This chapter will present the historical background for this topic and discuss previous literature that present key concepts and background information that can enlighten the understanding and further discussion of this chosen topic.

5.1 Defining Race

As race is central to this thesis, I will briefly define my understanding of the concept. In this thesis I am working with the definition of race as being a social construction. According to Omi and Winant (1994), people interpret the meaning of race by framing it in social structures, and that conversely, recognizing the racial dimensions in social structures leads to interpretations of race. They state that race have no fixed meaning but is constructed and transformed socio-historically (Omi & Winant, 1994; 71). Further I find Grada Kilomba’s (2018) definition of everyday racism helpful in relation to my topic. “Everyday racism refers to all vocabulary, discourses, images, gestures, actions and gaze that place the Black subject and People of Color not only as ‘Other’ -the difference against which -the white subject is measured -but also as O-therness, that is the personification of the aspects the white society has repressed” (Kilomba, 2018; 43-44). I will use the following sections to explore in more detail how race and racism enters structures, such as technology, representation and discourse.

5.2 Historical Context of Racial Performance and Blackface Minstrelsy

Racial performances are often connected to the 19th century minstrel show, and closely

linked to American culture where it has a long and complicated history. However, these shows did not invent blackface impersonations (Vaughan, 2005;2). The performance practice of ‘blacking up’ existed in the middle ages were it in religious plays was a simple way of distinguishing good from evil (ibid). Later in the 16th century shift to modernity,

these religious identifications were replaced with “racially defined discourses of human identity and personhood” (Goldberg,1993;24 in Vaghuan;2005;2) which was displayed in form of blackface performances on the English stages (Vaughan, 2005;2). As Vaughan explains “Blackface had become more than a simple analogy – blackface equals damnation - and taken on multiple meanings, participating in several readily recognized codes at once” (…)”Blackface functioned as a polyphonic signifier that reflected changing social contexts and helped to create expectations and attitudes about black

people” (ibid). Though blackface has been used as a mode of performance for centuries, Vaughan (2005) stresses that there is quite a difference between Blackface as an old theatrical practice as it was used on English stages until the 19th century when Othello

was performed, and Blackface known from the 19th century minstrel shows. Where the

16th century blackface performers intended to give a convincing representation, the 19th

century minstrel show used make-up that exaggerated lip and eye features and presented “grotesque images of black people for comic farce” (Vaghuan,2005;9). Professor Eric Lott describes this theatrical practice of blackface minstrelsy in his book Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and The American Working-Class (1995): “Blackface minstrelsy was an established nineteenth century theatrical practice developed in America where white men caricatured blacks for sport and profit” (…) “Minstrelsy was arranged around the “borrowing” of black cultural materials for white disseminations, a borrowing that ultimately depend on the material relations of slavery, the minstrelsy obscured theses relation by pretending that slavery was amusing, right, and natural” (Lott,1995;3). Lott express that the minstrelsy was a popular culture form that drew on an” enduring narrative of racist ideologies” (Lott, 1995; 17).

The premises of which blackface minstrelsy is remembered, is its portrayal of African American life and culture through masquerade. The nineteenth century blackface performers wore blackface make-up and costumes and depicted a range of stereotypic characters and scenarios that relied upon ridicule and racist caricatures and representations of the slave and plantation life of African American people (Lott, 1995). The entertainment form drew on elements such as music, dance, folklore, jokes, skits and mock oratory, satire, impersonations, and racial and gender cross-dressing. Language use was one mode to perform blackness; “the minstrel’s dialect, whatever its relationship to true Negro Speech, was coarse, clumsy, ignorant and stood at the opposite pole from the soft tones and grace of what was considered cultivated speech” (Nathan Huggins in William Mahar, 1985;263).

Vaughan suggest that performers blackened they face in order to play particular roles, she highlights conventions and patterns like character types, plot situations, tropes and other performative tactics – that is repeated from play to play, that highlighted the way black characters were performed and read. Vaughan explains how the purpose of blackened figures have been to “disguise and distinguished the identity of the performer … from his or her everyday identity within the community” (Vaughan, 2005;19) and that this form of racial disguise function as a costume “in order to facilitate instant character recognition” (Clark and Sponsler,1999;71, Vaughan, 2005;19). However, she points out the complications with using blackness as a costume/disguise “Because blackness itself is an overdetermined symbol, the character who disguises himself as black brings into the play all various meanings that blackness conveys” (Barthelemy, 1987;144, Vaughan, 2005;108).

In contrary to common views on minstrelsy, Lott demonstrates the historical contradictions and the social conflicts the minstrel show opened up in the years before the Civil War (Lott, 1995;8). According to Lott, critics of minstrelsy has to often dismissed working-class racial feeling as uncomplicated and monolithic (p.4). Lott suggest a more complex nature of the functions of minstrel shows and that the audiences involved “were not universally derisive of African Americans or their culture, and that there was a range of responses to the minstrel show which points to an instability or contradiction in the form itself” (Lott, 1995;15). Lott argues that racism was not the sole motive of these performances; “in blackface minstrelsy’s audiences there were in fact contradictory racial impulses at work, impulses based in the everyday lives and racial negotiations of the minstrel show’s working-class partisans” (ibid;4).

The complexity of the minstrelsy performance is also pointed out by Mahar (1985); “while some early blackface comedy undoubtedly caricatured blacks, much of it was directed toward white values or behaviors (Mahar, 1985; 281). Like Lott, Mahar states that certainly the minstrelsy show complicated racial relationships, but it was more than a racially orientated form of entertainment. “It satisfied needs that were far more complex than the mere gratifications of white audience’s desire for cultural or racial superiority” (Mahar, 1985; 285). Mahar adds that the different dialects that were used in minstrelsy performances at times functioned as a satirical weapon (1985;263). Originally blackface minstrel shows were performed by white European descendants in North American cities, from where it gained popularity and broader appeal and cultural influence, but blackface also became a mode of performance for Black entertainers. Robert C. Toll (1978) explains how Black performers after the Civil War entered the show business as minstrels, and the way they did this, have created long lasting patterns for Black entertainers. In order to win over white audiences, Black performers displayed themselves and claimed to be “ordinary ex-slaves doing what came naturally, rather than skilled entertainers acting out white-created stereotypes of blacks” (Toll,1978). For Black entertainers, minstrelsy was a way into show-business and though the salary was not high, they still earned more than they had before (ibid).

The audience of minstrel shows was made up mainly by working class white males however, after 1830s where theater prices dropped, the audiences was more mixed with people from other classes as well. “The minstrel show (…) began actually to signify (…) a class defined, often class-conscious, cultural sphere” (Lott, 1995;67). As Lott notes, “one of minstrelsy’s functions was to bring various class fractions into contact with one another, to mediate their relations, and finally to aid in the construction of class identities over the bodies of black people” (Lott, 1995;67). Lott suggest that, blackface in a partial sense figured class and its language of race provided displaced representations of “working classness” and it was implied that “caricatures of blacks

culturally represented workers above all, Blackface quickly became a sort of useful shorthand in referring to working men (Lott,1995:68).

“… these new amusements were also primary sites of antebellum “racial” production, inventing or at least maintaining the working-class languages of race that appear to have been crucial to the self-understanding of the popular classes, and to others’ understanding of them as well. In minstrel acts and other forms of “black” representation, racial imagery was typically used to soothe class fears through derision of black people, but it also became a kind of metonym for class” (Lott, 1995;72).

Lott (1995) also present gender cross-dressing as a central element in minstrel shows. Female characters were performed by male minstrels, in a time where woman otherwise regularly appeared on the legitimate stage and many of times women were the target of these humorous disguises of blackface (p.26). As Lott states “the black mask offered a way to play with collective fears” (p.25) – according to Lott, white men’s fear of female power was dramatized through a ‘draconian and grotesque’ representation of female figures in the minstrel shows (p.27). Typical female portrays was either the wench or the jockey blazon but another female character that emerged and was nurtured in the minstrel show was the mammy figure, who was present in many of the minstrel songs. McElya (2007) explains in the book “Clinging to mammy, the faithful slave in twentieth century America”, how the mammy was a narrative of the faithful slave and plantation fantasies and that this myth lingers “because so many white Americans have wished to live in a world in which African Americans are not angry over past and present injustices, a world in which white people were and are not complicit, in which the injustices themselves – of slavery, Jim Crow, and ongoing structural racism - seem not to exist at all”(p.3). The mammy figure responded to these wishes. The mammy caricature was mostly portrayed as an obese black woman, dressed in apron and scarf tied around her head, often portrayed as old or middle-aged – as an attempted to desexualize her. She had a hearty laugher and a big smile, taking care of domestic chores, providing and happily serving her white family. This portrayal was supposed to be evidence of the humanity of enslaved life. In American Culture, the mammy caricature has been used to soften the discourse and memory of slavery, but as McElay (2007) points out, the representations and use of the Mammy caricature, as they have been described by whites, have little resemblance with the actual life of black enslaved women. The mammy caricature implied meanings such as black women only were fit to domestic labor, and consequently this stereotype became a rationalization of economic discrimination of black women. This is an example of the enduring impact the mammy caricature has had on the lives of black women in American society (McElay, 2007).

Lott notes that “the minstrel show was so central to the lives of the North Americans that we are hardly aware of its extraordinarily influence” (1995;4). Though blackface minstrelsy has a strong connection to American culture and history, it is also a known phenomenon in European regions and colonial locations. As today, the Netherlands upholds their own blackface performance traditions known as ‘Zwarte Piet’ or Black Pete. This tradition is thought to be an innocent and pleasant children’s festivity, where people portray Black Pete by putting on blackface, the festivity ends in a merry evening where presents are given to the children, however since the 1970s this tradition have been critiqued mainly by black people (Wekker,2016;28). Also, Britain embraced the blackface minstrelsy during the nineteenth century, and it was visible within popular culture until 1978 with the variety entertainment program, ‘The Black and White Minstrel Show’ broadcasted by BBC. This illustrates that Blackface minstrelsy was not only linked to an American context but have also had a significant influence outside America.

Today the blackface minstrel show is often regarded as a force of racist hegemony, in a society build on salve labor, and though the nineteenth century stage form of minstrel show is no longer a general concern in American culture, its ability to awake feelings of racism, marginalization and exploration remains.

As Lott demonstrates blackface minstrelsy has had a significant influence, understanding this influence can help us understand how race affect lives also in our time and culture, and therefore he stresses the need for paying attention to minstrelsy studies. In relation to this, a number of scholars have proposed the continuing significance of blackface minstrelsy in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, although in fields and contexts removed from those of the original stage form.

Scholars have observed that minstrelsy practice can be seen in the cultural texts and practices of the late twenty and twenty first centuries and therefore minstrelsy has been utilized as a lens to look at the practices of contemporary cultures and observe the legacy of blackface minstrelsy. Examples of minstrel perspective can be seen in the work of Joshua L. Green in Digital Blackface: The Repacking of the Black Masculine Image (2016); and in Andrew Sargent’s, How to Get Away with Blackface: Performances of Black Masculinity in ‘Tropic Thunder’ (2017).

Stephen Johnson (2012) describes the cumulative form of blackface minstrelsy as “it builds up in layers over time, adding racial meaning to the accepted imagery without entirely erasing the old, haphazardly accumulating ways of reading blackface that reshape, refocus, and redirect its intentions’ (2012;3).

Stephen Johnson considers the concept of blackface minstrelsy as constantly changing and therefore impossibly to define. Johnson (2012) propose that there is not only a trace, but a noticeable “resurgence of blackface in contemporary society” (2012;2), he explains this renaissance of blackface with the significant change the internet have

brought and how that may be partly responsible for this development “as with the Internet everything has become available to everyone” (Johnson, 2012;3)

This section has provided an understanding of blackface minstrelsy as a cultural phenomenon and its historical impact and will serve as background information in the analysis to point to its continuing impact in society and internet culture today. As a conclusion on this section, the blackface mask has had various functions. It was used to negotiated self-perceptions and identify oneself in relation to the ‘other’, but also to address collective fears. Not only race was negotiated through the black mask, also markers as class and gender was negotiated through blackness.

5.3 Race and Internet Cultures

To place the topic of racial performance and (Digital) blackface within the field of media and communication studies, this section will discuss, and present existing research done in relation to racial issues online to provide background information on the role of race in modern internet culture.

Despite early utopian ideals about the Internet as a space where racial inequalities and racism could be eliminated, social media has simply amplified prejudices in society. A number of researchers have pointed out, that the Internet is a place where race “happens” and that race matters no less in cyberspace than in real life (Kolko et al, 2000). Scholars have proposed that the Internet offers the possibility to challenge traditional definitions of identity, since its ever-expanding technical possibilities allow for alternative ways to create and play with more fluid definitions of identity, however some scholars also address the more problematic issues with Identity online, hereunder race. Scholars gather around two constricting perspectives in relation to online identity representations. As Punday (2000) presents, either the Internet is considered to be a possibility for progressive change or as the source of crude and simplistic stereotypical representations.

Boyed and Ellison (2008) states that social networking sites allow users to construct online representations of themselves, users decide what to show and what not to show. Therefore, it is important to examine how internet users display identity, hereunder racial identity, on social networks, as it gives researchers the opportunity to look into how Internet users convey identity, and in particular racial identity.

The nature of cyberspace as Nakamura et al. explains, “allows people to log in and shrug of a lifetime of experiencing the world from specific identity-related perspectives. You may be able to go online and not have anyone know your race or gender – you may be able to take cyberspace’s potential for anonymity a step further and masquerade as a race or gender that doesn’t reflect the real, offline you – but neither the invisibility or the mutability of online identity make it possible for you to escape you “real world“ identity completely” (Kolko et al, 2000;4), according to Nakamura race matters in

cyberspace because “all of us who spend time online are already shaped by the ways in which race matters offline, and we can’t help to bring our knowledge, experiences, and values with us when we log on” (2000;5).

Lisa Nakamura have done serval studies on online identity and race in cyberspace. In the book Cybertypes: Race, Ethnicity and Identity on the Internet (2002) Nakamura looks into race and identity online, investigating “what have happened to race when it went online, and how our ideas about race, ethnicity, and identity continue to be shaped and reshaped every time we go online” (Nakamura, 2002;12). According to Nakamura, images of race and racialism proliferate in cyberspace and along with scholars recognizing this, there is now a going concern with how race is represented in cyberspace - ”for the internet is above all a discursive and rhetorical space, a place where “race” is created as an effect of the Net’s distinctive uses of language” (Nakamura, 2002; 14). Nakamura argues for the importance to examine the variety of communication situations online, to trace how these communications display and creates what she calls “cybertypes” or images of racial identities (Nakamura, 2002). She also notes that this calls for multiple approaches and examples, since cyberspace offers are numerous kinds of narratives.

Daniel Punday states, as he refers to Nakamura et al recent critics, that “quite contrary to the early belief that cyberspace offers a way to escape gender, race and class as conditions of social interaction (…) online discourses is woven of stereotypical cultural narratives that reinstall precisely those conditions (Punday, 2000; 199, Nakamura, 2002;14). Punday adds that recent scholarships discuss “whether participants in online discourses are constructing coherent identities that shed light on the real world or whether they are merely tacking together an identity from media sources” (Punday, 2000;204, Nakamura, 2002). Also, Cisneros and Nakayama (2015), notice that the Internet, as it allows for anonymity, is a place where racist remarks can thrive.

Research has showed that images plays an essential role in understanding the changing interactions and evolutions of online identity politics. In a study by Brown (2012) she looks into how reaction GIFs are used on the platform Tumblr, to communicate reactions and emotions, and thereby contribute to the construction of an online multifaceted identity. Brown argue that the “semi-anonymity of the internet facilitates an assumption of whiteness”(2012;42) according to Brown “the diversified identities mined for these GIFs are used - as a practice that acknowledges that ‘Others’ exist online and can and should be visible instead of completing the façade of online colorblindness” (2012;41), however, Brown points out the problematics with this practice referring to what Nakamura noted, that since the Internet reflect real-world bodies it also reflects the racist attitudes they inhabit (2012;42). Browns conclusion on her case study, is that GIFs preform complex roles online and cannot be oversimplified as just something ‘fun’ or ‘silly’ to share online, she argues that restraints should be employed when distributing images portraying the ‘other’ (2012;43).

5.4 Racial Performances Online

The discourse of racial performance is concerned with role-playing and identification between different subject positions over time; and is a way to critically explore the power structures influencing who speak, acts, wields agency, and in what location (Diamond,2006;4). Citing the important work of Joseph Roach, Diane Paulin explains that such performances are also about “substitution in representations – white bodies standing in for black ones, romantic relationships standing in for social conflicts or even the past standing in for the present – that trouble the identities and subjects they depict as well as those indirectly invoked” (Paulin, 1997;418). Joseph Roach understands substitutions as key to theorizing performance in post-slavery (or what he calls ‘Circum-Atlantic’) societies, which “have invented themselves by performing their pasts in the presence of others” (Roach, 1996; 5). He continues; “They could not perform themselves, however, unless they also performed what and who they thought they were not. By defining themselves in opposition to others, they produced mutual representations from encomiums to caricatures, sometimes in each other’s presence, at times behind each other’s backs (Ibid.). These performances take on further dimensions when engaging identity politics online.

As Nakamura points out with a quote “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog” (Nakamura, 2001;1) also meaning on the Internet you get to perform your identity. You can hide you real life identity, masquerade, impersonate or take on fake identities. Nakamura have in several of her works explored the concept of ‘identity tourism’ and how the internet offers the possibility to try on other ethnicities. Nakamura explains how users perform stereotype versions of the “Oriental” that perpetuate old mythologies about racial difference (Nakamura, 2002;16). The online preperformances is facilitated by features on the social media platforms such as filters, stickers, images and other effects that can disguise or modify you real life identity.

Another term that has been used in relation to racial performance practice online and especially stereotypic representations, is Digital Blackface. The awareness of “Digital blackface” was brought to public attention in an article by Teen Vouge, “We Need to Talk About Digital Blackface in Reaction GIFs” from to 2017 “, followed by a video by BBC “Is it OK to use black emojis and GIFs?”, and latest an article in the Guardian “Why are memes of black people reacting so popular online?” all describes the phenomenon “Digital Blackface”. The term refers to the practice of the nineteenth century blackface minstrel show, and its practice of performing racist African-American stereotypes, the digital version of this phenomenon has more specific been defined as the practice when white people produce, post or circulate visual images or material, of black people or black culture, to express humorous reactions or emotions on social media platforms. This is seen as a behavior that draws on the racist discourse of blackface minstrelsy, and the practice of black people being objectified for white people’s amusement. The term

Digital Blackface has rarely been referred to by scholars however, the term has been used by Joshua Lumpkin Green (2006) and journalist Adam Clayton Powell lll (1999) who refers to a similar version of the term, what he calls; “High- tech blackface”, which he uses to describe harmful racial stereotypes in video games.

This thesis focuses on the phenomenon Digital Blackface and how this can be considered one of the latest iterations of the 19th century blackface minstrel show, however other

terms have been used in relation to racial performances online which I consider relevant to mention as it emphasizes the importance of discussing racial performance and identity politics online.

In a study by Smith, Smith and Blazka (2017) they explore the concept of catfishing and online impersonation, by examining previous incidents of athletes that have been catfished or have acted as a catfish, through the use of a fake social media profiles. What Smith et al, seeks to cast light on is the legal and ethical issues with fake social media profiles. They suggest laws that could have ramifications on catfishing and fake online personas however they also address that the motives behind fake online personas can vary a lot, from being solely for the purpose of entertainment and humor to those of a more serious character, being harmful and deceptive. They therefore call for the need for a distinction between catfishing and simply impersonating someone online. A recent case in Australia links the phenomenon of catfishing to online racial performance. Ian Mckay, a white Australian man created a fake BlackLivesMatter Facebook page, and by giving people the assumption that he was black, he tricked people to give economic support. Another example of online racial performance is seen in the case with the Swedish influencer Emma Hallberg who was accused for blackfishing on her Instagram profile. Blackfishing is a recently formulated term that has been used to describe racial performances on social media where a person, who identifies or is racialized as white, is accused of pretending to be black or “pass” as black by using makeup, hair products and in some case even surgery to change their physical appearance. The term was coined following a Twitter thread calling on people to post “all of the white girls cosplaying as black woman on Instagram”. Blackfishing online, specifically describes the act of picking physical attributes that are seen as being associated with black women and capitalizing on these through body enhancement, to get lucrative sponsorship deals, in place of women of color. In these terms Blackfishing links to catfishing.

This trend has been criticized for being a form of cultural appropriation without accountability. These examples of identity masquerade through Digital Blackface, catfishing and Blackfishing exemplify some of the problematic issues with online racial identification.

5.5 Internet Memes

As this study focuses on racial performances through internet memes I will in this section define my understanding of memes and discuss relevant literature.

When scouting the internet and social media platforms one notice that much content is image-based. The so-called meme is an image phenomenon that has gained popularity and is frequently shared among Internet users.

The word meme originates from the biologist Richard Dawkins book from 1976, The Selfish Gene, wherein Dawkins coined the term explaining the concept ‘meme’ as “a unit of culture that’s spread like biological genes”. Dawkins explained the mechanics of evolution and how genes, in human, plants and animals, replicate and make copies of themselves in order to evolve and better their chances for survival, “over time genes adapt and join with others to help replicate” (Dawkins, 1976, in Maurp, 2019;10). Dawkins compares natures evolution with cultural evolution and how human culture evolves over time in a similar way. In biology, genes try to replicate them self by imitation, Dawkins transfer this notion to cultural evolution and propose the replicator that passes on cultural ideas can be defined as “a unit of cultural transmission, or a unit of imitation” (Ibid). The word ‘imitation’ comes from the Greek word mimeme which Dawkins shortens to “meme”, which also resembles même from the French word for memory (Ibid). According to Dawkins a meme transmits from brain to brain through the process of imitation and allows cultural replication and evolution. Based on Dawkins concept the traditional definition of “meme” indicates units of cultural transmission that “diffuse from person to person, but shape and reflect general social mindsets” (Shiftman, 2014;4 in Yoon, 2016; 95)

Within Internet culture, several scholars have tried to pin down, understand and define “memes”. The current definition of internet memes is associated with user-generated online contents as e.g. image macros, videos, GIFs etc. This paper uses meme as a general term, in the analyses more specific terms will be used when relevant. The definition of internet memes offered by Shiftman states that memes are (a) a group of digital items sharing common characteristics in content, form, and/or stance, which (b) were created with awareness of each other, and (c) were circulated, imitated, and /or transformed via the internet by many users (Shiftman, 2014;41, Yoon, 2016;95). Shiftman ads that internet memes are “cultural information that pass along from person to person, but gradually scale into a shared social phenomenon” (Shiftman, 2014;18, Yoon 2016;95). Shiftman outlines how memes repack themselves in order to reproduce, here he mentions strategies as mimicry and remix. Mimicry involves recreating a specific text by different people, remixing is a strategy that refers to technology-based manipulation such as photoshopping or adding sound to an image.

Yoon (2016) have studied Internet memes with the aim to understand how they deal with racism. She draws on Shiftman and links Internet memes with Internet humor. Not all memes are humorous or intended as jokes however, Knobel & Lankshear (2006, Yoon, 2016) points out that humor and joke is a key component in many memes. The internet has changed the way people communicate and memes further have contributed to a further change. It is what author Cole Stryker calls the “language of

memes” a “visual vernacular” that offers people a quick way of communicating emotions and opinions (Muarp,2019;28). However, the language of memes can also contain a problematic discourse, as An Xiao Mina (2019) explains memes can be silly, memes can be harmless, they can be destructive, and they can be serious, they can be several of these things at once, however it is not always that memes are harmless. The “silly” stuff that meme culture often consist of is fundamentally intertwined with how we find and affirm one another, direct attention to human rights and social justice issues, build narratives, and make culture (Xioa Mina, 2016).

Shiftman (2013) explains, that it can be difficult to examine and study memes

empirically, however they offer an exceptional and powerful method for increasing our understanding of digital culture, since “memes diffuse at the micro level but shape the macro level of society” (Shiftman, 2013;372).

6. Theoretical Framework

Where the previous chapter has provided background information and context for this study, this chapter serves to provide a theoretical framework. The chosen theories will be used to analyse, interpret and discuss the empirical data.

In search for theory for my study I found performance theory to be a relevant and useful framework to apply, as the thesis focuses on online racial performances. I will therefore theorize racial performances and draw on knowledge and understandings from scholars regarding this topic. Furthermore, I will employ representation theory as my research seeks to answer how stereotypes get reinforced through racial performances and representations in Internet memes.

6.1 Theorizing Racial Performances:

The term Performance is often understood as a theatrical practice; however, the field of performance studies has evolved into an interdisciplinary field that defines and understand the term in a broad sense and uses the lens to study and understand the world. Performance studies and theory is associated with the work of Victor Turner (1988) and Richard Schechner (1985). Their attention was on the performative nature of the world, and how everyday life was governed by codes of performance, they see performance as a central element of social and cultural life, including everything from performative art such as theater and dance, but also religious rituals, public speaking, practices of everyday life, sports, play, popular entertainments and nonverbal communication etc., they consider everything that express social behavior, as a performance.

This study is specifically interested in examining racial performances in an online context. The following presents different scholars that addresses issues that are related to my examination of racial performance.

Elin Diamond states that “performance is always a doing and a thing done …. Every performance if it is intelligible as such, embeds features of previous performances; gender conventions, racial histories, aesthetic traditions – political and cultural pressures that are consciously and unconsciously acknowledged” (1996;1). Diamond consider performance as a cultural practice that reinvent ideas and symbols of social life, and states that such reinventions are evidently negotiations with regimes of power (Diamond, 1996;2). Diamond argues that by viewing performance within a complex matrix of power one can obtain an understanding of history and change or as she expresses it by quoting Joseph Roach “the “present” is how we nominate (and disguise) “the continuous reenactments of a deep cultural performance”. Performances “(…) can expose fissures, ruptures and revisions that have settled into continuous reenactments” (ibid). “To study performance is not to focus on completed forms, but to become aware of performance as itself a contested space, where meanings and desires are generated, occluded, and of course multiply interpreted” (Diamond, 1996;4).

As presented earlier on Joseph Roach concept of substitution, or as referred to by Diana Paulin surrogacy, is particular useful in this study. The performative process of surrogation is described by Roach as a process in which “culture reproduces and recreates itself” (Paulin, 1997;1). Paulin’s use of the concept differs from Roach, as she focusses more on the process of substitution, where Roach’s focus is on memory. Paulin draw on this concept to examine how 19th century representations recall the

conflicts and unresolved history of black and white relations in America (ibid). I find this concept useful in relation to my study of representations in Internet memes and how they can be considered as troublesome performance of race.

In his article Performing Ethnicity (2015) John Clammer argues for the use of performance theory to inform the thinking of race and ethnicity. Clammer argues for the usefulness of performance studies and theory to analyse how ethnicity itself is ‘performed’ and get expressed through various behaviors, cultural activities and forms of bodily presentation and to the ways in which such identities are in fact dynamic, situational, historical varied and often very unstable, “Performance studies and theory is a mean of identifying human action patterns that contribute to self-presentation, identity formation and the embodiment of collective memory (or ‘culture’) in sets of practices that express particular ways of being in the world. Performance is essentially the creation, presentation or affirmation of an identity (real or assumed) through action” (Clammer, 2015;2160). Clammer refers to Richard Schechner and his concept of ‘restored behavior’ as being a central aspect of the theory. According to Schechner (2013) “restored behavior is the key process of every kind of performing, in everyday life, in healing, in ritual, in play, and in arts. Restored behavior is “out there” separate from “me”. To put in personal terms, restored behavior is me behaving as if I were someone “else”, or “as I am told to do “or “as I have learned”. Even if I feel myself wholly

to be myself, acting independently, only a little investigating reveal that the units of behavior that comprise “me” were not invented by me”. (Schechner 2013; 34, in Clammer, 2015; 2161).

Nadine Ehlers argues for the use of performance theory and performativity in relation to race and how individuals are formed as racial subjects, in her book Racial Imperatives (2012). Based on Foucault’s concept of discipline, Ehlers argues that race is a form of disciplinary practice that produces subjects as raced. According to Foucault discipline is a particular form of power, he understands discipline as “a set of practices and techniques that ‘makes’ individuals; discipline is the specific technique of a power that regards individuals as both objects and instruments of its exercise” (Foucault, 1991;170; Ehlers,2012; 4). Ehlers establish an understanding of race as a disciplinary practice that molds and modifies identity through targeting the body. Based on the notion that race is a disciplinary practice, Ehlers states that race is therefore also performative and that the mechanism through which the disciplinary formations is installed and sustained is racial performativity. Drawing on the work of Judith Butler and her theory of performativity, Ehlers state that “race is performative because it is an act - or, more precisely a series of repeated acts - that brings into being what it names” (Ehlers, 2012; 6). Race, rather than being genetically inscribed, are discursive constructs that produces certain kinds of bodies and subjectivities (Ehlers,2012;7). Repeated stylizations of the body or sets of repeated acts within a highly regulatory frame, produces over time the appearance of what Butler calls “a natural sort of being” (Butler,1999;25, Ehlers,2012;7). Ehlers theory of race performativity states that subjects are regularly categorized through a certain schema and then must reenact the norms associated with their particular racial designations through bodily acts such as manners of speech, modes of dress and bodily gestures (Ehlers, 2012). Ehlers argue that by addressing the ways race is performative and disciplinary does not only point out that closed systems can be altered but also as Foucault has suggested, “contribute to changing certain things in people’s way of perceiving and doing things” (Foucault, 1981;12, Ehlers, 2012;14). In Performing Blackness on English Stages 1500-1800 Vaughan (2005) states that the theatrical performance cannot be completely equated with the everyday performativity, which Butler and Ehlers argues form our conceptions of gender and race however, Vaughan acknowledge that the two kinds of performances shares the similarities of “repeated acts within a highly ridged regulatory frame” (Butler; Vaughan, 2005;3). Vaughan have focused on racial performances. She examines historical convention of theatrical performances of blackness and how performances (in a theatrical/stage context) contribute to racial identifications. Vaughan explains that “impersonation is, of course, never static; it changes from performance to performance as audience dynamics, playing spaces, and cultural attitudes change. And by repetition impersonation builds on what has gone before, its reiterations and variations adding layers of meaning to the performance’s signification with each new reenactment”

(Vaughan, 2005; 170). These repetitions over time creates what Butler called “a natural sort of being”. When repeated from play to play or enactment to enactment, over time, these performed acts or doings becomes truths and accepted as natural facts.

Mark B.N. Hansen present a useful notion in his book Bodies in Code digital performativity and performance of race and ethnicity in cyberspace. Hansen refers to Thomas Foster who argues that online identification in general is similar to racial performance, “As blackface shows, racial norms have historically been constructed through the kind of antifoundational performative practices that have come to be associated with postmodern modes of cross-identification and gender-bending. By ““antifoundational,” I mean that in blackface performances it was not necessary to ground racial identity in a black body. Nor was it necessary to occupy a black body in order to be perceived by others as producing a culturally intelligible performance of “blackness” (Foster,1999, Hansen, 2006;145).

By citing Foster, Hansen demonstrates that raced identity has always been constructed as a disembodied mimicry and that race is a performance of conventions detached a physical body, which therefore it is closely related to online performances because, in both cases, identity is exclusively bound to the imitation of culturally sanctioned signifiers (Hansen, 2006;146). These statements again point back to Ehlers and Butler’s theories of subjectivity is that the mechanism through which thus disciplinary formation is installed and sustained is racial performativity and that all racial subjects can be said to execute a kind of performative racial passing.

6.2 Representation

As this study seek to address how memes can reinforce stereotypes, the theoretical lens of representation is relevant to look through.

Representation theory in relation to media is concerned with how the ‘reality’, meaning the society and the people within it, are represented and presented in different types of media texts, to its audience. Representation theory involves key markers of identity such as class, gender, ethnicity, race and how these aspects of identity are represented, or rather constructed, within different media texts, but also it is concerned about how these texts are received, interpreted and affect the lives of those people represented. A particular focus within media representation theory has been on minority groups and ethnic identities, and if and how they get represented in the media sphere. The discussion is not only constricted to a general underrepresentation but also, a misrepresentation. A central term or concept of representation theory relevant for this discussion is stereotypes and stereotypical representations which construct a narrow and generalized version of the lives of the ethnic identities (Hodkinson, 2017).

“Typical stereotypes that developed In America under the years of slavery, colonialism and blackface minstrelsy, was the childlike ‘Uncle Tom’, the

lazy ignorant ‘Coon’ and the larger than life ‘Mammy’, the ‘happy go lucky’ entertainer, and the dangerous animalistic native - all of whom presented those of African origin as irrational and inferior” (Hodkinson, 2017;224). Stuart Hall have theorized representation in relation to culture, media and identity. Hall states that “representations mobilize powerful feelings and emotions, of both negative and positive kind. They sometimes call our very identity into question. Serious consequences can flow from these representations. They define what is “normal”, who belongs – and therefore who is excluded. They are deeply inscribed in relations of power” (Hall, 1998;10). According to Hall, who takes a constructivist view, representation is linked to language, he states that language operates as a representational system where language is broadly defined as any system which deploys signs, in whatever form it may come, word, sound, text, sign, gesture, image - all is loaded with meaning (Hall, 1998). A constructivist approach to representation states that meaning is constructed in and through language. Hall further argues that no meaning is fixed, interpretations of language and meaning differs from person to person and from cultural and historical context. Hall sees the system of representation as two related functions ‘meaning’ and ‘language’. We create meaning at a mental level however we cannot ‘represent’ this meaning without the use of language as a mean of communication. Further he adds that language can only translate into meaning if it “possess codes”. These codes do not exist in nature but are the results of social conventions that creates shared “maps of meanings” – these meanings we unconsciously learn and adopt when we are a part of a culture (Hall, 2010;29). “The constructionist approach to language thus introduces the symbolic domain of life, where words and things functions as signs, into the very heart of social life itself” (Ibid).

In The Spectacle of The Other Hall (1998) introduces the theme of ‘representing difference’ where he centers ethnic and racial difference, and addresses the representational practice of ‘stereotyping’. Hall states that these representational practices are inscribed by power relations between those represented and those doing the representing (Hall,1998), he continues saying that “stereotyping (…) is part of the maintenance of social and symbolic order. It sets up a symbolic frontier between the ‘normal’ and the ‘deviant’, the ‘normal’ and the ‘pathological’, the ‘acceptable’ and the ‘unacceptable’, what belongs and what does not or is ‘Other’, between ‘insiders and ‘outsiders’, Us and Them” (1998;258).

Other relevant notions on stereotypes has been presented by Walter Lippmann who first coined the term stereotype in 1922. He defines stereotypes as (a) an ordering process, (b) a ‘short cut’, (c) referring to ‘the world’, and (d) expressing ‘our’ values and beliefs (Dyer,1993, Dyer, 1999; 1). Lippmann argues that stereotypes are ‘simple’ rather

than ‘complex’, this notion however, has been challenged since, but the initially notions put forth by Lippmann is still useful to understand what characterizes stereotypes. Andy Medhurst (1989, 2007) elaborates on stereotypes functions as short cuts, explaining how stereotypes often is used in popular culture and media as a form of shorthand which allows a text to communicate quickly to the audience, by using simple and easily grasped forms of representation. Therefore, some mediums more frequently make use of stereotypes as they work with a limited time frame. As an example, Medhurst mention sitcoms tendency to picture social characters in a genializing and stereotypical way in order to secure entertainment of the audience (Medhurst, 1989, 2007).

Medhurst’s description of how stereotypes are used in popular media as a shorthand to entertainment, can serve my analysis in understanding how and why memes uses stereotypes.

Tessa Perkins (1979) challenge Lippmann statement of stereotypes as a ‘simple’ form of representation, as she argues that they contain complex connotations and therefore states that the notion of ‘simplicity’ is deceptive and that stereotypes are simultaneously simple and complex (Perkins, 1979). Perkins clarify; “to refer ‘correctly’ to someone as a ‘dumb blonde’, and to understand what is meant by that, implies a great deal more than hair color and intelligence. It refers immediately to her sex, which refers to her status in society, her relationship to men, her inability to behave or think rationally, and so on. In short, it implies knowledge of a complex social structure.” (Perkins,1979: 76). Perkins here seeks to highlight the complexity of social beliefs and connotations that are connected to stereotypes, she continues “With stereotypes we must look beneath the evaluation to see the complex social relationships that are being referred to, this not simply meaning that stereotypes are simple reflections of social values, instead stereotypes are selections and arrangements of particular values and their relevance to specific roles” (Perkins,1979:79).

According to Perkins, the strengths of a stereotype result from a combination of three factors, its ‘simplicity’; its immediate recognizability (which makes its communicative role very important), and its implicit reference to an assumed consensus about some attributes or complex social relationships. Stereotypes is according to Perkins prototypes of “shared cultural meanings” (Perkins, 1979;78).

Perkins explains how racist revival is linked to people’s knowledge of stereotypes. Cartoonist and comedians often appeal to the most stark and exaggerated version of a stereotype, this statement aligns with Medhurst (1989, 2007) that stated that the use of stereotypes allowed for audience immediately identification and clear way to laughter. In relation to this, Perkins categories stereotypes and suggest reasons and consequence of them. One group of stereotypes is about Major Structural Groups, this group contains stereotypes about color (black/white), gender (male/female), class

(upper/middle/working) – Perkins explains how everybody is a member of each group in this category and therefore, when using a stereotype from this category, you can communicate jokes to a mass audience (For further elaboration of stereotype groups see Tessa Perkins, 1979). Perkins explain how mental characteristics in stereotypes are dominant, according to Perkins this is because they are ideologically the most significant. The most common feature of stereotypes from the major structural groups relates to their mental abilities, the oppressed group is often characterized as less intelligent. Central to Perkins understanding of stereotypes is that they are ideological concepts and have particular ideological significance, in this way Perkins relates to Hall, as she argues that stereotypes function as symbols with an ideological meaning. Richard Dyer (1999) suggest that,” stereotypes express particular definitions of reality, with concomitant evaluations, which in turn relate to the disposition of power within society” (Dyer, 1999:4). Dyer refers to Berger and Luckmann that states “he who has the bigger stick has the better chance of imposing his definitions of reality” (1967;127, Dyer, 1999;2). With these statements Dyer aligns with Halls notion of representations being about social power. Further to understand how stereotypes are coined and who have the power to enforce stereotypes, Dyer uses Orrin E. Klapp’s distinction between ‘stereotypes’ as being those who are outside society and ‘social types’ as being those who belong to society. Dyer rework Klapp’s notion in relation to social groups – who ‘does’ or ‘does not’ belong to a given society, as a whole is then a function of the relative power of groups in that society to define themselves as central and the rest as ‘other’ peripheral or outcast (Dyer, 1999;4). Evidently Dyer here suggest that there are ideological implications with stereotyping, and that stereotyping is about power relations in society (Dyer, 1999). Dyer statements points out that stereotypes work to legitimize inequality.

The notion of stereotypical representations in order to install or maintain power relations is supported by Martin Gilens (1996). Gilens discusses racial representation in news media images, in his essay “How the poor became black” Gilens argues that being poor over time have become synonymic with being black. According to Gilens, for the most part over the past three decades, there have been an overrepresentation of blacks among media portrayals of poor (1996;111). Gilens understanding of “the poor being black” resonates with what Eric Lott explained about black becoming a metonym for working-class or “poor”.

7. Methodology and Data:

This chapter will present the research methodology, the empirical data and methods, (critical discourse and visual analysis) as well as ethical considerations.

This study seeks to explore how the phenomenon Digital Blackface operates online by investigating the Sweet Brown memes, and further what social structures and beliefs

that are reflected in this form of online racial performances. By studying memes and the modes of communication of which they consist, and in the context their occur, it is possible to interpret and gain an understanding of how Digital Blackface operates online, what representations of black people they present and what racial discourses there can be found in internet memes.

7.1 Empirical Data

This study focuses on the case of Sweet Brown and memes of her. The method used for sampling the data was judgement sampling, which means that the researcher selects the data based on its relevance for the study and the research questions (Collins, 2011). Having employed this method, the empirical data therefore consist of various memes of ‘Sweet Brown’ selected based on their popularity on the Internet. The aim of this study was to understand the concept of Digital Blackface and how internet memes functions as a form of online racial performance. To understand this, an analysis of these memes and observations of how they have been used online, was conducted. Below I will present the case of Sweet Brown and how the case/data came to my attention. The data came to my attention from looking into the concept of Digital Blackface. My intention was to examine memes and the representation of black people in Internet memes and how they are used by white people online. Due to several problematics of accessing private social media accounts, I decided that it would not be feasible, so I changed my focus.

In my early state of research on Digital Blackface and racial performance online, I came across the meme “Sweet Brown” which frequently appeared in different versions, some more offensive than others. Further I came across several recent articles, which discussed the use of visual online content of black people and the phenomenon “Digital Blackface”, and also referring to the case of Sweet Brown. Other cases came to my attention in relation to racial performances, here the case of the Swedish influencer Emma Hallberg accused for Blackfishing and Ian Mckay, the man behind the fake Australian Facebook page of BlackLivesMatter. These two other cases implicated some of the same issues I was interested in and was therefore also considered cases for this study, however, to focus the research, I decided to concentrate on Internet memes and the phenomenon Digital Blackface and related it to the historical context of blackface minstrelsy. From here I decided to keep my attention on the case of Sweet Brown and look more specifically into memes of her and their use and popularity online.

My data collection process started with a simple google search on “Sweet Brown”, to find articles and other relevant material about her. My approach to the data collection was not systematic, instead it followed a more dynamic process one source leading to the next. To find out how her image has been turned into memes, I conducted an image google search, as well as consulted pages such as www.knowyourmeme.com, and www.memecenter.com. Further YouTube have been a source for collecting data, both